Carolyn Baum, A Life of Commitment and Achievement in Occupational Therapy

Carolyn Baum is one of the most prominent leaders in occupational therapy for the past 40 years. She has advanced the profession through her long history of service to the American Occupational Therapy Association as president in 1982–1983, and 2004–2007, Chair of the AOTA Research Commission, and as the presenter of the Eleanor Clarke Slagle Lectureship in 1980. In addition, as an occupational therapy scientist and author, she has developed and tested new theories and measures, including the Person-Environment-Occupation-

In summary, Carolyn Baum, through her dedication and commitment to excellence, has been an inspiration to the occupational therapy profession. On a personal note, I have admired Carolyn for many years, and I do appreciate our friendship.

Franklin Stein, PhD, OTR/L, FAOTA

Contributing Editor

Salute to OT Leaders Series

20Q: Legacy of a Cognitive Researcher

PhD (HON), OT, FAOTA

History

Learning Outcomes

After this course, readers will be able to:

- Name 3 occupational therapy cognitive assessments.

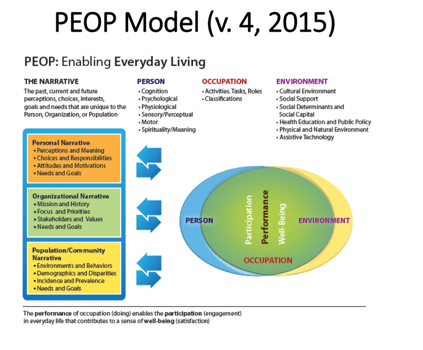

- Describe the components of the PEOP model.

- Describe occupational therapy cognitive research and future trends.

1. Where did you grow up, and where did you go to primary school?

I was born in Chicago in 1943, and my father, Gibson Henry Manville, was a conductor on the Great Northern Railway for the Pullman Car Company. He worked on the Empire Builder, which was at that time the Great Northern’s premier Chicago-to-Seattle train. When I was six years old, my parents moved back to my mother's hometown in Winchester, Kansas, a farming community with a population of 400. I started school in first grade with 18 classmates in an eight-room schoolhouse, and I graduated from Winchester High School with those same people.

2. How did you become interested in occupational therapy?

I became interested in occupational therapy after visiting my cousin in Tacoma, Washington. She was the assistant director of special education for the Tacoma public school system, which was one of the first school districts in the country that mainstreamed children with disabilities into regular classrooms.

During the course of my week-long visit, my cousin encouraged me to observe the occupational therapist who was working with these children in a resource room designed to help them succeed in the classroom. I knew then I wanted to be an occupational therapist. The only challenge was that my parents wanted me to become a homemaker.

Career

3. Where did you obtain your professional degree in occupational therapy?

I had to convince my parents that I would be a better homemaker if I had a degree in home economics. They agreed, so I enrolled at Kansas State University. My high school was not a college preparatory school, so I had an adjustment period to the rigors of higher education. After my freshman year, I gained the confidence to transfer to the University of Kansas, switch my major to occupational therapy and earn my bachelor’s degree in 1966.

I went on to earn a master’s degree in health management from Webster University in St. Louis in 1979 and a doctorate in social work from the George Warren Brown School of Social Work at Washington University in St. Louis in 1993.

4. How did your education shape your occupational therapy career?

The occupational therapy department at the University of Kansas was located in the School of Fine Arts. I took classes with the art majors such as ceramics, weaving, silversmithing, screen printing, and other graphic processes. In the occupational therapy curriculum, I took woodworking and learned to knit, crochet, and make fishing flies. These modalities taught me the skills needed to use arts and crafts to help people gain the function to improve their daily lives. Of course, I learned occupational therapy principles and a basic introduction to the health conditions that required occupational therapy services.

Once I started working as an occupational therapy manager, I needed to gain management skills. I took an evening course of study in health management to have the foundational knowledge to build clinical programs. I also took courses in leadership. An elective course on the sociology of health served as my introduction to health disparities and shaped my early understanding of social capital. Another elective was a course on values clarification, and this content was essential to my personal and professional growth. In this class, I had to identify what I wanted to be remembered for, which is: “She made a difference in the lives of people with disabilities.” This value has shaped all of my activities, teaching, program development, research, and policy.

I engaged in doctoral studies because I wanted to answer questions about how to support people with cognitive loss to live their occupational lives as they age with Alzheimer's disease. In the 1990s, this led me to develop occupational therapy assessments that would demonstrate what people with cognitive loss can do. I worked with colleagues and my PhD mentor to develop the Activity Card Sort, the Kitchen Task Assessment, the Functional Behavior Profile, and the Executive Function Performance Test.

The Activity Card Sort is considered one of the most practical and accurate measures of occupation. It an interview-based tool that allows clients to describe the full range of their meaningful activities and their engagement with each. Using photo cards depicting various activities, clients are able to communicate their occupational history to their clinician so that, working together, they can build routines of healthy activities.

The Functional Behavior Profile is a measurement tool to guide placement decisions with Alzheimer’s disease and other neurological conditions. The measure provides the clinician with a tool to identify the nature and extent of the behavioral capabilities of people experiencing cognitive loss and the problems their caregivers will face if they choose to manage their loved ones at home. The profile yields information so the clinician can plan treatment based on how much supervision their family member needs.

The Executive Function Performance Test is a performance-based standardized assessment of cognitive function while completing a series of tasks. It determines which executive functions are impaired, what capacity there is for independent functioning and the amount of assistance needed for task completion. The test examines four basic tasks that are essential for self-care and independence: simple cooking, telephone use, medication management, and bill paying.

Information about these measures can be obtained at https://www.ot.wustl.edu/ under the assessments tab.

5. Who were your mentors?

My first mentors were my aunt and uncle, Ida and Dwight Newberg, who saw my potential for leadership at a young age. They visited Kansas every other year, and their stories of living and traveling in faraway places helped me understand that I could have those same experiences one day, but I would have to have a plan, as most of my family and friends were preparing to live in our small community.

Professionally, Mae Hightower-Vandamm, a former president of the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA), mentored me, as did Wilma West and Mary Riley, who were prominent figures in occupational therapy. Mary Riley invited me to come to California several times to meet with her. She had stacks of books put aside for me to read (I had already read about half of them), and we would sit and talk for hours about occupational therapy and how to apply the knowledge we were learning in our readings. She was a wonderful mentor and friend throughout my career.

Anne Grady and Ellie Guilfoyle from Colorado also mentored me and helped prepare me for my Eleanor Clarke Slagle Lecture. They were both highly influenced by developmental psychologist Jean Piaget. Our conversations often centered on his concepts of assimilation and accommodation. To this day, I integrate those principles into my thinking of and planning for change. I would also add Florence Crowell as a mentor. She recognized and supported my growth for professional leadership. I was very young when she literally pushed me into national leadership.

As a scientist, my most important mentor was Leonard Berg. He was the clinical neurologist who led the memory and aging project at Washington University. His work founded one of the first Alzheimer’s research centers, where his studies continue. He observed that I had a unique perspective—one that focused on what people can do, rather than looking only at a person’s limitations. He invited me to work with him, and it was the beginning of my science.

6. How did your fieldwork experiences influence your career?

My fieldwork gave me a great opportunity for personal growth and fostered my independence. My first trip alone was to my fieldwork in 1964; it was also my first flight, first time living alone, and first time applying what I had learned to help people. I went to study at Greystone State Hospital in New Jersey, an institution for the mentally ill with nearly 5000 patients. I worked with the incarcerated teenagers. Here is where my occupational therapy skills and 4-H experience from living in a farming community came together. I found that these teenagers lacked skills, had no hobbies, and did not know their occupational selves. I helped them organize a talent show and sew their costumes. I found guitars and recorders, and they learned to play music. At the end of the 12 weeks, we put on our talent show. When I took the teenagers back to their ward after the performance, the night staff did not know me, and they locked me in the ward. It took several hours before Lucille Boss, the head of occupational therapy, was able to come to get me. The lessons I took away from that fieldwork were that people have potential and want to do things; they only need the tools and someone to enable their engagement to learn skills. These were powerful lessons for me to learn, and I found that they relate well to the developmental learning theory of psychologist Lev Vygotsky.

7. What was your first position in occupational therapy?

My first clinical position was at the University of Kansas (KU) Medical Center. There, I started a cardiac rehabilitation program, and within six months presented my first paper. After 18 months on the job, I left KU and went to build the physical rehabilitation occupational therapy program at Research Medical Center hospital in Kansas City. After six months, the occupational therapy director left and convinced the administration that I could serve as the director. I went on to become the director of all of the rehabilitation services at Research Medical Center.

8. How did you become interested in hospital management and administration?

When I worked at Research Medical Center, I took American Management Association courses offered by the hospital. Hospitals were just starting to use the management training approach for their leaders. I learned how critical it is to build a supportive infrastructure and to use guiding principles.

9. How did you decide upon a specialty area in occupational therapy?

As I mentioned, my early work with Leonard Berg sparked my interest in the cognitive capacities of older adults. Ever since then, my research has centered on enabling adults with neurological problems to live independently. For the past 5 years in a grant led by Allen Heinemann from Northwestern University I had a wonderful opportunity to study cognition, daily life experiences and the environment in people with stroke, spinal cord injuries and traumatic head injuries with colleagues from The Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago and the University of Michigan. This work has led to additional measurement work to establish functional cognition as a central construct that must be addressed by occupational therapy to help people live lives when mild cognitive impairment is interfering with their ability to engage with family, work and community activities.

I published my first manuscript in 1969; it was a paper on the occupational therapy audit. I developed the audit as a management tool. It was published in the American Journal of Occupational Therapy.

Achievements

10. How would you summarize your contributions to the profession of occupational therapy up to this point in your career?

My major contributions to the profession are my research in cognitive impairment and my leadership and service to national, state and local occupational therapy associations.

In addition to building the science of occupational therapy, my contributions include developing the Person-Environment-Occupation-Performance (PEOP) model and assessments (the Activity Card Sort, the Kitchen Task Assessment, the Functional Behavior Profile, and the Executive Function Performance Test).

I was also involved in two major rehabilitation policy initiatives and served on the National Institutes of Health (NIH) committee that wrote the rehabilitation plan for Congress that implemented the National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research. I also served on the Institute of Medicine committee that wrote the report “Enabling America for Congress.”

One of my achievements is the development of the Occupational Performance in Neurorehabilitation Laboratory at Washington University. The major focus of the laboratory is to understand the factors and effectiveness of interventions to support the daily occupations of older adults as they seek to live as independently as possible. The assessment methods include performance-based and behavioral measures of activity, executive function, social support and quality of life. Intervention methods use cognitive behavioral activity-based approaches. The results provide a quantification of how people engage in instrumental leisure and social activities, how their activities are different from persons with other types of disabling conditions and those without disabilities, and how they are changed by intervention. The impact is better methods of helping persons with chronic neurological impairment improve their function, participation, and health. Collaborators are from neurology, psychology, speech-language pathology, physical therapy, and social work.

11. What were your major achievements as president of AOTA 1982-83, 2004-07?

I served as AOTA president from 1982 to 1983 to fulfill Mae Hightower-Van Damm’s term when she stepped down as president. My major achievement during that term was to change the bylaws and to help build an infrastructure for strategic planning.

My major achievement in my second term as president from 2004 to 2007 was leading in the development of and building the implementation strategies to implement AOTA’s Centennial Vision, which was a strategic initiative to guide the profession into its second century. At the time it was written, we had 13 years to lead the profession to accomplish the activities to support the vision, and each president that followed transitioned with the vision as central to their term of office. It became a chain of leadership that has led to strengthening the profession, and now there is a new vision for 2025.

12. Discuss the Person-Environment Occupational Performance (PEOP) model.

Charles Christiansen and I were working on a textbook (later Julie Bass joined us), and we started discussing how there needed to be a framework to accommodate the new knowledge being generated in the profession. Our founders had put an emphasis on occupation and engagement, but we wanted to create a specific lens so occupational therapists could view the environment, community accessibility, social supports, and policy as they all factor into supporting what people want to do and engage in as an occupational being.

The PEOP model organizes knowledge so that the occupational therapist has a unique perspective to view the environment on a personal, population, and organizational level for a client. It was ahead of its time.

Baum, C. M., Christiansen, C. H., & Bass, J. D. (2015). The Person-Environment-Occupation-Performance (PEOP) Model. In C. H. Christiansen, C. M. Baum, & J. D. Bass (Eds.). Occupational Therapy: Performance, participation, and well-being, Fourth Edition (pp. 49-55). Thorofare NJ: SLACK Incorporated.

13. Describe the book, “Occupational Therapy: Overcoming Human Performance Deficits,” which is in its fourth edition.

The first edition, published in 1991, presented a wide spectrum of ideas and theories of human and occupational performance into the PEOP framework. We defined occupational therapy in relation to the PEOP model and provided descriptions of assessment and intervention strategies that explain and illustrate the application of the PEOP to actual occupational therapy practice.

In 1997, the book was revised and renamed for its second edition to become "Occupational Therapy: Enabling Function and Well-Being.” Significant additions to the second edition include a chapter on the measurement of outcomes in occupational therapy from clinical and program evaluation standpoints, chapters on the meaning of occupations and on health promotion and prevention of disability, as well as case studies included within chapters. A greater focus was placed on combining theoretical, assessment, and intervention information in individual chapters addressing components of performance. New expert contributors, including occupational therapists and rehabilitation scientists, gave this edition a more international perspective than the previous version. In 2005 the 3rd addition was organized to have a consistent structure and offered students a comprehensive review of the knowledge to support occupational performance.

The book is now in its fourth edition, and it not only highlights the model and how it can be applied at the person, population, and organizational level, but it also includes chapters of all of the components of the model written by leading scholars in the field. The book offers the educator and the student the opportunity to use knowledge of each of the components of the model to form an occupational lens that prepares the student to address the distinct value of the field.

14. What were your experiences as a visiting professor, especially in Australia?

It was a privilege to be a visiting professor at the University of Queensland in Australia in 2008. There, I got to know Sylvia Rodger, who was using the PEOP model with children. Her work in cognition with children was similar to my work with older adults. I also traveled to Melbourne and got to know Leeanne Carey, which has resulted in an active collaboration to link our understanding of the brain to the everyday lives of those with stroke.

I also have long-standing relationships with the University of Haifa and many colleagues in Israel. My first colleague was Noomi Katz and her students as we were all building measurement tools to address cognition in the daily lives of people. Naomi Josman and her faculty have also been major partners in exploring cognition. One of my nicest professional experiences was when I received an honorary doctorate at the University of Haifa. I was particularly honored to join in the history of people like Henry Kissinger, President Carter, and other international leaders who had received that award.

Research

15. What impact do you think your research has had in shaping the practice of occupational therapy?

Occupational therapists have always studied neuroscience or neuroanatomy because they knew the brain supports function, but the concentration was on sensory and motor factors. I think I have brought a greater understanding of cognition to support the occupational lives of people. The cognitive part of brain function is central to the independence and problem solving that is necessary for people to have autonomy and control of their lives. I’ve made that a priority in my research, and I hope it has had an impact.

16. What do you see as the major areas that occupational therapists should be involved in research?

It is our mandate to understand the factors that enhance or limit people's occupational daily lives: brain activity, behavior, performance, and participation. They all have to exist, and we work along that continuum, but a major focus area should be developing rehabilitation and self-management strategies to help people live their everyday lives.

In regard to occupational performance, we should ask what factors contribute to occupational performance such as motor skills, cognition, sensory factors, environmental factors, social support, and families and family resources. All of these are impacted if there has been an occupational disruption. I would like occupational therapists to ask questions that will help people achieve their occupational performance and avoid occupational disruption. Society needs our perspective and our skills.

Future of OT

17. How do you foresee the future of occupational therapy in your specialty area?

Well, if you call my specialty area functional cognition, I would say that it is in the early stages of development. There is major work coming, and I hope that the next generation of clinicians will look at the sensory input, cognitive processing, and motor output as they focus their work on improving the everyday function of their clients.

I think Jean Ayres was our first occupational therapy scientist in the respect that she was looking at sensory integration long before cognitive science became a field. She was ahead of her time, and if she were still alive, she would be challenging us to use cognition, motor, and sensory knowledge emerging from neuroscience principles to inform our work.

18. What do you see as the major issues in health care in the United States that are impacting clinical practice in occupational therapy?

We have to first define what clinical practice is, and what clinical practice is not. As a profession, we are very comfortable working in general and rehabilitation hospitals. In the future, clinical practice will have no walls. We need to be contributing to the health of the population as population health is the biggest movement in healthcare today.

Occupational therapists can make major contributions by helping move clients toward active engagement and occupation. Occupational roles foster physical, mental, and cognitive health. We have reframed our practice toward risk management to help people gain the skills to manage the risks associated with developmental delays, chronic diseases, and disabilities.

19. What advice would you give a new graduate student in occupational therapy?

My advice to a new graduate student would be to use their passion for helping people coupled with their knowledge in neuroscience, environmental science, psychology, and occupational science to support people in doing what they need and want to do. Every occupational therapist has a unique perspective in that they can see both the capacities people have and the limitations they face as well as the barriers and facilitators the environment provides. With this knowledge, they will be able to help clients develop their own strategies to manage their health conditions.

20. How do you see the future of the international movements in occupational therapy?

Some of the finest work in occupational therapy is occurring in international environments that do not have the same restrictions as the U.S. on health care. We should be able to use their models and research and incorporate it into our understanding of who we are and what we can do to help people actualize their lives. We are all part of an international community of clinicians and scientists, and as the world faces occupational disruption from health, social, and environmental conditions, we have roles to play at the individual, population, and organizational levels.

In closing, at the end of this course, the reader will be able to name 3 occupational therapy cognitive assessments. Additionally, the reader will be able to describe the components of the PEOP model. Lastly, the reader will be able to describe occupational therapy cognitive research and future trends.

Citation

Baum, C. (2018). 20Q: Legacy of a cognitive researcher. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 4485. Retrieved from www.occupationaltherapy.com