Introduction

I am happy to be back with occupationaltherapy.com today to talk about thumb arthoplasty. Most of my experience has been in adult physical disability in outpatient hand therapy. As such, I know how common and challenging it is to treat individuals who have hand or thumb arthritis. In my current work setting, I am lucky because my patients come to me after seeing a doctor, or they have a diagnosis and a clear prescription for treatment. However, my patients do not always have an understanding of what that means. They will come in saying things like, "It's going to go away, right?" Or, "We're going to fix it, and then it'll be gone." "I can just do some exercises." They may even say, "The doctor said that I might have to get surgery." Doctors may not have the time to explain all of those implications, and it is the occupational therapy practitioners who do. We can apply the implications to occupational performance, performance patterns, habits, and routines. Thus, it is important that occupational therapy practitioners know how to provide this education.

Even outside of hand therapy, many clients may have a comorbidity of arthritis in the hands or the thumbs. Even when I was working in a community setting with well-elders in Philadelphia, many of them were experiencing hand and thumb arthritis. I am sure this is the case in a lot of settings like skilled nursing, acute rehab, and things like that. The bottom line is that occupational therapy practitioners need to know how to temper clients' expectations and provide a sound education, especially on what to expect after surgery.

If a client is going to have surgery, they need to know what to expect afterward. This became really apparent to me when a coworker of mine, who is an occupational therapy practitioner, was having some issues with thumb arthritis. In fact, many OTs and PT practitioners have arthritis due to hands-on manual work. She had tried conservative options, and her doctor mentioned surgery. When I started telling her about what that meant, she said, "He didn't tell me any of this."

I thought it was important to this information up as an overview about what happens after these thumb arthroplasties.

How Important Are Your Hands?

- “40-60% of hand use depends on a normal, healthy thumb.”

(Albrecht, 2015; Scott, 2018)

Here is a silly question. How important are your hands? There are nine areas of occupation according to the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework (OTPF). This is everything from ADLs, to health management to leisure activities to play activities. When we think about what we do with our hands throughout the day, it is not only engaging in these activities and occupations but other things like communication. We use our hands for sign language, giving a thumbs up or a high five, showing emotions, patting somebody on the back, or blowing somebody a kiss.

Out of all these movements, how important are your thumbs? There is a statistic that says 40 to 60% of hand use depends on having a normal, healthy thumb. Disability from something like CMC osteoarthritis in the thumb can impact the use of the entire hand.

CMC Osteoarthritis

- Gender

- 15% of females; 7% of males show radiographic evidence

- Age

- Over 65, 99% women & 78% men will have x-ray evidence of OA

- 60-70% seek medical attention

- Other Factors

- Genetics, trauma, inflammation, overuse

(Dilek et al., 2016; Ataker et al., 2012)

Here are some statistics about it. If we look at gender, this is going to impact females more than males for some very specific reasons. I will get to those in a second. A comparatively shocking statistic is that up to 15% of the population over 30 has symptomatic CMC osteoarthritis. This comes from a study by Higginbottom and colleagues, which is in the reference slide. I have always heard that the thumb has about a 30 to 35-year-old warranty. So if you are over 35, you may start seeing some of these problems arise. They may be symptomatic or only show up on an x-ray. The lifetime risk of somebody getting symptomatic hand osteoarthritis or osteoarthritis is about 40%. That is a pretty high statistic.

If you are going to have hand osteoarthritis, the first CMC joint is most commonly affected. It affects women over men primarily. This is because of hormonal changes that happen in women. Post-menopausal women lose estrogen. They also have more shallow and thinner cartilage than men. Thus, you are going to see the statistics tip more in favor of women than men for being symptomatic or having x-ray evidence. You can also have x-ray evidence of osteoarthritis without being symptomatic at all.

When you are symptomatic, this is when somebody typically seeks medical attention. These numbers become pretty staggering when you look at a population of over 65. And, in the older adult years, 99% of women and 78% of men will have x-ray evidence of osteoarthritis. Again, they are seeking medical attention because they are having symptoms.

Other things that play into this diagnosis of osteoarthritis are things like genetics. Family history is going to make you more likely to have it. Having trauma, either having fractures or dislocations, or previous injuries in the hand may predispose a person to develop this later on. Inflammatory diseases and overuse may also be factors. The more you use your hands, the more they are going to wear out over time, unless you really protect and take care of them.

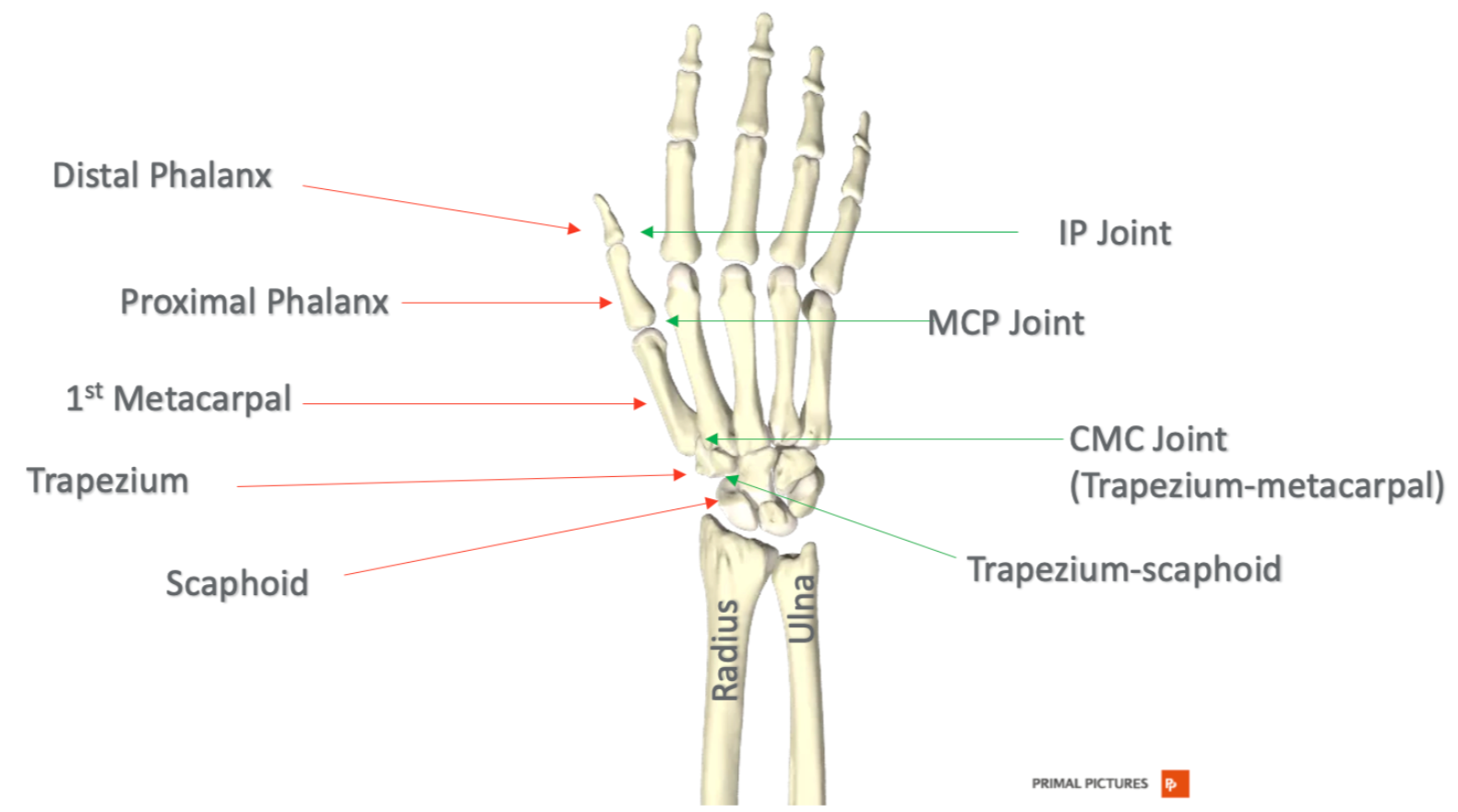

Thumb Anatomy

If you are anything like me, you get confused by the thumb anatomy. It is pretty complicated. When I developed an interest in hand therapy, this forced me to learn more about the thumb. I think it is very helpful to start with an overview of that in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Thumb anatomy. Click here to enlarge the image.

If you look at the red arrows, this indicates the different bones that make up that thumb column. The thumb is not like the other four digits for a lot of reasons—one of them being that it has one less phalanx there. There is a distal phalanx and a proximal phalanx. The thumb distal phalanx is at the top, then the proximal phalanx, and then moving down to the metacarpal. The first metacarpal is part of the thumb. This articulates with the distal row of carpal bones at the trapezium, which then moves to the proximal row of carpal bones of the scaphoid.

The joints can be seen with the green arrows. There is only one IP joint versus two in the rest of the digits. The IP joint is at the tip of the thumb. Moving down, you can see the MP joint. Finally, the CMC joint is at the base. This is where that first metacarpal articulates with the trapezium carpal bone.

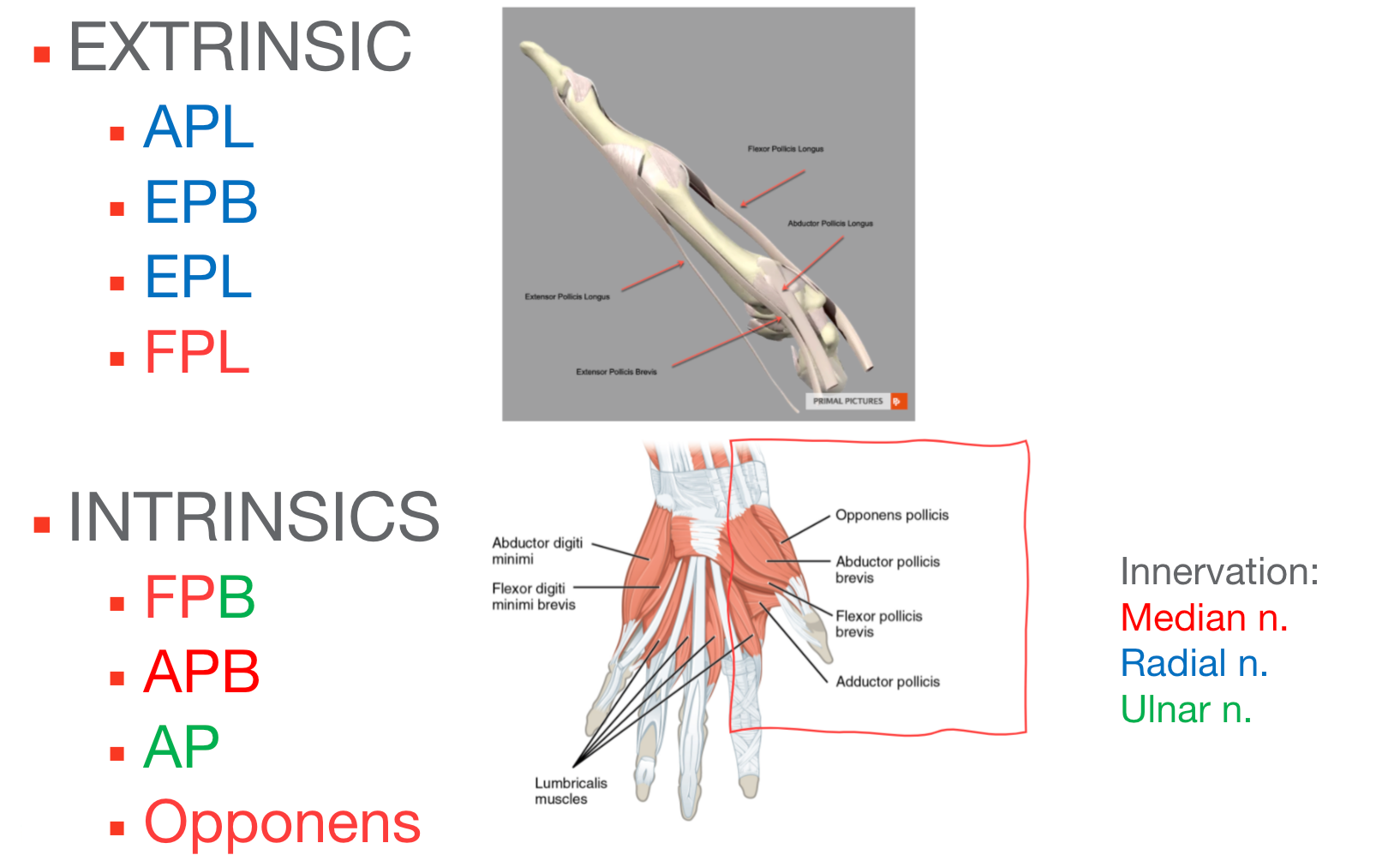

Thumb Muscles

Looking at the muscles, the thumb has exceptional mobility. This is mostly due to the fact that the CMC joint at the base is a saddle joint. Being a saddle joint, it is going to have a lot of movement. This movement comes from at least eight muscles that act on the thumb, including both extrinsic and intrinsic muscles. And, the innervation is provided by three different nerves, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Thumb muscles. Click here to enlarge the image.

You can see that I have color-coded this. Let's start with those extrinsic muscles. Extrinsic just means that those muscles are going to originate proximal to the wrist, somewhere up in the forearm. They move distally across the wrist and then insert down in the hand area. The extrinsic muscles of the thumb are the abductor pollicis longus, extensor pollicis brevis, extensor pollicis longus, and flexor pollicis longus. These muscles are used for power gripping and pinching.

The intrinsic muscles are used for more precise, fine motor movements. The intrinsic muscles originate and insert within the hand. They do not cross the wrist at all. The intrinsic muscles are the flexor pollicis brevis, which has a dual innervation, the abductor pollicis brevis, the adductor pollicis, which is a very strong muscle that makes up the bulk of the thenar area in the thumb, and then the opponens pollicis muscle.

As the thumb has so much mobility, it needs to be balanced with strong stabilizers. Most of the stabilization from the thumb, unlike some other joints, comes from soft tissue like muscles and ligaments. The muscles I just mentioned help to stabilize the thumb, but there are also some really important ligaments. One of the things about the thumb is that it has a lack of what we call bony confinement. For example, an elbow is a hinge joint and is going to be limited (and stable) because of the way that the olecranon fits between the humorous and the ulna. This is not true with the CMC joint of the thumb, and as such, it is fairly loose. In fact, the CMC joint has maximum contact when it is in opposition. And, even at max contact, it is going to only have about 50% bony contact.

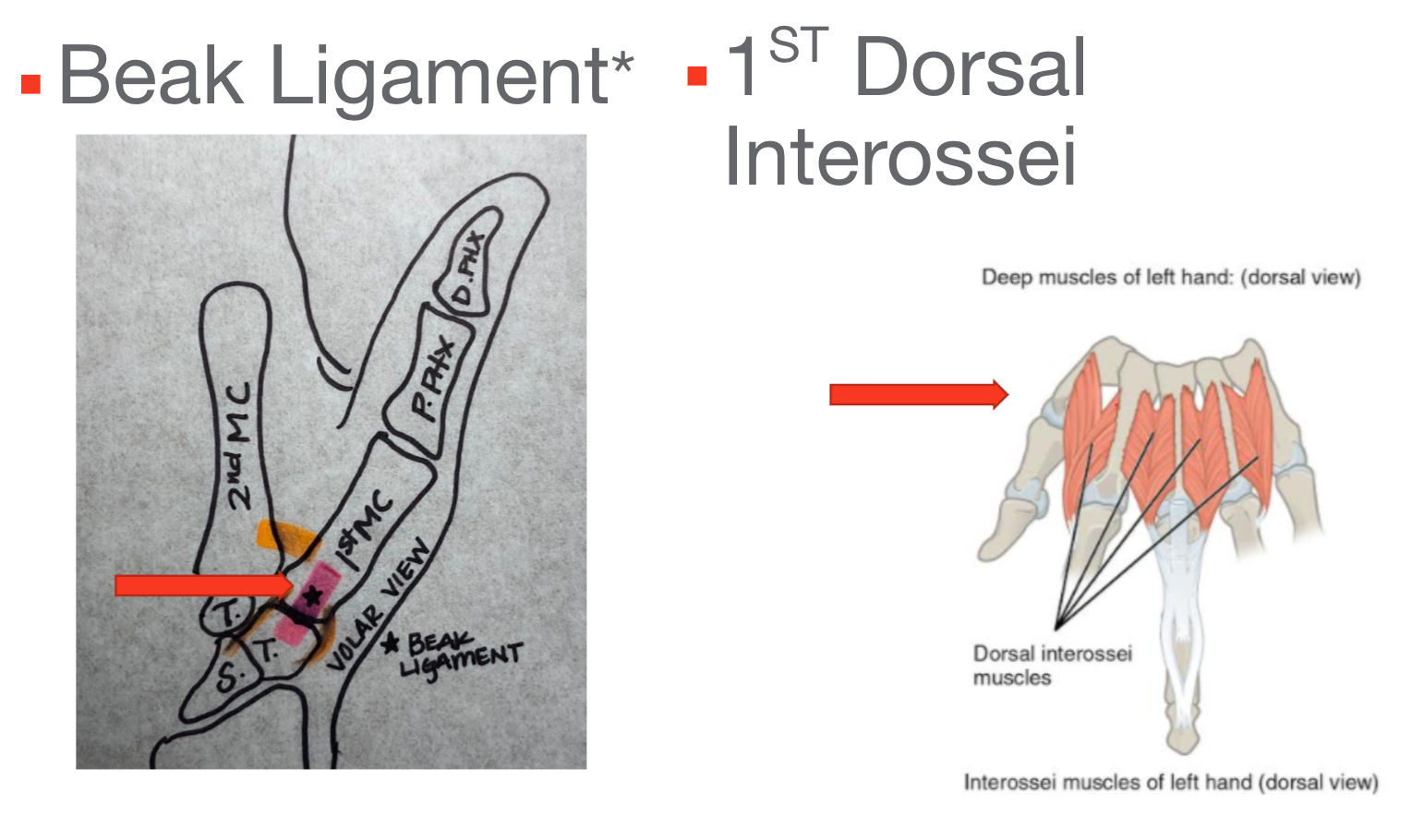

Other Stabilizers

The fact that most of the stabilization comes from soft tissue is actually a really important fact when this joint starts to break down. Figure 3 highlights the ligament stabilizers of the thumb.

Figure 3. Ligamentous stabilizers in the thumb. Click here to enlarge the image.

The drawing here shows one of the more important ligaments called the beak ligament. There are about seven ligaments that stabilize this first metacarpal, and then there are more ligaments that secure that trapezium. However, the beak ligament is probably the most important stabilizer of the thumb, and that is what is shown in pink. That beak ligament over time can sometimes become attenuated or stretched out, as do some of the other ligaments. Another thumb stabilizer that we do not always consider because it is a muscle of the hand, is the first dorsal interossei. The first dorsal interosseus is usually forgotten, but it originates on the first metacarpal of the thumb. One quick way to show this is to abduct your fingers. When doing this, try to push down on that index finger to push it in closer to the long finger. You cannot do that without the thumb tensing up. The fact that that thumb tenses up when you push on the index finger shows that there is a stabilization going on within the thumb.

Thumb Movements

- MCP/IP Joint

- Flexion/Extension

- CMC Joint

- Flexion/Extension

- ABD/ADD: Radial and Palmar

- Opposition/Retroposition

- Circumduction

- Retropulsion

In terms of thumb movements, the thumb MCP joint and IP joint are hinge joints, and they are going to only flex and extend. The CMC joint is where you get all that thumb motion as it is a saddle joint. Flexion is when the thumb comes all the way across the palm and extension when it goes back out. It also allows abduction and adduction. It can do radial abduction, which is moving away from the radius. It can also do palmar abduction in a palmar plane that is moving away from the palm. There is also opposition where the thumb meets the other fingers—the opposite being retroposition, which is coming back into a neutral position. The thumb can also do circumduction and make those nice little circles. Retropulsion is when your hands are flat on a surface, and the thumb can come up off the surface and retropulse off of the surface.

There are strong muscles that move the thumb and can make the joint unstable. For instance, extension and abduction are typically going to elongate the ligaments of the thumb and provide more stability; whereas, adduction pulls the thumb in, causing it to be more unstable. However, this is what we use for gripping and pinching. The adductor becomes really strong, but it pulls the CMC joint into its least stable position. The beak ligament tries to restrain the force to balance it out.

Thumb Strain

- Gripping and pinching

- Turning keys (lateral pinch)

- Writing (tripod pinch)

- Cleaning

- Wringing out sponge/cloth

- Opening packages

- Twisting

- Opening a jar

- Force through hand

- Weight-bearing

- Staple

As I mentioned earlier, the thumb is really important to function, and it is going to wear down over time. Things that the thumb does are really important. These are movements like turning a key. This requires a lateral pinch. Tripod is used for so many things, but writing is just one example. We do many other things with our hands like cleaning, wringing out a sponge or a washcloth, and opening packages like Ziploc bags. These activities all rely on good pinch and thumb motion.

In addition to gripping and pinching, we need to do twisting motions. This would be like opening up a jar or small cap on a water bottle.

Other things we do with our hands are things like weight-bearing through the hands or using that hand for a stable motion like pushing a door closed, pushing a lever, and things like that. The thumb takes a lot of strain.

Every amount of force that goes through the pinch gets increased as you move proximally down that thumb column. You only need about two to three pounds of pinch strength to get through daily living activities. Those two to three pounds of grip strength get magnified up to 12 or 13 times by the time it gets down to the CMC joint. This is a really important thing to consider when talking about pinch with clients. Again, the thumb balances out or resists the force of the other fingers when you are doing a functional activity.

CMC Joint Breakdown

- Joint loading – increases as you move proximally

- Muscle imbalances – leads to deformity

- Poor alignment, ligament laxity

- Overuse

- Stiffness

- Weakness

- Deformity

- Pain

- Swelling

- Loss of Function

(Albrecht, 2015; Albrecht & O’Brien, n.d.; Higgenbotham et al., 2017)

Here is what is going on anatomically. As I just mentioned, joint loading increases as you move toward the CMC joint. It gets the most force or strain during gripping and pinching activities. If there are imbalances, like a strong adductor muscle, this can lead to deformity. Likewise, ligaments can be pulled out of alignment, or ligaments can be lax whether due to an injury or be naturally hypermobile. This can be less stabilizing for the thumb and the CMC joint in particular. In addition to muscle imbalances, lax ligaments, or overuse, the CMC joint can get out of alignment. Malignment can change the protective cartilage, and it can break down. This is classic arthritis.

Cartilage, though it is avascular, gets nutrition from synovial fluid that bathes the joint during movement. Like in any joint, the cartilage is going to degenerate over time and does not necessarily have the ability to repair itself. This answers the question, "Is it going to get fixed or get better?" It is really not, but you need to manage, so it does not get any worse.

When the CMC joint does start to break down, one symptom is going to be stiffness, particularly morning stiffness or stiffness after inactivity. This can be described as a gelatin phenomenon. Jello or gelatin sets over time. It is going to get harder or more solid. If it keeps moving, it is never really going to get solid. This is the same with the synovial fluid within your joint capsule. Movement is good and nutritious for joints.

Individuals will also experience joint weakness. There will be visible deformities that we will talk about in a minute. Obviously, pain can be present and radiate up the forearm at times. This pain can also increase with grip and pinch. People can experience a tender point at the CMC joint or a warmness, a swelling, redness there.

Finally, they are going to have decreased occupational performance as a result of all of this.

Deformity Appearance

- Adduction contracture

- Unable to put a hand on a table

- Thickening of joints

- ‘Shoulder sign” of subluxation

- IP flexion with MP hyperextension

- IP hyperextension with MP flexion

(Albrecht, 2015; Albrecht & O’Brien, n.d.)

One of the big ones that you see is an adduction contracture. This muscle starts pulling the thumb in, and the webspace gets smaller. Intact large web spaces are needed for accommodating different grips. Deformities can also prevent a person from laying their hand flat down on a surface.

There is also something called a shoulder sign. I have the beginnings of a shoulder sign. It looks like a little drop-off at the CMC joint. If you would put your thumb upside down, it looks like a shoulder.

There is also IP flexion with MP extension. As the IP starts to flex, the MP will hyperextend. This comes from a very strong adductor pull. It causes the APL tendon to deform rather than stabilize, and it stresses the beak ligament.

The opposite of that is what is seen in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Hand deformities.

It is called a zigzag or reverse zigzag, where the IP joint goes into hyperextension, and the MP joint goes into flexion. This again causes stretching over time and instability at the CMC joint.

Diagnosis of CMC OA

- Appearance/observation of deformity

- Patient reports

- Positive ‘grind test’

- X-ray evidence

- Grading scale: Eaton-Littler

- Stages I-IV

- Surgery can be indicated for Stage II, III, IV

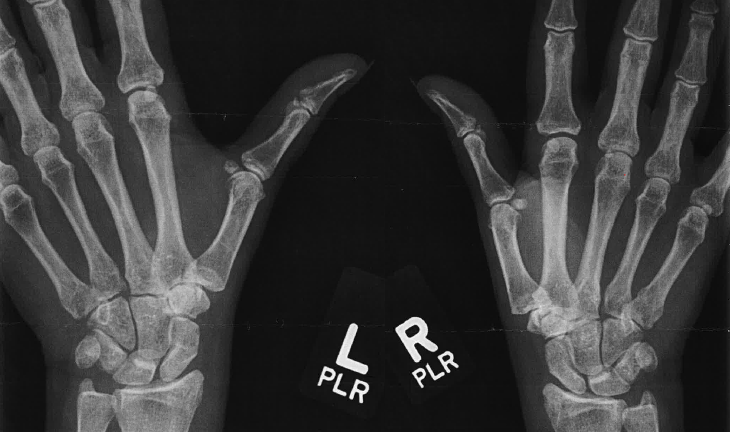

A diagnosis of CMC OA can come from both extrinsic and intrinsic sources. You can see those deformities. You can also start to diagnose from patient reports. Another thing you can do is a "grind test." This is where you take that first metacarpal and produce a rotary motion while pushing into the CMC joint. This should reproduce a grating sound or sensation. An internal exam would be from an x-ray. Figure 5 shows x-rays from my colleague who is going through this situation right now.

Figure 5. CMC OA was seen in both thumbs on x-ray.

She has CMC arthritis bilaterally. If you look at the scaphoid-trapezial space and the metacarpal-trapezial, you can see the osteophytes that are in there. After the x-ray exam, they can classify this on the Eaton-Littler scale. That is a four-phase scale I-IV, with Phase I being the least impaired. You are not going to consider surgery if the client is at only Stage I. This is going to be treated with conservative management. As you move through the stages, surgery might be considered. Therapy is going to be less effective the farther you are into these stages. There is always going to be a choice of conservative versus surgical management.

Conservative Options

- Conservative

- NSAIDS

- Orthosis

- Injection

- ‘Dynamic Stability'

- Joint Protection Ed.

(ASHT, n.d.)

I feel strongly that patient education is going to be very important because this is a diagnosis that is long term. You need to be able to explain options with your patients, especially if doctors have not done a great job of doing that. Some of the conservative options would be taking an oral medication or wearing an orthosis. There are many different options out there. That would be a webinar in and of itself of the different orthotic options for CMC OA. The options span from a thermoplastic orthosis to a neoprene sleeve. There are also Kinesio tape options. All of these are used to place the CMC joint in better alignment.

You can also opt for injections of steroids. They do not do this often as this is a very small joint with small tendons and ligaments around it.

Clients can also be educated in joint protection. This is an option for conservative treatment or post-op.

There is also the concept of dynamic stability, which I personally love during conservative management. This is by Jan Albrecht and Virginia O'Brien. They have kind of laid out how to keep the thumb movement moving while also keeping it aligned. This creates better stability within the CMC joint.

Ligament Reconstruction & Tendon Interposition: LRTI Procedure

If surgery is recommended, there are many options. The one that I am going to be talking about today is ligament reconstruction and tendon interposition (LRTI).

Overview Of Original Surgery

- Ligament Reconstruction & Tendon Interposition

- Remove damaged bone (trapezium)

- Stabilize joint

- Partial or full excision of trapezium

- Flexor Carpi Radialis (FCR)

- Other tendons can be used (palmaris longus, etc.)

- Metacarpal pin (option)

(Johnson & Goitz, 2018)

This was first introduced in 1985 by Dr. Eaton. It was the first time that they used a tendon interposition arthroplasty with ligament reconstruction using a slip of the flexor carpi radialis tendon. Earlier techniques just removed the trapezium. However, what they found was that the metacarpal would start migrating into that space, and the outcomes were not that great. Using this procedure, the metacarpal height is maintained because the slip of that tendon fills that space. All current techniques are some variation of this original surgery. Again, the advantage is maintaining the natural height of the thumb metacarpal, maintaining pinch strength, and better functional outcomes. What they do is remove the damaged bone (total excision of the trapezium carpal bone) and then do some type of technique to stabilize the joint. Sometimes, it is a partial excision of the trapezium.

The most commonly used tendon to fill that space and secure the joint is the flexor carpi radialis, but other tendons can certainly be used. Some surgeons will also use a pin, a KY, or a pin to secure that metacarpal for a period of time before it is removed. Figure 6 shows what the incisions would look like or what to expect.

Figure 6. Location of where the incision sites would be.

There is about a three-centimeter incision over the trapezium to remove that and then a one-centimeter smaller incision over the volar forearm. The incision should meet at that musculotendinous junction of that flexor carpi radialis tendon. With that incision over the thumb area, it is important to protect the dorsal sensory nerves in that area. This can be tricky and a complication.

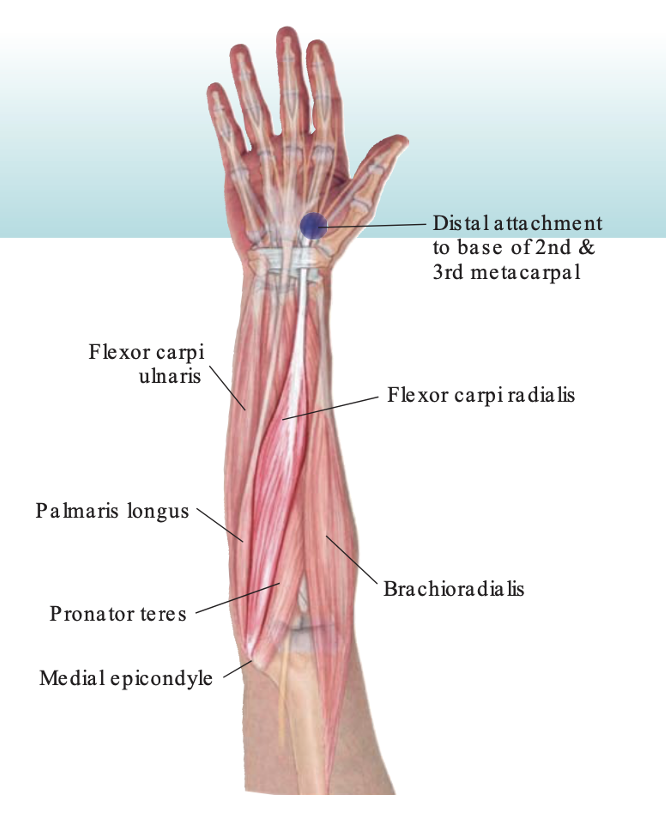

Flexor Carpi Radialis (FCR) Muscle/Other Tendon Options

- O: Medial epicondyle of humerus

- I: Base of 2nd/3rd MC

- N: Median n. (C6/C7)

- F: Radial deviation of wrist & wrist flexion

Figure 7. Location of the muscles, specifically the flexor carpi radialis on the forearm. Click here to enlarge the image.

Here is a little bit more information about the FCR muscle and tendon. The FCR originates at that common flexor origin on the medial epicondyle of the humerus. It is then going to move distally and insert at the base of the second and third metacarpal. Anatomically, this is in a good position to use. Other options for tendon harvesting would be the palmaris longus. I always call the palmaris longus a "spare body part" that we have. This tendon is used for a lot of different tendon transfers. This can either be a full or partial excision of the palmaris longus. Some use the abductor pollicis longus or APL. I even read that the extensor carpi radialis longus tendon was used. Other muscles and tendons can then take over and make up for the loss of the one used in the surgery.

"Anchovy" Procedure

- Will WF or RD be impacted?

(Johnson & Goitz, 2018)

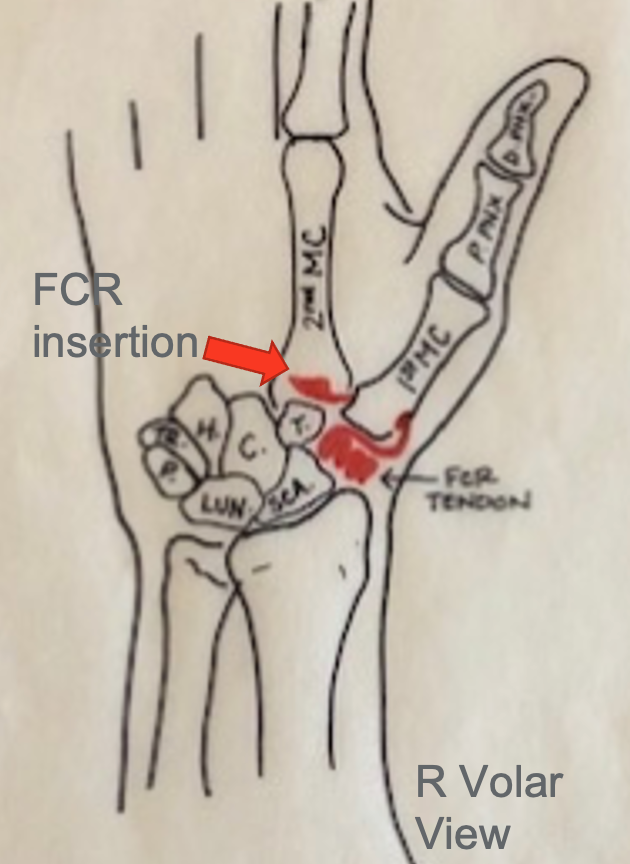

Figure 8 is my artist's rendition of what happens during this surgery.

Figure 8. Anatomical drawing on where the flexor carpi radialis is inserted.

This is called the "Anchovy" procedure. You can see that all or part of the flexor carpi radialis is going to be cut more proximally, and the remaining tendon is then threaded through a hole or tunnel in the first metacarpal bone. It is pulled through and rolled over or folded on itself to form this cushion or space filler where the trapezium was. This technique is going to be used to help as a stabilizer or reinforce that beak ligament. The metacarpal height is maintained, and stability is increased.

What is the drawback? Will there be any functional deficits from using the flexor carpi radialis tendon for a different purpose? There was a study done where they looked at risk strength. Risk strength at six months post-operation basically returned to its baseline. And after a year, nobody noticed a difference. Strength was not impacted. We know that there are other muscles and tendons that will take over and help out with wrist flexion and radial deviation. The outcomes of decreased pain, improved function, better grip strength, better pinch strength, and obviously overall satisfaction were certainly being met. They want to come out better than they went into surgery. The doctors are looking for a stable joint and maintaining that metacarpal space after the trapezium is removed. If alignment is maintained, then the patient is going to see all of those positive outcomes. Also, if the patient is guided through a strong post-op program, their recovery will be good.

Outcomes

- Decrease pain

- Improve function

- Patient satisfaction

- Maintain MC space

- Improve grip strength

- Improve pinch strength

(Dilek et al., 2016)

Here is what the literature reports about outcomes. There is an improvement in pain. They looked at pain pre-op that was restricting function and at rest. In post-op studies, there was no pain or very little pain and no functional restrictions or limitations. In terms of pinch and grip strength, they were equal to the contralateral side in about a year and greatly improved from their pre-op reports. Grip strength typically is going to recover before pinch strength. That makes sense. Both of those things did not hit their max improvement until one to two years post-op. It is a longer timeframe to get strength back after this surgery. They looked at that space where the trapezium was removed, and some space was lost. There was a study that reported about a 13% decrease in that space, but it was after nine years. And, the patients still did not report that there was an unsatisfactory outcome. They were fine.

One of the points I want to say is that, regardless of this information, you still want to educate on joint protection after this surgery to maintain good alignment, especially for the first one to two years post-op.

Potential Complications

- Radial nerve neuroma/irritation

- Rotator cuff tendonitis

- FCR "pulling" sensation

- Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS)

- The integrity of bone tunnel in metacarpal

(Johnson & Goitz, 2018)

Here is a review by Johnson and Goitz in 2018. They outlined potential complications that were seen after an LRTI. The list included things like the radial nerve neuroma or irritation, which makes a lot of sense because of how the dorsal radial sensory nerve (DRSN) travels closely in that area. There were reports of rotator cuff tendonitis, which also makes sense. If you are altering the mechanics of an upper extremity, people will use their shoulders more or in a different way. Because of the FCR tendon being split, some patients may report a pulling sensation where that FCR tendon would normally run or is running. Complex regional pain syndrome is also a risk with any hand surgery, but it came up with LRTI as well. Finally, it is possible to break the bone tunnel that is created to pull the slip of the tendon is pulled through. If that happens, then there needs to be an alternative fixation to help with stability.

Post-Op Protocols

- Protocols vary – surgeon preference

- Immobilization for healing and protection of ‘new joint’

- Balance stability and mobility in return to hand function

- Duration of up to 12-16 weeks for formal therapy

- Full return to function (grip/pinch strength and ROM) longer

(Wouters et al., 2018)

Looking at post-op protocols over the past 10 years, I had the opportunity to help create a post-op protocol for LRTI for the group of doctors in my practice. I gave them resources about what they should do after surgery and how we should progress them as hand therapists. However, I know that that protocol is a good guide, but there is no specific published protocol to use. I also found that when looking at the literature and talking to hand therapists and surgeons for some practical comparisons, that there is much variation but a similar focus. The protocols are going to vary. Some surgeons definitely have their own preferences, but all will follow the idea that the new joint has to have a period of immobilization for healing and protection. Once you do start moving, there needs to be a balance of stability and mobility to return to functional hand use. Formal therapy is usually indicated for about three months and sometimes up to four months. The outcomes typically indicate a return to a full-function grip and pinch.

So What's The Protocol? (Wouters et al., 2018)

- 27 studies with > 1,000 participants

- What type of post-op rehab is used?

- What type of immobilization is used, and for how long?

- What are the outcomes of ROM and strengthening, and how early does motion begin?

This study was a systematic review. It was published in the Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehab. They looked at the post-op protocols for CMC arthroplasty. They included 27 studies with over 1,000 participants who underwent the LRTI. They found no exact protocol. They also looked at what post-op rehab was being used, how long, the type of immobilization, and the outcomes for strength, range of motion, and early motion. Most journal articles that you find focus on the surgical technique and then jump to the outcomes, but they did not dive into a specific protocol.

- Type of Surgical Intervention

- Full or partial removal of the trapezium

- K-wire vs. no fixation vs. tightrope suspension

- Tendon use varied

- Post-op Immobilization

- Range from 2-12 weeks

- Types: Cast, removable orthosis

- Schedule: Full time at first then gradually reduced

- Outcomes all similar

This study found that the types of surgical intervention were a mix of removing the full trapezium and just partial. Some used a K wire for fixation, some used no fixation, and some used what is called a tight rope suspension which actually takes the first and second metacarpal and fixes them together for a period of time. The tendon used varied.

- Protocol Summary

- Immobilization

- Ranged from 2-12 weeks

- ROM

- Ranged from 2-6 weeks

- Strength

- Ranged from 2-8 weeks

- Immobilization

The postop and immobilization ranged from two to 12 weeks, which is a big span of time. Some used a cast, while others used a removable orthosis. Some used it full-time and then gradually reduced it. In the end, all of the outcomes were similar. It just shows the variation and preferences for one type of surgery. The majority of studies had the immobilization period from a four to a six-week range which is what I use and see. Range of motion would start anywhere from two to six weeks post-op, which is again what I usually see. Strengthening is anywhere from two to eight weeks. I usually see it start later in that four to the eight-week range. This has to do with surgeon preference and how the patient is progressing.

- Three Post-Op Phases

- Acute Post-Op

- 0-6 weeks

- Unloaded

- 1-12 weeks

- Functional

- 3 weeks- 6 months

- Acute Post-Op

In this study, they found three postop phases. The first being the acute post-op phase for about the first six weeks. The second phase is what is called the unloaded phase where we are not putting stress on the CMC joint yet, but we are starting movement. That could be anywhere from one to 12 weeks. The last phase is the functional phase anywhere from three weeks to six months.

Overview of Treatment Phases

Here are the phases I and many doctors I work with use. Again, this is going to depend on your surgeon's preference, hand therapist experience, and how the patient is progressing. I like to use four phases rather than three.

Phase 1- Immobilize & Protect (0-4)

- Orthosis

- FA-based thumb spica (cast or orthosis)

- AROM

- Uninvolved joints: Shoulder, elbow, digits, thumb (interphalangeal joint) IPJ

- Other considerations

- Edema control

- Avoid resistive grip/pinch on the surgical side

The first zero to four weeks is an immobilization and protection phase. The first thing you need to do after surgery and post-op is to immobilize the joint, either with a cast or an orthosis. An example is shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9. Forearm-based orthosis immobilizing the wrist and thumb.

Most surgeons I work with will send the client after their first post-op visit (after 10 to 14 days of being in the post-op dressings) to therapy for fabrication of a forearm-based thumb spica. This will keep the wrist in slight extension. The thumb will be midway in between extension and abduction, and the IP joint can stay free.

In terms of range of motion, you want to focus on uninvolved joints. The IP joint of the thumb should definitely start moving in full (or an almost full) range of motion. The same should be done for the other four digits. All IP and MP motion should be able to be maintained. We also need to look at elbow and shoulder movement due to a tendency for a client to keep their arm flexed and internally rotated after surgery. It is important to help our clients stretch these uninvolved joints. Some surgeons are going to begin gentle range of motion in this phase, while others will immobilize totally for the first four weeks. I have seen patients who have been in a cast for up to four weeks either due to compliance issues or their preference. Some may come out of the cast early and go into a removable orthoplast splint.

Another thing you want to consider is how this patient is doing with edema. We also want to educate them to avoid resistive grip or pinch on the surgical side for probably the first four weeks or so.

Phase II- Controlled ROM (4-6)

- Orthosis

- At all times except for ROM HEP

- Fabricate FA-based thumb spica (if not already done)

- AROM

- Wrist

- Thumb MP/IP focus

- Avoid excessive CMC flexion, adduction, opposition

- Decrease dorsal capsule strain

- Other considerations

- Scar management

- Desensitization program (if DRSN irritated or incision hypersensitive)

- Avoid resistive pinch/grip, CMC loading, weight-bearing

The second phase here is what I call the controlled range of motion phase. We are beginning range of motion but in a controlled manner as there are certain things we still do not want to stress. At this point, the orthosis can come off for the home exercise program to start mobilizing the thumb and the wrist. There should be a removable orthosis at this phase. Examples are shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10. Examples of hand-based orthoses.

Also, a lot of physicians at this time are going to cut off the forearm-based cast and move to a hand-based orthosis so the wrist can start moving.

You want to start initiating range of motion of the wrist at this point as well as thumb MP and IP flexion. Again, it needs to be controlled range of motion so that you are avoiding things that will stress out that dorsal capsule or the new repair. This would include CMC flexion, adduction, opposition, or any kind of pulling motion. These are all of the movements across the palm.

It is also important to work on the scar. The scar at around four weeks should have about 50% of normal of its tensile strength. By six to eight weeks, it is around 80%. You absolutely want to work on mobilizing and managing that scar tissue, whether it is through massage, silicone sheets, or whatever technique you would want to use.

If there is irritation of the scar or nerve, you want to do some desensitization. You want to avoid any resistive pinch, grip, CMC loading, or any weight-bearing through the hand. Excessive CMC strain is going to cause the thumb to pull out of alignment. You can also start light prehension to the index and middle finger during this phase but not pulling all the way over to the fourth and fifth digits. I would avoid that opposition motion during this phase.

Phase III- CMC Mobilization (6-8)

- Orthosis

- Wean splint for light activity; Wear at night

- AROM

- Continue to maximize ROM from earlier phases

- Begin to mobilize CMC joint: Full flexion, ABDuction, opposition, ADDuction

- Pain should guide progression

- Other considerations

- Scar management

- Desensitization program (if DRSN irritated or incision hypersensitive)

- Encourage light functional activity, functional prehension

This phase, around six to eight weeks, is when you can start mobilizing everything. Additionally, the orthosis is going to start getting weaned completely or may be worn for heavier activities or at night for a few weeks. Some surgeons I work with really like this neoprene splint, as shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11. Neoprene thumb splint.

This puts the thumb in good alignment and feels good after surgery. It creates some warmth in there, which again is comforting. I have one surgeon who likes to put clients in this pretty early (a few weeks post-op). Some will phase you into this later, but it is a wearer-friendly option.

Range of motion should be looking really good now at both the IP and MP joints. If that patient can perform opposition all the way to that fifth digit without pain, then you can really start pushing into full flexion across the palm, which is going to put some strain on the CMC joint. Some physicians might also start gentle strengthening at this point. Pain is going to guide progression and also surgeon preference. Full motion has to come first.

You still need to manage the scar and check on that looking for any irritation that might occur at the scar area over the thumb. Finally, you want to encourage light hand use within functional activities.

Phase IV- Function & Strength (8-12)

- Orthosis

- Discontinue splint once full ROM achieved and pain managed, can still wear at night, alter to short CMC orthosis for ‘heavier’ activity or neoprene CMC orthosis

- AROM and Strength

- Work towards full thumb AROM

- Begin light thumb/grip/pinch strength and progress

- Guided by ROM progress and pain

- Start isometric and progress to isotonic

- Other considerations

- Strength will continue to improve after d/c from formal therapy

- Consider work conditioning programming if appropriate

The last phase is going to be the function and strength phase. The orthosis is probably discontinued at this point unless that person uses their hand for heavier work. It would be a hand-based CMC orthosis or a neoprene one that I just showed you. It is usually discontinued completely after 12 weeks when it is stable and there is little to no pain.

In terms of range of motion, I always say there is a window of time in which to get your range of motion back, but regaining strength can happen at any time. The focus needs to be on getting range of motion back first. The IP motion needs to be at a full range of motion. If not, start working on passive motion with some stretching and pushing. You can begin light pinch and grip strengthening and then progress that. You might want to start with some isometric strengthening before isotonic, just because it is safer all around and less strain on those muscles. How do you know what full range of motion is? I have a pretty good IP thumb range of motion, but I have an awful MP range of motion. I always like to look at the contralateral side. When you look at my contralateral side, my other side is pretty bad as well so that is my baseline. Make sure you are looking at one side versus the other to see what your patient and your client's normal is.

Other things you want to consider at this point as you are getting ready to discharge is to make sure that your patient knows that formal therapy or that improvements are going to continue after formal therapy. The window again for strengthening is large and they can continue to get stronger one to two years afterward. They are not going to hit their max improvement 12 weeks after surgery. You may need to tell patients to pump the brakes on their expectations in the initial months after surgery. They are not going to be better and back to normal, but they are going to be really functional.

At this point, I would also recommend a work conditioning program if the person uses their hands for heavier activities. For instance, I have done work conditioning programming where my clients have been plumbers, CNAs, et cetera. This gives an extra boost to prepare them for work after this surgery.

Study Example (Ataker et al., 2012)

Methods

- 23 patients (21 women & 2 men)

- Average age 63.5 (30 yo – 83 yo)

- 4 cases were bilateral

- 13 dominant hand/14 nondominant

- Symptoms included joint crepitus, + grind test, deformity, limited ROM, trapezial height (x-ray)

- DASH scores, VAS, strength, ROM, trapezial height

- Eaton-Littler classification of III or IV

- Evaluation pre-op, 12-week post-op, final follow up

(Ataker et al., 2012)

Here is a study that was done with 23 patients who underwent the LRTI procedure. It was 21 women and two men which follows what I said earlier about gender differences. This is going to impact women more than men. The age range also shows that people in their mid-60s are the ones typically opting for this surgery. Four of these cases were bilateral, and it was a mix of dominant and non-dominant hands. Some patients also had a second surgery at the same time, whether it was carpal tunnel release, trigger finger, or de Quervain's tenosynovitis release. Their symptoms preop included crepitus, a positive grind test, visual deformity, limited range of motion, and then on x-ray, a shorter trapezial height.

They measured outcomes using the DASH, which is a very commonly used outcome measure in hand therapy, and the Visual Analog Scale for pain. They looked at strength, range of motion, and trapezial height again on x-ray. All of these patients were an Eaton-Littler Classification of a three or a four. They were evaluated at pre-op, 12-weeks post-op, and then a final follow-up, which had a lot of variation.

This protocol included two weeks in a thumb spica cast, and then after two weeks, a hand-based custom orthosis for two weeks of immobilization to protect the ligament reconstruction. Once they were in the hand-based orthosis, they could then start moving their wrist. They determined that while some studies recommend four to six weeks of full immobilization of the wrist and thumb, they rationalized that inflammation was going to decrease at about two weeks, and no need to immobilize the wrist for longer than that. The thumb had the repair, not the wrist.

Results

- Average follow up at 31.5 months post-op (range of 12-57 months)

- Average number of therapy sessions 16.8 (range of 10-20 sessions)

- Pre to post-op grip strength had 50% improvement

- Lateral pinch improved 25% at post-op and 29% by the final visit

- Increase in palmar ABD by 30% at the final visit

- Increase in radial ABD by 33% at the final visit

- VAS and DASH improvements = Patient satisfaction

The average follow-up was 31.5 months post-op. They did an average of 16.8 therapy sessions post-op. They found that their pre to post-op grip strength, lateral pinch strength, and palmer and radial abduction range of motion were all improved by the final visit. They also determined that based on the Visual Analog Scale that their pain levels were less. Their DASH score was also less, which means they improved in function and patient satisfaction. They also looked at x-ray evidence and they noticed a gradual decrease in the space between the scaphoid and the metacarpal in the area where the trapezium was excised. However, this did not contribute to any instability, weakness, or patient dissatisfaction. They determined this was a win.

The study's purpose was to describe the surgery and rehab protocol. Again, there were no specific guidelines. They did say that optimal results depended on good surgical technique. This is very well-documented in the literature. However, the appropriate post-op rehab protocol is not. There is a lot of variation which is why it is so important for occupational therapy practitioners to know what they are doing after the surgery and how to guide clients through the post-op time.

Long-Term Follow-Up Example (Dilek et al., 2016)

Methods

10 patients underwent LRTI and 10 patients were the control group (average age 66.5)

- Measures:

- VAS, DASH, thumb TAROM and ABDuction, grip, pinch strength, and patient satisfaction (0-10 scale)

- Followed up on average 49 months post-op (+/- 26 months)

Here is another study that looked at long-term follow-up. It looked at 10 patients who underwent LRTI and 10 patients in the control group. Again, the median age is in the mid-60s range. They used a lot of the same outcome measures like the Visual Analog Scale, the DASH, thumb total active range of motion, and then specifically thumb abduction, grip, and pinch strength. They used a zero to 10 scale for patient satisfaction. They followed up again a few years post-op with those who had the surgery and those who opted not to have surgery. This surgery used a slip of the APL tendon, not the FCR tendon. They mobilized clients in a thumb spica for three weeks and started active and active assist range of motion closer to the six-week mark.

Results

- Significant Improvement

- Patient Satisfaction

- Function

- Pain

- Range of Motion

- No Significant Improvement

- Grip Strength

- Pinch Strength

There were significant improvements in patient satisfaction, hand function, which they probably used the DASH to determine, their pain levels on the Visual Analog Scale, and their overall range of motion. There was no significant improvement between the control and the LRTI group for grip and pinch strength.

Early Active Protocols

- Partial vs. Complete Immobilization

- Positive outcomes with partial immobilization/early protected motion but few comparative studies

- Positive outcomes for pain, ADL participation, grip/pinch strength but few comparative studies

- Emphasize CMC motion in extension and ABDuction first and avoid flexion and ADDuction early as well as MCP hyperextension *

- OVERALL no worse outcomes or additional complications and may be a faster recovery – return to function

(Wouters et al., 2018)

The literature also suggests that early active protocols are becoming more common, and I am seeing this in doctors' orders as well. They are seeing positive outcomes with a partial immobilization versus a full, complete immobilization, and then doing some early protected motion. However, there are very few comparative studies because this is a newer type of technique or a newer trend in the post-op protocol. Our surgeons are starting around the two-week mark for some early active protected motion. With early active protocols, there are positive outcomes for pain. People are getting back to participating in ADLs using their hands a little bit sooner, and grip and pinch strength are positive as well.

With early active protocols, it is still is imperative to avoid certain motions while focusing on others. For example, you can emphasize CMC motion in extension and abduction first while avoiding flexion, adduction, and MCB hyperextension. This is because we do not want them to start developing a Z deformity or pulling everything out of alignment.

Overall, there were no worse outcomes or additional complications with an early active protocol than immobilizing for the full four to six weeks. And, there might be a faster recovery and return to function. Think about the application of that. Returning to function for the aging population is becoming really important. If these individuals are opting for this surgery in their 60s, and we are seeing individuals working longer, they may undergo this surgery and need to get back to meaningful occupations, including work. Early active protocols may help push this along a little bit and with good outcomes and faster recovery.

New Techniques

- Suture Suspension

- Shorter op time

- No K-wires/pins

- No drill holes

- No tendon harvest

- LRTI

- Longer op time

- Tendon transfer/2nd incision site

- Drill through MC

- Possible pin infection

- Both techniques remove the trapezium

- No long-term studies on suspension – little data from follow up

(Weiss et al., 2019)

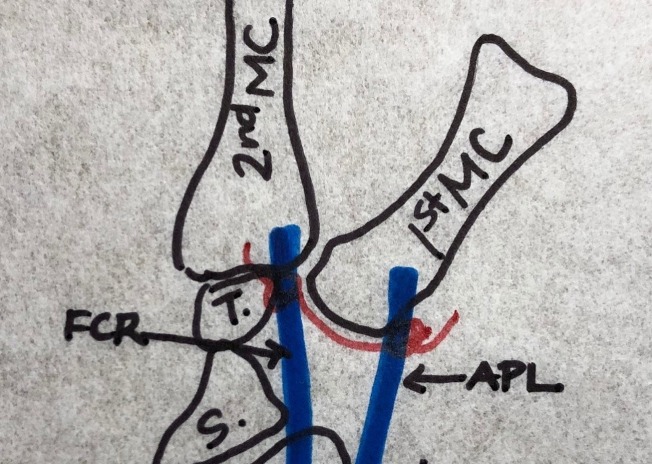

Here is a newer technique that was outlined in 2019 in a study by Weiss and colleagues. It describes what is called a suture suspension where there is a partial or complete removal of the trapezium, but instead of taking a tendon and using a slip of that to stabilize and cushion that joint, they use a braided, non-absorbable suture. In this artist's rendition in Figure 12, the red is the suture. This is going to attach to the adjacent tendons.

Figure 12. Red suture line representing the non-absorbably suture supporting the FCR and APL tendons.

You can see it creates a sling or a hammock for the FCR and APL tendons and also maintains the metacarpal height. It keeps the metacarpal from migrating down as well.

This technique has some benefits. It does not require a second incision to harvest a tendon. It does not have a K wire inserted to provide stability. Both of these things can lead to issues with scar tenderness, wound hematomas, neuromas, complex regional pain syndrome, or tendon adhesion. Additionally, the LRTI procedure has a longer operative and post-op recovery. Then, if you are using a pin for stabilization, there is a risk of infection, migration, and loosening of that pin. Pins can also be a bear to deal with post-op.

The suture suspension can be viewed as a more efficient and less invasive type of surgery that still stabilizes the thumb and manages the first metacarpal. There is no need to drill a hole in the metacarpal, use a K wire, or use any other kind of anchor. However, there are no long-term studies on this suspension yet. There is very little data up at this point.

Some of our surgeons are using the suture suspension now, and what we are finding is that the post-op protocol is still pretty similar. While there are benefits to the suture suspension versus the full-blown LRTI, the post-op protocol isgoing to be pretty similar to how you guide your patient through therapy. Again, it is good to know what your surgeon prefers and what they are doing in the OR so you know how to manage it in the post-op world.

Summary

- Surgical option for CMC OA with positive outcomes if conservative management fails

- Be knowledgeable about the post-op protocol

- Specifics may be surgeon specific

- Know post-op outcomes

- Return to function, ROM, stability

- Return to maximum grip and pinch strength longer-term

- OTPs can help clients understand expectations of thumb arthroplasty

To summarize, we know clients are undergoing different surgeries. There are surgical options to fix if conservative management fails. The most common surgery is the LRTI, but there is still variation in what happens during that surgery, how it is managed, what tendon is used, and how much of the trapezium is excised.

OT practitioners need to be able to explain all of that. What happened, what went on in the thumb, and what is going to happen post-op? You need to work closely with your surgeons so you know what their preferences are. Then, you know how to create expectations in your clients for what the outcomes are going to be.

The goal is to return them to function. The idea is full range of motion as soon as possible. We also need to keep the joint stable post-op and keep the thumb stable for the long term. This may require education on joint conservation and protection. Clients can return to max grip strength and pinch strength, but it might take longer than your patient is anticipating. It is typically one to two years to get maximum grip and pinch strength. We are around to help our clients understand these expectations and be knowledgeable to guide them through this post-op protocol for thumb arthroplasty.

Questions and Answers

Is there a rise in this type of surgery due to cell phone and technology use, things like texting and using our thumbs a lot?

I agree. I was even going to bring up and joke about when we talk about what do we use our hands for? I have three boys who like video games. It is a digital world that we live in. More and more studies are starting to come out about this. I have seen a lot more talk about tendons and overuse injuries. This is going to pull thumbs out of alignment causing the joints to wear out faster. I do think that is going to be a trend which is why it is even more important for us to educate on conservative management and joint protection. All of the biomechanical things available in the world are not going to help people with poor hand posture and alignment. Thus, we really need to go the route of ergonomics and joint conservation.

How would worker's comp docs prove an injury such as this mixed with carpal tunnel syndrome is a result of technology versus work?

I do not know that there is a way you can do that, especially with repetitive stress injuries and arthritis. There is no crystal ball to show what happened. There is going to be some subjectivity in there. However, if you have the evidence to back up and say when symptoms occurred and can describe them along with good documentation from the evaluation, you may be able to make that connection.

Are there any surgeons implanting plastic or metal hardware to replace the removed bone?

The ones that I work with do not. That seems to be more of an antiquated type of procedure with more complications than the LRTI has.

I see a lot of post-op patients who have poor radial abduction. Why do you think that is?

It is almost like the brain does not know how to make that movement. We often do not work functionally with a thumb coming out in radial abduction. The thumb typically comes into palmer abduction or flexion across the palm. This makes the thumb adductor muscle get very strong and overpower the muscles that do abduction.

When is the ideal time to start scar massage?

I like to start as soon as the Steri-Strips come off. I do not aggressively get in there, but I am going to start man