Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Towards A Better Understanding Of Self-Regulation And BEST Strategies In Partnership With Moira Peña Sensory Workshops, presented by Moira Pena, BA, BScOT, MOT Reg. (Ont).

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to:

- Examine the 5 domains that contribute to self-regulation.

- Analyze the importance of considering neurobiological correlates of stress when addressing challenging and/or interfering behaviors.

- Examine one key concept from each of the BEST (Body, Emotional, Sensory and Thinking) Strategies that support self-regulation in school-aged children and youth.

Introduction

Welcome everyone to this workshop.

What is Self-regulation?

Teachers tend to be familiar with Dr. Stuart Shanker's Model of Self-regulation, and he has a book as well (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Shanker's Model of Self-regulation (Shanker, 2016; www.self-reg.ca)

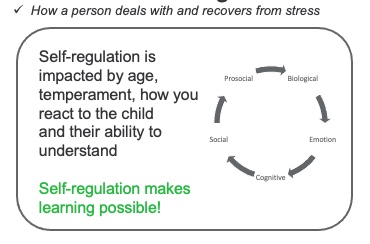

The way he describes this model is that self-regulation is how a person deals with and recovers from stress. In his model, five domains impact self-regulation. I am going to give you examples of the stressors that are under each domain.

Biological Stressors

Biological stressors can include if the child is hungry, thirsty, tired, or spending too much time in front of a screen. A child could have allergies, feel ill, or have sensory processing differences. The classroom fluorescent lights may emit a sound that is painful to the child.

You can put some other biological stressors in the chat:

- Headaches

- Fire alarm

- Noise

- Preteen hormones

- Tactile labels in clothing

- Missed their morning medication that morning

- Sitting too close to others

- Room temperature

- Socializing with other students

Emotional Stressors

An emotional stressor can be embarrassing, like holding their parent's hand to cross the street. A child new to a school may be uncomfortable socializing with other kids. Think about the emotional stressors from the upcoming holidays.

Here are some chat examples:

- Taking tests

- Decreased confidence with a school subject

- Divorce

- School anxiety

- Being called on in the classroom

- Fighting with friends

- Family dynamics

- Transitions

Cognitive Stressors

Cognitive stressors may include learning something new or learning a new language. For example, I moved to Canada when I was 15, and I did not speak English. The stress of having to learn a language was exhausting. Putting much effort into something very taxing and tiring can be stressful. You can understand why kids may be irritable. They may have memory lapses or forget a word.

Examples of cognitive stressors from the chat:

- Writing demands

- Learning disability

- Learning to tie your shoelaces

- Dyslexia

- Attention difficulties

- Pressure to do well

Pressure to do well is pervasive in our society today.

Social Stressors

What stressors can you think of in terms of a child's social situation? Think about the stress of attending a birthday party or having a birthday party. My kids had parties that did not go very well. They were too stressed about their toys being taken. Bullying and public speaking are other areas. I also have to say that presenting a webinar is stressful.

Here are some of your ideas:

- Being the new student

- Family issues

- Having to share

Pro-social Stressors

Let's talk about the domain that Dr. Stuart Shanker calls pro-social. It also includes others' distress. I think watching or reading the news is a big one, especially after the trauma from the pandemic and getting back to life as we knew it.

Here are some comments from the chat:

- Another student is having a behavioral outburst

- Anticipatory fear of a hurricane

- Seeing a friend not do well or get sick

- News about school shootings

All of these stressors are part of life now. Dr. Stuart Shanker says that all of these stressors impact one another. Stressors in one domain can multiply stress in other areas.

The stressors that I will talk about today are related to the biological and emotional domains. Otherwise, we will be here all day. I also want you to consider that self-regulation is impacted by age, the child's temperament, and how you, as a therapist, react to the child and their ability to understand.

I also need you to consider that self-regulation makes learning possible. There is a proven correlation between your ability to regulate and how well you do in school. It is not related to IQ. You could have a very high IQ, but have so many stressors that you are not able to function in school.

Behavior is Communication

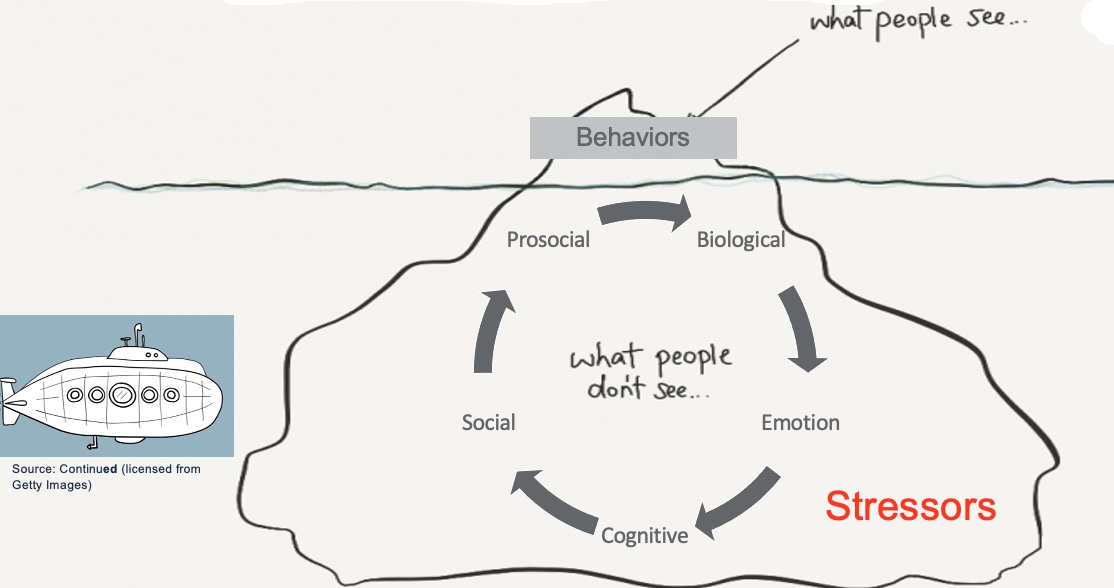

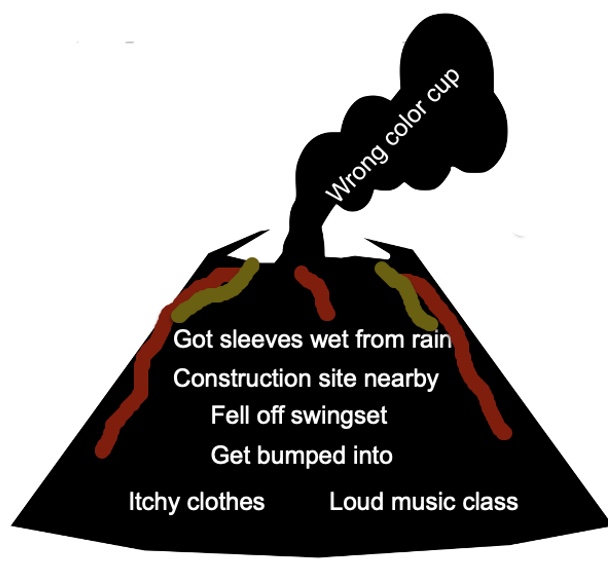

As occupational therapy practitioners, we believe behavior is communication, and communication is behavior. Behavior is showing an unmet need. I would even go further to say that challenging behavior is communication. When you think of the behavior on top of the iceberg in Figure 2, you see the behavior, but you need to consider the many different reasons for that behavior.

Figure 2. An infographic shows that stressors are below the surface like an iceberg.

These different domains under the water impact behavior. I always use iceberg models when talking to parents. "Let's think about all the stressors, exactly how you responded, and how that could impact their behavior." We then talk about stressors and how they can be decreased. The submarine is a metaphor for helping the person figure out the stressors and how to prevent or decrease them.

Shifting Practice: The Need to Understand the Relationship Between Our Neurobiology and Our Behaviors

- Our personal and interpersonal neurobiology affects our ability to regulate ourselves and how we behave!

A shift in practice is understanding the relationship between neurobiology and behaviors. Interpersonal neurobiology affects our ability to regulate and behave. I will talk to you about some of this exciting research that shows how our chemistry reacts differently, depending on the person with which you are engaging.

The Developing Brain: The Red Brain vs.The Blue Brain

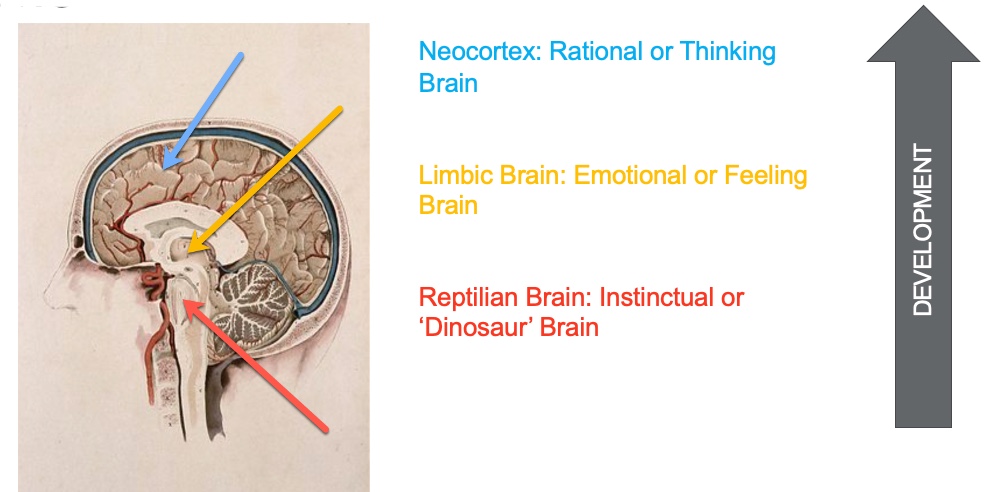

To understand behavior, we need to understand the developing brain. If we are talking to teachers, we need to keep things simple. The first thing is comparing the red versus the blue brain. Again, this is Dr. Stuart Shanker's way of explaining this neurobiology (Figure 3).

Figure 3. An infographic comparing the red brain versus the blue brain. Image source: Continued (licensed from Getty Images).

At the bottom is what we call the reptilian or the red brain. This is your instinctual or "dinosaur" brain. It controls your body's vital functions, including heart rate, breathing, body temperature, balance, and sensory processing. These are automatic functions that you do not think about. Most of the sensory systems are processed at this level of the brainstem. For example, you do not have to think that certain receptors keep you upright while attending this webinar.

Next is the limbic brain or emotional brain. This is where you have strong feelings of love, hate, and desire.

They all have their home in the limbic brain. It controls your emotions and memories. It contains regions that detect fear and control bodily functions. It also perceives some sensory information.

The last is the blue brain or the neocortex, the rational or thinking brain. Here is where the executive functions reside. The prefrontal area of the neocortex is where you make intentional decisions.

We will talk more about the blue brain in a moment, but I want you to think about the way the brain develops from the bottom up and from the inside out. It is hierarchical, where the basic cortex develops first and, lastly, the blue brain.

Stress & The Brain

- If the child is experiencing stress, they are UNABLE to think and act purposefully. They are NOT IN CONTROL of their behaviors.

- Prefrontal cortex (Executive Functions -> Blue Brain)

- Processing what is happening in the moment

- Recall from past similar experiences

- Weighs past experiences with current ones

- Makes a decision & acts on it

The blue brain and prefrontal cortex process what is happening in the moment and help you recall past similar experiences. It weighs past experiences with current ones, makes a decision, and acts on it. This is also where we find self-control or a willful intention for you to control your behaviors.

Self-control is not the same as regulation. If we are experiencing stress, we are enabled to think and act purposefully if we lose control. An example is road rage, where a person loses access to their thinking brain because of all the stressors around driving. Another example is the stress of shopping and saying mean things. These examples show that the connection between the red brain and the blue brain is compromised.

- Never in the history of calming down has anyone ever calmed down by being told to calm down!

Research shows that stress affects language and communication. There is a disconnect between the red and blue brains, and language can be compromised. We often tell kids to calm down or use their words when they are at the height of stress. We are using all these words to help manage the behavior no longer within their control, as they are in fight or flight mode. The use of language at the height of a meltdown is never going to be helpful.

We need to use other techniques, and that is what I am going to discuss today.

Prefrontal Cortex Development

- The prefrontal cortex cannot be fully relied upon until it is fully myelinated

(Hoch et al., 2015; National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2020; Siegel, 2012)

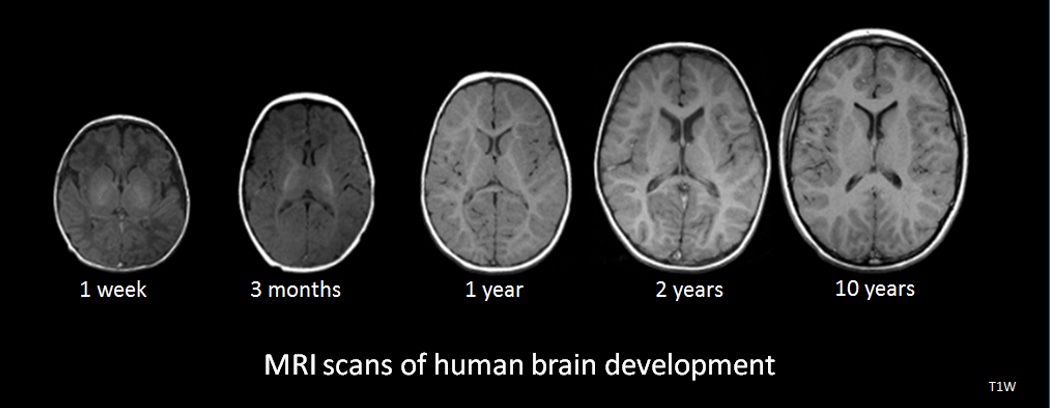

We also need to consider that your prefrontal cortex is not fully developed until your mid-20s and then some. Figure 4 shows some MRI scans of a developing brain.

Figure 4. MRI scans of human brain development. Source: National Institutes of Health, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

We need to have a compassionate stance when working with humans that do not have a fully developed blue brain or executive functioning. Their decision-making is impaired, and this is helpful to keep in mind if you have teenagers at home. The prefrontal cortex cannot be fully relied upon until it is fully myelinated. The brain is still developing, which is why we talk about the risk of taking drugs during this period and the long-term consequences of that.

Neurodivergent People

- I love words. Words have opened worlds for me. The way I use words reflects my AUTISTIC neurology. Words will often fail me when I need them most. @hvppyhands

We also need to look at stress in the people who we support. I work with autistic and neurodivergent people. When stressed, it multiplies, and the connection to your language center in the blue brain is impacted. Again, brain development is something to keep in mind when you are looking at behaviors.

Physiological Correlates of Stressed Behavior

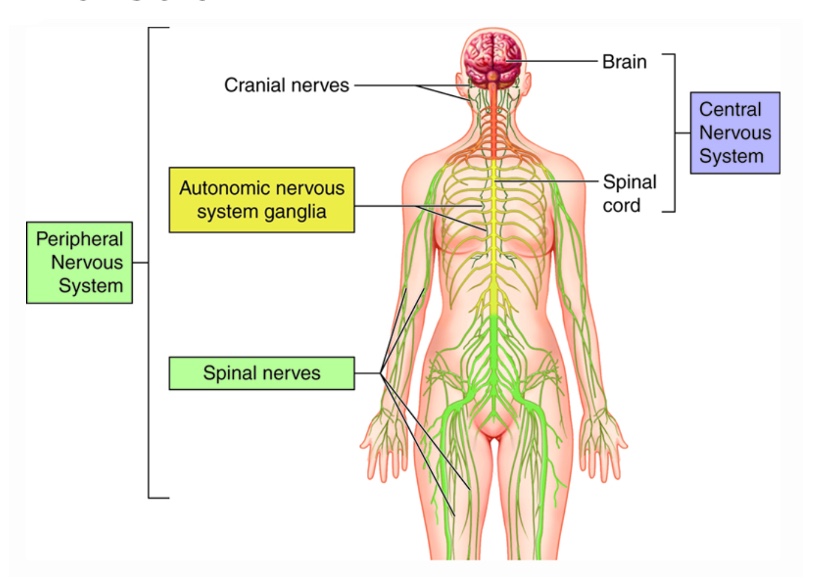

- Central nervous system (CNS): Brain & Spinal Cord

- Perceives and interprets threat

- Modulates peripheral responses

- Autonomic nervous system (ANS):

- controls involuntary bodily functions & regulates glands

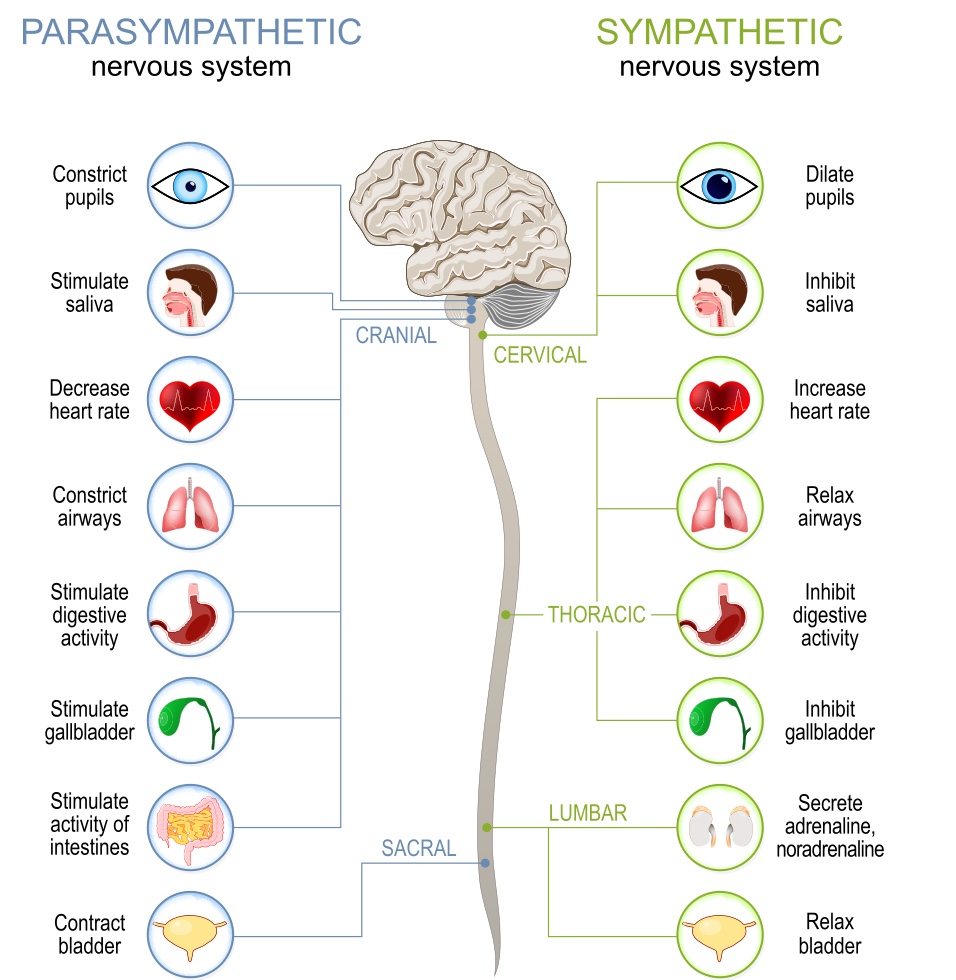

- Sympathetic nervous system (SNS) & Parasympathetic nervous system (PNS)

- “Fight/Flight/Freeze” response

We also need to think about how our physiological status correlates with stress behavior. The central nervous system (CNS) includes the brain and spinal cord, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Central nervous system.

The CNS perceives and interprets threats, and then modulates peripheral responses. The autonomic nervous system, ANS, controls involuntary bodily functions and regulates the glands. We now understand much more about the two branches of the ANS, which are the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. These operate the fight, flight, and freeze responses that we are going to talk about in a little bit.

How Our Bodies Respond to Stress

Figure 6 shows how our bodies respond to stress.

Figure 6. Infographic of how our body responds to stress.

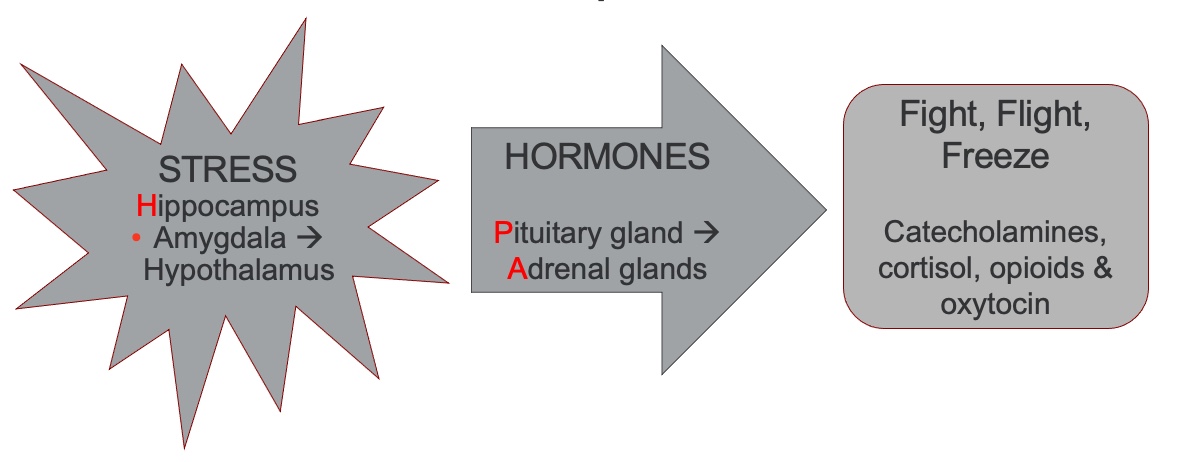

HPA Axis Stress Hormones & Behaviors

- 4 main hormones are released in response to stress

- Cortisol

- Catecholamines

- Opioids

- Oxytocin

- We all have our own personal & interpersonal neurobiology!

When stressed, your body sends signals to the HPA axis.; H is for the hippocampus, P is for the pituitary gland, and A is for the adrenal glands. Stress messages are sent to the amygdala. Remember, the amygdala is in the brain's center that looks for threats and helps with memory. That system then sends messages to the pituitary gland and adrenal glands, which then release stress hormones into the body. Stress hormones that I will discuss today are catecholamines, cortisol, opioids, and oxytocin, all of which are involved in the fight, flight, freeze, or sympathetic overdrive state.

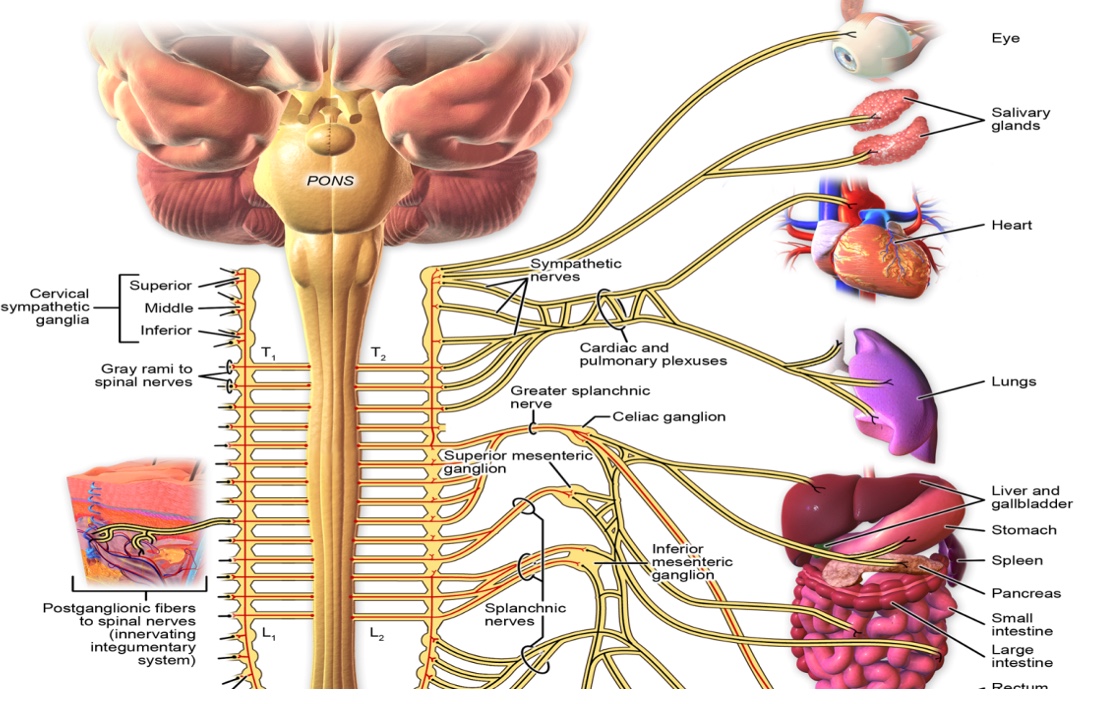

The visual in Figure 7 shows exactly what happens when your body is in sympathetic overdrive.

Figure 7. Infographic of what happens to the body during sympathetic overdrive. Source: Continued (licensed from Getty Images)

I want to highlight a couple because they are relevant to some of the behaviors that you see. Sympathetic overdrive inhibits digestive activities. Think about all the kids who have difficulties eating at school or at home. When a person is stressed or anxious, their digestive system will shut down, making it more difficult to eat. Additionally, the body will relax the bladder, so the person will need to use the bathroom a lot more. We see many kids needing to often go to the bathroom. We may interpret that as the child trying to escape an activity or the classroom. However, neurobiologically speaking, they may need to use the bathroom more because they are in sympathetic overdrive.

Let's now talk about those four main hormones that are released in response to stress. As I said before, we all have our own personal and interpersonal neurobiology.

1)Cortisol

- Prepares the body for fight/flight/freeze

2)Catecholamines or adrenalin

- Executes fight, flight or freeze response

Cortisol prepares the body for fight, flight, and freeze. Catecholamines or adrenaline execute those responses. Once in a sympathetic overdrive, you may see these bodily reactions in a child that may explain some adverse behaviors.

Figure 8. Sympathetic innervation of the different body parts. Blausen.com staff (2014). "Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014". WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 2002-4436., CC BY 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

3)Opioids

- Body’s natural pain killer

- Our ‘natural morphine’

- Blocks physical pain that may be experienced during a major stressful event

- May also mask emotions and limit emotional affect (Hoch et al., 2015)

Opioids are the body's natural painkiller or natural morphine. It blocks physical pain that may be experienced during a major stressful event. For example, if you hurt yourself, you are going to get a surge of opioids that will help with blocking pain. However, it also masks emotions and limits emotional affect.

This was quite a breakthrough when I understood how this hormone works. Think of all the times that a child displays a flat affect. We often perceive that as disrespectful or non-compliant behavior. I was teaching a course, and a person mentioned, "Wow! I finally understand why my son does this at work." His boss perceived that as him not wanting to be at work, but it was the opposite. Internally, her son was in overdrive, but externally, he showed no emotion. This happens a lot with autistic people when they are in "shutdown mode."

Be cognizant that the behavior may be a sign of a high level of stress.

4)Oxytocin

- A hormone that promotes attachment & positive feelings

- In addition to opioids, our nervous system counters pain or stress by increasing positive feelings or "a natural high"

- Excessive oxytocin results in an "inappropriate" affect: smiling, giggling, laughing at "inappropriate" times, etc.

Oxytocin is also fascinating because it promotes attachment and positive feelings. When babies are born we talk about skin-to-skin contact. In addition to opioids, our nervous system counters pain or stress by increasing positive feelings by releasing oxytocin.

Excessive oxytocin can result in an inappropriate affect. For example, you may smile or laugh at inappropriate times, like at a funeral.

Remember, we all have our neurobiology, and some are more likely to have this cocktail mix. I definitely see the inappropriate affect when I am stressed, and it is involuntary.

When we see this behavior that we deem inappropriate, we have to think that it might be a surge of oxytocin.

Shifting Practice: Recognizing the Impact of Sensory Processing Differences & Our Need to Engage in Sensory Advocacy

- Our ability to process sensations impacts our behavior and ability to self-regulate, but we still underestimate how important these are!

I also want you to recognize the impact of sensory processing differences on the role of stress and behavior. As OTPs, we need to advocate for our clients because their ability to process sensations impacts their behavior and self-regulation because many underestimate how important sensory processing differences are.

What is Sensory Processing?

- Sensory processing is the way in which we interact with the world around us by:

- Taking in sensory messages from within our bodies & surroundings

- Interpreting these messages

- Organizing our purposeful responses

- Occurs at an unconscious level

- Ranges from sensory preferences & quirks to severe dysfunction

- Sensory processing helps us feel!

Sensory processing is the way in which we interact with the world around us by taking in sensory messages from within our body. We can feel hungry or thirsty or need to use the bathroom. We also get sensory input from the environment, like lights and sounds. The way we interpret these messages and organize them is what OTs call our purposeful responses or behaviors. It is important to remember that this occurs at an unconscious level in the red brain, where most sensations are processed.

The problem comes when something that should be unconscious takes up real estate in your brain, and you must give it cognitive attention. I would love for you to provide some examples from your clients. Think about the child who may have to visually guide their hand to their mouth during feeding to know where and how to put the spoon in their mouth. You may have a child without good body sense who has to look at their feet when going up the stairs, so they do not fall. Another example is that I can not hear my kids who are home because I am focused on this webinar. This is called sensory gating. Some people who experience sensory processing differences cannot do that; they can only pay attention to one stimulus. They require cognitive effort to block out extraneous stimuli.

We all have sensory preferences or sensory quirks, and some can have severe dysfunction. The important part is that sensory processing helps us feel. This is what we call interoceptive awareness. I am always nervous when I present, but my body reinforces that because my heart is beating rapidly, I am sweating, and I am speaking in a certain way.

Many people struggle with what their body is telling them. For example, many kids have difficulty identifying needing to go to the bathroom. Think about those who struggle with toilet training. Sensory processing is very important not only for our physiological functioning but also for our emotional functioning. Another example of interoception is how you know you are attracted to someone. Feelings of love are automatic in most, but some people need to think about it.

The Eight Sensory Systems

Figure 9 shows the visual, auditory, olfactory, gustatory, and tactile systems

Figure 9. Image of the five sensory systems. Source: Continued (licensed from Getty Images)

The Hidden Senses

Vestibular System

- Sense of body position & movement

Proprioceptive System

- Joint & muscle sense

Interoception System

- Sense of internal organs

We also have these hidden senses: the vestibular, proprioceptive, and interoception systems.

Vestibular System. The vestibular system is a sense of body position and movement. The vestibular system tells you if you are moving forward or backward, moving in circles, are upside down, how fast you are moving, and if you are accelerating or decelerating. It gives you information about balance. If your vestibular system is not functioning as effectively as you would like, and every time that your feet leave the ground, you feel like you are unsafe or going to fall, you are going to be irritable and cranky. Additionally, think about how many kids spin, go upside down, or tilt their heads in a certain way to get vestibular input. The vestibular system is the master sense because it is connected to a sense of safety.

Proprioceptive System. "Proprio" means property, "ception" means feeling, and combined is your joint and muscle sense. This system tells you where your body parts are in space without you having to look at them. For example, some kids do not have to look where their hands are when putting on a backpack, while others do. We can also think of the stair example again. Kids may need to look at their feet when going up and down, or they press too hard or stomp. Again, this could be misinterpreted as a child misbehaving or being loud on purpose.

Interoception System: I talked about the interoception system already. Interoception is the sense of internal organs and the recognition of emotion. How does it feel when your body is happy? We can talk with kids about the cues like a relaxed heart rate and a smiling face to help them to identify their emotions.

Sensory Processing Differences Prevalence

- In neurotypical populations:

- 5-16%

- Clinical populations:

- 60-90%

- Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

- Gifted children (issues with attention)

- Developmental disability (DD)

- Fragile X & other syndromes

- Schizophrenia/bipolar disorder

- Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD)

- Prematurity

- Trauma

- Anxiety

(Ahn et al., 2004; Ben-Sasson et al., 2009, James et al., 2011; Galiana-Simal et al., 2020; Jussila et al., 2020)

Sensory processing differences are prevalent in a clinical population, especially those with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, gifted children, developmental disabilities, fragile X and other syndromes, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, fetal alcohol spectrum disorder, prematurity, trauma, and anxiety. Sixty to 90% of kids diagnosed with those conditions experience significant sensory processing differences affecting participation. With autistic people, that number goes up higher, with about 93 to 96% experiencing these significant sensory processing differences.

Classification of Sensory Processing Disorders, Patterns, & Subtypes

- 53% of kids with SPD experience more than 1 SPD Type (Mulligan et al., 2021)

(Bialer et al., 2011; Miller et al., 2007; Miller et al., 2012)

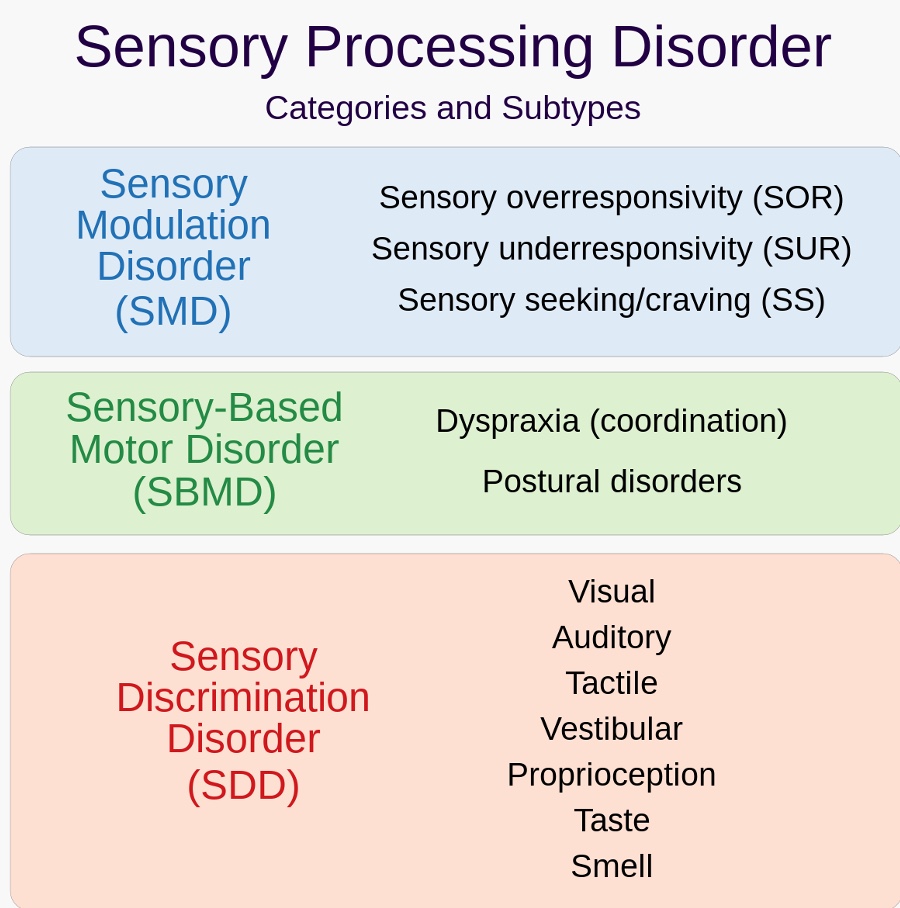

We cannot talk about behavior without thinking about what is going on in the sensory systems. There are lots of theories and exciting research happening around sensory processing differences. Sensory processing differences were recognized as one of the diagnostic criteria for autism, in 2013. We also have a classification system, shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10. Sensory processing disorder categories and subtypes (Miller et al., 2007).

Sensory modulation disorder (SMD) is a US term, whereas, in Canada, we call it sensory processing differences. This includes sensory over-responsivity, sensory under-responsivity, and sensory seeking. I am going to talk only about sensory modulation in this course. There are also sensory-based motor differences and sensory discrimination disorders.

A very simplistic way of looking at things is that humans are complex, and all our sensory systems interact. The research shows that 53% of kids who experience sensory processing differences experience more than one SPD type. Thus, it is rare to have a sensory modulation difference as they all tend to interact with each other.

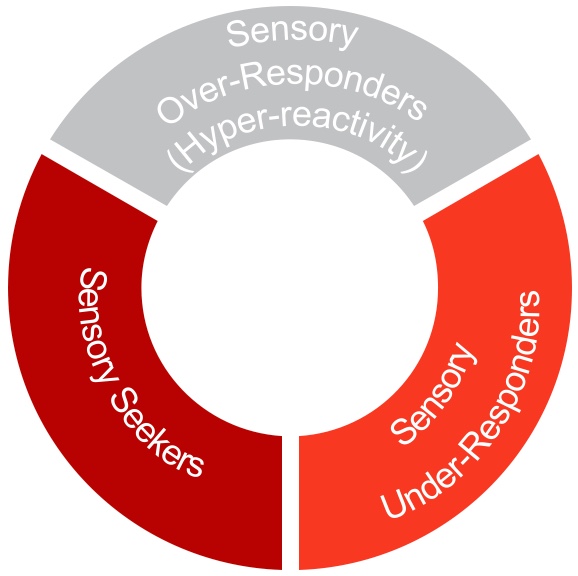

Most Common Sensory Reactivity Profiles: Included Under Sensory Modulation Disorder (SMD)

The most common sensory reactivity profiles under SMD or sensory reactivity are shown in Figure 11. They are sensory over-responders, sensory under-responders, and sensory seekers.

Figure 11. Common sensory reactivity profiles.

When we look at sensory processing differences, sensory modulation is what we see 80% of the time in a clinic or school. Understanding sensory modulation is key in how we are then able to determine what interventions we put into our programs.

Sensory Over-Responders- SOR (Hyper-reactivity)

- Over-reaction to sensations

- Person will try to move away or block the sensory input (particularly during self-care tasks)

- Person may react ‘aggressively’ or ‘controlling’ when overwhelmed by sensory stimulation

- Very cautious, fearful, upset by changes in routine & ++challenges with transitions

- Hypervigilant, anxious

- May shut down

- Thrives with predictable routines

- Things that can be hard for autistic/sensory people at school::

- Crowded corridors

- Loud noises: Fire alarm, school bell

- Lunchtimes that feel chaotic

- Change in teachers and seating plans

- Busy bright display boards

- Sports changing rooms' smells

Adapted from @21andsensory x BBC Bitesize

These individuals overreact to sensations. The person will try to move away or block the sensory input. You often see sensory over-responsiveness in self-care occupations, like toothbrushing, showering, bathing, changing, taking clothes off at school, putting them back on, boots, and all that stuff. If you see this behavior during ADLs, you are thinking about modulation.

The person may react aggressively or controlling when overwhelmed by sensory stimulation, which makes sense. A sensory over-responder feels unsafe in the world. They are cautious, fearful, and upset by changes in their routine. There are many challenges with transitions. When the world feels unsafe, the person will demand predictability so they can manage. An over-responder also tends to be hyper-vigilant and anxious.

Emily from 21andsensory says, "Things that can be hard for autistic or sensory people at school are the corridors, loud noises, the fire alarm, the school bell, and lunchtimes that feel chaotic. You see a lot of behaviors around lunchtime or recess because there is not that predictability." Again, something that is not predictable increases stress, which we all know, is when we become dysregulated. Other areas of stress are changing teachers and seating plans, busy or bright display boards, sports changing room smells, and so on.

Here is some research in this area:

- Correlations with ASD (Bart et al., 2017; Carpenter et al., 2019; Syu & Lin, 2018), ADHD (Lane & Reynolds, 2019; Lane et al., 2012), anxiety (Green & Ben-Sasson, 2010, Lane et al., 2012), GI issues (Mazurek et al., 2013), picky eating (Cermak et al., 2010), sleep problems (Mazurek & Petroski, 2015), self-injurious behaviors (SIBs) (Duerden et al., 2012), increased parental stress & challenges in participating in everyday activities (Reynolds & Lane, 2008)

- Families of children with SOR exhibit more impairments than families of children with psychiatric diagnoses (Ben-Sasson et al., 2009)

What is interesting is that most researchers say the evidence is robust. We know sensory over-responsivity correlates with autism, ADHD, anxiety, gastrointestinal issues, picky eating, and sleep problems. It also states that atypical sensory processing is a key indicator of self-injurious behaviors. There is also increased parental stress and challenges in participating in everyday life. Sensory processing affects not only your emotions but also affects your behavior. If we are able to help that person regulate their sensory systems, then we can make an impact on that person's emotional regulation and behavior.

I also want to drive the point home that SOR causes real distress for families. Families with children with SOR exhibit more impairments than families of children with psychiatric diagnoses.

Shifting Practice: Learning from the Lived Experience SOR=Pain

Another understanding that we have now from the lived experience of autistic people is that sensory over-responsivity equals pain. Here are some quotes from autistic adults.

- “Strip lighting... that can immediately… hurt a lot”

- “If textures (of food) were mixed…the sensation makes me want to feel physically ill”

- “People brushing past me.. It’s like pain mixed with panic… and I can become quite aggravated because of it”

- “Bad smells feel quite painful”

- “Loud noise can bother me…. And it can feel painful”

- “Every time I am touched it hurts; it feels like fire running through my body”

(Robertson & Simmons, 2015)

Before this research came out in 2013, I thought that the child was being dramatic when they would say something like, "When the teacher is writing on the blackboard, it feels like a thousand knives going into my body." That is how he felt, and I did not validate that. I made my assumptions because I do not feel that therefore that person cannot feel it. There is a shift in practice where we are validating people's experiences of sensory pain.

You see how then it becomes important for us to try then to adapt the environment to mitigate that sensory pain. As occupational therapists, we need to engage in sensory advocacy.

- “In fact, sensory sensitivities… may predispose autistic people to chronic pain.” (Failla et al., 2021, as cited in Jeffrey-Wilenski, 2021)

Sensory sensitivities may predispose autistic people to chronic pain. Think about all of the strategies that we implement for people who experience chronic pain, like energy conservation and pacing. This is also relevant to people who experience sensory processing differences. And like I said, all of this diagnosis. I like to talk about what a person does to re-energize, like going for a walk for 10 minutes, looking at a tree, or experiencing nature. Replenishing is important for chronic pain.

Sensory Inputs Add Up Throughout The Day --> Dysregulation

- Allodynia: perceiving non-painful sensations as irritating, non-pleasant, or painful (Bar-Shalita et al., 2019)

- These sensations are higher in intensity & linger for a longer duration after the stimulus is over (Bar-Shalita et al., 2009, 2012; Weismman-Fogel et al., 2018)

- Explains the accumulation of aversive sensations experienced by individuals with SOR (Kinnealey et al., 2015)

Another way to view self-regulation or dysregulation is the concept of allodynia, which is perceiving non-painful sensations. In a neurotypical person, this may be a sensation that is irritating, non-pleasant, and even painful. We also know from research from Dr. Bar-Shalita from Israel that these sensations are higher in intensity and linger for a longer duration, even after the stimulus is over. It explains the accumulation of aversive sensations experienced by individuals with SOR.

I like this volcano graphic in Figure 12.

Figure 12. Volcano infographic showing the precursors to a sensory overload or meltdown under the surface. (Adapted with permission from @theotbutterfly).

Think of the school-aged child who wakes up and feels that their clothing is itchy and painful. They then go into the school, and there is a loud music class, which is also perceived as pain. They get another hit of pain that lingers. Someone then bumps into them. You can imagine, after all of that accumulates, there may be meltdown behavior. You may ask if they want a green or a pink cup, and you get this meltdown behavior. Occupational therapy can prevent the accumulation of this aversive sensory input. I hope this makes sense to you.

One person has commented, "I like to use the example of shaking a soda can and then opening it up." I love that. Painful, sensory experiences add up until the person cannot manage that anymore. They are not going to be successful with tasks in this state.

We need to determine the triggers or the antecedents. I have already given you some ideas. It could be sensory processing differences.

Sensory Under-Responders (SUR)

“…muted or slowed responses to sensory experiences often with an apparent lack of awareness, lethargy &/or indifference, or diminished responsivity” (Mulligan et al., 2021)

- Does not react to sensory input they should be reacting to

- Unaware of body sensations

- Passive behaviors: lies down on the floor, leans on others or furniture

- Does not notice others in the room

- Slow to respond, quiet, withdrawn, uninterested in exploring games

- Becomes tired quickly

- May lack awareness of danger (heights, crossing streets, etc.)

- Thrives with explicit & multisensory teaching

Let's now talk about the sensory under-responders. They do not react to sensory input in the way they should be reacting to it. They are unaware of body sensations and engage in passive behaviors, like lying on the floor, leaning on others, pushing against people, and not noticing others in the room. They are slow to respond, quiet, and withdrawn. They also become tired very quickly.

From the outside it looks like they are coping, but they could be in sympathetic overdrive. As such, they are not responding to sensory input in the way that they want or need to. They thrive with explicit teaching.

Sensory Seekers

- Seeks constant stimulation

- Likes crashing, bumping, jumping, roughhousing

- Constantly touches objects

- Licks/mouths/chews on objects

- Takes excessive risks during play or when engaged in physical activities

- Thrives in active/multisensory environments & when given access to sensory tools

Sensory seekers seek constant stimulation. They like to crush, bump, jump, and seek high, deep tactile experiences like crashing against the wall. They like to touch, lick, mouth, and chew objects They take excessive risks during play or when engaged in physical activities.

Sensory seekers thrive in active multi-sensory environments and when given access to sensory tools.

I see myself as a sensory seeker. Even when presenting, I use my hands a lot. In fact, if I were to sit on my hands, I am not sure I could talk very well. I also have a chair that allows me to move because movement enables me to use my language, and hopefully, not my first language, Spanish. We need to recognize ourselves to shift into a stance of compassion with our clients.

Neuroscience & Sensory Seeking Behaviors

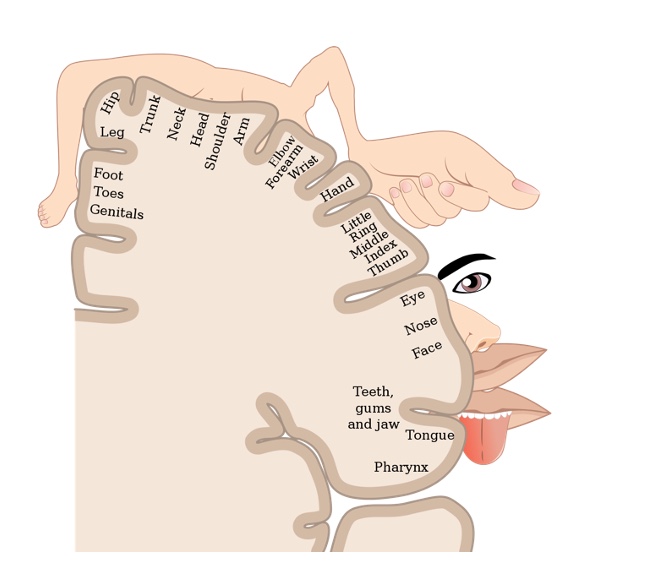

- Homunculus: Visual representation of the brain dedicated to sensory systems for parts of the body

- Greatest density of tactile receptors in hand, mouth & genitals

- Sensory-seeking activities will usually be focused on the ‘bigger’ parts of the body

I want you to remember the connection between neuroscience and sensory-seeking behaviors. Back in our school days, we learned about the homunculus, which is the visual representation of the brain dedicated to sensory systems for parts of the body (Figure 13).

Figure 13. Sensory homunculus.

What we see from this visual of our brain is that there is the greatest density of tactile receptors in the hand, mouth, and genitals. This is where most sensory-seeking activities will be focused. When I work with parents, I show them this visual. For example, if a two-year-old is putting their hands in their pants, we can explain the neuroscience of this so they can put the shame aside and figure out how to support the child.

Sensory Processing Differences and Preferences

“When a little girl’s giggles color the walls and ceilings with rainbow foam when she is amused by my echolalia….. I feel blessed for being what I am.” (Mukhopadhyay, 2008)

- “When a little girl’s giggles color the walls and ceilings with rainbow foam when she is amused by my echolalia….. I feel blessed for being what I am.” (Mukhopadhyay, 2008)

I talk about sensory processing differences with clients but keep in mind that sensory processing differences are not always synonymous with challenges. They may be a source of unique gifts and quality of life. As OTs, we must consider how a sensory preference can help somebody maintain regulation.

In addition to sensory processing differences, I ask about sensory preferences. Is there a particular toy that that child likes that they can hug right before they go to school? Is there a particular smell or clothing that is regulating them?

Many sensory tools can help with regulation. In the example above, a non-speaking autistic adult conveys, “When a little girl’s giggles color the walls and ceilings with rainbow foam when she is amused by my echolalia….. I feel blessed for being what I am.” (Mukhopadhyay, 2008).

A sensory behavior may be looking at the light through their hands. It may be egosyntonic quality to them, or they feel good. It is hard to stop things that feel good. Instead, when you see a behavior, you can ask yourself, "Is it causing stress?" If it is not, should we manage that behavior?

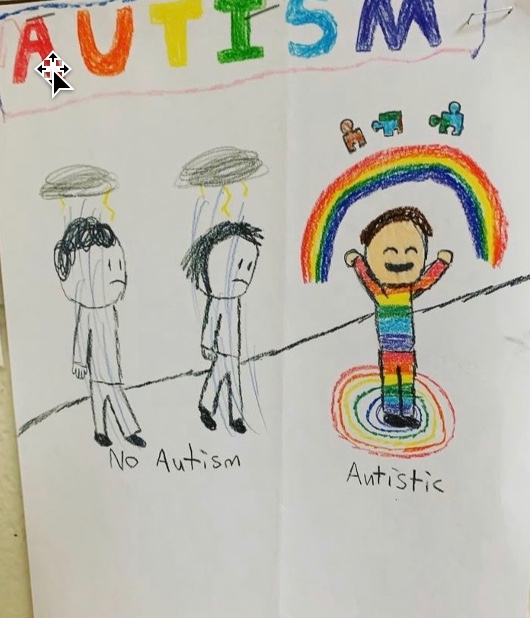

I love this drawing from an autistic student. It is their perception of their authentic autistic self (Figure 14).

Figure 14. Drawing of a child with autism comparing those with autism and those without. Shared with permission from Ms. Alyssa Willoughby, OCT, M.Ed.

Sensory-Based Motor Disorder (SBMD)

- Postural disorder: Low muscle tone, immature balance reactions, inefficient postural adjustments & poor bilateral integration

- Dyspraxia: Difficulties with ideation, sequencing, motor planning, and/or execution (fine, gross & oral motor planning problems)

- Delays in attaining motor milestones, clumsy, awkward & accident prone

- Implicated in motor speech à challenges in communication because of motor speech

There is some new research about sensory-based motor disorders; however, I will only discuss dyspraxia. Dyspraxia is difficulty with ideation sequencing and motor planning. Autistic individuals may have difficulty with motor functioning for speech. For example, a person may cognitively have lost the ability to say what they want to say. We need to revisit the concept of competence because we do not know if the person is locked in within a body they cannot control.

As OTPs, we do this well with a person with Parkinson's disease. We recognize that certain motor mannerisms may not be in their control. However, we do not always extend the same recognition for conditions such as autism. Think about the child who might mean to shut the door lightly, but it comes out as a slam because they cannot control their proprioceptive system. Or, we may see a child who means to whisper, but it comes out as a yell. For dyspraxia, it may be a child who wants to vocalize, but they cannot control that motor part of themselves, and we misinterpret that as willful misbehavior.

Shifting Practice: Learning from Autistic Voices: Recognizing the Gap Between Intention & Action in Autism

- “When I was growing up, speaking was so frustrating. I could see the words in my brain, but then I realized that making my mouth move (was needed) to get those letters to come alive, they died as soon as they were born. What made me feel angry was to know that I knew exactly what I was to say, and my brain was retreating in defeat.” ~Jamie Burke (Biklen and Attfield, 2005)

(Phung, Penner, Pirlot, & Welch, 2021)

Here is a quote from an autistic adult. If you want to learn more about our understanding of motor differences in conditions like autism, you can read that research paper.

Shifting Practice: Adopting Neurodiversity-Affirming & Strengths-Based Approaches

- Our call to action is to address distress, not differences

Let's now talk about some key strategies under each category.

Key BEST Strategies for Self-Regulation

- B is for Body

- E is for Emotional

- S is for Sensory

- T is for Thinking

- Through play with children

- Change the rules!

- Foster relationships first

- Honor consent

- Proactive solutions model

My model is based on evidence-based practices. I call it BEST because play is the occupation of children and how they learn best. I also talk a lot about fostering relationships first for co-regulation. You want to think about how to use yourself to regulate another person.

We honor consent, meaning we do not impose any of these interventions. If the person does not want to participate, we honor that. This is a proactive solutions model where we are becoming preventionists as opposed to interventionists. We want to do everything possible to prevent behaviors as opposed to intervening after the behavior has happened. After the behavior has occurred, we will be ineffective because the person is now in sympathetic overdrive with no executive functioning.

When using new ways of thinking or new models, we need to change the rules. If I am talking to teachers, I tell them we now have more research about neurobiology so it behooves us to do better.

First & Foremost: See Behaviors --> DIG DEEPER

- “There are no bizarre behaviors, more accurately, there are human responses that are not fully understood or appreciated” –Carol Gray (The New Social Story Book, 2000)

- “Kids (or our clients) do well if they can…if they can’t, we adults (or OTs) need to figure out what is getting in the way so we can help”—Dr. Ross Greene (The Explosive Child, 1999)

I love these two quotes, as they are our manifesto. We may not understand what a behavior means, but we can try to find the antecedents, or what is causing the behavior. One of my client's mom said, "Moira, I know something's happening. He might be in pain." Her son is non-speaking and not able to tell her. "I know something is distressing him, but I do not know what that is." This is a shift as she did not say, "He's misbehaving, or engaging in aggressive behaviors." Instead, she felt he was dysregulated or in pain and wanted to know why. We recognize behaviors as unmet needs.

You will notice in the second quote that it is not kids who do well if they want, but it is kids do well if they can.

OT Practice Guidelines: Interventions that Address Sensory Processing Differences (Reynolds et al., 2017; Watling et al., 2018)

1)Environmental supports & adaptations:

- Changes made to the physical, social, temporal & virtual environment: altered seating, compression clothing, fidget toys, weighted tools, ear defenders, social stories, video modeling, dental environment modifications & sensory diets

2)Caregiver-focused interventions

- Family & teacher education

- Coaching within a strengths-based approach

3)Person-focused/Therapist-led interventions

- ASI® & Sensory-Based Interventions (SBIs)

- Cognitive approaches (e.g., CO-OP, mindfulness, MCBT), behavioral approaches, biomechanical approaches & skill building

- Sensory Strategies ARE Mental Health Strategies!

The BEST framework is based on OT Practice Guidelines, that address sensory processing differences. In this paper, they talk about environmental supports and adaptations. As OTPs, we change the physical, social, temporal, and virtual environments, such as altered seating, compression clothing, fidget tools (as opposed to toys), weighted tools, ear defenders, social stories, and video modeling. We even have amazing research from Dr. Karen Semark on dental environments that support regulation.

There are also caregiver-focused interventions. This is family and teacher education and coaching within a strengths-based approach.

Lastly, they discuss person-focused or therapist-led interventions. There are Ayres Sensory Integration® (ASI) and Sensory-Based Interventions (SBIs). ASI is its own thing, and there are fidelity measures for that. It is very specific, and you have to have lots of training to be able to do that well.

What I am talking about in the BEST Model are sensory-based interventions. These are interventions that are therapist-led and co-created with parents and teachers. Interestingly, these two papers include cognitive approaches as part of person-focus or therapist-led interventions, including the Cognitive Orientation to daily Occupational Performance (CO-OP), mindfulness, and modified cognitive-behavioral therapy (MCBT). They also talk about behavioral and biomechanical approaches and skill building.

Sensory-Based Interventions (SBIs)(Case-Smith et al., 2015; Watling et al., 2011)

- Occupational therapists who use a Sensory Integration (OT-SI) frame of reference but are not providing ASI®

- Therapists driven with a high emphasis on co-creating with clients

- Passive stimulation and/or ‘active’ enhanced sensory input

- Targeted sensory input to support sensory processing & self-regulation

- Usually targets one sensory system at a time

- May be an environmental modification

- May be incorporated within a sensory diet approach/sensory lifestyle/sensory supports plan

Again, we are talking about sensory-based interventions, and these are OTPs who use a sensory integration frame of reference but are not providing ASI. SBI interventions are therapists driven with a high emphasis on co-creating with clients, teachers, and parents. It is usually a passive stimulation or active enhanced sensory input.

For passive stimulation, I may be talking about massage, as an example. Massage is deep pressure input. When talking about an active or enhanced sensory input, I am talking about a child engaging in a movement-based intervention. It is a targeted sensory input to support sensory processing and self-regulation, usually targeting one sensory system at a time.

SBIs can also be environmental modification, like a sensory diet approach. Most are not using that term anymore, but I like to use sensory diet because if you change the wording too much, then the research loses it. Other terms include sensory lifestyle or sensory supports plan, which I also like a lot.

BEST: B is for Body

- B is for Body

- E is for Emotional

- S is for Sensory

- T is for Thinking

- Using the body to calm the mind because there is no ‘wise mind’ in times of crisis or when experiencing distress

Leverage the Power Senses! Vestibular, Proprioceptive & Tactile Systems

- The Effect of Exercise on Psychological Wellbeing

- Growth

- Self Acceptance

- Mood

- Friendship

- Cognition

- Depression

- Attitude

- Mastery

- Anxiety

Movement increases blood flow to the brain, promoting attention, mental clarity & memory. Movement WILL assist children to focus. Studies support this at the neurological level by the viewing of activity of the brain & academic outcome measures (Hillman et al., 2014).

Adapted from @BELIEVEPHQ

One key strategy for regulation is using the power senses: vestibular, proprioceptive, and tactile systems. As OTPs, we all know the positive effects of exercise on psychological well-being. Research tells us that if you move more, you are going to be a happier individual. There is also research on movement linked to growth, self-acceptance, positive mood, improvements in friendships, cognition, attitude, a sense of mastery, and decreased depression and anxiety. I would argue many of us do things like going to the gym to help us manage our psychological well-being, especially around anxiety.

How do we bring this into the school system? I like to talk to teachers about the research in their literature that says that movement increases blood flow to the brain. It promotes attention, mental clarity, and memory, and movement will assist children to focus. Studies support this at the neurological level by the viewing activity of the brain and academic outcome measures.

The Evidence Supporting Movement Breaks

- Research on movement breaks (‘brain breaks’ or ‘sensory breaks’) provide support for improved regulation & participation in meaningful daily occupations

(Anderson, 2016; Becker et al., 2014; Daly-Smith et al., 2018; Ma et al., 2015; Wild & Steeley, 2018)

- What does a movement break look like?

- same time every day

- student-led

- GoNoodle

- Bizzybreaks: https://irishheart.ie/schools/primary-schools/bizzy-breaks/#:~:text=Bizzy Breaks is a collection, have an activity for you

We all know we should be moving, but what is doable in the classroom? We can recommend two or three movement breaks, for example. We can then add power to those to make them either vestibular, proprioceptive, or something that has tactile input. In terms of the vestibular system, these may be outside the school.

Research on movement or brain breaks shows they improve regulation and participation in meaningful activities. I can think of many examples from my teachers. One example is GoNoodle, including music and dancing. I have a teacher who has different sections around their classroom. They took pictures of each student doing different activities like wall pushes for deep pressure.

Deep pressure has a regulatory effect, taking only five seconds. It is short-duration and high-intensity. We do not want to make it too long because it becomes work. When something becomes work, the kids do not want to do it. Five seconds is doable, and the teacher can easily incorporate them into the routine.

I also like busy breaks, like dancing, crab, yoga, and power poses. There is lots of research on the regulation of kids using yoga. I had one teacher, who understood the importance of research and mindfulness interventions, and asked if she could do yoga on Thursdays instead of Mondays. On Monday, students were still regulated from the weekend, but by Thursday, she was losing her students.

Adaptation is huge. We need to place these sensory-based interventions to get the most benefit.

Other movement ideas include erasing and cleaning the chalkboard and wiping the tables. Another idea generated by the audience is placing their hands on the ground and walking their feet up and down the wall for vestibular and proprioceptive input or planks. Another example is moveable, flexible sitting like a wobble board or a mini trampoline. Again, we do not want more work for the teacher.

Leveraging the Power Senses & Occupational Participation (Bremer, Crozier, & Lloyd, 2016)

- Incorporate the power senses/Make it fun!

- Bouncing on a ball

- Bike riding

- Swimming

- Bowling

- Martial arts

- Horseback riding

- Rock climbing

- Yoga and mindfulness

- Running

- Stretching

When talking to families, you want to think about ideas for home or leisure activities. For example, bowling involves deep pressure when carrying and swinging a ball. Horseback riding has good research around it. Swimming provides water pressure and is a life skill. There is a lot of great research on psychological well-being and regulation using mindfulness-type interventions. Running is another great activity. We want to keep all activities fun and doable in the classroom and at home.

'Outside-the-Box’ Proprioceptive Input (Heavy Work Activities)

- Carrying, Pulling, Pushing, Dragging, Squeezing & Lifting Activities

- Chewing: gum, chewlery, or crunchy snacks

- Wearing a heavier backpack or clothing

- Tug-of-war

- ‘Pushing’ the wall away

- Climbing, jumping & hanging activities

- Household chores

- Bouncing on a ball

- Digging in the dirt, snow shoveling

- Chair push-ups

- How can I do “heavy work” with my kids?

- Go for a bike ride

- Put away groceries

- Play tug of war

- Climb at the park

- Do yoga

- Animal walking

- Pull a wagon

- Water plants

- Monkey bars

- Stomp your feet

- Try to “push over: the wall

- Push your hands together to “squish a bug”

- Dig in sand/dirt

Adapted from @otinspired

Out-of-the-box proprioceptive activities include carrying, pulling, pushing, dragging, squeezing, or lifting. We must engage our clients, especially as some are not easily engaged. I worked with a teacher who was creative and allowed chewing gum in the classroom. Then, when the kids were going to recess, they had to put their gum on a square. Tug of war is a good one. They can use a towel and pull with a partner. We also discussed pushing the wall away.

At home, they could do household chores, bounce on a ball, go for a bike ride, or put away the groceries. I like to ask families what they are doing already. I will have them tell me about their daily activities. You want to discover things they are doing that they can adjust to add proprioceptive input.

Other easy ideas are putting hands together to "squish a bug," pulling fingers apart, and pushing their head down.

‘Outside-the-Box’ Deep Touch Pressure Tactile Input

- Tight hugs or self-hugs

- Massage

- ‘Burrito’ blanket roll up

- Spandex clothing (smaller swimming shirts, tights, compression sportswear, etc.)

- Sandwich game (pressure placed with a ball)

- Squishing with pillows

- Pushing hands together/pulling fingers apart

- ‘Crashing’ onto a mattress

- Fidget/Attention/Regulation tools

- Sitting in a bean bag chair

- ”It’s not childish to use fidget toys...there is no age limit on sensory needs...If it works for you it works! Adapted from @recoverydoodles

Other deep touch ideas are tight hugs, self-hugs, and massage. There is a lot of research on massage being an effective sensory-based intervention. Massage by a parent can help a child regulate. In fact, it may be of value for them to learn some massage techniques from a massage therapist. They could provide massage input right before a challenging transition, like going to school, for example.

I like the input provided from tighter clothing. I am transparent in my work with parents, and I say, "I am not sure if this is going to work. I am giving you my thoughts on this. What do you think?" They can then try something and let you know in a few weeks. An example is a smaller swimming shirt or tight compression shirt.

The sandwich game is when the child is in a beanbag chair, for example, and you ask them, "Would you like some mayonnaise on your sandwich?" If they say, "Yes," you would use little pillows to provide input. Parents love this one. Then they may say, "I want ketchup," and you would provide another deep pressure type input. I like to use a beanbag chair because you can fold it and give the squeezes. Teachers may not want to touch the child, so they may be able to use something like a ball between them to provide feedback.

I would love to know on the chat what has worked with regulation with your clients without needing equipment. Some responses I see are chair pushups, wheelbarrow walking, joint compression, vacuuming, and velcro strips under chairs. I would love to know more about this one.

We now know that it is not childish to use fidget tools or toys, as there is no age limit to sensory needs. If it works for you, it works. I used to be uncomfortable around providing those sensory tools to adults. However, I now know that they use those sensory tools for regulation. Again, this is another shift in practice.

Another thing that is mainstream is wearing compression garments. Many athletes wear these garments, and many things can be found in regular stores. I live in Canada, and many hockey players wear compression clothing.

Popping bubble wrap is a fun way to distress. I love it, and it does have that deep-pressure input.

- “When a kid loses it and is in the red brain, the things that will bring them back to blue brain are the same things that would have soothed them in infancy.” Dr. Stuart Shanker

When you do not know what to do, I want you to remember this quote from Dr. Stuart Shanker. When I am working with a person who is showing a lot of interfering behaviors, I ask the parent, "When they were babies, what used to help them?" One mom said, "We tried so many things, but nothing worked." She tried rocking forward and back like she did when he was an infant in a gliding chair. The back-and-forth movement was so regulating for this person that the behaviors decreased significantly.

BEST: E is for Emotional

- B is for Body

- E is for Emotional

- S is for Sensory

- T is for Thinking

The Power of Co-Regulation

- In order for your child to be calm, YOU need to be calm

- We cannot separate the well-being of the child from the well-being of their caregivers

- Through co-regulation, we connect with others & create a shared sense of safety

- ”Our most important sensory approach tool is the therapeutic use of self.” Tina Champagne, OTD, OTR/L, FAOTA

One strategy that I want you to think about is the power of co-regulation. In order for your child to be calm, you need to be calm. I want to bring this back as a therapist. In order for your student to be calm, you, as a therapist, need to be calm. There is the recognition that things can improve not so much with each other but through each other.

Your stress as a therapist will influence the stress of the child. If you are both escalating, it is not going to go well. Very often, all you can control is you. Behaviors happen, and the one thing you can control is how you choose to react to that behavior.

Co-regulation in Action

- A baby is born with only between 20-25% of their adult brain. In order for them to self-regulate, you need to lend them your frontal lobe, ‘thinking brain’ (Shanker, 2016).

Through co-regulation, we connect with others and create a shared sense of safety. Babies need you to regulate them. When the parents pick the infant up, and they calm down, that is co-regulation. In order for them to self-regulate, you need to lend them your frontal lobe or thinking brain. We recognize that babies need us and then forget about that. As the child gets older, we want them to self-regulate. When actually, none of us self-regulate. For example, I drink coffee, and it is a tool for self-regulation. I also go to the gym to regulate myself.

There are many examples of co-regulation. Another example is pets. I like to hug my dog because it feels good.

Self-regulation is a misnomer. We tend to control our behaviors cognitively, but in terms of regulation, we use something or someone to help us regulate.

Am I Co-escalating Or Co-regulating? @kwiens62

However you feel, your kids feel it too. Our brains resonate with each other. Take good care of yourself, so you can spread calm instead of fear. Adapted from @wildpeace.forparents

To promote flexibility, we need to model flexibility

However you feel, your kids or clients feel it too. Our brains resonate with each other. It is important to take good care of yourself, so you can spread calm instead of fear.

I ask myself the question, "Am I co-escalating or co-regulating" all the time. It is very easy to co-escalate with a person that is yelling at you. I fail at this on a daily basis as a parent. I lose my cool and then repair things by apologizing to my child that I should not have acted like a 10-year-old and so on.

It is a huge skill to be able to regulate yourself so you can regulate another person as they are escalating their behavior. Often, we have a pattern of rupture and repair. I read some research that says as long as you spend 30% of your time in repair, then you are okay. Thus, the majority of your time as parenting is in this rupture phase, which was oddly calming to me.

Again, be cognizant of the things that you can do because sometimes that is all we can do to regulate ourselves.

Co-regulation Strategies

- Preparation prior to sessions, transitions, etc.

- Be mindful of how you are viewing the behavior

- Allow access to own comfort items & calming sensory tools

- Awareness of own sensory preferences

- Use of positive feedback

- Decreasing social demands at beginning of a session

- Tone of voice (low & slow)

- Changing pitch & intonation

- Provide instructions using rhythm/numbers (time-limited)

- Predictability/Transition songs

- Use of gestures/body position (below or at eye level of the person)

- Use of humor, novelty & surprise

- Modifying instructions

- Modeling deep breathing

- Managing physical proximity

Let me give you some co-regulation ideas. Preparation and predictability prior to sessions and transitions increase your sense of self and safety, as I talked about before. Be mindful of how you view the behavior. If you see that behavior as my child or student is doing that to upset me on purpose, then your reaction will be punitive. Dr. Roth Green says our explanation of the behavior guides our intervention. That statement has always stuck with me. Do you see it as misbehavior or as a stress behavior?

It is crucial to allow access to their comfort items and calming sensory tools.

We also want to know what the child gravitates toward when they are happy. Additionally, we want to know what the person does when they are not kicking, biting, or screaming because no problem is there 100% of the time. There must be moments in that person's life when they are happy and regulated. It is interesting what you find out because most families are not expecting that question. Often, they have to think about it.

For one of my clients, all I got was a list of all the behaviors. As therapists, let's recognize the stress we get from seeing those long lists. When I asked the caregiver what he liked when not engaged in the negative behaviors, she said, "He likes legos and can work on the most intricate Lego structures for hours." Right then, I had my intervention. For instance, this youth was not showering and would not transition into the bathroom. We talked a lot about sensory supports and decided to put a new Lego set in his line of vision on the way to the bathroom. This brought him joy and helped him make the transition.

We want to ask about their sensory preferences. Asking what happens when they are not engaging in the behavior will give you many ideas.

We also want to be aware of our sensory preferences. What about that child is triggering you? Why do you tend to gravitate toward certain children and not others? What is the transference, or what is that reminding you of? It is natural to react as we all have those thoughts. However, we need to reflect on that to determine what is underlying that.

Use positive feedback and decrease social demands at the beginning. For example, we may say, "Johnny, how are you today?" This is already a stress because they need to answer your question and make a social overture to you. Instead, you could lead with, "Johnny, I love your shoes." I am making a statement and not expecting a social response. I acknowledge the child, and then I move on.

The tone of voice is a huge co-regulation strategy. I am a loud person which can be dysregulating to a child, and I am cognizant of that. I must slow my movement and talk. Whispering and singing can work. Songs for transitions are huge, and because of the rhythmicity of music, it also helps with movement. What other ideas you you have? Some responses from the chat include: changing pitch and intonation, providing instructions using rhythm or numbers, predictability, gestures, body position, and humor. If things are escalating, the one thing you can do is make the child laugh. Laughing releases feel-good hormones that distract from escalation. If I am losing a person, I like to get silly. I may put something on my head and sneeze, so it falls off. This moment of laughter may be enough to move away from the behavior. We can do something like this instead of trying to reason via talking, such as "I see that you're becoming dysregulated."

We can also modify our instructions or model deep breathing. Sometimes deep breathing works, and other times it does not.

Someone has said in the chat, "I lower my voice to make them increase their focus to hear what I am saying." Other responses include changing the lights, using visual charts for transitions, using a positive affect, decreasing language, using facial expressions, and getting down on the kids' levels. These are all great suggestions.

BEST: S is for Sensory

- B is for Body

- E is for Emotional

- S is for Sensory

- T is for Thinking

Let's talk about sensory strategies.

Sensory Strategies & Sensory Safe Environments

Person-Environment-Occupation (PEO) Fit

- Greatest concern for autistic high school students is not academic achievement

- Problematic social interactions

- Negative social comparison

- Unpredictability of environment

- Lack of fit

(Reed et al., 2012)

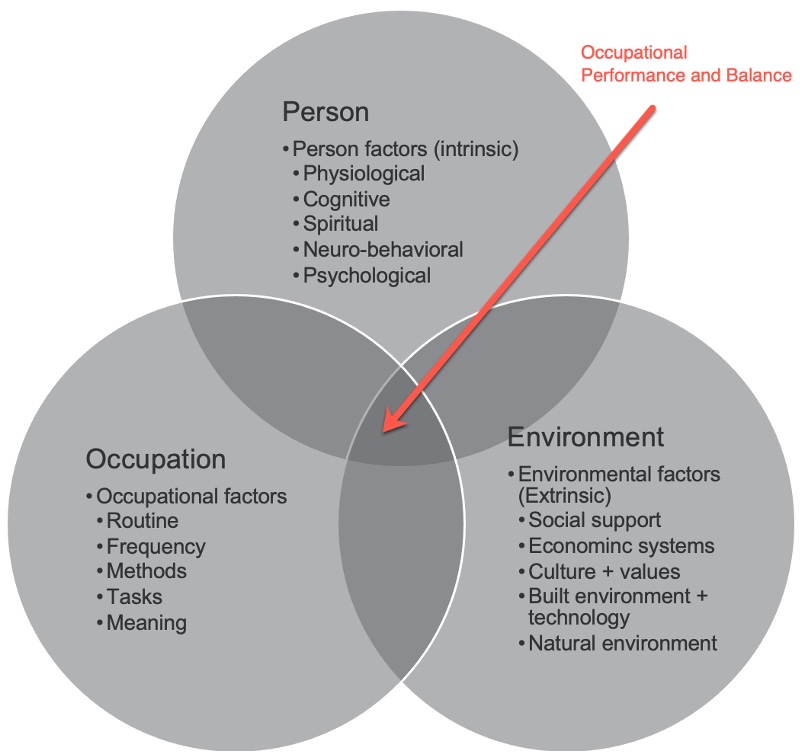

Figure 15 is what we think about the PEO model.

Figure 15. PEO model adapted from @alaskah_ot.

What we recognize now is that the greatest concern for autistic students is not academic achievement. It is more about the unpredictability of the environment and the lack of fit. We are now shifting from trying to change the person to adapting the environment. I would argue that nobody likes change, and we do a lot better when we change our environment to suit us.

For example, I do not like to drive and only do it out of necessity. I have adapted my life, so I do not have to drive. I live in a city, near public transit and a grocery store. I do not have to drive most of the time, but I have adapted my environment to enable me not to do that.

We live our life based on our strengths and not our remediated weaknesses.

Sensory Strategies: Adapt the Environment & Create Sensory-Safe Spaces

Environmental adaptations have a lot of impact on self-regulation and behavior. There is wonderful equipment out there accessible to OTs. I like to use as little equipment as possible because these things tend to get lost. I am a proponent of "less is more". Figure 16 shows some options I like to recommend.

Figure 16. Examples of self-regulation equipment.

I like movable cushions and boards that move side to side and spin. I love beanbag chairs because they provide deep pressure. We also now understand the value of islands of retreat in the classroom, especially for neurodivergent kids. The idea of retreat is replenishing and then coming back into the classroom. I am all about keeping people in the classroom because we want to minimize the number of transitions this person has.

I love the sensory kits to prevent behaviors. It is having something in the classroom that a child and parent have helped set up. The sensory kit could include a drink, snack, sensory tool, or ear defenders. As a teacher or therapist, when you see signs that things are not going well, you can use a sensory kit to help the child regulate.

Creating Sensory Safe Spaces (Letterman, 2020)

I cannot overemphasize the value of sensory safe spaces. Literature about autistic lived experiences reports how much they needed these opportunities for retreat. Figure 17 shows two examples.

Figure 17. Examples of sensory safe spaces.

Adults also need to do something every so often around replenishing. We need to take those retreat minutes to recenter ourselves.

- Adapt the environment

- Lighting

- Visual choice board with calming and alerting activities

- Reduce noise

- Calming and alerting sections

- Sensory bins

- Islands of retreat

- Sensory-friendly breaks

- Flexible & dynamic seating

- Biology Comes First Principle: Is the person hungry, thirsty, or tired?

Here are some other ideas for adapting the environment. We already discussed lights, visual choice boards, noise reduction, and using calming areas in the classroom. The Biology Comes First Principle is looking to see if the child is hungry, thirsty, or tired. For example, if the child did not sleep the night before, they are not going to behave well.

Sleepiness, hunger, and thirst impact our daytime behaviors. None of us do well when sleepy, hungry, or thirsty. When we see behavior, can we then offer a snack or offer a drink?

- What would’ve helped you as an autistic child at school?

- Quiet place to take a break

- Separate test room

- Clear guidance on expectations

- Grace for lateness & attendance

- Space to stim

- Extended test time

- No fluorescent lighting

- Help making friends

- Unscented cleaning products

The above answers are how autistic people answered the question of what helped them at school. The answers include a quiet place to take a break, a separate test room, and clear guidance and expectations. The theme of predictability is big. I do not like set routines, and it is hard for me to be predictable. However, once you have children, you realize how helpful that is to them. As an example, I realize now that my kids were not good sleepers because I had a hard time setting a bedtime routine, as I wanted to be more flexible. I realize now that I needed to consider their needs.

Other ideas for supporting autistic individuals are grace for lateness and attendance and space to stim. We are moving away from interventions that promote the masking of behaviors that are not distressing to self or others. We used to try to get them to stop stimming, and very often, it got worse, or they started stimming another way.

Research now supports neurodiversity-affirming approaches that look different but are not less. If the behavior, like throwing pencils, is not causing distress, do we need to address it? I would argue that even if we do address it, we may fail. We are now recognizing that these behaviors are a need.

Research suggests that self-stimulatory behaviors are ways that neurodivergent people self-regulate. There are many things that I am doing right now to enable me to participate in this webinar today, like moving my seat. When something looks very different, we tend to judge it as not normal or something that is wrong.

Autistic kids often say that fluorescent lights make sounds and hurt. I am a low registration person and do not notice lights at all. Even though I do not understand that, I must put myself in their shoes. We need to validate their sensory experience and advocate for them. Another example is a client having many school behaviors due to new cleaning products. Even though I did not smell anything different, this person did. We were able to switch back due to working as a team to investigate possible causes (like the earlier iceberg metaphor).

Many of my kids regulate with visual information, such as playing with Legos, puzzles, counting, or saying the alphabet letters due to rhythmicity. The cadence of the sound provides a feeling of regulation. I love using rhythmic sounds like clapping hands in a pattern to gain the attention of my younger clients. We naturally use these interventions that are supported in the research. Other options include calming music, a metronome, etc.

Shifting Practice: Co-Creation of Strategies!

- People are experts on their own lives-we need to be curious about their experiences!

- Our role is to support a person (or family)’s understanding of their own sensory needs so they can identify appropriate adaptations & determine what sensory supports might be helpful

- How do we support our clients in self-advocating so that they know what accommodations to ask for?

The co-creation of strategies is a neurodiversity-affirming practice. I now ask many more questions now as opposed to what I used to do, which is to talk non-stop and give recommendations. It is now more 80/20, where I ask my teachers more questions and say, "Would you like me to give you a couple of ideas?" I have been around a long time, and I have learned that the minute you give lots of recommendations, people shut down. They stop listening and are overwhelmed. I think this is what happened with the bedtime with my kids. I felt overwhelmed instead of starting to go upstairs at 7:30 at night. I was sleep deprived, and there was not much blue brain function.

Our role is to support a person's or a family's understanding of their sensory needs so they can identify if appropriate and determine what sensory supports might be helpful.

This is also a shift towards sensory advocacy. We must not only advocate for sensory safety for our clients if that person cannot advocate for themselves but also in helping our neurodivergent clients to understand their sensory profiles and what might help them.

- Don’t tell me I don’t need my headphones.

- Don’t tell me it is not bright.

- Don’t tell me I don’t need my sunglasses.

- So what you want is a client that's like this person in the picture.

- I am autistic. I know my needs.

@theexpertally

Figure 18. Example of a client with autism with headphones and sunglasses.

You want your clients to step into their authentic selves and be able to advocate for what they need for participation.

BEST: T is for Thinking

- B is for Body

- E is for Emotional

- S is for Sensory

- T is for Thinking

The last area is thinking strategies.

Thinking Strategies: Using Visuals

- 9 Reasons to Use Visuals

- Adapted from www.northstarpaths.com

- Visuals are permanent (spoken words disappear

- Visuals allow time for visual processing

- Visuals prepare students for transitions

- Visuals help kids see what you mean

- Visuals help all students

- Visuals help build independence

- Visuals are transferable between environments and people

- Visuals have no attitude (no tone, no frustration, no disapproval)

- Visuals help reduce anxiety

@kwiens62

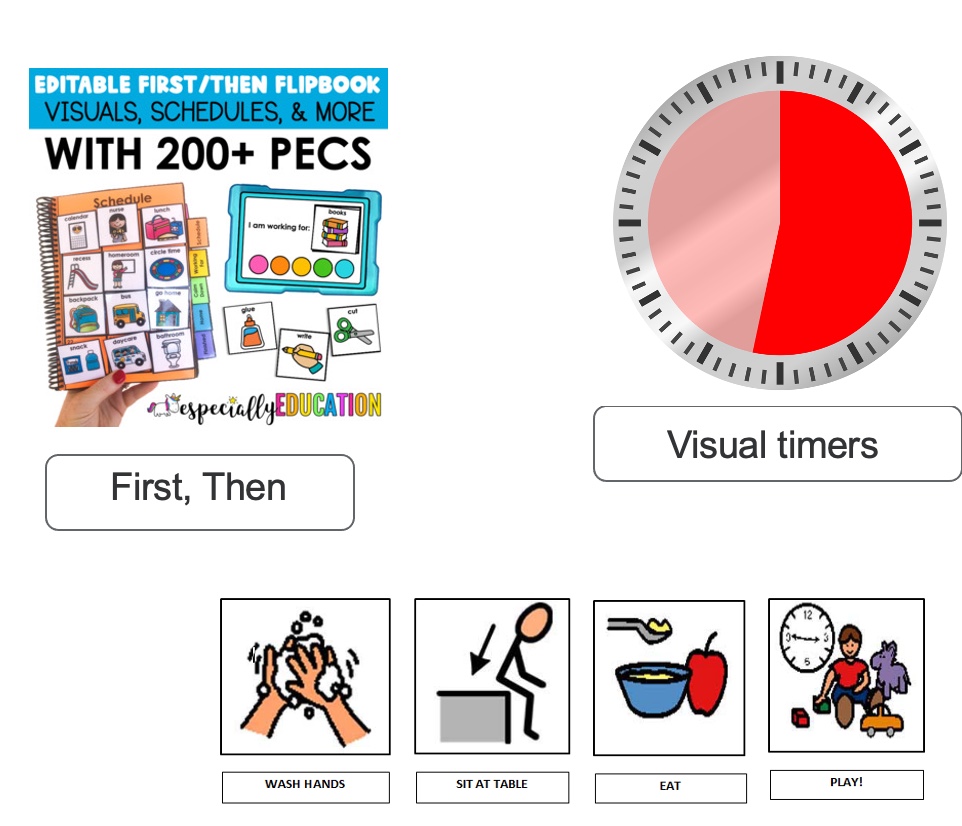

One thinking strategy is the use of visuals. Most clients understand everything we say, but visuals are more about predictability. So I love the use of visuals for making things predictable. An example is in Figure 19.

Figure 19. Example of a visual.

- Apps:

- Tiny Decisions

- Speechify

- Multi-timer

- Jam

- Flora

- Routinery

- Tiimo

- Habitica

@neurodivergent_lou

I also love all the new apps available. The Timo app is very popular in the adult neurodivergent population because you can set up a picture of what you are supposed to be doing. There are also visuals for self-care routines (Figure 20).

Figure 20. Examples of self-care visuals.

Again, predictability is the name of the game here.

I love a visual where once the person has done something, they can hide it. These naturally help the person complete the sequence.

- Keep supports, but fade prompts!

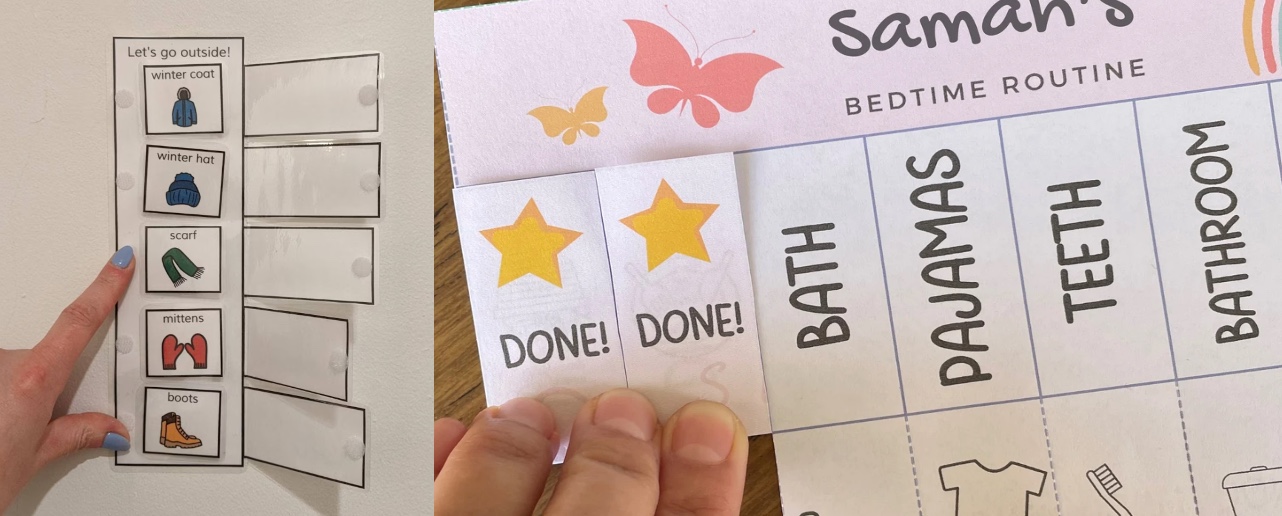

It is important to keep the supports and visuals and fade the prompts. Two more examples of visuals are in Figure 21.

Figure 21. Two more examples of visuals.

Thinking Strategies: Social Stories

- Tool to help an individual learn about specific events/situations that may be more challenging (e.g., transitions & staying calm)

- Personalized story

- Uses positive language

- Read daily & prior to specific situations

- Create your own, websites, apps, books

- Apps

- Social Story Creator and Library

- Autism Emotion

- Pictello

- Kid in Story Book Maker

- Stories2Learn

Social stories are tools to help an individual learn about specific events. It is a personalized story that uses positive language. From experience, they must be read daily as part of a routine. I always practice social stories when that person is regulated. You want to practice sensory-based interventions when that person is happy and will be able to remember. If it makes them feel happy, hopefully, they will use it again.

Thinking Strategies: Example of a Social Story

This video shows an example of a social story.

This is me using the app Social Story Creator & Library.

Thinking Strategies: Another Example of a Social Story

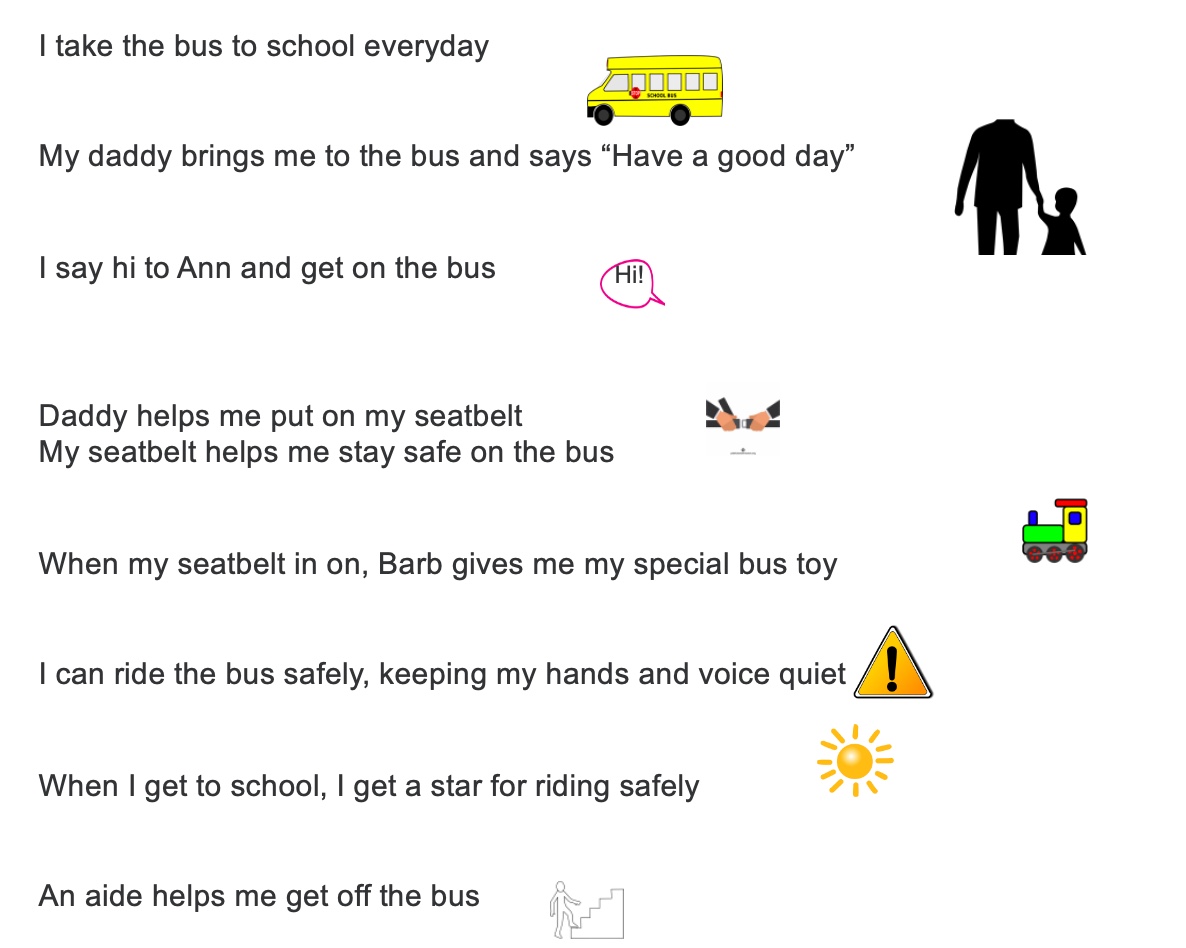

This is a social story from training that we did with bus drivers.

Figure 22. Social story developed for bus drivers.

We use this to help get a child on and off the bus.

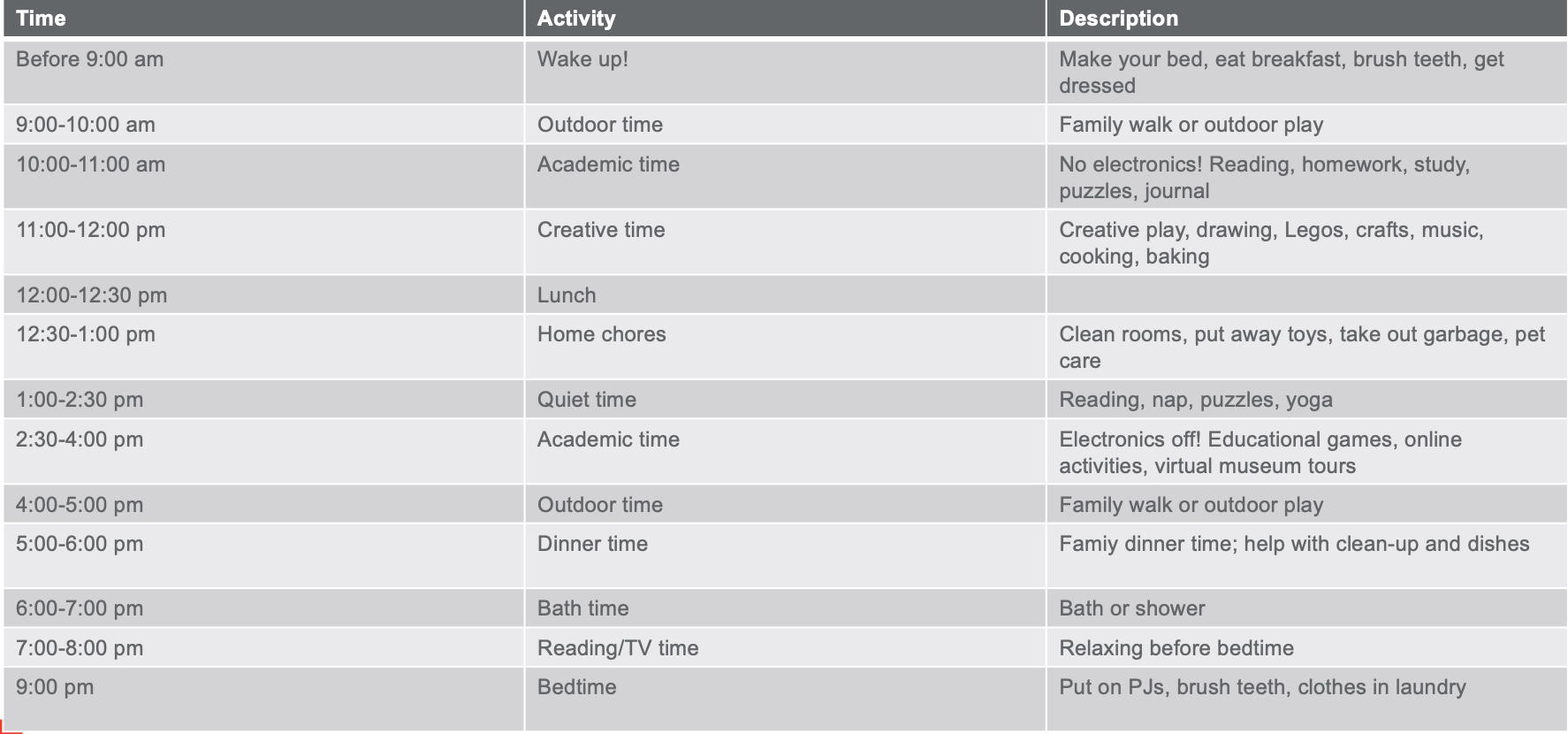

The Power of Predictability in Times Of Anxiety

The pandemic showed us that a lack of predictability could cause anxiety. Human beings do not do well with change, and therefore, we seek predictability.

Figure 23. Example of a schedule. Click here to enlarge the image.

Shifting Practice: Productive Fails are Part of the Process!

- “Growth is a process of experimentation, a series of trials, errors, and occasional victories. The failed experiments are as much a part of the process as the experiments that work.” Dr. Cherie Carter-Scott

Productive fails and trial and error are part of the process. Growth is a process of experimentation, a series of trials and errors, and occasional victories. Failed experiments are as much a part of the process as the experiments that work. Before, I used to get stressed about something not working for me because I thought that said something about me as a therapist. I now think about it in a very neutral way. "That did not work, but what information can I gather from that so that my next suggestion could be more effective?"

Resources

I have some resources here that I have co-created with autistic adults.

- Developed by Elsbeth Dodman (Autistic Self-advocate), Moira Pena (OT), and Fakhri Shafai (PhD, MEd) on behalf of AIDE Canada

- Provides:

- First-person autistic narrative of sensory experiences

- Neuroscience background