Introduction

Thank you all for joining me today. I am so thrilled to be here. I always love working with OTs so I thank you for allowing an SLP to share this information with you today. OTs are some of the most creative and inspiring people I know and being able to share with you a tool in your already innovative toolkit is a great honor for me. Today's presentation on the spaced retrieval technique is one that is very near and dear to my heart. I began using the technique as a graduate student in one of my clinical placements, and I was lucky enough to be included in the early research of this technique as well. I still find it to be one of the most used methods that I use with my clients, and I also teach this to my graduate SLP students in my position as a faculty member at Kent State. To get started, let's first talk a little bit about dementia and memory so we can have a good understanding of how the space retrieval technique works and how it can be used for you to use with your patients with cognitive impairments.

Dementia Review

- Dementia is not a specific disease

- Dementia is a descriptive term for a collection of symptoms that can be caused by a number of disorders that affect the brain.

- Alzheimer’s disease accounts for 60 to 80 percent of cases. Vascular dementia, which occurs after a stroke is the second most common dementia type.

Alzheimer’s Association 2020

Dementia is not a specific disease. It is a descriptive term for a collection of symptoms that can be caused by a number of disorders that affect the brain. This can be anything from a traumatic brain injury, stroke, Alzheimer's disease, or anything like that. We are talking about symptoms when we talk about dementia. According to the Alzheimer's Association, Alzheimer's disease accounts for 60 to 80% of cases of dementia. Vascular dementia occurs after a stroke and is the second most common type of dementia.

Research Tells Us...

- Dementia is the loss of mental functions involving thinking, memory, reasoning, and language to such an extent that it interferes with a person’s daily living.

- Dementia is a group of symptoms that can include:

- Language disturbances (e.g., aphasia, dysphasia, anomia)

- Challenging behaviors (e.g., repetitive questioning, wandering)

- Difficulties with activities of daily living (e.g., dressing, personal grooming)

- Personality disorders (e.g., disengagement, aggressive behaviors)

Alzheimer’s Association, 2020

According to research, we know that dementia is a loss of mental functions involving thinking, memory, reasoning, and language that impacts a person's ability to participate in their daily life. We can see these symptoms coming up in areas such as language disturbances, like word-finding, or in challenging behaviors. These challenging behaviors may include asking the same question over and over again, wandering, and things like that. They have difficulties with activities of daily living, a topic near and dear to the OTs heart. They will have trouble with sequencing for dressing and personal grooming, and we may also see changes in personality. They may also demonstrate disengagement, a lack of initiation, and some aggressive behavior.

Memory

- Memory is dependent on organizing incoming information (attention) and highly developed encoding skills

- Memory is critical to our ability to acquire language, develop high-level thinking, and effectively make decisions

We know that memory is dependent on organizing information. We have to attend to information before we can learn and encode it. We know that memory is critical to our ability to acquire language, develop high-level thinking, and effectively make decisions. Many times our patients have a narrow idea of what memory entails. However, there are a number of systems that are in place that impact how memory works, and we may have to work on different aspects of memory in order for that retention to happen.

Memory Stages

- Encoding, Storage, and Retrieval are interactive processes

- The ability of one process affects the quality of another

- Good encoding makes for good retrieval later on

- A deficit in one stage can lead to a deficit in another

When we think about memory stages, we look at the attention to the information, encoding it to make it meaningful, storing it, and being able to retrieve it via all the interactive processes. The ability of one of these processes affects the quality of another. We know that good encoding can make for good retrieval later. I always compare this making mnemonics when trying to remember certain things when studying in school. You try to make it meaningful to yourself in order to remember it better to assist with that retrieval. It is the same with our clients. We want to make things meaningful so that their attention and encoding is good for the goal of good retrieval. A deficit in one of these stages can lead to a deficit in another.

Memory Definitions

- Working Memory, Short Term Memory:

- Ability to use information as it’s being processed (remembering phone number)

- Primarily affected first with Alzheimer’s and other dementias

- Long Term Memory:

- Information from short term memory that is retained permanently

- Declarative and Procedural Memory

- Procedural memory is relatively-spared through the progression of dementia (FOUNDATION FOR SPACED RETRIEVAL TECHNIQUE)

- Long Term Memory can be affected by dementia in both storing information and retrieving it.

Working memory and short term memory refer to the ability to use information as it is being processed. This might be something like remembering a phone number, repeating it a few times, and then going ahead and dialing the number. Typically, that information is not necessarily encoded and retained as it is only being used at the moment. Working memory and short term memory primarily are affected first with Alzheimer's disease and other dementias.

Long term memory is where information from short term memory is stored and retained permanently. This includes declarative and procedural memory, and I am going to get into that in a little bit more detail as this is the key element to the spaced retrieval technique. How can we utilize long term memory and those preserved skills in order to help people retain information for a longer period of time? Procedural memory is relatively spared through the progression of dementia. This is another reason why this is so key to this technique because we want to be able to use something that is still intact as a springboard to help people remember things for as long as possible. Long term memory can be affected by dementia in both storing information and retrieving it, but the research shows that it is a little more spared than working and short term memory.

Learning & Memory in Dementia: Model of Memory

- Declarative Memory

- Facts

- Events

- World Knowledge

- Vocabulary

- Procedural Memory

- Skills

- Habits

- Simple Classical Conditioning

- Priming

Squire, 1994

Figure 1 shows a nice visual to help you to understand a little bit more about how long term memory works. Dr. Larry Squire was an innovator and researcher in the area of different types of memory. I would definitely recommend looking into his work.

Figure 1. Squire's work on memory.

I use this with my patients and their families when I am educating them on dementia and why there are certain changes in memory. Long term memory can be divided into declarative memory and procedural memory. Declarative memory is the portion of long term memory that holds information such as facts and events such as people's names, where you were earlier in the day, or something that happened to you. It could be also your knowledge of the world. This is also remembering certain facts that you have learned over the years. For example, it could be remembering that the capital of France is Paris. The final piece of declarative memory is vocabulary or language. This is knowing what something is, being able to label it, and then express that in verbal output. All of this can be relatively spared in dementia, but we can also see a lot of our patients struggle with these aspects. They may not be able to recall their loved ones' names or they cannot remember what they had for breakfast. They might struggle with remembering the name of something and with some cueing they may be able to recall that information. This might be with phonemic cues, like the first sound of the word, or a semantic cue, like a definition. Many times our patients will be able to recall information with those types of nudges, but it is still a little bit difficult. I like to compare this to a file cabinet where the drawers a little bit stuck. We can get to that information if we give it a little bit of a push.

On the flip side of that, procedural memory is the one that can be relatively spared throughout the dementia process. Procedural memories are our skills and habits. Examples are how we feed ourselves, tie our shoes, or get dressed. Another example is driving. It is something that we have repetitively practiced over a whole lifetime. Reading is another skill that is often spared. People can retain the ability to read far into the course of dementia. This does not mean that they can necessarily comprehend everything that is being read, but they can still utilize the processes that are needed to decode and read information. This is one reason why we use a lot of verbal or visual compensatory strategies with this population because it is a relative strength. In procedural memory, we also have simple classical conditioning. If you think back to psychology courses, this is a stimulus and response type of memory. A certain stimulus can elicit a certain response, and this is another aspect of the spaced retrieval technique. We can use a simple question or a command to teach a certain response. Then with practice, this becomes something that becomes automatic for the person to recall. The idea of priming is also stored in procedural memory. This is the idea that practice makes perfect. The more exposure a person has to a piece of information or something they need to learn, the better they are going to learn it. This is why there is a lot of repetition involved when we are working with patients with dementia or other cognitive impairments. This is also one of the reasons that repetition works as it is something that is stored in procedural memory, which we know to be relatively spared through the disease progression. Spaced retrieval is something that takes advantage of this procedural memory system. We can use repetition and set up a certain stimulus and response in the form of questions and responses or questions and actions to help a person be able to recall information. These skills and habits then become something that is a little bit more permanent and easily retained.

This is long term memory in a nutshell, and again, I use this with my patients and families to describe why we see those splintered skills in persons with dementia. They may ask, "I don't understand why my mom can't remember my name, but she's still able to remember how to play the piano." This is a good way to educate them. One skill is from the declarative memory system, while the other is procedural. Playing the piano has become an unconscious automatic thing that they can do. They do not have to really think about it, and it is a little bit more effortless. I also use this as a description for staff members in facilities as a good way to explain why patients can always seem to find their seats in the dining room. After they have been there for a few weeks, they know exactly where they sit, and if someone else is sitting in that seat, they are going to let them know. This is because the priming and repetition have happened. It has now turned into a skill or habit that when they enter that space, and their feet know where to go. We can see new learning happen with this population because they can learn new procedures if we present the information in such a way that is meaningful and give them lots of practice.

Mistaken Beliefs About Dementia

- Individuals with dementia cannot learn or remember information

- The best way to care for persons with dementia is to make them comfortable, accept their idiosyncrasies, and be patient with them.

There are many people out there who still believe people with dementia cannot learn to remember information, and that the best way to care for them is just to make them comfortable, accept those idiosyncrasies that they may have, and just be patient. While we do want to make them comfortable and be patient with them, we also want to be hopeful and focus on their strengths. The idea that people cannot learn with dementia is just flat out wrong. In fact, there is a lot of evidence out there that supports the idea that learning can indeed happen with persons with dementia. This depends on how that information is presented and how frequently they are able to use that information. Again, things in the procedural memory system may be retained. The example of the dining room in a facility setting might be a good thing to share with staff members who may think, "Well, there's not much we can do. They're never going to remember it anyway." Well, they learned where they sit for meals, and that was new information that they did not know prior to moving into a facility setting.

Circumvent the Deficits

- Persons with dementia do have weaknesses in the areas of learning and memory BUT a number of strengths exist as well.

- Ability to learn procedures

- Ability to read

- Research has shown that the learning of information and its retention depends heavily on how it is presented.

- KEY: Be aware of the weaknesses but FOCUS ON THE STRENGTHS!!!

Our goal, as therapists, is always to circumvent deficits. We are always looking for strengths, figuring out how to get around the weaknesses, and how to build off the strengths that we know are present. We know that persons with dementia have a lot of weaknesses, but their strengths may include things they have learned in their lifetime (e.g. reading), skills and habits, and their ability to learn new procedures as supported by their procedural memory system.

Behavioral Interventions for Dementia

- Can be Direct or Indirect

- Direct

- When an OT or other professional intervenes directly with individuals or group using an intervention

- Indirect

- OT or other professional trains caregivers in an intervention, modifies the environment, or develops activities to maximize function

- Spaced Retrieval can be both Direct and Indirect

- Direct

Mahendra & Hopper et. al, 2008

Research has shown that the learning of information and its retention depends heavily on how it is presented. As we said, there has to be meaning behind anything that we learn in order for us to want to remember it.

The Spaced-Retrieval Technique

All of you are taking this course, hopefully, because you have an interest in knowing more about this technique and how you can use it. The idea is that because you are paying attention to the information, it is going to be something that has meaning to you in order to be able to apply it. We have to really look at that idea for our patients as well. We do not want to focus on something as a result of what we see in assessment or what the family or staff member is suggesting that we work on, but rather, we need to tap into what is important to that patient. What is in it for them? When we look at things from that angle, it can really make that information more meaningful to them, which again, puts them in a better position to recall it. We always want to be aware of the weaknesses, but we always want to focus on their strengths. I find that working from that perspective really helps my practice in general. Many of our clients have a high level of issues going on, but we need to find what abilities remain and look at things through that lens. This is going to make it a much more positive experience for the patient and for us.

When we think about behavioral interventions for dementia, this is something that spaced retrieval would fall under. These can be either direct or indirect. Direct behavioral intervention for dementia would be something like when an OT or another professional intervenes directly with individuals or a group using an intervention. Thus, spaced retrieval would be an example of direct intervention. Whereas, an indirect intervention would be when you as an OT or other professionals train caregivers in an intervention, modify the environment, or develop activities to maximize function. Spaced retrieval falls under both of those categories because you as an OT can use this technique with your patients directly in sessions or you could train caregivers, other staff members, or family on how to use it.

Spaced Retrieval (SR)

- Technique used to help persons with cognitive impairments recall important information over progressively longer intervals of time.

- First used to address face-name learning in non-impaired individuals

- Has been used successfully with patients with Alzheimer’s Disease, Traumatic Brain Injury, Parkinson’s Disease, and Dementia related to HIV (Bourgeois et. al, 2001; Camp et. al, 2008; Neundorfer et. al, 2004; Malone et. al, 2007)

- Is an effective tool that therapists can use to help clients reach their goals in rehab therapy and is billable and reimbursable.

- Takes advantage of the procedural memory system and is success-based.

Spaced retrieval is a technique used to help persons with cognitive impairment to recall important information over progressively longer intervals of time. That is the "space" in the spaced retrieval. We are spacing out the interval of time that we want the person to be able to recall information and giving them practice at those longer intervals to shape the recall of that information, and hopefully, get it to move into long term memory.

It was first used to address face-name learning in non-impaired individuals. Back in the late 70s, some researchers in the United Kingdom used this technique with university students to see if they could recall the names of people in pictures that they provided to them. They spaced out the retrieval of that information over progressively longer intervals of time using lots of repetition or rehearsal. What they found in those studies is that the students who are non-impaired actually remembered the names of the people in the pictures much better using this spaced retrieval technique.

Then, over the years, this method has been applied in a rehabilitation context. It has been used in a lot of studies with clients with Alzheimer's, traumatic brain injury, Parkinson's disease, and dementia-related to HIV. There is a lot of great evidence out there about the use of this technique, and the body of research goes back a number of years from the late 70s to now. This is a strong body of evidence that this technique can be used with many different populations successfully.

Spaced retrieval is an effective tool that therapists can use to help clients reach their goals that is billable and reimbursable, which we know is super important in a lot of contexts. It takes advantage of that procedural memory system, and it is success-oriented. We want people to experience success when using this technique and that is another reason why I really like it. It is a great way of working with clients and allows them to feel positive about themselves. Typically, when someone has memory issues, they can be very hard on themselves. The can feel bad about some of the abilities that they are losing. This is a way to turn that around a little bit.

Goal of SR

- To enable individuals to remember information for long periods (days, weeks, months, years) so that they can achieve long-term treatment goals.

- Therapists teach clients strategies that compensate for memory impairments, using procedural memory, including reading and repetitive priming.

- In addition, SR uses external aids to compensate for memory.

(Brush and Camp, 1998)

The goal is to enable individuals to remember information for longer periods. We want to start to push that time out as we are working with a client so that they are able to remember things for days, weeks, months, and even years to be able to achieve long term treatment goals. A lot of the research has seen people retaining information for six-plus months and even longer in some cases depending on the level of impairment and their diagnosis. We are seeing people be able to remember information for clinically significant periods of time.

What happens is therapists teach clients strategies that compensate for memory impairment by using procedural memory. We use things like reading and repetitive priming to be able to help people retain this information. We also use things like external aids to help them to compensate as well. This can be written or auditory cues. There are many ways that we can bulk up some of these supports when using this technique, and we will get into those today.

Steps

- Begin with a prompt question for the target behavior and teach the client to recall the correct answer.

- When retrieval is successful, the interval preceding the next recall test is increased.

- If a recall failure occurs, the participant is told the correct response and asked to repeat it.

- Errorless learning: minimization of error responses during the presentation of target stimuli (Sohlberg & Turkstra, 2011).

- The following interval length returns to the last interval at which recall was successful.

You begin with a prompt question for a target behavior and teach the client to recall the correct answer. This goes back to that stimulus-response idea with simple classical conditioning that we see preserved in long term memory or procedural memory. We are going to start with a prompt of something that we want to work on, and then we are going to try to teach a particular answer or response. When the patient is able to retrieve information successfully, we increase the time that they are going to practice that next answer.

If the patient has trouble remembering an answer, they are told the correct response and asked to repeat it. This is a key piece of the technique as this is errorless learning. Errorless learning is the minimization of error responses during the presentation of target stimuli. It does not mean that people are not going to make errors. However, if they do make an error, we are going to replace that error by giving them the correct response or the action that we are seeking. Then, we ask the question or give them the prompt again and give them the opportunity to immediately respond. Typically, we tell someone the correct answer, and then move on. What is key about this technique is that if an error is made, we immediately give the client or patient the correct response we are seeking, give them a chance to repeat that, and then give them more opportunities to practice. This is a success-oriented approach.

If the patient makes a mistake, we go back to the time interval where they were last successful and only increase the time if they are able to correctly respond. This is the nuts and bolts of what this technique looks like.

Treatment Example

- Goal: “Client will independently recall the location of daily schedule to complete ADL’s, improve attendance at & participation in meals, and engage with peers 90% of trials.”

- Question: “Where should you look to find your daily schedule?”

- Answer: “Look at my walker”

Let's take a look at an example here. We have a goal that the client will independently recall the location of the daily schedule to complete their ADLs improve attendance and participation in meals and engage with peers. We might attach something like a visual schedule to their walker as seen in Figure 1.

Figure 2. Visual schedule on a walker.

The prompt question that I might use would be, "Where should you look to find your daily schedule?" The response would be, "To look at my walker." This could be a very simple way to set this up. I might sit down with the client and say, "We are going to work on remembering where you need to be every day since it can be hard to keep track of your schedule. Let's take a look at what I wrote down." I would have that index card and look it over with the client, making sure they can read it and that the print is big enough. I am involving the patient in every step and making sure the information that I want them to learn is something that is meaningful to them."Does it look good here, or should we move it down over here?" Then I might say, "I am going to ask you a question and I want you to tell me the answer. The question is, 'Where should you look to find your daily schedule?' And, I would like you to tell me, 'Look at my walker'." You then ask them the question, "Where should you look to find your daily schedule?" They say, "Look at my walker." That is a correct response, and what we call zero seconds or immediate recall. I give them the question and immediately ask for a response. This is checking for attention, and then we work on encoding it to make it retrievable.

Treatment Trials

- Trial 1 (0 Seconds): Client Responds CORRECTLY

- Trial 2 (10 Seconds): Client Responds CORRECTLY

- Trial 3 (30 Seconds): Client Responds CORRECTLY

- Trial 4 (1 Minute): Client Responds INCORRECTLY

- The therapist provides the client with the correct response (______), asks the client the prompt question again, allows the client to respond, and returns to the interval at which the client was last successful.

- Trial 5 (30 Seconds): Client Responds CORRECTLY

- Trial 5 (1 Minute): Client Responds CORRECTLY

- The client continues session; Therapist then probes through other therapy activities to continue training/practice of the desired skill.

The next step is to space out the retrieval of that information. As you can see here, I am just increasing the time a little bit by using baby steps at the beginning. We go from immediate recall to asking again 10 seconds later. "Where should you look to find your daily schedule?" They say, "Look at my walker." I say, "That's great." I want to make sure that I am pairing the verbal response with a motor movement as this can help to increase the retention of information. I want to make sure that they can find it and then I am going to say, "Great. All right, now we are going to move on up." Now maybe I wait 30 seconds before I ask again. We go from 10 seconds and double it to 20 seconds later. I ask, "Where do you look to find your daily schedule?" and the client answers, "My walker." Now, I would increase to a minute.

Now, let's say I ask the question at one minute and the client says, "Not sure." What I would do is immediately give them the correct response and say, "When I ask you, 'where should you look to find your daily schedule,' I would like you to say, 'Look at my walker.' Let's try it again. Where should you look to find your daily schedule?" They say, "Look at my walker." This is the errorless learning piece. They missed it, and I give them the correct answer in response. They give it back to me, and then I return to the last interval where they were successful, which is 30 seconds. If they get it correct, again you are going to gradually increase the time. The client would continue the session, and we would just continue to increase the time. Maybe after a minute, I go to two minutes, four minutes, eight minutes, 16 minutes, and so on. You want to gradually increase and double the time. However, you do not necessarily have to double the time. For example, if you find a patient is not able to retain information at a four-minute interval but is able to retain it for two minutes, then I might go ahead and move to a three-minute interval. This is how the sessions typically go, and as those time intervals increase, you could start working on some other therapy goals. This way you can superimpose the spaced retrieval question into the other things you are working on in your treatment.

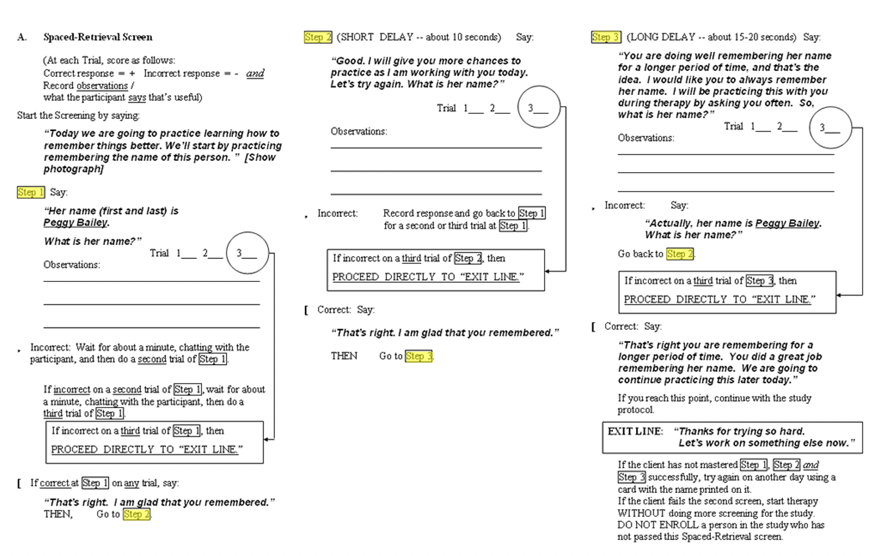

SR Screening Measure

- Complete Screening Process

- Quick and Easy

- Tests clients’responses to correctly recall a target name over 3 different time intervals (immediately after presentation, 10 seconds later, and 15 to 20 seconds after that)

- The client has 3 trials at each time interval to recall the target name correctly to pass the screen

- CAN FOLD SR SCREEN INTO INITIAL CLIENT EVALUATION/ADMISSION INTERVIEW

Many people ask, "How do you know if a patient is right for this method or not? There is a really easy screening measure that you can use. This is one that we used in a lot of the initial research with this technique, and it is one that I still use to this day. This is available in a lot of the treatment books that you see related to spaced retrieval. I want to give you a snapshot of what it looks like so you can easily implement it and decide if some of your patients would be good candidates for this technique. It is a really easy process. It tests a client or a patient's responses to correctly recall a target name over three different time intervals. The client has three trials at each time interval to recall that target name in order to pass the screen. This is something that can easily be folded into an initial evaluation or an admission interview.

Figure 3 shows a quick little snapshot of what the screen looks like.

Figure 3. Spaced-Retrieval Screen.

You can use this in any way shape or form that makes sense for you. It does not have to necessarily follow all the specifics of what is written here in terms of the verbiage, but this can give you a general idea of how this is implemented. What we did in the initial research was to use a stock photo of a woman and have the patients recall that her name was Peggy Bailey. At the beginning of the screen, you can see that we say, "Today, we are going to practice learning how to remember things better. We're going to start by practicing remembering the name of this person." We would show the picture. "Her name is Peggy Bailey," and then the prompt question would be, "What is her name?" If the patient was able to say "Peggy Bailey" at immediate recall, we put an X for Trial 1. "That's right. I'm glad that you remembered." We then increased to 10 seconds. Again, with every correct response, we increased a little bit of time. I would then say something like, "Good, I am going to give you more chances to practice as I'm working with you today. Let's try it again. "What is her name?" If the patient got it correct, we marked that as correct and increased the time to 15 to 20 seconds later. "Great You are doing well remembering her name for longer periods of time, and that is the idea. I would like you to always remember her name. I will be practicing this with you during therapy by asking you often. So, what is her name?" If the client is able to remember that at 15 to 20 seconds, then you go ahead and X that, and then they pass the screen.

You could do this very easily with a stock photo of your own and use another name if you wanted. You could even use your own. "Today, I thought it would be fun if we could practice remembering my name since we are going to be working together for a bit. "When I ask you what my name is, "I would like you to say, 'Megan Malone'." It is important to flip over your name tag if you use yourself to decrease visual cues while you are assessing if they can retain any new information.

Again, if the patient makes a mistake, you need to return back to the time that they last got it correct. If patients have trouble with this, it does not mean that they are not a good candidate. You may just want to try to get the information inputted in a different way. For example, I have done a screen where the patient is not verbally recalling the information well. I might write down the name that I am looking for them to remember on an index card and have them read it. Then, in between the time intervals, flip that card over so they are not doing any rehearsal of the name. Then, when I ask them the question again, they can turn the card over and read it. I am asking them to perform an action by reading the response versus just verbally recalling the name. This is another option if you feel like they might struggle with retaining verbal information or have a significant hearing impairment. Pairing that verbal response with a motor action is another great way for them to learn new information. You may also teach them to perform a physical response to commands or questions versus only verbal responses. This is something you can easily implement into an evaluation.

Patients who typically do better with this method are those that have scored higher on the MMSE, the MoCA, or the Slums. If they score below a seven on those, they typically are not the best candidates for use of this technique. I always say go ahead and do the screening as it only takes a couple of seconds. The results can tell you if the person can remember new information in this way. It is important to give everybody a chance, and it is so easy to implement.

SR Goals: Prompt Question and Answer Examples

- Disorientation

- “Where do you live?” (Answer: Name of Facility)

- “What is your room number?” (Answer: Room #)

- “What is your address?” (Answer: Client’s address)

- Repetitive Questioning

- Dependent upon the question being asked

These are just a couple of easy prompts. You are only limited to your imagination in terms of what you could use with this technique. It could be something like working on disorientation goals. Where do you live? Maybe someone has moved into a new facility, and you want them to recall that information. Perhaps, they are asking repetitively where they are or what their room number is. This could be used to help them to remember their room number or sometimes, I might have them look for certain landmarks. "How do you find your room?" Their response might be, "I look for the big red ribbon on the door." This might be a little bit more meaningful than a room number which tends to not have a lot of meaning to people. Or, you could as, "What is your address?" for someone who is living at home. They might want to know what time meals are served or when their loved one is coming to visit. You might be able to teach some things like that using this technique.

- Energy Conservation:

- Question: “What should you do before you begin a task?”

- Answer: ”Gather everything I need”

- IADL:

- Question: ”How do you remember which medicines you take?”

- Answer: “Look at my list”

- Adaptive Equipment:

- Question: “How should you reach for items safely?”

- Answer: “Use my reacher.”

Here are a couple of prompts related to occupational therapy treatment. For energy conservation, you might ask, "What should you do before you begin a task? The answer could be, "Gather everything that I need." There could be questions related to medications. "How do you remember which medicines you take? The answer might be, "I look at my list." An adaptive equipment question could be, "How should you reach for items safely?" The correct response, "I use my reacher." These are some simple things that can be addressed using this technique. You could start by having them remember some of this information, and then you could even use the technique for them to remember how to use those things.

What Happens After the First SR Session?

- Therapist documents patient response to treatment and longest time interval attained

- The therapist begins (Trial 1 of the next session) by asking the client the prompt question and seeing if the client is immediately able to give the correct response.

- This provides the client with an opportunity to demonstrate recall since the last treatment session, which may be 24 hours or more.

- If the client can recall the correct answer to the prompt question (and the associated behavior, if applicable) then training on the question can cease for that session.

- If the client cannot recall the correct response, the clinician provides the correct answer, asks the client the prompt question again, allows the client to respond to demonstrate immediate recall and then training should resume, returning to the last time interval the client correctly recalled the response to in the previous session.

Let's say we get through that first session of having them remember their schedule attached to their walker and they are able to retain the information pretty well. What would we do after that first session? You would write down the longest interval they were able to recall the information. Then, if I was going to see them a day or two later, the first thing I would do is ask the question, "Where should you find your daily schedule?" If they were able to remember that information, this shows that they were able to retain it for much longer than that eight minutes they did in that first session, maybe even over 24-48 hours. In this case, I do not need to reduce down to smaller intervals. I can go ahead and leave that question alone for a bit. What the research says is that you do not have to necessarily work on that prompt and response practice throughout that next session if they get it correct at that first trial. I always like to pepper that question in there maybe not as stringently with time intervals as you did in the first one, but maybe just to make sure that retention is there. As the session goes on, I might ask again, "Now, how do you find it?" or "Where do you find your daily schedule?" to see if it is sticking or not.

Basically, what you are going to do is always start subsequent sessions by asking the prompt question and seeing if they can remember it. Like we said, if the client can recall the correct information, then you cease training for that session, but I tend to pepper in a few other questions or ask that same question a little bit throughout the rest of the session just to make sure. However, if in a later session they cannot recall it, then we are going to do exactly what we would do in the first session. I would give them the correct response, "You look at your walker." I would then backtrack to see how they did at the last session (e.g. 8 min.) and then ask the question again in that time frame. You give them credit for what they were able to accomplish in that first session. If they missed it at eight minutes, then I would probably reduce back down to four minutes, et cetera. You reduce the time if they missed the question and increase the time if they get it correct.

- Subsequent session example:

- At the start of any session following the initial training session on a prompt question/response, the clinician should allow the client to demonstrate recall of the information by asking the prompt question.

- The client has a left-sided weakness.

- Prompt ?: “How should you put on a shirt?;

- Trial 1: ”Use my dressing chart.”

- Response Correct: Reinforce action or complete action & discontinue training for the remainder of the session (may choose to “spot check” retention of response throughout but formal timing of trials not necessary)

- Response Incorrect: Say, “Actually, you use your dressing chart. (provide a correct response); “How should you put on a shirt? (ask the prompt question again). The client responds “Use my dressing chart.” “Good. Let’s look at your chart.”. Let’s keep practicing-return to last successful time interval attained in the previous session (e.g. 8 min), continue SR training based on the client’s responses.

Here is our subsequent session example. Following that initial training on a prompt question or response, the clinician should allow the client to demonstrate recall the information by asking that prompt. Let's say our client has some left-sided weakness, you may want them to work on putting on a shirt. You could ask, "How should you put on a shirt?" The response could be, "Use my dressing chart." If they get it right, I would want to then see them in the next session, reinforce that action, have them complete it, and then I might discontinue training for that remainder of that session. Remember, you can spot-check retention throughout just to make sure they have remembered it. If they get it incorrect, I would say something like, "Use your dressing chart," and then show that to them. "Let's try it again. How should you put on a shirt?" The client responds, "I use my dressing chart." "Good, let's look at your chart, and then let's keep practicing." I would then return to the last successful time interval in the prior session.

When is SR Goal Considered Mastered?

- If a client is able to correctly respond to the prompt question and/or perform the targeted strategy at the beginning of 3 consecutive therapy sessions, the goal is considered mastered.

- It is important to make sure that the client is consistently performing the targeted strategy or response before discharging the goal.

When is a space retrieval goal considered mastered? Typically, the rule of thumb is if a client can recall information to a prompt question or perform a targeted strategy at the beginning of three consecutive sessions, then the goal can be considered mastered. If they are consistently recalling that information or the action that you want them to remember, then you are probably seeing some good retention happening. It is important to make sure that the client is consistently performing a targeted strategy before you discontinue it. Sometimes, people can answer a question correctly, but they do not follow through with the desired action. We also want to make sure that that is in place.

How Much SR Training Does a Client Usually Need?

- The amount of training required by a client will vary.

- The number of sessions is dependent upon:

- Level of cognitive impairment of an individual client

- Frequency of the sessions

- A number of goals are being addressed using SR.

(Clients enrolled in more frequent SR treatment sessions (i.e. 5 days week vs. 2 days/week) are likely to attain their goals more quickly.)

Training is going to be In terms of the type of client so it depends. It also depends on how many sessions you are seeing them for and the frequency of those sessions. If you are seeing them five days a week, it is likely that they are going to demonstrate good recall. However, if you are seeing a client only twice a week, that might decline. It also depends upon the number of goals being addressed and how many different things that you are working on. Research shows that clients enrolled in more frequent treatment are going to attain their goals more quickly which is pretty obvious. It is going to vary. I always want to see that that retention is happening that they are following through before I go ahead and discharge something, and it may take a little time.

There have been times where I have had to tweak the prompt question or the response based on the client. Maybe I have had two sessions where they are really not getting it. I may need to assess if the question is too long. Remember, working memory usually only holds about seven to nine pieces of information. Thus, we do not want that question to be something that they either do not attend or cannot remember the response. I might have to tweak the length or the concreteness of that question. I have had a client who needed to take their cane with them. When asked, "What do you need when you walk?" they could not say the correct response. However, when I asked them, "What would you call this?" when pointing to their cane, they responded, "That's a walking stick." I should have asked them from the beginning, "What do you call this?" You want to use a meaningful response. Do not get too discouraged if a client does not do well initially. You may have to play with it a little bit, and that is completely okay. There are many things that go into learning and retention so we may have to adjust our approach to make it more meaningful to each client.

- Goal possibilities are endless

- SR goals are NOT written any differently than other goals (SMART goals; ICF) (CMS, 2020)

- FUNCTIONAL GOAL = SR GOAL

Again, the goal possibilities are endless. The goals are not written any differently when using this technique than they are for anything else. There are SMART goal guidelines that guide how to make goals that are measurable, attainable, and time-limited. This above link from CMS is about mapping therapy goals according to the ICF model. I encourage you to take a quick look at that if you want to know more information on some good goal writing techniques. A functional goal equals a spaced retrieval goal. If you are already working on great things with your client that are functional, which I am sure you are, you might be able to use this technique to help them reach those goals.

- Measurement of goal attainment can be determined by the area of focus & what allows for the best measurement of progress.

- by percentage or number of trials (“80% of the time”; 4/5 trials)

- “Patient will recall and demonstrate energy conservation techniques to decrease fatigue 80% of opportunities during a given activity.”

- by percentage or number of trials (“80% of the time”; 4/5 trials)

OR

- Recalling or demonstrating target response for a set number of sessions (3 sessions recommended)

- “Patient will recall and demonstrate the strategy of properly using grab bar to transfer to shower at the initial trial of 3 consecutive therapy sessions using SR”

In terms of how goals are attained and the measurement of them, you could do it any way that makes sense. You could do it by a percentage or number of trials. The patient will recall and demonstrate energy conservation techniques to decrease fatigue 80% of opportunities during a given activity. You want to see if they are able to actually apply the techniques you are using that. "Patient will recall and demonstrate the strategy of properly using a grab bar to transfer to shower at the initial trial of three consecutive sessions using spaced retrieval." This is just a tool in the toolkit that is going to help you work on those goals and help clients attain those goals.

SR & Documentation

- SR is considered to be a MODALITY or APPROACH that therapists may use to help clients reach their goals.

- SR does not fit one particular diagnosis category

- Use the ICD 10 Code that corresponds to the goal area you are addressing

Spaced retrieval is a modality or an approach. There are no changes in terms of the diagnosis category. You would use the same ICD 10 codes for the things that you are working on with your clients. Again, this is just a method that you can use that can help your clients who have cognitive impairment.

SR Decision Making

- Questions to ask yourself when preparing to begin SR with a client:

- What are the strengths of the client? What are the weaknesses (physical impairment, vision, etc.)?

- What are the challenging behaviors being exhibited?

- What prompt question & response will be used and is it and the answer meaningful for the client?

- What other staff/family members will be involved in the training/carryover?

A couple of quick questions to think about in terms of making decisions. I always start with these with myself. What are the strengths of the client? Using a strengths approach is important to circumvent those deficits and build on their abilities. What are the weaknesses? Is there a physical impairment or visual impairment? Are there any challenges behaviors being exhibited? A lot of times we see speech or OT being called in to assist with clients who are exhibiting unsafe behaviors, have repetitive question asking or are wandering. Are there other ways that we could use spaced retrieval to address those? What are the prompt questions and responses that are meaningful and useful to that client? Like I said before, you may have to tweak this a little bit. Do not get discouraged if it does not work out of the gate. I had one client that wanted to call her call button Taco Bell because she really liked to eat Taco Bell. I said, "We will call it whatever you want as long as you use it."

SR: An Interdisciplinary Process

- Caregiver/Family Input:

- Consult with family/caregivers for possible goal ideas = INCREASES BUY-IN AND COOPERATION

- Work on incorporating the patient and family’s personal goals if possible.

- Share prompts/responses with caregivers/staff after a patient has demonstrated consistent success to increase generalization.

We also need to think about what other staff or family may be involved in the training or carry over. As we talked about earlier, they can have good input on what a good prompt or response might be and they can assist with this outside of the therapy context. The more we consult with family and caregivers, the better the buy-in and cooperation we are going to get down the road with generalizing this. I always think about incorporating patient family goals. We may have our own goals in mind, and that is completely fine. We want to address those based on what we see in the evaluation and what we feel is important for patient safety. However, you should also ask, "What would be something you would want to remember?" This can open up the therapy process. They may not believe you that you can help them to remember things better, but if you can show them via something that means something to them, this can be an important part of the process.

Case Study

- 75-year-old male; resident of assisted living facility. Diagnoses include Parkinson’s disease and CVA 3-months prior. Referred by the physician to receive occupational therapy services through home health upon discharge to home.

- The patient is experiencing cognitive decline, is at risk for falls, and is experiencing a decline in independence in ADL/IADLs.

- Patient Goal: “To remain in the home and as independent as possible”

Here is a 75-year-old male resident of an assisted living facility. His diagnoses include Parkinson's and a CVA. He was referred by the physician to get OT through home health care. He is experiencing a cognitive decline, a risk for falls, a decline in independence in ADLs and IADLs. The goal is for the patient is to remain at home and be as independent as possible.

- Examples of goal areas:

- Dressing

- Showering

- Bed mobility

- Manage freezing episodes when completing mobility-related activities to reduce fall risk

- Completion of a home exercise program

- SR goal: “Patient will recall and demonstrate strategies to manage freezing episodes during movement to reduce fall risk at the initial trial of 3 consecutive sessions using the spaced retrieval technique.”

Goals include dressing, showering, and bed mobility. It is also important that he can manage freezing episodes when completing mobility-related activities to reduce fall risk and complete have a home exercise program. One example of a spaced retrieval goal here could be that the "Patient will recall and demonstrate strategies to manage those freezing episodes during movement to reduce fall risk at the initial trial of three consecutive sessions using the spaced retrieval technique. Freezing episodes can occur during the initiation of movement, during multitasking, stopping, or slowing pace. In stressful situations or in crowds, we can see this type of freezing happen more often. You could help the client to remember the triggers or how to manage those. These include shifting weight or singing a song. Spaced retrieval could help with the retention of these compensatory strategies. A visual could also be put on their walker.

Wrap-up

I hope you enjoyed learning about this technique. You can read reach out to me at any time with additional questions. I am happy to be here for you.

Questions and Answers

What has been your experience using SR with clients with significant visual impairment?

That is an excellent question. I have had a lot of clients who have had visual impairments. You may not be able to use all the visual cues that you want, but you may be able to alter the size of the font. As you all know, when working with low vision clients, it can help to use a white background with black print, an Arial or bolder font, or larger print can make a big difference. It is also important to have good lighting. You can also use auditory strategies using a recordable device. Some picture frames even have this recording option. They could hit a button to recall the information.

Do you ever find the clients become irritated with repetitive questions?

Yes, indeed. I have had many clients say to me, "Are you asking me that question again?" Preemptively I like to say, "I'm going to be asking you this a lot and it might get a little irritating, but it is a way that we are going to help you remember the information. So, just bear with me." Most of the time, they are pretty open to that. Depending on their level of comprehension, I may even explain in more detail the science behind it. "This is a way that can help people remember things a little better. We have to practice it a lot at first in order for that to be something that sticks." Most people are pretty open to that, especially if it is something that they really want to remember. If we can make the case for why it is important for them to remember, like, "We don't want to have a fall again. I want to make sure that you remember to push off from the arms of the chair before you stand." Often, they will buy into that as they do not want to fall.

For those that cannot read or write, how do we use spaced retrieval when they are also unable to verbally recall?

In this case, you could use a picture or just action in general. "How should you stand from your chair?" If they put both of their hands on the sides of the chair and then push off, that is the response that you are looking for. It does not always have to be something verbal like them writing or reading something. I have had lots of nonverbal patients, but I looked for them to then show me the action.

Do you ever coordinate with other professionals to create a prompt so that you can increase repetition through interactions with OT, PT, SLP, Nursing?

Yes, all the time. I am always looking for the best way to get the patient to retain the information. So, you could definitely coordinate with other disciplines. You will just need to decide between the disciplines about who is going to be addressing it. You could get their input about what goals or pertinent prompts to use. Then, as the patient is getting more proficient in that recall, then you can share that with those other disciplines so that they can implement that strategy when those situations arise.

Can this be used with anyone who has a cognitive impairment? For example, can this be used with clients with severe depression or cancer?

Yes. The bottom line is that this technique can be used with many different populations. Memory is memory and the basic structures of how memory works are constant in all of us. How memory is impaired may differ, but in terms of what is available to all of us in terms of long term memory and being able to be responsive to this type of cueing is something that can be applicable to many different disorders. I would highly encourage you to not limit yourself to using it with a dementia diagnosis. As you can see from those early slides, we talked about it being used with TBI, HIV, depression, and so on. We know depression could be memory impairment related, but that could be something that could be reversible. However, we want to make sure that we give people the help they need in the moments that they need it. So, I think the technique would definitely be applicable to any population that you are working with. I have heard lots of people say that they use this even with their loved ones who may not have impairments like their child with their homework. Memory structures are going to be universal across human beings so you do not have to have an impairment to use this technique successfully.

Do you ever phrase responses to mimic a social story?

That is an interesting question. I like that. You could definitely do something like that if the patient can handle it. The length of the response may come into play. Trial and error go into a lot of what we do, and I would love to hear if you try that. You could use a social story to make it meaningful or as a way to introduce the need for the prompt. This could set the stage for what you are doing.

Can responses focus on more than one item like total hip precautions?

Yeah, you could definitely have them recall more than one thing. It just depends on what you feel that they can handle. I think you are going to find that out pretty quickly. What I might recommend is to direct them to a visual. "What are your hip precautions?" Or, "How do you remember your hip precautions?" Then you can give them a written list or chart. "What are your most important hip precautions?" If there are things that they do not tend to recall or really put them at risk, I might start with t