Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Optimizing Mobility And Community Engagement For Older Clients, presented by Wendy Stav, PhD, OTR/L, FAOTA.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to describe the contribution of driving and community mobility to the health and quality of life for their aging clients.

- After this course, participants will be able to distinguish the role of the generalist occupational therapy practitioner from the specialist in driving and community mobility to enhance collaboration and address client needs throughout the continuum of care.

- After this course, participants will be able to identify clinical assessment tools predictive of determining fitness to drive or use transit and intervention approaches to optimize performance.

Introduction

Today, we will look at optimizing mobility and community engagement for older clients since folks need to get out and about in the community. We cannot start this conversation without jumping into some of the definitions.

Driving and Community Mobility

- Classified as an IADL

- Driving and Community Mobility

- "Planning and moving around in the community using public or private transportation, such as driving, walking, bicycling, or accessing and riding in buses, taxi cabs, ride shares, or other transportation systems" (AOTA, 2020, p. 31)

- Occupation Enabler

- Facilitates participation in other occupations (AOTA, 2016; Stav & Lieberman, 2008)

According to the OT practice framework, driving and community mobility are classified as IADLs, instrumental activities of daily living. It is defined as planning and moving around in the community using public or private transportation, such as driving, walking, bicycling, or accessing and riding in buses, taxi cabs, ride shares, or other transportation systems.

Community mobility gets us from point A to point B, as defined in the IADL definition in the framework, but it also serves as an occupation enabler. We started writing about this around 2008 when we recognized that getting out and about in the community was not only about getting you from point A to point B but also allowing people to engage in many occupations throughout the community. Driving and community mobility facilitated participation in a whole host of other occupations, like shopping, accessing healthcare, social participation, work, and volunteering. These activities require us to get to someplace first.

- Greater than 77% of older adults rated driving as "completely important" in urban, suburban, and rural areas (Strogatz et al., 2020)

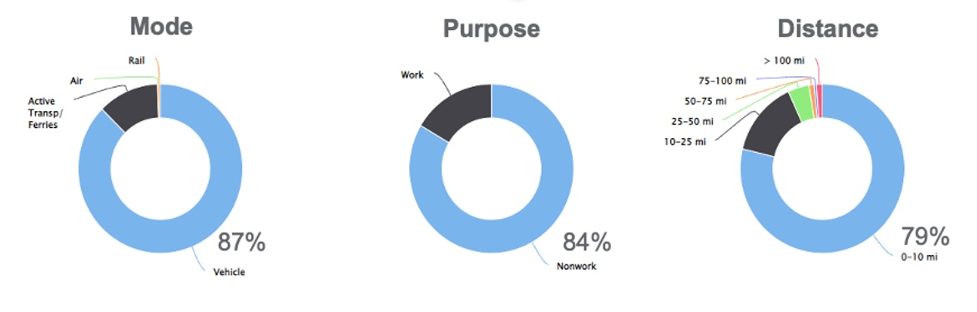

Greater than 77% of older adults rated driving as completely important. It did not matter if the people answering that question were in urban, suburban, or rural areas. They all said driving was essential. These graphs in Figure 1 break down how people are getting around.

Figure 1. Chart of how people get around (FHWA, 2022). (Click here to enlarge this image).

Looking at this first graphic, 87% of people travel by vehicle. It would not be enough to say, "Let's give everybody buses," because 87% are using cars. In 84% of the cases, they are not traveling for work. This is not surprising, as most of these folks are retired. Regarding distance, 79% only travel zero to 10 miles from their house for most of their trips. Again, not surprising because they often go to the grocery stores, friends' houses, and churches that are in relative proximity. Driving is extremely prominent in their daily lives, allowing them to engage in various community occupations.

Implications of Driving Cessation

- Declines in:

- General health

- Physical health

- Social health

- Cognition

- Increases in:

- Entry into long-term care

- Risk of mortality

- Depressive symptoms

(Chihuri et al., 2016)

It can be quite devastating when someone cannot drive anymore. There can be declines in physical, social, and cognitive health. We know that when people stop driving, there can be an increase in admissions to long-term care. There is also an increased risk of mortality and depressive symptoms.

I want to address this depressive symptoms piece for a minute. Since the mid-nineties, research has shown that when older adults stop driving, they have an increase in depressive symptoms, like it was a direct causation.

When I put on my occupational therapy hat, I think, of course, it is a bummer when you lose the ability to drive. Still, as an OT and my strong belief system in the connection between health and occupational engagement, I realize that driving cessation means that people experience tremendous occupational loss. They cannot see friends, volunteer, go to the doctor's office, go grocery shopping, go to their bowling league, or what have you. It is occupational loss that causes health decline, specifically depressive symptoms.

The big difference between how an OT versus others look at older driver issues is that we recognize a very strong link to occupational engagement.

Occupational Implications Driving Cessation

- Interruption in meaningful occupational engagement:

- Leisure

- Social participation

- Employment

- Volunteering

- Shopping

- Negative effects to health and quality of life:

- Access to medical care

- Grocery shopping

- Limitations in transportation alternatives:

- Destinations

- Schedules

- Municipal lines

When people stop driving, they lose their meaningful occupational engagement. It is harder to access their leisure and social pursuits. Those still working have difficulty getting to and home from work, volunteering, or shopping.

We are an automobile-dependent society, particularly in the United States, and we do not have a big transit infrastructure. When we stop driving, we lose meaningful occupational engagement. There is a big trickle-down in terms of the negative effects on our health and our quality of life, specifically in accessing medical care and even grocery shopping. For example, if I now have to take a bus, I do not have a trunk to store groceries. It makes grocery shopping more difficult, leading to further health declines. I can only carry much on the bus, the transit, or in the community van. And if you think about the grocery store, the healthiest food is around the store's perimeter, and those are the things that need to be refrigerated. Additionally, produce, dairy, meats, and healthier foods weigh more. Folks start buying more prepared foods that are higher in sodium and fat, but they weigh a lot less. It is much easier to buy a couple of boxes of macaroni and cheese. We see a trickle-down with health declines as a result.

There are limitations with transportation alternatives because of how our infrastructure is built, or I should say is not built. It is harder to get to certain destinations. Schedules are limited, and it might be difficult to get somewhere early in the morning or later at night. We also may not be able to cross municipal lines. For example, if I live in one town, but the theater is in the next town, my town transit system will only take me to the town line.

Meaning Associated With Driving

- Independence

- Self-reliance

- Spontaneity

- Freedom

- Empowerment

- Escape

- Speed

Our worlds shrink considerably when we can no longer drive. this can be difficult. We associate the ability to drive with independence and self-reliance. When we drive, we can be spontaneous. If I decide to make chocolate chip cookies, I can go to the store to buy the ingredients. Driving is associated with freedom, empowerment, the ability to escape, and speed. If I limit or reduce all of that meaning associated with driving, that becomes a significant problem.

Reach of Meaning and Implications

- Older adults represent 16% of the US population totaling over 54 million [2019 data] (NHTSA, 2021)

- 20% of all licensed drivers

- 7,214 traffic fatalities

- 286,000 traffic injuries

- 1,290 pedestrian fatalities

- 171 pedal cyclist fatalities

- Approximately 49 million people had a disability in 2020 (US Census, 2022)

- Clients with neurological, orthopedic, and metabolic conditions may all experience issues

When we consider the reach of these implications, we are talking about a large portion of the US, or 16% of the population. The latest data from 2019 reports that 54 million older adults represent 20% of all licensed drivers in the country. The data goes back two years in terms of when it is published.

Regarding traffic safety data, this same population of drivers represents 7,200 traffic fatalities, 286,000 traffic injuries, almost 1,300 pedestrian fatalities, and 171 bicycle fatalities.

According to the 2022 US Census, 49 million people had a disability in 2000. This is a huge number of people with some combination of neurological, orthopedic, and metabolic conditions who may be experiencing some difficulties with driving and community mobility.

Occupational Therapy Role in Addressing Driving and Community Mobility

- Determine medical fitness to drive or use transit

- Provide intervention when appropriate

- Refer to a specialist when needs are outside one's scope

- Report to authorities as legally allowable

- Support community mobility for continued engagement in the community

This brings us to our role and what can we do as occupational therapists to address driving and community mobility with this population. We have the capacity to determine medical fitness to drive or use transit. As OTs, we can determine who can and cannot drive. We can provide interventions when appropriate to help people transition back to driving, maintain driving, or find some other way to get out and about in the community.

We can also refer people out. When there is a problem that we cannot resolve or are not trained to address, we need to be able to refer those folks out to specialists. We should be reporting to authorities as legally allowable. The rules are different in every state for medical reporting, and we will talk about that a bit later.

We should also support community mobility for continued engagement in the community. For some people, driving is the best answer, and we can get them back to that safely. For other folks, that might not be the case, and we need to look at other modes of mobility or bring services in. There is quite a range of what we can and should do as OTs.

Role of the Generalist Vs. Specialist

Next, we are going to talk about the distinction between the generalist and the specialist. We, as OTs, should be addressing driving and community mobility, whether we specialize in this area of practice or are your average Jane OT working at a rehab hospital.

- All therapists should address driving issues

- At a different point in the continuum of care

- With a different depth of focus

- Important to know what the other is doing

- Avoid repetition of assessments

- Make appropriate referrals

All therapists should address driving issues, but the difference between a generalist and a specialist is that they do different things at different points in the continuum of care and with different depths of focus. In both roles, it is important to know what the other one is doing so that we are not repeating assessments, making appropriate referrals, and being as efficient and as informed as we can.

If you are a generalist, you want to explain to your clients why you are referring to a specialist. This is similar to how an internist tells you to go to a cardiologist to get a certain test. "Hey, I think you need a driving eval. I'm going to refer you to somebody. Here's what you will do when you go there." This is why it is important to distinguish the two roles.

Generalist

- Goal: Optimize occupational engagement

- Inquire about community mobility needs

- Assess performance skills related to driving

- Refer to other disciplines or specialists

- Recommend discontinued driving or alternative

- Responsibility to be aware of state regulations

- Provide skill-building services to lead to driving

- Focus on independence AND safety

As a generalist, our goal is to optimize occupational engagement. That is always our goal. We should inquire about people's community mobility needs and how much they need to get out and about. We assess their performance skills related to driving and refer them to other disciplines or specialists whenever the issue is outside our scope. We should recommend discontinuing driving or using an alternative if necessary. It is important to be realistic with people.

There is also a responsibility to be aware of your state regulations.

We can provide some skill-building services for people who want to return to driving.

Lastly, we always focus on independence and safety. This is an interesting dichotomy we are not always used to addressing. We pay attention to safety with regard to impulsivity and falls, but in the world of driving, people want to protect people's independence. However, it is important to recognize driving safety as well.

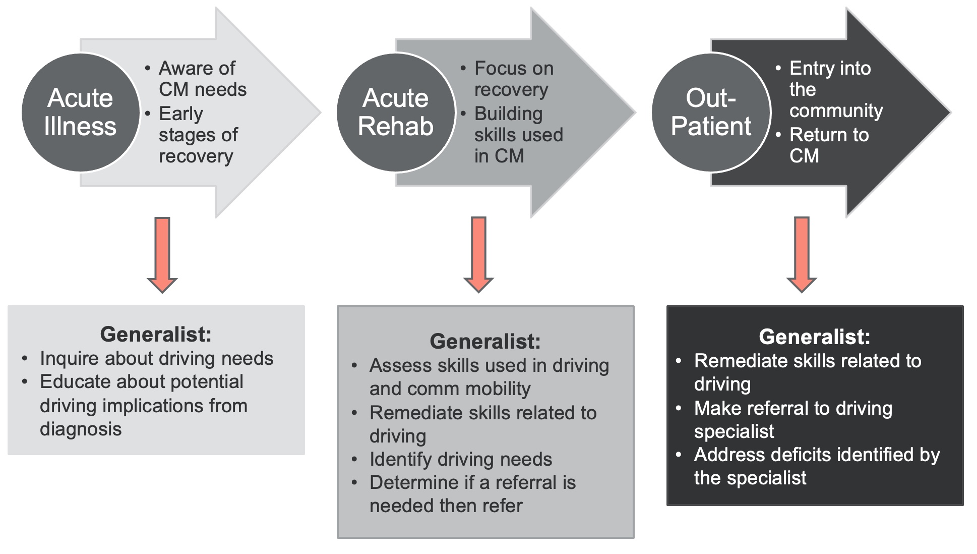

In traversing through the continuum of care, we will start with the generalist (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Continuum of care for the generalist.

When people are acute, we need to be aware of their community mobility needs and pay attention to the early stages of recovery. We should be inquiring, "What are your driving needs?" and "How much do you need to get out and about?" Be realistic in terms of educating people about the potential implications. If somebody has a dense stroke, for example, we want to be realistic and tell them, "It's not likely you'll be back in your car in two weeks." Instead, we should tell them, "Until it's been determined that you're safe, you will need not to drive when you first go home. You'll have to work your way back up to that."

In acute rehab, the clients focus on their recovery and building their skills. We should be assessing and remediating their skills used in driving and community mobility. We will talk about what those skills are in a bit. We should also determine if a referral is necessary. Remember, when they are recovered enough to be discharged from acute rehab, they are probably not at peak performance yet to start driving. They may not even be ready when discharged from outpatient. There is a big difference between "I can meet my goals and be safe 80% of the time" and "I can operate a 2,000-pound vehicle." You must look critically at somebody's readiness.

From an outpatient perspective, clients are getting ready to return to the community and community mobility. Again, the generalist is remediating those needed skills, whether strength, balance, coordination, or cognition, to get back to driving. They should refer to a driving specialist if the client is ready. Sometimes people will circle back around to get a driving eval, and it will be determined that such and such deficit still exists, and the person then gets referred back to outpatient to build those skills further.

Specialist

- Goal: Optimize performance and safety in driving and community mobility

- Advanced training, not entry-level practice

- Evaluation of driving, including in-vivo assessment

- Determination of medical fitness to drive

- Provision of vehicle-based interventions

- Training in the use of adaptive driving equipment

- Advocacy for system modifications

- Can be certified as CDRS or SCDCM

The specialist is somebody with a focused scope of practice. Their goal is to optimize performance and safety in driving and community mobility. These folks have advanced training, and it is not considered entry-level practice. They will evaluate the whole scope of driving, not only the skills used in driving but also an in-vivo assessment in the car. At the end of this, they will be able to determine medical fitness to drive and provide vehicle-based interventions.

The specialist also provides training in using adaptive-driving equipment, which we will talk about toward the end.

They also do advocacy for system modifications. If the medical reporting laws in your state are not ideal, or there are some loopholes or clarification needed, a specialist might advocate for change. You do not need to be specialty certified, but there are specialty certifications that one can get.

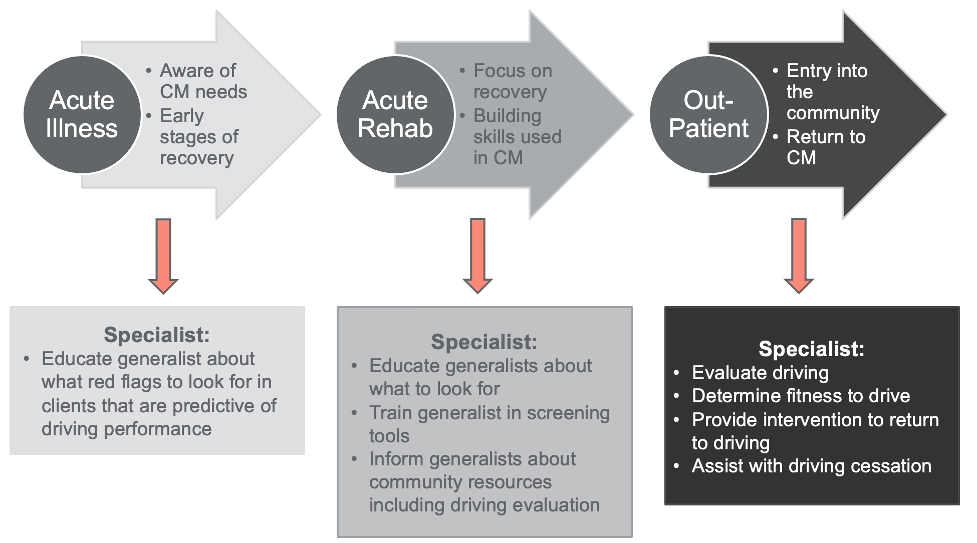

Let's travel through the continuum of care for a specialist, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Continuum of care for the specialist.

When a person has an acute illness, they should be aware of their community mobility needs. At this point, the specialist is not working directly with the client. Still, they could educate the generalist, saying, "Here are the red flags or things that might be predictive of their ability to drive."

Assessment of Driving & Community Mobility

- Generalist

- Interpretation of assessments and observation from a course of rehab services

- Administration of screens – interpret with caution

- Similar clinical reasoning used when considering safety to cook or bathe

- Be aware of tools specialist is using to reduce possibility of learning the test

- Result: Decision of fitness to drive/ use transit or referral to specialist

- Specialist

- Administration of assessment tools proven to be predictive of crashes or driving performance/use of transit

- Administration of an in-vivo road/transit test to measure performance in the naturalist context

- Result: Decision of fitness to drive/use transit

The generalist can interpret assessments and observations from the services they are already providing. Many facilities offer a pre-driving screen or assessment and charge more for that. I question the ethics of that. If the generalist has been treating somebody for two weeks already, they should know their balance, strength, coordination, cognition, and sensation. They do not need to do additional testing specific to driving. We should be interpreting all the information we already have. We might administer some screens specific to driving, but I would encourage you to interpret those with caution because nothing is definitive. You will use the same clinical reasoning when determining if somebody can go home and cook or shower themselves, except the stakes are even higher. You want to always be aware as a generalist of the tools that the specialist is using because we do not want people to start to learn the tests. At the end of the day, the result for the generalist is either a decision of fitness to drive for somebody at the end of that performance continuum or a referral to a specialist.

Regarding the specialist, the specialist will administer assessment tools that have proven to be predictive of crashes or driving performance. They will administer an in-vivo road test to determine medical fitness to drive.

Occupational Profile

- Who is the client?

- Why is the client seeking services?

- What occupations and activities are successful or causing problems?

- Driving/Community Mobility

- Secondary to driving

- What contexts support and inhibit driving/community mobility performance?

- What is the client's history related to driving/using transit?

- What are the client's priorities related to driving and community mobility?

We always want to start with an occupational profile to determine who the client is, why they are seeking services, what occupations and activities are successful, and which ones are causing problems. We may ask, "Can you drive and travel in the community? Or, "What occupations are now limited secondary to you being unable to drive?" We want to determine what contexts support or inhibit driving or community mobility performance. We want to know their history related to driving and using transit. You can also ask about their history related to crashes, but you do not always get an honest answer. Lastly, we what to know their priorities. Some clients, particularly women, tend to say they are done driving. "As long as I can get a ride, I'm done driving." Men are the opposite and want to continue driving.

Clinical Assessment

- Tests of client skills/deficits

- Conducted in the "clinic"

- Battery of assessment tools

- Choose tools based on

- Client-specific diagnosis and needs

- Evidence of value of tool

We should start with a clinical assessment with a battery of assessment tools. There are dozens of tools you can use, or the specialist may choose tools specific to the diagnosis and their needs. For example, if somebody is referred to me with dementia, my assessments will be heavier on the cognitive side. Still, if somebody is referred to me with a spinal cord injury, my assessments will be heavier on the motor and sensory side. The tools I compile will be different depending on the diagnosis, but there are some core tools that I always use. I also look at the evidence of the value of the tool.

What the Tools Measure

- What constructs are being measured

- Vision

- Cognition

- Motor performance

- What does the literature say about a relationship to driving/ community mobility?

- Predictability of crashes

- Indicative of driving performance

- Independent use of transit

The constructs we are measuring are vision, cognition, and motor performance.

You also want to look at what the literature says about driving. I always want to know how strong a tool is in building my case. Some of the evidence will be about the predictability of crashes, which means they administered some assessment tools and then waited two to five years and tracked who crashed and who did not crash. They then run a regression to see which tools predicted people crashing. This is a tricky study because you have to wait for people to crash, it takes time, and crashes are rare occurrences.

More of the evidence talks about being predictive or indicative of driving performance. They administer a bunch of tools and then put people on the road for a road test. The result is immediate or around 45 minutes later. You do the same analysis and see which assessment tools were predictive of somebody passing or failing that road test.

You also want to look at the evidence about the independent use of transit, although that research is almost nonexistent. It is a huge gap in our literature, and we have not done enough research on what predicts the use of transit, as everything has been focused on driving. This is not surprising because that is the primary mode of mobility in the United States.

Vision/Perception Assessments

- Vision is important to assess to ensure adherence with state guidelines

- Acuity most commonly has a state minimum

- Visual fields minimums are often identified

- Use traditional visual screens and refer to eye care specialists for concerns

The first area of assessment I always do is vision because I want to ensure that I adhere to the state guidelines. For example, they may say that the client has to have an acuity of 20/70 to drive. Some states also have minimum visual fields. If a person has a visual field loss from a neurological injury, they might not meet the minimum guidelines for vision.

I always like to do vision testing first for a couple of reasons. If a person does not meet the minimum standards for vision in the state, I will not waste their time continuing the test. I will send them to an eye care specialist, and then they can come back. The other thing is if they have impaired vision, it might influence their performance on the other tests, especially the cognitive assessment. Typically, vision is assessed via a chart on the wall, and there are a number of machines, like in the DMV, where vision can be checked.

- Visual acuity

- NOT linked to crashes

- Contrast sensitivity

- Linked to crashes

Some tools have been linked to crashes in the evidence and have not. Visual acuity is not linked to crashes, nor is it predictive. One can have 20/70 or 20/100 vision, and you can still see all the cars around you and the road.

Contrast sensitivity has been linked to crashes. Contrast sensitivity declines as we age because the cells do not slough off our eyes, and our lenses thicken and yellow. This natural aging process decreases our contrast sensitivity. A test for contrast sensitivity is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Contrast sensitivity test. Computer.club.ksauhs, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Think about being at an intersection on a gray, rainy day. If a grayish-silver car drives through that intersection, there is little contrast to distinguish the car from the road or the curb. Contrast sensitivity gets worse in all of us, starting at around age 50, and has been linked to crashes.

Cognitive Assessments

- Cognitive deficits often necessitate the need for driving cessation

- High-level cognitive skills are required for planning and navigation in community mobility

- Many publicly available screenings measure cognition

- Predictability of driving is an important consideration

We do pay a lot of attention to cognitive assessments as it is often what necessitates the need to stop driving. When a person cannot move or see, it is fairly obvious. However, when a client has decreased cognition, or impaired insight is not great, they may not know to stop driving.

Driving requires a very high-level cognitive skill to plan and navigate an unpredictable environment. There are many publicly available screens by AAA and by AARP that include a cognitive component.

Predictability of Cognitive Assessments

- Predictive

- Trail Making B

- Useful Field of View

- Not Predictive

- Mini-Mental Status Exam

- Inconsistent

- Symbol Digit Modalities Test

- Clock Drawing Test

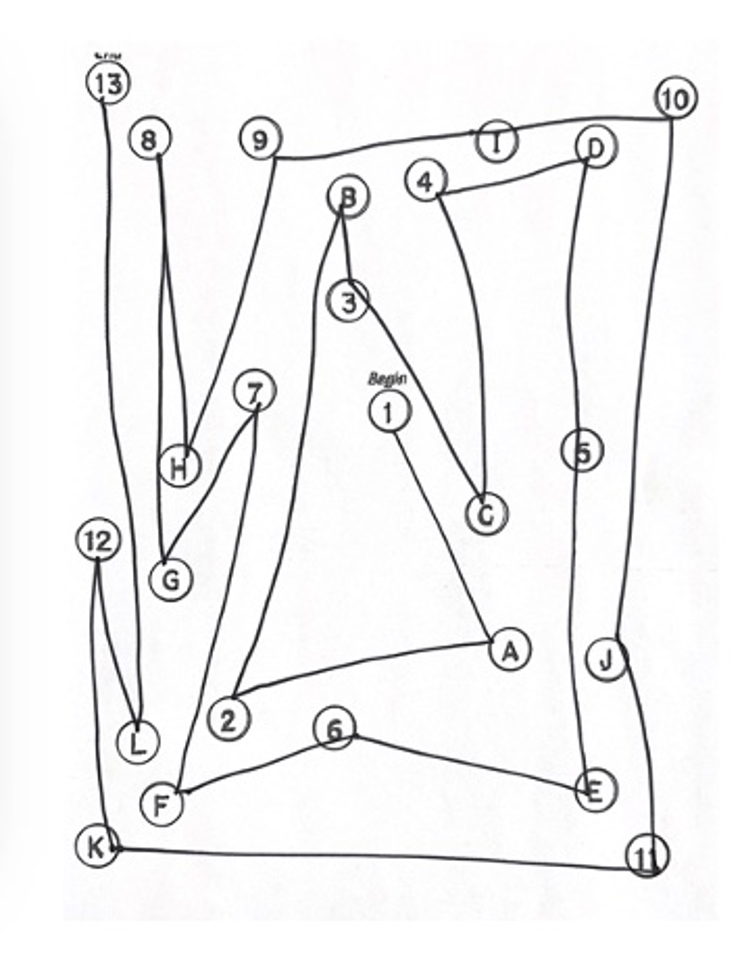

What you want to pay attention to is the predictability of driving. Most screens merely give a heads-up that someone should get checked rather than the capability to say whether the person can or cannot drive. I would say that of all the tools that have been studied in terms of predictability, cognition is the biggest area. Trail Making B, a paper-pencil test seen in Figure 5, is available online for free.

Figure 5. Trail Making B.

The person has to connect the letters and numbers in order, 1-A, 2-B, 3-C, 4-D, and so on, and it is timed. Different studies show time thresholds where if the person goes longer, they are more likely to crash. I put the test results in my report to the doctor and the DMV. "Mr. Smith completed Trails B in four minutes and 23 seconds with two errors, and the evidence shows that people taking longer than two minutes are more likely to crash."

Useful Field of View is an expensive computer-based test that looks at processing speed, divided attention, and selective attention. It has also been shown to be very predictive, but you must have a computer with the program.

The Mini-Mental Status Exam (MMSE) has not been shown to be predictive, and I recommend not using it.

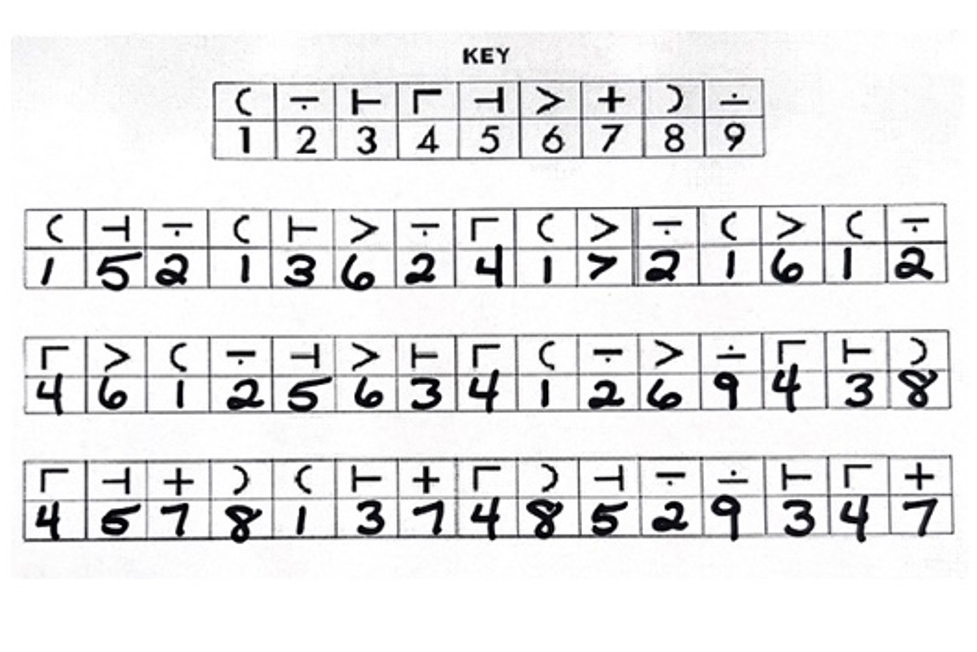

The Symbol Digit Modalities Test, shown in Figure 6, looks like decoding on the back of a cereal box.

Figure 6. Symbol Digit Modalities Test.

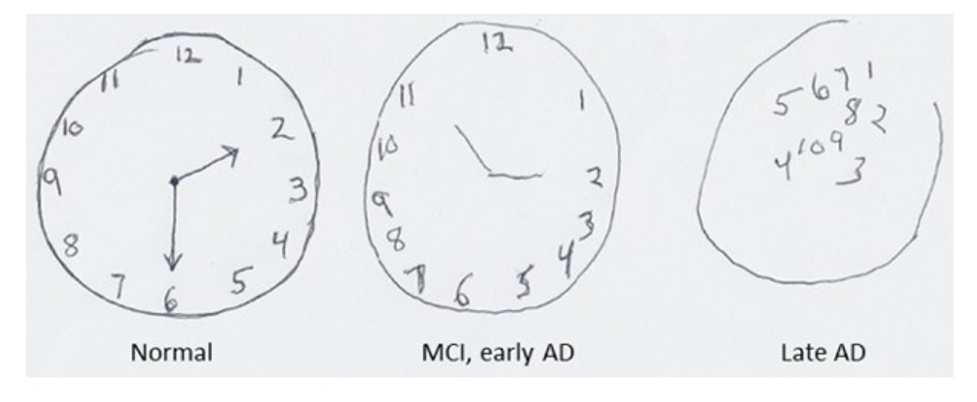

Some studies show it is predictive, and some studies do not. The Clock Drawing Test (Figure 7) also has inconsistent results.

Figure 7. Clock Drawing Test.

Interestingly, the Virginia State Police uses the Clock Drawing Test on the roadside and use a scoring system to determine if the person is safe to drive home.

Motor Performance Assessments

- Consider the ability to:

- Transfer in and out of the vehicle

- Operate vehicle controls

- Steering wheel

- Foot pedals

- Key in ignition

- Sustain movement or position

- Feel where limbs are in space

It is important to observe whether somebody can move in and out of the vehicle, operate the vehicle controls, and sustain their movement. Do they know where their limbs are in space? In older adults, we see a lot of pedal confusion. People think they are slamming their foot on the brake, but it is the gas instead.

We see a lot of people driving into storefronts, through toll booths, etc., because they're not quite sure where their foot is in space.

Motor Assessments

- Strength

- Range of Motion

- Proprioception

- Kinesthesia

- Transfers

- Rapid Pace Walk

For motor assessments, we look at people's strength, range of motion, proprioception and kinesthesia, transfers, and the Rapid Pace Walk. Rapid pace walk is a 10-foot length of tape on the floor. You have somebody walk from one end, turn around, and then come back, and you time it. If it takes longer than seven seconds, then that is predictive of not performing well when you are driving. With these different pieces, including the Occupational Profile, vision, cognition, and motor performance, I have to figure out what it all means.

What Does It All Mean?

- Performance on assessment tools paints a picture

- Outlines what you MIGHT see during the road/transit test

- Clinic-based tests do not definitively predict crashes or performance… yet

Clinic-based tests do not definitively tell me whether somebody can drive safely or not, but rather they show how I might expect a person to perform once we get out on the road. For example, if I noticed that on Trails B, a person had a hard time finding the letters and numbers on the left side of the page when we get out on the road, I am going to ask them to change lanes to the left. I may have them look for a parking space on the left or more left-hand turns. I start to fill in the pieces to paint a full picture.

There are still those who are hopeful that they are going to find the silver bullet which will be able to definitively determine whether somebody can drive safely or not. As an OT, I do not believe that this is possible. I think human performance is dynamic, and the context of driving is complex and unpredictable. There is no way a clinic-based assessment tool can tell us all the answers.

Road Test

- Assesses driving in a naturalistic environment

- Provides real-life perceptual challenges

- Sensory feedback while driving with consequences

- Progressively complex environments

- Real-life problem solving

- Critical in making clinical determinations about safety

- PREDICTIVE of driving performance

Once I have this sense of how they might perform, then I go into the in-vivo test or the road test to test somebody's abilities in a naturalistic environment. It gives real-life perceptual challenges like cars pulling out in front of them, honking horns, people negatively gesturing, slamming on the brakes, et cetera.

We go through progressively complex road environments with real-life problem-solving. This in-vivo test is more predictive of driving performance. Even still, there is nothing that is 100% predictive driving, as the environments are very unpredictable. Somebody could hold it together for the road test and, two weeks later, crash their car. In fact, there is no guarantee that one of us will not crash our car in the next two months. Hopefully not, but there is no definitive way to determine that. Just like there is no way for me to definitively say you will not fall in the tub. I can have a good guess whether you have the skills, equipment, and resources to be able to do it safely, but you never know.

Skills Assessed in a Road Test

- Vehicle Skills

- Transfer into vehicle

- Adjust seat

- Don seatbelt

- Adjust mirrors

- Put the key in the ignition

- Identify turn signals

- Locate wiper control

- Locate horn

- Driving Skills

- Use of vehicle controls

- Stopping

- Gap Acceptance / Following Distance

- Lane Keeping

- Turning (left and right)

- Lane changing

- Merging

- Speed control

During the road test, we measure people's vehicle skills. Can they transfer in and out, adjust the mirrors, turn the key in the ignition, and locate everything in the car?

Specific to driving, can they use the vehicle controls? Can they start and stop and follow at an appropriate distance? Can they stay in their lane or turn in both directions and change lanes? Can they maintain their speed control?

One of the biggest predictors or red flags I see with people with cognitive decline is that they will drive very slowly, like 15 miles an hour, on a 40-mile-an-hour road. They are reducing all the stimulation down to a very slow speed so that they can manage it. However, driving 15 on a 40-mile-an-hour road is not safe either.

Evaluation Outcomes

- Able to drive safely

- Need intervention to drive safely

- Unable to drive safely

Once I have my whole battery of clinical assessments and I have tested them on the road, as I do with any other evaluation, I synthesize all that information together.

The Intervention Plan

- Driving is an occupation

- The plan should support occupational engagement

- Consider all possibilities

- Intervention includes:

- The client's goals within an occupational framework

- The planned intervention approaches

- Recommendations or referrals to others

They might need some interventions that can help them to drive safely, or I might determine that they cannot drive safely. If I decide somebody needs some intervention, I must develop a plan, remembering that driving is an occupation. My plan should support all occupational engagement, not just driving.

The Goals

- Must balance independent performance with safety

- Should meet client's need for desired community mobility

- Should consider all possibilities of intervention approaches

- Should foster engagement and participation in community mobility

We should look at the client's goals within an occupational framework. I plan out my intervention approaches, and I might make some recommendations or referrals to other disciplines. When setting my goals, I always try to balance performance and safety. I look at their desired community mobility, how much they need to get out and about, and how I help them do that.

Intervention Approaches

- Create or promote occupational performance

- Establish or restore occupational performance

- Maintain occupational performance

- Modify occupational performance

- Prevent deterioration of occupational performance

(AOTA, 2020)

I consider all the intervention approaches, which we will go over in a minute. Ultimately, I try to foster engagement and participation in community mobility and in the community. Those community-based occupations give that person increased quality of life and health. They may be going to the grocery store, the doctor's office, a Tuesday afternoon hair appointment, a Thursday morning bridge match, or whatever occupational engagement is important to them. This is what I am trying to support.

In looking at my options, I will back to the OT Practice Framework and use different intervention approaches.

I might create or promote occupational performance. I could also establish or restore, but I would most likely be restoring routines, as these are older adults. I might see somebody who is fairly healthy and try to maintain their occupational performance. One of the biggest areas I use is modifying their occupational performance. I also want to look at prevention because I know that there are lots of risks associated with driving and community mobility. There are many things that we do every day, from adjusting our mirrors properly to wearing seat belts that will prevent injuries and prevent deterioration of occupational performance.

Intervention Approaches: Create/Promote

- Identify transportation alternatives

- Facilitate registration for transportation services

- Travel training for clients in the use of transportation alternatives

- Coordination of service delivery

- Explore virtual engagement opportunities

- Education re: social programming within the client's community

- Promotion of walking and bicycling programs

in terms of creating or promoting interventions, these are opportunities where I can create something brand new for somebody, like identifying a transportation alternative. I might teach somebody how to use Uber or Lyft using an app on their phone and walk them through it. I might register them for paratransit services or some bus system in their town or get them linked up with a group through their church for rides to and home from church. I might do travel training for somebody who is going to transition to the bus. I do want to caution, though, that just saying, "Do not drive your car anymore. Take a bus." is not the appropriate transition for everybody. All things that will cause difficulty in driving safely may also be an obstacle to using the bus. For example, if they cannot see well enough to drive, they probably cannot read a bus schedule. If they do not have adequate cognition to plan out and navigate a route through the community, they will most likely incur difficulty with bus changes or figuring out the schedule.

For some folks, travel training can be effective if it is a supportive door-to-door or curb-to-curb transportation service teaching them how to call and schedule, pay for it, and that sort of thing. This may be a whole new mode of mobility for them.

You might also coordinate delivery service. This exploded with the pandemic. Anybody can get groceries delivered now, and there are many resources, including drug delivery. I once lived in a county where the public library had a mail system where you could check out books from the library, and they would be mailed to your house with a postage-paid envelope to send the books back. You need to help them find these types of resources.

You might explore virtual engagement opportunities. Many of us did this when the pandemic started. We want to help our clients continue being socially engaged. We have learned a lot of lessons during the pandemic that we can now apply to folks who cannot drive anymore. How do we help them access telehealth? How do we help them engage socially with people through a virtual context? It is a great resource that I do not know that we take full advantage.

We may also look at social programming available within the client's community. What resources are available right there they do not have to get out and about?

There are walking and biking programs. Research shows that people who regularly engage in walking or biking programs also increase their driving longevity. And it might be a whole new mode of mobility. Again, if somebody has impaired vision, cognition, or motor skills to the point where they cannot drive, jumping on a bike might not be the best option. You want to use appropriate judgment in all of these areas.

Intervention Approaches: Establish/Restore

- Exercise Programs

- Strength / ROM / Coordination

- Cognitive Retraining

- Memory / Attention / Reasoning / Safety

- Medical Interventions

- Surgery (cataract removal)

- Medication changes

For establish and restore, these interventions are for folks who have lost skills because of an illness, an injury, muscle loss, or what have you. We might instruct them in exercise programs to improve their strength, range of motion, coordination, or motor skills.

We might be restoring cognitive skills through cognitive retraining. Some people might need medical interventions, which we cannot do, like cataract removal. If somebody's vision is impaired because of their cataracts, I will send them to the eye care specialist. Then we can come back and revisit driving. Medication changes are also not our realm, but if somebody has Parkinson's, for example, I may want to pay attention to what is going on with their medication and work with their doctor to change their medication schedule. We want them at their peak medication levels to decrease their rigidity and tremors when they need to get out and about in the community.

Intervention Approaches: Maintain

- Didactic classroom courses

- Hands-On Driver Refresh Courses

- Self-assessment

- Walking wellness program to maintain balance and agility

- Maintain medication schedule with timers and medication boxes

Our next option is maintain interventions. This is important for people who are healthy and doing fine. Still, we want to maintain their driving ability and get out and about in the community. There are a lot of didactic classroom courses offered by AARP, AAA, and the National Safety Council to refresh their skills and knowledge. Many insurance companies will give discounts for attending these classes. Some classes are better than others, and the expectations or requirements for engagement vary considerably. You can sleep through some of the classes and still get your certificate. Remember that your client signing up for a class does not necessarily mean they have acquired those skills.

There are lots of hands-on refresher courses. Many driving schools offer these, especially in an elder-dense area like South Florida. They can get behind the wheel and practice driving and maneuvering. This course can be very handy, particularly for older women who have lost their spouses who did much of the driving.

Self-assessments are offered by AAA and AARP, but they do not tell you whether or not you can continue driving. They will tell you enough that it is time to start paying attention.

Walking wellness programs can be great for maintaining balance and agility, which also has some trickle-down benefits for driving longevity.

Lastly, maintaining medication schedules with timers and boxes is all part of a "maintain" intervention.

Intervention Approaches: Modify

Modifying the Context

- Compensate for limitations

- Compensatory strategy education

- Adaptive techniques

- Use of environmental modifications

- Adaptive equipment

- Considerations

- Use caution for clients with progressive dementia and other cognitive impairments

- Ability to learn to use new modifications or use them consistently may be compromised

Modification is the biggest area of intervention, particularly for specialists. We may modify occupational performance, educate in adaptive techniques, or use environmental modifications and adaptive equipment.

Whenever we are doing modifications, we want to be careful with people with progressive dementia or other cognitive impairments. If somebody has cognitive changes, that affects their ability to learn to use new equipment. We do not want to start throwing a bunch of equipment at people as they may be confused and could become more dangerous.

I do not know how old everybody is, but I am sure most of us learned to drive holding our hands at the two o'clock and 10 o'clock positions. We also learned hand over hand to turn the steering wheel. This was all before airbags were invented. Once airbags were invented, they started seeing a pattern of upper extremity and facial injuries. If you are holding the steering wheel at two and 10 and the airbag goes off, your hands and arms will come towards your face at 200 miles an hour. Once they saw this pattern, they started teaching them to hold the steering wheel at the bottom at four and eight. The entire automotive industry knows that it is no longer safe to drive at two and 10. Still, only the new drivers are being taught to change because it is considered more dangerous or confusing to re-habituate an entire cohort of older adults to change. Eventually, all the new drivers will have learned to drive in consideration of airbags. We want to be careful about changing behaviors when it is not realistic.

Modifying the Activity Demands

- Adapt/change the context to match skills and abilities

- Physical Context

- Change driving route

- Lighter traffic

- Better lighting conditions

- Temporal Context

- Change time of driving

- Avoid rush hour

- Limit driving to daylight

- Coordinate with optimal medical times

- Physical Context

I might modify the context to match somebody's skills, like a driving route. "This street is too busy and dangerous to drive on. We'll give you a different route to drive on instead, one with lighter traffic."

We can also change the temporal context, like the time of day. For somebody who cannot handle all the stimulation on the road, we might say, "Do not drive during rush hour." I might limit somebody to daylight driving only. Some states will put that on your driver's license as an official driving restriction. Again, I might coordinate with optimal medication times as well.

Modifying the Vehicle

- Therapists should never modify a vehicle

- Only trained specialists should recommend adaptive equipment

- Clients should be trained on equipment prior to installation

- Equipment needs are unique to the client

I might adapt or change the vehicle so that the person can get in and out, sit properly, or operate those vehicle controls. We want to employ compensatory strategies so they can drive safely.

If I am talking about modifying a vehicle, there are some pretty hard and fast rules about this. As a therapist, you should never modify a vehicle unless you are a certified automotive mechanic.

And only a trained driving rehab specialist should make recommendations for adaptive equipment. The clients should always be trained on the equipment before it gets installed in their vehicle until they demonstrate they can do it safely and consistently.

Equipment needs are unique to the client. Even the same equipment for two clients might get installed differently, as there is no one-size-fits-all.

From Assessment to Installation

- Equipment and/or modifications should only be performed by competent vendors/mobility dealers

- Dealers should be certified to install the products and should be a member of NMEDA

- Vehicle modifications must meet FMVSS established by NHTSA

- Individuals should be trained in equipment use to ensure safety

- Driver's license must reflect the adaptive equipment

There is a lot that happens between assessing somebody and determining the need for equipment and when it gets installed. Installation should only be done by a competent vendor or mobility dealer. NMEDA, the National Mobility Equipment Dealers Association, is a professional organization of dealers who are certified to install products. They have a code of ethics that says they should not install equipment unless they get a prescription from a therapist. A code of ethics is in place so that their members are not taking advantage of older adults who want anything and everything installed that they may not or do not know how to use.

When looking for a dealer as a generalist or specialist, you want to look for somebody that is a member of NMEDA to make sure that they are legitimate. All vehicle modifications must meet Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards established by the federal government via the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. For example, every part of a vehicle has Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards that pass tests for strength and durability, even the screw that holds the visor in place. They do not want parts to explode or crack apart when a car crashes. They have to be able to sustain a certain amount of force.

People should be trained in the use of their equipment to make sure they are safe, and their driver's license should reflect that adaptive equipment. I wear contacts, and my driver's license has an accommodation that says I must wear corrective lenses. I have to wear those corrective lenses; otherwise, I am not following the limitations of my license. If somebody needs hand controls, for example, it should be designated on their driver's license.

Commonly Used Equipment

Let's look at some of what this commonly used equipment looks like. There are lots and lots of steering devices.

- Spinner Knob Considerations

- Most frequently used steering device

- Requires functional grasp

- Mounted within available reach

- Often recommended secondary to another necessary adaptation

The most frequently used steering device is the spinner knob in Figure 8.

Figure 8. Spinner knob (personalmobilityinc.com).

It is shaped like a doorknob, and it pops in and out of this little box. I can change this terminal device, depending on somebody's hand function. It can be a post, a tri-pin if the person is a quadriplegic, or have an amputee hook on there. It all works the same. There is a ball-bearing device to allow a person to steer with one hand. This steering wheel will go around without ever having to release that knob. It requires you to have a functional grasp, and it is mounted within available reach.

Where it gets mounted on the steering wheel, whether the five o'clock, two o'clock, or 12 o'clock position (hopefully not), is how we write it in the prescription depending on the person's car, reach, shoulder strength, or where it is most comfortable. Many people get this piece of equipment, secondary to needing another piece of equipment we will see on the next slide. If the left hand is busy, that would only leave them one hand left to steer.

- Hand Controls Considerations

- Replaces use of vehicle-installed accelerator and brake

- Multiple planes of movement for operation

- Client ROM, strength, vehicle, and size of occupant cabin dictate which controls

- Original pedals still work for other drivers

- Takes considerable practice to acclimate to new motor habits

This person has a spinner knob because they only have hand controls, as noted on the left (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Hand controls (personalmobilityinc.com).

This is s fairly common pairing. The hand control is a fairly low-tech piece of equipment that replaces the need to use your foot on the accelerator and the brake. They come in lots of different models, which are distinguished by the planes of movement. It might be push-pull, push-right angle, push-twist, or push-rotate, depending on what movements are used to operate it. Rods go from this device and attach to the foot pedals. If somebody else were to get into the car, they could drive it just fine with their feet with a quick adjustment.

I look at their upper extremity and what range of motion, strength, and endurance they have to keep that hand control operating all the time. I also have to look at the car. A Porsche or a Corvette has much less cabin room and movement for pieces of equipment. Thus, I might use a different piece of equipment compared to this one.

Anybody who needs this adaptive equipment and cannot take advantage of the factory-installed equipment may be eligible for a rebate program. For example, if you buy a Ford and need hand controls, they typically have a $1,000 to $2,000 rebate that can be used toward a new car.

- Pedal Block Considerations

- Prevents accidental lower extremity application of gas/brake by users of hand controls

- For individuals with uncontrollable lower extremity movements, which may include spasms or other movements

Another commonly used equipment option is a pedal block (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Pedal block.

This is essentially a steel box that hooks right onto the floor. It can be removed very easily with a release pin. It is used so that someone does not accidentally operate their foot pedals, like if they have extensor tone or a lower extremity prosthesis.

- Pedal Extender Considerations

- Allows reach to foot pedals while maintaining a safe distance from the airbag

- Can be clamp on- allowing 1-4 inches of extension

- Can be adjustable fold down to allow 6-12 inches of extension

Figure 11 are pedal extenders.

Figure 11. Pedal extenders.

Pedal extenders bring the pedals closer to the person. They are used with people of short stature, like dwarfism, or older adults, particularly women. Many lose height as they age, and they have difficulty getting close to those pedals but staying far enough away from the airbag. Some vehicles come with factory installed. A line of Ford, Mercury, and Lincoln vehicles come with this option factory installed and will extend them by two inches. As a vertically challenged person myself, I know someday I will need these.

- Specialty Mirrors Considerations

- Typically convex to expand viewable area

- Assists drivers in seeing vehicles in their blind spot without distorting the image

- Important for individuals with limited neck and trunk mobility

Other commonly used equipment is specialty mirrors, as seen in Figure 12.

Figure 12. Specialty mirrors (Top Imperialsupplies.com, Bottom https://www.dealnay.com/).

If somebody cannot turn to see behind them due to neck stiffness, a cervical fusion, or vertigo, these may help. They expand how much of the driving environment you can see.

- Seating and Transfer Assist Considerations

- Seating and transfer needs are not only for the drivers

Some folks need equipment that they can get in and out of the vehicle or related to their seating. Some options are shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13. Seating options for transfers (Left www.onthegomobility.com, Right Amazon)

The left seat option is pretty cool, but it is not cheap. Notice it is on the passenger side. Your clients may need it to ride as passengers. This seat rotates 90 degrees, comes out of the car, and drops down. It operates by power and puts the person back into the passenger side. This option makes for easy transfers. Depending on somebody's mobility limitations and their caregiver's ability to do those transfers, this seat may be handy. However, this seat, to my knowledge, has not ever gone through safety testing.

Another fairly simple seat is this lazy Susan with ball bearings. It helps to rotate the client around to face the right way. I do not know how this would stand up during a crash, and I have never recommended it to anybody. However, many clinicians have this on their list.

Intervention Approaches: Prevent

Population-based

- Population-based interventions provide strategies to improve health, support performance, and prevent negative outcomes for communities and larger groups

- Educating drivers and passengers

- Working with community design professionals

- Vehicle design

- Health fairs

- Community presentations

- Driver-vehicle fit screening programs

The next approach for intervention is prevention. We want to prevent people from getting injured. I did not get too much into the causes behind the injuries and fatalities, but older adults do not necessarily drive worse or crash more. However, due to their aging bodies and decreasing bone density, their bodies cannot sustain the energy forces of a crash in the same way a 30-year-old would. When older adults are involved in a crash, they are more likely to get killed or injured than their younger counterparts. This is why these prevent interventions can be important to educate drivers and passengers so that they stay safe.

You may do prevent interventions with community design professionals. For instance, I worked with a city that had a very large retirement community right across the street from a high school using the same intersection. When the high schoolers came and left school in the early morning, and late afternoon hours, the older adults were using that intersection simultaneously. This community had approximately 60,000 residents over the age of 60. We closed that entrance and moved it about 3/4 of a mile down the street beyond the high school. Now the two highest-risk road users were not using the same intersection simultaneously. That is a "prevent" strategy.

We can also work with vehicle designers to make vehicles easier to use, easier to enter and exit, and also more protective of aging bodies. There is much we do to protect children in vehicles, particularly infants because their bony structure will not allow them to sustain the energy forces of a crash. Why are we not doing the same thing for older adults?

You may provide education at health fairs or to senior or retirement communities to alert them to prevent-style interventions.

- Driver–vehicle fit principles

- Allow 3 seconds following distance behind vehicles

- Stop behind vehicles where driver can see the bottom of rear tires of vehicle to the front

- Turn left at intersections with a left turn signal

- Hold steering wheel at 4 o'clock and 8 o'clock

- Seat children under age 12 in the back seat

There are also driver vehicle fit screening programs, like CarFit. These ensure that people are educated and use their vehicle safety features properly. Some of the go-tos prevent interventions are the driver vehicle fit principles shown above. These are things that older adults forget about or did not learn about since they were 16 years old. Often, they can use these refreshers.

For example, when they stop at a light, they should be able to see the rear tires of the car in front of them and where those rear tires hit the road. If they cannot see where the rear tires hit the road, they are stopped too close behind the car. If they are rear-ended, they hit the car in front of them. They also need to take advantage of left turn intersections and signals rather than turning randomly at an unregulated or unprotected left turn, as we know that left turns are much more difficult to navigate.

I already talked about where to hold the steering wheel not to get injured by airbags.

It is important to seat children under 12 in the backseat. There is a whole area of older driver safety that we have not even gotten into. Many grandparents transport their grandchildren, but the current child passenger safety guidelines did not exist when they had children. Helping older adults understand that children under 12 should go in the backseat and how to use car seats properly is critical as well.

Recommendations for Cessation

- Clients need to remain mobile in the community

- Consider their other engagement needs

- Identify other modes of transportation to meet their needs

- Assist with application for paratransit

- Provide travel training using transit

Sometimes, we must deliver unpleasant news and tell clients they need to cease driving, as it is not safe. We need to start looking a little bit more, as a profession, at what we are doing for these folks who need to remain mobile in the community, but it is not safe for them to drive anymore.

We also need to consider their other engagement needs, as they are occupational beings, and look at other modes of transportation to meet their needs. For instance, how do we assist with applications for paratransit and provide travel training?

Another huge role for us is working with the transit agencies doing assessments for paratransit eligibility. Paratransit is extremely expensive for a transit agency to operate and provide those services. Think about how much an Uber would cost every time you had to go 10 or 15 miles. That would start to add up for the agency. We can do assessments for paratransit eligibility. If they are not eligible, could we meet their needs by offering some travel training using the fixed-route buses?

Resources

- AOTA Older Driver site

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration

- The Hartford

Here are some resources that might be helpful. The AOTA has an older driver site, an entire website dedicated to older drivers.

This is funded by NHTSA or the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. They have recognized for many years the important role of OT in meeting the needs of older drivers. There are plentiful resources on this site. NHTSA has multiple sections, but there is an older driver-specific section with many resources.

The Hartford is what I mentioned earlier. They have multiple booklets to help families and older drivers who are having some issues with driving. It can be a great resource. They work very closely with the MIT AgeLab.

References

American Occupational Therapy Association. (2020). Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process (4th ed.). American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74(Suppl. 2), 7412410010. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2020.74S2001

American Occupational Therapy Association. (2016). Driving and community mobility. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 70(Suppl. 2), 7012410050. https://dx.doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2016.706S04

American Occupational Therapy Association and ADED (2014). Driver rehabilitation programs: Defining program models, services, and expertise. Occupational Therapy In Health Care, 28(2),177–187.

Chihuri, S., Mielenz, T. J., DiMaggio, C. J., Betz, M. E., DiGuiseppi, C., Jones, V. C., & Li, G. (2016). Driving cessation and health outcomes in older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 64(2), 332-341. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.13931

Federal Highway Administration. (2022). Next-Generation National Household Travel Survey. Retrieved from https://nhts.ornl.gov/od/

National Center for Statistics and Analysis. (2021, May). Older population: 2019 data (Traffic Safety Facts. Report No. DOT HS 813 121). National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. https://crashstats.nhtsa.dot.gov/Api/Public/Publication/813121

Stav, W. B. (2015). Occupational therapy practice guidelines for driving and community mobility for older adults (2nd ed.). AOTA.

Stav, W. B., & Lieberman, D. (2008). From the desk of the editor. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 62(2), 127-129.

Strogatz, D., Mielenz, T. J., Johnson, A. K., Baker, I. R., Robinson, M., Mebust, S. P., Andrews, H. F., Betz, M. E., Eby, D. W., Johnson, R. M., Jones, V. C., Leu, C. S., Molnar, L. J., Rebok, G. W., & Li, G. (2020). Importance of driving and potential impact of driving cessation for rural and urban older adults. Journal of Rural Health, 36(1), 88-93. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12369

US Census Bureau. (2022). American Community Survey. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs.html

Questions and Answers

Were older adults the ones that caused the fatalities?

In that national database, it does not say who caused it. They do split down the data between whether it was a driver or passenger. The cause is incredibly difficult to determine, and it does not end up in the injury or fatality databases.

What age are we using to define older adults?

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, a division of the US Department of Transportation, typically uses 65 as the threshold for older adults in most of their data. If they do not, it typically says it on the table. There will be additional data on those 85+, which they recognize as old-old.

Can you talk more about causation and accidents?

This is an extremely complicated issue. Many instances happen that do not ever get reported, like when someone drives over their mailbox, drives through their garage door without opening it, or something happens on private property, like in a grocery store parking lot. If law enforcement does not get involved, it does not get reported. Some states have rules that there has to be a minimum dollar amount of property damage to get reported. I would say that these numbers that I am reporting are on the conservative side and are probably a whole lot higher.

There is also law enforcement leniency, which is a legitimate thing. They feel bad if it is an older adult and let them go.

Can you define generalists again and their role?

A generalist can decide if clients are safe with the skills they have attained. Somebody who has had a stroke and makes an almost immediate recovery without residual deficits is easy to make recommendations because you are watching them do complex, functional tasks. The other end of that continuum is where somebody is grossly impaired, where they cannot sit independently and remember where they are. These two ends of the continuum are very easy to determine whether a person can continue to drive or should not drive. It is the big, giant gray area in the middle where the referrals get made.

In acute care, the specialist is not providing any client care, but they could give the generalist a heads up on what red flags they may see. You want to be careful that if the generalist and the specialist talk to each other, everybody is not using the same assessment tools; otherwise, people can learn them.

Specialists can also inform generalists about community resources, including driving evals and where vehicles can get modified, and transit options. Do not do this without a prescription.

The final step is outpatient, where the specialist will evaluate driving, do the whole eval, and determine medical fitness to drive. They may also provide some intervention or assist with driving cessation.

Are you required to inform the DMV, or another agency, if the client is demonstrating the desire to drive, despite the recommendation not to?

That is a great question. There are a few states in this country that have mandatory medical reporting laws, like California, Pennsylvania, and a couple more. As an OT, you are never required to report. Most of the language says that you may report, but you are not required to do so. My take on it (not a legal take) is that if you know that somebody is planning on driving and you do not think that they should, I view it almost like a domestic abuse case. I feel I have an ethical obligation to report that. I would report somebody if they were going to drive.

In fact, over 20 years ago, that is exactly how I got interested in the practice area. When we would be sitting at rounds at the rehab hospital, somebody would say, "Oh, Mr. Smith is planning on driving when he goes home." People would say, "What's his address so we can stay out of that neighborhood?" I thought, "What about all his neighbors? That's not fair to them." We should be looking at medical reporting and making sure that people are not driving if it is not safe.

In relation to memory deficits, at what point do we need to contact the authorities about the patient being unsafe?

For people with dementia, getting lost when going to familiar places is typically the first sign that you need to transition out of driving. Some great resources from The Hartford are also on AOTA's website. They have some great brochures and checklists of behaviors that you can go through. Somebody with a memory diagnosis should hear, "You know, at some point, you won't be able to drive anymore." They can even sign a "contract" that says, "I promise that when you tell me that I cannot drive anymore, I won't."

Is there mandatory reporting for an event?

An event meaning a crash? Not all events are reported, depending on if it is private property or not. Again, OTs are not mandatory reporters. Typically, law enforcement or doctors are required to report.

Is medical paperwork required?

Every state differs. Most states that have a medical reporting system as part of their medical advisory board will have a form either online or something that you can download. I also tend to send my entire full evaluation report. In Florida, for example, when you report somebody, it is a fairly quick online form. A letter then goes out to the client that says, "You've been reported. Take this form to your doctor and have your doctor fill it out." It is important to contact the medical advisory board in your state so that you know the sequence of events and what is going to happen in case you file a report.

In Florida, there is also anonymous reporting. You do not have to identify who you are, but I always do, and they cannot sue you. There is legal immunity, and you cannot be sued for filing a medical report because you were doing it to protect the public's health.

Do clients have to have a referral from a doctor to see a specialist once the generalist recommends it?

Anybody can come to an OT and get a driving evaluation without a prescription. Remember, typically, a referral or prescription from your doctor is to prove to the insurance company that the services are medically necessary for insurance to pay for them. This comes to the second half of the question. In most cases, health insurance will not pay for a driving eval.

If you do not have to prove to anybody that the services are medically necessary, then technically, the client does not need a referral from the doctor to get a driving eval. That is the official stance in terms of licensure. That said, many facilities will require a prescription for risk management purposes. If it is a private practice, this is not necessarily true. In most cases, health insurance does not pay for these services because Medicare does not believe driving is medically necessary, and everybody follows suit.

Do you know of a resource handout for all the driver rehab specialist locations in the US?

Yes, there is a listing on the AOTA older driver site and on ADED.net. ADED is a professional organization of driving rehab specialists.

Can adaptive equipment be used on smart vehicles?

That is a good question. The mobility equipment dealer would be the best person to answer that question. I will tell you that probably within our lifetime, many of our issues will be alleviated because of smart vehicles.

Are there any locations in Florida that provide certification to become a driving rehab specialist?

Certifications are not state bound. You can become a CDRS, a certified driving rehab specialist through the ADED. It is an exam-based certification. AOTA phased out its certification. You could be specialty certified in driving and community mobility, and they phased it out.

Do you need to pass a driving test again with the modifications?

Typically no. You have trained with a driving rehab specialist. You submit paperwork to get the modification on your driver's license.

Citation

Stav, W. (2023). Optimizing mobility and community engagement for older clients. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5597. Available at www.occupationaltherapy.com