Course Outline

Hello everyone. Currently, I am an assistant professor at Georgia State University. My email is attached. I am happy to hear from people.

- Knowledge and use of motor learning principles

- The use of Knowledge Translation with the Knowledge to Action model

- Motor learning techniques: Task-Oriented/Specific Training, Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy, Cognitive Orientation to Occupational Performance (CO-OP)

- Motivational strategies and how to promote adherence to motor learning techniques

- Summary, Q & A

This is our outline. I am going to touch on knowledge and the use of motor learning principles. Then, I will talk about knowledge translation, the conceptual model of knowledge to action, and then go over different motor learning techniques. Finally, I will end with motivational strategies and promote adherence to some of these and other types of techniques. I will summarize, and then we will have questions and answers at the end. I do have a lot of material that I am excited to share with you today.

Knowledge and Use of Motor Learning Principles

- “Survey results confirm low EBP implementation in a U.S. sample of occupational therapists challenging the profession’s competency standards about using EBP for knowledge acquisition and translation to practice, critical reasoning, performance skills, and the vision of occupational therapy as an evidence-based profession” (Krueger et al., 2020)

- The Implementation of Evidence-Based Practice in Stroke Rehabilitation (Rowe et al., under review)

- “to determine reported knowledge and use of current adult stroke rehabilitation research by therapists in clinical practice”

- “Results indicate that knowledge of an intervention does not necessarily indicate its use in practice.”

Occupational therapists and healthcare workers have a lot of knowledge. Unfortunately, we do not always implement or use that knowledge in practice. A very recent survey by Krueger and colleagues found low evidence-based practice implementation in a sample of occupational therapists in the United States. I reiterated that survey and a recent one that is currently under review. In my study, we asked a large population of physical and occupational therapists about what kind of knowledge they had about stroke rehabilitation interventions and how much they felt like they were using that knowledge. The results indicate that knowledge of the intervention does not always indicate its use in practice. This is unfortunate, and there can be a lot of different reasons for that.

Theorists/Researchers Vs. Practitioners

One might be that researchers or theorists are not communicating very well with practitioners and vice versa. I discovered this several years ago when I was working at Emory in research. One of my jobs was to go out to different facilities and tell therapists and others about the type of research we were doing in hopes they would be interested and identify patients that they could refer to us to be research participants. I loved getting out in the community and telling therapists about what was going on. Frequently, the therapists would say that that they thought it was interesting but not very feasible. They felt that I was in the "ivory tower of research," and they were in the trenches. They felt that they did not have the time, resources, or money to implement the proposed interventions. I would hear that feedback from the therapist and take it back to the research lab. With this feedback, I would ask if the methods needed to be altered. I definitely saw a gap between research and clinical practice.

Another way I saw this was when working at Emory, we would have engineers from Georgia Tech come to our lab and bring us different technology that they had created. Often, these devices would be intricate with many bells and whistles. They would want to know how we could use it. Sometimes we could not use it due to one minor but fatal flaw. As an example, one of the engineers brought two blocks that connected. He said, "I can measure the rate and the grip/pinch strength needed to pull these two blocks apart." My question was, "Why would I want to measure that?" He said, "It is the type of grip that you would use when you open a water bottle spout." However, I showed him that I used a different grip/pinch. His face fell when he had the realization that he did not think about that. He had to go back to his lab and reconstruct things so that the grip was more functional and normal. Better communication would have saved a lot of time, energy, effort, and money.

This has come to be known as knowledge translation. There is definitely a gap in knowledge translation between research and practice. We need to find ways to close that gap and translate research findings that clinicians can understand and apply in their practice settings. Research often takes years. It has been known to take up to 17 years before research reaches its intended audience, and it can be even longer before it is widely accepted. This is a fact that is known in many different areas, not just occupational therapy.

Knowledge Translation

What Is It?

- Knowledge Translation (KT) is defined as...

- a dynamic and iterative process that includes exchange, synthesis, and application of research evidence to improve patient outcomes, provide effective services, and strengthen our health care system (CIHR, 2004)

- New lingo, old problem (↓EBP, practice gaps)

- An iterative strategy/process

- Multiple steps: knowledge creation, implementation, and use

- Why is it so sexy now? (researchers-clinicians collaborations- new role)

- a dynamic and iterative process that includes exchange, synthesis, and application of research evidence to improve patient outcomes, provide effective services, and strengthen our health care system (CIHR, 2004)

Knowledge translation is critical. It is a dynamic and iterative process and not a one-shot thing. It is not just going to one webinar, learning about something, and then instantly apply it. It involves an exchange, a synthesis, and an application of research evidence used to improve patient outcomes, services, or strengthen the healthcare system in general. It is new lingo for an old problem. The decreased use of evidence-based practice and the gap from research to practice have been around for a while. However, the term knowledge translation is relatively new, as is doing it with an iterative strategy and process involving multiple steps. It is a new role that I sort of fell into when I was at Emory. However, I found that I really liked being able to be that bridge between researchers and clinicians.

- Knowledge translation is a process of ensuring that new knowledge and products gained through research and development will ultimately be used to improve the lives of individuals with disabilities and further their participation in society.

- Knowledge translation is built upon and sustained by ongoing interactions, partnerships, and collaborations among various stakeholders, including researchers, practitioners, policy-makers, persons with disabilities, and others, in the production and use of such knowledge and product.

Knowledge translation is ensuring that new knowledge and products will ultimately be used. That is the goal of knowledge translation. It requires ongoing interactions, partnerships, collaborations with researchers, and practitioners, and other stakeholders.

What Is Included In The Process?

- Knowledge creation

- Original knowledge

- Synthesized knowledge

- Knowledge dissemination

- Knowledge use or implementation

- Evaluation of outcomes/impact

It involves creating knowledge, whether at the basic research level, to find out what the information is or synthesize current knowledge already out there. It then involves disseminating that knowledge. This might be done in different varied ways. It includes using or implementing the knowledge that is gained. Finally, it involves following that up with evaluations to ensure that what is being done has a positive outcome and provides an impact that can be sustained.

How Can We Effectively Bridge Knowledge/Practice Gaps?

- Use of conceptual models to design effective KT interventions

- solidated Framework of Implementation Research (Damschroder et al. 2009)

Just like we use MapQuest or our GPS-type systems to find our way around, you can use a conceptual model of knowledge translation to help map your path to make sure that you hit all the different needed components within that process.

Knowledge To Action Model

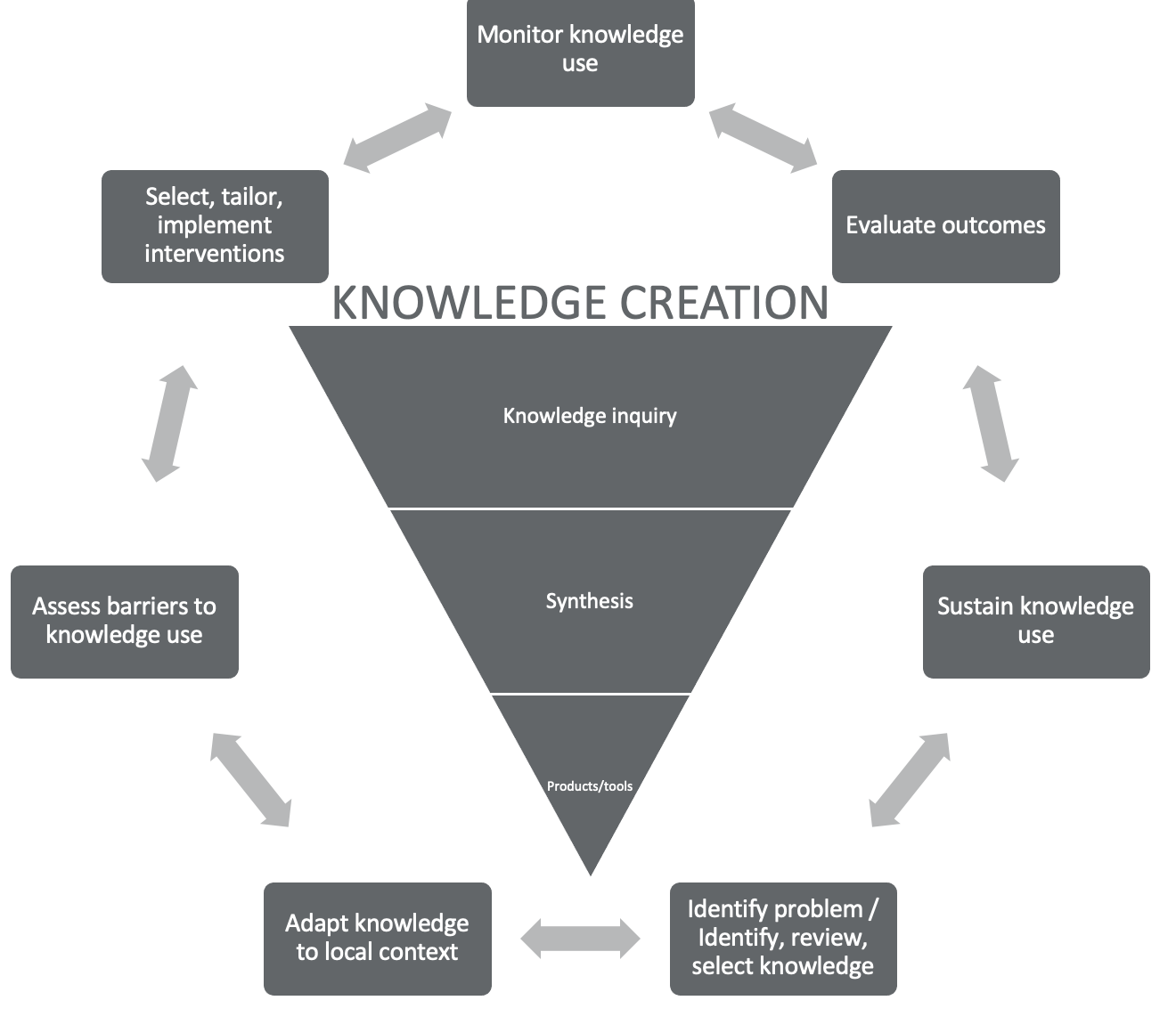

One commonly used conceptual model is called the Knowledge to Action Model in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Knowledge to Action Model.

Graham I, Logan J, Harrison M, Straus S, Tetroe J, Caswell W, & Robinson N. (2006). Lost in knowledge translation: Time for a map? Journal of Continuing Education in Health Professionals, 26(1): 13-24

This is the model that I am most familiar with, and I want to give you a quick example using it. You can begin in the middle of the circle with knowledge creation. We acquire knowledge through inquiry (research), synthesize research that has already been done, and then develop some type of product or tool that we want to implement and provide in our practice. The outer circle is the application or the translation of that knowledge into practice. Each place, facility, hospital, or organization needs to identify their problem and the knowledge they will use to help solve that problem or improve upon something they are currently doing. They need to adapt that knowledge to their context. As every place is different, you will have different adaptations of the knowledge to fit the different contexts.

You also need to assess the barriers and the facilitators to the use of that knowledge. Again, every context might be different and have different barriers and facilitators. A barrier is not always a lack of knowledge. In fact, it is often overstated that if we just teach people something, it will be done. Barriers may be things like resources. There may not be enough time to implement the intervention. A facility may lack the necessary equipment. It could be a state of mind as administrators may feel like they have always done something in a particular way. Why would we change?

You need to select and tailor the interventions that you feel are most appropriate to your specific context, but it does not end at just implementing. While implementation is great, you still need to monitor and evaluate the outcomes. Is it giving you good results? Is it producing things that you want it to produce? Can you sustain it? If it produces good outcomes, we certainly want to continue to use that or find ways to adapt and update it as needed over the years. Notice that the arrows in this application process go back and forth in Figure 1 as it is not a linear process.

Knowledge Translation Characteristics

- Interactive

- Multi-directional communication

- Interdisciplinary

- Multiple activities

- Non-linear process

- User and Context-specific

- Outcome/impact-oriented

It is interactive. You may have to go back to the drawing board and find new knowledge or adapt the intervention/tool differently. You might discover during the process that there are more barriers or more facilitators. It is a multi-directional process that requires a lot of communication, not just from OTs but from the whole interdisciplinary team. I want to reiterate that it is not just one shot. It may take multiple activities. For example, listening to this one webinar does not mean you will be able to go out and implement something with good results right away. The process is nonlinear and goes back and forth. It is also certainly context-specific. Ultimately, the goal is to have positive outcomes and be impact-oriented.

Who Is The Knowledge User?

- Defined as an individual who is likely to use knowledge generated through research to make informed decisions about health policies, programs, and/or practices

- Their level of engagement in the research process may vary in intensity/complexity and depends on the research's nature and information needs.

- Examples of knowledge users:

- Health care provider (physicians, nurses, rehabilitation therapists, etc.), health care administrator, policy/decision-maker, educator, community leader, or an individual in a health charity, patient group, private-sector organization, or media outlet

CIHR website: Knowledge Translation 2014

The knowledge user can be defined as anyone who makes informed decisions about healthcare policies, programs, or practices, such as your administration or coworkers. Your level of engagement with each knowledge user may vary depending on what area or stage they are in or how much they are working with the knowledge translation. A wide range of people can be defined as knowledge users.

Two Types Of KT In Research/Clinical Practice

- End of grant KT:

- Researcher shares study findings

- e.g., conference presentations, publications in peer-reviewed journals

- Scientific discoveries are commercialized

- e.g., patents

- Intensive dissemination activities tailored to a specific audience

- e.g., Workshops, summary briefings to stakeholders, interactive educational sessions with patients, practitioners, and/or policymakers, media engagement, knowledge brokers

- Researcher shares study findings

- Integrated KT (collaborative, action-oriented research)

- Stakeholders/knowledge users engaged in the entire research process

- Researchers and knowledge users work together to shape the research process and produce relevant research findings

CIHR website Knowledge Translation 2012

Knowledge translation, relating research into practice, can be thought of in two different ways frequently. End of grant knowledge translation is frequently seen in Canada. For a lot of the Canadian grants, they actually require a section of the grant to identify and specify how knowledge of this study grant, whatever it is, is going to be translated into practice. It's a very definite part that has to be identified and specifically spelled out. That's becoming more widely known in the United States as well. However, in general, you can still use knowledge translation, and you're encouraged to do knowledge translation by simply working together between researchers and those knowledge users in bridging that gap.

Important Things to Remember

- KT is not an event, but a process with many components

- KT encompasses all steps between the creation of new knowledge and its application to yield beneficial outcomes for society

- All components must be taken into consideration to optimally achieve the end result of desirable outcomes/impact

- KT is underpinned by effective exchanges between researchers who create new knowledge and knowledge users/stakeholders

- There needs to be a philosophical change of how research is viewed, as well as practical changes to implement this alternate way of thinking in all components

- To ensure the best possible outcomes, it is advantageous to use a systematic approach rather than a piecemeal approach

Here are some important things to remember about knowledge translation. It is a process with many components. It has a lot of steps between the creation of new knowledge and its actual application. You should consider all those steps when you are implementing knowledge translation. It requires effective exchanges between researchers and knowledge users. As I told you, communication between the therapists and the engineers would have saved a lot of time, energy, effort, and money.

Sometimes, it needs to be a philosophical change of how research is viewed. I will be honest with you. When I would go out to different hospitals and facilities in the Atlanta area to tell them about our research, it was not uncommon that there would be one or two people (therapists or others) that would say, "Oh God, here's that woman from Emory coming to talk about research again." You sometimes need to change that philosophical view about research. How can you implement practical changes to switch that thinking? Using a systematic approach following one of these conceptual models can be helpful. We need to use KT to increase the relevance of the knowledge that is produced.

Why KT?

- Increased relevance of knowledge produced

- Increased likelihood that knowledge can/will be used

- Increased public benefit

- Optimal return on research and development investment using public funds

Knowledge and research are great, but it is not doing us much good if it is not being used. We want to increase the relevance of the knowledge to increase the likelihood of it being used. Ultimately, we want to get a good return on our research and development investments and public funds.

Theory Development and Application Assumptions

- Both responsibilities of the profession

- The gap is partly a function of how knowledge is developed and organized

- The gap can be narrowed or eliminated if there is a dialogue between the explanation and practical problem solving

Theorists/researchers and clinical practitioners need to have better communication to work together for knowledge translation because it is our responsibility to the profession to contribute both to research and knowledge inquiry and clinical practice. Again, we need to try to bridge that gap.

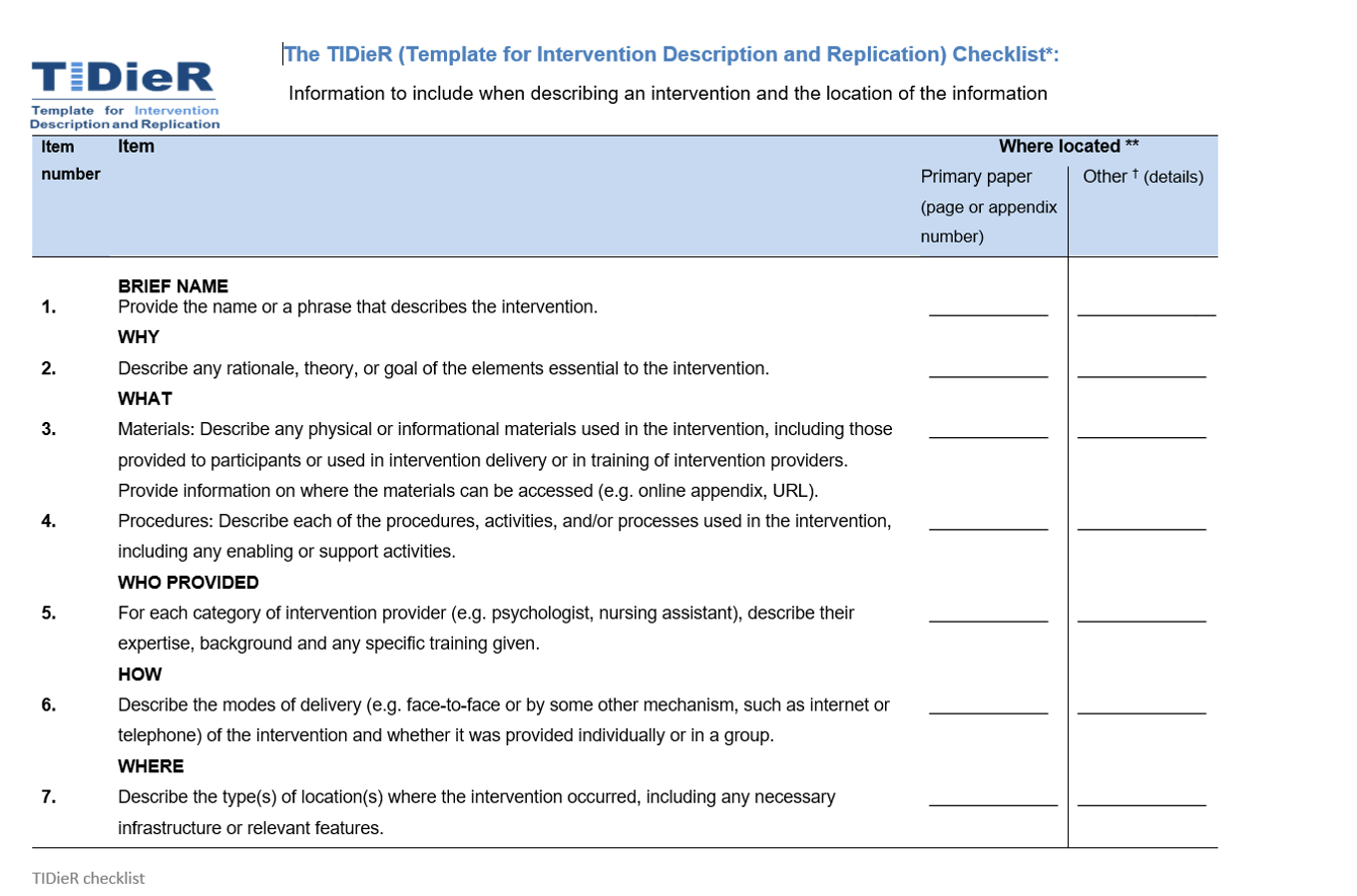

The TIDieR (Template for Intervention Description and Replication) Checklist for the Implementation of Motor Learning Principles

(Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, et al., 2016. The checklist and the guide are free to download from the Equator Network website: https://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/tidier/)

One resource to bridge that gap is the TIDieR Checklist (Figures 2 and 3). It is a concise way to identify what the intervention is and how you want to translate that into your practice.

Figure 2. The TIDieR Checklist, page 1.

Figure 3. The TIDieR Checklist, page 2.

This checklist asks some specific questions about the resources you found and how to define and report the intervention. It prompts you to give detailed descriptions of the intervention, whether it is for replication and research or more effective use in the clinic. You can download it for free, and it serves as a guide for knowledge translation. What is the operational definition? How do you do the intervention? Otherwise, everybody might be thinking they are doing something correctly, but they may not be.

Motor Learning Techniques: Task-Oriented/Specific Training, Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy, Cognitive Orientation to Occupational Performance (CO-OP)

- “Task-oriented training produced statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvements of paretic upper extremity functional performance in patients with subacute stroke. These beneficial effects were observed after 2 weeks (10 hours) of training.” (Thant, et al., 2019)

- However – “In the TOT program, each participant practiced 3 out of 6 selected functional tasks according to his/her preference. Selected tasks were drinking water from a glass, lifting a glass of water to a level of 90° shoulder flexion with an extended elbow, moving 5 crystals from the table to a box, wiping the table with a towel with the elbow extended, grasping and releasing a 6 cm diameter tennis ball, and combing their hair.” (Thant, et al., 2019)

- What is Task-Oriented Training? A Scoping Review (Rowe, et al., under review)

- Task-oriented training (TOT) is an effective stroke rehabilitation intervention with significant evidence-based research that supports its effectiveness. However, previous studies do not consistently define TOT. With healthcare discoveries taking 17 years to be implemented into practice, a consistent definition of TOT will aid the knowledge translation from research into practice.

- A scoping review helped determine a comprehensive definition of TOT from the way it has been defined and used in the literature.

- Commonly found words used to define TOT included: repetitive, functional, task practice, task-specific, task-oriented, intensity, and client-centered. Other important components were found that align TOT with the principles of neuroplasticity were meaningful, progressive, graded, variable, and feedback.

- These results lead to the definition of:

- Task-oriented training is an effective stroke rehabilitation intervention that focuses on the use of the client-centered, repetitive practice of activities that are of high intensity and meaningful to the client.

One of the motor learning techniques that I will talk about is task-oriented or task-specific training which in the literature is very effective. However, when you start reading about all of the studies, the authors define task-oriented training differently. They may have had some common components, yet everyone's operational definition was a little bit different. It usually includes repetition, intensity, and some type of functional activity; however, as we know, functional activity can be defined differently.

A group of students and I did a scoping review to look at the different literature to develop an operational definition for task-oriented training. We wanted to help researchers to be able to replicate studies on task-oriented training and help clinical practice in identifying what it is and the different components. We found some commonly used words that were included for task-oriented training. And ultimately, our definition was that task-oriented training is an effective stroke rehabilitation intervention that focuses on the use of the client-centered repetitive practice of high intensity and meaningful activities to the client.

Similar to this, the TIDieR Checklist is a nice resource that you can use to help first identify and synthesize what it is you want to translate.

Let's talk about some specific motor learning and stroke rehabilitation interventions, especially for improvements in upper extremity and movement function. To do that, I want to start by asking you to personalize it a bit.

What Would You Miss Most If You Lost Function in Your Dominant Arm and Hand?

Think about what you would miss most if you had decreased movement and function in your dominant arm and hand? Think about a specific activity that is really important and meaningful to you that you would have trouble doing. Would it be feeding yourself? How about bathing or washing your hair? Holding a child or hugging a loved one are both important. Perhaps, you would miss driving, typing, writing, playing a game, cooking, etc. Whatever it is, think about that. The types of interventions I am going to talk about pertain most to hemiparesis after stroke.

Hemiparesis After Stroke

- “learned non-use” (Taub et al., 1993) - Reluctance or unwillingness to use the “involved” limb prompted by encouragement from clinicians and family to use the “uninvolved” limb, resulting in learning how not to use the involved limb. A learned suppression of movement.

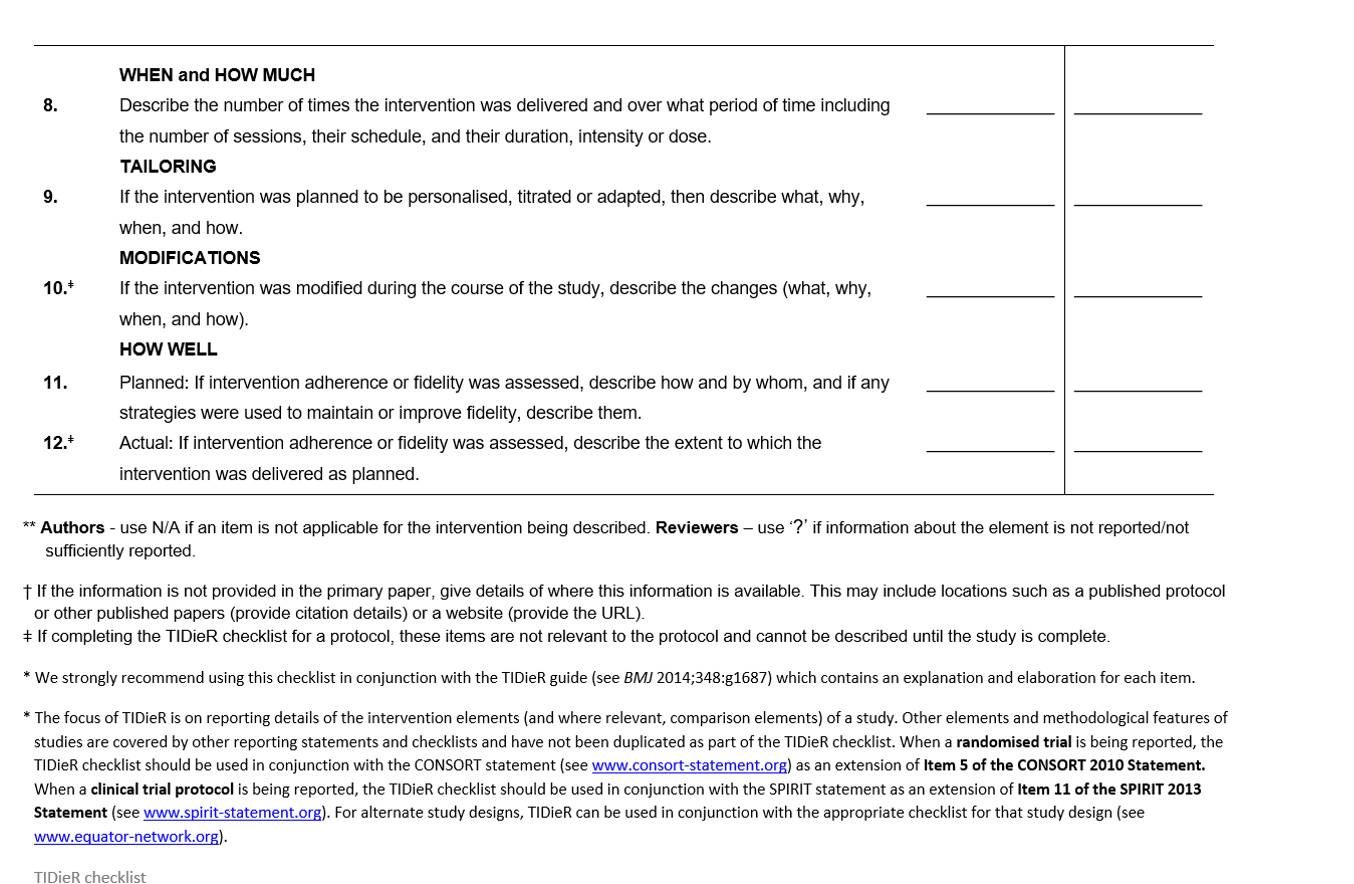

When people have decreased movement, they may still have some movement in their arm and hand, but it often does not move. It is not as efficient or strong. It also can be slow and clumsy. What tends to happen is the phenomenon of learned non-use. If you have ever cared for a small child, you suddenly get really good with that other arm. An exaggerated example is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Multitasking and using both arms for activity.

Somebody with a stroke with an arm that is weaker and less efficient gets really good at using their other arm. They tend to neglect or stop using the affected arm as much, even though they may have some movement. Instead, they get better with using the less affected arm. Again, this phenomenon has been coined "learned non-use" by Edward Taub. It is a learned suppression of movement.

How can we either reverse or prevent the phenomenon of learned non-use? When I was in OT school, I remember being taught that once somebody has a stroke or neurological damage to the brain, that part of the brain was gone, and they needed to learn how to compensate. That was the basic gist. Since then, we have learned that this is not really true and that the brain is actually very plastic and changeable.

Neuroplasticity

Nudo, R. J., Plautz, E. J., & Frost, A. B. (2001). Role of adaptive plasticity in recovery of function after damage to motor cortex. Muscle Nerve, 24: 1000-10019.

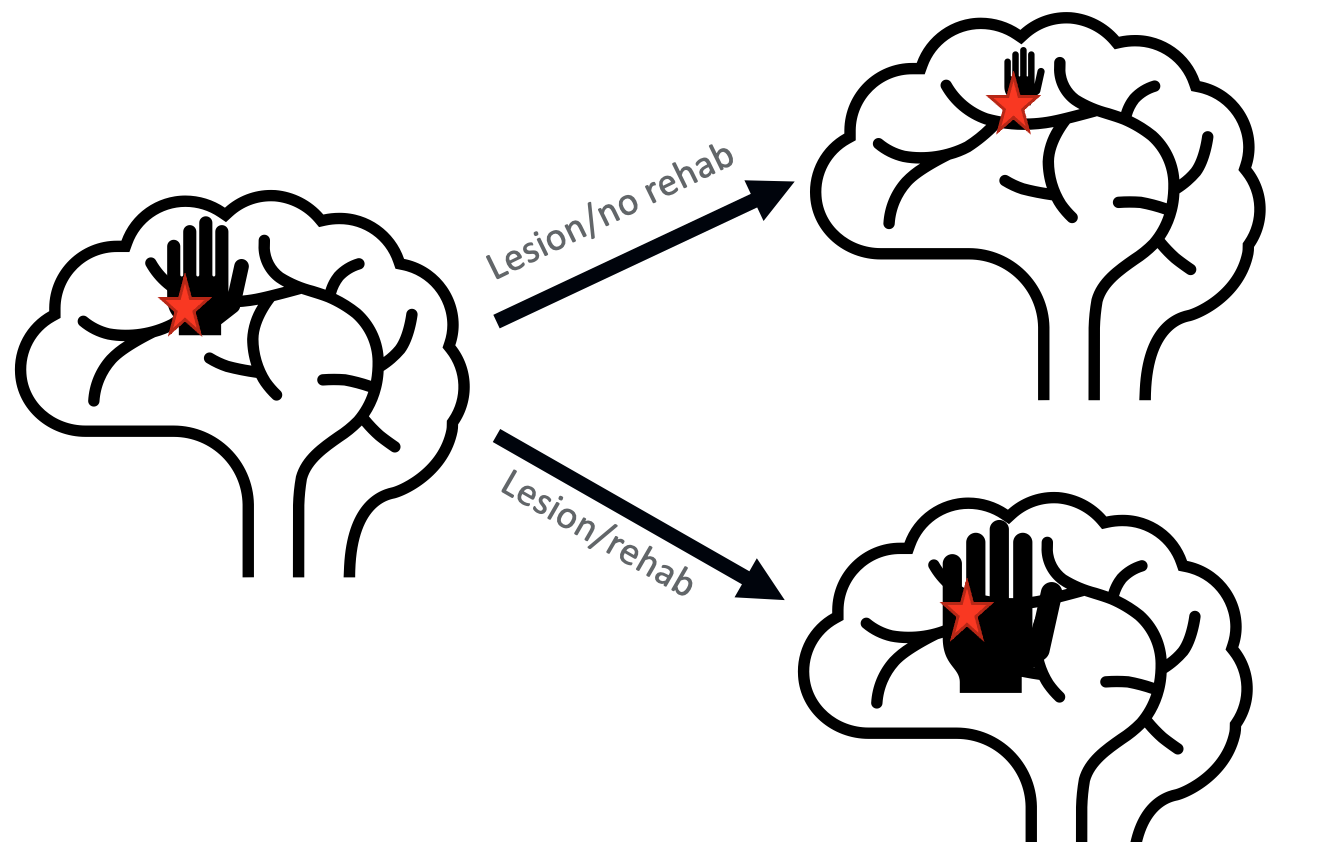

In 2021, Randy Nudo completed a fascinating study with monkeys. Figure 5 shows a schematic as an overview.

Figure 5. Schemata of monkey brains showing neuroplasticity.

On the left is a monkey brain, where he mapped out the area of the brain that controlled hand movement. He induced a neurological incidence (or a stroke) in part of the area that controlled one of the hands of the monkeys (highlighted with the black hand/red star). For half of the monkeys, he put them back in their environment with no type of rehab. They had an arm and a hand that was not moving as well. After a period of time, he rescanned their brains and found that that area of the brain that controls hand movement had shrunk. The stroke was still there, but in addition, the monkey was not using that hand as much, but the cells in that area had atrophied. The other half of the monkeys were given some type of rehab. After a period of time, their brains were scanned, and the area that controlled the movement of the hand increased. Again, they still had the stroke in this area with damage to the tissue. However, other parts of the brain that previously were not controlling the hand movement were able to take over and allow the monkey to use that hand more. This was biological proof that the brain is plastic and capable of change. Other areas of the brain can take over for the damaged components.

How Do We Implement That In Our Rehab Practice?

Kleim, & Jones, (2008). Principles of experience-dependent neural plasticity: Implications for rehabilitation after brain damage. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 51, S225–S239.

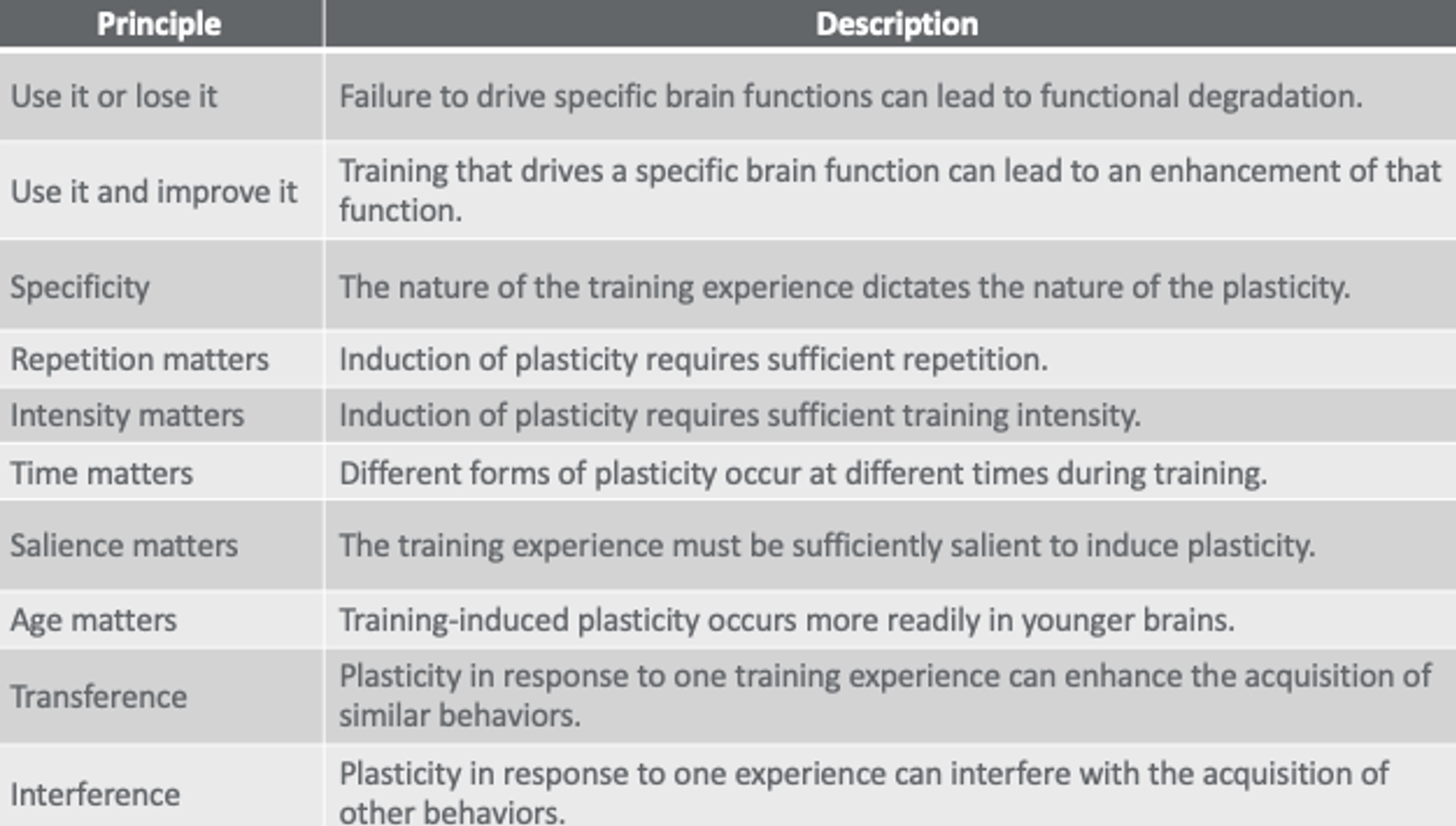

Kleim and Jones wrote a great article in 2008 that identified 10 principles of experience-dependent neuroplasticity. These principles (Figure 6) can relate directly to our rehab practice.

Figure 6. Chart showing 10 principles of neuroplasticity.

There are things like "use it or lose it "and "use it and improve it." Much like the phenomenon of learned non-use, this leads us to the intervention of constraint-induced movement therapy. If you have a weaker arm and hand and do not use it, you will lose function. However, if you force yourself to use it, it will improve and get better. Specificity means the nature of the training is essential. We need to have training that is complex and engaging to the client. We do not want rehab to be dull and boring. Repetition and intensity matter. We hear that a lot. The more you do it, the better you get at it. We want to encourage lots of repetition and intensity—time matters. We cannot always affect or change this, but the brain tends to be more plastic immediately or soon after a neurological incident rather than later on. We want to start therapy right after the incident. This does not mean that the brain stops being plastic after a certain amount of time. The brain can remain plastic forever, but you may not see as much plasticity later on.

Salience matters. Here is where I feel like science has finally caught up with OT. Salience means meaningfulness, purposefulness, and the importance of the tasks. Having a client do something that they are really interested in and want to do will increase neuroplasticity. Age also matters. Again, we cannot really control this, but it is good to know that, in general, younger brains tend to be more plastic than older brains. However, just like with time matters, there is not a cutoff. There is no certain age where the brain stops being plastic.

Transference means that we can use all the tricks of our trade. It is good to use different interventions and environments to encourage neuroplasticity and for generalization. This is not doing the same thing in the same place all the time. Interference means that we want to use lots of different things, but we do not want to use competing interventions. For example, if I am using constraint-induced movement therapy and encouraging a person to use their weaker arm and hand, but I am also teaching them hemi dressing techniques with their less affected arm and hand, this would be interference. These are interventions that do not work well together. Some specific interventions and ways that we can implement those principles into practice are what I would like to cover next. One of them is constraint-induced movement therapy.

Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy

- The systematic application of shaping and repetitive use strategies without employing the contra-lateral limb over a defined time interval improves (meaningful) functional use of an impaired limb.

Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy (CIMT) is the systematic application of shaping and repetitive use strategies with employing the contralateral limb over a defined interval to improve meaningful functional use of the impaired limb.

Evidence-Based Practice/EXCITE Trial

- Effect of Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy on Upper Extremity Function 3 to 9 Months After Stroke

(Winstein et al., 2003; Wolf et al., 2006; Wolf et al., 2008)

CIMT has been studied widely, mainly in the EXCITE Trial, which stands for Extremity Constraint-Induced Therapy Evaluation. This was a large national centered randomized clinical trial that looked at constraint-induced movement therapy. Since then, multiple studies have been completed looking at modified versions and forms of constraint-induced movement therapy. I think mostly these modified versions were to implement this treatment into clinical practice and bridge that gap. "We found out it works. Now, let's figure out how we can actually use it and implement it into practice."

Therapeutic Aspects of CI Movement Therapy

- Restraint of less involved UE

- Constraint of more involved UE

- Repetitive, task-oriented training

- Adaptive task practice (shaping)

- Repetitive task practice

- Adherence-enhancing behavioral strategies (“transfer package”)

- Behavior contract

- Home diary

- Home exercises

In a nutshell, CIMT involves four different aspects: restraint of the less involved upper extremity. A mitt was used in the EXCITE Trial to keep the person from physically using their arm. You can use any type of mitt. You can use whatever to keep the person from using their less involved upper extremity. It forces them to use the more involved upper extremity. It also involves increasing the use of the more involved upper extremity through repetitive task-oriented training. This is with lots of repetitions and intensity. The fourth component that is frequently forgotten is the adherence-enhancing behavioral strategies or the transfer package. These strategies pertain to telling the client why you are doing this so that they understand that you are not just trying to frustrate them. This is explaining the concept of learned non-use and how you are trying to reverse or prevent it. This is also having them do strategies outside of the therapy session in their home environment. This is really key.

What is the Most Important Part?

- RTP (Repetitive Task Practice)

- Continuous activity (e.g., eating, grooming, writing)

- ATP (Adaptive Task Practice) “shaping”

- Coaching

- Positive reinforcement for effort

- Plotting task performance (Ex. 30-sec trials x 10)

- Grading of tasks

- “How difficult should the task be?”

- The level of difficulty should be slightly more challenging than “easy.”

- “How difficult should the task be?”

What is the most important point of CIMT? I have heard many people say that it is the mitt. "As long as I have the mitt, I am doing constraint-induced movement therapy." Steve Wolf wrote a beautiful article, the primary investigator of the EXCITE Trial called "Are We Too Smitten with the Mitten?" I think this article sums it up really nicely. Sometimes, we get too smitten with the mitten, and in reality, it is not the mitten and restraining the unaffected arm that is the most important part. The most important part of constraint-induced movement therapy is the repetitive task practice or the adaptive task practice, where we grade and shape the tasks so that the client has the "just-right" challenge. The grading of tasks is also a key part of CIMT. How difficult should the task be? The task should be slightly more challenging than easy. You do not want the task to be too simple to become bored or too hard, and the client gets frustrated. In both scenarios, the client will want to give up. You want to keep the task at that just-right challenge.

ICARE Trial

Winstein C, Wolf S, Dromerick A, et al. Interdisciplinary comprehensive arm rehabilitation evaluation (ICARE): A randomized controlled trial protocol. BMC Neurology. 2013;13.

Winstein CJ, Wolf SL, Dromerick AW, et al. Effect of a task-oriented rehabilitation program on upper extremity recovery following motor stroke the ICARE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(6):571-581.

The ICARE Trial (Interdisciplinary Comprehensive Arm Rehabilitation and Evaluation) came after the EXCITE study. It was the next large national randomized clinical trial. It looked at task-oriented training using many components from experience-dependent neuroplasticity and some components from constraint-induced movement therapy. This advanced the field even more. It looked at the intervention of task-specific training as this neuro facilitation approach has evolved.

Motor Learning and Task-Oriented/Specific Approach

- Neuro-facilitation approaches have evolved to include function, not just suppression of reflex.

- Task-oriented or motor learning approach

- Developed from newer theories of motor control

- Treatment based on functional tasks

- Learn by solving problems

- Must be able to adapt to changes in the environment

A task-oriented approach looks at the learning of movement and not just the suppression of reflexes. It is also focused on treatment based on functional tasks. This is a key part. The biggest change is having the client be the active problem solver and learning how to adapt to changes within their environment.

Task-Oriented Training

- The active, repetitive practice of functional activities to learn or relearn a motor skill.

- Repeated, challenging practice of functional, goal-oriented activities

- Used for restoring or remediating upper extremity motor control

Task-oriented training is the active repetitive practice of functional activities. It involves repeated, challenging practice of these activities for use in restoring or remediating extremity motor control.

Principles of Task-Specific Training

- The practice of a movement results in an improvement in that movement

- (Use it and improve it)

- Large amounts of practice are required to truly master a motor skill. The ideal dose of practice is unknown.

- (Repetition and Intensity)

- Learning requires solving the motor problem, not the rote repetition of overlearned tasks.

- Learning does not occur in the absence of feedback.

- Intrinsic feedback is optimal for promoting self-learning and generalization.

- (Specificity)

You can overlay those principles of neuroplasticity with the principles of task-specific or task-oriented training. The practice of a movement results in the improvement of that movement (Use it and improve it). Large amounts of practice are required to truly master a motor skill (Repetition and intensity). Learning requires solving the motor problem, not a rote repetition of overlearned tasks. Learning does not occur in the absence of feedback, and intrinsic feedback tends to be more optimal for self-learning and generalization. The last three principles are related to the specificity and especially to the active problem-solving component that I referred to.

- Optimal learning occurs with high levels of motivation and engagement.

- (Salience)

- Variable practice conditions are optimal for learning and generalization.

- (Transference)

- Within-session, massed practice promotes learning better than within-session distributed practice.

- (Repetition and Intensity)

- The practice of a whole task results in better learning than the practice of parts of the task, unless the task can be broken down into clearly separable components.

- (Specificity, Transference, and Interference)

Task-oriented training also involves optimal learning occurs with high levels of motivation and engagement. This is salience. Variable practice conditions are optimal for transference. The use of repetition and intensity within a session is better than distributed practice (but not always practical). And finally, practicing a whole task can result in better learning than the practice of parts of the task unless you are sure that the client understands why you are breaking down the task into different components and how that relates to specificity, transference, and interference. All of these components can be utilized within task-oriented training.

Task-Oriented Training and Evaluation at Home (TOTE Home)-Veronica T. Rowe, PhD, OTR/L

Rowe, V. T., & Neville M. (2018). Task-oriented training and evaluation at home. OTJR, 38(1):46-55.

Rowe, V.T., & Neville M. (2018). Client perceptions of task-oriented training at home: "I forgot I was sick." OTJR, 38(3):190–195.

Rowe, V.T., & Neville M. (2019). The feasibility of conducting task-oriented training at home for patients with stroke. OJOT, 7(1).

Rowe, V.T., & Neville M. (2020). Task-oriented training at home (TOTE home): A case study. Annals of International OT, 3(1):45-52.

I took it one step further and took the protocol used in the ICARE Trial called ASAP, a task-oriented training type of method, and implemented it in a home setting. I called it Task-Oriented Training and Evaluation at Home or TOTE Home. I found a lot of good results and learned a lot from this. Doing task-oriented training in the home was easier. We were doing tasks that the client automatically found important and meaningful. We used their physical equipment, like their spatula in the kitchen, their rake in the backyard, or their dust cloth in the living room. I learned a lot and found that active problem-solving is a really key component.

Cognitive Orientation to Daily Occupational Performance (CO-OP)

(Dawson, McEwen, Polatajko, 2017)

- Client-chosen goals

- Dynamic performance analysis

- Cognitive use strategy

- Guided discovery

- Enabling principles

- Parent/significant other involvement

- Intervention format

That active problem-solving component is one component that can also be seen within the Cognitive Orientation to Daily Occupational Performance or CO-OP Model, along with several other components. I am still learning about the CO-OP Model, which was originally developed for pediatric patients with cognitive problems. Since then, it has been expanded and is used frequently for adults with cognitive deficits. It has a lot of components that mesh really well with task-oriented training. They kind of go hand in hand and using them both can really produce better results. I wanted to touch on a few of these components within the CO-OP Model.

Client Chosen Goals

- Daily logs

- Activity Card Sort

- Canadian Occupational Performance Measure

- Guided process

- Measurable goals

- Can be used as an outcome

The first one is client-chosen goals. Having the client choose the goals that are meaningful and important to them is really key both in the CO-OP and in task-oriented training.

Dynamic Performance Analysis

- Structure observation of the client-chosen goals in context

- Fit between person, environment, and occupation

- Environmental supports/hindrances

- Objectives

- Identify performance problems

- Identify and test potential strategies

- Therapist

- Need a baseline knowledge of how to perform skill

- Need to identify performance breakdown to help guided discovery of domain-specific strategies

- Participant

- Help build a skill set of complete dynamic performance analysis independently

The dynamic performance analysis that is utilized in CO-OP is also used in task-oriented training. This is analysis not just by the therapist but also teaches the client how to analyze and grade a task to keep it at a "just-right" challenge. This way, they can use task analysis on different things that might come up in their lives.

Guided Discovery

- Low: Discovery learning

- “Figure it out on your own!” (Trial and error learning)

- Mid: Guided discovery

- “Try to figure it out on your own, but I will help you if you get stuck.”

- High: Explicit instruction

- “Just listen! I’ll tell you what to do!”

This guided discovery also goes right along with active problem-solving. It is a mind switch for the therapist. Instead of the therapist leading and prescribing everything done in therapy, it is therapy now being client-led.

- One thing at a time

- Ask, don't tell (verbal)

- Coach, don't adjust

- Make it obvious

- Enabling principles

- Facilitating

- Guiding

- Coaching

- Educating

- Promoting

- Listening

- Reflecting

- Encouraging

- Collaborating

- Significant other involvement

- Challenging in adult populations

- Primary role

- Support in skill acquisition

- Help facilitate transfer/generalization

- Enabling principles

The client chooses the task and goals, and the therapist serves as the guide. Instead of telling them what to do, the therapist guides their discovery to help them learn how to do things. I liken it to the analogy of "Give a man a fish, and he eats for a day." I can instruct a client on how to do one task. Instead, if I guide their discovery and teach them the motor learning and active problem-solving components, they can take that skill and learn other things when I am not around. Essentially, using the same metaphor, I am "teaching them to fish so that they can eat for a lifetime." The CO-OP, as well as the task-oriented training, involves the guided discovery of asking, not telling the client, getting them to come up with the next appropriate thing to do, and guiding/coaching/facilitating/educating/promoting/listening/reflecting/encouraging/collaborating as needed.

Another key component of the CO-OP involves significant others. It can be challenging in the adult population, but it is definitely something that we need to do. We need to look at their support and the people that are around them to get them on board with what we are doing as well. We have all probably seen those family members who were wonderful. They are loving and caring, but they are also doing everything for the client. However, if we want them to advance, we need to teach, coach, and guide the significant other in these methods and processes.

Motivational Strategies for Stroke Rehabilitation

You may be thinking that you need to look further into those techniques. I am not saying that these are the "be all end all." I might use a knowledge translation framework to help implement this evidence-based practice into your own practice or refine what you are already doing. Maybe, you are doing a part of one of these strategies but need some more research to improve upon it. One of the things you will want to do is figure out what the facilitators and barriers are. One of the fairly common strategies across a wide variety of stroke rehabilitation facilities is using motivational strategies to get a client to engage in stroke rehabilitation.

I found an article by Oyake that was done last year where he conducted a Delphi study. This is where you gather a group of experts and get opinions on things. Specifically, he asked these experts, "What are some motivational strategies that therapists should use for stroke rehabilitation?" As you go through the above list (ordered from most important to least important), according to the experts that he polled, you will see that many of them fit right along with task-oriented training and neuroplasticity principles.

- Control of task difficulty

- Goal setting

- Providing feedback regarding the results of the practice

- Goal-oriented practice

- Praise

- Providing a suitable rehabilitation environment

- Practice related to the patient’s experience

- Allowing the patient to use a newly acquired skill

- Sharing the criteria for evaluation

- Application of patient preferences to practice tasks

- Specifying the amount of practice required

- Explaining the necessity of a practice

- Respect for self-determination

- Recommending that family members are present during rehabilitation

- Active listening

- Providing variations of the programs

- Having an enjoyable conversation with the patient

- Engage in practice with the patient

- Providing the patient opportunities to identify possible treatments

- Motivational interviewing

- Using progress-confirming tools

- Providing medical information

- Providing practice with game properties

(Oyake et al., 2020)

You want the person to take control of the task difficulty, set their own goals, and provide feedback regarding the practice results. This is not specifically how to do it but the results of the goal-oriented practice. You also want them to choose the whole task and not the components of it. It is important to give appropriate praise and provide the appropriate environment, relating the patient's experience to their practice. We want to allow the patient to choose newly acquired skills. You should share your criteria for the evaluation, applying them to the patient's preferences. You should then specify the amount of practice required. I could continue, but I think you can see how it is really a shift away from therapists doing something to the patient. This is letting the patient be the leader with the therapy and guiding them, coaching them, and educating them along the way. This is going to increase motivation.

- Importance of each type of information when selecting motivational strategies

- Cognitive function

- Human environment

- Personality

- Patient’s reaction to a presented motivational strategy

- Social environment

- Severity of activity limitations

- Physical function

- Comorbidities

- Diagnosis

- Severity of participation restrictions

- Demographic characteristics

Another component of the knowledge translation process, along with identifying those barriers and facilitators, is adapting whatever knowledge and intervention you are translating into your practice for your specific setting and context. For example, you may need to look at your client's cognitive function when selecting these motivational strategies. You may also need to look at their personalities or their environments. You need to consider all of this, and one facility may do things slightly differently than another. You have to adapt the intervention that is effective to your own facility and context.

Another thing that goes along with motivation is adherence. Miller surveyed to see what are some reasons.

- Why don’t patients adhere to motor learning techniques?

- “Patient adherence with home exercise programs(HEP) after discharge from rehabilitation is less than ideal. Rehabilitation therapists need to be able to identify and help patients manage barriers to HEP adherence to promote management of residual deficits.” Miller et al., 2017

- Reasons for non-adherence

- Not enough time

- Don’t know what exercise to do

- Exercise is too hard

- Exercise not helpful

- Afraid of getting hurt while exercising

- No one to exercise with me

- No place to exercise

- Exercise is painful

- Exercise is boring

- Afraid of falling while exercising

- Doing different exercises than the ones given by the therapist

There are many reasons for non-adherence like not enough time, not knowing what to do, exercise is hard, "it's not helpful," etc. I kind of agree with a lot of those. It can also be boring. How can we overcome this? Perhaps we can take some cues from task-oriented training and make the tasks more meaningful. Instead of calling them exercise, call them functional tasks. Incorporate the exercise within a function and identify what those barriers might be. If clients are citing these things for non-adherence of a home exercise program, this may be a good way to start. Focus on how you could reverse that.

- How to promote adherence to motor learning techniques

- “Most commonly reported strategies to support home practice were the use of technology, personalization, and written directions.” Donoso-Brown et al., 2020

- Home program features

- Use of technology

- Individualization

- Written directions

- Phone check-ins

- In-person check-ins

- Caregivers

- Feedback from a device

- Instructions to progress clearly provided

- Photo directions

- Behavioral contracts

- Video

- Clear incorporation of goal setting

Elena Donoso-Brown has done a lot of work with adherence. Once we identify why people are not adhering and doing those exercise programs, how can we promote adherence and motivation to do these techniques to continue with rehabilitation? The most commonly reported strategies for home practice were the use of technology to serve as both reminders or as memory aids to do it, as well as personalization. We also want to individualize how the person does it. Giving the same handout to every single person may not be good enough. We may need to personalize it differently. We need to provide written directions. Even though we live in a technology world, not everybody is tech-savvy. Having those hard copy written directions may be really important. She also found other things like phone or in-person check-ins to be helpful. She also thought caregivers and feedback from a device also promoted adherence. Many people wear a device like an Apple Watch or a Fitbit. Other things rounding out the list are giving clear instructions, photo directions, a behavioral contract (that was used in constraint-induced movement therapy, video, and clear incorporation of goal setting. These are all ways the may help to overcome non-adherence or decreased motivation.

Summary

- Knowledge translation strategies to implement evidence-based neurorehabilitation research into clinical practice.

- Motor learning techniques for neurorehabilitation practice to facilitate occupational performance and participation – CIMT, TOT, CO-OP.

- Improving motivation and adherence of evidence-based practice.

In summary, I hope you found this helpful in learning about knowledge translation strategies to implement evidence-based neurorehabilitation research into clinical practice. It is a process. You can use a conceptual model, like the Knowledge to Action Model, to implement evidence-based practice, even if it is non-neurorehabilitation. If your population is something else, you can use that to help either implement new things or improve upon what you are currently doing. I hope I have given you an overview of constraint-induced movement therapy, task-oriented training, and the CO-OP Model, and how they all really fit well together. It is not one specific protocol that you have to follow. You can adapt it to your environment and your facility. Lastly, I hope that I have shown you ways that you can start to overcome barriers such as lack of motivation or lack of adherence to rehabilitation through some evidence-based literature.

References

References are included in the handout. If you think of a question later, I would love to hear from you.

Questions and Answers

What are some instances when task-oriented training would be inappropriate with children with significant neurological disorders?

I have not done much work with pediatrics, so I am not the expert to answer that. I can tell you, though, that task-oriented training can be adapted to any population or any type of person. I like it because it is not a specific protocol that has exact steps that you have to follow. You can adapt it. You may find that some components are more important for some clients than others, which is okay. The key components are the use of functional tasks, repetition, intensity, and active problem-solving. Also, you want the client to use their affected side as much as possible within functional tasks.

Could you review again how a practitioner who is not involved in research utilizes the TIDieR in daily practice?

The TIDieR is just a resource that I found and thought I would share. The TIDieR is a way to help you operationally define the intervention or the activity that you want to try to implement or translate into your practice. For example, if you decided to try task-oriented training, you could start with the TIDieR or something similar to help you identify what components were needed. Then, you could take that to your coworkers and administration.

Do you know how much it costs to be stroke certified?

I am assuming you mean AOTA's specialty certification. I do not know that off the top of my head, and it is not a specific stroke certification. You can gain a specialty certification within physical rehab, which includes stroke. I would refer you to the AOTA website for that. The beautiful thing, and again why I really like task-oriented training, constraint-induced movement therapy, and the CO-OP Model, is that you do not have to have a certification. You do not have to go to a course and prove that you know how to do it. You can learn about it on your own.

Is mirroring a way to facilitate movement in the affected side?

There have been studies looking at mirror therapy, as well as action observation. In most of the studies, they found this to work well for lower functioning clients that do not have as much movement and cannot participate well in constraint-induced movement therapy or task-oriented training because they do not have much movement in their arms/hands. They can still utilize that mirror therapy where they are looking at an image of their less impaired or stronger arm and hand and trying to trick the brain into thinking it is their weaker arm and hand. The same motor neurons work with action observation, and this can be a precursor. This is not all I would do in therapy, but it has been found that these types of interventions are great primers for other interventions.

When using CIMT, is there a specific patient that benefits more, for example, flaccid upper extremity versus upper extremity with some movement?

Excellent question. I will be the first to say that constraint-induced movement therapy is not appropriate for every type of client as we do have a lot of good efficacious results from it. It is most appropriate for the client with mild to moderate impairments in their movement. The specific inclusion criteria in the EXCITE Trial was that the patient had at least 15 degrees of wrist extension and movement in at least the thumb and two other fingers. For research, they have to really specify what the inclusion criteria are. In general, though, I would say it is appropriate to use for somebody that has some movement in their arm and hand. The reason for that is that when you put the mitt or the restraint on the other hand, and you ask them to live like that even for an hour or two, they have no movement at all. They will go crazy in about five seconds. It is really not appropriate until they have some functional movement. You can see if they can pick up a washcloth off a table and drop it or bring food to their mouth. This will give you an idea of their movement.

I'm a GSU OT alum. Glad I registered for your class. Currently, I work in a growing neuro ICU at a local hospital. Do you have any experience using these models in the acute care setting? How do you overcome those barriers of little resources?

This is another great question. I have used it in acute care, and I have done mo