Introduction

Hello everyone. I love this technique as I think it is uniquely OT. Everything that we are going to talk about today really taps into what we as OT practitioners are very likely already doing with our residents. I want to start off with this picture and a quote from Maria Montessori (see Figure 1) because I think this is really meaningful. "What you do for me, you take from me." This is something that she said about her students, but I think is really pertinent for all of us as it relates to quality dementia care. The more that we do for the person, the more we take away from them. We create dependence, isolation by doing for that person.

Figure 1. Maria Montessori.

The more that we can allow them to do and train and coach others to do the same, I think the better off that we will all be.

Dementia

- Researchers predict an estimated 7.1 million American citizens over the age of 65 will be diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) by 2025, a 39% increase from the current number of 5.1 million (Alzheimer’s Association, 2015)

- Health care programs have begun to reevaluate the efficiency of services and quality of care provided to older adults with dementia

- ‘Helping persons reach their optimal level of fulfillment’, ‘enriching the lives of our residents’, and ‘promoting the well-being of older adults’ can be found in most mission statements

Researchers predict that an estimated 7.1 million American citizens over the age of 65 will be diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease by 2025, and that is a 39% increase from the current number that is sitting at about 5.1 million. Now, in response to that growth, health care programs have really started to re-evaluate the efficiency of their services, the effectiveness of their services, and the quality of care that they are providing to older adults with dementia. In doing so, they are seeing clear gaps in the literature. We will talk about some of this as we go along, but most notably, the majority of the research that you look at as it relates to dementia quality care is with individuals who have the beginning stages of dementia or maybe the middle stages of dementia. And while those individuals experience problematic symptoms for sure, there is very minimal research that has really focused specifically on the care of those with late-stage dementia. This is where the Montessori approach really comes into play and can be very helpful. I do not know where everybody works, but if you look at the marketing brochures at your establishment, you might see phrases like, "Helping persons reach their optimal level of fulfillment," "Enriching the lives of our residents, and "Promoting the well-being of older adults." We often see this verbiage in the mission statements, in the program goals, in the program descriptions, and in the marketing materials. I would challenge each of these communities to define what that means to them. Many do a very good job, do not misunderstand me. However, what does that mean to them and how are they achieving that? When you go into a Montessori-based program or community, you can see exactly how they are doing that.

Barriers to Dementia Care

- Single greatest barrier is beliefs

- Concept of ‘therapeutic nihilism’ (Camp, 2006; Clark, 1995)

- Belief that persons with dementia cannot learn new things

As we know, there are barriers to dementia care, but honestly, the single greatest barrier to the provision of high-quality care is not lack of resources, lack of time, or whatever. The biggest barrier is beliefs. This goes by a lot of different names, but Cameron Camp called it "therapeutic nihilism." It is the belief that because people have dementia, they cannot learn new things, or they are incapable of anything but declining. The best that a caregiver can possibly do is to deliver palliative care as this deterioration of dementia unfolds. The role is to care for them, take them to the bathroom, and give them their meals, but past that, you are to just allow the deterioration to happen. This is learned helplessness being delivered on a system-wide scale. This happens because in healthcare, we overemphasize the deficits related to dementia. There is an emphasis on the diagnosis and the treatment of those deficits to the exclusion of acknowledging and utilizing strengths and available abilities or spared skills if you will that that person may still have. Again, this is where Montessori will tap in and utilize those skills.

Montessori Background

- Maria Montessori -- early 1900s

- Individualized instruction designed to enhance practical life skills and sensory experiences (Montessori, 2014)

- Simplify tasks, provide immediate feedback, and promote individualized supervision and learning (Lillard, 2008)

You are probably very familiar with the Montessori approach as it relates to children. Maria Montessori was an Italian educator in the early 1900s and she became very concerned about a group of underprivileged children who were labeled "unteachable." She believed that education was a means of improving quality of life, and she was convinced that these children could learn if they were shown a different way to experience their environment. She developed this program and it was originally designed to teach young children cognitive and social skills. However, it really encompasses individualized instruction designed to enhance practical life skills and sensory types of experiences. These Montessori practices have been been very effective for children. The task is simplified and immediate feedback is provided to promote individualized supervised learning. It is very effective. If you have ever been to a Montessori school, you know that. The Montessori approach for dementia care is based on that. She was working with children with mental disabilities.

Montessori Method

- Dr. Cameron Camp adapted the Montessori method to treat people with Alzheimer’s

- Engages the senses and evokes positive emotions

- Stimulation of cognitive, social, functional skills

- Conducted one-on-one

Then, around 30 years ago, Dr. Cameron Camp, an American research scientist in the field of aging, adapted the Montessori method to address those needs of individuals who have Alzheimer's or related dementia. He is a phenomenal speaker. The adaptation is very similar to that in pediatrics. It seeks to engage the senses, evoke positive emotions, and it is the stimulation of cognitive, social, and functional skills. Ideally, it is recommended to be performed on a one-on-one basis. However, I think we all know that it can pose a significant challenge to a lot of different facilities because of the low staff to client ratio to accomplish that. Sometimes, you can get the activities department, volunteers or family members involved, but one-on-one is ideal. While one-on-one is ideal as noted above, it can be completed in small groups as well. In fact, research indicates that there is a strong positive engagement when you have a small group. I think this is important for us, as OTs, because we may not always have the opportunity to complete one-on-one treatment. We might be doing things more on a concurrent or a group basis. It is good to know that the Montessori approach will work for that.

Benefits to Montessori Approach

- Increase social engagement (Judge et al., 2000; van der Ploeg et al., 2013)

- Enhance attention, affect, and decrease agitation (Judge et al., 2000; van der Ploeg et al., 2013; Vance & Johns, 2003)

- Decreased problem behaviors (Giroux, Robichaud, & Paradis, 2010)

- Improved self-feeding (Sheppard, McArthur, & Hitzig, 2016)

- Sensory and cognitive stimulation (Camp & Mattern, 1999)

- Improved work satisfaction at work and reduced staff turn-over (De Witt-Hoblit et al., 2016; Roberts et al., 2015)

What are the benefits to the Montessori approach? You can read all of the different references above, but the common theme is that it improves social engagement, decreases agitation, and enhances attention specifically attention to a task. It may also alter somebody's affect, particularly in long-term care. We see decreased "problem behaviors" as we are helping to meet the psychological needs of the residents as well. There are a lot of really strong positive benefits. This is across different settings like adult daycare settings, home care settings, long-term care, residential, et cetera. The activities within the Montessori approach also have been shown to provide sensory stimulation, cognitive stimulation, and they allow for the expression of social skills. We will see what those look like in just a minute. I think this last one is really important. These intervention programs also have a positive impact on work satisfaction and staff turnover. Staff feels better about the job that they are doing, and then that filters down to the residents. When we get to the very end, you will see a few quotes from staff, specifically from nurses, on how this has improved what they are doing in their day-to-day work. So, there are benefits to the residents and to us as well.

Montessori with Late Stage Dementia

- Increased active engagement, pleasurable affect, less anxiety (Orsulic-Jeras & Judge, 2000)

- Increased engagement and carryover of functional tasks (Camp & Skrajner, 2004)

- Improved ADL (e.g., eating) (Lin, Huang, Watson, Wu, & Lee 2011)

- Reduced behaviors (De Witt-Hoblit, Miller, & Camp, 2016; Lin et al., 2009; Roberts, Morley, Walters, Malta, & Doyle, 2015)

- Improved language (Van der Ploeg et al., 2013)

There is also research on late-stage dementia. One of the drawbacks of these studies is that the sample sizes are just a little bit smaller than some of the early stage and middle stage dementia types of studies. However, the results are essentially the same. They find that participants in the Montessori program exhibited more active engagement in activities, a more pleasurable affect, and less anxiety as it was compared to a control group. These types of studies have also been replicated and improved task carryover and functional abilities were seen. There were also increases in daily living skills like eating, simple dressing, and grooming types of activities. There was also a reduction of behaviors in those with severe dementia and language issues. Through the Montessori types of activities and the approach, even if that person was non-verbal, they were able to communicate wants and needs via the activity. I think this information is very positive.

Montessori Overview

- Emphasis on:

- Independence

- Freedom within limits

- Respect for a person’s natural development

- Simple activities that provide a sense of accomplishment and connection with personal history

When we look at an overview of the Montessori approach, there is an emphasis on independence, freedom within limits, and respect for that person's psychological, physical, and social development. Many times, we do not let an individual with dementia have a knife, as an example. They have used a knife their whole life, for 50 or 60 years, and now suddenly, they are not safe? We need to have respect for that person's development. If you have an opportunity, look up some of the neat videos related to Montessori. I watched one online where there was a group of women cooking. They had cooked all their lives, and they were making this huge pot of soup. They peeled the potatoes and chopped the vegetables. They did everything they were supposed to do including cooking the meat. They did all this with very distant supervision and almost completely independent. Again, when we allow individuals to do what they have done their whole lives, we do see that they are able to carry that over.

We will review a lot of these principles more as we go along, but the activities are simple, modifiable, and practical. Whoever sets up that activity (therapist or caregiver) uses everyday items. The activities are not contrived. You do not need to go purchase something from a catalog. You use whatever supplies are available to you. And, if a task is too easy, you increase the difficulty. Isn't this what we do? We adapt activities to match the performance levels. Completing that activity leads to a sense of accomplishment while reconnecting that person, hopefully, with a part of their personal history. If the person really enjoyed cooking or baking, in a safe kitchen environment, we set them up to do that. If they were a housekeeper or what have you, then maybe we have them match and roll socks or fold towels. It could be different puzzles. Perhaps, it is plumbing tubes that need to be put together if somebody was a handyman. You need to think creatively about what you can pull together. What we are learning is that individuals who have dementia can come not only to enjoy the process of participating in something that they used to do, but they also come away with that sense of accomplishment that can help improve their quality of life.

Alignment with Person-Centered Care

- Montessori activities align with person-centered care

- Emphasize:

- Respect

- Dignity

- Independence

- Provide more structure, individualized attention (smaller groups), opportunities for interaction, adequate sensory and cognitive stimulation vs. traditional LTC activities

(Camp & Mattern, 1999; Judge et al., 2000; Orsulic-Jeras, Schneider, Camp, Nicholson, & Helbig, 2001; Giroux et al., 2010; Orsulic-Jeras et al., 2000; Volicer, Simard, Heartquist Pupa, Medrek, & Riordan, 2006)

The Montessori activities also align with person-centered care. I do not think it matters where you work, that is now the buzzword. Person-centered care, person-centered living, and person-directed living are all being used to emphasize respect, dignity, and independence. This can be used with somebody of any age.

Montessori activities are more structured. They are better provided on an individualized basis; however, a smaller group could work so that you could still provide individualized attention to each person. There are opportunities for interaction, sensory components, and cognitive stimulation. If you look at some of the activities that we see in long-term care like bingo or a big music program in a day room, it may very difficult for the person with late-stage dementia to participate. We need to look at modifying tasks to provide that needed structure.

The Basics of the Montessori Method

- Use Everyday Materials

- Match Interests & Skills (group/individual)

- Use Past Experiences & Preferences

- Adapt According to Cognitive & Physical Status

- Simplify as Much as Necessary

Let's start to go through what we call the basics of the Montessori method. The first is using everyday materials. We just talked about this. Now, when we talk about materials, they are not designed to be toys, but rather they are tools to practice independent living. These are things taken from the everyday environment and that are familiar to that person in terms of sight, touch, and smell. We want the person to not only interact with them and use them functionally, but we want it to also have a sensory component so they have the opportunity to reminisce. It could be measuring cups and they could talk about how they used to bake. In a later slide, I have some spices. You could use these to ask, "What did you use to make with these?" They could smell something and it might invoke a memory.

Next is matching interest and skills. This is a unique aspect of this approach. It is modifying that activity based on not only their cognitive and their physical ability but also their background and their interests. When Maria Montessori was working with her students, she always started with their capabilities and needs. What were they able to do? What do they like to do? You do not want to frustrate them, but you need to make the task just a little bit beyond their comfort zone. They still have the opportunity to improve.

You also want to use their past experiences and preferences in trying to determine what those activities are. Obviously, if the person can tell us, we are going to solicit that information. As we get into those later stages of dementia, that may not be the case, so we may have to go based on what we know. If the person traveled a lot, maybe you do a matching activity with cities in Europe versus cities that are not in Europe. Or, if they enjoyed geography, you could do something with countries. If somebody enjoyed gardening, you could have them sort pictures or words into categories like fruits versus vegetables. You base your activities on their preferences and what you know.

You are also going to adapt activities based on cognitive and physical status, and that makes perfect sense. We need to tailor it to something that they are actually able to do. If it is something that is past their abilities right now, we are only going frustrate them if we push that narrative.

We simplify it as much as necessary. This is very familiar to us. We break down that activity into smaller steps that can be mastered and then sequenced and put together in order to engage.

- Assessment of History/Background

- What do they like to do?

- What is their history?

- Strengths and limitations?

- Environment -- what contributes to successful engagement and what hinders it?

- Relevant life experiences, values, interests?

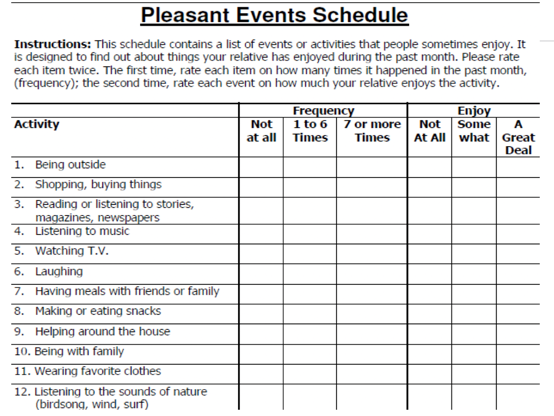

Before I go on to the other parts of the basics, if you will, I want to know their history and background. What are their strengths, limitations, and occupational performance? What is their environment? What contributes to successful engagement and what hinders it? What are their life experiences, their values, their interests, and their whole background? Hopefully, we are using some tools to do that. I am not going to say that you have to use one tool over another, but there are a lot of options out there. There is the COPM, the Activity Card Sort, the Pleasant Events Schedule (see Figure 2), the Preferences for Everyday Living (PELI), the Roles Checklist, and the Interest Checklist.

Figure 2. Example of the Pleasant Events Schedule. Free to use. https://www.healthnetsolutions.com/dsp/PleasantEventsSchedule.pdf

I do not think it matters what it is that we use, just use something to try and tap into that. I think I speak for a lot of us when I say it is disheartening when you walk into an OT clinic and everybody is using Thera-Band, exercise equipment, or they are lifting weights. Occupational therapy is about doing something that is functional, meaningful, and purposeful to that individual.

- Match Speed to Ability

- Progress from Simple to Complex

- Demonstrate

- Encourage & Assist

- Evaluate

Continuing on the basics of Montessori, we want to match speed to ability. This is a basic one. Obviously, you do not want them to go too quickly if they are not able to do that. You need to bring it down to something that is manageable for them.

The next one is the progression from simple to complex. Based on Maria Montessori's work, we are going to progress them from something very simple to something more complex, from something concrete to then abstract, and go backward if you need to. If they are in a stage of dementia where they cannot handle anything abstract or complex, you bring it back down. You can also adapt and make it harder once indicated. We just talked about the activity of matching pictures of things in different countries. To make it a little more difficult, you could add a fine motor component to it. Perhaps, you have the person cut out the pictures and then use those in the activity. There are a lot of different things that you can do.

If you are going to demonstrate something to the individual, whatever that task is, make sure you put something in their hands that is related to the task. They may not comprehend if you just tell them depending on the stage of their dementia. However, if they have something in their hands, they are going to start to make that connection. The other piece is that you want to demonstrate with step-by-step showing, or "tell, show, do" in as few words as possible. You want to use minimum vocalization in a nice, serene atmosphere. It can be very confusing to give a lot of verbal directions so stick with just the demonstration, and again, give them something to manipulate while you are doing that.

We need to evaluate. Take a look at the session. If it did not go well, go back to the drawing board and figure out what you need to do to change that activity so that that person will be successful and get something out of it.

- Activity Requirements

- Gross motor

- Repetitive

- Uses familiar motions

- Involves 1 or 2 steps

- Observable effect on the environment

- Non-competitive

- Involves few or no rules

Thinking about the activity requirements, we adapt activities. It is what we do. We want the activity requirements to include gross motor, repetitive, and familiar motions. You can certainly incorporate some fine motor tasks if the person is able to do that, involving just a few steps. We may be able to then link those steps together. There needs to be an observable effect on the environment. We do not want to just do something willy-nilly without that person knowing the purpose and the why behind it. When we do some of the more contrived types of activities, we assume that the person knows what we are doing. The person does not necessarily know why you are working on arm strengthening to increase dressing as an example. They need to see that observable effect. It should be noncompetitive with very few rules. To understand that last point about the rules, think about the difference between free play and recreation. We engage in recreation as adults that have a lot of rules, but children do not. We want to add structure, but we do not want a lot of rules. We want the activity to be engaging, informative, and exploratory to a degree.

- Considerations When Adapting Activities

- Attention span

- Environmental scanning

- Awareness of purpose/goal

- Communication

- Physical attributes

- Quality of work

- Problem-solving

- Sequencing

- Social factors

- Environment

- Ability to initiate

- Ability to choose

- New learning ability

- Direction following

- Response time

(Warchol, Copeland, & Ebell, 2002)

As we continue to talk about adapting activities and what types of activities would be useful, I love this particular slide. I recognize that it is a little on the old for articles, but it is still 100% pertinent, and it talks about things that we want to consider when adapting activities. I am just going to go through a couple of these that I think hits home. Attention span is the first one. In the early stages of dementia, a person can attend for 20 minutes, give or take, with one or two verbal cues. In the middle stages of dementia, we are looking at five to 20 minutes with intermittent verbal cues. Once we get to that late stage of dementia, they need constant cueing, and they may not be able to attend at all. When that person with late-stage dementia is brought to that large day room for a bingo game or music activity, are they really able to attend? I think probably not.

The next one is environmental scanning. In the early stage of dementia, they can only scan about 24 inches in front of their eyes. When we get to the middle stage, we are looking at about 14 inches, and then at the later stages, we are looking less than 14 inches, maybe only six to seven. So, if you are giving them an activity to do, and it is across the room or even the table, they may not be able to see it. I am going to skip through the middle section here because I think we know that as the disease progresses, we lose a lot of these abilities like recognizing the quality of our work, problem-solving, sequencing, et cetera.

Direction following is where I am going to expand upon. In the early-stage, clients can follow simple verbal directions. In the middle stage, they can only usually follow one-step verbal commands and probably no written ones. Then, once we get to those later stages, it is going to be probably hand-over-hand assist. Additionally, their response time declines. In the early-stage, response time is slower than normal. When we get to the middle stage, they are at about 15 to 20 seconds, and then when we get to the later stages, the response time could be significantly longer. Each of us has probably experienced a scenario where you have asked a person with late-stage a question or asked them to do something, and it can be several minutes later when that person finally follows through. We have to recognize that and slow it down a little bit as we start to do some of these activities.

- Structure

- Immediate feedback

- High probability of success

- Repetition

- External cues

- Procedural/nondeclarative/implicit memory

We already have gone over some of this. Persons with dementia obviously need structure and order in their environment, and changes can be very upsetting. Maria Montessori said the exact same thing about her students. All activities will have some sort of structure and order that will comfort that person and allow their attention to really be focused. Following on a theme here, these clients need immediate feedback, a high probability of success, and a lot of repetition. The Montessori program also makes use of a number of other types of things that again, as OTs, we are very familiar with. Things like task breakdown, guided repetition, progression from simple to complex are integral to this program. We are also going to take advantage of their procedural, non-declarative and implicit memory storage. The individual who has dementia probably is not going to learn new things necessarily, but we certainly can tap into their procedural memory. We will talk about the external cues in just a minute, and you will get an opportunity to see that in some of the activity templates.

- Self-Correcting activities

- Social participation

- Tailored to the individual, most delivered in groups

- Integrated into every facet of daily activities

- Right to refuse

- Modify for success

- Guided/structured repetition

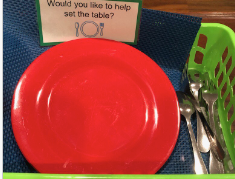

The activities that we are using should be self-correcting due to those external cues. They inherently provide the clues to let an individual know that they did it completely and successfully. For example, maybe it is setting the table, and you will see a template on this in just a little bit. There is a circle on it for a plate and a place where your silverware goes. With the template, they know exactly where everything goes.

There is also a lot of social participation related to the Montessori types of activities. One specific one is a reading round table. I am not sure if you have heard of that, but it is a very unique reading discussion activity. They actually take adapted printed stories, and they adapt them to a person with dementia. It is a large print, and there are cues to guide people through the story. Individuals in a small group again take turns reading and then answering questions about the story.

We have talked about tailoring activities to the individual, but it does not have to be in groups. It could be a simple hand massage that takes five minutes, or it could be laundry sorting that could be 30 to 60 minutes. Group activities typically are about 30 minutes on average. I think it is important that we know that in group activities everything is integrated into every facet of the resident's daily activities. It is the majority of their waking hours, not just their time in therapy, but all of the time that they are awake with the exception of when they are sleeping, using the restroom, or something. It is incorporated into their entire day. With that said, they also have the opportunity to refuse, and we can modify it. For a resident who is sensitive to a lot of different stimuli, instead of participating in a group activity, they could go for a walk with the person instead or do something a little bit different, like a flower arranging activity. And, if the person does not have the fine motor ability to arrange the flowers, maybe they can participate by verbally communicating to the leader which flowers use and where to place them. Again, we are looking at procedural memory and structured repetition so that an individual can actually perform an activity.

Creating Activities (Elliot, 2011)

How do you create the activities and what do they look like? Let's continue on that theme.

- Step 1

- Question why the person living with dementia is behaving in certain ways or demonstrating behaviors

In the first step, you are going to question why the person is behaving in a certain way. Are they apathetic? Are they melancholic? Are they frustrated? Are there repetitive behaviors? Why are they behaving in the way that they are, positive or negative? How could an activity help them?

- Step 2: CREATE

- C: Consider needs, interests, skills, abilities

- R: Remove clutter

- E: Error-free

- A: All materials are modifiable

- T: Templates to support declarative memory

- E: Evaluate the activity

You are then going to create the Montessori activity. You can see the mnemonic here. First, you are considering the needs, interests, skills, and abilities of that person. What is going to support their independence? Remove unnecessary markings and clutter so that whatever it is that you are working with is easily seen and recognizable. Make sure that the activity is error-free. Thus, the focus is on the process of the activity rather than on the outcome. Provide all of the materials and modify them as you need to. Provide templates, which we already talked about, and environmental cues that help to support their memory. And then, evaluate that activity to determine whether or not it used those principles.

- Step 3: PRESENT

- P: Prepare the environment

- R: Room set up

- E: Extend an invitation

- S: Show the activity

- E: Error-free

- N: Needs, interests, skills, abilities (modification)

- T: Thank you

When you are presenting the activity, and this is important, you present it in a very specific way. Prepare the environment with a choice of at least two activities. You set up the room and remove distractions. The therapy gym may not the best place for some of this. Then, you extend an invitation. "Would you like to come with me and arrange some flowers?" Or, "I would really like your help in folding this laundry. Would you be willing to help me?" You extend an invitation. You demonstrate it, and as we already said, use few words. Then you suggest that the person try the activity. "Here, try it. Let me see how you do." Ensure that it is error-free and make sure that the person is actually enjoying it. Offer assistance and modify it when needed. Finally, I think this is really important. You thank them. "Thank you so much for helping me today. I'm going to need to do this again tomorrow, would you be willing to help me again tomorrow?"

Meaningful Activity

- Every activity must . . .

- Have a purpose that is obvious to the participant

- Be voluntary

- Be pleasurable

- Be socially and age-appropriate

- Be failure proof

Remember, every activity needs to be purposeful, voluntary, failure-proof, and socially and age-appropriate. These are all of those things that we have learned over and over again with quality dementia care.

Montessori Approach

- Every participant should have an activity that he/she can successfully handle

- If materials are used inappropriately, but engagement is strong, let the activity occur

- Provide demonstration as needed

- Matching Shapes/Colors

- Color Sorting

- Picture Puzzle

- Pairing & Sorting

- Sensory Boxes

Participants need to have activities that they can successfully handle. You, as the facilitator, will most likely sit on the dominant side of that individual. You need to understand that they might not do the activity how you intended, and that is okay. If the participant engagement is really strong, they are involved, and they are enjoying themselves, let it go. There is no right or wrong way to do it, particularly if the engagement is good. You can come back another time and try to correct them, but that is not advisable in this situation. We already talked about the demonstration portion, and now we are going to talk about the different types of activities. Generally speaking, the activities will fall into one of these categories.

- Cognitive Skills

- Life Skills

- Movement

- Sensory

- Music

- Art

- Socialization

Again, are we going to improve cognition? No, I think we know that, but maybe for some of our individuals who are in those earlier stages of the disease process, you can have discussions about current events or complete some brain challenge activities, like simple puzzles, matching words with objects, identifying landmarks, or having a conversation about an object. In this activity, you give the client an object that they would have used in their lifetime, and you can reminisce a little bit about it.

Then, there are life skills. I think this is where a lot of where Montessori activities tend to fall. These are activities like planting seeds or using handtools is they used to be a handyman. It could be raking, watering plants, working on the car, baking, folding clothes, et cetera.

Movement is very important whether that person is seated or standing. We can incorporate movement into many activities. We also want them to use deep breaths and a full range of motion if at all possible. Activities like picking an apple from a tree, picking flowers dusting, sanding, and sweeping are going to be so much better than a rainbow arc. Again, these could be modified for either sitting or standing.

Sensory activities are also very important. This could be using candles with aromas. You could have a scent that you match with a picture so they can put that together and have a conversation about it. You could use different types of fruit that they try to identify by its texture and taste. I think the important piece is that it is not just the visual aspect that we want to tap into, but we also want to incorporate taste, touch, and sound as well.

Music is a really popular and effective way to engage with individuals who have dementia. Activities could include listening, identifying, dancing, and singing. Church hymns and patriotic songs are identifiable by a lot of people.

Art programs can encourage drawing, painting, or copying a photo.

Socialization is the last category. One of the best socialization activities, as you know, is dining. They could work on setting the table, serving the food, and engaging with people who are at a table.

- Early-stage of dementia

- Activities that focus on the whole task

- Mid-stage of dementia

- Activities that focus on the individual steps of the activity

- Late stages of dementia

- Activities that focus on the sensory part of the activity

When we look at the activities that we would be setting up by stage, for early-stage dementia, you can look at the whole task. This could be the whole recipe to bake a cake, potting bulbs, or making a birthday card. When you get to the middle stage of dementia, you are going to start focusing on the individual steps of that activity. Instead of the full recipe, it might just be whisking the eggs or measuring the flour. Rather than potting all the bulbs, it might just be putting the dirt into the pot. And then those later stages of dementia, it is focusing on the sensory piece. It is not the activity itself, but it is the tasting or smelling of the cake. They could run their fingers through the compost. They could scrunch the tissue paper for the sound and the feel of that. When we look at the activity, it is still the same activity, but you have multiple people working on different stages.

- Issues that may occur

- Lose focus

- Walk out

- Lose interest

- Place small objects in their mouths

Of course, issues may occur. Participants can get agitated, bored, and infringe on the space of their peers. If they lose focus, re-establish eye contact, and just ask them, "Hey, do you mind helping me just a little bit longer? Give me five more minutes," and see if they'll engage. They may walk out, and that is fine. If they walk out, go with them for a while and then invite them back. And if ultimately, they do not want to come back, again that is fine. We are not going to restrict that person or not allow them to refuse. If they lose interest, maybe you grab the project or the activity, and you work on it a little bit and then hand it back to them. Oftentimes, that will work, and the person will want to get involved again. They may place objects in their mouth, so of course, we want to have some sort of supervision.

- Sensory kits

- Offer an opportunity to stimulate as many senses as possible, for example:

- Balls box

- Cereal Box

- Kinetic Sand

- Seeds

- Food

- Offer an opportunity to stimulate as many senses as possible, for example:

We already talked about sensory input, but the sky is the limit here. You will see this in my photos here in just a second. I like to keep boxes with different textures like squishy, plastic, and fabric, and things they can interact with. It could be uncooked oats or rice where they can use spoons, cups, and other utensils to sift, sort, pour, and measure. Kinetic sand is a fun material to use as well. You can also use materials from outside like seeds, acorns, pine cones, but you just need to make sure the items are not too small. You can also cut food up, and they can smell, touch, and taste it. My mantra with sensory is design on a dime. There is a lot of expensive sensory equipment available for individuals with dementia, and while it is very appropriate in many cases, some people do not have the money to pay for that. I like to find things I have or things from nature.

- Five domains of function

- Cognitive stimulation

- Life skills

- Motor movement and fitness

- Sensory stimulation

- Socialization

The activity kits tap into these five domains of function. These kits contain all the items needed for a particular task and are typically organized and clean. For individuals with early dementia, they can grab the activity and follow the directions on a job card. They can sit down, do the activity, clean it up, and put it away. The sky is the limit. For cognitive stimulation, one example could be poker chips and cards. Or, it could be matching tiles. For life skills, a box could contain the supplies to polish shoes or other self-care supplies. There could be fine motor activity kits like scissors to clip coupons and sandpaper and wood. Kits can also include motor types of things like used for sweeping, vacuuming, raking, and cleaning windows. Sensory stimulation kits can have different textures and items hidden in rice as an example. For socialization, you can do activities like filling in the blank, stating favorite foods, and stating favorite holidays, et cetera. You can even make an activity out of something as simple as a big bin of buttons. You can talk about the buttons. "What kind of coat do you think this went on?" "What kind of shirt do you think this wend on?" "Did you used to sew?" This is having a conversation around an activity.

- Tailored Activity Programs/Kits

- Tailored Activity Programs reduce behaviors and increase engagement (Gitlin et al., 2008)

- Activity kits improve the quality of visits and QOL (Crispi & Heitner, 2004)

- Individualized and meaningful activities show positive results (Pool, 2001)

The activity group kits are great. Research shows that activity kits improve people's quality of life. In fact, 57% of residents had positive results for well-being when caregivers and/or visitors would come in and grab the kit and work with the person versus just sitting there and having a conversation.

Activity Ideas

Let's take a look at some of these activities.

- Golf ball scoop

- Living/non-living or Happy/not-happy

- Memory BINGO

Figure 3 shows a "golf ball scoop" using plastic balls.

Figure 3. Golf ball scoop.

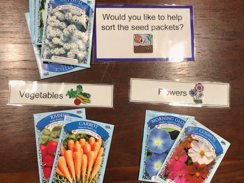

They could name the colors or use an ice cream scoop to modify the task. You have them transfer them from the basket to a muffin tin and then put them back. This also mirrors the hand-to-mouth pattern for self-feeding. Another task is having them identify living versus nonliving objects. In Figure 4, I set this up so that they would sort the seed packets into vegetable and flower categories.

Figure 4. Seed sorting activity.

Another task could be sorting happy versus not happy facial expression cards. Memory bingo is a very specific activity where each participant gets playing cards with printed answers to corresponding cards. So the calling card has a phrase on it, something like Fred Astaire and Ginger blank, and they have to play a card when their phrase is called. It is easier, obviously, because they have the words in front of them. It is similar to Cards Against Humanity type of thing where you play a card based on a phrase. The procedure remains the same every time the game, but the content changes so it is an exploratory type of activity.

- Cognitive stimulation

- Sorting

- Matching

- Discussion

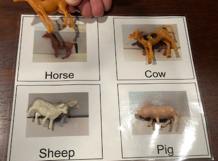

Next, for cognitive stimulation, you can use sorting tasks like multicolored measuring spoons and cups. It could also be food groups, holidays, or favorite foods. They can count, spell, arrange, or reminisce with this activity. In Figure 5, I am showing a template where they match the animal with the picture.

Figure 5. Matching animals using a template.

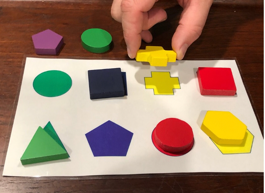

There is another template that I do not have photographed that shows a "real animal" versus a plastic one. Thus, we are asking them to take the next complex step and match a plastic animal to its real-life counterpart. In Figure 6, you can see that they are matching shapes with a template.

Figure 6. Matching shapes to a template.

Figure 7 shows a shelving unit with the different bins on it.

Figure 7. Activity bins.

This is probably not exactly how I would set it up, but this was set up at a trade show. I would probably have it a little bit lower to the ground, a little bit brighter, and probably without those large sides on it. However, in this picture, you can see the activity bins that are available.

- Life Skills

- Meal-related

- Sorting Pouring

- Squeezing

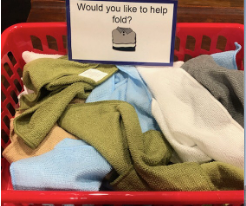

Next, there are some life skills activities. Again, the sky is the limit here. You can see we have folding here in Figure 8.

Figure 8. Folding laundry activity.

"Would you like to set the table?" This is the bin for that activity. In there, the person would find all of the components for setting the table in Figure 9.

Figure 9. Setting the table activity.

Figure 10 shows material for crocheting.

Figure 10. Crocheting activity.

You can have activities be related to meals. They could pour the water from pitchers for a lunchtime activity, squeeze oranges to make freshly squeezed orange juice, or scoop out food onto plates. Even snapping beans is a great activity. Again, they can use knives and chop. They do not have to have a super sharp knife. They can also sort the silverware.

- Sensory stimulation

- Massage

- Olfactory

- Rice bin

Here are some examples of sensory activities. We could do hand massages with scented lotion. The rice bin is again one of Dr. Camp's favorite activities. They can find treasures with a slotted spoon. Figure 11 shows an olfactory type of activity.

Figure 11. Spice activity.

Here are different types of textured balls in Figure 12.

Figure 12. Textured balls.

Again, they can interact with items from nature (see Figure 13).

Figure 13. Bin with seashells.

Seashells all feel different, smell different, look different. This can spark a conversation. Figure 14 shows light tubes and the fiber optics

Figure 14. Light tubes and fiber optics.

You can find a lot of very visually appealing things just in your own environment. You can see there is definitely visual appeal to a lot of these different things.

- Templates

These are the templates that we talked about. Figure 15 shows a template for dining.

Figure 15. Dining template.

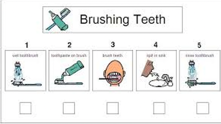

There is also a template for the steps on brushing your teeth.

Figure 16. Teeth brushing template. (Credit: Rachel Dellinger)

I had one person who never remembered to take out their dentures. We actually put a template of their dentures and their denture cup on their night table as a reminder to always take out their dentures and put them in the cup. Once they did it many times using the template, it became a habit. When you can use those templates, the person knows exactly where those items go and they know when they are successful.

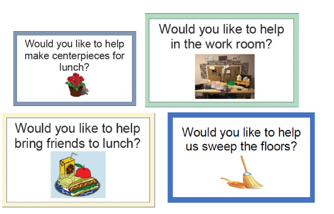

- Job Board

This is a job board in Figure 17.

Figure 17. Examples of jobs on a job board.

You can put all of these on one "job board." These match the previous pictures on the bins. You can see that it follows the Montessori principles. "Would you like to help make centerpieces for lunch?" "Would you like to help bring friends to lunch?" It is asking them to be engaged in the activity. Again, they can choose what it is that they would want to work on.

- Intergenerational activities

The Montessori approach has also been really useful to help individuals who have dementia serve as mentors to young children. This is by using activities as a teaching device (see Figure 18).

Figure 18. Intergenerational activities.

Examples are how to fold clothes, how to use tools, how to sand down wood, how to pronounce letters, how to count, how to add, how to write in cursive, and so on. This type of programming has been really positive to get engagement not only in the children but also in adults. Additionally, it has been very helpful in adult centers and long-term care facilities. The beauty of these relationships is that the senior can teach the child, but the child can also help the adult. The kids can teach seniors how to use a computer and access social media. For example, in the far bottom corner, the gentleman is painting. This is a very good sensory and visual activity that you could do hand-in-hand with kids. On the far right, you the two generations walking in the woods. This may not be appropriate for everybody, but it can be a great activity that taps into both the sensory and motor systems.

Case Study

- M was an 85-year-old woman with moderate stage dementia residing in a long-term care facility

- Often refused to take part in the activities that were offered at the facility, preferring to stay in her room alone most of the time

- The activity chosen for M was arranging flowers

- M had once enjoyed gardening, so it was surmised that she might find this activity meaningful.

M is an 85-year-old woman. She has moderate stage dementia and is residing in a long-term care community. She often refused to take part in the activities that were offered and preferred to stay in her room alone most of the time. This placed her at risk of becoming socially isolated because she just did not have social interaction.

- Montessori principles

- Providing a meaningful activity based on remaining skills

- Use of every day/familiar materials

- Beginning the activity with an invitation

- Demonstrating how to complete the activity

- Breaking the activity down into steps

- Providing closure to the activity

The activity that was chosen for her following the Montessori types of principles was arranging flowers. The activity required her to take silk flowers and arrange them in a basket with floral foam. It used fine motor skills (pincer grip strength) while pressing the flowers against the resistance of the foam. It also allowed the client to make choices of which flowers to use and where to place them. M was an avid gardener so it was surmised that she might like this activity and find it meaningful. The facility staff member in charge of the activities program was the facilitator. On the first day of the activity, she introduced herself and said, "Would you like to arrange some flowers with me?" M replied, "No." She had no interest and refused to participate. We have all heard that before, right? Not to be discouraged, the staff member said, "Would it be alright if I worked on this arrangement here in your room? It is really crowded out there in the activities area, and I just need a quiet place to work." M replied, "Sure, you can stay." So, the staff member began working on the arrangement independently and periodically would ask M which flower to use in the arrangement and where it should be placed. Sometimes M would reply, and sometimes she replied that she did not care. Occasionally, she gave a suggestion. And, every time she gave a suggestion, the staff member thanked M for her input. When the activity was done, she said, "Thank you, I appreciate you allowing me to use your room. Maybe I'll see you tomorrow." The following day, the staff member came back to M's room with a flower arranging activity again and asked if she would like to participate. Again, M refused. The staff member said, "Okay, do you mind again if I work here today?" M agreed. This time, the staff member tried to involve M even more by presenting two flower choices to her and saying, "Which one do you think I should use?" At first, M hesitated, but eventually, she made her choice. This continued for the remainder of the session with the staff member asking M which flowers to use or how to arrange them. Throughout the session, M started to reminisce about her own garden, her favorite flower, and she started to smile, but she still never manipulated the flowers herself. Near the end of the session, she actually instructed the staff member to place a flower on the right side of the basket, and the staff member purposefully placed it on the left side of the basket. M leaned forward, moved the flower back to the right side, and this was the first time she actually manipulated them. At the end of the activity, the staff member said again, "Thank you so much. Would you like to arrange flowers with me again sometime?" To which M said, "As long as you follow my directions, I will." The following day, the person walked in and said, "Would you like to arrange flowers?" And immediately M sat up and said, "Yes, I would love to. When are we going to start working with them?" This is a real case study by the way.

What are the Montessori principles here? The staff member provided a meaningful activity based on her remaining skills. This included fine motor coordination, color discrimination, and familiar activities. The staff member began with an invitation, demonstrated how to complete the activity, broke it down into the steps, and then provided closure. "Thank you for participating. Would you like to do it again sometime?"

- Key takeaways

- All individuals, no matter the level of impairment, can, and should, be provided with opportunities to engage in meaningful activity

- Some will need to be eased into the activity

- Try to spark interest and build rapport

- Small decisions to increase involvement

This case study highlights several different important points. First, it illustrates that no matter what the level of impairment, somebody can and should be provided with opportunities to engage in meaningful activity. It also highlights that some people are going to need to be eased into an activity gradually by doing only portions, sitting on the fringe, or by just giving some input verbally before they actually get into the activity. By gradually doing that, they realize that they actually can participate. The staff member again went in and she refused and she said, "Well, do you mind if I work here instead?" This sparked interest and built rapport. Then by the third day, the person was much more comfortable with the staff member and was sitting up in anticipation of the activity. They made very small decisions to increase involvement over time.

Summary

We hit a lot of principles here. Montessori activities are not complicated or contrived. They are simple, using everyday materials and activities. They do not always have to be in a group and can be one-on-one. It is important to simplify the task and provide immediate feedback. These activities can be performed by you in therapy, by nursing, by the activities department, or anybody who wants to do this. It is necessary for the client to understand the purpose of the activity or be purposeful and meaningful. Remember that everybody, no matter what their level of impairment can be provided with opportunities to engage in an activity. Remember that the activity should follow the stage of dementia. Thus, in the early stage of dementia, the whole activity is used. In the middle stage, we are going to focus on the individual steps, and then the late stage, it is more of a sensory focus. It should have very few steps and have an observable effect on the environment. Again, we can link some of those steps together, but they should be one or two steps. Remember, you always want to demonstrate the activity using a step-by-step guide and using as few words as possible. And, if they engage in the activity but not exactly how you wanted them to, let it go. You want them to enjoy themselves, not necessarily completing your to-do list. If they lose interest in an activity, work on it yourself, and then hand it back to them and invite them to continue. If they still refuse, that is okay. You can try to offer them a different type of activity or a different choice. Again, these activities are supposed to be self-correcting because they provide cues or clues to the person to let them know if they have completed it successfully. I think these are all principles that are pretty inherent to us as OTs.

Staff Feedback

Here are some examples of staff feedback.

Activities:

- “I can see they are much happier after the group. I thought they were slow and irresponsive, now I know I was wrong.”

- “I would not have thought to give them that activity before.”

- “Now I know that if we give them a chance, they can achieve something after all.”

- “Staff can give these residents something to do where they feel useful and they’re enjoying their time as opposed to, you know, maybe looking for negative attention.”

Nurses:

- “You can either spend the time responding to those behaviors OR you can implement the little two-second activity and let them work on it for half an hour... it really isn’t time-consuming – where do you want to spend YOUR time?”

- “…seeing it work and seeing the residents get engaged and smiling and taking part in an activity, especially residents when they don’t think that they’re capable really of doing much of anything ... it’s a bit of a shocker.”

- “Sometimes families get lost when they come in as to how to have a quality visit with their loved one when ‘‘mom doesn’t even recognize me.’’ So this gives them a tool also to have that visit in a meaningful manner.”

Questions and Answers

Would the Montessori-based approach fall under maintenance therapy?

I think that is a great question. It might, or it might not. As you are developing a program of di