Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Fine Motor Skill Development: A Neuroscience Perspective, presented by Kathryn Hamlin-Pacheco, OTR/L, ASDCS

*Please also use the handout with this text course to supplement the material.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to analyze the brain’s contribution to fine motor skill development.

- After this course, participants will be able to apply neuroscience related to motor skills to support the development of fine motor skills in children.

- After this course, participants will be able to examine fine motor skills as they relate to a “neural model” in the brain.

Introduction/Translating Neuroscience into Everyday Practice

Thank you all so much for joining me today. I'm truly excited to share this information with you, and I appreciate you taking the time to be here. With that, we're going to jump right in and get started.

You'll find the disclosures, limitations, risks, and learning outcomes in your course resources. They're all there for your reference.

I like to begin this talk by introducing myself as a translator of neuroscience because that's how I've truly come to understand my work. So often, when we, as clinicians, take professional development courses on neuroscience, they're taught by neuroscientists who are in labs, conducting studies, writing articles for peer-reviewed journals, and looking at the brain every single day. Their work is incredible and vital, but what we will explore today is a bit different. As an occupational therapist, I view myself as a translator of that information.

I don't have an M.D. or a Ph.D. I'm not in a lab looking at brains every day, but I work with children and their families every single day. I'm using this neuroscience in practice, and I hope that today, we can have a really meaningful conversation about the neuroscience of fine motor skill development and how we can apply it to our daily work.

Of course, when we, as clinicians, think about the brain and nervous system, and then discuss these concepts in a practical setting, we have to simplify things to some degree. We have to narrow our focus, and I've worked hard to do that today in a way that provides a holistic and informed conversation. Naturally, there's always both a risk and a benefit to narrowing our focus, so I've built some guide rails—or "safety rails," if you will—throughout the course.

You'll notice that almost every slide includes citations. These are here, of course, to give credit to the incredible scientists who developed the work we're discussing. However, you'll also see that I've referenced several neuroscientific textbooks in addition to peer-reviewed journal articles. These are particularly helpful because they do an excellent job of summarizing and breaking down complex concepts into digestible information. You'll see these references noted throughout the course.

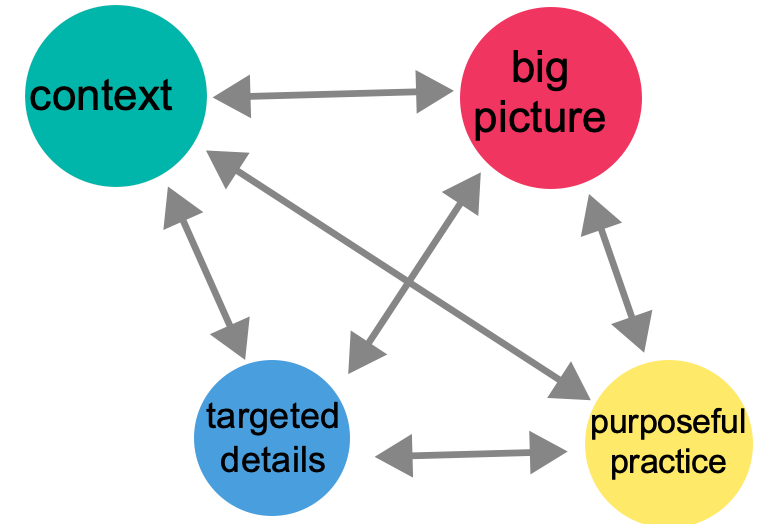

As I considered how to make this course cohesive, I created the framework in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Schematic of today's course.

Before becoming an occupational therapist, I taught elementary and middle school. This background in teaching and learning has profoundly influenced how I approach sharing information, and I've brought that experience to our presentation today. I've designed our time together to be a deliberate journey.

First, we will explore the targeted details of the brain and nervous system. We’ll delve into some of the nitty-gritty neuroscience, as I believe it's crucial for us as clinicians to have a foundational understanding of the brain. But as we do that, we’ll also step back to consider the big picture. After exploring the intricate details, we'll ask, "What does this all mean?"

Throughout our discussion, we'll keep the context of our practice—our kids and their families—at the forefront. As clinicians, we know that if this doesn't apply to the people we serve, it doesn't truly matter.

Finally, we'll focus on purposely putting this knowledge into practice. In the second half of the presentation, we'll explore concrete examples of how to apply this information to support our clients effectively. I wanted to share this roadmap with you because we are about to jump into some dense neuroscience. If it feels a bit intense, stick with me. Remember, we will look at it from different perspectives and, most importantly, get to the practical application of it all.

What Exactly Are Fine Motor Skills?

Now, with that said, let's jump right into the neuroscience of fine motor skills. Let's start by defining them. Fine motor skills are the skilled, precise movements of the small muscles in the body. We typically talk about the hands and fingers, including the oral and facial regions. Today, we'll focus on the hands, fingers, and mouth. These small muscles are uniquely innervated to support a high level of precision.

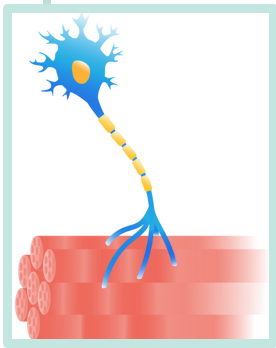

Here's our first major chunk of neuroscience: the motor unit. This comprises a lower motor neuron and its connection to muscle fibers.

Figure 2. An alpha motor neuron and muscle fibers to make up a motor unit.

We are going to unpack this a bit more. The signal for voluntary movement starts in your brain, traveling down to a lower motor neuron in your brainstem or spinal cord. From there, this information travels to the muscle fibers, directing them to contract.

Now, let’s consider the difference between gross and fine motor movements. When we look at the motor unit for large, gross motor muscles—like our glutes when we run—one lower motor neuron can connect to hundreds of muscle fibers. This allows for a strong, powerful contraction, but it lacks specificity. However, a single lower motor neuron may innervate as few as ten or even fewer muscle fibers for fine motor skills. This is where we get the precise and refined control for skilled hand movements. So, while the initial cue for movement begins in the brain, the intricate connections at the muscular level allow such precise control.

Where Does Voluntary Movement Start?

So, I posit that if fine motor skills start in the brain, then we, as clinicians, need to start in the brain to address those skills. This is exactly why I'm so excited to have this conversation with you today.

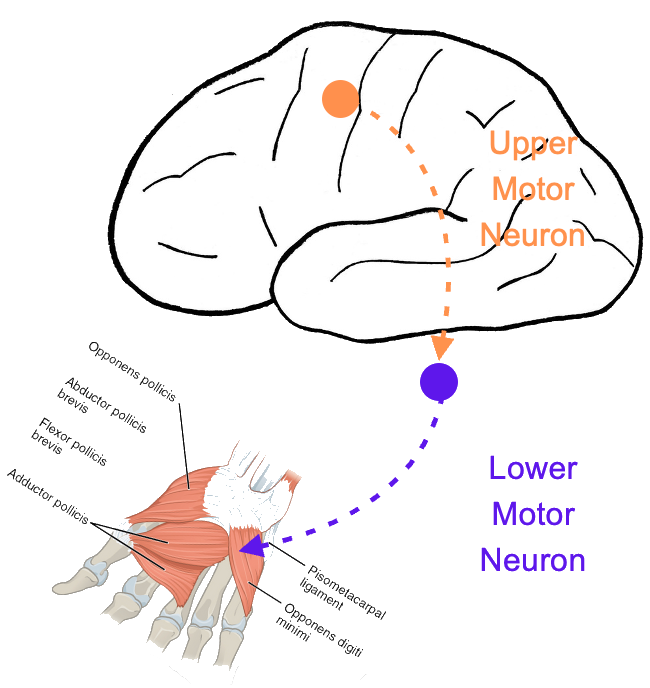

Now, to give you more information about those lower motor neurons, it's helpful to understand that the signal from the brain out to the muscles travels along what we call neural tracts. A neural tract comprises an upper motor neuron and a lower motor neuron.

Brain

Figure 3 shows that the upper motor neuron starts in the cortex of the brain.

Figure 3. Diagram of upper and lower motor neurons. (Click here to enlarge the image.)

The signal for voluntary movement begins in the cortex, the brain's outer, bumpy layer. The cell body of the upper motor neuron is located there, and its signal travels down its axon to the next neuron in the tract: the lower motor neuron. This lower motor neuron carries the signal out to the muscle fibers.

For our discussion today, we'll focus on two specific neural tracts. First, there's the corticospinal tract. You can break down the name: 'cortico' refers to the cortex, and 'spinal' refers to the spinal cord. The upper motor neuron starts in the cortex and synapses with the lower motor neuron in the spinal cord, bringing the signal to the muscles of the hands and fingers.

The second tract is the corticobulbar tract, which is responsible for facial and oral movements. Again, let's break down the name: cortico is the cortex, and bulbar refers to the brainstem. The upper motor neuron connects with the lower motor neuron in the brainstem—sometimes called the "bulb" due to its shape—to send signals to the muscle fibers of the face and mouth.

Main Cortical Areas

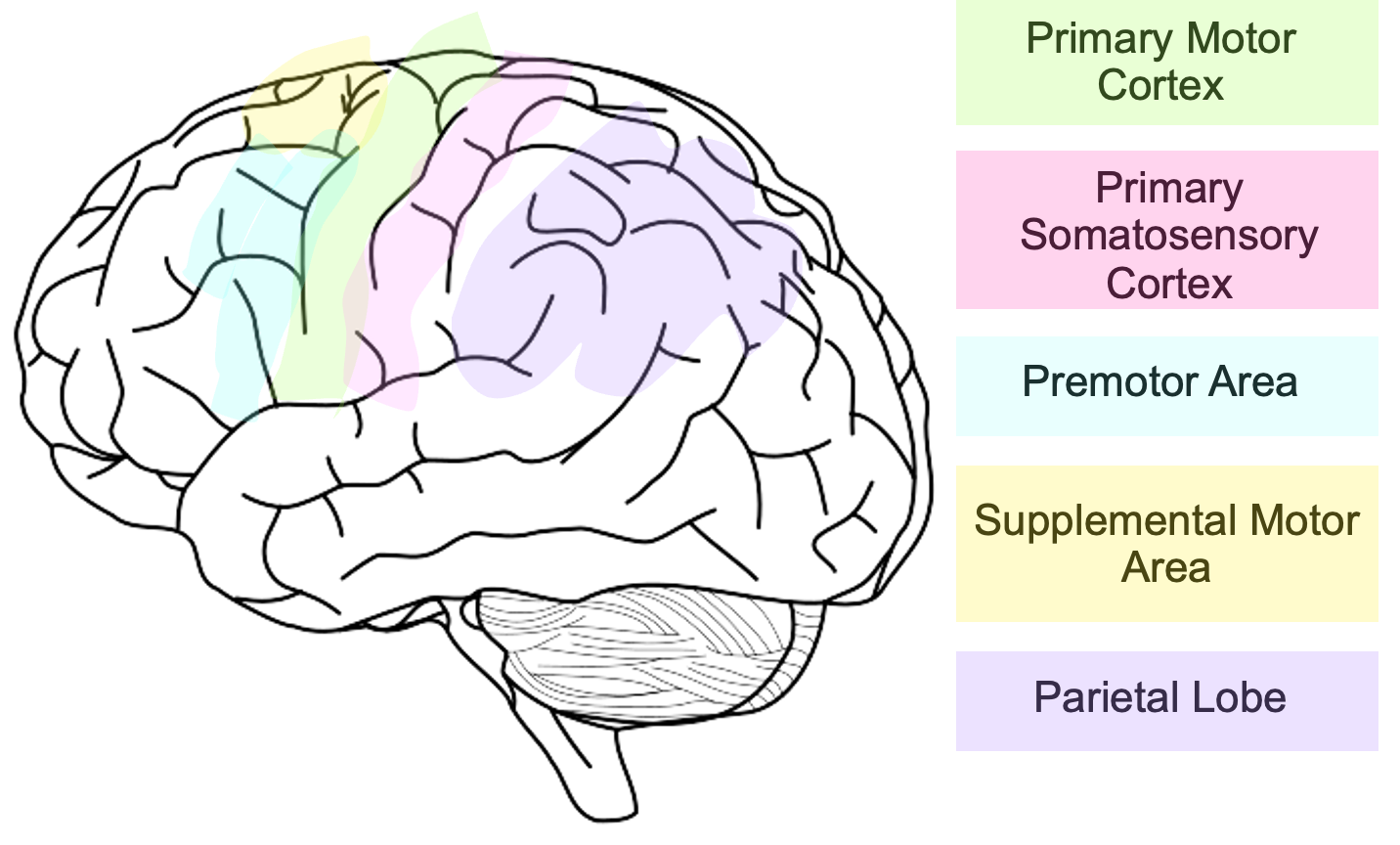

I want to focus on five specific cortical areas and discuss their contribution to fine motor skills, as seen in Figure 4.

Figure 4. The main cortical areas that control fine motor movement. (Click here to enlarge the image.)

The first key area we'll discuss is the primary motor cortex, which makes sense, since we're talking about motor skills. It's located within the frontal lobe, and its neurons are responsible for signaling voluntary movement through large, direct pathways.

Clinical observations confirm that these pathways are direct. For example, during neurosurgery, very little electrical stimulation to the primary motor cortex elicits hand and finger movement. Stimulating other areas of the brain that also signal for movement requires significantly more energy. This shows us that the connections from the primary motor cortex are indeed powerful and direct.

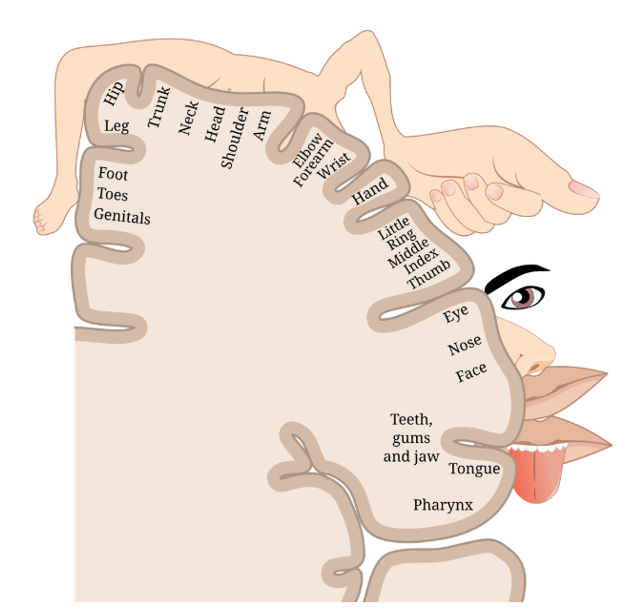

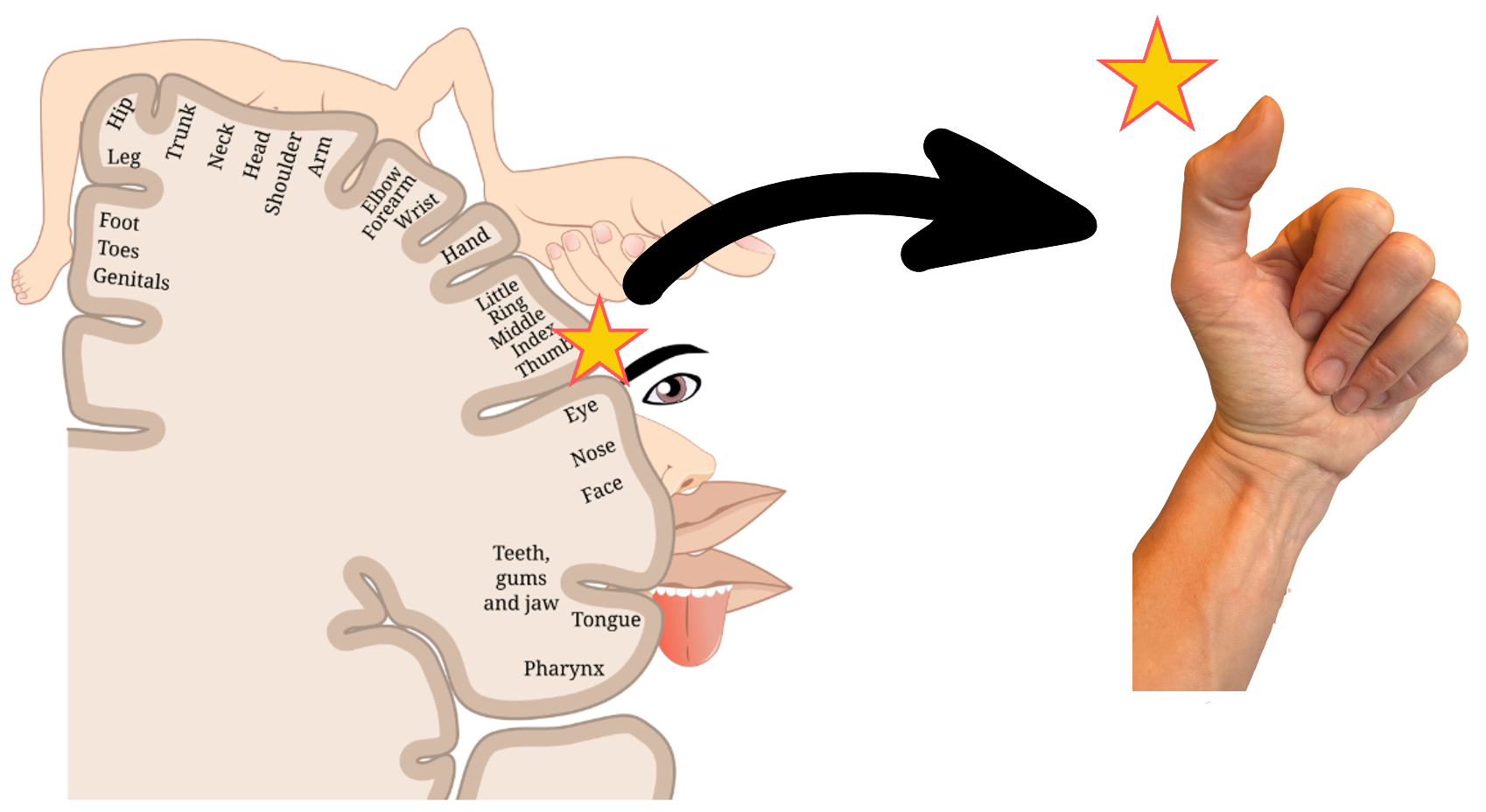

There is also something quite special about this brain area: it is somatotopically organized, a concept you may know by the term "homunculus." This means that the primary motor cortex is mapped so that specific parts of this brain region correspond to and signal for movement in specific parts of the body. My next slide shows this more clearly, as this is a slice of the homunculus (Figure 5).

Figure 5. A slice of the homunculus. (Click here to enlarge the image.)

What you're looking at is a slice of the brain's homunculus. While all our brains are similar, we do have individual differences. If you look to the left side of the screen, you'll see a small bump in the primary motor cortex that contains the areas for all of the fingers and the thumb.

Within that small bump is a dedicated area specifically for the thumb. When a neuron in that particular spot of the primary motor cortex activates, it sends a signal to activate and move the thumb (Figure 6).

Figure 6. The area of the cortex indicated on the homunculus that controls the thumb.

The primary somatosensory cortex is located next to the primary motor cortex and is part of the parietal lobe. This area receives tactile and proprioceptive information—the sensations you feel on your skin and the awareness of your joints—playing a significant role in interpreting and then sending that information to other parts of the brain.

Like the motor cortex, the primary somatosensory cortex is also somatotopically organized, or mapped as a homunculus. It works in a reverse way: while activating a motor neuron causes movement, if I were to touch your thumb, that tactile signal would travel directly to the specific area of your primary somatosensory cortex that corresponds to it.

Sensation informs movement, and we will truly unpack that idea. But I'd like to start with a surprising fact that truly changed my perspective as a clinician: about 40% of the fibers in the corticospinal tract are actually comprised of fibers from the somatosensory cortex. I used to think of it simply as the motor cortex sending information out and the somatosensory cortex receiving information in. While that's largely true, the somatosensory cortex actively feeds into the motor tracts we're discussing.

To explain why this is important, think about how these tracks help us filter information. Imagine you’re taking notes but have a Band-Aid on your finger. That band-aid sends tactile information to your somatosensory cortex, but that sensation isn't essential for guiding your writing. This is one way the brain can block out non-essential information. At the same time, other somatosensory data—like our body's position, the rate of change of that position, and the force of our muscle contractions—is fundamental and is integrated into our motor plans.

Understanding that the primary motor and somatosensory cortices work together closely is essential. They send information to other brain areas, contribute to the same motor tracts, and share information directly. The brain does not do anything by accident; it intentionally uses its limited space. The fact that these two functionally related areas are right next to each other shows how tightly they work together. Their somatotopic organization reflects each other's, ensuring much information is shared and coordinated. Remember, we will apply all of this to our practice, so if you're intrigued but not sure what this means for your clients, hang on—we'll get there.

The next area of the cortex I want to discuss is the parietal lobe, which houses the somatosensory cortex. The parietal lobe is really an integrator of information. It takes in somatosensory, auditory, visual, and vestibular information, processes it, and then sends it forward. The parietal lobe helps us understand what is happening around us and inside our bodies. It doesn't directly signal for movement, but it sends that integrated information to the brain's motor areas.

The first of these motor areas is the premotor area. The premotor area receives that integrated sensory information from the parietal lobe and uses it to create a movement plan. It activates just before a movement happens and plays a vital role in movements that require visual guidance, such as reaching to pick up a coffee cup or a flower.

Figure 7 shows a coffee cup and a flower.

Figure 7. A cup on a table.

Imagine sitting here and seeing a cup of coffee or water. The information that there's a cup in front of you is sent to your parietal lobe. While the parietal lobe can't signal for movement directly, it can send that visual information to the premotor area, creating a plan for reaching and grasping the cup.

The supplemental motor area is next to the premotor area; these two regions work very closely together. While the premotor area primarily involves movements based on external, visual cues, the supplemental motor area plays an important role in selecting movements based on internal cues. For example, if you suddenly feel thirsty, that internal sensation gets processed in the brain. It can then be sent to the supplementary motor area, a leading player that generates a plan for that movement.

Cerebellum

The cerebellum is the last area of the brain I want to discuss before moving on. While not part of the cortex, it plays such a crucial role in fine motor coordination that it's essential for our conversation.

The cerebellum is responsible for integrating, regulating, and coordinating movement. It does not directly signal for movement itself but sends information to the areas of the brain that do. You can think of it as "previewing" a movement plan and then updating it based on a live feed of proprioceptive information. For example, when it receives a motor plan, it can assess, "That's a great plan, but my body is currently positioned like this," and then make real-time adjustments.

Here's my best example to put that into work, shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8. Opening and closing scissors.

Imagine your goal is to cut a piece of paper, and your motor plan is to open and close the scissors as you move across the paper. When this plan is sent to your cerebellum, it uses the live proprioceptive information from your hands to refine the movement. If your hands are currently holding the scissors in an open position, the cerebellum will adjust the initial signal so the first movement is to close the scissors. If your hands are already closed, the cerebellum will ensure the first movement is to open them. This is how the cerebellum helps us refine and inform our movements in real-time. The biggest takeaway is just how intricate the brain is and how many jobs it does simultaneously.

Teamwork

For the execution of skilled and precise motor movements, rapid and organized information sharing among all of these brain areas is essential. Considering how much the brain has to do at once is truly impressive.

Learning As Building Mental Models

According to Stanislas Dehaene, to learn is to form an internal model of the external world. In the context of sensory-motor skills, this translates to the concept of a "body scheme" or "body schema". This is a neural representation of the body used to guide motor activity and is heavily dependent on proprioceptive and tactile sensory input. Jean Ayres emphasized the importance of this body scheme as the foundation for praxis and its relationship to somatosensation.

Mapping studies in humans and other primates show that complete representations of the body are housed within the somatosensory cortex. The motor cortex also appears to be a mapping of something deeper, related to "ethologically meaningful behavior". This suggests that the brain is not simply organized to activate a specific muscle but rather to stimulate a specific movement or behavior. For clinicians, this means our strategies should be organized around meaningful movements and purposeful behaviors, as the brain is organized to understand meaning.

I like to conceptualize this with an analogy: the hand. If a child's neural model of their hand is like a winter mitten—where all the fingers work together in a gross, unrefined manner—they will struggle with tasks that require precision. If we can refine that mental model from a "mitten" to a "glove" or a bare "hand," we can improve their fine motor skills. This is particularly empowering because it means we can help a child develop a model of their own unique body, maximizing their personal function.

Building Mental Models To Target Fine Motor Skills

The key question is, can we actually change this mental model of the body? The answer is yes, because mental models are malleable. Early work by Jon Kaas and Michael Merzenich showed that the somatosensory cortex can reorganize after a nerve lesion or amputation. Initially, the corresponding cortical region becomes unresponsive, but within weeks, it becomes responsive to stimulation of neighboring skin regions. The brain takes its real estate very seriously and will re-map unused areas for new functions.

Cortical representation also changes in response to sensory and motor experiences. In a study with owl monkeys, heavy and purposeful use of digits 2, 3, and 4 in a trained task led to an increase in the size of the corresponding neural "maps" in the somatosensory cortex. These changes, or "functional remapping," have also been demonstrated in the visual, auditory, and motor cortices and can occur not just in the cortex but also in subcortical areas like the thalamus and brainstem. This means that we can, in fact, change our clients' neural mapping of their body.

More recent evidence further supports this. A multisensory conflict study showed that mismatched visual and tactile stimulation could distort the body scheme in a short period of time, leading participants to misjudge their forearm's center point. Another study trained participants to use a robotic "Third Thumb" over five days, resulting in improved motor control and changes in the brain's augmented hand's motor representation.

So, how do we build a mental model of the body? Since our body schemes are housed in the motor and somatosensory cortices, the way to change them is to activate the neurons in those areas. As the well-known principle states, "Neurons that fire together, wire together". Passive learning or information will not create lasting changes. This is where the practice of Sensory Integration comes in, emphasizing that you cannot fully separate sensory and motor functions as they are intricately linked.

A. Jean Ayres noted that sensory input, especially from the skin and joints, helps to develop the brain's model of the body as a motor instrument. Her theory proposes that active engagement in individually-tailored sensorimotor activities promotes adaptive behaviors through neuroplastic changes. The nervous system changes in response to experience, and every time the brain signals a movement, receives sensory feedback, and potentially changes the output, the brain is learning and reorganizing. Evidence supports this connection, as deficits in proprioception have been found in 90% of children with somatodyspraxia. Similarly, children with handwriting difficulties show deficits in both praxis and tactile perception.

Translating the Neuroscience into Practice

At this point, we will take what we've learned and start to apply it to practice. We'll examine three key tenets of intervention from Ayres and compare them with four of Dehaene's Pillars of Learning to determine how we can develop a more effective mental model for our clients.

Active Engagement

The first tenet is active engagement. Ayres taught that a child must actively elicit purposeful actions to develop motor skills. Without it, they miss a crucial part of the sensory-motor loop, resulting in a mental model that lacks essential information. This makes us question approaches like a hand-over-hand technique. While a child may see and feel the paper being cut, their brain is not sending the signal for the movement, which means they are missing the motor part of the loop. Instead of relying on hand-over-hand, we should shift our strategy to allow the child to send the signal for the movement, even if the result is a less-than-perfect cut.

Another perspective is to think back to the beginning of this discussion, when we were discussing the somatosensory cortex's contribution to those motor tracts. If I have my hand on the back of the child's hand, I'm providing tactile information that may be confusing. Because if we're doing a great job of modulating that tactile input, the brain can say, "Oh, that sensation from the back of my hand isn't a big deal". However, if that child is having a hard time integrating or modulating that sensory input, their brain may not be able to sort it out. So, then, the feeling of your hand on the back of their hand is going to add to their model.

One of the reasons I love this approach to developing a mental model of the body is that I am helping this child develop a mental model of their own body. We can discuss a hand with all five fingers, but we also have children who don't have all five fingers. Their hand may have two or three fingers, or it may move differently or have a contracture. I want to help this child understand their own personal hand, develop a model of their hand, fingers, and how they work, as well as their mouth, face, and how they function. Because I don't need them to understand how to use just anybody's hand, I want them to know how to use their own hand and use it in the most successful way possible in their everyday life. That's another reason I love this approach: it's because I'm really saying, "How can we maximize your personal function and your very own body?"

The Just Right Challenge

The second tenet is the Just Right Challenge. This is a task that requires a child to work at the edge of their capabilities while still facilitating an active response and ensuring success. It supports motivation and promotes success.

A great example of this is a little boy with a diagnosis of autism whom I worked with. He was initially disengaged with limited purposeful play, so our first goal was to find what lit him up. We discovered he was motivated by swinging and the words "go" and "stop". My brilliant SLP colleague and I introduced an AAC device with large icons for "go" and "stop". He was so motivated by the effect his selections had on the swing that he was willing to use his hands to select the icons, which was at the edge of his fine motor ability. Without any prompting, he began isolating his fingers to select the icons, as it made him even more successful. When we met him at his just-right challenge, his fine motor skills naturally increased.

Adaptive Motor Responses and Error Feedback

Ayres described adaptive responses as central to praxis intervention, as they are purposeful actions that are successfully achieved and are inherently organizing for the brain. This concept is similar to Dehaene's pillar of error feedback. Dehaene states that "making mistakes is the most natural way to learn" because the brain learns when it perceives a gap between what it predicts and what it receives. When errors are detected, adjustments can be made.

Even when a movement is correct, learning occurs. For example, when you play cornhole, your brain predicts a certain probability of success before you toss the beanbag. When you make the shot, your brain learns that with that specific force and direction, the probability is 100%. Your brain updates its model based on the discrepancy between your prediction and the outcome. The brain is constantly making predictions based on its mental models to work as efficiently as possible. When the input doesn't fit the prediction, the brain passes it to the next level of processing, which is how we learn.

This is especially relevant for oral motor skills. The SOS Approach to Feeding white paper notes that using non-food items in isolation doesn't allow a child to independently acquire the skill complexity necessary to eat textured foods. This is because non-food items, such as chewy items, are predictable; they don't change in shape or consistency as the child chews. After the first few bites, the brain learns what to expect and stops paying attention, limiting learning. In contrast, real food is constantly changing shape and texture, providing a wide array of sensory inputs that keep the brain attentive and actively build a mental model of how to manage it.

Daily Rehearsal and Nightly Consolidation

The final pillar of learning is daily rehearsal and nightly consolidation. The principle of neuroplasticity tells us that we need to activate specific neurons and build strong pathways through repeated, meaningful connections. Learning is maximized with repeated daily practice rather than cramming into one session. This means that parent and caregiver coaching for daily carry-over is critical, as we often only see children once or twice a week.

Repeated practice transitions a new skill from the parts of the brain that require conscious attention to more efficient, unconscious subcortical circuits. This process is called consolidation, and it occurs while we sleep, making sleep a crucial component of skill acquisition. During sleep, learning is transferred into a more efficient part of our memory. Therefore, as practitioners, it's important to ask parents about their child's sleep, as sleep difficulties are highly associated with some disorders and may be a reason why skills aren't coming together.

Let’s Look at More Evidence

Enriched environments that offer a variety of items and opportunities for active engagement have been shown to initiate and contribute to lasting functional changes in the brain. We can ask parents and caregivers about their child's access to different toys and their typical activities to ensure they have opportunities for daily practice.

A systematic review of school-based occupational therapy interventions found that sensorimotor handwriting interventions addressing isolated component skills, such as kinesthesia, have "no effect on handwriting legibility." This highlights the importance of not just performing a motor task in isolation, but instead ensuring that our practice is purposeful and involves the full dynamics of the targeted skill. We must remember that the motor cortex is organized based on function and behavior, not just specific muscles.

A Few Thoughts on Autism

Autism has been conceptualized as a tendency to construct very specific mental models and have difficulty generalizing those models to new information. This is crucial to consider when applying the mental model approach to our autistic clients. While we can still take a holistic approach to build a robust mental model of the body, we may also need to provide more targeted and specific practice to help them generalize that model to a particular skill, such as buttoning buttons. This is where a clinician's informed reasoning can make our practice truly meaningful.

Summary

I hope this information was helpful to you and your practice. Let's now move to questions.

Questions and Answers

Does tracing actually hinder a child's ability to learn letters because they become reliant on the visual lines?

It’s a valid concern. If a child only ever traces, they aren't practicing retrieval—the ability to pull the shape of the letter from their own memory. Instead, they are simply following a visual "road map." This can prevent the brain from fully "locking in" the motor plan (the sequence of movements) needed to write the letter independently.

References

See additional handout.

Citation

Hamlin-Pacheco, K. (2025). Fine motor skill development: A neuroscience perspective. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5834. Retrieved from https://OccupationalTherapy.com