Dianna: Thank you, everyone, for being here to talk about the trigger finger. This is a topic that seems so simple at times, but it can also give us such a headache. I am glad to have the opportunity to give you some updates on the evidence. Today, we are going to talk today about a conservative approach from a therapy perspective.

Definition

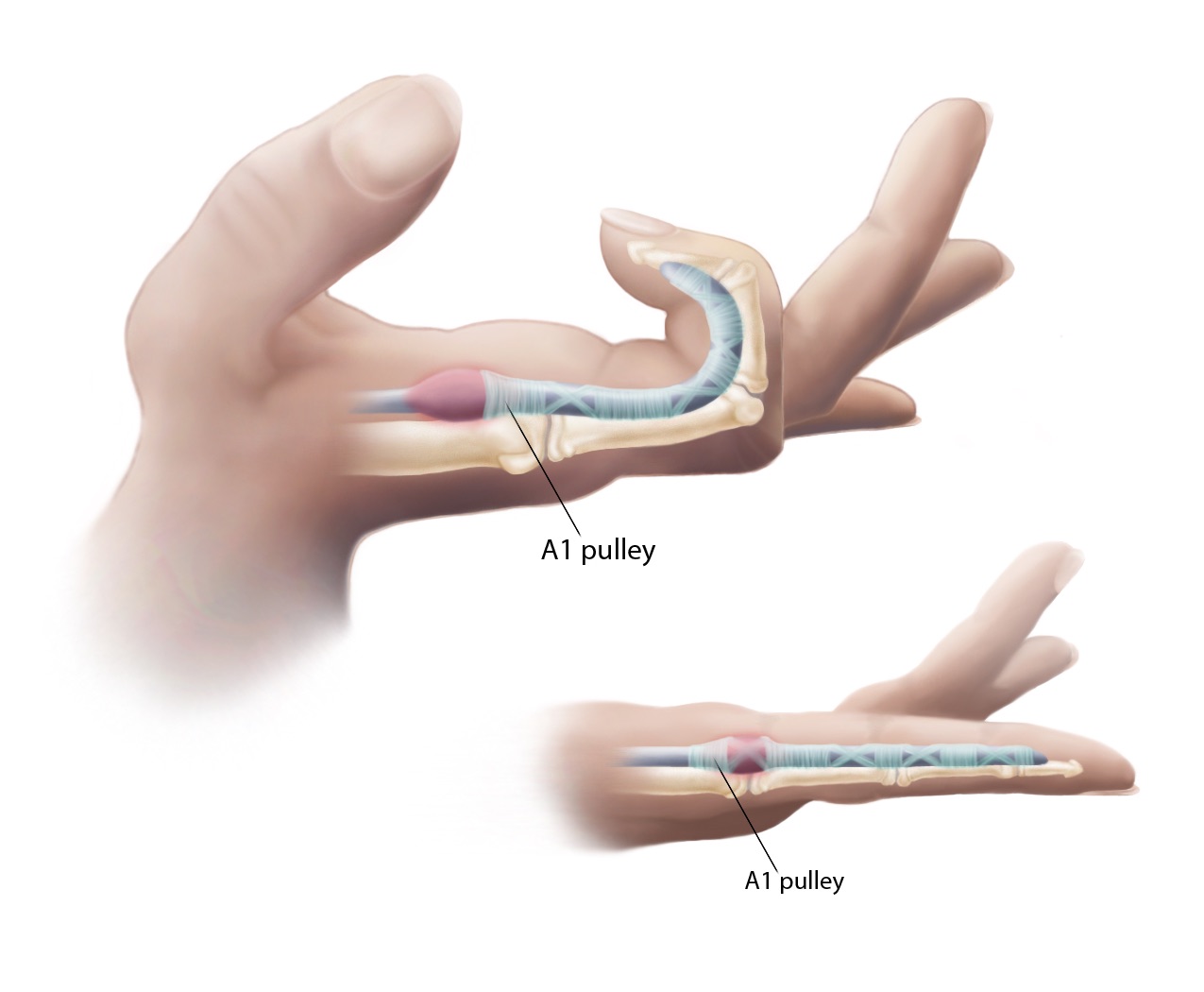

Trigger finger is described as a discrepancy in size between the flexor tendon or the tendon sheath, and the first annular pulley, which may cause pain, catching, and/or locking of the finger. This is believed to be the result of an inflammatory process or thickening of the tissues that can result in less than a smooth motion. In some advanced cases, the finger can lock up in either flexion and extension. There may be a painful, palpable nodule noted in this area as well. One of the causes may be repetition with forceful grasping or consistent digital flexion. This can contribute to this inflammatory process. It causes friction as the tendon passes through the pulley system.

Prevalence

The prevalence of trigger finger is in about 2 to 3% of the general population. This does not seem like that much, but if you think of the entire population, that is a rather high number. This number rises when there are some comorbidities as we will mention in a moment. It is very common in middle-aged women, and it affects the dominant side more, especially the ring and the long finger. The incidence goes up with things such as rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes mellitus, and carpal tunnel syndrome. This is because of the inflammatory processes that go along with those diagnoses as well.

In Figure 1, you can see where the A1 pulley is located. It is at the head of the metacarpal on the flexor surface, and this provides a tunnel for the tendon or tendons to run through.

Figure 1. Trigger finger- A1 pulley.

Anatomically speaking, the pulley is preventing a bowstring from happening when we close our fingers into a fist. The flexor digitorum superficialis and flexor digitorum profundus run through a tendon sheath which then goes through that pulley system.

Terms to Understand

Now, I am going to go over some terms that I will use throughout the presentation.

- Valid- when something measures what it is intended to measure

- Sensitivity: how likely it is that a test will pick up the presence of a disease (if the test is highly sensitive, and a person tests positive, it is a true positive)

- Specificity: a measure of a screening based on the probability that a person will test negative and does not actually have the disease

- Reliable- the degree of consistency which an instrument (or rater) measures a variable

- Clinically significant- when the effect size is large enough to alter practice approaches

When we are looking at an outcome measure as being valid, this is telling us that it is measuring what it is intending to measure. And within that, we are looking at that tool being sensitive and/or specific, and those are generally rated. If a diagnostic test is sensitive, this is describing how likely this test will pick up the presence of a disease. We want a true positive with a test that has high sensitivity. Another way to state that is that if a test has high sensitivity, then if the result is negative, you can be certain that you do not have the disease. Conversely, if a test is specific, it is based on the probability that a person will test negative. If they do test negative, then they do not have the disease. When we want an outcome measure that is reliable, this is saying that what we are measuring is consistent. It is the degree of consistency in which something is measuring a variable. That is also another important term when looking at outcome measures. If something is clinically significant, that means that the size of the effective change is enough for us to pay attention to it to alter our practice patterns.

- Patient-reported outcome measure-an outcome measure gives information about a patient’s condition that comes from the patient that is not interpreted by the clinician

- ICF-International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health-defines and measures health and disability

- Minimum detectable change: smallest amount of change that can be detected by a measure that corresponds to a noticeable change in ability.

Many times, we use things that we are comfortable with, but unfortunately, some of those measures do not necessarily come from the patient themselves. It is really important for us to use patient-reported outcome measures because this gives us information about the patient's condition that is subjective to the patient.

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) is a really important document. Our Occupational Therapy Practice Framework (OTPF) language was based on the ICF that was created by the World Health Organization. They created this document to help us define and measure health and disability and is being used internationally. Additionally, the ICF looks at the person in a very holistic manner. It is not just identifying the body functions or structures, but it is also looking at the person as a whole. It looks at how the person engages in occupations, is able to engage in performing those occupations, and at what level. It also addresses environmental factors from a micro standpoint and a macro standpoint. A micro standpoint is environmental factors that we can change right now like a piece of equipment or an orthosis. The macro aspect might be something broader like social politics. The ICF looks at all of those things.

Finally, a minimum detectable change is the smallest amount of change that can be detected by a measure. This typically corresponds with a noticeable change in ability or the amount of change in a patient's score that lets us know it is enough of a change that it is not due to an error in measuring. Range of motion is probably a good example of that. This should not be confused with a minimally clinically important difference, which represents the smallest amount of change in an outcome that would be considered important by the patient. It is more focused on the patient's perspective

These terms are important as we start looking at our outcome measures and seeing if what we are testing is helpful to identify that change.

Evidence-based Practice (EBP)

Evidence-based practice is not new. You can see here from my reference that this is information from Sackett from 1996. In the last several years, it has become a very hot topic. Evidence-based practice includes three things that have been identified.

- Best available evidence

- Clinician’s expertise/experience

- Client preference

(Sackett, 1996)

The first thing is the best available evidence. The best available evidence is as current and the highest quality as we can get. We are looking at for the best available evidence. A clinician's experience or expertise plays into being an evidence-based practitioner. Sometimes, we do things because we have always done it that way, which is not necessarily being an evidence-based practitioner. However, other times we do things because we have seen them work and we continue to do them. The evidence may not support what we are doing, but this does not mean it does not work. The evidence may not have caught up with what we are currently doing. So, we want to take our clinical experience into consideration. Finally, client preferences should be taken into consideration. We can say that there are certain diagnoses that an orthosis is great for and the evidence supports it, but if the patient tells us, "I'm never going to wear that, you can just put that away", we need to take that into consideration.

All of these things have been espoused by Sackett for a long time. Some people say that there should be a fourth added to this, and that would be reimbursement. We all know that if we cannot get reimbursed for something, it is really difficult to stay in business. This is something that we have to consider as well.

Assessment/Outcome Measures

We are going to talk about outcome measures, and this is the list that we are going to go through.

- Classification system: Stages of Stenosing Tenosynovitis (SST)

- Disabilities of the Arm Shoulder and Hand (DASH/QuickDash)

- Patient Specific Functional Scale (PSFS)

- Dynamometer (strength-grip test)

- Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM)

- Number of triggering events

- Tenderness over the A1 pulley

- Pain level assessment

- Numeric Pain Rating Scale (NPRS)

- Visual Analogue Scale (VAS)

We are going to start with the stages of stenosing tenosynovitis. Stenosing tenosynovitis is another term for trigger finger. We are also going to briefly talk about the Disability of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand, the DASH, and the QuickDash. We will mention the Patient Specific Functional Scale, use of a dynamometer, and the COPM, or the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure. We will talk about what the number of triggering events and how that was used in a particular study. We will discuss tenderness over the A1 pulley and the use of common pain assessments as listed here.

Stages of Stenosing Tenosynovitis (SST)

Up until about 10 years ago, I did not even know that there were stages that could be categorized. This was news to me when I started really digging into the literature about trigger finger. At the time, I was seeing a fair amount of this diagnosis. These categories originated in 1980 from someone named Quinnell. It was then modified later in 1992 by Patel and Bassini.

These stages describe finger movements and each stage may be painful or painless.

- Stage 1-Normal

- Stage 2-uneven motion of the tendon

- Stage 3-triggering=clicking=catching

- Stage 4-locking of finger in flexion or extension and

- unlocked by active motion

- Stage 5-locking of finger in flexion or extension and unlocked by

- passive motion

- Stage 6-finger locked in flexion or extension

(Classification system by Patel and Bassini, 1992, modified from Quinnell, 1980 and noted by Evans et al., 1988)

This identifies six stages, starting with the normal movement of the digit and going all the way to a finger that is locked in flexion or extension. Each stage could have pain, but it is not a given that someone was trigger finger has pain. It would make sense that they do, but you cannot make that assumption. Some may be worse than others, but we know that the pain experience has many components to it. It is not a valid or reliable tool; however, it is objective. I find it to be very helpful for myself in categorizing where someone is. Stage 1 is a normal digit without having any issues at all. Stage 2 is the uneven motion of the tendon, not a smooth glide. In Stage 3, we are triggering, which could be likened to clicking or catching of the finger. By the time they are at Stage 4, the finger is locking and getting stuck, but it can get unstuck with active motion. In Stage 5, the locking of the finger cannot be unlocked actively, and it needs to be unlocked passively. We see our patients either pull their finger out or use something like a table to help pull their finger out of flexion or out of extension. I have not seen too many folks in Stage 6. Most people end up at their primary or their orthopedic before they have a finger that is actually locked in the flexion or extension position.

Can you identify this stage?

This is what I would call Stage 4. It is getting stuck in flexion, and it requires active motion to get unstuck.

DASH/QuickDash

Next, I want to talk a little bit about the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand, the DASH, and the QuickDash.

- Self-reported assessment of function

- Free

- From Canada

- Questionnaire using a Likert scale to rate function

- Calculates the level of disability in %

- Widely used and accepted in assessing clients with disorders of the UE/Hand

- Valid and reliable tool (Gummerson et al., 2006)

DASH-30 questions-12.7 point change is clinically significant (Mintken, PE., 2009)

QuickDash-11 questions- 8 point change is clinically significant (Mintken, PE., 2009)

This is a self-reported assessment of function. Again, it is important for our patients to tell us without our interpretation of how difficult their tasks are and what their performance looks like. The DASH and the QuickDash do just that. It is a free form that you can get off the internet, and it comes out of Canada. It is a questionnaire that uses a Likert scale to rate their function from one to five, and it calculates their level of disability in a percentage. It is widely used and accepted for assessing clients with disorders of the hand in the upper extremity. I have used it quite a bit. It is considered a valid and reliable tool with two versions. The long version is 30 questions, and the QuickDash is 11 questions. The long version requires a 12.7 point change and the QuickDash is an 8 point change to be clinically significant. This means that if a patient's score changes that much, then we should pay attention to what we are doing clinically. The DASH and the QuickDash have pre-determined activities such as using a knife to cut your food, opening a new jar, doing heavy chores, or carrying a shopping bag or briefcase. However, from a cultural sensitivity standpoint, they might not be appropriate for everyone.

Patient Specific Functional Scale (PSFS)

The next tool that I want to mention is the Patient Specific Functional Scale.

- Free valid and reliable tool that is easy and quick to use (about 4 min)

- From Canada (Stratford et al. 1995)

- Responsive to change over time (clinically relevant)

- Uses an 11 point Likert scale; 0=Unable to perform task-10=Able to perform task at prior level of function

- Patients identify 5 important functional tasks and are asked to rate before intervention and after intervention (once achieved, may introduce 5 new items)

- Is scored with the sum of the activities divided by the number of activities

- Minimum detectable change for the average of scores is 2 point difference and 3 points for a single task

http://www.tac.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/27317/Patient-specific.pdf

I really like this scale. It is another self-reported assessment of function that is used mainly for musculoskeletal disorders. It is also free, you can get it off the internet, it is a valid and reliable tool, and it only takes about four minutes to administer. It comes out of Canada, and it is responsive to change over time which is nice since it is used often for reassessment. It uses an 11-point Likert scale. A zero means the client cannot do the task all the way to a 10 where they are independent. However, different than the DASH or the QuickDash, the patient gets to identify five tasks that are functional, but important to them. Again, this is important as you cannot make an assumption that everyone is engaging in household tasks, opening jars, or carrying a briefcase. Once they have achieved their first five, they can introduce another set of five. The scoring is a simple math equation as the sum divided by the number of activities. The minimal detectable change for the average of all the scores is a two-point difference and three points for a single task and the above website is where you can get the form.