Introduction

Thanks for that introduction. Today, we are going to talk about juvenile idiopathic arthritis and our role as occupational therapists. Previously, it was called juvenile chronic arthritis or juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. The name now is juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

Synovial Joint Structure

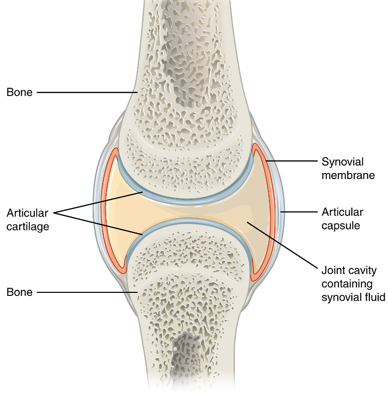

I first want to discuss the synovial joint structure.

- Synovial joints

- Two or more bone ends meet

- Articular cartilage

- Fibro & hyaline cartilage

- Articular capsule

- Subintima & intima

- Joint cavity

- Synovial fluid

- Ligaments

- Intracapsular or Extracapsular

(Armiento et al., 2019

There are three types of joints in our body. Fibrous joints, for instance, are in the skull, while cartilaginous joints are in your spine. Synovial joints are found all over the body and very affected by arthritis. An example of a synovial joint is in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Example of a synovial joint.

A synovial joint is where the two bone ends meet. On top of that bone, we have fibrocartilage, which is a bit denser. And then over the top of that fibrocartilage, there is what is called hyaline cartilage that is is a bit softer and provides more cushion to the ends of the bone. The surrounding area has the articular capsule. On the outside, there is what is called the subintima and that is a bit denser and provides a bit more structure. Finally, the intima secretes synovial fluid into this joint to provide a cushion as well as nutrition to the joint. There are intracapsular ligaments within that joint capsule and extracapsular ones that are outside of that joint capsule.

Arthritis

- Arthro=joint itis=inflammation

- Osteoarthritis

- Positive feedback loop

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Autoimmune

- Inflammation leads to:

- Joint laxity

- Obstructive bone growth

(Mathiessen & Conaghan, 2017)

The term arthritis comes from the Greek root words arthro, meaning joint, and then itis, meaning inflammation. Typically, in adults, there are two main forms, osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. With osteoarthritis, one end of the bone rubs on another. This leads to a wearing down of the cartilage. As that wears down, it creates some inflammation. As that inflammation occurs, it stretches out those ligaments, and the joint becomes less stable. This creates more rubbing in that joint, which eventually leads to joint laxity as well as obstructive bone growth due to the bone rubbing on bone. Nodules can form on the back of their interphalangeal joints due to extra bone growth and limit the amount of movement.

Rheumatoid arthritis is an autoimmune disease where the body attacks itself and creates inflammation within a variety of joints as well as other body structures, including the heart and potentially the eyes.

Now, we will talk about our topic today, juvenile arthritis.

Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA)

- A heterogeneous group of diseases diagnosed in children <16 years of age

- Autoimmune disease

- 7 subtypes

- Systemic

- Oligoarticular/Pauciarticular

- Polyarticular rheumatoid factor positive

- Polyarticular rheumatoid factor negative

- Enthesitis-related

- Psoriatic

- Undifferentiated

(Barut et al., 2017)

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis is a heterogeneous group of diseases. There are seven different subtypes, which can vary greatly depending on the subtype and child. It is an autoimmune disease diagnosed in kids under the age of 16 and the symptoms have to last for greater than six weeks.

In terms of those seven subtypes, the most severe and least common is systemic JIA. This involves the whole body where the joints are inflamed. We spoke about synovial joints, but you can also get pericarditis or myocarditis where the heart also has issues. Oligoarticular, also called pauciarticular juvenile arthritis, is when less than five joints are involved. You can have extended oligoarticular arthritis, which initially is less than five joints and then progresses to five or more. Or, you have persistent oligoarticular arthritis, which remains less than five joints.

There are polyarticular rheumatoid factor positive and polyarticular rheumatoid factor negative. These are five or more joints. One is where the client is rheumatoid factor positive and the other where the client is rheumatoid factor negative.

Enthesitis-related is when the joints themselves are inflamed and affected, as well as the insertion of tendons and ligaments into the bone. So, if those extracapsular ligaments become inflamed where they insert into the bone, as well as the tendons around the area, then that is typically labeled enthesitis-related JIA.

Psoriatic juvenile arthritis is when there is also psoriasis that comes into play. Typically with these kids, you will also see uveitis or inflammation in the eyes.

Finally, undifferentiated JIA is where they do not fit into any of those subtypes and the rheumatologist still believes it is juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

However, all that being said, the International League of Associations of Rheumatologists, or the ILAR, is currently going through a next step to make different subtypes, basically grouped into four different subtypes. Thus, these groupings may change within the next five years.

Common Symptoms

- Arthritis

- Arthralgia

- Uveitis

- Limping

- Fever

- Skin rash

- Abdominal pain

(Aoust et al., 2017)

If we look at the common symptoms of JIA, we have arthritis, which as we know, is the inflammation of the joints. We have arthralgia or pain within the joints. Uveitis, as I said, is an inflammation within the eyes. Obviously in these kids, if it is in the knees or ankles, there is going to be some limping involved, especially if it is painful. They may also have a skin rash and abdominal pain. And there are numerous other also symptoms that can present.

Etiology

- Idiopathic. However…

- Genetic factors

- > prevalence in siblings and twins

- HLA and various other gene complexes

- Environmental factors

- Bacterial infections

- Viral infections

(Rigante et al., 2015)

The etiology or the cause of the disease is idiopathic or unknown. However, the research is advancing in terms of what comes into play with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. There are genetic factors. There is also a greater prevalence between siblings and twins. The human leukocyte antigen (HLA), one of the most researched gene types, plays a role in terms of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. There are other gene complexes, but that one has been the most researched. And then, environmental factors also have a role in terms of various pathogens, bacterial infections, and viral infections.

You may hear parents of the kids you treat say that, initially, their kid had some sort of infection or fever and then after that, they developed juvenile arthritis.

Diagnosis

- <16 years of age

- >6 weeks of symptoms

- Excludes other conditions (differential diagnoses)

- No single laboratory test to confirm a diagnosis

- CRP & ESR

- X-ray, ultrasound, MRI

(Kim & Kim, 2010)

As I stated earlier, the diagnosis occurs in children less than 16 years of age, and the symptoms have to last for greater than six weeks. Typically, it is done by a rheumatologist, or better yet a pediatric rheumatologist, and they exclude other conditions in the process. For example, it cannot be septic arthritis where there is an infection in a joint and it is inflamed. It cannot be trauma-related. Fibromyalgia and hematological conditions also have to be ruled out. The difficult part about diagnosing JIA is that there is no litmus test. It takes into account the clinical presentation, the various laboratory tests, including C reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and standard radiographs like x-rays as well as ultrasound to see the joints. Lastly, if it is enthocytis-related, they may use an MRI to try to get a better image of that joint.

Epidemiology

- The average age of onset is 4.8 years of age

- The incidence rate of 5.7/100,000 for boys vs. 10.0/100,000 for girls

- The prevalence rate of 11.0/100,000 for boys vs. 19.4/100,000 for girls

- Differences also:

- Geographically (vitamin D levels)

- Racially

- Subtypes

- Gender

(Giancane et al., 2016; Harrold et al., 2013; Kuntze et al., 2018; Thierry et al., 2014)

In terms of epidemiology, the average age of onset is 4.8 years, and this is based on a systematic review. Incidents' rates are how many new cases are diagnosed per year. This is 5.7 out of 100,000 children for boys and 10 out of 100,000 children for girls. Prevalence rates are how many people have that condition at that specific time. This is 11 per 100,000 for boys and almost 20 per 100,000 for girls. Thus, it is more common in females. However, all that being said, there are differences geographically. Those living further away from the equator have lower vitamin D levels and this does play a role. Depending on the subtype, there are some that are more common in certain Caucasians or people from various parts of the world. Lastly, as stated, gender plays a role with girls being affected more than boys.

- Oligoarticular is the most common subtype

- Most common joints involved

- Knees

- Hands

- Feet

- Continues in adulthood in ~30% of patients

(Borchers et al., 2006; Harrold et al., 2013; Giancane et al., 2016; Miedany et al., 2019)

Diving in a bit further into the epidemiology, oligoarticular JIA, or less than five joints involved, is the most common subtype. This is good as it is the least severe subtype of juvenile arthritis. The most common joints involved are the knees, the hands, and the feet. The most recent research shows that it continues into adulthood in about 30% of patients. Not every patient who has juvenile arthritis will have that for the rest of their life. This is a good sign because it can give hope for parents and the child, especially in terms of them growing out of the condition.

Physical Impact

- Swelling

- Reduced physical activity

- Reduced strength

- Reduced ROM (e.g., contractures)

- Reduced function

- Reduced bone mineral density

- Muscle atrophy

(Lindehammer & Lindvall, 2004; Cavallo et al., 2014)

If we look at the physical impact of the disease, obviously, edema or swelling in the joints is a symptom. This can cause reduced physical activity because of that swelling and pain. Research is not 100% sure if it is the disease that is causing a reduction in strength, range of motion, and function, bone marrow density, or the swelling in the joints. And then, does the reduced physical activity cause further sequelae. Years ago, the thought was to go on bed rest until it got better. And now, as more research comes out, bed rest is not the prescription for these children. You want them to stay active within reason otherwise the condition worsens, and then, it is much more difficult to get them back to being a "normal" kid.

Psychosocial Impact

- Chronic pain

- Increased pain sensitivity

- Hyperalgesia

- Allodynia

- Sleep disturbances

- Reduced leisure activity

- Negative impacts on schooling

- Reduced quality of life

(Hunfeld et al., 2001; Bomba et al., 2013; Bouaddi et al., 2013; Memari et al., 2016; Learoyd et al., 2019)

There is also a psychosocial impact. The pain can become chronic. And, these kids have increased pain sensitivity as well as hyperalgesia, meaning that noxious stimuli, or something that would be painful for you and I, is more painful for these children. They may also have allodynia where something that is not a noxious stimulus is still painful for them. This is common in juvenile arthritis. When you are in pain, obviously, it is more difficult to sleep. These children experience sleep disturbances as well as a reduced participation in leisure activities due to the pain. It can also affect their schooling either from missing days or the pain affects their focus. Overall, they have a reduced quality of life because they cannot do everything as a normal kid.

- Internalizing behaviors

- Emotional difficulties/Reduced mood

- Low self-esteem

- Distorted self-image

- Anxiety

- Depression

- Externalizing behaviors

- Aggressive behaviors

- Rule-breaking behaviors

(Margetic et al., 2005; van der Meer et al., 2007; Memari et al., 2016)

Furthermore, with the psychosocial impact, these kids show internalizing behaviors as well as externalizing behaviors. Internalizing behaviors are the things that the child feels that inside, but it is less shown to us phenotypically on the outside. Emotional difficulties and reduced mood are examples. They can also have low self-esteem and distorted self-image as they are grappling with why this is happening. And then anxiety and depression can definitely occur in these children, especially if the condition is more severe. And then externalizing behaviors, you can see aggressive behaviors and rule-breaking behaviors if these kids are in pain a lot. This can lead to a short temper, as I am sure we can all appreciate.

Remission

- #1 goal with treatment is remission. Otherwise…

- Erosion of bone and cartilage

- Growth disturbances

- Joint fusion

- Malalignment

- Remission types

- clinically inactive disease

- remission on medication

- remission off medication

(Muller et al., 2015; Shoop-Worrall et al., 2017)

The number one goal with treatment is remission. Otherwise, the joints can wear down the cartilage as well as the bone, and their growth plate can also be affected. As such, there can be growth disturbances, the joints fuse, and then there will be a loss of motion. Furthermore, there can be malalignment if things become very inflamed and those ligaments can stretch out. Then, there is not as much stability in those joints.

In terms of remission types, there are three main types. There is a clinically inactive disease. This means that at that one point in time, there were no markers of the disease occurring. Second, there is remission on medication. This means that for the previous six months there were no signs of arthritis. Finally, there is a remission off medication. As opposed to six months, this is off of medication for 12 months and not active signs of the disease.

- A positive correlation between disease duration and remission

(Shoop-Worrall et al., 2017)

There is a positive correlation between disease duration and remission frequency. So the longer the child has the disease, the more likely they are to go into remission and/or experience more remissions. This is not to say that everyone is that way, but this information can help to encourage parents and patients to feel hopeful.

The OT Role

Now, we will discuss the OT role and how it interplays with treating kids with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Typically, you will not see, or at least in Canada specifically, kids who are much less severe. We are seeing kids with systemic JIA or a more severe condition.

Assessment

Assessments, in my opinion, are the key to developing an effective intervention. I will go through a few different disease-specific ones you may use for your clients.

General Assessments

- COPM

- What are the child and/or caregivers hoping for?

- F-Words in Childhood Disability

- PedsQL

- Physical, emotional, social and school functioning

- 2-18 years of age

- License fee

(Sturgess et al., 2002; Varni et al., 2002; CanChild, 2020)

First, we will start with general assessments. The COPM, or the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure, looks at main goals and what they are hoping to achieve with occupational therapy and having you there. And in terms of research, self-report assessments can be done as young as four years of age, but you just need to tailor the questions appropriately. The Can Child, out of Ottawa, Ontario, has the F-words of Childhood Disability. These are six different words that start with "F", and they can help the child come up with various goals. The F-words are function, family, fitness, fun, friends, and future. They develop a goal for each of those words. They then state a reason why they feel that goal is appropriate for them. Another option is the Peds Quality of Life Questionnaire (PedsQL), which has various components including physical, emotional, social, and school functioning. This is appropriate for kids two to 18 years of age, obviously with the two-year-olds though it is done by proxy through the parents.

Disease-Specific Assessments

- Childhood Health Assessment Questionnaire (CHAQ)

- Disability index, Discomfort index, and Health status

- 1-19 years of age

- Free for research purposes; no materials needed

- POSNA Pediatric Musculoskeletal Functional Health Questionnaire

- Disability, Pain, and Health

- 2-18 years of age

- Free; no materials needed

(Duffy, 2002; Klepper, 2003; Pouchot et al., 2004)

There are some disease-specific assessments specifically developed for juvenile idiopathic arthritis. One of them is the CHAQ or the Childhood Health Assessment Questionnaire. It has a disability index that is gleaned from the questionnaire and related to function, a discomfort index related to pain, and then a health status index. This is pertinent for children ages one to 19 years of age. If the child is less than eight years of age, it is done by proxy through the parents. It is free for research purposes and no materials are needed. The POSNA, Pediatric Musculoskeletal Functional Health Questionnaire, is from the Pediatric Orthopedic Society of North America. A variety of surgeons developed this questionnaire which encompasses disability, pain, and health. It is free, and there are no materials needed as well. This helps you to determine where the child is having issues in terms of function as well as pain, and how they are coping with the disease.

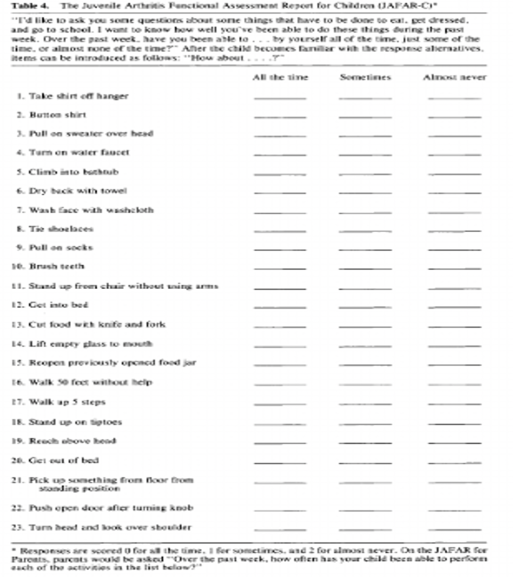

- Juvenile Arthritis Functional Assessment Report (JAFAR)

- Ability to perform physical tasks

- 7-18 years of age

- Free; No equipment needed

- Juvenile Arthritis Quality of Life Questionnaire (JAQQ)

- Motor skills, psychosocial function, general symptoms and pain

- 2-18 years

- Free; No equipment required

(Duffy, 2002; Klepper, 2003; Shaw et al., 2006)

There are also JAFAR and JAQQ. The JAFAR (Juvenile Arthritis Functional Assessment Report) is a variety of functional tasks, and the child ranks them. Sometimes, they are able to do this independently. This can help you to decide what they need help with among common household tasks. It is appropriate for seven to 18 years of age. The JAQQ is a bit more encompassing in that it assesses motor skills, psychosocial functioning, general symptoms, as well as pain. It does have a wider age range, but it is a questionnaire style.

- Juvenile Arthritis Functional Assessment Scale (JAFAS)

- Assesses ADLs considered important in children with JIA

- 7-16 years of age

- Free; Minor cost for materials

- Juvenile Arthritis Functional Status Index (JASI)

- Functional ability assessment

- 8-17 years of age

- $25 USD; no materials needed

(Duffy, 2002; Klepper, 2003; Bekkering et al., 2007)

The JAFAS, or the Juvenile Arthritis Functional Assessment Scale, are 10 tasks that the child is assessed doing. It is a bit more objective of a measure and free to use. This looks at what issues the child is having functionally and guides the development of interventions from there. Finally, the JASI, or the Juvenile Arthritis Functional Status Index, assesses functional ability for ages eight to 17 years of age. There is a cost, but there are no materials needed because it again is more of a questionnaire style.

Physical Assessment

- Number and location of joints involved

- ROM (goniometry)

- Strength (MMT, dynamometry)

- Swelling (circumferential, figure-of-eight, volumetric)

(Petersen et al., 1999; Fellas et al., 2018)

To augment the general assessments, you can have the child list which joints are painful, swollen, involved, and their condition. With systemic, it is obviously going to be a lot more. In contrast, the oligoarticular type will be a bit more focused. You are going to want to assess the range of motion, especially for the affected joints. For those of you who do not do this often, I typically ballpark the range of the joints. For example, if we are looking at the proximal interphalangeal joints, it would approximately 45 degrees, and then you could place the goniometer and read the specific number if need be (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Use of goniometer for specific measurements.

You want to ballpark it first and then put the goniometer on. In terms of strength, you can do manual muscle testing as well as dynamometry. You can use a grip strength dynamometer or a pinch strength dynamometer and see how they are doing if their hands are involved. For swelling, you can measure it circumferentially with a measuring tape or a figure-of-eight measurement depending on the joints. Another option is volumetric. You use a flask filled with water, and the child would submerge their extremity in that. The displaced amount of water would pour the end into cup off to the side, and then it would show you differences based on how much water was displaced. This can be very accurate if done correctly.

Psychosocial Assessment

- Pain (VAS, NRS, MPQ, APPT)

- Conners Early Childhood (Conners EC)

- Ages 2-6 years (fee for use)

- Child Behavioral Checklist (CBCL)

- Ages 6-18 years (fee for use)

(Jacob et al., 2014; Memari et al., 2016)

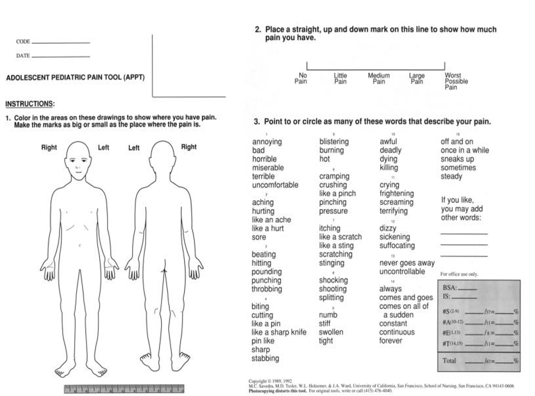

In terms of psychosocial assessments, we can assess pain. The first thing we can use is a Visual Analog Scale (VAS). The child would mark on that line where they feel their pain is, from one end being no pain to the other end being the worst pain imaginable. Usually, you use a 10-centimeter line, and then you measure where they marked on that line. One that is probably more appropriate and with faces is what is called the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS). It is a zero to 10 scale and again, those anchors are no pain or the worst pain imaginable on the other end. The faces also help, from a smiley face to a very sad face. The McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ) is for kids and teenagers 13 and over. Or, you can use the Adolescent Pediatric Pain Tool, which we will go through further in the case study. Here is an example of that in this link.

- Adolescent Pediatric Pain Tool

- Location

- Intensity

- Quality

- Temporal

Two other options are the Child Behavioral Checklist as well as the Connors Early Childhood. Both of those can help you understand if they are having issues with problem behaviors, anxiety, depression, or some of those internalizing and externalizing behaviors. Both of those can help you understand that. However, there is a fee for use with those.

Interventions: A Collaborative Process

In terms of interventions, it can sometimes be difficult as the condition is very heterogeneous. One child is not going to present as the next and your interventions will definitely vary based on the child.

Pharmaceutical Interventions

- NSAIDs

- Ibuprofen, Naproxen, Indomethacin

- Intra-articular corticosteroid injections

- Prednisone (oral corticosteroid)

- DMARDs

- Methotrexate, Leflunomide

- Biologics

- Etanercept, Infliximab, Adalimumab, Golimumab

(Giancane et al., 2016)

Even though we do not prescribe pharmaceuticals, we need to have an awareness of what these kids may be going through. First, there are nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. These are over the counter things like ibuprofen, naproxen, and indomethacin. There are also intraarticular corticosteroid injections. The goal with that is to suppress the immune system and bring down the inflammation. Prednisone is an oral corticosteroid that can help. There are disease-modifying anti-inflammatory drugs, including methotrexate as well as leflunomide. Biologics are newer. The most common one you will see is etanercept or the brand name Enbrel. Many times you will see methotrexate or etanercept used. This is typically injected every couple of weeks. And, if their juvenile arthritis is severe, they will go to the doctor every couple of weeks and have that injected.

Exercise

- Improves aerobic fitness

- Improves strength and function

- Improves self-efficacy

- Improve QoL

- Reduces disease activity

- Low-impact for 30-50 minutes, 2-3x/wk. with a focus on strength, balance, and flexibility

(Philpott et al., 2010; Kuntze et al., 2019; Klepper et al., 2019)

Exercise definitely plays a big role. As I discussed before, the initial thought with these children was to have them be on bedrest until things felt better. This is definitely not the case now. As more and more research comes out, a lot out of Holland, it discusses exercise. Although it is not fully determined what the right dosage and frequency are, most research is suggesting low impact for 30 to 50 minutes at a time, two to three times a week, with a focus on strength, balance, and flexibility. Research on aerobic exercise, like jogging, riding a bike, etc. is not as strong. This makes sense if children's joints are stiffening and they are having muscle atrophy. Improving fitness, strength, and function also improves self-efficacy and quality of life. These kids can play with their peers a bit easier, and it actually reduces disease activity. This is something to educate parents on as well as a child. If it hurts a lot, obviously at that time, you want to get the pain down, but exercise is definitely a good thing. Sitting and not doing anything is not the best option.

Orthotic Interventions

- Medication has greatly improved in the last decade, reducing the need for an orthosis.

- Most splinting research relates to the wrist and knee, with conflicting evidence

- Splinting after a cortisone injection

- Serial casting for PIP joint contractures

- Children may be resistant to wearing splints due to social stigma

(Helders et al., 2002; Schroder et al., 2002; Wallen & Gillies, 2008; Dunbar et al., 2016; Ugurlu & Ozdogen, 2016; Naz et al., 2018)

Occupational therapists know orthotics well. Before biologics and disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs, orthotic interventions were more commonplace. Now that pharmaceuticals are working a lot better for these children, orthotic intervention is not as necessary in a lot of cases. All that being said, the splinting research is somewhat conflicting. Some of the research has shown splinting after a cortisone injection to be beneficial for reducing inflammation, improving function, and improving pain. While other research has shown increased stiffness and pain after splinting. If I were to recommend what you would do as a therapist, I would say to discuss it with the child and the parents. If the child does not want to wear it, then obviously it is a moot point. However, if you feel it will be beneficial, you need to monitor the splint and its effectiveness regularly.

Older research looked at serial casting, especially for the proximal interphalangeal joint. You would cast it to try to straighten it out. This did work well, but it is now not as common. Now with pharmaceuticals, the goal is to not allow joint contractures to occur.

Adaptive Aids

- The goal with adaptive aids to reduce pressure on the affected joints and ideally shift the load to larger or more joints

- Extended comb handles/long handled bathing sponge

- Adaptive eating utensils (e.g., thicker spoon handles)

- Shoehorn

- Velcro on clothing and/or shoes.

- Elevated toilet seat

- Wheelchairs

- Writing aids

- Dycem

(Cakmak & Bolukbas, 2005)

The goal with adaptive aids is to reduce the pressure on the affected joints and ideally shift it to larger joints or more joints. Another goal is to make things easier. For example, if there is a reduced range of motion at the shoulder, then we may not want the child to have to lift up as high. We have them use a step stool or lower whatever they are reaching up for like clothes hanging in their closet. There are a variety of options. There are extended comb handles to help them with combing their hair if it is painful. Adaptive eating utensils can be helpful so that they do not need to make as tight of a fist. Shoehorns can help if they are having trouble bending over at the waist. Velcro, as we know, will make it a bit easier with fasteners if their hands are affected. Elevated toilet seats can be helpful if their knees are an issue. Wheelchairs are rare, but they may be necessary, even if it is intermittently or to go for longer distances. Writing aids can help with grip. Lastly, Dycem can make things "grippier" and easier to handle.

Psychological Intervention

- Evidence for psychological interventions in JIA is conflicting. However,

- Better outcomes for children with low quality of life compared to a high quality of life

- Better outcomes with peer-support groups relative to individual-based therapies

- Types of interventions researched:

- Mind-body interventions

- Cognitive-behavioral interventions

- Peer-support interventions

(Fuchs et al., 2013; Cohen et al., 2017; Waite-Jones and Swallow, 2018)

In terms of psychological interventions for juvenile arthritis, there is conflicting evidence. Better outcomes are shown in children who are affected more by the disease so there is somewhat of a ceiling effect. That is if a child does not really have many psychosocial issues, then an intervention is not going to be as necessary. Whereas, those kids who are a lot more affected and where psychological intervention may be more necessary, this obviously should help them more. There are also better outcomes with peer support groups. You will hear a lot of these kids say that they do not have as many friends or know many people with the condition. It is important to them to meet other children with this condition so they feel more normal.

The types of interventions shown in research are things like yoga, meditation, and cognitive-behavioral interventions. This is where you try to reframe the child's thinking about things, which in turn should influence their behavior. Peer support interventions, which as I said, are typically described as important for these children.

Case Study

Liam

- 8-year-old boy

- Significant fever 18 months ago that persisted and began getting significant pain along with significant fatigue and reduced function.

- Diagnosed 1 year ago with systemic JIA

- Currently on biweekly injections of Enbrel and oral Naproxen 2x/day

Liam had a significant fever 18 months ago that persisted. He began getting significant pain, as well as fatigue and reduced function. He went to a pediatric rheumatologist and was diagnosed with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis, about a year ago. Currently, he is doing biweekly injections of Enbrel, or etanercept, and he takes oral naproxen (Aleve) twice a day.

Assessment

- F-Words of Child Disability

- JAFAR

- ROM measurements

- Pain

In terms of my assessment for Liam, I picked four different assessments. The majority of intervention will be based on a client-centered approach.

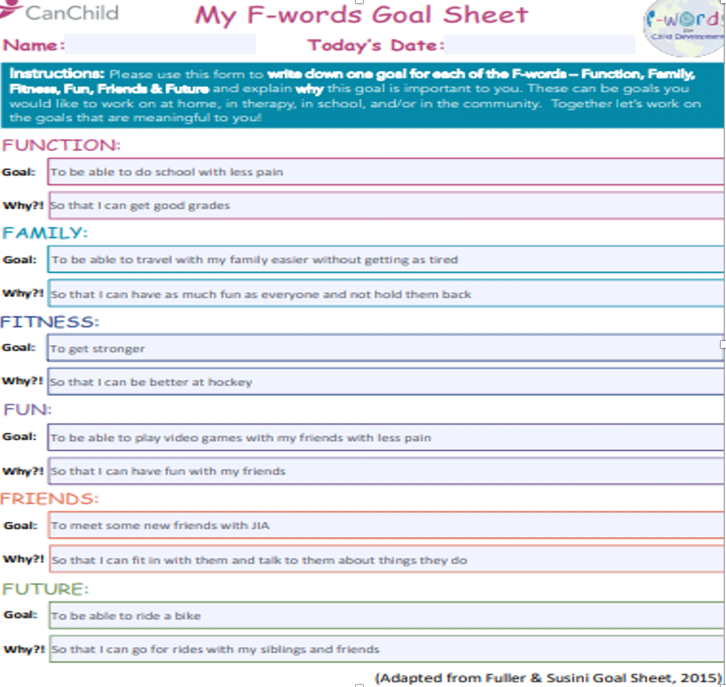

F-Words of Child Disability.

The six areas that he wanted to improve are listed below in Figure 3.

Figure 3. His responses to the F-Words (https://www.canchild.ca/en/research-in-practice/f-words-in-childhood-disability/f-words-tools). Used with permission from Can Child, 2020.

You can find this on the website. It is also translated into a variety of other languages as well. For function, he wanted to be able to do his schoolwork with less pain as he wanted to get good grades. In terms of family, he wanted to be able to travel with his family a bit easier without getting as tired. For fitness, he wanted to get stronger. As he was a hockey player, he wanted to improve his strength. In terms of fun, he wanted to be able to play video games with his friends without as much pain. Often, his hands would hurt after playing. He also wanted to meet some new friends with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Lastly looking into the future, he wanted to be able to ride a bike.

JAFAR.

This is the JAFAR in Figure 4.

Figure 3. JAFAR assessment. (Howe et al, 1991; Used with permission from Arthritis Care & Research)

It may be a bit hard to read as I had to take it off their publication. They gave me permission to do so. It has 23 different functional tasks. The child answers whether they can do these all the time, sometimes, or almost never. These tasks range from taking a shirt off a hanger, getting into bed, or walking up five steps. I find this useful as it can help you to determine how to set up the environment differently to allow the child to succeed. If they are only having issues with a few of these tasks, then you only have to focus on those. For Liam, due to his condition being more systemic, he had issues with a lot of them. We had to provide adaptive aids to help him with some of these tasks.

ROM.

- Joints with potential limit or pain

As I discussed, you need to ballpark where you think the movement is and then measure from there, especially if these children are having stiffness. If there are no issues with stiffness then it can be as simple as talking to the child, talking to the parents, and observing the joints. It is also important to note when and at what range the child is having pain and give strategies accordingly. It may be as simple as doing long duration stretching to allow the ligaments to stretch out a bit more and using fewer quick movements. They can also warm the area up beforehand. For example, they could bathe in the morning to loosen up the joints and then complete range of motion exercises.

Pain.

- Adolescent Pediatric Pain Tool

- Location

- Intensity

- Quality

- Temporal

In terms of pain, so the adolescent pediatric pain tool can be used.

Figure 4. APPT.

On one side, you have an image of the body front and back, and the child can select where their pain is. They can also select the intensity on that numeric rating scale and the quality of pain. There are a variety of descriptors that they can choose to describe their pain. There is also a way to document the temporal pattern to pain. Is it all the time? Does it come and go? These various descriptors in the assessment can help you to understand what this child is feeling as well as help you understand pre-post or mid intervention. Are they feeling better now? Is the pain less severe? Is it less often?

Interventions Based on the F-Words

As I said before, it is important to base our interventions on the F-words and goals. Here is a sampling of goals for Liam.

- 1.Schoolwork

- Speech-to-text

- Scheduling breaks/More time for assignments

- 2.Traveling with family

- Bathing in mornings to warm up/loosen joints

- Adequate time between activities

- Wheelchair

Liam decided that he wanted to improve his schoolwork. One option could be speech to text. He could also schedule breaks and allow more time for his assignments. This could be included in an IEP. A computer would also be helpful to reduce the amount of writing. doesn't have to write repeatedly.

Traveling with family was another goal. Bathing in the morning could help him to loosen up his joints. Additionally, he would need adequate time for activities. Not rushing from one activity to the next can definitely help him. This is part of our joint protection principles. He could also use a wheelchair for long-distance excursions.

- 3.Gain strength

- Education on the benefit of an exercise program targeting strength, flexibility, and balance

- 4.Video games with friends

- Adaptive controllers

- Varying styles of games

- Gross motor games (Nintendo Wii)

- Fine motor games (Xbox, Playstation)

In terms of interventions, he wanted to gain strength. I think a lot of our role is to educate that exercise is not harmful to these children, and it definitely is necessary. Activities like swimming or biking can definitely be beneficial to increase strength, flexibility, and balance.

He wanted to be able to play video games with friends longer. X-Box and Microsoft make adaptive controllers. He could also vary the styles of games that he is playing. For example, if he was playing something more gross motor like a Nintendo Wii, he might want to switch to something more fine motor next time. It is better to not do the same thing repeatedly as it can put a lot of load on certain joints.

- 5.New friends with JIA

- Organize a peer support group

- Education on various camps

- https://campcambria.org/ (Minnesota & Ontario)

- 6.Riding a bike

- Continue with strengthening

- Educating parents that activity will not harm the child

- Adaptive aids if necessary (e.g., electric bike, higher handlebars, thicker handlebars, etc.)

The next goal was to meet new friends also with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. We could help him to find peer support groups and camps.

Camp Video

Here is an example of a camp.

I hope you guys enjoyed the video. It is so important to let these kids know that they are not alone and that there are a variety of options in terms of them meeting other children.

Finally, Liam's last goal was riding a bike. We continued with the strengthening, balance, and flexibility as it would be beneficial to this bike riding goal. Again, educating the parents that activity is not going to harm the child and providing adaptive aids if necessary are crucial. For example, if he has issues with his low back and cannot bend as far forward without pain, raising the handlebars might help. If he cannot push as hard through the pedals without pain, perhaps an electric bike would be better. Thicker handlebars are definitely an option if the child cannot make as tight of a fist.

Summary

To wrap up, JIA is a very heterogeneous condition. Thus, you have to base treatment off the child, and as OTs, we definitely know that as we are holistic and client-centered. You also need to know what subtype it is and the occupational performance issues they are having.

Thanks for listening.

References

Available in the handout.

Questions and Answers

Have any of your clients gone to that camp?

No, I do not have any. The camp is based in Ontario, and I work on the other side of the country, out in British Columbia.

What is the positive correlation between disease duration and remission frequency?

The longer the child lives with the disease, the more likely they are to go into remission, whether it is once or the second time. Early on, if the child is diagnosed with the disease, they are less likely to experience remission. However, the more that time goes by, they are more likely to experience remission. This is hopeful for parents as well as the child because there is a greater likelihood that things will improve. All that being said though, some people have the condition for the rest of their life. While it is not 100%, there is definitely a positive correlation.

How do you recommend promoting and advocating for OT's role in JIA? From personal experience, rheumatologists are more likely to refer clients for PT services than OT services?

Yeah, I definitely agree on that end. I mean the exercise role is where a lot of the research comes in. Definitely I can see pediatric rheumatologists or rheumatologists referring to PT. However, we know adaptive aids well. And in terms of an all-encompassing approach, I think this is our area. It would be something to discuss with rheumatologists and doctors to educate them that children are not just affected physically. There are the psychosocial components that we are more likely to treat. You can advocate for the OT role in your area. I know in Canada in my area, we have what is called the Mary Pack Arthritis Center. They have both a PT and an OT on hand. They are weirdly divided in the sense that the upper extremity goes to the OT and the lower extremity goes to the PT, aside from the feet. If you are in a similar setting, you can advocate a bit better.

What is the difference between polyarticular rheumatoid factor positive and negative?

Polyarticular is five or more joints, as opposed to oligoarticular or pauciarticular. In terms of rheumatoid factor positive and negative, it is a blood test. Does this child demonstrate that the rheumatoid factor is positive or are they rheumatoid factor negative? So if there are more than five joints involved and their blood work does not show anything, then they are going to be grouped under that polyarticular rheumatoid factor negative. Whereas, if there are more than five or more joints involved and they are rheumatoid factor positive, then they will be grouped under that. But again, these categories are changing a lot.

References

Available in the handout.

Citation

Loesche, S. (2020). Work from wherever: Ergonomic tips for a safe & healthy workstation set up at home. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5333. Retrieved from http://OccupationalTherapy.com