Introduction

Good afternoon, everyone. It is wonderful to be here. Today, we are going to be talking about a neurodegenerative disease where I believe we, as occupational therapists, can play a very impactful role. As we go through the content, I think you will realize that this is a very diverse disease process, and there is a lot of content to cover. If you find that there is anything in here that I go over that you want more detail about, I do encourage you to do some self-directed learning and do your own research about it.

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS)

- ALS, or Lou Gehrig’s disease, is a fatal, progressive neurodegenerative disorder resulting in profound muscle weakness and wasting of nearly all voluntary muscles, including the muscles needed for respiration.

- Amyotrophic=muscle atrophy – Lower motor neuron

- Lateral Sclerosis=degeneration and eventual death of motor neurons in the motor cortex, brain stem, anterior horn cells and pyramidal tracts – Upper motor neuron

ALS is also known as Lou Gehrig's disease. It is fatal and progressive. As I mentioned, it is a neurodegenerative disorder. It results in profound muscle weakness and the wasting of nearly all voluntary muscles, including the muscles needed for respiration. The number one cause of death for these patients is respiratory failure because it affects the muscles of the diaphragm and the patient's ability to breathe. In the name, Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, there are two main signs of the disease: upper motor neuron and lower motor neuron. Amyotrophic refers to the lower motor neuron portion of the disease because that has to with muscle atrophy, and then lateral sclerosis has to do with the upper motor neuron portion of the disease. It speaks to the degeneration and eventual death of motor neurons in the motor cortex, brain stem, anterior horn cells, and the pyramidal tracts, which are all part of the central nervous system.

Patients with ALS face substantial occupational challenges. Many of the activities that bring meaning and purpose to the lives of these individuals, their friends, and family members are substantially altered. All occupations that are characteristic of adults are affected by ALS in some manner, including activities of daily living, instrumental activities of daily living, work, leisure, and socialization. A person with ALS may eventually lack the cognitive and physical abilities to adapt to occupational challenges and/or participate in occupation. The person may no longer be a match for the occupation, creating occupational dysfunction and loss of identity for persons with ALS. Also, there is a lack of evidence focusing on interventions whose outcomes are at the level of occupational participation for patients with ALS. In fact, a systematic review done by Erin Foster in 2014 revealed a gap in the OT literature for all neurodegenerative diseases.

Occurrence

- Occurs 1-2 per 100,000 persons worldwide (Redler & Dokholyan, 2012)

- More common in men until the age of 65

- Peaks between 40-70

- 5,600 diagnosed yearly in the US

- 5-10% of cases are familial (FALS)

- The median survival rate is 32 months from the onset of signs and 19 months from diagnosis (del Aguila, et al., 2003)

In terms of occurrences, it is a pretty rare disease. It occurs in 1 to 2 per 100,000 persons worldwide. It is more common in men until the age of 65, and it peaks between 40 and 70, although I have treated patients who were in their twenties when diagnosed with the disease. There are about 5,600 diagnosed yearly, and 5 to 10% of the cases are familial ALS meaning they are genetically-based. The SOD1 gene, which I will talk about in a few more slides, is the gene that is associated with the familial form of the disease. As I said, it is a pretty small percentage with only 5 to 10% of the cases.

The median survival rate is 32 months from the onset of signs and 19 months from diagnosis. Some negative prognostic indicators for patients with the disease include the following: being older in age at the time of the diagnosis, being female, being diagnosed in a short time after the onset of signs and symptoms, and having bulbar onset ALS. Bulbar onset ALS has to do with dysarthria and dysphagia due to the degeneration of the motor neurons in the face and the cranial nerves. It also has a higher link to respiratory symptoms from ALS. There is also a negative prognostic indicator with those lacking a marital partner. I think that is just because of not having social support or caregivers available. Treatment considerations for patients with ALS focus on multi-disciplinary care that addresses quality of life and symptom management.

Respiratory

- ALS causes weakness to the diaphragm muscle and other muscles needed for respiration.

- Respiratory failure is the most common cause of death (Pinto et al., 1995).

- Mechanical Ventilation vs. palliative and hospice care

ALS causes weakness to the diaphragm muscle, which I spoke about. Respiratory failure is the most common cause of death, and many patients as they progress through the disease process, eventually come to the decision to either go on mechanical ventilation or go to palliative and hospice care.

Signs of ALS

- Onset presents with one or a combination of signs

- Lower Motor Neuron (LMN) involvement

- Upper Motor Neuron (UMN) involvement

- Bulbar Involvement

- Cognitive Impairments

- Respiratory Involvement

Now, we are going to talk a little bit about the signs of ALS. The onset is typically one or a combination of either lower motor neuron onset, upper motor neuron onset, bulbar involvement, cognitive impairments, or respiratory involvement.

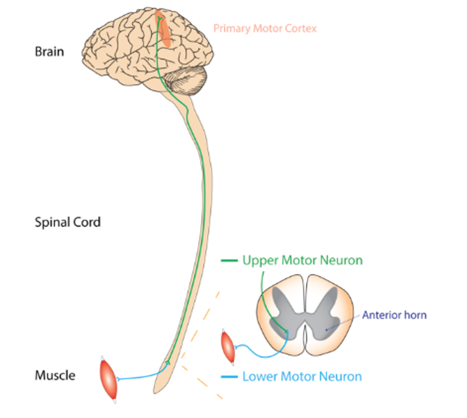

Figure 1. Brain and spinal cord.

As we talk about upper and lower motor neurons, I want to point out a few things on the brain and the spinal cord. There is the cerebral cortex, the midbrain, the spinal cord, and the upper motor neurons. And then, when we talk about lower motor neurons, these are the nerves that connect the spinal cord to the individual muscles.

Signs of ALS-Lower Motor Neuron

- Lower motor neuron involvement causes:

- Asymmetrical muscle weakness and atrophy (Benny & Shetty, 2012)

- Extensor muscles of the fingers and wrist

- Intrinsic muscles of the hand (Thenar Muscles)

- Dorsi-flexor weakness

- Asymmetrical muscle weakness and atrophy (Benny & Shetty, 2012)

- Functional Impairments from LMN signs

- Frequent tripping during ambulation

- Difficulty buttoning shirts

- Difficulty writing/typing

- Difficulty holding and turning a key

The lower motor neuron signs of ALS have to do with asymmetrical muscle weakness and atrophy. It usually affects the extensor muscles of the fingers and wrist first. It also affects the intrinsic muscles of the hands, and typically, you will see more weakness in the thenar muscles than you do in the hypothenar muscles. Dorsiflexion weakness is also a sign of lower motor neuron onset. This is the inability to dorsiflex your ankles. A functional impairment from a lower motor neuron sign is frequent tripping during ambulation. You might have a client who trips on uneven ground or on carpeting. They may also have difficulty buttoning shirts, difficulty writing and typing, and difficulty holding or turning a key. Some other lower motor neuron signs are fasciculations.

- Fasciculation

- Small, localized, and involuntary muscle contractions

- Normally occur in most humans due to spontaneous depolarization and repolarization, causing localized muscle twitching.

- Fasciculations associated with ALS are pathological in nature due to damage to the LMN (Mills, 2010)

- Cramping

- Hyporeflexia

Fasciculations are small, localized, and involuntary muscle contractions. All of us experience fasciculations from time to time. They are due to a spontaneous depolarization and repolarization which causes localized muscle twitching. The fasciculations associated with ALS are pathological in nature and are due to damage to the lower motor neuron. Typically, it is indicative of the disease advancing. Patients who already have weakened musculature may experience fasciculations in those muscles as the motor neurons in the muscle start to deteriorate. It is a sign that the disease is advancing. Other lower motor neuron signs are cramping and a lack of reflexes or hyporeflexia.

Signs of ALS-Upper Motor Neuron

- Spasticity

- Occurs due to lesions in the UMN of the primary motor cortex (PMC)

- PMC is responsible for voluntary and purposeful excitation and inhibition of LMN –resulting in coordinated muscle contractions and functional movement

- Degeneration of neurons in the PMC causes loss of control of LMN

- Causes difficulty with ambulation, ADL, and IADl (Ashworth, Satkunam, & Deforge, 2006).

Upper motor neuron signs usually involve spasticity. Spasticity is velocity-dependent resistance to a stretch. As you are doing passive range of motion to a muscle, you will feel resistance to that stretch, and this occurs due to lesions in the upper motor neurons of the primary motor cortex. This primary motor cortex is responsible for voluntary and purposeful excitation and inhibition of the lower motor neurons, which results in coordinated muscle contractions and functional movement under normal circumstances. Degeneration of the primary motor cortex causes loss of control over the lower motor neurons, and this causes a constant state of contraction, which is spasticity. Spasticity will functionally cause difficulty with ambulation, ADL, and IADLs.

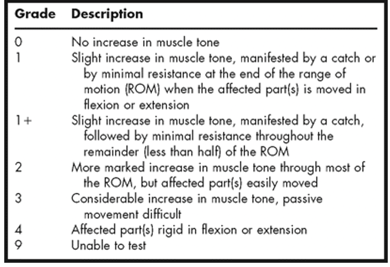

Modified Ashworth Scale.

Figure 2. Modified Ashworth Scale.

We use the Modified Ashworth scale as a way to measure the degree of spasticity, and it ranges from 0 to 4. Zero is no increase in muscle tone and 4 is all affected parts are rigid in flexion or extension, sort of feeling like a contracture. There are different grades: 1, 1-plus, and 2. You can look over this in a little bit more detail if you want. If for some reason you are unable to do a test on spasticity, you would score it as a 9 in that limb.

- Hyperreflexia

- Increases sensitivity to deep tendon reflexes, including Babinski’s sign (Chen et al, 2004)

- Involuntary extension of the first digit of the foot

- Increases sensitivity to deep tendon reflexes, including Babinski’s sign (Chen et al, 2004)

Other upper motor neuron signs are hyperreflexia, and this is an increase in sensitivity to deep tendon reflexes. A positive Babinski sign would be a sign of hyperreflexia and an upper motor neuron onset of ALS.

Signs of ALS-Cognitive

- Fronto-Temporal Dementia FTD

- A specific type of dementia

- Differs from Alzheimer’s Disease (AD)

- Often misdiagnosed as AD – despite clear differences

- Behavioral Changes

- Disregard for social norms

- Apathy

- Not associated with as much memory loss as AD

- Patients with AD can often maintain social relationships and do not have major behavioral changes, at least early in the disease

Other signs and symptoms may involve cognition. Until recently, cognition was not thought of as being a part of ALS. However, there is a specific type of dementia called frontotemporal dementia (FTD). Many patients who have ALS also end up having frontotemporal dementia. The two diseases are so interrelated, pathophysiologically, that some researchers believe that they are part of the same disease process. FTD is a specific type of dementia that differs from Alzheimer's disease. It often is misdiagnosed as Alzheimer's disease despite the clear differences.

Frontotemporal dementia occurs because the neurons in the frontal lobe start to degenerate. The frontal lobe helps with emotional control, awareness of behavior, recognizing social norms, and adjusting your behavior to different social situations. Patients with frontotemporal dementia have behavioral changes, a disregard for social norms, and apathy. It is not associated with memory loss as Alzheimer's disease is. Patients with Alzheimer's disease, for example, can still maintain social relationships usually well into the disease, but patients with frontotemporal dementia cannot. These patients have a lot of executive function impairments as well because of the degeneration of the frontal lobe. Patients with impaired executive function due to frontotemporal dementia have difficulty processing and interpreting visual and auditory stimuli, organizing information to form solutions to problems, executing logical solutions, and anticipating consequences.

Patients with FTD also have been found to have difficulty understanding verbal and written language, as well as having decreased speech fluency. There was a gentleman I once treated with ALS that, while driving with his nephew, got stopped at a red light. After the light turned green, he was unable to recognize the green signal and associate it with the action of continuing to drive. He said to his nephew, "I do not know what to do next." There was another example of a woman with ALS who was known for being very money conscious. She began spending all of her money on items from infomercials, such as QVC and the Home Shopping Network. These were all items that she would never have purchased in the past and had no current use for. She lost the capacity to reason, self-correct, and control her impulses. A third example is a man with ALS who was known for being very warm, friendly, and loving, especially towards his family. He had a complete personality change where he began to be very cold and distant from his friends and family, and he had little insight into his behavior. When asked about it, he could not understand why his friends and family were concerned. These are just some examples of what the behavior pattern for patients with frontotemporal dementia and ALS would be like.

Signs of ALS - Bulbar

- Bulbar signs are caused by the deterioration of cranial nerves

- Facial weakness

- Tongue weakness

- Difficulty swallowing

- Dysphagia

- Dysarthria

- Sialorrhea (excessive production of saliva)

Bulbar onset ALS is another. As I mentioned before, this is caused by the deterioration of the cranial nerves. It causes facial weakness, tongue weakness, difficulty swallowing, dysphagia, dysarthria, and excessive production of saliva. They have difficulty managing those secretions, otherwise known as sialorrhea.

Signs of ALS - Cognition

- Cognitive Profile of ALS (in the absence of FTD) has been described as impairments in (Beeldman, et al., 2016): Meta-analysis of the literature, controlling for FTD.

- Speech Fluency

- Language

- Social Cognition

- Executive Functions

- Verbal memory

Even in the absence of frontotemporal dementia, there is a cognitive component of ALS. A meta-analysis done in 2016 showed that even in the absence of frontotemporal dementia, the cognitive profile of ALS is an impairment in speech fluency, language, social cognition, executive functions, and verbal memory.

- Executive Functioning (Garcia-Madruga, Gomez-Veiga, & Vila, 2016).

- Anticipation

- Planning

- Execution

- Self-Monitoring

- Pseudobulbar symptoms

- Inappropriate laughter

- Inappropriate crying

- Emotional Incontinence

When we talk about executive functions, we are talking about anticipation, planning, execution, and self-monitoring.

Other signs and symptoms of cognitive onset ALS are pseudobulbar symptoms. This is inappropriate behavior, like laughing and crying, or what some refer to as emotional incontinence. You might find that just in introducing yourself to a patient, they might start laughing, start crying, and then go back to normal behavior all within a few minutes.

- Patients who test positive for executive function impairment at baseline have a faster rate of motor functional decline and death (Elamin et al., 2013).

Patients who test positive for executive function impairments at baseline have a faster rate of motor function decline and death. The cognitive onset of ALS and cognitive symptoms associated with ALS are associated with a quicker decline in functional status and usually have a lower life expectancy.

Signs and Symptoms- Respiratory

- Respiratory

- dyspnea with exertion or lying flat

- weak or ineffective cough

- increased use of auxiliary musculature

- daytime sleepiness

- decreased concentration

- headaches

Respiratory symptoms with ALS are dyspnea on exertion or difficulty breathing when lying flat, and a weak or ineffective cough. You will also see increased use of auxiliary musculature when attempting to breathe. And then, because of oxygen starvation and decreased oxygen saturation, patients with respiratory symptoms will have daytime sleepiness, decreased concentration, and headaches.

ALS Usually Does Not Affect

- Bowel and Bladder

- Internal organs

- Sexual function

- Sensation – Posterior horn of the spinal cord

- Eye musculature

ALS usually does not affect bowel and bladder function, internal organs, sexual function, or sexual arousal. Obviously, with the physical decline with ALS, engaging in sexual activity might be difficult from that standpoint, but it does not affect sexual arousal or anything like that. Sensation is usually not affected because sensation is related to the posterior horn of the spinal cord, which is usually not affected by ALS. Also, eye musculature and eye movements are typically not affected which is good for communication software devices. This is important as eye gaze software can be used in the late stages by these clients to communicate, use a computer, and operate items around the house like the lights.

Pathophysiology

ALS-TDP-43

- TDP-43 – Transactive Response DNA Binding Protein 43)

- The human cellular protein encoded by the TARDBP gene

- An important role in normal neuron cellular functioning

- Binds both DNA and RNA in neurons

- Normally present within the cell body of neurons

- Excessive accumulation of TDP-43 has been found in the intracellular portion of motor neuron tracts in patients with ALS, and in the intracellular portion of neurons comprising the frontotemporal lobe in patients with Fronto-Temporal Dementia (Mackenzie et al, 2010).

This stands for Transactive Response DNA Binding Protein 43. It is a protein that is normally present in the cellular body of neurons. It plays an important role in neuron cellular functioning because it binds DNA and RNA in neurons, and as I said, it is normally present within the cell body.

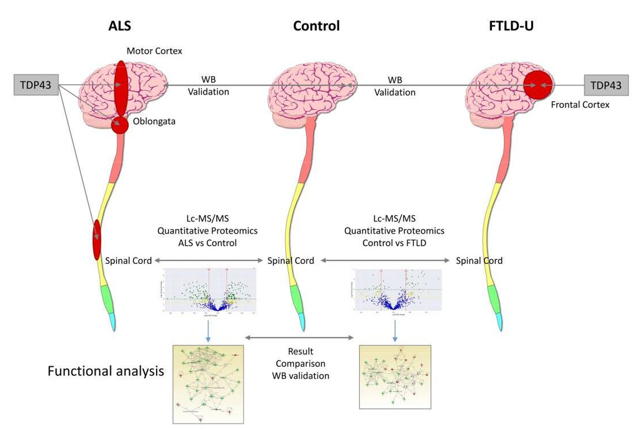

Figure 3. Overview of ALS and TDP-43. https://res.mdpi.com/ijms/ijms-20-00004/article_deploy/html/images/ijms-20-00004-ag.png; (Iridoy et al., 2019)

With ALS NFTD, there is an excessive accumulation of TDP-43 found in the intracellular portion of motor neuron tracts in patients with ALS and in the intracellular portion of neurons comprising the frontotemporal lobe in patients with frontotemporal dementia. This graph sort of summarizes that a little bit better. The patient on the left is a patient with ALS. The cerebral cortex and the primary motor cortex are highlighted in red and represent the TDP-43 excessive accumulation in the intracellular portion, and you also see it in the spinal cord. The control subject has TDP-43 present, but it is all contained within the neurons, and you do not see any in the motor cortex or the spinal cord. And then, in the subject with frontotemporal dementia (FTLD), you see the TDP-43 in the frontal lobe. If you had a patient with both ALS and frontotemporal dementia, you would see the TDP-43 in the motor cortex, the spinal cord, and the frontal lobes.

FTD Link

- Molecular and genetic link between ALS and FTD have led some researchers to believe that the two diseases are a continuum of the same disease (Zago, 2011)

There is a pathophysiological link between ALS and FTD. The molecular and genetic link between these two diseases has led some researchers to believe that these are actually the same disease process, and they should be considered the same disease.

C9ORF72

- C9ORF72: Gene located on chromosome 9

- Associated with protein binding for axonal and dendrite growth

- Found in the cytoplasm and presynaptic terminals of neurons

- Mutations to C9ORF72 have been linked to a diagnosis of ALS, FTD, and both ALS and FTD (Byrne et al, 2012; Ratti et al, 2012).

- Lower age of onset for ALS

- Impaired cognition

- Impaired behavior

- Abnormal changes in the grey matter of the frontal cortex

- Reduced time of survival

Another cause of ALS is C9ORF72, a gene located on chromosome 9. This gene creates this protein for axonal and dendrite growth, and it is normally found in the cytoplasm in the presynaptic terminals of neurons. In the mutations to this gene, there is a lack of this binding protein, which has been linked to ALS. Patients who have a mutation have a lower age of onset for ALS, impaired cognition, impaired behavior, abnormal changes in the gray matter in their frontal cortex, and reduced time of survival.

SOD1 Gene

- SOD1 Gene: Superoxide Dismutase 1

- Encodes the enzyme SOD1

- Familial Type of ALS – 5-10% of cases

- Present on chromosome 21

- The enzyme is an antioxidant that regulates superoxide, a byproduct of oxygen metabolism, that if left unregulated, causes cell damage

- Mutations to the SOD1 gene have been linked with ALS

The familial form of ALS is on the SOD1 gene. Again, this only accounts for 5 to 10% of cases. The gene encodes the enzyme, SOD1, which is superoxide dismutase 1. It is usually present on chromosome 21, and the enzyme is an antioxidant that regulates superoxide, a byproduct of oxygen metabolism. If this is left unregulated it will cause cell damage. The mutations to the SOD1 gene have been linked with ALS.

Sporadic Form

- Multiple theories on the cause of the sporadic form ALS:

- Excess Glutamate – a neurotransmitter

- Neuro-inflammatory process

- Environmental factors

- Head trauma

- Excessive physical activity

- Genetic predisposition

Some other theories on the cause of the sporadic form of ALS is an excessive amount of glutamate, which is a normal neurotransmitter associated with memory and learning. There can also be some sort of neuro-inflammatory process, which I think is more stress-induced. In my experience, many veterans and police officers have developed ALS. This may be due to the stress of the job and the neuro-inflammatory process. Other causes could be environmental or head trauma. We all know about football players and soccer players being prone to having ALS. Also, those that perform an excessive amount of physical activity like marathon runners and other athletes that are engaged in a lot of physical activity are a little more prone to having the disease. And of course, we talked about the genetic predisposition.

Diagnosis of ALS

- What does a typical person with ALS look like?

This is a trick question because there really is no standard presentation.

- El Escorial Criteria – widely accepted as a method for diagnosing ALS (Brooks, Miller, Swash, & Munsat, 2000)

- El Escorial Criteria focuses on UMN and LMN signs and does not consider cognition.

They use the El Escorial Criteria to diagnose ALS and this graph goes through that.

Figure 4. EI Escorial Criteria.

It moves from suspected ALS to definitive ALS. It all really depends on the amount of lower motor neuron signs and upper motor neuron signs, and the progression of the disease. The one thing to note is that the upper motor neuron and lower motor neuron signs cannot be explained in any other way. There cannot be any electrophysiological or neuro-imaging evidence for any other disease process. This is how they diagnose the disease.

Treatment-Medication

- Riluzole (Rilutek)

- Reduces Glutamate

- Primary neurotransmitter for learning and memory (which can lead to neuron damage in excess amounts)

- Approved by the FDA for ALS treatment

- Increases survival by 2-3 months

- Reduces Glutamate

- Symptom management

- NPT520 (Neuropore Therapies)

- Given orphan drug designation by FDA

- Penetrates blood-brain barrier

- Decreases neurotoxic misfolded proteins (superoxide dismutase 1) in the animal models

The number one drug that patients are prescribed is Rilutek, and this has to do with glutamate. Remember we said that there is a theory that excessive glutamate is one of the causes. Riluzole, or Rilutek, reduces the amount of glutamate in the system. It is approved by the FDA for ALS treatment, but it really only increases survival by two to three months. I do not know if anything has changed, but at least back in 2012 and before that, it was not typically approved by insurance and was expensive. There were many patients I knew who decided not to take it because the benefits of survival for two to three months they just did not feel was worth it.

NPT520 is another drug that has been given orphan drug status by the FDA, meaning that it is not fully approved yet. This is a drug that penetrates the blood-brain barrier and has to do with the SOD1 gene. It decreases the neurotoxic misfolded proteins that come in the absence of superoxide dismutase 1, the antioxidant produced by the SOD1 gene. It takes care of those misfolded proteins that result because of excessive oxidation.

- Tiglutik (Riluzole Oral Suspension)

- Same as rilutek

- Liquid form vs. tablet to accommodate patients with dysphagia

- Administered with an oral dosing syringe

- Radicava (Edaravone)

- Removes free radicals

- Provides neuroprotection

- Provides neuroprotection in the absence of superoxide dismutase 1

There is Tiglutik which is really just the liquid form of Rilutek, or Riluzole. It is a liquid form that is administered with an oral dosing syringe for patients who cannot tolerate the tablet form.

Radicava removes free radicals and provides neuroprotection. It takes the place of the SOD1 gene by providing some antioxidant protection in the absence of superoxide dismutase 1.

You might notice that a lot of these drugs really focus on that SOD1 gene, and this is really only 5 to 10% of ALS cases. As this was the first gene discovered as one of the causes of ALS, there has been more research and pharmaceutical response to it. Hopefully, in the upcoming years, there will be more studies that look at the TDP-43 aspect of ALS.

Physical and Occupational Therapy Goals for Persons with ALS

- Optimize occupational participation and performance

- Activity/Exercise modification

- Stretching (maintain ROM, reduce pain, normalize tone)

- Prescription and utilization of appropriate assistive devices

- Patient and family education

- Strategies to reduce caregiver burden

What are the goals for PT and OT when treating patients with ALS? We need to look at activity/exercise modification, stretching, range of motion, reducing pain, normalizing tone, prescribing appropriate assistive devices, and providing patient and family education that focuses on reducing caregiver burden.

Exercise

- Purpose: Evaluate the effects of three different types of strictly monitored exercise programs versus a usual care program on retention of function in a cohort of ALS patients

- Individual, Single-Blind, Randomized Control Trial

- All participants had MMT of 3/5 or higher

- Intervention Groups: 6 months

- Active exercise performed with a PT, in a clinic plus a cyclogometer activity (20 minutes of upper and lower extremity cycle activity in a seated position).

- Active Exercise without Cyclogometer

- Passive Exercise protocol without active exercise

- Measurement:

- Score on the ALS Functional Rating Scale (ALS-FRS). ALS-FRS is a validated rating instrument to monitor the progression of disability in patients with ALS. The ALS-FRS evaluated bulbar, motor, and respiratory function.

- Forced Vital Capacity (FVC)

- Perception of quality of life on the McGill Quality of Life Questoinnaire (MGQoL)

- All participants were measured prior to treatment, then monthly, until 6 months, then again at 6 months post-treatment.

Lunetta, C., Lizio, A., Sansone, V. A., Cellotto, N. M., Maestri, E., Bettinelli, M., Gatti, V., Melazzini, GM. G., Meola, G., Corbo, M. (2016). Strictly monitored exercise programs reduce motor deterioration in ALS: preliminary results of randomized controlled trial: Journal of Neurology, 263, 52-60. doi:10.1007/s00415-015-7924-z

I wanted to talk a little bit about exercise. If one is going to have a disease that is going to reduce the strength of all voluntary muscles, should we be prescribing exercise? We live in a society where we think that you have to stay active, and it is a use-it-or-lose-it type of mentality. This is a little controversial in patients with ALS because they have a finite amount of energy and muscle strength during the day. If they overuse muscles or over-engage in activity, they are going to be fatigued. This might mean then that they cannot engage in other activities later in the day after engaging in an excessive amount of activity earlier in the day.

However, it does have its place. Exercise is an activity that for some people is an important part of their day. For example, I like to run and lift weights. Many patients who have ALS do not want to lose that. So, it does have a role. One study showed that there are some benefits to at least staying active. As occupational therapists, we are not focusing on exercise nor am I suggesting that you do that. You need to think of these considerations when you are thinking about engagement in purposeful and meaningful activities. Exercises can be easily replaced by meaningful and purposeful activities, which may increase the client's quality of life.

This was a randomized control study with participants who had a manual muscle test of 3 out of 5 or higher, so these were not highly advanced ALS subjects. The intervention groups were in this program for six months, and they were split up into three groups. They either got active exercise performed with a physical therapist in a clinic plus cyclogometer activity, which was 20 minutes of upper and lower extremity exercise activity in a seated position, active exercise without the cyclogometer, or a group that just got a passive range of motion protocol. They used the ALS Functional Rating Scale to rate bulbar signs, upper limb function, lower limb function, and respiratory function. It consists of 12 questions focused on various functional activities including speech, salivation, handwriting, dyspnea, walking, or dressing. I do want to point out that the ALS Functional Rating Scale does not exclusively look at executive function or behavior. It also looked at their score on that and their forced vital capacity, or how much air the subject was able to breathe into their lungs and then expel out of their lungs. Finally, it looked at their perception of their quality of life using the McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire.

- Primary Findings

- Exercise plus Cyclogometer group

- Significantly higher ALS-FRS at the end of the 6-month treatment program and at the 6 months follow up, when compared to the “usual care” group.

- All participants who underwent the active exercise program had higher ALS-FRS at the end of the e6 month treatment program and at the 6 months follow up, when compared to the patients in the “usual care group”

- No significant differences in QOL were found

- No significant rates of survival were found

- Exercise plus Cyclogometer group

All participants were measured prior to treatment and then monthly until the end of the exercise or non-exercise groups, and then again six months after treatment. They found that the patients who had the active exercise, especially the group that had the cyclogometer components, performed better on the ALS Functional Rating Scale throughout. They even were better at the six-month follow-up. However, there was no significant difference in the quality of life or survival was found.

- Can be controversial in persons with ALS although some studies have shown benefits

- Is possibly detrimental in muscles that are exhibiting weakness

- If exercise is important to the patient, modify their program for safety and energy conservation

As I said, exercise can be controversial and is potentially detrimental in muscles that are exhibiting weakness. These patients did have weakness because they were 3 out of 5 on a manual muscle test. I have had many male patients who have had some shoulder flexion, shoulder abduction, and external rotation weakness, like a 3-plus to 4-minus out of 5 on a manual muscle test. Upon evaluation, I gave them my spiel about really trying to pick activities and exercises that are meaningful for them and to not overdo it. However, these gentlemen decided to continue going to the gym. In fact, one individual did a lot of exercise in between our sessions. He was basically lifting weights to the point of failure. Within a one to two-week time span, he went from a 3-plus to 4-minus out of 5 to a complete 0 out of 5 on a manual muscle test. This is not the first time I have seen this.

- Stop if cramps or fasciculations occur

- Avoid eccentric contractions

- Avoid high resistance and high repetitions

- Monitor fatigue level

- Do not give resistive exercise to already weakened musculature

You want to be careful when you do have a patient who wants to engage in exercise or even excessive activity. Encourage them to stop if cramps or fasciculations. They also want to avoid eccentric contractions. These have been shown in the literature to be a little bit more damaging to muscles than concentric contractions. They also want to avoid high resistance and high repetitions. You need to monitor their fatigue level and do not give resistance exercise to already weakened musculature as I spoke about in that example.

Stretch

- Hold 20-30 seconds

- Perform 3-5 repetitions daily

- Involve Caregivers

- We cannot increase muscle strength, but we can maintain muscle length with stretching

- Spasticity Management

The best thing they could do is stretch. You want to incorporate a lot of stretching to normalize tone and maintain range of motion. These are just some guidelines for doing stretches noted above. It is important to involve the caregivers because that stretching in itself is an activity, and as the disease progresses, the patient might not be able to effectively stretch. While we cannot increase the muscle strength, we can maintain the muscle length with stretching. It also helps with spasticity management.

Now, we are going to transition to talking about some OT theories to help guide us when we are treating patients with ALS.

Ecological Model of Human Performance

The first model is the Ecological Model of Human Performance. This is one of my favorite models or theories in occupational therapy because I think it really captures what we do. I also think it provides an avenue for us to describe what we do to other professionals. I do encourage you to read more about this because using the language associated with the EHP might help you communicate with physical therapists, nurses, physicians, and social workers about what occupational therapy is and our role. This is a patient-centered approach that considers the person's personal interests, values, experiences, and how they relate to a person's temporal, physical, social, and cultural context in regards to performance.

This is the study of the relationship between organisms and their environment, which provides an excellent context to examine the performance range for persons with ALS as they cope with changing and diminishing physical and cognitive skills while still having a continued relationship with their environment.

Key Constructs of EHP

- Person Factors include sensorimotor skills, cognitive skills, psychological abilities, personal interests, values, and experiences.

- A task is an objective set of behaviors needed to engage in performance to reach a goal (Dunn, Brown, & Youngstrom, 2003).

- Context includes temporal factors (age, lifecycle, health status, expectations), physical factors (objects and elements that surround us), social factors (relationships and norms), and cultural/environmental factors (beliefs and values).

Performance refers to the person’s engagement in tasks within a context.

We all have "person" factors. These are the abilities that we possess that reside within us. These are our sensory-motor skills, cognitive skills, psychological abilities, personal interests, values, and experiences. We are surrounded by a context. These are the things that we do not necessarily have full control over.

The contexts are sometimes temporal factors, which are time-bound, like age. This also includes the life cycle, health status, and expectations. There are physical factors that surround us. These are the objects and elements that surround us. Social factors are relationships and norms. Your relationships and norms change depending on who you are socializing with. For example, you might have a different relationship with one person that is more formal than one that is more cordial. Thus, you can have a completely different relationship with different sets of people. Also, the cultural/environmental factors that surround us are the beliefs and values of the society that we live in, not only in our immediate environment. For example, there might be different cultural and environmental factors for someone who lives in New York City as compared to someone who lives in North Dakota. Also, there may be different cultural and environmental factors from someone who lives in the United States versus someone who lives in Iran. The context surrounds us no matter where we go, and it could change depending on where we go. It is how we interact with our context and how we use our person factors to interact with those contextual factors to form a transaction in order to complete tasks. A task is an objective set of behaviors needed to engage in performance to reach a goal, and the performance refers to the person's engagement in tasks within the context.

- Core Assumptions of EHP

- It is impossible to examine a person outside of the context in which they live their lives (Dunn, Brown, & McGuigan, 1994).

- Performance occurs as the person engages in a transaction with his or her context to engage in tasks. Combinations of specific tasks make up roles and occupations.

- Contexts can enable and promote as well as obstruct and inhibit an individual’s performance and performance range (Dunn et al., 1994).

- Performance Range is determined between the person and the context. The more effective the transaction between the person factors and contextual factors, the more extensive the performance range for the completion of tasks (Dunn et al., 2003).

- Independence occurs when a person’s wants and needs are fulfilled. The EHP model views the use of assistive devices or support of others as resources or tools to achieve independence (Dunn et al, 2003).

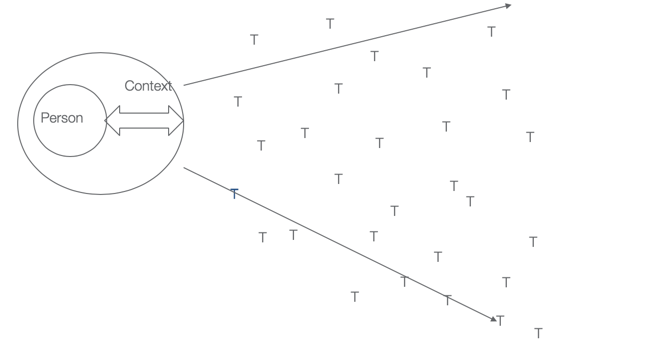

Here are some core assumptions of the EHP. As I alluded to, it is impossible to examine a person outside of the context in which they live their lives. Performance is when the person engages in a transaction with his or her context to engage in tasks. Tasks can be grouped together to make up roles and occupations. Context can enable and promote, as well as obstruct and inhibit, an individual's performance and performance range. For example, a person with ALS under normal circumstances may have interacted with their context very well. They were independent in their two-story house and could go up and down the stairs. But now, with a decrease in sensory-motor function, that context now no longer supports them in independence. It is now hindering and inhibiting performance. The performance range is determined between the person and the context. The more effective the transaction is, the greater the performance range. Independence occurs when a person's wants and needs are fulfilled. Any assistive device or support that is provided to the patient, the EHP model views this just as a tool to achieve independence. So, there are no concerns with using assistive devices or activity modification with the EHP (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Ecological Model of Human Performance.

And this model right here, you'll see in that center circle, you have the person, containing the person factors, surrounded by the context, and that arrow is the transaction with the context, and you could see in this case, because that person is transacting so well with the context that they're able to complete a large number of tasks, which if grouped together make up occupations. If that transaction did not work very well, then the performance range would be much more narrow.

Neuro-Functional Approach (NFA)

- Theoretical framework originally designed for clients with traumatic brain injuries (TBI), who have severe cognitive, behavioral, and executive functioning deficits.

- NFA is a good fit for the ALS population, as they too can have severe motor, cognitive, behavioral, and executive functioning deficits.

The Neurofunctional Approach was developed in the late 1980s and early 1990s by Gordon Muir Giles and Jo Clark-Wilson as a method of increasing occupational performance for patients with traumatic brain injury. It is best used for patients with ALS as a framework for assessment and intervention to target occupational performance and not cognitive processes.

As occupational therapists, we often defer to neuropsychological approaches, and I have done this myself. For some reason, it is very prevalent for us to use cognitive rehabilitation which focuses on retraining cognitive processes, such as short-term memory, attention, orientation, and basic problem-solving. The NFA differs fundamentally from the cognitive rehabilitation approach by directly targeting occupational performance in real-world activities and not attempting to retrain these cognitive processes. Most literature shows that you cannot train short-term memory as if it is some sort of muscle that can be improved that will then be generalized to all functional components.

- Theoretical Principles of the NFA (Giles, 2018)

- Cognition and function are related, but the constructs of cognition or function are not reducible to the other.

- One cannot assess functional performance abstracted from the context.

- Skilled performance develops through attentive repetition of activities (neural restructuring).

- The NFA was designed primarily for patients who are unlikely to spontaneously develop independence

And, you cannot separate out individual cognitive processes, because they are all interrelated and directly relate to function. The NFA also differs from other neuropsychological approaches that use metacognitive strategies. Metacognitive strategies are your awareness of your behavior and developing strategies to become more aware of your behavior and then changing your behavior in the moment. The reason why the NFA is different is that evidence suggests that these techniques are not effective for persons with such a severe lack of insight and behavioral impairment. For example, the Cognitive Orientation to daily Occupational Performance or CO-OP is a theory that uses metacognitive strategies based on awareness and insight. It uses the goal-plan-do-check strategy.

- Assessment of patients using structured and unstructured observations in the natural environment.

- Interventions are targeted at the client's ability level, not the impairment level.

- NFA recognizes that independence may not be restored in patients with ALS.

- NFA approach with ALS patients involves ongoing activity and task modification and the use of adaptive techniques and equipment.

The NFA is completely different than that as it is a more prescriptive approach that directly addresses the functional impairment at the level of occupation. It uses a precise method of performing a task where automaticity is achieved. Automaticity is a state where behavior is mastered to the point where the cognitive demand and the cognitive energy spent on performing that activity is completely removed because it becomes an automatic behavior. A good example would be with driving. If you remember when you were learning to drive, you had to attend to every decision you were making on the road. But now, under normal circumstances, unless it is an emergent situation, you do not even have to attend to driving. You can keep the car on the road, turn left, turn right, apply the brake, and you are not even thinking about it.

Overlearning – deliberate over-practicing of a task past a set criterion (Driskell, Willis, & Copper, 1992)

- Errorless learning – Tasks are taught in a manner designed to eliminate the number of errors made during the learning phase (Masters, MacMahon, & Pall, 2004)

- Chaining techniques – Learning whole functional tasks by utilizing a step by step process to teach the sequential steps of a task until completion (Walls, Aane, & Ellis, 1981).

These are some approaches that you would use in the NFA approach: overlearning, errorless learning, and chaining techniques. Overlearning would be the deliberate over-practicing of a task past a set criterion. Errorless learning is where a task is taught in a manner designed to eliminate the number of errors made during the learning phase. And then, chaining learning would be learning whole, functional tasks by utilizing a step-by-step process to teach sequential steps of a task until completion. Chaining can be forward, backward, or whole task training. When working with ALS patients on performing ADLs, for example, you may have them stand versus sit or use an assistive device. This is the type of approach you would use with patients who have ALS. You would alter the method that they were using before to make them more efficient and effective at performing this task.

Summary of Theory

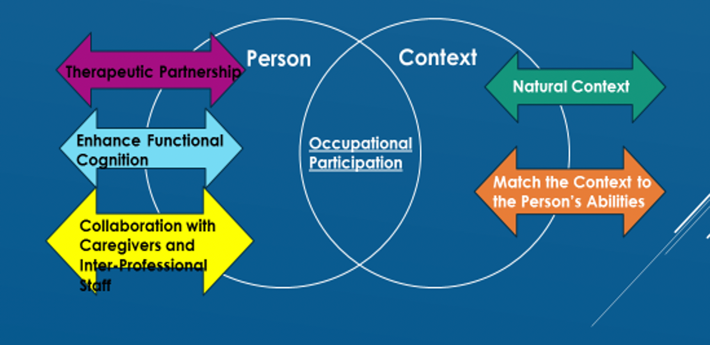

This is a summary of theory in Figure 6.

Figure 6. The Ecological Approach to Optimizing Occupational Participation for persons with Neuromuscular Disease or the EOP-NMD.

This is something I developed in my doctorate program. It is called the Ecological Approach to Optimizing Occupational Participation for persons with Neuromuscular Disease or the EOP-NMD. You will not find this in the literature, It is something I developed for my doctorate, and it takes components of the EHP and the NFA, but it also adds in my own experience of working with patients who have ALS. This is how I view working with patients who have ALS. Instead of having the person surrounded by the context, I envision having the person and the context as two separate circles that overlap, and the degree of overlap of the two circles, in the middle, is the occupational participation. We, as occupational therapists, in some manner, may want to push the two circles together to increase the degree of participation for patients. Or in some cases, we might want to pull them apart. The reason you might want to pull them apart is that the activity is just not that meaningful for the patient or maybe on certain days, there are some activities that are more important than others. For example, if you have a patient who has a family outing that they really want to attend, like a grandchild's birthday party, you do not want to use up all of their energy at the beginning of the day performing ADLs. You would suggest that they have more assistance earlier on in the day. Thus, you would pull the two circles apart and limit the amount of participation for ADLs so that they could attend the birthday party. Perhaps on other days, there are some other activities that are more important. They may want to be independent with their morning routine so in this case, you would push the two circles together. You would do this through a therapeutic partnership. This relationship with the patient should be based on trust and understanding and using motivational interviewing techniques. This calls for a relationship based on acceptance, empathetic understanding, relationship listening skills, and care is taken not to convey judgment or confront the patient in any manner. When working with these patients, we should always maintain a therapeutic partnership. You want to enhance cognition to reestablish or maintain habits or routines through practice. That is functional cognition and using the NFA and some elements of the Ecological Model of Human Performance. You want to collaborate with caregivers and interprofessional staff, reduce caregiver burden whenever possible, have extra support for patients, and advocate for patients to other interprofessional staff. Lastly, you want to work with the patient in the natural context. The EOP-NMD is not designed to work with patients in a clinic or a simulated environment. This has to be performed within the natural context. And then, much like the Ecological Model of Human Performance, you would better match the context to the person's abilities. Those are the five essential elements of the EOP-NMD to bring together and enhance occupational participation, or in some cases, as I mentioned, decrease occupational participation.

ALS Interventions

We are going to spend the remainder of this course going through just some common interventions for patients with ALS.

Mobility

- Cane

- Carbon Fiber AFO

- Rolling walker

- Companion wheelchair

- Power wheelchair

- Tilt in space

- Types of controls

- Positioning recommendations

The first one we will look at is functional mobility. I am just going to be giving some general interventions. A cane, obviously, is good for someone who lacks balance and has lower extremity weakness. I would recommend using a single point cane versus a quad cane just because it is easier to lift and does not add as much weight. We talked about lower motor neuron onset of the disease and a lack of dorsiflexion, thus an AFO is sometimes required. I would recommend a carbon fiber AFO because again it is lower in weight and less bulky than some of the other AFOs. Rolling walkers are recommended. However, the ones with handbrakes that can also be used to sit on called rollators are not always safe. If you are prescribing a rollator, make sure that the patient has adequate hand strength, trunk strength, and also just the awareness and ability to be able to utilize the brakes and make sure that they are on before they sit down.

Wheelchairs are great. I would recommend a companion because it is a tool to allow you to go further into the community. You can easily take it with you in a car and can be removed from a trunk. Caregivers can push the patient in a companion wheelchair. Clients do not have to exclusively use the companion wheelchair, but it is just there when they need it. For example, you might have a patient that can walk a certain distance. However, if they go further than say 500 feet or walking for more than 10 minutes, they might need to sit down. A companion wheelchair would be great for those patients.

For power wheelchairs, make sure that you are recommending the right power wheelchair that will accommodate their needs over time. You do not want to use their insurance benefit on something like a scooter or a power wheelchair that does not have tilt in space or other positioning options that patients might need. As an OT, you would make recommendations for the type of controls on that chair, where they were located, and also teach the patient how to use the chair. Even in the absence of being able to use a power wheelchair in the community and just using it in their house for positioning, it is a great tool to use as it reduces caregiver burden and provides some level of control to the patient. Additionally, if they want to move locations and go to a different room in the house, they could do that on their own. If they want to change positions like raise their legs or decrease the amount of hip flexion that they are in, they could do that on their own with the right type of wheelchair. If used properly, a power wheelchair can increase their quality of life by decreasing pain, increasing comfort, and increasing independence in the home. And if they can use it outside in the community, it is even better. We usually recommend it earlier on in the disease process as it can take three to four months for them to get it.

- Proper and safe techniques for transfers

- Family training – Reducing Caregiver Burden

- Knowing when to limit or avoid ambulating

- Use of a Hoyer lift

Family training should be provided on the right techniques to reduce caregiver burden. We do not want caregivers to get hurt while transferring patients. Knowing when to limit or avoid ambulation is also important. Again, it is not an all-or-nothing scenario. You do not want them to ambulate for an extended period of time and become too fatigued or overexert themselves. A Hoyer lift is a great tool to have on hand. You do not have to exclusively use the Hoyer lift. It could be used when patients are particularly fatigued or on days when they are just not feeling well. They may be able to transfer independently or with the help of a caregiver on other days but having it on hand is helpful. A common myth about the Hoyer lift is that it is big, bulky, and difficult to use, I can assure you that with the right practice, it is easy to use it in even the tightest of environments. So, I do recommend exploring that with patients. With a lot of these tools, it is not always easy to get patients to accept them, and it might not be a one-time conversation. Remember to establish a therapeutic alliance and trust. It might take a few conversations to get patients to come around to accepting a lot of these devices as tools. Per the EHOP and the NFA, these are considered tools to enhance independence and as a method to better match the patient's abilities with the context.

Assistive Devices and Transfer Aids

- Walkers—the ones with seats are not always useful

- Canes—stick with single-point canes

- Transfer boards take too much energy in most cases

- Pivot disc

- Gait belt

Here is some more information on equipment prescription, I think we went over some of this. A pivot disc is a great tool for stand pivot transfers. You can use this for patients who can do sit-to-stand transfers and have some strength in their hips and trunk, but they need help to turn. The one thing I do want to point out is transfer boards. I do not always recommend them. It takes a lot of energy, and it can be very difficult to use them, especially for patients that have advanced weakness in their upper extremities, trunk, and lower extremities. I would probably go to either a more dependent stand pivot transfer, with a pivot disc, or go straight to a Hoyer lift in those cases.

Activity Adaptation

- Energy conservation

- Home modification

- Driving

- Acceptance of help or use of devices

- Positioning to increase efficiency

We talked about energy conservation. Any time they can sit versus standing, especially for things throughout the day, I would recommend that. The more time they spend in standing, the more fatigued they will be later in the day. You always want to incorporate energy conservation throughout the day. One example is driving. You have to consider all of the aspects of driving. It is not just about keeping the car on the road and having the ability to turn the key or shift gears, but you also have to think about decision-making. Think back to the patient who was stopped at the red light that had frontotemporal dementia. And then, wherever they are going, they are going to have to get out of the car and ambulate. A patient could reasonably drive a car and get from point A to point B, but are they safely going to be able to get from the parking lot to wherever it is that they need to go and navigate uneven ground and walk those distances. I often discuss alternate forms of transportation prior to it becoming an issue. It is difficult to have these types of conversations because driving represents so much independence for these patients. We have had patients who had the resources to modify their car, which is great, but again, you have to remember about the transportation and all those other factors that I just spoke about.

ADL Equipment

- Use only if time and/or energy efficient

- Reacher

- Button hook

- Universal cuff

- Sock donner—very limited population benefits from this

Reachers, button hooks, and universal cuffs are all great. Sock donners are not always useful because of the amount of fine motor skills and hand function that it takes to load the sock onto the sock donner and utilize it. I usually try first to do a leg-crossover technique or some alternate method before I go to a sock donner for these patients. Figure 7 is an example of a button hook with a built-up handle using a cylindrical grasp.

Figure 7. Button hook.

This is a great way to button shirt buttons. Another method is to keep the buttons buttoned and do a dressing technique where you dress your arms first and then pull the shirt up over your head. This is another way to get around shirts with buttons. Or, you can suggest that they avoid shirts with buttons. This often comes up with men who are still working that have to wear dress shirts to work. I