Introduction

This has been a great pain virtual conference. I have been able to check in on some of the other presentations. They have focused on chronic and persistent pain, and today, we will talk about how to apply a lot of those same concepts to acute pain.

Occupational Therapy Practice Framework

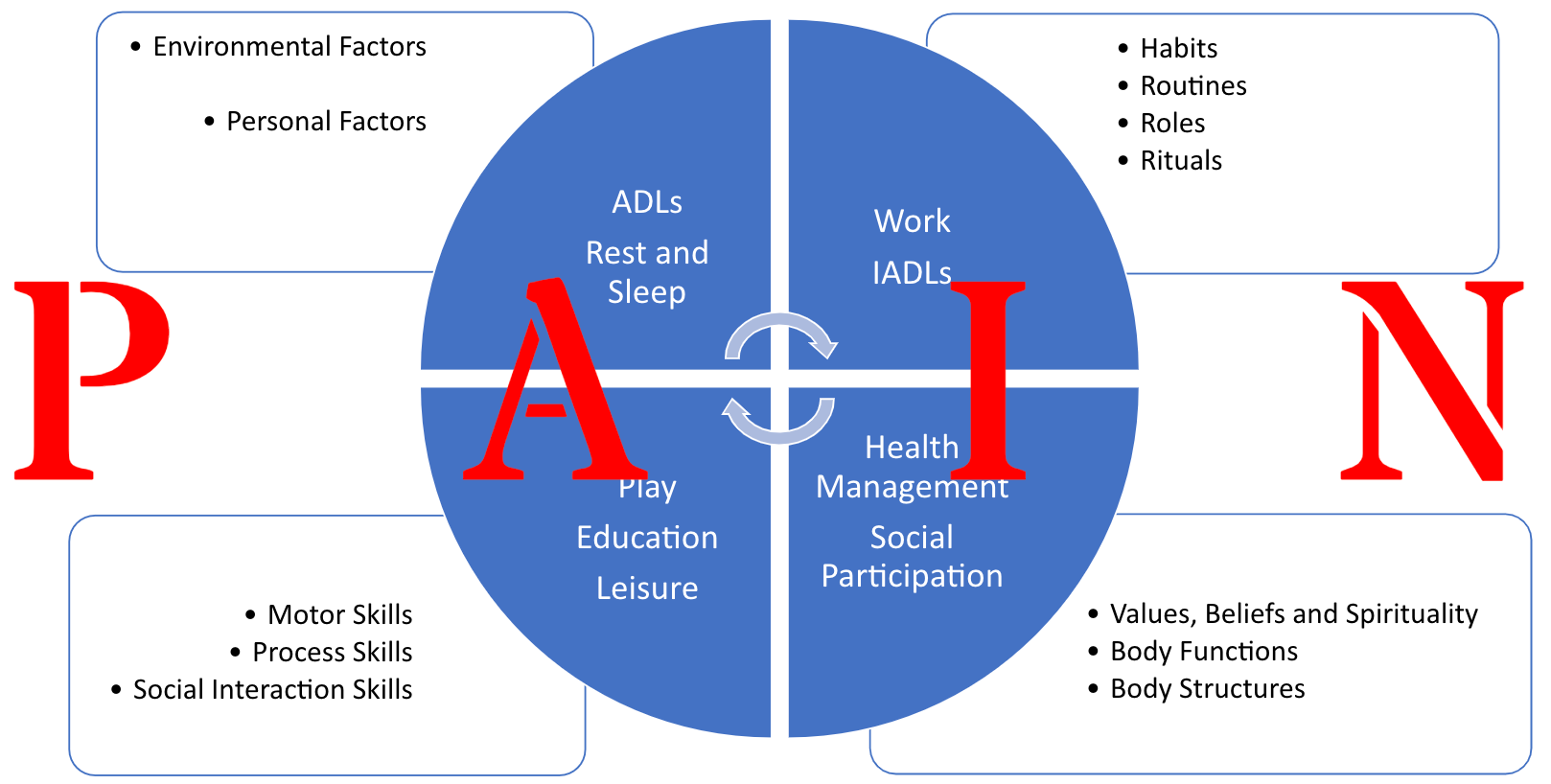

I have shared this exact slide in every single pain presentation I have given to an occupational therapy practitioner audience.

Figure 1. Factors involved in pain (American Occupational Therapy Association, 2020. Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process (4th ed.), American Journal of Occupational Therapy).

This is why we are here. This is the OT Practice Framework and the updated 4th edition. I have superimposed in big red letters the word pain over the top. These are areas we are going to address in any practice setting and population when pain is present. We should feel really empowered by that. Why is our scope so beneficial? An overview is shown in Figure 2.

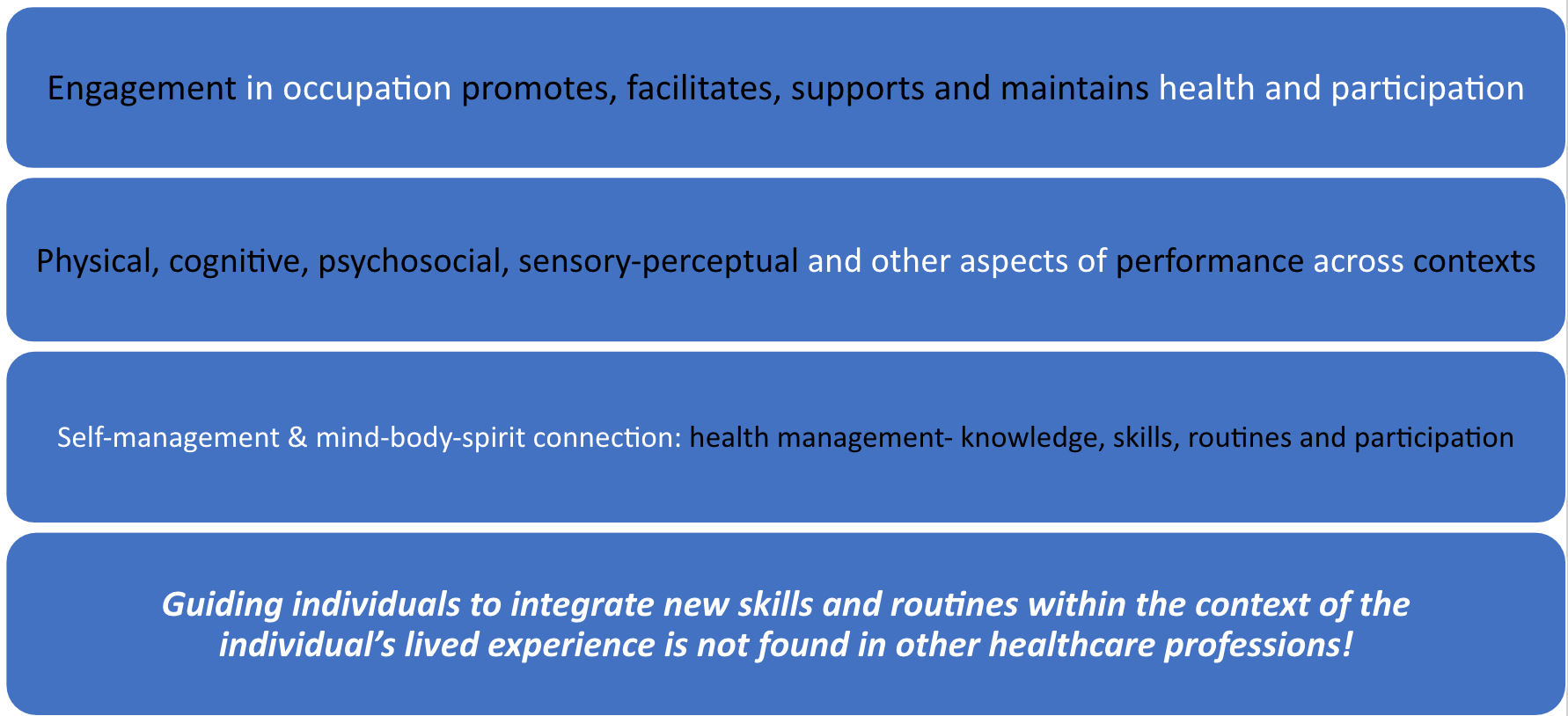

Figure 2. An overview of how we can assist individuals with pain (American Occupational Therapy Association, 2020. Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process (4th ed.), American Journal of Occupational Therapy).

Engagement in occupation promotes, facilitates, supports, and maintains health and participation. Why is that important? We will talk today about how engagement and occupation are beneficial for the treatment of acute pain. We also address physical, cognitive, psychosocial, sensory-perceptual, and other aspects of performance across contexts. These different areas, specifically self-management and the mind-body-spirit connection, affect the acute pain experience.

We have heard this week about the Biopsychosocial Model of Pain. This can also be applied to acute pain. We, as OT practitioners, can facilitate a mind-body-spirit connection to help with acute pain. This includes health management, knowledge, skills, routines, and participation. Unlike almost any other discipline, we can guide individuals to integrate new skills into routines within the context of their lived experience. In fact, you might argue at the end of this presentation that OT practitioners are best adept at addressing acute pain aspects because we have the ability to guide and address that lived experience.

Occupational Engagement and Pain: The Research

- Occupational engagement promotes health and well-being (Stav et al., 2012); however, pain influences ADLs, IADLs, health management, rest and sleep, education, work, play, leisure, and social participation.

- Pain influences (and is influenced directly by) changes in psychological state, occupational performance, relationships, and life satisfaction (Fisher et al., 2007)

- OT specific Models/Frames of Reference in Line with Biopsychosocial Model of Pain (Gentry et al., 2018): Person-Environment-Occupation-Performance (PEOP) Model; The Model of Human Occupation (MOHO).

Research supports that occupational engagement promotes health and wellbeing. And, we know that pain influences all those different occupational areas. Pain is influenced directly by changes in psychological state, occupational performance, relationships, and life satisfaction. This is just as true in chronic pain as it is in acute pain. If we integrate those principles into the acute pain experience, can we mitigate that in some way? Persistent pain is preventable, but can we also address that to decrease the risk of acute pain transitioning to persistent or chronic pain.

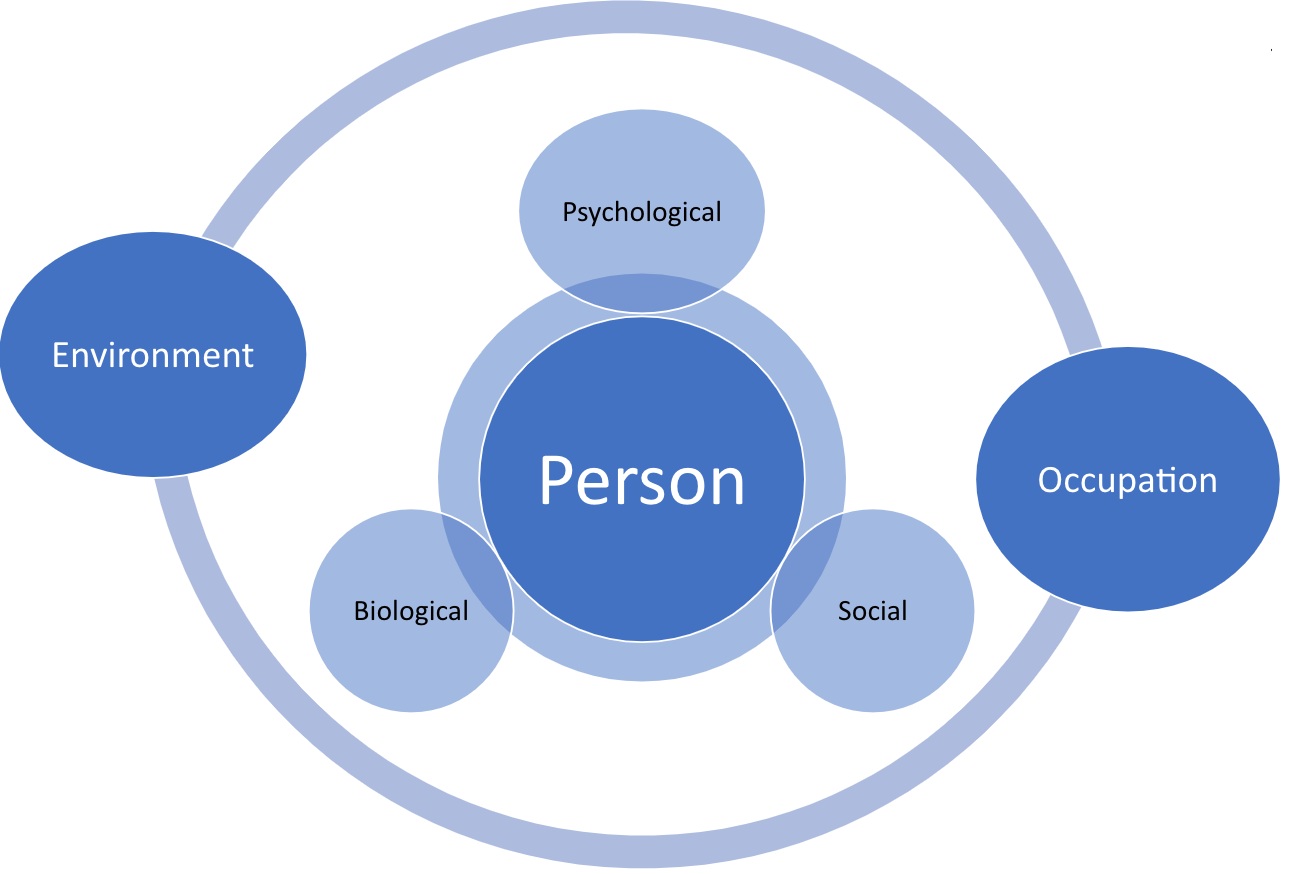

Our frames of reference are completely in line with the Biopsychosocial Model of Pain, particularly the Person-Environment-Occupation-Performance Model (PEOP) and the Model of Human Occupation. We want to take those models and apply those to our clients going through an acute pain experience.

- Participation in valued occupations as the focus and the intervention with activities used as needed, but only to support occupational participation

We need to support occupational participation. We will talk today about some different interventions, but please be mindful of the fact that any intervention should facilitate occupational engagement. Figure 3 shows a model where the person is the center of this participation.

Figure 3. A model where the person in the center of occupational engagement (Lagueux et al., 2018).

Why Aren't More OT Practitioners Prioritizing Biopsychosocial Pain Management?

- Lack of Emphasis in OT Programs (especially acute pain)?

- Surely Another Healthcare Profession(s) Addressing it?

- Feeling Pressured for Time or Other Interventions?

- Unsure Where to Start, Or What Interventions to use?

- How Do you Even Speak to a Person in Pain??

- Older Models of Pain Neurophysiology Still Being Taught!!!

Why aren't more OT practitioners prioritizing biopsychosocial pain management, especially for an acute pain state? There seems to be a lack of emphasis within OT programs. I was part of another presentation recently where 40% of our participants said they did not feel like their programs addressed this model or talked enough about acute pain. In an acute pain setting, is another healthcare profession is addressing it? Do we feel too pressured for time, or are we doing other interventions? I have worked in many settings, including acute care. It is very fast-paced, and I understand you may only see that person for an evaluation or only a couple of sessions before transitioning to another setting. How can we prioritize this? Perhaps, you are unsure where to start or what interventions to use. A person in pain can be very emotional and vulnerable. How can we validate their feelings and address them? And, nerve physiology and older models of pain may still be taught in schools.

Pain Neuroscience Education

The What

- Neurobiology + Neurophysiology = Neuroscience

- Bio<--->Psychosocial

I was trained in the concept of pain neuroscience education, but honestly, we do not need to call it that. A new paper that is coming out for pain management is referred to as pain science or pain neurophysiology. This is combining neurobiology and neurophysiology as neuroscience. All pain involves the nervous system, including neurobiology, neurophysiology, and especially neuroplasticity, which we know is changeable. We can really empower our clients with that understanding. This also incorporates a biopsychosocial understanding of all types of pain, including acute pain.

The Why

- When Our Clients Understand Their Pain, They Have…

- Less Disability

- Move Better

- Improved Pain Cognitions (positive view of pain)

- LESS PAIN (Treat vs. “Manage”)

- Reduced Risk of Transition From Acute to Chronic Pain

- Increased Engagement In Desired Activities!!!

Why is it so important that we, as OT practitioners, better understand this new pain neurophysiology? When our clients understand their pain, they not only have less disability and move better, but they have improved pain cognition or a positive view of pain. Pain can be experienced as being a negative thing. So when we can empower our clients with that understanding, we can really flip that around. "This is something I can manage." Research has shown that they will have less pain.

We are going to talk a bit more today about the overall level of pain and threat perception. This can help to reduce pain intensity. We also want to talk today about a reduced risk of transition from acute to chronic pain. We cannot possibly reduce that risk completely. You want to make that very clear as that gets into things like epigenetics. That is beyond the scope of this presentation today. I am giving a broad overview, but feel free to email me if you want more information. When our patients understand their pain, they have increased engagement in their desired activities. That is what we want as OT practitioners, and we can be their guide.

Why Do We Even Have Pain?

- “An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage” (IASP, 2020)

- Pain = Normal and Necessary Experience

- Alert to Danger + Protection + Teaching = Survival

- Pain = Normal and Necessary Experience

Pain is a sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage. It is important to understand that all pain, including an acute pain experience, is sensory, but there is also the emotional component (actual or potential). When thinking about threat perception, it is also important to understand that it alerts us to danger, it protects and teaches, and it is about survival.

Cartesian Model

- Place Foot in Fire, Message Sent to Brain via Pathway/Wire

- Message Sent to Brain (Center of All Senses)

- Injury (Due to Fire) Pulled a Rope to Make a Bell Ring at the Other End in Brain

(Goldberg, 2008)

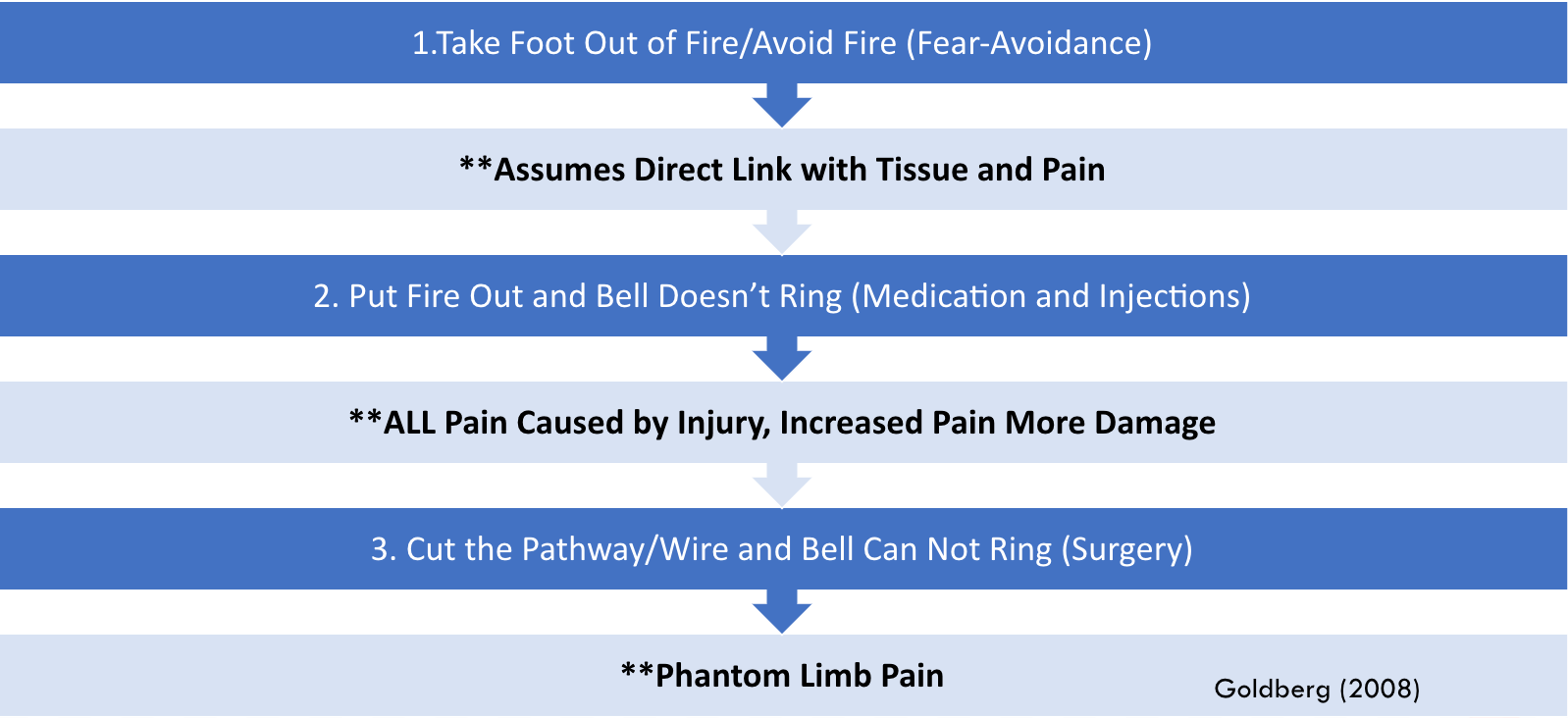

There were other models of pain introduced this week. I wanted to compare and contrast the old Descartes or Cartesian model from the 16th century to the Biomedical Model described in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Three options for pain.

For the Descartes Model, the thought was that if you were to place your foot in a fire, the message was sent to the brain via a pathway that was the center of all senses. Then, the pain message rang a little bell in the brain. There are definitely some problems with this theory. One would think based on the earlier thinking that once you take your foot out of the fire, there would be no more pain. This assumes a direct link between tissue and pain. I am sure we can think of some of our clients that are not moving or doing anything, and they still have significant amounts of pain. Remember, they thought that if the fire was out that the bell would not ring.

This theory also supposed that an injury caused all pain, and increased pain would mean more damage. However, we have all had paper cuts, and those really hurt. I am sure we can think of other examples where people had significant amounts of tissue damage and not a lot of pain. Many examples are in contrast with this.

Finally, we look at the cut pathway. If it is cut, there should be no more pain. Research shows that the body part being absent does not stop the nervous system from experiencing pain. Phantom limb pain is an example.

Mature Organism Model-MOM (Biopsychosocial Model)

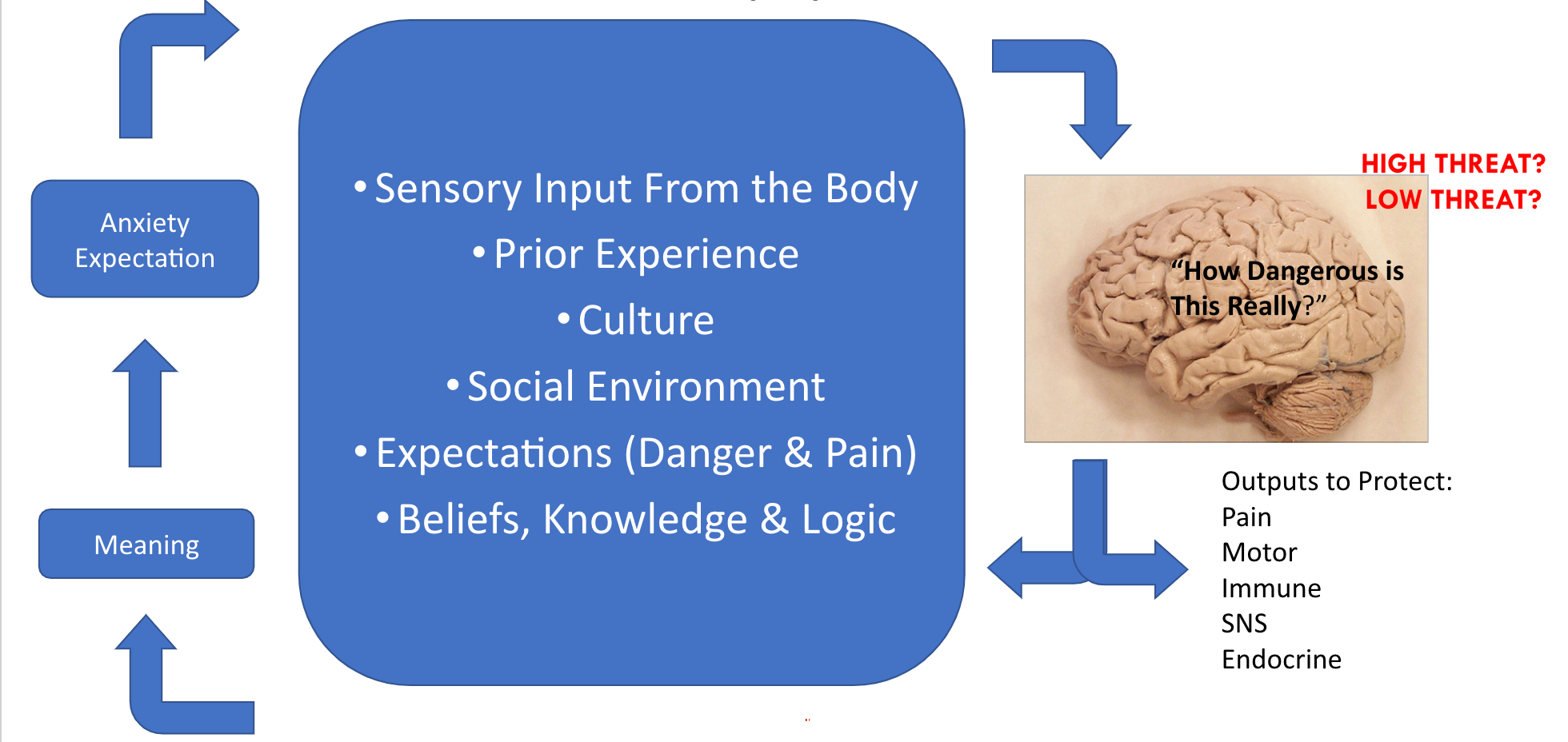

Figure 5 shows what is termed by Gifford as the Mature Organism Model.

Figure 5. Mature Organism Model.

This is really the best representation out there and a way to educate our clients on pain physiology. The brain is asking the following questions. How dangerous is this? Is this threatening to us? Is this a low threat? Earlier this week, a question asked if the memory of pain can produce pain. Yes, and there are great examples in the literature. For example, someone may drive by the scene of their car accident and have those feelings again. This is because of the earlier sensory input of that prior experience, culture, and social environment. Being mindful of things like social determinants of health, racial aspects, and experiences, especially to expectations, are crucial. Is this supposed to hurt me? Is this a new injury or a re-injury? There are so many aspects that really turn that dial-up. If the brain feels that something is dangerous, it will output pain and stimulate the motor, immune, sympathetic, and endocrine systems. Our new understanding of pain is that pain is an outcome. To better explain this new broad concept, I always like to share the story, which really resonates with people.

- Ankle Strain Vs. Bus

- Pain is a brain construct, not a tissue construct!

This is a metaphor that I encourage you to use. Let's pretend that I am crossing a busy road and I sprain my ankle. I always ask my clients, at this point, "Is my ankle going to hurt?" The majority of the time, they say, "Yes, your ankle is going to hurt." There are nerves in the ankle, and those release chemicals and send signals. The nociception signal goes up my leg, to my spinal cord, and ultimately to the brain. My brain says, "I need to increase the output to protect the ankle and keep her off of it." Meanwhile, I am in the middle of a busy road, and the bus driver does not see me. What am I going to do? Most people say that you would get up and run out of the way. We understand now with that fight or flight response that our bodies are capable of producing the strongest pain killers known to man. These are endogenous opioids, our own endorphins. Our bodies send these out to dial back the nerve output in that ankle area to allow me to avoid the bigger threat. In the bus versus ankle scenario, the bus is going to win every single time. Once I get on the other side of the road, I ask my clients to tell me what happens next. They will say, "Your ankle is going to start hurting again." I have now run on my ankle but could the tissues themselves really have changed in that time? The answer is no. What has changed is the threat perception and the release of chemicals. It is important to understand that the nerves and the pain response can be dialed up or down depending upon the situation.

Figure 6 shows the nervous system.

Figure 6. The nervous system (CC By 2.0).

This is 45 miles of individual nerves. It is over 400 interconnected nerves that act as an alarm system. If you show this to your clients, it gives them a better understanding of how this works.

Factors Related to Pain Experience: "The Client's Story"

- Environmental Factors

- Social Factors (including SDOH)

- Injury/Surgical History

- Psycho-Emotional Factors

- Trauma-Related Factors

- Behavioral/Personality Factors

- Lack of Knowledge/”Unknowns”

(Linton & Shaw, 2011; Louw et al., 2018; Linton & Kienbacher, 2020)

When we look at an individual pain experience, this is when we need to put on our detective hats. Two people can have the same injury but two incredibly different pain experiences. Acute pain experiences do not happen in a vacuum, and there are many different environmental and social factors, including social determinants of health, that go into it. Do you feel heightened stress because you have a lot of things going on in your environment? This also considers different racial aspects and any factors that would affect a person's day-to-day experiences. We also want to look at surgical history. Have they had a fracture before? Many folks will say, "This is my first fracture." Based on that Mature Organism Model (the Biopsychosocial Model) that we just reviewed, this could be very threatening and put the person on high alert. Their brain is thinking that it is threatening and dangerous because they have nothing to compare it to. Many other emotional, behavioral, and personality factors also go into the experience. A lack of knowledge or the "unknown" can exacerbate things as they go through that acute pain experience. We can educate them to bring that threat response down to help with pain intensity.

IASP Curriculum Outline on Pain for OT

Psychological, behavioral, social, and spiritual components of the pain experience, their relation to activities, and relationship to acute or chronic nature of pain

- Anxiety, avoidance, crisis reactions, stress, catastrophizing, life adjustment process

- Spirituality, meaningfulness, hope, and hopelessness

- Psychology of unrelieved pain, control, and self-efficacy

- Depression, wish to die, suicide

- Occupational performance and quality of life

- Pain communication

Suffering and pain

(International Association for the Study of Pain, 2018)

The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) also has a curriculum outline on pain for occupational therapy practitioners. I encourage you to go to the website and check it out. You can see the different psychological and social aspects that we, as OT practitioners, can and should be addressing as part of that interdisciplinary team. These are just as applicable to an acute pain experience as they are to chronic pain. We need to be asking more about the pain experience beyond a number on a pain scale.

Stress Response: Running on High Alert!

- “Fight or Flight” (or Freeze!):

- Adrenaline

- Shallow Breathing

- Increased HR and BP

- Guarded Muscles

- HIGH THREAT

- E.g., Post-MVC; Post-Trauma; ACEs

- *Brain Doesn’t Know the Difference*

(Louw et al., 2018)

Let's get back to that stress response system. I was thinking about this today. I have done many presentations on this topic, but I still feel my heart rate go up as my stress response system kicks in. This makes sense, and I anticipate that response. I also know that I am going to try to get some good sleep tonight.

We are going to talk about sleep today. It is so important, especially for our clients with a fight or flight response. We can also freeze because we feel trapped, which is a normal response to that stressor. We can also have an adrenaline rush, shallow breathing, increased heart rate, and guarded muscles. A great example of this is any injuries after a motor vehicle accident. Think about how that stress response system can stay really elevated. This also occurs with adverse childhood experiences or ACEs. There may be a lot going on at home with many different stressors that keep the stress response elevated. If a stress response remains elevated, this can keep the nervous system on high alert and contribute to pain symptoms.

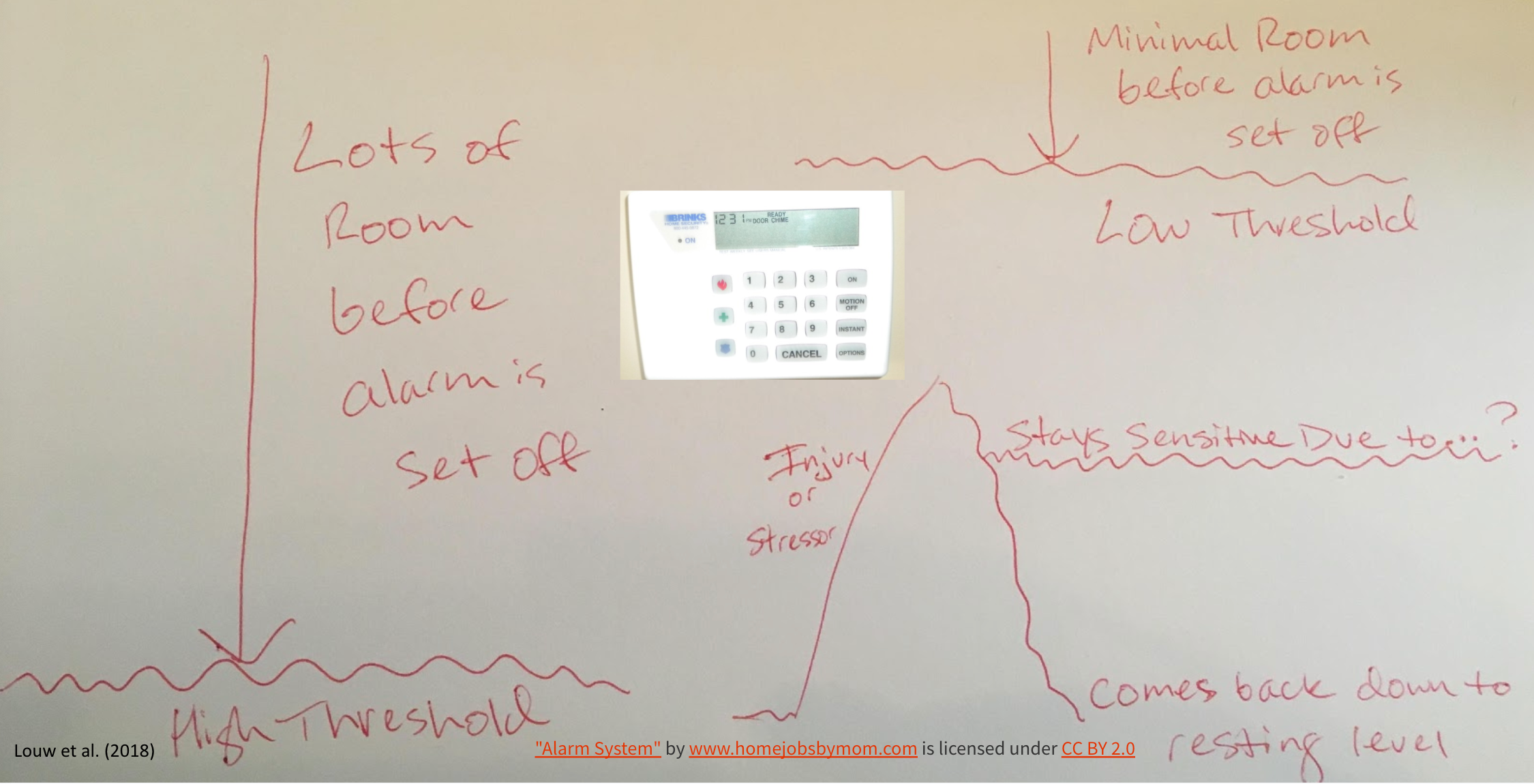

Nervous System as an Alarm System

This is another beautiful metaphor for our clients to understand better the nervous system as an alarm system (Figure 7).

Figure 7. The nervous system acts as an alarm system.

Our bodies are setting that alarm off because they are trying to get our attention. They want us to do something about that threat response. I am not just talking about a physical injury. This can be elevated stress and feelings of threat like with adverse childhood experiences. The sense of a lack of safety can create a minimal threshold. This can also apply to the new onset of acute pain. For instance, let's use post-surgical pain as an example. The surgical area is pretty sensitive as it is being protective. Some movement might trip the alarm. If it heals, then that threshold changes. However, what if you threw in some new acute stressors during that time? This system might then stay sensitive and be on high alert. Research says that one in three people have a sensitive and elevated nervous system. In the case of acute pain, how do we help that person find ways to help their nervous system come back down to that resting level?

Ion Channels: "Nerve Sensors"

There are ion channels or nerve sensors, as noted in Figure 8.

Figure 8. Ion channels are nerve sensors.

We will touch a little bit on neurophysiology and look at ion channels, and nerve sensors as these help us understand what is going on. There are also different factors like temperature, stress, movement, immunity, and blood flow.

- Temperature

- Stress

- Movement

- Immunity

- Blood flow

For example, if it is freezing outside and you feel chilled, your body naturally tells you that it is cold outside. Our bodies produce more ion channels or sensors for temperature for us to do something about that. There are also ion channels for stress. In that motor vehicle accident example or the event of a pending surgery, these are inherently stressful. Due to this, more ion channels or nerve sensors are receptive to stress because the brain and body are trying to get your attention. There are also heightened nerve sensors for movement. Let's say you are treating somebody with a distal radius fracture, and they have been immobilized for awhile. There will be many nerve sensors in that wrist for movement because it has not been moving, and it is sensitive. If we move it only a little bit at a time, these nerve sensors can adjust and be less sensitive. There can also be heightened stress and blood flow.

I also want to mention that our nerves like three things: good blood flow, space, and mobility. Helping our clients understand that getting a little more blood flow, movement, and more space by reducing edema can help the pain.

Pain Pathways

- Nociceptive

- Proportionate pain, aggravating/ease

- Intermittent sharp, dull ache or throb at rest

- No dysesthesia, burning, shooting, or electric

- Sensitivity 90.9%

- Specificity 91.0%

- Dx odds ratio 100.67

- Peripheral Neurogenic/Neuropathic

- Pain in the nerve distribution

- + neurodynamic & palpation (mechanical tests)

- Known nerve pathology or compromise

- Sensitivity 86.3%

- Specificity 96.0%

- Dx odds ratio 150.9

- Central Sensitized/Nociplastic

- Disproportionate pain (illogical)

- Disproportionate aggravating/ease

- Diffuse palpation

- Strong association with maladaptive psychosocial factors

- Sensitivity 91.8%

- Specificity 97.7%

- Dx Odds Ratio 486.56

I wanted to share some of the key differences between nociceptive versus neuropathic central sensitization. This does not mean that you are not going to see a mixture of some of these things. In fact, this better explains why sometimes, after an injury or post-surgery, people might say, "I have some burning symptoms radiating down my leg." This tells us that the person's nervous system is already getting a little bit sensitized with some spreading pain. Be on the lookout for that. There are ways to address this that are incredibly important to understand.

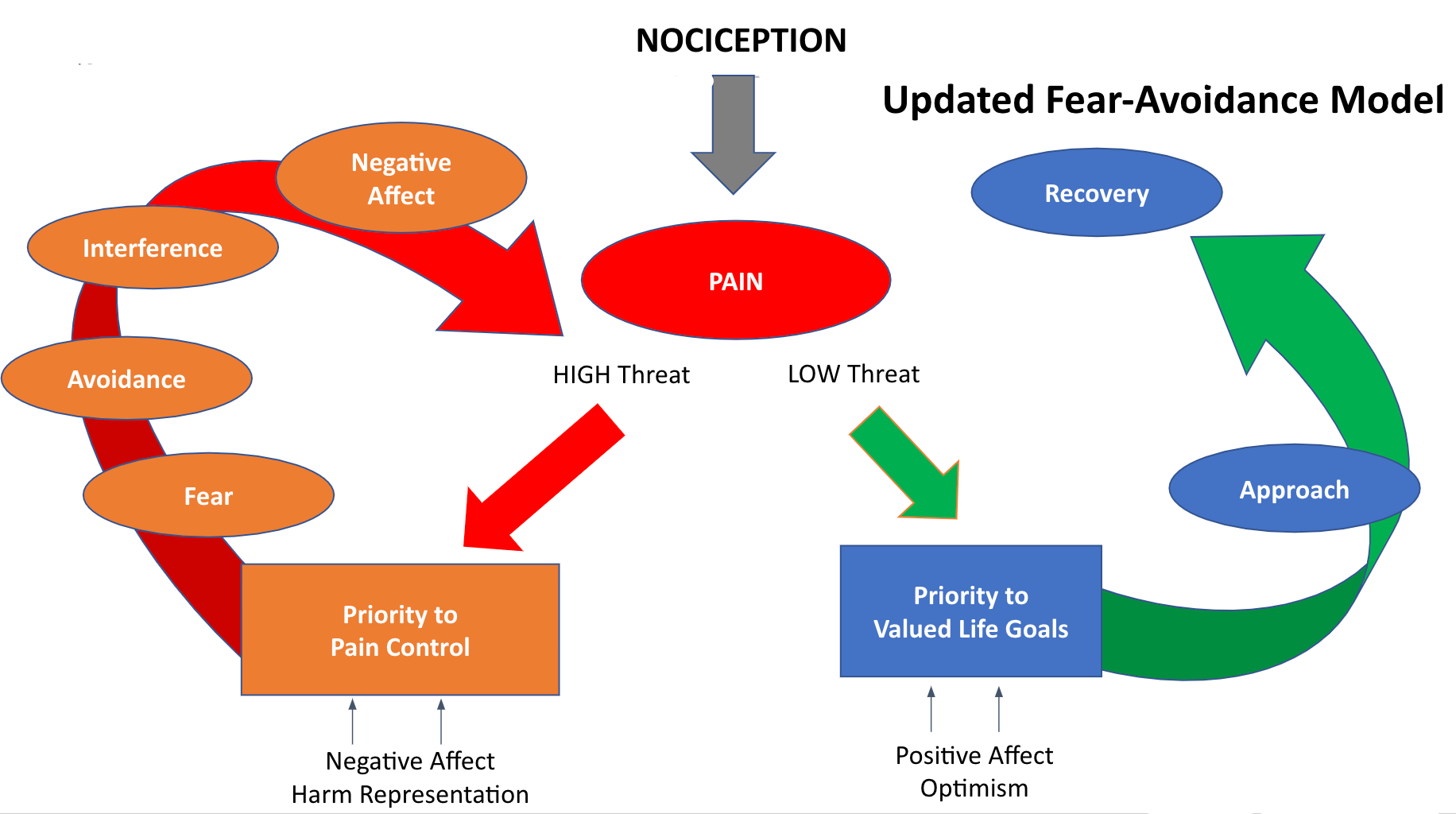

Nociception (Fear-Avoidance)

Figure 9. Nocioception or Fear-Avoidance Model.

Put a big star next to this model. The Fear-Avoidance Model helps us better understand why there are differences in how people experience pain and how pain is less for some. You can see on the left that there is a high threat side with a negative harm representation. "If it hurts, do not do it." This is turning an acute pain experience down into something chronic.

On the other hand, we can also try to help keep that threat low by helping the person understand that fractures heal, and there are things they can do. They need to prioritize valued life goals and have a positive affect, and remain optimistic. Doesn't this sound like something that we as OT practitioners are so adept at doing with our therapeutic use of self? If we can meet the person where they are within their acute pain experience, we can help to keep the threat low try to empower them.

Risk of Acute Pain to Chronic Pain: Neuroplasticity

- Risk factors with negative emotions & depression, sleep loss = CHRONIC STRESS

- Increasing severity of pain and depression link is STRONGER

- Hippocampus changes

- Processing/modification of nociceptive stimuli

- Neurogenesis

- Volume loss with chronic stress, pain, susceptibility to anxiety

- For protection, the brain turns OFF feedback with the HPA axis, increase in cortisol/inflammation (neurotoxicity)

- Formation of painful memories (protection via learning…)

- Reduced capacity to activate central opioid neurotransmission

- Predictive of transition from acute to chronic pain

- Decrease cognitive and emotional distress caused by acute pain to reduce risk of transition to chronic pain

(Hashmi et al., 2013; Baliki et al., 2012; Baliki et al., 2015; Fields, 2006; Apkarian, 2008

Nociception does not have to be an injury or an accident. We are going to see that when we talk about different stressors. There is a high correlation between feeling negative emotions with depression, sleep loss, and chronic stress. Different parts of the brain keep that stress response system on high.

The brain functions with an acute pain experience are quite a bit different from a chronic pain experience. Acute pain is more sensory-based; whereas, chronic pain is related to the areas of the brain, like the amygdala, that are heightened with anxiety and fear. The takeaway is that if the threat response is ongoing, our body, to protect us, will produce its own painkillers. It will not dial down the response if the threat is ongoing. Over time, people with persistent pain state are less able to activate their own opioids (endogenous chemicals), which can be very predictive of a transition from acute to chronic pain. Can we help people with their cognitive and emotional distress? This is not to say that people should not have feelings and emotions during acute pain. Normal responses are anger, fear, and frustration. However, I am sure that we can agree that if they were to continue and persist in that heightened arousal, this might cause the transition from acute to chronic pain.

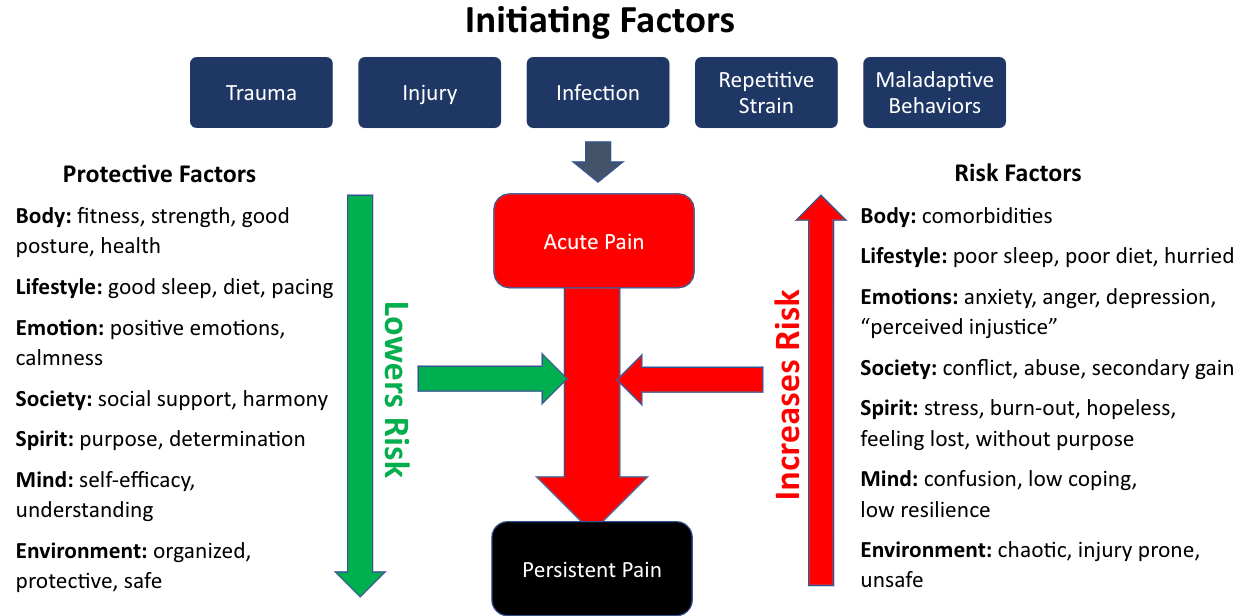

Biopsychosocial Risk and Protective Factors

If I could star another slide for everyone, it would be this one. Figure 10 is from a great article by Friction et al. from the site practicalpainmanagement.com. They produce their own content, and I would really highly encourage everyone to check that out as a resource.

Figure 10. Initiating factors for pain.

You can see the different initiating factors on the top. These include trauma, injury, infection, repetitive strain, and maladaptive behaviors. There may not be actual physical tissue damage, but the fight or flight response is ongoing or other behaviors, and then an acute injury and pain are layered on. Look at the right-hand side of the different risk factors that can influence pain. I want to highlight a few like emotions and "perceived injustice." This is a fundamental concept.

Let's go back to that motor vehicle accident example. There could be continued litigation and a court battle. People may feel that they suffered injustice because the car accident happened to them. Research shows a high correlation between an acute pain state and injuries transitioning on to persistent pain with this perception. We can help clients understand that and help them identify coping techniques to lower that risk.

On the left-hand side, there are many protective factors. These are many things that OT practitioners can address to reduce the risk of that transition from acute to persistent pain in the future.

Pain Article

Prediction of Persistent Post-Operative Pain: Pain-Specific Psychological Variables Compared with Acute Post-Operative Pain and General Psychological Variables

- Outcome Measures:

- Numeric Pain Scale

- Pain Catastrophizing Scale

- Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale = PASS

- Pain Vigilance and Awareness Questionnaire (PVAQ)

- General Psychological Screening (Somatoform Symptoms, State-Anxiety Inventory-X1, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale = CES-D).

- Results: “3 months after surgery […] Acute post-operative pain, as well as general psychological variables, DID NOT allow for a significant prediction of persistent post-operative pain; in contrast, pain-related psychological variables did. The best single predictors were PASS and PVAQ.”

- Conclusions: “Pain-related psychological variables derived from the fear-avoidance model contributed significantly to the prediction of persistent post-operative pain. Our results suggest that pain-specific psychological variables such as pain anxiety and pain hypervigilance […] might even outperform established predictors such as acute pain and general psychological variables.”

Horn-Hofmann, C. et al. (2017)- European Journal of Pain

I wanted to highlight the conclusions from this article that pain-related psychological variables are derived from the Fear-Avoidance Model. These contribute significantly to the prediction of persistent postoperative pain. They looked at variables such as pain-specific anxiety, pain, and hypervigilance. Most of us can understand a heightened fear of pain or fear of movement after a procedure. OT practitioners can be the ones that work with somebody on those factors to reduce the risk of persistent postoperative pain.

Intervention: Safe, Healing Environment, and Pain Experience

Therapist-Client Engagement

- The Importance of Therapist-Client Engagement (NOT just interaction):

- Present

- Receptive

- Genuine

- COMMITTED

- Acknowledge the individual and touch/use the body

- Improved treatment adherence, physical functioning, mental health, satisfaction with treatment, and REDUCED PAIN

- Words that Harm, Words that Heal (Stewart & Loftus, 2018):

- Vital Importance After Surgery or Injury (Encouragement of Healing): Vicki Example

- Trust .1 sec! (Willis, J. & Todorov, A., 2006)

(Benedetti, F., 2011; Miciak, 2015; Hall et al., 2010)

We want to create a safe, healing environment for our clients in pain. Again, you may only see them one time as an acute therapist. However, trust can be fostered in only a 10th of a second using therapeutic use of self and being present. This has been shown to improve treatment inherence, physical functioning, mental health, and reduced pain. When you are empathetic and compassionate when first meeting someone, you hold space with them. Even in that hospital room, this is a skilled intervention to help address pain. This helps to bring their nervous system's alarm system down. You also want to think about words that harm and words that heal.

I wanted to give a client example, Vicky. She asked me to share this. She had so much fear after a new injury post motor vehicle accident. When her surgeon went over her x-rays and showed her everything that was healing, her pain dropped from a 10 out of 10 to a four. She knew her body was healing, and her pain went down as a result. The knowledge that her doctor imparted turned down the dial and made a big difference. Thus, we need to be cognizant of our language when we speak with our clients to decrease their threat perception.

Therapeutic Use of Self

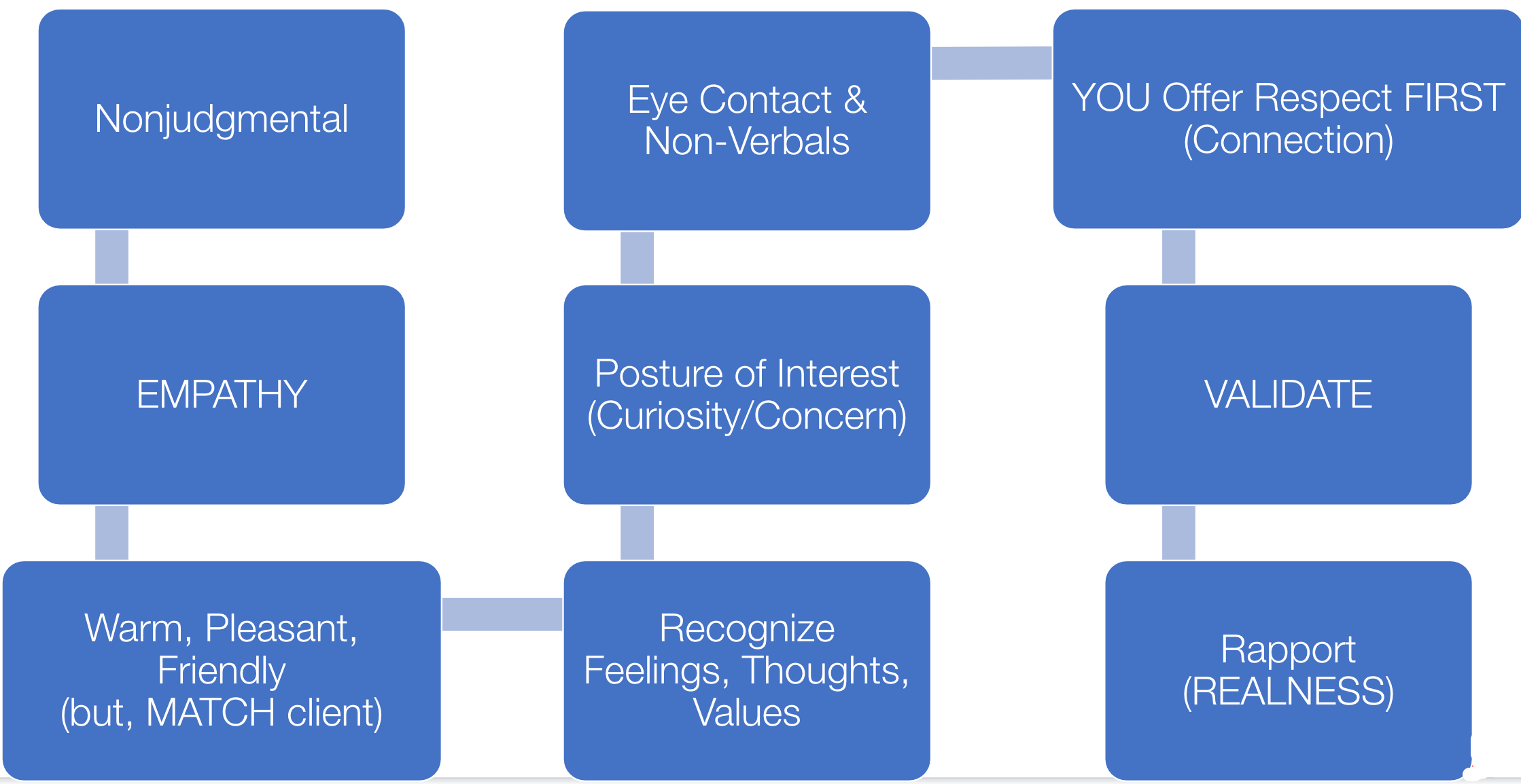

Therapeutic Use of Self factors are listed in Figure 11.

Figure 11. Factors with the therapeutic use of self.

I know I am preaching to the choir here, but I just want to recognize how important these factors are. This is a skilled intervention that can help with pain interference and intensity, especially in acute and chronic pain states.

- Therapeutic Alliance (Therapeutic Use of Self)

- Enhanced Therapeutic Alliance Modulates Pain Intensity and Muscle Pain Sensitivity in Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain: An Experimental Controlled Study

- Important Themes: Focused therapeutic alliance statistically significant change in numerical pain ratings and pain sensitivity.

- (Fuentes, J. et al., 2017)

- Important Themes: Focused therapeutic alliance statistically significant change in numerical pain ratings and pain sensitivity.

- Characteristics of Therapeutic Alliance in Musculoskeletal Physiotherapy and Occupational Therapy Practice: a Scoping Review of the Literature

- Important Themes: Prioritized goals, autonomy support, and motivation were facilitators of a therapeutic alliance.

- Babatunde, F. & MacDermid, J. & MacIntyre, N. (2017).

- Important Themes: Prioritized goals, autonomy support, and motivation were facilitators of a therapeutic alliance.

- Enhanced Therapeutic Alliance Modulates Pain Intensity and Muscle Pain Sensitivity in Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain: An Experimental Controlled Study

I have also listed a few articles that discuss therapeutic alliance as these can statistically provide a significant change in numerical pain ratings and pain sensitivity. Our creation of safety and compassion is capable of helping with that pain interference for somebody. We help our clients feel that their goals are prioritized. They have more autonomy and motivation when we engage in that therapeutic alliance and use our therapeutic use of self.

Other Positive Factors

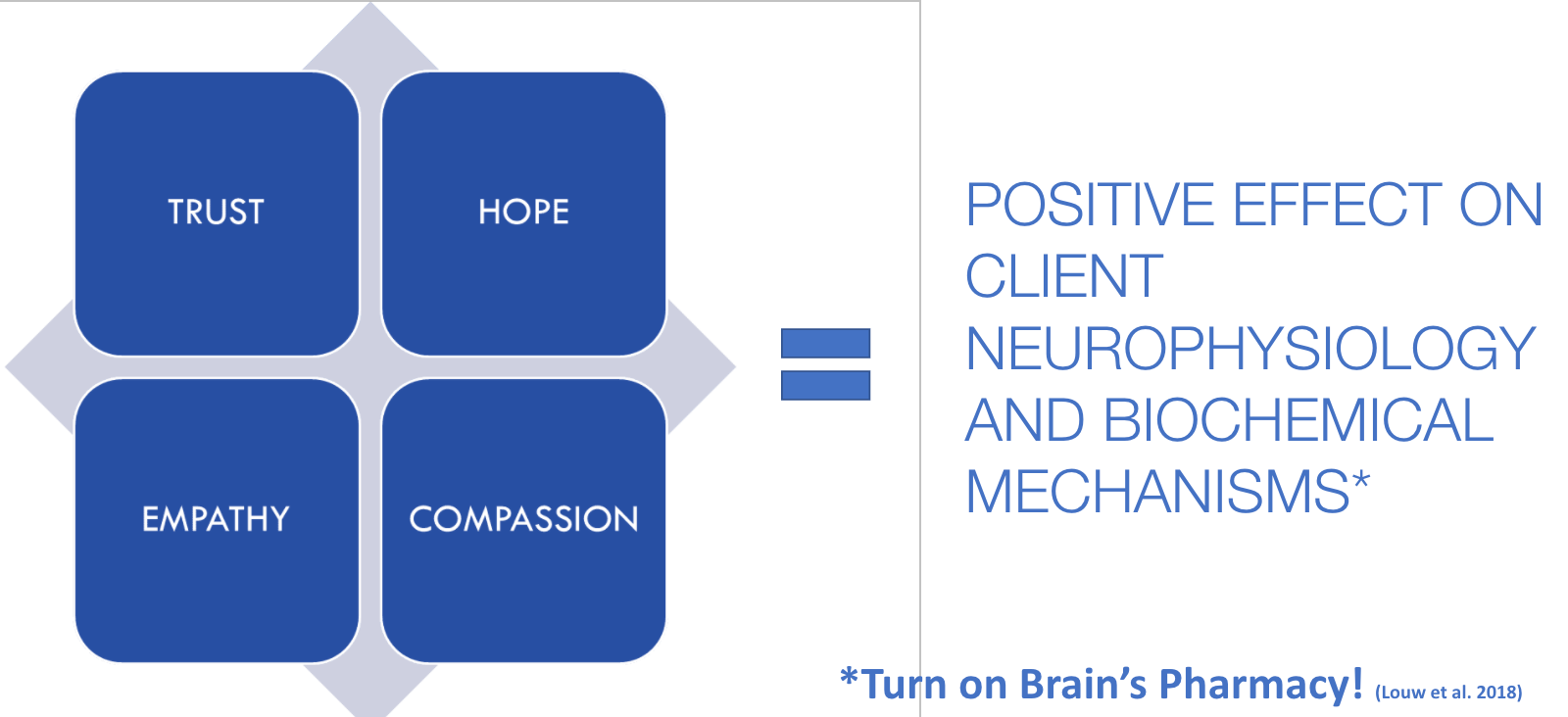

I know that Lindsay touched a bit on this yesterday, and I want to talk about this again within an acute pain experience. Trust, hope, empathy, and compassion have been found to have a positive effect on client neurophysiology and biochemical mechanisms.

Figure 12. Other factors for a safe and healing environment.

We are trying to turn on the brain's pharmacy. I spoke earlier about that persistent pain state where there is an elevated stress response. Access to feel-good chemicals and endogenous opioids are not available during these times. However, when we provide trust, hope, empathy, and compassion, this can bring down the threat perception and alarm system to release the client's own feel-good chemicals again.

Empathetic Healers

- Decatastrophize-NORMALIZE

- Decrease FEAR and ANXIETY

- Validate:

- Loss of Independence

- Loss of Self

- Shame

- Guilt

- LOSS OF CONTROL

- Positivity and Excitement!

- WE ARE GUIDES

- "Empower"

Being empathetic healers is what OT practitioners do best. We validate the loss of independence, self-shame, and guilt related to the pain experience. We are guides to empower that person to go on to that recovery to help them find themselves again.

Intervention: Emotional Well-Being and Pain Experience

- Fear of increased pain with activity

- Loss of enjoyment

- Irritability!

- Anxiety about a heightened awareness of body sensations

- Under STRESS and unable to maintain CONTROL

- Feeling useless (burden to staff, family, friends)

- Emotion/mood state directly affects recovery and perception of pain

(Gifford, 2014)

Emotional wellbeing is affected by the fear of increased pain with activity. This is understandable after an injury. There can be a loss of enjoyment, irritability, and anxiety. There can be a heightened awareness of body sensations. Going back to an example of a new fracture, that is a lot of new sensations. They also may not be aware or in tune with their body. It can be overwhelming with all of the sensory information, and they may feel out of control. This situational acute stress response is not what they wanted or asked for. They can feel useless. I have many clients who have felt like a burden. They may not want the staff to help them to use a bedpan. Many of these feelings influence also elevate the threat/pain response. All of these things are interrelated, and again, mood and emotion directly affect recovery and the perception of pain.

Intervention: Coping and Pain Experiences

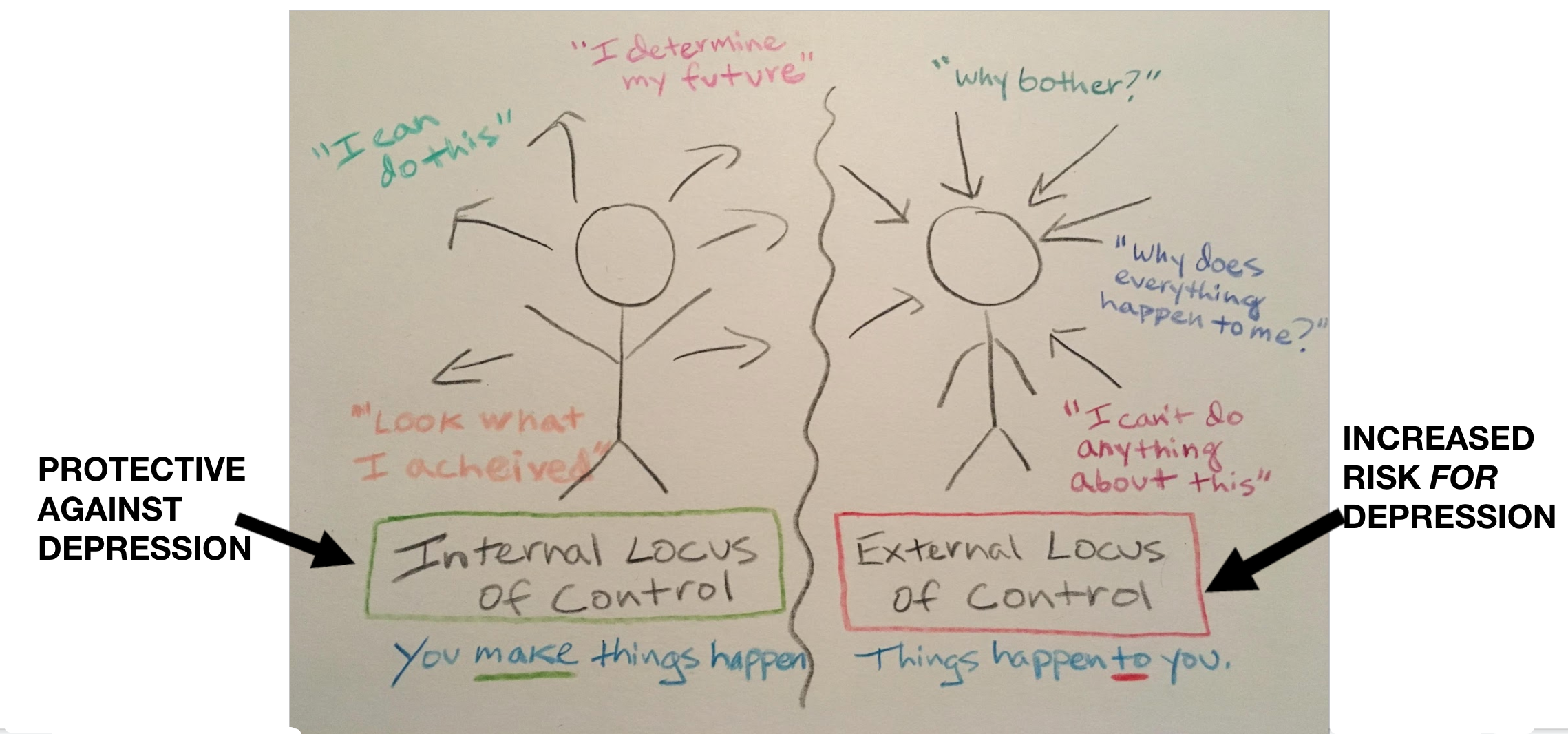

Locus of Control

I wanted to talk about that self-efficacy and locus of control. This is my drawing in Figure 13, representing internal and external loci of control.

Figure 13. Internal vs. external locus of control (Sapolsky, 2004).

With an internal locus of control, you make things happen versus things happening to you. This graphic also shows some of the phrases (both positive and negative) to be on the lookout for with clients. An internal locus of control is protective against any type of situational depression or transitioning to depression versus that external locus of control. This goes back to that perceived injustice. Why does everything happen to me?

Different Types of Coping

- Problem Focused

- Active- Take Steps

- Plan- Think On It

- Suppression of Competing Activities-ONLY Focus on Problem

- Restraint-Wait for Right Moment

- Instrumental Social Support-Seek Advice

- Lilman, J. A. (2006). The COPE Inventory.

- Emotion-focused

- Positive Reinterpretation- Reframe in Positive Terms (Self-Talk)^

- Acceptance- Learn to Accept Problem

- Religion- Faith for Support

- Emotional/Social Support-Seek Sympathy from Others

- HUMOR

- Venting*

- Behavior/Mental Disengagement*

- ^endogenous release/immune

- *"Less Useful"

- Maladaptive

- Denial- Refuse to Believe Problem is Real

- Catastrophizing

- Bandura et al. (1988)

Again, we need to listen to our clients' language to hear the different coping types that they might use. Are they problem-focused? Are they focusing on their emotions? Positive re-interpretation or reframing things in positive terms has been shown to release endogenous chemicals. A great example is one of my clients who decided she would sell her home and go to an assisted living facility. Before she decided, she was having a lot more pain and difficulty moving due to a fracture. Suddenly, she is now in a positive frame of mind and is focused on moving and being able to get up. You could see that switch. She began using a lot more positive self-talk and reporting less acute pain intensity as well.

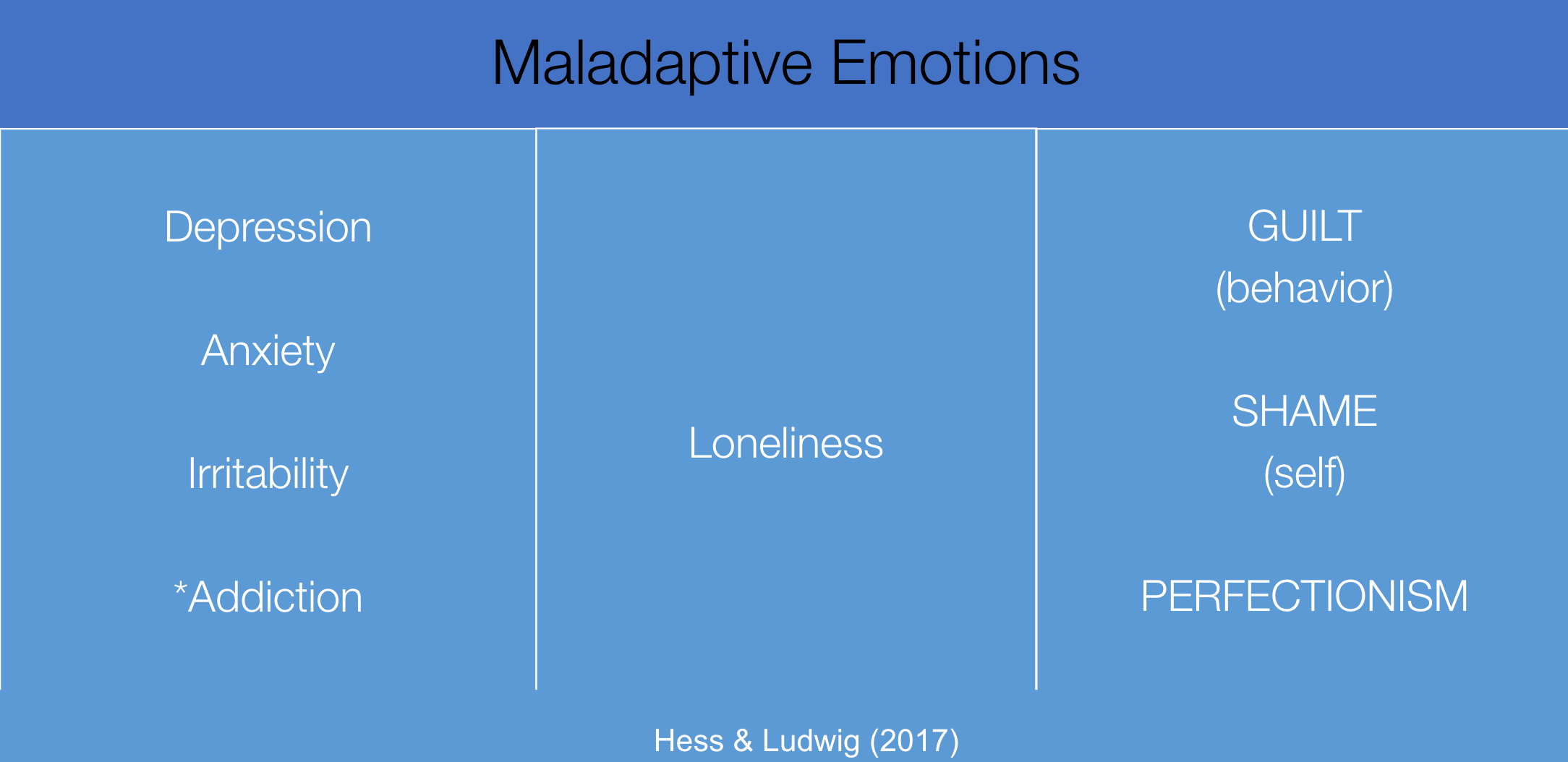

Maladaptive Emotions

We also want to be aware of maladaptive emotions in Figure 14.

Figure 14. Examples of maladaptive emotions (Hess & Ludwig, 2017).

It is critical to know the difference between guilt versus shame and a lack of self-compassion. This is highly correlated with the risk of a transition from acute to persistent pain.

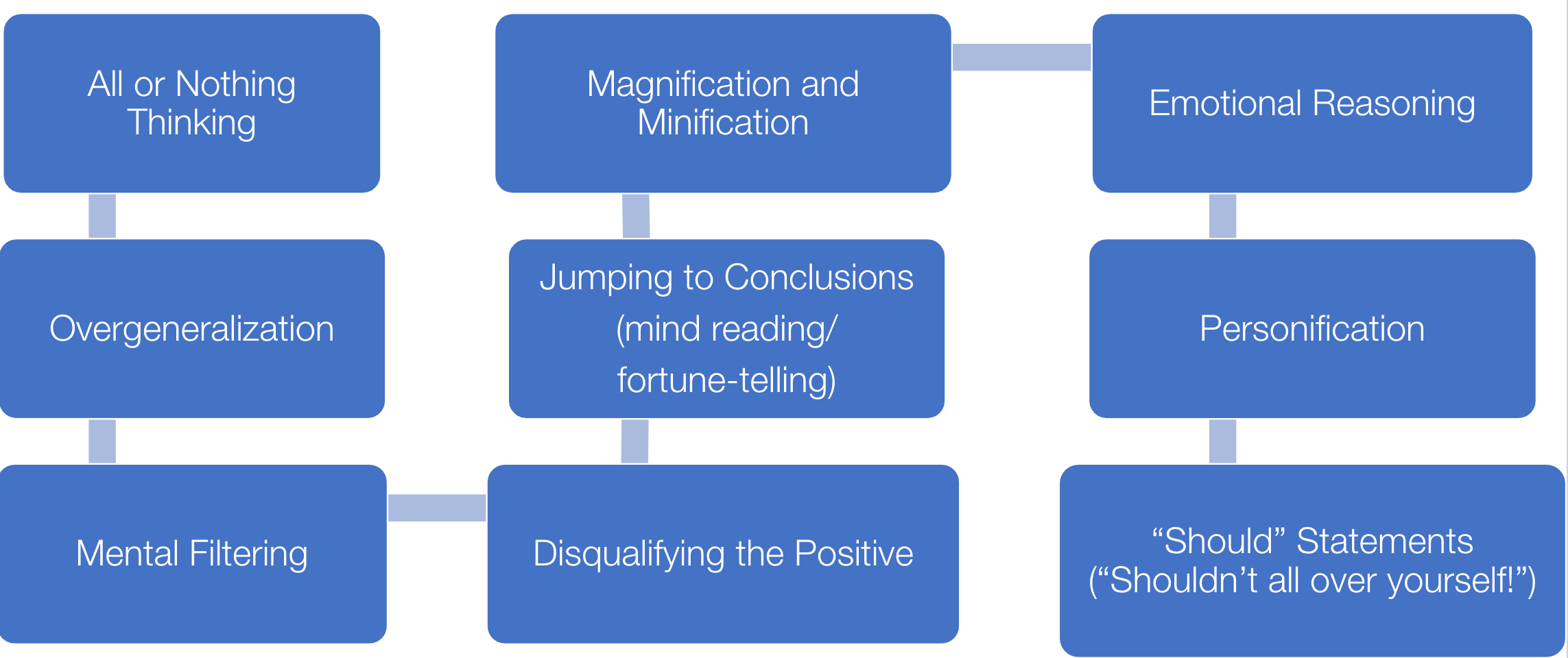

Cognitive Distortions

Part of that is recognizing cognitive distortions listed in Figure 15.

Figure 15. Cognitive distortions (Bandura et al.,1988).

I want to highlight the last one with the "should" versus "shouldn't." These are statements like, "I should have done that," or "I should not have done this."

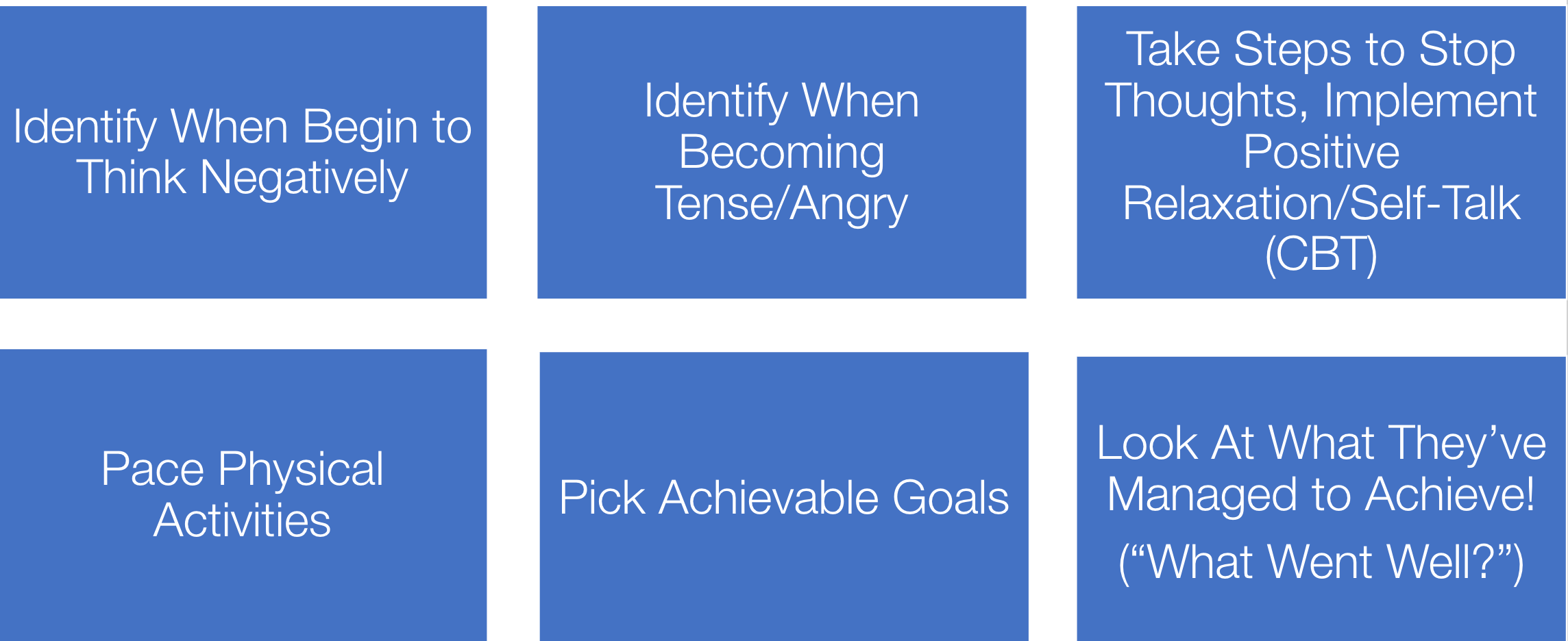

Guided Coping

We also want to guide their coping (Figure 16).

Figure 16. Guided coping examples (Bandura et al.,1988).

We want to catch clients when they begin to think negatively. We need to know their experience and how their rehab process has been. We want to know when they are tense and angry and understand that this might increase their pain. We want them to stop the negative thoughts and help them implement relaxation, positive self-talk, pacing activities, and achievable goals. I also love talking about reflection during sessions. "What went well today? Oh, wow, you walked that far earlier today with physical therapy. That's fantastic." These are the positive strategies on the right side of the Fear-Avoidance Cycle that we saw earlier. You want them to reflect on what they have achieved to bring down the threat perception.

The whiteboard is an example of something I have done in Figure 17. I have written this on people's whiteboards in their inpatient rooms.

Figure 17. Example of positive talk on a client's whiteboard.

These are things that you can do to help the client to reflect on positive ideas.

- Emphasize interventions:

- Decrease brooding & negative rumination (e.g. mindfulness) vs.

- Emphasis on positive rumination (decrease the maladaptive)

- Recognizing inner chatter

- “The stories we tell ourselves…”

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT)

We need to help them understand their inner chatter or "the stories we tell ourselves." I also wanted to bring up acceptance and commitment therapy. Research has been shown that this has efficacy in acute pain instances as well. Hopefully, this makes a lot of sense. The client needs to take on those pain sensations for what they are and accept those. "This is temporary, and I have strategies that will make it better."

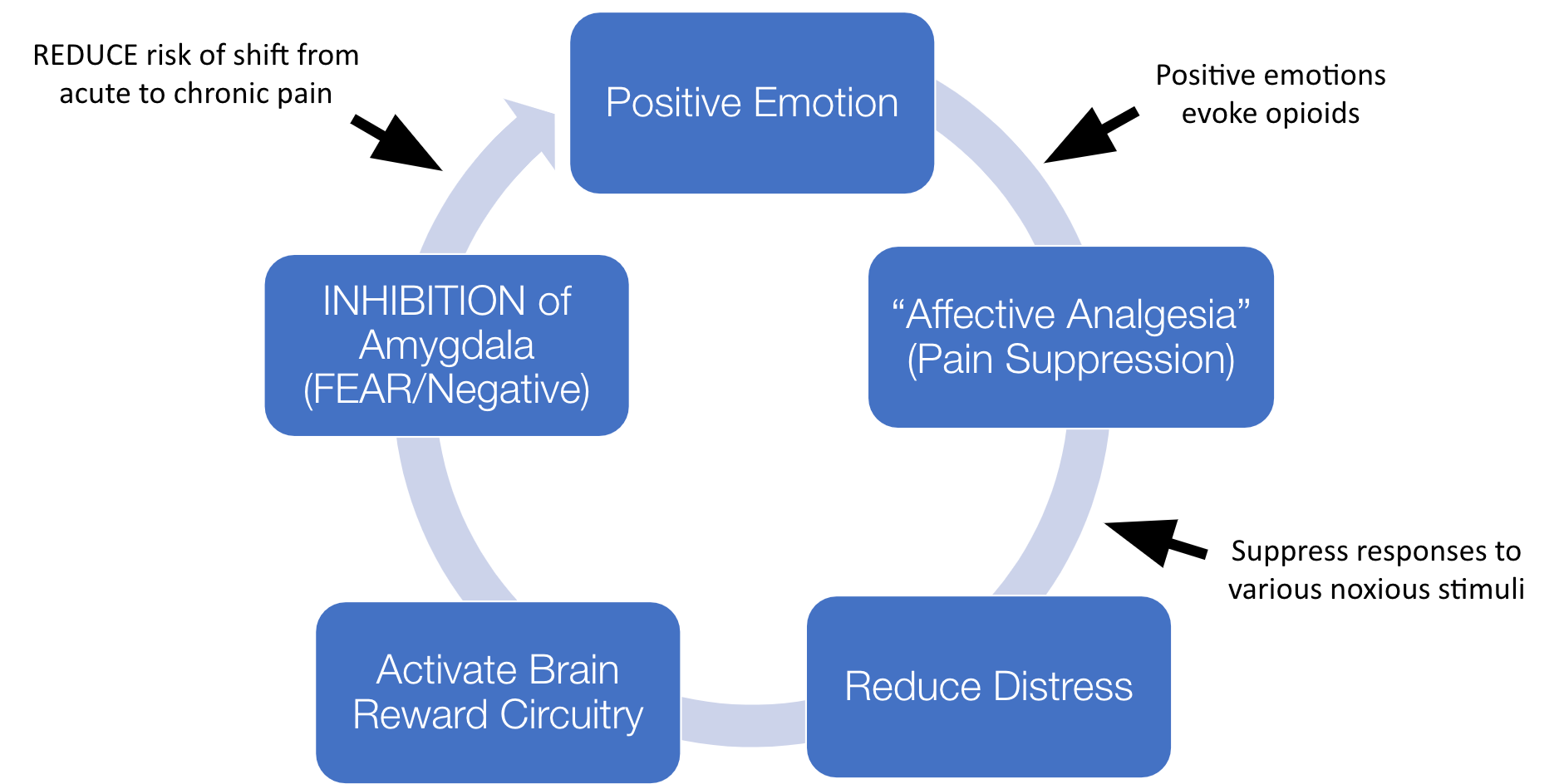

Pain Cycle

Figure 18. Pain cycle (Lumely et al., 2011; Franklin,1998).

Positive emotions evoke endogenous opioids. To do this, we want to reduce distress and activate reward circuitry. This inhibits the amygdala and the fear or negative response. This shift has been shown to reduce the risk of going from acute to chronic pain. We want to help our folks in an acute pain state have positive emotions and feel hopeful to change the neurophysiology.

A Tale of Two Clients

- Client 1

- Pelvic/sacral fractures

- History of Depression

- “I don’t like pain. I would have had another child.”

- “When is it going to go away?”

- Maladaptive coping strategies

- Difficulty with emotional regulation

- “I’m a baby” - negative self-talk

- HIGH LEVELS OF PAIN REPORTED

- Client 2

- Ankle fracture, fell x2 (including in the ED!), external fixator

- Prior wrist fracture

- Appreciating info-“I feel so much more confident!”

- Was due in Hawaii, “I’m going to get in shape after this and lose weight!”

- “You have to see this as an opportunity”

- LOW LEVELS OF PAIN REPORTED

I want to go over two clients. Client 1 had a history of depression, ongoing childhood trauma, and many maladaptive coping strategies. She reported high levels of pain. Client 2 loved talking about the pain science aspect. She loved the info as it made her "feel so much more confident." She felt empowered by understanding her body. She was supposed to be in Hawaii but had to cancel. "What am I going to do? I'm going to get in shape after this and lose weight. You have to see this as an opportunity." This is a great example of positive coping and reframing a situation. She reported low levels of pain. These are examples of acceptance and commitment therapy.

- Resistance=Pain

- Freedom=Acceptance

Resistance is pain, while freedom is acceptance. Think about a Chinese finger trap, as noted in Figure 19. When we resist and tighten, you cannot remove it. However, upon relaxing, it is easy to remove.

Figure 19. Chinese finger trap.

This is a great metaphor to use with clients.

Pacing for the Persisters

- “Start Easy, Build Slowly”~Louis Gifford

- Opportunity for guided pacing, self-management, and “sore but safe” zone

- Monitor client perception of performance

- Keep the “alarm system” coming down (decrease threat)

(Louw et al., 2018)

We also want to talk about pacing for the persisters. After an acute pain state, there is a reason for taking our time and using guided pacing. It encourages self-management to find the sore but safe zone. After you have surgery, tissues are healing. We would expect clients to have some pain. As such, we need to teach clients how to manage activities in the sore but safe zone. We want to give them a chance to monitor that and know their limits. "That's my body telling me it's time to pace and to take a break to try to keep that alarm system down."

Pain Acknowledgement Scale. A great way to think about this is using a pain intensity scale. Figure 20 shows the Pain Acknowledgment Scale.

Figure 20. Pain Acknowledgement Scale.

This can be helpful for somebody who is rehabbing after an injury or surgery. I did this recently with someone, and they said, "When I'm up and moving, I'm at a four or even a five. Once I start to feel it push past that five, I stop." This was their acceptable zone and their body telling them it was time to sit. It gave this person control. I also shared this with the physical therapist, so they also knew this person's acceptable zone.

We do not want to use many medications as this has gotten us into trouble in the past. Using a tool such as the pain scale can help people understand their safe zones when they are up and moving. This may need to be rephrased for individuals with persistent pain. Some people may be at an eight, nine, or a 10 all the time. This is not something that I would recommend using with somebody in that persistent pain state.

Graded Exposure (for the “Fear-Avoiders”)

- Visualization of Performance PRIOR (anticipation of pain > pain itself!)

- Facilitate & guide breathing with mobility

- Monitor avoidance behaviors

- Bracing

- Grimacing

- Guarding

- Directing attention away from thoughts and feelings

- Address beliefs regarding fear of the activity

- Guide through movement, re-address beliefs, encourage self-monitoring/management behaviors

(Vlaeyen, J. et al., 2018)

Graded exposure helps fear-avoiders visualize a performance. If they are afraid of moving, facilitating and guiding breathing during mobility can also help. Monitoring some of these behaviors can be helpful. Many people do not realize that they hold their breath and tighten up when they move. It can be helpful to talk them through breathing as they are engaging. We can integrate this into ADLs during things like showers and transfers. You can then reflect with them to see if it helped. For example, they may say, "I was able to relax and felt good about it. I did not have as much pain."

Interventions: Religion/Spirituality and Pain Experience

- Spiritual/religious triggered relaxation > secular relaxation practice (progressive muscle relaxation, non-religious meditation, etc.):

- Anxiety reduction

- Positive mood

- Closer to god

- Improved pain tolerance and coping with pain

- Increased control and self-efficacy

- Lower HR/BP

- Improved metabolism

- Enhanced autonomic stability during stress

- Altered endocrine response to stress

(Wacholtz & Pargament, 2005; O’Halloran et al., 1985; Weeneberg et al., 1997; Alexander et al., 1994; Carlson et al., 1988); Keefe et al., 2001)

We can use religion and spirituality to help our clients if that is a goal of theirs. We can encourage prayer or chaplain visits. The ability to engage in spiritual practices has been shown to reduce acute pain.

Interventions: Humor and Laughter

- Good for building rapport and empathy (mirror neurons: contagious smiling, laughter)

- Benefits of humor: diffuses tension, demonstrates friendliness, coping strategy, etc.

- Acting Happy-MAKES you happier!!! “Facial Feedback Hypothesis”

- Laughter:

- Exercises and relaxes muscles

- Improves respiration

- Stimulates circulation

- Decreases stress hormones

- Increases immune defenses

- Elevates pain threshold tolerance

- Enhances mental functioning

- Counteracts depression

- Elevates mood

- Self-esteem

- Hope

- Energy

- Improves interpersonal interaction, relationships, closeness, etc. increase friendliness, etc.

- Laughter + Pain-releases endorphins, decreases cortisol production, releases oxytocin, reduces pain via distraction!

(Mora-Ripoli, R., 2010; King, B., 2016; Strack et al., 1988; Struber et al., 2009)

Can we use joke books? Can we be silly? I have done silly things with adaptive equipment. Can we have them watch silly videos? All those different things can release endorphins, decrease cortisol or stress chemical production, and reduce pain. It also helps to distract them from the pain.

Interventions: Social Support

- Close Relationships as a Contributor to Chronic Pain Pathogenesis: Predicting Pain Etiology and Persistence (Woods, S. B., Priest, J.B., Kuhn, V., & Signs, T., 2019) Social Science and Medicine

- Relationship strain, relationship support, social integration, depression, anxiety, and pain severity predict chronic pain etiology and persistence over 10 years; specific associations for acute vs. chronic pain.

- The transition of acute pain at baseline to a chronic decade later statistically significantly linked to pain interference, family strain, and depression.

- Conclusion: “Family strain is an important part of the chronic stress profile associated with chronic pain etiology, whereas family support is associated with a reduced risk of acute pain transitioning to chronic pain over time.”

OT practitioners are very aware of the role of positive social engagement. This study found that a transition of acute pain at baseline to chronic pain decades later was statistically linked to pain interference, family strain, and depression. Facilitating positive social support and participation for our clients in the acute pain state helps us reduce the risk of that transition from acute to persistent pain.

Interventions: Sleep and Pain Interference

Sleep Disturbance

- Sleep disturbance = risk for new-onset cases of chronic pain in pain-free individuals

- Sleep disturbance worsens the prognosis for those suffering from persistent pain

- Better sleep = better prognosis

- Interruption of sleep - hyperalgesia - central sensitization

- Similar brain areas and effects with persistent pain & HPA Axis- Impaired emotional regulation, lowered pain thresholds, and need for protection!

- Client history of insomnia, sleep apnea, restless leg syndrome (may already have compromised sleep, affecting recovery/pain)

- Increased stress/anxiety, increased pain post-surgery, injury, etc., inflammation.

(Simpson et al., 2018; Irwin, et al., 2012; Smith et al., 2007)

Sleep and pain have been talked about a lot this week. If somebody is having an ongoing sleep disturbance around the time of that acute injury onset, this can heighten that inflammatory response and keep the elevated stress going.

Sleep as an ADL

- Sleep as an Activity of Daily Living and Improved Outcomes in Acute Care; Clore, K. Heidt, S., Meireles, J., Gappy, B., Higgy, B., Rasheed, Z., Scott, R., Vanini, G., Farrehi, P., Whitehouse Barber, M., Johnson, M., & David, C., 2016. American Journal of Occupational Therapy

- Conclusion: “Occupational therapy sleep tool intervention [sleep aides] demonstrate a positive effect on pain reduction associated with sleep deprivation. To improve patient outcomes, hospital-based occupational therapist roles should routinely include sleep education as part of their domain.”

This is a great article from the American Journal of Occupational Therapy. Sleep is an activity of daily living and showed improved outcomes in acute care. We can help with things like earplugs and working with the nursing staff on turning some alarms down. This can have a positive effect on pain reduction associated with sleep deprivation. We can also use relaxation techniques to promote sleep.

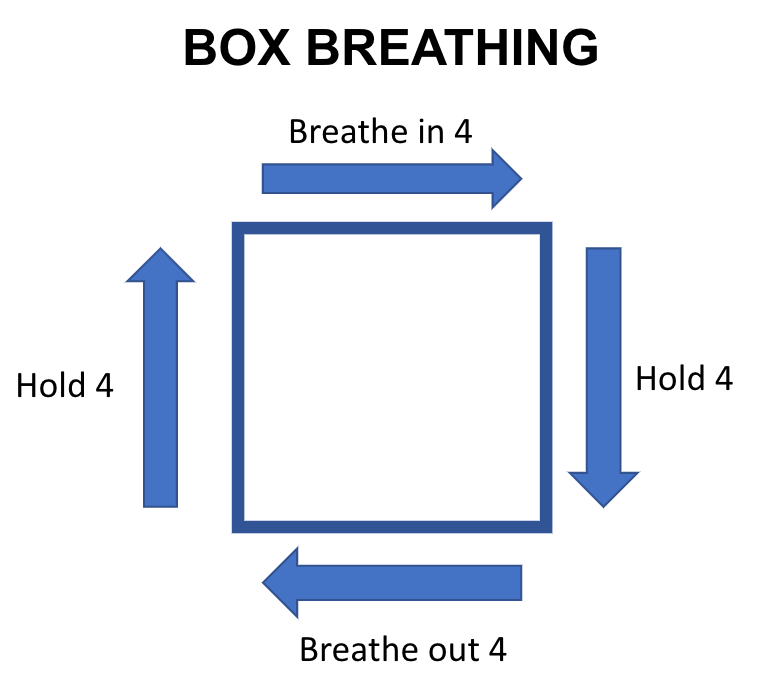

Interventions: Breathing

- 4-7-8 Breathing-Dr. Andrew Weil

- Breathe in Through Nose for 4 Counts…

- Hold Breath for 7 Counts…

- Exhale Through Mouth with –Whoosh- for 8 Counts…

- (May shorten lengths depending on ability level)

(Zaccaro et al., 2019)

Breathing can push the brake pedal on the sympathetic nervous system response and tap more into that parasympathetic nervous response. We can educate our clients on this technique. Before moving, we can say, "Let's do some deep breathing together and see how that changes how you are feeling. It might give you more control."

Figure 21. Breathing example.

Breathing can be an important coping strategy.

Interventions: Relaxation and Music

- Multiple Types (find what works best for the client):

- Progressive Muscle Relaxation

- Guided Imagery

- Simply Listening to Music or Music With Relaxing imagery (closed-circuit TV channel)

- Use of music hours after surgery = opioid reduction (Cepeda et al. 2006)

- YOUTUBE VIDEOS

- Teach versions that are longer (10-20 min, to be used in bed/for sleep hygiene)

- Teach versions that are shorter (60-90 sec, for active “in the moment” coping)

My health system has a TV channel dedicated to relaxing music and imagery. There are also different YouTube videos. You can make some of these suggestions part of your home program to facilitate self-management.

Interventions: Mindfulness

Mindfulness

- Mindfulness (neuroplastic brain changes, reverse HPA a