Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Pain and Symptom Management for the Allied Health Professional, presented by Susan Holmes-Walker, PhD, RN.

*Please also use the handout with this text course to supplement the material.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to list the four types of pain and descriptors related to each category.

- After this course, participants will be able to compare/contrast pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment options for patients experiencing pain to support participation in daily activities.

- After this course, participants will be able to identify 4 non-pharmacological multimodal options for patients experiencing pain.

Introduction

While healthcare providers only have a direct 20% impact on a person’s life expectancy, it’s critical to remember that the remaining 80% of factors that influence life expectancy happen outside the healthcare system. This highlights the importance of making every interaction count. Even though our time with patients is limited, the quality of care we provide and the resources we equip them with can have a lasting influence on their ability to manage their health and well-being in their daily lives.

Our role is to meet patients where they are, provide them with tools to manage pain and health challenges and empower them to take control of their health once they leave our care. The true challenge lies in acknowledging that most of what affects their health happens in their homes, communities, and everyday environments. That’s why our interventions must be effective during their time with us and sustainable and supportive of their long-term success outside the healthcare arena.

Pain Prevalence & The Neurobiology of Pain

I want to talk about pain prevalence data and provide a brief overview of the neurobiology of pain. While this isn’t a deep dive into biology, understanding a few key concepts about how pain functions in the body can improve our approach to managing it. When it comes to pain prevalence, the data is staggering.

Americans With Pain Versus Other Conditions

According to the American Academy of Pain Medicine, approximately 100 million people in the United States experience chronic pain. To put that in perspective, that’s far more than the 25 million people who have diabetes, the 18 million with some form of coronary heart disease, the 15 million who have experienced a stroke, and the roughly 8 million diagnosed with cancer.

It’s important to remember that individuals in these other categories often overlap with those experiencing chronic pain. For example, many patients with diabetes also suffer from diabetic neuropathy, a painful condition that contributes to chronic pain statistics. Similarly, people with coronary heart disease, high blood pressure, or a history of heart attacks often deal with chronic pain related to circulatory problems. Stroke survivors may also experience long-term pain as part of their recovery, and cancer patients frequently endure pain as a result of the disease itself or its treatment.

When we look at these numbers, it becomes clear that chronic pain is not an isolated condition. It often coexists with other health issues, creating a more complex scenario for patients and healthcare providers. Managing chronic pain alongside conditions like diabetes, heart disease, stroke, or cancer can be challenging, but understanding the interconnectedness of these conditions is key to offering comprehensive care.

Case Study: Post-Stroke Pain

As we progress through this presentation, we'll examine a focused case study involving a patient with post-stroke pain. Whether you've worked in acute care, ambulatory care, or another healthcare setting, you've likely encountered and treated patients who have experienced a stroke. This context will be important as we discuss our case study patient and explore the complexities of post-stroke pain.

Post-stroke pain is a common but often misunderstood symptom. Many practitioners may overlook it due to its variable characteristics, comorbid medical conditions, or the patient's cognition or communication impairments. Pain might not always seem like the primary issue during a healthcare interaction, so it can easily be missed. However, post-stroke pain can significantly affect a patient’s future quality of life, limiting their ability to fully engage in rehabilitation and slowing their recovery. This pain can create barriers, making it harder for patients to regain strength and participate fully in rehab services.

Another challenge is that post-stroke pain doesn’t always respond well to medication. Given the ongoing opioid epidemic, it’s especially important to consider non-medication options for managing pain. As we still see unfortunate consequences related to opioid use and abuse, exploring alternative treatments for post-stroke pain—and chronic pain in general—is crucial. We’ll delve into alternative pain management strategies later in the presentation, ensuring we provide options beyond traditional medication to help patients achieve better outcomes.

What Is Pain?

So, what exactly is pain? We all understand that pain is a complex process, but understanding that complexity helps us better select therapies tailored to each patient’s specific type of pain. How we understand and approach pain is crucial in determining which strategies will be most effective. When patients seek care, providing both relief and comfort is essential.

It’s important to consider that comfort can be a different lens through which to view pain. Often, patients might say they aren’t in pain, but they feel uncomfortable. This distinction can change how we address their needs. I recall an experience at Michigan Medicine in Ann Arbor, where I spent over 20 years in acute care. We had an acute pain service, and part of our routine was rounding on patients who were receiving post-operative pain management, often with pain pumps. One morning, we encountered a patient who appeared to be grimacing and visibly uncomfortable. We used the traditional pain scale—asking, “On a scale of 0 to 10, how would you rate your pain?” The patient responded, "I don’t have any pain."

However, as healthcare professionals, we rely on both what our patients tell us and what we observe. The patient’s verbal response didn’t match their facial expression. So, I asked, “Your face looks like you’re experiencing discomfort. How would you rate your discomfort rather than your pain?” This simple shift in wording changed the entire interaction. The patient replied, “Well, my discomfort is about a 9, but I wouldn’t call it pain.” From there, we could make the necessary adjustments to improve the patient's comfort.

This experience underscores the importance of context and language when addressing pain. If you’re working with someone who shows visible signs of distress—like grimacing or wincing—consider using the word “comfort” instead of always defaulting to “pain.” This approach can often lead to more accurate feedback and help us provide better care.

The key takeaway is that pain is subjective. As Margo McCaffrey, a renowned nursing researcher in pain management, famously said, “Pain is whatever the experiencing person says it is, existing whenever he or she says it does.” This means we must listen to and trust what our patients tell us. Regardless of our clinical perspectives or the diagnosis, if a patient says they are in pain, we must believe them and respond accordingly.

This leads us to understand the neurobiology of pain, which will further inform how we assess and manage it.

Pain Pathway

Let me clarify that this isn't a neurobiology class, and I don't claim to be an expert on the subject, but I want to share a bit about the pain pathway to help you understand how pain functions in the body. The pain pathway consists of four main steps:

- Transduction is the process by which tissue-damaging stimuli activate nerve endings, essentially turning the injury into a pain signal.

- Transmission involves relaying the pain message from the injury site to the brain through the nervous system.

- Recently discovered, modulation refers to neural processes that specifically reduce activity in the transmission system, thereby limiting the amount of pain signal that gets through.

- Perception is the final step, is complex, and includes several processes, such as attention, expectation, and interpretation, all of which shape how the brain perceives pain.

Now, as we continue to explore post-stroke pain, it’s important to understand that strokes can damage various parts of the brain and nervous system. If someone has experienced a stroke, especially one that affects neurological or cardiovascular systems, they may have impaired processing along this pain pathway. This means that pain signals might not be transmitted correctly from the injury site to the brain, or the brain might not interpret those signals as expected. Neurological damage can alter how patients perceive pain based on where the stroke occurred and the ongoing symptoms or impairments they experience.

Pain Receptors

Let’s talk more about pain receptors, specifically nociceptors, the specialized receptors that detect pain. Nociceptors play a central role in the complex mechanisms that form what the brain perceives as pain, responding to potentially harmful stimuli. These receptors act as predictors of harm, sending signals to the brain when they detect something that might cause damage. Their function and structure vary depending on the tissue they’re located in, whether it’s skin, organs, the pulmonary system, or the musculoskeletal system.

Nociceptors also play a crucial role in adaptive and protective responses. For example, when you hit your finger with a hammer, the nociceptors quickly relay a pain signal to the brain, prompting a behavioral response like pulling your hand away. The same process happens when you stub your toe—the nociceptors send a signal, and your body reacts instinctively. This shows how these receptors process pain and trigger immediate behavioral reactions to avoid further harm.

It is essential to remember that nociceptors are spread throughout the entire body. They exist in the skin, within our internal organs, in the pulmonary system, and throughout the musculoskeletal system. This means that pain can be experienced in any of these areas. The presence of nociceptors in such diverse tissues explains why we can feel pain in various ways—a sharp pain on the skin, deep internal pain, or musculoskeletal discomfort.

Understanding this widespread nature of nociceptors helps us appreciate how pain can manifest differently across the body and why managing pain often requires a nuanced and multi-faceted approach, particularly in cases of chronic or complex conditions.

Assessment Includes Assessing for Medication Side Effects

I also wanted to spend a little bit of time talking about medication side effects. Assessment for pain includes assessing for medication side effects. If you're working in acute care or any other setting, and the people you're treating are experiencing any pain, they will most likely be receiving some form of medication. Particularly in the acute stage of pain, they will probably be prescribed an opioid.

There are four main types of opioid receptors: mu, kappa, delta, and nociceptive. Each of these receptors plays a specific role in the way the body experiences and responds to opioids. It's important to understand these receptors to anticipate the effects of opioid medications and any potential side effects that patients might experience during treatment.

Mu Receptor Locations and Possible Side Effects

Mu receptors are located throughout the body, and opioid medications bind to these specific receptors, leading to various side effects depending on their location and function. Let’s look at where these mu receptors are located and the potential side effects to better understand this.

In the respiratory system, mu receptors can lead to a decreased respiratory rate. If you've worked in acute care, particularly with patients fresh out of surgery or following a procedure, you've likely observed this. Patients who have received higher doses of opioids or anesthesia may experience slowed breathing, which is directly related to the action of mu receptors in the respiratory system.

Mu receptors are also present in the gastrointestinal (GI) system, where they often cause nausea, vomiting, and constipation. These are some of the most frequently reported side effects by individuals taking opioids, as the activation of these receptors disrupts normal GI function.

In the cardiovascular system, opioids can lead to bradycardia (slower heart rate) and hypotension (low blood pressure) due to the presence of mu receptors. This effect is particularly important to consider, especially with the American Heart Association's recent updates to Basic Life Support (BLS) training, which now includes training on recognizing the signs of drug overdose. This highlights how opioid misuse or overuse can severely impact cardiovascular function.

In the central nervous system, mu receptor activation can cause dizziness and, in some cases, euphoria, which explains the potential for opioids to be addictive. Additionally, long-term opioid use, particularly at high doses, has been associated with sensorineural hearing loss. This hearing loss has been documented in some patients, affecting the central and peripheral auditory systems. The good news is that this type of hearing loss often resolves once opioid use is discontinued.

By understanding where these mu receptors are located and how they affect the body, we can better anticipate and manage the side effects associated with opioid use, ensuring safer and more effective pain management for our patients.

Case Study: Jane

Let’s begin our case study with Jane, a 65-year-old who had a stroke four months ago. She’s reporting worsening right shoulder pain, feeling “not like herself,” an upset stomach while taking opioid pain medication, and limited participation in therapy due to poorly controlled pain. Jane, who was very active before her stroke, has set a long-term goal to resume walking at the mall with her friends three days a week within the next three months. Social interaction with her friends greatly motivates her to complete therapy.

Case Study Question 1

Is Jane having opioid related side effects? Let’s think back to the slide on mu receptors, which are located in the respiratory system, GI system, cardiovascular system, central nervous system, and auditory system. Based on Jane’s symptoms, particularly her upset stomach, it seems highly likely she is experiencing side effects linked to opioid use.

Many of you responded "yes" to this question, and I see answers pointing to constipation, upset stomach, and nausea, which are all classic GI-related side effects of opioids due to the activation of mu receptors in the gastrointestinal system. If you’ve worked with patients in a clinical setting, you know that these digestive issues are common for those taking opioids. And for those of you who may have taken opioids yourself, you might be familiar with similar experiences.

Biopsychosocial Pain Assessment

As we move on, it’s important to emphasize the shift toward biopsychosocial pain assessments in healthcare. This comprehensive approach considers the physical aspects of pain and the psychological and social factors that contribute to a patient's experience. During that first interaction, healthcare professionals are responsible for conducting an initial assessment or evaluation to develop an appropriate treatment plan and determine if the patient qualifies for therapy services.

A comprehensive assessment is crucial because it captures the full scope of a patient’s pain experience. By incorporating physical, emotional, and social factors into the evaluation, we better understand how pain impacts the individual’s life. This approach allows us to tailor treatment strategies that address the pain and the underlying factors that may exacerbate or contribute to it.

The Biopsychosocial (BPS) Model of Pain

When we consider the biopsychosocial (BPS) model of pain, it becomes clear that pain is a dynamic interaction between biological, psychological, and social factors. This model emphasizes that pain isn’t just a result of physical injury, such as surgery, stubbing a toe, or a fracture. Over time, we've learned that pain also encompasses psychological and social dimensions, making it a more complex experience than purely physical symptoms.

Using this biopsychosocial approach allows us to create better strategies for addressing the pain patients present with and helps us understand the multiple factors contributing to their experience of pain. According to this model, the severity of pain is influenced not just by physical problems but by a combination of factors. If psychological or social challenges are present, they need to be considered when assessing and managing pain. A theory that doesn’t explore all three components—biological, psychological, and social—can’t fully explain why someone is experiencing pain.

To explain this further, when we think about biological factors, we focus on things like brain function, pain perception, inflammation, and the severity of illness. These physical aspects often come to mind when we think of pain.

Next, we have the psychological factors, which include mood, stress, and coping mechanisms. A patient’s ability to manage stress and their emotional state can greatly influence how they perceive and handle pain. Whether a person has positive or negative coping strategies can also play a major role in their pain experience.

Lastly, social factors include how pain impacts a person’s social life, similar to Jane's desire to return to walking with her friends. Social isolation, economic challenges, and even cultural considerations are all crucial aspects to consider. As a culturally diverse country, the US requires considering cultural backgrounds when determining appropriate pain management strategies. We must ensure our recommended interventions align with the patient's needs, preferences, and values. Otherwise, we risk offering solutions that don’t resonate with or are ineffective for the patient, leading to wasted resources and a failure to properly address their pain.

Ultimately, the biopsychosocial model encourages us to take a holistic view of pain, ensuring that we consider all facets of a person's life when developing treatment plans. By doing so, we can create more personalized and effective pain management strategies that truly meet the needs of each individual.

BPS Approach

With the BPS approach, pain management experts now recognize the strong relationship between pain and psychological health, acknowledging that these factors influence each other. The model suggests that the severity of pain is affected by much more than just physical symptoms, a point many patients have been expressing for years. It's a positive shift to see this more comprehensive model being accepted, as it allows us to better understand and address the non-physical dimensions of pain that patients often describe.

The BPS model emphasizes that any theory or approach to pain that does not incorporate biological, psychological, and social factors cannot fully explain why someone is experiencing pain. This is particularly important when considering chronic pain, which can significantly affect a person's quality of life. Chronic pain can interfere with everyday activities such as work, eating, and exercise, often diminishing the overall enjoyment. It can also lead to physical limitations, emotional distress, and social isolation, further compounding the challenges faced by the individual.

This comprehensive BPS approach to pain assessment and management is crucial, especially for patients dealing with multiple challenges in addition to their pain-related issues. By addressing all aspects of their experience—physical, emotional, and social—we can provide more effective, personalized care that helps improve their overall well-being.

Case Study Question 2

- Based on Jane’s history, what assessment questions might an allied health professional working with her ask during her initial assessment and evaluation?

When considering the biological, psychological, and social factors that influence her pain, we want to ask open-ended questions that prompt meaningful discussion, allowing us to gain deeper insight into her experience.

Some excellent suggestions are already coming in through the chat. For instance:

- "What have you stopped doing due to pain?" — This helps us understand how her pain has impacted her daily life and function.

- "How does your pain alter your ability to care for yourself or participate in activities?" — This question explores her ability to engage in self-care and meaningful activities.

- "What is your pain rating?" — A more direct but essential question to gauge her perception of pain severity.

- "What kind of home support do you have?" and "Is there any family involved?" — These questions dive into her social support system, which is crucial for recovery and ongoing care.

- "Have you had any lifestyle changes or sleeping issues recently?" — This addresses the psychological and behavioral impact of her pain.

- "What were your prior roles, rituals, and routines?" — Understanding her previous lifestyle gives us context for her rehabilitation goals, such as returning to social activities with friends.

What I appreciate about these responses is that they are open-ended questions, which is key. Open-ended questions encourage conversation and allow patients like Jane to share more about their pain experience beyond just a yes or no answer. For so long, we’ve often asked closed questions like, “Do you have pain?” or “How are you feeling today?” which can lead to surface-level responses like "yes" or "I'm fine." This misses the opportunity to explore the full scope of their challenges and what might be contributing to their pain.

By asking thoughtful, open-ended questions, we’re assessing Jane's pain and considering her as a whole person—her past routines, current challenges, and future goals. This holistic approach helps us tailor interventions that truly fit her needs.

Thank you for your contributions. Let’s continue to consider these issues as we work through the rest of her case.

BPS Focused Questions

Let me share a few examples of the questions we can ask Jane, considering biological, psychological, and social factors.

For a biological type of question, you might ask, "Tell me about your pain." This open-ended question allows Jane to express her experience, helping us gain insight into her brain function and how she perceives the pain.

A psychological question could be, "How do you feel the pain you are experiencing is impacting your life?" This allows her to explore the broader emotional and mental toll the pain is taking. I saw similar questions in the chat, which shows we’re all on the same page in addressing the psychological aspect.

When thinking about social factors, a question like, "How do health professionals respond when you talk about your pain?" can reveal whether Jane has had negative past experiences that might influence her current relationship with healthcare providers. As we know, there can be implicit bias and stereotyping in how pain is treated, so it’s important to understand if this has been a challenge for her. Additionally, you could ask, "What kind of support do you have as you work on improving your pain control?" This helps us understand her social network, including family and friends, who can assist her in managing her pain.

These questions aren't meant to be perfect; they are flexible based on your communication style and how you interact with patients.

Types of Pain:

Acute, Chronic, Acute on Chronic Pain, and High-Impact Chronic Pain

Now, we will transition to discussing the different types of pain. While most people are familiar with acute and chronic pain, there are a few other types I’d like to highlight. Understanding these can help you better grasp what patients, particularly those with chronic pain, are going through. When working with people experiencing pain, it’s essential to recognize the nuances of how pain is classified and experienced, as it can deeply impact their treatment and daily life.

Quick note: I use patients, people, and clients interchangeably during presentations, so I wanted to clarify that upfront. Let’s explore these types of pain and how they affect the individuals you work with.

Acute Pain

When we think about acute pain, it is generally a symptom of something wrong. It acts as a signal of a disease process and is often associated with tissue trauma. The cause is usually obvious. For example, if someone has a fracture, has fallen, or just had surgery, you can often use your visual observation skills to identify why they are in pain. You can connect the pain to a recent injury or procedure, making the cause quite apparent.

The key aspect of acute pain is that it should be managed efficiently and within the shortest possible time. Addressing it promptly helps ensure that it remains short-term, preventing it from progressing into long-term or chronic pain. Acute pain generally lasts less than three months.

Chronic/Persistent Pain

Now, when we think about chronic pain—often referred to in healthcare as persistent pain—it is more than just a symptom; it becomes a diagnosis in itself. Chronic pain tends to last longer than three months and often requires a different approach to management.

When we think of chronic pain as a diagnosis, it's helpful to compare it to conditions like diabetes or hypertension. Just as someone with these chronic conditions needs to manage them daily, chronic pain requires ongoing attention. Managing chronic pain becomes a part of the person’s everyday life. Unlike acute pain, chronic or persistent pain often serves no useful function, and this can sometimes create challenges in how we view or respond to it.

Unfortunately, when patients present with chronic pain without any obvious signs of trauma or injury, it's easy for biases or stereotypes to affect how we respond. Without a clear physical cause, we might be less empathic or even doubt the patient's experience. This is a common struggle for people living with chronic pain, as their pain is real, even if it’s not visible. As Margaret McCaffrey famously said, “Pain is what the person experiencing it says it is.” It’s essential that we conduct thorough assessments to understand and validate the patient’s pain experience. Chronic or persistent pain typically lasts longer than three months and requires a more nuanced approach to treatment and care.

Acute On Chronic Pain

The term acute on chronic pain refers to a situation where a person who is already living with chronic pain experiences a new, acute pain episode. I first learned about this concept from Dr. Paul Hilliard, whom I worked with at Michigan Medicine in the Department of Anesthesiology on the acute pain service. With his permission, I'm sharing this idea with you today.

Acute on chronic pain is exactly what it sounds like—someone who has a long-standing, well-managed chronic pain condition (such as chronic low back pain) suddenly experiences an acute pain event, like falling and breaking an ankle. In this case, you have to manage both the ongoing chronic pain while also addressing the new acute pain from the injury.

As Dr. Hilliard explained, opioids and anti-inflammatory medications are commonly effective for treating acute pain. However, it becomes more challenging when the patient is already on opioids for chronic pain management. There are important safety considerations in such cases when adding or adjusting medications to address the new pain. This is why it's crucial to explore other treatment options beyond opioids, such as anti-inflammatory medications, while carefully managing both pain types to ensure patient safety and effective pain relief.

Case Study Question 3

Jane's stroke occurred about four months ago, and she continues to experience pain. What type of pain is Jane experiencing? Overwhelmingly, everyone is saying chronic pain.

High-Impact Chronic Pain:

What You Need to Know…

Let's now take a closer look at high-impact chronic pain or HIC pain. This term was introduced around 2019 and focuses on pain, including disability and duration. It's a newly proposed concept that severely impacts a portion of the chronic pain population, though it remains largely uncharacterized at the population level.

When discussing high-impact chronic pain, it's important to note that it's not just about the severity of the pain itself but rather the limitations it imposes on a person's ability to participate in life and work activities. This type of pain is associated with a decreased quality of life, opioid dependence for some patients, and poor mental health. In terms of prevalence, about 7.4% of adults experience high-impact chronic pain, which is a significant number considering how it affects their ability to function and maintain mental well-being.

Some important facts about high-impact chronic pain are worth noting. For one, women tend to experience this type of pain more frequently than men. Unfortunately, research shows that women's symptoms aren't always taken as seriously as men's in certain medical contexts, which can complicate their pain management. Additionally, the prevalence of chronic pain and high-impact chronic pain increases with age, peaking among adults 65 and older.

Another factor to consider is the role of place of residence. Adults living in rural areas are more likely to experience chronic and high-impact chronic pain. While it’s essential to avoid stereotypes about rural living, the reality is that rural environments can pose challenges regarding access to healthcare and support. Limited access to care can make it harder for these individuals to find resources or treatments without facing logistical obstacles.

As we continue discussing pain management, it’s important to consider the type of pain patients experience and the broader challenges—such as access to care, social support, and the impact on daily life—that come with high-impact chronic pain.

Core Principles of Pain Management

We also want to ensure we understand the core principles of pain management. Chris Pacer worked with Margot McCaffrey, dedicating much of their careers to promoting better pain management through three key principles: quality assessment, acceptance, and action. These principles form the foundation for effective pain management, and we’ll discuss each in more detail in the next few slides.

Pain Assessment: Best Evidence/Quality Assessment

When we think about pain assessment, it's crucial that we use the best evidence available and choose the right words when screening for discomfort versus pain. If you remember the story I shared about the patient we rounded on during the acute pain service, we received a better response when we framed the conversation around discomfort instead of pain. Sometimes, our words can influence how patients communicate their experience, allowing us to better understand their pain and treat it appropriately.

It's also important to understand the specific words that describe different types of pain, whether emotional, neuropathic, or nociceptive. Knowing these distinctions can guide us in selecting the most suitable interventions. Additionally, we must be sensitive to cultural and gender differences, as responses to pain can vary depending on a person's cultural background or gender. Awareness of these differences ensures we approach each patient with the appropriate understanding and care.

Acceptance

The second key concept is acceptance. As we’ve discussed, pain is what the person experiencing it says it is, and as clinicians, we must accept the patient's report of pain. Some of the resources in this presentation may be older, but they are included because they’ve been foundational in guiding pain management strategies over the years. Even though they date back some time, they serve as benchmarks for approaching pain.

Acceptance also means recognizing that self-reporting is the gold standard. We must take their word for it if patients say they are in pain. Historically, vital signs like high blood pressure or increased respiratory rate were relied on to indicate pain. However, we’ve understood that looking at vital signs doesn’t always accurately reflect the patient’s pain experience. Instead, we must rely more on observing behaviors—watching for facial expressions like grimacing, noticing if the patient is splinting or guarding a limb, or observing whether they have difficulty coughing and deep breathing post-surgery. These behavioral cues are often more telling than vital signs alone.

Another important part of acceptance is reflecting on why we might find it difficult to believe someone is in pain. Unfortunately, in healthcare settings, we sometimes encounter patients who have struggled with opioid use or other social factors, and this can lead to jaded attitudes. It’s crucial to remain empathetic and avoid dismissing someone’s pain based on assumptions or biases.

I recall, early in my career in the 90s, at the University of Michigan Hospital in Ann Arbor, patients were often motivated to walk because they wanted to go outside and smoke. I would see patients lined up across the curb, pulling their IV poles, and smoking cigarettes. When they returned to their rooms, they often asked for pain medication. This created a challenging dynamic for nursing staff and others involved in their care, as it was sometimes difficult to empathize with their report of pain. But again, if someone says they are in pain, we must address it accordingly. This might mean adjusting dosages or exploring other treatment options. Even if their behavior seems contradictory, their pain is real to them, and it’s our responsibility to manage it with care and professionalism.

Action

The third core principle of pain management is action. Once we've accepted that the patient is experiencing pain, it's critical that we take appropriate action. The primary goal when a patient presents with pain is to prevent the transition from acute to persistent or chronic pain. If chronic pain already exists, it should be assessed separately from the acute issue, connecting back to the concept of acute on chronic pain.

A key aspect of action is reviewing pain-related orders and documentation. Effective communication is essential in a multidisciplinary team. Everyone involved in the patient’s care must clearly understand treatment plans, challenges, and any concerns that arise. By reviewing each other’s documentation and sharing experiences, the team can ensure a more coordinated and effective approach to managing the patient’s pain.

It’s also important to utilize both pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic interventions. In today's healthcare environment, patients often seek more than just medication—they also want to explore other treatment options. We'll discuss some of these alternative options later in the presentation. However, it's always critical to prioritize safety. In the past, there was a tendency to promise patients complete pain relief, which created unrealistic expectations. When full pain relief wasn't achieved, it often led to patient dissatisfaction and difficult conversations.

Now, we need to frame our conversations differently. It’s important to understand the type of pain the patient is experiencing and explain that complete pain relief might not be possible without sedation, which is not typically a desirable option. The goal should be to reduce pain to a manageable level so the patient can function effectively, take care of daily activities, and maintain their quality of life.

Respecting the patient’s preferences and motivations is also key. Many patients are informed about various pain management options, having done their own research. As healthcare professionals, we must stay educated on new interventions and be prepared to have informed, collaborative discussions with our patients. This helps build a comprehensive pain management plan incorporating the patient’s input and the healthcare provider’s expertise.

Categories of Pain

As we shift focus, let's discuss the categories of pain in addition to the types we’ve already covered (acute, chronic, acute on chronic, and high-impact chronic pain). Beyond the type, patients can experience pain that falls into different categories based on its source or nature.

Emotional pain is related to a person's mental state or condition. This type of pain can be chronic, especially for individuals living with long-term mental health conditions. Chronic emotional pain is something to consider, as it can significantly affect overall well-being.

Neuropathic pain results from nerve damage. For example, patients with diabetic neuropathy often experience chronic neuropathic pain. Other examples include phantom pain following an amputation or nerve damage after burns, like touching a hot iron. Additionally, patients who have had cardiovascular or neurovascular incidents, such as strokes, may also struggle with neuropathic pain.

Nociceptive pain is associated with the activation of nociceptors, which are the body's pain receptors. This type of pain is caused by tissue trauma, either expected or unexpected. Expected nociceptive pain occurs after surgery or a fracture, while unexpected trauma might result from events like a bike or motor vehicle accident. In either case, the trauma needs to be addressed as it triggers the body’s natural pain response.

Understanding these categories helps us tailor pain management strategies to the underlying cause and the specific experience of the patient.

Common Words Describing Pain and Distress*

When we consider these different categories of pain and ask our patients, "Tell me about your pain," or "How would you describe it?" there are some common words used to express different types of pain and distress.

Emotional Distress | Neuropathic Pain | Nociceptive Pain |

Frightening | Burning | Tender |

Punishing | Flashing | Sharp, cutting |

Vicious | Shooting | Dull |

Annoying | Stabbing | Cramping |

Nagging | Tingling | Squeezing |

Unbearable | Prickling | Throbbing |

For emotional pain, patients may describe it as frightening, punishing, vicious, annoying, nagging, or unbearable.

Neuropathic pain is often described as burning, flashing, shooting, stabbing, tingling, or prickling.

Nociceptive pain stems from tissue injury and can be described as tender, sharp, cutting, dull, cramping, squeezing, or throbbing.

These descriptions are drawn from Paul Arnstein's 2010 work, which I consider my go-to resource for pain management. While it hasn’t had a second edition, it still provides excellent guidance on effectively managing pain. It’s also important to remember that nociceptive pain is linked to our bodies' nociceptors, or pain receptors, that respond to painful stimuli.

These descriptive terms help us better understand our patient's pain and guide us in choosing the most appropriate interventions for their specific needs.

Case Study Question 4

We have another case study question. Jane visited her primary care physician and reported her shoulder pain as dull and tingling. She also mentioned that it is becoming more difficult for her to curl her hair and complete household tasks. Based on Jane's description of her pain as dull and tingling, what categories of pain is she likely experiencing?

The correct answer is neuropathic and nociceptive pain.

This case illustrates how someone can experience more than one category of pain simultaneously, such as neuropathic and nociceptive. This complexity highlights why pain is so challenging to manage and often requires multiple strategies—both pharmacological and non-pharmacological—to address it effectively. Many of you who are actively working with patients have likely encountered individuals who experience a mix of emotional, neuropathic, and nociceptive pain all at once, making it even more difficult to treat.

Neuropathic Pain in Aging Adults

I wanted to share some information about neuropathic pain, specifically in aging populations. As we know, the population in the United States is getting older, and I have additional slides that address pain in aging adults. Neuropathic pain, in particular, is common but often goes unrecognized. It affects 7 to 10% of older adults and is underreported, often due to cognitive impairment and other concurrent conditions. Older adults may experience nerve pain, but many attribute it to aging and might not report it.

My own father, who lived to 88, used to resist talking about his pain. He had severe arthritis and other health challenges, but he’d often say, "I’m just getting old; there's nothing anyone can do." He grimaced in pain but was adamant about not taking more medication and being strong-willed and tough. This mindset is common among older adults, who may feel pain is just part of aging, something they must accept. However, it’s important for us, as healthcare professionals, to remind our aging patients that there are options to manage pain that go beyond medication.

Continuing education and attending presentations like this one are valuable because they equip us with more information and resources to share with patients. Regarding neuropathic pain in aging adults, age-related biological and neurological changes can reduce the function of neurotransmitters, which can alter the way pain is recognized and managed. Additionally, neuropathic pain can result from chronic conditions that have a high prevalence as we age, such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and osteoarthritis. While not all older adults have these conditions, a significant percentage do, and these chronic diseases can contribute to neuropathic pain and other health challenges.

This highlights the importance of effectively understanding and addressing pain in our aging population.

PEG (Pain Rating, Enjoyment of Life, & General Activity) Pain Assessment Tool

This may be new information to you, but a PEG pain assessment tool has gained attention in recent years. It was created for use in primary care, where patient interactions are often time-limited. The goal was to provide primary care providers with a focused yet efficient way to assess patients dealing with chronic or high-impact chronic pain.

The PEG pain assessment tool covers three categories. The "P" stands for pain rating, the "E" represents enjoyment of life, and the "G" focuses on general activity. One important aspect of this tool is its measurement of pain intensity. The "P" is the typical 0 to 10 pain scale, asking how pain impacts the patient. But what's unique is the "E" and "G," which assess how pain affects the patient’s enjoyment of life and their ability to carry out general activities.

Chronic pain often creates barriers to living a fulfilling life. Many patients' pain-related goals are focused on improving their quality of life, similar to Jane's from our earlier case study. Her goal is to be social and walk with her friends, so understanding how pain affects her day-to-day activities is crucial. This tool offers a better way to quantify how chronic pain impacts activities of daily living and overall life satisfaction.

In primary care, where time with patients is often limited, the PEG tool provides a brief, straightforward, multidimensional measure that enhances chronic pain assessment in primary and ambulatory care settings.

PEG Scale

The PEG pain assessment scale is a simple three-item tool that asks three key questions.

The first question focuses on pain intensity: "What number best describes your pain on average?" This is the traditional 0 to 10 pain intensity scale, where zero represents no pain, and ten represents the worst possible pain. You ask the patient to reflect on their pain over the past week and provide a rating.

The second question addresses the "E" for enjoyment of life: "What number best describes how, during the past week, pain has interfered with your enjoyment of life?" Zero means pain has not interfered at all with the patient's enjoyment, while ten means it has completely interfered. This question explains how pain affects the patient's quality of life.

The third question concerns general activity, the "G": "What number best describes how, during the past week, pain has interfered with your general activity?" Again, zero means no interference with activities, and ten indicates complete interference. This question helps assess how pain impacts the patient's ability to carry out daily tasks and responsibilities.

To calculate the PEG score, you add the responses from all three questions and divide by three. For example, if we were assessing Jane and she rated her pain intensity as 6, her interference with enjoyment of life as 7, and her interference with general activity also as 7, her total score would be 6.7 (after adding the three numbers and dividing by three).

This method provides a more holistic view of how pain affects the patient, not only in terms of intensity but also in terms of its impact on their lives and daily activities.

Case Study Question 5

Here's our next case study question: Jane receives a referral from her primary care physician and presents for an outpatient physical therapy and occupational therapy evaluation. Would the PEG tool be a good tool to assess her pain? Why or why not?

Let’s take a few moments to gather your thoughts and responses in the chat. The PEG tool was created for primary care to efficiently measure pain across three categories: pain intensity, enjoyment of life, and general activity. But it might be worth considering even outside primary care, in ambulatory or acute care settings.

It looks like most responses are saying "yes." Some of the reasons include that it’s comprehensive, highlights functional limitations, helps create personalized goals, provides quantitative data, and allows us to understand how pain affects her life. I love these responses.

Imagine how a patient like Jane would feel if you approached her and said, "I’m going to evaluate your pain with a tool that will help me better understand not just the intensity but also how it impacts your life." For someone with chronic or high-impact chronic pain, who may have felt stereotyped or overlooked in the past, this kind of approach could change the dynamic of the patient-provider relationship entirely. It makes the assessment about them, their experience, and how pain affects their daily living. This empathetic approach could set a positive tone for the entire therapeutic relationship.

For those of you working in allied health, this might even be an opportunity to consider using the PEG tool in your practice. If you’re a student or working toward an advanced degree, it could make for a great evidence-based research project exploring how to incorporate the PEG tool into occupational or physical therapy settings.

Pain Catastrophizing

Let's take a moment to talk about the term "pain catastrophizing," which many of us are familiar with. This concept refers to negative and irrational thought patterns often seen in patients experiencing pain, and it tends to be characterized by three maladaptive dimensions: rumination, magnification, and helplessness.

Rumination refers to the constant, intrusive thoughts of "I can't get this pain out of my mind." Magnification makes the person worry and think, "I wonder what might happen." Helplessness makes the individual feel like, "There's nothing I can do." Together, these thoughts can create a vicious cycle, trapping the person in a loop where the pain feels overwhelming, and there seems to be no way out.

Patients experiencing all kinds of pain may fall into this cycle, and it can be especially tough for those with chronic pain. They might present with this psychological and emotional distress, unable to break free from these thoughts. Pain catastrophizing is a very real phenomenon, and we may even know people in our personal lives who experience this type of struggle with pain.

However, we must be cautious with this term. Patient reports often indicate problems with labeling someone as catastrophizing. This label can sometimes bias how healthcare providers view the patient's pain complaints, leading them to question the authenticity of the pain or even blame the individual for their condition. This creates an unhealthy dynamic where the patient may be asked, "Why can't you just stop thinking about it?" or "Why are you being so negative?"

For patients who have been misunderstood, overlooked, or whose pain has not been comprehensively assessed, these feelings of rumination, magnification, and helplessness can be heightened. They may feel trapped in a cycle of not being heard, and their pain isn't fully understood.

While there have been discussions about renaming the concept, simply changing the term won’t necessarily solve the core issues in assessing and treating pain. The real solution lies in improving our understanding of how pain impacts a person's life, ensuring that we avoid bias, and taking a comprehensive, empathetic approach to managing pain.

Concerns With the Term ‘Catastrophizing’

Concerns with the term "pain catastrophizing" arise because it overlooks some fundamental flaws in how pain is assessed and treated. We've already learned that quality pain assessment, acceptance, and action are essential when someone reports pain. However, healthcare professionals often receive inadequate training regarding pain assessment, which can lead to misunderstanding or mislabeling patients. When there’s a lack of understanding, it can sometimes be easier to blame the patient rather than address the gaps in knowledge.

Proper education and training on pain assessment and management are critical to address these concerns. Healthcare professionals should be equipped with the right psychological and assessment tools for clinical management, as pain is influenced by various factors beyond just the physical sensation. We also need to recognize the impact of gender equity and racism on pain assessment and avoid biases that might lead to unfair labeling of patients or dismissing their pain experiences. Being mindful of these issues is key to providing empathetic, effective care.

Words We Use

We also need to ensure that we address the underlying issues before assigning or creating new terms. While it’s common to introduce new terminology in healthcare, simply changing the name doesn't address the root of the problem. As mentioned earlier, a new label won’t solve the issue without truly understanding and addressing the causes.

The words we use matter. Whether we're referring to "catastrophizing," "pain," or "discomfort," it’s crucial that we choose terms our patients understand. It’s essential for patients to feel heard and know they are engaging with healthcare professionals who genuinely care about improving their pain management strategies. Effective communication helps build trust and ensures that patients feel supported as they work through their pain challenges.

Pain and Aging

As I mentioned earlier, I wanted to provide some insights on pain and aging, particularly because the population in the United States is getting older. By 2050, the number of people aged 65 and older is expected to double. This demographic shift brings important considerations for managing pain in the aging population.

Many people tend to view pain as a normal part of aging. I shared a personal story about my 88-year-old father, who, even though it was obvious he was in pain, resisted discussing it. He often dismissed my suggestions, despite all the knowledge and education I had acquired. Toward the end of his life, though, he became more open to different strategies and pain management options. One of the ways I helped him was by giving him massages while he was in the nursing home, which provided him some relief. This experience taught me that the approach we take when discussing pain management with older adults matters greatly. Listening to their concerns, rather than simply telling them what to do, is key to building trust and providing effective care.

Pain in older adults is often underreported due to the notion of "wear and tear." Many people believe that pain is just part of getting older, especially if they were athletic in their youth or had physically demanding jobs, such as those in blue-collar industries or healthcare professions. Over time, the stress on joints can lead to conditions like osteoarthritis, which increases pain.

Another important point to consider is that pain in older adults can be associated with accelerated cognitive decline. For those diagnosed with Alzheimer's or dementia, assessing pain can become particularly challenging. There are specialized pain assessment tools designed for individuals with cognitive impairments who may struggle to verbalize their pain, and it's important for healthcare providers to be aware of and utilize these tools when needed.

Chronic Pain and Aging

Chronic pain in aging populations is becoming an increasingly important public health issue due to the high number of older adults experiencing it. Chronic pain is highly prevalent in this group and is associated with poor functional outcomes. For example, individuals suffering from chronic pain may struggle with daily activities such as walking, carrying groceries, or navigating stairs. While these challenges can affect people of any age, they are particularly significant for older adults who want to maintain their independence and manage their pain effectively.

Chronic pain, regardless of its source, can lead to increased healthcare utilization, decreased physical capacity, and a diminished quality of life. This makes it crucial to address pain in aging adults, as unaddressed pain can severely affect their ability to remain active and engaged in daily activities. The rising prevalence of chronic pain among older Americans is concerning, with some considering it to be of epidemic proportions. As life expectancy increases, more conditions related to aging, such as chronic pain, will naturally become more prevalent.

Effectively managing chronic pain in older adults is essential for preserving their independence and quality of life, making it a priority for healthcare providers.

Common Types of Pain in Aging Populations

As we consider pain in aging populations, it’s important to recognize the different types of pain that tend to emerge as people grow older. Understanding the root cause of the pain—whether it's due to wear and tear, conditions like rheumatoid or osteoarthritis, or the result of a traumatic injury—helps us manage it more effectively. Knowing the origin of the pain allows us to tailor treatment approaches accordingly.

Some of the most common types of pain in older adults include joint pain, back pain, neck pain, headaches or migraines, and facial or jaw pain. These types of pain are frequently encountered when working with aging patients and provide insight into the areas we may need to focus on in their treatment and care plans. Recognizing these patterns helps us anticipate the needs of our aging patients and offer better support for their pain management.

Managing Expectations for Pain Control

One important aspect of pain control is managing expectations. Our patients have expectations, and we, as healthcare providers, have expectations of them. If these expectations don’t align, it can create challenges in managing pain effectively.

Patient Expectations/Goals

When working with patients on pain management, I understand that their past experiences significantly shape their expectations and goals. For instance, when conducting a pain assessment with someone like Jane, I know how important it is to ask open-ended questions. If Jane has had a negative experience in the past with a healthcare professional, that could be a powerful contributor to her current perception of care. If she feels that her pain wasn’t taken seriously before, that will likely affect how she engages with me or any other healthcare provider moving forward.

I prioritize using open-ended questions and incorporating strategies that allow patients to express themselves fully. In Jane’s case, her goal of walking at the mall with her friends three days a week within three months is a great example of a SMART goal—specific, measurable, actionable, realistic, and time-bound. By collaborating with Jane, I can assess her pain condition thoroughly and help her achieve that goal through tailored interventions.

I also remind myself that comparison is the thief of joy, not only for me but for my patients as well. I’m mindful not to compare Jane’s progress or pain experience to another patient with a similar diagnosis because everyone’s pain journey is different. The biopsychosocial nature of pain means each person brings their own unique factors to the table, and I need to respect that.

Most importantly, I recognize that patients want to feel heard. Even if I can’t change things immediately, the act of listening and validating their experience is crucial. In my practice, I strive to ensure that patients like Jane know they are truly being listened to, which is often one of the most impactful parts of care, especially when dealing with pain or any other healthcare challenge.

Health Care Professional Expectations

It's essential that we, as healthcare professionals, focus on helping our patients improve their adherence to treatment plans to achieve their goals. Adherence, as opposed to the outdated term "compliance," reflects a more collaborative and patient-centered approach, where our role is to support and guide patients in adhering to their therapies and treatments. To do this effectively, we must provide patients with the necessary tools and resources.

One key strategy is ensuring patients have the right information. Many patients come to us after doing their own research, consulting Dr. Google, or talking to friends who have had similar experiences. It’s our responsibility to verify that they have accurate information about their condition and treatment options. If they are interested in exploring a new therapy or intervention they've heard about, we need to ensure they fully understand how it works and what’s required to adhere to it successfully.

Another important factor is fostering belief and motivation in their treatment plan. For any pain management strategy to be successful, it must be something the patient feels confident in and motivated to follow. We should ensure that the plan is not too complex or burdensome—something with too many steps or requirements may discourage adherence. By keeping things simple and ensuring that the treatment fits naturally into their daily routine, we empower patients to take control of their health outside the clinic. After all, the majority of factors affecting their health outcomes occur outside the healthcare system.

Lastly, we must assist patients in overcoming practical barriers. This might involve addressing cost concerns or ensuring that the treatment plan is feasible, given the patient's living situation. For example, if someone lives alone, it wouldn't be practical to design a treatment that requires the help of another person to use a device. Our goal is to develop treatment strategies that are not only effective but also realistic for each patient’s unique circumstances. By being mindful of these barriers and working together with patients, we can help them adhere to their treatment plans and improve their long-term health outcomes.

Stroke Example

Case Study Question 6

Jane's goal to resume walking at the mall with her girlfriends three days a week within three months is a SMART goal. It checks all the boxes: it’s Specific (walking at the mall with friends), Measurable (three days a week), Achievable (based on Jane's current abilities and the timeline), Realistic (considering her motivation and health), and Time-bound (within three months). This is exactly the goal we strive to help our patients set because it gives clear direction while remaining practical and focused on something meaningful to them. I see a lot of agreement in the chat. Let's dig into this a little deeper.

Stroke Care SMART Goal: Strengthen Muscles and Joints

When considering stroke care, especially for someone like Jane, who is post-stroke and has been experiencing pain for about four months, setting SMART goals for muscle and joint strengthening is a practical and structured approach. Here's how we can break down these goals:

- Specific: “I will work with therapists to strengthen my muscles and joints.” This gives a clear focus on the area of concern—muscle and joint strengthening—and emphasizes collaboration with healthcare providers.

- Measurable: “I will perform at least one exercise that improves my range of motion and mobility.” This allows Jane and her therapists to track progress through specific exercises to improve mobility.

- Attainable: “I will complete my exercises three times a week.” This realistic commitment aligns with her capabilities and ensures consistency without overwhelming her.

- Relevant/Realistic: “I will strengthen my muscles and joints.” This goal is relevant to Jane's post-stroke recovery because it ties directly to her rehabilitation needs.

- Time-based: “I will reach my goal within four months.” This provides a concrete timeframe for Jane to work toward, keeping her focused and motivated.

By aligning her recovery goals with these SMART criteria, Jane will have a structured and achievable pathway to improving her strength, range of motion, and overall mobility following her stroke. These goals ensure that her therapy is targeted and that progress can be clearly measured and celebrated along the way.

Complex Pain Management: How Did We Get Here?

We've discussed complex pain management, emphasizing that pain is complex and defined by the patient—it’s what the patient says it is. There are different sources and causes of pain and various factors that impact pain.

Reminder: Post-stroke Pain

As a reminder, post-stroke pain is a common symptom, but it’s often poorly understood by many practitioners. Its variable characteristics make it easy to overlook, yet it can significantly impact a patient's future quality of life. In addition to post-stroke pain, many patients are also managing pre-existing comorbidities, such as diabetes, kidney disease, or hypertension.

Therefore, when assessing pain in post-stroke patients, it's important to not only focus on the stroke-related pain but also consider these other comorbidities that may require attention. As we evaluate patients who come to us with painful conditions, it's critical that our therapy recommendations and treatment plans address the full scope of their health needs.

Individualized Multimodal Pain Management

We have to keep in mind an individualized multimodal pain management plan. The term "multimodal" has been around for years, but I wanted to give you a little background.

Multimodal Pain Management

Just as a refresher, multimodal pain management involves using multiple lower-risk therapies to decrease exposure to higher-risk treatments. For example, you don't always have to use opioids. It's important to remain open to offering non-opioid or non-medication treatments to patients.

Multimodal pain management is also a balanced, evidence-informed approach to pain management. It can be used for mild to moderate pain treatment and should begin with simple, lower-risk approaches first. You don’t want to start with the highest dose of opioids or medications right away. By starting with a lower-risk approach, you leave room to escalate to opioids or other pharmacological interventions if pain persists.

Additionally, it’s important to understand that pain control isn’t about using just one treatment to achieve the desired outcome. Often, a combination of treatments is necessary. Multimodal pain management is an individualized, dynamic process based on shared values and achievable goals. It focuses on using a combination of therapies that work well for that specific patient to manage their pain.

These therapies can include medications, non-medication options, or a variety of other strategies. The key is finding a combination that aligns with the patient's goals and preferences while ensuring they are motivated to stick to and implement the plan independently.

Factors to Consider

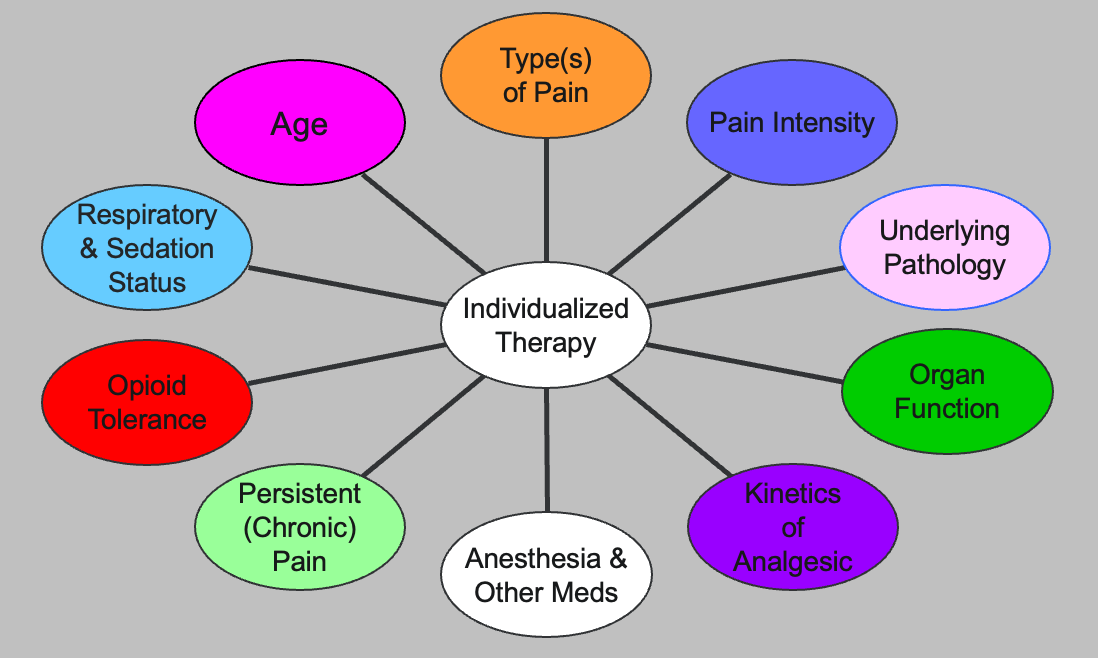

Here are some factors to consider in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Factors in multimodal pain management (Click here to enlarge this image.).

There are many factors to consider when developing a pain treatment plan. This graphic, from Chris Pacer, a nursing researcher I mentioned earlier, helps visualize the complexity involved in individualized therapy for patients. We're not going to dive into every detail, but it reminds us of the multiple factors at play.

We’ve already covered some key areas: the types of pain (as represented in the orange box), persistent or chronic pain (in the light green box), organ function, and the mu receptors and their role. We've also talked about measuring pain intensity, like with the PEG scale.

We can effectively address these various factors by using proper assessment tools and conducting comprehensive biopsychosocial assessments. It's equally important to actively listen to our patients and consider their input, ensuring that all these elements are considered when creating their pain management plan.

Pharmacological Pain Management

First, we will spend some time discussing pharmacological pain management, as for many years, it has been considered the gold standard and the most effective pain treatment.

US Opioid Dispensing Rates

We're now learning that overprescribing opioids and sometimes prescribing them when they weren’t necessarily needed has contributed to challenges in our communities. I wanted to share this graphic which shows how prescribing practices have changed from 2006 to 2020.

The darker shades of orange and red indicate higher prescribing levels, while the lighter shades represent lower levels.

As the slide transitions, you’ll see that in 2006, there was much more orange and red, reflecting higher opioid prescribing rates. By 2020, the map shows a significant decrease in those colors, indicating a reduction in prescriptions. This shift occurred in response to the increase in opioid overdoses and misuse, which heavily impacted communities. As a result, the federal government stepped in, requiring states to implement strategies to address opioid prescribing and the broader crisis of substance misuse.

Here is an updated link to the dispensing rates in the US of opioids.

2022 CDC Guidelines for Prescribing Opioids for Pain

In 2022, the CDC updated its guidelines for prescribing opioids for pain. Some of these updates are included in the slides I’m sharing, and I hope you’ll download them for future reference. The updates include significant shifts in how we approach pain management. One key point is that non-opioid therapies are at least as effective as opioids for many common types of acute pain. This means that even for acute pain, opioids aren’t always necessary, and non-opioid therapies are preferred for subacute and chronic pain.

Another important update emphasizes prescribing the lowest effective dose when opioids are initiated, especially for opioid-naive patients. If a patient hasn’t had much exposure to opioids, starting with a lower dose, such as 2 or 3 milligrams instead of 20, is crucial to avoid unnecessary risks since these patients haven’t developed tolerance or familiarity with metabolizing these medications.

The guidelines also stress prescribing only the quantity of opioids needed for the expected duration of pain. You may have heard patients or people in your social circles mention that they received fewer pills than they expected after surgery. Years ago, it was common to prescribe 30 or 40 pills when only 10 might have been needed. This led to excess opioids in the community, which were often misused. The updated guidelines aim to reduce this surplus and its associated risks.

Lastly, the CDC emphasizes the need to evaluate the benefits and risks of opioid therapy within one to four weeks of starting treatment. Previously, patients were sometimes left with large prescriptions and wouldn’t see their provider again for six, eight, or even twelve weeks, if at all. Now, clinicians must promptly follow up with their patients to assess for side effects, misuse potential, and overall effectiveness. This shift helps increase accountability for prescribers and improves patient safety by ensuring ongoing monitoring and evaluation.

Low-Risk Medications

When we think about pharmacological pain management, there are several low-risk medication options available to manage pain. These medications often don’t require a provider’s order, but it’s important to remember that any medication, even over-the-counter, should always be discussed with a primary care provider—whether that’s an MD, DO, PA, or nurse practitioner. This ensures transparency and avoids potential interactions with other medications a patient may be taking for other conditions. Keeping the provider informed is crucial for safety.

Using low-risk medications also allows the individual experiencing pain to have more control over their treatment. When patients can independently manage their pain—following the medication’s recommended usage—they gain a sense of autonomy. It’s important that patients use these medications as directed to prevent misuse, but the ability to manage their own treatment can help empower them in their care.

Lastly, we must always consider comorbidities and other medications a patient is currently taking. Even with low-risk medications, there’s a potential for drug interactions that could cause harm. This reinforces the importance of ensuring patients consult their healthcare provider to avoid complications when introducing new medications.

Low-Risk Medication Options

I wanted to bring some low-risk medication options to your attention, including topical medications and Tylenol.

Topical medications, such as Bengay, are familiar to many, but there are now various formulations that can be effective for managing pain. The advantage of topicals is that they are applied directly to the skin, not taken orally, so they don’t pass through the organs or require systemic metabolism. This reduces the risk of the side effects commonly associated with oral medications. While there are mu receptors in the skin, topical medications typically don’t trigger the same systemic effects as opioids, although they may not reach deep tissue pain effectively. However, topical medications can be helpful for issues like inflammation, soreness, or joint stiffness.

It’s important to remind patients to wash their hands after applying these medications and to observe their skin for any signs of irritation, such as redness, swelling, hives, or itching. These could indicate an allergic reaction, so they should stop using the product. To ensure safe use, patients should follow the package inserts' directions when using topical medication.

Tylenol (acetaminophen) is another low-risk option, though it may not always be highly effective for all types of pain. It’s still widely used but should be used cautiously for patients with liver or kidney disease. We advise patients not to exceed 3,000 milligrams daily, as exceeding this dose can cause liver damage. Additionally, if a patient consumes alcohol daily, Tylenol should be used very cautiously due to its liver metabolism to prevent unforeseen complications.

Ototoxic Medications: Common Categories

Another point I wanted to address, especially when we previously talked about mu receptors, is the potential for sensorineural hearing loss, which can sometimes occur with certain medications. I’ve previously presented this topic to audiology professionals, and I thought it would be important to bring it up here as well.

Many medications, not just pain medications, have ototoxic effects. For example, patients taking opioids, Tylenol, or aspirin (though less commonly prescribed now for cardiovascular issues), could experience hearing issues. Additionally, cancer treatments, particularly certain oral agents, can have ototoxic effects, as can medications for high blood pressure or even erectile dysfunction drugs.

It’s crucial to be aware that many different categories of medications can impact hearing. While we’re not pharmacists, this is something to consider if a patient reports sudden hearing loss or changes—especially if they manage multiple comorbidities and take various medications. This is an important factor to keep in mind, as it could be related to their medication regimen, and it is just an extra tidbit of information I wanted to share with you.

Case Study Question 7

When considering Jane's interest in low-risk medication options for her shoulder pain, what would you recommend and why? I recommend starting with topical medications, such as Biofreeze or other similar over-the-counter topical treatments. These can help manage inflammation, soreness, and joint stiffness without the systemic side effects that oral medications might cause. The benefit of topicals is that they don't pass through the liver or kidneys, making them a safer option, especially if Jane has other comorbidities.

The RICE method—rest, ice, compression, and elevation—can also be a low-risk, effective strategy to manage her shoulder pain. Ice, in particular, can help reduce inflammation and provide relief. Heat might also be useful depending on whether her pain is more related to muscle tightness or stiffness.

While these are safe, non-invasive options, it's always important to remind Jane to check with her primary care provider before using any oral medications. It's great to have a few low-risk options for her to try, but keeping her provider informed will ensure that there's no conflict with her overall treatment plan.

Cannabidiol (CBD) and Pain

I want to take a moment to discuss CBD and its use in pain management, as it’s a topic we can't avoid, given the growing interest in its application for various conditions, from migraines to chronic pain. It’s important that we inform ourselves enough to have an educated conversation with our patients about CBD, even though federal and state laws differ on the legalization of medical marijuana and CBD products.

With the increased effort to reduce opioid use, the legalization of CBD products has sparked considerable interest in clinical practice and research. As a member of the American Society for Pain Management Nursing, I've seen ongoing research about CBD's role in pain management. It’s crucial that we continue these research efforts to provide reliable, evidence-based information to our patients.

Results on the efficacy of CBD have been mixed. With so many CBD dispensaries and products available, the effectiveness of these products can vary based on the different formulations and concentrations of CBD. There's inconsistency in labeling, which raises safety concerns, especially for older adults. I’ve heard of situations where someone’s relative gave them a CBD gummy to help with sleep, which is concerning if people aren’t fully informed about what they’re taking.

As healthcare professionals, we must be aware that patients are turning to these alternatives, especially those suffering for a long time without relief from traditional treatments. When patients ask, “What do you think about CBD and pain?” it’s important to give an educated response. While we need more federal oversight and research on CBD’s safety and efficacy, my general advice to patients is to always consult with their healthcare provider first. I remind them that there have been known benefits for certain health conditions, but ensuring that CBD is appropriate for their specific situation is critical. I also emphasize that not all CBD products are the same, and different concentrations can produce varying results.

By encouraging caution and research, we can help patients make more informed decisions about whether CBD might be a viable option for them while also ensuring their safety.

Polypharmacy

I also want to address polypharmacy, which is especially prevalent among older adults but can affect anyone with multiple medical conditions. We need to be mindful that many people are taking various medications to manage their health, and polypharmacy can lead to negative outcomes. There is a higher likelihood of adverse drug reactions, which is why we should encourage our patients to consult with a pharmacist or their primary care provider when considering additional medications for managing pain.

Polypharmacy can increase the risk of hospitalizations, falls, and, unfortunately, even deaths. It can also reduce adherence to medication regimens, as patients may struggle to track what each medication is for, especially if they have to take different ones at varying times throughout the day. The burden of managing multiple medications—one twice a day, another three times a day, some in the morning and others at night—can be overwhelming for patients.

As healthcare professionals, we must support our patients by helping them navigate these complex medication schedules. Additionally, we should encourage them to have open conversations with their primary care provider or pharmacist about whether changes to their medication regimen are possible. They may be able to simplify their treatment plan, reduce the risk of drug interactions, and possibly decrease costs. By fostering these transparent discussions, we can help our patients manage their health more safely and effectively.

Deprescribing