Introduction

Jenn and I are very excited to have this opportunity to present today. As we get underway, I wanted to share a very personal case study to highlight a family-centered perspective. Jenn will also be sharing another case study towards the end of today's presentation.

Family-Centered Perspective: Andrew's Story

Christina: Andrew's story is really the foundation of our foundation.

Figure 1. Andrew's journey.

His experience in our family-centered perspective is what inspired this work and the resulting collaboration between occupational therapy and child life. Six years ago, my smiley active five-year-old son became sick with a typical childhood virus. He stayed home from preschool and had a fairly routine and uneventful appointment with his pediatrician. Within 24 hours his symptoms worsened, and we took him to our local community hospital for further evaluation. The closest pediatric hospital or pediatric urgent care center was about two hours away from our home. He was hospitalized with pneumonia, started on IV antibiotics, and was admitted overnight as a precautionary measure. By the next day, his symptoms continued to worsen, and I began to feel uncomfortable with the level of care he was receiving. I began to demand quicker assessment by the attending pediatrician that was on call that day. Upon her evaluation, she determined that his condition was rapidly deteriorating and that he required specialized pediatric intervention at Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Delaware. He was airlifted and arrived before we could get there by car. The scariest experience of my life as a mother was certainly underway.

A spiral of increased anxiety and intensifying respiratory distress resulted in the requirement of intubation and multiple days of ventilator support to stabilize his medical condition. After placement of an NG tube, an NJ tube, a central line, and the administration of countless meds in the PICU, further testing revealed that he had contracted H1N1 flu which was contributing to his multi-organ complications.

Let me just say that COVID-19 has been a very unwelcome trigger of many of the fears that our family experienced during that time. This included child and parent separation anxiety largely as a result of Andrew's medevac flight, displacement from our home about two hours away, separation from his sister and our daughter, the coordination of care for our daughter that was required while we managed Andrew's hospitalization, medication errors, and his father becoming ill several days into Andrew's hospitalization which required his home isolation and further precautions with our daughter.

If we flash forward to post-hospitalization just for a moment, beginning around three weeks post-hospitalization, Andrew began to experience traumatic stress reactions, emotional outbursts, episodes of rage and aggression, elopement attempts, self-injurious and self-deprecating language, and nightmares that re-experienced his hospitalization. This disrupted his home functioning and his reintegration back to daily routines and his school routine.

If we go back to his hospitalization, there were many moments of hopelessness, primal fear, and trauma, but there were also moments where his life-threatening condition also became life-altering. We deepened our faith, found tiny moments of inspiration and hope, stopped caring about the small stuff. We clung to the big but very simplistic goal of going home.

One morning during PICU daily rounds, Andrew's attending physician indicated that he would survive, but it was still too early to know what his recovery might look like. Still intubated and sedated, my mama bear/occupational therapist's wheels started spinning or possibly even raging. How do I help my son understand this medically complex situation? "When they began to wean his sedatives, he will just want to go home. He is five, and he does not understand time well especially in an unfamiliar hospital environment." I called a dear friend and asked her to "do a craft project" to which she giggled, "Only an OT would ask for such a request." I asked her to make a map with a symbol of the hospital as the starting point and a photo of our home at the finish. I also asked her to add Velcro to the road and to a matchbox car. Andrew still to this day loves cars and trucks. It became a visual representation of his journey and a source of dialogue and rapport building with many members of his medical team. I remember one particular exchange like it was yesterday. His respiratory therapist, Brian, came into his room to administer a treatment, Andrew was still intubated and unaware, but as Brian got up to leave, he pulled off the car and advanced it forward. He said, "Buddy, you've already rounded that bend." I stared at it for hours. "Yes, you've already rounded that bend." Our sense of hope began to improve, and I felt empowered to be actively engaged in whatever discharge plan lay in front of us.

This was our starting point and what inspired the development of the tools and methods that blend art, therapy, and functional communication to ease anxiety and encourage children and families that are facing medical challenges.

The Trend Toward Increasingly Complex Discharges

- Discharging with High-Acuity Needs

- Learning and Processing Information is Challenging for the Child and Family

- Increasingly Complex Information & D/C Instructions

- Environmental Considerations

- Caregiver and Family Transitions

As we move into some of the data that highlights the need for therapeutic strategies that enhance child and family-centered communication and discharge planning, we think it is important to note the trend towards increasingly complex discharges. We know that patients are discharging with higher-acuity needs and that learning and processing information is challenging for the child and family particularly auditory processing during periods of anxiety and when overwhelmed. We know that they are receiving increasingly complex information and discharge instructions as medical care advancements are made. How many written materials and handouts are typically provided to our patients and families? We also know that they often have challenging environmental considerations as well as necessary caregiver and family transitions.

Research Review: Pediatric Discharge Data

- Each year one in four children will receive medical care for an injury, resulting in millions of emergency department visits & hospitalizations.

- Nearly one of every six discharges (5.9 million) from US hospitals in 2012 was for children aged 17 years or younger.

- On average, pediatric patients stayed in the hospital for 4 days (3.9 mean length of stay, days), with an average cost of over $6,000 per stay and accounting for 37 million in aggregate hospital costs (Witt, Weiss, Elixhauser, 2014).

- In recent years, there have been significant increases in the number of admissions for children w/ chronic conditions, a 6% increase 2010-2016 (Bucholz, Toomey, Schuster, 2019).

Each year one in four children receives medical care for an injury. This results in millions of emergency department visits and hospitalizations. Nearly one out of every six discharges, about six million from U.S. hospitals in 2012, were for children ages 17 years or younger. And on average, pediatric patients have an average length of stay of about four days with an average cost of over $6,000 per stay. We also know that in recent years, there have been significant increases in the number of children admitted with chronic conditions. Freestanding hospitals, or children's hospitals specifically, are where services are designed for children and which operate independently of adult-focused institutions. In general hospitals, on the other hand, care may be provided in a general inpatient bed, a dedicated pediatric ward, or a children's hospital that might be nested within a hospital, but it often shares resources with adult-focused services.

- Substantial variability exists within settings of pediatric hospitalizations.

- In the US in 2012, 2 million pediatric hospitalizations, more than 70%, occurred in a general hospital (Leyenaar et al. 2016).

- 3,866 hospitals were general, 70 were free-standing.

- While every child’s discharge looks quite different, pediatric standards published in 2014 in the Journal of the American Medical Association indicate that high-quality, family-centered guidelines and processes can indeed be applied broadly, while still leaving room for individualized planning.

In 2012, about two million pediatric hospitalizations occurred in a general hospital. Of over 4,000 hospitals in the U.S., 3,866 are general hospitals and 70 are freestanding pediatric children's hospitals. We know that many children and families are often displaced from their home environment and their support systems to access the specialized medical care that is required in a freestanding children's hospital, or if they remain in a community based general hospital, they may or may not have access to the same child-centered services. There are resources in place within those two different settings, but how can we help to bridge the gaps? While every child's discharge looks quite different, pediatrics' standards that were published in 2014 in the Journal of the American Medical Association indicate that high-quality family-centered guidelines and processes can indeed be applied broadly while still leaving room for individualized planning.

Trauma-Sensitive Considerations

- Currently, more than 46% (~34 million) U.S. children under age 18 have had at least 1 adverse childhood experience (ACE), and more than 20% have had at least 2 ACEs.

- Pediatric medical trauma as an ACE

- Risk Factors for persistent traumatic stress reactions include prior traumatic experiences or behavioral problems, more severe pain or exposure to frightening sights and sounds while in the hospital, subjective sense of life threat and injury/illness severity, and more severe early traumatic stress reactions.

- Parent presence and support, as well as a positive peer support system, appear to serve as Protective Factors. https://www.healthcaretoolbox.org/research-summaries.html

Jennifer: I am going to talk about some of the data surrounding trauma-sensitive considerations. As you can see, the data currently shows that the number of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) is really quite high. The CDC defines ACEs as stressful or traumatic events, including abuse and neglect. Additionally, higher ACE scores are correlated with increased risks of some diseases as well as social and emotional problems. There are a number of risk factors that can lead to a high ACE score. However, medical trauma is typically not even assessed as part of a person's ACE score really leading us to believe that these numbers might actually be even higher. However, there are some protective factors for ACEs that can help prevent some of those symptoms including parental presence and support, particularly during that health care experience.

- Post Intensive Care Syndrome (PICS):

- Advancements in critical care medicine and consequently, the improvement in survival after a critical illness has led clinicians to discover the significant functional disabilities that many surviving patients experience. This has led to further research that is focused on improving the long-term outcomes for critical illness survivors and their functional recovery.

- PICS is defined as a new or worsening impairment in physical, cognitive, or mental health status arising after critical illness and persisting beyond discharge from the acute care setting.

- The psychological health of family members of the survivor may also be affected in an adverse manner, termed as PICS-Family (Rawal, Yadav 2017).

- Post Intensive Care Syndrome (PICS):

- Of the more than 5.7 million individuals admitted to ICUs each year in the US, According to the Society of Critical Care Medicine, PICS affects:

- 33% of all patients on ventilators

- Up to 50% with an ICU length of stay for at least 1 week

- Of the more than 5.7 million individuals admitted to ICUs each year in the US, According to the Society of Critical Care Medicine, PICS affects:

An additional area of research has been on post-intensive care syndrome or PICS. Due to the advancements in critical care medicine, there has been a lot of improvement in survival rates after a critical illness or an injury. Obviously, this is very positive. However, there are some negative consequences including significant functional disabilities that may include new or worsening impairment in physical, cognitive, or mental health status. There is also a term known as PICS family which is when the psychological health of family members of the patient is affected in an adverse way as well. Research has found that PICS affects 33% of all patients on ventilators and up to 50% of those with an ICU stay of at least one week. These are high numbers of patients being affected.

- Pediatric Medical Traumatic Stress (PMTS):

- Defined as “a set of psychological & physiological responses of child and their families to pain, injury, serious illness, medical procedures, and invasive or frightening treatment experiences” (National Child Traumatic Stress Network, 2003).

- PMTS includes traumatic stress responses, such as arousal, re-experiencing, and avoidance, which can vary in intensity and disrupt functioning (Kazak et al., 2005).

Another concept we wanted to discuss related to trauma-informed care is pediatric medical traumatic stress also known as PMTS. While traumatic stress reactions associated with pediatric medical events began to be described in the mid-1980s, the first large multi-site study was completed in the mid-1990s and was specific to childhood cancer survivors through Anne Kazak's work. She is a pioneer for the trauma-informed care work that we are going to be discussing. Since the mid-'90s, research has continued to expand in this area. The work has highlighted the significant impacts on patients including the loss of recently acquired developmental skills, some regression, the onset of new fears or reactivation of old fears, reckless behavior, separation anxiety, and psychosomatic complaints such as stomachaches or headaches. It is also interesting to note that in some children, particularly younger children, they may experience hyperactivity distractibility and increased impulsivity which sometimes can be confused with ADD symptoms or ADHD symptoms.

- The Integrative Model of PMTS (Kazak et al., 2005) emphasizes a family-centered perspective, and the need for assessment and intervention, for parents, as well as siblings.

- Highlights the hallmarks typically present life threat, and/or the likelihood of an event evoking fear, horror, and helplessness (American Psychiatric Association, 1994).

- It notes, however, that the symptoms of PMTS are more strongly correlated with subjective experiences than objective characteristics of a particular illness or treatment course. (Kazak et al., 2005)

In Anne Kazak's work, she talks a lot about an integrative model of the PMTS that takes a family-centered approach and identifies the need for assessment and intervention for the entire family including siblings. When using the traumatic stress model, it is less important to identify experiences as objectively traumatic and more about the subjectivity. We want to know how that patient and the family themselves perceive the experience. This can include their perceived level of threat to their life, the likelihood of the event evoking fear, and the overall level of helplessness that often patients and family members do experience through hospitalization.

Figure 2. Dad actively involved in son's care.

Overall, the healthcare team should be keeping in mind that subjectivity plays such a large role in the patient and family's experience as well as all members of the healthcare team. We need to continue to assess the patients' and families' perceptions of their individual experiences and then provide support based on that. We also need to make sure that the support is both normalizing and non-stigmatizing.

- This model advocates that PMTS be addressed:

- In the delivery of acute medical treatment (by changing the subjective experience of Potentially Traumatic Events (PTE)

- After the delivery of medical treatment (to prevent the symptoms of PMTS)

- By primary care health providers and educators to identify ongoing concerns & link the family with resources upon community & school re-entry (to reduce the symptoms of PMTS).

- As research continues to emerge, it is important to note that greater understanding, prevention, assessment, and intervention has the potential to help children and families develop adaptive long-term outcomes after traumatic experiences.

- Post-Traumatic Growth (PTG)-Resiliency research is expanding.

- How do we help inspire & promote this trajectory among families?

Pediatric medical traumatic stress (PMTS) needs to be considered while patients are receiving their medical treatment as well as after they have received that. After discharge, things do not automatically just go away. As Christina mentioned, she experienced many things with her son long after their hospital stay had ended. These ongoing concerns should be monitored by the parents, primary caregivers, and even the primary care health providers. Anyone who has spent a significant amount of time with the child and knows what their baseline is should continue to keep an eye on things and monitor behaviors.

One of the most encouraging aspects that is referenced in the current literature is that positive outcomes can result after traumatic events. It is sometimes referred to as post-traumatic growth. This can include positive changes in self and relationships with others which really indicates the development of resiliency. Resiliency can be impactful when the child experiences future challenges, whether they are medically related or not.

The Get Well Framework

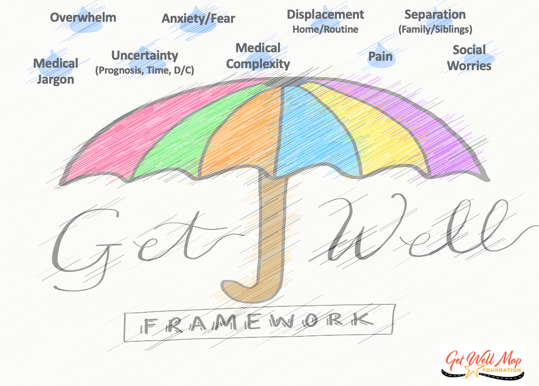

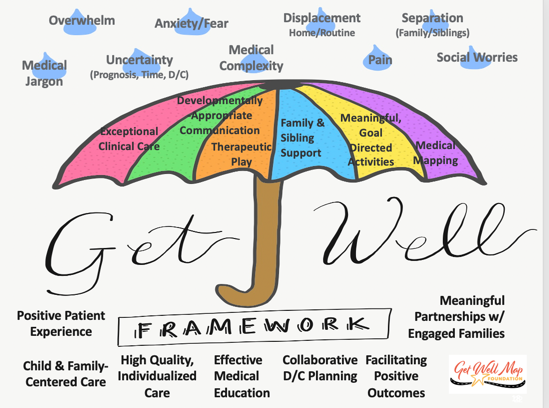

Christina: This is really the result of Occupational Therapy and Child Life collaboration in this work. This is the Gel Well Framework as seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Get Well Framework.

As we showcase this framework, we really want to be thinking about the function of an umbrella. What is observable? Does it function? Does it keep us dry? Do we notice colorful patterns of fun and bold colors on an otherwise dreary day? Our therapeutic interventions will be illustrated as the water-resistant fabric panels and our pillars of integrity which are going to be illustrated as the ribs of our umbrella to help to shield many of the stressors, the raindrops that children and families experience during life's difficult storms. We know that medical teams may not be able to eliminate all of these stressors but we do serve a role in helping to keep them dry.

The raindrops are the negative stressors that occur during hospitalization (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Negative stressors.

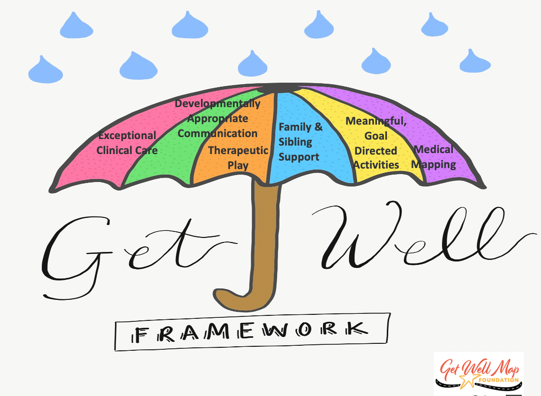

These are many stressors that children and families experience during childhood hospitalization referred to earlier in our family perspective. The next piece is where we are going to spend the bulk of our presentation. This is focusing on therapeutic interventions. What did we provide? Did it lead to a positive outcome? These are outlined in the umbrella in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Therapeutic interventions.

These are the aspects that are most observable and felt by children and families. They promote positive outcomes within our healthcare organizations.

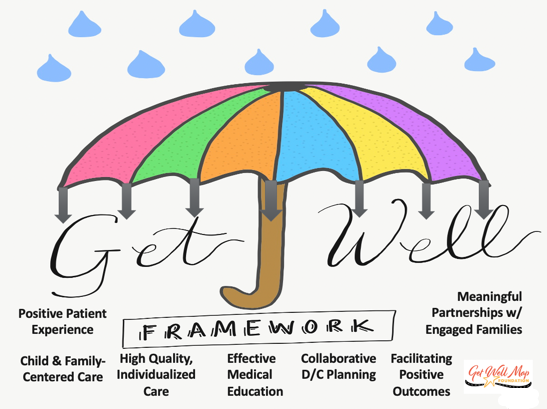

The next piece is these pillars of integrity that I mentioned and these are the outcomes that healthcare organizations try to measure to determine if our interventions were effective. They give our therapeutic interventions their strength, their shape, and their integrity, and when they are in place, they further enhance the effectiveness of our therapeutic interventions (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. Pillars of integrity.

They may be largely unobservable to children and families when the system is working cohesively, but they are felt significantly by children and families when a rib is bent or broken as it will impact the functionality of the entire umbrella. Figure 7 shows the framework in its entirety.

Figure 7. Overall framework.

As we go through this, we are going to start with exceptional clinical care.

Therapeutic Intervention: Exceptional Clinical Care

- Evidence-Based Diagnostic Methods

- Evidence-Based Treatment Protocols

- Clinical Judgement & Decision-Making

- Staff Consistency

- Individualized Care

We could spend an entire webinar just focusing on this piece. It is very specific to different disciplines. We know that our clinical care must include evidence-based diagnostic methods, evidence-based treatment protocols, excellent clinical judgment, and decision making. Staff consistency is critically important in the delivery of care as well as the ability to provide individualized care to children and families. Figure 8 shows the complexity of care.

Figure 8. The complexity of care.

And I'm going to turn it back over to Jen for the next few slides.

Therapeutic Intervention: Communication

- Need for multi-sensory learning strategies and medical education in healthcare settings:

- Child- and Family-Centered

- Developmentally-Appropriate

- Rising numbers of children with Autism Spectrum Disorder, ADHD, auditory processing disorder, sensory processing disorder

- Language barriers

- Medical jargon

- Multiple Team Members with Various Communication Styles

Jennifer: I am going to talk a little bit now about communication. Good communication is extremely important, particularly in healthcare settings. This communication should take a multi-sensory learning approach in order to ensure that the communication remains child and family-centered as well as developmentally appropriate. When thinking about potential barriers to good communication in healthcare settings, staff should be proactive in preventing issues. For example, resources should be utilized for language barriers. I think it can be easy to fall into the habit of using a child to translate or speak directly to the family member in the room who does speak English, thinking that they will translate for you. However, this is not an acceptable means of communication and really should not be utilized unless the family is requesting this.

Additionally, in healthcare, many people understand that medical jargon should be avoided when talking to patients and families. This can be easy to forget as some phrases become second nature to clinicians but it still at the end of the day might not be understood by patients and families. For example, the term NPO or nothing by mouth is something often used. I hear it many times a day, but families may not understand what that means. Every team member has to play a part in this and help families understand. It is also important to read their body language because sometimes families are not comfortable sharing that they do not know something, or they might assume that they should already know that information. They may feel dumb or inadequate.

Another thing to keep in mind is that all team members are going to have different communication styles. This is okay, but this can get really challenging when patients who have more complex needs have a really large care team or when they are moving from one unit to another within the hospital. It is really helpful to keep this in mind and acknowledge this with families. Talk with your co-workers to find out what works best for the family or what were some things to perhaps avoid.

Promoting Developmentally-Appropriate Communication

- Translating medical jargon

- Helping children identify tangible, child-centered goals

- Helping children and families understand interdisciplinary goals/medical education

- Medical Rounding: support before/during/after

- What to do when a “setback” occurs

Promoting developmentally appropriate communication is really important. We also need to keep an eye on body language when speaking to patients and families to help assess if they are understanding or absorbing all of the information. Sometimes patients and families are not comfortable expressing how they are feeling about the learning process or understanding even simple directions. A medical mapping tool (see Figure 9) can be helpful in these situations to partner with the patients to help them be able to identify their goals and their wishes and to have a say in what is happening to them.

Figure 9. Example of a medical mapping tool.

It is important to identify what their goals are, what goals they have control of, and what goals they do not, especially for older patients. This is also good for younger patients to have them pick a couple of things to focus on. For example, there might be some medical goals that the team has for caregivers but maybe not necessarily the patient. These things need to be completed prior to discharge. The patient does not necessarily have control over that, but their parent or their caregiver really needs to make sure that they have all that information. This can help to track not only the goals but who is responsible for those goals as well.

It is also important to monitor the progression of the goals and adapt accordingly when goals change. If there is a medical setback, there needs to be a rest stop or a pause. The patient does not move forward in their progression, but they understand that they are not moving backward either. It is important to differentiate between the setbacks that potentially could be impacted by the patient if they are not keeping up their end of the deal and the ones that are out of the patient's control. This could be a fever or something medical.

Another way to really promote good communication is during medical rounding. It can be helpful to use this time to monitor goals and ensure that patients and families are understanding the information they are receiving. We want to make sure their questions are being addressed as well. Some families find it helpful to have a designated person to provide specific support before rounding to identify what questions they would like to ask and what to expect from the experience. This is an extra person to hear and absorb information, and then after rounds, assess the caregivers' level of understanding and relate it back to what those identified goals were.

Therapeutic Intervention: Therapeutic Play

- Types of Therapeutic Play include:

- Emotional Expression

- Instructional Play

- Medical Play

- Therapeutic Play allows children to:

- Express feelings or concerns

- Become familiar with medical equipment

- Increase understanding

- Learn and practice coping techniques

- Re-enact healthcare experiences

- Develop feelings of mastery

- Communicate fears

- Ease and clarify misconceptions

Now we are going to move into the next area which is therapeutic play. Therapeutic play in the healthcare setting is something that can allow children to express their feelings or concerns. It is an excellent tool to help them become familiar with medical equipment, increase their understanding of what is happening, and who they are meeting. It helps children to learn and practice coping techniques for challenges they may face everything from experiencing a painful procedure, coping with chronic pain, and a wide variety of other hospital experiences. It can also provide a sense of control and mastery for patients to reenact or better understand something. Figure 10 shows an example.

Figure 10. Reenacting a medical procedure.

It is also a really great way for the child to communicate any fears they might have or misconceptions they might have. Providers can then work through that with the child even at a very young age.

There are three main types of therapeutic play and they all have very similar goals. There is emotional expression which obviously helps patients express what emotions they are feeling. There is instructional play that has a goal of developmentally appropriate education specific to a procedure or a new diagnosis. Lastly, there is medical play. This is utilizing all of the medical supplies, whether they are real or pretend especially for the younger kids to help them understand the things that they are seeing. These different types of therapeutic play all overlap and have similar effects on patients and other children such as their siblings which can be really beneficial.

- Research provides evidence for the effectiveness of therapeutic play in reducing psychological and physiological stress for children facing medical challenges.

- Therapeutic play offers long-term benefits by fostering more positive behavioral responses to future medical experiences.

- Since childhood play transcends cultural barriers, play opportunities should be provided for children of all ages and backgrounds.

It is important to note that the research indicates that therapeutic play has a positive impact on the reduction of psychological as well as physiological stress for children. It is important for everyone to advocate for therapeutic play as a tool for fostering those positive behavioral responses as it can greatly impact their future medical encounters. A negative medical encounter can keep playing out in future encounters. However, if we stop the cycle and provide some therapeutic play, we might be able to help that child process all that happened to them to hopefully have better experiences in the future or at least be less frightened by the possibility. Additionally, we know that play does not have cultural barriers so it can really be utilized with children of all ages and backgrounds. Again, it just makes it an extremely effective tool when working with patients and their families.

- Medical Preparedness and Education

- Partnering with caregivers & siblings

- Assessing Readiness & Communicating with the Team

- Guiding, Modeling & Facilitating Therapeutic Play with Families & Staff during hospitalization & after discharge

- Red Flags to look for beyond D/C

These interventions tend to be on a continuum in which medical play and preparation sort of converged organically. This is meeting the child where they are in identifying what would be the most helpful to them at that moment for that situation. It is really important to include the entire family, particularly siblings, to assess what they know and therefore be able to anticipate any gaps in education. It is also important to provide education and guidance to caregivers and staff, especially staff who are present for longer periods of time with the patient. There are huge benefits of continuing this play during and even after a healthcare experience.

A specific type of medical play we often use is needle play. We allow patients in a very safe and specific manner to utilize needles on a doll or a stuffed animal. This can be frightening for families or for the children, particularly if they have had really poor experiences with needles in the past. This can be something that takes a while to gain their confidence and trust. This is something they can act out. Figure 11 shows needle play.

Figure 11. Practicing with needles.

Let's talk about how we are going to do this safely and guide families because sometimes there needs to be that little push. Not all kids are going to just jump right in and want to participate in exploring all the different medical tools. In terms of the discharge planning process, it really can be a great way to assess that everyone in the family is on the same page and on the same page as the medical team as well. This can help to identify any red flags that might be existing.

Often, I will encourage the continued use of these play interventions after the discharge process and really educate families on what to look for in this play. I suggest families keep an eye out for anything concerning. For example, I will send a medical play kit home with a family and ask them to put it near their typical toys to see if they gravitate towards it. Or, do they throw it in the other room and do not want to see it? Are they refusing to touch any of that medical equipment? It does not have to be the day after hospitalization or even the week after, but after a few weeks, see what they do with it. If they do not want to play with it, this could be a sign that the child is really struggling to process their hospital experience. This is how we noticed that families might benefit from additional support.

Therapeutic Intervention: Family & Sibling Support

- Caregivers know their child best, although stress and demands of hospitalization can compromise their confidence in their caregiver roles

- Challenges of having a hospitalized sibling/child

- Disruption of the family unit and daily routines

- Emotional hardships

- Adjustment problems

- A shift in family boundaries

- Important to incorporate the entire family in the hospitalization, including the discharge planning process.

- Roles often shift due to hospitalization and again upon discharge.

Another really important area to focus on is family and sibling support. It is paramount to remember that all members of the family are impacted by hospitalization. If we think back to Christina's story in the beginning, she mentioned her husband and her daughter were affected.

The staff takes the caregivers' lead on how to interact with the patient because we know that parents know their children best. We hear that all the time. However, it is important to remember that the stress and the demands of hospitalization could really make it difficult for them to be able to accurately and appropriately provide information or support to the staff members. They can have feelings of embarrassment if they recognize this. There can also be internal pressure for them to know how to handle their child in this situation. They feel like they should be in control. We need to give them the grace to accept that that is okay. We understand that not everyone is able to do that in their situation.

Siblings are an area of passion for me. There is so much research on this topic. There are numerous challenges that are associated with having a hospitalized brother or sister, whether it is for a very short hospitalization or for an extended period. Some of the most common challenges are pretty intense. They include sadness, fear, loneliness, jealousy, resentment, embarrassment, guilt, feeling isolated from their peers or their family members, and confusion surrounding their sibling's illness. It is really common for roles to shift during hospitalization and after discharge as well. Often, older siblings might need to take on more of a parental role, and the rules and norms might change within the family. The hospitalized child is positioned in more of a central role of importance causing a lot of feelings of distress or confusion in the family. These changes can have long-lasting effects on family dynamics. And, this impacts all families differently.

- Education and Family Engagement

- Teach back method

- Amount of information

- Active listening

- Goal Setting

- Previous transitions within the family

- Siblings

- Current understanding/current needs

- Inclusion in teaching and offering support

- Assessment for additional needs-Recognizing needs beyond your scope of practice

- Resources

- Short-term (during hospitalization and medical care)

- Long-term (beyond discharge)

In order to help support the entirety of the family, there are a variety of methods that have been proven to be successful. First, there is a lot of evidence for the teach-back method. It can be used with patients as well as adult caregivers. It is an effective strategy that encourages engagement in the learning process. It is also helpful to provide a small amount of information at one time to allow families to process the information and have an opportunity to ask questions throughout. Active listening is so crucial and helps engagement with families. It can be helpful to ask questions such as, "What have you tried as a family in the past to help prepare your child for something big?" When talking specifically about that discharge planning process, you want to help them to connect to something that they have previously experienced even if it was not in a medical setting.

It is important to go back to those goals. You are going to hear that word so often throughout this presentation. Goals are so important, and we want to make sure that those goals are constantly being incorporated to make sure that everyone is understanding. Yes, the goal is to get healthy and to get home, but let's break it down a little bit more and look at specifically what we are working towards. It is helpful to be creative when engaging with patients and families to help them to make those connections and make the information to stand out to them.

It is also important to find out what the siblings understand. We want to normalize those reactions and make sure they do not feel alone in this. I often say, "This is what I see." Or, "Other siblings have told me this." This can help families feel a sense of normalcy. When offering to provide support, it is also helpful to think about what appropriate timing looks like so that caregivers are not overwhelmed. The first date might not be the best time to talk about siblings, and that is okay. There might be a lot of other things going on, but this needs to slowly start to be embedded in conversations. It is also important to think about what caregivers have already shared with siblings. You can ask them how they normally share information with their children at home. Again, this assessment is important even if it is totally unrelated to the healthcare experience. When you are providing education to patients include the siblings so that they feel part of the process, and they are hearing the same information. If you are not able to incorporate the sibling in the process, the next time try to get them in the same room as the patient and have the patient teach them. You can then get a sense of what they know, and they can feel proud of this knowledge.

Overall, you need to have patience as there is only so much information that even patients and caregivers can understand all at once. And, it might require multiple sessions to get all of the information across. If the siblings' needs are beyond your scope, utilize your team to provide additional resources to the family. Many times there are other psychosocial care members on the team that can provide resources. Bibliotherapy is something that I use all the time. There is a book for just about everything whether it is diagnosis-specific or another experience in the hospital. Support groups are great as families can share their experiences and provide a sense of normalcy.

Therapeutic Intervention: Meaningful, Goal-Directed Activities

- Incorporating Therapeutic Play into Meaningful, Goal-Directed Activities

- Functional Activities

- Activities of Daily Living

- Functional Mobility

- Play/Leisure

- Establishing Goals

- Measurable STG & LTG

- Meaningful Child and Family-Centered Goals

(Stoffel et al., 2017)

Christina: To build on Jenn's points on therapeutic play and family sibling support, we are going to talk about the fifth therapeutic intervention which is meaningful, goal-directed activities. As OTs, this is so critical to the care that we provide, but we have to recognize that during an acute hospitalization the focus is often on caregiving. This is providing care to make tasks easier especially when a child is in pain or there is a fear response. And oftentimes, this becomes the primary focus of parents and caregivers in those situations. There can also be gaps in expectations among families and staff members. Of course, there are also cultural differences in parenting roles and response to illness. Thus, incorporating therapeutic play into meaningful goal-directed activities is important. How are we building those goal-directed learning and performance opportunities into functional activities, activities of daily living, functional mobility, play, and leisure tasks? How are we establishing goals around this?

Promoting Meaningful, Goal-Directed Activities

- Provide opportunities for choice and control in unfamiliar environment & situations

- Promote enhanced independence in preparation for discharge and/or transitions

- Encourage & motivate children & families to work towards skill development from a “modified normal”.

- Teach skills needed for successful re-integration to home/school/community environments

We create goals all the time. As OTs, it comes very naturally for us to adapt and grade activities. However, families are usually focused on the long term goal of hospitalization. Given the level of stress and anxiety, they need their healthcare team to break down and scaffold those short term goals for them.

It is important to provide opportunities for choice and control in unfamiliar environments and situations. Give them two to three choices of clothing, food, options, games, music, etc. Try not to overwhelm them with open-ended questions but just provide two or three choices that help reestablish that sense of control.

Jennifer: As Christina was saying, we really want to encourage and motivate children and families to work towards that skill development from a modified normal. It is really important to teach skills that are needed for that successful reintegration to the home, school, or community environment.

Therapeutic Intervention: Medical Mapping

- Families often have difficulty navigating evaluation and treatment courses and require facilitation from healthcare professionals for guidance & empowerment

- Use of child-friendly themes tailored to the child’s interest to increase engagement & normalization of healthcare experience.

- Use of photographs or illustrations to enhance personalized goal setting & individualized care that is visible to the child and family

- Use of a “Neutral Zone” to encourage consistent, developmentally-appropriate communication during medical setbacks or delays in progress

- Milestone markers to highlight individualized aspects of medical experience & incorporate interdisciplinary goals

Medical mapping is a therapeutic intervention that is obviously near and dear to Christina and my heart. Families can really have difficulty when they are evaluating the treatment course. There are so many unknowns and often no specific information. There may not be a discharge date. Although we know that it is coming, this can feel really frustrating to not have specifics, particularly for young children. These medical maps can help to provide guidance and empowerment to reduce their frustration. This is something that is tangible that the patient can understand.

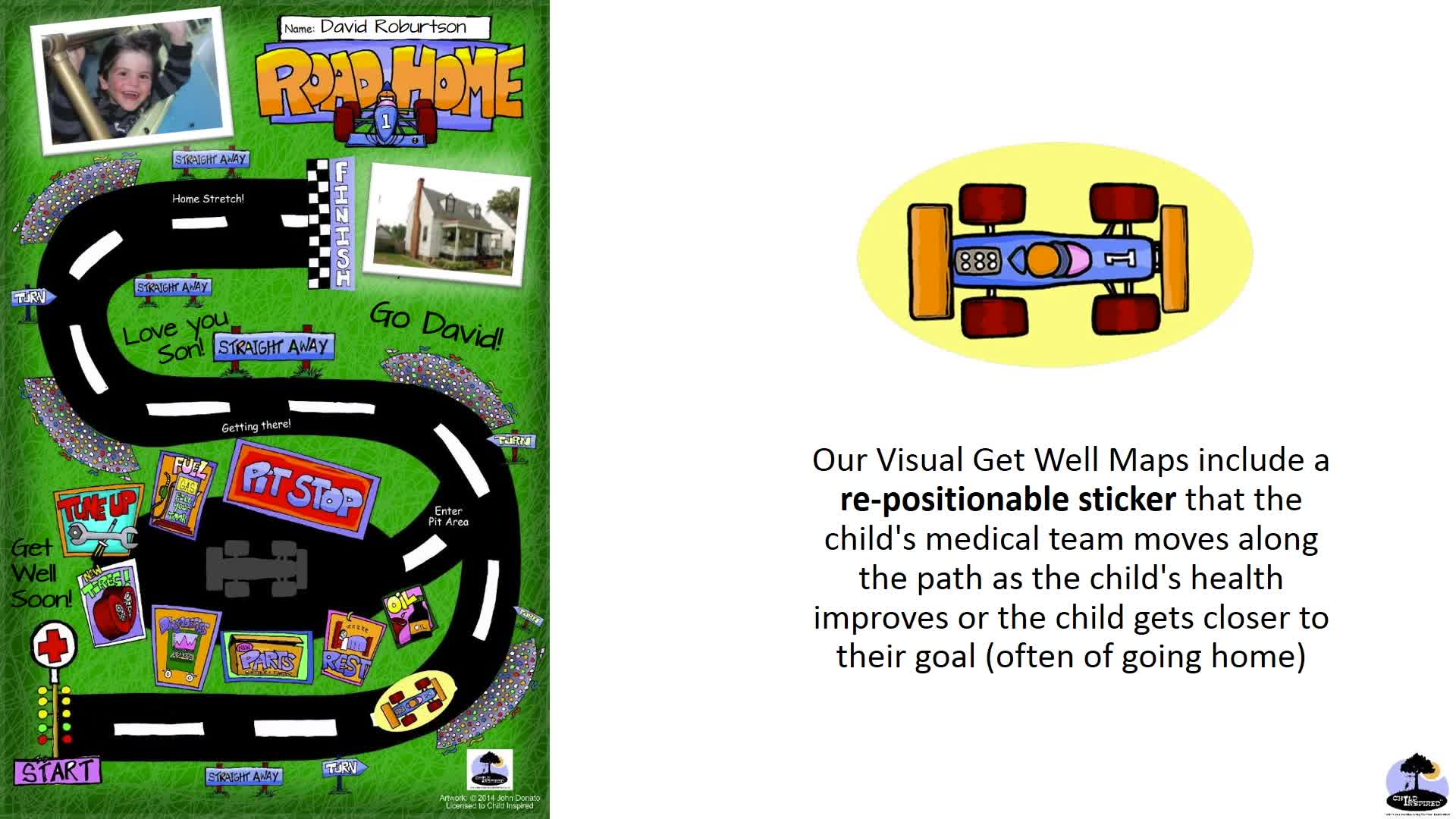

Here is one example of a child-friendly theme in Figure 12.

Figure 12. Car road map.

This one has race cars. There is one that is under the sea and another with a princess on it. You can choose what is appropriate for that patient. Using pictures or illustrations, they can personalize the board. This is something that we encourage patients to do. They can put a picture of themselves, a picture of their house, or something that might be that end goal.

And even if the home is not the goal, that is okay too. As you can see, something that is really important is the neutral zone. As I mentioned previously, it is helpful to not make patients feel as though they have to take a step backward. This is a spot to take a pause or a rest stop. In the car example, they can get their tires adjusted or realigned or more gas in their tank. This is a great analogy and something they can relate to.

There are also milestone markers that I will talk about in a second that highlight the individualized aspects of the medical experience as well as interdisciplinary goals. For example, with my oncology patients, there are a few things that we need to do that are standard goals for our patients. However, many times those trajectories are all over the place. If we do not have specific milestone stickers, we can put up these post-it notes that have goals from each discipline, and often we will color-code them. For example, Occupational Therapy goals are pink, while Child Life goals are in blue. We tag them along the outer edge of the board. We really want to make sure that the board stays family and patient-focused. It is easy for clinicians as part of this process to put all their goals up there, but then it looks messy. We do not want it to be overwhelming for the patient or their family.

Video

This shows you how the boards are utilized. They are all 12 by 18-inch firm foam boards that are easy to maintain. It can be incorporated in the hospital setting because it can be wiped down to meet infection control standards. The client can personalize it, and often team members sign the back. There is an area for pictures to really personalize it to make it feel like it is their own. This is also a good opportunity to build connections with patients.

We do use these re-positionable stickers that match the theme of the board to help the patient track their whole experience. And then, in the end, we suggest that patients take their board home as something that they can use to recognize all of the progress they have made. In my experience, these have helped clients understand the progress they are making and what lies ahead of them. We can also use these to address any questions they might have without all of the medical jargon. During the rounding process, we can use this to translate the information down to their level. "Where we are on the map today? What are our goals?"

Promoting Strategies: Medical Mapping

- Utilizing Get Well Maps and Milestone Markers as a Patient and Family Medical Education Tool:

- A member of the child’s medical team should apply 1 sticker (or 2-3 maximum at a time) to the child’s Get Well Map to provide families with a visual tool that prepares them for the next upcoming milestone that needs to be addressed in the discharge planning process/pathway

- Stickers should be applied in the sequence that best aligns with the team’s Interdisciplinary Plan of Care

- Don’t forget that a milestone can be depicted in the neutral zone, as it might be the milestone that must be achieved to end a set-back or pause in medical progress

- Adjustable & removable as the child may request that these milestones are removed after achievement.

- Members of the child’s medical team can autograph the back of the child’s Get Well Map upon discharge.

- The Get Well Map becomes an individualized keepsake that depicts a child and family’s bravery and perseverance!

Milestone markers are a new initiative that we have been collaborating on as a visual medical education tool to help children and families map out the individualized components and goals of their care. Currently, we have cardiac milestone stickers, and we have been working on pediatric oncology milestones, as well as milesone stickers for a Retinoblastoma Family Advisory Group in Canada. We have been working with this advisory group on milestone markers for pediatric eye cancers. These stickers are small, and we target different areas. I am going to show you an example in the next couple of slides. We recommend applying one sticker or two to three maximum at a time to the child's Get Well Map. This provides patients and families with a visual prompt of what is going to help prepare them for the next upcoming milestone. They are designed to be applied in the sequence that best aligns with the team's interdisciplinary plan of care. They can also be depicted in the neutral zone as it might be a milestone that must be achieved in order to end a setback. They are adjustable and removable as many of the kids requested that the milestones be removed after achievement. Many of these milestones are related to medical education, and although important in the moment of hospitalization, many kids are really excited that this becomes a keepsake of their bravery and perseverance.

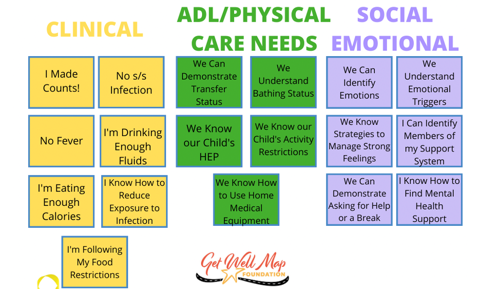

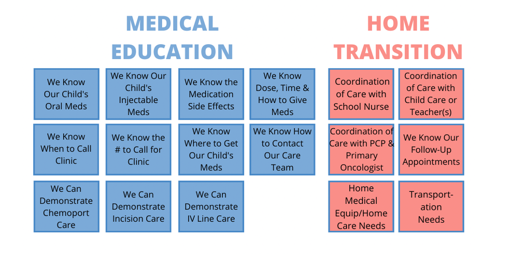

These are some examples that Christina and I have developed for the pediatric oncology medical markers in Figures 13 and 14.

Figures 13 and 14. Pediatric oncology medical education and milestone markers.

We color code a lot of our supplies to identify the difference between clinical goals, ADLs, physical care needs, and social-emotional items. There are just so many things that can get lost and jumbled in the shuffle that might not be clear to a younger child. We pull one or two from each category and highlight that so it is easy for everyone to keep track. There is also medical education and home transition.

Case Study

- Pediatric Oncology Case Study-Emily

- 11-year-old female, mild CP

- Bone Marrow Transplant recipient

- 2 hours from home

- Cultural Considerations

- Hospitalization lasting approximately 2 months

- Discharge planning process initiated ~2 weeks prior

- Discharge delayed by fevers-Clinical vs. Non-Clinical Goals

In my work on the bone marrow transplant unit, I met Emily. She was an 11-year-old girl who had mild cerebral palsy as well as a medical condition that required her to have a bone marrow transplant. While Emily herself was bilingual, her parents only spoke Spanish. Both mom and dad were at the bedside with her. They lived about two hours away, and she was hospitalized for two months, which is pretty typical for our transplant patients. Culturally speaking, her parents were very protective and wanted to do everything for her even before hospitalization. They wanted to feed her, dress her, and make sure they had control. As you can imagine, this was exacerbated even more in the hospital setting because she was sick. At times, this caused Emily to become really frustrated. They were stuck in this room, and she was at an age where she wanted a little bit more independence. Her parents were around her 24/7 around her trying to do the best that they could but ultimately causing frustration.

Another piece of the puzzle here was that Emily experienced a lot of body changes. She lost all of her hair and had prolonged bloodshot eyes for several weeks. These changes caused her a lot of distress. When we met, we had planned that she was going to FaceTime her cousins who were not able to visit as she was very close to them. However, when she started to have these body changes, she decided not to do that as she was really embarrassed. She had a lot of these non-medical stressors but then also the medical stressors. There is a lot happening with a bone marrow transplant, and she got really sick for a while.

As she continued to improve medically, she needed clear specific goals to help motivate her to reach the finish line of going home. For bone marrow transplants, we have some things in place as it is pretty cut and dry. For example, we started talking about discharge about two weeks before she was ready to go home. We decided at this point to introduce a medical map to help her process her responsibilities to get to the discharge point. Things on her list were maintaining her nutrition and her physical therapy goals. Emily was phenomenal.

When I introduced the map, she became engaged in the process right from the start. She immediately drew a picture of her bedroom as her end goal. She wanted to sleep in her own bed. We took some pictures of her and put that up on her board. She also put some glitter on her name to make the board her own. We also started using the board during daily rounds so that Emily could stay on track. The team would talk on rounds holding the board and put the sticky notes up on the board for that day's goals. Emily would then look at her board and move her sticker from the previous day. When she got her new goals, we put those up on the board, and it was really exciting to process that with her in the moment.

She did develop fevers so we talked a lot about how this was not her fault, and we took that pause in the pit stop area. This really caused her a lot of distress at first because she knew that that was going to push out her discharge date, but we helped kind of talk through that. And again, we did not move her sticker backward. She just stayed in that pit stop until she was fever free for two days, and then we picked up where we left off. It really was a balance for her to know that she could still participate in some of her goals even though she was not moving forward. We talked a lot about this. If she was feeling well enough, she still needed to eat, take her walks, and get dressed for the day. It was exciting when it was time for her to go home. She took her map with her, and it really felt like she used it as a trophy to represent all of her progress. She also got the signatures of all of the staff on the team. She even added some pictures on it of her care providers.

Outcomes

- Creating a Process for Promoting High-Quality Individualized Care in a Family-Centered Healthcare Environment

- Admission à Discharge

- Improved Consistency of Developmentally-Appropriate Medical Communication & Medical Education among the Interdisciplinary Team

- Preparing Families for Transitions

- To different units within the hospital, Ronald McDonald House, and Home

- Empowering Families throughout the Discharge Planning Process

- Use of visual supports, small chunks of medical education for children & families to process, and multi-sensory learning strategies

We are going to quickly wrap up with some of our outcomes. We know that creating this process for promoting high-quality individualized care in a family-centered healthcare environment promotes positive discharge planning and can shorten the length of stay, prevent re-admissions to the hospital, and improve consistency of developmentally appropriate medical communication. This keeps everybody on the same page. It can also be very helpful to prepare families for transitions to the different units within the hospital, to a Ronald McDonald House, and even their home. Again, it does not have to be that standard end goal of home. It really can help empower families throughout the entire discharge planning process which we know starts upon admission. Lastly, the maps can spark creativity, interest, and engagement in the process.

- Child- and Family-Centered Care = Improved Satisfaction & Outcomes

- Positive Patient Experience

- Child & Family-Centered Care

- High Quality, Individualized Care

- Effective Medical Education

- Collaborative Discharge Planning

- Meaningful Partnerships with Engaged Families

- Facilitating Positive Outcomes

Child and family-centered care is really about improving the satisfaction and ultimately the outcomes of the patient and family experience. We know that this continues to promote high-quality individualized care and an effective means of medical education that is collaborative. It allows for engaged partnerships with families. It is an important tool for all clinicians.

Potential Barriers

- Disengaged Child &/or Family

- Working in Clinical Silos

- Inconsistent Staffing

- Organization Demands &/or Insurance Pressure

- Lack of Experience with Medically Complex Patients & Families

- Unestablished or Unrealistic Expectations

- Lack of Resources-Financial, Time, Support

- Difficulty Sustaining a Child- & Family-Centered Focus

- Language Barriers

I would be remiss to not talk about some potential barriers. This is not something that we do without pushback here and there. There are definitely times where there is a disengaged child or family that this is not right for t