Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Pelvic Muscle Dysfunction And Continence Improvement: A Primer For Occupational Therapy, presented by Kathleen Weissberg, OTD, OTR/L.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to identify urinary incontinence (UI) treatment guidelines, the direct impact of UI on occupations of the elderly population, and describe normal bladder and pelvic muscle function.

- After this course, participants will be able to recognize the pathophysiology of transient (acute) and established (chronic) urinary incontinence.

- After this course, participants will be able to list occupation-based assessment and management strategies for various types of incontinence, including effective behavioral treatment strategies, and state how to set up and facilitate a Multi-disciplinary Team Continence Improvement Program.

Introduction

Thank you for joining us today. I'll begin with an overview of the topic, and then we'll address some important considerations and regulatory aspects. In this session, we will be discussing continence and incontinence from various perspectives.

Let's first consider the perspective of the patient or resident you may be working with, whether it's in a home care setting, outpatient situation, or skilled nursing facility. Imagine you are at home and experiencing urinary incontinence issues. Your family believes the problem is worsening and suggests you move into a skilled nursing facility for better care. Upon arrival, you face challenges, such as wetting or soiling yourself, leading to social isolation and a decline in your usual sociable behavior.

Next, let's explore the regulatory perspective. If you are involved in areas like estate surveying or Medicare, you may be looking for ways to reduce healthcare costs. It's important to understand the financial burden that urinary incontinence places on the healthcare system. This raises questions about why guidelines are not being strictly followed and why more proactive measures are not being taken.

As someone working in a skilled nursing facility for an extensive period, you may be concerned about the number of residents experiencing urinary incontinence and the associated costs. You wonder if there are ways to improve the situation and provide better care.

Finally, let's consider the perspective of us, the clinicians, such as occupational therapists. While specialized biofeedback training is not a requirement, it's essential to acknowledge that we can still make a difference in addressing urinary incontinence. This session aims to serve as a primer and help you realize that there are actionable steps we can take to improve the quality of life for those dealing with this condition.

Bowel incontinence is indeed a separate and important topic that we can address in the future, but for now, let's concentrate on urinary incontinence and the specific issues related to it. By narrowing our focus, we can delve deeper into understanding and managing this particular concern effectively. Let's proceed with our discussion on urinary incontinence and explore the various perspectives and solutions within this scope.

Scope of the Problem

Let's now delve into the scope of the problems related to urinary incontinence.

Statistics

- Over 25 million adult Americans experience temporary or chronic urinary incontinence.

- This condition can occur at any age, but it is more common in women over the age of 50.

- Prevalence

- Women – 61%

- Men – 3-10%

The current statistics reveal that more than 25 million American adults are affected by temporary or chronic urinary incontinence. While this condition can occur at any age, it is more prevalent in women, especially those over the age of 50 and those who have experienced pregnancy or vaginal delivery. In women, the prevalence of urinary incontinence is approximately 61%, while in men, it ranges from 3% to 10%. However, it's important to note that the actual rates for men might be higher, as they tend to be less open about discussing these issues, leading to potential underreporting.

Comparing these figures to past estimates, we can observe a significant increase in the reported numbers. Previous estimates ranged from 38% to 49%, suggesting that within the last five to ten years, there has been a dramatic rise in the prevalence of urinary incontinence.

This data underscores the importance of addressing this concern from multiple perspectives, considering the impact on individuals, the healthcare system, and skilled nursing facilities.

Risk Factors

- Population aging

- Greater than 70 years

- Obesity prevalence

- Body mass index >40

- Vaginal birth

- Smoking

Understanding the risk factors associated with urinary incontinence is crucial in developing effective interventions. One significant risk factor is population aging. While urinary incontinence is more commonly observed as people age, it is essential to emphasize that it is not a normal part of the aging process. However, the risk of urinary incontinence does increase with age, particularly after the age of 70.

Another risk factor is obesity, with individuals having a body mass index (BMI) greater than 40 being at a higher risk of developing urinary incontinence. Interestingly, overweight women are also more prone to incontinence compared to those with an ideal body weight. Research has shown that weight loss in significantly overweight women with incontinence can reduce episodes of unwanted urine loss.

Vaginal birth is another significant risk factor, having a strong association with urinary incontinence, particularly in women. Additionally, smoking is known to be a contributing factor as tobacco smoking can cause chronic coughing. For individuals, especially those with stress urinary incontinence, who also smoke, the recurrent downward pressure on the bladder during coughing can exacerbate leakage. Therefore, smoking cessation is recommended as a first-line approach to reduce or eliminate some of these stress urinary episodes.

Statistics, Cont.

- Urinary incontinence has been estimated to affect between 50% and 65% of nursing home residents.

- At least 11% report UI at admission to hospital, and 23% at discharge.

- At least 3 million are affected by fecal incontinence and/or defecation problems.

- Denial is common.

Additional statistics shed further light on the impact of urinary incontinence in various healthcare settings. In nursing homes, the prevalence of urinary incontinence is estimated to affect anywhere between 50% to 65% of residents, with some facilities reporting even higher rates depending on their approach to managing the issue.

Interestingly, 11% of individuals report experiencing urinary incontinence upon admission to the hospital, and this figure increases to 23% at the time of discharge. Additionally, studies have revealed that some individuals entering nursing homes without any chronic cognitive disorders, such as dementia or Parkinson's, and who are initially functional, independent, and continent may develop dependency and urinary incontinence within six months to a year, seemingly without any underlying disease process triggering these changes.

Several factors contribute to this phenomenon. In hospitals, catheter use, immobility, medication interactions, and poor staffing may play a role in the development of urinary incontinence. Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are also prevalent in hospitals and can contribute to or worsen incontinence.

Regrettably, some patients may refrain from speaking up about their incontinence issues due to various reasons, including fear of being placed into a nursing home by their families. This fear is not unfounded, as incontinence is indeed a key factor considered in determining the need for nursing home placement. Moreover, the issue may be magnified in skilled nursing facilities, leading some individuals to remain silent about their challenges with urinary incontinence.

Tag F690

- Providers are responsible for ensuring that a resident who is continent of bladder and bowel on admission receives services and assistance to maintain continence unless his/her clinical condition is/becomes such that it is no longer possible to maintain continence.

- Urinary incontinence is not a normal part of aging.

When discussing nursing homes, it's important to highlight Tag F690, a significant guideline in state surveys that industry professionals are well-acquainted with. This tag emphasizes the responsibility of providers to ensure that residents admitted with bladder and bowel incontinence receive the necessary services and assistance to maintain continence, except when their clinical condition makes it impossible. Conditions such as dementia or Alzheimer's may be relevant factors to consider in such cases. Despite the fact that the prevalence of urinary incontinence increases with age, it is crucial to acknowledge that it is not a normal part of the aging process. Unfortunately, there is often a lack of awareness and education surrounding this issue, something that occupational therapy practitioners can play a pivotal role in addressing.

- A resident who is admitted with an indwelling catheter or subsequently receives one is assessed for removal of the catheter as soon as possible unless the resident’s clinical condition necessitates continued catheterization.

- A resident who is incontinent of bladder receives appropriate care and services to prevent urinary tract infections (UTIs) and, to the extent possible, restore continence.

When a resident is affected by urinary incontinence, the facility is required to provide services based on a comprehensive assessment. This assessment involves various healthcare professionals, each playing a specific role in addressing the resident's needs.

According to guidelines, if a resident is admitted with an indwelling catheter or later receives one, the facility must assess its removal as soon as possible unless there is a valid medical justification for its continued use. The goal is to ensure appropriate care and services for residents with urinary incontinence, aiming to prevent urinary tract infections (UTIs) and, where possible, restore continence, which is a reasonable expectation following a UTI. The regulatory intent related to indwelling catheters is to ensure that they are not used unless medically justified and that they are discontinued as soon as clinically warranted.

Throughout my extensive experience in this industry, I have encountered instances where residents were equipped with catheters when they may not have needed them, possibly for reasons unrelated to medical necessity. This highlights the importance of a thorough and diligent assessment process involving nursing, physicians, occupational therapists, physical therapists, and other healthcare professionals. Together, they collaborate to develop individualized care plans to address the unique needs of residents with urinary incontinence, promoting optimal care and outcomes.

Incontinence

- “Urinary incontinence is not normal.”

- 80% of cases see improvement without surgery

- Of skilled nursing

- 80% of them could have been toileted

Urinary incontinence is not a normal condition, and research has demonstrated that approximately 80% of cases can be improved through behavioral interventions. In this discussion, we will explore various approaches to address urinary incontinence, including staff collaboration, medication management, behavioral strategies, and exercises like Kegel exercises.

A noteworthy statistic in skilled nursing facilities is that 80% of residents are assisted with toileting. This highlights areas where improvements can be made, such as staffing and staff attitudes. Creating a positive impact is crucial, as instances of residents being disregarded when requesting toileting assistance can lead to potential urinary tract infections (UTIs) and other complications. As occupational therapy practitioners, we have an opportunity to make a significant difference in changing mindsets and attitudes and ultimately enhancing the quality of care provided.

By advocating for individualized care plans, promoting timely responses to residents' needs, and implementing evidence-based interventions, we can play a vital role in improving continence outcomes and overall well-being for those affected by urinary incontinence. Our contributions align with the guidelines for treatment, reinforcing the importance of a comprehensive and proactive approach to address this common and manageable condition effectively.

- Continuous process of consistently providing individualized care

- Completes a comprehensive, accurate, appropriate, and adequate exam

- Provides resident and family education

- Absorbent products should not be used as the primary long-term approach until….other alternative approaches have been considered

Providing individualized care is a continuous and essential process, which we often hear and acknowledge, but it requires a genuine commitment to living it in practice. Cookie-cutter approaches, such as toileting every two hours, do not align with individualized care. Instead, a comprehensive and accurate examination is crucial to determine the most appropriate and adequate treatment plan. In this industry, nursing typically takes the lead in this aspect, but occupational therapy, along with physical therapy, speech therapy, and pharmacy, play significant roles in ensuring a collaborative and holistic approach to care.

While absorbent products like pads can be used, they should not be the primary or sole method of managing urinary incontinence. Effective documentation must showcase efforts to explore other interventions first. Individualized treatment plans are essential, especially considering factors like cognition and comprehension, which significantly influence program effectiveness. Restoration programs cater to individuals who can actively participate and comprehend, while adaptive programs require staff involvement in implementing the plan.

Ultimately, the key takeaway is the importance of the least invasive evaluation and treatment methods, ensuring that the care provided is uniquely tailored to each resident.

Cost of Urinary Incontinence

The costs associated with urinary incontinence are multi-faceted and can be examined from various perspectives.

Clinical, Psychological, and Social Impact

- UI is often underreported, generally not identified, and when it is, often inadequately treated.

- UI imposes a significant psychological impact on individuals, their families, and caregivers.

Let's begin by examining the clinical, psychological, and social aspects of urinary incontinence. As previously stated, denial can contribute to underreporting and difficulty in identifying the condition. Even when identified, urinary incontinence may not always receive adequate treatment. There is a need for healthcare professionals with the skillset and willingness to address this issue effectively.

Family/Caregiver Psychosocial Costs

- Guilt

- Frustration

- Care-Giver Burden/Burnout

- Depression

- Risk of Mistreatment/Neglect

- Financial burden

- Institutional placement

Urinary incontinence not only affects the individual but also places significant psychological stress on their families and caregivers. Often, it becomes the primary reason for admission to long-term care settings, leading to challenges in socialization and participation in daily activities. From an occupational perspective, individuals may lose their sense of role as social beings, hindering their active engagement in life.

Family members and caregivers also experience a range of emotions, including guilt, frustration, depression, and burnout. They may struggle to provide the necessary care and support, feeling helpless in resolving the incontinence issue. This emotional toll can impact both the affected individual and their caregivers, limiting their ability to enjoy activities and outings together. There is also a risk of mistreatment, as individuals with urinary incontinence may face mistreatment or neglect in both home and institutional settings.

Anecdotal evidence highlights the reality of such mistreatment. In a five-star community, my aunt who had dementia and a UTI requested to use the restroom, only to be refused and left sitting in her urine as a form of punishment. Such incidents underscore the importance of addressing the psychosocial costs of urinary incontinence and providing compassionate care that upholds the dignity and well-being of those affected and their caregivers.

Individual Psychosocial Costs

- Psychosocial:

- Embarrassment/shame

- Anger

- Frustration

- Fear

- Depression

- Social restrictions

- Social isolation

- Quality of life:

- Loss of self-esteem

- Altered body image

- Impaired sexual functioning

- Lower quality of life

- Limited work productivity

Psychosocial costs associated with urinary incontinence encompass a wide range of emotions, including embarrassment, shame, anger, frustration, and fear. These feelings can lead to social isolation, adversely impacting an individual's quality of life. Issues with self-esteem and body image may arise as a result of incontinence, affecting one's sense of self-worth and confidence. The impact on sexual life and intimate relationships can be significant, as the fear of incontinence during intimate moments may cause distress and hinder sexual activity.

Furthermore, individuals of working age or those engaged in volunteering activities may face challenges in their respective occupations due to urinary incontinence, further impacting their overall quality of life. It is crucial to recognize that the psychosocial costs are not limited to urinary incontinence alone but also extend to bowel incontinence, which can be equally, if not more, distressing from a psychosocial perspective. Addressing these psychosocial factors and providing comprehensive support is essential to help individuals affected by incontinence maintain their dignity, well-being, and engagement in daily activities.

Cost of Complications

- Increased Risk of Falls

- Persons aged 60-80 form 53% urine while asleep

- More frequent trips to the bathroom

- Urine leaks on the floor cause falls

- The majority of falls occur while returning from the bathroom

- Disrupted Sleep

- Fatigue

When considering the physical aspect of urinary incontinence, bladder function plays a crucial role, especially in individuals aged between 60 and 80. During this age range, around 53% of urine is formed while sleeping, leading to more frequent trips to the bathroom at night, known as nocturnal urination. This can present challenges for seniors, particularly during nighttime awakenings when they may feel disoriented, encounter poor lighting, or lack the assistance of staff or family members. The location of assistive devices and potential hazards, such as mats on the side of the bed, can further complicate matters.

As a result, individuals may experience urine leakage on their way to or from the bathroom, sometimes leading to slips and falls. In some cases, they may not even remember the urine was present due to visual or cognitive factors. Disrupted sleep and increased fatigue from multiple nighttime trips to the bathroom can also impact an individual's overall well-being and performance of daily activities. This, in turn, may affect their role performance and engagement in occupations, highlighting the need for comprehensive care and interventions to address the physical challenges associated with urinary incontinence in this age group.

- Direct

- Skin irritations and infections

- Pressure ulcers

- Falls

- Urinary sepsis

- Physical activity restrictions

- Dehydration

- Medication side effects

- Indirect

- Drug side-effects

- Adverse drug effects

- Allergic reactions to drugs and materials

- Increased nursing care

- Lost wages

- Patient

- Family member

The following day may bring further considerations, like skin irritations, falls, dehydration, and medication side effects.

A common misconception among seniors is that they may believe reducing their fluid intake would be a suitable approach to managing incontinence. However, this is counterintuitive and not the best course of action. Decreasing fluid intake leads to higher medication concentrations and an increase in medication side effects, perpetuating a harmful cycle. We often encounter drug side effects and potential changes in roles due to these circumstances.

Cost of Incontinence

- Over $20 billion per year

- Most of that cost is spent on incontinence supplies and management, including pads and laundry.

- Routine care costs vary from $50 to $1,000 per person per year.

- Combined direct and indirect costs of UI amount to over $60 billion per year.

The annual cost of these issues amounts to over $20 billion. The majority of this expenditure is allocated to incontinence supplies, such as management pads and laundry soap. Routine care costs can vary significantly depending on the individual, ranging from $50 to over $1,000 per person per year. When considering both direct and indirect costs, the impact on our seniors reaches an astounding $60 billion.

From the perspective of skilled nursing facilities, the expenses are substantial. For instance, a community with around 100 to 200 beds could easily spend $10,000 to $15,000 per month on supplies alone.

Urinary Incontinence Costs

- Typical SNF resident is incontinent 5-7 times daily.

- Cost per incident without labor is $5.46 and $15.26 with labor.

While it may not be feasible to completely eliminate the issue of urinary incontinence, there is significant potential to improve the situation. On average, a person may experience incontinence five to seven times daily, incurring a cost of $5 per incident without factoring in labor, and $15 per incident when considering labor costs.

By focusing on reducing the frequency of incontinence episodes, we could achieve substantial cost savings. For instance, a 25% reduction would lead to savings of $6,500, not including supply costs. Similarly, a 50% reduction would yield even greater savings. However, it's essential to emphasize that the impact goes beyond financial considerations; it directly affects the well-being and quality of life of individuals, enabling them to be more active and engaged members of their communities. The potential positive impact is evident from the data presented in the accompanying slide.

Clinical Benefits of Treatment

- The National Institute of Health reported that a simple program of pelvic muscle exercises can reduce incontinent episodes by up to 86%.

According to a recent study reported by the National Institute of Health, a simple behavioral program that includes pelvic muscle exercises (commonly known as Kegels) has shown promising results in reducing incontinence episodes. The program can lead to a minimum reduction of about 29% to 30%, with some participants experiencing a remarkable 86% decrease in episodes. It is important to highlight that these positive outcomes are achieved without the need for surgical interventions, as the program focuses on non-invasive approaches.

As occupational therapy practitioners, we have the opportunity to make a significant impact by implementing these effective behavioral programs, improving the quality of life for individuals dealing with incontinence issues. While there are invasive options available as well, the study's results demonstrate the potential of non-invasive methods to bring about substantial improvements.

Anatomy and Physiology of Voiding

What is Continence?

- A state in which a person possesses and exercises the ability to store urine and micturate at a socially acceptable place and time.

Continence is defined as the state in which a person has the ability to store urine and exercise control over its release at a socially acceptable place and time. Incontinence, on the other hand, refers to the involuntary loss of urine, which can present as a social or hygiene issue and can be objectively observed.

When considering the definition of continence, it becomes evident that there are various points in the process where breakdowns can occur. These breakdowns may result from a range of factors, including medical conditions, muscle weakness, neurological issues, or other underlying causes. Identifying and addressing the specific factors contributing to incontinence is essential in developing effective interventions to manage or alleviate the problem.

Breakdowns in the process of continence can occur at various stages within the urinary system and the associated control mechanisms. For instance, problems might arise with urine production due to kidney dysfunction, affecting the filtration process that forms urine. Additionally, storing urine efficiently depends on the coordination between the bladder, sphincters, and urethra. Dysfunction in any of these components can result in difficulties with urine storage and possibly lead to incontinence.

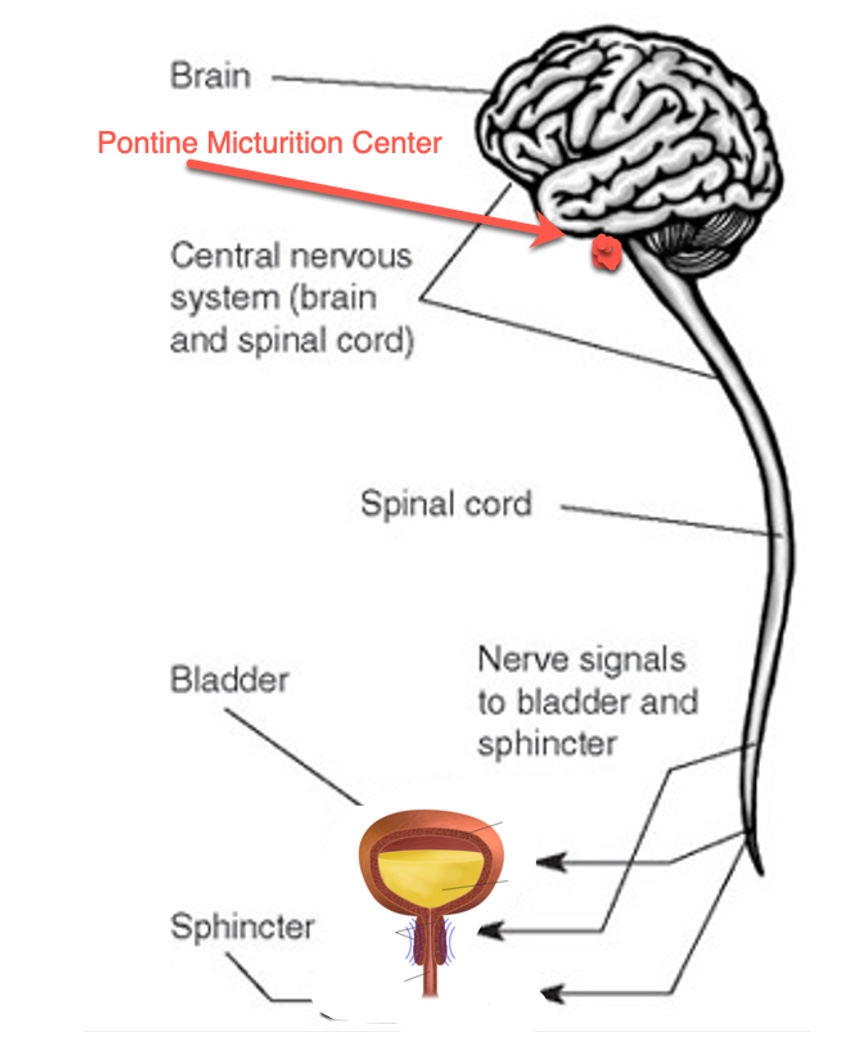

What is Micturition?

- Storage and emptying of urine from the bladder

- Spinal reflex influenced by higher centers of cortical control combined with the ability to voluntarily relax the pelvic musculature will lead to normal micturition.

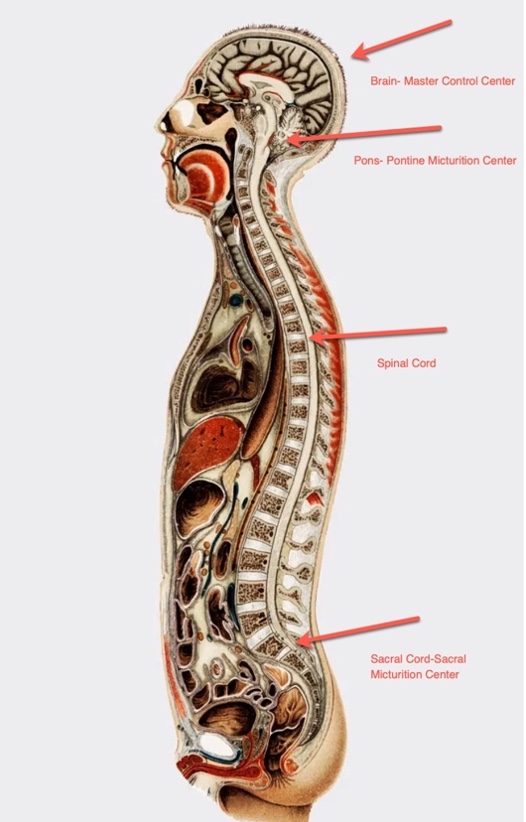

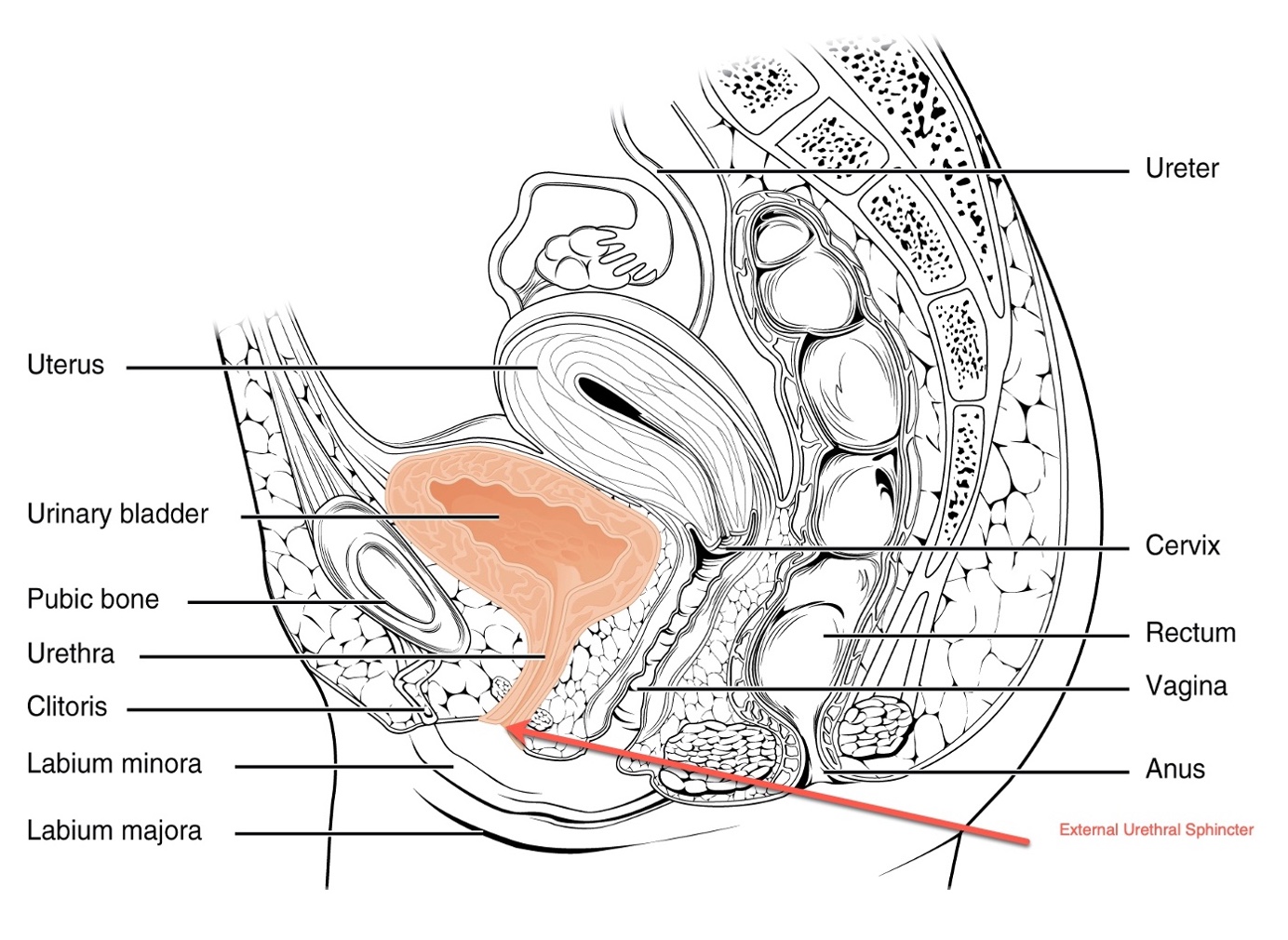

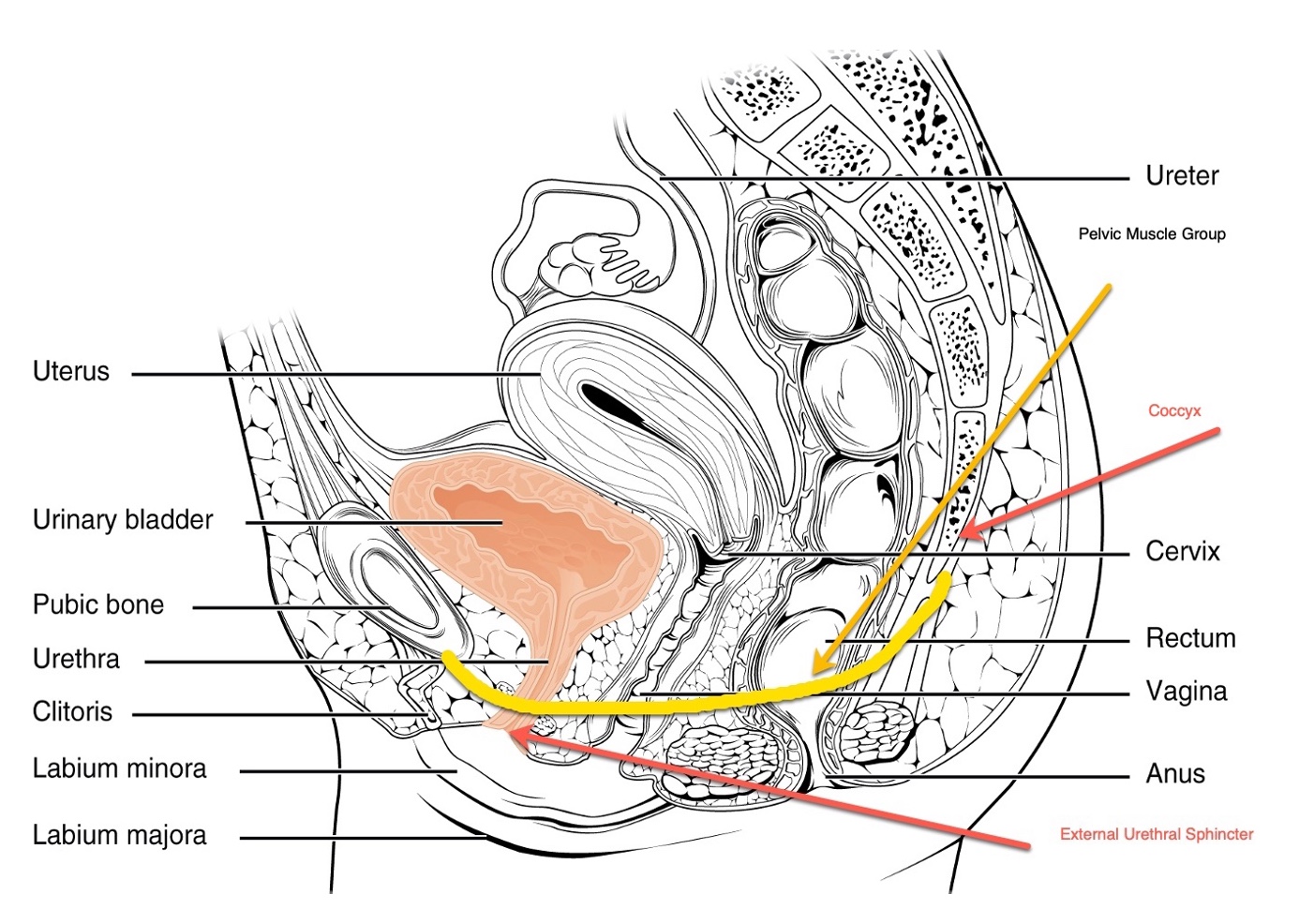

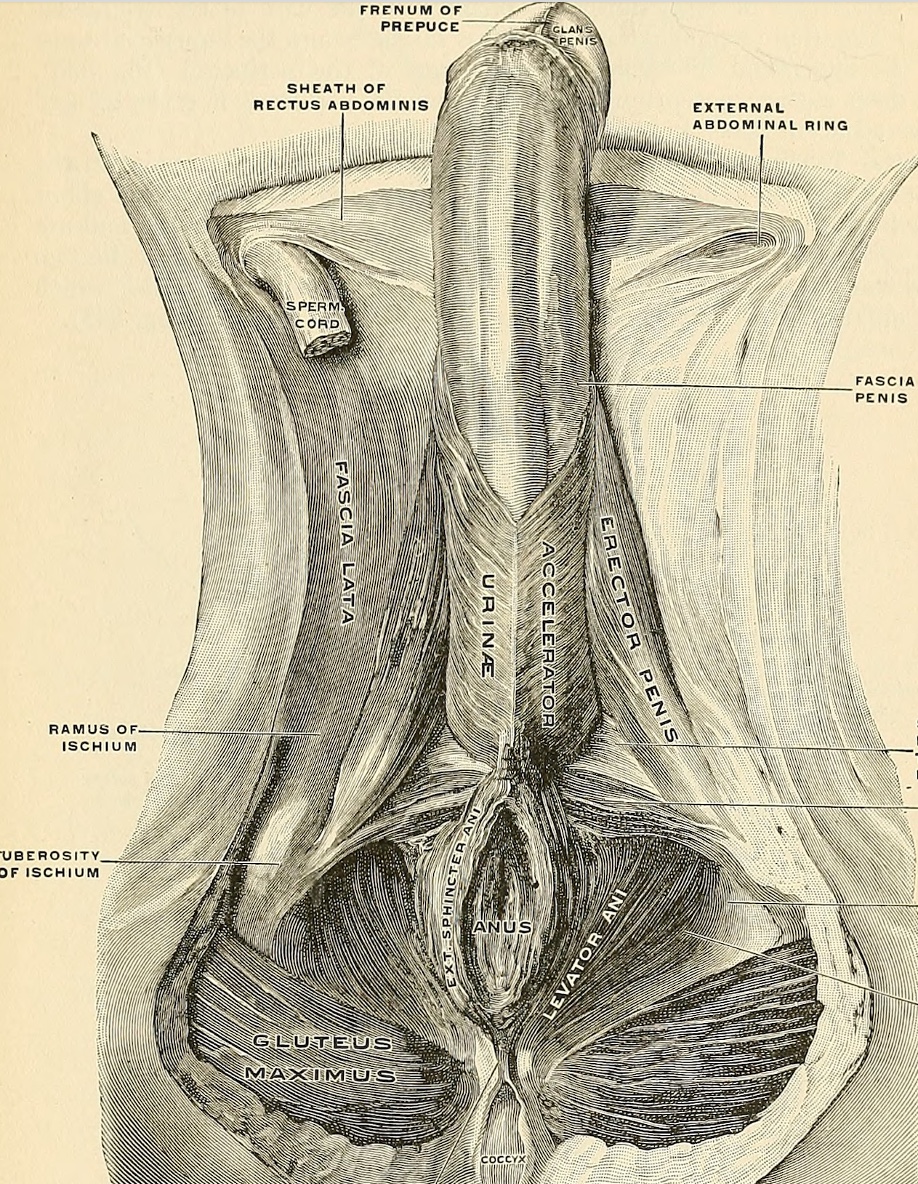

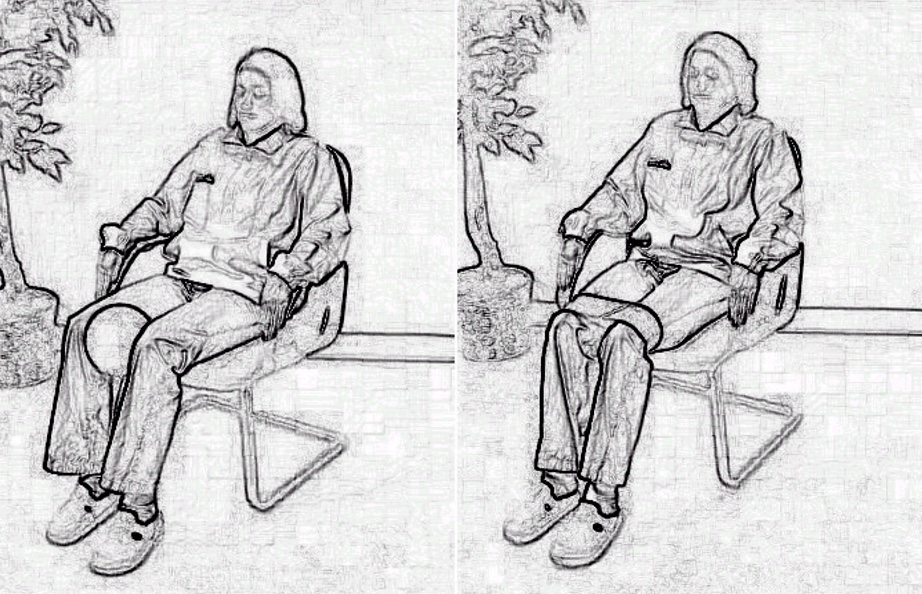

Figure 1 shows an overview of the system.

Figure 1. Lateral view of a person showing anatomical areas that control micturition.

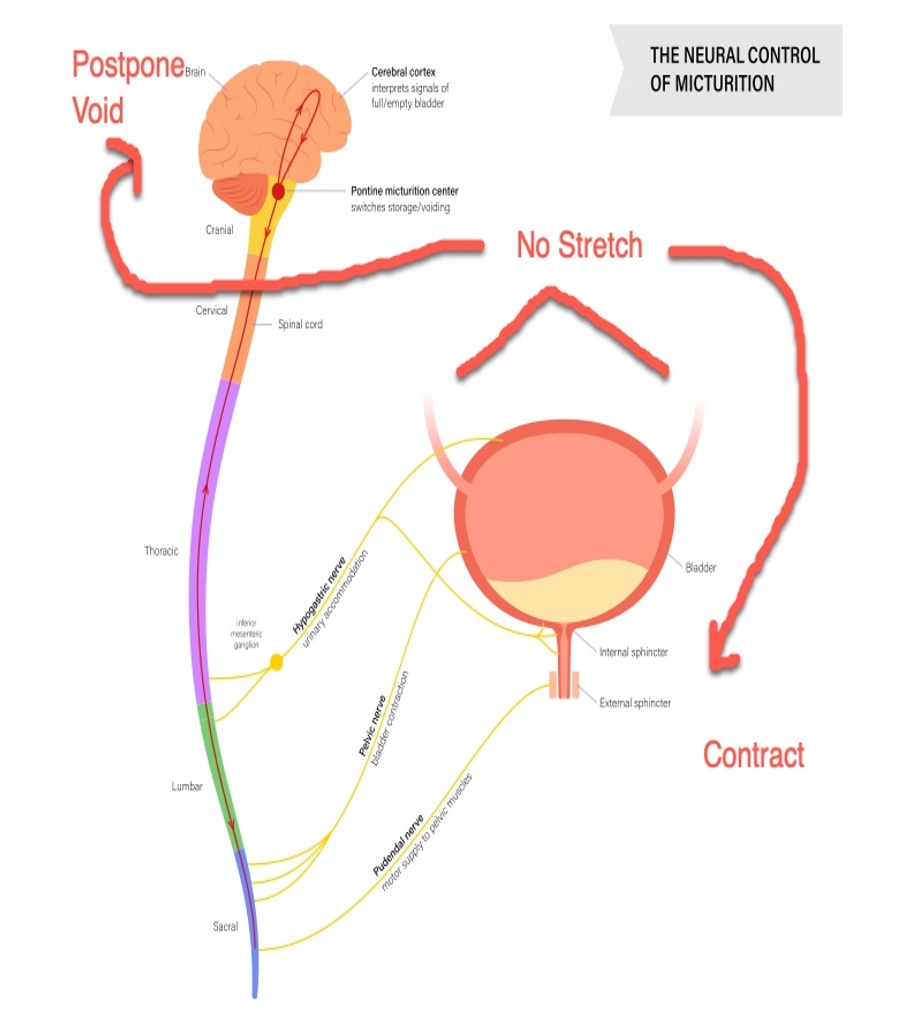

The micturition reflex is another critical aspect to consider. Normally, the bladder fills, and stretch receptors within it signal the brain, initiating the micturition reflex when the appropriate time to void arrives. However, certain conditions like an upper motor neuron lesion or cognitive impairment can disrupt this reflex inhibition, leading to uncontrolled urination.

Nerve signals play a vital role in the entire urination process. Diseases, conditions, or injuries that damage the nerves involved can cause various urination problems. For example, conditions like diabetes, stroke, Parkinson's, multiple sclerosis, or spinal cord injuries can impact the nerves responsible for bladder function, leading to challenges in emptying the bladder.

The coordination between sensory and motor nerves is essential for the proper functioning of the urinary system. Sensory nerves, such as the parasympathetic nerves at S2-S4, provide feedback about the bladder filling sensation, while motor nerves control the detrusor muscle and the bladder neck for emptying. Understanding these interconnected processes helps us identify potential urinary issues and design appropriate behavioral interventions, such as Kegel exercises, to override the feedback loop and address certain urination problems effectively.

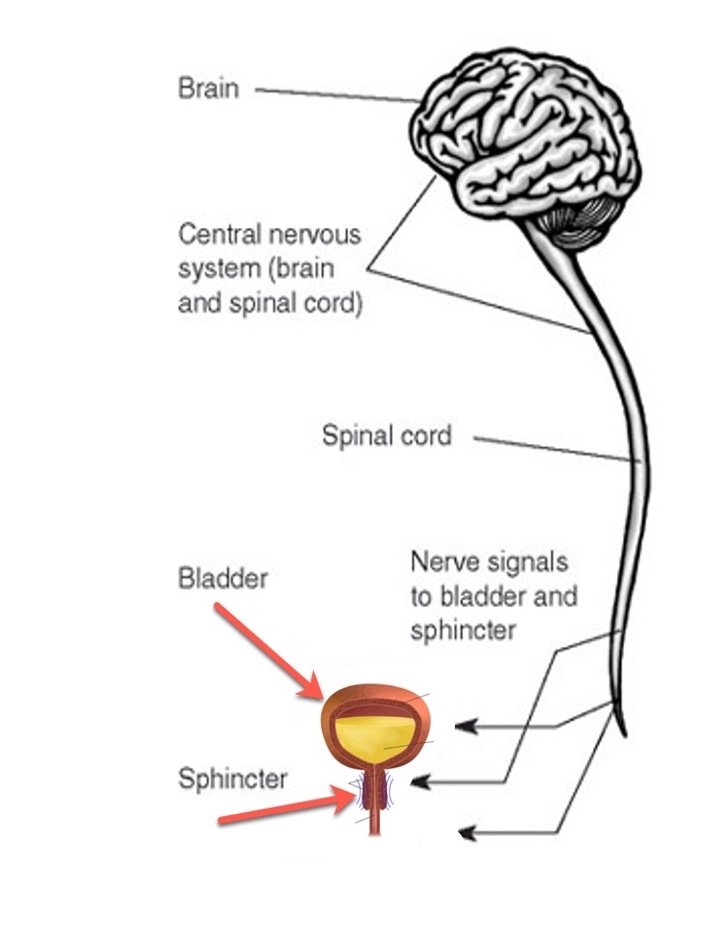

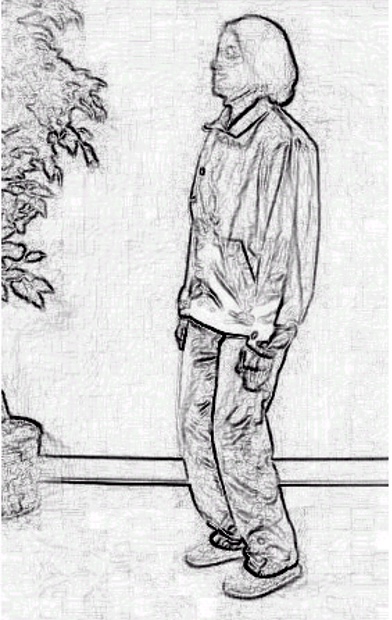

Figure 2 shows another graphic of the different areas of control.

Figure 2. Another graphic shows anatomical areas that control micturition.

Urinary System Structures

- Kidneys

- Ureters

- Bladder

- Urethra

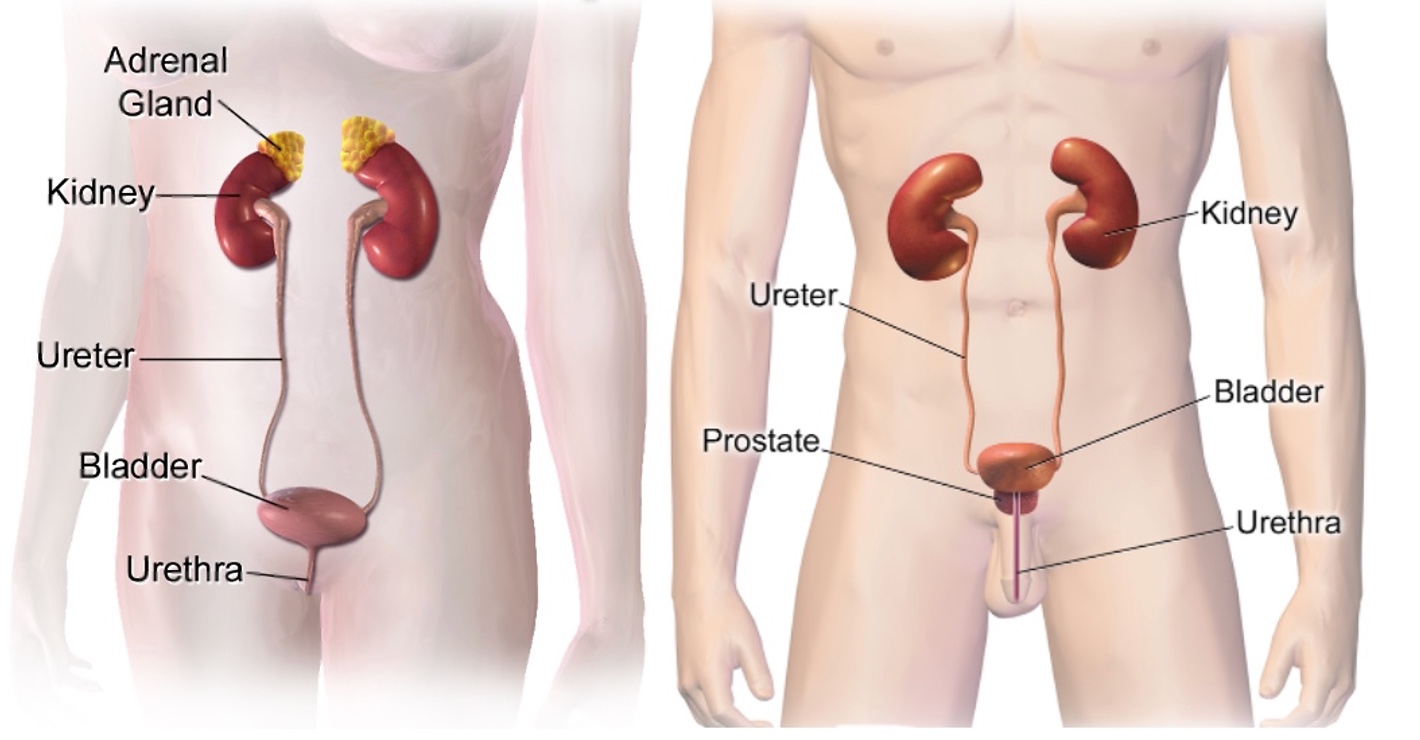

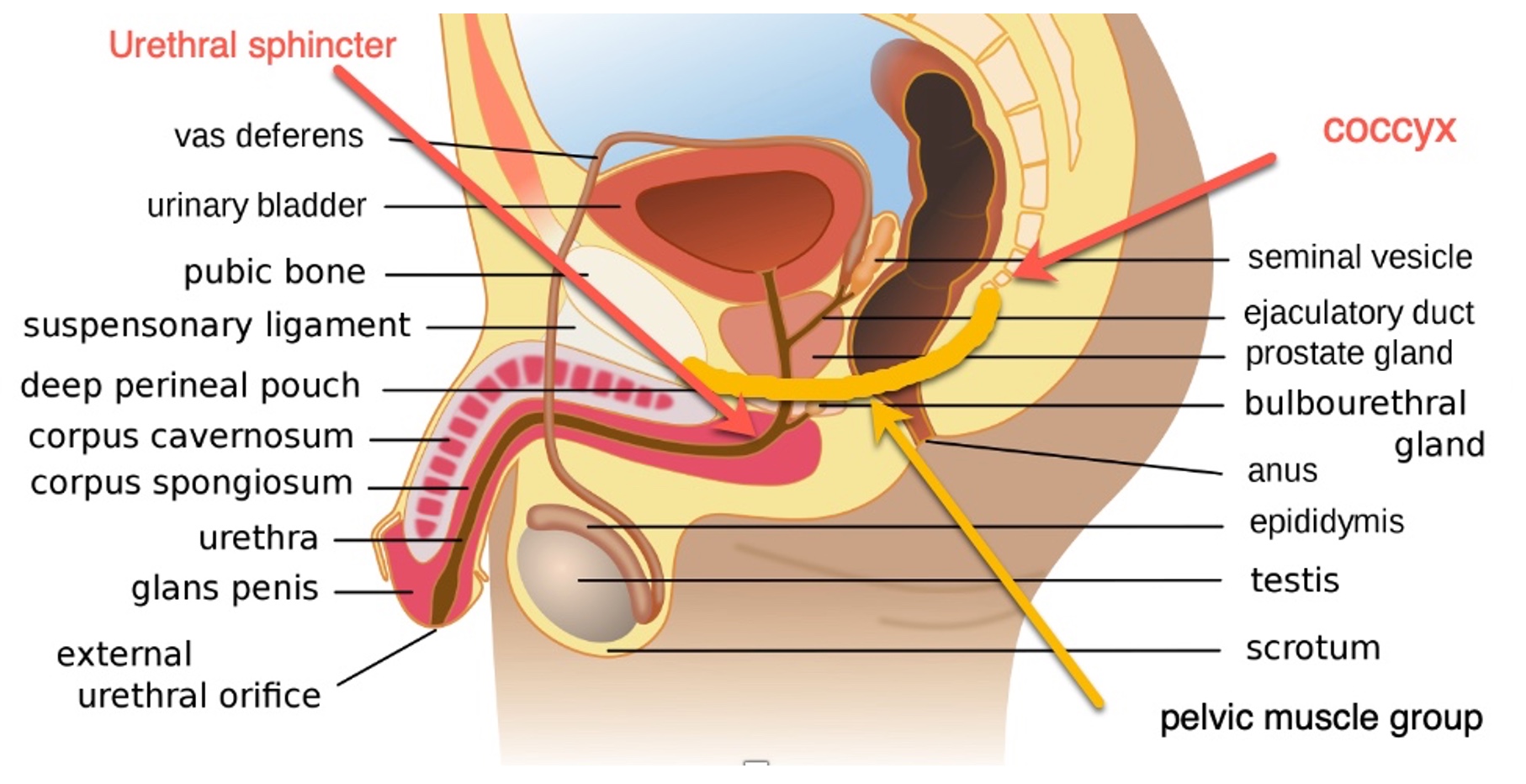

The urinary system comprises several essential structures that work together to maintain the body's fluid and waste balance. Let's take a closer look at each of these components. It is also shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. The anatomy of the urinary system for both a female and male

The kidneys, akin to two remarkable filters, are located on either side of the spine just below the ribcage. Their function is akin to that of a master chemist, responsible for filtering waste products, excess substances, and toxins from the blood to form urine. Just like a meticulous chef, the kidneys ensure that only the right elements are kept while the unwanted waste is discarded. For instance, they regulate the levels of substances like sodium, potassium, and calcium, ensuring our body stays in proper balance.

Picture the ureters as the reliable transport system connecting the kidneys to the bladder. These long, muscular tubes skillfully carry the produced urine from each kidney, like diligent couriers making sure the precious cargo reaches its destination promptly. Think of them as the conduits that facilitate communication between the kidneys and the bladder.

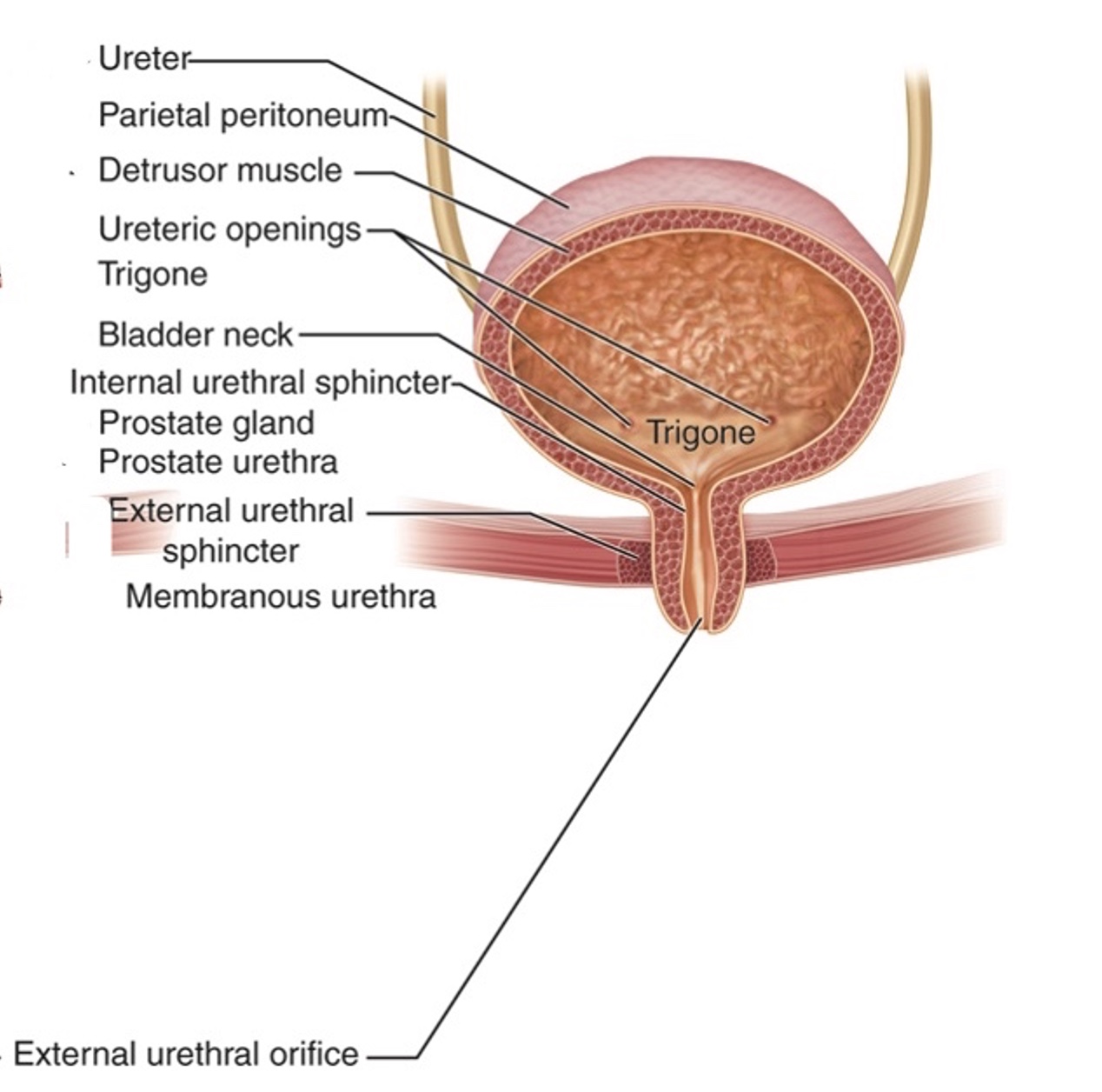

The bladder, also known as the detrusor, serves as a flexible reservoir for urine storage. It's akin to a well-designed expandable bag, capable of accommodating varying amounts of urine. The bladder can stretch to hold a substantial volume of fluid, and it remains relaxed while gradually filling up. When it's time for elimination, the detrusor contracts and exerts pressure on the stored urine, pushing it toward its final destination through the urethra.

Lastly, the urethra acts as the gateway for urine to exit the body. This narrow tube extends from the bladder to the outside world. Think of it as a security door, tightly closed to keep urine in the bladder until it's time to go. When that time comes, the urethra opens up, allowing the urine to flow out smoothly, like water through a controlled faucet.

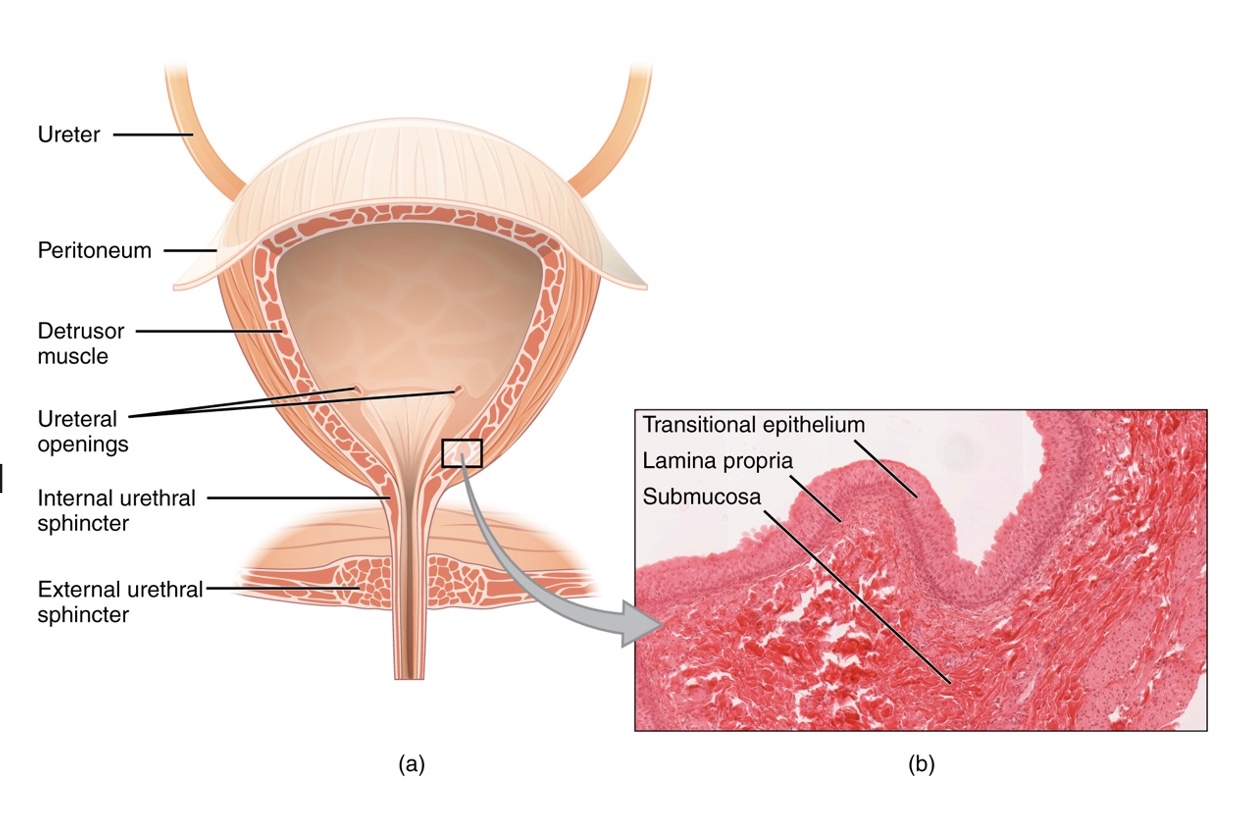

Bladder/Detrusor

- Located behind the pubic symphysis

- Hollow muscular sack expands to hold + 1 pint of fluid

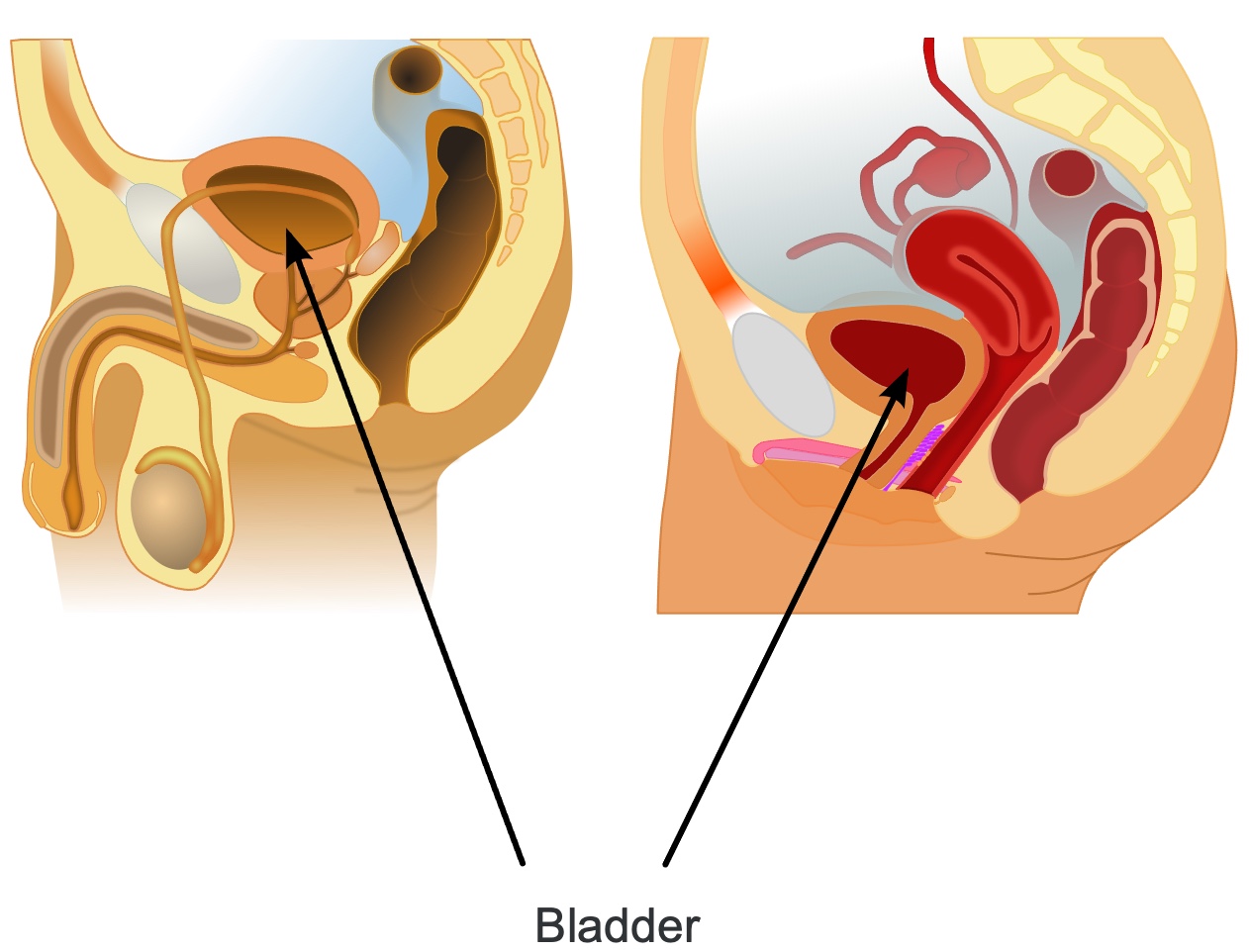

The bladder is also known as the detrusor. It is positioned behind the pubic symphysis and is described as a hollow muscular sac. The bladder has the capacity to expand and hold approximately one pint of fluid. Figure 4 includes cross-sections of both male and female anatomy.

Figure 4. Graphics of the bladder or detrusor muscle in male and female anatomy.

In the female cross-section on the right, you can observe the bladder located just above the uterus. During pregnancy, as the uterus expands, it can exert pressure on the bladder, potentially leading to issues with urinary incontinence.

Likewise, in the male cross-section on the left, you can see the bladder positioned in front of the rectum. There is a close relationship between these two organs, and issues such as chronic constipation and incomplete emptying of the rectum could result in pressure on the bladder, leading to urinary incontinence as well.

Understanding the anatomical relationships and potential sources of pressure on the bladder is crucial for identifying the underlying causes of urinary incontinence in both male and female patients. Addressing these factors can help in developing effective management and treatment strategies for individuals experiencing urinary incontinence.

Urethra

- Hollow muscular tube

- Smooth muscle lining of the urethra contracts to keep urine from leaking or relaxes to let urine flow out

- Length of the urethra

- Males up to 20cm (length of the penis)

- Females 3-4 cm

The urethra is a smooth muscular tube that serves as the pathway for urine to exit the bladder and be voided from the body. In males, the urethra is considerably longer, approximately 20 centimeters, spanning the entire length of the penis. On the other hand, in females, it is much shorter, measuring around three to four centimeters (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Example of the urethra on female anatomy.

The inner lining of the urethra contains smooth muscle, which contracts to maintain urinary continence, preventing urine from leaking out of the bladder when not desired. Conversely, when the person is ready to urinate, the smooth muscle relaxes, allowing the urine to flow out.

The urethra is equipped with sphincters—internal and external—which also play a crucial role in maintaining urinary control. These sphincters contract to keep urine in the bladder until it's time for elimination.

- Urethra gets support from the pelvic floor as it provides closure pressure on the urethra.

Additionally, the pelvic floor plays an essential role in supporting the bladder and the urethra. The pelvic floor is highlighted in yellow in Figure 6.

Figure 6. The pelvic floor highlighted on female anatomy.

The pelvic floor muscles, resembling a sling or hammock, contract to lift and support the bladder, particularly its neck. This positioning helps control the release of urine, allowing it to flow when needed and preventing leakage at inappropriate times.

In male cross-sections, you can observe the relationship between the urethra and other surrounding structures, providing further insights into the complex anatomy of the urinary system.

Understanding the interplay of the urethra, sphincters, and pelvic floor is essential in addressing issues related to urinary continence and developing effective strategies for managing urinary problems in both males and females.

Prostate

- Prostate is a gland which surrounds the neck of the bladder and the urethra in the male.

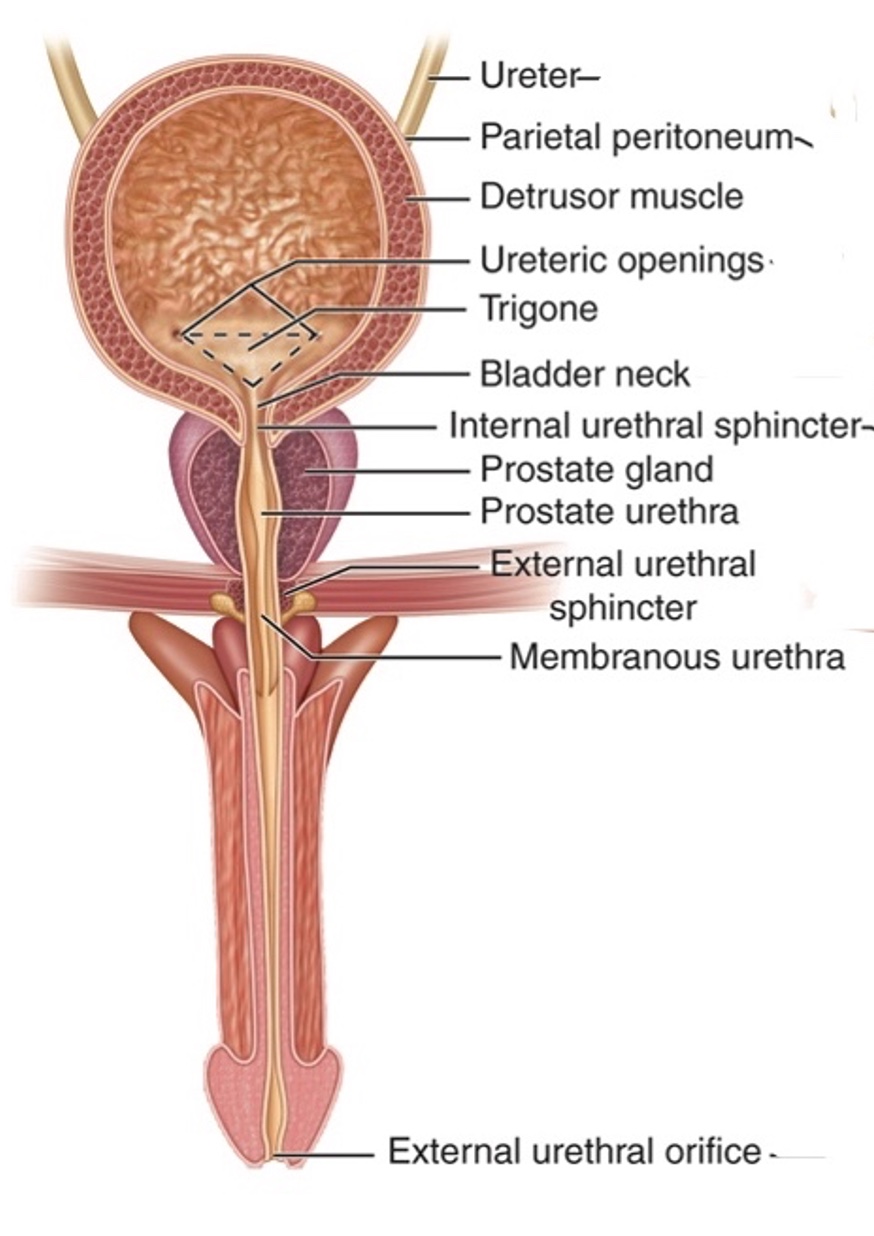

The prostate gland is situated just below the bladder, as shown in Figure 7, and it can be visualized in the cross-sections as the area right above the yellow pelvic floor line.

Figure 7. Graphic showing the prostate gland on male anatomy.

One important characteristic of the prostate gland is that it surrounds the urethra. As you can see, the urethra originates from the bladder, runs through the prostate, and continues its path until it exits the body.

The positioning of the prostate around the urethra can have significant implications for urinary flow. If the prostate becomes enlarged due to conditions like benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) or prostate cancer, it can obstruct the urethra, leading to difficulties in urination. In elderly men, BPH is a relatively common condition where the prostate gland gradually enlarges, potentially causing urinary problems by constricting or partially blocking the urethra.

This obstruction can significantly impact the flow of urine, causing hesitancy, a weak stream, incomplete emptying of the bladder, or even a complete stoppage. Depending on the severity of the enlargement or the presence of other prostate-related conditions, medical intervention may be necessary to address the urinary issues and ensure proper urinary function.

Understanding the relationship between the prostate gland and the urethra helps healthcare professionals identify potential urinary flow problems in male patients and implement appropriate treatment strategies to alleviate symptoms and improve overall urinary health.

Structures Involved in Micturition

- Bladder/Detrusor

- Smooth muscle under voluntary control

- Trigone

- Area where ureters empty into the bladder and looks like a triangle

- This area contracts first to help prevent the reflux of urine back up to the kidneys

Let's delve into the structures related to urinary control. The bladder contains the detrusor muscle, which is a smooth muscle under involuntary control. However, the feedback loop enables us to exert some voluntary control over its functions, such as retaining or releasing urine.

Another crucial structure is the trigone, an area in the bladder where the ureters empty. The trigone's significance lies in its automatic contraction when there is an issue, preventing the reflux of urine back into the kidneys and reducing the risk of kidney infections.

In the cross-section images of Figures 8 and 9, we can observe the bladder's location, surrounded by the levator ani muscle group, responsible for supporting the pelvic floor. The external urethral sphincter and internal urethral sphincter control the opening and closing of the urethra.

Figure 8. Female cross-section of urinary structures controlling micturition.

Figure 9. Male cross-section of urinary structures controlling micturition

In males, the prostate's relationship with the urethra can impact urinary output, particularly if there is an enlargement of the prostate. Understanding these structures and their interconnections is essential in comprehending the complexities of urinary control and potential issues related to urinary incontinence.

Normal Bladder Filling

- Kidneys produce urine which is transported through the ureters to the bladder.

- To prevent urine loss as the bladder fills, there is a gradual increase in urethral resistance – contraction of the urethra

- Pelvic floor muscles, stimulated by the autonomic and voluntary nervous systems, return to a low level of tonic contraction which helps maintain continence.

- The bladder fills from the bottom up and normally fills at a rate of about 1 ml/min by a series of squirts from the ureters (urine always being produced and dumped into the bladder)

Let's dive deeper into the process of normal bladder filling, as shown in Figure 10, as it is crucial to understand the feedback loop involved in continence.

Figure 10. Illustration of normal bladder filling (Click here to enlarge the image.)

The kidneys produce urine, which then travels through the ureters and collects in the trigone area of the bladder. As the bladder fills, the urethra contracts to prevent urine loss. Additionally, the pelvic floor maintains a low-level tonic contraction to support and close off the sphincter. This sustained muscle activity is essential for continence, as it holds back the urine and gradually strengthens as the bladder fills.

- Initially, there is no sensation of filling (stretch receptors not firing)

- As it fills, a vague sensation deep in the perineum develops but is easily ignored

- With further filling, the sensation becomes harder to ignore; at this stage, voiding will need to occur

- Afferent or sensory nerves for this sensation originate from stretch receptors in the detrusor and run in the pelvic nerves and then in the lateral column of the spinal cord

- Bladder filling occurs via neural responses

- Sympathetic system via T10-L2 by stimulating the bladder, neck, and proximal urethra

- The parasympathetic system is activated.

- In the sacral spine (S2-S4) by stimulating the detrusor muscle (normally inhibited by the descending fibers from the pons so that the detrusor does not contract)

- Additional spinal-level inhibition

- Created by the somatic contraction of the pelvic floor and external urethral sphincter

- *EMG studies of the urethra and pelvic floor during bladder filling show increased muscle fiber recruitment of both these structures

The stress reflex ensures that the pelvic floor continues to contract and support, and the urethral resistance remains intact to prevent leakage. The external sphincter, surrounded by striated muscle, plays a critical role in keeping urine from leaking.

The mid-brain's pontine center is responsible for reflexive control, which can be overridden by the cortex. However, this conscious control generally develops around the age of two. When it's appropriate to void, the cortex sends a message allowing the reflex to occur. Alpha motor neuron activity drops to remove inhibition, resulting in sphincter relaxation, enabling voiding.

The shape and angle of the bladder and its neck play a significant role in proper voiding. The pelvic floor's contraction helps maintain the appropriate bladder shape, postponing or delaying the voiding. Proper voiding requires the muscles to relax, drop the bladder's angle, and allow urine to flow. However, if the pelvic floor muscles are weak, relaxation may lead to voiding when it's not intended. It's essential to strike a balance in strengthening these muscles to prevent urinary incontinence and ensure proper voiding when desired.

Normal Bladder Emptying

- When the bladder fills to a specific volume, stretch receptors in the bladder sense fullness (T10-L2)

- At the appropriate time and place, the brain releases inhibitory control, and a voluntary micturition reflex occurs, initiating detrusor (bladder) contraction and relaxation of the smooth and striated muscles of the sphincters (T10-L2 and S2-S4)

- Pons micturition center causes bladder emptying by relaxation of the pelvic floor, relaxation of urethral sphincters, sustained detrusor contraction forcing urine from the bladder

The reflexive control of the bladder's filling and emptying is largely coordinated by the brainstem's pontine center. While this reflex operates automatically, the cerebral cortex can exert conscious control over it when the appropriate time and place for voiding are recognized. When the cortex sends the signal to relax the pelvic floor and sphincter muscles, urination occurs. An overview of this can be seen in Figure 11.

Figure 11. An illustration of bladder emptying.

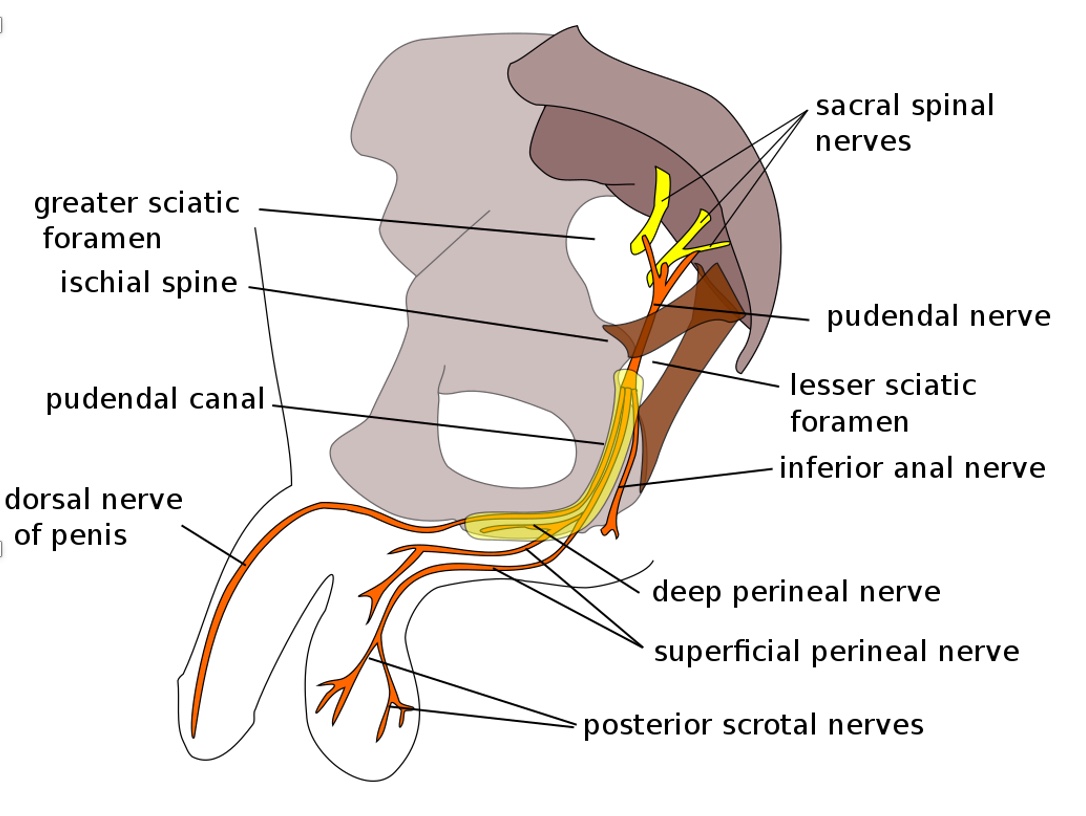

The Pudendal Nerve

- Supplies:

- Most of the innervations to the perineum.

- Toward the distal end of the pudendal canal, the pudendal nerve splits to form the dorsal nerve of the penis or clitoris and the Perineal nerve.

- These nerves run anteriorly on each side of the Pudendal artery.

- The Perineal nerve gives off scrotal or labial branches and continues to supply the muscles of the urogenital diaphragm.

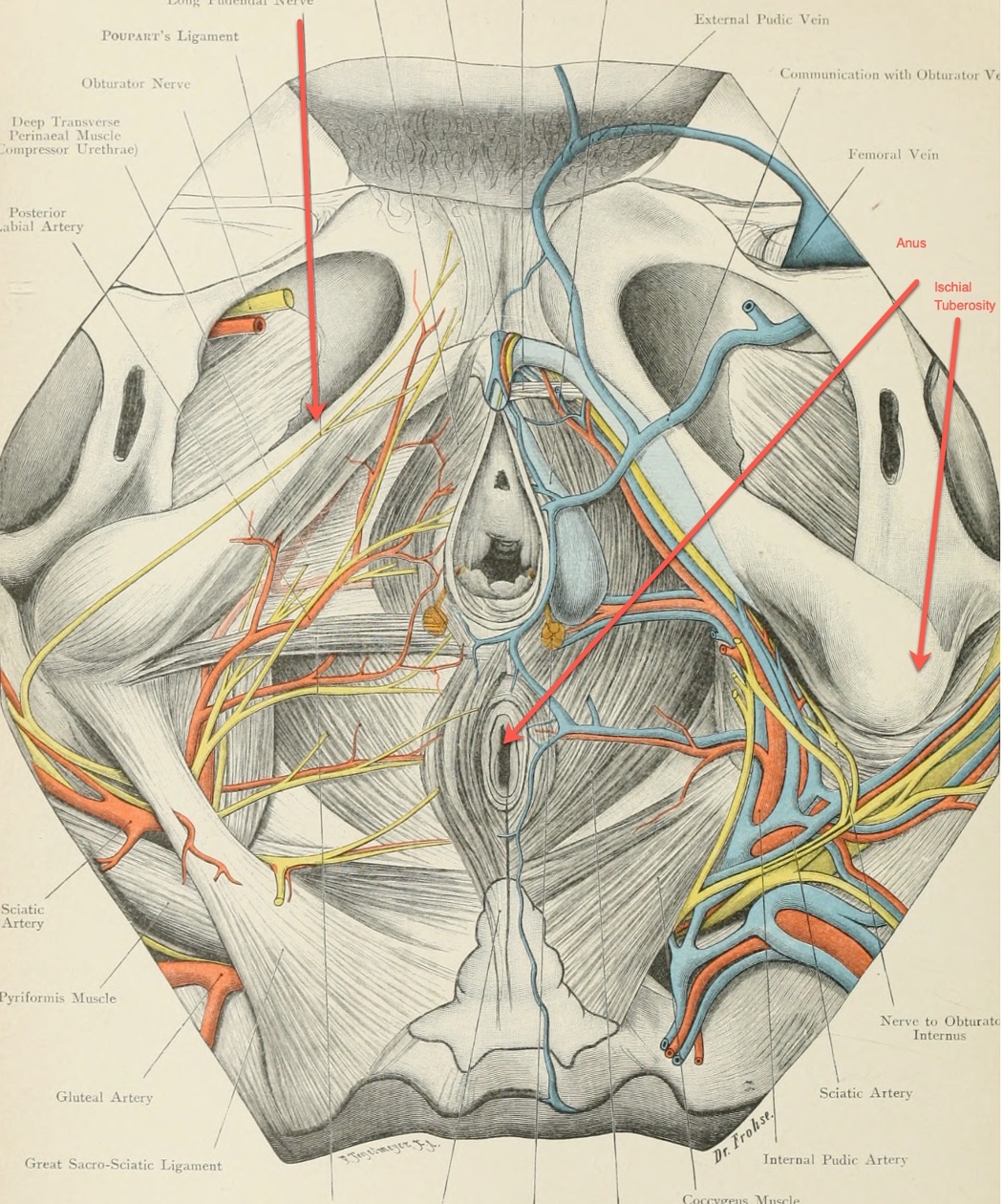

The pudendal nerve plays a crucial role in bladder control, originating from the S2-S4 nerve roots (Figures 12 and 13).

Figure 12. Illustration of the pudendal nerve in a male.

Figure 13. Illustration of the pudendal nerve in a female(Click here to enlarge the image.)

The pudendal nerve innervates the pelvic region, providing sensory and motor input to the striated muscle groups, including the pelvic floor and external sphincter.

Additionally, it has autonomic branches that communicate with the smooth muscle of the bladder and pelvic floor. The pudendal nerve also transmits information to the cerebral cortex, inhibiting the micturition reflex.

- Take Note:

- Elderly with compression fractures at S2-S4

- Osteoporosis etc., can lead to urinary retention since the peripheral parasympathetic nerves from S2-S4 facilitate the contraction of the detrusor

- Radical prostatectomy, as well as pregnancy and childbirth, can damage the pudendal nerve, also located at the S2-S4 level.

- Detrusor motor control area in the cerebral cortex arterial supply is from the middle and anterior arteries.

- The same arteries are affected by CVA, leading to an unstable bladder.

- Elderly with compression fractures at S2-S4

This complex nerve network is significant as it influences bladder function and can be impacted by various factors, such as posture, compression fractures, or labor and delivery-related issues.

Muscle Contractions

Urinary Sphincters

- Sphincters used to stop sudden urine flow

- Fast twitch fibers(35%) act quickly and intensely when coughing, sneezing, or doing something unexpected that increases the pressure on the bladder and urethra

- External sphincter under voluntary control

- (i.e. open and close these circular muscles at will through the Pudendal nerve)

- Internal sphincter NOT under voluntary control

- (in females, the internal sphincter is not effective as the bladder angle changes)

- Internal sphincter

- For males is above the prostate and externally below the prostate

- For females is located toward the neck of the bladder

The urinary sphincters, both external (voluntary control) and internal (involuntary control), are crucial in maintaining continence. These are shown in Figure 14.

Figure 14. Illustration of sphincters.

- Sensory through T10-L2

- Motor contraction of the pelvic floor and the urethra through S2-S4

The pelvic floor's sustained low-level contraction and the fast twitch fibers in the sphincters work together to prevent urine leakage during everyday activities like sneezing or coughing. Understanding these intricate systems can help in addressing urinary incontinence and improving overall bladder health.

The relationship between the urinary sphincters and the pelvic floor muscles is closely interconnected in terms of anatomy and function. While the sphincters themselves are not part of the pelvic floor muscles, they work in tandem to maintain continence.

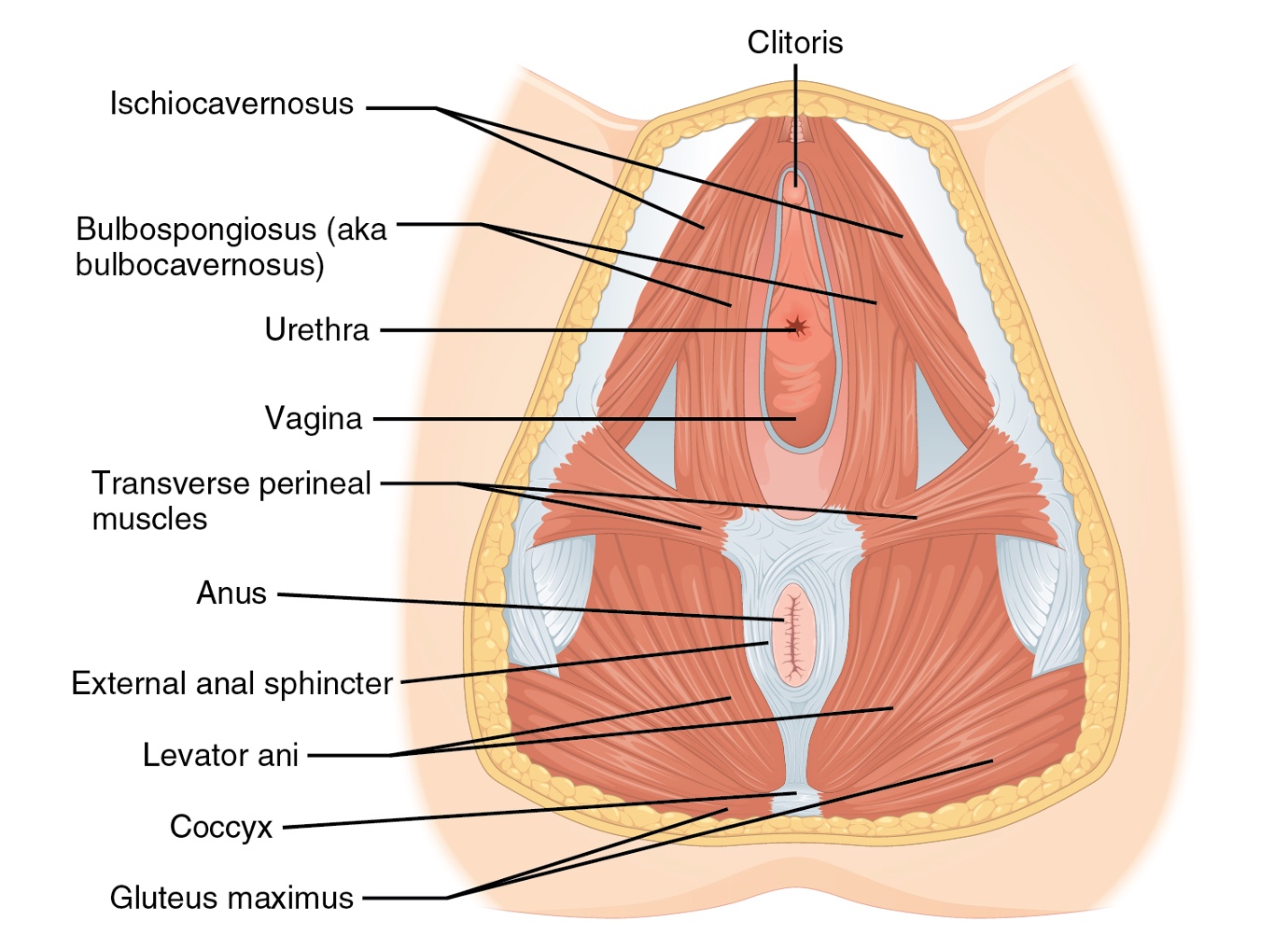

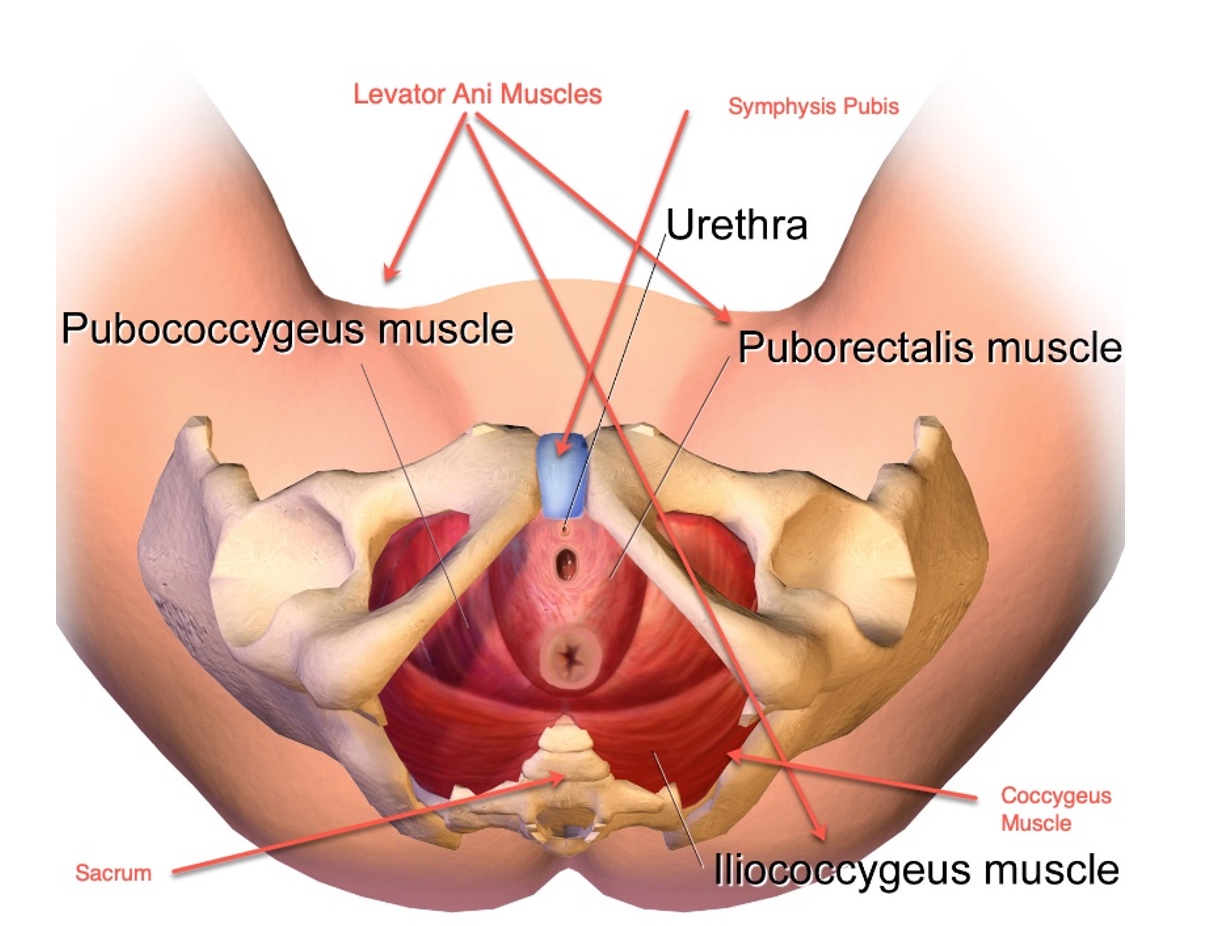

Pelvic Floor Muscles

- Levator Ani Muscles form the pelvic floor

- Pubococcygeal

- Iliococcygeal

- Ischiococcygeal

- Function in a sling-like fashion/hammock, maintaining constant low-level contraction for postural support of the internal organs

- Also called the pelvic diaphragm

- Deep muscle group of the perineum

The pelvic floor muscles, also known as the Levator Ani, consist of three main muscles: the pubococcygeal, iliococcygeal, and ishiococcygeal muscles. These deep muscles function like a sling or hammock, providing support to the internal organs and maintaining a constant low-level contraction.

- Support the bladder and urethra for an optimum position for continence

- Primarily slow twitch or type I muscle fibers

- Attach to the obturator tendon, the pubis, the sacrum, and the inner surface of the pelvis

- Also involved in providing improved closure of the urethral and anal sphincters

- The pubococcygeal muscle assists the urinary sphincter

- The iliococcygeal muscle assists in support of the vagina

- Ishiococcygeal muscle assists the anal sphincter

When they relax, the visceral contents drop down, allowing for the proper relaxation and emptying of the bladder. The pelvic floor muscles primarily consist of slow twitch or type one muscle fibers, which enable them to sustain contractions for extended periods, supporting bladder control.

These muscles are closely related to the hip and pelvic musculature, and any issues with hip fractures, hip replacements, or poor positioning can potentially impact the levator ani muscles and contribute to problems with urinary continence. The three components of the Levator Ani have specific functions: the pubococcygeal supports the urethra for storage, the iliococcygeus supports the vagina, and the ishiococcygeal assists the anal sphincter. Together, they have four main purposes: providing support to the viscera, facilitating storage by exerting passive and dynamic force on the urethra, inhibiting the detrusor to further support storage, and elongating to allow strain-free evacuation during voiding.

In Figures 15, 16, and 17, the illustrations depict the pelvic floor muscles from different angles, providing a clear visual of the hammock-like structure they form to support the internal organs and contribute to continence.

Figure 15. Pelvic floor muscles in a female.

Figure 16. Another illustration of the female pelvic floor muscles.

Figure 17. Illustration of the male pelvic floor muscles.

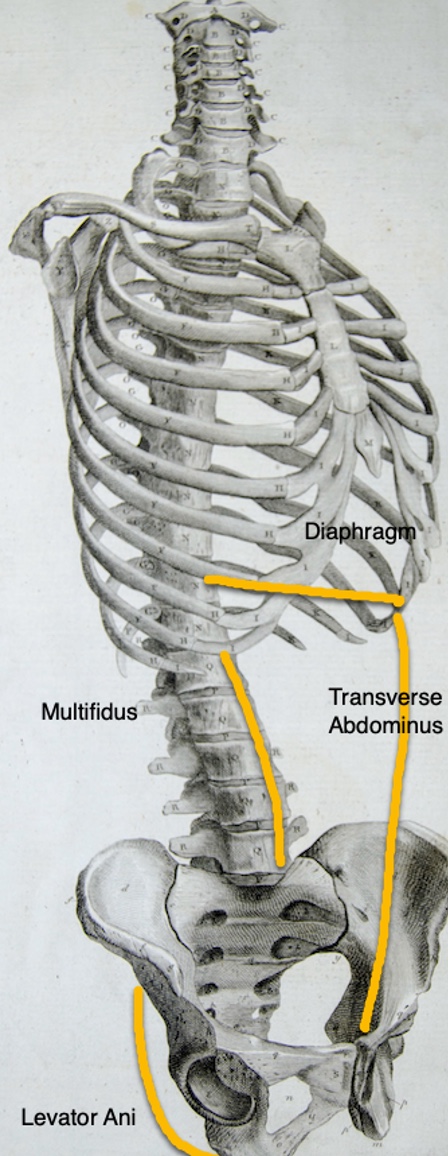

Lower Quadrant Cylinder

- Muscles forming the lower cylinder

- Diaphragm superiorly

- Multifidus posteriorly

- Transverse abdominus anteriorly

- Levator ani inferiorly

- When we move, these core muscle groups are active in all movements.

This cylinder concept involves a rectangular structure consisting of the diaphragm at the top (superiorly), the multifidus at the back (posteriorly), the transverse abdominis at the front (anteriorly), and the pelvic floor muscles (levator ani) at the bottom (inferiorly), and it is shown in Figure 18.

Figure 18. Illustration of the lower quadrant cylinder.

Understanding the cylinder concept is crucial because it highlights the interconnectedness of these muscles and their role in various activities. The levator ani, being part of the pelvic floor, plays a significant role in supporting the viscera and maintaining continence. It is activated during numerous daily activities, such as transfers, rolling, sit-to-stand movements, bending, reaching, and gait.

The cylinder concept also emphasizes the indirect interactivity between the different muscles. For example, activating the transverse abdominis can indirectly impact the levator ani. Similarly, the diaphragm's proper function is essential, especially during exercises, as it affects the entire cylinder and can influence the feedback loop associated with continence.

Types of Incontinence

- Stress

- Urge

- Mixed

- Overflow

- Functional

- Iatrogenic

Stress Urinary Incontinence (SUI)

- Involuntary loss of urine, occurring when, in the absence of a detrusor contraction, the intravesical pressure exceeds the maximum urethral pressure

- Leakage of small amounts of urine during physical movement (laughing, coughing, sneezing, exercising)

Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) is characterized by the involuntary loss of urine when the pressure inside the bladder exceeds the maximum urethral pressure, resulting in leakage during activities that increase intra-abdominal pressure. This type of incontinence is more commonly seen in women, often following pregnancy or childbirth, and can also occur in men after prostate surgery (TURP).

- Storage problem

- Deficient urethral closure mechanism

- Associated with intra-abdominal pressure

- Pressure gradient does not work

- Women > Men (due to pregnancy/childbirth)

- High levels of physical activity (e.g., running)

It is a failure to store urine properly, and the leakage usually occurs in small amounts.

- Causes of Stress UI

- Incompetent urethra/stretching from childbirth

- Weak pelvic floor musculature

- Prostate surgery

- Neurologic dysfunction and atrophy – reaction time from abdominal pressure increase to sphincter activation too slow

- Denervation injury of pelvic floor musculature due to pregnancy

Causes of SUI can include an incompetent urethra due to stretching from childbirth or weak pelvic floor muscles. Neurologic dysfunction, such as delayed sphincter response, can also contribute to SUI.

- Age-related hormonal deficiencies and atrophy of tissues

- Lower estrogen levels

- Changes in urethral mucosa

- Changes in cell structure/connective tissue

Other factors like estrogen deficiency, obesity, urethral sphincter weakness, and changes in urethral mucosa or connective tissue can play a role in this type of incontinence.

- Treatment for Stress UI

- No approved pharmacological agents

- First-line therapies (pelvic floor rehab)

- Urethral bulking with injectable agents

- Surgery (urethral support by sling)

When it comes to treatment, first-line therapies involve pelvic floor rehabilitation and exercises. Electrical stimulation, such as medium-frequency Russian stim or interferential stimulation, may be used as a form of pelvic floor rehab. Injectable agents into the urethra can also provide some relief by strengthening the area. In some cases, surgery may be considered, but most cases of SUI can be effectively managed with conservative approaches like pelvic floor rehab.

Urge/Overactive Bladder (OAB) Incontinence

- Involuntary loss of urine associated with a strong desire to void (urgency)

- Leakage of large amounts of urine at unexpected times, including during sleep

- Urge incontinence results when an overactive bladder contracts without us wanting it to do so.

- Feel as if they can't wait to reach a toilet

- May leak urine without any warning at all

- Infection can cause irritation to the bladder lining

- Can be a nervous system problem

Urge incontinence is another type of failure to store urine, where the person experiences an involuntary contraction of the detrusor muscle in the bladder, leading to a sudden and strong urge to urinate, often resulting in leakage before reaching the toilet. This condition is characterized by increased pressure in the bladder during filling, and individuals may have a decreased sensation of bladder fullness, leading to a sense of urgency and an inability to hold urine.

- OAB Causes

- Uncertain predisposing factors

- Voiding against urethral obstruction

- A habit of low-volume voiding

- Lower sensory threshold

- Sensory urgency

- Diet – bladder irritants and fluid restriction

Overactive bladder (OAB) is a specific form of urge incontinence, where individuals experience urinary urgency, and increased daytime and/or nighttime frequency of urination without any detectable underlying disease or infection. It is prevalent in about 12% of both men and women and becomes more common with advancing age.

- Causes of Urge Incontinence

- Urinary tract infections, cystitis, bladder tumor, stones, irritation (fluids & diet)

- Decreased sensation of fullness

- Neurologic sensitization and dysfunction

- CVA

- Immobility

- Dementia

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Parkinson’s

- Spinal cord tumor or lesions

The exact cause of urge incontinence and OAB is not always clear, but it could be related to voiding against urethral obstruction or low-volume voiding patterns, leading to a lower sensory threshold for bladder fullness. Other factors like dementia, Parkinson's, UTIs, tumors, stones, detrusor hyperactivity, or bladder contractility impairment could also contribute to this condition.

Mixed Incontinence

- Combination of urge and stress urinary incontinence, often associated with the elderly patient

- Most common type of incontinence in SNF

There is also a mixed type of incontinence, which is quite common, especially among women. Mixed incontinence is a combination of both stress and urge urinary incontinence, presenting a challenge for those affected. It's important to note that urge incontinence, similar to stress incontinence, can also be effectively addressed with electrical stimulation if necessary. Both types of incontinence involve failures to store urine properly and may involve some level of sensory impairment. These issues are frequently encountered in skilled nursing settings.

Overflow Incontinence

- Any involuntary loss of urine associated with the overdistention of the bladder (automatic response by the body to protect the kidneys)

- Overflow incontinence occurs when the bladder is allowed to become so full that it simply overflows.

Overflow incontinence is, as it sounds, a failure to empty the bladder properly. In this type, individuals don't feel the need to urinate, and the bladder ends up overflowing, resulting in small amounts of leakage.

- Causes of Overflow Incontinence

- Outlet obstruction

- Enlarged prostate

- Fecal impaction

- Diabetes

- Heavy alcohol use

- Decreased nerve function

- Weak detrusor

- Peripheral neuropathy

- Outlet obstruction

This can be caused by bladder weakness or a blocked urethra that hinders normal emptying. It is more commonly observed in men, especially if there's an enlarged prostate causing the blockage. Women can also experience this condition due to bladder weakness or certain medical conditions like diabetes or decreased nerve function.

A post-void residual (PVR) test would reveal a full bladder in these individuals, but they lack the sensation of needing to empty it, leading to involuntary leakage. An appropriate intervention for them would be the double void approach.

Various factors can cause overflow incontinence, including medications, diabetic neuropathy, low spinal cord injury, fecal impaction, constipation, and peripheral neuropathy.

Functional Incontinence

- Urinary leakage associated with inability to toilet because of impairments of cognitive and/or physical functioning, psychological unwillingness, or environmental barriers

- Functional incontinence occurs when one cannot get to the toilet or get a bedpan when needed

- The urinary system may work well, but physical or mental disabilities or other circumstances prevent normal toilet usage

Functional incontinence occurs when individuals have a normal urinary system, but face barriers that prevent them from accessing the toilet or appropriate facilities for voiding. This type of incontinence is often related to cognitive, communication, or physical impairments that hinder the person's ability to communicate their needs or physically reach the toilet.

- Causes of Functional Incontinence

- Most common = STAFF

- Impaired mobility

- Severe dementia

- Communication difficulties

- Depression

- Hostility

- Caregiver, toilet and/or toilet substitutes unavailable

Various factors can contribute to functional incontinence, such as impaired mobility, dementia, communication difficulties, the use of physical restraints, musculoskeletal dysfunction, visual impairment, fear of falling, poor lighting, clothing management difficulties, and environmental barriers like narrow doorways or inaccessible facilities.

Addressing functional incontinence requires a comprehensive approach involving occupational therapy, physical therapy, speech therapy, and nursing to identify and address the underlying barriers and provide appropriate interventions and support to help individuals achieve continence and improve their quality of life.

Iatrogenic Incontinence

- Diuretics

- Sleeping pills/sedatives

- Decongestants

- Anti-depressants

- Cold remedies

- Parkinson’s meds

- Pain meds

- Blood pressure

Iatrogenic urinary incontinence is related to medications, and it's an important consideration, especially for seniors who often take multiple medications. Certain drugs can contribute to urinary incontinence by affecting the urinary system in various ways.

For instance, diuretics increase urine production, leading to a fuller bladder and potential leakage. Sleeping pills and sedatives relax the muscles, including those involved in bladder control, which can reduce the awareness of the need to void. Decongestants, on the other hand, can tighten the pelvic floor muscles, making it difficult to void properly.

Antidepressants may cause overflow incontinence, as they can relax the bladder too much, resulting in urine overflow. Cold remedies, pain medications, and certain blood pressure medications can lead to urinary retention, making it challenging to empty the bladder fully.

Additionally, medications used to manage Parkinson's disease can increase the likelihood of overflowing incontinence due to their impact on the bladder and its control.

Neurogenic Incontinence

- Symptoms range depending on site of neurologic insult

- Detrusor underactivity/overactivity

- Sphincter underactivity/overactivity

- Loss of coordination with bladder function

The final type of urinary incontinence is neurogenic in nature, and its presentation varies depending on the location and extent of the neurologic insult. This type can manifest as detrusor underactivity or overactivity, as well as sphincter dysfunction and lack of coordination between these structures.

- Causes of Neurogenic Incontinence

- Spinal cord injury

- Multiple sclerosis

- Peripheral nerve lesions due to:

- Diabetes mellitus

- Tabes dorsalis

- Herpes zoster

- Herniated lumbar disk disease

- Radical pelvic surgery

Neurogenic urinary incontinence can be attributed to conditions such as spinal cord injuries, diabetes, herniated lumbar discs, among others.

- Other factors

- Delirium or confusional state or diet

- Atrophic vaginitis/urethritis

- Pharmaceuticals

- Psychological disorders, especially severe depression

- Endocrine disorders, hyperglycemia or hypercalcemia

- Restricted mobility

- Stool impaction

Additionally, various factors may contribute to this type of incontinence, including the use of pharmaceuticals, restricted mobility, stool impaction, and endocrine disorders, like thyroid conditions. Hormonal imbalances, such as a lack of estrogen, weakness, surgeries, and the effects of childbearing, are also among the potential causes. As healthcare professionals, it is essential to identify the specific type of neurogenic incontinence to develop targeted and effective treatment plans.

Other Causes of Urinary Incontinence

- Urinary tract or vaginal infections

- Postmenopausal – lack of estrogen

- Constipation or fecal impaction

- Weakness of certain muscles

- Blocked urethra d/t enlarged prostate

- Disorders involving nerves or muscles

- Some types of surgery

- Childbearing

- SCI

Determining Type of Incontinence

During our occupational therapy evaluation, it is crucial to determine the type of incontinence the individual is experiencing to tailor our interventions effectively. We can start by asking specific questions to identify the type of incontinence.

- Stress Incontinence

- Does the patient leak while laughing, coughing, sneezing, lifting, or doing physical activity?

- Has the patient had a prostatectomy?

- Does the patient urinate during sex?

- Did the patient have vaginal deliveries?

- Did the patient have a hysterectomy?

For stress incontinence, we may inquire if they experience leakage during activities like laughing, coughing, or sneezing and if they notice urine leakage during sexual intercourse.

- Urge Incontinence

- Does the patient have a strong urge to urinate but is unable to make it to the restroom?

- Does the patient strain to urinate?

- Does the patient have large accidents?

- Does the patient urinate a lot at night?

- Is the patient urinating frequently?

For urge incontinence, we can ask about the frequency of sudden, strong urges to void and if they have accidents, especially at night.

- Functional Incontinence

- Does the patient have arthritis? Fatigue? Weakness? Seem depressed?

- Does the patient have dementia?

- Does the patient have trouble removing clothes? Walking? Walk too slowly?

- Does the patient have accidents early in the morning?

Functional incontinence may be explored by assessing their ability to manage clothing, mobility issues like arthritis or trouble walking, and if they have difficulty reaching the restroom on time due to cognitive or physical limitations.

- Overflow Incontinence

- Has the patient injured the spinal cord? Or issue with nervous system?

- Does the patient have diabetes?

- Could he have an enlarged prostate?

- Had surgery that traumatized urethra?

- Could the patient be constipated?

- Tenderness over the pubic bone?

- Signs of an Enlarged Prostate

- Difficulty getting stream started

- Slow, weak, or interrupted stream

- Frequent voiding small amounts

- Pain or burning with voiding

- Voiding at night

- Urgency

- Incomplete emptying

- Incontinence

For overflow incontinence, we may look into their medical history, such as diabetes or prostate-related issues, and check for any tenderness or discomfort over the pubic bone, which could indicate an enlarged prostate.

By gathering this information and conducting a thorough assessment, we can better understand the underlying causes of their incontinence and develop appropriate interventions to improve their quality of life and functional independence. As occupational therapists, we play a vital role in addressing the multifaceted aspects of incontinence and its impact on daily activities, working in collaboration with other healthcare professionals to provide comprehensive care.

Average Bladder Function

Average Function

- Average Bladder Capacity:

- Younger Adult - 500-600 cc or 16.6-20 fluid oz. (2–2 ½ cups of fluid)

- Elderly – 200–400 cc or 6.6–13.3 fluid oz. (3/4–1 ¾ cups of fluid)

- Average # Voids/Day:

- Younger Adult 4-7 times / 24hrs

- Elderly 5–8 times / 24hrs

As we age, bladder function undergoes changes that can impact urinary continence. The elderly bladder may not distend as much as a younger one, leading to reduced holding capacity. While a healthy person can typically hold their urine throughout the day without issues, seniors may have a decreased ability to do so. When they feel the need to go, it may be urgent, and it's essential to recognize and respond to their needs promptly.

- Nocs:

- Younger Adult - Seldom or 1 times

- Elderly - 1 to 2 times

- 24 Hour urine output

- Younger Adult – 1000-5000 cc or 33.3

- 166.7 fluid oz. (4.16–20.8 Cups)

- Elderly – 1000–2000 cc or 33.3

- 66.7 fluid oz. (4.16–8.3 Cups)

- Younger Adult – 1000-5000 cc or 33.3

Frequent trips to the restroom, especially more than twice per night, known as nocturia, are not typical for healthy individuals. However, this can be a common occurrence among the elderly, affecting their sleep and daily routines. Additionally, as we age, urine output naturally decreases, and certain diseases or medications can further lower it. Seniors may be prone to reducing fluid intake to avoid incontinence, but this can lead to other health complications.

- A healthy person’s bladder can usually be emptied voluntarily prior to sensory awareness, defined as voluntary control.

- Time from initial urge until bladder reaches capacity is usually 1-2 hours.

A healthy person's bladder can be voluntarily emptied before sensory awareness, which means they can urinate on command for various situations, like lab tests. However, elderly individuals may not have the same level of voluntary control over their bladder, making managing continence more challenging for them. Furthermore, the time from feeling the initial urge to void until the bladder reaches its full capacity is typically around one to two hours, and this can vary among seniors.

Post-Void Residual

- PVR (Post Void Residual) or the urine left in the bladder after toileting can be assessed by a straight catheter or a bladder scan. WNL < 100cc or < 50cc; more = retention

It's crucial to recognize the significance of post-void residual (PVR), which is the amount of urine remaining in the bladder after toileting. PVR can be measured using a bladder scan or a straight catheter. In a healthy individual, the normal PVR should be zero, indicating that the bladder has emptied completely.

However, concerns arise when the PVR is higher, typically starting to become concerning when it exceeds around 100 CCs. It's essential to consider factors such as age, actual bladder capacity, and any underlying disease processes when evaluating the significance of the PVR measurement. For instance, if someone has a large bladder capacity, a small amount of PVR might not be alarming. But if the bladder capacity is low, even a relatively small PVR can become a matter of concern.

Ultimately, the goal is to have as close to zero PVR as possible. Ensuring that the bladder fully empties during each voiding helps to minimize the risk of urinary retention and associated complications.

Fluid Intake Requirements

- Fluids come from food and liquid intake

- Thirst sensation may be decreased in older adults - offer fluids throughout the day

- Dehydration is serious and prevalent with LTC

Fluid intake and hydration are critical considerations in the care of older adults. As people age, the sensation of thirst tends to decrease, making it essential to proactively offer fluids to seniors, both food and beverages. Dehydration is a prevalent and serious concern among the elderly, so encouraging and facilitating adequate fluid intake is crucial.

As occupational therapy practitioners, we may play a role in helping seniors with diet modifications that support their hydration needs. It's important to identify and offer alternative food and drink options that are not irritating to their bladder or overall health. Restricting fluid intake is not an effective strategy to manage urinary incontinence or other health conditions; instead, promoting a balanced and appropriate fluid intake is the key.

Dietary Irritants and Fluids

- Many foods can irritate the lining of the bladder

- Eliminating dietary caffeine can help this

- However, limiting overall fluid intake is not effective for managing UI.

- Substituting bladder irritants:

- Water

- ½ and ½ water to juice

- Decreasing the amount of times coffee is served

Bladder irritants can play a role in exacerbating urinary incontinence in some individuals. While there is no specific diet that can cure incontinence, certain foods and beverages, such as citrus, artificial sweeteners, caffeine, and alcohol, have the potential to irritate the bladder lining and contribute to the condition. Managing and avoiding these irritants can be beneficial for some individuals.

As we age, there are changes in bladder function that can lead to an increase in frequency and nighttime bathroom visits despite a decrease in overall urine output. The ability to store urine diminishes with age, resulting in a reduced bladder capacity and a greater sense of urgency to urinate. Younger individuals may have stronger musculature and a greater bladder capacity, allowing them to hold urine longer. In contrast, seniors may experience more frequent urges to urinate due to reduced storage capabilities.

Constipation can also be a contributing factor to bladder control issues. Addressing constipation through dietary adjustments, such as increasing fiber intake to add bulk to the stool, may help alleviate related bladder problems.

Bladder Irritants

- Artificial sweeteners/colors

- Alcoholic beverages

- Apples

- Apple juice

- Artificial sweetener

- Beer

- Caffeine

- Carbonation

- Chilies/spicy foods

- Citrus fruits/juices

- Coffee (including decaf)

- Colas

- Corn syrup

- Cranberries

- Honey

- Grapes/grape juice

- Guava

- Milk/dairy

- Peaches

- Pineapple

- Plums

- Strawberries

- Sugar

- Tea

- Tomatoes

- Vinegar

- Vitamins B and C

- Wine

The above list is some examples of bladder irritants.

Substitutions

- Low-acid fruits

- Tea substitutions

- Vitamin substitute

- Juice substitutes

- Coffee substitutions

- WATER!! Water does not irritate

When considering urinary health and preventing irritation, the best substitution is indeed water. Water does not irritate the bladder and is a safe and gentle option for maintaining hydration. It is crucial to avoid adding artificial sweeteners or other irritants to water, as this can negate its beneficial effects on bladder health. Staying hydrated with water remains a key strategy for supporting overall urinary function and preventing potential irritation.

Vitamin C- These Do Not Irritate the Bladder

- Asparagus

- Avocado

- Broccoli

- Brussels sprouts

- Cabbage, raw

- Cantaloupe

- Cauliflower

- Green pepper

- Greens (collards, kale)

- Lima beans

- Mango

- Papaya

- Peas

- Raspberries

- Spinach

- Squash

- Strawberries

- Turnips

- Vitamin C fortified cereal

Vitamin C is essential for our health, but for individuals who find citrus irritating to their bladder, there are alternative sources for obtaining vitamin C without causing bladder irritation.

Calcium- These Do Not Irritate the Bladder

- Broccoli

- Clams

- Collards, cooked

- Farina

- Oysters

- Salmon

- Sardines

- Self-rising flour

- Soybeans, cooked

- Turnip greens, cooked

- Ice milk

Likewise, calcium is essential, but for those who experience bladder irritation from dairy products, there are other dietary sources available to meet calcium needs.

Prescribed Medications

- Oxybutynin (Ditropan) and Tolterodine (Detrol) -- urge incontinence

- Pseudoephedrine (Sudafed) -- stress incontinence

- Imipramine (Tofranil) -- urge or stress incontinence

- Tamsulosin (Flomax) or Terazosin (Hytrin) -- overflow incontinence

As for prescribed medications, they can be helpful in managing different types of urinary incontinence. For instance, Ditropan or Detrol can assist individuals with urgent incontinence or hyperactive bladder by reducing muscle spasms and improving control. Sudafed, although it may cause urine retention, could potentially be beneficial in treating stress urinary incontinence when there is a failure to store urine properly. Tofranil, an antidepressant, can increase bladder volume and improve control of urine flow. Flomax or Hytrin can improve urinary flow, especially for those with an enlarged prostate. However, it is essential to remember that these medications should be prescribed and managed by a physician.

Evaluation

Nursing and MD Evaluation

- History

- Detail of Symptoms and Associated Factors

- Physical Exam

- Urinary Analysis and PVR

The evaluation of urinary incontinence involves an interdisciplinary approach with contributions from nursing, physicians, and occupational therapists, among others. Various assessments are performed to gather comprehensive information. These include medical and neurological evaluations, genital urinary assessments, and physical examinations. Estrogen levels may be considered for women experiencing incontinence related to hormonal changes.

Detailed symptom analysis, including timing, precipitants, and bladder diary data, helps understand the nature of the condition.

Urinalysis and blood tests are conducted to identify any signs of infection or underlying medical conditions that could be affecting bladder function. In some cases, specialized tests like cystograms may be used to examine the bladder more closely.

Additionally, post-void residual (PVR) measurements are taken to determine if the bladder is emptying properly.

Patient Questionnaire

- Gender

- Do you ever leak urine when you don’t want to?

- When did you notice the onset of urinary leakage?

- Did the urine leakage begin after trauma?

- Did you leak urine as a child? Until what age?

- How does UI affect you?

- How often do you leak urine?

- When does leakage occur?

- Do you wake up at night to urinate?

- Do you awaken as you are losing urine?

- When you leak urine, how much leaks?

- Do specific activities cause you to leak urine?

- Do you ever have trouble getting to the toilet on time or have accidents while removing your clothes prior to urination?

- Do you realize that you are losing urine as it runs out?

- How often do you normally urinate?

- Once your bladder feels full, how long can you hold it?

- Can you stop the flow of urine at will?

- Do you know when you have to go?

- Do you have any of the following?

- Difficulty starting a stream

- Straining

- Very slow stream or dribbling

- Discomfort or pain

- Burning

- Blood in the urine

- Do you feel that you completely empty?

- Do you leak urine while having sex?

- Current method of managing urinary leakage?

- How much fluid do you take in within a 24-hour period?

- Do you ever have uncontrolled loss of stool?

- Current medications

These next slides provide a comprehensive set of questions to ask during the evaluation of urinary incontinence. Understanding the specific details of the individual's condition is essential for developing an effective treatment plan. Some of the questions include when and how often the leakage occurs, the amount of leakage, the triggers for leakage during certain activities, and the individual's ability to hold urine. Assessing their awareness of the need to urinate and their ability to stop the flow of urine is crucial.

Additional inquiries cover any discomfort or abnormalities experienced during urination, the presence of blood or burning sensations, and any issues related to sexual activity. The current management methods used by the individual, such as medications or assistive devices like bedside commodes or urinals, are also important to consider. Understanding the person's medication regimen is critical as it may reveal potential interactions or side effects contributing to their incontinence.

As occupational therapists, this detailed assessment helps us gain insight into the individual's specific challenges and needs, allowing us to create personalized interventions that address the underlying causes and improve their overall bladder function and continence.

Medical History

- Congestive heart failure

- Stroke

- Depression

- Glaucoma

- Cancer

- Dementia

- Diabetes

- Heart arrhythmia

- Parkinson’s disease

- Fainting

- Prior CNS trauma/surgery

- Dizziness

- Other neurological disorders

Understanding the individual's medical history is crucial for a comprehensive evaluation. While we may not conduct a full medical history ourselves as occupational therapists, collaborating with other healthcare professionals, such as nurses or physicians, can provide us with essential information about the person's overall health and any conditions that may be contributing to their urinary incontinence.

For example, medical conditions like glaucoma could impact the person's ability to see and navigate their environment, potentially leading to difficulties in finding the bathroom or detecting urine on the floor. Neurological conditions like Parkinson's disease can affect bladder control due to nerve impairments.

Prior Genitourinary History

- Rheumatic heart disease

- Bladder tumor

- Multiple vaginal deliveries

- Recurrent UTI

- C-sections

- Pelvic irradiation

- Bladder suspension

- Urethral stricture/dilation

- Vaginal hysterectomy

- Prostate surgery

- Abdominal hysterectomy

Tumors or prior genital and urinary history, such as vaginal deliveries in women, may provide insights into the type of urinary incontinence the individual is experiencing.

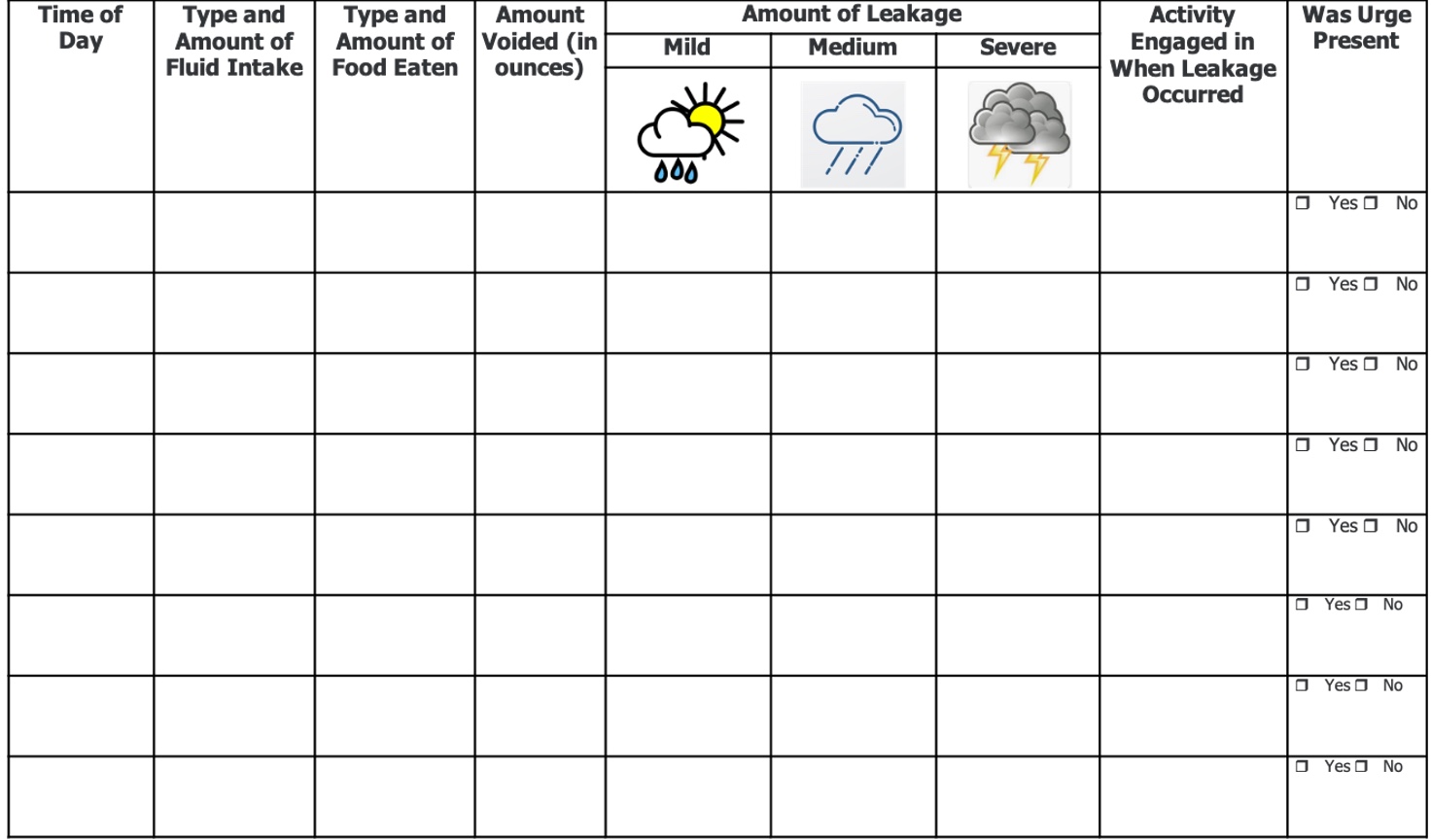

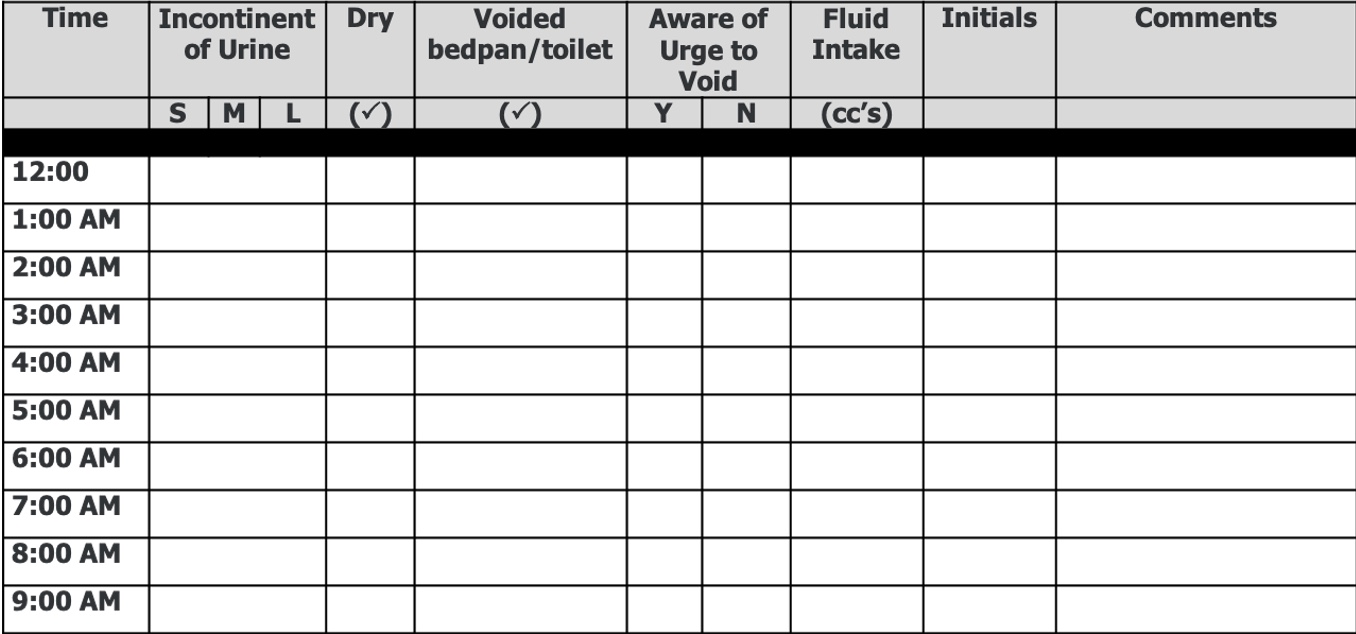

24-Hour Voiding Diary

- Purpose: To obtain accurate, baseline bladder health information of the resident receiving skilled therapy for UI

- Standard of care is 3 days – 7 for outpatients

- Administered three times (preferably throughout)

- At Initial Evaluation for – baseline