Editor’s note: This text-based course is a transcript of the course, A Conceptual Model for Vision Rehabilitation, presented by Pamela Roberts, PhD, MSHA, OTR/L, SCFES, FAOTA, CPHQ, FNAP.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to describe the theoretical foundations underlying vision assessment.

- After this course, participants will be able to identify a vision conceptual model for assessment of patients.

- After this course, participants will be able to recognize the practical application of key elements of vision assessments and the relationship to the conceptual model.

Pam: As mentioned, I will be talking about a conceptual model for vision. This work was done with my collaborators through the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine Vision Task Force.

Outline

I will be talking about vision deficits when looking at acquired brain injury, which will include stroke and brain injury; the importance of looking at a systematic assessment for visual impairments, a conceptual model for vision rehabilitation; and then how to utilize the conceptual model in occupational therapy practice. As occupational therapists, we look at "pursuits". This is a play on words on how we went about looking at a conceptual model.

Vision Deficits in Acquired Brain Injury

First, I want to talk at a high level about some of the literature that is out there. The World Health Organization estimates that approximately 285 million people worldwide have some type of visual impairment. That is quite large. The morbidity is significantly increased when it is related to sensory and functional deficits and is not comprehensively managed.

Statistics on Visual Impairments

The prevalence of visual deficits ranges between 30% and 80% for those with acquired brain injury, which is quite a range and highly variable. Many times, the issues get lost because there may be other pressing priorities, people are not skilled in it, or they do not think about it. Although many more people today are starting to think about it. Vision is one of the primary senses that we use in everyday life. Individuals with visual impairments have a two times greater risk for falls; greater than four times the risk for hip fracture; three times the risk for clinical depression; increased isolation, especially socially; difficulty with medication management, possibly because they cannot read the labels, the fine print, the precautions, or other issues related to medications; and are placed in a nursing home earlier than people without visual impairments. They may have increased use of community services, and there may be increased mortality.

Vocabulary

When studying or discussing visual deficits following acquired brain injury, it is important that everyone is utilizing the same vocabulary of what is associated with visual deficits. This includes problems with visual acuity, peripheral fields, color vision, and double vision. For example, many times a person will say that they have not been to the eye doctor in awhile assuming their issue is a visual acuity problem. However, there may be other things going on. It is really important that we understand the different terminology of the different types of deficits, as well as look at the conceptualization of these visual deficits. Other visual deficits could be oculomotor, accommodative deficits, convergence, divergence, strabismus, cranial nerve palsies, and visual field losses.

There is a table in this article where you can see the prevalence of these different visual impairments. This will help you to see how visual deficits are related to ADLs and IADLS. Many individuals in neuro-rehabilitation are impacted by visuoperceptual or oculomotor deficits. Regardless of the type of deficit, vision problems in stroke, as well as brain injury, can really limit participation in activities of daily living (ADLs) as well as instrumental activities of daily living (IADLS), especially if there were no problems before the stroke or brain injury.

Importance of Systematic Assessment for Visual Impairments

Vision is a very critical component, throughout the lifespan, regardless of what you are doing. Vision is a very critical, complex network that provides sensory input to help us interact in our environment. Depending on what you are doing, there are different types of interaction. For example, if you are a baseball player, you need to have visual acuity to see where the location of the ball, versus if you are doing something more sedentary, such as reading or painting.

Many organizations, as well as individuals, have created guidelines; they have written articles, had dialogued, and have made recommendations. But many times, in the literature, there have been select populations. It may not generalize to the larger population. It may be only to specific professions, or only address one aspect of vision care. It could address acuity, eye-hand coordination, or perception, but it is not a systematic way of looking at all the different issues. The research may not even be in the rehabilitation literature but may be more in the optometry or the ophthalmology literature. Individual professionals have contributed to the creation of different frameworks or concepts in vision rehabilitation. But if you look at all these different professional organizations or individuals that have done the work, there has really been no systematic method for assessment, especially looking at it from an interprofessional approach. There really needs to be some type of universally accepted model, and a way for the rehabilitation assessment and treatment interventions for visual impairments to start earlier in the course of recovery.

A Conceptual Model for Vision Rehabilitation

Hopefully, I have laid the background work for you. Now I am going to start breaking apart this model that a group of interprofessionals put together. The American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine, better known as ACRM, through the Stroke Interdisciplinary Special Interest Group Vision Task Force, conceptualized this work. They identified a need for this conceptual model to provide an interprofessional vision rehabilitation framework.

The proposed framework was deemed vital for health care professionals to systematically assess, communicate, and collaborate on patient care and clinical research, as it relates to the visual system and its relationship to impairments, activity limitations and participation restrictions, in the broader function and quality of life domains

As I said earlier, part of it was from a lack of communication and understanding between rehabilitation clinicians. However, it really impacts the development of a comprehensive treatment plan. In today's society, with decreasing lengths of stay in institutions, there is a need to establish working and collaborative frameworks to address and facilitate early intervention, and incorporate vision. If there are some issues, the proposed framework is supposed to be vital for health care professionals to really look at things in a systematic way to assess, communicate, and collaborate not only with the patient, but also with the family, clinical researchers, and the clinical team. The communication would relate to the different types of visual systems, their relationships to impairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions. In the broader context, it would look at how someone functions regardless of environment and impairment, and how that impacts their quality of life.

One of the things that we use for the foundation for this conceptual model was the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health framework, or the ICF. In the ICF, you have the health condition or the disease. The impairments are the body functions and structures. An example would be acuity. Next would be the activity or the activity limitations that may be caused by something that is from impairment in the body's functions and structures. Finally, it looks at how the activity or activity limitations impacts participation or restrictions in being able to participate in one's environment. Within this, what are those contextual factors that also play a part when looking at activity and participation? There could also be environmental factors or personal factors that contribute to the contextual factors, which in turn, contribute to impairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions.

The reason we used the ICF as a standard language is that it is well known in many domains. Additionally, when we started to look at some of the literature by Dr. August Colenbrander, who is an ophthalmologist from Northern California, he wrote about visual function and functional vision, and that these two key terms help to differentiate the two core domains within our conceptual model. I am going to define them in a minute, but it is really important that you understand the difference between visual function and functional vision.

Vision Function

- How the eye functions as an organ

- Lower-order cerebral mechanism (eyes and related visual structures)

- Deficits described as visual impairment

Functional Vision

- How the person functions in their environment

- Higher-order cerebral mechanism (visual information processing, etc.)

- Deficits described as visual dysfunction

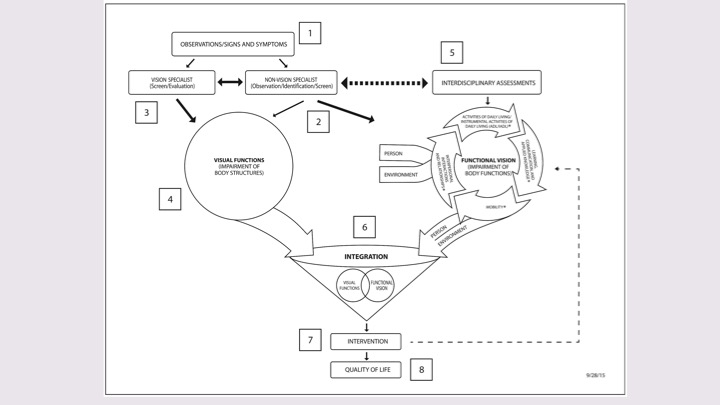

I am going to break this conceptual model down and look at each one of these aspects. This is the overall conceptual model in Figure 1, and there is an article with a reference at the end if you want a bigger picture of this.

Figure 1. Conceptual Model for Vision Rehabilitation. (Download as a PDF to enlarge on a computer).

There is a PDF version to download. We will talk about this model as we go through the presentation and the numbers correspond to different slides as I talk through each aspect of this model.

#1: Observations, Signs, and Symptoms

Number 1 in the model is observations, signs, and symptoms. Observations/signs and symptoms may be observed or communicated by the patient, family, caregiver, friends, or any member of the interprofessional team. Here are some of the areas to address:

- Blurred vision

- Double vision

- Visual inattention

- Head tilt/turn

- Headaches

- Droopy/Unable to close the eyelid

- Eye turn - right/left

- Squinting/closing one eye

- Dizziness/Vertigo

- Nystagmus

- Photophobia

- Leaning/drifting to one side

- Spatial disorientation

- Loses place while reading or tracking

- Images/words move or appear unstable

- Bumps into/unaware of objects on one side

- Difficulty judging distance while walking/reaching for objects

Impaired vision could interfere with the daily activities, how someone moves in space, their spatial orientation, identification, or their eye-hand/eye-body coordination. When they are eating, do you observe anything that might be impacted by vision? When they are reaching for an object, do they underreach or overreach? Can they read or when they are reading, are there words that are popping out? Are they missing letters? For meal preparation, how is their safety? Are there issues with how they are scanning to find things in cabinets within the kitchen? When they are walking, are they bumping into things? Are they having problems climbing stairs? Are there issues with depth perception? Are there issues with driving? Hopefully, they are not driving at the time if they are having visual issues, as there is a lot of vision that goes into driving. Are any other type of daily activities impacted? Do you notice any signs and symptoms that may relate to vision?

#2: Non-Vision Specialist

Going back to the model, number 2 is the non-vision specialist. There was a lot of controversy with the wording of this article when we were trying to get it published. We had to change it multiple times to appease the author. I am not sure that this is the best terminology, but for now, this is what it is. There are people that are experts in vision, but that is not the only thing they do. This is about observation, identification, and screening of vision issues. This could be anybody on the interprofessional team. It could be an occupational therapist that does not have a specialty in vision. How do you look at vision in a much broader context? How do you identify issues that have to do with visual dysfunction? Do you look at a hands-on functional performance? How do you observe higher-order cerebral mechanisms of vision, and focus on the totality of the impairments? How do you remediate these deficits with the broad range to compensate, substitute, or remediate? The primary focus on rehabilitation is always function and quality of life. In the role of the non-vision specialist in their observations, identifications, and screens, are they able to communicate an integrated approach as a front-line specialist? Do they have a functional vision perspective, and how they would collaborate and integrate a vision specialist into the overall treatment team?

#3: Vision Specialist

The third aspect of the conceptual model is looking at vision specialists. This is where you are really getting into much more of a screen and evaluation. This could be an ophthalmologist, an optometrist, or any other professional who really specializes in vision rehabilitation. If you are an occupational therapist, and you specialize in vision rehabilitation, you could be the vision specialist. But maybe you are just a general OT and that is not your specialty, you may be more in the role of helping to identify and then getting them to the expert. This is really looking at your visual system and how it functions. Ophthalmologists typically look at the medical, surgical, and optical care. Optometrists usually provide eye and related visual structures as well as lower order and focus on higher-order visual systems, including visual information processing.

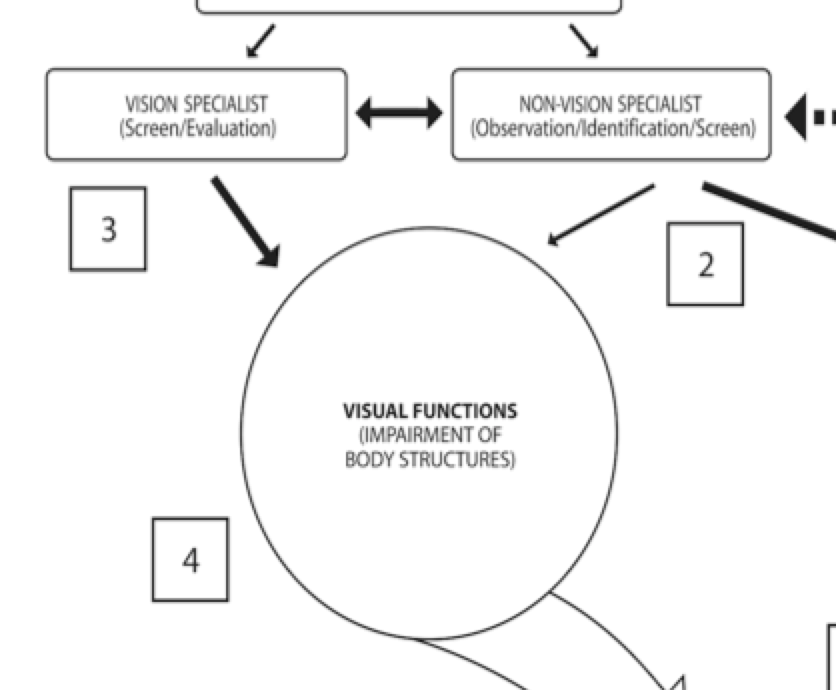

What is the interaction between the specialists and the non-specialists? If you go back to the model (Figure 2), there is an interaction that is really critical between these two different professionals. What is that interaction between the vision specialist and the non-vision specialist that enables the sensitivity and the specificity of visual screening? For example, the vision specialist may diagnose a problem with the retina or the optic nerve, which really looks at the circle, which is on the left part of the diagram (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Example of vision and non-vision specialist interaction in the model.

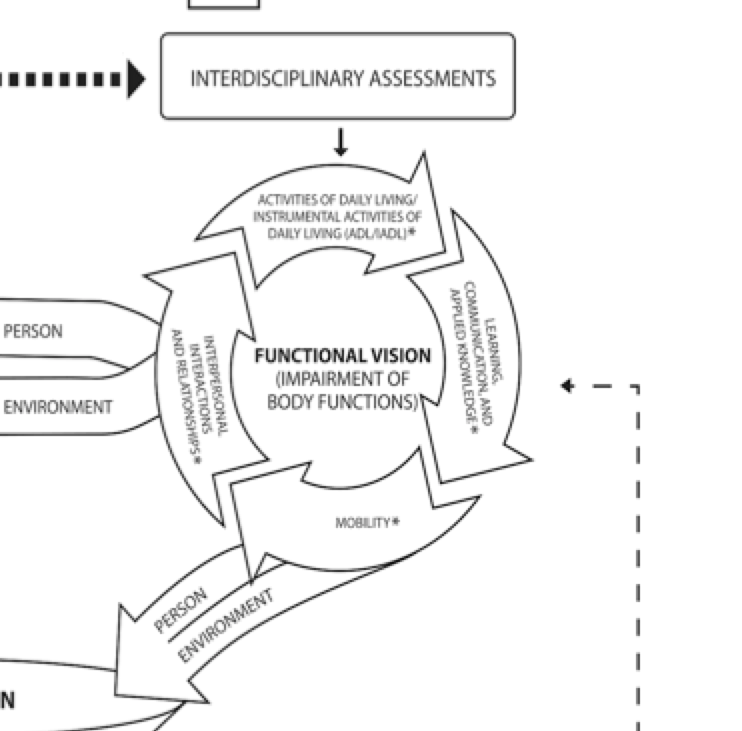

These are the vision functions in this circle here. We are looking at the vision specialist who might diagnose a problem within the retina or the optic nerve. It is important here to note that this is how the eyes function but does not inform the clinician how the person functions. It is important to focus on the eyes, and not how that person functions with the vision issues. Functional vision, which is on the other side of the model (see Figure 3), is our functional vision.

Figure 3. Example of functional vision area on the model.

To repeat, in Figure 2 we are looking at the eye and how the eye functions, while Figure 3 shows the functional vision and this is where we look at how the person functions with the vision deficit. This is the critical difference between visual function and functional vision. The interaction between the non-vision specialist and the vision specialist is defining the roles to further clarify and screen for dysfunction. In the conceptual model, this helps to standardize the nomenclature and really to systematically organize and integrate the information when looking at both visual function and functional vision. On that left-hand side of the model, you are looking at visual function, which is the assessment of the organ level impairment; whereas, on the right-hand side, this is the person-level dysfunction or that functional vision with incorporating the person and the visual issue.

#4: Visual Functions

If we look at the visual functions, we are looking at the impairment of body structures.

- Refractive errors

- Cataracts

- Glaucoma

- Macular degeneration

- Diabetic retinopathy

For example, this could be somebody that has issues with visual acuity. This would be a refractive error. Some of the most common types of optical deficits might be myopia, which is nearsightedness; hyperopia, farsightedness; astigmatism, which is mixed-sightedness as a result of a curvature of the cornea; or presbyopia, which is farsighted that is associated with aging due to reduced elasticity of the lens. On the left-hand side of the diagram, this is looking at the visual functions. What are those impairment of body structures, and how does that relate to the vision issue? For example, if someone has cataracts, this is someone that has an impairment of the visual functions. This is a clouding of the lens or they may see the world as blurry. In this model, that would be part of the visual function issue. Glaucoma is another example. Somebody that has glaucoma does not have the full visual field. They have to have their eye pressure checked, and they often have impairments in their peripheral fields. Macular generation is age-related and gradually destroys the retinal function within the central macular area. Finally, the last example is diabetic retinopathy. This is the leaking of retinal blood vessels, which is the second leading cause of blindness, blurred vision, and distorted vision. To view pictures of how vision would be distorted with these disorders, visit the National Eye Institute (NEI) website. Clients with these disorders need to be referred to a vision specialist. Again, these all fall on the left side of this diagram for visual function. Now on the right side of the diagram, I am going to be looking at functional vision.

#5: Interdisciplinary Assessments

Functional vision is the impairment of body functions. At the top of the circle in Figure 3, there are activities of daily living. Next, we have learning and communication, mobility, and so on. II will just be describing all of these individually. When we are thinking about functional vision, we think about activities of daily living. This could be somebody shaving or applying his or her makeup. These types of activities require vision and perception. We could also look at instrumental activities of daily living. It could be cooking a meal or using a computer. It could be learning, communication and applied knowledge like reading, communicating and writing. Being able to walk, cross the street safely and other mobility activities are also areas to assess. Within this functional vision area of the model, we also have the influences of the person and the environment. These are coming over from the other circle looking at vision function. The person and environment provide different input.

Within the interdisciplinary assessments, we have to look at the person. What type of roles do they have? What are their experiences? What are their beliefs? Do their roles vary? What is the importance of these different roles? Looking at the environment, is it an indoor space? Is it stimulating? Is it in the middle of traffic? In what types of environments, does the person need to be able to use vision? Do they have different contexts: cultural, socioeconomic, physical, and social? The person and environment influence the person's ability to use functional vision.

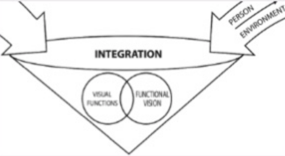

#6: Integration

This looks at the integration of the visual functions and functional vision on the model.

Figure 4. Example of the integration area of the conceptual model.

How are they integrated? It is really important to look at the combination of specialists and how the care is highlighted in the overlapping circles. Here we have visual function, as I have just described, and then we have functional vision, but there is an overlap. Usually, when you have the vision impairments, they are also impacting somebody's ability to function. How are these areas of visual function and functional vision overlapped and integrated to help focus on patient-centered care? What is being done? What do we need to do in our treatment interventions to impact that integration?

First, we have to identify it and make the assessment. What are the visual function issues? I did not cover all visual function issues, but I gave you some of the common examples. An example might be a person with left homonymous hemianopsia. He or she will interact and communicate with the world differently, and accommodations may be needed. Somebody with a visual field cut is going to interact very differently with the world, than someone with full vision. How would this person navigate a crowded environment, read, or participate in daily activities? How do they read a menu? Are they only seeing half the menu? Maybe they have a left-field cut and are not able to see the left side of the menu. How do we integrate vision rehabilitation, and what can we do to be able to address the integration of the impairment with the function?

The non-vision specialist and the vision specialist can provide different therapeutic interventions that should be individualized to meet the needs of both the visual function and the functional vision and to help remediate the problem of the impairment and the functional vision dysfunction. It is important to target health, well-being, and quality of life. Within occupational therapy for assessing functional vision, we need to know how they participating, and provide any adaptations so that they are able to, regardless of their visual function impairment. We may also work with other professionals, such as an optometrist. One integration example would be looking at eating. The vision specialist may prescribe prisms to help them be able to see the entire bowl versus just part of it. The non-vision specialist could incorporate these prisms during all mealtime activities. The vision specialist prescribes them, sets the diopters, and determines how long they are going to wear them; whereas you could have your non-vision specialist follow-through and carry over that therapeutic intervention.

Another example would be the vision specialist who works with the non-vision specialist in daily activities. This could be to improve someone's comfort, help eliminate double vision, provide the ability to process information, and possibly improve safety during daily activities. A person could be prescribed a translucent patch so that it still lets light through, but helps with the double vision.

Other aspects of integration are how do they relate to functional abilities? What is the dialogue? By using the same terminology, this can this lead to better and improved dialogue. I think by using the same terminology, this at least puts you on the same playing field, but whether it really impact better outcomes needs to be further tested. This framework was really to be an efficient way to look at assessment and interventions and to customize and individualize different approaches. In that sense, the goal would be to improve outcomes. As I said, this still needs to be fully tested.

#7: Interventions

As an overview, we are looking at those overlapping circles of integration between the two different aspects. If we go back to our model, we have on the left-hand side visual function, and then on the right-hand side, functional vision. The integration is the play between the two. We have our vision specialist and our non-vision specialist collaborating and working together to address the visual functions and then the functional vision. Finally, we develop our interventions to work towards quality of life. Within interventions, the non-vision and vision specialists need to provide interventions and look at outcomes. Most importantly, can we do anything early to address vision impairments before they go back out in a community? How can we start early and be able to identify vision impairments and start working on vision function and functional vision in the very early stages of a stroke or acquired brain injury? During these vision assessments, how do we relate it to the functional abilities? If we use adaptations, activities, strategies, or exercises, how can we improve someone's functional ability?

Visual field loss.

Functional Observations During Treatment Sessions

- Complains of seeing only half of the image

- Turns or tilts head to one side

- Absent of poor eye contact

- Limited scanning

Intervention

- Start with familiar/simple activities: self-care (eating, grooming)

- Mealtime/grooming activities:

- Limit amount of items on tray/table

- Head turn

- Visual imagery: teach placement of food in "clock" pattern

- Place items in the patient's midline and gradually work on increasing their peripheral vision awareness

For visual field loss, how do we develop an awareness of peripheral vision during functional activities? Do we need to incorporate compensatory issues for safety, increased independence, or increased performance of daily habits? How do we look at those strategies, integrate, and incorporate them into their daily habits, roles, and routines? An example of visual field loss from the functional aspect is someone is complaining of seeing only half an image. They may turn or they tilt their head. Do they have absent or poor eye contact? Are they scanning? Are they leaving out a certain side? Maybe they are leaving out certain areas like the left side, the left upper quadrant, or left lower quadrant.

You could start with familiar, simple activities such as grooming or eating at a tabletop. You want to limit how much is on the bedside or kitchen table to make sure that somebody is turning their head during the ADL activity. Look at visual imagery. Teach the placement of food in a clock pattern. You can also place items in the midline, and gradually working on increasing their peripheral vision awareness.

You want to incorporate peripheral vision awareness strategies. For example, how do they do with crossing the street? How do you help someone look at safety hazards? How do you have somebody turn their head during mobility activities so that they are not bumping into things, tripping, or falling? How can you incorporate compensatory techniques during walking to avoid safety hazards? If they are bumping into things and are having difficulty judging distances, how can we help them? How are their navigational skills? Are they missing critical information because they are only looking in one direction, which does become a safety hazard?

From an intervention standpoint, you need to address patients in the midline or in their visual field so you do not startle them? Start small, and then gradually move into their affected visual field, so that you start teaching them how to compensate. Position yourself on their affected side during ambulation and teach the families that as a strategy. Make sure there is nothing hot on their affected side. You may also look at writing and reading tasks. You can create borders or markers at the beginning and end to cue them where their start and stop points are. For example, a green marker could be "start," and red would be "stop." You could also do this with computers. For dynamic balance activities, you can use large, bright-colored stationary objects to help orient somebody in their visual field. You can give them markers to help them to scan on both sides so they are not running into hazards. You can work on increased vision awareness to increase their engagement in daily activities. For example, if somebody loves to garden, you can have some demarcations, like the grass and the dirt. This is an example of a visual anchor in a natural environment. Hopefully, that gave you some examples of some things using one example of visual loss.

#8: Quality of Life

When we are putting this all together, it is about the assessment and the intervention for vision function and functional vision. It is critical to have the right team members, whether they are non-vision specialists or vision specialists. Clinicians need to have the opportunity to ensure that effective compensatory, substitutive, and restorative interventions are effectively deployed early on in treatment.

Uses of Vision Conceptual Model in Occupational Therapy

How do we use this conceptual model in occupational therapy? It does not matter where you are treating or where you are in the continuum, whether in acute care, inpatient rehabilitation, skilled nursing, long-term care, community, home health, outpatient rehabilitation, or other types of community settings like schools. Regardless of where you are or what environment you are in, if someone has vision impairments and functional vision deficits, there are things and ways we can help in contrived, institutional or naturalistic environments. I think this is especially important within the naturalistic environment because there is so much that requires vision. Where does your eye go? How do you help somebody that has a visual loss? What are the anchors they can use?

In institutional care, who is doing the screens or assessments? Is it being done? Importantly, you may need to teach the entire interprofessional team to be able to observe signs and symptoms. Do you have a formalized vision screen? Who does it? Is there a formalized assessment? Are there interventions in place? Are you teaching the patient, the family, and the caregiver to integrate and carry over techniques? Are you making it simple enough that they can understand? How do you integrate the information into the interprofessional team? For example, if someone has prisms on, and you are the vision specialist, how do you ensure carry over with the goal of eventually getting rid of the prisms? Typically you start with temporary prisms and then determine later if they need to be permanently put into the glasses. In your practice area, are there vision specialists? Are they integrated into the professional team? Do you have them on your team, or do you have to wait until they are an outpatient? Can you integrate them into the hospital? Are ophthalmologists and optometrists supportive of functional vision? And if they are, are they consulted with when they are in the acute care hospital or at whatever setting you are in? Are they available? Do you need to develop vision specialists? Is occupational therapy the best suited for this? Are there other practitioners? Who is involved? This may vary from institution to institution, depending upon different protocols and programs in place. In other settings, you can follow the sequence from institutional care, but you can develop this anywhere within the continuum. I think that developing some of these markers within a naturalistic environment will get you better outcomes. You also need to make sure that your patient is fully invested. How do you support the carryover of activities, home programs, or follow-up appointments to address vision? If you are in a school system, are you using the teachers in the school? Who else is involved? And within your network, do you have community vision resources that you can help refer patients or clients to? How are you collaborating with that interdisciplinary team? How are you making sure that everybody knows what to look for? What are those signs and symptoms of vision deficits? How is that involved in your practice? What team members are available to participate? Does each team member contribute? Do they need competency in this area? Are there interventions that can be incorporated into more than one discipline? How do you make referrals and resources if they are not available? How do you go about getting them?

Conclusion

Today we have discussed the model, described the roles of vision specialists as well as non-vision specialists and how both are incorporated into the care team, and how the integration of functional vision and visual functions is extremely important. It is important to understand the impairments and how they relate to the function. We also need to understand the person and the environment/contextual factors. The Conceptual Model for Vision Rehabilitation could impact the quality of life and overall safety of our clients.

It is important to remember that the World Health Organization estimates that 285 million people are affected by vision impairments. That is a very large number, and it is important that we address vision in a very systematic manner. Individuals who have visual impairments have two times the risk of falling, three times the risk of depression, have increased isolation, and difficulty with medication management. It can really impact their daily activities. Another important point is that the current vision guidelines have dealt with select populations, specific professions, or usually only one aspect of vision. It was not dedicated to the whole interprofessional team. This is why the whole conceptual piece of the interprofessional model was developed. Another take-home point was to look at the foundations for the conceptual model (visual function and functional vision), and hopefully, you now understand the difference. Vision function is much more than the impairment, and then functional vision is what we do with it. Another review point is looking at the signs and symptoms of the non-vision specialist. Anybody on the interprofessional team may have an impact and be able to identify when vision is impacting someone's ability to move in space. Another important point to remember is that myopia, hyperopia, astigmatism, and presbyopia are examples of visual function deficits, and are on the left side of the model. Activities of daily living, communication, applied knowledge, mobility, interprofessional interactions, and relationships are on the right side of the model as part of functional vision. I hope I made the case today of the difference between visual function and functional vision, and how they have to be integrated. This conceptual model is really applicable to people in institutional care, whether it is the acute care hospital, skilled nursing, inpatient rehabilitation, long-term care, communities, school systems, or behavioral health. Really, it could be put together based on who your team is and in any type of setting. And finally, vision specialists and non-vision specialists are part of the interprofessional care team, and they provide the foundation for completing that optimal comprehensive assessment that will lead to interventions, as well as, the integration of the two concentric circles of functional vision and vision function.

Reference

This was the article that was published and will go into more detail than I covered today. I would like to acknowledge Dr. John Rizzo from New York NYU, Dr. Jeffrey Wertheimer from Cedars-Sinai, Kimberley Hreha from Kessler Institute for Rehabilitation, Jennifer Kaldenberg from the College of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences at Boston University, Dawn Hironaka from Cedars-Sinai and Richard Riggs from Cedars-Sinai. They were all instrumental in putting together the model and working as part of the interprofessional team. I would also like to acknowledge Dr. August Colenbrander, who was from the Smith-Kettlewell Eye Research Institute, as well as some other professionals from within his group. Additionally, Dr. Mary Warren was very instrumental in providing her expertise, as she has done quite a bit of vision. She gave invaluable input in the very initial phases of our model development. Kelly Hironaka assisted in doing the graphics for us.

Questions and Answers

If a vision specialist is not on board during a patient's acute care inpatient rehab stay, how can that intervention be obtained so that it can be incorporated into rehab, such as the use of prism glasses?

What we did in my own facility is we worked with our medical staff to get our optometrist or neuro-optometrist as part of the medical staff. It took a long time and collaboration with our ophthalmologist to be able to even allow them to become medical staff and consult with us. I think that may be individual within your own system. It took us probably two years to get it up and running and find the right people.

Citation

Roberts, P. (2017). A conceptual model for vision rehabilitation. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 3823. Retrieved from http://OccupationalTherapy.com