Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Stroke Rehab: Evaluation And Treatment, presented by Lacy Nauck, OTA, CEAS I, TBIS, Sex and Intimacy Specialist, M.A. International Psychology with trauma and group conflict specialty.

*Please also use the handout with this text course to supplement the material.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to recognize common symptoms associated with stroke based on the area of the brain affected.

- After this course, participants will be able to identify at least three common screening tools to evaluate deficits after a stroke.

- After this course, participants will be able to list three best-practice interventions for stroke rehab.

Introduction

Thank you so much for that introduction, and thank you, everyone, for joining me today. Stroke rehab is one of my passions, so I’m excited to share some best practices with all of you.

Stroke

According to the CDC, every 40 seconds, someone in the United States has a stroke. Every 3 minutes and 11 seconds, someone dies of a stroke. In the U.S., over 795,000 people experience a stroke each year. Stroke is one of the leading causes of disability, which highlights how vitally important it is for occupational therapy practitioners to have a solid grounding in this condition—understanding both the presentation and the range of deficits that can occur. With that foundation, we can deliver the most effective treatment possible to help this population regain function and return to living as independently as possible.

Brain

How does injury affect the brain? I'm sure we all have heard of right-versus-left-sided strokes. And even if you don't get the documentation saying which side of the brain was affected by the stroke, I'm sure you can guess when you see the client which side is affected and which side isn't.

Hemispheres

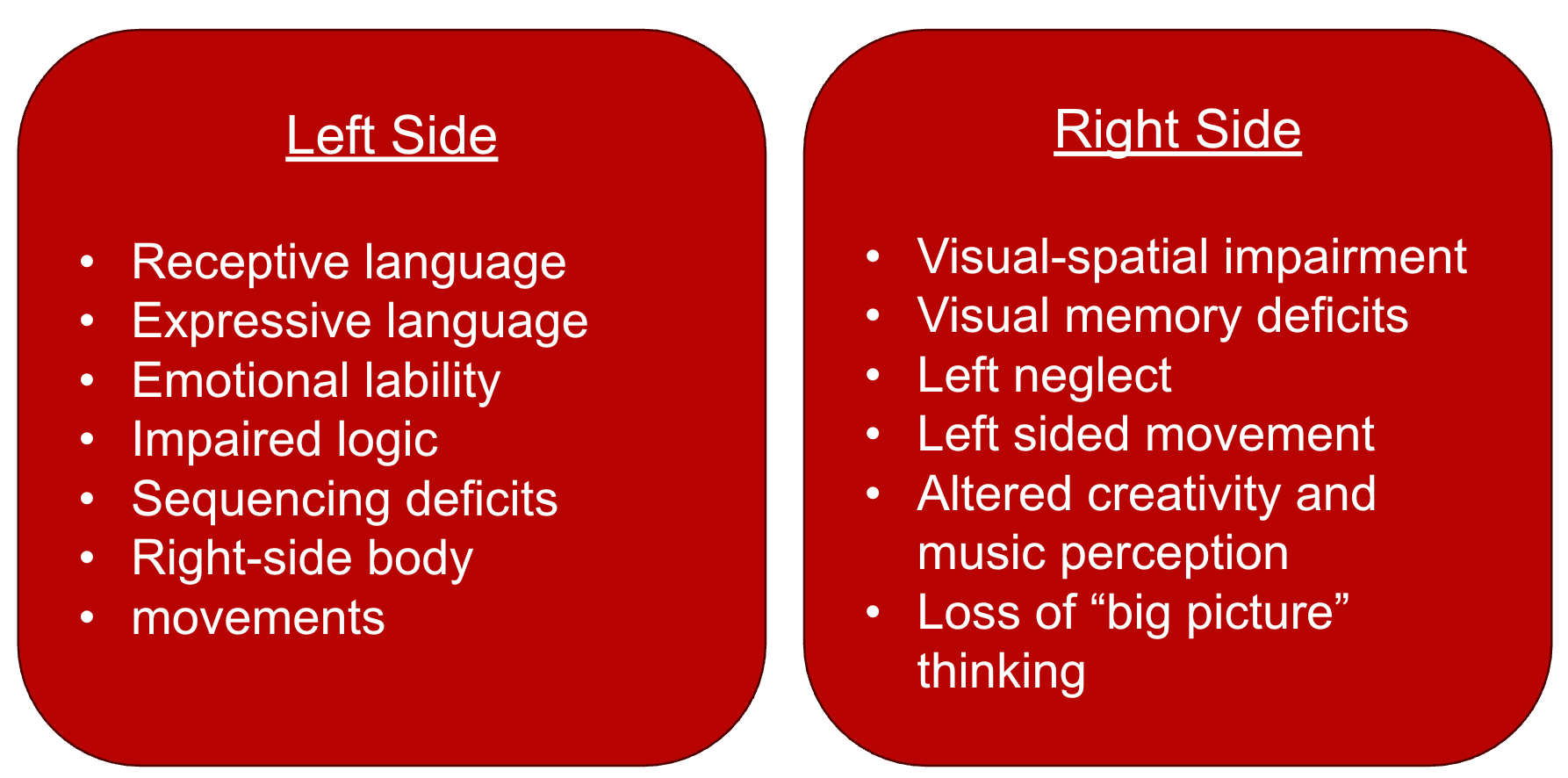

I'm going to go into some of the general deficits that you see with each of the sides of the hemispheres (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A comparison of the two hemispheres.

On the left side of the brain, you typically see receptive and expressive language deficits, emotional lability, impairments in logic and sequencing, and, of course, right-sided body movement impairments. On the right side, common deficits include visual-spatial impairment, visual memory deficits, left neglect, left-sided motor impairment, altered creativity and music perception, and a loss of big-picture thinking.

Now, I want to make a specific point here about left neglect, which is listed under right-sided brain involvement. If a person has had a left-sided stroke and appears to be showing neglect on the left side, that’s typically not true neglect but rather a visual field deficit. Understanding that distinction can help you narrow down the actual deficit and inform how you approach treatment. I’ll be going into more detail on identifying and addressing these differences later in the course.

Lobes

An overview of the brain's lobes can be seen below.

Frontal Lobe | Temporal Lobe | Parietal Lobe | Occipital Lobe |

Can change person’s personality depending on severity. | Trouble recognizing faces, visual agnosia | Sensory deficits (pain, five senses) |

|

Difficulty controlling emotions (impulsive) | Decreased hearing | Difficulty with sizes, shapes, colors | |

Communication deficits | Attention deficits | Attention deficits | Visual attention |

Impaired recall | Impaired memory | Impaired memory | |

Trouble learning from mistakes | Wernicke’s aphasia |

The frontal lobe is the major center of executive functioning. It plays a big role in personality and emotional regulation. When there's damage to this area, people may become more prone to anger or impulsivity. You might hear family members say that the person seems like a different version of themselves. They may have impaired logic, difficulty with communication, and trouble learning from mistakes.

Moving to the temporal lobe, you might see challenges like difficulty recognizing faces, visual agnosia, decreased hearing, attention deficits, impaired memory, and Wernicke's aphasia. I want to take a moment here to highlight that, underneath all of these lobes, you often see some form of attention or memory deficit. This tends to be a common issue across many types of stroke, so it’s essential to factor that into your evaluation and treatment. These cognitive changes can significantly influence whether or not a person can complete certain tasks safely and independently.

Returning to the lobes—your parietal lobe functions as the brain’s sensory hub. When it's affected, you may observe altered pain perception. For example, a person might feel intense pain when they shouldn’t or, conversely, not when they should. There can also be difficulty perceiving sizes, shapes, and colors, as well as more attention deficits and memory impairments.

The occipital lobe is your vision center. Deficits in this area can result in symptoms like double vision, difficulty with saccades (shifting gaze), strabismus, and visual field losses. Even if a stroke doesn’t directly affect the occipital lobe, visual issues can still arise from other types of strokes. According to the American Stroke Association, about 65% of stroke survivors experience some visual deficit. That’s a significant percentage, underscoring how critical it is for us as therapists to assess vision thoroughly. These deficits can range from minor visual field cuts to more complex ocular motor problems, which are crucial to identify and address.

I once had a patient who had already been through acute care and inpatient rehab and had seen multiple doctors. When she came to me, I started assessing her vision and discovered a visual field deficit that had gone unnoticed. She was shocked—she didn’t know she had that deficit. But once it was identified, other issues started to make more sense, like she kept bumping into objects on that side or was struggling with balance. That experience taught me how important it is not to overlook visual screening. Even if other professionals have evaluated the patient, those deficits can still go undetected, and you might be the one to catch them and make a real difference. So please, don’t ignore vision—it matters.

Other Specific Areas

Other specific areas to consider include the pons, the origin of the 12 cranial nerves. When this area is affected, you may observe difficulty with moving facial features, tear production, and significant balance issues. Involvement of the pons and cerebellum together can lead to even more pronounced balance difficulties and challenges with coordination, fine motor control, trajectory of movement, equilibrium, proprioception, and eye-hand coordination.

The hippocampus is considered the memory house of the brain. It plays a critical role in supporting memory, learning, spatial navigation, and perception within space. Damage to the hippocampus can impair the ability to move short-term memories into long-term storage, making it difficult for individuals to retrieve information or recall events. This kind of damage is also believed to contribute to conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease.

Now that I’ve covered those specific brain regions, I’m going to move into some of the general deficits commonly seen following a stroke.

Perceptual and Interpretation

Body Schema

When discussing perceptual interpretation, I’m sure many of us have encountered unilateral neglect—where the person is not integrating stimuli from one side of the body or the environment. This often happens when one side of the body is severely affected post-stroke. For instance, when the affected side is flaccid, numb, or lacks sensation, the individual tends to ignore it. Over time, this can become even more pronounced, with increasing neglect, decreased attention, and reduced awareness of that side.

Another important deficit is anosognosia, which is the lack of awareness or outright denial of paralysis in a limb. Then there’s right-left discrimination difficulty, where individuals cannot identify their right and left sides or follow commands that involve these directions. I see this frequently in my patients, and it's especially critical when considering tasks like returning to driving. For example, if someone tells themselves to move their right foot to press the gas pedal, their left foot might move instead, or both feet might move at once. This creates a dangerous situation, such as simultaneously hitting the gas and brake.

Because I do a lot of rehab related to returning to driving, I focus on correcting this area. One particularly effective approach is graded motor imagery, which I’ll discuss later in the course. But it’s essential to address and improve right-left discrimination in rehab.

Somatognosia is another perceptual deficit, referring to a lack of awareness of body structure and the relationship between body parts. A person with this deficit might not understand how to move a specific part of their body, like their hand, because they can’t conceptualize what other parts need to move to make that happen. If you ask them to lift their shoulder or elbow, they may struggle to comprehend how those joints are connected to the action. Understanding these perceptual issues is vital for designing effective and meaningful treatment interventions.

Agnosia

Agnosia can take several forms, each affecting a different sensory pathway. Visual object agnosia is the inability to recognize objects purely through visual input. Someone with this may be looking directly at an object like a toothbrush but won’t be able to identify what it is just by sight.

Auditory agnosia is the inability to distinguish between different non-speech sounds. For example, someone may confuse the sound of an alarm with a doorbell. This can lead to safety concerns, as the person may not react appropriately to environmental cues.

Tactile agnosia is a sensory processing disorder that impacts the ability to perform stereognosis. For anyone who needs a quick refresher, stereognosis is the ability to identify objects through touch alone, without using vision. It's that familiar situation where you reach into your bag and can find your keys or wallet just by feeling. A person with tactile agnosia wouldn’t be able to perform this task, as they lack the ability to recognize objects by touch.

Spatial Relation Disorders

Then, you have spatial relation disorders, which can significantly impact a person’s ability to function safely and independently. One common type is figure-ground discrimination, where the individual cannot distinguish a figure from its background. This becomes a challenge when locating items in a cluttered space—for example, picking out a white towel from a white bedsheet or finding a button on a patterned shirt.

Form discrimination is another aspect in which it is difficult to recognize objects if they are in different orientations or look similar in shape. For instance, someone might confuse a pen with a knife or a toothbrush because of their similar forms, and they may not recognize the difference in how each object is used.

Spatial relationships refer to the ability to perceive how objects relate to each other or how the body relates to those objects. When this is impaired, tasks like crossing midline or getting dressed can become difficult. Someone might struggle with knowing where their sleeve is or how to bring their arm across the body to put it through.

Vertical orientation involves sustaining an upright posture and recognizing what is upright in the environment. Deficits here can lead to leaning or postural instability. Finally, depth and distance perception can be affected, making it difficult to judge how far away or how deep something is—this has obvious safety implications when navigating stairs or reaching for objects.

Apraxia

Apraxia refers to difficulty with motor planning, and a few types are important to distinguish.

Ideomotor apraxia is the inability to perform tasks on command or imitate gestures, even though the person understands the task and has the physical ability to do it. This is typically associated with a left hemisphere stroke. Individuals may struggle with imitating gestures or pantomiming familiar actions—like pretending to brush their teeth without a toothbrush. You’ll often see errors in sequencing, timing, and the spatial organization of movements.

Ideational apraxia, on the other hand, involves a broader disruption in planning or executing complex sequences of motion. Individuals with this type may attempt to perform a task but do so in an incorrect order—such as putting on socks over shoes. They may also have difficulty with pantomiming, similar to ideomotor apraxia, but the difference lies in the breakdown of the conceptual understanding and sequencing of the task.

I get a lot of questions about these two types because they can sound very similar, but that key distinction is important—ideomotor apraxia is more about imitation and single-step tasks. In contrast, ideational apraxia affects multi-step, purposeful activities and the underlying conceptualization of how things go together.

Buccofacial apraxia involves limitations in the purposeful movement of the lips, cheeks, tongue, larynx, and pharynx. This can present as difficulty performing tasks such as blowing a kiss, sticking out the tongue on command, or making facial expressions, and it can also affect speech and swallowing.

Evaluation Options

These are not comprehensive, but these are the ones that I found to be the most used to be able to test for the various deficits.

Physical Assessment | Coordination | Sensation | Pain | Edema | Vision | Cognition |

Goniometer | 9-Hole Peg | Monofilament | Visual Analogue Scale | Circumference | 9 Cardinal Gazes | MOCA |

Fugl-Meyer Assessment (Upper Extremity) | Box and Block Test | Proprioception | Snellen Visual Chart | Oxford Cognitive Screening | ||

Finger-Nose Test | Stereognosis | Bernell Contrast E Training Chart | Loewenstein Occupational Therapy Cognitive Assessment (LOTCA) | |||

Bell Cancellation Test, Confrontation testing for visual field loss |

For your physical assessment, you'll be using tools like a goniometer to measure range of motion and the Fugl-Meyer Assessment to evaluate motor recovery following a stroke. You might also include manual muscle testing and coordination assessments. Common coordination tests include the Nine-Hole Peg Test, the Box and Blocks Test, and the Finger-to-Nose Test.

When it comes to sensation, assessments may include monofilament testing, proprioception checks, stereognosis, and pain perception evaluation. To measure pain, the Visual Analog Scale is often used. For edema, you can track limb circumference using a tape measure.

I want to add a few notes here based on what we do at our clinic, particularly because we also treat lymphedema. We've been doing a lot of edema tracking and have found that measuring in centimeters and inputting that data into an Excel worksheet works well. This allows us to track the percentage of increase or decrease in swelling over time, which helps monitor patient progress. There are also software programs available that calculate changes in milliliters, so depending on your resources and workflow, you can accurately track edema volume in several ways.

For vision, assessment tools include testing the nine cardinal gazes, using the Snellen Chart, and administering the Bernell Contrast “E” Chart. One of my favorite tools is the Bell Cancellation Test, which identifies neglect and visual field deficits. Confrontation testing is also valuable for detecting visual field loss.

On the cognitive side, you have several strong options, including the MoCA (Montreal Cognitive Assessment), the Oxford Cognitive Screen, and the Lowenstein Occupational Therapy Cognitive Assessment (LOTCA). These can help determine cognitive strengths and areas of concern following a stroke.

Now, let’s get into the treatments and how to tailor them based on your patient.

Brunnström Stages of Recovery

The Brunnstrom stages of recovery provide a helpful framework for understanding how stroke recovery progresses through distinct phases.

Stage one is characterized by flaccid paralysis—there is no voluntary movement at this stage. The limb is essentially limp, with no active muscle contraction.

Stage two marks the emergence of some spasticity. You might see the hand start to curl, a bit of tension in the elbow, and the initiation of synergetic movements. I want to pause here and talk about synergetic movement because I didn’t fully understand it until I immersed myself in neurological rehabilitation.

Synergetic movement refers to the natural coordination of muscle groups to perform a functional task, like walking. In stroke recovery, however, we often see abnormal synergies. A common example is when a patient abducts their arm in an attempt to reach it because it’s easier to open and close their hand that way. If they try to keep the arm flexed, performing that same action becomes much more difficult. These compensatory patterns are considered abnormal synergies, but interestingly, some treatment models suggest that we can use these synergies to build strength. Once the patient gains enough control and strength within these abnormal movement patterns, we can retrain toward more normal movement patterns, isolating specific muscles that are still weak. So, in certain approaches, you can harness those synergies as a treatment strategy, which I’ll touch on more when we get into the different treatment modalities.

Stage three is when voluntary synergetic movement becomes more pronounced, and spasticity increases—especially in areas like the elbow, where it becomes harder to extend the arm.

Stage four introduces more normal movement patterns. Spasticity begins to decrease, and there’s greater control over voluntary movement, though it’s still limited.

Stage five is when patients gain better control of isolated movements. You may start to see more refined coordination, such as opposition of the fingers and controlled pinch patterns.

Finally, stage six reflects a return to near-normal muscle control. At this point, the patient can typically perform complex motor tasks with minimal spasticity, and functional movements become smoother and more coordinated.

Neuroplasticity

I'm sure everyone here has heard of neuroplasticity—it’s drilled into us pretty thoroughly when working with individuals recovering from neurological conditions. The concept is fundamental to rehabilitation because it underpins the brain’s remarkable ability to reorganize itself by forming new neural connections.

We know the brain can adapt—whether through compensatory pathways or by strengthening weaker connections—and this ability can be incredibly powerful in helping people recover lost function. But it's important to remember that neuroplasticity can work both ways. While it can support recovery, it can also reinforce maladaptive patterns if not guided properly. For example, if someone continually uses abnormal movement patterns or compensates with their stronger side, those patterns can become ingrained, making it more difficult to relearn optimal function later on. So neuroplasticity is an incredible tool, but how we engage it in therapy is crucial—it can either help or hinder the recovery process, depending on how it's harnessed.

Use it or lose it | Use it and improve it | Be specific | Repetition is essential | Intensity matters |

Age matters | Transference | Interference | Patient expectation | Salience is important |

Reward or feedback | Environment | Fun | Helping others |

One of my favorite sayings that I share with every patient—whether they’ve had a stroke, a spinal cord injury, or even something like a carpal tunnel—is to use it or lose it. The principle is simple but powerful: if you stop using a part of your body, the muscles will begin to waste, your brain will start to ignore that area, and the function will decline. Over time, you really can lose the ability altogether. This is particularly true in stroke rehabilitation, where neglect is often an issue. Promoting the use of the affected side, even in small ways, is critical. Whether washing their hands together or using the affected hand to help turn off a light switch, those small movements give that limb importance and keep it neurologically relevant.

You also have to use it to improve it—meaning not just using the limb but doing so with purpose and focus. Specificity matters. If you want to improve a particular task, you have to practice that task with intention until the person reaches competency. And that requires repetition. We’re talking hundreds of repetitions to drive change, which can be tough in a typical treatment session. If you only have 30 minutes or an hour, getting that level of intensity is a challenge.

That’s where integrating tasks into treatment becomes incredibly valuable. I often find I can get far more repetitions out of someone if the activity is tied to a functional or meaningful task. Instead of doing 50 bicep curls, I might strap a spoon or fork to their hand and have them practice bringing it to their mouth. That motion is neurologically familiar—something the brain recognizes and understands. And it’s often easier for patients to engage in that motion because it’s tied to an actual function, like eating. Of course, safety comes first—make sure nothing will fly up and poke them in the eye—but using objects like Velcro, gloves, or beads can simulate real-life tasks. If a person has limited grip or tone, those supports help them participate while still getting valuable movement.

This brings us to the concept of salience. Making tasks relevant and interesting to the patient is a key piece of neuroplasticity. The brain responds better when the activity matters. So we try to align tasks with patient goals, expectations, and past roles. At the same time, we need to temper unrealistic expectations. I always encourage patients not to adopt a doomsday mindset—one of my biggest pet peeves is when someone says, “Well, it’s been six months. You’re not going to get anything back.” That simply isn’t true. I’ve worked with patients twenty years post-stroke and still seen progress. One of my patients, for example, recently achieved improved active flexion and supination. Another gained better grip strength—things they were told wouldn’t return. Progress may be slower and take more effort, but it is absolutely possible.

Another principle of neuroplasticity is interference, which refers to the need to prevent compensatory movements from becoming dominant. If a patient always relies on the stronger side, those compensations can block recovery. So part of our job is to interrupt those patterns and promote more appropriate ones. Then there’s transference—the ability to apply a skill learned in one setting (like the clinic) to another setting (like home). We aim for carryover because that’s where function really starts to return.

Age is another factor often discussed in recovery. The common belief is that younger individuals recover better and faster, while older individuals have limited potential. But in my experience, that isn’t always the case. I’ve had a patient in her 30s who was one year post-stroke and still completely flaccid in her arm with no return, and another in his late 60s who, just three months post-stroke, had almost full return of function. So yes, age matters to some extent, but it should never determine how much effort we invest in someone’s care. Don’t dismiss a young person, assuming they’ll recover spontaneously, and don’t overlook an older person, thinking they won’t improve—give every patient the full benefit of your effort, regardless of age or how long it’s been since their stroke.

Reward and feedback are also essential components of neuroplasticity. This is one of my favorite aspects of treatment. Many of our patients are dealing with depression or discouragement. They may feel like they’re not making progress because they can’t move their arm or walk the way they want. So I always give feedback. If I feel even a trace of movement in the bicep or tricep, or twitching in their fingers, I point it out. If I’m assisting them less during active movement, I tell them, “You’re doing more of the work this time.” I don’t give false hope—I never say I see movement if it’s just reflexive—but I do share every genuine sign of progress. That feedback can make a huge difference in their mindset and motivation, especially when they’re in the middle of a very difficult and life-altering recovery process.

Making therapy fun and meaningful also ties into this. Helping others is another powerful motivator. When someone loses their role—like being a provider, a parent, or a caregiver—they often experience a deep sense of loss and decreased self-worth. So, if we can help them regain even a part of that role, it can significantly boost their emotional and psychological well-being. Helping them feel useful again can be a turning point in their rehab journey.

Finally, the environment matters. Whether you’re in a sterile clinic or simulating tasks in a kitchen or laundry room, the setting affects how the brain interprets and responds to activity. The more you can diversify the environment and simulate real-world tasks, the more effective your interventions will become.

I want to end this section with a story. I had a patient who was once a competitive ping-pong player and loved gardening. So, I built our sessions around those two things. We simulated planting seeds for fine motor coordination, and I gave him a ping pong paddle to practice hitting a ball. Watching him light up when he could hit that ball was amazing. His reaction time improved, his supination improved, his wrist movement improved—and more importantly, he felt better. He was often down on himself, feeling like he’d never improve. But doing something deeply tied to who he was allowed him to reconnect with his identity and purpose. He completed more repetitions and was more engaged in the session because it mattered to him and was something he believed he could return to. That’s what neuroplasticity is really about—engaging the brain in meaningful, relevant, and hopeful ways.

Rehab Stages

When working through the rehabilitation process, it's helpful to think about stages of motor learning.

Stage one is the cognitive stage. This is where the individual is learning a new task and must consciously think through each step. They rely heavily on vision and benefit most from a consistent, predictable environment. During this stage, a lot of planning and mental effort is required, and frequent errors and slow execution often characterize performance. Clear verbal cues, visual prompts, and structured guidance are essential.

Stage two is the associative stage, where the individual begins to refine the task through repetition. Movements become more fluid, and there are fewer errors and extraneous motions. Motivation, consistent feedback, and a well-organized environment help facilitate progress in this phase. The person is starting to internalize the motor sequence and doesn’t require quite as much external input or visual monitoring.

Stage three is the autonomous stage. At this point, the motor program is well-practiced and refined, so minimal conscious thought is needed to perform the task. The individual can carry out the activity in a more complex, distractible environment with fewer cues and less assistance. This is where the task becomes automatic and generalized beyond the structured clinical setting.

So, when you guide someone through rehab, you're essentially moving from a highly structured and supported learning environment to one that is more dynamic, with greater independence and real-world application.

Interventions

Here are some different interventions that you can do.

Visual

For visual rehabilitation, particularly following a stroke, a number of strategies and tools can be used to address both visual field deficits and visual neglect.

Compensatory techniques are key when dealing with a visual field deficit. One of the most effective ways to increase awareness of the impaired side is prism field expansion, wide-field eye movement therapy, and adaptation training. These interventions aim to retrain the brain and eyes to recognize the space that has been neglected or lost due to the stroke.

There are also simple, yet powerful techniques you can use in practice. For instance, if a patient is sitting at a table, you can place an object—such as a cup—just outside of their visual field on the impaired side. Let them know where it is so they are prompted to scan in that direction when they need it. Similarly, placing a commonly used item like a remote, a favorite snack, or a pencil to the affected side encourages scanning. This repeated scanning helps the brain relearn that the neglected side exists. It’s the act of consistently using their eyes to search that stimulates the brain to reintegrate that side of their visual field. The same strategies can be used for patients with visual neglect—promoting search patterns is crucial, and this can also be part of their home program to increase carryover.

Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy (CIMT) is another evidence-backed approach that can help, particularly for addressing neglect. By constraining the unaffected limb, the patient is forced to use the affected side for daily tasks. This can be as simple as turning off a light switch, brushing their teeth, or picking up a bag with the affected hand. It encourages cortical engagement and re-mapping, and has been shown to support functional improvement on the neglected side.

Visual tracking exercises are also beneficial. One method is using transport tape, which involves placing tape over the lens on the unaffected side to encourage looking toward the neglected side. That said, some individuals are so strongly inclined to look toward the unaffected side that this method alone may not work. In those cases, combining tracking with functional tasks—so their eyes must move intentionally in that direction—can be more effective.

In sixth or third nerve palsy cases, patients often experience double vision and ocular motor issues. These typically resolve on their own within six to eight months. In the meantime, taping one eye can help reduce visual strain and double vision, improving comfort while the nerve heals.

For visual information processing disorders, a range of engaging and functional exercises can be used. These include the “see it, say it, do it” technique and various tracking activities like pursuits with pie pan or pencil rotations. Using marble rolls and tracking everyday objects helps make these exercises more relevant and functional.

To train saccades—the ability to shift focus between two objects—you can incorporate card scanning, heart chart drills, and scanning for five-letter words. These help improve the ability to move the eyes quickly and accurately.

When working on convergence, exercises like the Brock string and pencil push-ups are highly effective. The Brock string is a tool made of a string with beads or markers that can be adjusted along the length. It’s helpful for both convergence and accommodation training. For accommodation, you can also have patients copy text from a large print sheet placed ahead of them, encouraging focus and eye movement adjustment. Combining tools like the heart chart with the Brock string helps make this training more robust and engaging.

Altogether, these tools and techniques support a comprehensive visual rehabilitation program that can significantly impact functional outcomes and quality of life for stroke survivors.

Physical

We briefly touched on Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy (CIMT) earlier, but I want to recommend diving deeper into the work being done at the University of Alabama. They have an excellent program with strong research and audits supporting the effectiveness of CIMT. If you’re interested in exploring it further, that’s a great place to start.

In essence, CIMT involves constraining the unaffected limb to force the use of the affected side. This not only encourages motor activity but also drives the brain to devote more attention and neural energy toward that side—helping with issues like neglect. There are several creative ways to constrain the unaffected side: using an oven mitt, having the individual sit on their hand, or even securing it gently with a gait belt. The key is to increase reliance on the affected side.

CIMT relies on high-intensity repetition, often aiming for hundreds of repetitions in a single treatment session. While that may seem daunting, it’s foundational to driving neuroplastic changes.

A related and promising approach is multimodal mental imagery, which combines action observation with mental imagery. In action observation, the patient watches someone perform a task—such as making coffee. Then, they close their eyes and visualize themselves completing the same task with their affected limb. This isn’t just about imagining the movement; it’s about engaging all senses—feeling the texture of the coffee mug, hearing the gurgling of the machine, and smelling the coffee aroma. That full sensory engagement activates broader brain regions and improves the effectiveness of the imagery. Repetitions after mental imagery tend to reinforce motor learning.

I highly encourage incorporating mental imagery into home programs. It’s a low-fatigue, low-equipment option that patients can do even when exhausted from a full therapy session. There are also helpful YouTube videos guiding patients step-by-step through mental imagery practices.

Now, onto E-stim—something I cannot stress enough: E-stim must be combined with a functional task. Too often I see therapists apply the unit, walk away, and expect the stimulation alone to lead to functional improvement. Instructing a patient to “try and move with it” doesn’t guarantee meaningful engagement. If they’re not mentally involved—if they’re on their phone or zoning out—you’re not getting the neuro-reeducation component that’s so essential.

For example, I had a patient who couldn’t move most of their arm. I used E-stim to assist with grasp and release while incorporating a functional task. We placed a towel on the table for a towel slide. The patient reached and grasped an object using E-stim assistance and then used their unaffected arm to help slide the affected arm across and release the object. This targeted grasp, shoulder and elbow activation, and cortical engagement—combining strength, function, and repetition. Even in cases with very limited voluntary movement, we can creatively involve the entire limb and the brain through structured tasks.

Passive Range of Motion (PROM) is useful, especially for preventing contractures and maintaining muscle length. But I consider it a preparatory activity, not a primary intervention. I rarely spend more than 15 minutes on PROM. Active-assisted ROM, where the patient exerts some effort, has more therapeutic value in terms of strengthening and cortical activation.

Mirror therapy has gained a lot of research attention, particularly as the third stage of graded motor imagery. This process starts with right-left discrimination, then mental imagery, and finally mirror therapy. In mirror therapy, the affected limb is hidden, and the unaffected side is mirrored to create the illusion of movement. This visual trickery sends strong neural signals to the damaged hemisphere, encouraging cortical reorganization. It’s also been shown to help with phantom limb pain and other pain conditions, not just stroke recovery.

Splinting still has a place in rehab, particularly for preventing contractures or managing abnormal tone. However, it’s one tool in a much broader toolkit and should be part of an overall plan that includes dynamic intervention.

Task-specific training is exactly what it sounds like—identifying a meaningful, functional task (like pouring water or cutting food) and working toward competency through repeated, structured practice. Relevance and repetition are key.

Now let’s talk about muscle tone, which is often overlooked but critically important. Many stroke patients develop abnormal tone, particularly tightness in the pectoral muscles. That tightness causes internal rotation of the shoulder, which restricts forward and lateral arm movement. If this isn’t addressed, it significantly limits functional use. Often, patients are being asked to strengthen weak muscles while simultaneously fighting against stronger, hypertonic muscles. That’s a setup for failure and frustration.

This is why soft tissue release should be part of your approach. Take time to palpate, assess, and treat the tissue. Is the hand curling in due to a true contracture, or is it tight flexors or extensors? Identifying the root cause allows for better planning. If needed, apply gentle release to loosen tight areas and allow for more normalized movement patterns.

Kinesiology taping is another technique you can explore, although I have mixed feelings about it, particularly for shoulder subluxation. The arm is heavy, and I haven’t seen strong results using tape alone to support it. In fact, skin irritation or integrity issues are a bigger concern in those cases. That said, I’ve found taping helpful for internal rotation of the shoulder. It provides sensory feedback, cueing the patient to bring the shoulder into a more neutral or functional position. If you use tape to support or inhibit movement, limit stretch to no more than 30%—going beyond that increases the risk of skin issues, and there’s no evidence of added benefit.

All of these tools—whether CIMT, E-stim, mirror therapy, splinting, task-specific training, soft tissue release, or taping—are most effective when applied thoughtfully, with the individual’s needs, goals, and movement patterns at the center. The more functional, engaging, and personalized the intervention, the more neuroplastic potential you’ll tap into.

Cognitive

When it comes to approaches to rehabilitation, you generally have two main frameworks: the hierarchical approach and the compensatory approach.

The hierarchical approach is structured around starting with simpler tasks and gradually increasing the complexity as the individual progresses. It’s about building skills back up, step by step. This might involve starting in a quiet, distraction-free environment and slowly introducing more sensory input or environmental challenges. Tasks evolve from simple to complex, and cognitive demands shift from concrete to more abstract as the person regains control and function.

On the other hand, the compensatory approach focuses on helping the person function as independently as possible using compensatory strategies rather than trying to restore lost abilities right away. This might include using adaptive equipment, modifying the environment, or teaching new ways to accomplish a task with their current level of ability.

In my own practice, I almost always combine these two approaches. I like to start with a compensatory strategy so the person can participate in their daily routine right away—because immediate function matters. This helps with safety, independence, and motivation. But I also work in the hierarchical approach alongside it because the ultimate goal is to help them regain as much use and control over the affected side as possible.

So while compensatory strategies allow the patient to function now, the hierarchical work helps them move toward greater true independence and restored ability. I believe that using both together offers the best chance for meaningful recovery.

Restorative

While much of what we’re working on can certainly be reinforced at home when we’re in the clinic, our focus shifts to truly building up and restoring what’s been lost. That’s where restorative rehab comes into play, especially when we’re talking about cognition and attention.

Attention itself is layered—there are five levels, and a person can’t move on to the next until they’ve achieved some competency at the one before it. Toward the higher end of those levels, we see divided and alternating attention. Divided attention is when someone can manage two things at once, giving about equal focus to each—like talking while doing a puzzle. It’s not the best example, but it captures the idea of engaging in two different types of tasks simultaneously. Alternating attention, on the other hand, is the ability to switch back and forth between tasks. A great example of this is cooking. You might be preparing rice and also cooking chicken—both require attention, and you have to alternate your focus between them so that neither overcook nor burns.

I always bring up driving when I’m talking about these types of attention. If someone is going to return to driving, they have to have both alternating and divided attention. Think about it—there’s a conversation happening in the car, the radio might be on, and they’re processing everything happening on the road. They have to constantly shift attention: is a car pulling out? Is someone merging? Is the light ahead turning yellow? It requires high-level executive functioning. So when I’m evaluating attention in stroke survivors, especially those with more severe injuries, I often find that the deficits lie in the lower levels—focused, sustained, and selective attention.

Focused attention means being able to attend to just one thing. Sustained attention means staying with that task over a period of time. Selective attention is where you start to tune out distractions. So, if they’re trying to complete a task, but there’s background noise, and they can’t stay on track, I know we’re working with lower-level attention.

And here’s the thing—if you want to know where someone is at with their attention, you need to give them a task that’s meaningful. I can hand someone math problems and watch their attention fall apart—but if I give them putty to work with or something they enjoy, their focus often improves dramatically. You’ll get a more accurate read on their true capabilities when the task is something they care about. It has to be engaging. From there, I always recommend starting with the simpler attention tasks and gradually increasing difficulty until you get to those alternating and divided levels.

When it comes to memory, I lean into a variety of strategies. Repetitive practice is a solid foundation, but I also use things like vanishing cues, errorless learning, and chaining—either forward or backward—depending on the person and the task. These methods reduce frustration and help build confidence, especially when memory is significantly impaired. I’ll also integrate proprioceptive input, sensory stimulation, cueing, and active-assistive range of motion where appropriate. These techniques provide extra layers of input that support memory consolidation.

Ultimately, whether I’m focusing on attention or memory, I’m always trying to find that balance—giving the patient the tools they need to manage daily life through compensatory strategies while still pushing them toward recovery and the potential for greater independence through restorative work.

Memory Notebooks

Memory notebooks are a great example of a compensatory approach to memory deficits. They serve as an external aid to support daily functioning when internal memory processes are impaired. There’s a specific step-by-step process to follow when introducing memory notebooks, and it’s important to be intentional with how they’re implemented to ensure the best outcomes.

The first step is anticipation. This is where we raise the client’s awareness about their memory difficulties and how those deficits are impacting their daily lives. It’s not just about recognizing the problem—it’s about helping them understand that there are practical, usable solutions. This is also when we begin to introduce the concept of the memory notebook and start building buy-in.

Next comes acquisition. This is the familiarization phase, where both the client and their family become comfortable with the notebook—what it is, how it works, and when to use it. You might start by helping them integrate external cues that remind them to refer to the notebook regularly. Over time, those cues will fade, but early on, they’re key to developing the habit.

The third phase is application, and this is where the real functional training begins. You’ll work with the client through role-playing, practicing how and when to use the notebook in real-time situations. Consistency is absolutely essential here. They need repeated exposure to using it in meaningful contexts to develop reliance and comfort.

Finally, there’s adaptation. Once the client has mastered using the memory notebook in structured settings, it’s time to start applying it in the community. This might include using it during appointments, grocery shopping, or while out with family or caregivers. The therapist can accompany the client initially to support the transition, but again, that support should fade over time as independence grows.

It’s a straightforward yet powerful tool, and when introduced properly, memory notebooks can significantly improve someone’s autonomy and confidence.

Addressing Behavioral Issues

Our brains are naturally wired to respond to patterns—especially those built around antecedents, behaviors, and consequences, or what we commonly call the ABC model. It’s how we learn to navigate the world, how to gain rewards, and how to avoid unpleasant outcomes. So when we’re trying to reduce problematic behaviors, it’s important to tap into that system in a way that’s both structured and meaningful.

One method that works particularly well is Differential Reinforcement of Other Behavior (DRO). This approach provides a reward when a specific, undesirable behavior has not occurred for a certain period of time. For example, if someone goes ten minutes without engaging in the behavior you’re trying to reduce, they might get a small reward—a compliment, a sticker, a piece of candy—whatever feels motivating and meaningful to them. The goal is to reinforce the absence of the behavior.

Then there’s Differential Reinforcement of Incompatible Behavior (DRI). This is where you identify a behavior that cannot physically happen at the same time as the undesirable one and reinforce that. For instance, if someone tends to grab at others and you’re working on reducing that, you might teach them to put their hands in their pockets or sit on their hands. These actions are incompatible with grabbing, so when they choose one of those instead, you reinforce it.

Another tool is Differential Reinforcement of Alternative Behavior (DRA). This one’s fairly straightforward—you ignore the undesired behavior and reward the alternative. So if someone is talking out of turn, rather than reacting to that, you withhold attention. But the moment they’re quiet and appropriately engaged, you praise or reward them. It’s similar to parenting techniques—when a child is throwing a tantrum, you might not respond to the tantrum, but you’re quick to acknowledge and reinforce the calm behavior that follows.

And finally, there’s Differential Reinforcement of Low Rate Behavior (DRL). This strategy is especially useful when a behavior doesn’t need to be eliminated entirely but just reduced. Let’s say someone is having 20 verbal outbursts a day. Instead of expecting zero overnight, you work with them to bring it down incrementally—maybe to 15, then 10, and so on. Each reduction is a target that, when reached, earns reinforcement. This is a more gradual and realistic method, especially for behaviors that are deeply ingrained.

These reinforcement strategies are all grounded in understanding the function behind behavior. When used consistently and paired with tasks or goals that matter to the person, they can be incredibly effective in shaping behavior in a positive, supportive way.

Relaxation Techniques

Here are just some relaxation techniques for mental health and to improve some of that muscle tone. You've got progressive muscle relaxation, guided imagery, mindfulness breathing exercises, which is excellence exercise to also incorporate that deep breathing which helps stimulate calm.

Best Vitamins for Brain Recovery

For my last slide, here are the best vitamins for brain recovery. There are omega-3s, vitamin B12 and MCT oil, antioxidants, vitamin D probiotics, and acetyl L carotene in case you want to give your patients a sheet on just some things that can help boost brain health and recovery.

Summary

Thanks for joining us today. I hope this information is useful to you.

Questions and Answers

How do you determine if a patient is appropriate for Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy (CIMT)?

Assess the patient's cognitive status first. CIMT requires the patient to understand the purpose and process of the treatment, so individuals with significantly impaired cognition who cannot comprehend what they're participating in should not be considered for this approach. Ethical practice dictates that patients must be aware of and able to consent to such interventions.

What alternatives to kinesio tape would you recommend for shoulder subluxation?

While kinesio tape can be useful, alternatives like the GivMohr sling provide more natural arm positioning and are commonly used to support shoulder subluxation. Additionally, strong shoulder braces may also offer effective support. Be cautious with traditional slings, as they can contribute to elbow contractures and promote internal shoulder rotation.

What is the most challenging part of stroke rehabilitation, and how do you manage it?

One of the biggest challenges is addressing post-stroke depression, which can cause patients to become despondent and disengaged. Building a strong therapeutic relationship is key. Start with simple, rewarding tasks to foster a sense of accomplishment. Emotional support and encouragement play a significant role in motivating patients to participate and make progress in therapy.

Do you recommend splints for patients post-stroke?

Yes, in certain cases—especially when the patient has hand contractures. Resting hand splints can be beneficial, but they should not be used in isolation. For optimal results, intensive therapy that includes stretching, electrical stimulation (e-stim), and other active interventions should accompany splinting.

Thanks for your time today.

References

See additional handout.

Citation

Nauck, L. (2025). Stroke rehab: Evaluation and treatment. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5795. Available at www.occupationaltherapy.com