Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, From Overwhelm To Ease: OT Strategies For Anxiety Management, presented by Zara Dureno, MOT.

*Please also use the handout with this text course to supplement the material.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to identify the neuroscientific and biological reasons for anxiety.

- After this course, participants will be able to recognize common physical and emotional signs of anxiety in clients.

- After this course, participants will be able to list practical tools and strategies that clients can use to overcome their anxiety.

Introduction/Who I Am

I'm thrilled to share some practical tools with you today—strategies you can start using immediately after this presentation. When you leave here, you’ll have tangible skills you can apply in your practice or even your own life.

Before we dive in, you'll see the disclosures, limitations, and potential risks outlined. Feel free to take a moment to review those on your own.

Now, let’s look at the learning outcomes for this course. By the end, I’m confident you’ll be able to identify the neuroscientific and biological foundations of anxiety. We’ll explore what those mechanisms look like in the brain and body. I could talk about this topic endlessly—my passion for neuroscience runs deep, and you’ll see that come through—but since we only have an hour together, I’ll be distilling the information in an efficient and empowering way. My goal is for you to walk away feeling confident about the biological underpinnings of anxiety and how they connect to the lived experience of your clients.

We’ll also spend time recognizing the physical and emotional signs of anxiety. This is important not only so we, as practitioners, know when to intervene, but also so we can help clients recognize their symptoms sooner. That kind of awareness is a powerful first step toward self-regulation and healing.

Then, we’ll move into practical tools and strategies that clients can use to manage and overcome anxiety. I’ll be framing all of this through an occupational therapy lens, and I’m not shy about saying just how incredible OT is in this area. We are uniquely positioned to address anxiety in holistic, meaningful, and deeply rooted ways in everyday life. You’ll hear me gush a bit—okay, a lot—about our role and why it matters.

To share a bit about myself, I’m an occupational therapist with five years of experience, primarily working with individuals with chronic conditions. I had a pretty serious fall from a horse that resulted in significant pelvic injuries. That event marked the beginning of my own journey with chronic fatigue and chronic pain. My personal recovery from those experiences deeply informs my work today. You can read more about that journey on my website, which I’ll share with you later.

That recovery wasn’t easy, but it shaped my mission. I’ve become especially passionate about supporting people through physical and mental health challenges, particularly those that persist for more than three months. I specialize in this area through my private practice, where I work with individuals from around the world navigating conditions that require long-term, compassionate, and interdisciplinary support.

Occupational Therapy and Mental Health

Today, we’re focusing on mental health, a topic that often requires us as occupational therapy practitioners (OTPs) to broaden perceptions—both our own and those of others. In many settings, OTPs are primarily seen as physical health providers. People frequently assume we deal solely with physical rehab or behavior management, and while those areas are certainly part of our scope, they don’t reflect the full picture. Sometimes people acknowledge that we address cognitive health, but it's less common for them to recognize that we are also mental health professionals.

According to AOTA, we are indeed considered behavior and mental health practitioners. That’s a critical distinction—and one we often have to advocate for. We may find ourselves in situations where we need to educate clients, colleagues, and even other healthcare providers about the full scope of our role. Throughout this presentation, I’ll be highlighting exactly why our presence in the mental health space is not only relevant but essential.

What sets us apart is the unique, holistic lens we bring—one that centers on meaningful occupation and purposeful activity. These are fundamental to mental well-being and powerful tools for moving people forward in their mental health journeys. By helping clients engage in the things that matter most to them, we’re not just addressing symptoms—we’re restoring identity, purpose, and connection.

We’ll also be looking at how to apply a cognitive behavioral framework within our occupational therapy practice. This includes interventions that support clients both cognitively and behaviorally as they manage anxiety. We’ll explore psychoeducation to help clients understand what they’re experiencing, and we’ll go through relaxation techniques that can be immediately useful. While we won’t dive deeply into social skills training in this session, we will spend time discussing systemic desensitization and how it can be used effectively with our clients.

This is a space where occupational therapy has the potential to shine—and I’m excited to show you how.

Understanding Anxiety

Let’s take a moment to lay some groundwork so we can better understand the nature of anxiety. Within the DSM, there’s a wide range of conditions that fall under the umbrella of anxiety disorders. For instance, panic disorder is one of the more commonly recognized types. Then there’s panic disorder with agoraphobia, which involves a fear of leaving the home or being in situations where escape might feel difficult. Social phobias and specific phobias—like a fear of spiders—also fall into this category. In addition, post-traumatic stress disorder, acute stress disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder are all considered anxiety-related conditions. While they each have distinct features, what ties them together is that they all involve a dysregulation of the nervous system rooted in anxiety.

To conceptualize how anxiety functions, I find the ABC model to be a helpful starting point. This model begins with an “alarm,” which can be triggered by either an internal or external stimulus. Take, for example, a client with a specific phobia of spiders. The external stimulus—a spider—acts as the alarm. The client perceives the spider and immediately interprets it through a belief system, such as “This is dangerous” or “I’m going to get hurt.” From there, a coping behavior follows. That might look like running away, freezing, or even screaming—an automatic, sometimes unconscious, decision.

This process happens in layers. First, the stimulus itself, which may or may not be avoidable. Then the interpretation or belief about the stimulus. And finally, the coping response. While we can’t always control or eliminate the stimulus—especially when it’s internal, like intrusive thoughts or physical sensations—we do have much therapeutic opportunity at the level of belief and behavior. That’s where we can intervene most effectively. We can help clients shift how they interpret what’s happening and guide them toward more adaptive coping methods.

I like to think of it as a "show and tell" approach. We show the body safety cues through physical calming strategies and tell the body new narratives by reframing beliefs. This two-pronged approach helps rewire how anxiety is processed in the brain.

Speaking of the brain, it’s important to understand the interaction between the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex. The amygdala, our emotional fear center, reacts rapidly to perceived threats—whether real or imagined. It’s a bit like a toddler: reactive, impulsive, and disconnected from logic or time. In contrast, the prefrontal cortex is the logical part of the brain—it assesses, reasons, and puts things in perspective. When someone is experiencing anxiety, the amygdala tends to hijack the system. It doesn’t know the difference between a thought like “What if I fail?” and an actual physical danger.

Our goal in therapy is often to strengthen the connection between these two parts of the brain. Many anxiety management techniques help develop a more productive relationship between the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex, allowing clients to pause, evaluate, and respond rather than react impulsively. By doing this, we support clients in reclaiming a sense of control, even when the alarm bells are ringing.

Food Adversion Example

A useful example to illustrate how anxiety can take hold is with something like a food aversion. Imagine you ate macaroni and cheese one day and then became sick afterward. Even if the food didn’t directly cause the illness, your brain might link the two experiences. That association becomes deeply embedded in your subconscious—your belief becomes that mac and cheese is something that will make you sick. So the next time it’s offered, you cope by avoiding it altogether.

This is a simplified version, of course, but it shows how one negative experience can shape our beliefs and, in turn, influence our behaviors. The initial experience—getting sick—acts as the alarm. The belief shifts to “this food is dangerous,” and the coping response becomes avoidance. From that point forward, your reaction to that particular stimulus is no longer neutral; it’s heightened and charged with emotion. You may experience a strong physiological response—nausea, racing heart, even panic—just from the sight or smell of the food.

This same process is often at the core of how anxiety develops more broadly. A distressing experience—especially one that overwhelms the nervous system’s capacity to regulate—can fundamentally alter how we interpret certain stimuli. From that single event, our belief systems change, and so do our coping behaviors. These altered responses can then become ingrained, making it more difficult to engage with certain people, places, activities, or situations without triggering that same pattern of alarm.

Recognizing this pattern helps us understand how seemingly irrational responses often have a logical origin in the body’s effort to protect itself. It also reinforces why therapeutic work-around beliefs and coping strategies are so critical in helping clients move forward.

The Nervous System

I could talk about the nervous system for hours—it’s truly one of my favorite topics. But in the interest of time, I’ll keep it brief for today. I do go into this in much more depth elsewhere, but for now, I want to give you a quick overview, especially as it relates to anxiety.

Lately, there’s been a surge of interest in the nervous system, which I think is fantastic. The more we understand how our bodies respond to the world around us, the more empowered we are to work with those responses, not against them. When discussing regulating the nervous system, we often refer to the autonomic nervous system.

The nervous system is divided into the central and peripheral systems. The central nervous system includes the brain and spinal cord. The peripheral nervous system consists of the nerves that branch out from the brain and spinal cord, transmitting information throughout the body. Within the peripheral system, we have two main components: the somatic and the autonomic nervous systems.

The somatic nervous system is responsible for voluntary movement—things like lifting a glass of water or standing up from a chair. These are actions we consciously control. The autonomic nervous system, on the other hand, operates below the level of our conscious awareness. “Auto” means self-regulating, and this part of our nervous system takes care of all the functions we don’t usually think about—things like heartbeat, breathing, blood pressure, salivation, and digestion.

The autonomic nervous system also plays a central role in how we respond to stress and perceived threat, which is where it becomes especially relevant to anxiety. Think of it this way: if a lion suddenly burst into the room while reading this, you wouldn’t want to sit there and reason through what your body needs to do next. You wouldn't want to have to think, “Okay, time to increase my heart rate, send blood to my limbs, and stop digesting lunch so I can run.” Your body would already be doing it—instantaneously and automatically. Your autonomic nervous system at work is kicking in to help you survive.

This system is fast, efficient, and deeply tied to our sense of safety, or lack thereof. Understanding how it functions gives us powerful insight into the physiological basis of anxiety and how we can support our clients in regulating their nervous systems when they’re stuck in those survival states.

Survival Modes

Our survival modes are built into us for one simple reason: to help us stay alive when we perceive danger. These modes—fawn, flight, fight, freeze, and faint—are hardwired responses that the body initiates automatically in response to threat. Understanding them is key to working with anxiety in a therapeutic context.

- Fawn – Give the threat (e.g., the lion) something it wants to avoid harm.

- Flight – Run away from the danger.

- Fight – Confront and fight the threat.

- Freeze – Stay completely still and avoid movement.

- Faint – Lose consciousness in response to extreme stress.

The fawn response involves appeasing or giving the perceived threat what it wants to avoid harm. If we stick with the lion example, fawning might look like tossing a piece of meat in the opposite direction, hoping the lion goes after that instead of you. It’s a form of strategic submission—doing whatever it takes to stay safe.

The flight response is probably the one most people think of first. It’s the instinct to run—to escape the danger entirely. If that’s not possible, the body may shift into fight mode, preparing to confront the threat head-on, potentially with physical or verbal aggression.

Freeze is another survival response that often gets overlooked. In this state, the body becomes still, as if immobilized. Think of the classic “deer in the headlights” reaction. Externally, it might look like someone is calm or shut down, but internally, their mind can be racing, flooded with fear or panic. It’s a kind of internal alarm with an externally muted expression.

Then there’s faint, which can look like dissociation, extreme fatigue, or even actual loss of consciousness. This is the body’s last-resort effort to protect itself by mentally or physically checking out of a situation that feels inescapable.

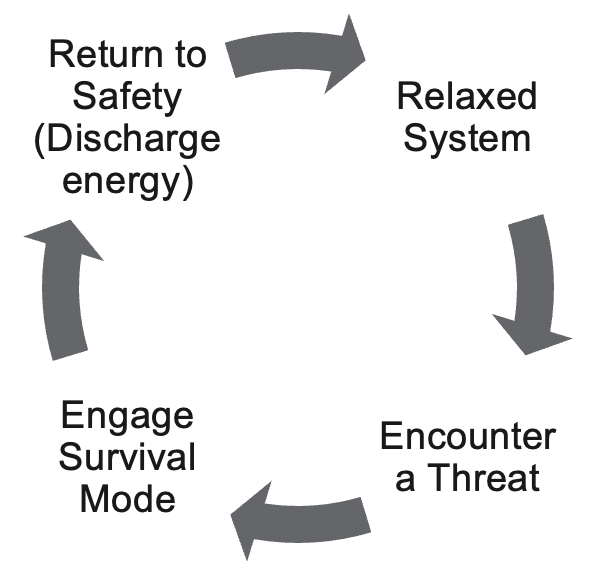

When the nervous system functions optimally, we experience a complete stress cycle, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The stress cycle.

We typically begin from a relaxed baseline, much like many of us might feel right now. Then we encounter a perceived threat, such as the proverbial lion, and a survival response is activated. After escaping or resolving the danger—say, by running into a room and locking the door—we need to discharge the energy that’s built up in our system. That discharge is an important part of the stress cycle. Animals do this instinctively; for example, a dog might shake itself off after a stressful event. Humans might discharge that energy by crying, laughing, yelling, pacing, or even trembling. These are all natural ways our bodies return to a regulated state.

But for individuals with anxiety disorders, the system doesn’t always return to baseline so easily. In many cases, they’ve experienced a single overwhelming event or a buildup of smaller, chronic stressors—maybe a traumatic experience, a chaotic home environment, or a life filled with unpredictability. These experiences often create more active neural pathways to the amygdala, the part of the brain responsible for detecting threats, which then becomes more sensitive and reactive.

This results in a nervous system that remains on high alert, stuck in a prolonged fight-or-flight state. The amygdala begins to interpret even minor stimuli as major threats. For example, someone lightly tapping them on the shoulder might provoke a much stronger response if their system is already activated. It’s like when you're watching a horror movie—your nervous system is already heightened, so even a slight startle feels amplified. Contrast that with the same tap while relaxing peacefully on the couch—it’s the same stimulus, but your system reacts very differently based on your baseline.

Simply helping clients understand this—explaining how their nervous system works, what the stress cycle looks like, and why their reactions might feel out of proportion—can be incredibly empowering. It gives them a framework for making sense of their experiences and restores a sense of agency. When clients gain that understanding, they’re often able to approach their anxiety with more compassion and curiosity, rather than frustration or shame.

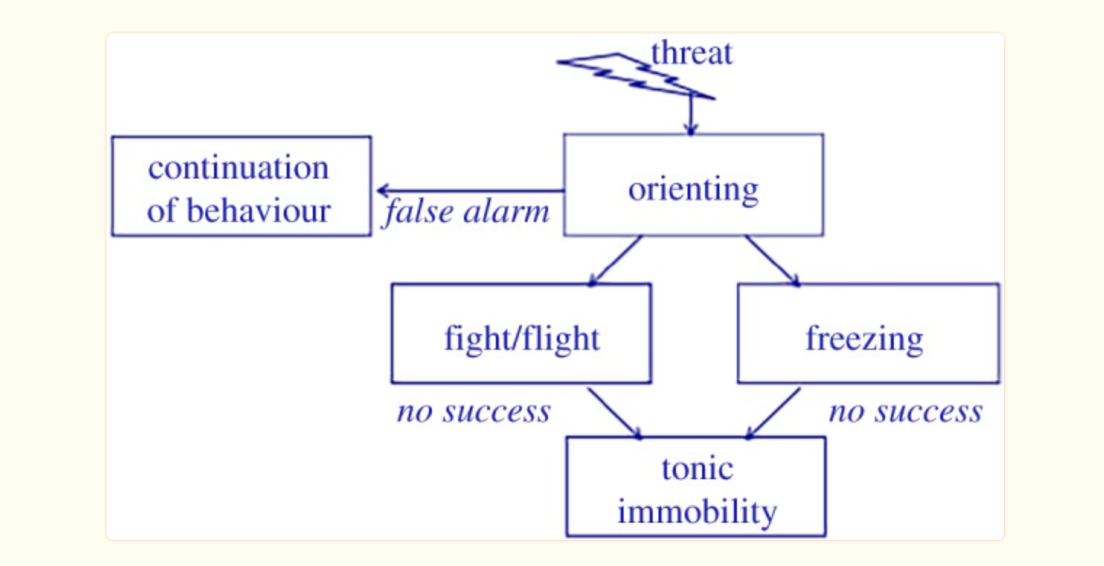

Schematic of Routes of Defensive Behavior

When we understand something, we gain more personal control over it. That’s why psychoeducation can be such a powerful tool. As OTPs, one of the most valuable things we can offer our clients is this kind of education. It not only informs but also empowers them to navigate their own experiences better.

When someone is chronically in a state of nervous system dysregulation, a typical result is a sense of disorientation. This can show up in different ways—feeling disconnected from the body, losing track of time, or having difficulty staying grounded in the present moment. To illustrate what this might look like, I’d like to share an example.

Figure 2. Schematic of routes of defensive behavior (adapted from Hagenaars et al., 2014. (Image CC BY 4.0).

Let’s say you’re walking through the woods. I live in British Columbia, Canada, so when I go for a walk in the forest, there’s a decent chance—not a guarantee, but a fair possibility—that I might encounter some wildlife. So imagine you’re in the woods, and you hear a loud noise. The very first thing your body and brain do is orient to that sound. You turn your head, scan the area, and try to understand it.

If you turn and see a squirrel, your nervous system likely stays calm. You realize it’s a false alarm, your system settles, and you keep walking. You’ve oriented to the stimulus, recognized it’s not a threat, and stayed regulated. But if you turn your head and see a cougar, your nervous system will kick into a survival response. You might go into fight, flight, freeze, or even faint—also called tonic immobility. The fawn response isn’t always included in traditional models, but it’s also a valid and recognized survival response.

Now, when someone has chronic nervous system dysregulation, like what we often see in individuals with anxiety disorders, that orienting system doesn’t function quite the same way. Instead of turning to assess the sound and evaluating whether it’s truly a threat, their system skips the orienting step altogether. Even a minor or neutral stimulus triggers a survival response—usually flight.

That’s why people with anxiety can seem disproportionately reactive to situations that don’t appear threatening from the outside. They may feel intense anxiety about driving, going to the store, or having a social interaction—things that don’t pose a real danger. The issue isn’t the event itself, but their nervous system isn’t pausing to check if the threat is real. It’s automatically defaulting to a fear response.

Part of our role is to help clients rebuild that orienting system. And one way we can begin that process is by offering psychoeducation—helping them understand what’s happening in their body, why it happens, and how we can support the nervous system to re-engage with that essential pause before reacting. That awareness alone can be the first step toward re-regulation.

Zebra Analogy

Another analogy I often use to help explain this concept is the story of a zebra. Imagine a zebra that grows up in an area where lions constantly surround it. Every day, there's a real threat to its safety. So over time, that zebra becomes highly attuned to danger—every rustle in the bush, every unexpected sound triggers a fear response. It's living in a heightened state of alert because it has to survive.

Now, imagine that one day, a hunter comes in and removes all the lions from that region. There are no longer any actual predators, but the zebra doesn’t know that. It continues to respond to every rustle in the bushes as if a lion is still there. Its nervous system doesn’t automatically update just because the threat is gone. It’s still operating from a place of survival because that’s what it learned to do.

This often happens in humans, especially when we experience threats early in life. Whether it’s a single overwhelming event—a big T trauma—or an accumulation of smaller, ongoing stressors—what we call little T traumas—the nervous system adapts by staying on high alert. It learns that the world is unpredictable or unsafe, and it becomes wired to scan for danger, even when that danger is no longer present.

The nervous system often interprets a wide range of situations as potential threats. This can show up in what I sometimes describe as the anxiety “latching” onto something specific. For some of my clients, that takes the form of health anxiety. For others, it's driving or social interactions. The anxiety doesn’t always match the objective level of risk—it’s more about the body trying to make sense of the internal state of activation. The system says, “Something must be wrong.” It finds a focal point to attach that sense of danger to.

Helping clients understand that this is a nervous system pattern—not a flaw in who they are—can be incredibly validating. It also opens the door to working with that pattern through tools that bring the system back into regulation.

Intervention

Orienting

One of the first things we can do to support our clients is help them begin to rebuild their orienting system. The amygdala—our brain’s fear center—is responsible for processing anxiety and initiating survival responses like fight, flight, freeze, fawn, or faint. But what’s important to understand is that the amygdala isn’t timestamped. It doesn’t have strong connections to the parts of the brain that process time, place, or context. That means when it’s activated, it can feel as though a past threat is happening right now, even if the current moment is safe.

Because of that, one simple but powerful practice is intentionally looking around and orienting to the present environment. Helping clients get into the habit of physically scanning their surroundings—looking left, right, up, and down—and saying to themselves, “I’m safe right now,” can be incredibly grounding. It may seem obvious on a logical level. Of course, we know we’re not in danger. But the deeper, emotional part of the brain doesn’t register logic—it responds to perceived threat.

So when we guide clients through this kind of present-moment orientation, we’re helping their nervous system catch up to reality. We communicate directly with the amygdala and say, “Look around. There’s nothing here trying to hurt you. You’re safe enough.” That phrase—“safe enough”—can be especially helpful because it acknowledges that we don’t need to feel 100% safe to begin regulating. We just need to help the nervous system recognize that the danger it’s bracing for isn’t happening right now.

Anchor

Another practical way we can help clients build their orienting system is by guiding them to list concrete facts about themselves and their environment. This might sound simple, but it’s incredibly grounding. I often encourage clients to say things like, “I am [this many] years old,” “I live in [this city],” “Today is [this date],” and “These are some things I enjoy.” These statements help bring them back to the present moment and reinforce the message: "Right now, I’m not in danger," and "Right now, I’m safe enough."

This kind of orientation can be a regulatory strategy in itself. It helps acknowledge, “Okay, I’m in fight or flight right now,” without judgment. Many of our clients come in with the belief that there’s something wrong with them. They’ll say things like, “I’m just an anxious person,” “I’m broken,” or “I’m bad.” But when we offer psychoeducation, we can help them reframe that thinking. We can explain that what they’re experiencing is not a personal flaw—it’s a normal nervous system response to feeling unsafe.

By recognizing that what’s happening is just fight or flight, we begin to take the shame out of the equation. At that moment, we can remind them: you are safe enough. There’s no immediate threat in your environment or in your body. And for clients with chronic conditions—like chronic pain or chronic fatigue—this is especially important. Many of them interpret their physical symptoms as signs of danger. They’ll say, “This pain means something is wrong,” or “This fatigue must mean I’m in harm’s way.” But the truth is, these sensations are not inherently dangerous. They’re signals, yes—but they’re not threats.

Teaching clients to respond with “I am safe enough” can be incredibly effective. I used to use “I am safe,” but I’ve come to prefer “safe enough” because it more accurately reflects reality. We’re never completely safe—there’s always some unpredictability in life. An asteroid could fall, sure, but that’s not likely. Saying “I am safe enough” offers just enough reassurance to calm the nervous system without dismissing the complexity of the world.

Finally, we always want to validate their experience. It’s human to feel anxious—it’s a normal response. We’re dealing with a momentary misunderstanding between the brain and the body—a miscommunication about how much protection is needed right now. When we can name it without judgment, we help our clients return to a place of regulation and self-compassion.

The 5 Fs

One of the common traps I see clients fall into—especially when they’re struggling with anxiety—is what Dr. Howard Schubiner refers to as the Five Fs. He originally introduced this concept in his book Unlearn Your Pain in the context of chronic pain, but I’ve found it incredibly relevant when working with anxiety as well. As I go through these, you might think about yourself or bring to mind a particular client and consider whether any of these patterns resonate.

When anxiety shows up—whether as racing thoughts like “What if? What if this is bad? I don’t know how to handle this!” or as physical sensations like a tight chest or a pounding heart—the way we respond can either help regulate the experience or intensify it. If we react with fear, frustration, hyper-focus, an urge to fix, or a desire to fight the feeling, we often end up making the anxiety worse. It’s like throwing fuel on an already burning fire.

Here’s an analogy I use often: imagine a toddler comes up to you and says, “There’s a monster under my bed.” If you respond with fear—“Oh no! You’re right! There’s probably a monster, and it’s going to eat you!”—that child is going to feel more terrified, not less. On the other hand, if you respond with frustration—“Oh, here we go again with the monster thing. Why do you always do this?”—That child will likely feel dismissed and alone. Hyper-focusing might look like getting down on your hands and knees, scanning every inch under the bed—“Where is it? Is it moving? Has it gotten closer?” Again, that just confirms to the child that this monster must be real and dangerous.

Trying to fix the situation with blame—“You know what? You’re the problem. If you didn’t keep saying there was a monster, we wouldn’t have to deal with this!”—would be deeply hurtful. Finally, fighting the fear creates a kind of inner battle: “This shouldn’t be happening! I hate this! I need it to stop!” That inner resistance adds another layer of stress and can prolong the dysregulation.

The most common responses I see in clients are either fear of their anxiety or a desperate need to fix it. Many clients are so afraid of having a panic attack that they actually trigger one through the fear itself. Others are so focused on trying to fix or eliminate their anxiety that they end up repressing it—pushing it down, ignoring it, denying it. But repression doesn’t resolve the feeling. It’s like trying to hold a beach ball underwater. The longer you hold it, the more pressure builds; eventually, it bursts back up with force.

Helping clients recognize these patterns and respond differently—to witness anxiety without judgment, to validate it without fueling it—is a key part of the therapeutic process. It shifts them from reacting to regulating, from fear to understanding. And that shift can make all the difference.

What Do We Do Instead?

We can’t repress what we feel—not if we want real healing. What we can do is learn how to sit with anxiety, to tolerate it, and to build a relationship with it, rather than trying to push it away. The goal isn’t to eliminate anxiety entirely. It’s to expand our capacity to be with it, to understand it, and to move through it. So the question becomes: how do we teach our clients to do that?

It starts with compassion, surrender, acceptance, and cultivating a felt sense of safety. The orienting skill I mentioned earlier—reminding ourselves, “I am safe enough; this is a normal reaction to feeling unsafe”—is one of the foundational tools that helps create that safety. It begins to rewire the nervous system’s response by saying, “Yes, I’m dysregulated, and I’m also safe enough in this moment.”

It’s like turning toward a child who believes a monster is under the bed. Instead of brushing them off or feeding their fear, we crouch down beside them and say, “Okay, let’s go take a look together.” That simple act of presence—of saying, “I’m here with you”—shifts the whole experience. We’re no longer resisting the fear but moving through it with care. This is essentially what we’re helping our clients do internally.

It’s a form of inner parenting or inner child work. The internal dialogue becomes, “I’ve got you. I love you. I’m here with you,” instead of, “This is bad. I need this to stop. I have to fix it.” That gentle turning toward the discomfort—rather than away from it—is where the healing begins.

When we meet anxiety with compassion instead of resistance, it often loses its intensity. The fuel gets pulled from the fire, and the fire naturally starts to die down. This doesn’t mean the anxiety disappears instantly, but it transforms our relationship to it. Rather than being a battle, it becomes something we can sit beside, observe, and eventually release. And that’s a powerful shift—for both clients and ourselves.

Preoccupation Behaviors

We also want to be attentive to whether our clients are engaging in preoccupation behaviors—those patterns that often emerge when someone is dealing with anxiety. These behaviors can be subtle or obvious, but they usually serve as attempts to manage the internal discomfort of anxiety. For example, clients might check their phone, Google their symptoms repeatedly, or swing to the other extreme and avoid all medical information altogether. They might ask for reassurance again and again, or turn to habits like drinking, binge eating, or endlessly scrolling through Netflix or TikTok.

Some clients might monitor their body obsessively—what we often call body scanning—or plan excessively, creating detailed lists or routines meant to reduce uncertainty. You’ve probably had that client who says, “Just tell me exactly what to do, and how many times to do it,” which reflects a strong need for control. All of this is part of that “C” in the ABC model—the coping response. And while these behaviors are attempts to feel better, they tend to perpetuate the anxiety rather than soothe it.

As occupational therapy practitioners, this is where our holistic lens becomes incredibly valuable. We can recognize these preoccupation behaviors for what they are—coping strategies that have simply become maladaptive. Then, rather than reinforcing those patterns, we can begin to guide clients toward more meaningful engagement gently. We can ask, “What’s something you value? What would bring you a sense of purpose or connection today?” This shift moves the client from a place of anxiety-driven behavior into a space where they’re reconnecting with occupations that support their well-being.

And this is where your clinical reasoning shines. I know you’re already doing this kind of analysis—looking at routines, motivations, habits, and environments to understand the whole picture. We’re not just managing symptoms; we’re helping clients return to daily activities that nourish and regulate the nervous system. That’s the heart of what we do.

Engaging in Meaningful Activity

In these moments, we can invite clients to ask themselves, “What would be a meaningful activity for me to engage in instead of this preoccupation behavior?” This is where we, as occupational therapy practitioners, can begin to shift the focus from avoidance or over-control to connection and regulation. It’s also where the concept of glimmers comes in.

You’ve likely heard of triggers—those things that send the nervous system into a survival response. Glimmers are the opposite. Glimmers are small, often subtle moments that bring us into a parasympathetic, regulated state. They activate a sense of calm, safety, or even joy in the nervous system.

Glimmers are highly personal. Some of my glimmers include petting a dog, drinking a warm cup of hot chocolate, smelling peppermint or lavender, or watching a beautiful sunset. These little experiences help my nervous system settle. They’re not dramatic or overwhelming—they’re gentle cues that say, “You’re safe. You can soften here.” As practitioners, we can support our clients in identifying their glimmers and weaving them into their daily routines.

We can also think about activities that promote the release of endorphins. Our nervous system can better regulate itself when we have more endorphins on board. This might involve encouraging movement, if that’s accessible for the client. It might also include engaging in pleasurable or creative activities, especially ones that bring about a flow state. When someone is immersed in a creative task—painting, playing music, gardening, crafting—that deep engagement is neurologically incompatible with the anxious fight-or-flight state. Flow helps bring the nervous system back into balance.

You have the tools to see beyond symptom management and help clients reconnect with meaningful, regulating, and joyful activities. Whether it’s gentle movement, art, nature, music, or simply sensory experiences that feel grounding, these small shifts can create profound nervous system change, and that’s the kind of work that truly supports long-term healing.

How to Affirm Safety During Activities

How can we affirm safety during activities, or how can we affirm safety in general, outside of the orienting technique? The orienting technique is of the mind—we’re saying, I am safe enough. That’s the mind. That’s the tell part of the show-and-tell. But we also need to work with the body. So I’m going to give you some extra little things we can think about for both of these systems so that when we’re approaching anxiety, we’re doing it from a mind-body perspective—because they’re interlocked. We can’t work on one without working on the other. We have to work on both.

Some techniques for anxiety are very top-down—they only work with the mind. Some techniques are bottom-up—they only work with the body, somatic techniques. I think it’s best when we work with both.

Mental Affirmations of Safety

When it comes to mental affirmations of safety, we can help walk a client through some things to consider when they’re feeling anxious. One approach I often use is guiding them through four specific questions. This is all on the mental level of addressing anxiety—helping the client engage with their thoughts and bring awareness to what’s happening in their mind. We’ll talk about the body level in a moment, but starting with these mental prompts can be a beneficial entry point.

4 Things to Consider When Anxious

On the mental level of anxiety, sometimes just thinking through the anxiety itself can bring relief. When a client comes to me feeling anxious, one of the tools I use is a set of four simple but powerful questions. These are especially helpful when the anxiety is rooted in future thinking—the kind of “what if” worry that spirals quickly into worst-case scenarios.

The first question I ask is: What’s the best that could happen? When someone is anxious, they’re usually focused only on negative possibilities. Their mind isn’t naturally going to the best-case scenario, so we intentionally bring that into the conversation.

Next, we ask: What’s the worst that could happen? Chances are, they’re already thinking about that, because anxiety tends to fixate on the most extreme outcomes.

Then we move to: What’s the most likely outcome? This helps them return to a more balanced perspective—one that lies between the best and the worst. Most of the time, the reality is much less catastrophic than the anxious mind assumes.

Finally, we ask: If the worst happened, how would you cope? What skills would you use? Who would you reach out to? What would that look like in a year? In five years? This step is empowering because it shows them that even in a difficult outcome, they still have agency, resilience, and tools they can rely on.

These questions may seem simple, but I’ve seen clients experience significant relief by working through them in a session. Sometimes we go through them together, and other times I encourage them to journal their responses. They’re beneficial for that mental, “what if” style of anxiety—the cognitive kind that spins stories and builds pressure in the mind.

It’s also a good reminder that anxiety manifests on two levels: in the mind through thoughts and worries, and in the body through physical sensations like a tight chest or a racing heart. So, while these four questions address the mental side, we’ll also want to support the body, which we’ll discuss shortly.

Challenge Thoughts

We can also help clients begin to challenge their thoughts a little, especially when those thoughts are clearly contributing to anxiety. This approach is based in CBT—cognitive behavioral therapy—which I appreciate and use often. That said, I’ve also found that it’s even more effective when we pair this kind of cognitive work with somatic techniques, because working with the body alongside the mind gives us a more complete picture of healing. So I’ll walk you through this thought-challenging process, and then we’ll shift into some of the more brain-retraining approaches in just a bit.

When a client has a thought that’s not particularly helpful—something anxious or distorted—we can often recognize that their logical mind isn’t entirely on board. They may be caught up in a belief that’s exaggerated or simply not true. In these cases, we can gently invite them to reflect: Is this a helpful thought for you right now? And if not, what might be a more helpful thought?

It’s important to remember that we don’t want to swing too far in the opposite direction. So for example, if a client says, “I’m terrified that I’m going to get COVID, and I’ll end up with long COVID and be bedridden,” a balanced thought isn’t “I’m never going to get COVID.” That’s also unrealistic—we can’t predict that. What we’re looking for is something more grounded, something that invites in safety and logic without making false promises. A more balanced thought might be, “Even if I do get COVID, most people recover quickly, and I trust my body’s immune and nervous systems to support me.” That shift is subtle but powerful.

We can walk through these reframes with our clients. And depending on our scope and jurisdiction, some of us may also be able to use a formal CBT thought-challenge worksheet. But even without going fully into CBT, we can absolutely support clients in gently exploring their thoughts and considering alternative perspectives. We might ask: Is there another way to look at this? What if I approached this like an experiment? How high are the stakes, really?

One of my favorite questions to ask is: What would you say to a friend in this situation? So often, we are much more compassionate and reasonable with others than we are with ourselves. That question can help shift clients into a more self-supportive mindset.

Once a client lands on a more balanced thought, traditional CBT encourages them to repeat that thought several times until it becomes more familiar and eventually more believable. I find that helpful, but I also like to go a step further and incorporate techniques that reach the subconscious mind. Since roughly 95% of our mental activity is subconscious, only working at the conscious level is like tending to the tip of the iceberg.

To support this deeper shift, I developed an acronym called VIBE, a brain retraining technique that helps clients internalize new, more helpful thoughts. I won’t go into that here because we’ve got a lot of other skills to cover today, but if you’re interested, it’s available on my YouTube channel, Uplift Virtual Therapy.

For now, I encourage you to practice guiding clients through thought challenges, helping them develop more supportive beliefs, and repeating those beliefs until they begin to feel true. This process can be surprisingly effective in reshaping how clients relate to their anxiety.

Defusion: You Are Not Your Thoughts

We can also begin to help clients defuse from their thoughts. So often, when a client is experiencing anxiety, they completely believe the thought that’s showing up—“Something bad is going to happen,” for example. That belief feels absolute. There’s no space between the thought and the self.

I often use the analogy of thoughts being like your hands. If your thoughts were your hands and you brought them up over your eyes, you'd only be able to see through that narrow lens. That’s what it can be like when someone fully believes an anxious thought—it clouds everything else. But we don’t need to “chop off the hands,” so to speak. We’re not getting rid of thoughts altogether. Instead, we gently lower the hands, just enough to get a more accurate perspective of reality. In other words, we help the client step back and separate slightly from the thought.

For example, instead of the thought “I’m not good enough,” which feels final and self-defining, we help the client shift to “I notice I’m having the thought that I’m not good enough.” That small change creates distance. It turns the thought into an observation instead of an identity. And that shift matters—it helps them remember that they are not their thoughts.

We can model this in how we speak with clients, too. When a client shares something anxiety-driven, rather than responding as though the thought is fact, we might say, “It sounds like you’re having the thought that something bad is going to happen.” That phrasing helps build a little space between the client and their anxious thinking. Over time, this gives them permission to consider the idea that not every thought needs to be believed.

So that’s a bit on the mental side of things. I know we could go much deeper into this, but I’ve just given you a few key tools: those four questions to challenge anxious thoughts, and a simple approach to defusion. These are accessible strategies you can use in session to begin working with the cognitive layer of anxiety.

Somatic Affirmations of Safety

Somatic techniques are communicating through the body that we're safe.

Co-regulation

One of the most powerful ways we can support our clients in regulating their nervous systems is by being regulated ourselves. How we show up to a session—our tone, our presence, our energy—has a direct impact on the client’s nervous system. So the question becomes: between sessions, what can we do to regulate our own nervous systems, so that when we’re with a client, we’re grounded and available as a source of co-regulation?

There’s a really fascinating study that speaks to this idea. Researchers had participants wear sweat pads while doing two different activities—skydiving and working out at the gym. Later, a separate group of participants was placed in an MRI scanner and asked to smell the sweat pads. They weren’t told anything about what they were smelling. They had no idea which pads came from which activity.

What’s incredible is that when participants smelled the sweat pads from the skydivers, their amygdalas lit up. Even without knowing what they were exposed to, their bodies detected the fear—and responded accordingly. The study is a reminder that our nervous systems communicate with each other in ways that go far beyond words. We pick up on each other’s regulation—or dysregulation—without consciously realizing it.

That’s why our own self-regulation is so important in the therapeutic space. Of course, we’re not aiming for perfection. We all have moments where we’re stressed or dysregulated—that’s human. This isn’t about beating ourselves up or worrying that we’re “ruining our clients.” But it is about practicing the same techniques we teach—so that we’re grounded, resourced, and steady in our presence.

When we’re regulated, we become a safe anchor for our clients. Through our tone of voice, our eye contact, the pace of our speech, our ability to listen and validate, we send subtle but powerful cues to the client’s nervous system that say: It’s safe enough to be here. You’re not alone. You can begin to settle. That’s the essence of co-regulation, and it starts with us.

Somatic Tracking

Now, here is a practical strategy for somatic affirmation of safety that you can use with your clients. It’s called somatic tracking. This strategy is borrowed from pain reprocessing therapy and is beneficial for anxiety as well.

Mindfulness. The mindfulness portion of somatic tracking is about objectively describing the sensation. In pain reprocessing therapy, we’re usually talking about pain, but when working with anxiety, we shift our focus to the physical sensation associated with that anxiety. So you would help the client objectively describe what they’re feeling. For example, if I were feeling anxious right now, I might say, “I can feel a constriction in my chest. I can feel my heart beating a little faster. I can feel some tension in my muscles.”

We’re giving that sensation permission to be there, without trying to change it, fix it, or avoid it. This is where we’re really practicing staying out of those five Fs. Instead, we’re practicing compassion, surrender, and a felt sense of safety. We’re leaning into curiosity and interest. The goal isn’t to get rid of the anxiety—it’s simply to witness it without reacting to it.

That reaction is what tends to fuel the anxiety and keep it stuck. But when we observe the sensation with openness, we shift our relationship to it. Sometimes I use the analogy of snorkeling and spotting a fish—you’re just watching it move past. That fish is the anxiety. Or you might imagine leaves floating down a stream or clouds drifting across the sky. Whatever image works, the idea is the same: you’re noticing, staying present, and staying curious, but you’re not trying to control it. You’re allowing the experience to be there, and that alone can begin to shift how it feels.

Safety Reappraisal. Then, we reappraise safety. We help the client acknowledge, “Yeah, this is uncomfortable, but it’s safe.” This is a safe signal that the nervous system is misinterpreting. We don’t have to live in fear of it.

I often use the analogy of a fire alarm going off when there’s no fire. If a fire alarm went off in my house right now, I probably wouldn’t panic—I’d assume someone’s cooking dinner or burning toast. But if I heard that alarm and saw smoke, my reaction would be very different. The presence or absence of actual danger changes everything. Anxiety is often that false alarm—loud, uncomfortable, but not signaling a real threat.

Another analogy I use is a dog barking at people walking past the window. The people aren’t dangerous, but the dog doesn’t know that—it’s just reacting. Similarly, the nervous system can get stuck in this mode of barking at everything. We help the client understand: This is a false alarm. There’s no real threat here.

So we reframe it as sore, but safe. The sensation is uncomfortable, but not dangerous. It’s a safe signal—just one that’s being misread. Helping clients internalize this shift is a key part of breaking the cycle of fear.

Positive Affect Induction. And then there’s positive affect induction, which is about bringing some lightness into the process, like making your client laugh. So if you're leading a somatic tracking session, you might throw in a gentle joke or something playful to shift the tone. If joking doesn’t feel natural to you, you can encourage the client to smile. It doesn’t have to be forced or exaggerated—it’s about inviting a small moment of lightness.

The goal here is to help soften the observation. We’re not making fun of the experience or dismissing it, but we’re bringing in a bit of warmth, humor, or gentleness. That little shift can go a long way in supporting regulation and helping the client feel safer while staying with the sensation.

Pendulation

And then in pendulation, what we’re doing is helping the client find a place in the body that feels pleasant or neutral. This is important because the mind naturally wants to hyper-focus on the unpleasant sensation associated with anxiety. So we’re gently rewiring the brain by encouraging it to notice something else—something that feels more stable, more comfortable, or at least neutral.

If the client can’t identify a neutral or pleasant area in the body, we can help them create one. That might be as simple as rubbing their hands together, holding their face, or giving themselves a gentle self-hug. These small actions can generate a sensation that feels grounding or soothing.

The process of pendulation involves focusing first on that pleasant or neutral sensation, then shifting awareness back to the unpleasant sensation—just observing it, not reacting to it—and then returning to the neutral or pleasant sensation. This back-and-forth helps regulate the nervous system by expanding the client’s window of tolerance and reducing the intensity of the distress over time.

If this doesn’t feel completely clear, I have a few guided examples on my YouTube channel, Uplift Virtual Therapy. There’s one for anxiety, one for pain, and one for fatigue. Each one walks through the steps in a calm, simple way, so feel free to check those out if you’d like more support or want to recommend them to clients.

We can also help clients retrain their breathing patterns, which is another great way to support regulation.

Breathe (SEND)

So I came up with an acronym that brings together several pieces of breathing science in a simple, memorable way. The acronym is SEND, and it outlines the core elements we want to focus on when teaching clients how to retrain their breath for nervous system regulation.

The first part of SEND is slow and soft. We want our clients to breathe slowly and gently, because this communicates safety to the nervous system. Ideally, we’re aiming for four to six breaths per minute, which is quite slow, but this pace is incredibly effective for calming the system. One way to help clients achieve this is by pausing briefly at the top and bottom of each breath. So, for example: inhale, pause, exhale, pause. This naturally slows the rhythm and helps regulate the nervous system.

The breath also needs to be soft. A soft breath sends safety cues, while sharp or shallow breathing can signal danger to the body, even when there is no threat. I like to remind clients that we breathe around 22,000 times a day. That number often catches their attention and helps them understand why retraining breath is so important. The way we breathe all day long impacts how regulated or anxious we feel.

Next, we focus on the exhale. Making the exhale longer than the inhale helps increase nitric oxide in the blood, which boosts the immune system and supports parasympathetic activation—that’s our rest-and-digest system. It also improves how we filter air and generally enhances the body’s ability to regulate itself.

Breathing in through the nose is key as well. Nasal breathing helps filter, warm, and moisten the air and contributes to overall respiratory efficiency. Finally, we want to encourage diaphragmatic breathing—breathing into the belly rather than the chest. On the inhale, the belly should expand. On the exhale, it should gently contract. This belly-focused breathing helps deepen relaxation and supports vagal tone, which is directly related to nervous system health.

Even getting clients to consciously practice these techniques—slow, soft, nose-based, diaphragmatic breathing with a longer exhale—for a week, whenever they remember to, can significantly reduce anxiety. Breath is foundational. It's one of the most accessible and powerful tools we have for retraining the nervous system to feel safe.

Other Somatic Affirmations of Safety

- Touch: resourcing, eyes

- The basic exercise (Rosenberg, 2017)

- Physiological sigh (Balban et al., 2023)

- Alternate nostril breathing (Ghiya, 2020)

- Mindfulness (Hoffman & Gomez, 2017)

We can also guide clients to ask themselves a simple but powerful question: What do I need in this moment to help me feel supported? This question opens up an internal dialogue that helps clients connect to their regulation needs. From there, we can offer options, like resourcing touch. This might look like holding their own face, placing hands on the chest, giving themselves a gentle hug, or experimenting with other forms of self-contact to see what feels grounding. Some people, for example, find it calming to cover their eyes with their palms. It’s all about finding what feels right for the individual.

Another powerful tool is the Basic Exercise, which is a somatic affirmation of safety through body positioning. To do it, the client interlaces their fingers behind their head, supporting their head with their hands, with elbows gently back and shoulders relaxed. From there, they hold their gaze to the left for about a minute, and then to the right for another minute. This posture communicates safety to the nervous system because it exposes the body—particularly the internal organs—in a way we wouldn't do if we were under threat. It's a bit like a relaxed beach pose. The side-to-side eye movement also signals that the eyes are not locked onto a target, which helps downregulate the nervous system. If this isn’t clear just by description, you can look up “the Basic Exercise” online—many visual examples are available.

The physiological sigh is another simple but effective technique. It involves taking an inhale, then an extra sip of air at the top, followed by a long exhale, like you’re fogging up a mirror. So it’s: inhale, extra sip, long exhale. This doubly inflates the alveoli (the small air sacs in the lungs) and helps offload excess carbon dioxide, which brings the body closer to regulation.

You can also use mindfulness of the five senses to bring someone into the present moment. It could be as simple as asking: What do I see right now? What do I hear? What do I feel? What do I smell? What do I taste? This sensory awareness can help ground someone who’s feeling overwhelmed or disconnected.

There are so many nervous system regulation techniques, just a few of them. I’ve gathered many of these practices in my book, which is available on my website.

TIPP Skill

- Temperature

- Intense exercise

- Paced breathing

- Progressive muscle relaxation

- Sour sensation?

We can also help clients work with temperature to regulate their nervous system. Engaging with strong temperature changes—like going into a sauna, stepping into a cold shower, or placing an ice pack on the forehead or the back of the neck—can help the body register a completely different sensation. This creates a somatic shift that interrupts the feedback loop of panic and anxiety. It gives the nervous system something new to focus on, offering a reset.

Intense exercise is another great option. A quick HIIT workout, running up a flight of stairs, or even doing 20 jumping jacks can help offload excess energy, just like we talked about earlier with the stress response cycle. For clients who feel a strong sense of activation, this kind of movement can give their body a chance to discharge that energy and move toward a more regulated state. Even simply pacing while focusing on breath—like using the SEND breath technique—can be effective.

Progressive muscle relaxation is another accessible tool. It involves gently squeezing and then releasing different muscle groups throughout the body. It helps bring clients back into their bodies in a calming and structured way, not in a way that hyper-focuses on the anxious sensations but promotes a sense of control and release.

There are also some newer, creative tools being explored for panic, including the use of sour sensory input. For example, popping a very sour candy—like a Warhead—into the mouth during the onset of a panic attack can provide a sharp, distinct sensory experience that redirects focus and offers immediate contrast to the anxious state. Again, it’s about creating a new, competing sensory input that helps break the cycle of panic and helps the body remember: something else is happening here, and I can stay with it.

Summary

This brings us to the end of our presentation here. I hope this is helpful to you in your practice settings.

Questions and Answers

How do we distinguish between real danger and anxious fear?

Start by assessing whether the threat is immediate. If there's no immediate threat, we likely don’t need a full-blown survival (fight-or-flight) response. An anxious reaction may still occur, but we can support clients by helping them recognize the difference between perceived and actual danger.

What if the situation involves real risk, like driving?

Driving does carry some inherent risk. However, being in a state of panic while driving increases that risk. So we must ask: Is the danger enough to justify a survival response, or does the response make the situation worse?

What does “sore but safe” mean, and can it apply beyond pain?

Originally from somatic tracking used in pain management, “sore but safe” reassures that discomfort doesn’t always signal danger. For anxiety, you might say “tense but safe” or “racing heart but safe,” helping to label sensations without escalating fear.

What is the youngest age at which these techniques can be used?

Body-based techniques like the physiological sigh can be taught to toddlers. However, more cognitive strategies, like thought challenges, should align with a child’s logical and emotional development.

Can these techniques help individuals with dementia, Down syndrome, or autism?

Yes. Focus on simple somatic and physical techniques. Following along with a breathing exercise like the physiological sigh can promote calm, even if cognitive understanding is limited.

Does research support using visuals with breathing techniques?

While research specifics weren’t discussed, visualization can enhance breathing exercises. Imagining calming scenes—like waterfalls or light cleansing the body—can support nervous system regulation.

What strategies help manage panic attacks?

There are many. Some were covered briefly in the session, but more in-depth tools can be found in the speaker’s course and workbook. Authors like Deb Dana also provide excellent resources.

How do we respond to pushback from psychotherapists when we use mental health techniques?

Occupational therapy focuses on function, supporting clients with practical strategies for the present. Psychotherapy often explores deeper processing and past events. These roles can overlap, but OT emphasizes functional application.

Is drawing a “happy place” effective?

Yes. Drawing and writing help activate calming parts of the brain and reduce amygdala activity. They are excellent tools for self-regulation.

What physical activities besides HIIT can help reduce anxiety?

Swimming, dancing, shaking the body, or even light movement can be effective. Tailor the activity to the client’s ability, from bedridden individuals to those engaging in intensive activities.

References

Please refer to the additional handout.

Citation

Dureno, Z. (2025). From overwhelm to ease: OT strategies for anxiety management. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5822. Available at www.occupationaltherapy.com