Julia: Hello, everybody. Last week, we worked through some of the outcomes and evaluations used with those with Parkinson's. Today, we are going to look at treatment. The main learning outcome is to identify and list occupation-based treatment strategies to address participation challenges that we see for people living with Parkinson's disease. There is not a ton of OT specific related research, but we are going to get into some of it as I think that it is always important for us to set a theoretical basis for intervention.

Theoretical Basis for Intervention

Motor Learning

Motor learning is "a set of processes associated with practice or experience, leading to relatively permanent changes in the capacity of movement.”

- Analyze specific task and individual performance

- Practice areas of difficulty or impaired performance

- Practice the entire task

- Transfer training into varied environmental constructs

- The final goal is the optimization and automatization of motor skills

“Patients with PD often show a decrease in the retention of newly learned skill, a problem that is present even in the early stages of the disease (Marinelli et al., 2017)."

I am sure you are all very familiar with motor learning so I am not going to go deeply into it. We start with blocked practice working toward practicing the entire task with varied environmental constructs. Our final goal is always optimizing and trying to make those motor skills more automatic. It is important to note this article by Marinelli in 2017. They found that patients with Parkinson's show a decrease in the retention of a newly learned skill, and this is early on. This does not necessarily mean your more advanced patients or patients with cognitive decline or dementia. We can see this in the early stages and early on and trying to learn and relearn these skills can be very difficult.

It is important that we use a lot of practice, rehearsal, and cueing, which we are going to talk more about. It is also important with that motor learning theory that our approach is very task oriented.

Task-Oriented

- Select activities and tools for therapy from daily life

- Collaborate with client to select meaningful functional tasks

- Analyze person and environmental aspects of task performance

- Structure practice of the task and provide feedback to facilitate motor learning

- Develop optimal movement patterns for task performance

(Almhdawi, 2016)

Often, patients will come to me and complain that during previous treatment they worked on pegs and putting coins in a slot when they wanted to be able to get money out of their wallet or button their shirt. I try very hard to be task oriented. If they want to work on getting money out of their wallet, then that is what we do. What are the steps? What challenges are involved from a cognitive and motor perspective? Here in the city, it might be that people are lined up behind them. So, we will go out and try to find a crowded environment in order to practice this skill. I always collaborate with the client and want to make this salient. Always consider the personal environmental aspects. With Parkinson's, this even includes their medication times, or their on/off times. We have to think about what that is going to look like for them. We need to develop those optimal patterns for performance in consideration of all of these special factors.

Neuroplasticity

- Use it or Lose it – inactivity is pro-degenerative

- Use it & Improve it - skilled training facilitates plasticity

- Specificity – task-specific training: train to the deficit

- Repetition Matters – the key to permanent change in brain and behavior; add novel movements

- Intensity Matters – push/challenge your patient! More reps, longer duration & frequency, HR, BORG scale

(Kleim & Jones, 2008)

This Kleim and Jones article is brilliant. The area I want to highlight is this concept of intensity. You really have to push or challenge. This might mean cognitive dual tasking, motor dual tasking, balance changes, and environmental challenges. We want to make sure that we really challenge them and make them work so that we get more of that neuroplastic benefit. We also want to specifically train to the deficit, and make it as task-specific as possible.

- Time Matters – better earlier, but can occur at any point

- Salience Matters – must be important to the patient

- Age Matters

- Transference – changes in one area can promote concurrent or subsequent changes elsewhere

- Interference – learning compensatory strategies first may lead to plasticity that needs to be overcome

(Kleim & Jones, 2008)

It has to be salient and important to the patient. We really want to push them to get the transference. This Kleim and Jones article is not specific to Parkinson's and that transference with this population is a little more difficult. There have been a number of articles that speak to their difficulty with mental flexibility and generalization. So, when I say task-specific, we really have to set it up like their home environment if possible. Trying to make it as specific as possible is important. The last bullet is really important to note. If we just teach a compensatory strategy first, that may lead to plasticity that then they have to overcome at some point.

Stepwise Approach

- The therapist observes the performance of the activity to analyze which components are limited.

- Therapist supports recognition of the activity and selects the most optimal movement components; generally limited to four to six components.

- Therapist summarizes the sequence of components in key phrases, preferably supported by visuals.

- Therapist physically guides the performance.

- The client rehearses the steps aloud.

- The client uses motor imagery (mental training) of the consecutive movement components.

- The client carries out the components consecutively, consciously controlled, and if required guided by the use of external cues.

(Radder et al, 2017)

The Stepwise Approach comes out of the Netherlands. In the Netherlands, they have the ParkinsonNet which is a network of therapists that all specialize in Parkinson's. I really like this approach, and I have used this a lot with my students when they are new to the clinic. I think this lays it out a little bit more specifically where we observe and then support the person by recognizing their optimal movement patterns, and then what they need to work on as well. We need to guide their performance. There is some rehearsal here which that is one of the internal memory strategies that sometimes people need to utilize. Motor imagery includes visualization and mental rehearsal. We are training them to be more conscious and conscientious of how to move and do the things that they need to do. And, we continue those external cues as needed. We are not always going to be able to get them to the point that they are independent. They may always need a cue, especially when we get into freezing of gait or some of the mobility challenges.

OT Approach to Parkinson’s Care

These are some great practice documents that you can look to if you are interested.

- Occupational therapy for people with Parkinson’s disease: towards evidence-informed care (Sturkenboom, 2015)

- Parkinson’s disease. OT Practice Guidelines for Adults with Neurodegenerative diseases (AOTA, 2014).

- Occupational therapy for people with Parkinson’s: Best practice guidelines (Aragon & Kings, 2010), United Kingdom

- Guidelines for Occupational Therapy in Parkinson’s Disease Rehabilitation (Sturkenboom et al., 2008), Netherlands

For the Aragon and Kings, I believe there is an updated version that has come out, and Sturkenboom has also added another lens. AOTA completed a practice guideline for neurodegenerative conditions in 2014 that you can reference.

Evidence Base for OT Intervention (Foster et al., 2014)

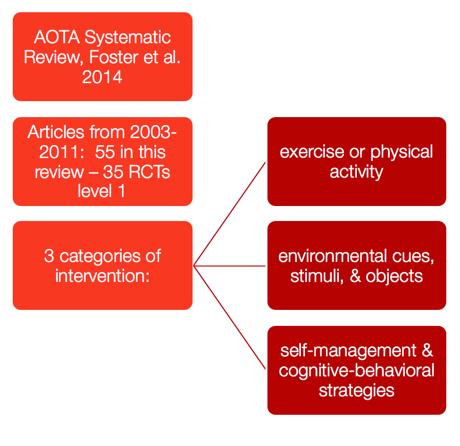

One of the strongest articles as far as research is this systematic review that was done by Foster in 2014.

Figure 1. A systematic review (Foster, 2014).

There were really three categories that emerged as far as an appropriate intervention for occupation therapy.

Interventions: Exercise or physical activity.

- To improve performance skills:

- Most responsive to task-specific

- Direct performance skill training does not generalize as well to more complex occupational performance or QOL

- Exercise improves motor performance, postural stability, & balance

- Limited evidence for postural training affecting FOF or fall reduction

The first is exercise or physical activity. Again, they need to be task specific. I really spend a lot of time discussing this with my patients to try to get as much information as I can about the environment, the context, what their bathroom setup's like, their bedroom setup, etc. They do not generalize well to more complex occupational performance measures. We know that exercise seems to improve their motor performance, their postural stability, and their balance. When they do LSVT BIG, PWR! (Parkinson Wellness Recovery), or Rock Steady Boxing as examples, we see a spread of effects. Exercise is truly medicine for this population. There is limited evidence for postural training affecting their fear of falling or fall reduction as it is a much more complex area. We need to look at the cognitive, visual, executive function as they are a very complex mix. It is not just a movement disorder. It is very poorly named in my opinion.

Environmental cues.

- Evidence for:

- use of auditory rhythmic stimuli

- providing a safe movement environment for focusing on the functional task

- cueing paired with cognitive strategies

- cueing on the amplitude of movement

- adaptive equipment for safety against falls

We are going to get more into cueing later, but they do respond well to rhythmic auditory stimuli. However, it is not just turning on a metronome for the freezing of gait. There are not metronomes in life, and many times, they are hard to use. While it is a tool, you have to consider how this is going to transfer to the real world. We want to provide a safe environment, so they can focus on functional tasks. For example, with dressing, we are going to get into how they might need to be seated. Cueing often needs to be paired with some cognitive strategies like possibly breaking down a task into more simple steps. The amplitude of movement cueing is absolutely key and essential across the board for ADLs and IADLs. If you have not taken LSVT BIG, Parkinson's Wellness and Recovery, or some program that teaches you about amplitude, I encourage you to do so. We also need to use adaptive equipment for safety to prevent falls. Often, I have to talk to people early on about why I am recommending that as a safety measure.

Self-management and cognitive behavioral strategies.

- Promoting wellness initiatives & personal control

- Help with modifying lifestyles and improving QOL

- Use a “cognitive–behavioral intervention that involves education, goal setting, performance skill training, practice, and feedback related to incorporating habits into daily life.”

These become very important. We want to promote wellness initiatives. I served as a facilitator for PD SELF, working on self-efficacy and education, and run a book club for people with Parkinson's. I want to try to give them every tool possible. I also do a lot of support groups. I want them to feel that they are empowered and have a sense of control so that they can improve and modify their lifestyle to promote quality of life. They need a cognitive-behavioral intervention. We can tell them to exercise, but when are they going to exercise? Where are they going to go to exercise? What are their barriers to exercise?

Early on in my career, the Jay Alberts Study had come out of the Cleveland Clinic. Doctors were literally sending people to me with a script that said that they needed to cycle 80 to 90 revolutions per minute for 30 minutes, six times a week. I would ask this little 80-year-old sitting in front of me, "When is the last time you exercised," or "What's your exercise routine like?" They might respond, "I haven't exercised for 30 years," or "I've never exercised." That is a problem. We have to try to help them figure out how they are going to reach that goal and be practical at the same time. Never assume that they can just take these habits and put them in their daily life.

Interventions for ADLs

Let's get into what the interventions look like specifically for ADLs. I have tried to hit the high points here.

Symptom Impact on ADLs

These are the symptoms we talked about last time that really impact their ADL performance.

- Rigidity

- Bradykinesia

- Posture

- Balance

- Hand dexterity

- Executive dysfunction/multi-tasking

- Visual/Perception

- Organization

- Coordination

They can have difficulty threading an arm into a sleeve of a coat or buttoning up a shirt with rigidity. With bradykinesia, their movements are slow. Even if they are still independent, often their performance is much slower. Their posture can be problematic for reaching behind or different movements can be difficult because their posture is so nonfunctional. If they are having to struggle to stay balanced while they are putting on their pants or putting on a shirt, this certainly can cause some problems. They definitely have issues with hand dexterity, fine motor coordination, and limb-kinetic apraxia impairing their ability to manipulate buttons, zippers, or fasteners.

It is not just motor impairment that we see. They can have executive dysfunction and trouble sequencing and planning Multitasking becomes really difficult. Again, this can be early on. This is not just in your late-stage patient with dementia. Visual perception can be impaired. And, I find that a lot of times with that breakdown of executive function, they become more disorganized, and their spaces are more chaotic. Finally, they have trouble coordinating their movements and planning how to perform tasks as their dopamine levels affect automatic movement. And when there is not enough dopamine, the automatic movements now have to be planned.

Time Pressure Management

- Based on Michon's task analysis, describing levels of decision-making in complex cognitive tasks

- Provides patients with compensatory strategies to deal with time pressure in daily life

- Individual must recognize a deficit and need for change

- Requires awareness to recognize and anticipate time pressure situations and identify a strategy for use

- Motivation is needed to learn the strategy

- Training should be adjusted to the patient's individual learning abilities and cognitive skills

(Fassotti et al., 2009)

Time Pressure Management comes from brain injury literature. I use this a lot in my patients that are having trouble getting out of the door on time or are very bradykinetic. In fact, I was just using it this morning with a patient. It looks at task analysis and decision-making for complex tasks. You are trying to provide compensatory strategies to help them deal with the pressures of getting out of the house for an appointment or to a meeting on time. They have to recognize a need for change in order to get buy-in. With the gentleman this morning, I was able to walk him through the issues that happened when he was trying to prepare to leave the house and discuss how he had not allowed enough time. He was only allowing the amount of time he did before his symptoms kicked in. He was motivated to learn a strategy and talk through it. His thinking is a little slower, and he needed some cues and prompts. They definitely have to adjust.