Editor’s note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Psychosocial Approaches For Pediatric TBI: Addressing The Impact On Children And Maternal Well-Being, presented by Sabina Khan, PhD, OTD, MS, OTR/L.

*Please also use the handout with this text course to supplement the material.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to identify the emotional, social, and cognitive challenges commonly faced by children with pediatric traumatic brain injury (TBI).

- After this course, participants will be able to recognize the impact of pediatric TBI on maternal well-being, including the emotional and mental health challenges experienced by mothers.

- After this course, participants will be able to differentiate between occupational therapy interventions that address psychosocial needs in children with pediatric TBI and their mothers, focusing on emotional regulation, social participation, and maternal mental health.

Introduction

Today, I will be discussing an often overlooked aspect of pediatric traumatic brain injury: the psychosocial impact on children and their families, with a particular emphasis on maternal well-being.

To share a bit about myself, I have been practicing as a licensed occupational therapist for approximately 13 years. Throughout my career, I have gained experience in a wide range of settings, including acute care, long-term acute care hospitals, inpatient rehabilitation, traumatic brain injury units, telehealth, school-based occupational therapy, and home health.

Lasting Psychosocial Impact of a Pediatric TBI Case

I want to begin by sharing a story that powerfully illustrates the lasting impact of pediatric traumatic brain injury—not just on the child, but on the entire family. A few years ago, I worked with a mother whose son had sustained a traumatic brain injury at the age of five. At the time, he received standard rehabilitation services, including occupational and physical therapy, and appeared to recover strongly. He regained his physical abilities, improved his speech, and could return to school.

However, four years later, when I met them, his mother had started noticing new challenges she hadn’t anticipated. Her son was struggling socially. He had difficulty making and keeping friends, became overwhelmed in group settings, and frequently had emotional outbursts when faced with changes. Although he was keeping up academically, issues with executive functioning—such as organizing his work and following multi-step instructions—were becoming increasingly apparent. His mother was exhausted, frustrated, and overwhelmed. She confided in me, saying, “I thought we had gotten past this. Why is he struggling now when he seemed fine before?”

This scenario is a common one in pediatric traumatic brain injury. Because a child’s brain is still developing, many psychosocial effects don’t emerge until later, when the social and cognitive demands increase. The injury may remain unchanged, but the environment and expectations surrounding the child evolve, often revealing challenges that were not previously evident.

As occupational therapy practitioners (OTPs), our role must extend beyond working solely with the child. In this context, we also need to support the caregiver—in this case, the mother—by helping her understand that what she is seeing is not regression, but rather a delayed manifestation of executive function difficulties stemming from her child’s earlier brain injury. Our approach, therefore, needs to be twofold: providing interventions for the child that focus on social and emotional skills, executive function training, and self-regulation strategies to help him navigate school and peer relationships, while also offering parent education and coaching. This allows caregivers to adjust their expectations, implement structure at home, and manage their stress levels more effectively.

This example underscores a critical point: rehabilitation does not end when therapy sessions conclude. Families require ongoing support. By integrating a more family-centered psychosocial approach into our interventions, we not only improve outcomes for children with traumatic brain injuries but also empower their caregivers to support long-term recovery. In doing so, we promote the well-being of the entire family system.

Pediatric TBI

Definitions

Before we define key terms, I’d like to begin by addressing an important question: What age group is considered pediatric in the context of traumatic brain injury? The answer to this is not universally agreed upon, as experts vary in their definitions. Some define the pediatric population as individuals up to 18, while others extend adolescence into the mid-twenties, acknowledging that brain development continues well into early adulthood. In fact, neuroimaging research using MRI and CT scans has shown that critical areas of the brain—particularly those involved in executive function and emotional regulation—continue to develop beyond childhood.

For this presentation, however, we will be focusing on pediatric traumatic brain injury in individuals up to the age of 18, with a more specific emphasis on children between the ages of four and ten. This particular age range is significant because during these years, social-emotional development, executive functioning, and peer interactions become increasingly complex. Psychosocial interventions are especially relevant at this stage, as children navigate these emerging developmental demands.

While traumatic brain injury can certainly affect infants and toddlers, the availability of published occupational therapy research on psychosocial interventions for children under the age of four is limited. Most studies focus on preschool and school-aged children, as this group faces more pronounced and observable social and academic challenges following a brain injury.

As we move forward, we’ll explore how occupational therapy practitioners can address the psychosocial impact of traumatic brain injury within this specific population. We will focus on rehabilitation strategies that support school reintegration, peer relationships, and family adaptation.

Now that we’ve established the scope of pediatric traumatic brain injury for this presentation, let’s take a moment to define what we mean by traumatic brain injury and how it is categorized. Unlike conditions that are congenital or degenerative, TBI is an acquired brain injury resulting from an external force. It is classified based on severity—mild, moderate, or severe—using key clinical indicators such as loss of consciousness, duration of post-traumatic amnesia, and neuroimaging findings.

TBI Severity | Definition & Characteristics |

Concussion (Mild TBI) | A subset of mild TBI. Typically involves transient symptoms such as confusion, dizziness, headaches, and possible loss of consciousness for less than 30 minutes. No structural brain damage is visible on standard imaging. |

Mild TBI | Loss of consciousness for less than 30 minutes or post-traumatic amnesia (PTA) for less than 24 hours. Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 13-15. Symptoms may include headache, dizziness, fatigue, and difficulty concentrating. |

Moderate TBI | Loss of consciousness for 30 minutes to 24 hours, PTA for 24 hours to 7 days, or a GCS score of 9-12. More significant impairments in cognition, memory, and behavior. Imaging may show structural damage. |

Severe TBI | Loss of consciousness for more than 24 hours, PTA for more than 7 days, or a GCS score of ≤8. Long-term cognitive, motor, and behavioral impairments are common. Requires intensive medical and rehabilitative care. |

One of the most common forms of mild traumatic brain injury is a concussion. However, it’s important to clarify that not all mild TBIs are concussions. While a concussion is always categorized as a mild TBI, other types of mild TBIs result from non-penetrating head injuries and can still cause temporary disruptions in brain function. In pediatric populations, TBIs tend to be milder than those seen in adults, often because young children are more likely to sustain injuries from falls or sports-related incidents.

Despite this, research indicates that mild TBIs in children are frequently overlooked, particularly in comparison to adults. One reason is that symptoms in children may not be immediately evident. Cognitive or behavioral challenges might surface much later, often as the child enters school and encounters increased academic and social demands. This delayed emergence of symptoms underscores the importance of careful, ongoing monitoring.

Another critical factor to consider is the nature of the developing brain. Unlike adults, children’s brains are still maturing, which means that the full impact of a mild TBI may not be immediately visible. A child, such as the one I mentioned earlier, who sustained a mild TBI at age five, may appear to recover well in the short term. However, as that child grows older and is expected to perform more complex cognitive tasks and manage increasingly nuanced social situations, deficits in executive functioning, emotional regulation, and social interaction may become more apparent.

Understanding these classifications and the unique developmental considerations of pediatric brain injury is essential for tailoring effective interventions. This is especially true when addressing psychosocial outcomes that may not emerge until years after the initial injury. As OTPs, we must remain attuned to these long-term implications and adjust our approaches to support the child’s ongoing development and well-being.

Prevalence

When we examine the prevalence of pediatric traumatic brain injury, the numbers are undeniably significant. Hundreds of thousands of cases are reported each year, which gives us a sense of the scale, but these figures only tell part of the story. They do not capture who these children are or how their lives and their families are impacted in the long term. What often goes unaddressed is what happens after that initial emergency room visit. How many of these children go on to receive long-term rehabilitation? How many are monitored for ongoing cognitive and emotional changes? The reality is that many children—especially those diagnosed with mild TBI—are discharged with little to no follow-up, even though their symptoms may worsen or evolve over time.

A critical factor that compounds this issue is disparities in access to care. Children from low-income families or rural communities often lack access to specialized neurorehabilitation services, placing them at a heightened risk for long-term disability. Additionally, research has shown that children of color and those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds are less likely to receive appropriate follow-up care after a TBI. This creates an inequity in recovery outcomes and further entrenches disparities in health and educational achievement.

As OTPs, we must look beyond the statistics and ask more profound, meaningful questions: Who is receiving access to care, and who is being left behind? How can we advocate for better screening practices and consistent long-term monitoring? What role can we play in educating families, schools, and communities about the potential long-term consequences of TBI?

While prevalence data helps us understand the magnitude of the issue, our clinical and advocacy roles help transform those numbers into meaningful action. Our work must focus on improving recovery trajectories, establishing stronger support systems, and ensuring more equitable access to care. By doing so, we enhance outcomes for individual children and contribute to building a more inclusive and responsive system of care.

Impact

When we talk about the impact of pediatric traumatic brain injury, it's essential to recognize that not all brain injuries are the same. The effects can vary greatly depending on the severity, whether the injury is mild, moderate, or severe. A common misconception is that a mild TBI, such as a concussion, is a short-term condition that children quickly recover from. In reality, mild TBIs can result in lasting cognitive and emotional effects, particularly when they go undiagnosed or untreated. Unlike moderate or severe TBIs, where impairments are often more obvious and prompt early intervention, the symptoms associated with a mild TBI can be subtle, delayed, and easily overlooked or dismissed.

One of the biggest challenges with pediatric mild TBI is its impact on developmental milestones. Initially, a child may not show significant delays—skills like walking, talking, and playing may appear completely intact. However, difficulties begin to emerge as the child matures and is expected to meet more complex developmental demands, such as sustaining attention, coordinating fine motor tasks, or regulating emotions. For instance, a child may struggle with handwriting, organizing their belongings, dressing independently, or managing classroom routines. These struggles often become more apparent during the school years, when cognitive and executive function demands intensify.

In contrast, moderate and severe TBIs tend to result in more immediate and recognizable impairments. Delays in speech and language, gross and fine motor skills, and self-care tasks such as feeding and dressing are often evident early on. These children typically require intensive rehabilitation from the outset. Cognitive deficits such as impaired memory, reduced attention span, and difficulty with executive functions are commonly observed and addressed as part of the recovery process.

Even in cases of mild TBI, cognitive impairments can surface over time. A child functioning well may suddenly become more forgetful, struggle with multitasking, or appear overwhelmed in classroom settings. In moderate or severe TBI cases, these challenges are more immediate and severe, often including difficulty with basic problem-solving, speech articulation, and motor planning. The key difference lies in the timing of when these deficits become apparent. In mild cases, they may not surface until months or even years later, whereas in moderate and severe cases, they tend to be evident soon after the injury.

Emotional challenges such as mood swings, anxiety, and depression can also occur after a mild TBI. Research shows that children with mild traumatic brain injury are at a higher risk of developing mental health disorders over time. This may be due to the lack of immediate intervention and the absence of formal supports. As these children try to keep up with their peers, they may struggle with self-regulation and emotional control, often leading to frustration and low self-esteem. By contrast, children with moderate or severe injuries are more likely to receive emotional and psychological support as part of their care plan, which can help mitigate some of these outcomes.

Social difficulties represent another commonly underestimated consequence of mild TBI. A child who previously had no issues making friends may begin to struggle with social cues, impulse control, or emotional regulation, leading to peer rejection. These changes often occur gradually, making it difficult for parents and teachers to connect them to the earlier brain injury. As a result, the child may be misunderstood or mislabeled, further compounding the social and emotional impact.

Family stress and caregiving demands are significant across all levels of TBI severity, but they manifest differently. In mild cases, parents often experience a sense of uncertainty, questioning whether the changes they observe in their child are developmental variations, behavioral concerns, or lingering effects of the injury. Interestingly, research suggests that parents of children with mild TBI frequently report higher levels of distress than those whose children have experienced severe TBI. This may be because they receive less validation or formal support, despite the persistence of their child’s challenges.

Ultimately, the nuanced and often delayed presentation of symptoms in mild pediatric TBI requires us, as occupational therapy practitioners, to maintain a vigilant, family-centered, and long-term perspective. Recognizing these distinctions across severity levels enables us to better support children and families through the complex and evolving recovery journey.

Common Causes

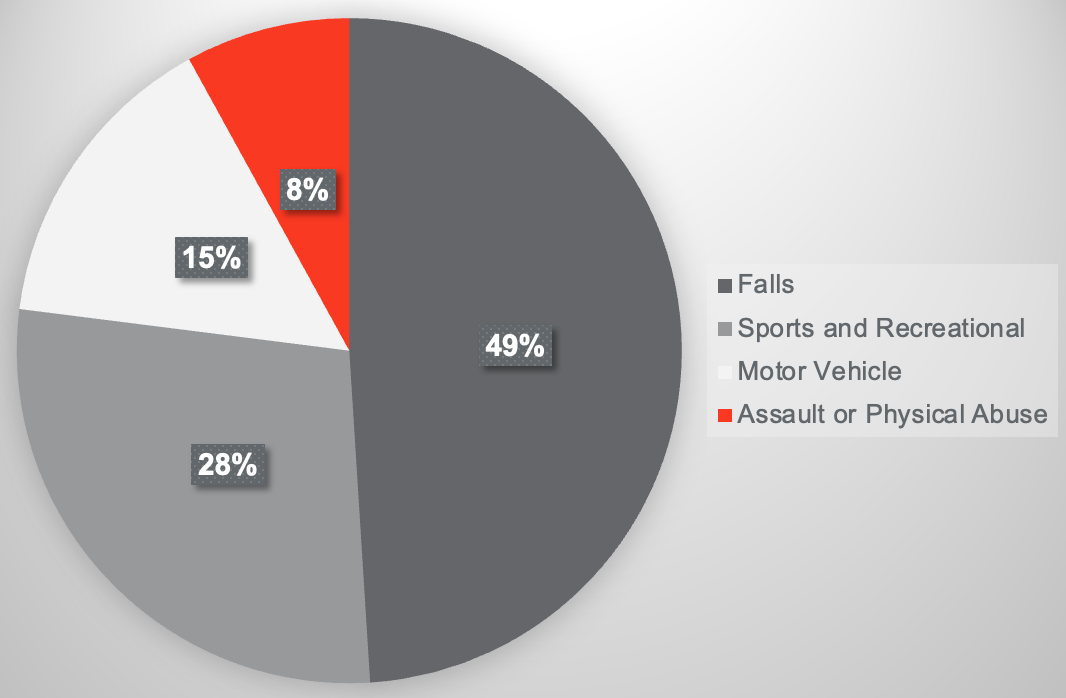

The data show some clear patterns when we examine the leading causes of pediatric TBI (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Chart showing common causes of pediatric TBI.

Falls account for approximately 49% of pediatric traumatic brain injuries, making them the most common cause, particularly among children under the age of ten. This prevalence aligns with what we understand about early childhood development. Young children are still refining their balance, coordination, and safety awareness, which increases their risk for injury. Many of these falls occur in the home environment—falling off furniture, down stairs, or from playground equipment. What’s especially concerning is that these incidents are often dismissed as just “a bump on the head,” leading to underreporting and missed early intervention and monitoring opportunities.

As children grow older and become more active and independent, sports and recreational activities emerge as another leading cause of TBI. Sports-related TBIs are increasingly common, especially in contact sports. However, many children do not report symptoms because they don’t recognize them, or due to the pervasive “shake it off” mentality that encourages staying in the game. This cultural norm increases the risk of second impact syndrome, a serious condition that occurs when a second concussion is sustained before the brain has fully recovered from the first. Girls, in particular, are at higher risk for concussions in sports such as soccer and cheerleading, which may be due to differences in neck strength and head stabilization compared to boys.

Motor vehicle accidents are another major cause of pediatric TBI, and they often result in the most severe injuries. These incidents typically affect older children and involve passengers, pedestrians, or cyclists. The force of impact in a car accident significantly increases the risk of moderate to severe TBI. A significant risk factor, particularly for infants and toddlers, is improper car seat use. Research indicates that many head injuries could be prevented if car seats were correctly installed and used. Ensuring proper restraint systems is a critical, yet often overlooked, step in prevention.

While we often associate pediatric TBI with accidental causes like falls and sports injuries, one of the most disturbing realities is that a significant percentage of cases stem from intentional harm. Assault and physical abuse account for about 8% of pediatric TBIs, though the actual number is likely higher due to underreporting and misdiagnosis. Infants and toddlers are particularly vulnerable, relying entirely on their caregivers for protection, with no ability to report harm or escape unsafe environments.

One of the most severe and preventable forms of intentional TBI is shaken baby syndrome. This condition typically results from a frustrated caregiver violently shaking a baby, causing the brain to move back and forth within the skull. This leads to bleeding, swelling, and irreversible brain damage. Because there are often no external signs such as bruising, many cases go undetected until it is too late. Survivors may experience lifelong consequences, including seizures, profound cognitive impairments, and severe physical disabilities. Blunt force trauma is another form of inflicted injury that may lead to traumatic brain damage.

As occupational therapy practitioners, as well as educators and healthcare providers, we must remain vigilant for the signs of abuse and neglect. Multiple or repeated TBIs from ongoing abuse can result in severe developmental delays, behavioral disorders, and increased susceptibility to mental health challenges later in life. Perhaps the most heartbreaking statistic is that homicide is the leading cause of TBI-related death in children aged four and younger. These tragic outcomes often occur in homes burdened by neglect, domestic violence, or overwhelming stress situations exacerbated by a lack of resources, education, or mental health support.

While we may not always be in a position to diagnose abuse, OTPs are often uniquely placed to observe subtle red flags that others may miss. Delays in motor skills, atypical postures, or difficulties with sensory processing can indicate past injuries. Behavioral indicators such as fear of specific caregivers, exaggerated startle responses, or unexplained emotional outbursts may also point to trauma. Supporting at-risk families by providing education on child development, stress management, and positive parenting strategies can play a meaningful role in prevention and long-term support. Recognizing these risks and responding with appropriate intervention and advocacy is a vital component of our role in pediatric care.

Pediatric TBI vs. Adult TBI

When discussing pediatric traumatic brain injury, one of the most critical distinctions from adult TBI lies in the nature of the developing brain. Unlike adults, whose brains have reached full structural and functional maturity, a child’s brain is still undergoing essential developmental changes. This makes the pediatric brain both more vulnerable to injury and, at the same time, more adaptable in terms of recovery. As mentioned earlier, the brain does not fully develop until the mid to late twenties. This means that an injury sustained at an early age can disrupt key neurological pathways before they have had a chance to form fully.

The concept of neuroplasticity plays a central role here. Children’s brains possess a remarkable capacity to rewire and adapt following injury. However, neuroplasticity can be a double-edged sword. While it can facilitate recovery, it also presents the risk of children “growing into” their deficits, where difficulties only emerge later in life, as cognitive and social demands increase. This is often seen during middle or high school, when higher-level executive functions such as planning, organization, emotional regulation, and impulse control become more crucial to daily functioning.

Anatomical differences between children and adults increase the risk associated with pediatric TBI. A child’s skull is thinner and offers less protection. At the same time, their brain is less myelinated, meaning that the neural pathways are not yet fully insulated and therefore more susceptible to injury. Additionally, the higher water content in a child’s brain increases the likelihood of swelling and secondary injury following a traumatic event. These structural and biochemical differences mean that even a seemingly minor blow to the head can lead to significant consequences for a child. In contrast, an adult might sustain only minimal effects from the same type of impact.

The effects of pediatric TBI go beyond cognitive impairments—they impact a child’s ability to develop, learn, and relate to the world. The brain governs developmental milestones such as language acquisition, motor coordination, and social cognition. The age at which an injury occurs plays a major role in determining the functional impact. For instance, a brain injury before age three may interfere with foundational speech and motor development. If the injury occurs in early childhood, it may manifest as delays in literacy, handwriting, and social engagement. On the other hand, an injury sustained during adolescence often results in increased emotional dysregulation and impulsive, risk-taking behaviors due to the vulnerability of the prefrontal cortex during this period.

One of the challenges in pediatric TBI is that delays and deficits are not always immediately apparent. Many children recover well in the short term, thanks to the brain’s plasticity. However, hidden deficits begin to surface as they are later called upon to meet more complex academic, social, and emotional demands. This can lead to confusion and frustration for the child, their caregivers, and educators, especially when these difficulties are not linked to the initial injury.

While children may show quicker initial recovery compared to adults, this does not necessarily mean they have been spared the effects of the injury. Adults typically experience a more immediate and predictable course of recovery. In contrast, the impact of a brain injury in children tends to unfold slowly over time and often requires long-term support to address the evolving nature of their challenges.

Persistent behavioral difficulties are also common following pediatric TBI. Attention deficits frequently arise, directly correlating with academic struggles. Problems with problem-solving and poor social interactions may become apparent as children have trouble forming and maintaining peer relationships. These challenges can be particularly isolating and distressing, especially when they emerge gradually and are misunderstood or overlooked by those around them.

As occupational therapy practitioners, we must understand pediatric TBI's unique developmental and neurological landscape. Our interventions must be responsive not just to the immediate needs of the child but also to the long-term trajectory of their development, supporting them and their families through the full continuum of recovery.

Pediatric TBI: Boys vs. Girls

Sex differences play a significant role in both the risk for pediatric traumatic brain injury and how the injury manifests and is experienced. Research consistently demonstrates that boys and girls differ regarding TBI incidence, severity, and recovery patterns.

School-age boys are nearly twice as likely to sustain a TBI compared to girls. This disparity is primarily attributed to higher levels of risk-taking behavior, increased participation in physical and contact sports, and elevated rates of impulsivity—all of which contribute to a greater likelihood of head injury. Moreover, boys not only experience TBIs more frequently, but they also tend to sustain more severe injuries. Statistics show that the mortality rate for TBI in males is approximately four times higher than that for females, emphasizing the severity of their injury profiles.

Girls, on the other hand, are more likely to sustain TBIs from falls or as passengers in motor vehicle accidents. This increased vulnerability is due, in part, to anatomical differences such as reduced neck strength and less head stabilization, which can amplify the forces associated with concussive injury. While boys are overrepresented in high-impact sports such as football, hockey, and extreme sports, girls are more commonly injured in sports like gymnastics, cheerleading, and soccer—activities that are also associated with a high risk of concussion.

Importantly, the post-injury experience also differs by sex. Studies suggest that girls may experience more prolonged symptoms following a concussion. They often report higher rates of headaches, dizziness, and emotional disturbances such as anxiety and mood changes. In contrast, boys are more likely to develop behavioral symptoms, including increased impulsivity and aggression, following a TBI. These patterns suggest that the neurobiological and psychological response to brain injury varies by sex, necessitating tailored approaches to assessment and intervention.

Recognizing these sex-based differences is essential in providing appropriate care and support. Pediatric TBI is far from a one-size-fits-all condition. Understanding how boys and girls differ in injury risk, symptom presentation, and recovery can inform more targeted and effective rehabilitation strategies. It also has implications for prevention—by addressing risk-taking behaviors and improving safety measures in gender-specific activities, we can reduce the likelihood of injury and enhance outcomes for all children. A nuanced understanding of these sex differences allows us to better support the unique challenges each child may face following a traumatic brain injury.

Psychosocial Factors

When we talk about pediatric brain injury, it's essential to look beyond the medical and cognitive dimensions and consider the broader psychosocial context in which these injuries occur. A child’s environment, family circumstances, and even the timing of the injury all play significant roles in both the risk of sustaining a traumatic brain injury and the process of recovery.

Research indicates that childhood TBIs most frequently happen on weekends, during holidays, and in the afternoon. This pattern suggests that many injuries occur during times when children are most likely to be engaged in high-energy, unsupervised activities, such as playing on playgrounds, riding bicycles, or participating in sports. These time frames often coincide with reduced adult supervision, increasing the likelihood of risky behaviors that can lead to head injuries.

Certain groups of children face a heightened risk for TBI due to socioeconomic and behavioral factors. Children from lower-income families are statistically more likely to sustain a brain injury and less likely to receive appropriate follow-up care. Several interconnected factors contribute to this disparity: limited access to safe recreational areas means children may play in more hazardous environments; the availability of protective equipment like helmets may be restricted; and financial or logistical barriers often prevent families from accessing rehabilitation services. These limitations can result in more severe and prolonged effects, placing these children at greater risk for long-term disability.

Additionally, children with pre-existing neurodevelopmental or behavioral conditions—such as ADHD, autism spectrum disorder, or emotional regulation difficulties—are also at increased risk for TBI. These children often display higher levels of impulsivity, have difficulty assessing risk, or face challenges with motor coordination. If they do sustain a brain injury, their recovery may be more complex due to overlapping difficulties in attention, self-regulation, and executive functioning. These challenges can compound post-injury, affecting their ability to reintegrate into school, maintain peer relationships, and manage daily routines.

As occupational therapy practitioners, we must look beyond the immediate clinical presentation and consider these contextual factors. Understanding a child’s environment, developmental background, and family situation allows us to deliver more effective and compassionate care. It also enables us to identify at-risk populations, advocate for necessary resources, and design interventions that address functional deficits and promote equity and long-term well-being. Pediatric TBI must be understood within the full scope of the child's lived experience—not just the injury itself, but the circumstances that shape its consequences and the path to recovery.

Assessments

Assessment is a critical first step in understanding the impact of TBI on a child's function. Because pediatric TBI affects multiple domains—physical, cognitive, emotional, and sensory—a comprehensive approach to assessment is essential. We can’t rely on just one evaluation area or a single tool. Each domain contributes valuable information about how the injury has altered the child’s abilities and how it may affect their participation in daily activities, school, and social life.

We will review some of the key tools used in pediatric TBI evaluation. These tools help us capture a complete picture of the child’s current status, guide clinical decision-making, and inform the development of individualized, meaningful interventions. A thoughtful and thorough assessment lays the foundation for practical support and long-term recovery.

Pediatric Glasgow Coma Scale

Here is an overview of the Pediatric Glasgow Coma Scale.

|

| > 1 year | < 1 year |

|

|

Eye opening | 4 | Spontaneously | Spontaneously

|

|

|

| 3 | To verbal command | To shout |

|

|

| 2 | To pain | To pain |

|

|

| 1 | No response | No response |

|

|

Best motor response

| 6 | Obeys | Spontaneous movements |

|

|

| 5 | Localizes pain | Localizes pain |

|

|

| 4 | Flexion-withdrawal | Flexion-withdrawal |

|

|

| 3 | Abnormal flexion | Abnormal flexion |

|

|

| 2 | Abnormal extension | Abnormal extension |

|

|

| 1 | No response | No response |

|

|

Best verbal response |

| >5 years | 2-5 years | 0-23 months |

|

| 5 | Oriented and converses | Appropriate words and phrases | Coos and smiles appropriately |

|

| 4 | Disoriented and converses | Inappropriate words | Cries |

|

| 3 | Inappropriate words | Cries and/or screams | Inappropriate crying/and/or screaming |

|

| 2 | Incomprehensible sounds | Grunts | Grunts |

|

| 1 | No response | No response | No response |

|

This is one of the first assessments typically administered immediately following a head injury. It evaluates three key areas: eye response, verbal response, and motor response, to determine the initial severity of the traumatic brain injury. The total score provides a quick snapshot of the child’s level of consciousness, with lower scores indicating a more severe injury. However, while this tool is helpful in the acute phase, it does not necessarily predict long-term outcomes. For that reason, additional assessments are essential to fully understand the impact of the injury over time and to guide rehabilitation planning.

Other Assessments

- Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory

- BRIEF-2

- Sensory Profile

- PEDI or PEDI-CAT

We also use the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory, which assesses overall health-related quality of life. This tool evaluates physical health, emotional well-being, and social functioning, including school performance. It’s particularly valuable for understanding how a child adjusts post-TBI and identifying specific domains where targeted intervention may be needed.

Another essential tool is the BRIEF-2, or the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function. This assessment focuses on executive function deficits, which are among the most common long-term consequences of pediatric traumatic brain injury. It evaluates critical areas such as working memory, cognitive flexibility, and emotional regulation, offering insight into how these challenges may affect a child’s daily life.

The Sensory Profile is also frequently used, as many children with TBI experience changes in sensory processing. This tool helps identify difficulties in regulating responses to touch, movement, sound, and visual input, as well as issues related to balance and coordination. Understanding these sensory challenges is key to supporting a child’s ability to function and participate in meaningful activities.

Finally, we have the Pediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory, which measures a child’s functional skills and level of independence. It provides detailed information on performance in self-care, mobility, and social functioning. This assessment helps guide intervention planning by clarifying how the brain injury affects everyday activities and routines.

Recovery

Recovery from pediatric traumatic brain injury is a gradual and often complex process that depends on several factors, including the severity of the injury, the child’s age, and the quality of support they receive during rehabilitation. While many children recover well from a mild TBI—often within a few weeks—there is a range in recovery timelines. For example, although many children with mild TBI show substantial improvement within the first seven to ten days, others may take one to three months to return to their baseline level of functioning fully.

Unlike other types of physical injuries, recovery from a TBI requires both physical and cognitive rest. Physical activity must be limited in the early stages to prevent secondary injury, but equally important is cognitive rest. This involves temporarily reducing schoolwork, screen time, and other mentally demanding activities. I recall working with a young girl who had sustained a mild TBI, and we needed to implement accommodations for her schoolwork and strictly monitor her screen exposure. These types of adjustments are critical because overexertion—mentally or physically—can significantly delay healing.

Many children with TBI also experience heightened sensitivity to light and sound, symptoms that can intensify headaches, dizziness, and fatigue. This sensitivity is prevalent in females. To support the brain’s healing process, limiting exposure to computers, video games, television, and smartphones during the initial recovery phase is essential. These types of stimuli can easily overstimulate the brain and prolong symptoms. Additionally, loud, brightly lit, or crowded environments should be avoided whenever possible in the early stages of recovery.

When we discuss pediatric TBI, the primary focus is often on the child, and rightfully so. However, it’s important to remember that recovery does not happen in isolation. The child’s environment, family support, and school accommodations significantly affect how effectively and fully the child can recover. By addressing the physical and psychosocial aspects of rehabilitation, we can create a more holistic recovery plan supporting the child’s long-term development and well-being.

Maternal Well-Being and Pediatric TBI

But what about the caregivers? One of the most often overlooked aspects of pediatric traumatic brain injury recovery is the emotional and financial burden placed on families, particularly on mothers. Research consistently shows that mothers of children with TBI experience significantly higher rates of depression and anxiety than mothers of children without a brain injury. This heightened emotional distress is not simply a reaction to the injury itself, but rather a reflection of the ongoing uncertainty and unpredictability surrounding the child’s recovery process. Chronic stress, emotional exhaustion, and feelings of guilt or self-blame—often present even when the injury was accidental—are common and deeply impactful.

The disruption to family life, coupled with concerns about the child’s long-term prognosis, creates an environment of sustained anxiety. Mothers, in particular, often manage numerous therapy appointments, medical follow-ups, and academic accommodations while trying to maintain some sense of normalcy for their families. This additional caregiving load can lead to financial strain, especially if a parent has to reduce work hours or leave their job altogether to meet their child’s needs. The result is a loss of income and an increase in out-of-pocket expenses related to medical care and support services. Over time, this ongoing pressure contributes to caregiver burnout, undermining family stability.

It’s essential to recognize that maternal mental health is directly linked to a child’s recovery trajectory. When a mother is experiencing high stress or untreated depression, children with TBI are more likely to show worsened cognitive, emotional, and behavioral outcomes. Conversely, a well-supported caregiver is more equipped to provide the consistent emotional regulation, guidance, and advocacy necessary for a child’s healing. Caregivers are not just passive observers in the recovery process but essential partners.

Traditional models of TBI treatment have often centered on physical rehabilitation and biomechanical recovery. While these components are undeniably important, they do not capture the full picture. The psychosocial dynamics of TBI—including caregiver well-being, family stress, and emotional support—are equally critical in shaping outcomes for the child. As occupational therapy practitioners, we must take a more holistic view, advocating for services and interventions that support the child and their caregiver. By prioritizing caregiver mental health, we lay the groundwork for more sustainable, effective recovery for the entire family system.

The Imperative for Psychosocial Focus in Pediatric TBI

Most traumatic brain injury interventions have traditionally focused on restoring motor function, improving balance, and targeting cognitive skills such as memory, attention, and executive function. While these areas are undeniably important, they represent only one side of the recovery process. Mental health, emotional resilience, and social reintegration are vital components of a child’s rehabilitation journey. When these psychosocial factors are overlooked, children with TBI face a significantly increased risk of emotional distress, behavioral challenges, and social isolation. They may struggle to maintain peer relationships, experience difficulty navigating the classroom environment, and encounter academic issues that persist long after their physical recovery appears complete.

As we've just discussed, pediatric TBI presents complex and lasting psychosocial challenges. Yet, much of the current research and available interventions still prioritize physical rehabilitation, often at the expense of these equally critical psychosocial dimensions. Although substantial evidence supports the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions in adults with TBI, similar research specific to pediatric populations remains limited. This gap is deeply problematic. Children are not simply smaller versions of adults; they have unique developmental trajectories, evolving cognitive abilities, and social-emotional needs that require developmentally appropriate, tailored intervention strategies.

When the psychosocial impacts of pediatric TBI are neglected, we run the risk of contributing to long-term consequences. These include social withdrawal, emotional dysregulation, academic underperformance, and reduced participation in meaningful daily activities. It’s not just about healing the brain—it’s about supporting the whole child within their family, school, and community contexts. As occupational therapy practitioners, we must advocate for a more balanced and holistic approach to TBI rehabilitation—one that values emotional recovery and social reintegration just as much as physical and cognitive restoration. Only then can we truly support children in optimal recovery and full participation in life.

Psychosocial Occupational Therapy Interventions for Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury: A Scoping Review

This led to a scoping review that I co-authored with a colleague and would like to share with you now. Our goal was to explore the types of psychosocial interventions currently used in pediatric traumatic brain injury, particularly those implemented by occupational therapists, and to assess how effective these interventions have been. In conducting this review, we aimed to understand the available research in this area comprehensively.

To ensure breadth and depth, we searched multiple databases—including PubMed, Cochrane, Embase, PsycNET, and Google Scholar—to include peer-reviewed studies and relevant gray literature. We intentionally did not limit the studies by publication date, as we wanted to incorporate foundational and more recent findings to get a complete picture of how this area has evolved. Our primary objective was to identify occupational therapy interventions addressing pediatric TBI's psychosocial outcomes and evaluate their effectiveness based on existing evidence.

From an initial pool of 836 abstracts, we conducted a rigorous multi-stage screening process, ultimately selecting 13 studies that met our inclusion criteria. These studies offered meaningful insights into the psychosocial aspects of pediatric TBI recovery and pointed to key areas that still require significant research and development. The included studies span a diverse range of geographic regions, with the most considerable coming from Canada, followed by the United States, Australia, the United Kingdom, Israel, and Mexico. This global distribution suggests that while international interest exists in this topic, the overall volume of high-quality studies remains limited.

Regarding content focus, 62% of the included studies addressed the psychosocial needs of children with TBI, while 38% examined specific psychosocial interventions used in occupational therapy. Regarding methodology, most of the research was needs-focused, primarily cohort and cross-sectional studies. Intervention-based research was notably sparse, with only one randomized controlled trial, two prospective intervention studies, and a handful of case studies identified. These findings confirm that although the psychosocial impact of pediatric TBI is widely acknowledged, there is still a lack of robust, high-quality evidence evaluating the effectiveness of occupational therapy interventions in this domain.

The studies we reviewed—spanning into 2025—highlighted significant and persistent emotional, social, and cognitive challenges faced by children following a traumatic brain injury. Many of these children experience elevated rates of anxiety, depression, and behavioral disorders, effects that can persist for years after the initial injury. Peer relationships are particularly vulnerable, with long-lasting difficulties in social engagement and increased externalizing behaviors extending into adolescence and adulthood. Academic challenges are also common, as children often show poor problem-solving skills, communication difficulties, and reduced school performance.

One particularly striking finding was a consistent reduction in playfulness among children aged 3 to 13. Play is a crucial part of social and cognitive development, and diminished playfulness may indicate deeper underlying deficits in areas such as executive functioning, emotional regulation, and peer interaction. Furthermore, longer recovery periods were associated with higher unmet occupational therapy needs. At 12 months post-injury, children were 4.67 times more likely to have unmet needs compared to at 6 months post-injury. This reinforces the importance of continued, long-term support for children recovering from TBI, especially in addressing their psychosocial development through meaningful, context-sensitive occupational therapy interventions.

OT Interventions for Psychosocial Needs: Children vs. Mothers

Now that we’ve established the many challenges faced by children with traumatic brain injury, let’s turn our attention to the psychosocial interventions explored in our scoping review. These interventions, though varied, share a common goal: to support children not just physically or cognitively, but emotionally and socially as well.

Among the most commonly identified interventions were app-based coaching, which uses digital platforms to build self-regulation and coping skills; virtual reality sessions, which simulate real-world social interactions and improve engagement; and the Cognitive Orientation to daily Occupational Performance (CO-OP) approach, which focuses on helping children develop problem-solving and self-regulation strategies for meaningful daily tasks. Other notable interventions included focused symptom counseling, which supports children in managing anxiety, frustration, and emotional regulation, and mindfulness-based yoga, which has been shown to enhance attention control and emotional resilience.

These interventions were associated with improved emotional regulation, participation, and overall quality of life. The CO-OP and focused symptom counseling, in particular, demonstrated significant improvements on post-concussion symptom assessments, reinforcing their promise as effective psychosocial strategies in pediatric TBI rehabilitation.

Despite these promising findings, our review also revealed significant limitations in the existing research. Short follow-up periods limited the ability to assess long-term impact, and inconsistent outcome measures made it difficult to compare findings across studies. Mild TBI cases were notably underrepresented, despite growing evidence that even mild injuries can have substantial psychosocial consequences. This underscores the need for larger, controlled studies with extended follow-up periods, standardized outcome measures, and a deliberate focus on including children with mild TBI. Without this, we risk overlooking children whose struggles are less visible but equally significant.

Our review also emphasized the importance of adopting a comprehensive, family-centered approach to care. Persistent psychosocial impairments—such as emotional difficulties, social isolation, and cognitive challenges—often extend into adolescence and adulthood. Early intervention is essential, but equally important is supporting caregivers, particularly mothers, who are usually the primary coordinators of care. When maternal stress and depression are unaddressed, children’s outcomes suffer. This is why caregiver education and support programs are critical—not only for the well-being of the parent but for the success of the child’s rehabilitation.

Children with severe TBI often receive more services, while those with milder injuries are left with gaps in care despite experiencing meaningful challenges. Occupational therapy practitioners can play a key role in identifying predictors of poor outcomes, tailoring interventions based on age, injury severity, and psychosocial risk factors, and ultimately bridging this gap.

Let’s take a deeper look at some of these interventions. On the child side, the most effective therapies included CO-OP, mindfulness-based interventions, virtual reality, and app-based coaching. CO-OP is a goal-oriented, problem-solving approach that teaches children self-regulation strategies to help them accomplish daily activities. For instance, a child struggling with dressing might be guided through breaking the task into manageable steps, using verbal self-guidance, and adapting strategies as needed. Mindfulness-based interventions might include deep breathing exercises or progressive muscle relaxation techniques for children experiencing anxiety or frustration, particularly in academic settings. Play-based therapy can enhance peer interactions, using pretend play, turn-taking, or emotional expression activities to strengthen social skills. Virtual reality and app-based platforms offer interactive, simulated environments where children can practice motor, cognitive, and social skills in a safe, gradually intensified setting. For example, a child who becomes overwhelmed in crowded spaces might rehearse navigating such environments in VR before facing them in real life.

Turning to caregivers—especially mothers—we know they play a critical role in pediatric TBI recovery. However, they also face immense stress, emotional burden, and unmet needs. Occupational therapy interventions tailored to caregivers focus on supporting their mental health and enhancing their ability to care effectively for their child. Caregiver-focused counseling may involve coaching sessions that build coping strategies, stress management techniques, and self-care routines. An OT might work with a mother experiencing burnout by helping her develop a manageable daily schedule, teaching time management, or connecting her with peer support groups. Mindful breathing or relaxation techniques can also be taught to help caregivers remain grounded and emotionally available during their child’s recovery journey.

Family-centered interventions engage both the child and the caregiver to address shared challenges. For example, suppose a mother is overwhelmed by balancing work and caregiving demands. In that case, an OT might help design an adaptive schedule that includes structured playtime and therapy in a realistic, sustainable format. Parent education groups are another powerful tool, covering sensory strategies, behavioral management techniques, and emotional regulation approaches that families can implement at home.

One particularly effective solution is web-based parent training. These programs offer structured, evidence-based strategies to help caregivers manage stress, build confidence, and support their child’s recovery. Unlike traditional in-person groups, these platforms offer flexibility, allowing parents to learn and apply skills at their own pace—a crucial benefit when managing the demands of caregiving. Studies show that participation in such programs leads to measurable reductions in caregiver depression and stress. Parents report feeling more competent in working behavior, structuring routines, and advocating for their child in healthcare and educational settings. Most importantly, children benefit when their caregivers are well-supported: improved emotional regulation, greater adherence to therapy plans, and enhanced overall recovery.

A typical web-based training program might include education on pediatric TBI, explaining how post-concussive symptoms manifest over time, or how injury can impact emotional regulation and cognition. It may offer stress management strategies like mindfulness and relaxation exercises, parenting skills training focused on behavior management and emotional coaching, and modules to build self-efficacy and resilience. Peer support forums and virtual coaching opportunities are often included, as well as a flexible, self-paced learning structure designed to accommodate caregivers’ busy schedules. Many of these programs offer optional live, synchronous sessions for added connection and accountability.

Effective pediatric TBI care must include both the child and the caregiver, with targeted, evidence-based interventions addressing their distinct but deeply interconnected needs. By focusing on psychosocial supports alongside traditional rehabilitation, we can foster more complete and sustainable recovery trajectories for children and strengthen the families who care for them.

Case Study

Let’s walk through a case study that illustrates the long-term psychosocial and functional challenges that can follow even a mild traumatic brain injury, and how occupational therapy can support both the child and caregiver through a comprehensive, family-centered approach.

Sophia is a seven-year-old girl who sustained a mild traumatic brain injury and a distal radius fracture after falling from a playground structure. She was hospitalized for five days. During her initial emergency department visit, a CT scan ruled out intracranial bleeding and skull fractures, and she was diagnosed with a mild TBI accompanied by post-concussive symptoms. Despite being classified as mild, Sophia continued to experience persistent headaches, dizziness, and difficulty concentrating—symptoms that can significantly interfere with a child’s daily functioning and development.

During her hospitalization, Sophia’s symptoms followed a trajectory commonly seen in pediatric mild TBI cases. In the first two days, she experienced acute symptoms including dizziness, nausea, fatigue, and light sensitivity. These symptoms often emerge immediately after the injury and disrupt basic daily activities. By days three to five, there was some improvement, and Sophia was discharged with instructions for activity restriction. Her mother was advised to monitor her closely for prolonged symptoms like headaches and fatigue. Since Sophia’s initial recovery appeared stable, no therapy was recommended at discharge, although a two-week follow-up was suggested.

However, this case highlights how symptoms of mild TBI can persist well beyond the acute phase. At the two-week follow-up, Sophia’s mother expressed new concerns. Although her wrist fracture was healing appropriately, Sophia continued to experience frequent headaches and fatigue that impacted her concentration in class. She was increasingly irritable, displaying emotional outbursts when her routine changed. Attention difficulties were interfering with her ability to complete schoolwork, and she began avoiding playground activities altogether, expressing fear of falling again. This is a key moment where we start to see the delayed psychosocial effects of TBI. In Sophia’s case, these emerged within two weeks, but these effects can appear months or even years later in many children.

Sophia began attending weekly sessions at an outpatient pediatric OT clinic following a referral. Her therapy plan was designed to address the ongoing functional and psychosocial challenges she was facing. Additionally, because her mother was experiencing high levels of stress and uncertainty in managing Sophia’s needs, we incorporated caregiver training to help structure the home and school environments in ways that would better support Sophia’s recovery.

Our occupational therapy interventions were structured around three primary areas:

Cognitive Rehabilitation – We focused on attention training and executive function strategies to help Sophia improve focus in class and manage multi-step tasks more effectively. Tools such as visual schedules, checklists, and time management techniques were introduced.

Emotional Regulation – Using sensory-based coping techniques, we guided Sophia through self-regulation exercises that addressed her emotional outbursts. We helped her build resilience in response to frustration or unexpected changes.

Social Reintegration – Sophia was gradually reintroduced to playground environments and peer interactions through graded exposure and confidence-building activities. Activities were structured to build trust in her body and reduce fear of reinjury.

Support for Sophia’s mother was equally integral to the success of the intervention. She received education on pediatric TBI and its recovery course, training in stress management strategies, and guidance on structuring daily routines at home. We worked together to establish consistent expectations, develop calming routines, and apply family-centered strategies, reinforcing Sophia’s emotional and social development through everyday activities.

As a result of these combined efforts, Sophia showed meaningful progress. There was a 20% improvement in her attention and working memory, and a 30% reduction in emotional outbursts. Her mother also experienced a 25% reduction in caregiver stress and an 18% increase in her confidence and self-efficacy in managing Sophia’s needs. In addition to ongoing outpatient therapy, a school-based OT consultation was provided to ensure that accommodations were implemented to support Sophia’s attention and self-regulation in the classroom.

This case study emphasizes that even a mild TBI can result in significant and lasting functional, emotional, and social challenges. A comprehensive occupational therapy approach—targeting both the child and caregiver—is vital in promoting long-term recovery and improving quality of life across all environments where the child lives and learns.

Summary

I hope this course was helpful to you. Thanks for your time.

Questions and Answers

As an adult, I've been told to exercise as tolerated when healing from a TBI. Is this the same for kids?

Yes. This guidance applies to both children and adults recovering from a traumatic brain injury (TBI). However, the specific recommendations may vary based on the type of TBI and the time elapsed since the injury. Physical exercise is often limited in the early stages of recovery, and activity is gradually reintroduced under clinical supervision.

Can you restate what you said about girls and neck control in gymnastics? Do they have more or less control than boys?

Girls generally have less neck control than boys, which can make them more susceptible to concussion-related injuries, particularly in sports like gymnastics. This physiological difference is vital in injury prevention and recovery strategies.

References

See additional handout.

Citation

Khan, S. (2025). Psychosocial approaches for pediatric TBI: Addressing the impact on children and maternal well-being. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5803. Available at www.occupationaltherapy.com