Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Occupational Therapy's Role In Sustainability, presented by Magan Gramling, OTR/L, CLT, CTP, CFNIP.

*Please also use the handout with this text course to supplement the material.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to analyze the role of occupational therapy in the current climate crisis through a sustainability lens.

- After this course, participants will be able to differentiate current occupations in individuals, groups, and communities for support or possible harm to the environments they engage with.

- After this course, participants will be able to analyze sustainable occupations to increase individual, group, and community wellness.

Introduction

Thank you. It’s great to be here. I’m genuinely excited about this opportunity to share and learn together.

The goals for this webinar are multifaceted. First, we will develop a deeper understanding of climate change and how it impacts our health. This understanding is foundational, as it sets the stage for our next focus: exploring the concept of sustainability. We will look at why sustainability is not just an abstract ideal but a viable and practical intervention for addressing climate change and managing its health effects in today’s world.

From there, we will bridge these concepts to our unique role as occupational therapy practitioners (OTPs). We’ll analyze current occupations and evaluate whether they are sustainable or unsustainable. This is not just an academic exercise—it’s about applying this knowledge meaningfully to the groups and communities we serve. We will look at our spheres of influence—micro, meso, and macro—and consider how each of us can leverage our roles to promote wellness, both personally and professionally.

Finally, my hope is that by combining this understanding, evaluation, and analysis, we can move toward educating and empowering our communities. Together, we can create new occupations that are not only meaningful and enjoyable but also sustainable, ensuring that the work we do today contributes to a healthier future for all.

About Me

I’d like to share a little about myself and my family. I earned my bachelor’s degree in psychology and went straight into a master’s program in occupational therapy. After working in the field for a number of years, I decided to return to school to pursue my doctorate, which has been an incredibly rewarding journey.

Over time, I’ve also earned several certifications that have allowed me to expand my practice and better serve my clients. These include certifications in lymphedema management, mastectomy fitting, and, more recently, a trauma-informed practice certification. In addition, I became a Functional Nutrition Informed Practitioner, which has added an important dimension to the way I approach holistic care.

Course Description

There is a growing body of research in the literature addressing climate change and public health, including within the field of occupational therapy. However, very little has been done to create education around practical ways to integrate this knowledge into our daily lives and professional practice. In 2023, Taf published an article noting that OTPs focus on an adaptation mindset regarding occupational engagement and performance. In other words, we often approach climate change by helping clients adjust to its impacts. While this adaptation is undoubtedly necessary, the article emphasizes that we as occupational therapy practitioners must also address prevention, mitigation, and resilience. This broader approach is the driving purpose behind this webinar.

Glossary of Terms

When we look at the glossary of terms for this topic, some of these will likely feel familiar, while others may be new and worth reflecting on more deeply. The definitions make it clear that sustainability presents an occupational justice issue, especially when we think about future generations. When considering occupational justice, we see how climate change can directly impact wellness-sustaining activities. For instance, changes in floodplains or the increasing frequency of heat waves in certain regions can disrupt the ability to engage in everyday occupations.

A 2020 article described how people today have developed what the author called “occupational desires,” which have contributed to the destruction of ecosystems. This author introduced terminology that frames opportunities for individuals and communities regarding their doing, becoming, being, and belonging, while simultaneously fostering concern for and relationships with animals, plants, and the broader natural world. Interestingly, the article highlighted how Scandinavian countries have taken these ideas seriously, even enacting laws that protect the rights of natural environments and other living beings. It underscored that this is an issue of occupational justice, as the occupations of today’s humans are risking the ability of future generations to participate in essential occupations, such as growing food, feeding themselves, and accessing clean drinking water.

One term I find people are often less familiar with is “ecopation,” which essentially means engaging in sustainable occupations. It’s a valuable concept to carry forward, as it encourages us to consider how our actions relate to our larger environment. This includes being mindful of things like our carbon footprint and water footprint. Our carbon footprint reflects the greenhouse gases we emit in a year, and this can be examined at multiple levels—personally, professionally, across communities, and globally. Water footprints can become quite complex, but for this presentation, I am focusing on direct and indirect blue water use. This refers to surface water used in creating products or simply the domestic water we rely on for drinking and other daily needs.

Would you like me to make this flow even more like a live presentation script, with smoother transitions and conversational cues for engagement? Or keep it in a polished narrative style for written material?

The Role of OT: OTPF 4

Occupational therapy has always placed a strong emphasis on the role of environments. This is a foundational concept we all learned in OT school—that the environment is an essential part of the puzzle regarding supporting engagement and performance. We examine how individuals interact within their environments, whether that involves physical surroundings, geographical factors, or even climate-specific conditions. This also includes addressing human-caused events that shape or disrupt those environments.

The Occupational Therapy Practice Framework (OTPF) explicitly provides examples that relate to these ideas. For instance, it highlights how high levels of air pollution might force a person with lung disease to remain indoors, directly limiting their engagement in meaningful occupations. Another example focuses on air quality, noting the increased incidence of respiratory disease in communities near industrial districts. These examples make it clear that our professional framework already acknowledges the impact of environmental conditions—including those connected to climate change—on participation in daily life. This reinforces that engaging with these issues is not outside our scope but rather integral to our role.

The Role of OT: AOTA Policy E.16

Our national organization for occupational therapists, occupational therapy assistants, and OT students has taken an important step by releasing a policy known as E16, which specifically states its commitment to sustainability and addressing climate change. When I came across this policy, I was thrilled because it represents a significant acknowledgment of the role our profession can play in this global issue.

This policy frames climate change as an issue of environmental, occupational, and social justice. It emphasizes that the choices we make and the occupations we continue to engage in have profound effects, not only on our current well-being but also on future generations and marginalized communities who are disproportionately impacted. The policy includes specific language around occupational deprivation, connecting it directly to the consequences of climate change. This framing can serve as a call to action for all of us in the profession, encouraging us to engage more deeply with these challenges.

As we will explore later in the webinar, the effects of unsustainable occupations and climate change extend far beyond environmental concerns. They have a direct and tangible impact on our health, wellness, and the vitality of the communities in which we live and practice.

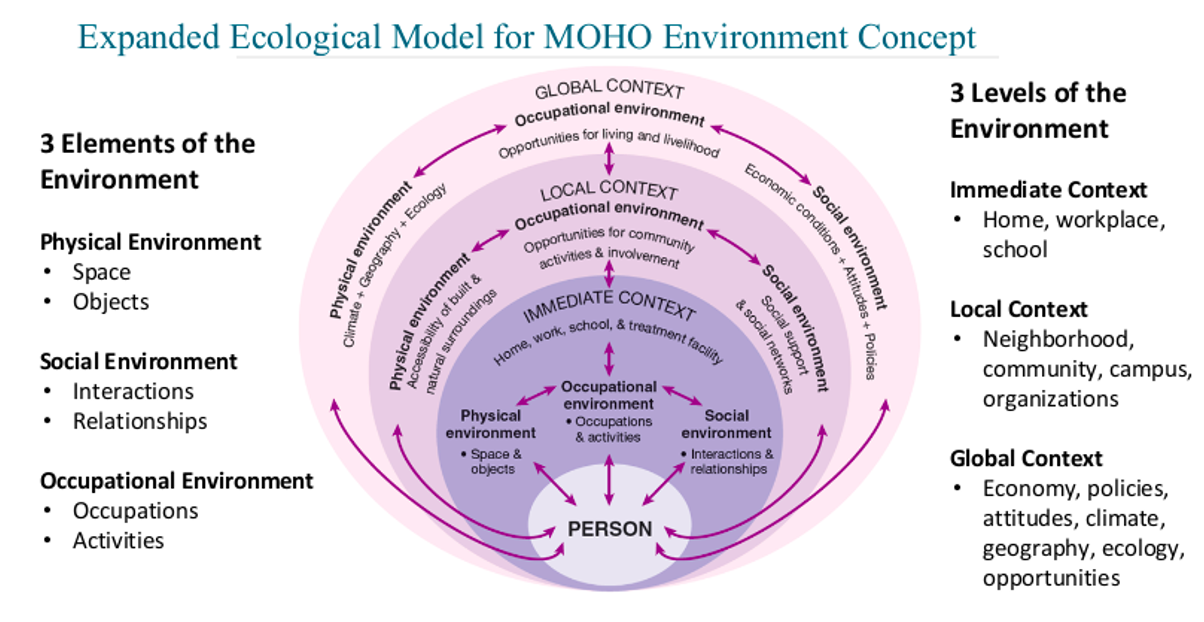

MOHO: Expanded Ecological Model for MOHO Environment Concept

I chose the Model of Human Occupation (MOHO) to discuss today because it provides a clear lens for understanding our role as OTPs in addressing these issues. For many of us, thinking about models and theory might feel like something we left behind in school, but models are incredibly valuable for practicing clinicians. They help define our scope, provide frameworks for assessment, and, in my experience, give us a shared vocabulary for communicating with other occupational therapy practitioners. They also serve as a reminder of the client-centered approach that is at the heart of our profession.

Most models in occupational therapy, including MOHO, recognize the environment as a key piece of the puzzle, connecting us intrinsically to the various contexts in which we live and work. The MOHO model was updated in 2024, and I had the pleasure of hearing Dr. Fisher, one of the authors, speak about the changes. As a Occupational Therapists for Environmental Action (OTEA) group member, I was particularly interested in how these updates make the model more dynamic. According to Dr. Fisher, the new MOHO emphasizes how the environment impacts individuals, their occupational participation, and how people can influence their environments.

This updated model, in Figure 1, reinforces that it is person-focused while recognizing multiple levels of context.

Figure 1. Expanded Ecological Model for MOHO Environment Concept. (Click here to enlarge the image.)

It highlights microenvironments, such as homes, schools, and workplaces; meso-level contexts like neighborhoods and communities; and macro-level systems, including government, healthcare policies, cultural attitudes, and broader opportunities or barriers related to marginalization, injustice, and deprivation. Within each of these levels, MOHO considers the physical aspects of the environment, such as the spaces we occupy; the social aspects, like our relationships and interactions; and the occupational environments that encompass our meaningful activities, habits, routines, and roles.

In practical terms, this means understanding how our global context—such as changes in climate—directly affects us and, conversely, how our actions impact it. It also means recognizing how local occupational environments, like our communities, and social global environments, like attitudes toward climate change or policies such as the AOTA’s E16 statement, shape how we live and work.

Dr. Fisher shared some powerful examples illustrating how these concepts translate into practice. For instance, she described residents of a group home petitioning to lower the height of recycling bins so that they would be accessible to those using wheelchairs. Another example involved adding visual signage to recycling bins for individuals who could not read, making sustainability practices more inclusive. These ideas reminded me of my own recent trip to Italy, where I saw well-organized recycling systems along the streets of Rome. They used clear labels and specific images to make it easy for anyone, including visitors like me who do not speak Italian, to sort materials properly.

Dr. Fisher also mentioned working with local food banks to repurpose food instead of sending it to landfills, which can help reduce methane emissions. Other examples included supporting clients who want to advocate for environmental issues, such as making signs or attending climate rallies, and even addressing complex cases where climate change directly affects a client’s livelihood. One example involved a woman with a spinal cord injury who used a manual wheelchair and could no longer reach her tailor shop due to flooding in her community. Her OT helped relocate her to a building where she could live and work without commuting through flood-prone areas, allowing her to continue her meaningful occupation.

I also want to mention another model worth exploring—the Canadian Model of Occupational Participation (CanMOP), developed in 2022. This model focuses specifically on occupational participation and has a strong land-based perspective. It highlights the experiences of Indigenous peoples, addressing the injustices and inequalities faced by these marginalized communities, and it explicitly connects climate to health and wellness. I find this model particularly compelling because of its emphasis on how occupation intersects with environmental and social justice.

How Did We Get Here?

How did we get to where we are today? When we think about the human timeline, imagining it as a 24-hour clock is helpful. Human beings have only been here for about two seconds before midnight. Homo sapiens have existed for a little less than 200,000 years, and up until about 10,000 years ago, humans lived directly in nature, practicing a nomadic, hunter-gatherer way of life. That shifted with the end of the Neolithic age, when people began settling into agricultural communities and moving away from that deep, daily connection with the land.

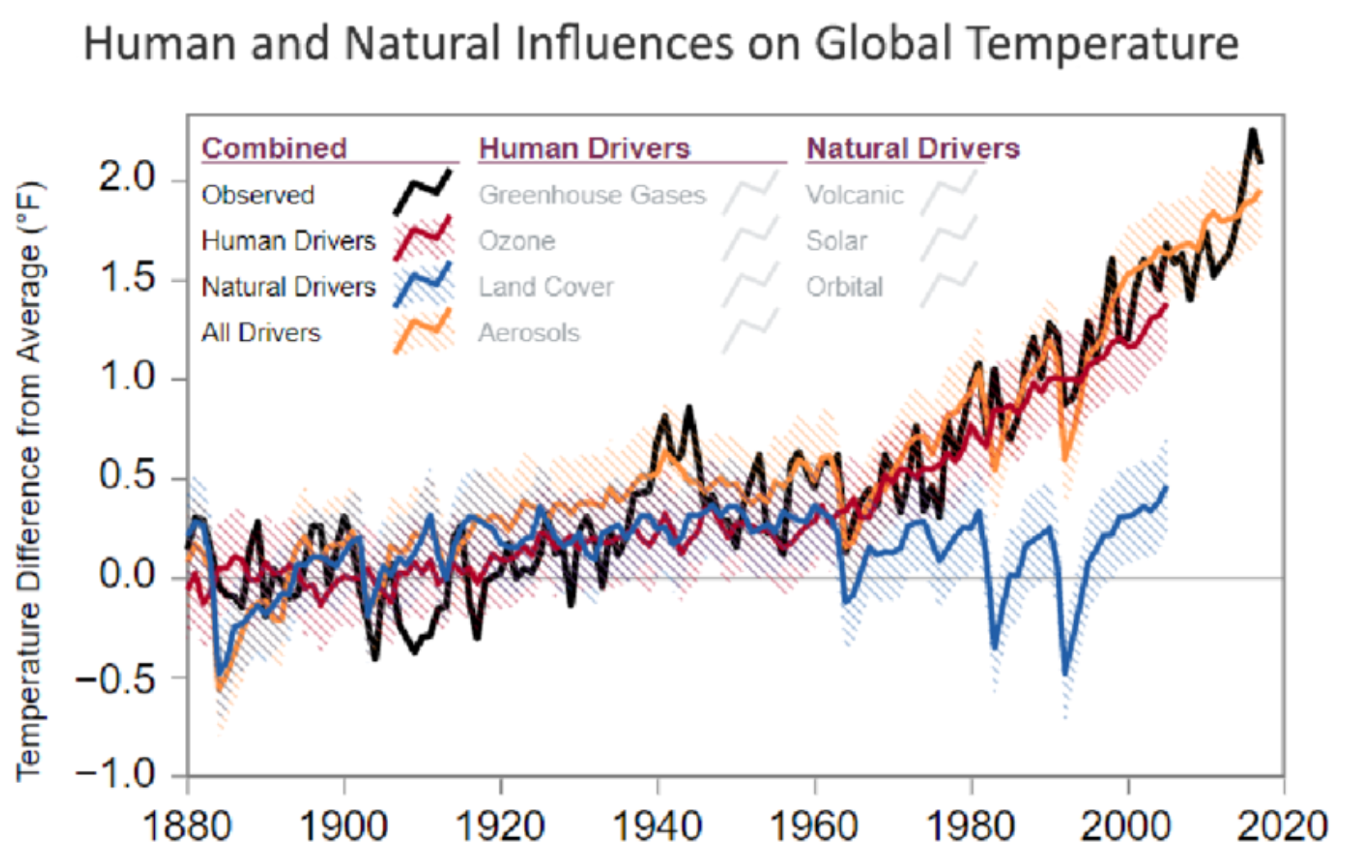

Fast forward to the late 1700s and early 1800s, and the Industrial Revolution completely transformed the planet in ways that are still unfolding, as seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Human and Natural Influences on Global Temperature. (Click here to enlarge the image.)

If we stick with the clock analogy, that monumental shift happened about a tenth of a second ago. Since then, our emissions of harmful greenhouse gases, like carbon dioxide, have increased by more than 40% compared to pre-industrial times. Today, concentrations of these gases in our atmosphere are higher than at any point in the last 800,000 years. In building big cities, we’ve also created what are known as urban heat islands—areas where the sun’s heat is absorbed and held by rooftops, asphalt, sidewalks, and parking lots rather than being balanced by trees and green space. These changes mean that soil, which naturally sequesters carbon, can no longer do its job when covered by concrete and other manmade structures.

How we view the natural world also plays a role in our current climate crisis. Influential Western philosophers like Descartes and Plato helped usher in an age of rationalization, framing humans as separate from—and above—the natural world. They argued that because humans are capable of metacognition, we are justified in using the Earth and its resources for our benefit. This marked a major shift from the deep spiritual connection to the land that characterized the lives of our ancestors and many ancient civilizations.

An interesting 2024 study by two occupational therapists explored this spiritual connection to nature, particularly through gardening and farming. Living and working on the land creates a reverence for its magnitude, connecting us to the food we grow and the animals we harvest. A 2019 study echoed this idea, finding that people often experience profound feelings of self-actualization and reverence when they feel the earth beneath their feet or the soil in their hands. These findings remind us that this connection is about survival, identity, and meaning.

Another layer to our disconnect from the earth lies in capitalism and colonialism. Walters (2022) argued that the climate crisis is fundamentally capitalistic, deeply intertwined with modern conditions of capitalism and their colonial roots. This connects to the concept of linear versus circular economies, which we’ll discuss shortly. Walters noted that those who benefit most from the status quo often do little to change it, and in some cases, governments even deny the realities of climate change altogether.

Building on this, a 2021 article suggested that as long as we view the world and its resources as something to be used solely to fulfill our every occupational desire—a term we discussed earlier—we will continue along this unsustainable path. Capitalism, built around taking what we need without consideration for waste or regeneration, fuels this pattern. A shift in mindset is necessary: taking only what we need and doing so with intentionality.

Another thought-provoking perspective came from a 2019 article that introduced the term ecofeminism, describing how ecofeminists aim to radically restructure economic, social, and political institutions. This framework draws parallels between the oppression of women and the exploitation of the more-than-human world in patriarchal cultures. While OTPs don’t have much work in this area, it represents an important intersection of justice, environment, and health that warrants further exploration.

These ideas—rooted in research, history, and philosophy—help us understand the forces shaping our current climate crisis and highlight the urgent need for new ways of thinking and doing.

Why It Matters

Why does all of this matter? As discussed throughout this webinar, climate change and sustainability fall within occupational therapy’s role and scope, and we have models and professional frameworks that support this work. But why is it so important to change what we’re doing? Simply put, if we don’t, we will continue to see an increase in sickness, disease, and disruptions to daily life.

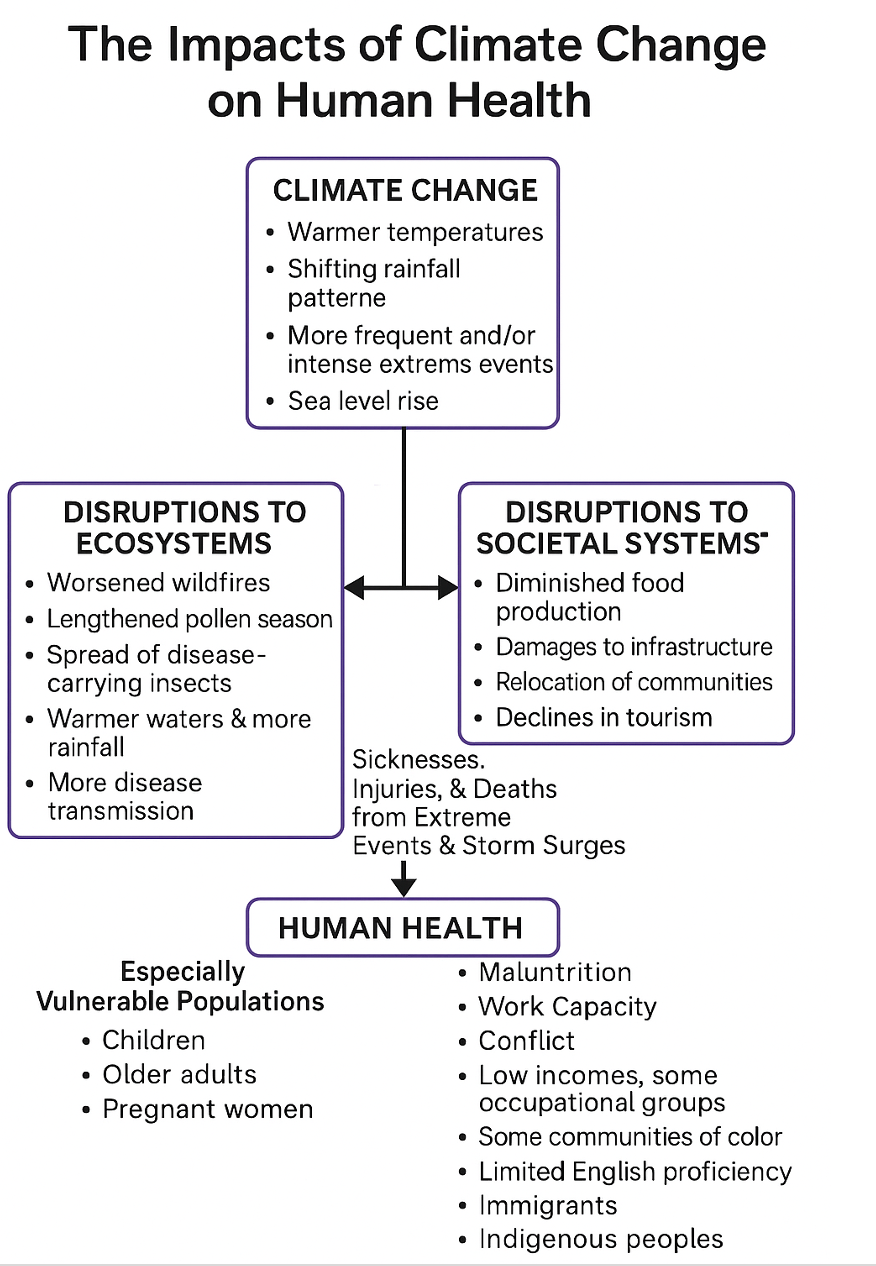

Figure 3 shows how the climate and our health are inextricably linked.

Figure 3. The Impacts of Climate Change on Human Health. (Click here to enlarge the image.)

When we look at long-term weather patterns, we see significant changes: rising global temperatures, shifts in rainfall, prolonged droughts, and the melting of glaciers. These changes disrupt the delicate balance of saltwater and freshwater systems, directly impacting oceans, lakes, and the food sources we rely on. Drought and ocean desertification caused by acidification not only threaten our food supply but also make communities more vulnerable to severe and extreme weather events.

Even at an individual level, these changes are tangible. I don’t know how many of you have struggled with allergies recently, but I had a conversation with a doctor about my child’s allergies, and she noted that the past few years have been some of the worst on record. This is linked to prolonged pollen seasons and the impacts of wildfires. Warmer temperatures also allow insects to thrive in regions where they previously could not survive, bringing with them new insect-borne and waterborne diseases. In other words, our human occupations directly fuel these changes, and we live with the consequences.

These health effects are not distributed equally. Marginalized communities—children, pregnant women, people with disabilities, older adults, and especially those in lower-income areas—are the most impacted. These populations often aren’t the ones engaging in the most unsustainable occupations, yet they bear the brunt of the fallout. Communities of color and Indigenous populations are also disproportionately affected. Think back to the example I shared earlier about the woman with a spinal cord injury who had to relocate her home and business because flooding made it impossible to commute in her wheelchair. This is a clear example of how climate change affects those already vulnerable.

Research also shows a connection between sustainability and well-being. Wilson (2013) found that people with less eco-friendly activity patterns rated themselves as less happy and less healthy than those in lower-emission households. Another study reported that people living in or with access to more green spaces rated themselves as healthier and happier overall.

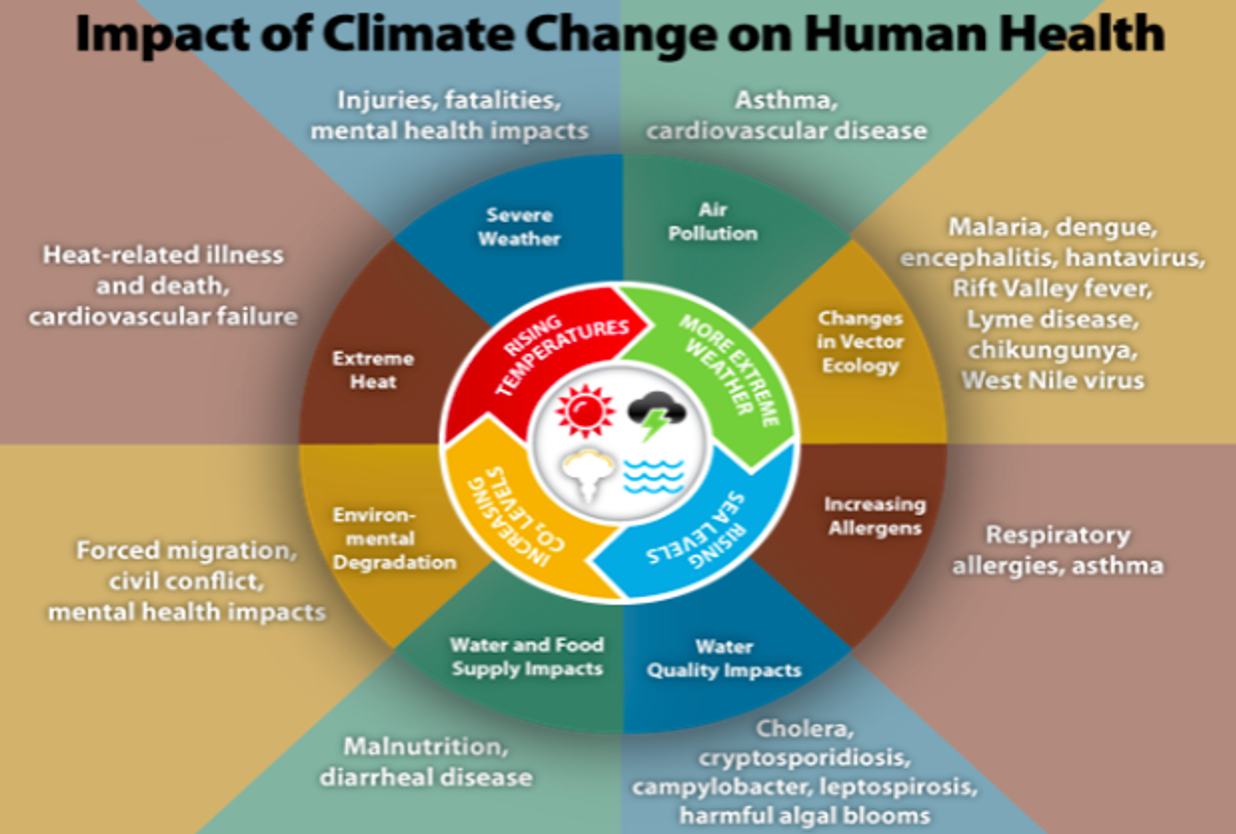

I included an infographic from the CDC (Figure 4) because it captures the interconnectedness of these issues.

Figure 4. Impact of Climate Change on Human Health. (Click here to enlarge the image.)

It shows how greenhouse gas emissions drive rising temperatures, which lead to extreme weather events, rising sea levels, and countless downstream consequences. It also illustrates how sustainability—meeting our own needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet theirs—isn’t just a concept but something playing out in real time.

This is why it matters. What we’ve done since the Industrial Revolution has affected our grandparents, our parents, and ourselves, and will continue to affect our children and grandchildren. I don’t want to live in a world where the Alabama heat keeps me from engaging in my favorite occupation—playing with my kids—and I don’t want them growing up in a world where devastating wildfires, unsafe water, or food shortages are commonplace.

McKinnon (2022) stated that climate change is the leading public health concern of the century. Heat waves alone have significantly reduced opportunities for play and leisure by decreasing safe outdoor time. A 2022 study found that heat-related stress increased by 42% in just a few years, and in 2021, heat exposure caused a loss of 470 billion labor hours, most of them in the agricultural sector. That’s staggering.

The bad news is that human activity has caused much of this. But the good news is that we can change course. Progress is being made, and as occupational therapy practitioners, we can be part of the solution—supporting sustainable occupations, promoting community health, and helping people adapt to and mitigate these challenges.

My Carbon Footprint

A QR code is included in the handout. The quiz is very brief, just four or five questions, and it gives you a general idea of your carbon footprint. It’s an interesting tool to use, especially if you’ve never calculated your carbon footprint before. Later in the presentation, we’ll revisit this and compare what we see in the general population with the impact of engaging in ecopations, so we can understand whether these sustainable occupations truly make a difference.

I also want to share a quote from a member of the World Federation of Occupational Therapists (WFOT) that resonated with me.

“Take a weekend camping trip, and you will notice that nature has a way of taking care of itself. Plants, trees, and animals use the natural resources of their surroundings to meet their needs, yet never take more than what is required for their survival. You will also notice that wastes, such as fallen leaves, decaying plants, and even animal droppings, are all recycled back into the environment to enhance and perpetuate future life. Nature does pretty well when it's left alone. Unfortunately, we see that humans have a way of meddling in the affairs of the natural environment.”

- Rebecca Gillaspy (WFOT, 2018, p. 2)

It captures the essence of sustainability and ecopations in a practical and profound way. My family and I love to camp, and we always try to follow the “leave no trace” principle—pack it in, pack it out. To me, that is one of the simplest ways to describe sustainability. That’s what ecopations are about: never taking more than what’s needed for survival and avoiding unnecessary disruption to the natural environment.

Sustainable v. Unsustainable Occupations

So, do sustainable occupations matter? Do they make a difference? Absolutely—and they can be surprisingly simple to integrate into daily life. I want to share some examples of sustainable occupations that I engage in through a sustainability lens.

| Sustainable | Unsustainable |

| Toilet hippo + bidet, shower, water off when not using, pre-soak dirty dishes | Bathe |

| Walk to school, 1 flight/year, keep up car maintenance | Drive (hybrid) |

| Recycle, Compost, waste free lunch, organic local food (less meat), garden, buy second hand, resale/repurpose or donate, e-bills and e-vites, reusable menstrual products | Single use plastic, purchase dog + cat food, occasional purchase from store/Amazon |

| Programmable thermostat, lights & electronics off when not using, line dry clothes, energy star appliances, low energy light bulbs/natural light | Electric & gas utilities, cable & internet |

These examples might also give you ideas for ways you could incorporate similar practices into your own routines, both professionally and personally. Take a moment to think about which of these you may already be doing without realizing it, and which ones could be easy to add.

For instance, one simple switch is using reusable water bottles or glass containers instead of plastic bottles or disposable Tupperware. I also keep a set of reusable silverware in my car so that when I grab takeout or pick up a salad from a grocery store, I don’t have to use the single-use plastic utensils they provide. Straws are another area where small changes add up. In Italy, for example, straws aren’t even sold in many places, which was refreshing to see. Unless they’re biodegradable, straws don’t get recycled and often end up in our oceans, causing harm to marine life.

Recycling and reusing Ziploc bags is another habit that has made a difference for me. I use a variety of reusable storage bags, and I was excited to discover that Ziploc now makes compostable bags that eventually break down in landfills. You can switch from paper towels to cloth napkins or reusable paper towel alternatives at home. A website I love called Zero Waste Store specializes in these kinds of products, from reusable kitchen supplies to lunch-packing essentials.

Laundry is another area where small choices have an impact. Washing clothes in cold water reduces energy use, and line drying eliminates it entirely. Plus, line-dried clothes and sheets smell wonderful and last longer because dryers can degrade fabric over time. Menu planning is another easy way to practice sustainability. By buying only what you need, you reduce food waste and make your grocery shopping more intentional.

Each of these examples represents an opportunity to reframe everyday tasks as ecopations—occupations that sustain both our lives and our environment. When we approach these activities with intention, we not only reduce our impact on the planet but also create healthier, more meaningful routines for ourselves and our communities.

Let's Compare...

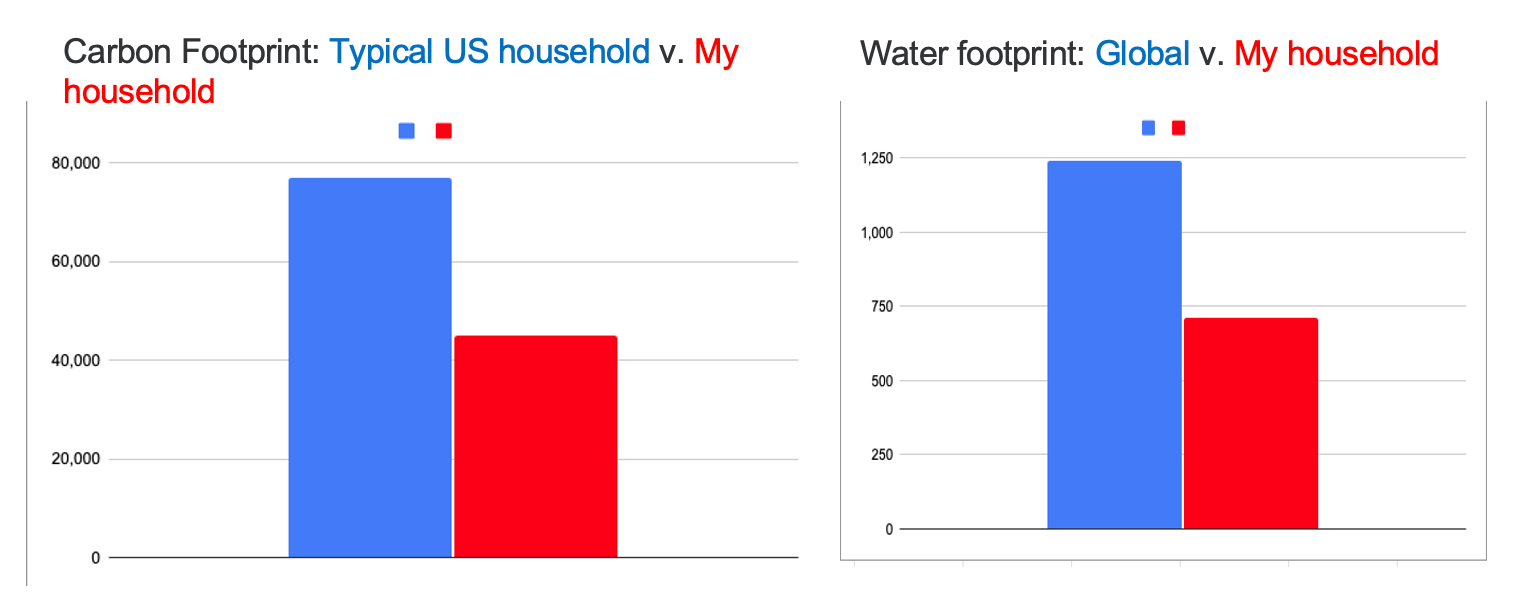

So, let’s compare. Figure 5 shows the difference between my household’s sustainable occupations and those of a typical U.S. household.

Figure 5. Carbon and water footprints. (Click here to enlarge the image.)

I gathered this information from the same carbon footprint quiz I shared earlier, so if you took it, you might notice where your score falls compared to mine. Looking at this data was eye-opening and, honestly, a relief. It showed me that the ecopations I engage in truly make a difference. It was encouraging to see that one person’s actions can significantly reduce their environmental impact, despite the often-heard sentiment that individual efforts don’t matter. And if one household can make this kind of impact, imagine the difference entire communities, neighborhoods, or the populations we serve as OTPs could make if they collectively adopted sustainable occupations.

Here are some numbers to put this into perspective. Recycling at my house reduces our CO2 emissions by about 1,500 pounds yearly. The average U.S. resident produces roughly 77,000 pounds of CO2 annually, while my household produces about 45,000—just under half of that amount. Line drying clothes instead of using a dryer cuts another 523 pounds of CO2 per year, and turning off electronics when not in use reduces emissions by an additional 146 pounds. Using Energy Star-rated appliances contributes to another reduction of 438 pounds annually. The average appliance efficiency rating for U.S. households is about 50 out of 100, while my home’s rating is around 75, which makes a significant difference.

The water footprint analysis was just as fascinating. While the quiz was too detailed to include during the webinar, I encourage you to try one on your own later—it’s very eye-opening. My water footprint is lower than average primarily because I don’t wash my car often, do just two loads of weekly laundry, and eat more vegetables and fruit than meat. That said, my meat consumption was still my largest water consumer. To put this into perspective, according to the Sierra Club, it takes about 700 gallons of water to produce a single cheeseburger: 22 gallons for the bun, 4.5 gallons for the lettuce and tomato, 56 gallons for one slice of cheese, and an astonishing 616 gallons for the meat patty. That was mind-blowing for me.

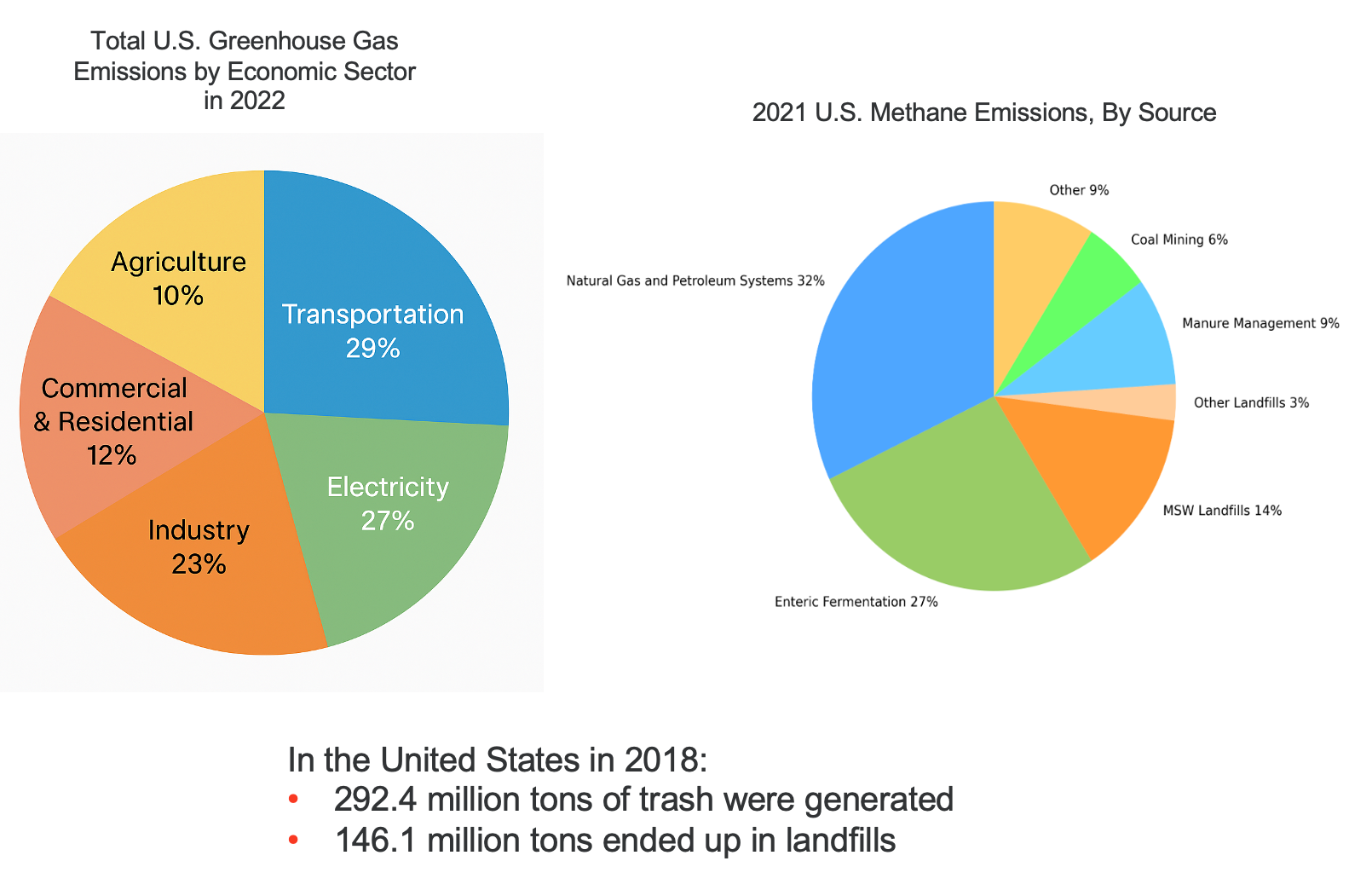

The infographic I included in Figure 6 gives a global perspective on where the U.S. emits most of its greenhouse gases.

Figure 6. Total U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions by Economic Sector in 2022. (Click here to enlarge the image.)

Industries, transportation, and electricity are the most significant contributors. Encouragingly, the agricultural sector has made noticeable strides, with regenerative agriculture and organic farming becoming more mainstream. Forestry efforts by organizations like The Nature Conservancy and the Sierra Club have also pushed for policies to combat deforestation and desertification. This is proof that education and advocacy matter—and in a capitalistic society, how we spend our money is another powerful form of advocacy. When we choose to buy products from regenerative farms, opt for organic or non-GMO options, or purchase fewer single-use plastics, we are signaling our values and influencing market trends.

Plastic consumption in the U.S. is another critical issue. In countries like Italy and Japan, most plastics are recyclable by design. In contrast, here in the U.S., it’s often hit-or-miss whether plastic packaging can be recycled. For example, I’ve noticed that some of my kids’ toys, like Legos, come in recyclable plastic bags, which is excellent, but more than half of the plastic items we purchase are not recyclable and end up as waste. Municipal solid waste is actually the third-highest source of methane emissions in the U.S., largely because of landfills. In 2018 alone, 146 million tons of the 292 million tons of waste generated ended up in landfills. This highlights the consequences of our linear economy model—where items are made, used, and discarded—versus the circular economy model that prioritizes reuse, recycling, and waste reduction.

All of these figures show that sustainable occupations, even on a small scale, do make an impact—and that when scaled to communities or populations, the effect could be transformative.

Circular v. Linear Models

An article in 2020 suggested that the development of capitalism has led to an anthropocentric way of being in relationship to our environment. As the authors wrote, “We urge humans to decrease consumption, stating a circular economy better respects Earth and its resource regeneration.” This idea reframes how we think about production and consumption, shifting us from a mindset of taking endlessly from the planet to one of using resources responsibly and regeneratively.

A circular economy model uses fewer raw materials overall but, more importantly, places value on producing less waste and emitting less methane into the atmosphere. Figure 7 shows what the European Parliament offers as a strong definition, describing a circular economy as “a model of production and consumption which involves sharing, leasing, reusing, repairing, refurbishing, and recycling existing materials and products for as long as possible,” with the goal of extending a product’s life cycle.

Figure 7. The Circular Economy Model.

This contrasts with the linear economy model, which the European Investment Bank defines as a system where people buy products, use them, and then discard them—a straight progression with little thought given to recycling or reusing.

The circular economy approach is not only environmentally beneficial but also a mindset that can be incredibly useful in educating ourselves and our communities about sustainable approaches to occupation. I integrate this concept into my nature-based camps, where we focus on reusing items that might otherwise be considered waste and finding creative ways to make the most of what we already have. Often, we discover that we have more than we truly need, eliminating the pressure to constantly buy something new.

This mindset carries over into my personal life as well. For example, when my kids have birthdays, I work with close friends to do toy swaps or book exchanges rather than buying new items. When we purchase gifts, I often look to consignment stores where toys are still in excellent condition but no longer wanted by their previous owners. This practice not only reduces waste but also helps extend the lifecycle of products, perfectly embodying the principles of a circular economy.

Interventions

Next, we’ll turn our attention to specific interventions, looking at how they can be implemented on multiple levels. We’ll explore global initiatives that address climate change and sustainability, examine local efforts that impact our neighborhoods and communities, and consider interventions that can be applied within groups and organizations. Finally, we’ll bring it down to the individual level, discussing personal and professional actions that each of us can take to promote sustainability in our daily lives and in our occupational therapy practice. This multi-layered approach will help us see how change is possible at every level of influence—from the broadest systems to our own day-to-day choices.

Macro-environment Interventions: Industry & Government

The image in Figure 8 shows an example of biophilic design in urban planning, specifically at the Shanghai airport.

Figure 8. Biophilic design at the Shanghai airport.

This airport integrates various gardens throughout multiple terminals, creating a space that feels alive and restorative. I’ve never been to Shanghai myself, but just looking at this picture makes me want to visit the airport, and I can only imagine how incredible it would be if airports in Birmingham or Atlanta incorporated similar designs.

Biophilic design is rooted in the biophilia hypothesis, a concept introduced by Edward Wilson in 1984. This hypothesis suggests that humans have an innate predisposition toward nature—we are naturally drawn to it and experience a sense of calm when surrounded by natural elements. This principle is something I integrate into my work and share frequently on my social media through my business, Integrative OT. There are countless benefits to incorporating nature into our environments, even in simple ways.

For instance, if you can’t get outdoors, something as small as keeping a plant on your desk or displaying pictures of natural scenes can be profoundly calming. And if you have the opportunity to be in nature, the benefits increase significantly—exposure to natural environments has been shown to boost immune function, and even getting your hands in the dirt can introduce microorganisms that positively impact your immune system. These connections between humans and the natural world are powerful, and biophilic design leverages them to create healthier, more supportive spaces.

I’ve included a YouTube video link about industry and business solutions related to sustainability. We don’t have time to watch it together during this webinar, but I encourage you to take a look when you can—it’s a fascinating exploration of how large-scale systems can integrate sustainable practices.

The EU Emissions Trading System Explained

In Europe, many countries have implemented a system that incentivizes sustainable practices by offering financial rewards—almost like a bonus—for meeting sustainability goals. If a company uses all of its allocated credits, it can even borrow from other companies, creating a collaborative framework for reducing environmental impact. This type of program provides a strong incentive for corporations to prioritize sustainability in their operations.

Closer to home, I’ve seen some impressive examples of industry and business interventions. A friend of mine has worked as a sustainability manager for companies like Nike and Mohawk Flooring. She shared that Nike aligns its greenhouse gas reduction targets with the Paris Climate Accord and places a heavy emphasis on using sustainable materials, such as recycled polyester. Mohawk Flooring is also setting new sustainability targets, working to reduce electrical energy consumption by shifting from gas to electricity and investing in more efficient equipment.

My husband, an engineer at Honda, has shared some of their exciting initiatives. Honda targets zero carbon emissions by 2050, focusing on innovations like fuel cell and battery electric vehicles. They’ve also developed processes for recycling both cars and batteries—an emerging and critical practice. One project I find particularly fascinating is their Dreamo initiative, which explores carbon sequestration through algae panels in the ocean. They also plant trees near their U.S. manufacturing plants to offset emissions, integrating sustainability into their operations in multiple ways.

For most of us, our role in these large-scale industry efforts may not be direct, but we have power as consumers and advocates. “Voting with our dollars” by supporting companies committed to sustainable practices makes a tangible difference. We can also advocate by joining professional groups like the Occupational Therapists for Environmental Action and supporting leadership within organizations like AOTA and the World Federation of Occupational Therapists (WFOT), which prioritize sustainability.

The data on consumption habits underscores the urgency of these efforts. In 2019, the Green Alliance reported that up to 80% of Black Friday purchases are thrown away after zero to one use—a staggering figure, though not surprising, given how quickly many products, especially children’s toys, are discarded. Choosing to reduce our consumption, reuse what we have, and participate in clothing and toy swaps are simple yet powerful ways to break that cycle.

On a professional level, WFOT has been a leader in this space. In 2018, they developed guiding principles for sustainability in practice, scholarship, and education, including ethics and standards. Several countries—including the UK, Canada, and Sweden—have incorporated sustainability into their professional standards for occupational therapy. Here in the U.S., AOTA’s policy E16 is a positive step forward, but it has not yet been integrated into ACOTE’s educational standards. Moving in that direction would help ensure that sustainability is woven into OT education nationwide.

There are also inspiring international examples of collaboration. The Philippine Occupational Therapy Association partnered with the government to create disaster preparedness and response programs, as reported in a 2013 article. In Spain, OTs are working with the European Union on Project Recover, which develops gardening and landscaping jobs for individuals with mental health challenges or those living in poverty. This project, led by a university in Catalonia, has expanded to include Ireland, turning it into an international initiative.

In the U.S., the Medical Society Consortium on Climate and Health—comprised of 47 medical societies and other health professionals—advocates for climate solutions that protect public health. While OTs are not yet represented in this consortium, I am working to change that, and I encourage any of you interested in joining this effort to reach out to me.

Finally, it’s worth revisiting the World Federation of OT’s 2018 guidelines, which laid out five core principles for sustainability. The first principle is understanding sustainability, something central to my doctoral project and the purpose of this webinar. It also points to the need for embedding sustainability in OT education, perhaps through new coursework on nature-based practice and integrating sustainability into our professional standards.

Meso-environment Interventions: Group & Communities

Principle two of the World Federation of Occupational Therapists’ sustainability guidelines focuses on the role of occupational therapy in contributing to the mitigation of environmental damage caused by unsustainable lifestyles. I have aligned with this principle by collaborating with a local elementary school in my city to create a walkway that allows families to walk to school instead of driving. I am also working on implementing recycling programs in public spaces such as parks, schools, splash pads, and playgrounds, as these programs currently do not exist in my area of Alabama. Additionally, my alma mater, the University of St. Augustine, promotes a commuter program for students to help decrease transportation-related emissions, and I was encouraged to see this highlighted on their homepage. The information on the right side of the slide represents a school-based intervention I am hoping to receive approval for this upcoming year. The idea is to host a waste-free lunch day, turning it into a game where students weigh their waste and compete for a prize, which would come from Integrative OT. This initiative is based on resources from the EPA, whose URL is provided for further exploration.

Principle three focuses on helping occupational therapy service users adapt to the consequences of environmental damage caused by unsustainable practices. This is where occupational therapy practitioners can make a significant impact because environmental justice is occupational justice. Those most affected by climate change are often those who contribute the least to it. I align with this principle by providing nature-based occupational therapy for neurodivergent children and children with a history of trauma. The benefits of nature-based OT camps are remarkable, and I highly recommend incorporating them if you are in a position to do so.

Principle four addresses community sustainability in the face of environmental catastrophes. AOTA has an entire task force dedicated to supporting people who have experienced natural disasters, helping them adapt to new lives shaped by climate-induced crises. While this is a broad and complex topic beyond the scope of this webinar, AOTA provides a wealth of resources for those interested in exploring it further. The Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists has also done outstanding work in this area, particularly with First Nations communities following the devastating wildfires in British Columbia.

Principle five emphasizes developing professional competence for administering occupation-based interventions to address sustainability issues. A compelling article from the UK discussed how occupational therapy practitioners there have incorporated a sustainability lens into their activity analyses. This is an easy but powerful shift we can all make since activity analysis is a core part of our work. By simply adding a sustainability perspective, we make our practice more climate-conscious. Thrive, a group of occupational therapy practitioners in the UK, has taken this principle to heart by creating community gardening projects for their clients, integrating occupational engagement and sustainability.

Micro-environment Interventions: Individuals

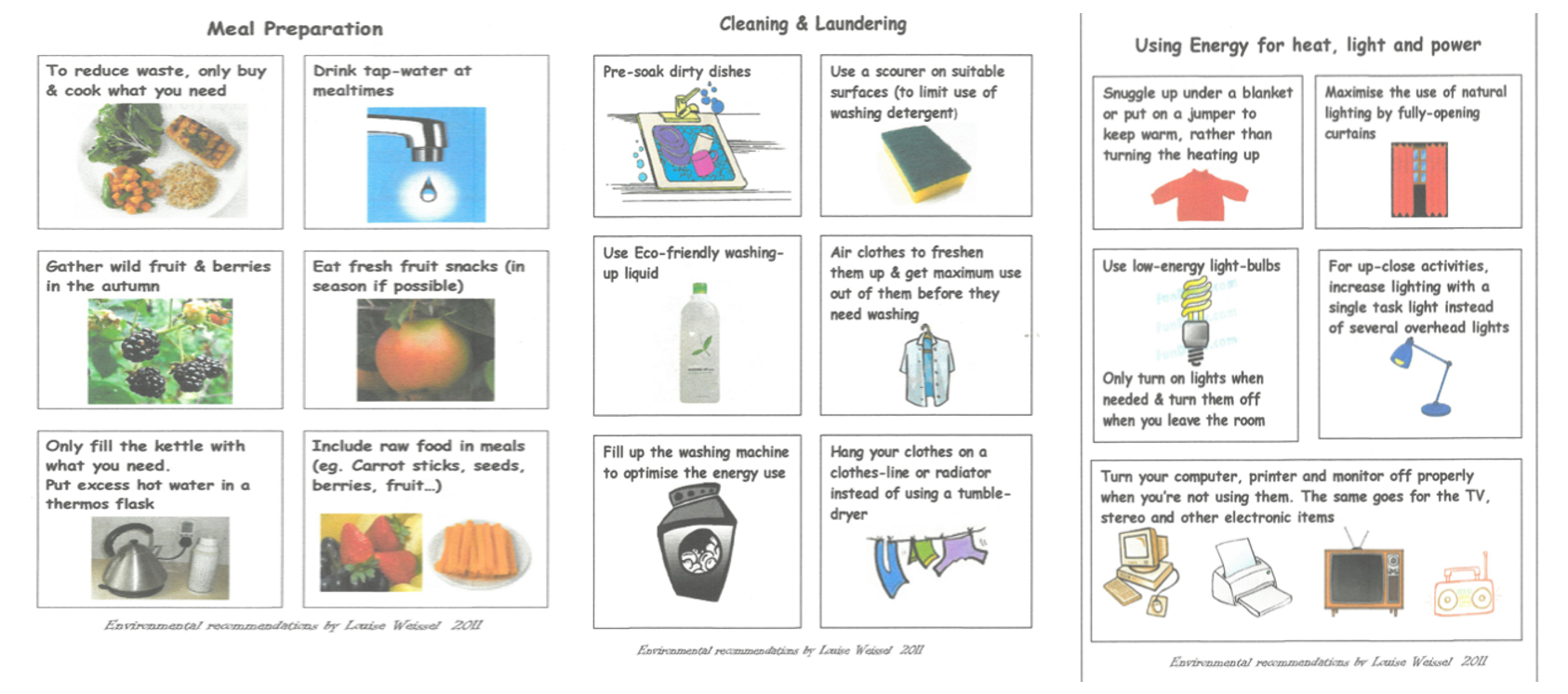

Both personal and professional actions can make a meaningful impact in our interventions for individuals. Louise Wasel Vessel has done incredible work in this area. I first came across her years ago when I found a PDF she created, and I was thrilled to meet her virtually last year when she spoke at the OTEA group. She developed an ADL guidebook with excellent examples of incorporating sustainable occupations into daily life. Here are some examples in Figure 9.

Figure 9. Examples from an ADL guidebook. (Click here to enlarge the image.)

I have the full PDF and am happy to share it if anyone is interested. Many of the examples she provides echo the ecopations I shared at the start of this webinar, and they underscore how small, micro-level changes can make a real difference.

These individual choices ripple outward into our professional roles. We can add a sustainability lens to our evaluations and assessments, repurpose and reuse materials like splinting scraps, and donate or re-gift durable medical equipment to clients in need once other patients use it. Educating our clients about sustainable occupations helps them understand how these practices benefit their health and the environment. For educators, the opportunity is even greater—integrating this knowledge into the curriculum prepares future clinicians to bring these ideas to their clients, who then carry them into their own homes and communities.

Practical changes in our workplaces also contribute. Reducing paper use is an easy first step; during my master’s program, paper waste was significant because recycling wasn’t available, but simply reducing printing made a difference. We can also model sustainability in our everyday actions, such as using reusable bags and containers, choosing meals with more vegetables and less meat, and carrying reusable water bottles. These choices create opportunities for meaningful conversations with colleagues and clients about why they matter.

When discussing ADLs with clients, we can integrate sustainability into those conversations. For example, I worked with a client recovering from a stroke who had poor time management and spent excessive time in the shower, wasting water. We addressed his time management goals by introducing a timer while framing the change as a step toward environmental sustainability. Similarly, we can encourage clients to turn off water when not in use, switch off lights in unoccupied rooms, and unplug devices like hot packs or paraffin units when they’re not needed. Upgrading to energy-efficient appliances and light bulbs in clinics and workplaces is another impactful yet straightforward adjustment.

Transportation is a major environmental factor, and air travel has a significant impact. When possible, we can advocate for driving instead of flying for work-related trips or encourage the use of virtual meetings to reduce travel altogether. Finally, improving access to green spaces can benefit the environment and individual health. A 2023 study in the UK found that acute care occupational therapy practitioners who took clients with renal failure outside observed improved mood, better communication, and reduced aggressive behaviors. Access to nature isn’t just a luxury—it’s essential to overall wellness.

Summary

Once enough people know about and care to change even the smallest things, we can begin to transform our communities, and that ripple effect can ultimately impact our world.

I want to revisit our learning objectives as we wrap up this webinar. My hope is that by analyzing current occupations and evaluating whether they are sustainable or unsustainable, you now have a clearer understanding of how these practices affect our health, our environment, and our future. We looked at real-time comparisons to see how individual actions can make a measurable difference. We explored the various spheres of influence we hold, both professionally and personally, for promoting wellness.

I hope you leave feeling empowered to combine this understanding and evaluation to educate your clients—and even those around you—on how to engage in meaningful, enjoyable, and sustainable occupations.

Here are the QR codes for my references if you’d like to review them. They should also be included in your handout for easy access.

Questions and Answers

Has anyone read Ezra Klein's book “Abundance”? Is it worth checking out?

Samantha recommended Ezra Klein's book Abundance as a great read. I hadn’t heard of it before, but I’ve made a note to check it out because I love reading books like that.

If a client hasn’t expressed interest in learning about sustainability, isn’t it pushing an agenda to educate them about it?

That’s a great question. I don’t view it as pushing an agenda. As occupational therapy practitioners (OTPs), our role is to help clients on their wellness and health journey and to increase their occupational participation. Looking at ways to do this often involves considering the environment that supports them. For example, the impact of climate issues—like the 470 million hours lost in the agricultural sector or the decrease in leisure engagement due to heat domes—shows how environment and participation are connected. It’s also part of our duty as members of the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA), which has sustainability as part of its policy.

How does sustainability come into play in hospital settings, especially with the use of single-use items (e.g., laundry, incontinence products)?

Hospitals are a big part of this discussion. I recommend looking into the Medical Consortium on Climate and Health as well as the Sustainability Network. They provide excellent resources for hospital-based sustainability efforts. The Medical Consortium, in particular, offers free virtual webinars—usually once or twice a year—focusing on climate, health, and sustainability in hospital settings.

Have you served on any sustainability committees in your practice settings?

A: I haven’t served on formal committees, but I do a lot of education work, especially as contributing faculty with the University of St. Augustine. I present webinars for faculty and am working to integrate nature-based occupational therapy into pediatric courses. In my private practice, Integrative OT, I also focus on community-based education and interventions. Additionally, I’ve collaborated with a hippotherapy center to develop nature-based OT camps for children with trauma histories or those in foster care, which has been a great way to incorporate sustainability and nature into therapeutic interventions.

References

See additional handout.

Citation

Gramling, M. (2025). Occupational therapy's role in sustainability. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5825. Retrieved from https://OccupationalTherapy.com