Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, A Comprehensive Approach to Stress Management and Enhancing Well-being, presented by Robin Arthur, PsyD.

*Please also use the handout with this text course to supplement the material.

Learning Outcomes

After the course, participants will be able to:

Explain the physiological stress response and explain its impact on health, behavior, emotions, performance, and patient care, distinguishing between adaptive (short-term) and maladaptive (chronic) stress.

Describe at least three evidence-based stress management strategies, including methods to help patients manage stress to support recovery.

Explain how to use the CONNECT model to improve communication effectiveness in healthcare settings, including practical methods to validate others.

Introduction

In the high-stakes environment of modern healthcare, stress is often viewed as an occupational hazard. However, understanding the biological machinery behind that "fight or flight" feeling is the first step toward transforming it from a liability into a manageable tool. This course is designed to bridge the gap between clinical theory and personal resilience.

American Institute of Stress

As a psychologist speaking to my colleagues in healthcare, we must begin by examining the broader landscape of stress in our lives at this point. In my professional experience, stress has become one of the leading health concerns in modern society, acting as a significant barrier to the functional outcomes we all strive to achieve with our patients. In 2022, the American Institute of Stress released data from the American Psychological Association stating that America is one of the most stressed countries in the world. The findings suggest that people are not merely feeling pressured; they are feeling paralyzed by stress. This paralysis often bleeds into every facet of their daily life and occupational performance. Additionally, sixty-three percent say they consider quitting their job due to stress, and seventy-six percent say workplace stress is detrimental to their interpersonal relationships. While this is just one study, I can tell you that the body of evidence regarding the effects of stress on our lives is decades long and quite compelling.

American Psychological Association

I recently reviewed the most recent data, and in 2023, the American Psychological Association’s Work in America survey revealed that 77% of workers reported experiencing work-related stress in the past month. I want you to really think about that for a moment. That means three-quarters of the workers surveyed experienced work-related stress within the last thirty days. Even more concerning is that 57% of those individuals cited specific negative impacts as a result, such as emotional exhaustion and a lack of motivation to do their best.

In our roles as psychologists, occupational therapy practitioners, physical therapists, social workers, audiologists, and speech-language pathologists, we all contribute to patient care. When we are not motivated to do our best because we are depleted, we aren't the only ones who suffer; our patients suffer right along with us. As clinicians, we must acknowledge the overwhelming body of evidence demonstrating that stress is profoundly detrimental to our ability to work, play, and love.

Benefits of Getting Calm

Basically, why do we want to get calm? Why do we want to control our stress? First of all, by doing so, you are going to enhance your own well-being as healthcare providers. You know how demanding this environment is, as do I. Being a healthcare provider involves an increasing patient load all the time and reduced time with each patient during our workday, all while facing constant pressure to achieve specific outcomes.

If any of you work in a hospital where they measure your outcomes by relative value units (RVUs), you know exactly how stressful it is to constantly ask yourself how many RVUs you have and how many more you need to get. At the same time, you are balancing the fact that you are dealing with real people; your patients are human beings. If we manage that stress, it will enhance your quality of life, allowing you to stay present with yourself, your family, and your patients when you are at work.

Secondly, your clients will benefit from your knowledge and your demeanor. Your patients are also stressed, and many are facing crises, uncertainty, and emotional pain. When you manage your own stress, you model those healthy practices for your patients. You can then talk to them about how you are managing your own stress when you see that they are struggling. We are actually going to go over some specific ways to identify when your patients are stressed later on.

Ultimately, stress reduction in patients is associated with better outcomes, ranging from reduced blood pressure to improved adherence to treatment. If our patients are less stressed, they are much more likely to do the things we are asking them to do to work toward their healing.

Case Story: Caught Between Care and Capacity

To illustrate the daily reality behind these statistics, let's examine a case vignette involving Elena, a physical therapist. In theory, she allows 45 minutes for each patient, but staff shortages often mean she has to take on more work within the same time window. The time pressure starts the moment she arrives; her first patient is late, forcing her to compensate across her entire schedule. By 10:30, she is already feeling tired and notices her documentation is suffering because her time is so truncated.

Then, a colleague calls in sick, and she is required to pick up two additional patients to ensure as many people as possible are seen. She is left wondering how she can attend to her own patients while also absorbing those of others. This scenario is one we see all too often in healthcare settings. By 2:30 in the afternoon, an administrator informs her she has only two days to complete a mandatory training, meaning she will have to spend her personal time at home finishing it. By the end of the shift, Elena is emotionally exhausted and checked out.

We can see the specific stress factors at play throughout Elena’s day. There is the work overload and the shortened sessions caused by time pressure and incomplete notes. She is experiencing significant emotional labor because her patients' expectations weigh heavily on her; like most of us, she is deeply dedicated to those she treats. There is also the administrative overload where mandatory trainings further encroach on her time. Finally, there is physical fatigue. Most of us in healthcare are aware of the physical toll of seeing patients, often with minimal breaks. We are all familiar with the joke that we sometimes don't even get to eat or drink during the workday. With no time for her extra tasks, Elena is the picture of a stressed physical therapist by the end of her day.

Name Your Stressors

Keeping Elena’s experience in mind, please consider the stressors you encounter in your own work. Using the paper I asked you to have available, take a minute to think about the things you worry about the most currently. These do not have to be limited to work; write down the things you worry about most in general. Please take a few seconds to write those down now.

Next to that list, please rate the severity of the stress for each item on a scale of 1 to 10, with 10 being the highest. Take this list and set it aside, as you will refer to it later in the presentation. Please do not put it away; keep it where you can see it so that we can use it again as we move forward.

Now, let's take a closer look to how your everyday stress is affecting your life by conducting a stress self-check inventory. I am going to give you the questions, and your scoring will be as follows: one is never, two is rarely, three is sometimes, four is often, and five is very often. This was adapted from the Work Stress Inventory. Although this particular version has not been validated, it is considered an adaptation of a validated measure and is provided for your reflection only.

- I feel that demands of my day leave me stretched too thin.

- I struggle to maintain balance between my work and my personal life.

- I often feel rushed or under pressure to meet too many deadlines at once.

- I find it difficult to share my concerns or opinions openly with others.

- Stress from my job or personal commitments carries over to my home life.

- I don't feel that I have enough responsibilities or choice in how I carry out my responsibilities.

- My efforts or contributions are not adequately recognized or appreciated.

- I am unable to utilize my strengths, abilities, or creativity in my daily life.

- I notice stress showing up in my body, such as headaches, stomachaches, or muscle tension.

- I find myself feeling anxious, irritable, or emotionally drained because of ongoing pressures.

When you are finished, please add these up, and we will see where you fall on the Stress Self-Check Inventory according to Figure 1.

Figure 1. Overview of the scores of the Stress Self-Check Inventory (Click here to enlarge the image).

As we look at your scores, the categories help us understand the severity of the pressure you are under. If you scored between 1 and 19, you are in the calm and balanced range, indicating that you are managing stress effectively and your coping strategies are working well. I certainly offer my cheers to you for that, and I encourage you to keep those habits up. Those who fall between 20 and 29 are experiencing mild stress. This is what we consider typical daily stress that most people have, and it remains manageable most of the time.

When we reach the 30 to 36 range, we are looking at moderate stress. At this point, stress is building, and recovery strategies are definitely needed. Please pay very close attention to the rest of our discussion today. High stress falls between 37 and 43, where stress noticeably affects your well-being, and coping becomes much harder. Lastly, if you fall within the 44 to 50 category, that is considered critical stress. Here, stress feels overwhelming, and your health and relationships may be at risk.

If you fall within the 30 to 36 range, I want you to use the stress management techniques we are covering very assertively. If you are 37 to 43 or older, you are entering a stage where stress can affect you both physically and emotionally. For those in the 44 to 50-year-old range, I strongly recommend checking in with your primary care doctor or a therapist. You need to manage this stress aggressively because you are at a very high risk of health issues. We will discuss the physiological reasons for this as we move forward, but please do not wait to take action if you fall into one of these top two categories.

I can tell you from my own personal experience that there was a time in my life, even though I have been teaching stress management for most of my adult career, when I was not paying attention to the symptoms. Had I taken this scale then, I likely would have scored in that 44 to 50 range. I stayed there for months without realizing it because I was so busy at work, just plowing through until my body finally got tired and stopped me with a health emergency. Had I stopped earlier in that stress cycle, there is no doubt in my mind that I could have avoided that crisis. I had to take accountability for the fact that I wasn't taking care of myself. This is why teaching stress management became even more vital to me; I personally experienced how high the stakes are. Please do not wait too long if you are in one of these categories, and if you notice your patients are operating at these levels, suggest they also check in with their primary care provider. This information is essential for us and for those we serve.

What is Stress?

But what exactly is stress? We use the word so often when we feel overwhelmed, and while that is true, I believe we almost overuse the term. Fundamentally, stress is biological. It is your body's natural response telling you that something is wrong. When there is an imbalance between the demands placed on us and our ability to cope with them, we become stressed. Historically, stress was that vital fight-or-flight mechanism. Way back when we had to run from saber-toothed tigers or other immediate physical dangers, stress kicked in, we ran, and we "got out of Dodge."

In modern life, our stress presents more as social and mental, rather than physical, and it is increasingly chronic in nature. This has a much more lasting effect on our bodies. In healthcare settings, stress is rarely about running from predators. Instead, it is about that non-stop patient load, charting after hours, and all the pressures we saw Elena dealing with. Even so, your physiology still reacts as if you are in that primal fight-or-flight state.

Take a minute right now to think of a recent stressful day you have had. Did your body respond with racing thoughts, tight shoulders, or shallow breathing? Write down what you noticed happening in your body during that stressful day. Those are the specific signals that stress management techniques will help you address as we move forward.

Before examining how stress affects the body, it is essential to acknowledge that stress is not always negative. A manageable level of stress can sharpen our focus and drive us to action. If you have ever procrastinated on a paper or your chart notes and suddenly realized they must be finished, you felt a manageable amount of stress that pushed you to work quickly and accurately. It drives motivation and pushes us to excel. In athletics, especially, a small amount of stress can lead to greater performance. We call this eustress. We do not want to eliminate every single ounce of stress; that small amount helps us. However, when it tips over into those higher categories we discussed, the third category and above, it must be managed.

Stress Cycle

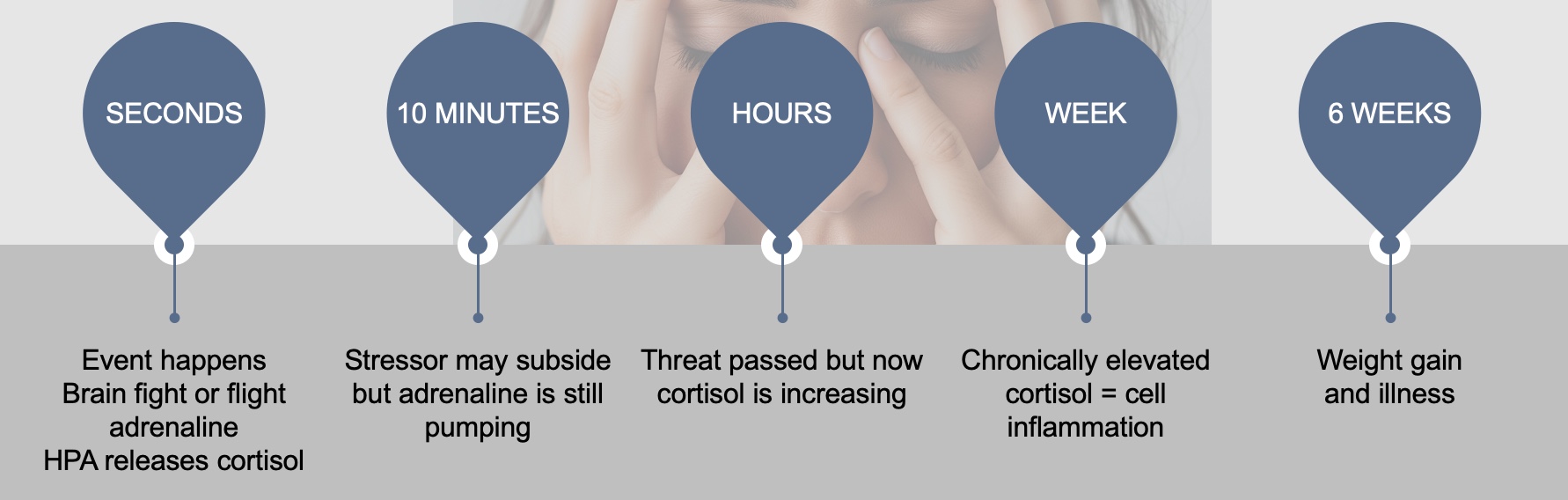

Here's the stress cycle (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Stress cycle (Click here to enlarge the image.)

Something happens, an event occurs, and within seconds, we start pushing adrenaline and then cortisol. Within about 10 minutes, the stressor itself will typically subside. It is gone, but the adrenaline is still pumping through your system. As hours pass, the threat is definitely over, but your cortisol levels are increasing. If you have not dealt with that stress within a week, you have chronically elevated cortisol. This leads to cell inflammation, and as healthcare providers, we know cell inflammation is never a positive thing.

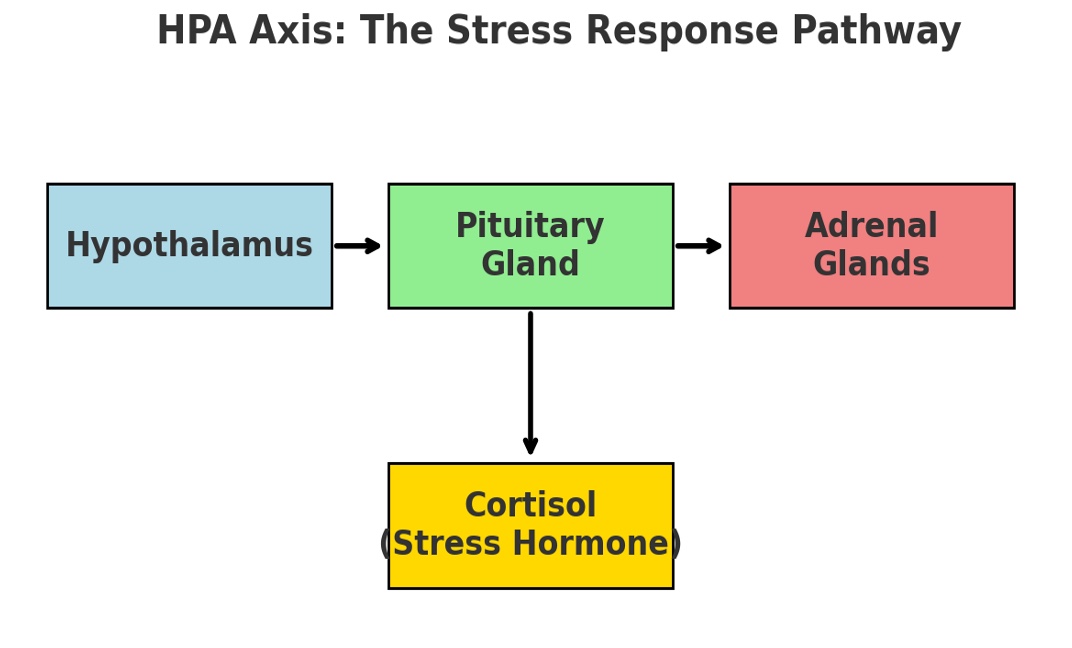

Within about six weeks, you may experience weight gain and illness, as cortisol causes us to gain weight, and cellular inflammation increases our susceptibility to diseases. Another way to examine this is through the physiological lens of the HPA axis, which is the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. I could rehearse that name all day long and still struggle to get it right. When we discuss stress, it is not just a mental phenomenon; it is rooted in our physiology.

The HPA axis, in Figure 3, shows that the hypothalamus detects a threat in those first few seconds and signals your pituitary gland. Your pituitary gland then releases hormones that stimulate your adrenal glands, which in turn release cortisol.

Figure 3. The Stress Response Pathway.

This is the mechanism creating all of that cortisol. Cortisol mobilizes your glucose and fatty acids for energy in short bursts. While this is adaptive in the moment, repeated activation keeps that cortisol elevated and contributes to fatigue, immune dysfunction, and long-term health risks.

When you think of your HPA axis, I want you to remember it is like an engine in your body. If this engine is running smoothly and steadily most of the time and doing what it needs to do, it is going to last longer, and it is not going to break down. However, if your HPA axis is constantly stimulated and running quickly, it is going to suffer damage. If you think of your HPA axis like an engine in a car, an engine running slow and steady does well, but an engine under constant pressure shuts down.

Remember that the engine inside us, the HPA axis, regulates our stress, and it determines whether we move into physical illnesses. This is an essential thing for us to keep in mind for ourselves and for our patients. Let's examine the long-term effects of stress on the body. We know through research and through experience that stress is absolutely, beyond a shadow of a doubt, the precursor to physical and mental health issues. As I mentioned in my introduction, I have worked in vascular surgery, neurology, and pediatrics. One of the things I consistently observed in working across all these fields was that people were already stressed before they developed a disease.

Effects on the Body

Let's look at all the systems that can be affected and why we want to work so hard to manage our stress. First is your musculoskeletal system. It is not the one that first comes to mind when you say, "How does stress affect your body?" However, when the body is stressed, your muscles tense up. It is really your body's way of guarding against pain and injury. Stress equals muscle tension, which is a protective reflex. However, chronic tension in your muscles, especially in your shoulders and neck, can lead to migraines, back pain, and joint pain. This can worsen recovery from a musculoskeletal injury. You want to help your patients understand that stress is going to cause their other injuries to recover more slowly. These headaches and migraines are all associated with chronic muscle tension in the areas of the shoulders, neck, and head.

Musculoskeletal pain in the low and upper extremities has also been linked to stress, especially job stress. Millions of individuals suffer from chronic painful conditions secondary to musculoskeletal disorders. Keep in mind that whenever one of your patients has a musculoskeletal issue, they are very likely to have stress as well. Those are painful injuries, and when patients feel that ongoing pain, they become even more stressed. We can help them by managing that stress directly.

The second system is one where you are probably more likely to understand the connection. We often think of people having stress and then having heart attacks. This is true because your heart rate increases and your blood pressure rises in response to the fight-or-flight experience.

Chronic stress equals risk of hypertension, heart attack, stroke, and even the inflammation of your coronary arteries, which then leads potentially to heart issues. Women are much more likely to have a heart attack in part because postmenopausal women have lost their estrogen, and that puts their hearts at greater risk. If women, especially postmenopausal women, are stressed for an extended period of time, they are more likely to have a heart attack. Chronic stress experienced over a prolonged period can contribute to long-term problems for the heart and blood vessels. We are going to work hard to lower that stress and keep it under control. There is also some evidence that chronic long term stress affects cholesterol levels.

Moving on to our immune system, it regulates our immunity and reduces inflammation. We know inflammation is not suitable for our bodies. As we discussed with the HPA axis, we want to ensure that we are managing our stress effectively, because when we are stressed, our immune system becomes compromised. That system serves as a protective factor against many other illnesses. Stress can also affect depression and autoimmune disorders. Things like multiple sclerosis have a direct link to the patient having stress before the onset of the disease, and the same is true for many other autoimmune conditions.

In the male reproductive system, cortisol disrupts testosterone production. Lower libido, erectile dysfunction, and reduced sperm health are a result of stress. For females, menstruation is more painful, and cycles can become absent under extreme stress. A pregnant woman who is under stress because of the HPA axis being overactivated has a higher risk of complications and also of postpartum depression. Women also experience sexual changes and fertility challenges because of stress. Again, keep in mind your HPA axis is that engine in your body. We want to manage the stress so that it goes slow and steady and does not overwhelm us or break down the engine.

Regarding the respiratory system, respiratory therapists understand that stress is not helpful, particularly if a patient already has a disease such as COPD or asthma.

Because oxygen is transported to your cells through your respiratory system and carbon dioxide waste is removed, the system needs to be efficient. If you are experiencing a stressful event and breathing rapidly, your respiratory system is not functioning effectively. You do not receive the necessary oxygen, and you are unable to eliminate the carbon dioxide waste. Stress and strong emotions can present as shortness of breath or rapid breathing, and the airway between the nose and the lungs can constrict. While this is generally not a big problem for people without respiratory disease, those with pre-existing conditions such as asthma, COPD, emphysema, or bronchitis need to be particularly aware of how stress is affecting their bodies. Acute stress, such as the death of a loved one, can trigger asthma attacks or panic attacks. Working with a psychologist or taking a stress management class can help develop relaxation, breathing, and other cognitive behavioral strategies to keep the respiratory system working properly.

Then there is our nervous system. Our central nervous system contains the autonomic nervous system, which comprises the sympathetic nervous system and the parasympathetic nervous system.

When the body is stressed, the sympathetic nervous system plays a crucial role in to fight-or-flight response. The body shifts its energy resources to fighting off life-threatening things or fleeing from an enemy. But remember, we have said in today's world, we do not need to escape from many enemies. Both the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems have powerful interactions with the immune system. The central nervous system plays a crucial role in triggering the stress response. We want to keep ourselves calm because chronic stress over a prolonged period of time can result in such a drain on the body that your nervous system actually starts to shut down. It is not so much what chronic stress does to the nervous system itself, but what that continuous activation of the nervous system does to every other body system.

Ultimately, the gastrointestinal system is intricately linked to both your brain and your gut. This is one thing people often think of when they are stressed. There are millions of neurons in your gut so that bowel stress can be very painful. It can cause bloating and affect the rate at which food moves through our bodies. It can either slow it down and cause constipation, or speed it up and cause diarrhea.

Furthermore, stress can induce muscle spasms in the bowel. If you have ever had muscle spasms in your bowel, you know how debilitating that can be for people with IBS and Crohn's disease. Stress will especially affect people who already have a bowel disease. If you have irritable bowel syndrome, it may be due to stress affecting the gut nerves, which in turn alters your microbiota and the way everything functions in your gut.

There is another interesting finding that early-life stress, occurring when the central nervous system is developing between birth and five years of age, can affect the gastrointestinal system throughout a person's lifetime. Later gut issues can actually be a result of those first five years of life. Stress does not just affect the mind; it is not just a mental phenomenon. It impacts nearly every system in the body. Short-term stress can protect, but chronic stress can actually harm our bodies. This is very comprehensive, but because we all work in physical therapy, respiratory therapy, and speech therapy, it is essential for us to know these things so we can share information with our patients. We want to help them understand why they really need to work hard on managing their stress.

Behavioral Consequences of Stress

Let's look at the behavioral consequences of stress. These include eating too much or skipping meals, staying awake at night or lying in bed too long, and an increase in drug and alcohol abuse. We also see a loss of sex drive, increased irritability, heightened fatigue, and a loss of motivation. Stress is not just an internal experience; it manifests directly in our behavior and our cognition. For healthcare professionals, these effects can compromise the well-being of both you and your patients.

Cognitively, you may experience memory loss, poor decision-making, and impaired learning. Your social interactions often suffer as you move toward withdrawal and irritability, and your coping behaviors begin to change. You might start practicing avoidance or using substances to manage the pressure. These shifts disrupt all your established routines, and eventually, your mood becomes dysregulated due to this cycle.

Case Study: Losing Her Voice

Let's take a look at Dana, a speech-language pathologist. She works in an acute care hospital with patients recovering from strokes, traumatic brain injuries, and complex swallowing disorders. Dana is passionate about her work, but recently she has had to cover for a colleague on extended leave, managing her own caseload plus a portion of her colleague's. Let's look at how her stress evolves.

In the first one to three weeks, she is managing okay, but she skips her morning routine to make the team huddle and get a head start on paperwork. She starts eating lunch at her desk while finishing documentation. She feels mentally drained but tells herself she must push through. By weeks four to eight, her sessions with patients become mechanical. She has less conversational engagement and feels distant from them. She avoids collaborating with other professionals and begins receiving complaints because she is taking too long to complete tasks. She starts forgetting to follow up with patients and becomes noticeably irritated.

By weeks nine and ten, Dana is at a breaking point. She snaps at a patient's family for interrupting her during a session, something she would never have done in the past. She leaves progress notes incomplete, which leads to confusion regarding the care plan. After a week of this, she calls in sick once or twice, claiming she is burned out or needs a mental health day. While off work, she starts browsing job postings for school-based settings, thinking it will be easier. I have worked in schools and can tell you it is not necessarily less stressful, but she has the fantasy that leaving her current job will solve the problem. Because her patient care has declined and she is withdrawing from collaboration, neither she nor her patients is doing well.

Much of this is not her fault. In healthcare settings, many of these factors are systemic. However, when you think about this, who could have intervened? Who in Dana's environment might have helped her before she reached the point of looking for a new job? This is why us as colleagues need to recognize the symptoms of stress. Supervisors need to recognize these signs. Dana's supervisor could have seen this happening in those early weeks and pulled her aside to discuss stress management skills or workload changes to prevent burnout. We work as a close-knit team in healthcare, and we can help each other if we recognize the signs of burnout.

Think about your own behaviors over the past month. Which of the patterns Dana exhibited have you noticed in yourself, even subtly? Take a minute to think through this. Perhaps you are skipping notes, avoiding collaboration because you are too busy, or feeling upset with family members. Have you found yourself looking through the job ads? Write those things down and set them aside so we can reflect on them as we move along.

Psychological Symptoms

Let's take a look at the psychological symptoms, and then we are going to take a break. Psychological symptoms of stress include forgetfulness, anger, frustration, and anxiety. You may notice increased irritability with family members, a loss of concentration, depression, or a sense of powerlessness. It can also manifest as problems with your schoolwork or your professional performance.

One symptom to pay close attention to is dissociation. We observed this in Dana’s case, where she began to separate from her patients and no longer felt as close to them. While severe dissociation can involve a person literally feeling like they are out of their body, the kind of dissociation we typically see in stressed healthcare providers is more of a mental distance. It is where you get that sense of detachment and irritability. You are essentially dissociating from your everyday life and your usual professional standards.

Case Study: The Weight You Can't See

Let's take a look at Avital. Avital is a respiratory therapist in a busy metropolitan hospital. Her work is high-stakes, especially in the ICU, where she manages ventilators for critically ill patients. Over the past several months, patient volume has been rising. Flu season is likely upon us, and we know how challenging that time of year can be for respiratory therapists. To supplement her income, she has been taking frequent on-call shifts.

During the first one to four weeks of this extra stress, Avital experiences a persistent mental replay of difficult cases. Even when she is at home, she is thinking about her patients. She feels mild anxiety before going into work, wondering how many people will be coming in or what emergencies might occur. She is having difficulty relaxing even when she is officially off work. By weeks five to eight, she becomes hypervigilant. She feels on alert at all times and is even startled by noises in her home or outside of her usual environment. She starts feeling irrational guilt, blaming herself when patients decline, even when it is medically unavoidable. She notices a cognitive fog, where she is not concentrating well, is not charting as thoroughly as she did in the past, and is forgetting conversations. She is emotionally numbing and detaching from her surroundings.

By weeks nine to twelve, the situation worsens. She has significant sleep disturbances, waking through the night with racing thoughts about work. She is becoming increasingly pessimistic, telling herself that her work doesn't matter anyway. She is experiencing what we call anhedonia in the mental health world, which is a loss of interest in things she usually loves to do, such as being with her family or engaging in hobbies. She is ruminating, replaying minor mistakes over and over again in her mind. The results for Avital are angry and depressive tendencies, cognitive strain, maladaptive patterns, and emotion regulation issues. None of these are good for her. Whether she is at work or at home, she is affected in every environment.

Symptoms Versus Illness

What happens is that we develop symptoms. When I mentioned that Avital had tendencies toward anxiety and depression, it is essential to realize that these symptoms are present in most of us at one time or another. Having these symptoms does not necessarily mean you have an anxiety disorder or depressive disorder; it simply means the symptoms are present.

However, the biopsychosocial interactions come into play. All of those experiences at work interact with those symptoms, and chronic stress becomes the precursor to burnout. After these factors occur over time, an illness develops. Illness represents an interference with your ability to work, play, and love. When you can no longer go out and have a good time, perform your job, or maintain healthy relationships because of your state of mind, you have moved into what we call an illness. At that point, you may be facing a full-blown anxiety disorder, depression, or burnout.

The World Health Organization has stated that burnout is not a character flaw. It is not fundamentally wrong with you. Burnout has three specific dimensions. First is emotional exhaustion, which we have seen in these case studies. Second is depersonalization or dissociation, which involves cynicism and detachment. Third is a sense of reduced personal accomplishment. We saw all three of these dimensions in the cases we have reviewed.

Burnout is not a personal failing. It is very common in healthcare and is directly related to persistent work-related stress. Our awareness of this allows us to use stress management to mitigate the consequences. What we aim to do as we move forward is to catch the stress while we are still experiencing only symptoms. By doing this, we can mitigate the biopsychosocial factors that would otherwise make the situation worse and prevent us from becoming ill. We have now examined all the effects of stress on your body, emotions, and behaviors.

The Results

Now, let's discuss our next steps moving forward. We have seen the progression from initial stress to distress and finally to disease. It can feel overwhelming, leading you to wonder how you will deal with this and if you can actually avoid getting sick. I promise you that you can.

Take a minute right now to identify one behavioral, emotional, or cognitive change that you want to track for the next week. Perhaps you want to track your irritability or a specific behavioral habit. Write that down and put it aside with your other notes because, as we move into specific stress management techniques, you will be able to apply them to that goal. You can take charge of this process. When I give talks on this topic, I always remind people that stress will always be a part of our lives, especially in an environment as demanding as healthcare. However, two people can experience the same stressor and react in totally different ways. You are absolutely in charge of how you allow stress to affect your life.

The reality is that until people are motivated to make a change, they do not. You likely see this in your own patient care. In my practice, I have to address this directly. When I have a patient who comes in week after week feeling depressed, yet they are not doing the things I have suggested would be helpful, I have to get underneath that resistance. I have to ask what is preventing them from taking those steps and what needs to happen for them to feel capable of making a change. You must find that same motivation within yourself to break the cycle we have discussed.

You Can Take Charge!

For yourself, I want you to list your three biggest motivators to make a change and deal with stress. It's possible that you want to be happier at home, or perhaps you don't want to dread going to work. Whatever truly motivates you to make the necessary changes to manage stress in your life, write those down now. When you are finished, set those aside so they are accessible if you need them.

Now, I was hoping you could review what you have written and read it out loud. It is essential to say it while you're looking at it so that you are processing the information both visually and verbally. By doing this, your brain creates two distinct pathways for taking in this commitment to yourself.

Repeat This Statement

You can also say this preventively. Even if you fell into those lower categories of stress and do not feel you need extensive management right now, you should say this to protect your future self. I can control stress. I will control stress. And I will take care of myself. Nobody is walking alongside you day by day who will take care of you. Only you can take care of yourself, and I want to emphasize that it is not self-indulgent to do so. Let’s say it one more time together. I can take control of stress; I will manage it, and I will take care of myself. I highly encourage you to display your motivators and this statement in a place where you can see them frequently and repeat them to yourself.

We know that in high-demand settings, eliminating stressors is often unrealistic. We cannot constantly adjust our patient loads, prevent emergencies from occurring, or immediately resolve the staffing issues that arise. Stress management skills act as a protective filter between the stressor and the impact on your physical and mental health. This is why two people in the same job can have vastly different outcomes depending on their coping repertoire. We are about ready to build that repertoire as we move forward.

Early intervention is key. You know this is true for the physical conditions you treat, and I know it is true for any mental health condition. When someone comes to see me, and they only have symptoms of anxiety or depression rather than a full-fledged disorder, I am always relieved. I tell them that early intervention leads to the best outcomes and that I am glad they sought help at this stage. The same principle applies to our stress management. In those first few seconds to the first hour after a stressful event, that is when you want to use your techniques, if not prophylactically, before you even enter the situation. You are going to commit to change. You will find a social support system, engage in more meaningful activities, and develop healthy lifestyle habits. These are the tools you will use to take charge of your stress.

Breathe

Let's start with my favorite because all you need for this are your nose and your lungs, and you take those with you everywhere you go. There is no reason you cannot perform breathing techniques as soon as you start to feel stressed. These techniques will decrease stress and anxiety while strengthening your concentration and your ability to learn. They slow your heart rate and lower your blood pressure, help you manage your emotions, and promote a sense of happiness. Breathing is vital, and I am going to teach you three evidence based breathing techniques specifically for healthcare providers.

The first is diaphragmatic breathing. To do this, put one hand on your heart and the other hand on your stomach. When you breathe in through your nose, you want to ensure your stomach expands rather than your chest.

Go ahead and close your eyes for a minute. As I said, you are going to breathe in through your nose and out through your mouth very slowly. When you inhale, count to four. When you exhale, count to six. You will breathe in through your nose and out through pursed lips. Let's do four rounds of this together. Breathe in, out, in, out, in, out. One more. In, out. Now you can open your eyes. This activates your parasympathetic nervous system. It reduces tension, lowers your heart rate and cortisol levels, and is easy to do during breaks in your day. It calms acute anxiety and is best used before a high-stakes interaction.

The second technique is called box breathing. This one is a little different. You are going to breathe in for a count of four, hold the breath for four, breathe out for four, and then hold for four before you breathe in again.

Let's wait for the count to reset and then begin in for four. Hold and out for four. Hold. Do three more of those on your own. Box breathing, as illustrated in Figure 4, is a powerful technique employed by Navy SEALs to help them remain calm, particularly in high-pressure situations, such as underwater environments.

Figure 4. Box breathing technique.

There is evidence-based research that box breathing definitely calms you down. Again, this can be done quickly in between patients, potentially.

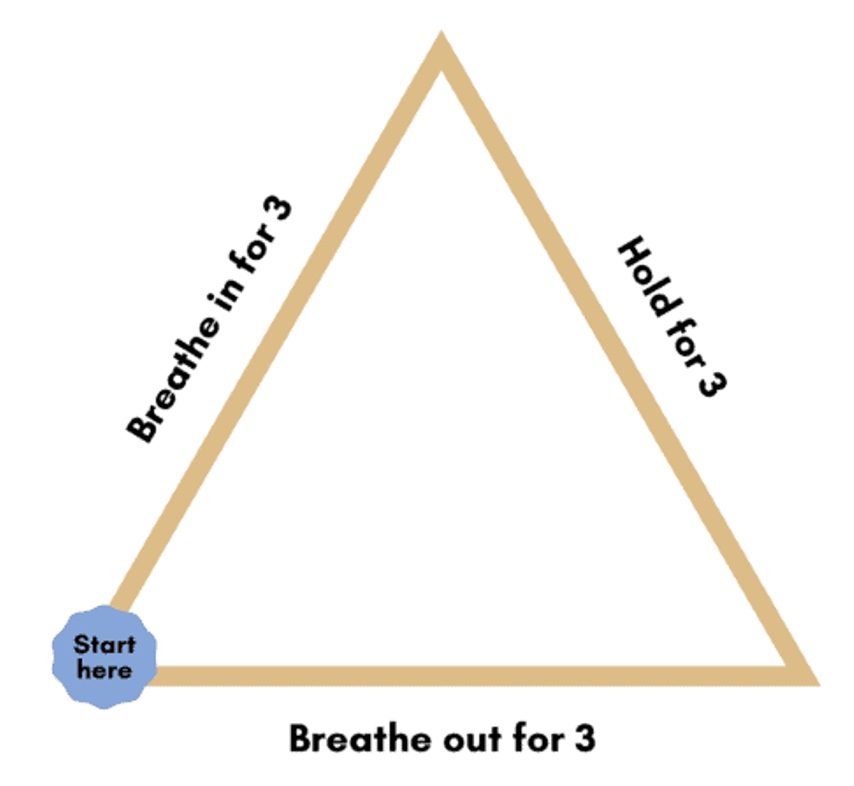

The last one is triangle breathing, as seen in Figure 5. In triangle breathing, you inhale for a count of three, hold for a count of three, and then exhale for a count of three. This creates a simple, steady rhythm that you can visualize as you go. This technique helps you to refocus and regulate your breathing during those busy moments in your day.

Figure 5. Triangle breathing.

Triangle breathing can be used pre-sleep if you have anxiety right before you go to bed. It can also be used at the end of your workday as you transition to go home. Again, you are just going to breathe in for three, hold for three, and out for three. You should repeat this for about four cycles. We are going to go ahead and try that now.

Ready? In for three. Hold. Out. In. Hold. Out. In. Hold. Out. One last one. Good. This is demonstrated to reduce anxiety and improve sleep onset in healthcare providers and the general population. The Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine stated that.

Next is alternate nostril breathing. This is a yoga technique that offers a profoundly impactful way to breathe, balancing both sides of your brain. You can search for a video to see it for yourself if you would like.

Basically, you use your thumb to cover one nostril and breathe in. When you exhale, cover the other nostril. Now breathe in through that same one, switch, and breathe out. Breathe in through the same one, switch, and breathe out. It is very effective. You probably want to do this when you have a little bit more time. If you search for this or look up pranayama breathing, you will find it is a yoga technique that is very effective. It is not something you can do easily throughout your workday, but it is definitely another breathing technique you might want to practice.

Case Story: Pause Between Patients

Let's take a look at Sophia. Sophia is a charge nurse in a bustling emergency department. She just finished a tense interaction with a patient's family,who are upset about the wait time. Her heart is pounding, her shoulders are tight, and she feels a headache coming on. She still has three patients to assess before her shift changes.

The moment Sophia notices her breathing is fast and shallow, it is almost like she is bracing for a sprint. She knows she needs to reset quickly. She steps into an empty medication room and performs box breathing for five cycles. As a result, her heart rate slows down. She feels grounded and clear-headed, and she can now attend to the next patient. She has reset herself by using the box breathing technique.

These are micro breaks. They do not always require leaving the room or the unit for extended periods of time. Sophia just stepped into the medication room really quickly. This reset helps her with emotional regulation, which in turn improves her patient care and the quality of the rest of her day.

Take a moment to consider when you can apply breathing techniques in your work. You can write down several times when you could use this. This is the first building block of the stress management techniques you will take with you. I am going to give you about 30 seconds to write those down for yourself.

Hot Pen Technique

The following technique is the hot pen technique. This is one of my favorites because it is a quick form of expressive writing that helps reduce stress by getting out all the thoughts running through your head that may be making you more upset than you need to be. You write without overthinking or editing. We call it the hot pen because you write continuously and rapidly as if the pen is too hot to stop moving. This bypasses your inner critic, allowing you to write what is truly on your mind.

First, set a timer for a short, focused period of three to 10 minutes at the most. Write nonstop. Do not worry about grammar, and do not lift your pen from the paper. When you are finished, you can destroy it, throw it away, or keep it. Whatever you want to do with it is fine. This technique only requires a pen and paper, although some people use paint instead.

By the time you get to the end, it provides cognitive clarity. You might start with judgmental words and intense thoughts, but your physiology calms as you write. Typically, by the end, you are writing less judgmental things than when you started. The hot pen technique is very effective.

Case Story: Write it Out

Let's take a look at how Ben used this. Ben is a physical therapist who has two patients making very little progress. One patient even screamed at him today before heading home. He takes five minutes to use the hot pen technique and notices he is writing about his exhaustion and his doubt. He feels he is not making progress and is feeling overwhelmed.

By the end of the writing session, his tone naturally shifts toward a more problem-solving and compassionate approach to himself. He then throws the paper away. The result is that he goes home feeling calmer and can be present for his family rather than showing up at his house and complaining about his day.

This is a great technique to use at the end of your day because our work can be very stressful. It allows you to get all of that out and return to your family in a different state of mind.

Healthy Habits

Let's take a look at our healthy habits. We are going to cover sleep, nutrition, exercise, avoiding drugs and alcohol, and spending time in nature. All of these are vitally important for your well-being. We are going to start with sleep because sleep is critical for stress management.

Sleep

I cannot emphasize the importance of sleep for stress management enough. We know that sleep helps our bodies recover, but we do not teach enough about its importance for mental health. When I work with students heading to college, I tell them that keeping a steady, scheduled sleep cycle is the most important thing they can do. Many students get that first taste of freedom and stay out late, which interrupts their cycle. It is no coincidence that we often see the first signs of mental health breaks between the ages of 18 and 22. Whether you are in college or starting a new job, sleep is what keeps you calm and steady, so you do not move from stress to distress and finally to disease.

Sleep is the body's primary mechanism for recovery. When it is disrupted, your ability to handle stress drops significantly. Cortisol regulation during sleep resets your HPA axis, while poor sleep keeps cortisol high and prolongs the fight or flight state in your body. Deep sleep is where you repair tissues, restore energy, and release growth hormones. Chronic stress combined with poor sleep weakens your immune system and makes you more likely to get sick.

We also need to pay attention to the amygdala and memory. REM sleep consolidates our emotional experiences and produces better stress processing. This is why regulating cortisol, promoting immune repair, and managing emotional regulation are so crucial. While these issues are prominent in college-aged people due to significant life changes, psychological problems can occur at any age if sleep is disrupted.

When you go to sleep, aim for seven to nine hours of sleep, following your own circadian rhythm. Some people are early morning risers, like my husband, who always has the coffee ready before I get up. I am not an early riser myself. In healthcare, this knowledge is beneficial because you can often choose shifts that align with your natural rhythm. There is a website called thesleepdoctor.com where you can take a free quiz to determine which animal best represents your circadian rhythm. I am a bear, so my ideal rhythm is sleeping between 11 and 12 and waking between 7 and 8. I now regulate my work to my sleep cycle whenever possible.

To improve your sleep, make your room as dark as possible. Avoid alcohol late at night because it disrupts the sleep cycle. Keep the temperature in your room nice and cool. Finally, set a routine before bed, such as brushing your teeth or reading a book. Definitely avoid screens, as we don't want to be on them right before bed.

Case Story: Running on Empty

Let's talk about Miguel. Miguel is a respiratory therapist in a large urban hospital. He is alternating day and night shifts. Last night, he only got four and a half hours of sleep. He knows from experience that poor sleep will make his day harder, so he plans to use stress management techniques to keep himself grounded during the workday. He does not want to become irritable, foggy, and overwhelmed.

He wakes up feeling groggy, but he takes five minutes to do diaphragmatic breathing before even getting out of bed. Then he drives to work. Instead of playing the news and getting upset or having his HPA axis activated, he listens to a short mindfulness audio and feels mentally centered.

Mid-shift, a patient's oxygen level drops, and his adrenaline spikes, but he consciously slows his breathing. He adjusts the patient's ventilator with steady hands and communicates clearly with the nurse assisting him. After the patient stabilizes, he does box breathing in the supply room to calm himself down. Here, he is breaking that stress cycle by practicing box breathing.

Later in the day, he begins to feel overwhelmed while charting. Instead of pushing through, he breaks his tasks into smaller chunks. Breaking things into smaller chunks will always help your stress management. At the end of the shift, because he had used these stress management tools all day, Miguel leaves the hospital feeling more energized. He feels sharper and less irritable. He goes home, takes a warm shower, and sleeps for a full seven hours. The intentional stress management during the day made a significant difference.

Take a minute now to write down several changes you can make in your sleep preparation. If you sleep with your phone in your bedroom or watch TV before bed and want to discontinue these habits, go ahead and write them down. Whatever you want to change in your sleep preparation, write it on your worksheet.

Nutrition

Alright, let's discuss nutrition. The brain-gut connection is a real phenomenon, as we discussed earlier. Nutrients such as magnesium, vitamin D, and probiotics have a direct impact on our mood, resilience, and stress recovery. What we eat helps us deal with stress.

This is not about dieting; it is about refueling your body and mind with the appropriate things to help you manage stress. Dietary choices significantly impact hormone production, inflammation, neurotransmitter activity, and overall brain function. It is essential to remember that the food we eat affects us throughout the day.

The Mediterranean diet has long been studied as one of the healthiest diets. While it is not the only option, it is very comprehensive. This diet includes:

Vitamin C: Found in fruits, peppers, broccoli, and cabbage to help with inflammation.

Vitamin D: Found in fatty fish, egg yolks, and fortified foods.

Vitamin A: Found in green, red, and orange vegetables.

Probiotics and Prebiotics: Found in yogurt, sauerkraut, fruits, and beans.

Magnesium: Found in leafy greens, nuts, spinach, and legumes.

This way of eating is linked to lower rates of heart disease, which is likely connected to lower stress levels.

I know there are many days in healthcare where the pace and workload prevent you from even taking a break for lunch. However, I want you to take a minute right now to write down several ways you can incorporate better nutrition into your daily work routine. It could be as simple as keeping a bag of carrots or some nuts near your workstation. Write those down on your worksheet now.

Exercise

Exercise regulates your hormones and cortisol levels, leading to a lower baseline cortisol over time, which helps your body recover more quickly from stressors. You don't have to engage in intensive exercise to reap this benefit; moderate exercise is sufficient to activate your parasympathetic nervous system and promote relaxation.

The protective role of exercise on stress acts as a system deregulation, helping with all the physical comorbidities we discussed earlier. It also boosts emotional resilience by increasing the levels of endorphins, serotonin, and dopamine. This reduces anxiety and depression. I tell people all the time when they come in with depression to go out and take a walk every single day. Inevitably, if they do, they start feeling better.

In moderation, exercise enhances your resilience and improves your sleep quality. We know that exercise helps regulate our circadian rhythms and promotes deeper restorative sleep. Better sleep equals improved emotional and cognitive functioning, which is essential in healthcare, where we have to think on our feet.

Exercise also helps build what we call our killer T cells. T cells are a type of white blood cell called lymphocytes that help your immune system fight germs and protect you from diseases. You can think of them like the Green Berets running around your body fighting diseases. When you exercise for 20 minutes or more, your body starts releasing more T cells and lymphocytes, which helps you become healthier and reduces your stress.

Exercise is not just physical; it's one of the most powerful ways we can regulate our hormones, boost our mood, and build resilience against stress. Take a minute and write down how you can incorporate a little more exercise into your day. Go ahead and write those down.

Case Story: Pause Between Patients

Let's take a look at how Tanya did this. She's an occupational therapist in an inpatient rehab unit with a very tight schedule. She was starting to feel stiffness, mental fog, and irritability. Her documentation and team meetings were so tightly packed that she thought she didn't have much time.

This is how Tanya incorporated movement: Before her very first session, she took three minutes in the therapy gym to do dynamic stretches, like arm circles, torso twists, and marching in place. She used the walk from the parking lot as an intentional brisk walk, focusing on her posture and breathing. Halfway through the day, when she had a six-minute gap waiting for a colleague, she did 15 bodyweight squats and walked up and down a flight of stairs. She noticed her energy was better, and she felt sharper for her next patient.

Later, instead of taking the elevator to get supplies, she took the stairs. While reviewing notes, she set a timer for every 45 minutes to stand up, walk for 30 seconds, and stretch her calves. At the end of her shift, she took an extra loop around the hospital to add a thousand steps and mentally decompress. By doing the exercise equivalent of a "hot pen" exercise, she felt less tension in her neck and shoulders and was ready to go home energized and much less irritable.

Now I'm going to move on to yoga. I believe yoga is one of the most beneficial exercises we can practice. I often encounter resistance to yoga; people say they aren't flexible or they dislike it. When I started my career, yoga was less well-known, so the resistance was even higher. Even my own husband used to say he couldn't do it. I told him, "Just try to touch your knees," because he couldn't even do that. Over time, he was able to touch his toes, and now he can practice yoga.

You don't have to start as a yoga guru; you have to start practicing flexibility. As the physical therapists here are aware, being flexible is crucial to our long-term health. Yoga combines physical flexibility with the breathing techniques we've already discussed, making it a double win for stress management.

Yoga

Yoga is a scientifically proven practice for stress management. What I like about yoga is that it is a multimodal approach. It combines physical postures that release muscle tension and eliminate toxins from your muscles with controlled breathing, which regulates your nervous system, and mindfulness practice to help alleviate mental rumination.

Research supports yoga as an effective tool for reducing perceived stress, enhancing emotional regulation, and improving resilience in both healthcare and the general population. It is effective because it addresses both the physical and mental components of the stress response simultaneously. Figure 6 shows the benefits of yoga.

Figure 6. Yoga benefits wheel. (Click here to enlarge the image.)

All of the poses are designed to help you calm; they create a buffer between stress and improve your recovery from stressful events. If you can pick a few yoga poses to do after a stressful event, it will help calm your HPA axis and reduce cortisol production. Yoga lowers your heart rate and breathing, increases flexibility, and improves sleep quality. It is very beneficial for sleep and decreases your anxiety, depression, and emotional regulation issues.

Another fascinating aspect of yoga involves the telomeres at the end of your chromosomes. These are the protective caps at the end of your chromosomes that shorten as we age, especially if you are under chronic stress. Shorter telomeres are associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular disease, depression, and early mortality. Chronic psychological stress accelerates this shortening.

Research has shown that yoga helps maintain the health of these telomeres. The combined effects of yoga reduce stress hormones, lower inflammation, improve antioxidant activity, and enhance emotion regulation, which in turn helps your telomeres. Dean Ornish conducted a five-year study that demonstrated lifestyle interventions, including yoga, meditation, and a healthy diet, resulted to a 10% increase in telomere length. Another researcher found that a 12-week yoga and meditation practice increased telomerase activity, the enzyme responsible for rebuilding telomeres. Additionally, a study on older adults with stress-related cognitive decline showed that yoga improved mental health and increased telomerase activity.

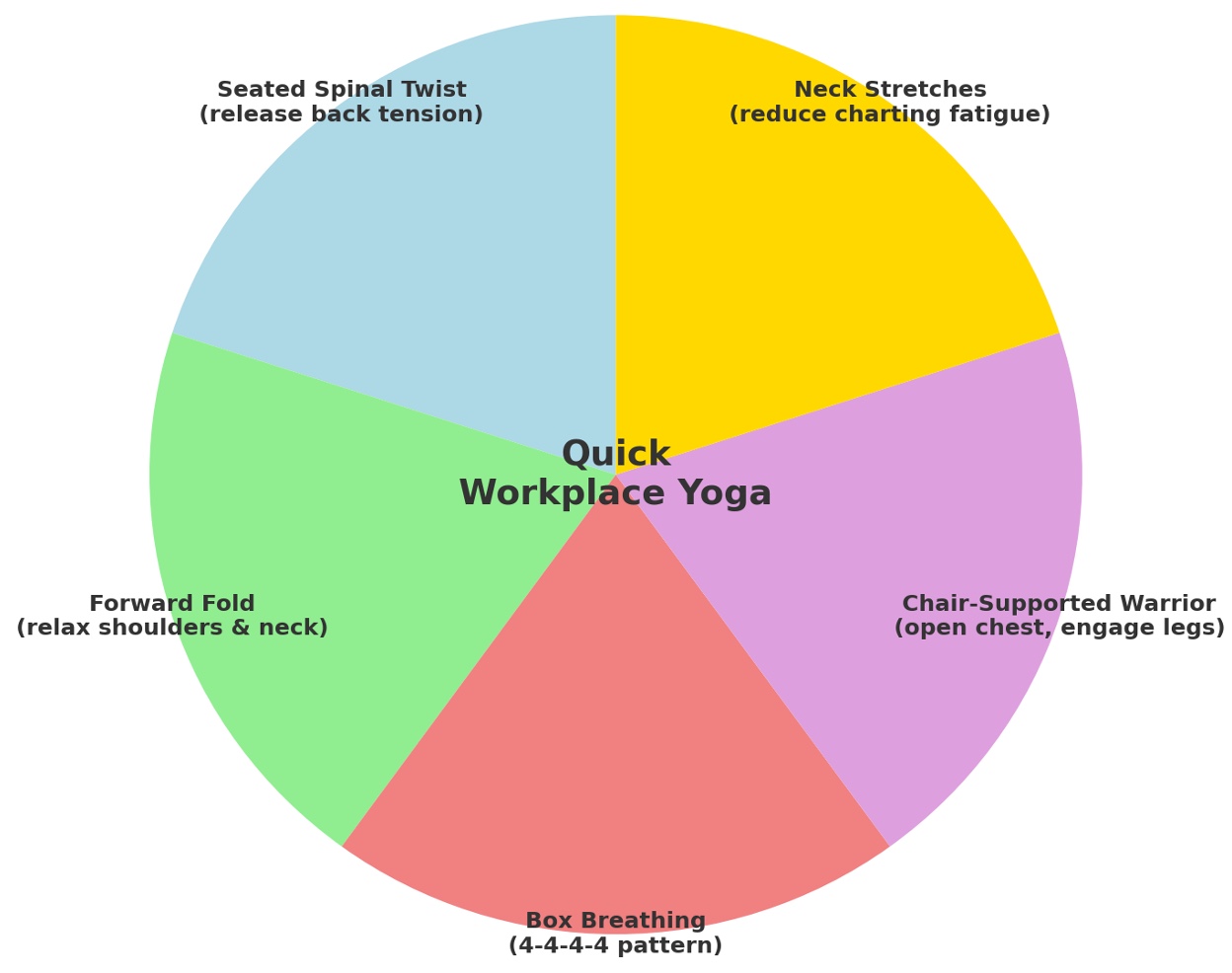

Yoga offers numerous benefits, and civilizations have been practicing it for over 5,000 years. I am pleased that it is gaining popularity in the United States and hope that more people will incorporate it for stress relief and overall well-being. Figure 7 shows some desk-friendly ways to practice yoga.

Figure 7. Desk-friendly stress relief practices. (Click here to enlarge the image.)

The seated spinal twist is a pose that some of you may already practice when you feel stressed at work. You turn to the side and stretch, and it feels terrific. Make sure you balance yourself by doing the other side as well. Your neck stretches involve gently moving your head to one side and then the other, holding each side to stretch your neck. That is desk-friendly yoga.

The forward fold is where you fold forward in your chair, allowing the tension to drain out of your body as you do so. The chair-supported warrior will enable you to open your chest and engage your legs while seated in a chair. You can also find pictures of these online. Box breathing is also considered a yoga technique, and you have already learned that. These are all things you can do right at your desk.

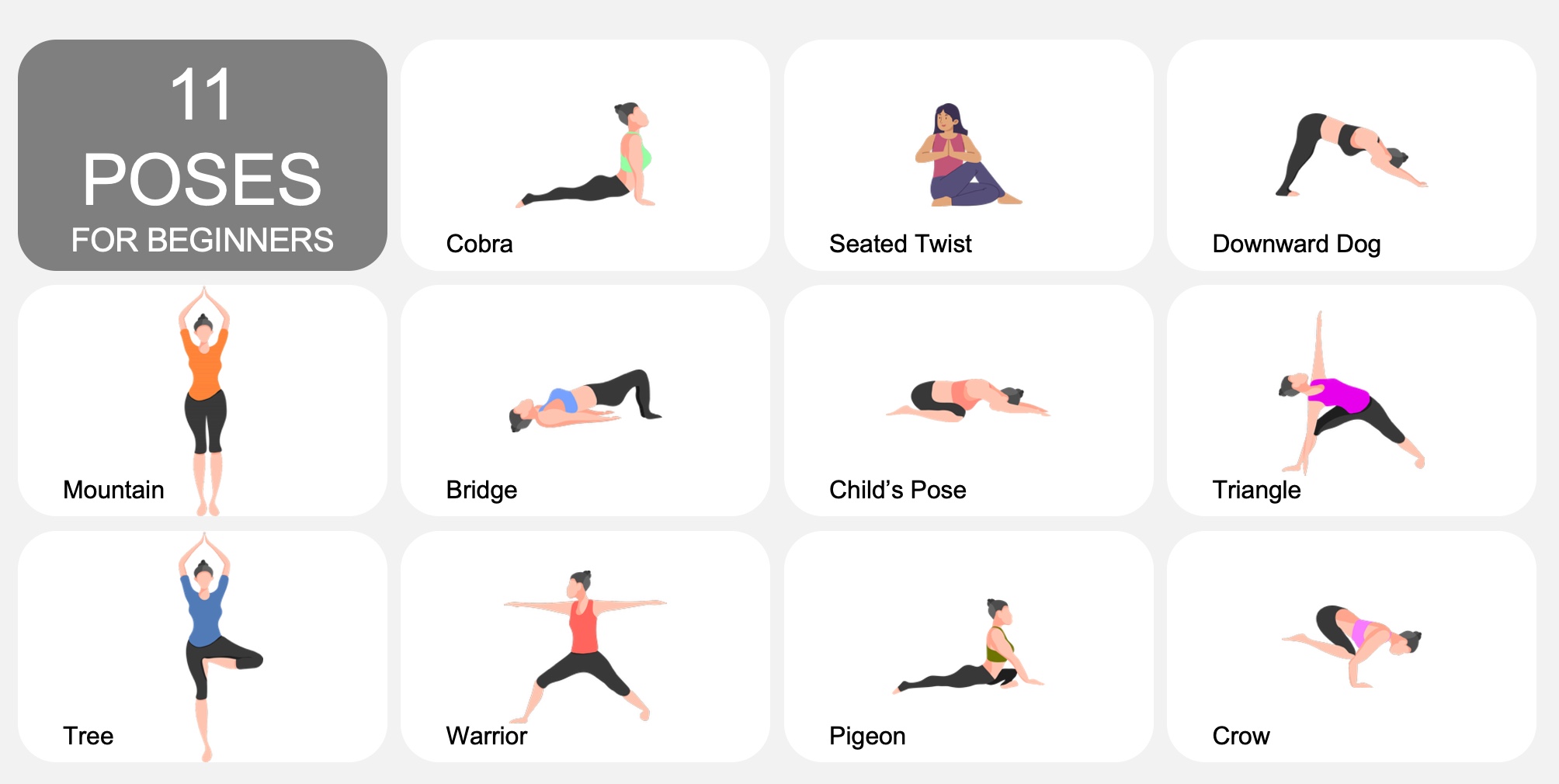

Figure 8 shows yoga poses for beginners. These include simple movements like the mountain pose, cat-cow, and child’s pose, which are excellent for releasing the physical manifestations of stress throughout the body.

Figure 8. Eleven yoga poses for beginners. (Click here to enlarge the image.)

These are 11 poses for beginners in yoga. Never start yoga if you have a back injury or any other condition without consulting your doctor. If you plan to start a yoga practice and have any pre-existing physical conditions, it is best to wait until you have addressed them. Check with your doctor, physical therapist, or healthcare provider to see if yoga is suitable for you.

Sometimes, you can find a yoga expert who understands how to help you if you do have health issues. These are some very easy poses, except for the crow. The crow is not an easy pose, but all the other ones are easy poses that you can do. If you try them just once, I think you will enjoy them enough and see the benefits sufficiently that you will hopefully continue.

Take a minute right now and write down how you might try some yoga or incorporate it into your everyday life. Five minutes of yoga in the morning is very invigorating for the rest of your day. Take a minute to write down how you might use yoga. If you are sitting there saying you'll never use yoga, I want you to think about how you might motivate yourself to try it just once. You can try it at home. You can find yoga on YouTube or other channels where you can try it at home and not have to feel like you are exposed to other people when you are not flexible.

Nature

I cannot stress how important nature is for us. It lowers blood pressure and boosts our immune system. It even spurs natural cancer-fighting cells. One of the journals from an environmental health perspective linked a 12% lower risk of disease to the stimulation of those natural cancer-fighting cells. Nature plays a crucial role to activating the relaxation response. It lowers cortisol levels, improves mood, restores mental energy, and enhances cognitive functioning.

Even for people with ADHD, we always recommend going outside as much as possible. When I write a psychological report for parents of a child with ADHD, one of the recommendations I always make is to get the child out into nature. Interacting with nature provides a better focus and attention span while reducing mental fatigue.

Even fake nature is good. Add a fake nature element to your wall if you don't have a window in your office or home. Fake indoor plants can replicate the same benefits for your well-being.

Take a minute now to write down how you can incorporate nature into your workday and life. Many hospital systems are now creating outdoor nature areas where people can take a break, recognizing the health benefits. Even incorporating nature sounds into your office can be beneficial.

Sunshine

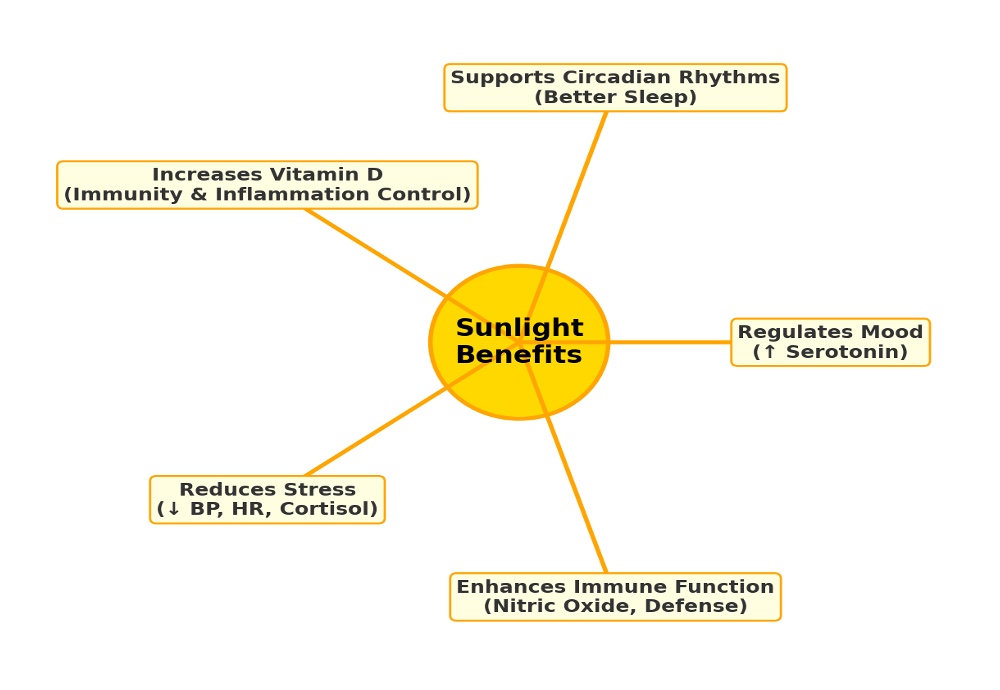

There are some great benefits from the sun (See Figure 9).

Figure 9. Sunlight benefits. (Click here to enlarge the image.)

Sunshine regulates our mood, supports our circadian rhythms, and increases our vitamin D. Especially in places in the north when sunshine decreases in the winter months, you really want to be supplementing with vitamin D. Also, because we use sunscreen, we do not get as much vitamin D. While dermatologists would hate me for saying this, you can go out in the sun for 10 or 15 minutes and get your vitamin D before putting sunscreen on. U have a good friend who is a dermatologist. She says not even one minute in the sun without sunscreen. Sunlight reduces your physiological stress and enhances your immune function.

Sunlight boosts your serotonin levels and improves your sleep quality. Taking an outdoor break in the sun is very important for us. You can hold short meetings outside for some people, or you can promote staff wellness challenges that take place outside. Sunlight is free, a natural stress reliever, and even small doses can improve mood, immunity, and resilience.

Take a minute right now, really fast, to write down how you might incorporate sunlight into your day. They say that getting up in the morning and walking outside into the sunlight, if you happen to be lucky enough to live in a sunny location most of the time, is very beneficial for your mood and health.

Pets

It is really good for healthcare providers. It acts as a buffer against our workplace stressors. Pet owners report less loneliness and greater life satisfaction, and they often say their pet decreases their depression and anxiety. I have many patients and executive coaching clients who utilize pet therapy because animals offer companionship and emotional support, especially for those who live alone.

Dog ownership is linked to a 24% decrease in all-cause mortality and a 31% decrease in cardiovascular death. Dog owners are more likely to meet recommended activity levels because we get up and do things with our dogs, making us less sedentary. There are also social benefits to having a dog. It lowers stress and depression while increasing social interaction. Owning a pet, especially for young kids, helps them develop empathy and emotion regulation.

Definitely consider a pet. I understand that not everyone can have a pet due to allergies or the risk of falls for elderly people, but consider having one for at least part of your life. Dogs in particular trigger the release of oxytocin. Oxytocin is the "happy hormone" that helps you; the dog releases it, and you release it as well when you are petting your dog.

Take a moment to write down if a pet is part of your stress management plan or how you might interact with animals more often.

Mindfulness/Meditation

The next thing we are going to cover is mindfulness and meditation. This is another area, like yoga, that 30 years ago we wouldn't have discussed much. Back then, we didn't have the internet, so people couldn't simply Google these practices to figure out what they were. In today's world, they are becoming increasingly commonplace and are even being taught in schools.

I am pleased about that because the body of evidence supporting meditation and mindfulness as being really important for us has been around for years. Mindfulness involves paying attention intentionally to the present moment. Jon Kabat-Zinn is one of the primary figures who brought the need for more mindfulness and meditation to the forefront. He stated that the benefits to healthcare professionals, in particular, are that we can reduce our perceived stress.

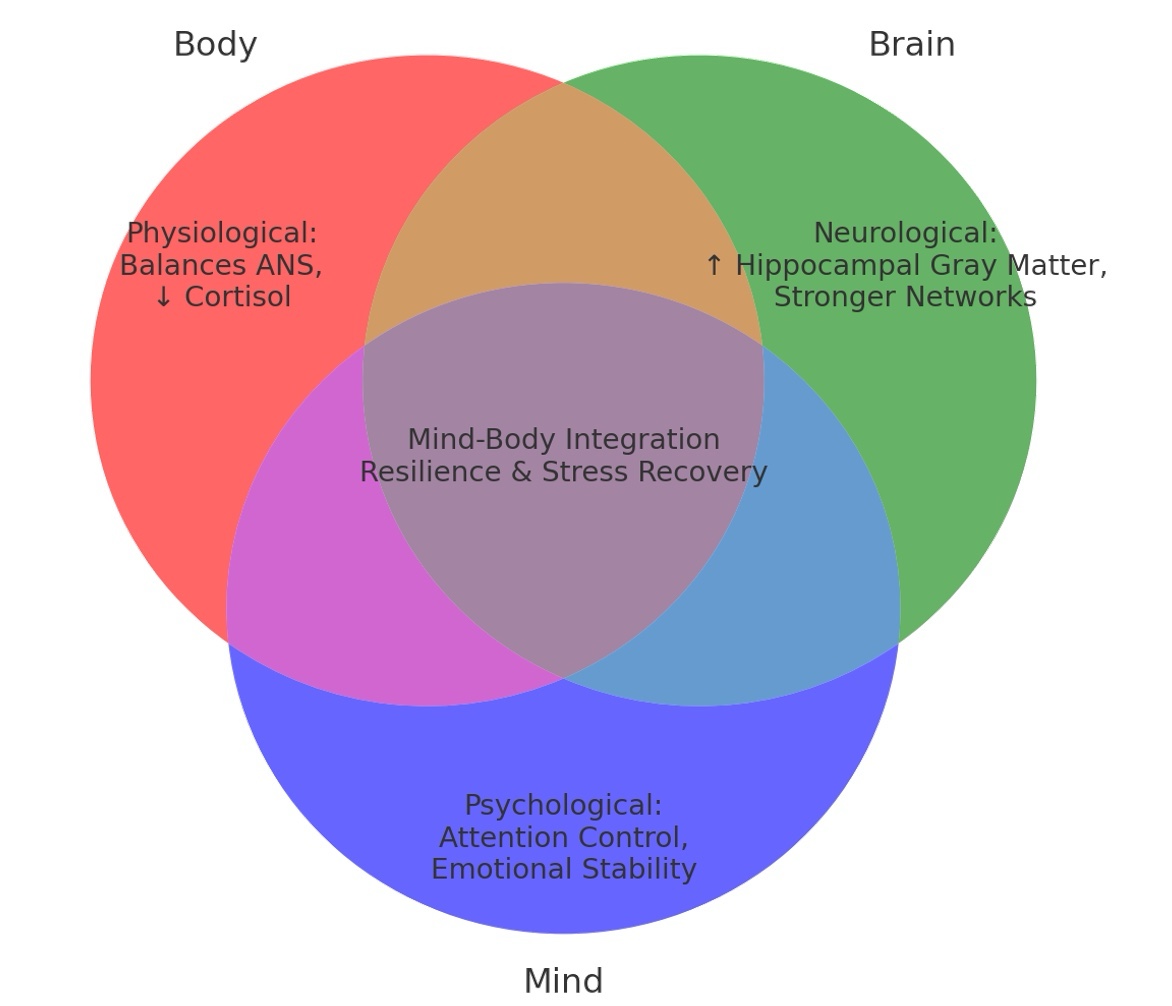

By practicing mindfulness, we can learn to observe our thoughts and feelings without judgment, allowing us to cultivate a deeper understanding of ourselves. This creates a space between a stressor and our reaction, allowing us to respond more effectively rather than simply reacting out of habit or exhaustion. It is a powerful tool for maintaining clarity and composure in high-pressure clinical environments. Figure 10 shows you mind-body integration.

Figure 10. Mindfulness benefits. (Click here to enlarge the image.)

Stress can happen, but we can perceive it more healthily. It will improve our focus and our cognitive flexibility, which we definitely need when working with clients or patients. It also helps with emotion regulation and resilience. When you are being mindful, you can practice your breathing techniques mindfully, or you can sit, lower your gaze, and notice thoughts without judgment.

Mindfulness and meditation are about letting go of judgments so we can cultivate calmness in our minds. We notice our thoughts without judging them. You can try short mindfulness practices at work during a break, whereas meditation is a more in-depth practice. These practices downregulate the stress response, reduce cortisol and inflammation, and help you stay in the present moment. I always tell people you can get through anything if you take it one moment at a time. Staying in the present moment promotes resilience and helps you remain calm and composed.

I started practicing mindfulness when I was 21, but I eventually stopped. When I went to graduate school for my doctorate in psychology, I had four young children and was working part-time. One of my professors told me I would never make it unless I learned to meditate. As a type A personality with a lot to manage, I didn't think I could do it. However, learning to meditate is what allowed me to get through school without shortchanging my family.

When I started again, I had "monkey mind," where the brain jumps all over while you are trying to be still. The person who taught me said to do it for just one minute every day. When one minute feels good, go to two, then five, until it feels comfortable. Because of the health and mental health benefits, I cannot recommend it highly enough. It is absolutely worth trying. I am now going to walk you through two types: a guided meditation and a silent meditation. Apps like Calm and Headspace are also excellent tools for this.

Transcript of the Guided Observation: So the first thing you're going to do is close your eyes. Most people prefer to have their eyes closed. If you don't, you can have a downward gaze. And you're going to do what I call a deep cleansing breath, which means you're going to breathe in through your nose and count to five. You're gonna hold for the count of four, and you're gonna breathe out through your mouth and count to five.

So five in, hold four, five out. Okay, so do two of those. Go ahead. Deep in, hold.

And now I want you to keep your eyes closed and just breathe normally.

And now I want you to imagine that you are sitting on a nice grassy bank.

And below the bank, just a little bit, is a creek. And it's babbling along, making a lovely noise of relaxation.

You notice the sky, the bright blue.

You're sitting below a wonderful tree, and the breeze it creates is calming and relaxing.

And while you're sitting there, you start thinking about some things that worry you.

Perhaps one of the things you wrote down earlier is your worries.

And you start becoming agitated with those worries.

And so what I want you to do is look in the creek and see the leaves that are passing. They're floating down the stream and they're passing you by.

And now take one of those worries and set it on a leaf and watch it as it floats away.

Take another worry and set it on another leaf and watch it as it floats away.

And just keep putting the worries on the leaves and letting them float away.

You should start feeling lighter, calmer, able to enjoy the present moment.

Now you can take another nice, deep, cleansing breath and open your eyes.

I hope you can see how calming it feels to imagine those thoughts being taken out and leaving you; it is a perfect mindfulness exercise.

Now we are going to shift and try a silent meditation. This is often the one people find most difficult because when you are quiet, the thoughts running through your head can feel unbearable.

What you are going to do is pick a mantra—two words that mean something to you. In some traditions, you might use "So Hum" (S-O H-U-M). When you breathe in, you think "So," and when you breathe out, you think "Hum." You can also use "Be Calm" or any two words you like.

To begin, close your eyes and take two deep, cleansing breaths (in for five seconds, hold for four seconds, out for five seconds), then breathe normally. I will keep track of the time. We are going to stay silent for one full minute. Concentrate on your words while you breathe, without forcing your breath.

Take another nice, deep, cleansing breath and open your eyes.

For many, the brain jumps all over during this exercise. That is okay. Staying focused on the mantra helps you return to the center. Eventually, you can reach a state called "the gap," a place of peaceful nothingness. As soon as you think about it, you are out of it, but it feels great while you are there.

I highly encourage you to add meditation to your life. Take a minute to write down when you might try this, even for just one minute. Hardcore meditators often use the "RPM" method: Rise, Pee, Meditate. Since I am not a morning person, I meditate before starting my day with patients or before important meetings. Sometimes I meditate before sleep. Please do not meditate while driving.

Meditation works by connecting your brain neurology with your body physiology. It builds resilience and stress recovery while improving attention control and emotional stability.

Tapping

I am now going to teach you another technique called tapping, also known as the Emotional Freedom Technique (EFT). Developed in 1993 by Gary Craig and based on Roger Callahan’s thought field therapy from the 1980s, it involves a simplified sequence of tapping on meridian endpoints. Similar to acupuncture in Chinese medicine, it focuses on the meridians where energy flows through your body.

Tapping is a self-administered technique designed to relieve stress and anxiety, promote emotional balance, and improve mood. It is a low-cost, non-pharmacological, and safe method that may even help reduce cortisol levels.

It is essential to note the criticisms of this technique. Some argue it lacks a scientific basis for meridians and energy fields, and some studies are considered to have methodological flaws. Critics suggest that the benefits may stem from other psychological factors, such as exposure or the placebo effect.

Despite these weaknesses, I have used it with many patients, and it is frequently taught in healthcare settings. Please try it so you can consider it for yourself or your patients. It is very accessible, as people can easily find EFT tapping videos online to walk them through the process. Tapping involves physically tapping while saying specific phrases to yourself to help "reprogram" your stress response.

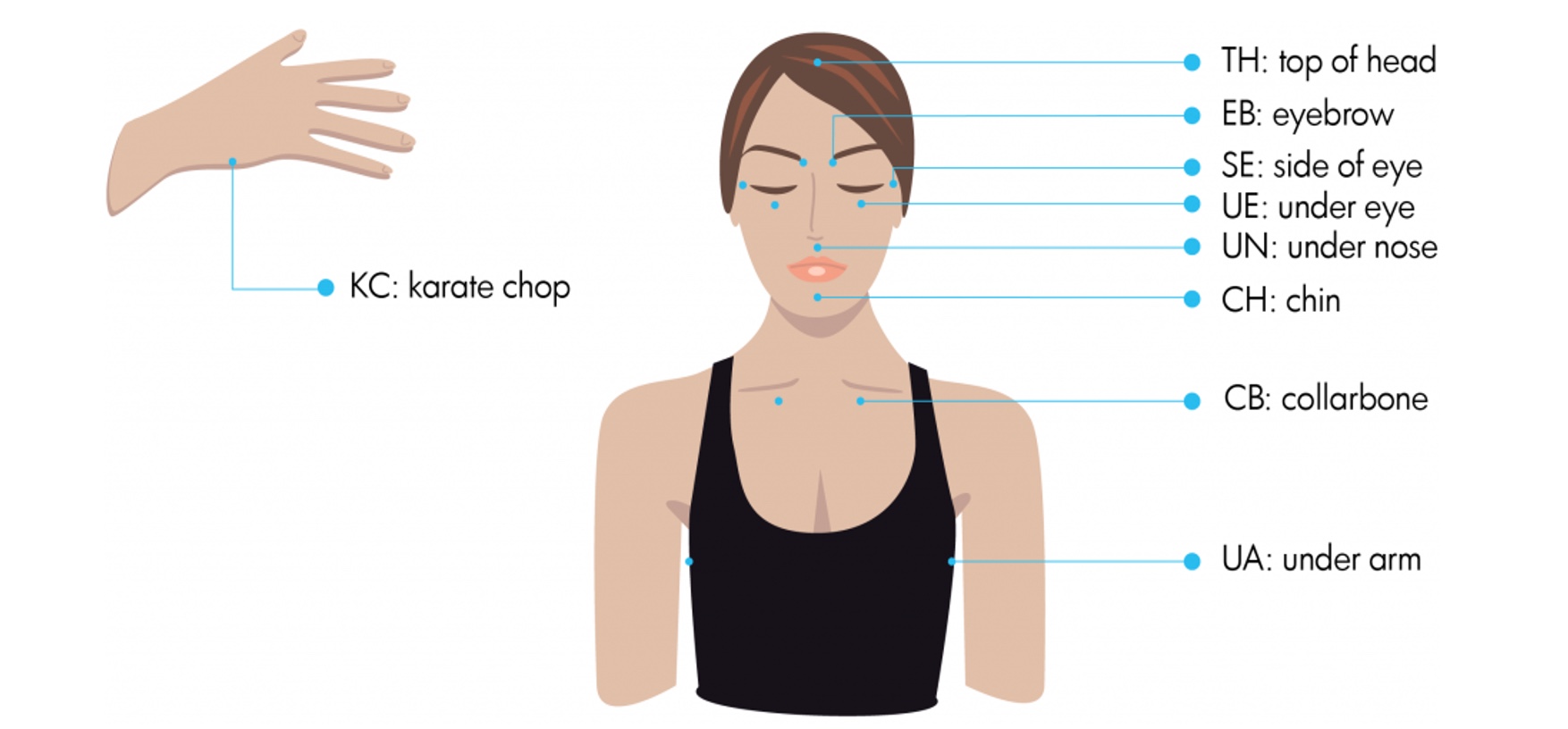

If you look at Figure 11, you will see the tapping points: the top of the head, eyebrow, side of the eye, under the eye, under the nose, the chin, the collarbone, under the arm, and the "karate chop" point on the side of the hand. We are going to walk through a tapping exercise together now.

Figure 11. Tapping points (Click here to enlarge the image.)

I will show you how these look. First, go to the top of the head, eyebrows, side of the eye, under the eye, under the nose, chin, collarbone, and then under one arm. You can refer to the diagram.

I am going to make statements, and then you will say them as well. For the karate chop point on the side of the hand, we will say, "Even though I feel this stress, I deeply and completely accept myself." You will say that two times. Think about a current stressor, perhaps one you wrote down earlier, and rate its intensity from 0 to 10.

Karate chop: Even though I feel this stress, I deeply and completely accept myself.

Top of the head: This stress.

Eyebrow: The tension I am holding.

Side of the eye: The anxiety in my body.

Under the eye: All this worry.

Under the nose: This feeling of overwhelm.

Chin: Holding on so tightly.

Collarbone: This stress I carry.

Under the arm: Letting go of stress, releasing what no longer serves me.

Repeat that sequence: top of the head (this stress), eyebrow (the tension I am holding), side of the eye (this anxiety), under the eye (all this worry), under the nose (overwhelm), chin (holding on), collarbone (this stress), and under the arm (letting go).

Take another deep breath. Tap lightly over your heart and say: "I give myself permission to release stress and feel calm." Now stop.

When you do this, you would typically go through the sequence three to five times. I have used this with many patients, particularly for minor traumas, and have seen its effectiveness firsthand. What is nice is that they can do it anytime they want; they do not have to be in my office like they would for Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR).

While the scientific underpinnings are somewhat controversial, it is a widely used self-help technique to relieve stress. It should be used in conjunction with other methods like mindfulness and cognitive behavioral therapy. I believe it is worth including because it is effective and helpful, even if part of that effect is placebo. I will take the placebo effect if it helps my clients feel better.

Digital Detox

There is a substantial body of evidence showing that digital usage, especially social media, is correlated with higher stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms. Research indicates that teenagers who spend three hours a day on social media are 50% more likely to experience anxiety and depression. While this may not be surprising, it is essential to remember the significant stress our digital lives can cause.

Literature now shows a clear social correlation between media usage and the likelihood of anxiety disorders. Furthermore, some researchers suggest that our constant screen time is affecting our attention spans, which are reportedly now shorter than those of a goldfish. We also face the "fear of missing out" (FOMO), where high social media use predicts higher anxiety, stress, and sleep disruption.

I often tell parents during coaching classes: no social media, no phones, and no computers in the bedroom at night. While it can be challenging to be a parent today, reducing time spent on social media can help decrease stress. You can implement easy changes, such as turning off notifications, banning phones during meal times, or adjusting your screen to black and white to reduce stimulation.

Designate tech-free hours and keep phones out of the bedroom. I bought an alarm clock—one where the "sun" comes up and music plays—so I don't need a phone to wake up. You remember those old-fashioned things? They work great.

You can also try the Forest app. For every minute you spend away from your phone, money is donated to plant real trees. If you leave the app to check your phone, your digital tree dies; if you stay focused, you earn coins to plant actual trees in the world. There is no Wi-Fi in the woods, but you will find a better connection there.

Take a minute to write down one digital boundary you can set today, such as turning off notifications or keeping the phone out of your bedroom tonight.

Less Stress at Work

Let's now shift our focus to addressing stress at work. Organizational support is crucial to achieving sustainable stress reduction and optimal work performance. This includes balancing shifts, ensuring adequate staffing, and improving team communication through clear expectations and structured hand-off times.

Psychological safety is also vital. In my next training series, I will focus specifically on psychological safety, emphasizing the importance of creating spaces for debriefing and open discussions. Wellness programs, including meditation rooms, counseling services, and exercise facilities, are becoming increasingly common in healthcare settings. Small studies show that even a 10-minute structured break can significantly reduce stress hormone levels in staff.

When I present these findings to healthcare executives, they are generally receptive. By showing them the physical and cognitive effects of stress on their workforce, they are much more likely to implement stress reduction measures in the environment.

What can you do for yourself? Start by encouraging better time management skills.

Prioritize: Focus on what must be done and try not to over-commit.

Create a Balanced Schedule: If possible, weave in time for emergencies.

Arrive Early: Try to get to work a few minutes early to avoid starting the day in a rush.

Set a Hard End Time: Tell yourself exactly when you plan to leave. If you find you can never go on time, you may need to reprioritize your daily tasks.