Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Navigating Assessment In Pediatric Acute Care, Infants Through Adolescence, presented by Anjelica Malvasi, PP-OTD, OTR/L.

*Please also use the handout with this text course to supplement the material.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to identify strategies for preparing for the assessment of a pediatric client in the acute care setting.

- After this course, participants will be able to recognize assessment tools that can be utilized in pediatric acute care.

- After this course, participants will be able to identify areas of concern that are critical for thoroughly assessing pediatric patients of different ages (e.g., infants, toddlers, school-aged children, and adolescents).

Introduction

I'm excited to be here with everybody to share my knowledge about pediatric acute care. Before I start, I want to share a couple of photos—one of myself and one that gives you a little glimpse of what life is like in the pediatric acute care world (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Images from the author.

My hope for today's presentation is that you walk away feeling more inspired, confident, and prepared to assess a pediatric patient in the hospital setting. I also want to preface that I’m an OT. This course focuses on occupational therapy, but much of what I will discuss can apply to other therapy services, including speech and physical therapy. So feel free to share some of the information that you learn.

Hospital Service Areas

Most of you are likely familiar with acute care, but I want to start with a little refresher. Acute care is an area of medical care that serves individuals who might be suffering from an acute illness or injury. This area of care is one of the many that might fall under the umbrella of services a hospital can provide. Acute care admissions are typically short-term, but that isn’t always the case, especially in pediatrics. From personal experience, I’ve had patients who were admitted for just one or two days, and others who stayed for years. It’s also common for some patients I see to be frequently readmitted, so I get to work with them more than once.

Each hospital system might structure its pediatric acute care services differently, but I will focus on specific areas for today's presentation. These include the neonatal intensive care unit, which provides intensive care to medically fragile or premature infants typically under the age of one; pediatric intensive care, which serves children of a variety of ages needing intensive medical attention; specialty units that focus on specific populations, like those with burns, cancer, heart conditions, or neurological issues; and general acute care, where patients may not require as much medical intervention as those in the ICU but still aren’t medically ready to go home.

Working in the Acute Care Setting

What’s it like working in pediatric acute care? Maybe you’re just starting a new job in this setting or are interested in transitioning to acute care. Either way, I want to share some of the things I love about this setting and some aspects that I find challenging. It’s a very fast-paced environment, especially in the intensive care units. Acute care tends to be more medically focused and leans heavily into the medical model.

For those interested in learning about different diagnoses and medical procedures, this setting is a great fit—and it’s what drew me to this area in the first place. There are lots of opportunities to pursue advanced practice areas. If you’re interested in working with burn patients or in the NICU, for instance, there are certifications you can earn to become more specialized in those fields. And there’s always variety. Depending on where you work, you might see infants, toddlers, school-age children, adolescents, and patients with mild to severe illnesses across various medical diagnoses, which I’ll discuss later.

One of the fascinating things about this setting is that there's always something new to learn, but it can also be challenging at times. One of my favorite parts of this work is the collaboration. You get to work with so many different people. I’ve learned much from other healthcare professionals and had opportunities to share my expertise with them.

Common Diagnoses

- Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

- Non-accidental Trauma (NAT)

- Orthopedic Injuries

- Spinal Cord Injury (SCI)

- Congenital Heart Defects (CHD)

- Pediatric Cancer (i.e., Leukemia, brain tumors)

- Burns

- Seizure Disorders

- Muscular Dystrophy

- Strokes

- Failure to Thrive (FTT)

- Trauma (i.e., gunshot wounds, car accident, dog bites)

- Respiratory Illness (Examples: COVID, flu)

You'll run across many different medical diagnoses in pediatric acute care. When I first started at the hospital, I remember keeping a little notebook where I’d jot down different diagnoses I encountered. If I had never heard of something before, I’d take the time to look it up and better understand it, because nine times out of ten, I would end up running across it again. These are just some of the diagnoses you might see in acute care, and the list continues to grow the longer you're in this setting.

Interprofessional Team

- Nurses

- Speech Language Pathologists (SLP)

- Physical Therapists (PT)

- Respiratory Therapists (RT)

- Certified Child Life Specialists (CCLS)

- Music Therapists (MT)

- Social Workers

- Psychiatrist/Psychologist

- Chaplains

- Care Coordinators

- Pharmacists

- Nurse Practitioners (NP)

- Physician Assistants (PA)

- Medical Residents

- Attending Physicians

Collaboration in this setting is essential to support the continuity of care. There are so many opportunities to work with other healthcare professionals. Some of the team members I regularly collaborate with include nurses, speech-language pathologists, physical therapists, respiratory therapists, certified child life specialists, music therapists, social workers, psychiatrists, psychologists, chaplain care coordinators, pharmacists, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and both medical residents and attending physicians.

If pediatric acute care is new to you, I want to highlight two roles: certified child life specialists and music therapists. I love everyone on the therapy team, but these two are the ones I find myself working closely with quite often. They’re great for co-treating. Typically, they’re non-billable services, so we don’t have to worry about who gets credit for the session, and they complement what OT is all about. If you have these professionals in your setting, I highly encourage you to get to know them and take advantage of the unique collaboration they offer.

Preparation: Chart Review

First, we will discuss what you must do to prepare for your assessment. In my opinion, one of the most critical parts of the assessment is what you do beforehand. You can gather so much information beforehand to help guide you during and after you meet with your patient and their family. A great place to start is by looking through their medical chart.

You’ll want to begin with the occupational therapy order. One of the care providers—like a physician, nurse practitioner, or PA—typically puts in this and gives you insight into what the team might be looking for from you. It’s not always detailed, and often you’ll still have to ask more questions, but it might say something like “feeding assessment” or “splinting assessment,” which helps shape your focus. Then you’ll want to look at the primary diagnoses, any other medical issues, what lines and tubes the patient has, the medications they’re receiving, their weight-bearing status, any special precautions, and whether there are any social concerns.

I added social concerns to that list because I think it’s crucial to know them beforehand. In pediatrics, there are cases where child protective services might be involved, and having that context before you go in to speak with the patient and their caregivers can be helpful.

Preparation: Medical Team Check-In

In acute care, things change very, very quickly. If you work in that setting, you already know this, but you may not get all the information you need just from reading the chart. So it can be beneficial to find other ways to gather that information—if you can, if you have the time, and if it’s something your department supports.

For example, most hospitals have bedside rounds, usually daily and typically occur in the morning or early afternoon, though sometimes they happen overnight. During these rounds, the medical team discusses the patient’s status, any necessary medication changes, and the plan for the day. There are also interdisciplinary rounds, where the entire team comes together on the unit—maybe once or twice a week, or even daily—to go over every patient. These discussions usually include medical status, discharge planning, and social concerns.

It’s also beneficial to check in with other team members, like physical therapists, child life specialists, music therapists, speech-language pathologists, and other therapy colleagues. They may have already worked with the patient and can offer valuable insights from their perspective. That kind of collaboration can give you a clearer picture of what your patient might need before you begin your assessment.

Preparation: Before You Start

It’s also imperative to talk to the bedside nurse, and I want to take a moment to highlight that here. As I mentioned, things can quickly change in acute care, and the bedside nurse is often the most in the loop. They’re working closely with the patient and are usually the first to know if the patient is experiencing significant pain, if there’s been a change in medication, if the patient is having a particularly rough day, or if something new has happened that hasn’t been documented yet. Checking in with them before entering the room is always helpful. Even a quick, “Hey, I’m going to see this patient—anything I should know?” can go a long way. It doesn’t have to be an extensive conversation. My hospital even has a system that allows us to text the nurses, which I find helpful.

I also try to do a few other things before getting started. One is simply knocking on the door out of respect for the patient and their family. You’d think it would be common sense, but when we’re caught up in the fast pace of the hospital, sometimes people forget. Taking that moment to knock is a small but meaningful gesture. It’s also critical to follow your institution’s hand-washing protocols. If the patient is on any isolation precaution, like for C. diff, it’s essential to follow those guidelines carefully.

One thing I find especially important is reading the room. Let’s say you knock and walk in, and immediately notice the patient and their family crying or are in a meaningful conversation with a medical team member. That might be a good time to say, “I’m sorry for interrupting. Is there a better time for me to come back?” If you can return later, even if that’s challenging in a busy acute care setting, it shows respect and can strengthen your therapeutic relationship.

Always introduce yourself and explain your role. I like to give my little OT elevator speech here because many families aren’t entirely familiar with what an occupational therapy practitioner does for children in the hospital. This is often a time when families meet many different people, which can be overwhelming. So, taking a moment to clarify who I am and how I can help sets a good first impression and gets that therapeutic relationship off to a strong start.

Finally, take note of what’s happening in the room. Pay attention to the time you enter—it’s helpful for your documentation. Notice who’s present, check the patient’s vitals, and assess the lines and tubes around the patient. The moment you walk in, your mind should start scanning the environment. You’ll want to begin thinking about any safety precautions you might need to take, what needs to be moved if you’re going to reposition the patient, and anything else that will impact how you approach the session.

Preparation: Considerations

Before getting started, a few things to consider are the timing and setup of your assessment. Productivity in acute care can be challenging because you don’t have scheduled appointments with your patients. You’re typically in control of when you see them, so it’s up to you to determine the best time to visit your patients throughout the day.

You’ll want to think carefully about when that best time is. Pain management is one factor that can either be a barrier or an opportunity. If your patient is on scheduled pain medication, checking in with the bedside nurse might be helpful to find out when it’s administered. Depending on the situation, you might want to assess the patient just before the medication is given or wait until after it starts working—whatever seems most appropriate based on input from the nurse or the family.

You might also notice in the chart that the patient is scheduled for an MRI on the same day you must complete your assessment. In that case, you could reach out to the bedside nurse or the medical team to find out when the MRI is scheduled, so you don’t waste time trying to see them when they’re unavailable. Personally, I know I sometimes walk 12,000 steps a day just trying to get where I need to go, so anything that helps streamline my schedule is a huge help.

Another consideration is the location of your assessment. Are you planning to conduct it in the patient’s room, or do you have access to a designated therapy space? What kind of equipment are you going to need? Will you need to bring toys, ADL items, or printed educational materials? If I know that I’ll need to provide something like developmental or orthopedic education, I’ll print it out in advance and bring it with me to save time.

We’re going to move on to the components of the pediatric assessment. Still, before we do that, I want to quickly talk about three significant topics that will impact your assessment and future treatment.

Mental Health/Trauma

The first thing I want to talk about is mental health and trauma. In pediatrics, you're often working with young children or adolescents who have complicated medical diagnoses and have been hospitalized multiple times. This isn't new for them—it’s something they’ve been going through for a while. Medical trauma is prevalent in this setting. These patients may have undergone repeated painful, invasive, or frightening procedures that have left them feeling fearful about being in the hospital or interacting with hospital staff. With all of us wearing masks, especially during certain times, we can start to look the same to these younger patients, which can feel intimidating and scary for them.

All of this often leads to a significant loss of control. Many kids in the hospital don’t get a say in what’s happening to them because their care is medically necessary. As a result, they sometimes seek control in other ways. For pediatric patients who have experienced trauma, incorporating play or positive sensory experiences can be helpful, especially for younger children. If I know from talking to the staff that a particular patient is having a tough time, I always bring toys. I usually do this anyway, but it becomes vital in those cases. We have toys like a piggy bank and squigs—fun, familiar items I can carry. That way, when I walk into the room, the child sees me and starts associating me with something that’s not painful. It’s a simple way to start our relationship on the right foot.

I also contact the child life specialist, an expert in supporting children and families through the challenges of hospitalization. If I’m concerned, I might talk to them before the assessment or ask them to join me, especially if their presence will help the child feel more comfortable and supported.

The second thing I want to mention is parent mental health. Parents of hospitalized children are under enormous stress. They're dealing not only with the medical situation at hand but also with financial concerns, their health issues, and everything else going on in their lives. In intensive care units, nurses often act as gatekeepers for the patient, managing the child’s care closely. But this can sometimes unintentionally interfere with the parents’ ability to care for their child in the ways they’re used to. When this happens, it can lead to what’s called parental role alteration, and that can have serious adverse effects on a parent's mental health.

Imagine a parent with a child who’s intubated in the ICU, surrounded by lines and tubes. That parent might be unable to hold or touch their child without a nurse’s assistance, which completely changes the care dynamic. It limits what the parent can do and interrupts parent-infant or parent-child bonding. This can affect children of all ages in various ways. Parents expect to care for their child in a certain way, which can be challenging when that’s taken away. For new parents, especially, there’s an expectation that they’ll be able to care for and bond with their baby, and a hospitalization turns that expectation upside down.

As therapists, we must be mindful of that when working with families. If, during your assessment, you hear something concerning or get the sense that a parent is struggling, don’t hesitate to reach out to someone on the supportive team. That might be social work, the palliative care team, or the chaplain at my facility. These team members can offer essential support and ensure that the parents are also being cared for during this incredibly challenging time.

Therapeutic Relationship

Lastly, the therapeutic relationship you build with patients and their families is significant in this setting. As I mentioned earlier, a child might not feel like they can trust many staff members, like doctors and nurses, because they often perform painful or uncomfortable procedures. However, therapists have a unique opportunity to create a supportive connection that fosters trust and can make a difference in a patient’s experience.

I’m not going to go too deep into it here, but there’s a great resource called the Intentional Relationship Model, or IRM, that dives into this topic. The model emphasizes the importance of understanding ourselves, knowing how we function, our interpersonal strengths, and our awareness of our interpersonal challenges. That self-awareness helps us build stronger, more meaningful connections with the families we work with in a way that benefits everyone involved.

We want to prioritize being trustworthy, empowering, and empathetic. These families are going through a tough time, and yes, we have a job to do, but I’ve seen firsthand how a single interaction can make a real difference in someone’s day—or even in their entire hospital stay. When I meet a patient or their family for the first time, I always try to find a point of connection. I learned this from an occupational therapist I shadowed in high school. They told me that if you can see just one thing in common, it can help you build a meaningful relationship. And I’ve found that to be true in my practice.

Even if it’s something as simple as a shared hobby, growing up in a similar place, or having the same favorite color or food, those little moments of connection go a long way. Communication also plays a huge role, and that goes without saying—but it’s still worth emphasizing. Please find out how your patient and their family learn best and how they prefer to be communicated with. Please explain what you’re doing before you do it, and offer choices when possible. Those small gestures help build trust, and that trust is foundational to everything we do.

Occupational Profile

After you’ve done all the prep work, you're ready to start your assessment. A great place to begin is with the occupational profile, a thorough interview with the patient or their family. The goal is to understand what life looked like for them before hospitalization. Knowing whether they were receiving any therapies before they were admitted is helpful. If so, how many times a week were they going? What was the focus of those sessions?

You’ll also want to ask about their home setup. Do they have one shower or two? Is it a tub or a walk-in? What was their level of independence before the admission? Were they able to complete their ADLs on their own? Were they independent with play and mobility? Did they use any equipment? Families say, “Oh, we have a shower chair from our grandma at home.” That kind of information can be beneficial for discharge planning.

Most importantly, it’s essential to determine the child’s interests. In pediatrics, motivation plays a huge role. If you can figure out what excites or engages the patient, it can make a difference in treatment and planning. I remember working with a patient who loved trains. Even on their hardest days, they would participate when we incorporated trains into the activities.

And the questions don’t stop there. As you probably know, our OT brains always process and connect information. Sometimes, a parent might mention something like their child having trouble with bath time or feeding, which opens the door to more sensory-related questions. There’s always more to learn and ask, which can make this part of the assessment exciting and tricky.

The key is to find that balance. You don’t want to overwhelm the family with too many questions, but you do need to gather a lot of essential information. It’s a delicate line to walk, and you get better at it with experience.

Components of OTPF-4

Take some time to review the OTPF. In grad school, I saw this document as long, complicated, and overwhelming. But after going through my doctorate and returning to it over the years as I’ve continued to practice, I’ve come to appreciate it. It’s such a solid guide for us and truly highlights how much falls within our scope of practice.

If you’re starting in acute care, definitely keep this document close and take the time to comb through it. It can be incredibly helpful in understanding your role and the full range of what you can do as an occupational therapy practitioner.

Considering Standardized Assessment

For your evaluation, you might consider using a standardized assessment tool. At my workplace, we don’t currently use many standardized assessments, but that varies from hospital to hospital. When deciding whether to use one and which one to choose, there are a few essential factors to remember.

First, consider the patient’s age. Is the assessment appropriate and designed for that particular age group? You’ll want to ensure it yields reliable and valid results for the client's age range. Then think about the patient’s medical complexity. Can they participate at the level required to complete the assessment? Is their current medical status likely to interfere with obtaining reliable results?

Also, consider availability. Does your setting have access to the assessment? Some tools require specific materials, like a booklet or a kit, and you’ll need to know whether or not those resources are available.

Another factor is training. Some assessments require specific training to administer, either in person or virtually. In some cases, your therapy department may be willing to cover part or all of the cost of those trainings, or provide education days so you can complete them, especially if the assessment is commonly used at your site.

And finally, there’s the need for concrete data. Sometimes you might need standardized scores to justify the services you're providing, whether for insurance purposes, to help determine eligibility for future services, or simply because a provider or caregiver is requesting a more objective measure of function. I’ve worked with patients who were showing developmental delays, and their providers wanted to understand whether they were performing above average, below average, or right where they should be. Standardized tools can be invaluable in giving that kind of concrete information.

Standardized Assessments

The assessment tools we use at my hospital include pain scales, the Sensory Profile, the Test of Infant Motor Performance—also known as the TIMP—and the Coma Recovery Scale. I want to mention that the TIMP isn’t exclusive to occupational therapy at our site; physical therapists also use it. The same goes for the Coma Recovery Scale—speech and physical therapists can also complete that assessment at our hospital.

I will focus on the TIMP and the Coma Recovery Scale because they were tools I didn’t know much about until I started working in this setting. They’ve turned out to be valuable, and I think they’re helpful to be familiar with, especially if you’re working in a similar environment.

Test of Infant Motor Performance (TIMP)

The Test of Infant Motor Performance, or TIMP, is typically used for younger infants, from 32 weeks' gestational age up to four months corrected age. At my hospital, we use it in the NICU. The assessment usually takes about 25 to 45 minutes to complete. It’s a standardized and reliable tool that evaluates posture and movement and provides helpful insights into early motor development.

A booklet will guide you through the process of administering the TIMP. The first part involves observation, where you’re simply watching the infant without intervening. After that, you move into the elicited items, which include placing the infant in specific positions and performing certain maneuvers exactly as outlined in the standardized protocol. All of this information helps you generate an N score at the end.

The TIMP does require training. I had to complete a series of online training modules to earn certification, and in-person workshops are available. If your hospital adopts the TIMP, they’ll usually provide the booklets and materials needed to complete the assessment properly.

This tool can be handy for identifying developmental delays and for predicting future motor outcomes. It also serves as an excellent foundation for caregiver education. I’ve used the booklet to highlight areas where an infant may be experiencing challenges, and then worked directly with families to practice those areas during our sessions. It’s a nice way to make the assessment feel educational and collaborative. Plus, the TIMP can support the need for continued therapy services by providing concrete data that helps justify ongoing intervention.

Coma Recovery Scale

The Coma Recovery Scale is generally used for patients between 17 and 79. Still, a pediatric version is available for children who haven’t yet developed language or motor skills. The assessment takes about 30 to 45 minutes to complete. It’s a standardized neurobehavioral assessment that evaluates several key areas, including auditory, visual, motor, oral motor, communication, and arousal functions. It’s specifically designed for individuals with disorders of consciousness, such as those with mixed brain injury or traumatic brain injury.

We’ve recently started using this tool in our ICUs, and it’s been incredibly helpful and fascinating to learn about. One of the reasons it’s so valuable is that it can help determine the appropriate intensity of neurorehabilitation in the ICU. For instance, it can guide how frequently a patient should be seen each week and what interventions might be most beneficial at that stage. It also plays a big role in discharge planning—helping the team determine whether a patient might need to transition to a rehab facility, a skilled nursing facility, or another level of care.

Like the TIMP, the Coma Recovery Scale comes with a guidebook for caregiver education. I’ve found it helpful for demonstrating to families what kinds of activities or responses to look for and how they can support their loved one’s progress even when we’re not in the room. It becomes a collaborative tool, providing structure and hope for families navigating difficult situations.

Importance of Occupation

Next, I want to talk about the importance of occupation. During our assessment—and of course during treatment too—we always want to keep occupation at the forefront. We should ask ourselves what the patient needs or wants to do that they’re currently unable to do because of their illness or injury. When we think about pediatric occupations, I want you to take a moment and reflect on your childhood or, if you have kids, think about what they love to do. Think about the fun activities, the daily routines, the social interactions, and everything in between. There are so many occupations in a child’s world, and they are rich and varied.

It’s not always easy to focus on occupation in a hospital setting. Assessments often focus less on occupation and more on the medical or physical components, saving occupation for the intervention phase. There are several barriers to making occupation a central part of the assessment. One of the biggest is that we’re working in a medical model. That environment doesn’t always support the kind of space, materials, or flexibility we need to explore pediatric occupations meaningfully. The hospital isn’t where kids are naturally eager to jump in and engage.

Time is another huge barrier. Our caseloads are heavy, and sometimes we don’t have the time to build a deeply occupation-based assessment. Space and equipment can also be limiting. We may not have the tools or environment needed to dive into real-life tasks or replicate the play and routines of a child’s everyday world. It’s just not an occupation-focused setting by nature. But even with all those limitations, we can still make a difference.

Importance of Occupation: Play

At the center of it all—yes, even for those tricky teens—is play. Play remains one of the most critical occupations for children and adolescents. It just looks different depending on the person. We must take the time to discover what’s important to each patient, what kind of play they enjoy, and what helps them feel like themselves.

We can use play therapeutically to help children regain or build new skills during their hospital stay, and to give them a sense of control and enjoyment in an environment that is not particularly enjoyable. Even offering simple choices can go a long way. I often bring a couple of toys and let the child choose which one they want to use. Even though I gently guide the interaction, that small act gives them a sense of control.

And this doesn’t just apply to younger kids. I’ve had many teens who want to play or have fun in some way—they want to find something to enjoy while in the hospital. Sometimes I’ll make up a game on the spot, bring in something they’re into, or get creative with what’s available. You don’t have to wait to introduce these elements until you’re formally in the treatment phase. Even small efforts during the assessment can have a meaningful impact.

The benefits of play for hospitalized children are truly numerous. A study by Mohammadi et al. (2021) found that children receiving treatment for cancer who engaged in play-based therapy showed increased participation in daily activities. Even more impactful, those children also experienced reductions in symptoms related to pain, anxiety, and fatigue.

When you find the right activity for your patient, it can make a world of difference. You’d be amazed at what pediatric patients are capable of, how their moods can shift, and how their overall engagement can improve. It can be a complete game changer—not just for the child, but for the entire care experience.

Case Example: Incorporating Play

I want to share a real-life situation where I incorporated play into an assessment. I was going in to evaluate a four-year-old who had been diagnosed with neuroblastoma and was admitted to the cancer unit. The child had already been hospitalized several times and was undergoing multiple rounds of chemotherapy. The medical team put in an OT order due to concerns about the patient’s strength and endurance, and it was immediately apparent that this child was struggling with medical trauma.

I completed an occupational profile with the family and then moved into observation. I noticed the patient was throwing things, and not in a playful way—more out of frustration. The parents tried to engage him, but he resisted and said no. Luckily, I brought my bag that day with key items, including beanbags and squigs. If you work in pediatrics and haven’t used squigs, you must look them up—they’re a great tool.

I started making a game where the patient could throw the beanbags into a container. He thought it was funny, so we kept going. Then we started moving around the room, tossing them to different spots. He thought it was hilarious—like he was doing something a little “bad,” which, at that age, tends to be a huge motivator. We turned it into a complete game, and before I knew it, he was up and moving, reaching, doing everything I needed to assess—all without tears.

That’s the power of play. It can completely shift the dynamic in a session, especially in a hospital setting. It opens the door to connection, function, and engagement naturally and safely for the child. That’s why keeping play central is essential, even during assessments.

Importance of Occupation: Co-Occupation

Quickly, I want to discuss co-occupation, which is highlighted in the OTPF. Co-occupation refers to an occupation shared by two or more individuals. It can happen in parallel, where each person is doing something at the same time but separately, or it can be more interactive, where they’re engaged in the task together. It’s typically considered a social occupation, and examples include eating, feeding, comforting, caregiving routines, and many others.

Involving caregivers and families in these kinds of occupations is essential, especially when working with parents of infants in the ICU. It can be significant and beneficial. For instance, if you’re completing your assessment with a young infant, you might encourage the parent to participate in a caregiving routine like bathing, changing a diaper, or feeding while you’re present. You can step back and engage in skilled observation, offering support and guidance as needed. It’s a powerful way to promote bonding, foster caregiver confidence, and gather valuable information—all while supporting co-occupation.

Pediatric Assessment: Skilled Observation

Let's dive into skilled observation, which is critical and often makes up most of my pediatric assessment. Depending on the patient population you’re working with, there may be certain specific areas to focus on. Still, generally, for pediatric patients of any age, there are several key things I’m always observing.

I look closely at endurance—how long the child can participate in an activity and whether they fatigue easily. I assess functional mobility and transfers, whether getting in and out of bed, moving to a chair, or navigating their environment. Sensory processing is another important area, including how well they regulate themselves and tolerate different stimuli. I take note of both active and passive range of motion, as well as strength. Even if I’m not doing manual muscle testing, I watch closely during functional play or ADLs to see how strength impacts participation.

I also assess vision, especially if any concerns relate to visual tracking, scanning, or alignment. Positioning becomes particularly important for non-mobile patients, where improper alignment could affect comfort, function, or safety. I pay close attention to high, low, or fluctuating tone and how it affects the child’s movements and engagement.

Finally, I observe their performance with ADLs. In the hospital setting, we usually focus on the essential ADLs for discharge—showering, toileting, and bathing. My goal is to see how the child is functioning in these areas, if they’re too young or too medically complex to perform them independently, and how their caregivers are managing those routines. These observations help guide the care plan and set realistic, meaningful goals.

Infant/Toddler Assessment

It's especially important to observe the environment for infants and toddlers. For example, if you’re working with an infant in the ICU and you notice their heart rate increasing in response to certain sounds or lighting, that’s something to note. These environmental factors can greatly impact regulation, comfort, and overall development.

This kind of observation also ties closely into neurodevelopment and motor movement. I look at whether their movements are smooth or jerky and whether those movements are appropriate for their age. Remembering the reflexes we learned in school and checking if they are present, integrated, or missing altogether is important. These can offer important clues about neurological function.

I also make sure to observe pre-feeding and feeding skills. This includes everything from how the infant is positioned to how they coordinate sucking, swallowing, and breathing. For toddlers, it may be more about self-feeding behaviors or oral-motor skills.

These observations help provide a fuller picture of where the child is developmentally and what kind of support they might need moving forward.

School-Age Assessment

One crucial area to consider for school-age assessments is behavior. This age can be particularly tough when it comes to hospitalizations. The lack of control, the unfamiliar environment, and decreased social interactions can all impact how the child engages. You might notice they’re more withdrawn, less willing to participate, or expressing frustration differently. Recognizing that these behaviors in response to the situation rather than reflect the child’s usual demeanor is essential.

Sleep is another factor that can significantly affect behavior and participation. While you may not directly observe the child sleeping, it’s essential to talk with the family about their sleep routines and whether there have been any recent disruptions. Poor sleep in the hospital setting is common, making it harder for a child to stay regulated and engaged during the day.

Fine motor skills are also key for this age group. Children typically participate in school tasks like writing, using scissors, or managing buttons and zippers. Observing their fine motor abilities can help determine how their current medical condition may affect their function and independence in daily activities. These insights are valuable for planning both immediate interventions and longer-term goals.

Adolescent Assessment

Your assessment will focus more heavily on cognitive and psychosocial areas for adolescents. You'll want to closely examine cognition, like memory, executive functioning, and attention. Social skills and mental health are also crucial at this age, including assessing their mood, motivation, and how they're coping with their hospitalization.

Another key area to address is IADLs. This can be a little trickier to assess directly in the hospital, but it’s important not to overlook it. Conversations about instrumental activities of daily living help you understand what responsibilities the teen has outside the hospital. I’ve worked with adolescents who were young parents, recovering from serious injuries like a car accident, and suddenly unable to use an arm or leg. Others had jobs that required specific skills and adaptations.

These conversations help guide discharge planning and ensure that you're addressing the broader scope of their functional needs—not just what’s required in the hospital, but what they’ll need to participate in their real-life routines once they leave.

What Next?

After you finish your occupational profile, complete any standardized assessments, and make your skilled observations, the next step is to share your findings with the family. This is an integral part of the process and helps set the tone for collaboration moving forward. I like to start by sharing the positives—highlighting strengths I noticed during the assessment. From there, I gently introduce areas where the patient might be experiencing more challenges or where I feel targeted intervention could support progress.

It’s not just about listing what’s difficult—it’s about framing it in a supportive and hopeful way. Families are often overwhelmed, so being thoughtful in communicating makes a big difference. We will go into more detail on how to approach each part of this conversation briefly, but the main goal is to establish trust and ensure the family feels heard, informed, and included in planning the next steps.

Frequency/Goals

It’s beneficial to have conversations with your patient and their family about what they hope to achieve during the hospital admission, if they’re able and ready to engage in those discussions. These conversations should always be family-centered and tailored to each patient's unique context. When setting goals, I stick with the SMART format: specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-based. It gives the goals structure and clarity and helps everyone understand what we’re working toward.

During the assessment, I also started thinking about frequency—how often the patient might need to be seen. This can depend on a variety of factors. One of the big ones is the anticipated length of stay. Is this a quick admission of a day or two, or is discharge not yet in sight? Participation, diagnosis, and the patient’s overall condition influence that decision. And of course, staffing is a real consideration. If you’re the only therapist covering a large caseload, you may not be able to see everyone as often as you’d ideally like.

Being upfront with families about what to expect regarding frequency can go a long way. In a hospital environment that often feels unpredictable, offering consistency and transparency helps build trust and gives families a better sense of what to expect.

Education

Before you wrap up your assessment, it’s crucial to immediately provide the family with any education they can use. Offering this education and collaborating with families empowers them—it gets them engaged, builds their confidence, and prepares them to care for their child once they go home. Even the simplest tasks, like touching or caring for their child in the hospital, can feel incredibly intimidating, especially when the child is surrounded by medical equipment. While we, as healthcare providers, may be used to all the lines, tubes, and alarms, this is often a completely unfamiliar and overwhelming experience for families.

That’s why it’s so helpful to break things down into even smaller steps than we might think are necessary. This can be especially critical in the ICU setting, where the medical complexity is higher and caregivers may feel especially unsure.

After your assessment, consider covering education topics like precautions, positioning, and splinting—including wear schedules and how to monitor skin integrity. You might need to go over dressing techniques if the patient has an injury that makes getting dressed difficult. For example, teaching modified dressing techniques with a button-up shirt can be incredibly helpful if a child has a broken arm.

Safety is another essential topic to address in the hospital and at home. During discharge planning conversations, you might ask about pets, stairs, or uneven flooring. If the child is unsteady in the hospital, it’s a good opportunity to talk with the family about having a nurse or support person present during early mobility. Safe sleep practices for infants and proper transfer techniques are also essential.

I often provide education on development, and any specific recommendations I’ll include in the discharge plan. I try to give as much helpful information as possible without overwhelming the family, and always emphasize that education is a form of intervention. If you spend time demonstrating and explaining things, especially when a patient prepares for discharge, that counts as skilled intervention, and you can bill for it.

It’s also important to ensure families truly understand your information. Some may learn best through written instructions, others through verbal explanations, and many benefit from hands-on demonstration. Taking the time to determine how they learn best helps make the education more effective and meaningful.

Discharge Planning

It’s imperative to begin discussing discharge planning as early as possible, right after completing your assessment. Starting that conversation early helps set expectations and prevent surprises as the discharge date approaches. Even if things may shift over time, giving families a sense of your thoughts can offer direction and help them feel more prepared.

There are several typical discharge options in pediatrics depending on the child’s needs. One of the most common is early intervention, a county or state service for children from birth to age three. These services are typically provided in the child’s home or daycare. From what I’ve seen in the hospital setting, early intervention services don’t usually start immediately after discharge—there’s often a bit of a gap—so it's important to let families know that.

Another option is home-based occupational therapy services. These are usually for patients who can’t leave their homes and need services to begin immediately. Private agencies often provide them and aren’t always available in every area, but sometimes, they’re used to bridge the gap until early intervention begins.

Inpatient rehab may be appropriate for patients who require more intensive support, especially those coming out of the ICU with significant functional needs. This does require insurance approval and is designed for patients who need a structured, intensive therapy program before transitioning home. They might stay for a week or a few weeks, depending on their progress.

Outpatient services are another discharge option for medically stable patients who can travel back and forth from home. The frequency of these services varies, but they’re for kids who still need support to reach their goals after discharge.

Part of discharge planning also includes equipment recommendations. It’s important to talk with families about what equipment might be helpful, their options, and where they can obtain it. Sometimes, you’ll be involved in helping order or coordinate those pieces of equipment, which I’ll talk more about in a few slides.

And finally, referrals are a key part of discharge planning. In my area, there’s a developmental clinic I often refer to for younger children who are showing significant developmental concerns and will likely need ongoing therapy. That clinic provides closer follow-up and can help families navigate the next steps in care once they’ve left the hospital.

Treatment

As I mentioned earlier in the presentation, things move quickly in acute care, so you might not want to wait until the next session to start treatment with your patient. Of course, this depends on your time, caseload, and how things run at your hospital, but if I can provide a short treatment session at the end of my assessment, I absolutely will. I think it’s a great way to wrap things up and build momentum.

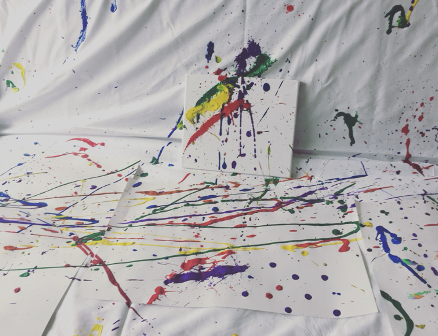

Some of the activities I’ve incorporated into that initial session include syringe painting, which is what’s shown in the photo (Figure 2), because a patient requested something fun and expressive.

Figure 2. An example of syringe painting.

I once had a patient ask if they could moonwalk, and we worked on that. I’ve played Uno with patients, supported a child who just wanted to sleep in their parent’s lap, helped a patient feed themselves for the first time, or assisted with something as meaningful but straightforward as taking a shower after an extended ICU stay.

These small interventions can make a significant impact, and when there’s time, I try to fit them in on the same day as the assessment. It helps establish trust, gives the patient and family something positive to focus on, and allows me to start contributing to their recovery immediately.

Follow Up

Once your assessment is complete and you’ve gathered all your information, following up with the rest of the team is critical. That includes the medical team, bedside nurses, and other relevant staff members. I always share what I’ve educated the family on so that the rest of the team can help reinforce it and provide consistent support. Whether it’s exercises, activities, positioning, or range of motion, that carryover can make a huge difference in the patient’s progress.

If you're recommending equipment, this is the time to start coordinating that process. At my hospital, we work closely with care coordinators who help us with equipment ordering. Connecting with the right people is essential, whether the care coordinator, durable medical equipment vendor, or someone else on the team. Sometimes, you might need to write a letter of medical necessity, and while you may not be the one submitting it, you’ll still want to make sure it gets to the right hands. Also, if the patient is being discharged soon, practice with the equipment beforehand so the family and patient feel confident using it.

I know this has all been a lot—fast and full of information—and honestly, I could talk about all of this forever. But I want to talk about something close to my heart: advocacy. In my opinion, almost every hospitalized patient could benefit in some way from occupational therapy. And that also goes for other therapy services—physical therapy, music therapy, and child life. However, since we require a medical order to provide services, we must educate staff about our role and why it matters.

I’ve seen firsthand how things change when the staff understands what we do. When they see the benefits, they’re more likely to involve us sooner and more often. Therapists aren’t just visitors who come and go—we are part of the care team, and we have the potential to make a real difference. We can help improve function, support emotional well-being, and even shorten the length of stay.

That impact is significant for children. You might be the first person to get a child out of bed after a long time. You might be the one who makes them smile again. That’s not something to take lightly. We have the opportunity to support these kids and their families through some of the hardest days of their lives. We can empower and help them feel more confident through education and collaboration.

It’s also essential to remind medical teams that early involvement matters. The sooner we’re involved, the better. Even if the patient isn’t quite ready for a full session, we can still provide education, start with small steps, and build from there. Sometimes nurses and doctors think we’re just there to “do exercise,” but we have to show them that we offer so much more. The small things—education, positioning, helping a child sit up or self-soothe—lead to real progress. Early intervention, collaboration, and education are the keys to lasting impact.

Advocacy: Why is OT Assessment Important?

And the last thing I’ll say about advocacy is that there are so many ways we can advocate for our profession as therapists, especially in a pediatric acute care setting. One of the simplest yet most impactful ways is showing up—whether for medical rounds, interdisciplinary meetings, or just being present and engaged on the unit. You can also offer in-services on topics that interest you or are particularly relevant to your team. It’s a great way to educate others and raise awareness about how occupational therapy can support patient care in ways they might not have considered.

You can take it further and help create initiatives within your unit. For example, almost five years ago, my coworker and I started a developmental care team for the pediatric cardiac unit. This initiative was designed to support the developmental needs of those patients and has made an enormous impact, not only on the families and patients but also the staff. Since then, we’ve seen a real increase in developmental care practices and awareness across the unit.

Advocacy doesn’t have to be formal. You can do education on the go—take a moment to talk to a new nurse, a resident, or anyone curious about what we do. These small conversations can add up. The sky is the limit, and I encourage you to get creative. I’ve found that the more we educate others about our roles, the more people want us to be involved. That’s how we grow our teams, presence, and impact.

That wraps up the main content of the presentation. I have a few minutes left to review my case examples and share how everything we’ve discussed blends together in real-life situations.

Case Example: Infant

One case I want to share is an infant I assessed who was three weeks old and had an undiagnosed congenital heart defect at birth. The baby was intubated shortly after being born to allow them to gain weight and grow before undergoing heart surgery. In situations like this, timing becomes critical, especially when working with medically fragile infants.

Before entering the room, I always check in with the nurse to ensure it’s an appropriate time to interact with the baby. I want to be sure I’m not disrupting their sleep, which is critical for growth and recovery. I also try to find a window where I can coordinate with the nurse or the parents to be present and involved during caregiving routines.

When I first enter the room, I take a moment to observe without touching the infant. I’m watching their vitals, scanning the environment, and observing how the nurse or parents interact with the baby. These initial moments give me valuable information—not just about the infant’s condition but also about the caregiver dynamics. Sometimes, I notice opportunities to support the parents with education or suggestions to help them feel more confident in caring for their baby.

If I join during a care time, like a diaper change, feeding prep, or repositioning, I may begin some hands-on assessment. I might assess tone, posture, or early motor responses. From there, it’s often a natural transition into treatment. This is also an excellent opportunity to foster co-occupation by involving the parents. I’ll demonstrate techniques or positioning strategies they can use, especially if they feel uncertain or intimidated by the medical setting.

In cases like this, the flow from assessment to treatment to education can happen organically. That seamless integration benefits medically complex infants in the NICU or ICU. It allows me to support the infant’s development, empower the caregivers, and build trust—all while remaining sensitive to the baby’s medical needs and timing. That’s what it often looks like when working with young infants in these high-acuity environments.

Case Example: Adolescent

Another case I want to share involves a 16-year-old who was admitted to the ICU following a cardiac arrest due to status asthmaticus. The MRI showed findings consistent with a hypoxic brain injury. When I first met this patient, they were intubated, so I began gathering all the necessary information through chart review and speaking with the nurse. This helped me understand their medical status before even stepping into the room.

Once I entered, I immediately began observing. I checked their vitals, looked at their positioning, and assessed their visual status—were their eyes open or closed? Were there any signs of purposeful movement? To understand their baseline responsiveness, I try to gather as much as possible without touching the patient first. Over the years, I’ve learned to mentally compartmentalize these observations so that I can recall what I saw when I sit down to write my notes. I remember being a student and wondering how I’d ever be able to remember everything. But with time and experience, it becomes second nature—you might see eight kids in a day and still be able to recall all the details you need.

From there, I moved into skilled observation. I gently assessed range of motion and noted whether the patient had any strength against gravity. We used the Coma Recovery Scale during the assessment for this particular case. It was a great tool, and we continued to use it across several sessions to track the patient’s progress and guide our discharge planning. The scale gave us a framework for understanding the patient’s responsiveness and helped us map out therapy goals in real time.

I also spent a lot of time with the family providing education—everything from positioning to what brain injury recovery might look like, and how occupational therapy fits into that journey. I talked to them about what they could expect from me and, more importantly, what they could do to stay involved in their child’s care. Many families in this situation feel helpless and eager to do something. Guiding them in small, meaningful ways can make a big difference for the patient and the family.

Discharge planning started early with this patient. Based on their condition at the time, I anticipated the need for inpatient rehab. But I also reminded the family that mental status can change significantly from day one to day five, especially in these cases. So we agreed to keep monitoring and adjust the plan as needed.

All the elements I’ve discussed throughout this presentation—chart review, environmental observation, skilled hands-on assessment, caregiver education, discharge planning—came into play here. If you’re new to this setting, don’t hesitate to bring a piece of paper and jot things down as you go. Let families know if you need to pause and write something. I often tell them, “I just need to take a few notes so I don’t forget anything,” and they appreciate the honesty and transparency. It helps build trust and shows that you're fully invested in their care.

Summary

That's all of the content that I have for you today. I hope that this was helpful and you guys learned something new.

Questions and Answers

I'm a school-based OT with 10 years of experience and little hospital or acute pediatric care background. What are some first steps for transitioning into this setting?

One great way to start is by getting per diem experience in a hospital or long-term care setting to get your foot in the door. Have your reference materials handy, and reach out to a mentor—maybe someone from your graduate program or a friend in the field. When you’re starting, there’s a lot you won’t know, and that’s okay. Learn as you go, take notes, and collaborate closely with physical therapists, speech-language pathologists, and others on the team. If you already understand how to work with children, that’s the hardest part. Hospital-specific knowledge will come with time and experience.

How often do you see patients in a pediatric acute care setting?

In my hospital, we’re fortunate to be staffed well, so I often see patients multiple times per week. It depends on the hospital, though. Many of the kids I work with are admitted for extended stays, which allows me to provide consistent follow-up and treatment.

Do you ever find that parents are a barrier to therapy in pediatrics?

I was nervous about this when I first started, and while it can happen, it’s more about the context. Parents are under a lot of stress, and seeing their child in pain is incredibly hard. Building trust early makes a huge difference. Be flexible—sometimes that means adjusting your session plan, coming back at a different time, or scaling things down. Parents who trust you are more likely to be supportive and involved.

What’s the typical frequency of occupational therapy in pediatric acute care? Do you ever see patients more than once a day?

The most common frequency at my hospital is two to three times weekly. That can vary depending on the patient’s needs—some may only need to be seen once a week, others up to five times. In the NICU, therapists specializing in feeding often see patients more frequently. I don’t usually see patients more than once a day unless specific discharge needs require extra support.

References

See the additional handout.

Citation

Malvasi, A. (2025). Navigating assessment in pediatric acute care, infants through adolescence. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5801. Available at www.occupationaltherapy.com