Introduction

Thank you all for joining me. I think this is such an important topic, and it is an area of interest for me. When you look at the research, and I mentioned in my previous presentation on this, occupational therapy is one of the main interventions to help people with dementia. Yet, still to this day, many occupational therapists are not comfortable or confident in treating dementia. I hope this will help you recognize the amazing skill sets that we have to help these people live a better life.

Understanding the Impact

It is important to understand the impact of dementia and see the person, not just the disease. Often, by treating someone with dementia, they have lost their roles, responsibilities, habits, and routines. I try to see the person that was there before, and I hope I can help frame this a little bit today.

- “ The responsibility to reach out to people with dementia lies with people who do not (yet) have dementia.” (Gilliard et al., 2005)

I love this quote by Gilliard. This is important for us to remember. We need to try to find the person. They are in there. All of us, especially OTs, need to help pull that person forward and look at their unique interests and what is going to help them participate more fully in life.

What is Dementia?

- Clinical syndrome with variable manifestations

- Chronic, acquired loss of 2 or more cognitive abilities (executive, visuospatial, memory, language) caused by brain disease or injury

- The decline of cognitive abilities from the prior level of function

- Impairment in day-to-day functional abilities (social, occupational, self-care)

- DSM-5 recognized that dementia could involve impairment in a single domain

(Arvanitakis, Shah, & Bennett, 2019)

I am going to go quickly through this first content as an overview. Dementia is a clinical syndrome that has a lot of different variables in its manifestation. It is considered a chronic acquired loss of two or more cognitive abilities caused by brain disease or injury. You see those cognitive domains there that we are all familiar with. There is known to be a decline of cognitive abilities from the prior level of function. This is not based on intellect or IQ. We are looking at how a person functions. There is an impairment in their day-to-day functional ability to impact their self-care, IADLs, and social/leisure participation. The DSM-5 recognizes that dementia could involve an impairment in a single cognitive domain. Previously, it was thought that it had to be two or more cognitive abilities. We now recognize that it could be in a single domain like executive function or memory.

ICD-10 Definition of Dementia

- ‘A syndrome due to disease of the brain, usually of a chronic or progressive nature, in which there is a disturbance of multiple higher cortical functions, including memory, thinking, orientation, comprehension, calculation, learning capability, language, and judgment.

- Consciousness is not impaired.

- Impairments of cognitive function are commonly accompanied, occasionally preceded, by deterioration in emotional control, social behavior, or motivation.

- The syndrome occurs in Alzheimer’s disease, cerebrovascular disease, and other conditions primarily or secondarily affecting the brain.’

This is the ICD-10 definition of dementia. Consciousness is not impaired, but it is chronic and progressive in nature. There is also a disturbance of those higher cortical functions. We also know that it is commonly accompanied by some changes in social behavior functioning, the control of emotions, and motivation. We will get into some of these behavioral disturbances a little bit more today.

The syndrome can occur with Alzheimer's disease, or different brain conditions, even cerebrovascular disease. Anything that can primarily or secondarily affect the brain.

Alzheimer's Disease

- A progressive neurological disorder results in the irreversible loss of neurons, especially in the hippocampus and cortex.

- The most common neurodegenerative condition

- Constitutes 2/3 of dementia cases overall

- Prevalence is about 1% in ages 65-69; increases with age to 40-50% in persons 95 years or older

- About 7% of early-onset cases are familial with an autosomal dominant

Alzheimer's is the most common neurodegenerative condition that involves dementia. It constitutes over two-thirds of dementia cases. This is one that you will most than likely see in your practice at some point. The age prevalence is a little bit older. It is 1% in the ages of 65 to 69, but with increases in age, it dramatically increases (40-50% in persons 95 years or older). About 7% of early-onset cases are considered to be familial and have a genetic dominant presentation.

Parkinson's Disease Dementia (PDD)

- Executive function deficits

- Memory

- Construction and praxis (Clock-Drawing Test) impairments

- Visuo-spatial deficits

- Impaired attention

- Hallucinations in 45% to 65% of cases (25% in PD)

Parkinson's disease with dementia has a little different presentation. You might see cognitive changes with Parkinson's early on. With Parkinson's Disease Dementia, the motor changes happen first. There will be slowness or bradykinesia and maybe tremor, rigidity, or things like that. Later on, dementia happens. They may have mild cognitive changes initially, but later dementia has a significant impact on function. With PDD, there are many changes in executive function with multitasking, initiating tasks, and step sequencing. They do have some changes to memory, but it is often more working memory than long-term memory. Their clock-drawing tests and construction and praxis tests can really show some deficits as they have visuo-spatial problems and vision problems. They can also have impaired attention, and that can be both visual and auditory. You may also see hallucinations. This occurs in 45 to 65% of cases with PDD and only 25% of those with Parkinson's disease.

Dementia with Lewy Bodies (DLB)

Sometimes people are diagnosed with PDD, and then they end up switching the diagnosis to Dementia with Lewy Bodies (DLB). This can be hard to tease out. Basically, what determines the difference is if the motor or the cognitive symptoms start first. Much of the presentation is similar.

- Core clinical features (first 3 tend to occur early)

- REM sleep behavior disorder, which may precede cognitive decline

- “Fluctuating” cognition with pronounced variations in attention and alertness

- Recurrent visual hallucinations- typically well-formed and detailed

- One or more spontaneous cardinal features of parkinsonism:

- Bradykinesia (defined as slowness of movement and decrement in amplitude or speed)

- Rest tremor

- Rigidity

There are some core clinical features. The first three listed tend to occur pretty early. A REM behavioral sleep disorder happens with PDD as well. This fluctuation in cognition can be profound and can be really tricky for care partners and therapists. They may come in one day, and they are functioning at one level, and then they come in another day, and they are very different. You may see a lot of variants in their presentation with DLB. Often, they will have visual hallucinations that are very well-formed and detailed. I had a lady at one point who saw little people. She could describe them to you very clearly about what they looked like. Some people see children. They will also have one or more of these spontaneous features of parkinsonism. If you have attended any of my other talks, I go into these characteristics like slow movements (bradykinesia), resting tremor, and rigidity.

- Essential for a clinical diagnosis of probable and possible DLB:

- Dementia

- Deficits in attention, executive function, and visuo-spatial can occur early and be very prominent

- Memory impairment may not occur early in the disease but often presents with progression

- Cognitive symptoms prior to motor symptoms

You are going to see these motor features with DLB as well. They start later or in tandem with the cognitive changes. The deficits in executive and visuo-spatial function occur pretty early. Memory impairment may not occur early in the disease, but you will see that start to happen more as it progresses. As I said, cognitive symptoms happen before motor symptoms. Both PDD and DLB have a presence of Lewy bodies in the brain, but the symptoms present are how they diagnose it. There is even some argument amongst movement disorder specialists that it is the same thing. I will let them fight that out, but for now, we will look at what they are telling us.

Frontotemporal Dementia

- Three Clinical Variants:

- Behavioral- most common

- Language

- Motor

- Diagnosis: (Differential) history of the progression of behavioral changes, family history, behavior during interviews, neuro-psych testing, labs, and neuroimaging

- The most common form of dementia under the age of 60

- 40% of those diagnosed with FTD have a family history with at least one other relative with a neurodegenerative disease; 10% have a gene mutation

This is the most common form of dementia under the age of 60. It can impact people's lives when they are still working or raising children. There are three different variants that you typically see. The behavioral type is the most common. They can have socially inappropriate behaviors where they become sexually suggestive toward people or withdraw with more apathy. There are many other presentations. Language is often affected, and you can see primary progressive aphasia or many difficulties with language. There is a motor variant that sometimes gets confused with parkinsonism or can even ALS or Lou Gehrig's disease. At one point, when I started treating ALS many years ago, there was no cognitive presentation. However, sometimes people with ALS have FTD as well. It is important to note that to diagnose, they have to look at the family history, behavior during interviews, neuro-psych testing, labs, and imaging as it is pretty hard to diagnose. And, 40% of those diagnosed have a family history with at least one other relative with neurodegenerative disease, not necessarily FTD. Ten percent have a gene mutation. This is a somber one as the individuals are so young. This genetic link was just discovered in recent years.

Other Dementia Presentations

- Vascular Dementia

- Huntington’s Disease

- Mixed Dementia

- Normal Pressure Hydrocephaly

- Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease

Another presentation is vascular dementia after a stroke or a vascular event. Huntington's Disease involves decreased behavior and insight. You also may see mixed dementias. Sometimes people have different presentations or conditions, like normal pressure hydrocephaly and even Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease.

Impact on Participation

Many different conditions can involve dementia. It is imperative to understand the behaviors behind dementia; I do not always have to know the diagnosis. Someone recently in one of my courses said, "I don't know if this person has Parkinson's or if they have Dementia with Lewy Bodies." My response was, "It doesn't really matter." At the end of the day, what matters is what is impacting their participation? What are their barriers, and how can we help them overcome those? We can leave the diagnosis to the experts.

- Increased time for task completion

- Increased dependency for self-care and home management

- Difficulty with new learning

- Decreased social participation

- Impaired communication

There are many impacts on participation. The individual may need increased time for task completion depending on the severity of the disease. They may need help to initiate or complete tasks. They often have difficulty with new learning. This is where we look at encoding versus retrieval. They may have trouble communicating and saying what they need/want. They may not use appropriate facial expressions or be able to understand or process information received. We will talk more about this later. There can also be a delayed processing speed. As clinicians, we have to allow space and time for individuals to process after giving them information or instructions. This can be hard, but it is essential. You may see increased dependency for self-care and home management. Often, they start to withdraw socially, which can be due to difficulties with their behavior and communication. They may not be able to control or regulate their behavior. And, if they have a hard time processing a conversation, they may not know how to respond and end up sitting there. That is not a lot of incentive to want to engage.

Caregiver Strain

- Physical and mental health problems

- Difficulties maintaining employment

- Financial difficulties

- Barriers to leisure engagement

- Difficulty with family interactions

- Reduced quality of life

(Bennett, Laver, Voigt-Radloff, Letts, Clemson, Graff, Wiseman & Gitlin, 2019)

Dementia also causes a great amount of caregiver strain. There is more and more literature coming out on this all the time. Currently, I run a care partner group. We work to empower these attendees. Dementia is the number one issue to understand and manage. It causes a lot of physical and mental health problems for the care partner. They often have trouble maintaining employment, especially if you think about a diagnosis of FTD when someone's loved one is younger. The care partner is worried about leaving them at home alone because of their insight and judgment. How do they maintain their own employment? This can lead to financial difficulties. We live in a society where often both people work. This can cause a lot of difficulties.

There can be a lot of barriers to leisure engagement for care partners. They need to take care of their loved ones and often do not have help for care. They may feel guilty taking the time for themselves.

They can start to have some difficulty with family interactions. I find this mostly when the family does not get it. I end up doing a lot of education with families and adult children, sometimes with friends and neighbors. It can be really emotional and hard for the care partner to discuss that with people.

Overall, if you add all of these things up, it is easy to see where this could impact the quality of life for the care partner and the person with dementia. What do we do about this? How do we approach this? I could sit here and go through research articles, but I wanted to give you a framework to provide care for someone with dementia. I also wanted to give you insight into how I create a treatment plan and how I put this all together.

Finding the Person in Person-Centered Care-Models

How do we find this person in there that is passive and not talking or interacting? We have never met this person before. We have to reframe our concept of dementia to connect with that person.

Social Model of Dementia Care

- “The social model of care seeks to understand the emotions and behaviors of the person with dementia by placing him or her within the context of his or her social circumstances and biography.”

- By learning about each person with dementia as an individual, with his or her own history and background, care and support can be designed to be more appropriate to the needs of the individual

- Without this background knowledge and understanding, behaviors may lead to misunderstanding and incorrect labeling of the individual.

- Other intrinsic factors, such as the cultural or ethnic identity of the person with dementia, must inform how needs are assessed and care is delivered.

- The social model of care asserts that dementia is more than, but inclusive of, the clinical damage to the brain.

(Marshall, 2004; NICE Guideline 42, 2007)

The social model of dementia care is what underlines my approach. In fact, it underlined my approach before I even understood what it was. When I found it, I thought this is what I am already doing. Basically, you are trying to understand the emotions and the behaviors of that person by placing them within their context, either their social circumstances and their biography. Who is this person? How are they feeling? How do they perceive themselves now? How is their environment impacting that? When we learn about each person as an individual and hear their history/background, we can more aptly program their care and provide the support they need. Without that knowledge, their behaviors and how they are reacting to things are misunderstood by caregivers. They are often labeled as having a behavioral disturbance or inappropriate behavior. Instead, their needs are not being met or understood. We have to consider some other factors too, like their culture and ethnic identity. This is also going to inform us of how their needs can be met and their care delivered. I love this last statement at the bottom of this slide. The social model of care asserts that dementia is more than, but inclusive of, the clinical damage to the brain. We are not just looking at what functions and what does not. We have to get in there and see the person who is still there.

- From the social model perspective, people with dementia may have an impairment (perhaps of cognitive function), but their disability results from the way they are treated by, or excluded from, society.

- For people with dementia, this model carries important implications, for example:

- The condition is not the ‘fault’ of the individual

- The focus is on the skills and abilities of the person rather than losses

- The individual can be fully understood (his or her history, likes/dislikes, and so on)

- Create an enabling or supportive environment

- Appropriate communication with the individual with dementia is key

- Opportunities should be taken for rehabilitation or re-enablement

(Marshall, 2004; NICE Guideline 42, 2007)

From this perspective, people may have an impairment, obviously decreased cognitive function with some physical impairment, but their disability results from the way they are treated by or excluded from society. This is so true, and I cannot stress this enough. As a society, we are not very inclusive of people with disabilities, period. I think this is especially true with cognitive disabilities as you cannot see them. You can see if someone cannot get out of a chair or has trouble walking, but you cannot see that it takes someone longer to process, so it is very misunderstood.

This model carries some significant implications that I live by these and try to teach care partners. First, it is not the fault of the individual, but it is their condition. They have not done something wrong. We have to focus on their skills and abilities and what they can do rather than what they have lost.

The individual can be fully understood. You can get their history, their likes, and their dislikes. I am not going to say it is easy, but you can do it. We want to create an environment that enables the person to do what is meaningful and supports them. Appropriate communication is key. We will get to that more at the end. Then, we want to take every opportunity to rehabilitate or re-enable these people to participate more fully in life.

Need-driven Dementia Behavior Model (NDB)

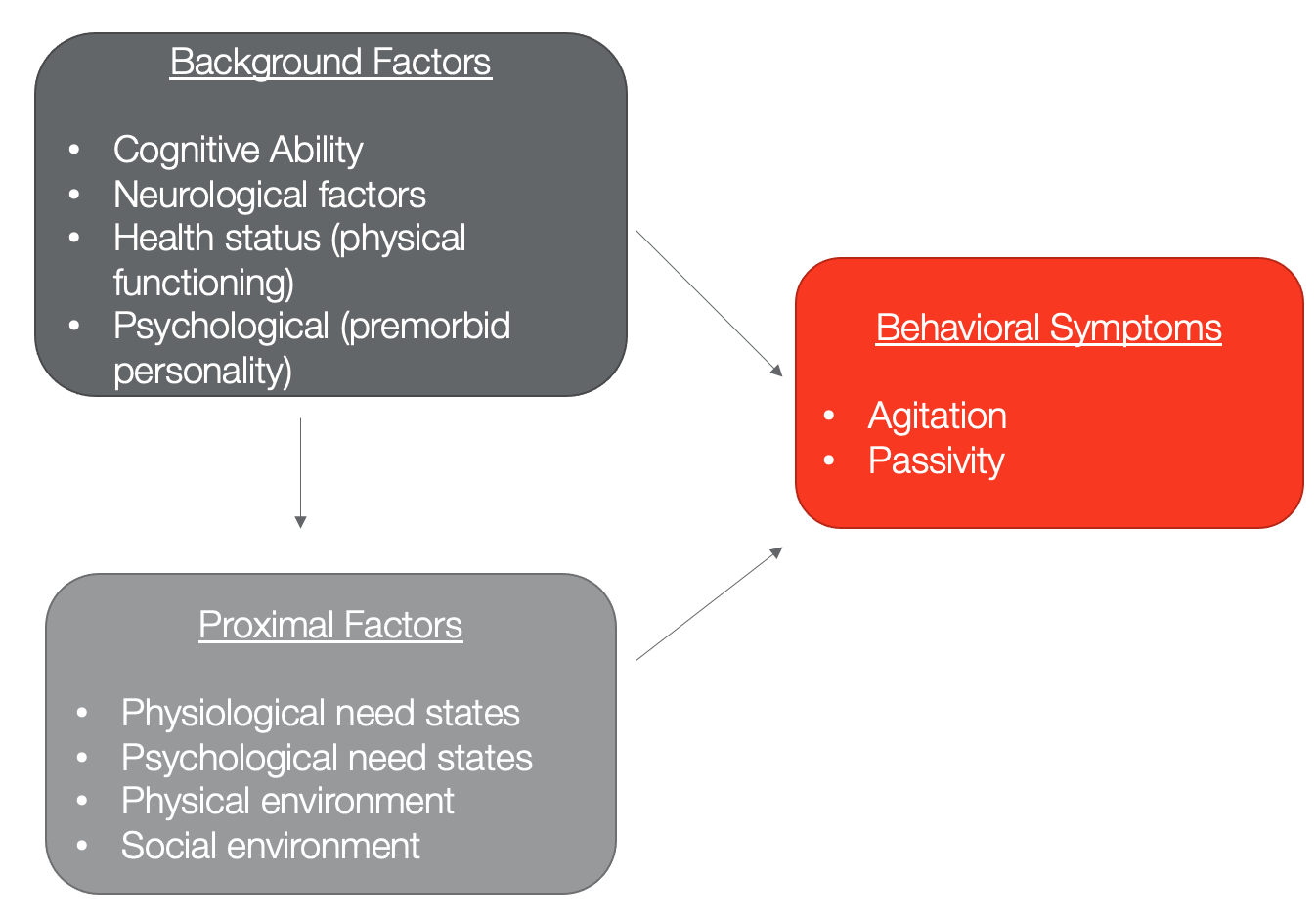

Figure 1 shows the Need-driven Dementia Behavior Model or the NDB. I am going to give an overview.

Figure 1. NDB Model. (Kolanowski, Litaker, & Buettner, 2005)

I would encourage you to look at this article. It is exciting because they went into things about the person's personality, the ways they live, and the environment.

They tailored this tool to look at these background factors like cognitive ability, neurological factors, and health status. I love this pre-morbid personality factor. The first time I heard that was when I was at the Mayo Clinic. We talked about that because their pre-morbid personality drives people's behavior and responses to treatment. We also have to consider that these background factors set up proximal factors. They feed into the physical environment, the social environment, and the physiological needs and states. All of those then feed into these behavioral symptoms. By agitation, we are talking about verbal, vocal, or motor responses. This can be aggressive or abusive behavior that you sometimes see with dementia. There is also passivity where people are withdrawn and not engaged.

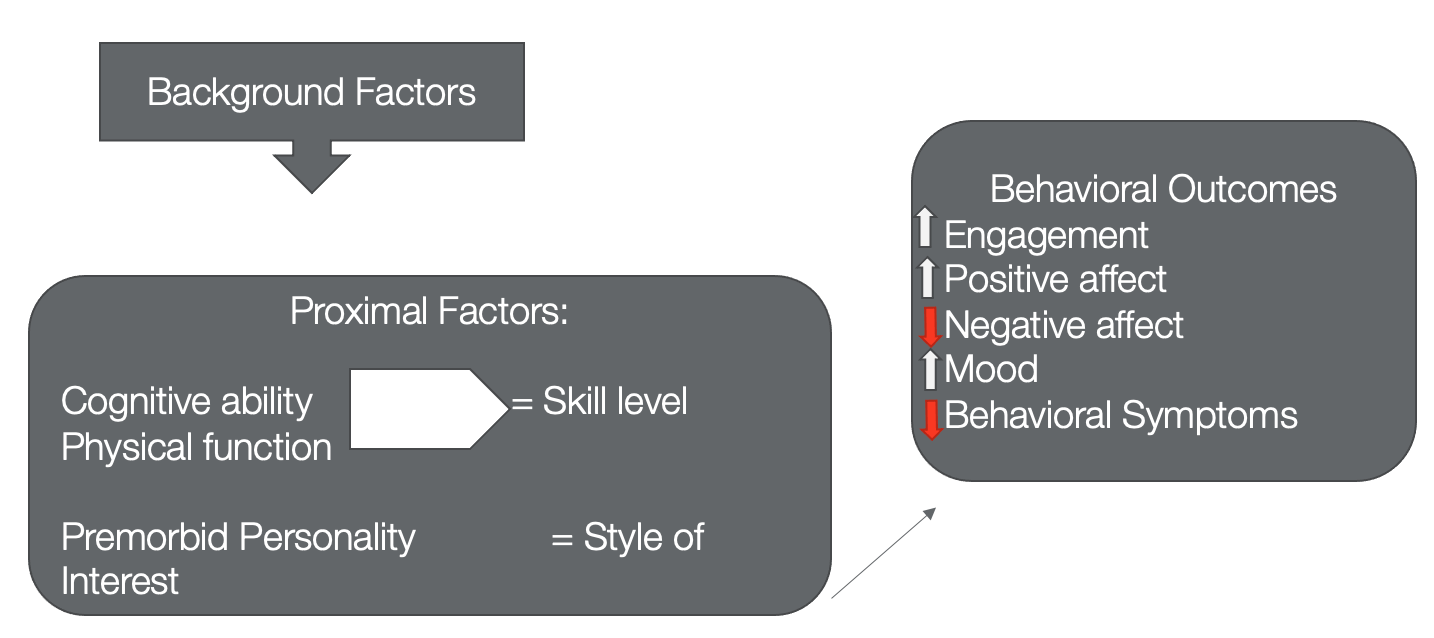

This model is really trying to change the view of behaviors from disruptive to an indication that somehow needs are not being met. We have to put on our detective hat and kind of figure it out. We are talking about the background factors or those things that are slowly changing and are more stable. We are also looking at proximal factors that we have more control over. We can look at their social and physical environments because, ultimately, we are trying to meet their needs to reduce the behavioral issues. When they looked at all these factors, they came up with a Causal Model that underlined the NDB, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Causal model.

With this, they tried to determine if someone was more extroverted or more of a homebody as an example. They had all these different categories they put people into. They found that it was imperative to address cognitive abilities and physical function and matching that to the person's skill level while also considering their premorbid personality and style of interest. Would they want to do things more in a group or more on their own? These were the categories they framed. They hypothesized that they would have improved outcomes with increased engagement, increased positive affect, decreased negative affect, improve mood, and decreased behavioral symptoms. They found that when you create a balance of someone's abilities, skill level, and interest, you get the most engagement and participation. A big one was the balance of not over arousing or under arousing. It is taking into consideration a balance to their day to have some stimulation and then some recovery time. I always tell my clients and care partners that you need your day to have peaks and valleys. The peaks are when you are doing something of interest. You are aroused and engaged. The valleys are when you are at rest. This takes a little time to tease this out for someone with dementia, but it can be done.

How Can OT Help People With Dementia?

- Health Promotion

- By focusing on maintaining the strengths of clients and promoting the wellness of care providers, OTs can enrich lives by promoting maximal performance in preferred activities (AOTA).

- Remediation

- The remediation of cognitive skills is NOT expected. OTs can incorporate routine exercise into interventions to improve the performance of ADLs and functional mobility and help restore range of motion, strength, and endurance (Forbes, Forbes, Blake, Theissen, & Forbes, 2015).

- Maintenance

- Provide supports for habits and routines that are working well for the person with dementia to prolong independence.

- Modification

- Ensure safe and supportive environments through adaptation and compensation, including verbal cueing, personal assistance, and/or social supports.

According to AOTA, the number one way to help people with dementia is via health promotion. We want to focus on maintaining their strengths and promoting wellness to enrich their lives. For remediation, we are not trying to remediate cognitive skills, improve executive function, improve memory, or make their MOCA score go up. Instead, we can incorporate exercise and interventions to improve their performance, participation, functional mobility, safety, range of motion, strength, and endurance. We can remediate their ability to participate, not their cognitive function. As far as maintenance, we want to provide supports for their habits and routines to optimize these as long as possible to increase their independence. Modification is looking at the environment to make sure that they are safe and supported. This is looking at cueing strategies and how personal assistance is going. I do a lot of training of paid caregivers and care partners in this area. I also set up social supports and find groups for my people because I really want them to feel like they have a supportive environment, not just in their home but also in their community.

Evidence- Dementia at Home

Systematic Review: Occupational therapy for People with Dementia and Their Family Carers Provided at Home (Bennett et al., 2019)

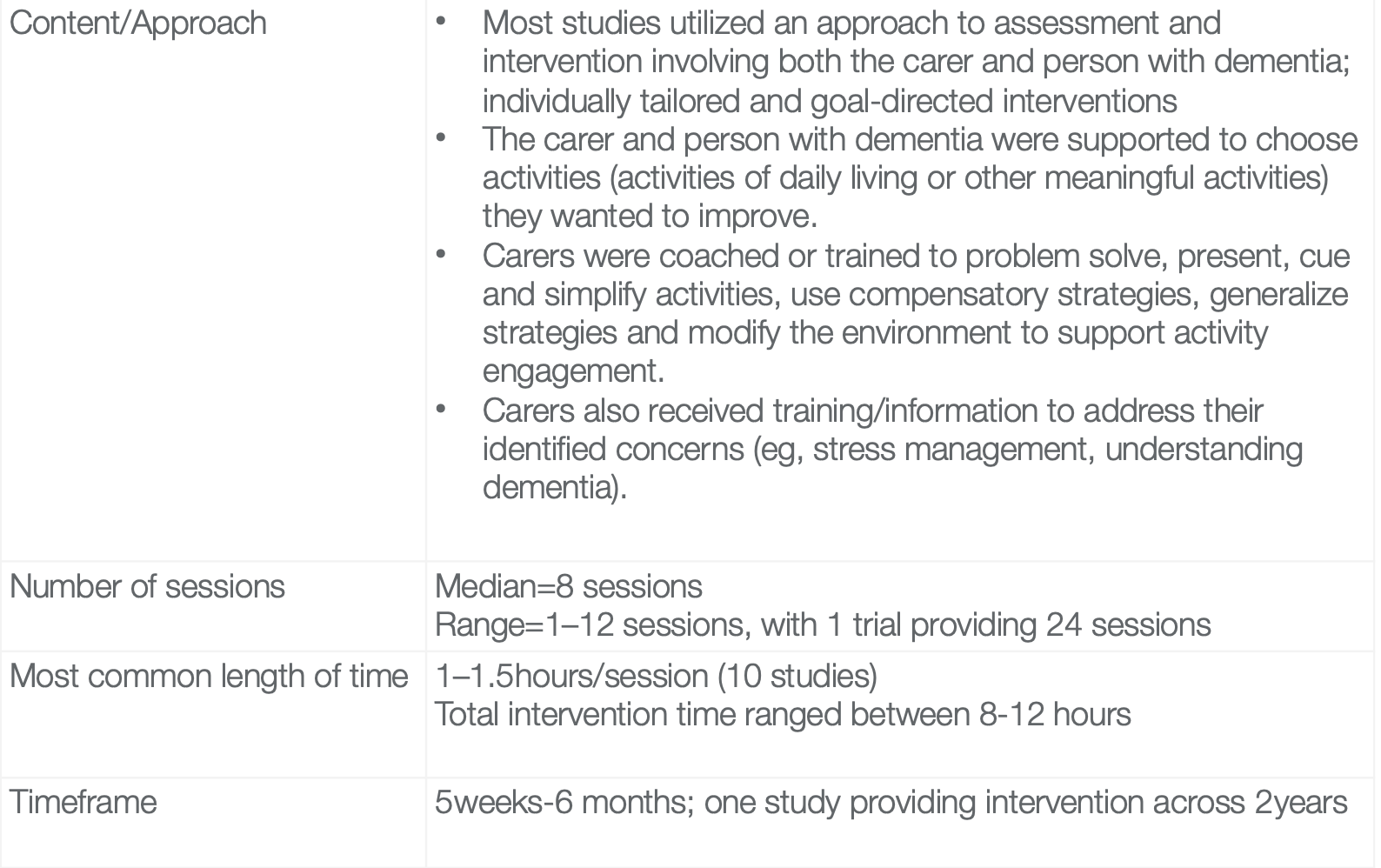

This is a great systematic review done in 2019 and looked at these different approaches in Figure 3.

Figure 3. A systematic review on OT for people with dementia and family carers. (Bennett et al., 2019).

Most studies utilized an approach to assessment intervention that involved both the carer and the person with dementia. This is not meant as a criticism of people caring for people with dementia. Sometimes, they want to drop them so they can have some time to themselves. However, if we are going to get to know that person and they have communication problems, we are going to need some help from that care partner to give us some insight. We need this information to individually tailor and provide interventions that are goal-directed to that person. The other successful studies were when the care partner and the person with dementia chose either activities of daily living or other meaningful recreation or leisure activities that they wanted to improve. The caregivers were coached to problem solve, present cues, simplify activities, use compensatory strategies, and modify the environment. We have to train those carers, either paid or spouse/family member. We also have to give them information on how to address their own concerns. Often, this is information on stress management or understanding dementia. I find I have to educate the care providers that the individual with dementia is not naughty. They just lack judgment and insight.

The average number of sessions was eight, but there was a range between one and 12. One trial even did 24 sessions. The most common intervention time was around an hour to an hour and a half. I bring this up because I know many times people are trying to do half-hour or 45-minute sessions. This will not be enough time to work with these folks and really get an idea of what you are doing. The timeframe range for these studies was around five weeks to six months. One study even provided intervention across a couple of years. My point is that your plan of care will need to be longer to make the impact that you want.

- Occupational therapy was more effective than usual care or attention control for improving overall activities of daily living for people with dementia.

- There were fewer behavioral or psychological symptoms in people with dementia in the OT group, compared with usual care or attention control.

- OT resulted in a better quality of life for people with dementia than for people in the control groups.

- The effect on the family carers was more mixed. There was no difference between the groups for carer depression immediately after the intervention or for carer burden. However, carers reported fewer hours doing things for the person with dementia.

- Carers in the OT groups also reported less distress or upset with the behaviors or psychological symptoms of the person with dementia.

- In addition, there was some improvement to carers’ quality of life following the OT intervention.

(Bennett et al., 2019)

In summary, they found that OT was more effective than usual care or attention for impacting ADLs for people with dementia. There were fewer behavioral and psychological symptoms with the people who worked with the OT group than those control groups. Occupational therapy also resulted in a better quality of life for people with dementia. The effect on the family carers was a little bit more mixed. They found no difference for care depression or care burden, but the caregivers reported that they spent fewer hours doing things for the person with dementia. The OT intervention freed up their time. The carers also reported less distress or upset with behaviors or psychological symptoms. And, there was some improvement in caregiver quality of life in the OT intervention group.

If you are out there, not feeling confident, and think that OT cannot help these people. Here is your evidence. You can do a lot. It is not easy, and it requires a lot of digging. It also might require some communication with your team and management about your schedule so that you can meet these needs appropriately.

Effects of Nonpharmacological Interventions on Functioning of People Living with Dementia at Home: A Systematic Review of Randomised Controlled Trials (Scott et al., 2019)

- “Person-centered approaches, which optimize the environment and activities, support family carers, and are needs and goal-based, enable self-management where possible, and are underpinned by a responsive case management service model; are the models that appear to be most likely to be effective.”

I like this quote because it sums it up in a nutshell. This is occupational therapy and what we need to do. If you can involve social workers or case managers and provide a team approach with PT/SP, better yet. It takes a village.

Evidence: Cognitive Rehabilitation and Dementia

- Cognitive restoration/retraining

- Repetitive practice of tasks that require targeted cognitive process with the goal of strengthening that cognitive process and improving functional performance

- Not shown to translate to function in people with dementia

- Strategy based-approach

- Provides approaches for accomplishing desired tasks and activities despite the presence of cognitive deficits

- Trains use of metacognitive, problem-solving, or compensatory strategies for use in everyday life to cope with cognitive challenges

I want to touch on this quickly. When talking about cognitive rehabilitation and dementia, you do not play memory games with them (unless they think memory games are fun) or improve their cognition on their MoCA or Mini-Mental. We are talking about a strategy-based approach looking at problem solving or compensatory strategies that we can employ for an activity or their environment to make them more safe and efficient.

NICE Guideline

- NICE defines cognitive rehabilitation for dementia as “identifying functional goals that are relevant to the person living with dementia and working with them and their family members or carers to achieve these.”

(NICE Guideline 42, 2007)

This is a nice guideline from the UK that looks at function. Every time I read one of these statements, I think this is what OT does.

Evidence‐based Occupational Therapy for People with Dementia and Their Families: What Clinical Practice Guidelines Tell Us and Implications For Practice (Laver et al., 2017)

- “Occupational Therapists should avoid spending time on activities that have not demonstrated improved outcomes for the person with dementia, such as cognitive retraining” -The Role of the Occupational Therapist in the Management of Neuropsychiatric Symptoms(NPS) of Dementia in Clinical Settings (Fraker, Kales, Blazek, Kavanagh & Gitlin, 2014)

- The “DICE” (Describe, Investigate, Create, and Evaluate) approach is a patient- and caregiver- centered intervention approach

- DICE offers a clinical reasoning approach through which providers can more efficiently and effectively choose optimal treatment plans.

This is a way to approach dementia care and hopefully reduce neuropsychiatric symptoms. It stands for: Describe, Investigate, Create, and Evaluate. We are looking at a patient and caregiver-centered intervention. It is a clinical reasoning approach so that we can more efficiently and effectively create treatment plans. For my students, I instruct them to create an outline using this acronym.

- DICE: Describe

- Occupational performance analysis may include reviewing the person’s abilities, environmental setting, caregiver communications and interactions, and demands of an activity.

- The activity demands include required actions, performance skills, body functions, body structures, and environmental context.

- In addition to in-person evaluation, caregivers can be encouraged to record issues and the context in which they occur in diaries for later review by the OT.

For the occupational performance analysis, we are looking at their abilities, environmental setting, how they communicate with their caregiver, how they interact, and demands of activities. This is the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework 101, looking at body functions, body structures, and performance skills. In addition to the in-person evaluation, it is important to encourage caregivers to record issues and the context in which they occur in a diary. I even have people sometimes take a video so I can see what happens in real-time. Caregiver input can be helpful.

- DICE: Investigate

- Occupational performance analysis may include reviewing the person’s abilities, environmental setting, caregiver communications and interactions, and demands of an activity.

- The activity demands include required actions, performance skills, body functions, body structures, and environmental context.

- In addition to in-person evaluation, caregivers can be encouraged to record issues and the context in which they occur in diaries for later review by the OT.DICE: Create

When we investigate, we are playing detective and looking at standardized assessments. I did a previous webinar about a year ago that went much deeper into assessments. Today, I am going to focus on intervention. You could look back to that if you need some ideas. We want to interview the caregiver to understand the individuals' past roles. What were their occupations and hobbies? Did they participate in religious activities or organizations? What was their role in the family? What was meaningful to them? How did they spend their time? We need to know what was motivating to them, both the past and the present. What was their daily routine? Look at times or days where they were more active or alert, or those times they demonstrated behavioral issues. We also want to look at their range of motion, strength, mobility, and fall risk. Are they seeing PT? For example, folks with Parkinson's Disease Dementia (PDD) can have visual illusions. They may be confused in a cluttered environment or think a blanket over a chair is a monster. You have to look at the environment. How is the lighting? What is the setup?

- Educate the caregiver about dementia and behavioral symptoms

- Build skills in effective communication and modify the environment to reduce or minimize external contributors to the behavior.

- Help the caregiver understand the patient’s functional level, including limitations and abilities, how to improve communication, and how to introduce and use activities to prevent and minimize NPS.

- Recommend ways to simplify the environment to support the best functioning of the person with dementia and minimize confusion in using objects or wayfinding in the home.

Then, we have to educate the caregiver about dementia and symptoms. You cannot assume they understand it because most people do not, even very educated people. I had to explain to an attorney who was the manager for a gentleman's estate. He said, "Well, he can remember all his friends and family. He doesn't have any problems with that." I informed him that while his long-term memory was not impaired, he did not have good judgment or insight as he pulled a live mouse off a glue trap. Many times explaining this can take a lot of effort, but it is worth it.

Try to build skills and effective communication so you can reduce those external contributors to behavior. As I said, things in the environment can act as triggers and help the caregiver to understand their functional level. Help them understand their limitations and abilities, why something might be unsafe, and how to improve communication. We will talk about that a little later as we get into the Tailored Activities Program (TAP). We can recommend ways to simplify the environment to support their best function. We can help minimize confusion, guide them in the use of objects, and assist with wayfinding by appropriately setting up the environment.

- DICE: Evaluation

- Consult with the caregiver to determine the outcome: what strategies were implemented, what worked, what did not, and unexpected results, both positive and negative.

- Help differentiate and evaluate reasons why strategies are not working:

- Did the caregiver implement the strategy incorrectly?

- Was there a change in the patient’s status that made implementation difficult?

- Was it not the right strategy for this particular caregiver-patient relationship?

- Consult and coordinate with other team members.

- Report symptoms of worsening cognition to the physician

- Increased home services and resources may need to be explored.

Lastly, we want to know what strategies were implemented. What worked and what did not? Once you have put this plan into place with the care partner, there will be unexpected results, probably both positive and negative. Did the caregiver implement the strategy you gave them correctly? Has there been a change to the status that made it difficult, like a urinary tract infection or other behavioral problems? Then, we need to consult and coordinate with other team members like PT, speech, nursing, social work, et cetera. We also need to report symptoms if there is any worsening cognition or functioning to refer them for increased home services and resources if needed.

Goal‐orientated Cognitive Rehabilitation for Dementia Associated with Parkinson's Disease―A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial

(Hindle et al., 2018)

- Goal-orientated cognitive rehabilitation uses goal setting and evidence‐based strategies to improve function in everyday activities in people with dementia.

- Showed that cognitive rehabilitation was superior to treatment‐as‐usual and relaxation therapy for primary outcomes in dementia associated with Parkinson's.

- Cognitive Rehabilitation is feasible and potentially effective for dementias associated with Parkinson's but requires further study.

This is specific to Parkinson's Disease with Dementia. They created a goal-oriented cognitive rehab program and let people with dementia do what they wanted to do. Was it put on their pants? Was it put on their shirt? Was it get their own bowl of cereal? They set those goals and helped the person to meet them. They showed that when they compared this intervention to relaxation therapy, the people with dementia had better outcomes. Additionally, the care partners had better outcomes with quality of life, depression, and mood changes. This suggests that cognitive rehab is feasible and potentially effective for dementia associated with Parkinson's using a goal-oriented framework.

This is really similar to what the NICE guidelines are recommending as well.

Dementia Care Plans (Nice Guidelines, 2018)

- “Care plans should always include:

- consistent and stable staffing

- retaining a familiar environment

- minimizing relocations

- flexibility to accommodate fluctuating abilities

- assessment and care-planning advice regarding ADLs, and ADL skill training from an occupational therapist

- assessment and care-planning advice about independent toileting skills; if incontinence occurs, all possible causes should be assessed, and relevant treatments tried before concluding that it is permanent

- environmental modifications to aid independent functioning, including assistive technology, with advice from an occupational therapist and/or clinical psychologist

- physical exercise, with assessment and advice from a physiotherapist when needed

- support for people to go at their own pace and participate in activities they enjoy”

These are some things that your care plan you should always consider. First, there should be consistent and stable staffing. You do not want a whole lot of people that are unfamiliar with working with this population. You want the staff and the environment to be as familiar as possible.

We should also minimize relocations from their home or a different unit. We need to keep this to a minimum.

We need to be flexible to accommodate different fluctuations in these individual's performance. We need to look at their highs and lows to figure out how to create care planning and skilled training for their ADLs. We also need to look at their independent toileting skills. If they are incontinent, we have to look at what the causes are. Do they need a toileting schedule before you just assume they are incontinent? Are there some supports that you can put into place to help them to go to the toilet?

Environmental modifications can also be made to aid independent functioning. Assistive technology can be helpful, but you need to make sure that it will not be too hard for them to learn. I have seen people give some complicated communication boards to people with dementia when I could not even figure out how to use them.

Physical exercise is crucial. A physical therapist may get that going and support them at their own pace.

Promoting & Maintaining Independence

- “Health and social care staff should aim to promote and maintain the independence, including mobility, of people with dementia.”

- “Care plans should address activities of daily living (ADLs) that maximize independent activity, enhance function, adapt and develop skills, and minimize the need for support.”

- When writing care plans, the varying needs of people with different types of dementia should be addressed.

Ultimately, these guidelines are to promote and maintain independence. We want to try to keep their mobility going and keep them as independent as possible. We want to address their ADLs, enhance their function, and adapt their skills. When you are writing a care plan, the varying needs of people with different types of dementia has to be addressed. For example, not all people with dementia will want to go to your knitting group at the skilled nursing facility. You have to think about the different variances and presentations.

Treatment Strategies

Therapeutic Use of Self

How can we use our therapeutic use of self within treatment strategies? I find this to be one of the greatest tools I have. The more that I can get in there and use my skills to keep someone's attention and keep them engaged, the better.

Focus on a Strength-based Approach

- Identify strengths and abilities rather than deficits and limitations

- Use familiar and functional activities that rely on the long term and procedural as therapeutic activities and exercises rather than new and unfamiliar tasks and equipment (Ries, 2018)

Again, it is important to use a strength-based approach. This is looking at familiar and functional activities rather than trying to give them unfamiliar tasks and equipment. We want to use what is familiar and comfortable to the person.

Utilize "Errorless" Learning

- Practice performing tasks in the same way, with consistent cues in the same environment (when possible) to reduce the possibility of mistakes

- Focus on learning by DOING rather than thinking about HOW to do them

We want to use errorless learning during ADL tasks. They are learning by doing rather than thinking about how to do something. I always tell my students to use a little less conversation and a little more action. It becomes a distraction to them when they are trying to process verbal communication.

Speak Clearly and Slowly

- Processing time is slower and will be even slower in those with a hearing impairment

Speak clearly and slowly as their processing time is much slower. It will be even slower if the person also has a hearing impairment which is often the case.

Nonpharmacologic Approaches

- Cognitively stimulating activities

- Social engagement

- Physical exercise- both aerobic & resistance

- A healthy diet (Mediterranean diet)

- Adequate sleep

- Safety (home appliances, driving)

- Medical & advanced care directives (LSW)

- Long-term health care planning

- Financial planning

- Effective communication (visual aids)

- Participation in meaningful activities

These are some different nonpharmacologic approaches like cognitive stimulation, social engagement, exercise, and some evidence for the Mediterranean diet. However, good luck trying to get somebody to change their diet at this age. I think it is important not to fight battles that you cannot win. Sleep is so important, as is safety with home appliances and driving. You also need to look at advanced directives and long-term planning, including financial. Encourage them to meet with their attorney, social worker, or whoever will help with that. Remember, they may need visual aids for communication. Lastly, participation in meaningful activities is a key strategy.

Communication/Cueing Strategies

- Present one step or idea at a time

- Speak calmly in a normal tone of voice

- Speak slowly and simply

- If you need to repeat something, use the same words

- Stand in front of the person and maintain eye contact (gaze will lower with progression)

- Gently touch and arm or shoulder to gain attention

- Approach the individual from the front to avoid startling

- Utilize color; neon green is easiest to see, use high contrast for visibility

One of the hardest things to do as a therapist is changing how we communicate. If you can teach this to care partners as well, it can go a long way. Present one step or idea at a time. Think of it this way.

If you were to say, "Scoot forward and stand up from the chair." Then, you wait. Let's say they have a 20 to 30-second processing delay. If 10 seconds into it, I say, "Okay, Mr. Jones. I need you to scoot forward and lean forward big and stand up from the chair." Now, they have two commands and have not processed the first one. This is like having too many windows open on the computer. And, if you repeat something, use the same words, like "Scoot forward and stand up from the chair." Do add a lot more words to it. We tend to do that, and it is tough to break.

Always approach the individual from the front to avoid startling them. Speak calmly and in a normal tone of voice. We had one clinician at our clinic that had to work on this. She had a loud, cheerleader-type of voice that worked for people who did not have dementia. Going along with this, you also have to think about the tone and pace of your voice.

Make eye contact when you are standing in front of them. Often their gaze is going to be lower, so you might have to lower yourself. I always had a stool that I would sit on to get down to their level to speak slowly and simply. I do not mean to insinuate that they are not intelligent, but keeping your words concise does not mean you have to use eighth-grade level words. Sometimes a gentle touch on the arm or the shoulder can get their attention.

Color can really help. Neon green seems to be easiest for them to see as it gives a high contrast.

Tailored Activities Program

- Up to eight home sessions over 3 months

- Evaluate the person with dementia, caregivers, and living environment

- Develop activity prescriptions tailored to the individual’s capacities

- Caregivers learn to manage situational stressors, optimize function, and manage behavioral and psychological symptoms

- Provides education for caregivers on realistic expectations of the person with dementia; caregivers tend to overestimate abilities and have a poor understanding of the impact of dementia on behaviors

(Gitlin et al., 2009, 2016; Marx, Scott, Piersol & Gitlin, 2019)

Dig into the literature on the Tailored Activities Program (TAP) as there is a lot of it. Laura Gitlin is my hero. For this, they did up to eight sessions at home over three months. They evaluated the person, the caregivers, the environment and developed activity prescriptions.

Caregivers learn to manage their own stressors as part of this program. They also learn to support, optimize the function, and manage the behavioral symptoms of the individual in their care. It gives them realistic expectations about the person with dementia. Caregivers tend to overestimate abilities, or they have a poor understanding. For example, I had a gentleman who liked to cook. The minute he was diagnosed with dementia, his wife determined he could not cook anymore as it was unsafe. I asked her, "Do you think it's unsafe for him to put a salad in a bowl?" I helped her to think of ways that he could still participate in cooking without getting things in and out of the oven or other unsafe tasks. On the other hand, they may overestimate and think they can do things that they cannot or should not do. You really need to educate caregivers on the expectations, the risks, and how realistic certain activities are.

- TAP Phase 1: Assessment

- Completed during sessions 1-2

- Standardized assessments used to evaluate the person with dementia, caregivers, and environment

- The therapist collaborates with caregivers and person with dementia (when appropriate) to identify three activities of interest

- Activities are tailored to the capabilities and context of the individual with dementia

- Caregivers are educated about the disease process and learn simple stress reduction techniques

In the first phase, during the first two sessions, you will use standardized assessments and evaluations. You are collaborating with the care partner to identify three activities of interest. Those activities are then going to be tailored to the capabilities and context of the individual with dementia. Caregivers are educated about the disease process and are going to learn simple stress reduction.

- TAP Phase 2: Implementation

- Sessions 3-6

- OT reviews assessment results with caregiver

- Provides three activity prescriptions (typed document) which describe the activity, goal, person’s abilities, and implementation steps

- The therapist demonstrates how to set up and implement activities

- Caregiver practices strategies (e.g., help with initiation)

- OT uses skilled observation to modify the prescriptions as necessary

- Caregiver practices with the person with dementia between sessions

During sessions three through six, you review the assessment results with the caregiver and with the person with dementia as appropriate. You will provide those three activity prescriptions. This can be in a document that describes the activity, what the goal is, their abilities, and steps to implement. Then, you demonstrate how to set that up and implement it. The caregiver is then going to practice the strategies. You use your observation skills to modify the prescription as necessary. The caregiver will practice with the person between sessions and report back to let us know how that went.

- TAP Phase 3: Generalization

- Sessions 7-8

- OT assists the caregiver in identifying ways to simplify the activities with disease progression

- The therapist helps the caregiver brainstorm ways to generalize the activity strategies to other care challenges

- May involve training in strategies to simplify communication or adapt the environment

TAP Phase 3 (sessions seven through eight) focusing on assisting the caregiver in identifying/ways to simplify the activities as the disease is progressing and getting more advanced. We are going to help them generalize. How can they take the skills that they have gained and generalize them over to another care challenge? It may involve some training and strategies to simplify communication like we just talked about or adapting the environment.

- Considerations for TAP

- TAP should align preserved functional and cognitive abilities with environment and interests to design activities to maximize engagement

- Identify previous and current interests of the individual to promote a sense of self, even in severe dementia

- Consider the stage of the disease when choosing activity design and set up

- Educate and train caregivers in varied needs for cueing techniques and time for engagement with disease progression

- Consider the time of day to introduce activities to maximize engagement and well being (activities with increased cognitive demand in the am with lower demand at the end of the day)

(Regier, Hodgson, & Gitlin, 2016)

You want to make sure that you align with their preserved functional and cognitive abilities. You have to consider previous and current interests to promote a sense of self. Consider the stage of the disease as well, and we are going to talk about that a little bit more in a minute. You want to educate and train the caregivers and consider the time of day that you are introducing activities to maximize that engagement and wellbeing. Some people might do better in the morning, while others might be more alert in the afternoon.

Characteristics of Activities for Persons With Dementia at the Mild, Moderate, and Severe Stages

- Examined relationships of disease stage with types and characteristics of meaningful activities

- Cueing needs, assist with initiation, recommended engagement time

- 158 activity prescriptions for 56 families

- Mild dementia

- Complex arts & crafts; cognitive activities

- 28 mins activity; cueing 68.3% of time

- Moderate dementia

- Music & entertainment, domestic/homemaking

- 24 mins activity; cueing 78% of time

- Severe Dementia

- Simple physical exercises; manipulation/sensory/sorting activities

- 15 mins activity; cueing 78% of time

(Regier, Hodgson, & Gitlin, 2016)

These are some different characteristics that you may encounter at different stages. This gives you a framework. I want to be really clear that if someone has mild dementia, they have to do complex arts and crafts. We still want to look at what is relevant to the person. You will notice they can do an activity for about 28 minutes, but they still needed cueing almost 70% of the time with mild dementia.

With moderate dementia, the interest goes more toward music and entertainment or domestic and homemaking tasks. They could attend to an activity for about 24 minutes, and they needed cueing, sometimes up to 80% of the time.

With severe dementia, this is often simple physical exercises or different sorting/sensory activities. They will be able to engage for about 15 minutes with cueing about 78% of the time again.

This gives you an idea of how long someone could engage in activities and the level of cueing needed. This is important information for care partners as well.

Strategies for Dementia & Psychosis

- Establish familiar, consistent routines

- Facilitate gradual transitions

- Utilize music to support transitions and orientation

- Coach frequent re-orientation

- Schedule contact with family & friends (phone, video)

- Utilize meaningful hobbies & activities

- Store belongings in predictable, familiar places

- Mark items with pictures

- Maintain a highly visible calendar (refrigerator)

- Decrease clutter/distractions

- Establish cognitive stimulation activities

- Simplify the environment

- Address lighting concerns

These are some different strategies to help caregivers frame the day and establish a routine. What is that going to look like? When transitioning to another activity or another task, how can you make that gradual and not abrupt? Sometimes music can help support that transition. For example, during shower time, we can turn on opera music.

You can coach frequent reorientation. This can be done with pictures, a calendar, using music, or whatever you need to do to bring the person back to orient them to where they are and what is happening. We can schedule contact with family and friends via phone, FaceTime, or Zoom.

Again, use meaningful and cognitively stimulating activities. It is also important to keep belongings in predictable places because that can be a source of agitation. You may need to mark items with pictures or keep a highly visible calendar to help the client. Decreasing clutter and distractions in the environment and addressing lighting is crucial.

Safety

- Train in safety measures for control of medication intake

- Assess for falls risk and home safety

- Address safe use of home appliances

- Prevention of wandering (GPS monitoring); bed/door alarms

- Limit access to firearms

- Assess fitness to drive

- Monitor for elder abuse

- Address need for supervision when necessary

You want to look at safety with medication intake, falls risk, and home safety. As I said earlier, you also want to watch the use of appliances. If they are at risk for wandering, door alarms or a GPS tracker might be options to consider.

There have been some unintentional homicides where a person with dementia was confused and thought there was an intruder. Thus, you want to make sure there is no access to firearms. Fitness to drive is another area we may address.

It is always important to monitor for elder abuse if their paid caregiver or family is coming in. In conjunction with this, we need to make sure that they are getting adequate supervision. Sometimes people think they can leave someone alone when they really cannot. This came up for me with a dear patient and his wife. H