Overview

- Overview of COVID-19

- Caseload Management

- Hospital-Acquired Deficits

- Outcome Measures

- Evidence-Based OT Interventions

- Case Studies

- Q&A

Julia: Thank you for having us. To preface this, we are not going to get too deep into the epidemiology or physiology of the disease because science is so quickly evolving around this novel condition.

Coronavirus-19 Disease

Description

- Virus: Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS- Cov 2)

- Per WHO guidelines:

- Contact/droplet precautions except during aerosolizing procedures

- Examples of airborne precautions:

- Tracheostomy

- Intubation

- CPR

- High flow O2

(WHO, 2020)

First of all, the virus is called Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 or SARS-CoV-2. The analogy can be used for HIV to AIDS, HIV being the virus, and AIDS is the disease process. SARS-CoV-2 is the actual virus where coronavirus or COVID-19 is the disease process that happens because of this virus. In a lot of the literature, you may see SARS-CoV-2 being listed, and that is why. Per the WHO, SARS is a contact droplet precaution disease except during aerosolizing procedures. Aerosolizing procedures include a tracheostomy, the process of intubation or extubation, during CPR, or whenever somebody is on high flow oxygen.

Illness Severity

- Mild to moderate: 81%

- mild symptoms up to mild pneumonia

- Severe: 14%

- dyspnea, hypoxia, or >50% lung involvement on imaging

- Critical: 5%

- respiratory failure, shock, or multiorgan system dysfunction

(CDC, 2020)

The illness severity ranges from mild to critical. Some people are also asymptomatic. The majority of people (81%) who have COVID-19 experience mild to moderate symptoms. Mild symptoms can include no symptoms, headaches, and body aches leading up to mild pneumonia. Most of these people do not need occupational therapy. Many of them do not even require hospitalization. The more severe (14% of people with COVID-19) are the ones that experience dyspnea and hypoxia. They generally require O2 and greater than 50% have lung involvement per their chest x-rays. Five percent of people with COVID-19 will experience a critical illness, which is mostly what we will be talking about today. These are the people that go through respiratory failure, shock, or multi-organ system requiring an ICU stay and intubation as well as many of the side effects that come along with those things.

Clinical Progression

- Day 5-8: dyspnea

- Day 8-12: acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)

- Day 10-12: ICU Admission

- Of note: Clinicians should be aware of the potential for some patients to rapidly deteriorate one week after illness onset

Generally, Days 5-8 are when patients begin to experience dyspnea. Oftentimes, this is when we see them presenting to the hospital. Days 8-12 are when they experience acute respiratory distress syndrome. This is important for us to note because many times patients can function well with relatively stable oxygen needs. This group experiencing ARDS can rapidly decline and deteriorate requiring ICU admission. This affects not only when we intervene with them but our expectations of how they will progress.

Much of the information today is going to be related to this ARDS population. As we know, there is not a lot of research around COVID, but this is starting to ramp up. However, as this is in its infancy, much of the research that we will be citing is that of ARDS as it is similar to how these people with COVID-19 progress.

Clinical Presentation

- Generalized weakness

- Dyspnea

- Delirium

- Upper extremity plexopathies

- Fatigue

- Anxiety

(AOTA, 2020)

The clinical presentation that we are seeing involves generalized weakness, dyspnea, delirium associated with these long hospital stays, and upper extremity plexopathies associated with the prone position that many of these patients are placed in. Fatigue is also an enormous problem for these patients. Lastly, they have a lot of anxiety.

Other Considerations

- Social isolation

- Occupational deprivation

- Stigma

- Caregiver exposure/illness

(AOTA, 2020)

There are other non-physically related considerations. This first is social isolation. Most hospitals are not allowing visitors, especially on the COVID units. So, they are not able to be around their families during this. They also experience occupational deprivation. There is also the stigma and fear of having COVID-19. Lastly, there is worry about caregiver exposure and illness.

Caseload Management Considerations

- Prioritization

- Prioritize those most directly impacted by the intervention

- Maximize timing of evaluation

- Promote throughout

- ICU> floor transitions, Discharge planning

- PPE Preservation

- Cluster care

- Screen patients prior to evaluation

- Coordinate with RN/PT/SLP

- Discharge Option Availability

- COVID SNF/IRF beds

- Family COVID status

- Can they assist at discharge?

(AOTA, 2020)

As this is such a new population to work with, this is greatly affecting how hospitals are functioning during this pandemic. The most important thing is that we need to prioritize the right people. You want to go into the rooms in which you know that you are going to make a difference. A large portion of this is maximizing the timing of evaluation. If somebody is independent, then it is probably not appropriate that we go see them. At the same time, if somebody on the Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS) is a -4 where they are not following commands or able to engage in anything, then it is also not appropriate that we intervene then. You need to work with your nursing and physical therapy colleagues to figure out when is the most appropriate time for OT to become involved. We also need to hele to promote throughput through the hospital. This is getting those patients from the ICU to transitioning to different floors, and most importantly discharging. We want to get these patients out of the hospital as safely and quickly as possible but also set them up for success so that they do not return to the hospital. Capacity has been a huge concern and depending on the hospital that you are in, it might not be as big of an issue as other places. However, due to the pandemic situation, capacity, bed availability, and vent availability are crucial to monitor.

In the same vein, PPE preservation is huge. Again, this is a very site-specific concern. Some places have more access to PPE than others. O course, you will need to follow what your institution is dictating. Some strategies that we have found successful in preserving PPE are clustering care. For example, if you are already in the room and treating a patient, make sure you complete all their care like toileting while you are in the room so that a CNA does not have to come in. Another example would be setting them up for a meal. These additional steps minimize the number of people putting on gowns and masks. One of the things we found most successful in our practice is screening patients through the window prior to evaluation. Our nurses have been great about leaving the bedside phones near the patients so we can call in from outside of the room to gain some information about their prior level of functioning. And, if they are up with nursing, we can also observe this through the window to see how they are mobilizing. We can then use that information to determine whether or not it is appropriate for us to evaluate at this time. If they are mobilizing with nursing, they are probably still at their baseline, and it is not appropriate that we intervene at this time. As always, you need to coordinate with nursing, physical therapy, and speech counterparts for care. If a physical therapist has just spent an hour and a half in the room with a patient, you do not want to then just go in the room to meet a patient who is too fatigued to be able to tolerate your session. It is important to time your sessions as well as give nurses strategies to help them to progress these patients even when you are not in the room.

Discharge option availability is also site-specific. Where we are working, local SNFs are accepting patients with COVID as well as our hospital has an acute rehab open. Thus, our discharge options have expanded. Initially, none of those were options were available to us. We had to work within the hospital setting to progress these patients to a level of independence where they were safe for home. It is important to be aware of your community resources to be able to set these patients up for success. Lastly, it is important to know about the family and their COVID status. Can the family assist at discharge? Have they been exposed? Have they had COVID or have they not? If a patient's caregiver has COVID and is no longer able to take care of them, it might be more appropriate for them to go to a rehab-based setting. Or, is there a way that we can facilitate them getting home without exposing any further family?

Hospital-Acquired Deficits

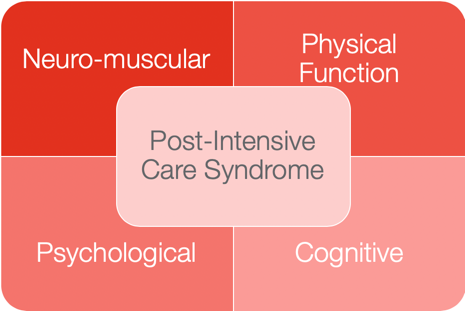

Lindsay: Hello everybody. As Julia mentioned, the research on COVID-19 and how it relates to rehabilitation and long-term functional outcomes is not available yet. That being said, we are utilizing a lot of anecdotal data that we are seeing in the clinical setting as well as previously existing literature related to different symptoms or disease processes that COVID patients are presenting with. One of those is ARDS or acute respiratory distress syndrome. The overarching concept of critical care rehabilitation as it relates to ICU survivors, specifically ARDS patients, is this idea of post-intensive care syndrome. This may be a new concept for some of you. And if it is not, bear with me while I go through it. Back in 2010, the Society of Critical Care Medicine found that patients were surviving the ICU at higher rates due to the advancements in medical care. However, those that were surviving were left with very profound neuromuscular physical deficits as well as psychological and cognitive deficits. This cluster of symptoms was pretty consistent throughout ICU survivors. They deemed this post-intensive care syndrome as seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Post-Intensive Care Syndrome. (Desai, Law, & Needham, 2013)

There is a ton of research around it, and it has now been brought to the forefront with the COVID pandemic due to the huge influx of critically ill patients. This is going to the framework that we are going to use throughout our presentation today. Figure 1 shows the four pillars that we are addressing.

- Neuromuscular

- Critical Illness Polyneuropathy & Myopathy

- Diffuse atrophy

- Brachial plexus injuries

- Physical Function

- Impairment in ADLs & IADLs

- Increased caregiver support

- Decreased 6-min walk distance

- Less likely to return to work

- Impairment in ADLs & IADLs

(Desai, Law, & Needham, 2013)

In terms of neuromuscular deficits, the risk factors for neuromuscular impairment include multiorgan failure and prolonged periods of bed rest or immobility, which obviously these COVID survivors are experiencing during their potentially month-long period of intubation and ICU stay. Previous literature on ICU survivors shows that 85% to 95% will experience persistent weakness at hospital discharge. This obviously results in atrophy, impaired deep tendon reflexes, and potential sensory loss or foot drop. We are also seeing brachial plexus injuries due to the prone positioning we are using to treat the pulmonary deficits in these patients.

In terms of physical functioning, 50% of patients at one year after ICU discharge experience deficits in ADL function, and 70% experience deficits in IADL function. Again, this is based on historical data we have on general ICU survivors, but we do not have any reason to anticipate that this will not also apply to our COVID survivor patient population given what we are seeing in the inpatient setting. Additionally, there is a decreased six-minute walk time, and they are less likely to return to work and need increased caregiver support. Critical illness definitely impacts people's ability to get back to the life they had at baseline.

- Psychological

- Depression

- Post-traumatic stress syndrome

- Anxiety

- Grief

- Cognitive

- Impairments in memory, attention, and executive functioning

- Impairment in executive functioning is associated with higher rates of depression

(Karnatovskaia et al., 2015; Wilcox et al., 2013)

From a psychological perspective, one in three ICU survivors will experience depression, and 60% of ICU survivors experience post-traumatic stress disorder. Risk factors for this are delirium, those traumatic or delusional memories of the ICU, impairments in physical functioning, the use of physical restraints while in the ICU, and prolonged periods of mechanical ventilation. Younger age is correlated with higher rates of depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress syndrome, as well as a lower level of education. Data on COVID survivors is showing that it definitely has an impact on the younger patient population, as well as those with lower socioeconomic status.

For cognition, there can be impairments in memory, attention, and executive functioning. Impairment in executive functioning is associated with higher rates of depression. Risk factors for cognitive deficits are delirium, prolonged periods of sedation, and this acquired brain injury presentation related to hypoxia which is common in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. You can see how the psychological and cognitive areas can be tied together.

Delirium in COVID-19

- Social Factors

- Isolation, quarantine, increased healthcare professional workload

- Medical Factors

- Deep sedation, prolonged MV, prolonged immobility, use of centrally acting drugs

- Psychological

- Anxiety, stress, disorientation, delusions

I want to highlight delirium because I think this is key to how we can impact change and prevention for these patients. Based on current literature, delirium is a key component that is affecting the likelihood of this post-intensive care syndrome. Unfortunately, our COVID patients are in a very unique situation that researchers believe is inciting higher rates of delirium. When you think about the COVID-19 pandemic in general, it is an all hands on deck approach that is very medically focused as there is not a lot known about the disease. These patients are decompensating very rapidly.

Of course, the first thing you have to do is stabilize the patient medically which unfortunately has created this perfect storm where the patients are isolated. We are also clustering care so the nurse or the other care providers are not in the room as much. Delirium is likely at a higher incidence, but we are just not able to track it as much as before.

And we know from the previous slides, delirium leads to deficits in cognition, anxiety, depression, as well as issues potentially returning back to their prior level. Another caveat here is that delirium has three subsets. There are agitated, hypoactive, mixed subsets of delirium. For patients who have a hyperactive or agitated subtype, they are likely to get more attention from staff. They are the ones that are trying to climb out of bed or self-extubate by pulling at tubes. Where conversely, those patients with the hypoactive subset are very motor slowed and not as interactive. If you are trying to conserve PPE and cluster care, the patient that looks like they are sleeping and comfortable may not get as much intervention. Researchers are anticipating that those clients in this subset are going to be bypassed in terms of assessment and intervention for delirium. This is one to keep on our radar as having the highest risk for functional and cognitive deficits.

Outcome Measures

We know that patients have problems in the areas of neuromuscular, physical functioning, cognitive, and psychological functioning, but how do we track them?

Neuromuscular

- Manual muscle testing (MMT)

- Hand-held dynamometry

Manual muscle testing is probably something that you are all doing in your clinical practice already. This is an objective grading global strength that you can then use to track progress. A hand-held dynamometer is a noninvasive, simple, and pretty inexpensive that has been a high predictor of functional morbidity and overall mortality. There was a recent article that showed in COVID-19 survivors with a lower grip strength equated to higher rates of intubation, and it also correlated with respiratory muscle strength. I think this is one that we could incorporate into our clinical practice that could show long-term predictors of function.

Physical Function

- ICU Mobility Scale

- Functional Status Score for the ICU (FSS-ICU)

- Boston University AM-PAC for ADLs

- Katz Index of Independence in ADLs

- Barthel Index

In terms of physical functioning, here are some outcome measures related to general mobility as well as ADLs. The ICU Mobility Scale is a zero to 10 scale for tracking the progression of mobility. It starts with zero which is passively lying in bed or being rolled by staff for repositioning. It includes sitting at the edge of the bed, standing, marching in place, etc. A ten is walking independently without a need for a gait belt. This is something that can be utilized by nursing staff, PT, or OT. It can be part of an interdisciplinary approach to tracking general mobility.

Similarly, the Functional Status Score for the ICU, or FSS-ICU, has a really high 99% inter-rater reliability. It has five features including rolling, supine to sit transfer, sitting at the edge of the bed, sit to stand transfer, and walking. Each of these features is graded from zero being unable to seven for independent. It is a really great objective measure to monitor progress.

At our site, we also use the AM-PAC for ADLs. This grades six ADLs with a scale of one to four. And then based on the input of data, it calculates a degree of impairment. This can be used to show progress, everything from self-feeding, grooming, donning and doffing clothing, and toileting.

These last two are not as sensitive, and they are not my favorites. However, I included them as they are supported by the literature. The Katz Independence of ADLs includes six ADLs. The limitations are that it is only one point for independent and zero for dependent. There is no wide range in terms of grading progress. It also is not a strong indicator for use in acute care where we are seeing slower progress. The last one is the Barthel Index. It has 10 ADLs and mobility tasks including grading it from independent, needs help, to dependent. This one only has three ways to identify a patient's progress so again it is not as sensitive.

Delirium

- Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU (CAM –ICU)

- Confusion Assessment Method – Severity (CAM-S)

- Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist (ICDSC)

- Brief Confusion Assessment Method (bCAM)

The first three, the CAM-ICU, the CAM-S, and the ICDSC are all validated for use in the ICU. The Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU (CAM-ICU) and the Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist (ICDSC) have high inter-rater reliability, high specificity, and the CAM-ICU is the gold standard for use in screening for delirium in the ICU. There is a strong breadth of research for that. The Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist also has very strong psychometric properties and one that I really like to utilize because it is based on observation. This is helpful because the patient may not be able to participate whether from profound neuromuscular weakness or what have you. With this tool, you can observe patients' interactions and might be able to get a better sense of their cognitive functioning.

And if you are using the CAM-ICU, I would strongly recommend using the CAM-S or the severity because it evaluates the severity of delirium symptoms. Sometimes it is not sensitive or helpful enough to just say, "Yes delirium" or "no delirium." Sometimes we need to be able to objectively show the severity of those symptoms from profound to mild for these patients with prolonged ICU stays.

Lastly, the Brief Confusion Assessment Method (bCAM) is validated for use on the floor. So if your site uses the CAM-ICU in the ICU, it would be great to then train your floor therapists. This one has a modified design from the CAM-ICU. It takes less than two minutes to administer and would be a really great way to continue tracking delirium outside of the ICU.

Cognition

- Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale (RASS)

- The Orientation Log (O-Log)

- Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)

The RASS, or the Richmond Agitation and Sedation Scale, is a scale from negative five meaning unresponsive to sternal rub all the way up to plus five meaning swinging, pulling at things, a danger to themselves as well as staff around them. This is another objective way to demonstrate the level of arousal in your patients, and this is also a subset of the CAM-ICU.

Another one that we enjoy using here at our site is The Orientation Log (O-Log). I think it is a pretty standard practice to assess your patients to see if they are alert and oriented x 4 (AOx4). This tool digs a little bit deeper. It is 10 questions and really gets at the heart of a patient's understanding of their situation and their circumstance. This information can be very valuable because while it is important to know where you are and what day it is, I think it is similarly as important, if not more important, to really understand what is going on with your body. This allows us to identify deficits that these patients have in their level of understanding and then be able to then provide education based on the deficits that are highlighted within The Orientation Log.

Finally, the MoCA is a great way to screen for general cognition that then can segue into other more sensitive assessments.

Psychological

- Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)

- Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R)

For the psychological component, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) is a self-assessment screen. This can be used to trigger a consult to psychology, psychiatry, or potentially an outpatient referral. This is a great way to have the patient self-assess different symptoms that they are experiencing. I would say use your toolbox and other assessments and make sure that the patient is of sound mind and cognition prior to administering a self-assessment screen to make sure you are getting accurate data.

The last one is the Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R). This is another self-report questionnaire that has the patient subjectively measure the response to a traumatic event, like a pandemic. Additionally, a stay in the ICU with prolonged intubation is definitely traumatic.

Why Prone Positioning?

- Improves gas exchange efficiency

- Increases perfusion and recruitment of dorsal lung

- Mobilizes secretions

Resource for Images of positioning recommendations: https://www.ficm.ac.uk/sites/default/files/prone_position_in_adult_critical_care_2019.pdf

Julia: As Lindsay mentioned earlier, prone positioning is an intervention that the medical teams have been using for pulmonary function. Why do they do this? Prone positioning is having somebody lay onto their belly. This improves gas exchange efficiency, increases the perfusion and recruitment of the dorsal lung and posterior inferior lobes, and mobilizes secretions. With their lungs full of fluid and with the weight of their heart, it is hard for these patients to expand their chest to breathe. By repositioning them, this can help to redistribute that perfusion and access the posterior lung. I highly recommend that you use the link provided above. It is through the ICS or the Intensive Care Society out of the UK. It provides a lot of information on why proning is important. More importantly, it has step by step pictures on how to safely prone position somebody who is sedated. It is a very complex process

There are two ways that we can prone somebody. One is when they are awake and one is when they are sedated.

Conscious Proning

- Indications

- Patients above their baseline O2 needs

- Independently able to position themselves in prone

- Contraindications

- Respiratory distress (accessory muscle use, RR over 35)

- Altered mental status

- Hemodynamic instability

- Physically unable (ex. morbid obesity, pregnancy, wounds)

- Timing

- Goal to maintain 30 minutes - 2 hours as tolerated

- Can turn alternate into side-lying for comfort

- If unable to tolerate, recommend HOB elevated >30 vs. a flat bed in supine

(ICS, 2020)

Conscious proning is when somebody is awake. This is for somebody who is above their baseline for oxygen needs but is able to independently position themselves into prone. We would not want to do this in somebody whose respiratory rate is very high, over 35, or somebody who is using their accessory muscles and already struggling to breathe at baseline. If they are confused, delirious, have any altered mental status, or are hemodynamically unstable, this is also not appropriate. Somebody whose blood pressure already plummets when you roll them into side-lying is not a patient that you then want to be prone. Other contraindications are those that are morbid obesity, are pregnant, or those who have wounds. Some people with back pain also cannot tolerate this position. Lastly, if they are not able to reposition themselves, then this is not an appropriate intervention.

When you have somebody consciously prone, the goal is to maintain this for 30 minutes to two hours as they tolerate it. They can also alternate into side-lying for comfort. Again, this is a repositional strategy to mobilize the lungs. If they can tolerate 30 minutes on their belly, 30 minutes on their side, 30 minutes on their other side, and 30 minutes on their back, this is also helpful as a proning intervention. If somebody is not able to tolerate this or if it is contraindicated, we encourage them to keep the head of their bed elevated greater than 30 versus a flat supine position. This helps for both comfort and pulmonary function.

Proning is something that is used by the medical team, but this can also be helpful during our therapy interventions because this enables the patients to recover more comfortably. For those patients who are sitting up at the edge of the bed and it is taking them a long time to recover or they have a lot of anxiety, this can be a good tool to use during your therapy sessions. Just have them lay back down as you would normally do when somebody is not tolerating your session, but encourage them to lay on their belly. You do not have to be in the room for this. Before you leave, remind them that as they are able to throughout the day to roll onto their belly. The ultimate goal with this is to prolong or hopefully completely avoid intubation by maximizing the gas exchange and mobilizing those secretions in the lungs before the disease process progresses to the point of needing intubation.

Prone Positioning of the Sedated Patient

- Indication: Moderate to severe ARDS at least 12 hours after intubation, use of paralytics for vent synchrony

- “Swimmer’s Position”

- One arm abducted to 45-70 degree, elbow at 90

- The other arm down at the side

- Head facing toward the abducted arm, neck not extended

- Slight scapular elevation

- Chest supported

- Pillows padding chest, pelvis, and knees

- Goal: 16 hours/ day

- Alternate abduction of arms and rotation of neck every 2 hours for skin protection and prevention of plexopathy

- Complications to monitor:

- Wounds

- ETT dislodgment

- Brachial plexus injury

- CRRT line flow issues

- Facial edema

- Corneal abrasions

Prone positioning of a sedated patient is much more complicated, and this is indicated for moderate to severe ARDS patients, at least 12 hours of intubation, or when somebody is on paralytics. You do not want somebody who is already fighting the vent to now repositioned in a prone position because that is more difficult to regulate.

In that previous link, there are pictures of the Swimmer's position that I am going to describe. You want these patients to have one arm abducted to 40 to 70 degrees with the elbow at 90. You do not want the arm elevated too high, but you want it bent up a little bit. The other arm will be down at the side. Their head should be facing towards the abducted arm with the neck not extended. You also want the neck neutral or if needed, in slight flection with some slight scapular elevation or a slight shoulder shrug. They should have a pillow under their chest so that it is supported. This gives the shoulders a little bit of forward flexion.

In addition to the pillow at the chest, you also want pillows at the pelvis and knees. This is very important in males to ensure that the genitalia is not in a compromising position. The ultimate goal is to have a patient in a prone position for 16 hours a day. Like you would normally turn a patient who is on paralytics, you are going to want to rotate them and turn them every two hours. In this case, when they are in prone, you are going to alternate the abduction of the arms and rotate the neck to the opposite side every two hours. This is both for skin protection of the face but also to prevent a brachial plexopathy, which we are going to review.

Complications are wounds typically on the face. We have also seen some wounds from peripheral IVs that are resting on their arms or blood pressure cuffs resting in places that we are not as used to checking. There can be ETT dislodgement. We do not want to accidentally extubate somebody during proning or pull out their CRT lines. The resource from the ICS walks through multiple strategies to do this safely to avoid this. There can also be facial edema from their face being in a dependent position and corneal abrasion. It is encouraged that you use ointment on the eyes and/or tape them shut while you are doing this. This is generally a three to a five-person job as it is a complicated process because of their lines. If ECMO is involved, it becomes a much more complicated process. Of course, this is up to the medical team to dictate when it is appropriate for somebody. This is not up to us, but we can use our expertise to make sure that these patients are positioned correctly. In some hospitals, I also know that therapists have been utilized on prone teams to go around and to help turn these patients forward and backward because it does require so much manpower.

Brachial Plexopathy

- Prevention:

- Proper prone positioning

- Nursing education

- Assessment:

- Sensory, motor, and reflex assessment to identify the level of injury

- Treatment:

- Positioning

- Ensure muscle nerves in functional positioning, not on tension

- Splinting

- Education

- Compensatory strategies

- Neuro-reeducation

- Positioning

(Quick & Brown, 2020)

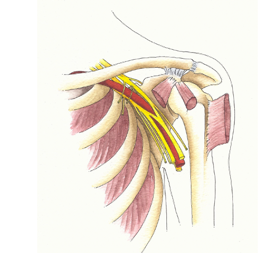

As you can see from this picture in Figure 2, the nerves pass under the clavicle through the axilla and down the arm.

Figure 2. Brachial plexus. (Photo Attribution: Alice Roberts / CC BY (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0))

The ultimate goal is for patients to leave without brachial plexus injuries. This is something that is preventable through proper prone positioning, and a lot of this has to do with nursing education. We can educate them on what a proper prone position looks like, why it is so important, and what the side effects of improper placement of the arms and neck could cause. When somebody is more awake and able to engage in a formal assessment after they have been in a prone position, it is important that you assess both their sensory and motor function, and if appropriate, their reflexes. This can help identify any level of injury. Is this a peripheral injury that is happening below the elbow? Is it a radial groove injury? Is it something that is happening more at the neck level?

From an acute care side of things, the most important treatment for brachial plexus injuries is positioning. We want to ensure that no muscle nerves are on tension especially in the pec minor area as this is where a lot of brachial nerve tension injuries can happen. We can use splints for positioning. We have been mostly utilizing an off the shelf D-ring type splint because of a lot of radial nerve injuries with wrist drop. A simple D-ring splint can be really helpful in keeping the wrist in a functional position. If you are noticing more tone or more finger involvement, you can use a resting hand splint.

It is also important to educate both the nurses and the patients on why this happened, and what the recovery process is going to look like. Compensatory strategies are important because peripheral nerve injuries take a very long time to recover if at all. Luckily, all of these injuries are related to tension and strain on the nerve as opposed to what we commonly see like lacerations or complete injuries to the nerves. So the prognosis for recovery is better, but it is not guaranteed.

In these acute phases, we need to teach these patients compensatory strategies. If a patient now presents with bilateral brachial plexus injuries compounded with their family not being present and nursing not consistently at their bedside, they need access to their environment. We can teach them compensatory strategies or provide adaptive equipment so that they can access their call bell, participate in ADLs, use their remote control, or use a device. This can help them to feel empowered and increase their engagement to decrease delirium.

Lastly, neuro-reeducation is also appropriate. This will most likely happen more at the acute rehab phase (step-down from ICU) or in the outpatient phase, but you can always initiate task-specific training in these patients.

Early Mobility

- It is safe and feasible

- Reduces risk of ICU-acquired weakness

- Coordinating with interdisciplinary team members

- RN, CNA, PT, RT, etc.

- Progressive mobilization

- Chair mode

- Edge of bed/dangle

- Transfer out of bed (passive vs. active)

- Optimize seating and positioning

(Schweickert et al., 2009; Parker, A., Sricharoenchai, T. & Needham, 2013; Clancy et al., 2015)

Another really important intervention is early mobility. What we know from all of the literature is that it is safe and feasible to mobilize patients at an ICU level even if they are intubated. It reduces the risk of ICU-acquired weakness which as Lindsay spent a lot of time talking about has such a profound impact on their long-term function and mental and physical health. As soon as we can intervene and it is safe, it is important that we do so. This requires a lot of coordination with the interdisciplinary teams and that the doctors understand that what we are doing is safe and feasible. Coordinating with RT is especially if important if the client is on a ventilator or is trached. They may even come in the room to help us if needed. Their settings may also need to be adjusted based on their mobility. We also want to coordinate with the physical therapist as well as the nurse and CNA.

Progressive mobilization is the plan. At the very beginning, some patients might only tolerate being positioned in a chair mode. If they have not been in an upright position for two or three weeks at this point, from hemodynamic and activity tolerance standpoints, this might be the first thing that they tolerate and that is okay. If they are able to tolerate more than that, you can transition them to the edge of the bed, where again, you are monitoring hemodynamics, activity tolerance, and trunk control. This is a good place to formally assess their strength as well. And then from there, you can transfer them out of bed. It is appropriate to trial them with a non-mechanical lift like a Sara Stedy or a two-person assist. Or, you can do a one-person assist to trial standing based on your strength assessment. However, if they are not strong enough or cognitively appropriate to engage in that sort of transfer, then I would suggest the passive means to get them to a chair. This could be a Hoyer Lift or what we commonly use is just a lateral slide to stretcher or Stryker type chair.

Upright tolerance is so important not only from a weakness standpoint but also from the respiratory standpoint to progress them. A seated position can help to progress off the vent quicker. It is important to note though that you have to make sure that they have the optimum seating and positioning depending on appropriate cushioning or pillows or whatever propping that they need. If these patients are profoundly weak, they are not going to have the strength or the activity tolerance to be able to reposition themselves safely. It is important to monitor that and communicate with nursing.

Delirium Management

- Regulate sensory input

- Apply hearing aids, dentures, glasses

- Sleep Hygiene

- Environmental modifications

- Clock, calendar, lights on during the day

- Communication

- Adaptive communication strategies

- Collaborate with SLP

- Re-orientation

Lindsay: From a delirium standpoint, again I feel that OT specifically is an absolute powerhouse in this domain. If we go back to school and what we learned about the PEO model, we understand that you cannot have a person without an environment and an occupation. Everything is transactional between those three components. Thus, it is no surprise to us that COVID has been catastrophic to people. We are making them isolate and reducing the interaction with staff. They are not able to get up, mobilize, or engage in occupations or meaningful tasks. This unique situation has been quite catastrophic for our patients. This is our time to shine.

Assessing for delirium with those outcome measures is key. As soon as we can start assessing for delirium, we should and then communicating that information to our interdisciplinary team members and following that up with recommendations. This can be things as simple as applying hearing aids, dentures, and glasses. If somebody cannot appropriately interact from a sensory perspective, they are more likely to fall into this delirious state. We need to give them the sensory regulating tools they need to be able to interact with their environment.

Sleep hygiene is another big area where we can have an impact. We can coordinate with nursing and other team members to cluster care so that people can get a nap during the day if they need it. We can also cluster care during the evenings so that they have longer periods of time where they are not interrupted.

We can also modify the environment. What can we do to set up the environment for long-term benefits? When the caregivers walk in the room, they should turn on the lights and make sure there is a clock or calendar visible or a calendar on their bedside table that can help orient the patient throughout the day.

We also want to collaborate with our speech therapy colleagues to figure out adaptive communication strategies or an adaptive call bell. If somebody is in respiratory distress and due to neuromuscular weakness cannot press their call button, this can increase anxiety and their posttraumatic stress response. A call light can truly be a lifeline for patients. We need to set up the environment, the occupation, and modify specific client factors to make patients as independent and as safe as possible.

Lastly, we want to work on reorientation. I think the O-Log is a great objective measure to figure out where the patient is and then follow that up with a calendar and verbal education. They could also use a journal or an ICU diary that I will talk about in a little bit.

Functional Engagement

- ADL re-training

- AE/DME training

- Energy conservation and pacing

- Symptom identification and management

- Breathing techniques

Along the lines of early mobility, we want to get people engaged in ADLs as quickly as possible. We know that neuromuscular weakness and pulmonary function deficits are huge in this patient population. Using our expertise, we can modify ADLs using different adaptive equipment or durable medical equipment strategies. We can also use energy conservation techniques to promote independence. Another one that I think is important is symptom identification. Many of our patients have been on the younger side. This might be their first time with a specific disease process or illness that has required hospitalization and they do not always know when they have reached their limit in terms of endurance or activity tolerance. We can help these patients identify their breaking points in terms of safety and fatigue level and how to manage that. We can also provide safe and appropriate breathing techniques for our patients who have been on the mechanical ventilator for a prolonged period of time or have had pneumonia. This can help them to engage in meaningful activity again.

Mental Health

- Cognitive engagement

- Word search, crosswords, puzzles, maze

- Social engagement

- Facetime, phone calls

- Establish a routine

- ICU Diary

- Mindfulness Activity

I clustered functional cognition as well as psychological well-being into this mental health category as you really cannot have one without the other. Additionally, we learned that deficits and executive functioning are independently linked with increased rates of depression. You can use things like word searches, crossword, puzzles, and different apps to engage patients.

Speaking of the phone, social engagement via FaceTiming with family is huge in our hospital. We are also lucky enough to have five iPads in our therapy department that we are able to bring in for our sessions. With this, they can talk with family and the family can even watch the therapy session. If the patient does not have access to a smart device, phone calls are also sufficient for them to touch base with family.

Routines are important. If a patient has a routine, it is a little bit easier to cluster care versus just popping in and out whenever the patient presses their call bell or needs something. Not only is this great for the patient's engagement and their mental health, but it also is a little bit easier to have staff support the patient in that.

An ICU diary is a wonderful intervention that you guys can search on Google. Basically, it looks a little bit like a journal. The one that we use here has one column for the date and one big column for free text. If the client is unable to write, this can be done by staff. Then once the patient is able to participate, they are able to read and look back at all the things that have happened during their hospital stay. It improves orientation, short-term memory, and definitely helps with the psychological components of anxiety and depression.

Lastly, mindfulness activities are important. This is something that I have found success with, especially with our floor status. For patients who are a little bit more mobile or their tolerance is a little bit more robust, I have found some mindfulness breathing exercises and some short 10-minute videos that can help people to disconnect with all the chaos going on around them. This can help them to reduce anxiety.

Case Study #1

- Sally - 78yo F

- 45-day hospital stay (20 days in ICU)

- Son and daughter-in-law passed away

- Husband is critically ill

- Activity Tolerance

- ADL engagement

- Cognition

- CAM-ICU for 10 days

- bCAM negative on floor

- Psychological Trauma

- Hospital journal, establish routine

- Social Isolation & Deprivation

- Daily calls with her daughter

- Leisure engagement

Sally is a 78-year-old female and she was in the hospital for 45 days with 20 days in the ICU. Her situation was quite catastrophic in that she and her husband had their son and daughter-in-law living with them. All four of them contracted COVID-19. Her son and daughter-in-law actually passed away in our ICU. Additionally, her husband was critically ill in the ICU with a tracheostomy and had a very poor medical prognosis.

By the time I worked with Sally, her activity tolerance was very poor and she had some mild cognitive deficits. She was CAM-ICU positive for 10 days of her ICU stay. By the time I saw her on the floor, I had done the bCAM as an outcome measure, and she was negative. However, she carried significant psychological trauma from not only her experience in the ICU but also the experience of losing her son and daughter-in-law. She also could not see her husband as he was in a very tenuous medical situation in the ICU.

I started a hospital journal with her. She reported, "When I wake up in the morning, I'm really happy and motivated. But by 10:00 or 11:00 in the morning, it all hits me and it lays really heavy in my mind. Then, I just do not want to do anything else." She was definitely experiencing depressive symptoms and grieving the loss of her family and her function.

She was extremely independent and the social isolation and deprivation piece was also having negative results. In addition to this hospital journal and establishing a routine, we also established a routine for daily phone calls with her daughter because this was her one family connection outside of the hospital. This helped her with the grieving process.

For leisure engagement, she enjoyed reading her Bible and writing out different scriptures. This was something that we helped her to set-up.

Case Study #2

- Randy, 40 yo

- Independent, highly active at baseline. No comorbidities

- 38-day hospital stay

- 22-day intubation prior to tracheostomy placement

- Activity tolerance

- Frequent rest breaks

- Chair positioning with nursing outside of session

- Hyperactive delirium

- CAM + for 15+ days

- ICU diary (at the bedside, a spouse at home journaling hospital course)

- ADL engagement

- Anxiety

- Breathing strategies

- Face timing significant other during the session

- Maximize communication strategies due to difficulty pointing

- R radial nerve injury

- Splinting

- Positioning

- Compensatory strategies

Julia: This is Randy. He was an independent 40-year-old that was highly active at baseline. He traveled a lot and went to the gym all the time. He had no previous comorbidities. He had a 38-day hospital stay and then transitioned to a two-week acute rehab stay. Ultimately, he was in the hospital for over 50 days. He was intubated for 22 days prior to his tracheostomy placement, and he was just profoundly impaired in almost every realm.

He had a hyperactive delirium and was CAM positive for 15 plus days crawling out of bed, pulling at lines, etc. The significant thing for him was engaging him in ADLs and getting him into a routine. We also implemented an ICU diary. As he was not able to engage, we communicated closely with his spouse at home and had his spouse journal. Now, Randy is able to reflect on that with his spouse. His activity tolerance due to profound neuromuscular weakness and fatigue was significant. He required frequent rest breaks even for washing his face. We also asked nursing to help to position him in chair mode throughout the day. This helped regulate his delirium and worked on his upright tolerance.

Once he did begin to clear, he had significant anxiety. We utilized breathing strategies. We also FaceTimed his significant other during every session because that was a really calming force for Randy. The familiar voice was helpful for us to redirect him. We also maximized his communication strategies because he had that tracheostomy.

He also had a right radial nerve injury so he could not use his right hand. He was left hand dominant, but he was so weak that he could barely move his arm against gravity. For the wrist drop on that right arm, we placed a D-ring splint on his hand. We also attached a stylus that stuck out of his D-ring splint that he could use to hit the call bell and change the station. He was also able to use the iPad that he had in his room to call his husband when he wanted. We positioned him in elevation because he had significant edema. We also used a lot of compensatory strategies for him to be able to interact with his environment a little bit more and use the iPad to communicate with us. He is now independent at home and rocking it.

Resources

- Facebook

- COVID4OT Group (general COVID)

- COVID4CCOT Group (critical care)

- Royal College of Occupational Therapists

- Hospital Elder Life Program

- Johns Hopkins University

- Everybody Moves Campaign

Lindsay: This is the last slide, and then we will get into questions. If there is one thing that we have learned from this whole COVID outbreak is that it really is a global effort, and I have absolutely been so impressed with the sharing of knowledge. That is one of my passions and reasons for doing this webinar. This resource page has been a huge lifeline for us as we have created our protocols here at our hospital.

There are two Facebook pages that have been amazing. COVIDRehab4OT is just a general COVID rehabilitation page. This includes everything from acute care, outpatient, home health, etc. Then the COVID4CCOT page is specific to critical care. There have been some amazing therapists out of the United Kingdom, mostly from the Royal College of OTs. They have been so helpful. You can write a question and watch people submit their anecdotal evidence and any literature they are aware of. It has been absolutely amazing.

The Hospital Elder Life Program is here in the US and they have a very robust delirium program. The second link just rolled out yesterday. It has free delirium protocols. They have one for interventions and one for assessments. This is a great resource that you guys can use more in-depth.

Johns Hopkins University has an Everybody Moves Campaign that is great. It has a ton of information like handouts for educating patients, clinicians, as well as handouts for exercises for patients to complete. It is a grassroots effort to combat immobility in acute care and post-acute settings.

The last one is the Rehab Care Alliance which has an online collection of resources specific to COVID rehabilitation.

Questions and Answers

Would you recommend early mobility and co-treating or is it too much of a risk?

I think co-treating is amazing. Again, given this kind of the overarching theme of the pandemic and PPE utilization, we really want to try to cluster care as much as possible. Sometimes having multiple sets of hands is what is safest for these patients. I think we can all think back to situations where we have been in a patient room, not necessarily in the ICU, where an extra set of hands would have been helpful. Or, we might have been able to challenge the patient a little bit more. I think if speech wants to work on a swallow evaluation or some sort of cognitive component and OT wants to work on ADL performance in a progressive upright position, maybe that is a great time that you guys go in together. You are using each other's skill set a little bit to progress the patient. Whereas, if you went in solo, you would not have been able to accomplish as much. This is the thing with nursing. When we go into rooms, we ask, "Hey, is now a good time to do a linen change?" Maybe we can go in together and the nurse can pass meds, do the hourly vitals, and then we can help roll and mobilize the client for linen changes. From a billing perspective, please seek out information from your specific sites, but I think clustering care benefits the clients.

What is the average length of treatment stay for your COVID positive patients? And, how many days are you treating them?

I believe our hospital length of stay is about seven days for COVID patients, but those are primarily people that we are not seeing on our caseload. I would say most of ours have been like 20 to 30 days. We have been doing a pretty good job of setting our frequencies based on how we would normally set frequencies for patients. So in the ICU, it may be two to three times a week. Then, if they have a discharge plan, we will titrate our frequency based on that. There are no hard and fast rules.

Is a patient able to be on a ventilator without being sedated? Or when you start progressive mobilization, is the patient off the ventilator and using supplemental oxygen?

Again, this is all patient-specific, I would say that for most patients, the ventilator is extremely uncomfortable. Thus, they have to have some sort of pharmacological component to take the edge off. This is when we would use that Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale. If somebody is maybe a RASS of negative three where they are waking up and opening their eyes and scanning the environment, I would say they are not sedated to a degree where mobilization would be unsafe or harmful. We might proceed as long as all those safety and medical components check out.

How often do patients demonstrate delirium? Does delirium develop while a patient is at the hospital or does it begin to develop prior to hospital admission? How long does it usually take for delirium severity to decrease?

Great questions. Current literature for the general ICU patient states approximately upwards of 80% of people in the ICU will experience delirium at any given time. Delirium typically starts in the hospital due to the sedation, intubation, and all of that. However, there are some specific risk factors such as infection, advanced age, and decreased mobility in the community setting where somebody may come into the hospital with symptoms pr a component of acute delirium or altered mental status. It is really hard to say. How long it takes for delirium to decrease depends on the patient. I think that is why it is extremely important that we intervene and start assessing patients as soon as possible

Do you see a correlation between impaired cognition and disturbed breathing? Literature supports faulty breathing as learned behaviors that affect cognition via respiratory alkalosis. OT's role in psychosocial and psychophysiology is a powerhouse.

Yeah, I would agree with you. I think we know that people with delirium have difficulty weaning from the vent. They have prolonged periods of ventilation due to the inability to wean. I think there truly is a correlation based on the literature that shows changes in cognition leads to impaired breathing. Staring those interventions early can prevent and/or reduce the duration of delirium.

Any breathing techniques that specifically help or hurt for COVID patients?

Breathing strategies that we use include a lot of pursed-lip breathing, which you can also employ with patients with COPD or other obstructive lung diseases. We actually find that cueing patients to focus on their exhalation is usually more successful as they have more control over that. When you encourage them to try and take a deep breath and they can't, it can prolong that cycle of anxiety and shortness of breath. Encourage them to push that air out. We also use a huffing technique like you are trying to fog up a window or a mirror. This forces that exhalation and usually gives them a greater sense of control.

How does the positioning of the arm being abducted affect the outcomes of proning a patient? Is it used to prevent a brachial plexopathy?

Yes, exactly. It helps to take some of the tension off of the brachial plexus in the direction that your head is turned. The goal of that ultimately is to decrease brachial plexopathies, especially in the cervicogenic area.

What would likely cause a healthy 40-year-old patient to have such severe respiratory distress? And, do you suspect an underlying cause? Does the severity of the condition depend on age, sex, and prior patient's health?

Right now, we just really do not know enough about COVID to know that. Some of the young healthy patients that we see have no known comorbidities. We do see a lot of young patients with obesity, hypertension, and diabetes that have complex cases, but we are also seeing healthy patients that have no other indicators. The disease is just too new for us to fully understand exactly what is going on with that.

Can you explain the value of the dynamometer for COVID patients?

This gives us an objective measure of the neuromuscular weakness that they are having. We can also use it for assessment of brachial plexus injuries and brachial plexus recovery to track their progress as they go.

Can you explain how you would explain hospital journals to a patient to set them up?

I normally say, "I've noticed that you were experiencing some delirium in the ICU and you are having issues with your short-term memory and orientation. This is a great way to be able to look back at all the things that have happened to you. And it might clarify some questions or maybe some traumatic memories that you remember." This can also help them to see the progress that they are making. It depends on why I am using the hospital journal on how I frame that discussion.

Can you explain the difference between the CAM-ICU and the CAM Severity outcomes?

The CAM-ICU is a screen for the presence of delirium. Delirium is an altered level of consciousness with decreased attention and then either disorganized thinking or a change in the level of arousal. Using the CAM will assess whether or not delirium is present or not. If delirium is present, then you would go to the CAM Severity Scale. Based on that inattention, disorganized thinking, the altered status of the level of arousal, you will grade that. It lays it out really nicely and tells you how many points to give for each subsection. Sometimes, we find in the ICU that it is not necessarily as powerful to just say, "Yes/no, delirium is&