What We Will Be Covering

- What is “hands-dependent sitter”?

- Clinical Guidelines

- Case Study

We are going to define what this funny term is in relation to the other categories of people requiring wheelchair seating support. We are going to talk about the clinical guidelines for someone within this category and what we need to keep in mind in terms of seating assessment and interventions. And then, we are going to wrap up with a case study that, hopefully, will be a good way of putting all of this information into context.

SMS Series

- This is part of a series of webinars designed to prepare the participant for the Seating and Mobility Specialist examination

- And… develop more advanced seating and wheeled mobility skills

This course is part of a series designed to prepare you for the Seating and Mobility Specialist examination. The SMS certification is an examination through RESNA, and this is something that you might want to explore, especially if you do a lot of wheelchair seating and mobility. There is a whole process for becoming an SMS. The first course in the series provided an overview of that process and why you may want to consider that particular certification including the requirements, the prerequisites, and the examination. I hope this information helps you to develop more advanced seating and wheeled mobility skills.

Seating and Wheeled Mobility

- Every mobility base includes some form of seating

- Primary supports include the seat, back, armrests, and footrests

- Seating interventions vary tremendously depending on the client age, diagnosis, prognosis, postural needs, pressure risks, etc.

Every mobility base, whether it is an adaptive stroller, a manual wheelchair, a power wheelchair, a power-operated vehicle, also called a scooter, etc., requires some form of seating. You need to sit down when you are using them. Primary supports include everywhere that weight is being supported. That is the seat, the back, the armrests, and footrest. From there, the seating interventions that we use are going to vary quite a bit. It is going to depend on many individual factors like age, diagnosis, prognosis, postural needs, pressure, risk, and all sorts of things.

Postural Needs

- One way of looking at wheelchair seating is by postural support needs:

- Hands-free sitter

- Hands-dependent sitter

- Prop sitter

One way of categorizing the people that we work with, who require wheelchair seating, is by their postural needs. We can further divide this into people who can sit without the support of their hands, or the hands-free sitter, the hands-dependent sitter, what we are focusing on today, and the prop sitter. A hands-dependent sitter is someone who needs the support of their hands in order to stay upright. Let's define each of these.

Hands-free Sitter

- The person is able to lift their hands off of the surface without changing the position of the trunk

- Can also shift weight to the side and return to a midline position

- Good trunk control

The hands-free sitter is a person who can take their hands off of the surface they're sitting on like this woman here is sitting on a mat table (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Example of a hands-free sitter.

Rather than having to have her hands on that mat surface, she can place them in her lap. She is not falling over. Her position may not be ideal, but she can stay relatively upright. The hands-free sitter can shift their weight somewhat to the side and return to midline without falling over. This woman should be able to lean a little bit to the side without putting her hand out. This requires good trunk control.

Hands-dependent Sitter

- This person uses one or both hands on a surface to maintain sitting balance

- If hands are lifted, the trunk will collapse

The hands-dependent sitter, who we are talking about today, needs their hands on the surface in order to stay upright (Figure 2).

e

e

Figure 2. Example of a hands-free sitter.

They may support themselves with one or both hands, and if the hands are lifted, their trunk is going to collapse. This is a common developmental stage for infants. Before kids can independently sit upright, this posture is very common. They will have their hands out on the floor, and if they lift a hand to reach a toy, they will fall over. Fairly soon after that stage, the child gains enough sitting balance and trunk control that they can reach out with a hand. And eventually, they can use both hands to grasp things, to rotate their trunk, to lean to the side, and are able to stay upright. While everyone goes through a hands-dependent sitter stage, some of our clients continue to need more support either due to a congenital or acquired issue.

Prop Sitter

Then finally, there is the prop sitter. This person cannot maintain independent sitting, even if they can place their hands on a surface. They need a great deal of external support. This young man (Figure 3) has a lot of flexion in his arms, and he really cannot get his arms down to the surface.

Figure 3. Example of a prop sitter.

Hands-dependent Sitter

Goals

- Provide adequate proximal support for distal control

- Optimize function

- Prevent the development of asymmetrical postures

- Mitigate pressure issues

What are our goals when we are working with the hands-dependent sitter? We want to provide adequate proximal support close into the body to allow for distal control and stability. For example, you might be sitting in front of your computer watching this course right now. You are able most likely to keep your trunk upright and balance your flexors and extensors. You have an intrinsic amount of stability to maintain an upright posture. Now, sure, sometimes you might get tired and put your arms on the desk in front of you. You are leaning on there to get some support, but you can readily lift away from there and keep yourself upright. If you need to reach out and grab that mouse or type on the keyboard, you can because you have the proximal stability to allow you to disassociate your arms to use it in an isolated way for fine motor control. For people who are hands-dependent sitters, we need to give them enough proximal support, close to their body, to compensate for their lack of intrinsic stability. The seating system provides extrinsic stability. They can then disassociate their extremities and head so that they can move and have that more refined distal control. This is a great deal of what we do with the hands-dependent sitter. We hope that by doing that we are optimizing function for this person. We cannot be functional if we have our hands supporting us the whole time. If this person still does not have strong hand or upper extremity control, we are freeing up other parts of the body for function.

We also want to prevent the development of asymmetrical postures. Someone who lacks intrinsic core stability tends to collapse at the trunk. This can quickly lead to a more permanent asymmetry of the spine for example at the pelvis. We want to prevent that if we can. If it is already present, we need to deal with that within the seating system.

And then, while we are looking at stability and function and maintaining alignment, we also have to make sure we are being mindful of pressure. We need to make sure that there is not too much pressure in certain areas for this person as many clients are often at risk for developing pressure injuries.

- With hands lifted, the trunk will collapse.

- The client can typically sit hands-free with support provided posterior and lateral to the pelvis and posterior to the lumbar thoracic area.

This type of client can typically sit hands-free if they have enough support posterior and lateral to the pelvis as well as posterior to the lumbar thoracic area. What does that mean? This person on the mat table may have their hands down on the surface, but if we give them enough support behind into the sides of the pelvis, this person can often sit with very little other support. Figure 4 shows a young man here in an activity chair. He cannot sit independently on his own, on the floor, or on a mat. However, in this activity chair, he has some nice strong support behind his pelvis with the back of this adapted sitting system. He also has lateral pelvic and lateral trunk supports. With all of this, he can sit up very readily, free up his hands, and he is reaching out to a tablet for communication.

Figure 4. Example of activity using increased support.

Clinical Guidelines-Assessment

What are some things we need to keep in mind in terms of assessment?

- Observation of seated posture

- Mat Exam

- Postural support requirements

- Range of motion

- Sitting balance

- Muscle strength

- Sensory status

First, we need to observe the clients current seated position as in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Example of seated posture in a wheelchair.

Then, we need to complete a mat exam. There are a number of things that you need to keep in mind, including the amount of support this person requires to stay upright, their available range, sitting balance, muscle strength and sensory status, particularly sensation that is going to directly relate to pressure risk.

- No matter what level of postural support is needed, it is important to observe how the client is positioned in the current seating system

- Note your findings

First, I want to look at how the person is already positioned. I need to look at the position of the pelvis, spine, extremities, the head, etc. and write that all down, I might take some photos as well. These photos can then help me determine if we have improved this person's posture after an intervention. These can also be educational. For example, the young woman, in Figure 6, told me that nobody had ever shown her a picture of her posture before. After some adjustments were made, she then could appreciate the difference between the two. She reported that that was very helpful to her.

Figure 6. Another example of seated posture in a wheelchair.

I often include photos in my documentation. I like to educate the funding source at that stage to show them a client's current posture, and then, another showing what I am trying to accomplish and why. No matter what level of partial support is needed, it is important to look at how the client is positioned in their current system and note those findings. The client in Figure 6 is actually a prop sitter. She can sometimes sit hands-free and sometimes hands-dependent but she is mostly a prop sitter. It depends on the task and her movement. She has cerebral palsy and apoptosis. If her movements are relatively quiet, sometimes she can sit completely independent on a toilet, while other times, she needs a lot of support. This is especially true when she is trying to use her body. In Figure 6, she is trying to control her power chair with her joystick. She has an arm tucked underneath in between her legs and her left leg is wrapped around the bottom of the right leg. Her left arm is also behind the back of the chair. She is hanging on trying to find some stability. A great deal of what we did in her seating system was to find that stability for her so she did not have to contort her body and instead was freed up to be functional.

Mat Examination

- Mat Examination

- Sitting on edge of the mat table

- Without the support of hands, the trunk will collapse

- Collapse may be posterior (kyphosis and posterior pelvic tilt)

- Collapse may be lateral (scoliosis with or without pelvic obliquity)

- Without the support of hands, the trunk will collapse

- Sitting on edge of the mat table

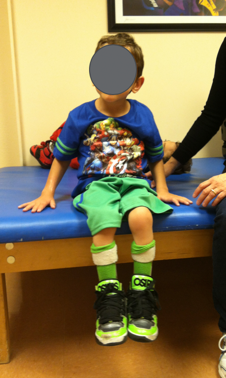

We then move into the mat examination. Now in this series of webinars, we have a webinar dedicated completely to a mat assessment. I would encourage you to check that one out. We are briefly going to talk about the mat examination when it comes to the hands-dependent sitter. We are going to place the client sitting on the edge of the mat table as we have done with this young man here in Figure 7. If he lifts one or two of his hands, he is going to collapse. That collapse can be posterior, where the back of the pelvis rocks into a posterior tilt and the spine becomes flexed or kyphotic. We also might see collapse laterally, where one side of the spine become shorter. We might also see some pelvic obliquity, where one side of the pelvis is higher than the other.

Figure 7. Hands-dependent sitter at the edge of a mat.

Range of Motion

- In supine on the mat table, it is very important to determine how much available hip flexion the client has.

- This determines the seat to back angle

- *See The Mat Assessment course

Then, we place the client supine on the mat table. It is important to determine how much available hip flexion the client has as this is going to determine the seat to back angle of the wheelchair frame and seating system. In the aforementioned mat evaluation, we have some videos showing how to determine available hip flexion angles. In Figure 8, it might be difficult to see, but he has a tendency where both of his legs want to go to one side a little bit, called a windswept tendency. His pelvis is also a little oblique where he is higher on the left, and he is rotated forward a little bit on the right. His left leg is a little more abducted and externally rotated, while his right leg is a little more adducted and internally rotated. These are his postural tendencies. Our job is to determine if we can correct those.

Figure 8. Hands-dependent sitter in supine.

In supine, we have to determine how much available hip flexion the client has. We have to check the hamstring range with the hips flexed as well. The first thing we do is bring the legs upward into flexion. If I start flexing the client's hips and the pelvis starts rotating back into a posterior tilt, I know I have reached the end range in terms of hip flexion. I can think that I am getting great hip range, but if I am losing the position of the pelvis, I do not have a true angle measurement. I flex the hips until the pelvis starts moving, and that's my available hip flexion.

- Also, check hamstring range with the hip flexed at approximately 90 degrees.

- Determines the angle of knee/footrest hanger

To check the hamstring range, we keep those hips flexed at about 90 degrees if the client has that degree of range. Most hands-dependent sitters should have that much range of motion. Then, I am going to slowly extend at the knee to determine how much hamstring range I have. This will determine the angle of the knee in sitting. And, as a result, the angle of the footrest hanger. Again, we need to know how much range is at the hips to determine the seat to back angle of the wheelchair seating system. Then, how far we can extend that knee before the pelvis starts to move.