Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Living with Heart Failure: The OT Role, presented by Camille Tovera-Magsombol, OTD, OTR/L.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to state the pathophysiology of and functional limitations from heart failure.

- After this course, participants will be able to identify key areas to assess and address on individuals with heart failure.

- After this course, participants will be able to identify self-management strategies to promote optimal living of individuals with heart failure.

Heart: Anatomy and Physiology

Thank you, everybody, for taking the time to listen to this webinar today. Today, we are going to tackle heart failure in three different ways. First, we will discuss the normal physiology and pathophysiology of heart failure. Then, we will discuss a way to assess or look at our heart failure patients to guide our treatment and highlight the importance of goal setting in the context of lifestyle modification and self-management. Lastly, we will discuss self-management for heart failure and how as occupational therapists, we can contribute much to this aspect.

Structures

- Atria

- Upper chamber

- Left and right

- Ventricles

- Lower chamber

- Left and right

- Septum

- Separates the left and right sides of the heart

- Participates in conductivity and ventricular contraction

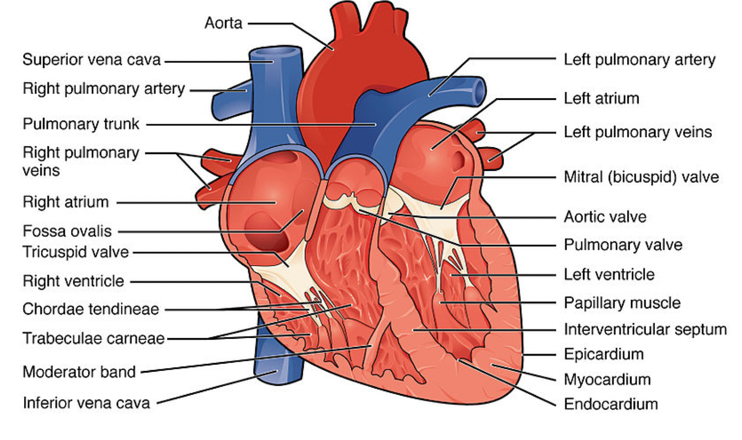

We all know that the heart has four chambers, and there are left and right sides. The upper chambers are the atria, and the lower chambers are the ventricles. The septum separates the heart into a left and right side, and there are valves.

- Atrioventricular Valves

- Tricuspid: R atrium and R ventricle

- Mitral: L atrium and L ventricle

- Semilunar Valves

- Pulmonary: R ventricle and pulmonary artery

- Aortic: L ventricle and aorta

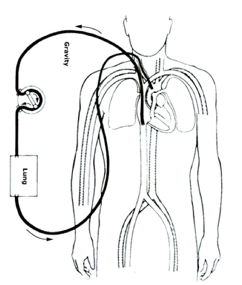

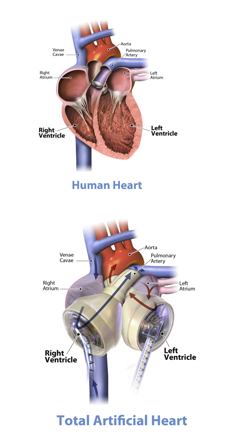

The valves allow the heart to fill with blood. Figure 1 shows a schematic of how the blood goes throughout the rest of our body.

Figure 1. Heart structures. Image from OpenStax: Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

As you can see, our lungs and our heart are interrelated. If something is wrong with the lungs, it can affect the heart. Consequently, if there is something wrong with the heart, it can eventually involve the lungs.

Circulatory System

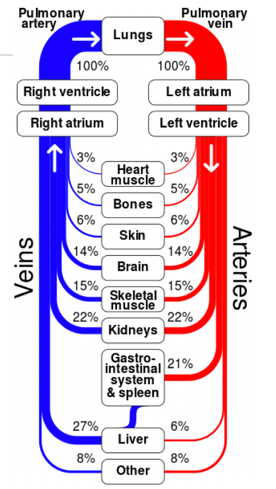

Figure 2 is a Sankey diagram of how blood is distributed to different body parts. You can see in this diagram how the body distributes blood to where it is needed the most.

Figure 2. Sankey diagram showing circulation to different parts of the body. (Cmglee, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons)

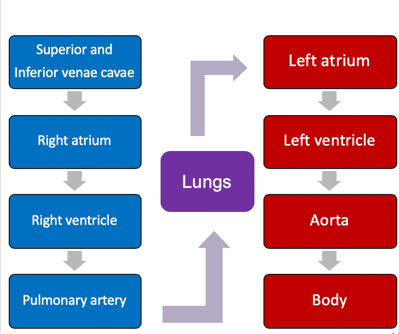

For example, the circulatory system can shift blood to the skeletal muscles instead of other body parts when exercising. Below is another diagram to represent blood flow (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Circulation diagram.

Heart Failure: Definition and Pathophysiology

Definition

- The inability of the heart to meet the body's metabolic needs (Cassady & Cahalin, 2011)

- The heart cannot fill chambers with enough blood.

- The heart cannot pump blood to the body effectively (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, n.d.)

- Not all patients with HF are congested (Yancy et al., 2013)

- Complex clinical syndrome vs. a diagnosis

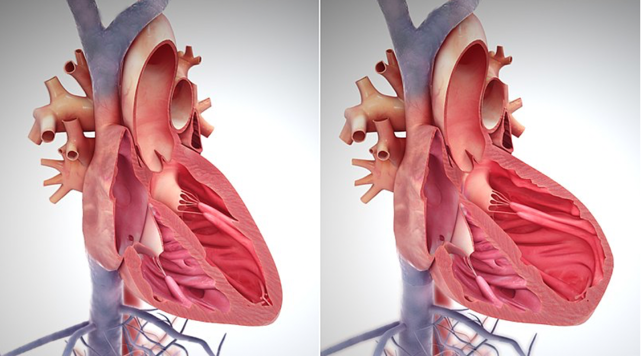

Heart failure is an inability of the heart to meet a body's metabolic needs. The heart cannot fill the chambers with enough blood or pump blood to the body effectively. It is also essential for us to realize that not all heart failure is congestive. There is also an issue where the heart can get so stiff that it cannot relax enough to receive the blood. Therefore, you do not have enough blood to send to the rest of the body. We should also consider heart failure as a clinical syndrome versus a diagnosis. It is a clinical picture that lets the clinicians decide whether it is heart failure. Figure 4 is just a depiction of what heart failure would look like after remodeling.

Figure 4. Heart failure after remodeling (Wikimedia commons).

In the left picture, the left ventricle is small and efficient in pumping out that blood. And over time, because of heart failure, it will adapt by making the heart muscles bigger, and therefore, inefficient in performing or meeting its function (right side pic).

Prevalence

- 5.7 million adults

- HF contributed in 1 in 9 deaths in 2009

- 50% of people who develop HF die within 5 years

- Mozzafarian et al., 2016

- $30.7 billion each year (health care services, medications to treat HF, missed workdays)

- Heidenreich et al., 2011

We all know that heart failure is prevalent and costs a lot, as seen by the numbers above from the research.

Signs and Symptoms

- Dyspnea (exertion, paroxysmal nocturnal, orthopnea)

- Fatigue/weakness/lethargy (HF-induced skeletal muscle abnormality)

- Physical: elevated jugular venous pressure, pulmonary rales, lower extremity edema, abdominal distention)

- Right hypochondrial pain (2/2 to R-sided HF)

- Exertional chest pain

- Activity intolerance

- All HF patients report dependence on at least 1 activity.

Dyspnea and fatigue are the most common signs or presentations of heart failure. There also can be fatigue, weakness, and lethargy because of a heart failure-induced skeletal muscle abnormality. You will also see your patients having exertional chest pain or activity intolerance. All heart failure patients will report at least dependence in one ADL or activity. They could also present with right hypochondrial pain secondary to right-sided heart failure.

- Cognitive impairment: 25-80%

- Acute and fluctuating: delirium (decompensated HF)

- Chronic: subjective cognitive decline, MCI (most common), mild neurocognitive disorder, dementia (stable HF)

- Language

- Attention, executive function, psychomotor speed

- Visuospatial skills and memory may recover if HF is well-controlled (Cannon et al., 2017)

- Low health literacy is associated with higher all-cause mortality and a barrier to effective disease self-management; it is a modifiable risk factor for poor disease outcomes.

Another interesting fact is that 25 to 80% of our patients will also have cognitive impairments. There have been a lot of studies about how having heart failure can lead to cognitive impairment. It could be acute and fluctuating, such as delirium, especially if your patient has decompensated heart failure. Or, it could be chronic. They can have a subjective cognitive decline or a mild cognitive impairment, which is the most common. They could also have a mild neurocognitive disorder or dementia. Language is also affected. And with language, you would see that over time, this would decline. Attention, executive function, and psychomotor speed are also affected. There is also evidence that visuospatial skills and memory can recover if heart failure is well-controlled. Thus, it is essential to help our clients to control their heart failure as it will promote improved cognitive skills. Low heart literacy is associated with heart failure as well. And it is associated with higher all-cause mortality. So, it is essential for us also to screen and look into our patient's health literacy.

- Depression and Anxiety:

- Depressive symptoms: 21.5%

- Anxiety: 13% anxiety disorder and 30% clinically significant levels of anxiety

- Rutledge et al., depressive symptoms or depressive disorder 2x increase of death or cardiac events

- Biological and behavioral mechanisms may explain the association between depression and anxiety and poor HF outcomes.

- Screen with PHQ-2 and then use PHQ-9 for the positive screen (Celano et al., 2018)

Depression and anxiety are also documented with heart failure. As many as 21.5% of patients with heart failure exhibit depressive symptoms. Thirteen percent will have anxiety disorders, and 30% will test positive for a clinically significant level of anxiety. Researchers recommend that when we see patients with heart failure to use the PHQ-2 (Patient Health Questionnaire). Then, if they screen positive using the PHQ-2, they recommend using the PHQ-9 to explore their anxiety and depression further.

Risk Factors

- Coronary heart disease and heart attacks

- High blood pressure

- Diabetes

- Smoking

- Eating foods high in fat, cholesterol, sodium

- Sedentary lifestyle

- Obesity

[Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2019]

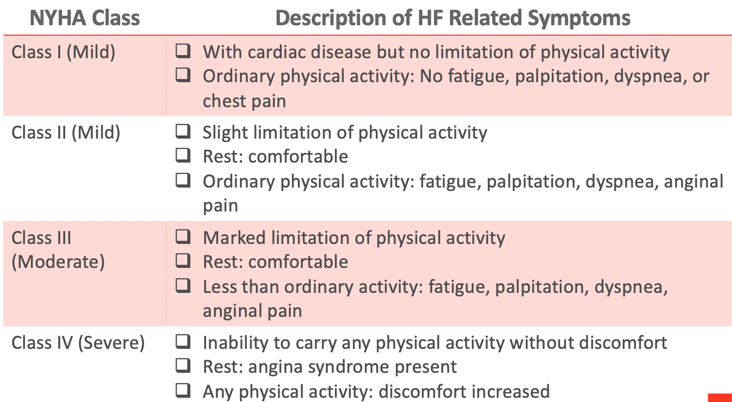

As we discussed earlier, heart failure does not just happen by itself. Heart disease, smoking, a sedentary lifestyle, obesity, heart failure, and other heart insults, such as a heart attack, usually trigger it. There are different ways that clinicians classify patients with heart failure, including the New York Heart Association Functional Classification in Figure 5.

New York Heart Association (NYHA) Functional Classification

Figure 5. NYHA Functional Classification.

In this one, they are looking into a person's ability to tolerate physical activity, rest, and what happens to them when they complete ordinary activities such as walking, sitting, or going to eat. They classify them according to mild, moderate, and severe.

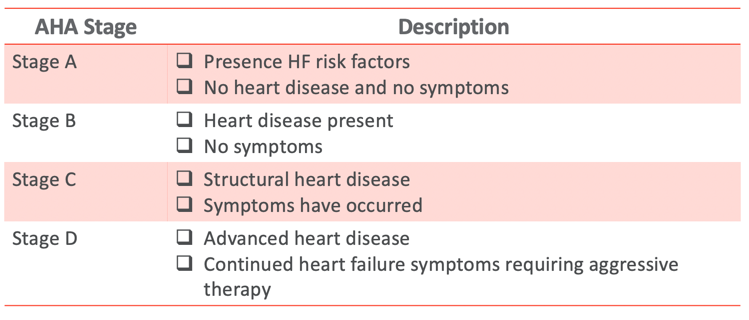

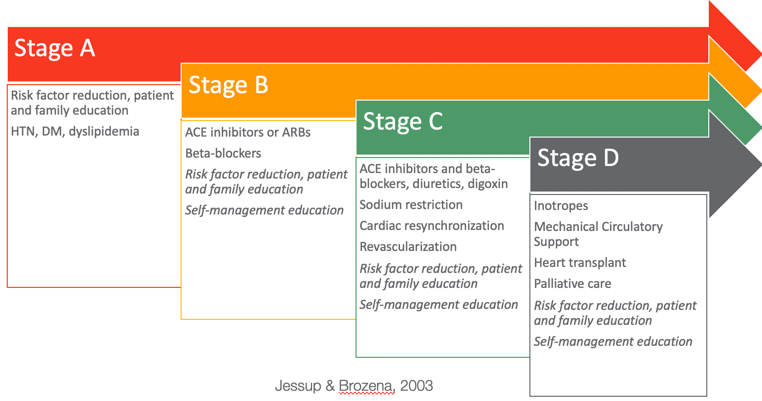

American Heart Association (AHA) Heart Failure Stages

Figure 6. AHA Heart Failure Stages.

The American Heart Association also classifies them by different stages. Stage A would be risk factors for heart failure, but no heart disease or symptoms exist. For example, one of the risk factors is hypertension. We all know that with chronic hypertension, there can be structural damage in the heart.

Compensated Vs. Decompensated

Heart failure could also be compensated or decompensated (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Compensated vs. decompensated. (Jessup and Brozena, 2003)

We should note that decompensated heart failure is a medical emergency and should be treated immediately. Compensated heart failure is medically stable. This is where the heart has adapted. You will see a ventricular enlargement and activation of the sympathetic nerves in the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system.

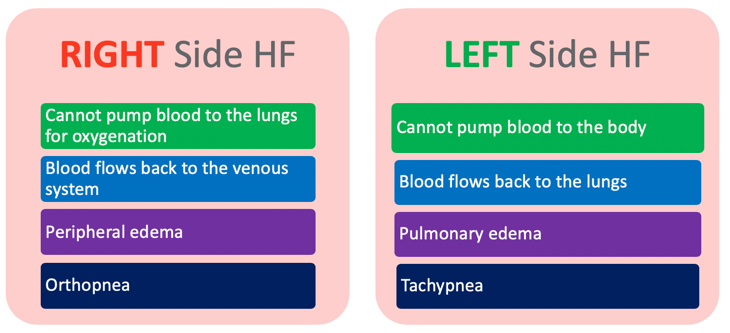

Left-Sided Vs. Right-Sided HF

Figure 8. Left-sided vs. right-sided.

Heart failure could also be left-sided or right-sided. With right-sided heart failure, the heart cannot pump blood to the lungs for oxygenation, whereas left-sided heart failure cannot pump blood to the rest of the body. The right side of the heart receives blood from the body. So now, the blood flows back to the venous system, which is why you will see peripheral edema. You will also notice some orthopnea or difficulty breathing when lying down flat. With left-side heart failure, the blood flows back to the lungs. For this, you will see more pulmonary edema. And since the blood flows back and the whole system is inefficient, you will see that they will also be breathing a little bit faster.

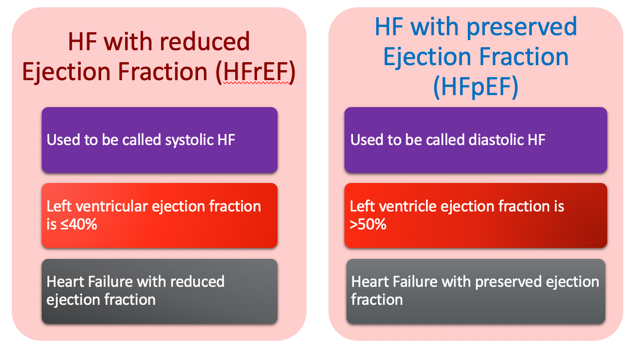

Reduced Ejection Fraction Vs. Preserved Ejection Fraction

When classifying heart failure based on ejection fraction, they mainly look at the left ventricle because they are looking at how much blood the heart can pump to the rest of the body (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Reduced EF vs. preserved EF.

So, they have what they call a reduced ejection fraction and a preserved ejection fraction. The one with reduced ejection fraction used to be called systolic heart failure, and the one with preserved ejection fraction was diastolic heart failure. With a reduced ejection fraction, your left ventricle can only eject less than or equal to 40% of the blood it receives. With the preserved ejection fraction, it is normal. The average ejection fraction is between 50 to 70%. The 41 to 49% range is considered borderline reduced ejection fraction.

Medical Management

How do our healthcare practitioners usually manage?

Goals of Treatment

- Improve prognosis and reduce mortality

- Relieve symptoms and reduce morbidity

- Reduce the length of stay and readmission

- Prevent organ system damage

- Manage comorbidities that lead to poor prognosis

The goals of treatment are to improve prognosis, reduce mortality, relieve symptoms, and reduce morbidity. We also want to reduce the length of stay and readmission. We want to prevent organ system damage and manage comorbidities that lead to poor prognoses. As therapists, you can immediately see how we can contribute to helping meet all these goals.

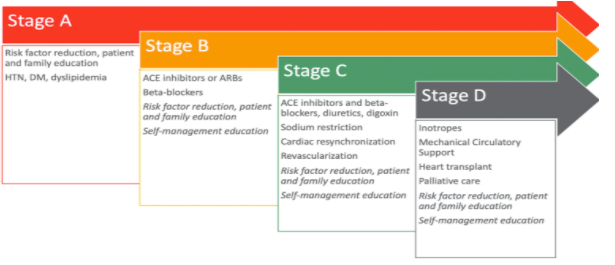

Manage the Stages of HF

Going back to the AHA classification and the stages of heart failure, you can see that they have also recommended how to manage each stage of heart failure (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Ways to manage different stages of heart failure.

In Stage A, they recommend risk factor reduction and patient and family education. Stage A represents those patients that do not have structural defects in their hearts but have risk factors for heart failure. In this stage, you would want to educate them and their families on reducing their risk of developing heart failure. It is also good to note that we are critical in this stage of the game as much of this education is abstract, like lowering sodium, increasing physical activity, etcetera. Sometimes our patients wonder how they will adapt or modify their lifestyle to fit their current routine. In Stages B, C, and D, you will also see that I have added both "risk factor reduction" and "self-management education" in italicized text. This is because these will be helpful in all stages of heart disease. There will be structural defects in Stage B, although not many symptoms. However, you will still want them to manage their illness, so they do not progress to C and D.

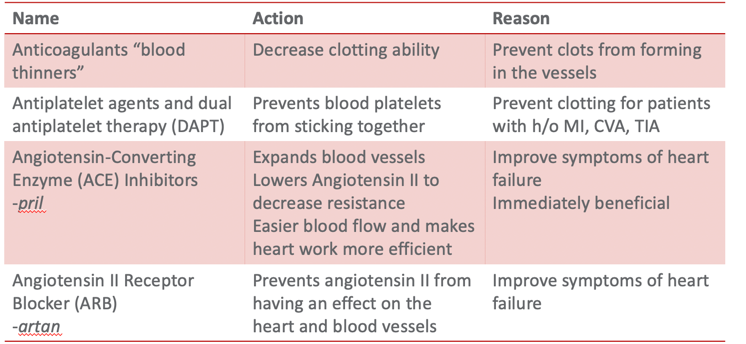

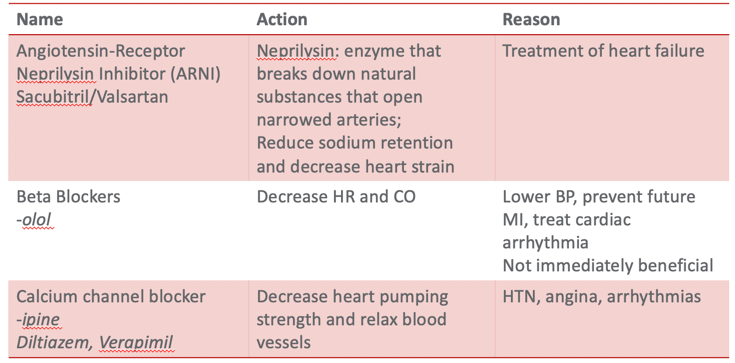

Medications

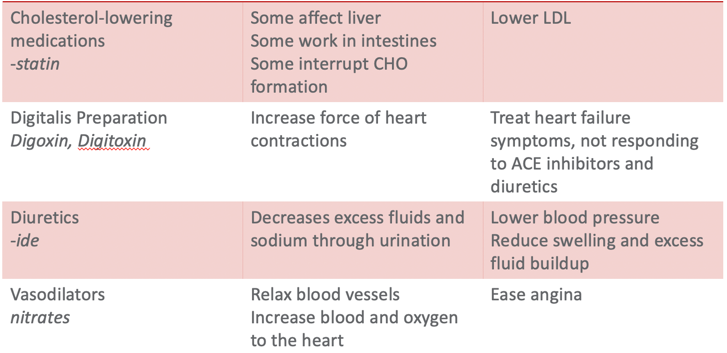

The following chart shows the name of medications and their actions and reasons for using them for heart failure management (Figure 11).

Figure 11. Types of medications used for HF.

When you have a heart failure client, you may note that they take a lot of medications. Medication management is a massive part of a heart failure patient's disease management. I have compiled a list of commonly prescribed medications for patients with heart failure. This list is also accessible from the American Heart Association website, heart.org. Pharmacologic therapy aims to improve the symptoms, slow or reverse the deterioration of myocardial function, and reduce mortality. Research has examined why many heart failure patients do not take their medications. Many feel like the drugs are not effective. Familiarizing with the medication type, routine, and action will help educate our patients. For example, ACE inhibitors can have an immediate effect meaning your client would almost immediately feel like they could breathe better. But if they are prescribed beta-blockers, the results are not immediate. It takes effect around 30 to 60 days after they start taking it. This information is helpful to review with your patients. "You should keep taking it as the effect will be long-term versus short-term." There are not many management options for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction where the ventricle is stiff and unable to receive blood.

Management of Associated Conditions

- HTN

- Lung disease

- CAD

- AF

- Obesity

- Anemia

- Diabetes

- Kidney disease

- Sleep-disordered breathing

Often, a client with HF does not have an excellent quality of life. Most treatments focus on managing the associated diseases, hoping they do not progress further.

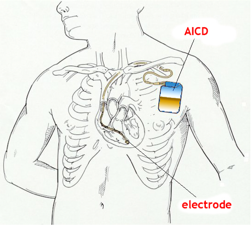

Minimally Invasive Devices

One of the things for managing heart failure patients, especially patients with reduced ejection fraction, is a minimally invasive device such as a pacemaker or an automatic implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, or AICD.

Figure 12. Example of a pacemaker (An artificial pacemaker from St. Jude Medical, with an electrode. Steven Fruitsmaak, 2007 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:St_Jude_Medical_pacemaker_in_hand.jpg).

Figure 13. Example of an AICD (Automatic implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:AICD.jpg).

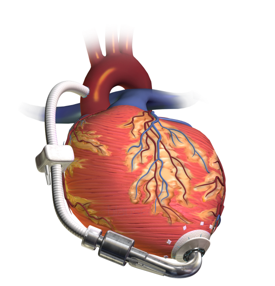

Mechanical Circulatory Support

If they progress further, they will be prescribed mechanical circulatory support. Some of you may be familiar with the ventricular assist device (VADs) and the total artificial heart. Medical therapy, cardiac resynchronization therapy, and AICDs really can help improve the survival of many with heart failure and reduce ejection fraction. But, you will also have this group that will benefit from mechanical or circulatory support devices (Figure 14).

Figure 14. Examples of mechanical circulatory support (Veno-arterial (VA) ECMO-Van Meurs, K, Lally, KP, Peek, G, Zwischenberger, Extracorporeal Life Support Organization, Ann Arbor 2005. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Veno-arterial_(VA)_ECMO_for_cardiac_or_respiratory_failure.jpg; Left Ventricular Assist Device-https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Blausen_0621_LVAD.png; Graphic of the SynCardia temporary Total Artificial Heart beside human heart with call-outs. Jumpingree1992-https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Graphic_of_the_SynCardia_temporary_Total_Artificial_Heart_beside_a_human_heart.jpg).

There are generally four indications for getting these. The first is a bridge to transplant, where they are waiting for a heart, or a bridge to a decision, whether they will qualify for a heart transplant. Another is a bridge to recovery. Some studies have shown that the heart can adapt and survive after being provided with an assistive device. It can be a bridge to a destination. This means that when the device fails, then the patient will pass. We are in the third generation of VADs, which use centrifugal pumps and have more extended durability. They are smaller and more compact. And their system is optimized to minimize thrombus formation and hemolysis. Durability is anticipated to be between five to 10 years, but they are not yet sure as they have just recently released this. They are currently monitoring to see how long VAD patients will survive. Some experts prefer a total artificial heart over the VAD for patients with preserved ejection fraction. However, technology is also relatively new, and experience is limited. I guess the jury is still out as to which one is better.

Heart Transplant

- Indications

- A refractory cardiogenic shock that requires an intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) or a left ventricular assist device (LVAD)

- A cardiogenic shock that requires continuous intravenous inotropic therapy

- Peak VO2 less than 10mL/kg per min

- NYHA class III or IV

- Recurrent life-threatening L ventricular arrhythmias

- End-stage congenital HF with no pulmonary HTN

- Refractory angina

A heart transplant is the gold standard for treating patients with end-stage heart failure. The outcomes are good. They see 75% of patients after three years live without limitations or have minimal to no symptoms. At five years, 45% of people with heart failure can go back to work at least part-time. They have also measured their exercise capacity, which is almost equal to that of healthy individuals after participating in an exercise program. However, the biggest drawback of heart transplantation is rejection and immunosuppression. This is still a big concern. There are also contraindications for heart transplantation listed below.

- Contraindications

- Advanced irreversible renal failure with Cr>2 or creatinine clearance <30-50 mL/min

- Advanced irreversible liver disease

- Advanced irreversible pulmonary parenchymal disease or (FEV1 <1L/min)

- Advanced irreversible pulmonary artery HTN

- History of solid organ or hematologic malignancy within the last 5 years

Lifestyle Modification

- Smoking cessation

- Smokers vs. non-smokers that live with smokers

- Provide an environment that facilitates repeated interventions

- Willing to quit: quit plan and counseling

- Nicotine gum, inhaler, lozenge, nasal spray, patch Bupropion SR, Varenicline

- 5 A's: Ask about tobacco use, Advise to quit, Assess willingness to make a quit attempt, Assist in quit attempts, Arrange follow-up

- Behavior change strategies: physical and mental-cognitive strategies

- Address psychosocial issues: anxiety and depression, other mental health disorders, alcohol abuse, social support

- Identify relapse risk

- Provide national and local resources: 1-800-QUIT-NOW, Nicotine-Anonymous.org

- Self-help: BecomeAnex.org; SmokeFree.gov; Heart.org; Lung.org

- Alcohol Abstinence or restriction

- Restrict sodium intake to 3g/day (excessive >6g/day)

- Weight management

- Daily weight monitoring

Lifestyle modification is one of the recommendations by physicians for patients with heart failure. This includes smoking cessation, alcohol abstinence, sodium intake restriction, weight management, and daily weight monitoring.

OT Assessment

The Heart of the Matter

- Individuals experience both physical changes and emotional reactions coming from a cardiac event.

- How cardiac event affected the individual's

- Roles

- Work

- Confidence

- Relationships

- Middle-aged and older individuals with CAD have higher rates of self-reported decreased ability to perform ADLs compared to same-aged individuals without CAD (Ades, 2001)

When treating heart failure patients or even cardiac patients in general, we have to realize that a cardiac event affects individuals physically and emotionally. It impacts how one goes back to roles and work and their confidence in their ability to do activities. They are scared because they are short of breath or feel like they will die. Often, they limit themselves from doing the activities that they have done before.

ADLs/IADLs- Research

- Cardiac disease affects the individual's ability to engage in desired occupations, development of the activity limitations, and quality of life (Smith-Gabai & Holm, 2017; Stefanac, 2011)

- Patients with cardiac diseases have significant functional limitations (Duruturk, Tonga, Karatas, & Doganozu, 2015)

Some studies have tried to characterize how patients with cardiac diseases engage in their ADLs. In these, they have seen significant functional limitations, whether self-limited or because of the symptoms that they experience. They have also tried to look into how often their daily activities are affected because of symptoms of heart failure.

ADL Activities.

- Climbing stairs (45.9%)

- Walking (29%)

- Housekeeping (25.6%)

- Dressing (22.9%)

- Eating (17.1%)

- Transportation (15.5%)

- Bathing (15.2%)

- Taking medications (14.4%)

(Dunlay et al., 2015)

In this article, in particular, they gave each person a survey asking them, "What are the activities of daily living that are limited because of your heart failure symptoms?" Forty-five respondents, almost half of them, said that climbing stairs was an issue, and the next one would be walking. Others include housekeeping, dressing, toileting, and eating. It is also interesting to note that "taking medications," even though it is the last item, was problematic for 14.4% of the participants. So, we have to make sure that they understand and can take their medications, as it is one of the main things clinicians recommend to manage their heart failure effectively.

Predictors for ADL difficulties.

- older

- female

- diabetes

- CVD

- dementia

- anemia

- morbid obesity

- unmarried

Above are some other predictors of ADL difficulties.

OT Assessment- Vitals

- Blood pressure (BP)

- Heart Rate (HR)

- Rate of perceived exertion (RPE), BORG Dyspnea Scale

- Oxygen saturation (SPO2)

- Room air vs. supplemental 02

- Method of supplemental 02 delivery (nasal cannula, mask, etc.)

- Vital sign response to activity: pre/during/post (BP, HR, SP02). Orthostatic hypotension (OH)

- Recovery time if out of normal/expected range for activity

Typically, you need to assess their vitals, blood pressure, heart rate, rate of perceived exertion (RPE), oxygen saturation, and any vital response they have for activity, either pre, during, or post, or if they have orthostatic hypotension. You would want to desensitize them from feeling that whenever they try to do something hard or are having difficulty breathing, they are inflicting more damage to their heart. You would want to use this opportunity to provide them with feedback. "This is where we started. This is where we are right now." And also telling them, "Because of your heart failure, it is normal for you to experience shortness of breath. It will be normal for you to get tired and fatigued easily, which is why." You can talk about how physiologically that happens. I will now go over some parameters and terms you should know.

Norms

- Blood pressure (BP): Systolic <120mmHg and Diastolic <80mmHg

- Heart Rate (HR): 60-100 bpm

- Oxygen saturation (SPO2): >95%

- Respiratory Rate: 12-16 breaths per minute

- Temperature: 97.8-99.1 Fahrenheit (36.5-37.3 Celsius)

Blood Pressure

- Pressure of circulating blood on arterial walls

- Sphygmomanometer: blood pressure meter

- Systolic Pressure: First sound

- Diastolic Pressure: Last sound

- Electronic machine calculates mean arterial pressure (MAP)

- Ventricular assist device patients: use doppler to get the MAP

- What is orthostatic hypotension?

- How high is too high? How low is too low?

- What is the right way to take a person's blood pressure?

- Before pressure is taken

- 30 mins before no smoking, caffeine, or exercise

- 5 mins before: sit still – feet on the floor, back supported

- While pressure is being taken

- Cuff is the right size and placed correctly

- The arm should be at heart level, flat on a surface

- Position: seated upright, feet flat and uncrossed, back supported, no talking

- Check the pressure on both arms if able, take a reading of the higher pressure

- After pressure was taken

- 1 minute before retaking BP

- At least 2 readings - average

Orthostatic Hypotension (OH)

- Excessive drop in blood pressure of > 20 mm Hg systolic/ > 10 mm Hg diastolic, or both, when upright body position is assumed

- May be symptomatic (i.e., dizziness, lightheadedness, confusion, or blurred vision.

- Or may be asymptomatic (i.e., no symptoms experienced).

- OH is a manifestation of an abnormal BP response (due to a variety of possible factors)

- May occur at any age but is more prevalent in the elderly due to decreased baroreceptor responsiveness/reduced arterial compliance.

- Symptomatic treatment: supine with lower extremities above the level of the heart (i.e., reclined with legs elevated ideally).

Heart Rate (HR)

- Can use cardiac monitoring equipment or manual reading

- When should we use a manual reading?

- Normal heart rate response to exercise

- How high is too high? How low is too low?

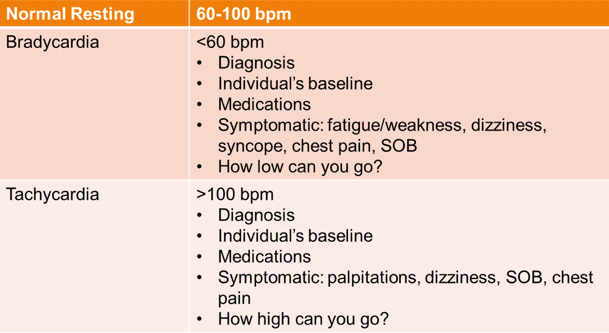

Figure 15. Heart rate readings.

Peripheral Oxygen Saturation (SpO2)

- A measure of how much oxygen blood is carrying as a percentage of the maximum it could carry

- Carried in the blood attached to hemoglobin molecules

- Referred to as SpO2

- >95% ideal

- >90% acceptable

- Challenges with assessing SpO2

- Poor signal

- Cold hands

- Weak pulse

- If not in room air, indicate oxygen system

Borg RPE Scale

- RPE: Rate of Perceived Exertion

- Another way to measure physical activity intensity level

- May provide a fairly good estimate of the actual heart rate during physical activity

OT Assessment- Other Components

- Upper extremity and upper extremity use

- Cognition, Perception, Sensation

- Vision, Hearing

- Trunk Mobility

- Balance

- Skin Integrity

Although they are cardiac patients and the bulk of your examination would be their vitals, you would also want to look at them as a whole person. You will need to look at their upper extremities, cognition, perception, and any sensation issues affecting their self-management. You also need to see if they have vision or hearing problems, trunk mobility, balance, and skin integrity. Are they prone to developing pressure ulcers, especially since their circulation is compromised?

ADLs/IADLs- Assessment

- Quality of ADLs before? Now?

- Barriers to independence

- Fatigue?

- Shortness of breath?

- Anxiety?

- Self-doubt?

- Health Management and Maintenance

- Perception and understanding of the problem

- Readiness to learn

- Willingness to change

- Literacy vs. Health literacy

You also want to ask them about their ADL quality before and how it is different now. Identify what their barriers are. Is it mostly fatigue or shortness of breath? Do they doubt themselves, and are they anxious? What is their perception and understanding of the problem for health management and maintenance? Are they ready to learn? Are they willing to change? What is their health literacy?

Occupational Profile

- Values and Interests

- Life experiences

- Performance patterns

- Supports and barriers to occupational engagement

- Environment: physical and social

- Context: personal, temporal, virtual

Then, you create an occupational profile about their lifestyle, what they value, and what their interests are.

ADLs and IADLs: Outcome Measures

- FIM

- AM-PAC: Daily Activity

- Performance Assessment of Self-Care Skills (PASS)

- Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM)

- Test of Grocery Shopping Skills (TOGSS)

- Executive Function Performance Test (EFPT)

- Kettle Test

- Weekly Calendar Planning Activity (WCPA)

Above are some of the outcome measures that we can use.

Evaluation of ADL Instruments

- Barthel Index

- Klein-Bell index

- The Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire, Green* (KCCQ)

- Performance Measure for Activity of Daily Living – 8

- Daily Activity Questionnaire in Heart Failure

- PULSES Profile

*Best suited for HF patients

(Fathipour-Azar, Z., Akbarfahimi, M., Vasaghi-Gharamaleki, B., & Naderi, N. (2017). Evaluation of Activities of Daily Living Instruments in Cardiac Patients: Narrative Review.)

In this article about ADL instruments, they attempted to compare the Barthel, the Klein-Bell, the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire, the more recent Performance Measure for ADL-8, Daily Activity Questionnaire in Heart Failure, and PULSES Profile. Although the KCCQ had an excellent internal consistency and is more sensitive to changes in clinical status in patients, especially with preserved heart failure, a lot of things still need to be done. Heart failure is very complex and heterogeneous in presentation. Not one of these instruments can capture everything. However, the KCCQ is the one with the best internal consistency.

Quality of Life Assessments

- Cardiac Health Profile congestive heart failure (CHPchf)

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/6158036_The_validation_of_a_new_quality_of_life_questionnaire_for_patients_with_congestive_heart_failure_-_An_extension_of_the_Cardiac_Health_Profile

- Left Ventricular Dysfunction Questionnaire (LVD 36)

- Minnesota Living with Heart Failure® questionnaire* (MLFQ)

- Specific Activity Questionnaire (SAQ)

- https://www.hellenicjcardiol.org/archive/full_text/2009/4/2009_4_269.pdf

*Best suited for HF patients

They also tried to assess the available quality of life assessments. I have put the websites where you can access these articles. In the second one, they tried to compare the Left Ventricular Dysfunction Questionnaire, Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire and the Specific Activity Questionnaire. They found that the MLFQ was the most responsive to improvements in the Six-Minute Walk Test. As it has been extensively studied, your patients will generally improve if modifications are made to the MLFQ. However, between KCCQ and the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire, the KCCQ is something that you can download and use for free, and the MLFQ has a cost.

Now, the bulk of our intervention will be with self-management and your patient's ability to care for themselves, so they do not progress further with their heart failure.

Self-Management Assessment

- Self-Care of Heart Failure Index (SCHFI) v.6

- Measures decision-making process in maintaining physiologic stability (maintenance) and response to symptoms (management)

There are two versions of the Self-Care of Heart Failure Index, SCHFI. There is version six, or 6.2, and there is another version, 7.2. They allow clinicians to download this for research purposes and also for use by patients. They also have different self-care questionnaires over there. This Self-Care Heart Failure Index asks four broad areas with different versions (English, Korean, Arabic, etc.). The first section asks about the patient's ability to help themselves by trying not to get sick, eating a low-salt diet, and using any system to help them remember their medications. The following section will ask about their ability to monitor their symptoms. The third part will ask them their responses if their symptoms indicate their condition is getting worse. Will they take medicine, call their doctor, or ask their family? And then the last section assesses their confidence in their ability to manage their condition. It is composed of 39 questions, and it is a self-report. This gives a glimpse into which areas to target regarding their self-management.

OT Interventions/Goal Setting

Goals

- Common patient goals

- Where do they want themselves to be

- "Get fitter"

- "No Pain"

- "Better Mindset"

- "Go back to work."

(Fernandez, Rajaratnam, Evans, & Speizer, 2012)

I also want to emphasize the importance of goal setting. Usually, when we ask them, "What do you want to do in occupational therapy?" Common goals are along the lines of where they want themselves to be. However, they may not be as realistic as we want them to be. Examples are "Get fitter," "No pain," "Better mindset," or "Go back to work." The following are behavioral risk factors for cardiac disease vs. actual goals.

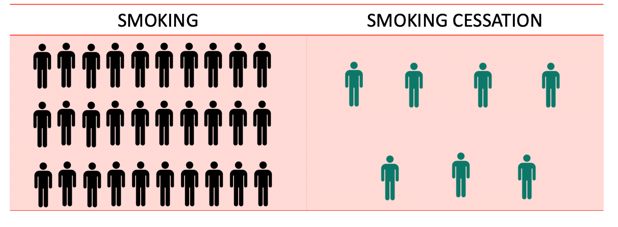

Smoking vs. smoking cessation. In the above study, 30 patients identified themselves as smokers. Still, only seven of these 30 patients indicated smoking cessation as either their short-term girl, girl, short-term, or long-term goal.

Figure 16. Smoking vs. smoking cessation.

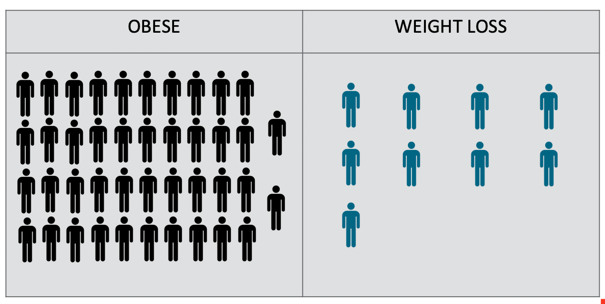

Obesity vs. weight loss. Forty-two patients met the criteria for obesity, and only nine indicated weight loss as a goal.

Figure 17. Obesity vs. weight loss.

Stress vs. stress reduction. Also, for stress, 44 participants identified stress as part of their cardiac risk factors, and only one identified stress reduction as their goal.

Figure 18. Stress vs. stress reduction.

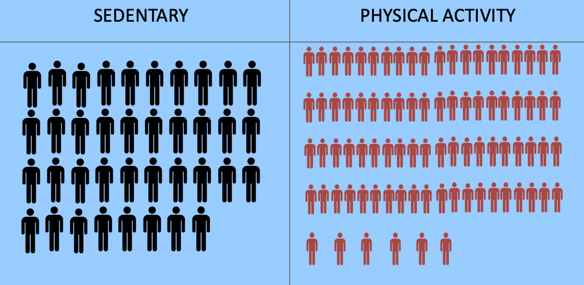

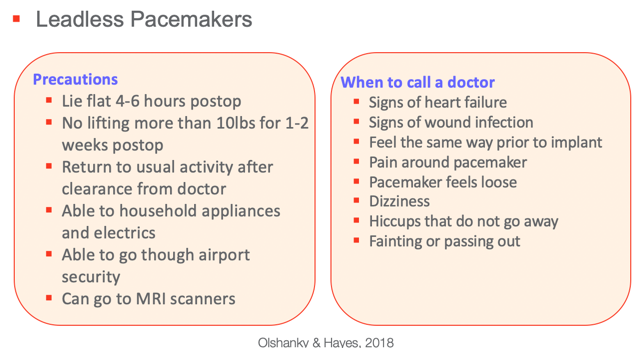

Sedentary vs. physical activity. But, at least most people know they should be physically active after a cardiac disease. Thirty-eight participants indicated they were physically inactive, and 86 patients indicated increasing physical activity as a goal.

Figure 19. Sedentary vs. physical activity.

Also, in this study, 62% of patients have high cholesterol. 60% had high blood pressure, and 37% of the participants had diabetes. However, none of these patients identified lowering their cholesterol or blood pressure or managing their diabetes better as part of their goals. We need to know the risk factors and some of the lifestyle modifications they are recommending to guide them in goal setting. They should not just focus on physical activity and exercise. They must also focus on lifestyle modification and sustain these changes to help them over time.

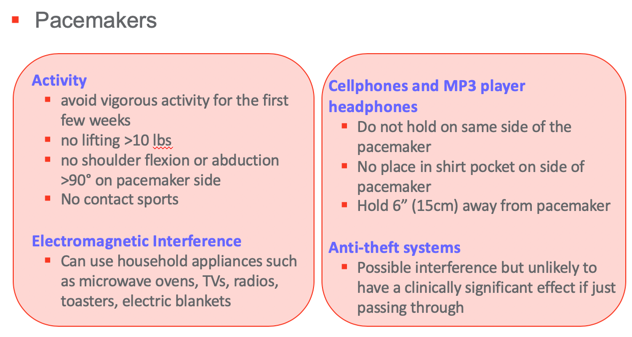

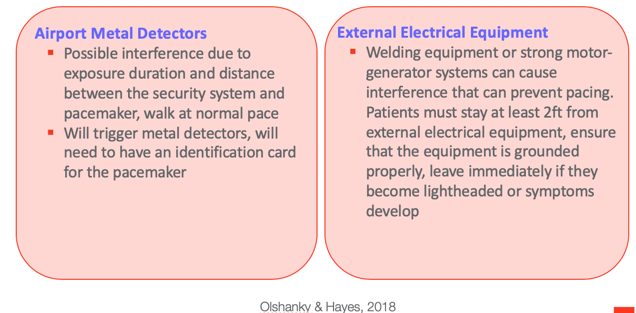

Minimally Invasive Devices

I have also compiled some recommendations for self-management with minimally invasive devices such as pacemakers, leadless pacemakers, and AICDs.

Figure 20. Overview of the pacemakers.

Figure 21. Overview of leadless pacemakers.

Mechanical Circulatory Support

- Short term

- Hemodynamic support by performing the work of a failing left ventricle, right ventricle, or both

- Intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP)

- Non-IABP percutaneous mechanical circulatory assist devices

- Extracorporeal membrane oxygenator pumps

- Non-percutaneous centrifugal pumps (used during CABG

(Jeevanandam, Eisen, & Pinto, 2019)

- Intermediate and long-term use

- Assist and support circulation

- Patients with decompensating advanced HF who do not improve or stabilize with optimal medical therapy

- Use

- Bridge to transplant

- Bridge to recovery

- Destination therapy (Birks, 2019)

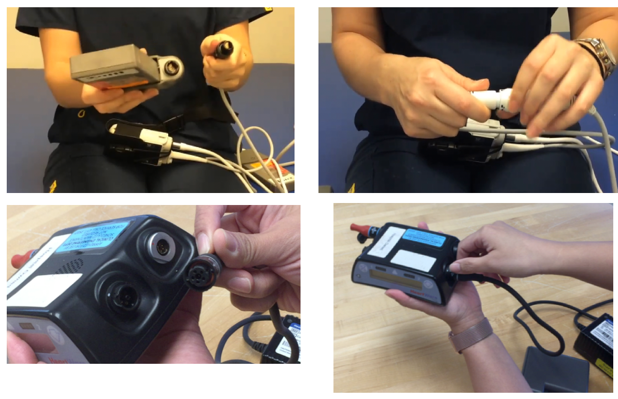

There are short-term and long-term ones. Here are pictures of the two devices in Figure 22.

Figure 22. Heartmate II and Heartware.

The top one is the HeartMate, while the bottom one is the HeartWare. I wanted to show you how attaching the computer's cords to the batteries might be difficult for our older patients if their vision and dexterity are affected.

Ventricular Assist Device

Home Care.

- Incisional care

- Dressing changes

- Showering and bathing

- Protect chest from pressure or trauma, may need to accommodate for seatbelt

- Discuss return to work, sexuality, and intimacy

- Will need a medical ID

- Notify EMS, electric company, fire department, physician, police department, TSA

HeartMate II Patient and Caregiver Training.

- Device and parts (battery, alarm reset, display buttons)

- Switching to and from battery to power module

- Power module function and connections

- System controller change

- Exit site care

- Warnings and precautions

- Action plan during an emergency

- Identifies devices to bring when going outside the house

- Operation of universal battery charger

- Controller alarms and alerts

- Red heart alarm

- Red battery alarm

- Yellow diamond alarm

- Power cable disconnect alarm

- System controller fault alarm

- Low-speed operation

- Driveline fault

- System controller backup battery not installed

- Warnings and precautions:

- Do not play contact sports or jumping activities

- Do not swim or take a bath

- Do not try to repair any of the equipment by yourself

- Do not touch television, computer screen, vacuum

- Do not have MRI

- Sleep only when connected to the power module

- Inspect all connections prior to sleeping

- Power module should be plugged into 100v 3-pronged grounded outlet with no adapters or extension cords

- Wear anchor all the time, change anchor weekly or when soiled

- Things to bring outside:

- Extra controller and controller battery

- 2 sets of extra batteries

- 2 extra battery clips

- Rain poncho

- Emergency phone number/ alarm guides

- Cellphone

- Discharge binder with a medication list

HeartWare Patient and Caregiver Training.

- Device and parts (controller)

- Define pump speed, power, and flow

- Switching to and from power sources

- Function and connections to AC power

- Function and connections to battery power

- Controller alarms and alerts

- Controller change

- Driveline exit site care

- Warnings and precautions

- Action plan for emergencies

- Identifies devices to bring when going outside the house

- Operation of battery charger

- Controller alarms and alerts

- High-critical priority: VAD stopped, critical battery, controller failed

- Medium priority: controller fault, high watts, electrical fault, low flow, suction

- Low-priority alarms: low battery, power disconnect

- More than 1 alarm: most severe alarm displayed first

- Warnings and precautions:

- Do not play contact sports or jumping activities

- Do not swim or take a bath

- Do not try to repair any of the equipment by yourself

- Do not touch television, computer screen, vacuum

- Do not have MRI

- Sleep only when connected to the power module

- Inspect all connections prior to sleeping

- Things to bring outside:

- Extra controller

- 2 sets of extra batteries

- Rain poncho

- Emergency phone number/alarm guides

- Cellphone

- Discharge binder with a medication list

- Cellphone 20 inches away from the controller

- Keep magnetic closures away from the defibrillator

I have also put in some tips for performing home care with patients with a ventricular assist device and recommended training for the patient and the caregiver. It can be cognitively demanding and challenging for VAD patients because they must remember the alarms. This is something that they have to do every day. As a clinician, I do not remember what all the yellow diamond alarm indicates. I would have to have a cheat sheet with me. There are also warnings and precautions they would have to remember and things to remember to bring outside to prepare for an emergency. This is why it is always essential for them to have a co-learner for this one. I have provided this information for both HeartWare and HeartMate.

Considerations for rehabilitation for VADs.

- Hemodynamic monitoring: MAP, RPE, subjective report/symptoms

- Safety with driveline: awareness, memory, spatial neglect, wound care if hemiplegic, care when with poor dexterity, amputee

- VAD equipment: Can patients manipulate equipment? Can they see the equipment? Can they remember the steps to change to and from the main power source to batteries?

- Use interval exercise training at the onset of the program

- Daily chlorhexidine (CHG) bath; NO showers initially.

When working with patients with VADs, MAP (Maximal Aerobic Power), and RPE (Rating of Perceived Exertion), it is necessary to get subjective reports and symptoms. You would want to match their MAPs to what they feel so they can self-monitor. It would help if you also educated them about safety with their drivelines, equipment, and the CHG baths (Chlorhexidine gluconate- a cleaning agent used to prevent central line infections). In our institution, we do not shower them initially. However, some institutions do allow VAD patients to shower right away.

Self-Management

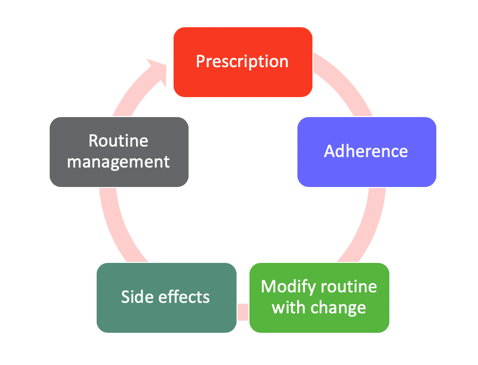

Self-management is the client's ability to apply all these recommendations and lifestyle changes for themselves. It is divided into three broad categories.

Self-Care Maintenance

- Medications

- Diet/Fluids

- Physical Activity

The first one would be self-care maintenance. These activities help them maintain their health and prevent their heart failure from worsening, including diet, fluid intake, and the amount of physical activity.

Medication Management.

- Ability to read and understand medication labels

- Vision, dexterity

- Expiration date

- Adaptations?

Figure 23. Visual on medication management.

Medication management is more than just taking a pill. It also involves getting prescriptions, adhering to their medication regimen, modifying their routine if there are some changes, being aware of side effects, and communicating the side effects to their physicians, as well as routine management. For example, if they are going on a trip, what are they supposed to do so that they still adhere to their medication routine? Of course, you would want them to be able to read and understand medication labels. And if they can do that, training them or finding applicable technology to help them adhere to their medication regimen is also essential. Are they aware of their medication's expiration date and any adaptations they need to incorporate into their medication management routine?

Diet and fluid intake.

- Ability to understand the relationship between excess dietary sodium, increased edema, and impact on cardiac function

- Ability to read nutrition labels on foods

- Know the amount of sodium and fluid recommended per day and how to calculate

- Identification of sodium sources in a typical diet and how to reduce

- Low sodium: 140 milligrams or less

They need to understand the relationship between excess dietary sodium and their edema. Sometimes, they do not put those two together, so if they eat food with high sodium, they may see an increased swelling in their ankles. They also need to know how this relates to more impaired cardiac function over time. Can they read the nutrition labels found in foods? Do they know how to locate information? And if they know how to locate information, can they put that together with their recommendation? What does low sodium mean? Education also includes identifying sodium sources in a typical diet and how to reduce them.

Physical activity.

- Knowledge of physical activity prescription

- Intensity

- Duration

- Frequency

- Location: Home vs. facility-based

- Type of activity

- Method of monitoring exertion level

(American Heart Association recommends 150 minutes of moderate aerobic activity or 70 minutes of vigorous aerobic activity.)

It is not enough that they know about their physical activity prescription in terms of exercise intensity, duration, and frequency, although it is crucial. Many of our patients think physical activity refers to exercise, and they only exercise for a short period and then stay sedentary for the rest of the day. We also have to tell them to remain active in day-to-day tasks.

- Increasing confidence in their ability to participate in tasks

- Biofeedback: show vitals, use Borg RPE or dyspnea scale if appropriate

- Keep a log of activities to show improvement

- Balance activities patient is confident doing and activities that they are not so sure they can do

We should also help them to increase their confidence in their ability to participate in their daily tasks. What were the activities you did before that are difficult to do now? Explore why something is difficult, and determine if they are avoiding the activity versus they are unable to do it. Show them biofeedback and their vitals. Have them practice using the RPE or dyspnea scales in their daily activities. With these, they will be able also to assess if they are having more difficulty completing their daily tasks, which triggers a response of either calling their doctors or going to the doctor's office. It would help if you also taught them to keep a log of activities to show improvement and to give them the necessary motivation to keep going. The more they do and the more physically active they are, the better they can do these activities.

- Balance Rest and Activity

- Emphasize that both are needed for optimal performance

- Energy Conservation Techniques: 4Ps

- Planning and organizing daily routine and tasks

- Keep items within reach, and in the area you need them

- Gather all items before starting a task

- Do you need adaptive equipment or DME to perform the task?

- Divide and conquer

- Plan ahead

- Alternate heavy and light tasks

- Planning and organizing daily routine and tasks

It would be best if you also stressed that it is essential to balance rest and work. Energy conservation techniques become important when you are working with heart failure patients.

- Energy Conservation Techniques: 4Ps

- Prioritizing

- Prioritize activities that are important for you

- Simplify tasks

- Positioning

- Sit if possible

- Minimize unnecessary movements: arm elevation, chicken wings (keep elbows close to the body), support elbows on a surface

- Minimize the need to bend, reach, twist

- Push vs. pull

- Carry items close to the body

- Pacing

- Don't schedule too many things in one day

- Allow enough time for each task

- Rest 20 to 30 minutes after each meal

- Rest before being tired

- Get a good night's sleep

- Do an energy conservation lecture with a Planned activity

- If cooking is the planned activity:

- Ask the patient how they plan to complete the activity

- Ask if doing all the steps would make them tired, and if yes, which steps should they prioritize doing for this session?

- What positions should they use during the task? Equipment?

- Observe how they pace themselves and give feedback

- Prioritizing

There are four Ps of planning, prioritizing, positioning, and pacing. Doing your energy conservation technique lecture with a planned activity is best. If you plan a cooking activity, you will prompt the patient to schedule the task. What are you going to prepare for this activity? Are you able to complete this activity? And if not, what steps would you prioritize today so that tomorrow we can achieve this cooking task?

Self Care Monitoring

- Daily Weights: easy to read numbers, big, same time, logbook, greater than 2-3 pounds weight gain needs immediate action.

- LE Edema Checks: daily checks, how far is the edema, how much

- Symptom Recognition

- Activity tolerance

- Breathing ability (ability to lie flat without pillows)

- Lightheadedness/Dizziness

Ask them to think about the positions they should use during the task and if they need to use any equipment to make it easier. Observe how they pace themselves and give them feedback. Daily weights, lower edema checks, and symptom recognition are part of self-care monitoring. You want to ensure that they know the importance of doing these three things and what the numbers mean. For example, emphasize that a two- to three-pound weight gain needs immediate action. They should do this at the same time every day, ideally in the morning, and then have a logbook to monitor their trends. Lower extremity edema checks also need to be done daily. And then documenting how much edema they have. Lastly, symptom recognition involves monitoring their activity tolerance. Is it getting better or worse? Is their breathing getting better or worse? Or is their lightheadedness or dizziness getting worse? Of course, if any of these are getting worse, they want them to reach out to their doctors immediately.

Barriers to Timely Care.

- Unsure which doctor to contact (individuals often see several)

- May have few options besides ED (rural areas)

- May wait weeks to get appointment with doctor

- May be physically unable to get to doctor's office

- May be concerned about cost

- Performed infrequently and inadequately performed by individuals with heart failure

- Fewer than 50% report weighing themselves daily.

- Of those who do weigh themselves, few consider fluid weight gain to be a significant/ relevant problem.

There are different barriers to timely care. Sometimes, they may be unsure about which doctor to contact as they may have multiple healthcare practitioners. You can help them problem-solve and identify who they should contact. If they live in rural areas, they may have few options besides the emergency department. They may also need to wait weeks before getting an appointment with their doctors, or they may not get to their doctor's office physically. Some of them will be concerned about the cost. It is not enough that we discuss how they should manage or respond to symptoms worsening but we also explore their hesitations for timely care. Sometimes, these routine checks are performed infrequently and inadequately. Like energy conservation techniques, we should see how they accomplish this daily self-care. Ask them to go on a scale. Ask them to measure their edema. Ask them to rate their activity and tolerance. Fewer than 50% of patients with HF report weighing themselves daily. And of those who weigh themselves, few of them consider fluid weight gain to be significant or a relevant problem. So, it is putting those things together.

Reasons Symptoms are Not Recognized.

- Lack or inconsistent symptom monitoring

- Lack of ability to interpret the significance of symptoms

- The belief that symptoms are not severe

- The belief that symptoms are caused by medication side effects or another condition

Sometimes symptoms are not recognized, or the clients have inconsistent symptom monitoring. Thus, they do not have a gauge of what their usual status is like. Some of them cannot interpret the significance of symptoms. Again, this is not only teaching them what to do but helping them problem-solve. Some of them believe that the symptoms are not that severe or are caused by their medications as side effects. Hence, we should also discuss their medications and potential side effects.

Self-Care Management

- Respond to Symptoms

- Seek Needed Treatment

The last part is management itself. This is where they need to respond to the symptoms and seek treatment if necessary.

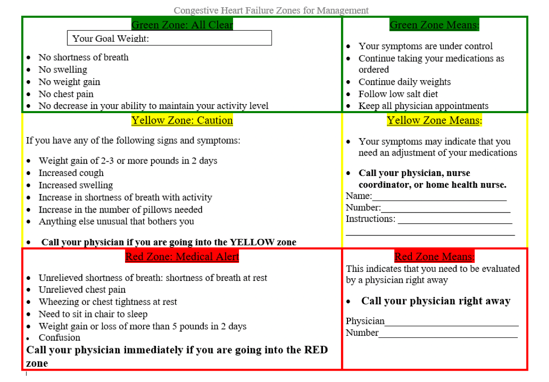

Action plan.

Figure 24. Action plan.

Here we have an action plan. This action plan is from a government website. The website heart.org has also created its action plan. You can print this off, but remember to print them off with colors because it is based on a traffic light system. The green zone is clear where the client is good to go, and they need to manage their heart failure as usual. The yellow zone is the caution zone and indicates the client needs to pause. What is happening? This could be weight gain, a cough, swelling, shortness of breath, an increased number of required pillows, or anything unusual bothering them. You would want them to fill this out with their healthcare physician as they may instruct them to either take a specific medication or what they can do before getting an appointment to check it out. The red zone is where they need to seek medical attention right away. Symptoms include unrelieved chest pain, wheezing, not tolerating sleeping, or if they or their family members have noticed confusion. They want to go to see their physician right away. If they cannot, then they go to the hospital and the emergency department.

Self-care management barriers.

- Inadequate patient education and skill development

- Low health literacy

- Healthcare workers may underestimate/ not recognize

- 5th-grade reading level

- Inability to follow through with a complex regimen for a chronic condition (cognition, depression, coping, caregiver support)

- Overwhelmed with information from multiple providers

- Medication cost

- Medication side effects

- Multiple chronic comorbidities with complex regimens: e.g., renal, diabetes

Self-care management behaviors seem easy to do; however, inadequate patient education and skill development are barriers to effective self-care management. Low health literacy is also one of the most significant barriers. We need to have clients perform all these self-management skills in front of us to assess any barriers that they may have. They may also be unable to follow through with a complex regimen and be overwhelmed with information from multiple providers. They may also not take their medications because of perceived side effects and costs. For example, numerous chronic comorbidities such as diabetes may limit them from performing effective self-management.

Ability to perform self-management.

- Understand the patient's abilities

- Assessment and collaboration by all members of the healthcare team

- Cognition

- Health Literacy

- Vision/Perception

- Mobility

- Behavior and readiness to change

- Psychological status and coping

- Caregiver support

Barriers for healthcare professionals.

- Lack of knowledge and preparation to recognize patients' individual needs

- Difficulty providing appropriate education

- Over-estimation of patient ability. Under-estimation of the complexity of the regimen on a daily basis for patients

- Lack of reimbursement from third-party payers for education/counseling services

- Need for coordination/communication with other multiple providers

Healthcare providers may lack the knowledge and preparation to recognize the patient's needs and have difficulty providing appropriate education. And not all of the patients will be accepting of what we tell them. Many of our patients will even overestimate their ability or underestimate the complexity of the regimen they will need. There is also a lack of reimbursement from third-party payers. Finally, there is a need for coordination/communication with multiple other providers.

Patient Education

Patient education: Heart Failure Society of America guidelines.

- Heart failure education should occur at all points along the healthcare continuum in Acute Care to Outpatient settings.

- Education should be specific to an individual's literacy level/abilities and encompass post-teaching assessment to ascertain patient understanding.

The Heart Failure Society of America provided the following guidelines for patient education. It should occur at all points and be specific to an individual's literacy level and abilities.

Patient education for effective self-care skills.

- Knowledge Base:

- "Teach Back"

- Specific questions about the material

- Limit teaching points to 3-4 per session

- Repeat, repeat, repeat! At all visits

- Skills:

- Experiential learning: Self-medication program while in hospital

- Roleplay: Have patient problem-solve what to do in a situation

- Use groups to facilitate learning

For our education to be effective, we must use a teach-back method. We have to ask them specific questions about the material. We should limit teaching points to three to four per session and make them more concrete. Like my example earlier, use teaching points in the context of an activity so that they will see immediately how they can apply the information that you have provided them. Experiential learning, roleplaying, and group learning can also facilitate learning.

Case Study

- Mrs. KJ is a 73-year-old female with pAfib on Eliquis, hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy, DMII, CAD with 70% calcified LAD, and EF of 25%.

- MD orders: heart-healthy diet

Nursing education: smaller portion size, eat more vegetables, limit unhealthy fats, low sodium diet.

This client has heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. The MD told her to "just stay healthy" and use a heart-healthy diet. Nursing educated her on eating smaller portions, eating more vegetables, limiting unhealthy fats, and staying on a low-sodium diet. As OTs, how can we help? Can we support them by subscribing to the recommendations of both the doctor and the nurses? For a low-sodium diet, you would want to define, first, what low sodium means. This includes food with 140 milligrams or less. When reading food labels, they do not look at the serving size of each can. A can of soup has four serving sizes, and the sodium says 120 mg. If they eat the whole can, they have to multiply 120 by four. You want to see if the client can interpret the food labels, emphasizing what food contains sodium and other problematic ingredients like MSG, baking soda, and baking powder. We can also help them to find alternative ways to flavor food. This is a huge part. Often, they will say, "Well, I have to limit my salt, but my food doesn't taste like anything." Performing a food preparation activity with different herbs and spices will help you assess how they can perform their cooking activity and give them positive feedback that their food can taste as good as before. For fluid restriction, they often limit that to a liter of fluids. Our clients may not know if they have consumed one liter of fluids. We can help them to set up a tracking system. For example, we can give them four smaller bottles and say, "If you drink all these four bottles, this is equal to one liter." You are helping them make sense of their diet and making it more concrete.

Summary

At the end of my handout, I have included information about cardiac rehab. You can also email me; I have included that in the handout.

Questions and Answers

Could you explain a little about too high or too low heart rate?

With heart rate, 60 to 100 beats per minute is our average heart rate. When treating a client, you want to know their baseline heart rate. Some doctors want their patients to have a lower heart rate to reduce the stress on their hearts. They may give them beta-blockers to keep them on the lower side of the 60, maybe the 55 to 60 range. And, when they are on beta-blockers, it may take them a long time to ramp up in terms of heart rate to adapt to any physical activity that they do. Thus, you would want to know their average heart rate response to any activity. You would wish for their heart rate to increase with a physically demanding activity and then, after some time, be able to return to their normal range. For example, if they started at 70 bpm, you would want them to increase by a maximum of 40 beats per minute. Anything more, you would be concerned. Also, the heart rate increase should match the intensity of the activity. Let's say they started with 60 bpm, and then you did a grooming activity while sitting down with their arms supported, but then suddenly their heart rate goes to 120. This activity does not match their heart rate response. This is something that you would want to let the doctors know. Conversely, if you did an activity, and instead of the heart pumping harder, the heart rate decreased, you would want to reach out to the physician to let them know.

What are the guidelines for blood pressure and heart rate of when to hold therapy services?

You always want to ask the physicians what they are comfortable with, especially with heart failure patients. Are they giving them medications to decrease their blood pressure by reducing their heart rate? Or are they comfortable keeping this patient with higher blood pressure because they are concerned about blood circulation? You must get parameters before seeing a client with heart failure or other cardiac issues. What are the blood pressure parameters with which you are comfortable? What are the blood pressure parameters that deem a call to you? I provided the norms for blood pressure earlier. For systolic, anything from 90 to probably around 140 would be comfortable. And, for anything below 90, I would be concerned and will ask their physicians. You are concerned about the ability of the body to support circulation when you are doing an activity. With the diastolic reading, you would also want to stay in a range close to the norm. With activity, you should expect their blood pressure to bump up during intense activity slightly. And during rest, you would expect them to go down in terms of blood pressure and be as close to their baseline as possible. If they have difficulty doing that, I would call the physician and say, "I've started this activity. They've reached 170, and they're still at 170 systolic, even after I've provided them with five minutes rest."

How do you manage orthostatic hypotension affecting patients performing daily self-care tasks?

First, we have to define if it is orthostatic hypotension. Have them stand up for at least three minutes before you retake their blood pressure. What is the reason why they have orthostatic hypotension? Is it because they are just not drinking enough fluids? Or is it because of their poor hemodynamic response to being upright? We can also explore different options. Is using a binder okay? Will medications such as midodrine help? And if these do not help, can we teach clients to do things in an alternative way? For example, sitting down and progressively increasing their body's ability to be upright.

References

Available in the handout.

Citation

Tovera-Magsombol, C. (2019). Living with heart failure: The OT role. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 4988. Retrieved from https://OccupationalTherapy.com