Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Depression After Brain Injury, by Jasleen Grewal, Registered Occupational Therapist, PhD Candidate, University of British Columbia, Julia Schmidt, PhD, BSc (Occupational Therapy).

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to identify the prevalence and factors associated with brain injury and depression.

- After this course, participants will be able to identify the role of occupational therapists in brain injury and depression.

- After this course, participants will be able to identify common treatment options for brain injury and depression, specifically in areas in which occupational therapists can facilitate improvement in depressive symptoms after brain injury.

Introduction

Dr. Schmidt: Hi, everyone. I have been in brain injury rehabilitation since the beginning of my occupational therapy career and have done a lot of cognitive rehab and other types of investigation. You cannot be around brain injury without being around mental health and depression because that is something that comes up all the time for people. Our partnerships with people with lived experience and community partners have led us on a course of further investigations into this topic. Jasleen is going to talk about this at the end of the presentation. Thank you, everyone, and I hope you enjoy the presentation.

Brain Injury

- Acquired and traumatic brain injury1

- Injuries that impact the brain's function

- Examples: stroke, concussion, TBI, substance use-related brain injury

I want to start by giving an overview of brain injury. A brain injury is any injury to your brain, skull, or scalp. This can range from a mild bump or bruise causing a concussion to a more severe impact causing a traumatic brain injury.

An acquired brain injury is an umbrella term that houses the different types of brain injuries. An acquired brain injury is an injury to the brain that is not hereditary, congenital, degenerative, induced by birth trauma, and essentially occurs after birth. The injury results in changes to the brain's neuronal activity, affecting the physical integrity, metabolic activity, and functional ability of the nerve cells in the brain. Examples of acquired brain injury include concussion, TBI, stroke, and substance use-related brain injury, to name a few.

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

- Sudden, external, physical assault damages to the brain1

- Focal damage: confined to one area of the brain2

- Diffuse damage: damage to more than one area of the brain2

We will primarily focus on traumatic brain injury and its relationship to depression. A traumatic brain injury is caused by a sudden external force that alters the brain's function or other evidence of brain pathology. The damage can be focal, which means that it can be confined to one area or more diffuse, meaning that the damage goes beyond one area and impacts different areas of the brain.

Poll: Have you worked with individuals with TBI?

Before I get into the specific content of my presentation, I wanted to ask, "How many of you have worked with individuals who have had a traumatic brain injury, and what is unique about this population?" Some of the answers include impulsiveness, decreased safety awareness, behavioral issues, lack of insight, and memory issues.

Types of TBI

Closed TBI

- Closed brain injury: nonpenetrating injury to the brain with no break in the skull3

- Rapid forward/backward movement and shaking of brain in the bony skull

- Causes bruising and tearing of brain tissue

- Causes: car accidents, falls

Traumatic brain injuries can happen in one of two ways. A closed brain injury or nonpenetrating injury is when there is no break in the skull. A closed brain injury is caused by the rapid forward and backward movement and shaking of the brain inside the bony skull resulting in brain tissue and blood vessel bruising and tearing. Closed brain injuries are usually caused during a car accident, a fall, or sports. Shaken baby syndrome can also cause a closed brain injury.

Open TBI

- Open brain injury: break in the skull3

- Bullet pierces the brain

An open or penetrating brain injury is when there is a break in the skull. An example would be when a bullet pierces through the skull.

Primary and Secondary

- Primary TBI4

- Secondary TBI4

Additionally, there are different types of brain injuries. Primary brain injuries refer to sudden and profound damage to the brain that is considered more or less to be complete at the time of impact. This happens during a car accident, a gunshot wound, or a fall.

Secondary brain injury refers to the changes that evolve for hours or days after the primary brain injury, including a series of cellular, chemical, tissue, and blood vessel changes to the brain that contribute to the further destruction of the brain tissue. A complication of secondary brain injury is that it may go unrecognizable or undiagnosed until many months or even years later. A delay in diagnosis and treatment can cause profound changes to the individual's life before these deficits are addressed.

Some brain injuries are mild, with symptoms that subside in a few hours or days with proper attention. However, some brain injuries are more severe, and the symptoms are more long-lasting. They may last months or even years with permanent and consistent symptoms that need ongoing rehabilitation.

Consequences of TBI

I will briefly go over the symptoms you commonly see after a brain injury, specifically a mild to severe traumatic brain injury. These symptoms are divided into categories. These are not all of the symptoms an individual may experience, but these are some of the common ones that may happen.

Cognitive Changes

- Coma

- Changes in memory, attention, & ability to problem solve

- Confusion

- Decreased awareness of self & others

For cognitive changes, an individual may go into a coma. They may be unable to retrieve memories or make new memories. They may have difficulty focusing, attending to tasks, dividing attention, and problem-solving. They may feel confused and have decreased awareness of themself and others. They may have reduced awareness of their deficits, for example.

Motor Changes

- Paralysis

- Decreased balance and coordination

- Decreased endurance

- Fine motor problems

- Difficulty planning motor movements

- Spasticity

Motor changes after brain injury include paralysis, decreased balance and coordination, decreased endurance, fine motor problems, difficulty planning motor movements, and spasticity.

Perceptual and Sensory Deficits

- Changes in hearing, vision, smell, touch

- Loss of sensation or heightened sensation

- Left or right-sided neglect

- Double vision, lack of visual acuity

Perceptual and sensory deficits include hearing, vision, smell or touch changes, loss of sensation or heightened sensation, and left or right-sided neglect, where they cannot perceive their left or right side. Double vision or lack of visual acuity also may occur.

Communication and language deficits13

Communication and language deficits include aphasia. So the inability to understand speech and the inability to articulate speech. Speech apraxia, which is making inconsistent speech sounds. Functional deficits include difficulties with ADL.

Functional deficits14-16

There can be difficulties with basic daily activities such as bathing, dressing, grooming, et cetera. They may also have difficulty grocery shopping, cooking meals, and taking medication. They may also have problems driving and socializing.

Mental Health

- Apathy

- Decreased motivation

- Emotional lability

- Irritability

- Anxiety

- Depression17

One mental health concern after TBI is apathy, an inability to experience or feel emotions. Decreased motivation, emotional liability, uncontrollable emotional reactions such as crying or laughing in an inappropriate situation, irritability, anxiety, and depression are other symptoms.

Depression

- Mood disorder with persistent feelings of feeling sad, hopelessness, guilt, worthlessness, loss of interest in activities, difficulty sleeping, difficulty concentrating, changes in appetite, and suicidal ideation18,19

Depression is a mood disorder characterized by sadness, hopelessness, emptiness, worthlessness, guilt, and loss of interest in previously enjoyed activities. People may have problems with their sleep, eating habits, and weight changes. People may also have recurrent thoughts about suicide and death, and suicidal ideation may also be present.

Depression and TBI

- About ½ of individuals with TBI experience mood disorders or symptoms of mood disorders20

- Pre-frontal cortex damage

Depression is common after TBI, with about half of individuals experiencing a mood disorder or symptoms of mood disorders post-TBI. These symptoms can be attributed to pre-frontal cortex damage during a TBI, as it is responsible for many executive functions such as attention, flexibility, impulse inhibition, and decision-making.

Additionally, the pre-frontal cortex is involved in emotional responses and is connected to other brain areas responsible for controlling hormones such as serotonin and dopamine. When the pre-frontal cortex is damaged, abnormal functioning can lead to mental health concerns such as depression.

Abnormal function in the pre-frontal cortex may be due to a deactivation of the lateral and dorsal pre-frontal cortexes. These areas control working memory, error detection and correction, and increased activation in the ventral limbic and paralimbic structures, including the amygdala. The amygdala is a structure that regulates emotions such as fear and aggression.

Risk of Depression After TBI

- 25-50% risk to develop depression after TBI within the first year20

- 60% affected within 7 years after injury22-25

The risk for depression after a brain injury is higher than in the general population, with approximately 25 to 50% of persons with a TBI experiencing major depression within the first year of injury. And over 60% of individuals will experience depression within the first seven years of injury. There is a long-term struggle with mood disorders after a TBI. Healthcare professionals, friends, and families should screen individuals with TBI for depressive symptoms.

Timing of Depression after TBI

- Early onset symptoms: neuroanatomic source26

- Later onset: realization of impairment and life-long limitations26

Early onset depression seems to have more of a neuroanatomic source. In contrast, later onset is due to the realization that the individual's difficulties are permanent and their life has changed. It is more of a reaction to their deficits. These differences could influence the interpretation of the timing and methods of depression screenings. Early screenings may capture neurobiological sources of depression, but they may miss the later onset depression.

Depression: Premorbid Conditions

- Pre-injury status

- Addiction

- Social supports

Considering premorbid conditions like addiction, social support, and demographics is essential. If an individual has social support after they experience a TBI, this social support can screen them for depressive symptoms so they can get assessed and treated accordingly. If an individual is experiencing social isolation, they may not have the social supports to screen them for depression, which may go undiagnosed.

Depression: Comorbid Conditions

- Social isolation

- Cognitive challenges

- Physical deficits

- Addiction

- Homelessness

Many comorbid conditions are happening simultaneously, including social isolation and changes in personality, lifestyle, and occupation. Therefore, the person's social connections may change.

Spousal and familial concerns are also common after TBI. Individuals may feel socially isolated because of functional changes. For example, they may have differences in cognition and physical status and cannot participate in conversations or social events.

Addiction is a common comorbid issue in individuals with TBI. More than 60% of TBI patients have a history of drug and alcohol abuse after the initial injury for various reasons. This includes trying to self-medicate to reduce their TBI-induced chronic pain or mental health conditions, like escaping from the reality of their diagnosis, especially if the injury happened in a traumatic situation such as a car accident or military service. Using drugs and alcohol may result in the body developing a tolerance for these substances, and withdrawal is complicated because TBI symptoms are exasperated.

Lastly, homelessness is another comorbid condition. More than half of the homeless people or people living in precarious housing situations have had TBI at one point in their life, and this rate exceeds the general population. According to a meta-analysis conducted in Canada and the US, TBI and depression can cause neurological and psychiatric conditions, resulting in homelessness. At the same time, living on the streets can subject an individual to an unsafe environment where assault and aggression are more likely, resulting in a risk for further injuries.

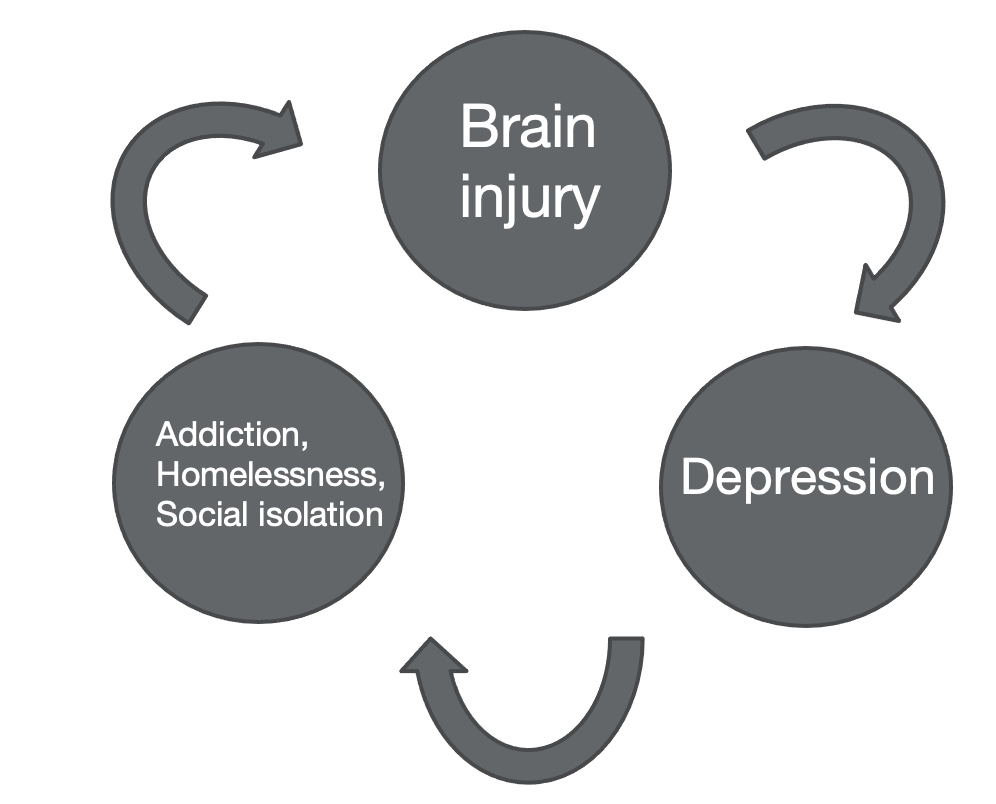

Vicious Cycle

There is a vicious cycle between burn injury, depression, addiction, homelessness, and social isolation, as seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The vicious cycle between TBI, depression, and addiction.

TBI can cause depression leading to addiction, with individuals trying to self-medicate, and depression can also cause homelessness because individuals are less motivated to participate in their productive occupations. They may have less income and can lose their housing. Depression can also cause social isolation because their personality and social connections may change after TBI. In turn, addiction can cause brain injury because if an individual misuses substances such as opioids, this can result in hypoxia and anoxia in the brain. There needs to be a partnership between healthcare professionals, friends, families, and community organizations to work with the individuals to help them regain access to the life they once had.

Role of Occupational Therapy With TBI and Depression

- Critical role in rehabilitating individuals with concurrent TBI and depression34

Occupational therapists play a crucial role in TBI and depression. Throughout the continuum of recovery, occupational practitioners assess and treat psychological, physical, and cognitive impairments to improve performance in occupations, making their role in TBI rehabilitation vital. Using a model like the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework for interventions is essential.

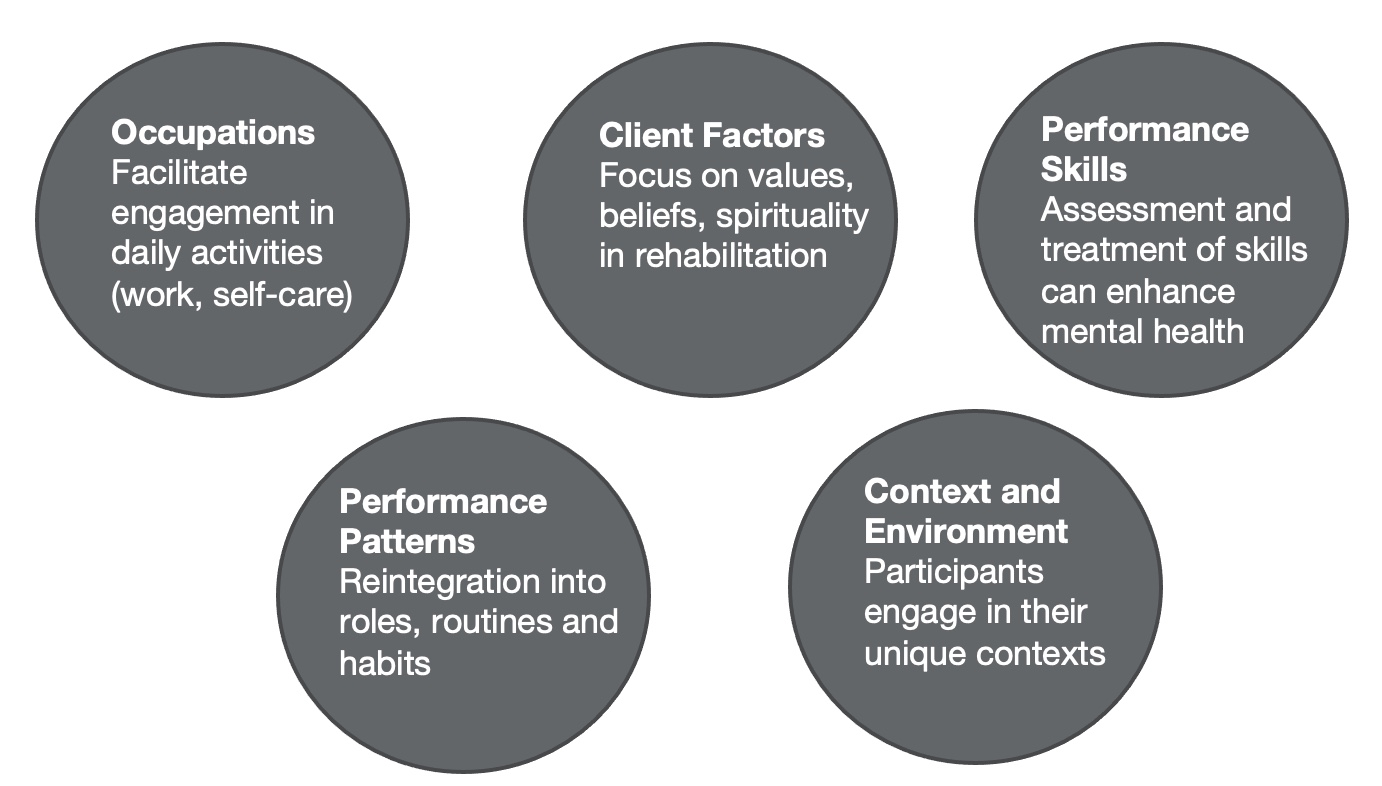

Occupational Therapy Practice Framework

- Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process – Fourth Edition (OTPF-4)35

The Occupational Therapy Practice Framework (OTPF) is divided into five subcategories, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Five subcategories of the OTPF.

Occupational therapists can facilitate engagement in occupation, specifically daily activities. They also focus on client factors like values, beliefs, and spirituality to enable occupational performance, especially in this population with a complex diagnosis of brain injury and mental health concerns. We can also assess and treat mental health and performance skills such as cognition and physical function to enhance mental health and performance in daily activities. This may include routines, role re-engagement, and what they did before the injury. By improving performance patterns, occupational therapists bring a unique perspective to practice areas like hospitals, outpatient settings, and the community. Context is vital. In this population, we want to meet the individual where they are to be more effective. You want to remove all barriers to accessing therapy. For the process part of the model, occupational therapists can work with clients in a client-centered manner to facilitate engagement and occupations. We can holistically evaluate and treat individuals.

Physical Function

- Upper limb exercise using functional activities

- Results in improvements in self-esteem and overall well-being

Occupational therapists can work with individuals to improve their physical function, mainly upper limb function, overall mobility, and transfers. Occupational therapists bring a unique perspective to rehabilitating physical function because they do so by using functional activities. An individual's performance in functional activities, such as grocery shopping and cooking, enhances their upper limb function, mobility, and transfers. Studies have shown that when occupational therapists integrate aerobic and aquatic exercise into their rehabilitation of individuals with TBIs and depression, this improves overall well-being, depressive symptoms, self-esteem, and overall quality of life. These results are sustained even after discharge.

Cognition

- Cognitive remediation

- Attention

- Attention Process Training

- Memory

- Executive function

- Use of virtual reality

- Attention

Occupational therapists can also help remediate cognitive skills in individuals with brain injury and depression. Attention is one of those skills that is needed to complete daily activities. The Attention Process Training Model is specifically developed for individuals with a brain injury and is based on five principles. I will briefly go over the principles. Principle one uses a theoretical model to base the rehabilitation resulting in a systematic delivery of rehabilitation. For example, this model divides attention into sustained attention, working memory, and alternating attention. So occupational therapists can divide their specific attention tasks into these categories and deliver therapy this way. Principle two is providing sufficient repetitions or practice makes perfect. If this is not possible in a clinical setting, provide a home program so the individual can practice the skills at home. Principle three uses patient performance data to direct therapy by assessing how the client is doing in the program and grading it accordingly. This information is essential for the therapist and the client to know. If they are doing great, this can motivate them to continue doing what is making them do so well during therapy. And if they are not doing so great, the occupational therapist and clients can come together and think of ways to improve engagement and performance in these attention skills. Principle four is using metacognitive strategy training. Many in this population lack insight into their deficits. Educating individuals about their weaknesses and strengths enables them to use their cognitive resources to support their weaker abilities. Occupational therapists can facilitate self-management and self-regulation skill development and get feedback from the client to motivate them to engage in the program. Lastly, principle five uses functional activities to improve attention rather than paper-pencil tasks. For example, an individual who wants to strengthen attention in a grocery store can scan through store flyers versus working on a focused attention task.

For memory, the occupational therapist should space out the information they are presenting to the individual, so the person can digest it better and remember it. It is crucial to enable individuals to self-generate what they want to remember. If they can relate it to themselves, they are more likely to remember the content. For example, paraphrasing or self-imagining can be used. Have them imagine themselves in the situation, making them more likely to remember a specific scenario.

The Cognitive Orientation to Daily Occupational Performance model (CO-OP ApproachTM) can be used to improve executive function. This is also based on metacognition and allows individuals to recognize their strengths and weaknesses. They use this information to develop goals with the OT and work on a treatment plan.

Other cognitive remediation strategies include the use of virtual reality. Virtual reality is shown to be effective in this population. Individuals with a TBI were taught how to use an ATM in a virtual setting. This practice improved their ability to use an ATM in real life.

In summary, when cognition is remediated, this results in more independence in occupations. Individuals can take part in occupations that they once found meaningful, and it results in an improvement in mental health concerns and an overall improvement in quality of life.

- Compensatory strategies

- Assistive technology

- Visual reminders

Compensatory strategies can be used when cognition cannot be remediated. One compensatory strategy is using assistive technology. A therapist should implement assistive technology, and support should be given throughout the whole process of the client learning how to use it and any help they need after learning how to use it. An example would be using a personal digital assistant device, which can provide reminders to do certain daily activities. A con of assistive technology is that it is expensive.

Another compensatory strategy is having visual reminders of what the individual needs to accomplish, which can be good for memory. If an individual forgets their doctor's phone number, you can help them paste that phone number near the telephone they use.

Mental Health

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)

- Peer mentoring

OTs can administer some of the principles of cognitive behavioral therapy to improve mental health in a group-based setting. A group setting can allow individuals to relate to one another, share their struggles, and feel less alone. They can learn to break unhealthy thinking patterns.

Individual cognitive behavioral therapy is also shown to be effective with this population, especially when OTs implement principles of motivational interviewing, where the individuals come up with the goals themselves. Virtual cognitive behavioral therapy is another avenue that OTs can provide. This prevents all barriers to accessing therapy as often this population is not motivated to come into a clinic or a hospital setting. You can give virtual cognitive behavioral therapy through the phone or video calling, as both are effective ways to improve overall mental health. CBT also results in more adaptive coping. Developing coping strategies can improve mental health and deal with the everyday stressors of life.

Another way to improve mental health is peer mentoring. Occupational therapists can facilitate peer mentoring by connecting the client to a mentor or community organizations with a peer mentoring program. Peer mentoring is significant because it allows individuals to feel more socially connected than they were previously. And interestingly, peer mentoring can also improve the self-awareness of their deficits because they see other individuals with similar deficits. Peer mentoring improves social integration, reduces loneliness, and improves overall mental health.

- Behavioral skills training

- Social skills training

Another way to improve mental health would be for occupational therapists to implement the principles of behavioral skills training during rehabilitation. Behavioral skills training can target unhealthy behaviors such as substance use or an angry reaction to an inappropriate situation. Some principles of behavioral skills training include providing clear and concise instructions for the goal behavior, modeling the behavior for the client to see you perform it, or seeing a video in which individuals are modeling the behavior. Rehearsing provides clients with a safe space to practice the behavior they are trying to work on and provides specific feedback for improvement.

Social skills training is another way to improve overall mental health in individuals with psychosocial, behavioral, and emotional impairments. During social skills training, occupational therapists can facilitate a person to have access to group therapy to meet new people. They are learning social skills in a natural setting or connecting them to community organizations with a social skills training program. Social skills training improves overall mental health but does not improve the person's likelihood of seeking a social situation. They may still not be likely to attend a social event even if they have the social skills training.

Functional Outcomes

- ADL rehabilitation

- Functional skills training

- Community reintegration programs

- Case management services

ADL rehabilitation can be used to improve functional outcomes. ADL rehabilitation is important because it allows clients to learn the basic skills they need to live independently at home, like bathing and dressing.

Functional skills training targets more IADLs, like returning to previous employment. Functional skills training is vital because it results in the long-term benefits of independence and employability.

Community reintegration programs or community rehabilitation is when the occupational therapist meets the client in the community and works on the client's goals. This extends beyond ADLs and IADLs. Community reintegration programs include home-based treatments like accessibility. Even phone calls to other healthcare professionals can be a goal of community rehabilitation. Community rehabilitation improves a client's quality of life, emotional well-being, independent living, and social participation. These effects remain stable after one and three-year follow-ups, and there is a definite benefit to meeting the client in the community versus in a hospital or outpatient setting. Case management services are also related to that.

Occupational therapists can be case managers and work with individuals one-on-one to identify goals they want to work on and act as a liaison within their healthcare team. Occupational therapists can facilitate appointments with a doctor, PT, or whoever is involved in their care. The occupational therapist manages the individual's healthcare team and works with individuals on specific goals. The goals could be to enhance independent living, and case management has also been shown to improve emotional well-being and independent living after TBI.

Occupational Adaptation

- Change of occupational identity after TBI

- Construction of positive occupational identity

- Occupational competence

Research has shown that there is a negative shift in occupational identity after TBI and also depression because individuals are not engaging in the occupations that they once found meaningful. They are not engaging in these occupations because their performance skills, like their cognition, physical, and functional abilities, have changed. To complicate this, having depression can result in decreased aspirations and goal-directed behavior. Therefore, with less goal-directed behavior, an individual may not be motivated to do the occupations they were once doing or find a way to solve problems and participate in them, resulting in a negative effect on occupational identity.

Occupational adaptation is constructing a positive occupational identity and achieving occupational competence within one's physical and social environment. Achieving occupational adaptation means that the individual can respond to internal and external pressure to maintain participation in their occupations. It allows the individuals to adapt to significant life events such as depression or having TBI. This process is taking this life event and having the resources to build their occupational identity. To allow an individual to develop occupational adaptation, an occupational therapist needs to take a holistic approach because every TBI is different.

Holistic Approach

- Identify core meaningful occupations

- Identify performance in these occupations

- Identify factors needed to perform occupations

Traditionally, occupational therapists focus on ADLs and IADLs, but a more holistic approach is warranted. Knowing the core meaningful occupations is very important to allow for occupational adaptation to be achieved. The core meaningful occupations can go beyond ADLs and IADLs. They can include the person wanting to participate in art or improve parenting. Practitioners need to know the core meaningful occupations, why they are meaningful for the individual, their performance in these occupations, and if they are currently satisfied with their performance. Occupational therapists also need to identify which performance skills are impacting the core occupations, whether cognitive, physical, perceptual, sensory, et cetera.

- Assess past and present life narrative to develop a "new narrative"

- Develop goals designed to support participation in meaningful occupations

- Occupational Performance History Interview

- COPM

While doing this, assessing the past narrative and developing a new one is vital. To do so, occupational therapists must give clients a safe space to talk about what they once found meaningful. This can be done by administrating semi-structured interviews, such as an Occupational Performance History Interview, based on the Model of Human Occupation. The Occupational Performance History Interview assesses the client's life history narrative, occupational identity, and occupational incompetence. It is a valid measure for occupational adaptation. Administrating this assessment can allow the therapist to learn more about the previous life and use this information to help the client create a new narrative.

It is also important to identify goals. Goals can be set using the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM), which can identify the client's challenges in performing specific occupations. The client works with the occupational therapist to identify problem areas, evaluate their performance in these occupations, and assess their satisfaction with these performances. The interview and the goal-setting assessment can allow the therapist to gain more information about the client and the client to become more self-aware about their problem areas and how to develop a new narrative.

"Loss of Self" and Grief

- Acknowledge "loss of self"

- Signs of grief

While doing this, the occupational therapist must provide a safe space so the client can acknowledge their grief about the loss of who they were. TBI impacts clients in all aspects; they may feel angry or feel this is unfair. Providing them with a safe space to talk about how they feel can provide vital information to the occupational therapist on how to help the development of the new narrative and talk about their feelings.

Reframing and Rebuilding Identity

- "Future self"

- Reframing of occupational competence to express their identity

- Compensatory strategies

- Alternate modes of participation

To reframe or rebuild identity, the occupational therapist must always support the client. The occupational therapist can think of creative ways so the client can participate in the occupations they once found meaningful. As mentioned earlier, this may include providing them with compensatory strategies, like personal digital assistant devices, visual reminders, or other alternate participation modes. For example, if an individual values playing basketball but cannot do so, we may provide them with an alternate way to play. Suppose compensatory and alternate modes of participation are not impossible, then helping the client develop new occupations that they may find meaningful may be a solution. We want to ensure they have a positive occupational identity even after discharge.

Self-management

- Problem-solving, decision-making, resource utilization

- Allows occupational competence after discharge from inpatient or outpatient supports

Occupational therapists and clients can work on self-management skills, like problem-solving, decision-making, and resource utilization, to ensure that they are prepped with all the skills needed after discharge. Self-management skills can ensure positive mental health, quality of life, and occupational competence for a prolonged period, not just in rehabilitation.

Social Interaction

- Integrate socialization in therapy

- Positive external validation

- Peer sessions, group therapy

OT should provide socialization in therapy. Occupational therapists need to look for opportunities to facilitate client interaction. An example would be encouraging clients to participate in group activities versus doing rehabilitation alone. When clients are rebuilding their new identity, they often seek external validation, and the OT and other healthcare professionals can provide it. However, it is more effective when it comes from peers, friends, and families. If the client is okay with it, you can integrate peers, friends, and families into rehabilitation so that the validation comes from an external source versus the healthcare professionals.

Again, socialization is essential during therapy because it allows the person to be more self-aware of what is happening to them and acceptance of their deficits. Awareness and acceptance are needed to improve occupational identity and move towards positive occupational identity development.

Summary

- Rehabilitate physical and cognitive abilities

- ADL rehabilitation

- Community rehabilitation & case management

- "old self" vs. "new self."

In summary, it is essential to rehabilitate physical and cognitive abilities because these are vital skills needed to complete daily activities. ADL rehabilitation is necessary because these are basic skills that an individual needs to stay safe at home and to be discharged to their home.

Community rehabilitation and case management are essential because they allow a therapist to meet the client in a familiar context. Providing therapy in the person's home or the community can reduce barriers to accessing treatment because, often, individuals are not motivated to attend therapy. The case management role can allow the therapists to work on any goals that the client wants to work on, including liaising with other healthcare professionals in their healthcare team or working on skills such as accessing the transit system.

It is essential to acknowledge the old self and provide a safe space for individuals to grieve over the loss of their old self and use this information to develop and new narrative and identify meaningful core occupations. This should always be done in partnership with the client, and the client should be facilitating their rehabilitation. They need to develop their goals and what they want from rehabilitation.

- Client-centered approach

- "It's far more important to know what person the disease has than what disease the person has." -Hippocrates

- Holistic approach

A client-centered approach is warranted because many factors determine the individual's occupational engagement and mental health. We must consider these factors when rehabilitating individuals with TBI and comorbid conditions such as depression. I like this quote, "It's far more important to know what person the disease has than what disease the person has." A person should always be looked at first before diagnosing TBI and depression.

A holistic approach to treatment can identify clients' goals, needs, and wants and improve their occupational adaptations and identities.

Next Steps

- Future research

- Interview persons with lived experience to determine priorities for occupational therapy

- Training during education to enhance rehabilitation of individuals with comorbid conditions

Integrating individuals who have lived experience in the research process is important. We need to ask those with TBI and depression what they want to see from occupational therapy. A lot of research does not integrate individuals with lived experience, so we must hear from the clients themselves on what they want to see from us. It would also be helpful if occupational therapy students were trained to assess and treat individuals with comorbid conditions such as TBI and mental health because mental health concerns like depression are widespread. A person with brain injury probably has either diagnosed or undiagnosed mental health concerns. If the training is started earlier, this can result in more effective rehabilitation for these individuals.

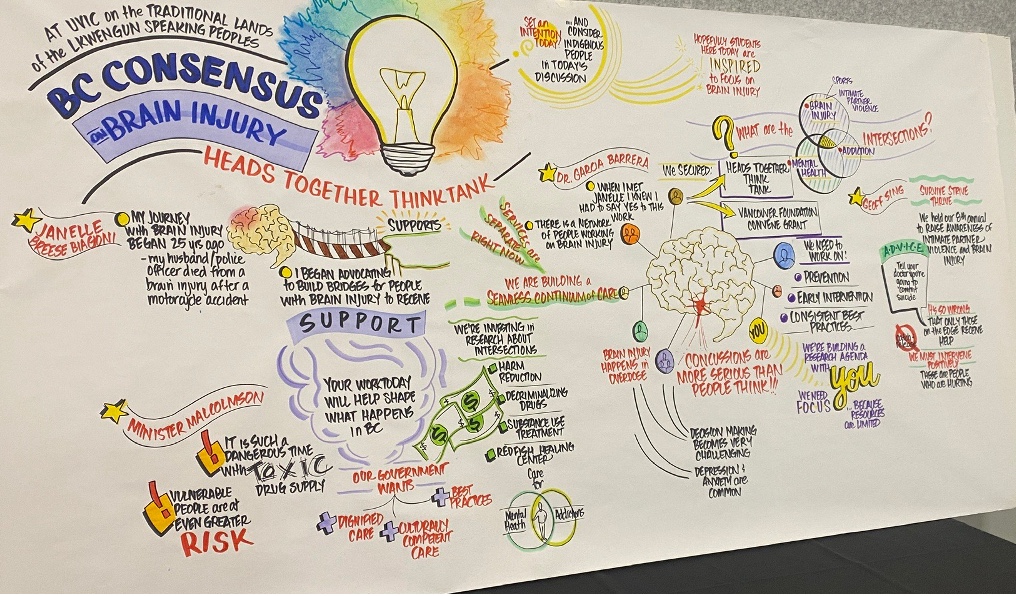

- Our next steps

- Consensus building day in British Columbia, Canada

Regarding our next steps, Dr. Julius Schmidt and I are part of the British Columbia Consensus Building Initiative. This three-year project focused on identifying the priorities for research and clinical care in areas such as brain injury and its connection to mental health, substance use, homelessness, and intimate partner violence. This research is conducted with individuals who have lived experience. We first met a couple of weeks ago in Victoria, British Columbia. Figure 3 shows a nice picture of a few topics we spoke about, such as support, support from the government, and the risk of substance use after brain injury.

Figure 3. BC consensus on brain injury.

Our lab also has projects focusing on self-identity and social participation after traumatic brain injury.

Video: Living in a Reshaped Reality: Exploring Social Participation and Self-identity After TBI

Here is a video of Julia and my colleague, Rinni, a fellow PhD student. They will explain what we have found recently.

Julia: I lead the Cedar Brain Injury Lab. Our lab is based at GF Strong Rehabilitation Center and affiliated with the University of Bridge Columbia in Vancouver. Our lab collaborates with people with brain injuries, community associations, healthcare providers, and policymakers. And we want to understand the experience of brain injury and develop programs to support quality of life and personally meaningful goals after brain injury. In this study, we partnered with people with brain injury and the BC Brain Injury Association. Our overall goal for this study is to understand social participation and self-identity after brain injury.

When people think about life after brain injury, many people focus on the physical and cognitive issues that can occur. Indeed, this is much of the focus of rehabilitation and healthcare. However, after brain injury, people can also experience changes in their participation in social roles and their sense of self. And so in our study, we wanted to explore the impact of these changes on individuals with TBI. We used a qualitative methodology that uses words and stories as data. We obtained this data by talking to 16 people from moderate to severe TBI.

The people in our study expressed how nothing's the same after their injury. They described the daily challenges they faced when they tried to get back to their social lives and reconnect with activities that they used to do, like work or their hobbies. Another challenge with the comparisons that an individual with TBI made about themselves when comparing who they used to be before their injury to who they are now. For example, one participant said, "It's mainly because when you're independent and energetic and then after I suffered really, really, really bad." Finally, the third challenge participants talked about were the experiences of living with an invisible injury. Other people would minimize their TBI due to the invisible nature of it. One participant said, "Trying to explain to people sometimes was really hard for me. They said, 'You look fine now, what's wrong with you?' "

Participants also expressed a process of rebuilding and restarting, where they talked about how they navigated true and unfamiliar life post-injury. They described how the support from their family and friends, healthcare professionals, and the wider community helped them restart their life after brain injury. Participants reflected on how they experienced a turning point, having that "aha" moment where they found a purpose, which led them to change their perspective about their life with injury. For example, one participant said, "I'm like, what am I worth? What am I here for on this planet? What do I do? And that's when I realized that I have to find this."

Participants in our study describe self-acceptance with their new reality of living with a TBI. They talked about the determination and resilience they developed to overcome the problems that happened after their injury. Participants also talked about being able to empathize with other individuals with a disability. For example, one participant noted, "I feel like I can relate to people who've gone through stuff because I know what I've been through." Overall, our study describes the experiences of living with a TBI, illustrating the new reality of life after TBI.

We hope our study can lead to more research and clinical practice changes, which will explore how individuals can develop and strengthen their responses to the adverse encounters after sustaining a TBI.

Thanks for your interest. For more information or updates on our lab, find us online or on Twitter at CEDAR_BrainInjury.

Questions and Answers

You brought up the hidden aspect of brain injury. Do clients talk about that? Additionally, do those with brain injury grieve their prior self?

We had a meeting about two weeks ago for the BC Brain Injury Consensus Building Initiative that I discussed. A participant had a brain injury in her teens. She spoke about how she was not diagnosed until many years later, but she was still grieving the loss of that time between having the brain injury and then being diagnosed. That time was difficult for her; she lost all her occupations and identity. She also stated that her brain injury was invisible to the outside world.

I think occupational therapists bring a unique perspective to this population as we typically treat them for longer and can hear their stories. Unfortunately, individuals in other healthcare or hospital settings may not be heard similarly. They may be rehabilitated with a focus on cognition and physical function instead of how the brain injury has impacted their mental health and overall meaning of life.

References

Available as a separate handout.

Citation

Grewal, J., & Schmidt, J. (2022). Depression after brain injury. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5559. Available at www.occupationaltherapy.com