Editor's Note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Joint Hypermobility Syndromes: Assessment and Intervention, presented by Valerie Calhoun, MS, OTR/L, CHT.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to identify criteria for the diagnosis of joint hypermobility syndrome.

- After this course, participants will be able to list two common concerns patients with joint hypermobility of the hand joints report.

- After this course, participants will be able to list one occupational therapy intervention for patients with reported hand pain with writing.

Introduction

Today, we will discuss the assessment and intervention of joint hypermobility syndromes. You may not have recognized this disorder, but you have probably seen some symptoms. This course will cover upper extremity assessment and treatment strategies for the pediatric and young adult population affected by joint hypermobility syndromes.

Treatment focuses on orthopedic treatment strategies and adaptation for these individuals. There are a couple of reasons I am focusing on pediatrics and young adults. First, this is where my experience lies, and these are primarily the ages of the patients you are going to see. This is because ligaments and connective tissue become less pliable as we age. Thus, we do not see adults that are hypermobile very often.

Joint Hypermobility Syndrome

- Joints move beyond the “normal” joint range.

- Can be local to a specific set of joints or generalized

- Not related to a specific activity

- Can be syndrome-related

- May be inherited

What is joint hypermobility syndrome? This is a catch-all phrase where sets of joints move beyond their "normal" joint range. This does not affect just one joint but typically a set of joints, or it can be generalized to all joints. And it is not related to a specific activity. Some individuals have hypermobile joints based on the activity that they perform. For example, if I push a widget with my thumb all day long for a job, I may have increased hyperextensibility in the IP thumb joint and nowhere else in the body. And most of these syndromic hypermobility conditions are inherited.

- Generalized (non-syndromic) is the most common

- Syndromes:

- Ehlers Danlos Syndrome (EDS)

- Marfan Syndrome

- Heritable connective tissue disorder

- Impairment of collagen

The generalized, non-syndromic population is the most common. Some syndromes also have hypermobility of joints, like Ehlers-Danlos syndrome or EDS. This condition is probably the most researched. Marfan syndrome also has joint hypermobility. There are also heritable connective tissue disorders, which is more of a generic term.

Hypermobility syndrome is an impairment of the collagen which allows the joints to become hypermobile.

EDS

- 6 subtypes

- Diagnosed through genetics

- Can have further complications

- POTS; Tethered cord; cardiac/vascular abnormalities

- National Foundation: www.EDNF.org

There are six subtypes of EDS; some involve cardiac conditions and other life-threatening conditions. They typically get diagnosed by a doctor. The only way to truly diagnose EDS is through genetics testing. Family members usually know when their children start to show symptoms because somebody in a previous generation has already been diagnosed. They can also have further complications, such as POTS, a tethered cord, and cardiac and vascular abnormalities. The National Foundation for EDS is a great resource.

EDS Symptoms: Joint Hypermobility

- Many are asymptomatic.

- Joint hypermobility

- Joint pain

- Subluxations/dislocations

- Skin/organ involvement

- Pain

- Loose skin

- Drooping eyelids

Many clients are asymptomatic. You may never see these individuals until they have an injury or come to your clinic with other complaints. If you are familiar with joint hypermobility symptomology, it will help you determine what is causing their problems. Many have joint pain with hypermobility but do not fully dislocate because their ligaments and joint capsules are intact. They are extra pliable and will subluxate. An example is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Example of a hypermobile thumb joint.

They also often have skin and organ involvement because they are made of collagen. They may have loose, fragile skin and droopy eyelids.

EDS Symptoms

- Muscular Pain

- Joint instability

- Having particular physical characteristics called Marfanoid habitus – this includes being tall and slim and having long, slim fingers

- Hernias

- Varicose veins

They often have muscular pain as their muscles overwork to stabilize the joints. There is also joint instability, where they feel like their joints are coming out due to instability. Some syndromes have particular physical characteristics like Marfanoid habitus as part of Marfan syndrome, a tall, slim frame with long and slender fingers and a long face. They may have frequent hernias due to the laxity of the abdominal wall and varicose veins.

EDS Diagnosis

- May see you prior to a formal diagnosis

- Screen with active range of motion

- Diagnosed based on symptoms

- Blood tests with specific syndromic conditions

I frequently see these individuals before any formal diagnosis of hypermobility syndrome. They typically come to OT because they cannot do an activity or they have pain. Sometimes, they go to their doctor, who then refers to us to screen them. We then see them for active range of motion, joint stability, and assessment of symptoms.

When they have joint hypermobility, but it is not heritable, there is no genetic test to perform. If it is syndromic, there are tests to diagnose them. Our job is to determine what is causing their problems because we cannot address a problem without knowing why. I do not diagnose them, but I can tell them what is causing their pain or difficulty with activities.

EDS Beighton Scale

- Both elbows

- Both knees

- Thumb to forearm

- Both small finger MPJ extension (greater than 90º)

- Trunk flexion

- 9 points total

- Validated in children for greater than or equal to 5 points

There is one tool called the Beighton scale. There is a lot of research on this tool, primarily completed by the rheumatologist and rheumatology groups. This research has concluded that the scale is not a diagnostic tool but a descriptive one. If they score anything equal to or greater than five points, they will fall under "the general category of joint hypermobility."

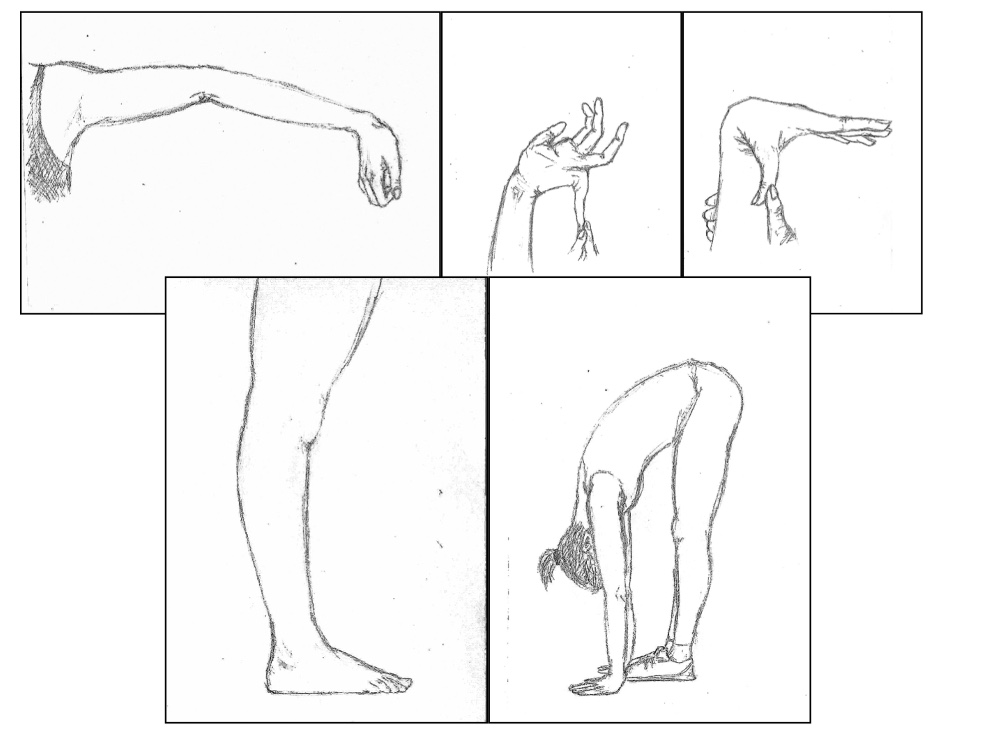

The Beighton scale is a movement scale and is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Beighton Scale.

There are nine total points. You have them move their joints to their fullest extent, and they get points if there is hyperextensibility. You score elbows, knees, thumbs, little fingers, and spine. These movements are done passively, and if you get greater than 90 degrees, then that is one point for each side. For trunk flexion, they stand with their knees straight, bend down, and put their palms flat on the floor. Here are some images of the Beighton scale in Figure 3.

Figure 3. This shows hyperextension in the knees, elbows, and spine.

Figure 4. Hyperextension in the little finger and thumb.

Again, this is a screening tool if you suspect hypermobility in an individual and cannot be done very easily on infants. It is used for children aged eight and up. Many kids do these movements as "party tricks."

EDS-Why Do They Seek Treatment?

- Joint subluxation or dislocation/repeated

- Joint pain/muscular pain

- Weakness or fatigue

- Repeated soft tissue injury

- Limitations in function

Typically, they seek treatment due to a repeated joint subluxation or dislocation, not for a traumatic reason. "I was reaching up into the cabinet, and my shoulder came out," or "I was reaching back to fasten my bra, and my shoulder came out." Injuries occur with regular daily activities.

One of the main reasons individuals go to the doctor is they have chronic joint or muscular pain, are weak, or feel fatigued because their muscles are working so hard. They may also have soft tissue injury from their muscles being stretched so far.

EDS-What Brings Them To OT?

- Injury or subluxation

- Pain: generalized or specific

- General weakness and fatigue

- Handwriting difficulties: pain with writing

- Difficulty with specific daily tasks or sports

- They come to you with a problem, and you help figure out the cause of the problem.

Why do they come to OT? Again, they may come for a specific injury or a subluxation. They may go to a hand clinic or a general ortho clinic after an injury for "strengthening." Many kids I see come in for handwriting due to pain around the ages of 8 to 10-years-old when they have more writing assignments. They may also have difficulty with daily tasks or sports, either pain- or weakness-related.

EDS-Referral Sources

- Parents request

- Pediatrician

- Internist

- Specialist

- Pain management; ortho; neuro; genetics

- School request: Usually, handwriting

Referrals come from parents, teachers, pediatricians, and specialists. Parents and teachers may complain that the child's handwriting is messy or they are having issues with particular activities. Or, they may need help opening their lunch containers. A pediatrician may refer an infant if they have difficulty with fine motor development or appear weak. If the child is a little older, an internist or general practitioner may refer them due to pain, repeated injuries, or post genetic testing.

EDS-Treatment Team

- Physician: general, ortho, pain management, rheumatology

- OT/PT

- Pain management provider

- Orthotist/OT

- Psychologist: for pain patients

The treatment team can be a little bit varied. There is always a physician involved, either a specialist or a generalist. It does not matter as long as they understand the condition and what is happening. Both OT and PT are typically involved. When they are infants, they are usually seen by PT first because they are not making progress in their gross motor development, like rolling or demonstrating flopping with their hips out into wide abduction. Many of my referrals will come from PT. They will say, "I'm noticing that they're not extending their thumbs well," "they're not resting on their hands when we're trying to get them to prop," or "their elbows are going to hyperextension." They may come from a pain management provider. Another team member is the orthotist. Some of these children end up with AFOs or some type of lower extremity bracing to assist them as they become mobile until they get stronger. It is hard to strengthen them in a standing position if they cannot stand without everting their feet. If they have a lot of pain, a psychologist may also treat them.

EDS-OT Evaluation/Assessment

- Active range of motion:

- General

- Specific to joints with problems

- No need to stress joints with PROM

- May assess ligaments

The first thing you need to do is get a good history. Why are they coming to see you? What is the specific problem, and how is it limiting them functionally? They may say that their hand hurts, but you also want to know when it hurts, what activities, and what they do to make it feel better. If they cannot tell me, I try to get a history from the parents. An interesting thing about working with young kids is that if something is not hurting at that moment when you ask, they will not report any pain. Their parent will tell another story. "Every time he sits down to do his homework, he says his hand hurts after about 5 minutes."

I look at their overall active range of motion. I start with their upper extremities and look for either limited motion or hypermobility. I usually see some hypermobility in their shoulder when they reach behind their back with internal rotation. I also may see it with elbow extension and in the digits. If I see this, I complete the Beighton scale. I look at their knees and have them reach down to touch the floor. I then do specific joint measurements to assess the amount of hyperextensibility. Figure 5 shows range of motion at the elbow.

Figure 5. Assessing elbow range of motion.

I will also measure any joints where they are having pain. Interestingly, you may not see hypermobility until later in your evaluation. You may also need to assess the ligaments if you see a lot of hypermobility. I will stress those ligaments to see how lax they are. On a regular orthopedic-injured patient, when I stress a ligament, I stress one side versus the other. However, you cannot do this with these children as they are typically hypermobile on both sides. Ligament assessment is a kinesthetic skill that you develop over time after feeling normal joints. I would encourage you to feel the normal MP and IP joints of hands on all of your patients or family members and practice this skill. Then, when you come across a laxed joint or a hypermobile joint, you will know the difference.

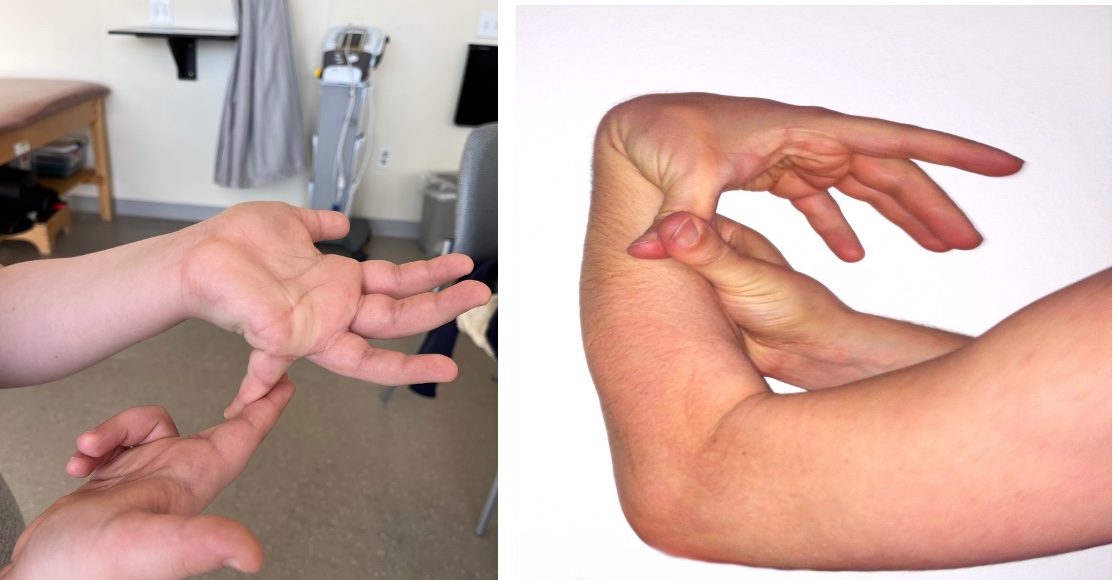

Figure 6 shows an example of stressing the volar plate of the IP joint of the thumb.

Figure 6. Stressing the thumb joint.

- Strength:

- MMT

- Grip/pinch

- Functional

- Watch for joint positioning and substitutions.

I then look at strength as the laxity of joints usually results in weakness. If you do not have stability in a joint, you cannot use your muscles as efficiently as needed because part of that muscle power goes towards stabilizing the joint. I do a normal manual muscle test on both sides, assess grip and pinch strength, and then look at functional strengthening. Figure 7 show some examples of the strength tests.

Figure 7. Strength tests.

What are they having trouble doing? If they report having difficulty opening a jar, I have them try that. If they have difficulty fastening fasteners, I either use what is on their clothes or have a board with different fasteners. Snaps and buttons are especially hard for these children as their fingers are hyperextended at the IP joints. I look at functional tasks to see what their joints are doing and for any substitutions.

- ADL evaluation (age-appropriate)

- Observe the task

- Sports specific questions

- Pain evaluation

- Diagram

- Questionnaire

- Analog scale

Sometimes, you do not see hypermobility until they are doing an activity. I like to go through an ADL inventory and ask what they can do. I will then observe and videotape the task. Part of the reason I videotape is that I want some visual feedback on how they are using their joints. This also allows me to show change over time. Say they will button and show some hyperextension at the IP joint by 60 degrees. I want to have a snapshot of how we can work on changing that. I may also ask them sports-specific questions. If they have an injury or pain, I want to know the details of that sport and how it impacts their ability to play.

I also complete a pain evaluation, whether it is via an interview with the parents, a diagram, a questionnaire, or an analog scale. I want to use some type of a validated pain scale if possible.

- Identify trigger activities.

- Watch for apprehension

- Infants’ grasp development/fine motor skills

- Mobility

It is also vital to identify trigger activities. Children may have difficulty verbalizing these, but older kids can identify triggering events. Typically, they have discontinued doing these activities if it is a trigger for pain. I look for apprehension during tasks like putting their weight through their upper extremities. When assessing infants, I get information on their mobility, like rolling and crawling, and look at their grasp development and fine motor skills. They do not use a regular grasp pattern and have difficulty grasping certain toys based on the hypermobility of the joints. I also look at their mobility, especially in prone with their upper extremities, while PT works on core and hip and lower extremity strengthening.

ED-Effects on Function: Infants/Toddlers

- “Floppy” baby (not low tone)

- Slow motor development

- Especially gross motor initially

- Fussy/fatigued

- Altered grasp patterns

- Clasped thumbs

- Difficulty UE weight-bearing in prone

Many of these infants are brought into the clinic as "floppy babies" or appear to be low tone, but these children are not low tone. Instead, they are hypermobile and weak. Therefore, they have slower motor development, especially gross motor. These kids may not be able to stand up, walk, or grasp a toy. These infants are fussy and fatigue quickly.

It is essential to know their history before treating as you may only get about 20 to 30-minutes. They have altered grasp patterns instead of normal grasp development, especially at the digital MP joints, the wrist joint, and the thumb MP joint. This impaired grasp will also affect their hand use down the road.

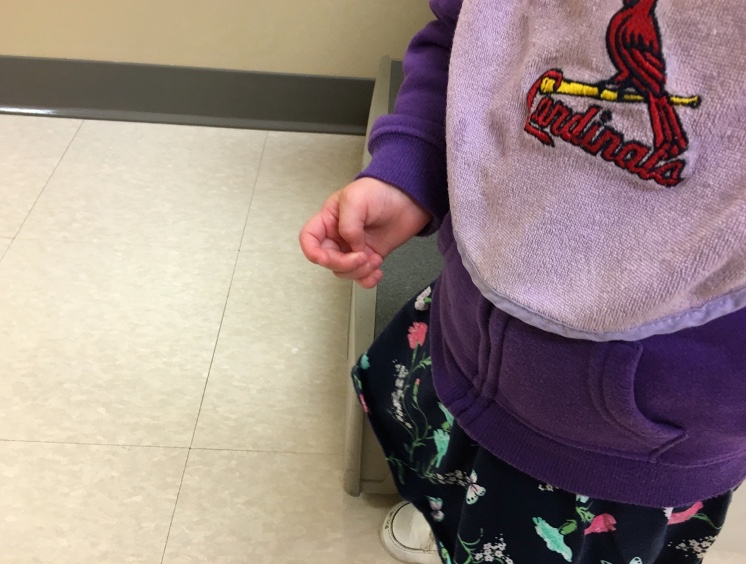

Clasped Thumb

Many kids have what looks like a clasped thumb. They tend to keep resting in the palm because of the stresses on the MP joint. They also have difficulty with weight-bearing on their upper extremities in prone with either their elbows hyperextended or they drop down quickly from this position. They drop down from prone on both sides, not just one side. Their wrists also show some hyperextension and hyperdeviation. Babies also learn to avoid certain activities if they are too complicated or cause pain. And these infants typically start to avoid activities such as prone positioning early on and become fussy and cry if you make them do these activities. These individuals learn how to avoid a lot of activities throughout their life, and by the time they get older, they look like they are disinterested. However, this avoidance is self-preservation and affects all of their motor and sensory development.

Figure 8. Thumb resting in a clasped position.

Again, this is a protected position and not a contracture. They can extend it.

Many kids will be classified with sensory processing disorders. Some of them have components of this due to a lack of joint proprioception and weight-bearing. A person with sensory issues and a person who is an avoider can look similar.

ED-Effects on Function: School Age

- Handwriting:

- Pain

- Altered grasp

- Fatigue

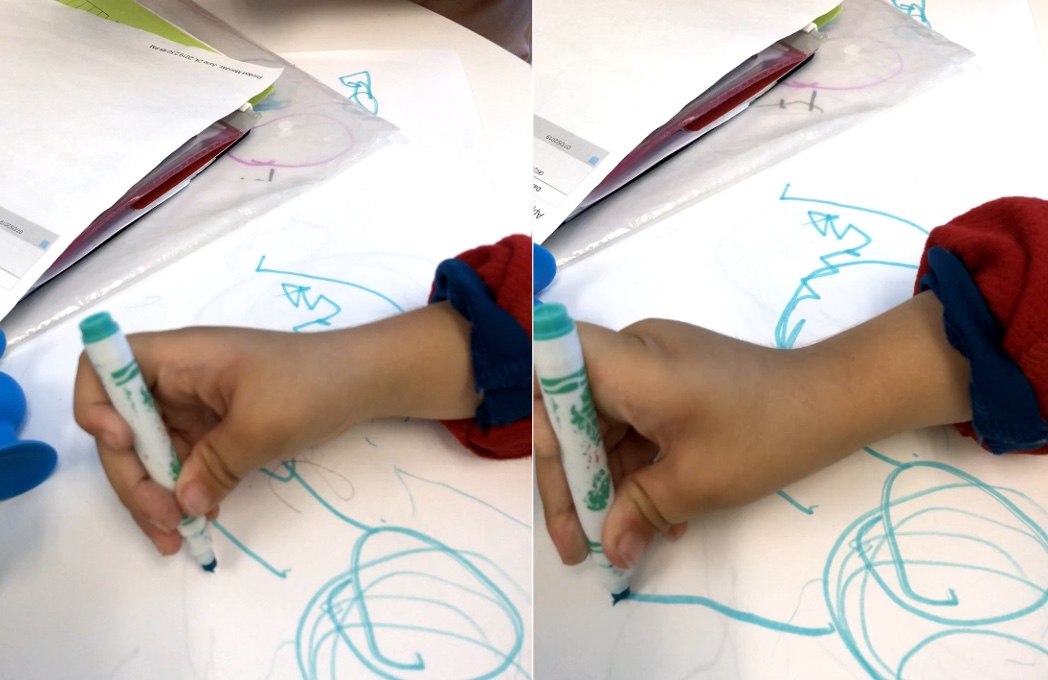

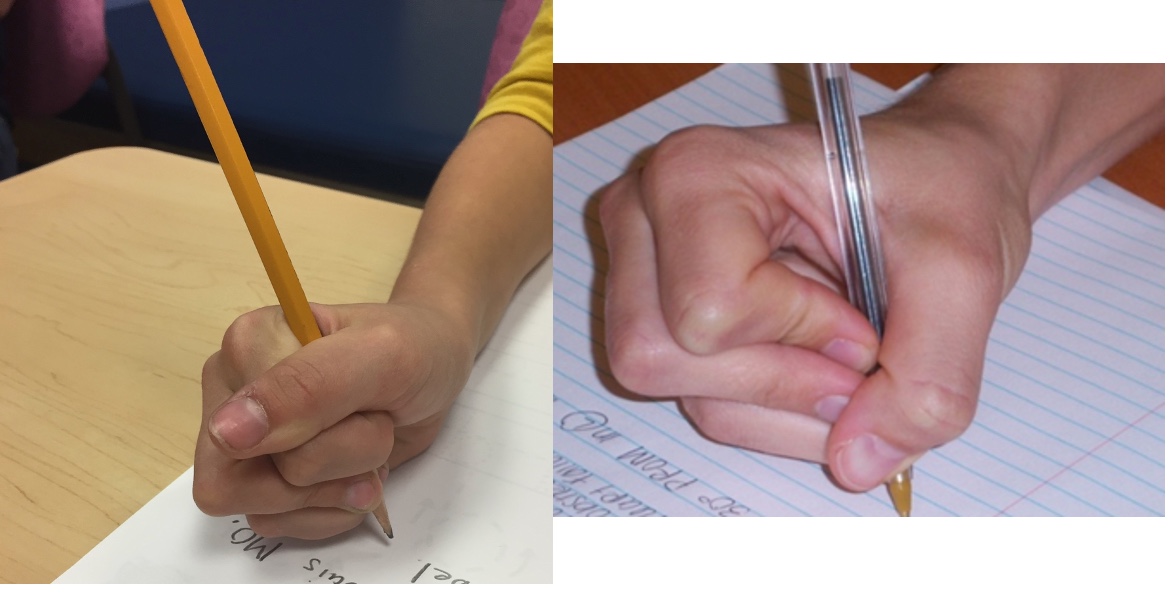

The primary reason that I see these kids is for handwriting. An example is known in Figure 9.

Figure 9. A girl writing with hypermobile joints.

Often, they will have pain with prolonged handwriting, but they often cannot tell you how long that is. So, I have them write until they feel their pain, and then they can also show me where it hurts.

They also develop altered grasps with pencils and pens, and there are a couple of different philosophies on why this is so. They may alter the grasp to gain stability. Our joints typically give us stability as we hold a pencil, but for these kids, they need to change to a more secure position. As they try to gain stability, they squeeze the pen or pencil very hard and incur joint hyperextension. They have an altered grasp because of proprioceptive impairment in those joints. When holding the pencil, they have to squeeze harder to get more proprioceptive input if they cannot feel.

They may also be sent to you for handwriting due to fatigue. The teacher starts to tell the parents, "You need to assess their hands because something is going on here."

- Difficulty with ADLs

- Pain with fatigue: general activities

- Difficulty with sports

- Can also be very good at sports.

- Difficulty with opening

- Apprehension with activities

These children also have difficulty with ADLs, fasteners, and doing their hair. They may have a hard time opening containers. You can go through their day and find out where they have difficulty. As I mentioned earlier, these kids also have a lot of pain and fatigue with general activities and may appear unmotivated. They do not want pain or fatigue, so it is easier to sit down and watch television, read a book, or play a video game. They may also have difficulty with sports due to the pain and fatigue; however, some children with hypermobility are very good at sports requiring many joint motions. This is especially true of gymnasts and swimmers, especially the backstroke, which involves a lot of shoulder mobility. I also see hypermobility in dancers or cheerleaders who are very good at what they do. These kids may only come in when they get hurt. I often ask parents to videotape maybe 10 minutes of their sport to analyze what they are doing and see how I can help them.

Pencil Grasp

Here are some examples of pencil grasp difficulties. You can see the extreme hyperextension at the thumb. They also have a modified grasp instead of a dynamic tripod as they are trying to gain some stability on the marker when they color (Figure 10).

Figure 10. A child holding a marker showing hyperextension.

On the left, they gain stability by tightly squeezing the marker in the first webspace. You can also see how tight all of the fingers are. Figure 11 shows another child using a pencil and pen.

Figure 11. A child demonstrating a poor grasp of a pencil and pen.

She is squeezing so tight in both images. Instead of squeezing the fingers all the way around, this individual is hyperextending at the IP joints. She is also using a quadruped grip to stabilize the writing utensil, possibly trying to get some proprioceptive input.

ED-Adolescents/Young Adults

- Pain with the use of body parts; especially hands

- Limitations in function: sports; ADLs; musical instrument; hobby or job-related.

- Decreased strength: specific and general

- Increased fatigue

- Apprehension/lack of participation

If an adolescent or young adult has a problem with hypermobility, they typically know about it by now. Due to increased writing, they usually come to see me when having pain with a specific body part, especially their hands. For example, some kids start taking art classes in high school when they first notice a problem. They may also have limitations in function, sports, or start to play musical instruments, especially with lots of finger motion. They may also start a new hobby or job. They may have decreased strength and fatigue with regular daily activities.

Treatment Strategies for OT: General

- Education: adaptations to activities

- Body mechanics

- Joint protection

- Pain management with daily activities

- Use of external support for joints

- Beware of the use of tape on the skin

- External support can lead to further weakness

Before getting into each specific age group, I want to talk about general treatment strategies. I provide a lot of education, show them via pictures and video what their postures look like, and help them adapt. Muscles typically hurt because they are overfiring, and as a result, they fatigue quicker than ordinary people. I instruct them on body mechanics and joint protection techniques that are generic to everybody. We also talk about pain management with daily activities. Lastly, I go over external support for joints.

Here are a couple of caveats. Due to the collagen component, if you are putting tape on their skin (dynamic stabilization tape, Kinesio tape, or Leukotape), you need to beware their skin is more fragile. I always do a test strip on these older kids to ensure we do not have skin breakdown or skin problems. And, if I give them support to wear on their wrist when they are doing a particular activity, then their wrist flexors and extensors are not going to work as hard and become weaker, so this is important to keep in mind.

- Strengthening for supporting structures to allow improved abilities

- Both specific musculature strengthening and functional activity strengthening

If the ligaments and joint capsule are not going to provide stability, the muscles that cross over that joint can provide some stability to decrease the stress and pain; thus, one of our primary treatment strategies is strengthening muscles. We work on both specific and functional musculature strengthening using activity analysis. You need to know what muscles you need to strengthen and then make sure that the task addresses those muscles.

- Fabrication of orthotics or external support to the joints

- ADL modifications with the use of assists

- Activity modification

Fabrication of orthosis or external support is sometimes warranted if tape or a softer support system will not work. We can make ADL and activity modifications if they want to continue to do certain activities. You do want these children to stop doing activities and become more sedentary because it leads to more problems and pain. My goal for everybody is to stay active and involved in activities that give them satisfaction and happiness.

Age-specific Treatment: Infant

Overview

- Grasp development

- Fine motor development activities to promote general strength

At this age, I look at grasp development and try to correct it. Figure 12 shows a friend's baby that has weak thumbs.

Figure 12. Baby with weak thumbs.

Her thumb would clasp when she would grab something because it would hyperextend. I used a support for specific activities while working on grasp development and fine motor activities to promote general strength. An infant's fine motor development primarily focuses on grasp and release, weight-bearing, and reaching. The best treatment for an infant is via short spurts all during the day. I empower these parents to understand what is going on and how to then address these issues.

- External joint support if needed

- Education for parents on avoidance of substitution

- Proprioceptive input to joints

I like to use external joint support, such as the above thumb splint, but only intermittently and during specific grasping activities to give joint stability. We do this so that the child does not avoid activities or develop abnormal grasp patterns affecting sensory input or later in-hand manipulation. I talk to the parents a lot about preventing substitution. For example, if I see elbow hyperextension, I show them how to reposition their child that posture. Or, if I see the thumb going into the palm or hyperextending at the MP joint, I show the parents simple repositioning. I try to engage all caretakers to avoid substitutions. I also like to do some proprioceptive input and joint compressions to help facilitate the receptors and allow the child to feel normal input.

Specific Activities

- Grasp various sized objects for open and close of hands

- Swinging to grasp/push/pull

- Pulling toys apart/putting them together

- Use of toy tools

I will have the infant work on grasping various sizes of objects to work on opening and closing their hand. When they get a little bit older, I like to work on swinging so that they have to hold onto the swing handles, so they are working on elbow flexion-extension and grasp simultaneously. They can also pull apart and put together toys for grasp and release and wrist motion, and stability.

Treatment Activities

- Weight-bearing on both UEs support as needed;

- Over bolster; on ball; while sitting and leaning

- Yoga poses

As they get a little bit older, I do a lot of weight-bearing on both the upper extremities, as seen in Figure 13.

Figure 13. Weight-bearing through the upper extremities.

Sometimes, I put them over a bolster or a ball, either while sitting or leaning forward. My favorite is doing yoga poses with the little kids because they have so much fun. If I see them using abnormal postures, I reposition and recorrect. If I cannot get them to reposition or recorrect, then I may use an external support for the short term until we can get them past that phase, as it is hard to correct a toddler verbally. I can tell them what I want them to do, but they will do whatever she wants. Here are some more examples of strengthening in Figure 14.

Figure 14. Example of things to use for strengthening.

Orthotics

- Elbow stabilization

- Immobilizer

- K Tape

- Wrist stabilization

- Small prefab

- K tape

- Thumb stabilization

- Benik; McKey; neoprene fabricated

You can use an immobilizer to stabilize the elbow and prevent hyperextension, especially during prone push-ups or crawling. However, some immobilizers do not fit tight enough to avoid hyperextension. You may be able to put a stay behind the elbow to keep it from going into hyperextension. I have also used K tape designed for infants to keep them in some flexion to provide input to prevent hyperextension. For wrist stabilization, I use a small prefab splint at times and move it into the extended position to allow them to weight-bear or use K tape along the flexor side to avoid hyperextension or deviation of the wrist. For thumb stabilization, especially the MP joint, I either use a Benik, a McKie, or a neoprene-fabricated orthosis. Figure 15 shows a simple neoprene wrist wrap that provides gentle support and prevents deviation.

Figure 15. Neoprene wrist wrap.

With this, they can still weight-bear on their hand but cannot deviate or go into hyperextension. Sometimes, I use something to stabilize the thumb MP joint so they can still weight-bear but does not affect too much of the wrist. This can be seen in Figure 16.

Figure 16. Neoprene thumb support.

McKie thumb MP splint, shown in Figure 17, is an excellent alternative.

Figure 17. McKie thumb MP splint. www.Mckiesplints.com

Considerations

- Laxity in joints naturally

- Fatigue quickly

- These can be fussy babies.

- Parents must be consistent with follow-through at home.

Some considerations for infants. They have natural laxity in joints, fatigue quickly, and can be fussy babies. It is imperative that parents are consistent and follow through at home.

Age-specific Treatment: School-Aged

Overview

- Hand and UE strengthening

- Assessment of body mechanics and watch for substitution

- Pencil grasp/handwriting assessment with treatment as needed

- Activity and ADL modifications

- Orthosis as indicated

I typically start with hand and upper extremity strengthening for school-aged kids with play-type exercises, crafts, and games. I look at their body mechanics and watch for substitution. I also focus a lot on pencil grasp and handwriting. Then, I incorporate activity, ADL modifications, and orthosis as indicated.

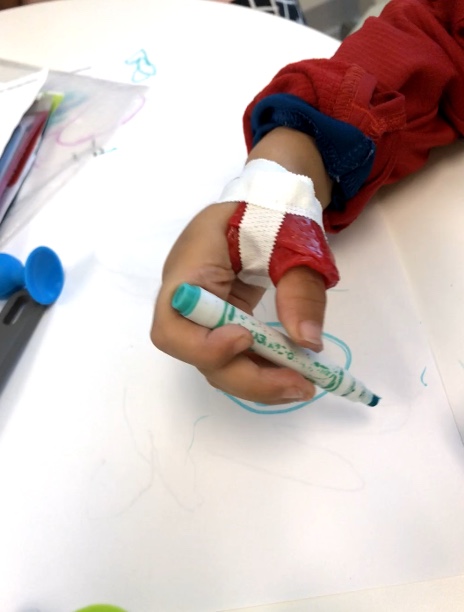

Handwriting

- Altered grasp for writing, etc.

- Strengthening

- Pencil grips

- Use of “toolbox”

- Oval 8 or other orthoses

Handwriting is a primary area. I have them take pictures to see what they are doing. Goals include strengthening the muscles to better support the joints during this activity. At times, I use pencil grips. I tell kids that I am not trying to change how they are holding their pencils as they get freaked out if you tell them that. Instead, I tell them I am giving them a toolbox (or pencil box). "When your hand starts hurting, you will use something different in your toolbox until it stops hurting. And then, you can go back to your other way of holding if you want." I have found that they get more comfortable with the alternate types of grasp over time, and they do not go back to their old ways of holding their writing utensils. The toolbox may also include a splint or orthosis (Figure 18).

Figure 18. Example of an orthosis for writing.

An orthosis helps the joints stay in an unstressed position. This child's IP joint went into the correct position by stabilizing his MP joint.

Pencil Grasp

Here are some examples of pencil grasp in Figure 19.

Figure 19. Examples of pencil grasp.

My favorite grasp is on the left. When I worked with adults with rheumatoid arthritis, I used this pencil grasp a lot as they had a lot of thumb pain. Holding the pencil like this provides stability without any force. This is a great way to correct the DIP hyperextension that you see in many kids. I also use rubberized pencil grips. I have the parents order it online. It is not slippery, and you do not have to squeeze it. Both of these are great ways to get rid of hyperextension of the IP joints.

Figure 20 shows some other alternatives for pens if someone is hyperextending at either the thumb or DIP of the finger.

Figure 20. Alternatives for pen use.

Exercises

- Hand and UE strength

- Games; building toys; clay; crafts; exercise

- Use of weight-bearing

- Joint compressions

Hand and upper extremity strengthening can be achieved using games, building toys, clay, crafts, and exercise. Figures 21-23 show examples of this.

Figure 21. Craft activity with beads.

Figure 22. A game and blocks.

Figure 23. Toy and ball to work on grasp.

I am sure you all have tools that you like to use. It is essential to watch and educate them to avoid alternate positions, hyperextension, or abnormal joint positions. I also use a lot of weight-bearing, including yoga poses with kids. During these activities, you need to use observation and cues. However, there is a difference between verbal cueing and nagging. You can give a nice verbal or physical cue without ever saying anything. It is not scolding or telling them they are doing something wrong, but rather it is a way to remind them. I like to use joint compressions, primarily during weight-bearing activities.

ADL/Activity Modifications

- Clothing: Fasteners, hoops to pull

- Sports: Grasp of handles

- Play

You can make modifications to their clothing. For example, you can put little hoops inside of their pants if it hurts their hands due to hyperextension to pull up their pants. We can also make modifications to handles like for sports equipment. As an example, I have enlarged a hockey stick handle or have put something inside a glove to help them hold it a little better.

Considerations

- Don’t want to “be different” (regarding use of adaptations)

- Self-conscious

- Adventurous

- Creative

- Let them control

Children do not want to be different, especially using adaptations. So, the less external things that people can see, the better. They do not want to wear a splint, use tape, or use a pencil grasp. If I can educate them and get them better without that, they will be happier. They are very self-conscious, but they are also adventurous and will often try anything you want. I like to let them have control, hence the toolbox.

Age-specific: Adolescents/Young Adults

Overview

- Injury specific treatment

- Incorporate your education into treatment.

- Joint specific strengthening: Avoid high weights

- Activity modifications

- Pain Management

Like the school-age kids, these older kids come in for an injury-specific reason. Once I have seen what they are doing, we start to educate them on how they can use their joints to avoid overstressing them. I also do joint-specific strengthening. You want to avoid high weights because this can aggravate the joint pain more. Lastly, I do activity modification and pain management.

Injury Specific

- General orthopedic treatment

- Motion

- Strength

- Modified activity

- Orthosis as indicated

You work on the motion that they need. Sometimes, these kids develop muscle tightness as they are overworked, even though they have joint laxity. We may need to work on stretching the muscles out and modify their activities and orthosis as indicated.

Strengthening

- Isometrics

- Co-contractions

- Perform in pain-free range

- With joints stabilized as indicated

I try to use isometrics for strengthening. Co-contractions of the joints are a great way to strengthen without irritating pain in the joint. All of your exercises should be done in a pain-free range and with the joint stabilized as indicated.

Activity Modification

- Stabilization of body parts

- Prevent muscle fatigue

- External supports:

- Tape

- Orthosis

- Neoprene

With activity modification, I want to look at the stabilization of the body parts. If their muscles and ligaments cannot stabilize a joint, we may need external stabilization such as tape, an orthosis, or neoprene wrap. Sometimes, I use a rigid orthosis at times, but these are often lost.

Taping

Here are some examples of taping in Figure 24.

Figure 24. Thumb taping example.

Orthosis

Here are two orthoses examples in Figure 25.

Figure 25. Orthoses examples.

Pain Management

- Distraction

- Education

- Guided imagery

Pain management is also a big issue with these older kids. I can teach them some pain management techniques, such as distraction, education, and guided imagery. I work closely with pain management providers if available.

Considerations

- Don’t want to be different

- Can take responsibility for their participation

- This will guide their choices

- Career

- Avocational

- These kids can appear “unmotivated” or inactive

Adolescents also do not want to be different, but now they can start to take responsibility for their participation in their treatment. This starts to guide treatment. They have realized by now that this is a lifelong condition and may start to get very frustrated. They do not want to have pain all of the time or be limited with activities. This starts to guide their choices regarding careers and avocational activities. They can also look unmotivated or inactive because they are fearful.

Orthotics: Upper Extremity

- Need least intrusive amount of support

- Provide support with specific activity

- Lightweight due to fatigue factor

- Ease of don/doff

- Avoid frequent or full-time use as possible

I want the orthosis to provide the least intrusive amount of support or only to be used with specific activity; that is my ideal. I want it to be lightweight, or it will increase fatigue of the muscles. It needs to be applied and removed easily.

Joint Support

- K Tape

- Neoprene support

- Flexible casting tape: Orficast

- 1/16” thermoplastic

I never want them to use a device full-time unless the client wants to, as it makes them feel better. I often use K tape and neoprene support. Figure 26 shows Orficast material.

Figure 26. Example of an Orficast splint.

I like Orficast as it is flexible, lightweight, comfortable, and it can get wet. This splint was used for an individual who played volleyball and kept subluxing her MP joint. She was able to play volleyball with this orthosis. So it worked great for her.

Conclusion

- These can be challenging but fun patients.

- Must look at the whole person

- Goals:

- Activity specific

- Independence with activity

In conclusion, these can be challenging but fun patients. I love figuring out what is going on as part of doing a treatment. I want to know why they are having pain and difficulties. I can then cater my treatment to those specific difficulties.

References

Adib, N., Davies, K., Grahame, R., Woo, P., & Murray, K. J. (2005). Joint hypermobility syndrome in childhood. A not so benign multisystem disorder? Rheumatology (Oxford, England), 44(6), 744–750. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keh557

Bale, P., Easton, V., Bacon, H., Jerman, E., Watts, L., Barton, G., . . . MacGregor, A. J. (2019). The effectiveness of a multidisciplinary intervention strategy for the treatment of symptomatic joint hypermobility in childhood: a randomised, single centre parallel group trial (the bendy study). Pediatric Rheumatology Online Journal, 17(1), 2. doi:https://dx.doi.org/10.1186/

Engelbert, R. H. H., van Bergen, M., Henneken, T., Helders, P. J. M., & Takken, T. (2006). Exercise tolerance in children and adolescents with musculoskeletal pain in joint hypermobility and joint hypomobility syndrome. Pediatrics, 118(3), e690-e696.

Fatoye, F., Palmer, S., Macmillan, F., Rowe, P., & van der Linden, M. (2012). Pain intensity and quality of life perception in children with hypermobility syndrome. Rheumatology international, 32(5),1277–1284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-010-1729-2

Guidelines for management of joint hypermobility syndrome ... (n.d.). Retrieved December 21, 2021, from https://www.sparn.scot.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Guidelines-for-Management-of-Joint-Hypermobility-Syndrome-v1.1-June-2013.pdf

Malek, S., Reinhold, E.J. & Pearce, G.S. The Beighton Score as a measure of generalised joint hypermobility. Rheumatol Int 41, 1707–1716 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-021-04832-4

Morlino, S., Dordoni, C., Sperduti, I., Venturini, M., Celletti, C., Camerota, F., . . . Castori, M. (2017). Refining patterns of joint hypermobility, habitus, and orthopedic traits in joint hypermobility syndrome and ehlers-danlos syndrome, hypermobility type. American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part A, 173(4), 914-929.

Muldowney, K. (2015). Living life to the fullest with Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome: A guide for a person living with Eds to achieve a better quality of life. Outskirts Press.

Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process—Fourth Edition. (2020). Am J Occup Ther, 74(Supplement_2):7412410010. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2020.74S2001

Revivo, G., Amstutz, D. K., Gagnon, C. M., & McCormick, Z. L. (2019). Interdisciplinary pain management improves pain and function in pediatric patients with chronic pain associated with joint hypermobility syndrome. PM & R : The Journal of Injury, Function, and Rehabilitation, 11(2), 150-157. doi:https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pmrj.2018.06.018

Rosenblum, S., & Gafni-Lachter, L. (2015). Handwriting proficiency screening questionnaire for children (HPSQ–C): Development, reliability, and validity. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 69(3). https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2015.014761

Scheper MC, Nicholson LL, Adams RD, Tofts L, Pacey V. (2017). The natural history of children with joint hypermobility syndrome and Ehlers-Danlos hypermobility type: a longitudinal cohort study. Rheumatology (Oxford), 56(12):2073–83.

Sinibaldi, L., Ursini, G., & Castori, M. (2015). Psychopathological manifestations of joint hypermobility and joint hypermobility syndrome/ Ehlers-danlos syndrome, hypermobility type: The link between connective tissue and psychological distress revised. American Journal of Medical Genetics.Part C, Seminars in Medical Genetics, 169(1), 97-106.

Smith, T. O., Bacon, H., Jerman, E., Easton, V., Armon, K., Poland, F., & Macgregor, A. J. (2014). Physiotherapy and occupational therapy interventions for people with benign joint hypermobility syndrome: A systematic review of clinical trials. Disability and Rehabilitation, 36(10), 797-803.

Yew, K. S., Kamps-Schmitt, K. A., & Borge, R. (2021). Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome and Hypermobility Spectrum Disorders. American family physician, 103(8), 481–492.

Citation

Calhoun, V. (2022). Joint hypermobility syndromes: Assessment and intervention. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5499. Available at https://OccupationalTherapy.com