Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Assessments In Mental Health, presented by Olivia Petrucci, MS, OTR/L.

*Please also use the handout with this text course to supplement the material.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to identify strategies for evaluating adults in mental health settings.

- After this course, participants will be able to describe key mental health-focused assessments.

- After this course, participants will be able to explain how assessments guide intervention development and discharge planning

Introduction

Today, I'm looking forward to sharing some key assessments in my practice that I have found very helpful in the mental health setting.

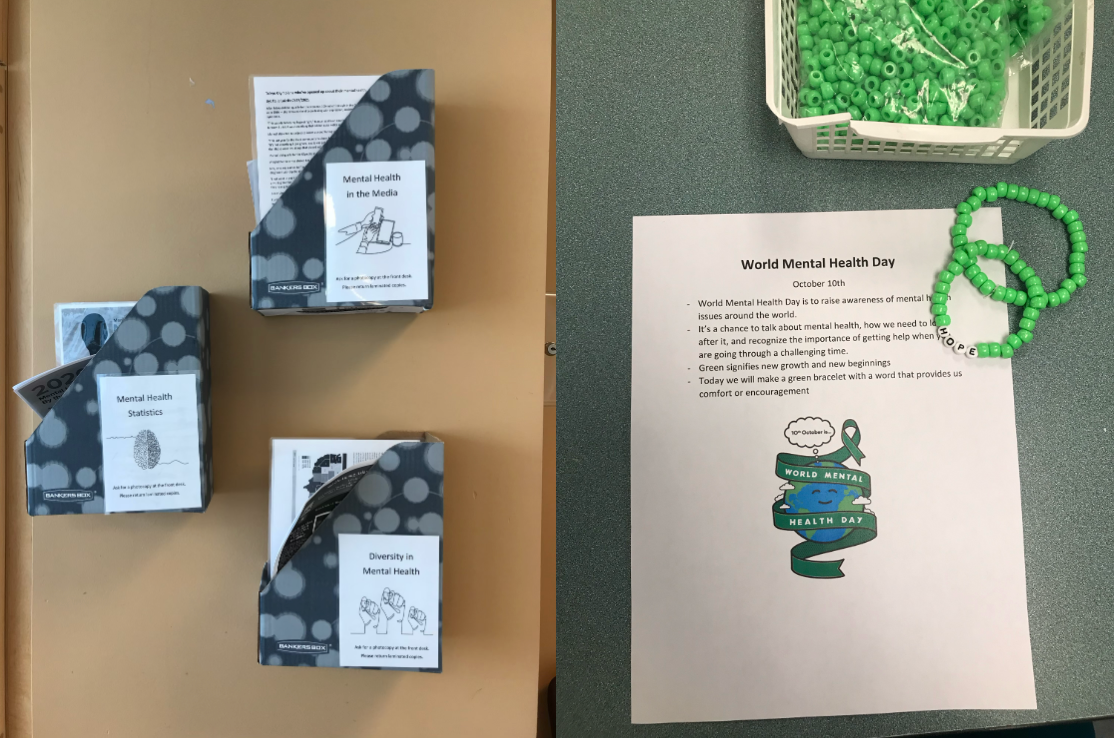

Before we get into the content today, I just wanted to take a minute to show you what I do as a psychiatric occupational therapist. These two photos in Figure 1 are from World Mental Health Day, which we celebrate every October to hold a space that feels uplifting and validating for our patients.

Figure 1. The author's photos from World Mental Health Day.

We do creative therapeutic projects—for example, the bracelets displayed to the right of the screen—and hold group discussions that create a safe space to discuss the importance of mental health, reduce stigma, and build everyday healthy coping skills. The pictures to the left include a variety of resources on mental health in the media, current mental health statistics, and materials highlighting diversity and mental health. I intentionally try to keep these resources available throughout World Mental Health Day for patients and the staff members.

Mental Health Statistics

I want to emphasize the prevalence and seriousness of mental health in the United States. One in five U.S. adults experiences mental illness each year, and suicide is the 12th leading cause of overall death in the country. The average delay between the onset of mental illness symptoms and receiving treatment is approximately 11 years. Some key barriers individuals may face include stigma, limited access to care, and low health literacy. These statistics underscore the critical importance of our role as occupational therapy practitioners (OTPs) in working with patients who have mental health conditions and ensuring they receive appropriate assessment and intervention.

Role of OT in Mental Health

Occupational therapy practitioners have a deeply impactful role in mental health. As OTPs, we use occupation as a therapeutic tool to promote mental health and support participation in daily life for individuals who are at risk for or experiencing psychiatric, behavioral, and substance use disorders. We provide occupation-based evaluations and interventions that are grounded in each individual's unique needs and goals. Most importantly, we work collaboratively with our patients to help them engage in meaningful activities that support their overall health, well-being, and quality of life.

Mental Health Practice Settings

Here are examples of different practice settings where occupational therapy practitioners may work in mental health. The first is acute psychiatric units, which is the setting I currently work in. These are short-term, high-acuity units, usually within hospital-based settings, primarily focusing on patient stabilization.

We also work with patients in emergency departments, where mental health crises are often first identified and addressed. Another setting is partial hospitalization programs, or PHPs. These structured outpatient programs typically operate Monday through Friday and offer skill-based group interventions focused on coping strategies and community integration. Many patients transition to a PHP after discharge from the acute care unit to help maintain a healthy daily routine and build consistency.

Community mental health centers offer more long-term outpatient support for individuals needing ongoing care. Residential treatment centers provide long-term residential care, often for individuals experiencing more severe or persistent psychiatric symptoms. We also encounter group home settings, smaller residential environments with supervised living and varying levels of support based on individual needs.

Lastly, it's essential to recognize that we may work with patients with mental health conditions even outside traditional psychiatric settings. This includes general medical units such as surgical or rehabilitation floors, where patients may have co-occurring psychiatric or mental health diagnoses. So even if you are not currently working in a dedicated psychiatric setting, this information may still be relevant to your practice.

Common Diagnoses

The common diagnoses seen in mental health settings include bipolar disorder, depression, generalized anxiety disorder, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), borderline personality disorder, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). While the symptoms associated with these diagnoses can vary significantly from one individual to another, our primary focus as occupational therapy practitioners remains on how these conditions affect a patient’s functional performance in daily life.

For example, a patient with depression may struggle with executive functioning, which can directly impact their ability to manage transportation, handle money, or maintain self-care routines in the community. Assessments can pinpoint these types of challenges while also recognizing a patient’s strengths. This insight allows us to tailor our interventions to support meaningful participation in their everyday lives.

Interprofessional Team

As occupational therapy practitioners, we participate in a collaborative approach to care. Psychiatrists, who are medical doctors, play a central role by diagnosing psychiatric conditions and prescribing medications. Psychologists provide psychotherapy and conduct psychological testing to help guide diagnosis and treatment planning.

Social workers, who many of you may already be familiar with in various practice settings, address patients' psychosocial needs, coordinate discharge planning, and connect individuals with essential community resources. Nurses are another vital part of the team. They monitor psychiatric symptoms, administer medications, and are often the first to observe changes in a patient’s behavior or identify emerging safety concerns.

Finally, case managers are essential in ensuring coordinated care. They help arrange necessary services, support continuity across levels of care, and assist in the patient’s transition to outpatient or community-based settings. Each of these professionals contributes uniquely, and collaboration among all team members is critical to providing comprehensive, patient-centered mental health care.

How Assessments Guide the OT Process

The evaluation process is critical to our occupational therapy practice in mental health. It provides valuable insight into a patient’s current functional abilities and helps inform both the treatment team and the patient themselves. Evaluations can support the need for ongoing services, whether returning home with supports or transitioning to a higher level of care, such as a group home. They help guide our interventions in individual and group settings, establish appropriate and measurable goals, and highlight a patient’s strengths alongside areas that require improvement.

Much like any clinical process, our assessments guide each step of the OT process. After meeting with a patient and completing the assessment, we establish goals, implement interventions— one-on-one or in groups—and ultimately contribute to discharge planning and continuity of care. Assessments also play a key role in individualizing treatment plans. By clearly identifying a patient’s strengths and barriers, we can justify the need for specific services and determine the most appropriate level of care.

For example, I once worked with a patient who had significant difficulty managing money and medications. Through our assessment, we worked with the family to implement supportive strategies, such as assisting with online banking and bill payments. We also coordinated VNA services to help with medication management. This targeted, practical intervention emerged directly from the information gathered through the assessment.

Finally, assessments enhance our ability to collaborate effectively with the broader interprofessional team. They offer objective, occupation-centered data that complements the insights of our colleagues in psychiatry, nursing, social work, psychology, and case management, ensuring a well-rounded and coordinated approach to care.

Important Considerations

Some important considerations to keep in mind when completing an assessment and sharing the results include maintaining confidentiality, following HIPAA guidelines. This means that if a patient is not comfortable with their assessment results being shared with a family member or caregiver, we must respect their wishes and ensure their privacy is protected.

It’s also essential to use culturally relevant and appropriate tools to reduce bias and promote equity in care. I always emphasize the importance of having a hospital-approved interpreter present if the patient speaks another language. This ensures that the evaluation is accurate, respectful, and inclusive, and that the patient fully understands and can participate in the process.

We also want to be cautious not to rely too heavily on any assessment tool. Our clinical reasoning is key, and we should use a triangulation process—drawing on multiple sources of information to get a comprehensive picture of the patient’s abilities and needs.

In every evaluation, we should apply trauma-informed care principles, mindful of past experiences that may affect how a patient engages with us. Additionally, we rely on our therapeutic use of self—our ability to be present, empathetic, and responsive—to foster trust and connection. These principles will be explored further below.

Trauma-Informed Care

Many of you may already be familiar with the concept of trauma-informed care, and it is especially important in the mental health field. A significant number of our patients receiving treatment for psychiatric conditions have histories of trauma. When we complete an assessment, we must remain mindful of these histories and take steps to prevent further harm or retraumatization.

Trauma-informed care requires us to approach each interaction with sensitivity and awareness. This means creating a safe, respectful, and supportive environment throughout the assessment process. Six key principles of trauma-informed care guide our approach and help ensure that it is clinically effective, compassionate, and affirming.

The first is safety, which includes both physical and emotional aspects. This principle forms the foundation of the therapeutic relationship. It involves establishing predictable routines, respecting personal space, and creating an environment where the patient feels secure enough to participate in the therapeutic process fully.

Trustworthiness and transparency are next. This involves clearly explaining the purpose of each assessment, outlining what the patient can expect, and being open about how the gathered information will be used. Providing this level of clarity helps to build trust, especially for patients who may have experienced a loss of control in previous healthcare or life situations.

Peer support is another essential principle. I strongly encourage patients to connect with others who share similar experiences. In acute inpatient psychiatric units, this often occurs naturally through group sessions. In outpatient settings, I recommend participating in support groups or finding other ways to connect with individuals who can offer mutual understanding and encouragement.

Collaboration and mutuality follow. I often remind others that we work with our clients, not on them. Our assessments should be as collaborative as possible, allowing the patient's voice and perspective to be part of the process. This helps reinforce the idea that they are partners in their care, not just recipients of services.

The fifth principle is empowerment, voice, and choice. Providing choices, even small ones, can be incredibly empowering. I like to ask patients if they would prefer to complete their assessment before or after lunch, or whether they’re more comfortable with a morning or afternoon session. Offering these options gives patients greater autonomy and participation in their care.

Finally, cultural, historical, and gender issues must be considered. We must acknowledge and respect a patient’s cultural background, lived experiences, and personal identity when selecting and administering assessments. Doing so ensures that our care is relevant but also affirming and inclusive.

Therapeutic Use of Self

Therapeutic use of self is a concept we are all familiar with as occupational therapy practitioners. It involves intentionally using our personality, insights, and communication style to develop a collaborative and trusting relationship with the patient. This relationship becomes the foundation for facilitating the therapeutic process.

Through therapeutic use of self, we can build meaningful rapport and gain a deeper understanding of a patient's individual goals, values, and lived experiences. It emphasizes cultural humility and empathy, encouraging us to approach each patient with openness and a genuine willingness to understand their perspective. Importantly, therapeutic use of self aligns closely with the principles of trauma-informed care by promoting emotional safety and trust. This approach helps patients feel seen, respected, and supported throughout their engagement in therapy.

Evaluation Sequence

This is the typical evaluation sequence I follow in psychiatric settings. It usually begins with a thorough chart review, which involves examining the patient’s medical record and admission notes to gather background information and identify any immediate considerations or precautions.

After reviewing the chart, the next step is to meet with the patient and begin building rapport. During this initial interaction, I clearly explain my role as an occupational therapist within the mental health setting. Establishing this understanding helps set the tone for a collaborative relationship and encourages openness.

I completed a comprehensive OT profile guided by the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework (OTPF). This allows me to learn more about the patient’s interests, values, daily routines, goals, and challenges in a way that centers their voice and perspective.

Finally, I administer a standardized assessment appropriate for the setting and the patient’s needs. Each step builds on the one before it, helping to create a well-rounded and detailed picture of the patient’s current functioning. Establishing rapport early on is especially important, as it fosters engagement and helps ensure that the assessment outcomes are accurate and reflective of the patient’s actual abilities and needs.

Preparation: Chart Review

The first step in the evaluation process is the chart review, which falls under the preparation phase. During this stage, I review the patient’s psychiatric history, including their current diagnoses and any past hospitalizations. This provides a foundational understanding of their clinical background and helps shape the initial approach to evaluation.

Next, I look closely at the current symptoms the patient is experiencing. This might include psychosis, anxiety, depression, or the presence of auditory or visual hallucinations. Gaining insight into these active symptoms helps me prepare for a more effective and responsive patient interaction.

Precautions are also a critical part of the chart review. To ensure the safety of the patient, myself, and others in the treatment environment, I always check for any suicide or self-harm precautions, as well as assault precautions. Awareness of these considerations is essential for maintaining a safe and therapeutic space.

Reviewing the patient's trauma history is another crucial step, as it provides context that can guide a trauma-informed approach to care. I also assess substance use, including alcohol, drug, and tobacco use. I look for patterns of use, current behaviors, and any previous efforts the patient has made to support sobriety, such as participating in medication-assisted treatment or attending Alcoholics Anonymous meetings.

Finally, understanding the patient’s support system is key. I look for information about who is in their corner—family members, friends, or outpatient support such as a psychiatrist or therapist. Knowing the extent and reliability of these supports helps inform both treatment planning and discharge recommendations.

Sample Chart Review

Here is a sample chart review that I created to illustrate how we can gather and organize key information during the evaluation preparation phase. In this example, I’ve highlighted important areas including the patient’s diagnoses, current symptoms, and any relevant precautions.

Tim is a 45-year-old male with a history of bipolar disorder and ADHD. At the time of admission, he is experiencing psychosis, which is a significant symptom that will inform how we approach the assessment process. He recently lost his job in the health insurance field and has been off his prescribed medications for the past four weeks, which may be contributing to his current psychiatric state.

Tim also has a history of assaulting others in the community and is currently on assault precautions. This is a critical piece of information, as it directly impacts the setting and structure of our initial interaction. For safety, it would be essential to meet in an open space where both the patient and I feel comfortable and secure.

Additionally, upon admission, Tim reported drinking alcohol daily and using marijuana every night. These patterns of substance use are important to note, as they can influence both his current mental health presentation and his recovery planning. His close friends and family have expressed concern about his ability to manage daily tasks and reenter the workforce, which gives us insight into the functional areas that may need to be addressed through occupational therapy.

This chart review offers a comprehensive view of the patient’s current situation, allowing us to prepare thoughtfully for the assessment while remaining aware of clinical priorities, safety needs, and areas for therapeutic support.

Occupational Profile from OTPF-4

After completing the chart review phase, the next step is meeting with the patient, establishing rapport, and completing an occupational therapy profile. The Occupational Therapy Practice Framework guides this part of the evaluation and is essential for understanding the patient’s perspective, values, and daily functioning.

During this conversation, I collect information about what the patient values. This could include spiritual activities, work, education, or roles related to family and caregiving. Understanding what holds meaning for the patient helps us tailor our interventions to align with their goals and priorities.

I also explore their general interests, which might include hobbies, time spent with friends or family, church involvement, or other meaningful leisure activities. These interests can be powerful motivators and provide structure and engagement during the intervention phase.

Next, we review their patterns of daily living and routines. I typically ask a simple, open-ended question like, “What does a typical day look like for you?” This helps uncover how they structure their weekdays and weekends, including routines related to waking up, going to work or school, taking care of children, or managing household responsibilities.

From there, we move into their work history. I ask whether they are currently employed full-time or part-time, are seeking employment, or have recently left a job. This information helps assess vocational interests and capabilities and informs intervention planning if returning to work is a goal.

We then discuss educational background, including current school attendance, past educational experiences, or future academic goals. Finally, I gather a general sense of the patient’s ability to perform ADLs and IADLs—how they manage tasks like personal care, cooking, transportation, or money management.

The insights gained during this OT profile guide my selection of a standardized assessment. Based on what the patient shares about their ADL or IADL performance, I choose an evaluation to better understand their functional strengths and challenges.

Additional Questions Asked

Some additional questions I ask during the initial evaluation help deepen my understanding of the patient’s needs, preferences, and current level of insight. One of the first questions I like to ask is, “What is your goal for admission?” While I will work with the patient to collaboratively establish formal goals, I want to hear directly from them what they feel is most important. For some, the priority may be going home as soon as possible. Others may be focused on learning new coping strategies or leaving the hospital with a stronger support system. Understanding their personal goals allows me to align our therapeutic focus with what matters most to them.

Another key question I ask is, “Why are you currently at the hospital?” or a similar version adapted to the specific setting. This question gives me a sense of the patient’s insight into their hospitalization and their understanding of the circumstances or symptoms that led to their admission. This can help inform the support and education they may need throughout treatment.

In keeping with trauma-informed care principles, I also ask about any triggers or hypersensitivities they may have. These could include loud noises, bright lights, or discomfort being around specific individuals based on gender or past trauma. If a patient identifies loud noises as a trigger, I offer them headphones or earplugs and say something like, “It can get loud here sometimes. I understand this is a trigger for you, and this is something you can use to help manage that while you're here.” This small accommodation can go a long way in supporting their emotional safety.

Lastly, I like to ask about the patient’s current coping skills. I’ll phrase it as, “What do you usually do when you’re having a hard time?” Responses vary—some may share positive coping strategies such as journaling, creating art, or taking walks. Others may disclose unhealthy coping mechanisms, like alcohol or tobacco use. Regardless of the response, these insights are valuable and help guide the assessment and the development of a person-centered, supportive intervention plan.

Evaluation Considerations

Additionally, we must consider several behavioral and observational considerations during the evaluation process. As occupational therapy practitioners, it's essential not only to gather verbal information but also to observe how our patients respond to the evaluation. These observations can provide critical insight into the patient's current functional and emotional state in a mental health setting.

One key area to observe is speech. I pay attention to the tone and rate of the patient's speech. Are they speaking very slowly? Are they hyperverbal or tangential? Some patients may present with pressured speech, speaking rapidly and often jumping from topic to topic. These speech patterns can reflect underlying mood symptoms or psychiatric conditions and inform how we proceed with the evaluation.

Mood is another important element. I always ask how the patient is feeling that day. If a patient has difficulty identifying their mood, I’ll offer a visual mood chart that displays a range of emotions, such as happiness, sadness, disappointment, or embarrassment. This often helps the patient connect with and express their emotional state more clearly.

I also observe affect, or the outward expression of emotion. I note whether the affect is flat, blunted, or labile—for example, shifting quickly from laughing to crying. These observations provide context for how emotions are processed and expressed during the session.

Patient movement is another critical indicator. I observe whether the patient appears restless, walking around the room, fidgeting, tapping a pencil, or shifting in their seat. These behaviors may be signs of internal distress, medication effects, or difficulties with self-regulation.

Eye contact is also important to consider, considering cultural differences and individual comfort levels. I note whether the patient can maintain eye contact, is highly distracted and scanning the room, or presents with an intense, fixed gaze. These cues help inform our approach and therapeutic engagement.

Finally, I assess the patient's attention to the evaluation. Can they remain engaged throughout the session, even when it becomes lengthy? If so, I note their sustained attention. Patients may require extra cues, more time to respond, or frequent rest breaks in other cases. These observations allow us to adjust the pace and structure of the evaluation in a way that supports their participation and comfort.

Standardized Assessment Considerations

Some considerations to keep in mind when choosing a standardized assessment are the patient's current cognitive level, any psychiatric symptoms potentially impacting a patient's ability to complete that assessment, such as severe psychosis or agitation, the patient's ability to participate, and willingness. Finally, we want to consider the time that we have available to meet with that patient.

After Assessment

After the assessment is completed, the next step is to document and score any standardized assessments that were administered. Once I have the results, I review them with the patient. When discussing assessment outcomes, I highlight the patient’s strengths. This helps foster a sense of confidence and partnership before addressing the areas that may need improvement or further support.

Following the discussion with the patient, I document the findings. Whether the documentation is entered into a paper chart or an electronic medical record, it’s essential to clearly and accurately reflect the assessment results, the patient’s responses, and any clinical observations. I also include recommendations based on those findings, which may relate to interventions, discharge planning, or referrals to additional services.

Finally, I share the assessment results and recommendations with the broader treatment team and other providers involved in the patient’s care. In my current practice, I typically do this the following morning during our team’s daily rounds. Sharing this information promptly and collaboratively ensures that all team members are informed and can work together to support the patient’s ongoing treatment and recovery.

Discharge Planning

After all of our assessments are complete, we begin focusing on discharge planning, which typically occurs toward the end of a patient's stay. The data gathered from these assessments plays a crucial role in shaping our recommendations for the most appropriate level of supervision and support needed after discharge. This might include suggesting home health services, outpatient follow-up, or placement in a group home, depending on the individual's functional status, safety considerations, and available supports.

In addition to guiding discharge placement, the assessment data helps us identify specific strategies to increase the patient’s engagement in daily activities. Whether that means recommending increased verbal cues, setup assistance, or other tailored supports, our goal is to maximize the patient’s independence and participation in their ADLs and IADLs. These individualized strategies ensure that patients leave our care with a plan that promotes continued recovery, stability, and meaningful involvement in their daily lives.

Different Assessment Tools

These are the four assessment tools we’ll be reviewing today, and they are also the ones I use most frequently in my practice.

The first is the Allen Cognitive Level Screen, or ACLS. This structured assessment evaluates cognitive functioning through a hands-on task involving leather lacing. It offers insight into problem-solving abilities and provides a standardized assessment of a patient's capacity to process information and follow directions.

Next is the Kohlman Evaluation of Living Skills, or KELS. This assessment focuses on various life skills and is especially helpful in determining a patient’s readiness for discharge. It assesses practical areas such as self-care, money management, safety awareness, and community mobility, making it a useful tool for recommending the appropriate level of support a patient may need daily.

The third tool is the Barthel Index for Activities of Daily Living. This assessment targets basic ADLs such as bathing, dressing, toileting, and mobility. It yields a numeric score ranging from 0 to 100, which is particularly helpful in tracking a patient’s functional progress before and after intervention.

Finally, we have the Modified Interest Checklist. Unlike the others, this is a non-standardized assessment, but it provides valuable information about the patient’s current and past engagement in leisure activities. It helps us understand what the patient enjoys, what they may have stopped doing, and where we might be able to reintroduce meaningful activities to support mental health and well-being.

Allen Cognitive Level Screen (ACLS)

The Allen Cognitive Level Screen, or ACLS, is a standardized screening tool used to evaluate cognitive functioning grounded in the Allen Cognitive Disabilities Model. The ACLS involves a hands-on leather lacing task that simulates real-life problem solving and gives us insight into how a patient may approach functional tasks.

Scores on the ACLS range from 1 to 6, with a score of 1 indicating that the individual requires total assistance and a score of 6 reflecting complete independence. This scale helps us determine the level of cognitive assistance a patient may need to engage in daily activities safely.

The ACLS is beneficial in acute care inpatient psychiatric settings, as well as in rehabilitation environments. It has been validated across various populations, including adults with dementia, schizophrenia, traumatic brain injury, and major depressive disorder, particularly when cognitive functioning is impacted.

Figure 2 shows an image of the ACLS, offering a visual reference for what this tool looks like in a clinical setting.

Figure 2. ACLS.

The OTP will instruct the patient using standardized directions to complete three progressively more difficult stitches using leather lace and the leather lacing tool. At the top of the leather piece is the first stitch—the running stitch, which is the simplest. The patient must complete three consecutive running stitches in the designated holes. We provide a demonstration and verbal instruction to guide them through this step.

Next, at the bottom and furthest from the text, is the whip stitch. This is the second level of complexity. The patient must lace over the leather and complete three consecutive whip stitches. This is often where patients make errors, such as twisting the lace. We observe whether the patient can identify and correct these errors independently. If they don’t naturally make an error, we use the leather lacing tool to introduce one intentionally, and then ask the patient to identify and fix it. This step provides valuable insight into their problem-solving abilities and response to challenges.

Finally, the third stitch at the bottom left, closest to the text, is the single cordovan stitch, the most complex of the three. Unlike the previous stitches, this one is completed without prior demonstration or instruction. The goal is to observe whether the patient can self-initiate and direct the task using higher-level cognitive skills. After a few attempts, we offer the option for demonstration and further instructions, allowing them another opportunity to complete the stitch.

These three stitches provide a clear, structured way to assess a patient’s cognitive functioning. The level of assistance needed and the ability to follow instructions or correct errors give us valuable information about the type of supervision and support the patient may require. The ACLS helps identify cognitive limitations that affect safety and functional performance, and supports decisions related to environmental modifications and discharge planning.

The ACLS scores range from 1 to 6, with decimal increments such as 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, and 0.8 to capture more nuanced levels of function. A score of 3 indicates that the patient can complete manual actions but requires supervision for safety. At level 4, the patient becomes more goal-directed and may be able to live alone with structured support. A score of 5 reflects the ability to learn new tasks with mild supervision. At this level, I feel comfortable introducing new coping strategies, such as those used in cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) or dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), because the patient can take on new learning. A level 6 score indicates complete independence with no evident cognitive impairment.

One feature I especially appreciate about the ACLS is the caregiver guide included for each score level. These guides offer clear, practical recommendations for medication management, nutrition, safety, dressing and hygiene, and money and time management. For example, for a patient scoring between 4.0 and 4.4, the caregiver must assume full responsibility for administering and monitoring medications. In terms of nutrition, meal planning, shopping, and cooking are not recommended unless close supervision and assistance are provided. I often share this guide with family members during discharge planning or family meetings to ensure they have a paper copy of the recommendations and understand the patient’s level of need.

There are some practical considerations for the ACLS. The initial cost to purchase the materials is around $250 to $300. It takes approximately 20 minutes to administer and requires minimal equipment. Although it’s not listed on the slide, it also requires minimal training to use effectively.

In terms of strengths, the ACLS has good inter-rater reliability, is highly standardized and structured, has a relatively quick administration time, and includes supportive caregiver guides, which are extremely helpful for promoting safe transitions.

Some weaknesses include the potential gap between ACLS scores and actual functional outcomes. It may not be appropriate for individuals with limited English proficiency, and studies have shown limited cultural and linguistic validity. These are important factors to keep in mind when selecting and administering this tool.

Kohlman Evaluation of Living Skills (KELS)

Next is the Kohlman Evaluation of Living Skills, or the KELS. This combined observation and interview-based assessment evaluates a patient’s ability to perform basic living skills and instrumental activities of daily living. The KELS covers multiple life domains: safety, self-care, money management, transportation, health, work, and leisure.

This tool is widely used across various settings. It is especially effective with geriatric populations, individuals in acute psychiatric units, those with cognitive impairments such as traumatic brain injury or stroke, and is also commonly used in transitional care or rehabilitation environments.

The primary value of the KELS lies in its ability to support discharge planning. It helps determine if a patient can live independently or what specific areas may require ongoing support. It includes a combination of interview questions and hands-on performance tasks, offering both qualitative and functional insight.

The first section of the KELS assesses self-care, including the patient’s appearance and hygiene routines. Patients self-report how frequently they engage in tasks such as bathing, cleansing their face, washing or brushing their hair, and brushing their teeth or dentures.

The next section covers safety and health. Patients are shown pictures of common household hazards and asked to identify what is dangerous in each image. We also assess their responses to hypothetical situations involving accidents or illness, check their knowledge of emergency services like 911 or 988, and evaluate their awareness of local medical and dental facilities.

Money management is another key section. It evaluates how a patient uses money in everyday contexts, such as making purchases and calculating correct change. The assessment includes a hands-on activity where the patient must write a check to pay a sample bill, demonstrating their ability to understand and complete basic banking tasks. We also review their income, monthly budgeting, and ability to manage financial responsibilities.

Transportation and telephone use are next. This section explores a patient’s mobility and understanding of public transportation. I ask whether they drive, use buses or trains, and how they navigate schedules or find information about transit options. Patients are also asked to demonstrate how to use a phone book—though this part can feel outdated, it still reflects their general ability to access resources.

The final section addresses work and leisure. I ask about their employment status, work history, and future vocational goals. Suppose a patient intends to find a new job, we discuss how they would search for one. In that case, acceptable answers include using newspaper ads, signage, referrals from friends or family, or visiting an employment office. The leisure section is one of my favorites, as it explores what the patient enjoys doing in their free time, especially with others, and when they last participated in those activities. This helps highlight what brings them joy and what could be reintroduced or encouraged during recovery.

Scoring for the KELS is relatively straightforward. Patients receive a score of 0 if they are independent in a given area and 1 if they need assistance. The work and leisure sections are scored as either 0 or 0.5. If an item is not applicable, it is scored as 0. Unlike the ACLS, higher scores on the KELS indicate a greater need for assistance. These results can be incredibly helpful to the interdisciplinary team in identifying the supports a patient may need after discharge, and whether a more structured living environment—such as a group home—might be appropriate.

Regarding practical considerations, the KELS costs approximately $100 to $140. It takes about 30 to 45 minutes to complete, so it’s important to account for this time when planning your daily schedule. The assessment also requires a fair amount of equipment, so it’s best to gather all materials before meeting with the patient.

As for strengths, the KELS is valuable because it covers a wide range of important daily living areas, many of which are often overlooked in other assessments. It also simulates real-world performance tasks, like writing a check, which can be highly informative. However, there are some limitations. Much of the assessment is interview-based, which means we rely on self-report rather than direct observation, particularly in the self-care section. Additionally, some components of the assessment may present cultural bias, particularly in the financial and transportation areas. Finally, a few tasks, such as using a phone book, may feel outdated and less relevant for today’s patients. Despite these limitations, the KELS remains a practical and widely used tool for assessing functional readiness and planning safe discharges.

Barthel Index

Moving on to our third assessment, the Barthel Index, this tool is designed to determine a patient’s level of functional independence in basic activities of daily living. It covers feeding, bathing, grooming, dressing, bowel and bladder control, toileting, chair transfers, ambulation, and stair climbing.

The Barthel Index is helpful across a wide range of settings and populations. It is frequently used with individuals who have Parkinson’s disease or who are recovering from a stroke. It's also well suited for rehabilitation settings, post-surgical recovery, inpatient, acute, and subacute units. One important consideration is that the Barthel Index is often best paired with a cognitive assessment to provide a more complete view of the patient's overall function. In my practice, I use it alongside the Allen Cognitive Level Screen (ACLS) to capture physical and cognitive capabilities.

There are several reasons to use the Barthel Index. It effectively tracks functional recovery and supports the development of rehabilitation goals. It can also help determine the appropriate level of care needed upon discharge, whether the patient is returning home independently, with assistance, or transitioning to a more supportive environment. One of the features I find especially helpful is how it breaks down specific areas in which a patient needs support. For example, a patient may be completely independent with feeding and score a 10 in that category, but may need assistance with dressing or bathing. Sharing this level of detail with caregivers is invaluable, as it clarifies where support is required.

The Barthel Index is also a strong outcome measure for both pre- and post-intervention. I often administer it upon admission and again closer to discharge to track functional changes and improvements, giving the care team and the patient a clear sense of progress.

Each task in the Barthel Index is scored based on whether the individual cannot complete the activity, requires some assistance, or is fully independent. The scoring varies slightly by category, but generally ranges in intervals such as 0, 5, 10, or 15 points. For example, an entirely dependent patient would score a 0 in the dressing category. If they can perform about half the task unaided, they would score a 5. If they are fully independent with tasks like fastening buttons, zippers, and laces, they would score a 10.

The total score for the Barthel Index ranges from 0 to 100. A score between 0 and 20 indicates total dependence, 21 to 60 suggests severe dependence, 61 to 90 reflects moderate dependence, 91 to 99 shows slight dependence, and 100 indicates full independence in basic ADLs.

From a practical standpoint, the Barthel Index is a very accessible tool. It’s free, requires no specialized training, and takes about 20 to 25 minutes to administer. The assessment can be completed through direct observation or by speaking with nurses, caregivers, or other staff familiar with the patient's abilities. There is no need for additional equipment, and printable forms are available online.

Regarding strengths, the Barthel Index is widely recognized and accepted across various healthcare settings. It’s valid and reliable for assessing and tracking ADL function, and its usefulness as a pre- and post-intervention outcome measure makes it a versatile tool.

However, there are some limitations. Unlike the KELS, the Barthel Index does not assess instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs). It also doesn’t evaluate cognitive functioning, so pairing it with a cognitive assessment like the ACLS is often beneficial. Additionally, there can be a ceiling effect for higher-functioning patients, meaning the tool may not be sensitive enough to detect subtle deficits in those with only mild impairments. Despite these limitations, the Barthel Index remains a strong and practical choice for evaluating and monitoring basic ADL performance.

Modified Interest Checklist

The final assessment we’ll be reviewing today is the Modified Interest Checklist. This is a non-standardized tool that includes 68 different activities. Patients are asked to indicate their level of interest in each activity, whether they currently participate in it, and whether they would like to pursue it in the future. For each activity, they can rate their interest as strong, some, or no.

The Modified Interest Checklist is applicable across a wide range of populations and settings. It is beneficial with individuals experiencing depression, schizophrenia—especially those presenting with negative symptoms—brain injury, or stroke. More broadly, it can be used in any setting where a person may need support in re-engaging with meaningful life roles.

The checklist covers a broad spectrum of interests. These include leisure activities like gardening and painting, social and community involvement such as attending church, physical and creative hobbies, and self-care or productivity roles. The variety helps us understand how a person has connected with their environment and what might motivate them to recover.

Some activities on the checklist include exercise, fishing, painting or drawing, basketball, shopping, photography, singing, home decorating, handicrafts, camping, traveling, and reading. This tool is also an excellent opportunity to build rapport. When patients share their interests, it opens the door for connection. I often respond with something like, “Oh, I really enjoy painting too—have you ever tried pottery?” Small, genuine exchanges like this can go a long way in strengthening the therapeutic relationship.

There are several key reasons to use the Modified Interest Checklist. It’s a valuable tool for gathering information about a patient’s past and current interests and their desire to re-engage in or try new activities. It supports client-centered practice by helping us identify what is meaningful to the individual, informing the development of personalized and motivating interventions. It also helps tailor goal setting and treatment sessions to align with the patient’s values and preferences. And of course, it can be a powerful tool for building rapport and motivation.

From a practical standpoint, the Modified Interest Checklist is very accessible. It is free to use, takes about 20 to 25 minutes to complete, and requires no special equipment. The checklist is readily available online and can be printed as needed.

In terms of strengths, the Modified Interest Checklist strongly supports client-centered care and individualized treatment planning. It promotes patient engagement, builds rapport, and provides valuable insight into what brings the patient joy or a sense of purpose.

However, there are also a few weaknesses to keep in mind. Because it is self-reported and subjective, the accuracy of the responses may be limited, especially for individuals with cognitive impairments. In addition, some of the activities listed may feel outdated or may not reflect newer leisure or technology-based engagement forms. Despite these limitations, it remains a meaningful and flexible tool for understanding patients' interests and guiding their recovery.

Additional Assessments

- Katz Index of Independence of Activities of Daily Living

- Milwaukee Evaluation of Daily Living Skills (MEDLS)

- Performance of Self-Care Skills (PASS)

- Routine Task Inventory (RTI-E)

- Evaluation of Social Interaction (ESI)

If you enjoyed learning about the four standardized and non-standardized assessments we covered today, several additional tools can also be helpful in mental health practice.

These include the Katz Index of Independence in Activities of Daily Living, which focuses on functional independence in everyday tasks. The Milwaukee Evaluation of Daily Living Skills (MEDLS) is another comprehensive tool that assesses skills needed for community living and is particularly valuable for individuals with serious mental illness. The Performance of Self-Care Skills (PASS) is an observation-based tool that evaluates independence, safety, and adequacy in ADLs and IADLs.

The Routine Task Inventory (RTI-E) is based on the Allen Cognitive Disabilities Model and helps assess cognitive functioning by observing daily activities. Finally, the Evaluation of Social Interaction (ESI) measures the quality of a person’s social interaction in natural contexts, making it especially relevant for clients with psychosocial or developmental challenges.

Each of these assessments offers a unique perspective on a patient's abilities and can be incorporated to complement the evaluations already discussed.

Case Examples

Now, we're going to move on to three different case studies involving patients and the assessments that we used.

Case Example #1

Our first example is Joe, a 45-year-old single male who was recently admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit due to an increase in disorganized behavior, command auditory hallucinations instructing him to hurt himself and others, and escalating paranoia. He had been living with his mother, who recently passed away. Since her passing, Joe has been noncompliant with his medications and has neglected his self-care tasks.

This gives us a clear picture of his presenting symptoms, recent environmental changes, and current functional struggles. With this information in mind, take a moment to consider what assessment tools you might use in this case.

For Joe, we selected three assessment tools. First, we used the Allen Cognitive Level Screen (ACLS), where he scored a 4.2. This score indicates the ability to complete goal-directed actions with supervision. Based on this, we recommend providing support and structure to promote safety and functioning in daily tasks.

Next, we used the Kohlman Evaluation of Living Skills (KELS). Joe demonstrated difficulty with money management, understanding how to handle emergencies, and recognizing unsafe situations, indicating the need for ongoing support in essential life skills.

Finally, we administered the Modified Interest Checklist. Joe indicated an interest in puzzles, listening to popular music, and walking. If I were currently working with Joe, I would use these interests to engage him meaningfully during his stay. For example, I might provide him with a puzzle to complete on the unit and a pair of headphones so he could listen to music—two small but significant ways to encourage healthy coping and increase participation.

From a clinical interpretation perspective, Joe’s assessment results show a decreased cognitive level, a general lack of safety awareness and problem-solving ability, and reduced insight into his condition and functional limitations.

Based on these findings, our recommendations for Joe include placement in a group home with a structured daily routine, 24-hour supervision, and assistance with medication management. We would also want to collaborate with Joe’s case manager and social worker to make appropriate referrals for outpatient therapy and day programs that can help maintain his daily structure and therapeutic engagement. Lastly, we would arrange a team meeting to review the assessment findings and coordinate a discharge plan that supports Joe’s needs and includes all necessary referrals.

Case Example #2

Moving on to case example two, we have Leanna, an 18-year-old female who recently relocated to Boston, Massachusetts, from Ireland to attend college. She was admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit after experiencing increased anxiety, panic attacks, and expressing thoughts of self-harm. With this context in mind, take a moment to think about which assessments might be most appropriate for her situation.

For Leanna, we selected the Modified Interest Checklist and the Kohlman Evaluation of Living Skills (KELS). The Allen Cognitive Level Screen (ACLS) was not used in this case, as there was no indication of cognitive impairment during the initial interaction or in her medical documentation.

Through the Modified Interest Checklist, Leanna expressed interest in creative activities such as crafts, music, and painting. During the KELS assessment, she scored as needing assistance in the areas of money management, using transportation, and accessing health services. These challenges may be related to her recent move, as she is still adjusting to an unfamiliar environment and may not yet have the support or knowledge necessary to navigate these systems independently.

Our clinical interpretation of these results indicates that Leanna is experiencing difficulty with instrumental activities of daily living, particularly in areas essential for living independently in a new city. While she expressed a desire to re-engage in creative leisure activities, she has not recently participated in them, suggesting a gap between her interests and her current coping routines.

Based on these findings, our recommendations for Leanna include occupational therapy support to help her build consistent daily routines and incorporate her preferred leisure activities—such as crafts, music, and painting—as healthy outlets for coping with stress. These interests can serve as meaningful and accessible strategies to support her emotional regulation as she adjusts to college life.

We also recommend collaborating with the treatment team to arrange referrals for additional support services, including group therapy and community programs focused on money management, understanding Boston’s public transportation system, and responding to health emergencies. Finally, we would work closely with Leanna’s social worker and case manager to ensure a referral is made to the counseling center at her college and that she receives education on the full range of mental health and academic support services available.

Case Example #3

Case example number three differs somewhat from the previous two. Hector is an 82-year-old male who was admitted to the inpatient geriatric psychiatry unit due to worsening depression and early-stage dementia. He was recently found wandering in his neighborhood without a shirt on and expressing suicidal ideation. Before this incident, Hector lived alone and reportedly managed his ADLs, but now presents as more withdrawn and disorganized.

Take a moment to consider which assessments may be most appropriate for a patient like Hector.

For Hector, we began with the Allen Cognitive Level Screen (ACLS), where he scored 3.8. This score indicates that he requires supervision for safety and has a limited ability to problem-solve. His level of cognitive functioning suggests a need for ongoing support in daily life.

We also administered the Barthel Index, and Hector scored 75, indicating moderate dependence. Specific areas of difficulty included bathing, mobility, and navigating stairs, which are essential for safety and independence in the home environment.

We used the Modified Interest Checklist to better understand Hector’s engagement in meaningful activities. He shared that he previously enjoyed gardening and reading. If Hector were my patient, I would take him to the library or book collection we often maintain on inpatient units and encourage him to select a few books to read while he's there. This simple action can help foster connection, autonomy, and emotional comfort during his stay.

Our clinical interpretation is that Hector presents with cognitive impairment that affects his ability to live independently and manage his daily routines. Although he has leisure interests, his current psychiatric symptoms and cognitive challenges are limiting his ability to engage in them.

Based on these findings, our recommendations would include placement in a memory-supported assisted living facility, where structured supervision is available. An OT follow-up should focus on supporting ADL performance, particularly in areas like bathing and mobility. A caregiver support plan should also be developed, and this is where the ACLS caregiver guides can be especially useful. These guides offer detailed recommendations tailored to Hector’s cognitive level and can be shared with the treatment team or facility staff to promote safe, supportive care.

Finally, it’s important to incorporate leisure-based interventions that are personally meaningful to Hector. If gardening and reading are interests he enjoys, participating in a gardening group while on the unit or receiving support to access similar activities after discharge can help maintain his quality of life and emotional well-being. Making specific recommendations for continued engagement in these activities after hospitalization should also be part of the discharge planning process.

Summary

This presentation reviewed four different assessment tools that are particularly useful for evaluating individuals in mental health settings.

We began with the Allen Cognitive Level Screen (ACLS), which assesses cognitive performance through a hands-on leather lacing task and helps determine the level of assistance a patient may need for problem-solving and safety.

Next, we covered the Kohlman Evaluation of Living Skills (KELS), which evaluates essential daily activities such as transportation, money management, and self-care. This makes it a valuable tool for discharge planning and determining support needs.

We then reviewed the Barthel Index, which focuses on ADL function and provides a numeric score that reflects the patient’s independence with key self-care tasks like bathing, dressing, and mobility.

Lastly, we explored the Modified Interest Checklist, a non-standardized tool that helps us understand a patient’s current and past interests, as well as their desire to re-engage in meaningful leisure activities. This can inform therapeutic and personally relevant interventions for the patient.

Takeaway

Some key takeaways are that assessments guide the OT process, including goal setting, intervention, and discharge planning, and that OT has an essential role in assessing and treating individuals in mental health settings. Finally, documentation and interpretation of assessment results are critical for effective recommendations.

Questions and Answers

Are all the assessments covered in this presentation intended for adults 18 and older?

Yes, that is correct. All of the assessments discussed today are designed for adults, primarily those aged 18 and over.

Which assessment would best support intervention development by identifying meaningful activities?

The Modified Interest Checklist is best for this purpose. It helps identify a patient’s current and past interests, which can guide meaningful and personalized intervention planning.

Has the Kohlman Evaluation of Living Skills (KELS) been updated to reflect modern technology, such as internet use for job searching or mobile banking?

Yes, there have been updates to the KELS over time to reflect current technology trends, including mobile banking and internet-based tasks. However, updates may vary depending on the version used, and some practice settings may still use older editions.

Have you ever used the CPT (Cognitive Performance Test)?

I have not personally used the CPT, but I am open to considering it for future practice.

With changes in how people pay bills, is check writing still relevant? And what about assessing the ability to get a job?

Check writing is still relevant, especially for patients who may have bills that cannot be paid online. As for job searching, responses like using Indeed or similar job search platforms are also appropriate and reflect current methods.

Are there any assessments you recommend for pediatric mental health?

Unfortunately, I have not worked in pediatric mental health settings, so I can't provide specific recommendations at this time. However, I plan to explore that area further in the future.

How frequently is a sensory assessment used in mental health settings?

While I don’t typically use a standardized sensory assessment, I do incorporate sensory strategies during safety planning. I go over the five senses with patients and explore which sensory tools help them self-regulate—for example, using sour candy during a panic attack, applying lotion to relax, or using a stress ball. These approaches are integrated informally based on the patient's needs.

Have you ever used the Independent Living Scales assessment?

I haven’t used it personally, but I’ve observed others use it and found it to be a valuable tool. It just isn’t part of my current practice setting.

Is there an effort to modernize the KELS?

Yes, efforts have been made to modernize the KELS over time. The company I work for is still using an older edition, but updated versions are available.

Have you used sensory processing questionnaires in your practice?

I haven’t yet, but I would love to incorporate them. I see value in using tools that can provide insight into how sensory processing affects function and mental health.

Do you use mindfulness or meditation in your practice?

Yes, I do. Every day at 1:00 PM, I run an exercise group that includes 20 minutes of stretches, 20 minutes of physical activity, and ends with a 20-minute mindfulness meditation. Patients often report decreased anxiety and a general sense of feeling better after participating in this group.

What assessment would you recommend for evaluating anxiety or depression?

While it wasn’t covered in today’s presentation, the Beck Depression Inventory is one option specifically for depression. If you’re interested in assessing functional impact, the KELS can also be helpful as it touches on executive functioning and IADLs. Observations and patient self-reports are also valuable tools for understanding the effects of anxiety and depression on daily life.

References

See additional handout.

Citation

Petrucci, O. (2025). Assessments in mental health. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5813. Available at www.occupationaltherapy.com