Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Cerebral Palsy Review: Clinical Presentation, Evaluation, And Diagnosis, presented by Patti Sharp, OTD, MS, OTR/L, BCP.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to:

- Identify cerebral palsy and the criteria for diagnosis.

- Recognize etiology, risk factors, and early diagnosis warning signs of cerebral palsy.

- List assessment tools used to assist with the diagnosis and classification of cerebral palsy.

Introduction

Thanks for joining me for this talk. This course is the first of a series of three lectures that I am doing on cerebral palsy. This one will cover the clinical presentation and how you evaluate a child with CP or a potential CP diagnosis. The later lectures will discuss functional interventions.

We learned some of this in school, and some of you may treat kids or adults with CP. Today, we will take a more detailed look at cerebral palsy.

Definition of Cerebral Palsy (CP)

Let's start with the definition. The diagnosis has kind of changed over the years.

History of CP Terminology

- 1861 Little - birth asphyxia as the cause of neurological disturbance in an infant (Pakula, 2009)

- 1889 Osler – named group of disorders "cerebral palsies" (Osler, 1889)

- 2007 Consensus Group – CP' cerebral palsy' was defined as "a group of permanent disorders of the development of movement and posture, causing activity limitation, that is attributed to non-progressive disturbances that occurred in the developing fetal or infant brain" (Rosenbaum et al., 2007)

- 2019 Shevell – 'Cerebral Palsy Spectrum Disorders' (Shevell, 2019)

In the 1800s, it was described as the cause of a neurological disturbance, usually from birth asphyxia. They knew it was something that happened around birth. The definition has changed over the years. In 2007, we landed at a "group of permanent disorders of movement and posture," causing some activity limitations attributed to non-progressive disturbances in the developing or fetal infant brain. We have defined that even a little more lately and will talk about it soon.

- Timeline calls for early diagnosis of CP, including development of evidence-based tools with best predictive validity for CP (Te Velde et al., 2019)

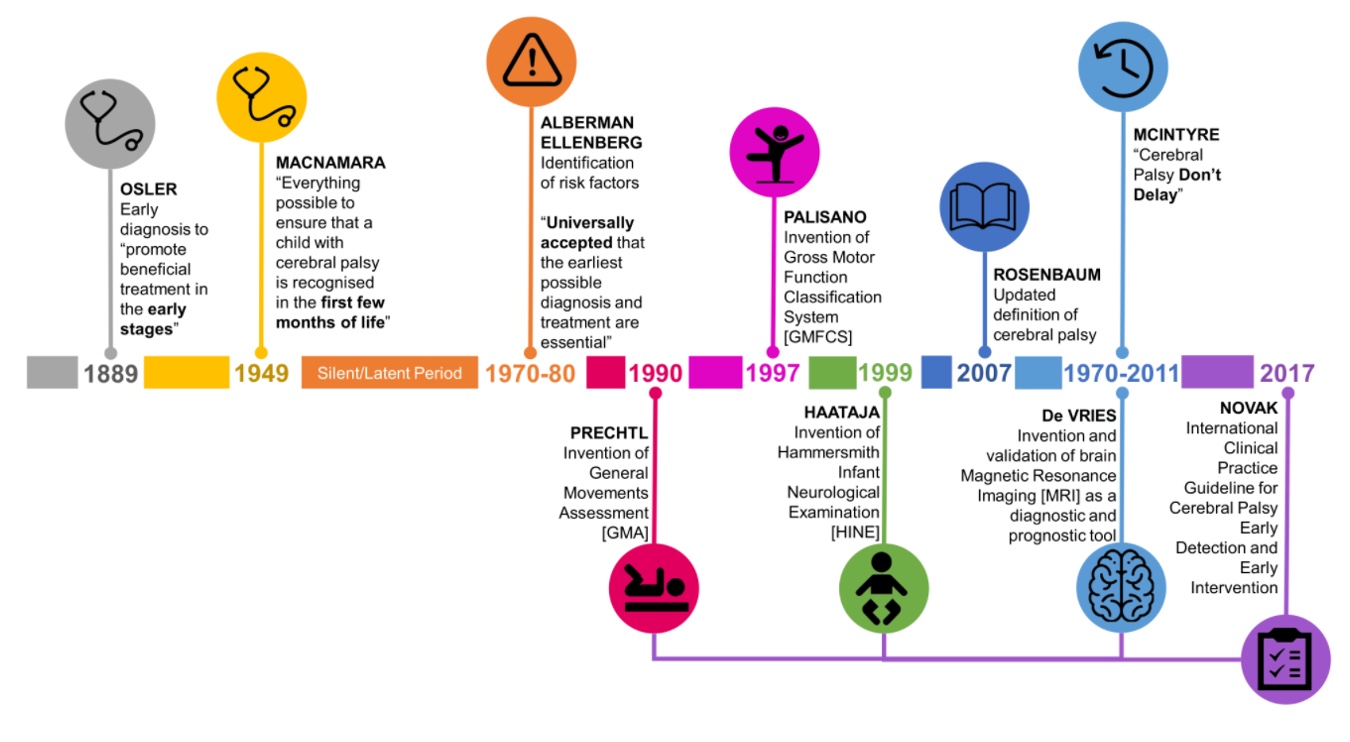

This infographic talks about how CP treatment and diagnosis have evolved over the years, starting in the 1800s (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Infographic on the timeline of CP terminology. (Click here for an enlarged image).

In the late 1800s, they knew catching CP early and intervening was good to promote better outcomes, but they noted a "latent neurological period" where they did not think things happened. Our understanding of the fetal and infant brain has evolved, which has affected our thinking around CP. There was a lot of activity in the 2000s around classifying and understanding these kids.

Some guidelines came out of the APTA and Dr. Novak in 2017. There is a lot that we know about cerebral palsy. Less is known about children with developmental coordination disorder (my specialty) or autism. I am jealous of the CP world because they have much more information.

- Debate about the definition of CP always centers on the earliest age at which it can be diagnosed

- Early diagnosis

- Promotes access to appropriate intervention

- Minimizes negative impact (Alberman & Goldstein, 1970)

- Maximizes function (Ellenberg & Nelson, 1981)

There has always been debate about what falls under CP or qualifies as such. What is the earliest we can diagnose it? We have always known that diagnosing early promotes access to intervention, minimizes the negative impact, and maximizes function. They knew that early diagnosis was meaningful way back when, and that is something that is even more so now.

What is Cerebral Palsy (CP)?

- An umbrella term that describes a group of disorders of the development of movement and posture, causing activity limitation that is attributed to non-progressive disturbances that occurred in the developing fetal or infant brain

Several things will fall under this, but they all come from an insult to the developing fetal or infant brain, and they're non-progressive. It is not something that is going to get worse over time.

What is CP Not?

- Cerebral palsy is not progressive (i.e., brain damage does not get worse)--> secondary conditions exist, such as muscle spasticity, which can develop and may get better over time, worse, or remain the same

- Cerebral palsy is not communicable--> it is not a disease and should not be referred to as such

- Although cerebral palsy is not "curable" in the accepted sense, training and therapy can help improve function

CP is not progressive as it does not get worse. Symptoms of CP-like spasticity, range of motion, and contractions can get worse, but this does not mean the CP itself is getting worse. The insult to the brain happens and does not change. Some CP can cause things like seizures, and the episodes can then cause further damage to the brain.

Although CP is not curable, we can improve function for these kids.

How Has the Definition Changed?

- What constitutes cerebral palsy in the twenty‐first century? (Sheedy et al., 2014)

- Genetic disorders that include brain abnormalities and are non-progressive meet the criteria for CP (estimated to possibly be up to 10% of all CP)

- In general, injury must occur before age 2 years to be considered CP

- The motor disorders of CP can be accompanied by any combination of impairments in the following: sensation, cognition, communication, perception, behavior, and/or by a seizure disorder (Bax et al., 2005)

How has the definition changed? Lately, we have included more things in this umbrella term. The article "What Constitutes CP in the 21st Century" discusses how we can include things like genetic disorders that impact the brain and trauma that happens after birth. It also consists of non-accidental traumas or anything that happens to the developing brain within those first few years. At my hospital, I have seen some infants with traumatic brain injuries that now fall under the CP umbrella. Although they do not have CP in the classic sense, they present that way and benefit from the treatments afforded to the CP population. So it makes sense clinically.

A motor disorder is the main symptom of CP, but it can be accompanied by a combination of impairments in sensation, cognition, communication, perception, behavior, seizure disorders, et cetera. All these symptoms are irrelevant to whether a person has CP, but we know that they accompany them frequently.

When Can You Identify CP?

- Typically not diagnosed until 12-24 months (Rosenbaum et al., 2007)

- Newer research indicates that CP can be accurately predicted or diagnosed as "high risk for CP" before 6 months (Novak et al., 2017)

Typically, CP is not diagnosed until 12 to 24 months, which is pretty current information. I know the age is getting lower, which is what we want, but years ago, the child was 3, 4, or 5 before CP was acknowledged. However, newer research indicates that CP can be accurately predicted before 6 months. We know that a brain insult has happened, which will be diagnosed as CP before 6 months, which is huge. After the research by Dr. Iona Novak in Australia, our hospital started pushing for early diagnosis. We have seen that slow down a bit because there are many reasons why people do not want to diagnose early. We will get into that in a couple of slides.

Early Detectable Risks

- Newborns - screening should be done on any high-risk populations through 5 months of age

- Prematurity, neonatal encephalopathy, birth defects, NICU admits

We can see things early that set kids up for CP, including being born prematurely, having any encephalopathy as a neonate, having birth defects, or having spent any time in the NICU. All these cases should be screened for CP.

Infant Detectable Risks

- These signs prompt further evaluation for CP (Novak et al., 2017)

- >4mo

- Persistent hand fisting

- Persistent head lag

- >6mo

- Not supporting weight through the plantar surface of feet when placed in standing

- >9mo

- Not sitting independently

- 6-12 mo

- Leg stiffness

- Asymmetries

- Hand preference before 12 mo

- Asymmetry in posture or movement

- >4mo

Here are some detectable risk factors that should prompt further evaluation. They should be evaluated if a child has persistent hand fisting or head lag. If they are not bearing weight through the plantar surface of their feet when held up at six months or older, this is also a concern. If they are not sitting independently by nine months or older, we should look for CP. Anywhere between 6 and 12 months, it is concerning if they have leg stiffness. Many parents will notice this while changing diapers as it may be hard to get their legs apart or up. Lastly, it is not typical to have any asymmetry or a hand preference before a year old.

Tools for identifying CP/Risk for CP (Before 5 Months)

- The 3 tools with the best predictive validity for detecting CP before 5 months adjusted (Novak et al., 2017)

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

- Prechtl Qualitative Assessment of General Movements GMs (Einspieler et al., 1997)

- Hammersmith Infant Neurological Examination HINE (Haataja et al., 1999)

This information comes from Iona Novak's 2017 guideline for diagnosing and identifying CP. It is a fantastic document and in your references. I am impressed by how much we know about this population and how we can recognize them early. Before 5 months adjusted age (allowing catch up for prematurity), the three things that best identify risk for CP are an MRI, looking for abnormalities in the brain, the Prechtl Qualitative Assessment of General Movements (GM), and the Hammersmith Infant Neurological Examination (HINE). These three tools together are amazingly 95 to 98% predictive of CP.

Prechtl Qualitative Assessment of General Movements GMs (Einspieler et al., 1997)

- Standardized neurological exam scored by a certified examiner watching a video of the baby

- For ages birth – 20 weeks adjusted

- Assessor is watching for the absence or presence of movements expected for age

- 0-9 weeks – "writhing" movements

- 9-20 weeks – "fidgety" movements

- 95-98% predictive of CP (Prechtl et al., 1997; Hamer, Bos & Hadders-Algra, 2011; Einspieler et al., 2015)

- Parent can access testing using the BabyMoves app

The Prechtl Qualitative Assessment of General Movements, or the GMs, is a standardized neurological assessment done by a therapist, usually who is certified, as it requires extra training. This is used for children from birth through 20 weeks. They do it on video. In Australia, an app called BabyMoves is where the parents can submit a video on an app on their phone, and a certified therapist will look at it. The length of time they need for the video varies depending on age. The certified therapist is looking for the presence or absence of these typical or atypical movements.

I am not certified, so I am not attuned to looking at these things, but anywhere from 0 to 9 weeks, we are looking for writhing movements. If they are absent, that indicates there might be CP. From 9 to 20 weeks, we look for fidgety movements; if they are missing, this is also a sign of CP. I am unsure if the app is available here in the United States. Whether a therapist is taking the video or a parent is giving it to the therapist, it has good validity.

Hammersmith Infant Neurological Examination HINE (Haataja et al., 1999).

- Standardized neurological examination of cranial nerve function, posture, quality, and quantity of movement, muscle tone, and reflexes and reactions

- HINE score at 3 months <57 is 96% predictive of cerebral palsy

- No specialized training is required but is recommended for inter-rater reliability

The HINE is another standardized assessment, but you do not have to be specially trained. It helps to work with other therapists who know how to complete the HINE to ensure we are all looking at the same thing and assessing it the same way (inter-rater reliability).

The HINE website has relatively dated videos, but they are helpful in how to move the baby through these positions. They result in a score and have cutoffs for certain months of age. For example, at three months, a score of under 57 is 96% predictive of CP.

Video 1

Here is a video of me moving a baby through some HINE movements. It is a simple clinical exam, and you can get good predictive abilities. There is no sound, and I did my best to block his face. I am looking for cranial nerve function, including auditory and visual responses, reaching, symmetry, tone, and abnormal resistance. I am also looking for tightness in his specific joints and whole body and reflexes. Can he segment his body, or is he stiff? Does he bring his head up? If you look at the instruction manual for the HINE, it talks you through what you would count as a positive score and a negative.

Tools for Identifying CP/Risk for CP (5-24 Month Adjusted)

- The 3 tools with the best predictive validity for detecting CP 5-24 months adjusted (Novak et al., 2017)

- Hammersmith Infant Neurological Examination HINE (Haataja et al., 1999)

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

- Motor Assessments

- Developmental Assessment for Young Children DAYC-2 (Voress & Maddox, 2013)

- Alberta Infant Motor Scale AIMS (Piper et al., 1992)

- Neurosensory Motor Developmental Assessment NSMDA (Burns, Ensbey & Norrie, 1989)

Anywhere between 5 and 24 months, the tools change, and they do not have the same amount of sensitivity. The HINE recommended for older kids, an MRI, and any motor assessment listed are suggested for this age group to measure the extent of the motor deficit. These are all norm-compared exams or assessments where the child is compared to a normative population.

Developmental Assessment for Young Children-2 DAYC-2 (Voress & Maddox, 2013)

- Norm-referenced instrument designed to identify possible delays in children ages birth – 6 yrs in the areas of cognition, communication, social-emotional development, physical development, and adaptive behavior

- No specialized training required

- 89% predictive of cerebral palsy (Maitre, Slaughter & Aschner, 2013)

The Developmental Assessment for Young Children (DAYC) looks at children from birth to six years to see how they interact with various objects. There is no specialized training required. I am unfamiliar with this specific assessment, but it uses everyday items like the Peabody. However, this is specific for younger babies. If the child is significantly below a normed population, it is 89% predictive of CP.

Alberta Infant Motor Scale AIMS (Piper et al., 1992)

- Standardized test that assesses gross infant motor skills from ages 0-18 months

- It evaluates weight bearing, posture, and antigravity movements of infants

- Infant's least and most mature item in each subscale is identified and marked as observed

- No specialized training required

- 71-83% predictive of CP (Spittle et al., 2015)

The Alberta Infant Motor Scale is similar to the HINE, where you watch the baby move through certain positions, looking at gross motor skills like weight-bearing posture and antigravity movements. You are looking for the least and the most mature movements to get that child's "window" of neurological functioning. It is not quite as predictive (71-83%), but it still gives you some critical information.

Neurosensory Motor Developmental Assessment NSMDA (Burns, Ensbey & Norrie, 1989)

- Criterion-referenced assessment tool that measures neurodevelopment ages 1 month - 6 years

- 5 domains: neurological, postural, sensory, fine, and gross motor

- Provides total functional grade of normal; or minimal, mild, moderate, severe, or profound deviation

- No specialized training required

- 79-89% predictive for CP (Spittle et al., 2015)

(Spittle et al., 2015)

The Neurosensory Motor Developmental Assessment (NSMDA) is another criterion-referenced assessment tool that looks at five domains: neurological, postural, sensory, fine motor, and gross motor. You can assess higher-level skills involving toys with a more significant age range. No specialized training exists for this; the predictive ability is around 80 to 90%.

Diagnosis or Classification?

- Tools for diagnosis have better predictive validity than tools which predict classification or type of CP

- Early diagnosis is recommended, but not early classification

- Classification of type of CP can come later (Novak et al., 2017)

First, we want to know if they have cerebral palsy, and then we look at classification. We will discuss that in the following area as classification is what type of movement children with CP have and how extensive it is. Do they fall under the umbrella? Again, tools for diagnosis include an MRI, the HINE, the GMs, et cetera. Some of these standardized motor assessments have much better predictive validity than tools that predict classification. Thus, classification tools are not recommended for young children. There is not much validity for using a classification tool on a young infant and saying, "They are probably going to end up a spastic hemiplegic." Classification comes later, but early diagnosis is recommended.

A Note About MRIs

- A normal MRI does NOT exclude a diagnosis of CP

- Some studies have suggested that as much as 10-13% of babies with CP may have normal structural imaging (Darsaklis et al., 2011; Krägeloh‐Mann & Horber, 2007; Reid et al., 2014; Towsley et al., 2011)

I was shocked when I learned this a couple of years ago, but a normal MRI does not exclude a diagnosis of CP. Years ago, we would pick up signs of cerebral palsy and send the child to get an MRI through a neurologist or the rehab clinic. We would assume they did not have cerebral palsy if it were normal. The umbrella has been expanded so that a child can have a diagnosis of CP but a normal MRI.

You may wonder, "isn't it a problem with the brain that causes CP?" Yes, most CP is caused by an insult to the brain that you can see on an MRI. However, recent studies suggest that as many as 10 to 13% of babies with CP have standard structural imaging. These may be children with chromosomal abnormalities or genetic things that did not use to qualify as CP but present like CP. It is a learning process for everybody involved, but if they present like CP, it makes sense that they qualify.

Barriers to Early Diagnosis

- Lack of definitive biomarkers and/or definitive clinical signs

- Desire to rule out every other possible treatable condition and/or lack of curative treatments

- Difficult conversation!

- Uneasiness about false positives

We want to push early diagnosis so they can get better treatment, and some of this is time-dependent. The earlier you get moving neuromotor interventions, the better outcomes you have. Some people do not want to do that. Historically, pediatricians may want to wait and see, not only for CP but for other things like autism and speech delays. Babies all develop differently, so pediatricians and parents want to rule out every other possible treatable condition.

Many families know their child may have CP, but they go to every clinic and doctor to rule out other things. They look at different possibilities because they know that CP cannot be cured, but in doing so, they are avoiding where we can make the most impact. We are not curing them but trying to give them the best outcome. It can be a tricky, challenging conversation.

In our hospital, we started educating our physicians because data shows that parents want this information earlier and that kids benefit from earlier treatment. There was a lot of pushback because they did not want to say CP until they knew.

Concern for Error in Diagnosis

- False Negatives

- Deficits may not be apparent at birth (spasticity) (WHO, 2011)

- 10-13% have normal MRI (Darsaklis et al., 2011)

- 50% have uneventful delivery (Whiting, 2003)

- 30% achieve early motor milestones on time (Granild‐Jensen et al., 2015)

- False Positives

- Perinatal trauma/illness does not always cause lasting deficits (WHO, 2011)

- However

- <5% of CP diagnoses are false (Granild‐Jensen et al., 2015)

- Almost all false positives result in a different neurological diagnosis (Sellier et al., 2016)

There are many concerns about errors as we do not want to be wrong. False negatives (not picking up signs of CP) are much more common than false positives. For example, if a child is more hypotonic and not spastic, we might miss it. And if they have a normal MRI and not much else to contribute towards the diagnosis, it may not be picked up. Fifty percent of kids born with CP have an uneventful delivery. We know that one of the main things that can cause CP is a difficult or traumatic delivery. Thirty percent of children achieve their milestones right on time, especially the early ones that are not so demanding.

Again, there are more false negatives than false positives. False positives may be attributed to traumatic birth illnesses. The baby looks sick and neurologically impaired early on but does not turn out to be. However, research shows that less than 5% of CP diagnoses are wrong. The vast majority of times, we say it is probably cerebral palsy. Almost all have some other developmental problem if we get a false positive. It could be a delay, autism, or something else. Nearly all of them have some problem, but it might not be CP, so the concern for false positives is overestimated.

Delayed Diagnosis

- May deprive the child of early intervention services (McIntyre et al., 2011), which are proven to be more effective if provided at an early age (Shepherd, 2013)

- Worsens parental depression and stress (Baird, McConachie & Scrutton, 2000)

If we do not discuss the possibility of CP, we are depriving the child of early intervention services, which are shown to be more effective if provided earlier. You may think this will stress the parents, but they are already stressed out. Research shows that when we do not say something, it worsens parental depression and anxiety because they know something is up and do not want to say it. When we do not talk about the elephant in the room, we isolate the parent and invalidate them.

CP Prognosis

- Parents want to know as much as possible, as soon as possible, but it is hard to predict severity for children under 2 years

- In contexts with standard prenatal and neonatal care:

- 2 in 3 children with cerebral palsy will walk

- 3 in 4 will talk

- 1 in 2 will not have an intellectual disability (Novak et al., 2012)

According to studies, parents want to know as much as possible as early as possible. In Australia, they did a great study looking at what parents want to know, when they want to know it, how they benefit from it, etc. They all want to know what to expect in the next 30 years. We cannot tell them that, especially for children under two years. We can confidently say, "This is probably CP, but we cannot say with certainty that your child will or will not walk or talk." Some studies point that way, but they have to be interpreted cautiously as there are not enough of them, and the results are not strong enough.

With standard prenatal care, which most of us have in the United States, we can say, "This is what cerebral palsy is, what it looks like, and the statistics." Two in three children with CP will walk, three in four will talk, and half will not have an intellectual disability. It is not all bad. Unfortunately, we cannot see where the child will end up, but we can give them interventions that will provide them with the best outcomes.

As a developmental therapist, I get new evaluations for various reasons. I am hoping that some of you are in the same place. Years ago, I would look at a baby or a toddler and think that looks like CP. I would not say it because it was not my job to bring it up. And perhaps the doctor would not say it because they thought I would. The diagnosis gets delayed, and we feel we are protecting the family.

After reading this newer research, I am convinced that parents want to know, so I (and the rest of my team) started to bring up things like that. "I see signs that something might be wrong with the brain talking to the muscles. These symptoms would fall under cerebral palsy." Have you ever heard of that?" It is essential to start the conversation. Similar to autism, if I have to be the first one to say, "Have you thought about autism?" I will take it. I called a mom yesterday that I worked with in the past when her baby was six months old. I was the first to bring it up, and I wanted to talk to her about that experience. She was lovely enough to chat with me yesterday, and I want to share her story.

Video 2

Etiology & Epidemiology

- What causes CP?

- How prevalent is it?

- What are the subtypes of CP?

Let's jump into what causes CP, how prevalent it is, and what are the subtypes of CP.

What Causes CP?

Your muscles are not coordinated, you cannot control your body, and you cannot do a lot of things that other kids can do. Is there something wrong with the muscles or the nerves? Is it a peripheral nerve disorder? The answer is no, as it is the brain that is affected.

- Even though cerebral palsy affects muscle movement, it isn't caused by problems in the muscles or nerves

- Instead, faulty development or damage to motor areas in the brain disrupts the brain's ability to adequately control movement and posture

The connection is that the brain talks to the nerves and muscles, so CP is a brain disorder. Something has damaged the brain, and it is not giving the muscles and nerves the correct signals, so they cannot control posture and movement.

- Complete causal path to CP is unclear in ~ 80% of cases, but risk factors are often identifiable

- Risk factors can be identified in patient history during conception, pregnancy, birth, and postneonatal period (Nelson, 2008)

- Newer evidence shows that ~14% of cases have a genetic component (McMichael et al., 2015; Oskoui et al., 2015; Schaeffer, 2008)

Unfortunately, the complete cause of CP for 80% of children is unidentifiable. This is a considerable population that lawyers like to represent against labor and delivery doctors. However, many factors cause cerebral palsy. It can be a horrible birth, but many times it is caused by other factors. We may not be able to identify the complete causal path, but we can identify risk factors. And, as I said, newer evidence shows that 10% to 14% have a genetic component that was there all along.

When Does the Damage Happen?

- Most cerebral palsy is related to brain damage that happened before or during birth, though some is related to brain damage after birth (www.cdc.gov/NCBDDD/cp/data.html)

- Prenatal

- Genetic

- Congenital anomaly

- Infections

- Anoxia

- Metabolic disorders

- Intraventricular Hemorrhage (IVH)

- Perinatal

- Premature birth

- Prolonged or traumatic labor

- Anoxia

- Postnatal

- Vascular accidents

- Intracranial hemorrhage

- Trauma

- Infections

- Prenatal

The brain damage can occur in utero and takes up to two years to qualify as CP. In utero, prenatal factors include genetic, congenital infections, anoxia, metabolic disorders, and stroke. Perinatal can be from prematurity, prolonged or traumatic labor, and anoxia during birth. Postnatal could be from a vascular accident, hemorrhage, trauma, or infection.

Prenatal-Congenital

- Congenital etiologies occur because of failures in normal development of the fetal brain or nervous system

- In most cases, the cause of congenital cerebral palsy is unknown or possibly genetic causes (Smithers-Sheedy, 2014)

Congenital factors happen due to a failure in the normal development of the fetal brain and nervous system. Most of the time, we do not know precisely what that is. It is not something that you can identify in chromosomal testing or falls under a specific genetic disorder. The brain and the nervous system are not functioning correctly.

- Neural tube defects: Anencephaly, encephalocele

- Schizencephaly: Abnormal slits or clefts form in the cerebral hemispheres of the brain

- Microencephaly: Brain underdevelopment due to primary proliferation failure

- Lissencephaly: Failure of the neurons to migrate toward the periphery of the brain leading to absence of convolutions

- Cortical Dysgenesis: Brain cortex malformation

It can also fall under neural tube defects as the brain, and the spinal cord are formed. Other issues include schizencephaly, slits or clefs in the brain, microencephaly, where the brain is underdeveloped, and lissencephaly, where the convolutions do not develop. This disorder is also considered smooth brain syndrome. Cortical dysgenesis is where the brain does not form.

Prenatal-Hemorrhage

- Cerebral hemorrhages can follow any insult, trauma, or stress to the developing brain

- Hemorrhaging often occurs within the developing brain ventricles - intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH)

- When the bleeding resolves, what is seen on imaging is periventricular leukomalacia (PVL)

- Although damage is present at birth, it may not be detected for months

Hemorrhages in utero can follow insult, stress, and trauma to the developing brain. It usually starts with intraventricular bleeding in one of the developing brain ventricles, and then the blood pools in these ventricles and falls through. Typically, the blood falls through the holes in the ventricles and clears itself out. Sometimes it gets stuck and clogs up in the ventricles. Some areas do not receive new blood, causing periventricular leukomalacia that you can see on imaging. The damage is often there at birth, but we do not always see it.

- Hemorrhage Grading – based on severity

- I.Bleeding limited to lining of the ventricles

- II.Bleeding spills into the ventricles, but no enlargement or swelling

- III.Ventricles fill with blood and enlarge

- IV.Bleeding fills ventricles and extends into the surrounding brain tissue

(Papile et al., 1978)

Hemorrhages are graded from I to IV. A grade I IVH or hemorrhage is less than a grade IV. It is unusual for a child to have a grade IV IVH and not have some deficits or CP, but I have seen this in babies born at 23 weeks who do not have cerebral palsy. They have a brain bleed but no lasting damage, which is a miracle.

Perinatal – Anoxia/Hypoxia

- Lack of oxygen or limited oxygen to the fetal brain during birth can occur from dystocia

- Large fetus/small maternal pelvis

- Awkward fetal positioning

- Failure of the uterus/cervix to contract & expand

- In the full-term infant, hypoxia or anoxia can damage brain tissue

- Hypoxic Ischemic Encephalopathy (HIE)

Any trauma during birth that causes a lack of oxygen could cause that brain tissue to be deprived of oxygen. It can cause permanent damage if long enough. Traumatic birth dystocia is where the baby does not fit through correctly. This condition could be from a large baby and a small mom, awkward positioning like a breech delivery, or any failure of the uterus or cervix. If the baby is deprived of oxygen for whatever reason, that will fall under Hypoxic Ischemic Encephalopathy (HIE), where oxygen is not getting to the brain.

Postnatal

- ~10% of CP in the US (https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/cp/causes.html)

- Head trauma

- Non-accidental trauma/Child abuse

- Blunt head trauma from fall or MVA

- Infection

- Cytomegalovirus (CMV), neonatal herpes, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), bacterial meningitis

- Metabolic encephalopathy

- Toxic agents – alcohol, drugs

About 10% of kids with CP fall under the postnatal category. I have seen several kids with CP as brand new infants because they were abused or had blunt head traumas like a car accident or a fall. An early infection, toxic agents, or accidental ingestion of alcohol and drugs can also cause brain damage.

Epidemiology

- Cerebral palsy (CP) is the most common motor disability in childhood in the US (https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/cp/data.html)

- About 1 in 345 children in the US have CP

- Prevalence of 1 - 4 per 1,000 births worldwide

- Increased prevalence of CP for:

- Children born preterm or at low birthweight

- Significantly more common among black children than white children

- Hispanic children and white children are equally likely to have CP

CP is the most common motor disability in childhood in the United States. It is about 1 in 345 children in the United States, which is about 0.3%. Worldwide it is anywhere from 1 to 4 per thousand births, which is 0.1% to 0.4% of birth. Populations with higher instances of CP are those born early and with low birth weight, and significantly more black children have CP than white. Theoretically, socioeconomic factors may contribute to poor neonatal outcomes and other stuff. Finally, in the United States, Hispanic and white children are equally likely to have CP, for whatever reason.

Symptoms of CP

- CP

- Decreased muscle length

- Altered muscle tone

- Decreased muscle strength

- Decreased selective motor control

(Bax, 2005; Wright & Wallman, 2012)

The four primary symptoms of CP are listed above. These kids cannot do many activities and have decreased selective motor control.

CP Classification

- Tone & Movement

- Defines motor subtype

- Topography

- Unilateral or bilateral, UEs or LEs

- Gross Motor Function

- GMFCS

- Fine Motor Function

- MACS, Mini-MACS, AHA

- Communication

- CFCS

- Eating Function

- EDACS

We talked about ways that we can see signs of early CP. We talked about how we can have that conversation, why it is essential, and how common it is to have CP. The other side of this is classification. Once you get your head around it, it is handy to know, and you can see where your patient might fall on some of these spectrums. There is a lot of data about each category, which can lead to different interventions and outcomes that might benefit your client.

Classification By Muscle Tone

- What is tone?

- Continuous & passive partial contraction of muscles

- Muscle's resistance to passive stretch during resting state

- Tone is NOT the same as strength

- Strength is the amount of force a muscle can produce with a single maximal effort

- A spastic muscle can be weak, and a hypotonic muscle can be strong

One way we can classify kids with CP is by muscle tone. Tone is defined as continuous and passive partial contraction of muscles and the resistance to passive stretch. It is the resting state of the muscle and not the same as strength. Many families think their children are strong, but this is not true. Strength is the force a muscle can produce with a single maximal effort. Spasticity is the resting level of that muscle and cannot create a large movement. Theoretically, a spastic muscle can be weak, and a hypotonic or a floppy muscle can be strong.

Educating families on what tone is important because it looks like strength. They look like they are strong but cannot move and are tight. It is not functional strength. I like to use the analogy of a radio- a radio is like your brain, and tone is like volume. In most people, volume control is so precise.

The brain can turn the volume on a muscle to do fine controlled little movements, and then it can turn way up to do the powerful lifting. It can also go fast or slow, so the tone is the volume control on a muscle. In CP, the volume knob is broken, on or off to varying degrees. When a child with CP wants to move, it causes immediate tone like flexion. There is no gradual flexion, but it is one loud signal. For example, if they want to reach for something, their brain sends the signal to bend, which overpowers everything else. There is a considerable imbalance in the muscles.

It is helpful to talk to families about brain and tone imbalances. We must remind them that the tone is not fixable. And that's not our goal. Our goal is not to fix that knob, but maybe we can improve it. Hopefully, with movement and neuroplasticity, we can get them more control. The tone will be there, but we have to work with it. Depending on the tone, there are different categories.

Motor Subtype: Spastic

- Caused by injury to the cortex

- Overactive muscles with increased tendon reflex activity and velocity-dependent resistance to stretch

- Usually not present at birth, develops over time

- 85-91% of cases (Novak et al., 2017)

Spasticity is caused by injury to the cortex. This category is what you think of when you think of CP. They have an increased tendon reflex, overactivity, and velocity-dependent resistance to stretch. If you try to do a quick pull, they will pull back. It is usually not present at birth. Babies start floppy or moving, but it does develop. This is why we hesitate to classify anybody under two. Most kids with CP fall under this category (85% to 91%).

Motor Subtype: Dyskinetic

- Caused by injury to the basal ganglia

- Characterized by abnormal involuntary movements

- Dystonia – Involuntary twisted posturing, sustained or intermittent muscle contractions with repetitive movements; can be painful

- Athetosis – Involuntary writhing movement (4-7%)

Dyskinetic is caused by injury to the basal ganglia, characterized by abnormal, involuntary movements. When these kids try to do something, they posture and then move back. They are trying to make a controlled motion, but the whole body reacts. These movements can be painful and frustrating and are considered dystonia, which we often see in this category. A small portion in this category, 4 to 7%, is considered athetoid as they have consistent writhing movements.

Motor Subtype: Ataxic

- Caused by injury to the cerebellum

- Characterized by loss of coordination or movement quality

- May have intention tremors

- Movement with a shaky or tremulous quality (4-6%)

- Stress, excitement, or effort amplify incoordination

- Often follows initial stages of hypotonia

The ataxic subtype is caused by injury to the cerebellum. Kids in this category generally look fine if they are seated and supported. When they get up and move, they look drunk or tremorous. They have poor control over those more prominent movements, especially in their lower extremities. In the upper extremities, we see tremoring, characterized by a loss of coordination. This category often follows the early stages of hypotonia. So a baby that is floppy early on may end up with ataxia.

Motor Subtype: Hypotonic

- Characterized by generalized low tone (2% of cases), weakness, increased ROM, poor ability to move against gravity

- Often a transient stage in the evolution of athetosis or spasticity

- Hypotonia is not a universally agreed subtype and not used by some international registers and countries

The hypotonic subtype is characterized by generalized tone. It is a small portion of kids with CP, and there is an argument about whether that qualifies for CP or not. I have no opinion on that argument.

Motor Subtype: Mixed

- Many individuals have mixed tone in which spasticity and dystonia are both present

- Work needs to be done to determine ways to manage mixed type of movement disorders

A mixed tone is what we see most of the time. We will see a lot of spasticity with some dystonia or spasticity with some ataxia. We try to qualify these kids in different silos, but often they fall into several of them. More work needs to be done to figure out how to classify and treat these types.

Distribution/Topography Subtypes

- Emerge & change (age 0-2) as voluntary activity participation increases

- Symptom resolution – increased use of an affected limb

- Symptom worsening – increased dystonic posturing with voluntary movement

- Hemiplegic – 1 side of the body, involving the upper and lower extremity on the affected side

- Diplegic – 1 half of the body, involving both lower extremities

- Quadriplegic – All 4 limbs are affected

For body distribution or topography, where is the abnormal tone showing? This distribution emerges over the first two years as a baby does not have many voluntary movement demands. Not a lot is going on, but as voluntary participation, demands, and thinking increase, it starts to show. Sometimes the symptoms are resolved because the baby is using the affected limb more, and sometimes it worsens.

There is terminology for where it shows in the body. Hemiplegic is one-half of the body, and one arm and one leg on either the right or left. Diplegic would be half of the body, generally the lower extremities. A quadriplegic is all four limbs.

CP Population Distribution

- Spastic 85-91%

- Dyskinetic 4-7%

- Ataxic 4-6%

- Hypotonic 2%

The majority of kids with CP have spasticity.

Regarding topography, unilateral spastic hemiplegia, half the body, is about the same percentage as diplegic, which is just the lower extremities. The other types are distributed among bilateral spastic quadriplegia, ataxia, dyskinetic, and the questionable 2% in hypotonia. The prognosis is based on topography and the type of tone. Again, it's difficult to predict that under two. So they do not recommend determining that under two. We do not want to say they are dystonic, spastic, or whatever. Still, deciding if it is unilateral or bilateral and what limbs are involved is essential because the interventions differ. If it is unilateral, we can do things like constraint-induced movement. And I'll talk about that more in my interventions lecture. And then, if it is the lower extremities involved, PTs may want to do hip surveillance because that can prevent some bad dislocations and deformities.

Motor Subtype Prognosis

- Difficult to accurately predict subtypes under 2

- Important to identify unilateral or bilateral involvement as early as possible because the recommended interventions differ

- Unilateral UE – CIMT (Eliasson & Holmefur, 2015)

- Bilateral LE – Hip surveillance (Hägglund et al., 2014; Elkamil et al., 2011; Hägglund et al., 2005)

Prognosis is based on topography and the type of tone. Again, it is difficult to predict that under the age of two. We do not want to say that they will be dystonic or spastic, but it is crucial to determine if it is unilateral or bilateral and what limbs are involved as the interventions differ. For instance, if it is unilateral involvement, we can do things like constraint-induced movement like the child we just discussed. I will talk about that more in my interventions lecture. If the lower extremities are involved, the PTs do hip surveillance to prevent some bad dislocations and deformities.

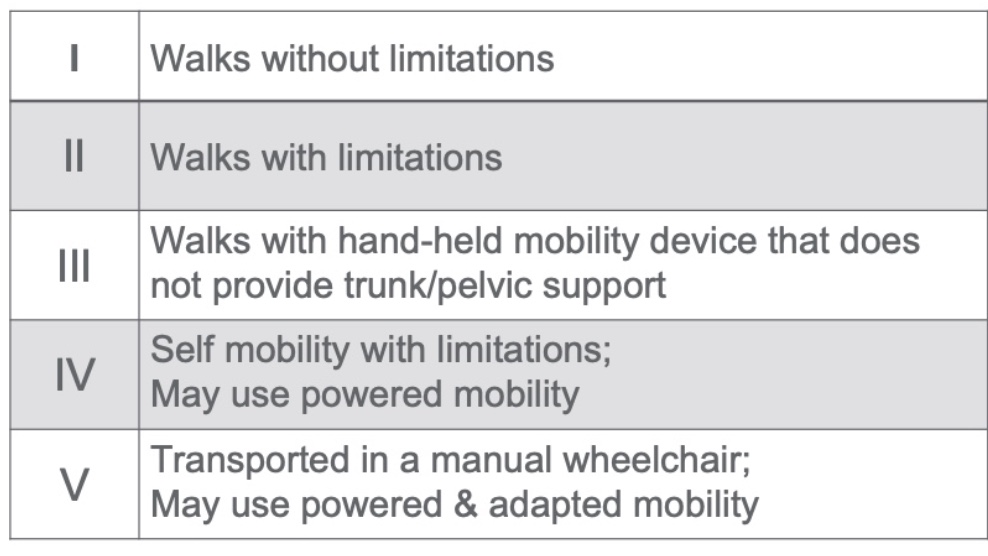

Gross Motor Function

- In children with CP, gross motor function can be described in 5 levels using the Gross Motor Function Classification System GMFCS (Palisano et al., 1997) or the Extended & Revised version GMFCS-E&R (Palisano et al. 2007).

- Available free online on multiple websites

- Generally stable after age 2

- Do not assign before age 2 – period of rapid change

Another way to classify these kids is via gross motor function. In children with CP, gross motor function can be described in five levels using this handy tool called the Gross Motor Function Classification System, or the GMFCS. This tool is widely used, and there is a lot of data. It is free on many websites. If you Google GMFCS, you can see many resources.

Generally, GMFCS levels are stable after age two, regardless of interventions (Figure 2). So when we do therapy intervention, we are not trying to change them to a different level. This is important for the physicians, families, and us to know. It is pretty stable. Thus, we do not want to assign it under two because there is a rapid period of change.

GMFCS-E&R General (Palisano et al., 2007)

Figure 2. GMFCS-E&R General.

In your handouts, you should have these broken down by age because the expectations change, and you can see pictures online. There are also great tools for deciding between the levels, and it is a handy resource.

Level I is the least impaired, and level V is the most impaired. Level I walks without limitations, while Level II walks with limitations. They may use braces or have some awkward movements. Level III walks with a handheld mobility device, like Lofstrand crutches, a cane, or a walker. Level IV is self-mobility with limitations, perhaps a gait trainer, a stander, or powered mobility. Finally, Level V is dependent and needs to be moved and transported everywhere. They can use powered mobility if it is significantly adapted.

CP Population by GMFCS

- Compiled from:

- Ohrvall, 2010, Sweden

- Reid, 2011, Worldwide

- Hidecker, 2012, US

- Christensen, 2014, US

- Novak, 2014, Australia

- Delacy, 2016, Australia

- Novak, 2017, Australia

- Mcallister, 2022, Sweden

I pulled from several studies to create the breakdown in Figure 3. As I said, there is a lot of data on GMFCS, but it varies by country and research. This is not a systematic review but a visual resource that I created from the compiled data.

Figure 3. Pie chart of GMFCS percentage from each level.

Most kids are in level I or II, and then the rest are evenly distributed between III, IV, and V. Most of the kids are ambulatory in categories I or II, level I or II.

Caregivers & GMFCS

- 92% of caregivers reported that they preferred to learn about their child's GMFCS level

- 45% had this information

- 83%of caregivers said it would be helpful to revisit this information over time

(Bailes et al., 2018)

We have excellent data about caregivers and what they want to know about the GMFCS. In one study, 92% of caregivers reported wanting to know their child's GMFCS level. It seems like a simple thing. We need to educate them about the levels and how their child will remain at that level. This may change their perception of what we are doing in therapy and how it is going. The study also showed that 92% wanted to know the information, but only 45% had it. Another 83% of them reported that it would be helpful to revisit the data.

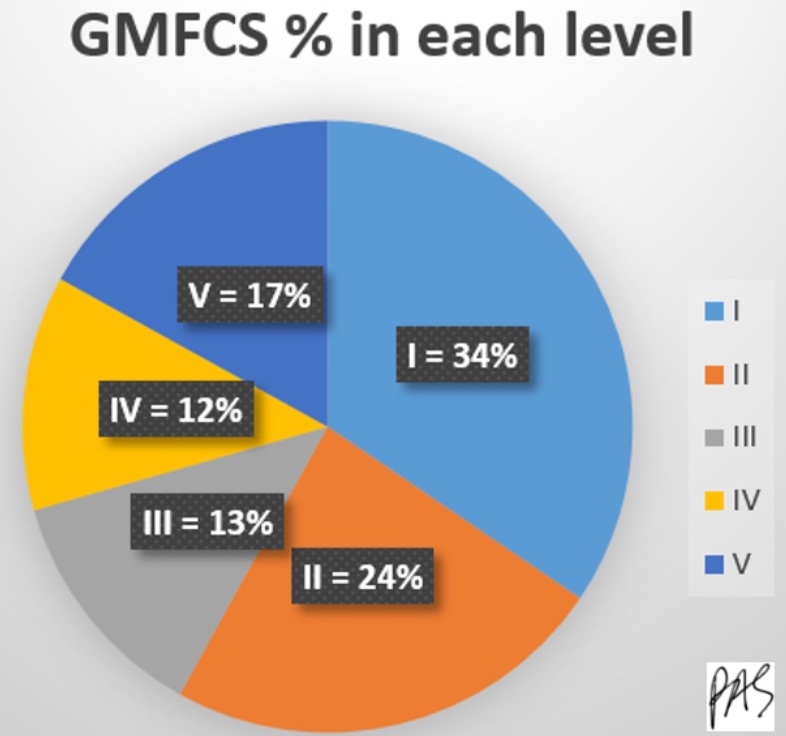

Fine Motor Function

- Measured in kids with CP using:

- Manual Abilities Classification System MACS (Eliasson et al., 2006)

- Mini Manual Abilities Classification System Mini-MACS (Eliasson et al., 2017)

The GMFCS is for gross motor, and we measure fine motor with the MACS, the Manual Abilities Classification System, and for younger children, it is called the Mini-MACS. They are very similar.

MACS (Eliasson et al., 2017)

- Describes how children ages 4-18 years with CP use their hands to handle objects in daily activities on a regular basis (not BEST performance)

- Considers overall abilities, not each hand separately

- 5 levels based on self-initiated activity, need for assistance or need for adaptation

- Free online https://www.macs.nu/

Mini-MACS (Eliasson et al., 2017)

- Mini-MACS classifies children's ability to handle objects that are relevant for their age and development as well as their need for support and assistance in such situations

- For ages 1-4 years

- Also free online https://www.macs.nu/

The MACS is used for children between four and eight, and the mini-MACS is for one to four. These tools describe how they use their hands. It does not describe a hemi hand compared to a non-impaired hand; instead, it explains how children use their hands, plural, to do things. If they do everything perfectly well with one hand only, they would be unimpaired. Like the GMFCS, it looks at daily function, not a single limb's level of impairment.

MACS and Mini-MACS - General

There are five levels, and it is based on self-initiated activities.

Figure 4. MACS and Mini-MACS General.

You will not rate someone by saying, "Use your righty." You are looking at what they initiate on their own. It is free, and I have provided the link. The website gives more descriptives for each based on their age and tools to differentiate a II from a III, for example. There is no "right answer." You cannot put someone in an MRI and know they are a level II. This is something that clinicians decide together. One person can argue for II, and the other can say for III. With this tool, we can get some good prognostic data by following these kids for their lives. Like the GMFCS, I is the least impaired, and the V is the most impaired.

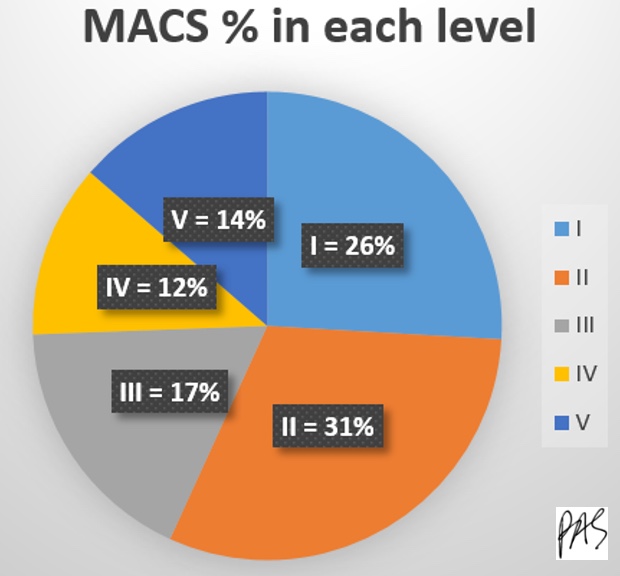

CP Population by MACS

- Compiled from:

- Ohrvall, 2010, Sweden

- Hidecker, 2012, US

- Mcallister, 2022, Sweden

Figure 5. Pie chart of MACS percentage in each level.

Fewer studies have been done on populations with the MACS, but the same as with the GMFCS, most kids are in levels I and II, so they are not that impaired.

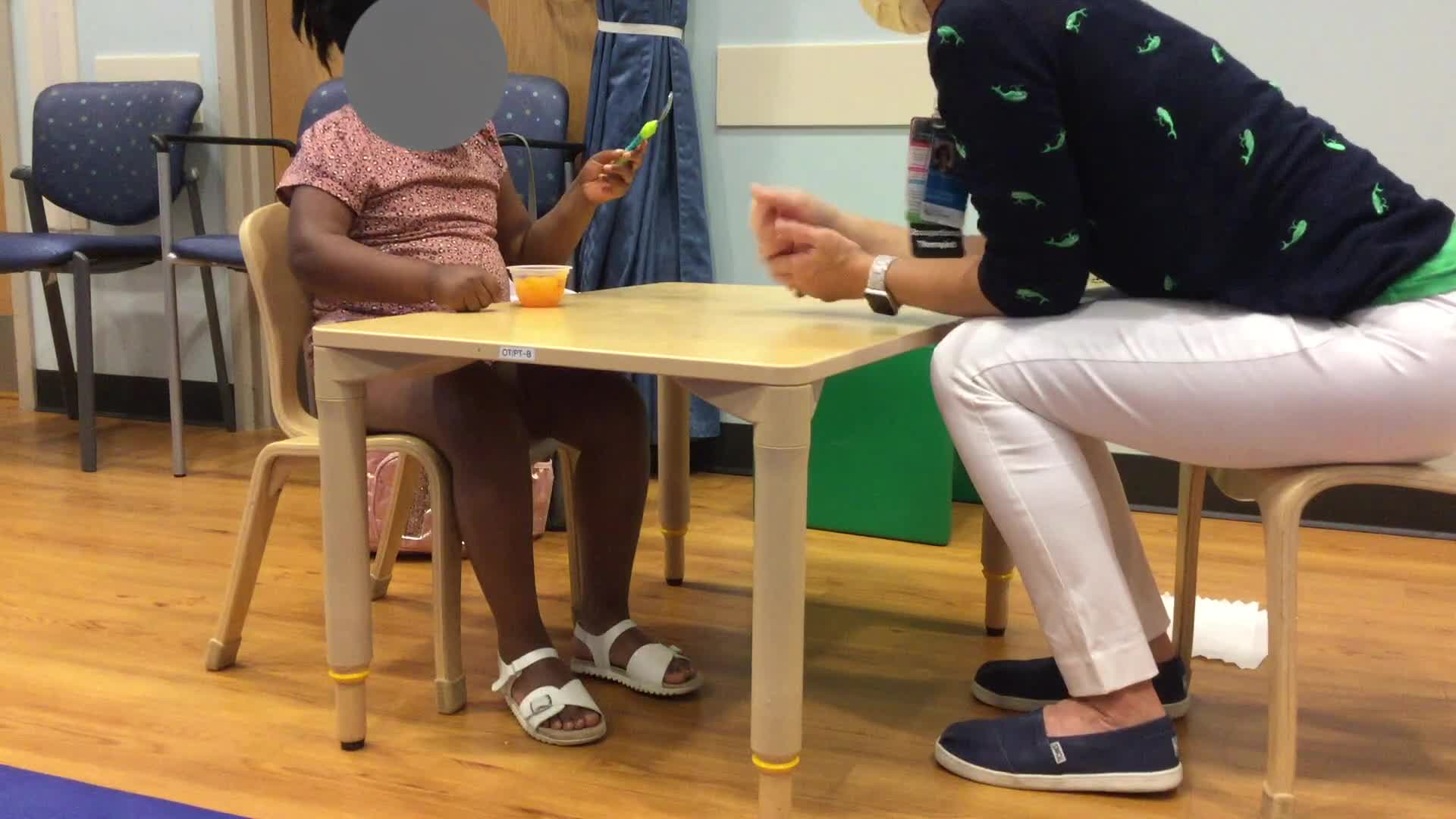

I want to pull some quick video clips for you to think about the subtype, topography, and GMFCS and MACS levels. There is no sound on these, and I know you cannot see everything, but it can give you some practice.

Video 3

She has spasticity, and her arm was curled in on the right side of her body. She is a GMFCS level II and walks with some limitations but does not need any crutch, device, or walker. For the Mini-MACS level, I rated her at a III as she needs significant adaptation to do most things involving two hands.

Video 4

This child has spasticity and dystonia. I know you cannot tell, but both of his arms are involved. And when he got excited, he threw himself back when he opened the Dorito bag. His movements are pretty uncontrolled. He has quadriplegia, as all four limbs are involved. He is a GMFCS level II, meaning he can ambulate without handheld devices, but he is uncoordinated. I gave him an IV for the mini-MACS level because he cannot open a package without adaptation. We are finding great ways to do things, do not get me wrong, but it is not without a lot of adaptation.

Video 5

This girl has spastic ataxia. When sitting down, she looks pretty good. However, when she gets up, she seems a little drunk and has diplegia in her arms, where she holds them oddly. She can write and do most things with both hands equally. Her GMFCS level is II. She does not use a handheld device, but she is uncoordinated. Her mini-MACS is level I, meaning she is not significantly impaired in fine motor control.

In recent years, people in different groups have tried to develop more ways of classifying these kids. Many studies have tried to see if the MACS level lines up with the GMFCS level. I do not know if they want this like a super score or something, but it does not matter. The GMFCS and the MACS levels are both great for getting a picture of what these kids can do functionally.

Some other classifying systems are used less frequently but may also be beneficial.

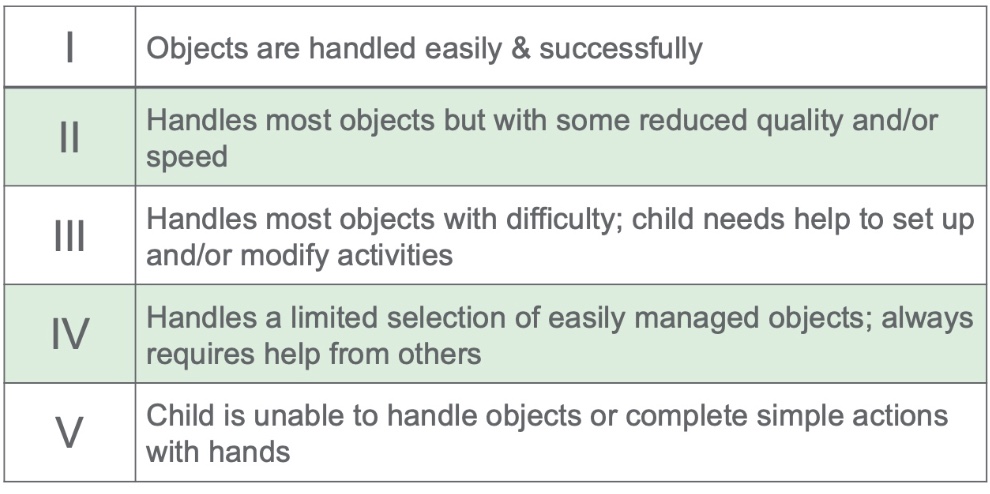

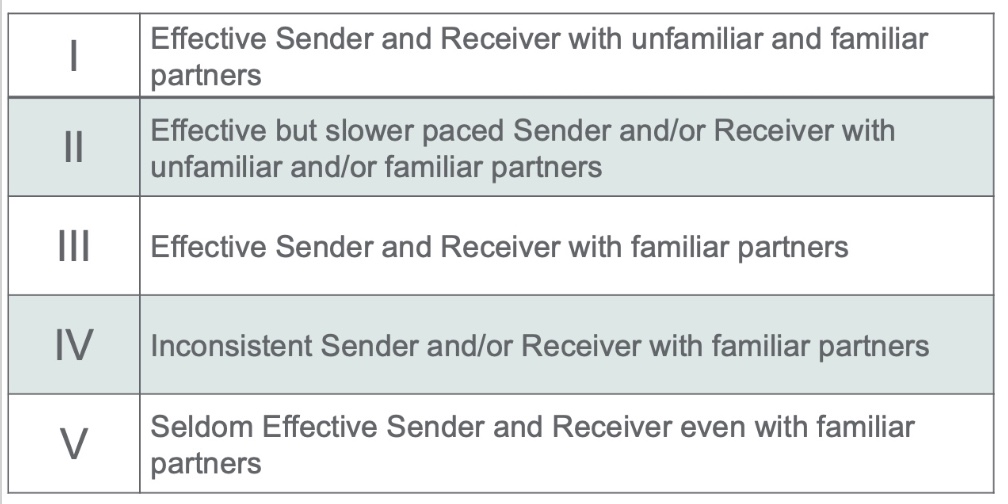

Communication Function

- Communication Function Classification System (CFCS, Hidecker et al., 2011)

- Describes everyday communication performance of an individual with CP in 5 levels

- Based on usual communication, not best capacity

- All methods of communication are considered: use of speech, gestures, behaviors, eye gaze, facial expressions, & augmentative and alternative communication (AAC)

- Free online https://cfcs.us/

The Communication Function Classification System (CFCS) looks at how kids use communication in everyday life and considers all communication, including gestures, behaviors, eye gaze, facial expressions, and augmentative communication. It is also free and online.

Communication Function Classification System (CFCS)

Figure 6. Communication Function Classification System (CFCS).

It follows the same pattern as the other systems, which is super handy. Level I is an effective sender and receiver of information, and Level V does not get information or send information even with familiar people, so very impaired.

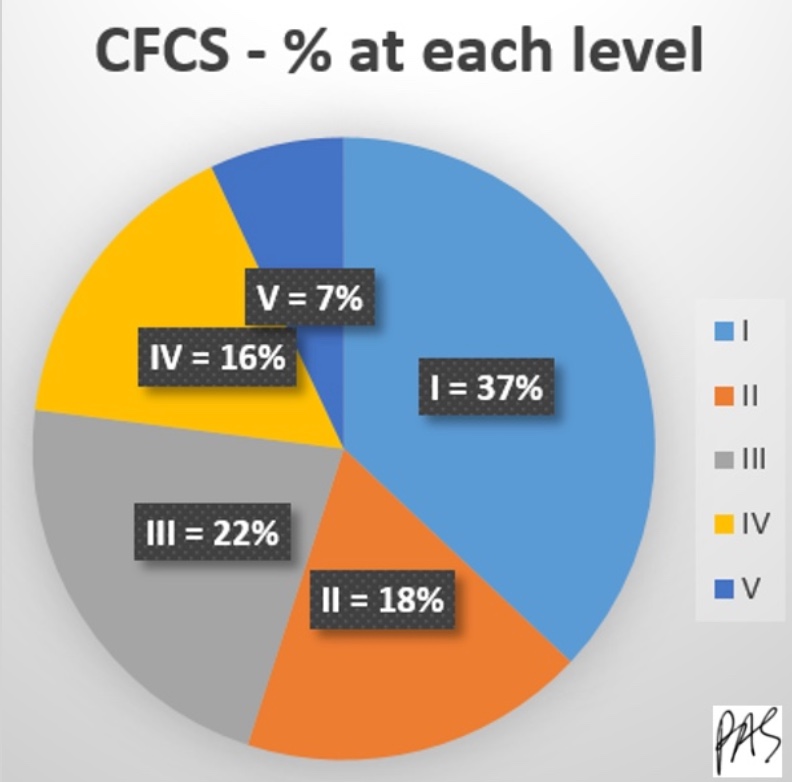

CP Population by CFCS

- Compiled from Hidecker, 2012, US

I found only one study using this, and the information is in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Pie chart of CFCS from each level.

Most kids are in those first two categories, and the first three categories make up more than 75%.

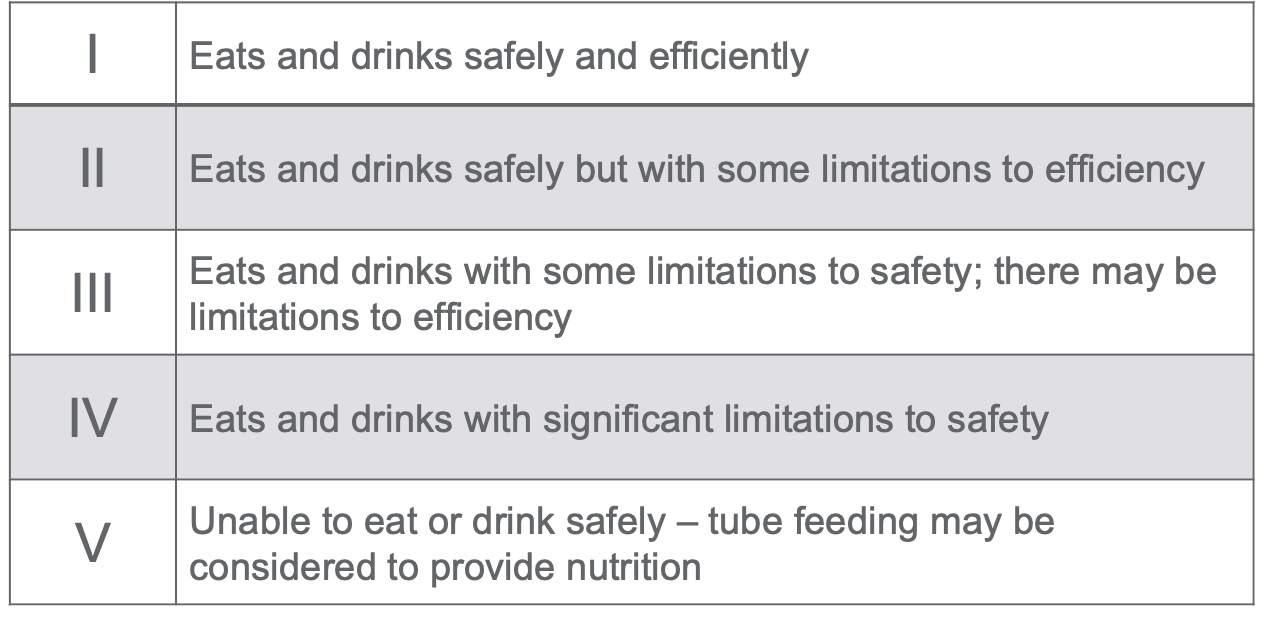

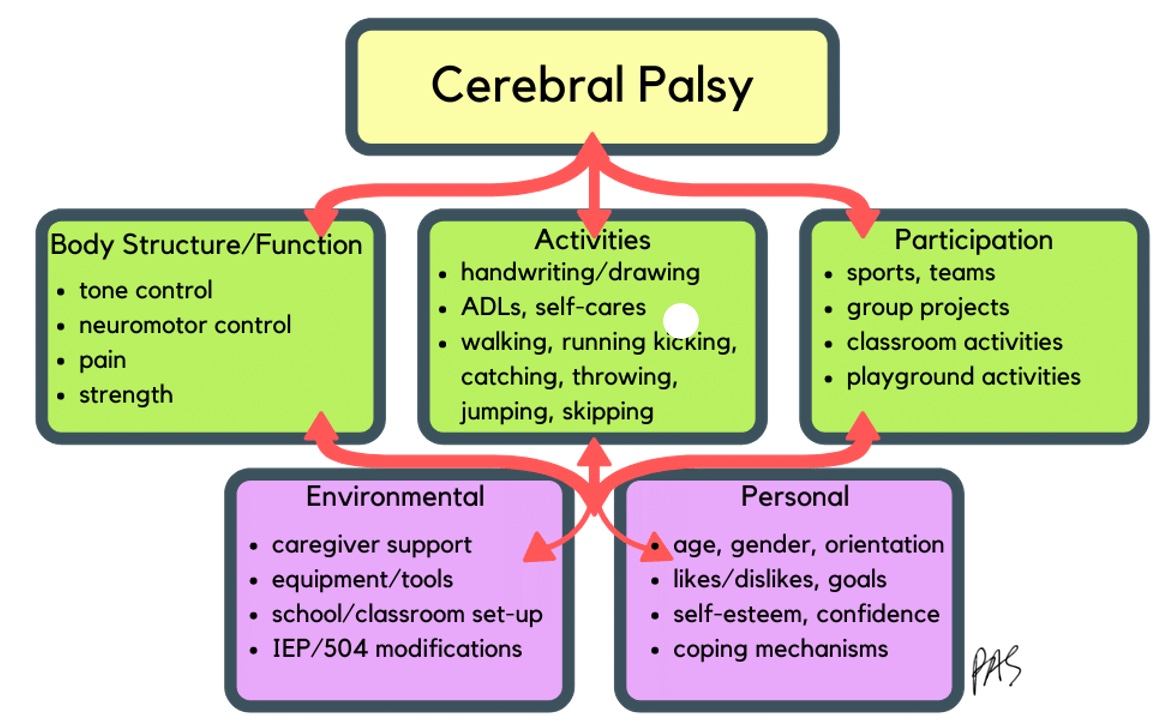

Eating Function

- Eating & Drinking Ability Classification System EDACS (Sellers et al., 2014)

- Classifies how individuals with CP eat and drink in everyday life

- Provides a systematic way of describing an individual's eating and drinking in five different levels of ability

- Age bands: 18 mo-3 yr, 3yr+

- Available free online https://www.edacs.org

Eating & Drinking Ability Classification System (EDACS)

There is another scale for eating function (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Eating & Drinking Ability Classification System (EDACS).

The Eating & Drinking Ability Classification System looks at how they eat and drink in daily life. It follows the same pattern as the others, where level 1 eats and drinks safely to level V, where the child is tube fed as they are not safe eaters or drinkers.

CP Population by EDACS

- Compiled from Mcallister, 2022, Sweden

Figure 9. Pie chart of the EDACS percentage at each level.

More than half fall in category one, which is excellent.

Again, I highly recommend looking at your kids with CP in terms of the GMFCS and MACS levels and consider using these other tools. Why do we need to know GMFCS levels as OTs? We look at gross motor function because it is required for occupation. It gives us a good look at what our kids need to do, want to do, and are expected to do. It also enhances our communication with MDs and PTs.

OT Evaluation

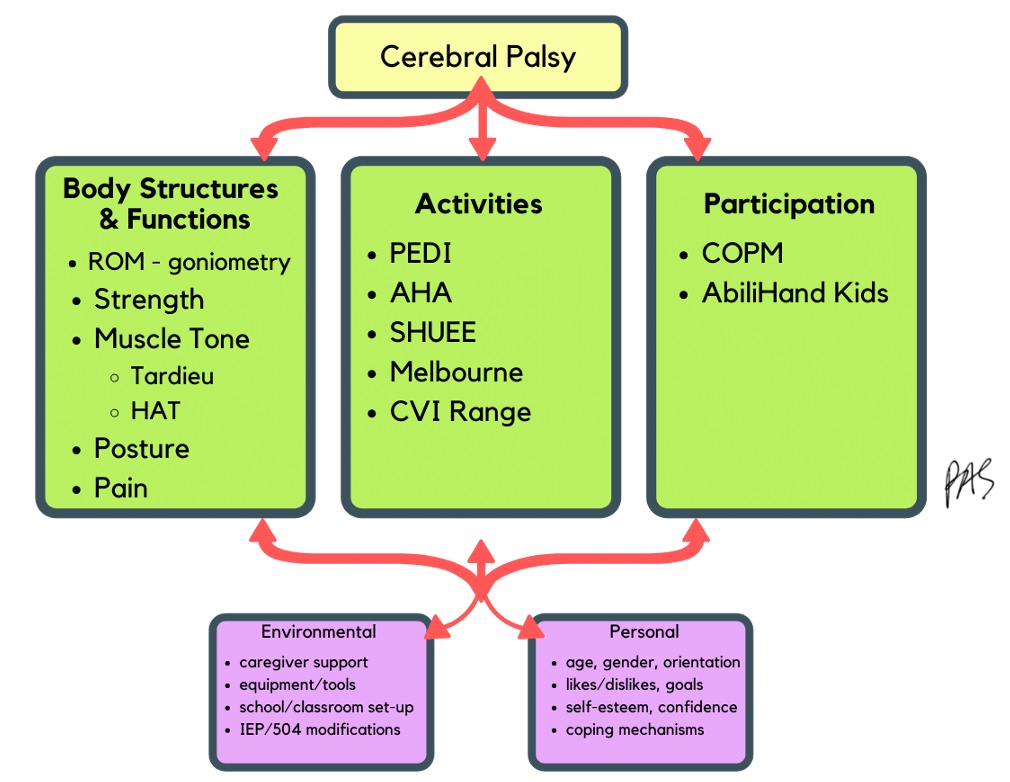

- Using the ICF Model (WHO, 2001)

- Recommended Tests & Measures

We talked about diagnosing and how we want to see them early. We also looked at classifying and breaking down these populations. Now, let's look at what we are doing during an evaluation.

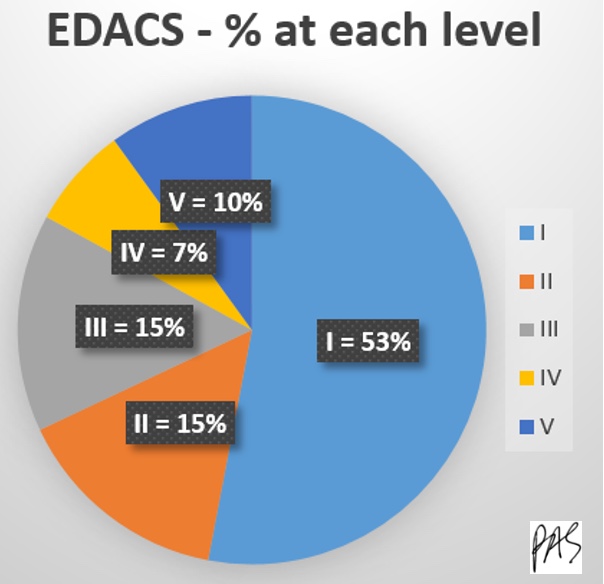

ICF Model

I like to look at the ICF model, The International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (Figure 10).

Figure 10. The International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health.

It was written in the 80s, and they revised it in the early 2000s. It looks pretty similar to me. The ICF looks at how any health condition impacts a person, from their body's structures and functions and how they participate in life. It also looks at environmental and personal factors that influence those things. If CP is a health condition, the body structure and function areas should include poor tone control, neuromotor control, pain, weakness, decreased range of motion, et cetera. Activities could be handwriting, drawing, self-care, walking, running, kicking, and other gross and fine motor activities.

The model also looks at how the health condition impacts participation. Participation includes playing with others, being in sports, being in teams, doing group projects, being in a class, and playing at recess. We also need to consider the supports or barriers in the environment. It also looks at personal factors like family, confidence, self-esteem, culture, and other factors that may impact a health condition.

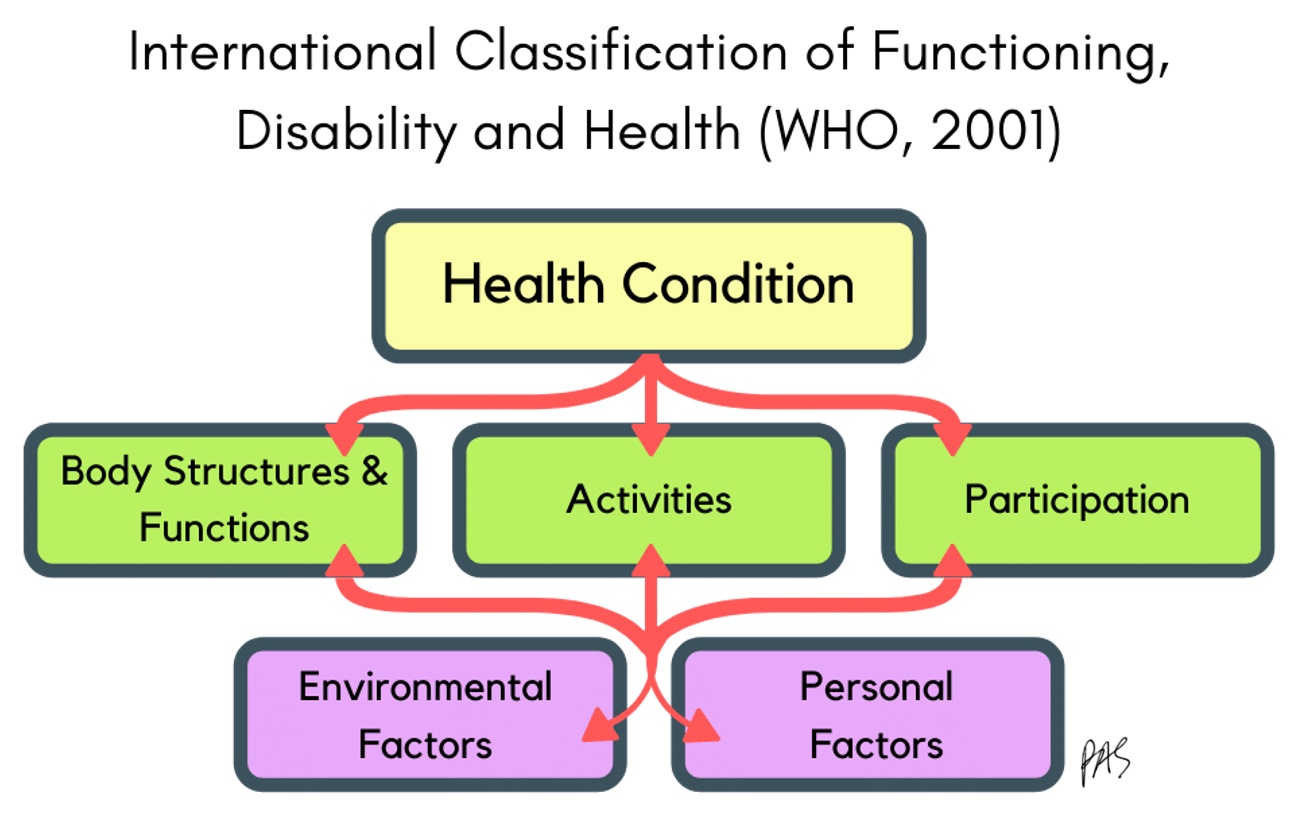

Evaluation: Cerebral Palsy

What is essential when we are looking at evaluation? Unfortunately, it is everything. We want to get a good picture of what is going on with the child with CP. Figure 11 shows an overview of this.

Figure 11. ICF Model for CP.

We will start at the bottom with environmental and personal factors.

OT Eval: Personal & Environmental

- History

- Birth history

- Developmental milestones

- Medical and surgical history

- Current functional status – GMFCS, MACS levels

- Physical Therapy, Occupational Therapy, and Speech Treatment

- Equipment and home environment

First, we want to ask about birth history, milestones, surgical and medical history, and their current functional status. We also want to know their GMFCS and MACS levels. If they do not have those, you are welcome to classify them as one. It is not an official thing. And, if they have had treatment before, you want to note what equipment they have.

OT Eval: Body Structures & Functions

- Range of Motion (ROM)

- Increased tone causes progressive muscle/tendon shortening

- Active ROM – indicates functional movement

- Limitations = decreased function

- Passive ROM – indicates joint & skin health

- Limitations = contractures, deformity, skin breakdown

- Assess via goniometry

- Record areas that deviate from norm, not all joints

- Check for any current day or night splints

Therapists love to measure body functions and structures. This is where you are going to see a lot of your impairments. We can use the ICF also to categorize measurement strategies (Figure 12).

Figure 12. OT evaluation according to the ICF.

We want to look at range of motion and increased or lack of tone that will impact the range. If they have spasticity, their muscles will constantly try to shorten. Do they have enough passive range to do things actively, or are they starting to get a contracture joint deformity? We can check their range by goniometry and note the areas that deviate from norms. You do not need to check every typical joint. We want to look at the areas causing problems, spasticity, or tightness.

And then we want to check here for any current day or night splinting to see if we are managing any of those things well or if they might need a splint.

- Strength

- Remember, high TONE ≠ high strength

- Commonly misunderstood

- Children with CP are weaker than healthy peers despite increased tone (Damiano et al., 1998)

- High tone fatigues a muscle but does not strengthen it

- Children with CP frequently experience muscle imbalances across joints (Eek, 2008)

- Poor neuromotor control

For strength, we want to see volitional muscle contraction and what the child can do. You can do that with manual muscle testing and a grip and pinch dynamometer. We want to also know about functional movement. Can they pick something up and move against gravity? Only looking at functional movement is enough to do a good evaluation. However, if you are looking to improve a specific muscle group and you want to track it over time, by all means, use manual muscle testing and grip and pinch testing. And remember, high tone does not mean strength. We want to assess their ability to move a muscle and joint with force intentionally.

- Muscle Tone: tension present in resting muscles and resistance offered during passive movement

- Abnormalities include spasticity, dyskinesia, ataxia, hypotonia, and mixed tone

- It prevents controlled, volitional, functional movement

- Contrary to earlier schools of thought, abnormal tone cannot be "normalized" by stretching, positioning, or patterns of movement

We need to look at tone to see where they may have spasticity, dystonia, or both, which prevents volitional, functional movement. Remember that we are not promising families that this is something we can normalize. Tone abnormalities come from the brain, and therapeutic interventions that work on breaking up the tone or alternative positioning do not fix the tone. We want to make their body healthy and strong and give them the desired function.

- Muscle Tone Assessments

- Modified Tardieu Scale

- Determines spasticity angle & grade between a slow, passive ROM (R2) and a quick, catch response (R1)

- (van Wijck et al., 2001)

- Hypertonia Assessment Scale

- Differentiates hypertonia subtypes to guide treatment

- (Jethwa et al., 2010)

- Barry-Albright Dystonia Scale BADS

- (Barry, VanSwearingen & Albright, 1999)

- Measures severity and impact of dystonia

- Training not required, but improves inter-rater reliability

- Modified Tardieu Scale

You can assess tone with a couple of different assessments. You may use these if looking at specific interventions like Botox with therapy or if you want to see progress over time. These are not necessary for a general evaluation, but they are handy. The Modified Tardieu Scale can tell you where the spasticity kicks in and where the passive range is. It defines spasticity. The Hypertonia Assessment Scale (HAT) differentiates between hypertonia and the different subtypes that can guide some treatments or medications they take. And then, the Barry-Albright Dystonia Scale measures the severity of dystonia joint by joint.

- Posture

- Positions in which the child frequently holds their body, assessed by clinical observation

- Highly impacted by tone

- Attempts to gain function may result in compensatory posturing, which can lead to contractures and worsening muscle imbalances.

- Posture itself, as well as function, may be improved by adaptive seating or positioning.

It is also essential to look at posture for function. What position does the child hold frequently? We see a lot of compensation to stay upright that might lead to contractures and imbalances, so we also want to assess that.

- Pain – why assess?

- 3 in 4 children with CP experience pain; symptoms increase with age (Novak, 2014)

- Adults with CP are more likely to have pain than typical adults (Peterson et al., 2010)

- May improve with positioning, eating, sleeping, moving – many daily skills impacted by OT

- Can be assessed with:

- Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability FLACC (Voepel-Lewis, 1997)

- FACES-R pain scale (Hicks, 2001)

- Numeric Rating Scale NRS (Solodiuk, 2010)

We also want to look at pain because many kids with CP experience pain, which is surprising and sad. If this is a problem, there are things that we, as OTs, can do. We can improve positioning, their diet, how they eat, when they eat, sleep, and moving to help decrease pain. We can use different pain scales to determine their level of pain.

Comorbidities

- Pain: 3 in 4 children

- Intellectual disabilities: 1 in 2 children

- Epilepsy: 1 in 4 children

- Hip displacement: 1 in 3 children

- Behavioral disorders: 1 in 4 children

- Sleep disorders: 1 in 5 children

- Functional blindness: 1 in 10 children

- Hearing impairment: 1 in 25 children

- (Novak, 2014)

Many comorbidities accompany CP, including intellectual disabilities, seizures, hip displacement, behavior disorders, sleep disorders, blindness, and hearing impairment that impact their ability to do activities.

OT Eval: Activities

- The Occupational Profile (AOTA, 2020) can determine the level of independence in age-appropriate activities, as well as highlight which occupations are of concern.

- Assessments can be used to tease out specific activity limitations in specific domains

- Results of these assessments can help guide therapy goals, intervention, and duration

Activities can be assessed with the occupational profile from our framework, looking at just their daily skills and what they typically do.

- Function in daily skills

- Pediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory Computer Adaptive Test PEDI-CAT (Haley et al., 2011)

- Compares function to norm-references and/or previous functioning for children 0-20 yrs

- Examines functioning in areas of daily activities, mobility, social/cognitive, and responsibility

- Useful in identifying impact of disability and potential goals

- No specialized training required

- Pediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory Computer Adaptive Test PEDI-CAT (Haley et al., 2011)

Do you have any feeding or dressing? Find out what they are doing compared to the normed age and if their participation is working for their family. Ask the family what would be the most helpful. Some assessments can tease things a little more, like the PEDI-CAT, Pediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory Computer Adaptive Test. It looks at the impact of disability on daily age-appropriate skills and breaks it down into different categories. It can help identify areas where the child may need extra work and the impact of CP on the child.

- Hand use in daily bimanual tasks

- Assisting Hand Asssessment AHA (Krumlinde‐Sundholm et al., 2007) – 6-12 yrs; Mini AHA – 18 mo-5 yrs

- Videotaped, play-based assessment of how well a child with unilateral impairment uses their affected hand during bimanual tasks

- Measures capacity to use impaired hand, helps guide goals and treatment

- Requires specialized training

The Assisting Hand Assessment, or AHA, assesses how the child volitionally uses their hands in daily age-appropriate skills. It is excellent for specific goal setting, especially when you are doing constraint therapy and want to see improvement in bimanual hand use. It requires certification and extra training.

- Hand use in daily tasks

- Shriners Hospital for Children Upper Extremity Evaluation SHUEE (Davids et al., 2006)

- Video-based assessment for children ages 3-18 with hemiplegic CP

- Measures spontaneous use of affected hand, examines dynamic positioning, and gathers details on grasp and release

- Requires specialized training

The SHUEE (Shriners Hospital for Children Upper Extremity Evaluation) also looks at daily hand use, unilaterally or bilaterally. It is video-based, and it does require special training. It is a good outcome measure that provides a good look at how they use their hands.

- Hand use in daily tasks

- Melbourne Assessment-2 (Randall, Johnson, & Reddihough, 1999)

- Measures quality of movement in the affected UE for children ages 2.5-15yrs with hemiplegia

- Sensitive to change following OT intervention

- Requires specialized training

One more is the Melbourne Assessment-2. It measures the quality of movement in the affected arm and is a good outcome measure. It requires special training as well.

These assessments may guide your intervention, especially if looking at specific things.

- Functional use of vision

- Clinical observation of child's visual attention, tracking, and scanning

- Use high contrast if minimal response initially

- Formally measured by obtaining a Cortical Visual Impairment (CVI) Range (Newcomb, 2010)

- Requires specialized training

- Identifies child's current functional range and activities to work on to progress to subsequent levels

Many children with CP have what we consider to be cortical visual impairment. Their eyes are fine, but their brain impairment is impacting what they perceive. You can get a Cortical Visual Impairment Range, which does require specialized training. It is generally through a developmental ophthalmologist, and they have therapists that do those as well. It is helpful to know if a child has a vision issue to determine if that is why they are not engaged with me or if I need to adjust my treatment strategies.

OT Eval: Participation

- Participation is our ultimate goal! (not impairment-reduction)

- Occupational profile and family interviews can reveal areas of participation that can be added, expanded, or supported

- Familiarity with local resources is extremely helpful

- Local organizations, adaptive sports, support groups

Lastly, let's look at participation. Participation is our ultimate goal and my main point. We want to look at the body structure and function impairments because we want them to be able to do more things that they need to do, want to do, and are expected to do. Ultimately, we want them to be able to participate with their peers. We must look at all the things that may be going on in the body to prevent or treat them. Intervention can include a splint or a change in positioning to increase their participation in activities like handwriting, kicking, jumping, getting dressed, and social activities with family, school, and peers.

Participation is where we want to aim our intervention. If we want to aim our intervention there, we have to assess for it. There are many OT assessments, but I want you to look at the whole picture. We can look at their body to see when movement veers from the norm and what is going on in their daily life. We can use the Occupational Profile and a family interview to reveal areas of participation or bring up ideas of things that they want to do.

- Participation goals

- Canadian Occupational Performance Measure COPM (Law et al., 1998)

- Identifies client-centered occupational goals

- Detects change in self-perception (or caregiver perception) of performance over time

- Can be used with clients over 8 yrs or caregivers of those younger

We may be able to link them to resources, local organizations, and adaptive sports groups. We want these kids to engage with their peers. The COPM, the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure, is an interview assessment that helps identify areas a family wants to work on and helps a therapist set occupational client-centered goals. It lets the child or the family rate their performance and satisfaction on those things at the beginning to be used as an excellent outcome measure. For example, a family may want to go to a movie theater and have the child sit in a seat, not in a wheelchair. The COPM can help identify what is essential to the child and their family instead of just trying to improve the range of motion at the joints.

- Participation difficulties

- ABILHand/ABILHand-Kids Questionnaire (Arnould, et al., 2004)

- Assesses bimanual abilities by interviewing child or caregivers about the perceived level of difficulty in daily bimanual tasks

- For children with CP ages 6-15yrs

- Free online: https://rssandbox.iescagilly.be/abilhand-kids.html

The ABILHand-Kids Questionnaire assesses the perception of the child and caregiver on how the child is doing with their hands in age-appropriate tasks like playing a recorder or other instrument or getting stuff from a locker. It is also free and online, but it can help dig into some more hand-related impairments and goals.

Take-Home Messages

- CP can be identified in babies as early as 3-6 months

- OTs can watch for early signs, provide additional evaluation, make appropriate referrals, and discuss early findings with caregivers

- There is a lot of prognostic data on toddlers with CP, and this information benefits caregivers

- Evaluations for kids with CP should address body structures & functions, activity abilities & limitations, and participation

CP can be identified as early as 3 to 6 months old. I encourage you to watch for those early signs and provide additional evaluation if needed. Discuss some of those early findings with families as it is essential and valuable. There is a ton of prognostic data on little ones with CP, and this information benefits caregivers. I have had many families grasping at hope using hyperbaric oxygen and other treatments that were going nowhere. I have to honor what they want to do, but it is also essential to share that a level (like a GMFCS V or a MAC 5) is not what we are trying to change. However, these are all the things that we can change. We can give your child access and the ability to do many things, even if we are not improving their voluntary muscle control. We evaluate body structures and functions to assess activity abilities and limitations to support participation.

Please reach out if you have any other questions or comments. I would love to hear from you.

Questions and Answers

Why do we need to know what level they are? How does that affect the intervention?

It is essential to know the level as there is so much good information on a MACS level that will guide you.

When bringing up CP with other therapists, do I come across pushback?

That is a good question. I am not on the CP specialty team in my hospital, but the team has so much information, and the evidence is clear that families want to know early. It was weird in the past because some people said, "Do not say cerebral palsy." There was pushback and fear. I have been a therapist for 20+ years. I have gotten to a point where I committed myself so that I would not be dishonest and cover things up. I am not going to mislead a family. My experience has helped me continue to do so.

In pediatrics, at what age do we work with kids?

This is an interesting question. Kids with CP rarely became adults with CP years ago, but now they do. They live longer and are doing more things. There are not a lot of adult doctors or caregivers who are comfortable treating CP. At Cincinnati Children's, we treat adults with cerebral palsy and other pediatric conditions, like congenital heart issues, spina bifida, cystic fibrosis, and other issues. In fact, I treat a 58-year-old woman. I do not see her on an ongoing basis, but I see her when she needs my care.

References

Please refer to additional handout.

Citation

Sharp, P.(2022). Cerebral palsy review: Clinical presentation, evaluation, and diagnosis. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5531. Available at www.occupationaltherapy.com