Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Occupational Therapy For Driving And Adaptive Equipment, presented by Michelle Fisher, MOT, OTR/L, ATP, CDRS.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to:

- Recognize occupational therapy's unique role in driver rehabilitation.

- Identify visual, cognitive, and physical occupational performance factors that may affect driving.

- List possible adaptive equipment options to meet a client's needs.

Driving and Community Mobility

- Why?

- Independence

- Driving is the most meaningful IADL for 27/30 individuals with stroke and caregivers (Dickerson, Reistetter & Gaudy, 2013).

- The Bureau of Transportation reports that 25.5 million Americans have disabilities that make traveling difficult outside the home. Of that 25.5 million, 3.6 million Americans do not leave their home because of their disability.

- The Bureau of Transportation also reports that personal vehicles are used most widely regardless of disability; however, people without a disability use them more often.

Some may be wondering why driving and community mobility are so important. I like to think about what I would do if I could no longer drive. I know I would feel a lack of independence. How would I get around? How would I pick my kids up from daycare, go to the grocery store, or go to work? We want to help clients address those things to alleviate some of that worry and help them get their independence back or give them independence.

A study in 2013 found that driving is the most meaningful IADL for 27 out of 30 individuals with a stroke and caregivers. The Bureau of Transportation reports that 25.5 million Americans have disabilities that make traveling difficult outside the home. Of that 25.5 million, 3.6 million Americans do not leave their home because of their disability. So we have millions of Americans that are not leaving their home because of transportation difficulties.

The Bureau of Transportation also reports that personal vehicles are used most widely regardless of disability. Despite having public transportation, the primary mode of travel is by private cars. However, people without a disability use them more often.

Driving is a meaningful occupation from 16 to upwards of 80 to 90 years old or older, so we can address it across someone's entire lifespan.

Driving Rehabilitation

- What is driver rehabilitation?

- Recovering from medical conditions

- Drivers with progressive diseases

- Novice drivers who need specialized equipment and/or learning

- Community mobility

What is driver rehabilitation? That is what I do. I work to help clients who are recovering from an amputation, stroke, rotator cuff injury, brain injury, neck surgeries, and so on return to driving. Driver rehabilitation could be for any type of acquired medical condition, progressive disease, or someone needing specialized equipment and learning to drive. Progressive diseases could be multiple sclerosis, dementia, muscular dystrophy, etc., where we want to monitor their cognitive and functional status.

We also want to think about community mobility. Driving may not be an option for someone, but we can still help the client with community mobility, help them to develop a transportation plan, or help them acquire transport.

- Occupational Therapy

- Driving and community mobility are IADLs.

- Evaluate for functional ability essential to driving

- Recommend modifications to vehicles

- Provide intervention

Where does occupational therapy fall into this? Driving and community mobility are IADLs that the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA) supports. We have the perfect skillset to be able to address this for people. As part of our OT evaluation, we can evaluate for functional ability essential to driving. We can also provide recommendations for vehicles, similar to how we provide recommendations for adaptive equipment. Lastly, we can provide intervention. Perhaps someone has lost part of their eyesight from a stroke or cancer. We can give them strategies to be able to drive as well.

AOTA: American Occupational Therapy Association

- Driving and community mobility statement from AOTA

- Occupational Therapy Practice Guidelines for Driving and Community Mobility for Older Adults

- AOTA.com

The American Occupational Therapy Association has released a driving and community mobility statement on its website. They have made a significant push in the last few years and released some educational videos about OT's role in driving. So we are supported by our national organization to address driving.

ADED: The Association for Driver Rehabilitation Specialists

- Dedicated to driving rehabilitation

- Network of professionals

- Practice guidelines for the delivery of driver rehabilitation services

- Code of ethics

- https://www.aded.net

Another group I am part of is The Association for Driver Rehabilitation Specialists (ADED). They are dedicated to driving rehabilitation and are a network of professionals. This group is not only OTs but also includes people in the community providing driving services.

The ADED has developed practice guidelines for the delivery of driver rehabilitation, and there is a code of ethics that you must follow. It also provides you with a certification, and I am a Certified Driving Rehabilitation Specialist (CDRS) through this organization.

OT Driver Rehabilitation Program

- Program Objectives:

- Assist clients who are novice drivers with medical issues learn to drive

- Assist clients to meet their goal to resume community mobility after a medical issue

- Driving with adaptive equipment and/or vehicle modifications

- Assist clients with progressive medical conditions to determine when is the appropriate time to stop driving and develop an individualized transportation plan

An OT Driver Rehabilitation Program has many objectives. One is to assist novice drivers with medical issues in learning to drive. They could be 16, 17, or 18 years old and have never driven. They could have autism, cerebral palsy, spina bifida, or muscular dystrophy.

We can also assist clients to resume community mobility after a medical issue. For example, this could be someone who has paralysis after an accident and needs adaptive equipment to drive.

For those progressive medical conditions, we can help them to determine when it is appropriate to stop driving. We can help them develop a plan to keep them driving by using adaptive equipment, but then also, down the road, we can have a conversation with them to stop when unsafe.

Services Provided With OT Driver Rehabilitation Program

- Clinic assessment of cognitive, visual, perceptual, behavioral, and physical limitations

- Integration of the clinical finding with an assessment of on-road performance

- Client must have a driver's license or permit for on-road assessment

- Advise client and caregivers about evaluation results and provide resources, education, and/or intervention plan

We perform an in-clinic assessment of the cognitive, visual, perceptual, behavioral, and physical limitations someone may have related to driving. We then integrate those clinical findings into the on-road performance.

We try out different adaptive equipment and see how they drive. For safety, we use a break on the car's passenger side. All clients need to have a driver's license or permit.

After the in-car assessment, we can advise the client and caregivers about the results and provide resources and education. We can develop a plan from there.

- Interventions may include training with compensatory strategies, vehicle adaptation, and safety procedures.

- Prescribe equipment, assist with BMV requirements, and collaborate with mobility equipment dealers

- Complete education for novice drivers and their parents/caregivers to address home programs

- Present resources and options for continued community mobility if recommending driving cessation

Interventions include compensatory training strategies and vehicle modification. For example, limited vision is easy to compensate for by using different scanning techniques or additional mirrors. There is also a lot of safety equipment on new vehicles like the blind spot detection system, backup cameras, et cetera. We can also use some of these visual modifications to increase the attention of some of our younger clients. We can also help them develop compensatory strategies for anxiety, as it is a significant factor for someone to be successful with driving.

We also have some unique strategies that we can provide. We can train them on pieces of equipment or write them a letter so that they can take to get their vehicle modified. We also assist with the BMV requirements, which may differ in each state. You must know what your state laws are regarding driving with adaptive equipment so that your clients follow all the laws and rules of the road. We also collaborate with mobility equipment dealers to prescribe equipment and modify the vehicles, which I will touch on later.

Additionally, we provide education for novice drivers and caregivers via home programs. If someone is going to drive with their caregivers at home, we may give them home programs and things they can do from the passenger seat. We will also present resources and options for continued mobility in the community, even if we recommend driving cessation. I want to point out that we are not in the business of taking keys away from people.

This presentation is mainly on adaptive equipment. Our recommendations go to the physician, and the physician can make the final say.

Driving and Community Mobility Team

- Physician

- Manages referral pathway

- Occupational Therapist Generalist

- Determine who is not at an elevated risk for unsafe driving, who should cease to drive until functional performance has improved, and who needs further evaluation by a specialist (Dickerson et al., 2011)

- Physical Therapist

- Maximize mobility to meet the demands of the community environment

- Speech Therapist

- Optimize cognitive function (Pomidor, 2015)

Speaking of physicians, they are part of the driving and community mobility teams. The physician is going to manage the pathway for us. Depending on the state you are in, you may get a referral from a physician. Perhaps, someone was in a car accident and is at fault, and the physician wants to look at their cognition. They could also make a referral as a client is ready to return to driving and work.

The other team players are the OT generalists, physical therapists, and speech therapists. Depending on the setting, you may screen and work on some of those foundational skills for someone to be able to drive.

OTs have a significant role in getting someone ready to look at driving because driving is one of the most complex IADLs we can do as it takes every part of our body. Physical therapists will maximize the client's mobility to meet the demands of the community environment and help them figure out what device they want to use in the community. They may use one device in the home, but when going to the grocery store, they may need a power wheelchair. A speech therapist will optimize their cognitive function and communication. It is essential to work with a speech therapist, especially if someone has aphasia, to ensure that what we are looking at is a language issue, not a cognitive deficit.

- Occupational Therapy Driver Rehabilitation Specialist

- Completes comprehensive driving evaluation, which includes a clinical & and a behind-the-wheel evaluation

- Mobility Equipment Dealers

- NMEDA.com

A Driver Rehabilitation Specialist will complete a comprehensive driving evaluation, including a clinical and behind-the-wheel assessment. Lastly, the mobility equipment dealers will modify the vehicles for us. While other dealers modify vehicles, I recommend that everyone uses one through NMEDA, the National Mobility Equipment Dealers Association, because they have a quality assurance program where these places are inspected every year for compliance with safety and installation of the equipment.

Driver Rehabilitation Specialist

- An occupational therapist with driver rehabilitation specialist additional training is eligible to complete the multifactor occupational therapy clinical evaluation, home program education, in-clinic occupational therapy treatment, and on-road evaluation.

As I mentioned, the Driver Rehabilitation Specialist is an occupational therapist with specialized training and is eligible to complete that clinical evaluation, the home program, the in-clinic treatment, and the on-road evaluation.

Clinical Evaluation

- Clinic assessment using evidence-based practice

- Vision

- Visual perception

- Physical ability

- Cognition

What is in this clinical evaluation? We are going to look at all the areas required to drive. The first thing we are going to do is check their vision. The next thing we are going to do is look at visual perception. How is their brain interpreting what their eyes are seeing? Vision is a huge part of driving, so we want to ensure that everything checks out. There have been quite a few studies on visual perception and increased crash risk.

We want to look at their physical ability to drive and any needed compensatory strategies. Finally, we will look at their memory, divided attention, problem-solving, and judgment required to drive.

Clinical Evaluation- Vision

- Visual Acuity

- The minimum vision for most drivers to qualify for an unrestricted license is 20/40.

- Visual Fields

- The minimum requirement for an unrestricted license is 70 degrees of side vision in each eye.

- Visual fusion

- Double vision or suppressing

- Depth Perception

For most states, the minimum vision requirement is 20 out of 40, which may vary from state to state, but this is pretty much across the board from my experience. Monocular vision may be different, but this is for binocular vision.

An unrestricted license's minimum requirement for visual fields would be 70 degrees. Our visual fields do extend past 70 degrees for normal vision.

We will also look at visual fusion and how the eyes converge for visual accommodation. We may notice that they have double vision far away. We also need to see if younger clients have strabismus or lazy eye. Typically, they suppress one eye when they are driving.

Lastly, depth perception is critical for driving.

Clinical Evaluation-Visual Perception Skills

- MVPT- version 3

- Cut off score of 30 or better as the best predictor of pass/fail on the road test. Norms may differ for age.

- MVPT was both the test with the highest positive and negative predictive values. The greatest odds of failing were predicted by those scoring 30 or less as they were 8x more likely to fail the on-road evaluation than those who scored greater than 30.

- Visual close subtest of the MVPT – those who made 4 or more errors in this subtest were 2x more likely to crash.

- Speed of visual processing

- Mean visual processing speed at 6.11 seconds in the fail group

I like to use the Motor-Free Visual Perception Test, version 3, to assess visual perception. Even though they have developed version 4, there is no research for using it for driving yet. Version 3 has a visual processing speed or timed component, whereas the new version does not. I will continue to use version 3 because that is where the most research is, and I get much information from it.

For visual perceptual skills, the driving community has found that a cutoff score of 30 or better out of 36 is the best predictor of a pass or fail for on-road tests. The Motor-Free Visual Perception Test had the highest positive and negative predictive values. The greatest odds of failing were predicted by those scoring 30 or less, as they were eight times more likely to fail an on-road evaluation than those who scored greater than 30.

I will not rule anyone out of driving based on one assessment, but this gives me a good idea of what I need to further assess for driving. There is a specific sub-test called the visual closure sub-test, and people who made four or more errors in that sub-test were twice as likely to be involved in a car crash. Again, I am getting lots of information from one test.

For speed of visual processing, they found an average visual processing speed of 6.11 in the fail group. So we try and look at six seconds or faster for this test.

Clinical Evaluation-Physical Abilities

- Reaction time

- Strength

- ROM

- Sensation

- Height

- Wheelchair measurements

- Transfers

Then, we will look at physical abilities like reaction time, strength, and spasticity. We will also look at their range of motion, sensation, and overall height for seeing over the steering wheel or reaching the pedals. If they are using a wheelchair, we will get those measurements, but we will also consider any other device they are using.

We also look at transfers and how they will get in and out of the vehicle

- Right weakness

- Unilateral steering, starting the ignition, operating gear shift, use of petals

- Left UE Weakness

- Unilateral steering, turn signal, headlights, mirror, window

- Bilateral LE weakness

- Use of hand controls

- Sensation

- Proprioception, pressure, light touch

- Height

- Shortness of stature, line of sight, physical access to controls

- Wheelchair measurements

- Body Habitus

- Physical access to controls

- Transfers

- Into and out of the vehicle

- Load and unload a wheelchair

Let's look at the specifics. If someone has right weakness due to right hemiplegia, I start thinking right away about how the client will steer with one hand, start the car because the ignition is on the right, operate the gear shift, and use the pedals because our right leg is the primary one used for driving. Today, some cars have push buttons for the ignition and the gears.

If someone comes in with left upper extremity weakness, they will steer with their left hand, but there are also turn signals, headlights, mirrors, and window controls on that same side. How are we going to operate those?

If they have bilateral lower extremity weakness, they may need hand controls to control all of their driving.

Sensation depends on the location to determine if it will affect driving. The client must feel where their legs are in space, the pedals, light touch, and pressure. So it may depend on the severity of their sensation deficits.

We also want to consider height and shortness of stature. We want their line of sight about four inches above that steering wheel to see adequately. How close do they need to be to the steering wheel or the pedals?

If someone has to drive from a seated position, we must consider their wheelchair positioning. We also need to consider body habitus. Larger folks may have trouble getting close to the steering wheel. We typically like about 10 inches between the steering wheel and the person.

Lastly, we need to assess transfers in and out of the vehicle. How are they going to do that? Are they using a slide board if they are transferring from a wheelchair? How will they load their walker in and out of the vehicle? Can they break down their scooter, or will they be driving from a power wheelchair or a manual wheelchair?

Clinical Evaluation-Cognition

- Memory

- Judgment

- Distractibility/Attention

- Trails A/B

- Problem solving

- Road sign identification

- Other areas to be observant of:

- Mental and visual endurance

- Topographical orientation

- Frustration tolerance

- Anxiety

Obviously, cognition is essential for driving. For memory and judgment, we need to remember the directions, where we are going, the speed limit sign that we pass, and make good, safe decisions. Distractability and attention are other areas to assess. I have found in my personal experience that Trails A and B will not be applicable for someone with autism, but if they are touching everything in my office while trying to do that assessment, how distracted are they going to be by a stoplight? But maybe after a stroke, Trails A and B will be applicable. We all know that a lot of construction and other random things happen on the road that requires problem-solving. They also need to be able to identify signs.

Another area to be aware of is mental and visual endurance. Younger clients are not used to using sustained concentration. Topographical orientation is another crucial aspect of driving. Again, younger clients are so used to being on their phones or having headphones on when in the vehicle they may not be sure how to get to places. What are a client's frustration tolerance and anxiety? Many have mental health issues and have low frustration tolerance and high anxiety. Anxiety can often be seen in those with traumatic brain injuries.

Red Flags for Driving

- Acute events

- Sx, hospitalization, TBI, CVA, MI

- Client or family member concerns

- Alzheimer's, Dementia

- Accidents

- Chronic medical conditions

- Diabetes, glaucoma, macular degeneration, MS

- Medical conditions w/episodic events

- Seizures, angina, syncope

- Medications

- Education of side effects, polypharmacy

One red flag would be an acute hospitalization. We would want the clients to be cleared by their doctor before driving. For example, a person could have uncontrolled diabetes and be at risk for driving.

A client or family member may have concerns that their loved one has Alzheimer's dementia. By the time someone gets lost, it is usually time to look at them retiring from driving. They may also have accidents, and caregivers see dents on their cars, or they accidentally begin to hit the garage.

Chronic medical conditions that we would want to monitor would be diabetes, as stated above, glaucoma, macular degeneration, and multiple sclerosis. Many episodic conditions can be well managed and will not be an issue long-term. There is no restriction for seizures in Ohio, but in other states, they may have to wait six months to a year.

For medications, we need to watch the side effects of certain drugs or polypharmacy.

- Review of body systems

- Integration of vision, cognition, and motor function

- Unable to isolate movements right and left and/or upper and lower bodies

- Asymmetrical bilateral coordination

- Startle Reflex

- Unmanaged spasticity

- Doesn't meet vision standards- visual acuity or visual fields

- Fatigue/Endurance

- Poor performance in multiple areas on clinical evaluation

During our assessment, we need to review the body systems and take all these visual, cognition, and motor functions together. When I am doing a physical evaluation on someone, it would also be a red flag for me if they cannot isolate their body movements. If they are using their right leg, but their arm pulls into some flexion tone, that will have me concerned about their driving. I am not sure how they will be able to steer if they also move their foot back and forth to the pedals.

One of the unique things about driving, especially with hand controls or adaptive equipment, is that asymmetrical bilateral coordination is required. An example of this is patting your head and rubbing your stomach simultaneously. Steering the wheel and operating a hand control can be difficult, and if the client has a neurological condition, that can be hard.

Sometimes a startle reflex has been the only reason a client has not been successful with driving, specifically with cerebral palsy. It can be so strong that it is not safe to drive. I had a client who, every time we would make a right turn or if she saw another car, would startle and accelerate the vehicle and turn the wheel. We could not progress out of the parking lot due to this reaction. She was a mother going to school and working, so we did try. Unmanaged spasticity can also be dangerous if clients hit bumps in their wheelchairs.

The client may not meet vision standards for your state. If so, we are not going to get them in the vehicle. I will have them go back and see their eye doctor as I cannot diagnose them. We also want to ensure that if we see someone in the morning, they present the same way in the afternoon.

A combination of poor performance in multiple areas on the clinical evaluation is another red flag. It is hard if a client has visual, cognitive, and physical deficits and is trying to learn how to drive.

When assessing driving, we want them only to have one area that we are addressing, like physical limitations or visual deficits.

Driver Readiness

- Promote maximum independence while balancing safety needs for those clients who are trying to decide if learning how to drive is feasible and safe.

- Suitable Candidates:

- Novice drivers with diagnoses that may negatively impact their ability to learn to drive with a traditional method, i.e., community-based driver's education instruction.

- Common diagnosis

- Autism spectrum disorder

- Attention deficit disorder

- Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

- Learning disability

- Any diagnosis that results in a physical impairment that limits a client's ability to operate a vehicle with OME primary and secondary controls would also be an appropriate candidate.

We can also prepare individuals to get ready to drive or think about driving.

- Two types:

- Basic (prior to driving)

- Advanced (in car)

- Must be able to:

- Take in, remember, and follow route instructions

- Topographical orientation, wayfinding

- Detect, identify, and react to critical objects

- When to start?

- As young as toddlers

There are two basic types: basic before driving activities and advanced in-car training.

If someone is ready to drive, they must be able to take in, remember, and follow multi-step directions. Topographical orientation and wayfinding are also crucial skills. They also have to be able to detect, identify, and react to critical objects.

I recommend people look at driver readiness as soon as possible. Even young children can practice multi-step directions and wayfinding. I tell my daughter, "Go into your bedroom, get your Elsa doll, and come back." We can also look at someone with a brain injury and start with directions and wayfinding.

Driver Readiness Interventions

- Commentary training

- Exposure

- Using navigation

- Giving directions

- Riding a lawn mower

- Old-time cars at Kings Island, Cedar Point, Six Flags

- Go carts

- Wayfinding

- School, mall, going on walks

- Scavenger Hunt

Here are some of the things that we like to do. Commentary training is something they can do from the passenger seat. Someone drives them around while they call out speed limit signs, traffic lights, and oncoming traffic. They will tell you which lane to get into and to put your turn signal on. If there is construction, they will let you know that you need to change lanes or what exit ramp to use. You can divide this up into three phases. The first phase would be that the driver, the parent, or myself, would talk about everything they are seeing and doing. In the second phase, the client is still in the passenger seat, talking and identifying all those hazards and critical information. The third phase is that client is now in the driver's seat, but they are still speaking out loud. Talking out loud helps us develop a way to communicate in the vehicle. Still, it lets me see if they are not correctly identifying critical information so I can intervene.

Exposure, as I mentioned, is using navigation, giving directions, and looking for other opportunities to explore driving, like a lawn mower, old-time amusement cars, go-carts, or golf carts at friends' houses. They can also do wayfinding at school, the mall, on walks, or during scavenger hunts.

Common Issues Learning to Drive with a Physical or Cognitive Impairment

- New drivers with functional limitations are starting with a disadvantage.

- Overwhelmed by the speed that decisions must be made

- Limited experience

- Must learn gap analysis from scratch

- Often require adaptive equipment and practicing with parents is not possible even with a learners permit

New drivers with physical or cognitive limitations start with disadvantages. They can be overwhelmed by the speed at which decisions must be made and have limited experience. The only experience that they may have had is how fast their wheelchair goes.

They are also learning "gap analysis" from scratch, the distance between two cars when you are attempting a left turn. They have never had to make those decisions or seen that before. Many times these clients have been in the back of the van or bus and have not experienced the front passenger seat.

Possible Adaptive Equipment

I am now going to go over adaptive equipment that I like to recommend. I will start with overarching adaptive equipment and then move on to specifics.

Lowered Floor Minivan

- Transportation

- Keeps back seats of the vehicle

- Able to drive from power wheelchair or manual wheelchair depending on height

- Can drive from a power transfer seat

The first one I want to look at would be a lowered floor minivan as it is excellent for transportation, and someone may be able to drive from this. Folding Ramp Vs. In-floor Ramp

- In-floor Ramp

- Pros preserve interior room, quiet, allows for taller door opening

- Cons: can be costly to maintain

- Folding Ramp

- Pros: cheaper, lower incline, easier for maintenance

- Cons: noisy and takes up space on the interior

A folding ramp also keeps the back seats of the vehicle, which is nice. There are also some other vans where the ramp is in the car's rear, but then it takes out three seats.

They can also drive from a power transfer seat base. If someone is in a wheelchair, the driver's seat will back out and turn, and they can transfer into it. If the driver's seat is removed, a person can then maneuver their power wheelchair into the driver's bay and be able to drive from the power chair. This option is probably one of the most common, even for someone using a scooter.

An in-floor ramp is nice because it keeps people out of the elements. Many vehicles have self-start and can be defrosted before getting in them. This is especially needed for those with physical disabilities who have difficulty scraping off the ice.

Figure 1 shows a folding ramp.

Figure 1. An example of a folding ramp.

If it did not fold out, it would block the entrance. If you use this door, you need to deploy the ramp and use this type of parking space.

The pros of a folding ramp are that it is cheaper, has a lower incline, and is easier maintenance. As you have physical access to it, it is easy to provide maintenance. The battery is also easy to fix. The cons are that it is noisy and takes up space in the interior.

An in-floor ramp, which I do not have a picture of today, slides underneath the vehicle's floor and is not observable when in the van. It is quiet and does not block the door. However, they can be more expensive and need more maintenance as it is on the bottom of the car and exposed to rain, snow, and salt. The in-floor ramp can also allow for a taller door opening. This is needed for some of my clients as they are very tall in their power wheelchairs.

Wheelchair Securement

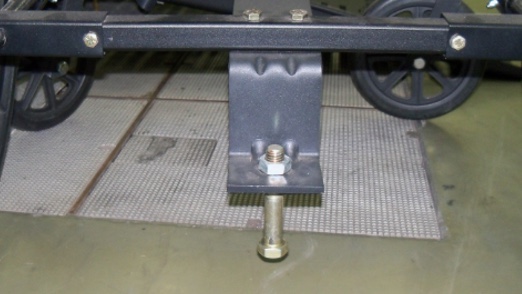

The next area is wheelchair securement. Many clients get an easy lockdown system, and an EZ Lock pin is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. EZ Lock system.

The EZ Lock system is bolted to either the power or manual chair's bottom. The EZ Lock website is impressive and tells you every compatible wheelchair. Dealers install this system. In Figure 2, you can see the box forms a triangle where the pin, in Figure 3, slides in and then locks.

Figure 3. Pin for the EZ Lock system.

The wheelchair is then secured to the vehicle, and they will still have a seatbelt mounted to the floor. When secure, the wheelchair is now a part of that vehicle. When I train clients, they do not always have this system yet, so we use retractable tie-downs and attach them to their chairs (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Tie-downs for the wheelchair.

There is usually a button that they can release the EZ Lock system and back out of the driver's bay. One thing to consider is that if they have a manual folding frame chair, this modification will make their chair rigid, and they will not be able to fold anymore.

Power Transfer Seat Base

- Safer option vs. driving from a wheelchair

- Able to transfer out of the elements

Figure 5 is the power transfer seat base that I mentioned earlier. This client was able to push up their manual wheelchair up the side ramp and then transfer into the driver's seat. As you can see, the transfer seat slides back into the main cabin, turning slightly so they can move directly into the seat.

Figure 5. Example of a power transfer seat base.

He has a C6 spinal cord injury, so he used a box for extra support. He was able to transfer into that driver's seat but did not want to drive from his manual chair because the back was too low. He felt more secure with this setup.

Trunk Mobility Solutions

- Safer option vs. driving from a wheelchair

- Able to transfer out of the elements

Here are some truck mobility solutions. I have people that insist on driving trucks. My first car was a truck, so I understand. With this crane, as seen in Figure 6, they can hook up their chair once they have transferred. It will lift it and put it in the back of the truck.

Figure 6. Lift for a wheelchair.

They also make toppers that can cover this as well. Not everyone wants the topper for aesthetics, and the topper is not compatible with power wheelchairs. This client had incomplete quadriparesis but still drove with hand controls and used a manual chair.

Knobs

As you can see in Figure 7, there are multiple mounting brackets, so we can find the most optimal position when we are training. I have another on the bottom, but it got cut off in the picture.

Figure 7. Examples of mounting brackets on a steering wheel.

Mounting brackets provide a means to add different equipment for individuals to drive with one hand and fully control the vehicle. In Ohio, it is illegal to drive with a knob unless you are licensed with it. Even if we think that is the only adaptive equipment they need, they still need to retake their driver's test. Knobs and tri-pins are good options if the client has full shoulder range of motion.

Bluetooth Knobs

Bluetooth knobs are shown in Figure 8. These are cool because this device lets you do your turn signals, windshield wipers, and horn.

Figure 8. Examples of Bluetooth knobs.

There are multiple different varieties out there. This may be useful for someone with an amputation who cannot use a button anywhere else.

Turn Signal Cross Over

- Moves turn signal from left side of the steering column to the right.

- Good for stroke, CP, or amputation where client does not have good use of left UE

We also have the turn signal cross over, a cheaper alternative to the Bluetooth knob. It moves the turn signal from the left side of the steering to the right of the steering and vice versa.

Hand Controls

- Can be electric or mechanical

- Good for any diagnosis that does not have good use of bilateral lower extremities but has intact upper extremities

- SCI

- MS

- Amputation

- Spina Bifida

- Diabetic neuropathy

Hand controls can be electric or mechanical and are suitable for any diagnosis that does not have good use of bilateral lower extremities but has intact upper extremities.

Figure 9. Examples of hand controls.

Clients do not have to have full strength. The device on the left is a push/rock hand control. It rocks down towards you for an accelerator and pushes away for the brake. It is set up this way 95% of the time because the momentum will carry you onto the break. We do not want to fight physics and pull back to break.

I have used this for clients with spina bifida, multiple sclerosis, spinal cord injury, and even diabetic neuropathy due to poor sensation in their legs. They could be ambulatory, but not safe for them to drive. We always have them drive with a knob as well. Many clients want to try without the knob, but then they find that they usually need it to turn safely.

Left Foot Accelerator

- Mechanical

- Pedal Block over OEM accelerator

- Difficult to share vehicle

- Electronic

- When on, OEM accelerator is disabled

- More expensive, easily able to share vehicle

- Diagnosis

- CP

- Stroke

- Amputation

- Orthopedic injury

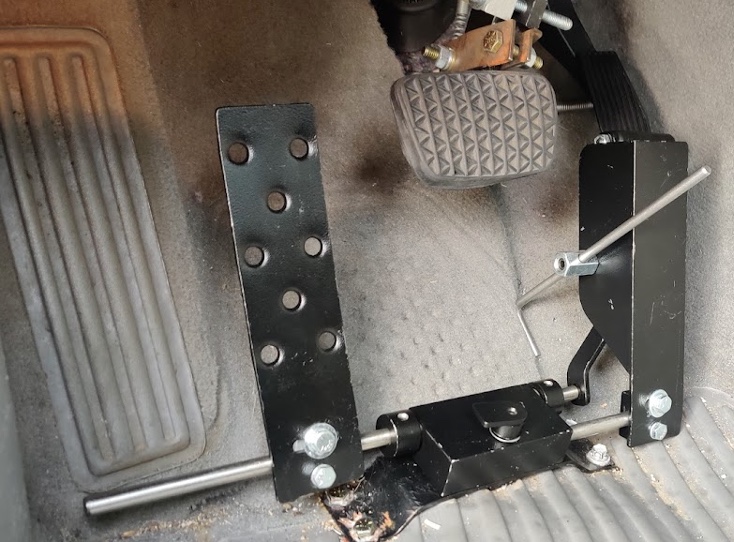

Something else that we prescribe is a left foot accelerator, as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10. Example of a left foot accelerator.

If someone had a stroke with resultant right hemiparesis or right leg amputation, we could move the left foot accelerator to the other side of the brake. There are challenges with this because our brain has been wired where the brake and accelerator are. There can be a lot of gas and brake confusion driving with your left leg. This might be okay for someone who has never driven before. We use this if it is the only option, but it can take a lot of time to rewire the brain for emergency procedures so that you hit the brake and not the gas pedal.

This is a mechanical one and uses a pedal block. There are electronic versions as well. They are nice because they look like a standard pedal but can be turned on and off. So if someone wants to share a vehicle, you can turn off the left foot accelerator and turn on the right.

Pedal Extensions

We can also help with pedal extensions.

Figure 11. Example of pedal extensions.

Shorter statures can get about six inches of extension on these pedals.

High Tech Driving

- When other adaptive equipment options are not appropriate

- Most commonly driving from a power wheelchair

- Rehabilitation Engineer

- Diagnosis commonly seen

- MD

- SMA

- Arthrogryposis

- Multiple amputations

- Cervical Level Spinal Cord Injury

One of the more unique things I would say is what we call high tech driving. This setup is typically used for people driving from a power wheelchair, but not all. I work with a rehabilitation engineer to help set up the vehicle and equipment. This is commonly used for those with muscular dystrophy, SMA, arthrogryposis, multiple amputations (maybe more than two, or involving upper and lower extremities), and cervical level spinal cord injuries.

Input Devices Commonly Used for High Tech Driving

- Low force joystick

- Single joystick

- gas, brake, and steering

- Two Joysticks

- separated into steering and gas/brake

- Good for low strength, decreased ROM

- Requires good FMC

- Commonly used for SMA and MD

- Single joystick

These are two joysticks in Figure 12.

Figure 12. Example one of a high tech setup.

The left is for the gas and brake, where you push forward to brake and pull back to accelerate. The right is doing the steering, and the turn signals are controlled through this little blue button. Their gear shift is a touch screen, so you can even see a tiny key showing park, reverse, and drive. So they will hold the brake on their joystick and put the car into gear. This is good for someone with low strength and decreased range of motion but good fine motor coordination.

And so, we typically use this the most for someone with SMA or muscular dystrophy.

- Microwheel and Gas brake slider

- Micro wheel for steering

- Tri pin attachment or other steering device

- Gas Brake slider

- Push/pull for acceleration and braking

- Tri pin or other attachments for securement

- Proximal control is better than distal control. Does not need to have good FMC.

- Commonly used for cervical level spinal cord injury

- Micro wheel for steering

Some other input devices widely used for high-tech driving are a micro wheel and a gas/brake slider, as shown in Figure 13. There is a micro wheel and tri pin.

Figure 13. Example of a micro wheel and tri pin.

We can also mount those to the steering wheel. There is also a gas/brake slider where you push forward to brake and pull back for gas. You can see that this client is driving from their power wheelchair, and that we have added a chest strap for proximal stability.

Case Studies

Case Study 1

- Caroline is 16 years old and has mild cerebral palsy that causes left hemiplegia. You have never noticed a startle reflex, and she performs average in school.

- She is having trouble learning to drive with her parents because she feels that her left arm gets in the way.

- Which adaptive equipment options would be best for her?

- Answer:

- A knob

- Would like to see if she could use her left UE to operate turn signal.

- Other considerations could be a turn signal cross over or secondary switches on the knob.

- Not concerned about gas/brake functions as right side of body is intact.

- A knob

Which adaptive equipment options would be best for her? The answer would be a knob. We would also like to see if she could use her left upper extremity to operate the turn signal. We could also consider a signal crossover or Bluetooth switches on the knob. We are not concerned about the gas/brake function, as the right side of the body is intact, and there is no startle reflex.

Case Study 2

- Evan is 17 years old and would like to get her driver's license. She was born with spina bifida and does not have good coordination with her legs, but she does have some movement.

- Which adaptive equipment options would be best for her?

- Answer:

- Hand Controls with a knob

- Considerations: Anticipate that she has good upper body strength due to SB affecting only her lower body.

- Hand Controls with a knob

The answer for this case study would be hand controls with a knob. She has good upper body strength due to the spina bifida only affecting her lower body. Things to also think about are hydrocephalus, and a shunt as a malfunction can cause visual perceptual deficits.

Case Study 3

- Josh is 17 years old and has SMA. He uses a power wheelchair for all his mobility and cannot lift his arms over his head due to weakness. He requires total assistance for all his transfers and most of his ADLs. Vocational rehabilitation is working with him to get him an online sales job that will be mostly computer based.

- Which adaptive equipment options would be best for him?

- Answer:

- High Tech Driving Equipment

- Considerations: drives from wheelchair, weakness, progressive disease, good FMC

- Possible trial with two low force joysticks

- High Tech Driving Equipment

This case study requires high tech driving options. As he has a progressive disease but good fine motor coordination, we would want to trial low force joysticks.

Vehicle Modification

- NMEDA: National Mobility Equipment Dealers Association

I mentioned this earlier. You would want to complete modifications through an NMEDA dealer.

Funding

- Local state vocational rehabilitation programs

- Automobile rebate programs

- Grant programs:

- National organization for vehicle accessibility

- CHIVE Charities- targets rare medical diagnosis

- Medicaid Passport

- Mobility Works

There is funding via local and state vocational rehabilitation programs. I would say those are probably the primary funders for vehicles. If a client has to be able to drive to and from work, that will be a significant factor for funding. There are also automobile rebate programs. For example, if you buy a new Honda, you can typically get a rebate for putting adaptive equipment on it.

There are also grant programs for vehicle accessibility and the CHIVE charity through national organizations. I just had a client receive a CHIVE grant. It targets those with rare medical diagnoses. They paid for the entire van for this client, and vocational rehab is paying for the adaptive equipment.

In Ohio, Medicaid Passport will pick up vehicle modifications. Check out Medicaid programs in your state. MobilityWorks is a national NMEDA dealer that modifies vehicles. On their website, they have an entire funding option where it lists the most recent grants and rebates for all of the products.

My Client Wants to Drive

- When to refer?

- How is my client doing with other complex IADLs?

- Is the client motivated to drive?

- Refer to spectrum of driver services worksheet from AOTA

- OT-PAD

- Driving Pathways from AOTA

Your client wants to drive. When should you refer? The first question is, how are they doing with other IADLs? Are they motivated to drive? Driving pathways from AOTA is another great resource.

How to Find a Driving Rehabilitation Specialist

- Go to ADED.net to find a DRS/CDRS locally

- CDRS has taken a certification exam to demonstrate their knowledge (like that of an ATP).

To find a driving rehabilitation specialist, you can go to aded.net to find a local DRS or CDRS. The CDRS is someone who has taken the certification exam in this area.

Questions and Answers

How long does it take to get certified for driver's rehab? How much coursework?

It depends. There are four different pathways to get certified in driver's rehab to get the CDRS credential. On the ADED website, they do specifically answer that question. .

Can you get insurance to cover the driving eval?

I had several clients in the past that could have benefited but were unable because it was an out-of-pocket expense, and they could not afford it. We do bill an OT eval for that part. Not all insurances will cover the on-road part, depending on how they would like to bill it. We specifically bill self-care because it covers the adaptive equipment training, but most government payers will not cover the in-car.

What are tri pins?

Tri pin is a three pin handle. One pin goes in the palm, and the other two pins are on either side that support the wrist. It is very secure, and they can steer and control the vehicle well.

Would you recommend that clients with autism spectrum disorder be referred to CDRS for driving evaluation, even if showing competency with other IADLs due to the specific nature and skillset needed for driving?

This is a fascinating question and is relevant to what we are doing in my current program. I think it would be beneficial. The driving community is doing a lot of research on driving with autism, so some of the assessments that we look at are not finding the deficits that may be causing them to have difficulties learning to drive. If they are at an average IQ, there would be no reason why they could not try a typical driving route. However, if they are struggling, I think it would be beneficial to see a CDRS and get that evaluation done.

My daughter has Turner syndrome and will need pedal extensions, a cushion, or something to lift her high enough to sit above the steering wheel. What do you recommend to lift her seat height, and what resources are available to cover these adaptive equipment options, or will health insurance cover any of these?

In my state, the seat modification is not a restriction that would flag at the BMV, but the pedal extensions would. You would want to make sure that you check with your local BMV on what would be needed for that. Medical insurance typically does not cover any adaptive equipment modifications for the car, but you could look at vocational rehab in your area. You often only need a part-time job for a few hours a week to qualify for vocational rehab.

How long does it typically take for someone going through the training to become either applicable for getting a license to drive with modifications or determine they will not be able to pass what needs for driving?

Someone who has never driven before and has virtually no experience with driving could need about 30 to 50 hours of driving. I have done it in maybe 20 hours for someone with absolutely no experience. If someone already has experience with driving, I have done training in as little as two sessions. I completed an evaluation, we trained, and then I took them to test at the BMV. This person also grew up on a farm and was already driving different equipment with hand controls. There is a variety and a range. If someone does not make progress in the first four sessions, I typically know at that point that this is not going to be a good option for them.

Thanks for listening.

References

Ball, K. K., Roenker, D. L., Wadley, V. G., Edwards, J. D., Roth, D. L., McGwin, G., Jr, Raleigh, R., Joyce, J. J., Cissell, G. M., & Dube, T. (2006). Can high-risk older drivers be identified through performance-based measures in a Department of Motor Vehicles setting? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 54(1), 77–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00568.x

Betz, M. E., Jones, V. C., & Lowenstein, S. R. (2014). Physicians and advance planning for 'driving retirement'. The American journal of medicine, 127(8), 689–690. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.03.025

Devos, H., Akinwuntan, A. E., Nieuwboer, A., Truijen, S., Tant, M., & De Weerdt, W. (2011). Screening for fitness to drive after stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurology, 76(8):747-56. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31820d6300. PMID: 21339502.

Dickerson, A. E., Reistetter, T., Davis, E. S., & Monahan, M. (2011). Evaluating driving as a valued instrumental activity of daily living. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 65(1), 64-75.

Dickerson, A. E., Reistetter, T., & Gaudy, J. R. The perception of meaningfulness and performance of instrumental activities of daily living from the perspectives of the medically at-risk older adults and their caregivers. J Appl Gerontol., 32(6):749- 64. doi: 10.1177/0733464811432455. Epub 2012 Mar 22. PMID: 25474797.

Di Stefano, M., Stuckey, R., Kinsman, N. (2019). Understanding characteristics and experiences of drivers using vehicle modifications. Am J Occup Ther., 73(1):7301205050p1-7301205050p9. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2019.023721. PMID: 30839260.

Di Stefano, M., Stuckey, R., Kinsman, N., & Lavender, K. (2019). Vehicle modification prescription: Australian Occupational Therapy Consensus-Based Guidelines. Am J Occup Ther., 73(2):7302205140p1-7302205140p10. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2019.024331. PMID: 30915975.

Fields, S. M., Unsworth, C. A. (2017). Revision of the competency standards for occupational therapy driver assessors: An overview of the evidence for the inclusion of cognitive and perceptual assessments within fitness-to-drive evaluations. Aust Occup Ther J., 64(4):328-339. doi: 10.1111/1440-1630.12379. Epub 2017 May 19. PMID: 28524365.

Holowaychuk, A., Parrott, Y., Leung, A. W. S. (2020). Exploring the predictive ability of the Motor-Free Visual Perception Test (MVPT) and Trail Making Test (TMT) for on-road driving performance. Am J Occup Ther., 74(5):7405205070p1-7405205070p8. doi: 10.5014/ajot.119.040626. PMID: 32804625.

Hutchinson, C., Berndt, A., Cleland, J., Gilbert-Hunt, S., George, S., & Ratcliffe, J. (2020). Using social return on investment analysis to calculate the social impact of modified vehicles for people with disability. Aust Occup Ther J., 67(3):250-259. doi: 10.1111/1440- 1630.12648. Epub 2020 Feb 4. PMID: 32017155; PMCID: PMC7317535.

Mazwer, B, Kroner-Bitensky, N., & Sofer S. (1998). Predicting ability to drive after a stroke. Archives of physical medicine.

Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process—Fourth Edition. (2020). Am J Occup Ther, 74(Supplement_2):7412410010. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2020.74S2001

Pomidor, A. (Ed.) (2015). Clinician's guide to assessing and counseling older drivers, 3rd Edition. New York: The American Geriatrics Society.

Selander H, Lee HC, Johansson K, Falkmer T. (2011). Older drivers: On-road and off-road test results. Accid Anal Prev, 43(4):1348-54. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2011.02.007. Epub 2011 Mar 5. PMID: 21545864.

Stav, W. B., Arbesman, M., & Lieberman, D. (2008). Background and methodology of the older driver evidence-based systematic literature review. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 62(2), 130-135.

Citation

Fisher, M.(2022). Occupational therapy for driving and adaptive equipment. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5532. Available at www.occupationaltherapy.com