Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Supporting Clients With MS: Presentation And Management, presented by Amber L. Ward, MS, OTR/L, BCPR, ATP/SMS, FAOTA.

*Please also use the handout with this text course to supplement the material.

Learning Outcomes

After the course, participants will be able to:

- Evaluate between the medication/research options and implications with exercise and function for clients with MS.

- Evaluate 3 options for client management with desired occupations.

- Evaluate common occupational therapy adaptations for appropriate use with clients with MS.

Introduction

I have been an occupational therapist for a considerable time and have worked at this clinic for twenty-two years, which has provided me with a wealth of knowledge to share. My experience spans from the historical context of our practice to the brand-spanking-new developments that keep us all up to date. Today, we will address medication research options and their specific implications for exercise function in clients with Multiple Sclerosis. Additionally, we will assess three options for client management, focusing on desired occupations, and examine common occupational therapy adaptations to ensure their appropriate use. As this is an advanced course, I felt that exploring and extending beyond the standard information would be the most beneficial approach for us.

Multiple Sclerosis (MS)

To begin, we need to start with a few definitions and some foundational information about MS. It is safe to assume that you wouldn't be here if you didn't know that MS stands for multiple sclerosis. It is an autoimmune disease that affects the central nervous system, and currently, the medical community still does not know the exact cause. There are various theories regarding the cause of this phenomenon, and we will explore several of them as we proceed.

Essentially, the immune system attacks the myelin sheath. This sheath helps neurotransmitters move more efficiently and enables effective work. When the myelin itself starts to degrade, it ends up injuring the axons. The oligodendrocytes essentially function to maintain the myelin and neurotransmitters, so demyelination occurs throughout this process.

In this situation, the immune system activates T cells, which are crucial for the immune response and are constantly at work. For example, if I smash my finger, the T cells come to the site to cause inflammation, resulting in swelling and redness. They activate B cells to initiate other responses, but when they are active when they are not supposed to be, it causes excessive inflammation. This damage leaves behind scarring as it occurs. Those scars in the central nervous system are known as sclerosis, which is where we get the name multiple sclerosis. You might also hear the words 'plaques' or 'lesions' used to describe the damage caused by this MS process. This damage significantly impedes transmission; without the myelin and the axons working effectively, it is like trying to hold up a tin can with a string to talk to someone four streets over instead of using a smartphone.

Epidemiology

Multiple sclerosis is significantly more common in women, with a diagnosis ratio of approximately two to one compared to men. While the most common age of onset is between 20 and 50, MS can also impact children and older adults. One of the primary issues for individuals over 50 is that, as we age, the increased prevalence of other chronic diseases can complicate matters. A clinician might mistake symptoms for a stroke or various other conditions, which makes reaching an accurate diagnosis that much harder.

Regarding heredity, about 15% of people with MS have a genetic component. We are going to discuss what the genetics really show and how specific individuals are more vulnerable. Statistically, the disease is more prevalent in higher latitudes and among Caucasians of Northern European descent. While it affects every nationality and race worldwide, the data reveals a higher concentration in that specific demographic. There are many theories as to why this is the case—why it affects more women and why it is more common in folks who are Caucasian—and we will explore those factors as we move forward.

Diagnosis (McDonald Criteria, 2024)

We will discuss some of the theories related to diagnosis. There is a specific set of requirements called the McDonald criteria, which was just revised last year. While it includes a whole slew of details, I believe the most important parts for us to understand as practitioners are that physicians must identify at least four areas of lesions, plaques, or sclerosis damage within the brain, spinal cord, and optic nerve. Furthermore, there has to be evidence of not just old lesions, but new lesions occurring at least thirty days apart.

The goal here is to rule out damage caused by a stroke or a similar "one and done" event, as opposed to something like MS that is potentially continuing to change. When examining lesions on an MRI, doctors can observe a feature known as the central vein sign, which indicates inflammation within those specific areas. It is just one more indicator they look for in the imaging. While there are other technical aspects to the criteria, these are the pieces that make the most sense for those of us who are not physicians.

Additionally, when analyzing cerebrospinal fluid, there are specific markers they look for to aid in diagnosis. The process requires them to exclude literally every other possibility first. Finally, a person must have experienced MS-like symptoms for more than twenty-four hours. In many cases, if someone has a TIA, or a transient ischemic attack, those symptoms are going to resolve relatively quickly. For MS, that initial hit typically lasts a bit longer.

Disease Course (NMSS, 2025)

There used to be four primary ways to categorize the disease, and while there are still four main types, there are a couple of other ways people might be identified. The first is Clinically Isolated Syndrome. This occurs when a person experiences a single symptom or attack, but the MRI only reveals damage in that specific area. Remember, a formal diagnosis of MS requires lesions in multiple places, so this remains an isolated issue that may or may not eventually develop into MS. It is often suspected to be the initial attack, but it is not yet sufficient to confirm the diagnosis.

The second type is Relapsing-Remitting, which is the most common, affecting about 85% of people. This typically starts with an acute attack that causes a decline in function, followed by a period during which the individual comes close to either a full recovery or a partial recovery. Some people get 100% back to their baseline after a relapse, while others do not and find themselves slipping a little bit further each time.

Next is Secondary Progressive MS. This can only happen after a person has already lived with the Relapsing-Remitting type for a period of time. That timeframe varies, but basically, the up-and-down nature of the relapses eventually smooths out and turns into a steady downward slope. It is vital to have an MS specialist track this progression. We are going to discuss the various disease-modifying therapies available, and a significant goal of those medications is to push out the time it takes for Relapsing-Remitting to turn into Secondary Progressive. In most cases, it does eventually transition; it is just a matter of how long that takes.

There is also Primary Progressive MS, which affects a relatively small number of people. This form is progressive from the very beginning. These individuals don't experience an attack followed by a remission; instead, they have a slope, whether steep or gradual, from the start. There isn't really a recovery phase or much of a remission. This tends to happen more often in people over the age of 40, or even those diagnosed over 50.

The last category is Radiologically Isolated Syndrome. This is when someone has an MRI for a different reason, like for migraines or other strange symptoms, and the scan reveals damage that looks like MS lesions or plaques. This damage seems distinct from stroke or brain injury. However, the person has no symptoms and no memory of ever having MS-type symptoms. We don't know if this will become MS or if the person will ever develop symptoms. It is possible they had an autoimmune process that halted. Because very few people get random MRIs, the number of people with this process occurring before symptoms appear may actually be greater than we think.

Prognosis

Regarding prognosis, it is undoubtedly true that the earlier we can administer these disease-modifying therapies to a person, the better. We are trying to protect the myelin, the axon, and the oligodendrocytes. Our primary goal is to avoid that transition into the secondary progressive stage. That is really what most of the drugs are all about. These medications do not stop MS itself because we do not actually know what causes MS in general. There are many assumptions and thoughts, but like several other disorders, such as ALS, until they truly understand the cause, it is tough to pinpoint how to stop it or prevent it from happening in the first place.

Individuals who experience a shorter time before transitioning to secondary progressive MS tend to be males, those who were at an older age at disease onset, and people who have a higher number of early relapses. Some individuals have one relapse, receive a diagnosis because the lesions are visible, perhaps have one more, and then things stabilize for years and years. However, for those who experience more frequent relapses at the beginning, there is a higher probability of more progression and a shorter timeframe before reaching that secondary progressive stage.

Disease Modifying Options- 20+

There are over 20 disease-modifying options, which is a very positive development for our clients because it increases the hope of finding one that works for the individual. Certain physicians and providers may have favorites or ones they have found to be effective for specific types of patients. These medications work in various ways. Some may interfere with the activation of T cells, a significant issue in the autoimmune response. Others reduce inflammation and the overall amount of immune activity that causes self-harm. Some block immune system cells to prevent extra cells from entering the central nervous system, where they can cause damage, while others decrease the overall number of immune system cells.

These disease-modifying therapies decrease relapses and delay disability by limiting new progression and immune activity, particularly in the central nervous system, where damage to myelin and axons occurs. These medications have specific functions that depend on the person's progression, their tolerance of side effects, and how well they respond to treatment. In some cases, a cocktail or a combination of these options is used, depending on the person's needs.

The more experience a provider has with these drugs, the better the outcomes tend to be. Most of us working in healthcare understand that there is a level of educated guessing involved in this process. It is often an art as much as it is a science. Because of this, having a team with extensive experience at a multidisciplinary center that specializes in MS is really where the best care happens. These drugs can be administered orally, by injection, or by intravenous infusion. The frequency varies greatly, ranging from daily to weekly, monthly, or even quarterly. There are various ways these work and impact our clients.

Unfortunately, for a small percentage of clients, these therapies are ineffective. It is essential to be able to navigate those situations. When the disease-modifying therapies are not working as they should, or if a person cannot tolerate them, or if there is still progression despite taking them, we have to look at other management strategies.

MS Symptoms

These are the symptoms. As you can see, there is quite a variety of things that can occur. Because damage in the central nervous system can happen basically anywhere in the brain, spinal cord, or optic nerve, you end up with a jumble of possible issues. It is also very challenging to predict the specific symptoms a person may experience. Just because you have a symptom one time does not mean it is going to happen again, and just because you have a terrible relapse does not mean you are not going to remit right out of that.

There are times, once the disease is secondary progressive or if you have that primary progressive from the beginning, where those symptoms are not going to resolve. They could potentially worsen as those areas of plaques and lesions grow slightly larger or as new areas develop in the exact location, which further exacerbates the issue. We are going to talk about a number of these, including cognitive and visual problems, fatigue, exercise, pain, and spasticity.

One thing to notice is the high number of people who express fatigue. I think that is a classic sign of MS. However, eighty percent have pain, and ninety percent have spasticity. I think that is probably not as well-known. You can also have bowel and bladder issues, speech disturbances, postural control problems, and sensory changes. There are certainly many different types of symptoms, depending on the exact location of those lesions.

MS Causes

If we look at the causes, because it is believed to be autoimmune, there has to be a trigger. The current thinking is that you do not inherit MS specifically, but instead you inherit a genetic risk. Numerous genes may influence the immune system and potentially contribute to the development of autoimmune conditions. More and more theories suggest it takes a person a certain number of hits for something like MS or ALS to turn on. I might need twenty hits before my genes turn on for MS, and you might need ten hits before yours turn on.

Those hits might be anything. They could be environmental factors, an injury, stress, toxins, a lack of vitamin D, or a virus or two. Researchers have found that smoking and obesity, as well as the Epstein-Barr virus that causes mononucleosis, seem to be linked a little more closely for some people, though certainly not for everyone. If people already have an immune system dysfunction due to another condition, they may have an increased vulnerability; however, ultimately, the number of hits is probably what we inherit. If my mother has MS, it does not mean that I am going to get MS, but I may have a higher risk than the general public, just because my genes make me more vulnerable.

There is one environmental factor, the lack of vitamin D, which seems to make sense, as it is associated with people who live farther from the equator, such as Caucasians of Northern European descent. Vitamin D, which is activated by sunlight, aligns with the pattern of people living in colder and cloudier regions with reduced sun exposure. Now, the solution to MS is not dumping 50,000 units of vitamin D into your system; that is not how this works. However, keeping our bodies as healthy and happy as possible by addressing environmental factors like smoking, obesity, or vitamin D deficiency certainly makes a lot of sense for all of us.

Exacerbating Factors of MS

As we examine the factors that exacerbate MS, many of these are generally well-known, particularly the impact of heat. Heat and humidity have such a significant impact that the National MS Society and other organizations actually provide grants for air conditioners. Other primary triggers include emotional stress and overall health issues, such as being sick for different reasons or hyperventilation, which often go hand in hand with anxiety and stress. Being completely exhausted, dehydrated, or suffering from malnutrition are also critical factors. If you don't feel good, you might not feel like eating. In some cases, people living in food deserts may have limited access to food options, often relying on gas stations where they purchase chips and other snacks. Often, they are simply trying to fill their bellies and cannot prioritize their nutrition.

Sleep deprivation is another primary concern. The more worried, stressed, exhausted, and dehydrated we are, the poorer our sleep quality becomes. All of these factors can exacerbate the condition. They can not only cause a relapse but can also make an existing one worse. From the outset, our goal is to reduce the number of relapses, minimize their severity, and accelerate the time to remission. Therefore, it is essential for clients to monitor these factors closely.

Prognosis For MS

When clients ask me about their prognosis, they often want to know exactly what they can expect and what their long-term future looks like. My response is usually that, while I have many ideas based on experience, we cannot be certain how things will turn out for each individual. It is important to note that a tiny percentage of people actually die from MS, and life expectancy is typically not different from the general population. As you might expect, those with relapsing remitting MS generally do better than those with primary progressive MS. If a client is jumping back up to their baseline after a relapse, that is a much different scenario than the slippery slope of primary progressive. Additionally, I have observed that clients who are younger at the time of onset indeed tend to do better than those who are diagnosed at an older age.

MS: Medical Management

Unfortunately, there is currently no way to prevent or fully cure this condition, so we must focus on getting people started on disease-modifying therapies as early as possible. In addition to these therapies, symptom management is a critical component of our practice. If a client is experiencing depression or anxiety, we may see the use of antidepressants. At the same time, spasticity might be managed with specific medications or even a baclofen pump for more severe cases. Corticosteroids remain the primary intervention for addressing inflammation, especially during a relapse, when a client might be admitted to the hospital for high-dose administration to manage an exacerbation. We also frequently see the use of immunomodulators to help manage the immune system response.

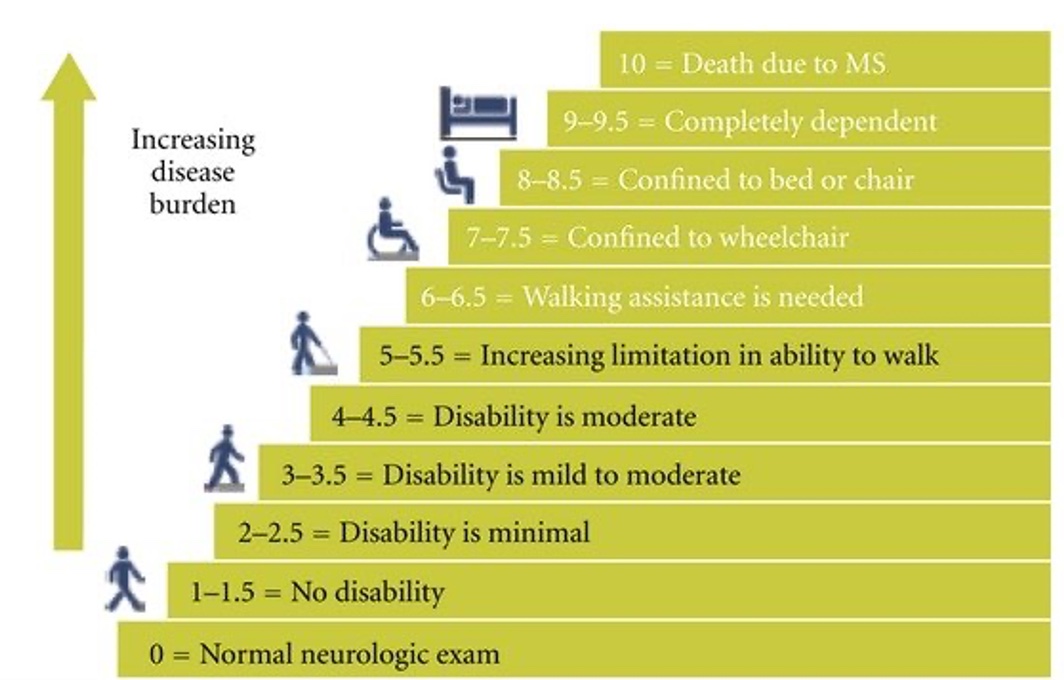

I find it helpful to reference the Expanded Disability Status Scale, or EDSS, which is specifically designed for MS and often visualized as a staircase, as seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS). (Click here to enlarge the image.)

As a client moves up the stairs in this model and the numbers increase, the disease burden becomes greater. A score of zero represents a standard neurological exam. At the same time, ten indicates death due to MS. Having a disability scale like this is beneficial because it provides us with a standardized way to track progression. It is also a vital tool for research studies, as they often require participants to have a specific qualifying number, such as an EDSS score of three or higher. While there are very specific clinical guidelines for each level beyond just describing it as minimal disability, this scale ultimately allows us to have a common language when discussing a client's status.

Exercise

Let us move on to a discussion about exercise. I have a significant amount of research and information regarding exercise to share with you. One of the items on your resource list is a collection of studies that I encourage you to review. A few recent studies from 2024 examine exercise as a means of reducing frailty and overall disability. While exercise improves mental health and quality of life for many of us, these studies suggest that it does not necessarily reduce fall risk. It is often difficult to discern the truth when one review claims one thing and another claims something else. We must always consider how well the studies were conducted, their size, and how recently they were published. One study found that exercise reduced physical disability and brain atrophy, which is excellent as it means fewer lesions or problematic areas. While it may not alter fall risk, it did show improvements in balance, mood, and quality of life, while reducing fatigue and enhancing brain function.

Despite these benefits, only about twenty percent of people diagnosed with MS actually engage in regular physical activity. We have to ask ourselves why this number is so low. Perhaps they do not know what to do or how hard to push themselves. They may be so exhausted that they fear exercise will trigger a relapse, or they may fear becoming overheated. One of my goals for this lecture is to give you ideas to help increase that percentage. For those who do engage, the recommendations include aerobic training, resistance exercise, stretching, flexibility, and balance activities. A meta-analysis noted that exercise has the most impact on fatigue for younger clients. While research shows that exercise helps alleviate fatigue, for many of us, the gym is often the first thing to go when we are tired. We want to go home and rest on the couch with comfort foods. However, once we actually get to the gym, we often find that we feel much better and the fatigue lifts.

Our guidelines at this clinic suggest that if a client has a muscle grade of three plus or above, you can add resistance to their tolerance. If they are at a grade three or less, we move toward functional exercise. This is a term I use that most therapists understand as involving the performance of occupations and meaningful activities through exercise. We recommend water aerobics or pool exercises, which reduce weight-bearing, as well as the recumbent bike, general aerobics, and stretching. We also discuss activities like yoga and tai chi for balance, provided they are done safely. It is quite easy to fall over during yoga, so clients must be careful. We must monitor them to ensure we are not increasing fatigue dramatically. A client should recover from exercise within about an hour. We do not want to increase pain or disability or potentially cause a fall by overstressing the muscles.

I sometimes see clients who cannot even close their hand, yet want to know what they can squeeze to get stronger. In those cases, I tell them to work on closing their hand until they gain more strength. Because people always want something tangible to do, I might give them a piece of very soft memory foam that squashes easily, to give them the feeling of exercising. For many people, their daily routine of chasing children, driving, shopping for groceries, and working is already a significant amount of exercise. If a client cannot raise their arm over their head, they certainly do not need to be adding weights to it. We need to be smart and focus on that functional exercise.

The National MS Society has published exercise guidelines that combine evidence reviews with expert opinion. They used the EDSS scale to provide recommendations for every stage of the disease. This is a fantastic resource published by Kalb et al in 2020. For example, for a client at a 7.0 to 7.5 level who has a diminished ability to perform ADLs and is non-ambulatory, the guidelines acknowledge that research is limited. The expert opinion is that these individuals must continue to move, even when seated. Any functional movement, including ADLs, counts as physical activity. They may engage in adapted physical activity or wheelchair sports, and they will likely need a rehabilitation professional like us to help integrate these activities into their lives.

These guidelines also provide specific strategies for individuals who are non-ambulatory. If they can take even a couple of steps with assistance, we should get them up. It feels good to get weight off their body and onto their legs, which can also help with spasticity. If they have a chair with a seat elevation feature, they can use it to practice safe sit-to-stand transitions. They might use a manual chair for mobility, participate in assisted swimming, or try seated dancing, yoga, or boxing. Using their arms and legs for pressure relief is also essential. These guidelines are excellent for therapists who do not treat MS frequently and may feel at a loss for where to begin. I have included a slide later in the presentation with websites where you can access these resources.

Cognitive/Behavioral Symptoms

Moving into cognitive and behavioral symptoms, sixty-five percent of people can have detectable issues. It can be difficult to determine if these challenges are at a client's baseline, related to their educational background, or perhaps due to comorbid conditions like ADD. Still, family and caregivers often report that the person seems different. There are pretty specific cognitive symptoms you will encounter, primarily prolonged response times to process information. I see this frequently in my wheelchair clinic. When I am performing a fitting or delivery, it takes clients a long time to fully process my instructions. If I do not utilize a teach-back method, having them show me what they learned and practicing it several times during that session, they are likely to retain the information. This involves verbal and visual spatial memory as well as processing speed, language fluency, and abstract reasoning, all of which make daily functioning a challenge.

I recently scheduled a wheelchair evaluation for a client with MS. She wrote down the address, time, and date, then asked me to text her a week prior, a day before, and to call her two hours before the appointment. Since I knew I might not remember those specific intervals, I set alerts in my own calendar to ensure I followed through. As she wrote the information down, she read it back to me to ensure accuracy and to give her brain another chance to encode the details. She was using every strategy possible to manage her issues. Whether she learned these from an OT or developed them herself, they are excellent strategies. If a practitioner cannot provide those reminders, a caregiver or an automated phone alert must be used, especially when the client has to coordinate transportation and multiple steps to attend the appointment. While there is one drug, dalfampridine, that has a modest positive effect on cognition, the focus is generally on management strategies. Relapses often appear physical, such as a sudden inability to walk or the onset of double vision, but cognitive and behavioral changes can also occur during a relapse and may improve as the exacerbation resolves.

Emotional lability is another significant issue. I find that I am yelled at by clients with MS more than any other population, often twice a week. These outbursts are usually about things that are not my fault, such as a denied wheelchair or the lack of funding for a ramp, but whoever answers the phone becomes the target. This tendency toward easy anger and frustration is part of that lability, compounded by depression, anxiety, and the stress of managing parenting or work responsibilities. Adding cognitive deficits to those life roles makes everything incredibly difficult. To address this, we can use the Cognitive Orientation to Daily Occupational Performance, or CO-OP. This framework involves a goal, plan, do, check cycle. For instance, if a goal is to stop missing healthcare appointments, the client identifies the challenges and creates a plan. This might include setting specific phone alarms or placing reminders in certain locations. In an outpatient setting, you might work on one of these self-selected goals each week. You try the plan and then check back to see if it worked. If it did not, you refine the plan and try again. Much like the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure, CO-OP utilizes goals that the client chooses, which is highly motivating. Research has shown that this process enables the generalization of strategies, meaning a strategy learned for one task can help the client process information across multiple areas of their life. I highly recommend this process for both clients and practitioners seeking effective cognitive management strategies.

Cognition

To reiterate some of these points, many people with MS experience memory issues, struggle to stay organized, and are often easily overwhelmed by information. The wheelchair evaluation and fitting process, in particular, is a significant undertaking for many people to handle. I strongly recommend they bring at least one other person with them. I personally am comfortable being recorded or videoed, although I know some practitioners are not, as it allows the client to process and review the information again later. I also send videos from wheelchair websites that demonstrate specific uses of the joystick or power features.

Clients may need information delivered more slowly and in a multimodal way. This means it is not just about listening or seeing, but also about doing and practicing through the teach-back method until it is mastered. At some point, they will likely require assistance with higher-level thinking and problem-solving. I once had a client here with her mother, and as the client was describing her abilities, the mother was in the background, clearly signaling that it was not the case. They actually began to argue in my office because the client truly did not realize the extent of the challenges she was facing. Ultimately, the mother moved in to help with the children and manage the day-to-day tasks, as the client could no longer handle unexpected changes. She could manage the basic task of putting food on the table, but she was unable to navigate issues like missing an ingredient, the store being closed, or a change in schedule due to a holiday. These are the types of executive functioning challenges we must be prepared to address.

Spasticity

When we examine spasticity, approximately ninety percent of people experience it, making it extremely common. In my clinical experience, it appears to be more prevalent in the lower body. I see a lot of extensor tone, which leads to clients sliding out of their chairs, sliding off the bed during transfers, or generally struggling with positioning because they are thrown into a full extension posture. You will also notice a significant amount of clonus, where the ankles are bouncing, and occasionally, this may also be observed in the wrists. While it can sometimes present as simple muscle spasms, stiffness, or cramping, for many, it is true spasticity that reacts to medications and is measurable on a Modified Ashworth Scale.

For many people, spasticity causes significant pain. Lately, due to my own blood chemistry, I have been experiencing some cramping. It is the kind of charley horse that I cannot walk off; weight bearing does not help. I find myself just sitting there, rocking and moaning, trying to make it stop. For the first time, I am genuinely feeling that sense of anxiety that comes with a spasm that feels like it will never end. This has given me a new perspective on what our clients endure.

As therapy practitioners, we understand that stretching and exercise can help. For clients who are only able to sit, getting into a standing position is beneficial. There are wheelchairs available now, particularly from Permobil, that allow a person to stand. They have designed these, so the base and tilt features are covered by insurance, meaning the client only has to pay for the standing component, which is typically not covered by Medicare. There is currently a significant push within the seating and mobility community to incorporate standing features. If a client can use a standing frame or even the seat elevate feature on their chair to get upright, it can make a difference. Cold therapy is also calming for spasticity. I recently educated my students on various ways to calm these symptoms, including complementary and alternative medicine. Many people find these methods helpful for relaxation, deep breathing, and identifying triggers. Acupuncture can also have an impact.

Daily spasticity can have a profoundly impactful effect, particularly when it affects the upper body. In my experience, it is often those with primary progressive MS who demonstrate significant flexor or extensor synergies where the entire arm becomes tight and nonfunctional. Usually, one side is dramatically worse than the other. If a client has spasticity to the point where they cannot take enough oral medication like baclofen or Dantrium without side effects like extreme sleepiness, they may require a baclofen pump. This is a hockey puck-sized device placed under the skin of the abdomen with a catheter that delivers medication directly into the spinal fluid. Because it does not have to cross the blood-brain barrier, you avoid many systemic side effects while the medication goes precisely where it is needed. Clients who are struggling with spasticity that causes falls, pain, and tightness should certainly talk to their medical team about a baclofen pump trial.

Fatigue

Fatigue is another symptom that makes life incredibly difficult for our clients. It is interesting to note that while various reviews and meta-analyses show different prevalence rates ranging from 52% to 91%, every study confirms its significant presence. Research has not found a specific cause for why people with MS experience such profound fatigue, nor is there a highly effective medication. However, one exists with a very mild impact. If you have ever had the flu or COVID and felt completely exhausted just trying to return to work or handle family responsibilities, you have a small sense of what this is like. For our clients, however, this fatigue is constant and all-consuming.

When the MS process directly causes fatigue, it is believed to be chemically or endocrinally related, stemming from the immune response or specific lesions. We also see secondary fatigue caused by mood, poor sleep, medication side effects, depression, or anxiety. Due to its significant impact, numerous studies have been conducted on the topic, including a randomized controlled trial known as the REFRESH study, which stands for Reducing Fatigue, Restoring Energy to Support Health. This was an educational self-management program designed to teach people how to listen to their bodies, use proper body mechanics, and set up their homes more efficiently. It emphasized the importance of setting priorities and finding a balance between activities to prevent total exhaustion.

The participants in that study provided valuable insights relevant to our practice. They noted the constant trade-offs required in their daily lives. If they chose to attend a child's baseball game in the afternoon, they had to accept that they would not be able to go out to dinner that evening. These trade-offs are incredibly challenging when trying to manage a family and a social life. Many people found they needed a much slower physical pace and required multiple rest breaks throughout the day. A typical pattern is the tendency to over-participate on a good day, only to face a crash that leaves them in bed for the following two or three days. It is a difficult balance to maintain.

Furthermore, there is a painful social element to fatigue. Clients reported that family, friends, and the public often became annoyed with them. More heartbreakingly, the clients became annoyed with themselves, using self-deprecating remarks and referring to themselves as lazy. This angst over not being able to get off the couch has a profound impact on their confidence and participation. Their lives become unpredictable, and they often have to give tentative answers to invitations because they don't know how they will feel on the day in question. They also noted that as they get more tired, their thinking becomes more confused and jumbled. Because MS fatigue is often an invisible symptom, they feel misunderstood or judged by others who think they are simply faking it to get out of responsibilities. If you have ever pushed yourself through a physical feat that left you unable to lift a glass of water the next day, you know that this kind of fatigue is very real.

As practitioners, we help people value the things that are most important to them. We examine the occupations they need, want, and are required to do. We teach them how to pace and prioritize, permitting them to say they don't have to be the one to unload the dishwasher if they are too exhausted at that time of day. We might recommend support groups so they can talk to others who have found creative solutions. Most importantly, we help them find a way to give themselves grace and recognize they are doing their best. I believe the occupational therapy practitioner is the perfect professional to manage this because we are experts at prioritizing. Even if your formal goal for insurance is focused on safety, performance, or strength, you are constantly discussing these priorities as you move and act with your client.

Weakness

Many people with MS experience significant weakness, which contributes to a high fall risk. This can manifest as postural weakness or limb weakness, and in some cases, it may be isolated to a single hand. We also observe tremors, somewhat similar to those seen in Parkinson's disease, as well as ataxia. This ataxia involves challenges with motor planning, such as overshooting or undershooting, which can make even a simple task, like eating, challenging.

It is important to note that many of the exercise guidelines currently being studied are focused on ambulatory clients, specifically those with mild to moderate impairment in strength, fitness, and balance. As Gooch mentioned, the evidence is much less clear for clients who are more severely affected. For individuals primarily focused on maintaining basic function or quality of life, there is limited published information available. This is where we come in. Adapting environments and activities to help people stay as functional as possible is the absolute bailiwick of occupational and physical therapy practitioners.

Vision

Vision issues are often the first symptom someone experiences with MS. One of the most common is optic neuritis, which is actually inflammation of the optic nerve directly. You can see the demyelination indicated in red on the diagram. Clients may experience deficits in visual acuity related to light, where everything appears darker or colors seem less vibrant. This affects central vision, making tasks such as reading or looking at faces particularly challenging.

They might also experience double vision. To refresh your memory from school, saccades involve moving the eyes quickly between two targets, such as watching a child and then watching a car. Being able to perform those movements without getting dizzy is a common challenge. We also observe abnormal eye movements because the eye muscles are not functioning correctly, and some clients experience issues that resemble retinopathy or even direct eye muscle pain.

While researching for this course, I came across a few fascinating phenomena in an article by Tong, specifically noting that heat can negatively impact vision. This can affect motion perception, which is linked to those saccades, as well as general acuity and retinal health. For most people, one eye is significantly worse than the other, which is consistent with how MS often affects one side of the body more than the other. Fortunately, after a relapse or that initial symptom, vision usually improves. As with all our interventions for MS, the goal is to decrease the number of relapses and prevent that slippery slope into secondary progressive disease.

Postural Control

Much like the challenges we see with vision, postural control is deeply affected by the disease process and the side effects of medications. If a drug makes a client feel vertiginous or lightheaded, their balance will naturally suffer. I recently worked with a client who was leaning slightly to one side. One leg was positioned further off the cushion than the other, and one shoulder was noticeably lower. When she asked why her leg was displaced, I placed my hands on her pelvis and explained that her pelvis was rotating outward on that side. We straightened her out so her knees were even, but within ten seconds, her body had shifted her right back into that original position without her even realizing it. That posture had become her new position of function or comfort, likely because the lower side was her stronger side and the one she relied on more.

When clients experience these balance deficits or are recovering from a relapse, they often find themselves back in therapy. Our physical therapy colleagues frequently work on gait and balance tasks to help them move safely again. One particularly fascinating area of recent research involves dual-task performance. The studies show that when you simultaneously perform a postural task and a cognitive load task, they interfere with each other. For example, if I am picking up my pet’s water dish from the floor while simultaneously wondering where to buy distilled water or thinking about whether the dish needs to be washed, those two tasks compete for my attention and resources.

To me, this is a significant realization that explains why people with MS face so many daily hurdles. In many cases, they cannot safely do two things at once. Part of our role is helping them learn to focus on one task at a time. If they need to pick something up, they should focus entirely on that movement. I might suggest they pull over a chair or a stool and sit down for a second, so they don't fall while grabbing the object and thinking about all the other things they need to do. Acknowledging this interference between thinking and moving is a vital part of helping our clients manage their safety.

Sensory, Pain

Sensory issues are remarkably prevalent in this population, manifesting as numbness, tingling, or actual neuropathic pain such as itching, electric shocks, burning, or stabbing sensations similar to other neuropathies. There is also a phenomenon known as the MS hug, which is a squeezing sensation around the torso. It is a very strange experience that often causes significant anxiety and shortness of breath, as clients feel like they are being squeezed far too tightly by an unseen force. While clinically interesting, it is a distressing symptom for the client to manage.

We also see cases of trigeminal neuralgia, which involves life-changing, significant pain in the face and jaw. Beyond these primary neurological sensations, clients often experience secondary pain resulting from falls, spasticity, or the consequences of being more sedentary, such as pressure, tightness, and eye strain. During my wheelchair evaluations, I frequently have to tease out which pains are direct symptoms of MS and which are the result of secondary issues like old injuries or rotator cuff problems exacerbated by their current level of function. Pain, in all its forms, is incredibly impactful and must be a central part of our clinical conversation.

Bowel and Bladder

Bowel and bladder issues are also a significant concern, with the bladder being impacted in about eighty percent of people. This can manifest as urgency or an inability to start or empty the bladder due to spasticity at the bladder site. Conversely, incontinence and nocturnal enuresis, where a person urinates while asleep, are usually the result of weakness or flaccidity in the bladder muscles. Urgency can also stem from these issues. Depending on the specific diagnosis, there are medications available to help manage these symptoms.

In some cases, toileting and managing bodily waste become so difficult that individuals opt for a suprapubic catheter to manage urine and a colostomy bag for feces. For some families, the physical burden of transfers is so great, and the risk of skin breakdown due to moisture so high, that these surgical interventions are the most viable solution to allow the client to go out in public again. Regarding bowel function, we frequently see constipation, especially if a client is sitting more, struggling with malnutrition, or not eating well. Some individuals also face bowel incontinence, which is a social nightmare and incredibly difficult to manage. Additionally, as with almost any drug, many of the medications used for MS or related diets can have significant GI side effects that further impact the client's daily life.

Other Symptoms

The disease process itself often brings a unique cycle of grief. Because it can be progressive, individuals do not just experience grief once; instead, they face new challenges that continuously cause fresh stress and anxiety. There is also a condition called pseudobulbar affect, or PBA, which involves uncontrollable laughing or crying and occurs in about ten percent of people. Fortunately, a drug called Nuedexta is very effective for most people to manage these symptoms. It is very disconcerting when a client is screaming or sobbing but cannot explain why they are sad. I have had this happen when we are discussing a client's first wheelchair, which can be a complicated topic.

Sexual dysfunction is another issue that affects many people, whether from medication side effects or the MS itself. This can include issues with lubrication, lack of arousal, decreased orgasms, and sensory or pain problems. There are also social factors to consider, such as when a partner becomes a primary caregiver, assisting with tasks like bathing and toileting. These shifts in roles are not particularly glamorous and can have a profound impact on intimacy. Speech can also be affected, including dysarthria, which results in garbled speech, or dysphonia, characterized by a very quiet or breathy voice. Clients might have to work much harder to produce sound and may sound hoarse or feel the need to clear their throats frequently.

Interestingly, twenty-five percent of people lose their sense of taste from MS. While we have heard a lot about this lately due to COVID, it is a significant factor in MS as well. Some individuals even lose their hearing, which was a detail I only discovered recently while updating information for this presentation. Finally, dysphagia, or difficulty swallowing, is a concern that typically becomes more common as the disease process advances.

Diet

Many people believe and feel that MS is deeply impacted by their diet, and there are several good studies supporting this, since certain foods are more inflammatory than others. As a diabetic, I know that things like sugars and certain carbohydrates are inflammatory to my system, while other foods are not. The same principle applies to MS. Clients generally want to focus on a heart-healthy diet that provides plenty of vitamin D and vitamin A. Research suggests that an individual's optimal diet may influence inflammation, immune response, and oxidative stress.

We have to be careful because clients can hold on tightly to specific dietary trends. For some, a change is very impactful, while for others, it is much less so. Indeed, maintaining a healthy diet helps with overall conditions like hyperlipidemia and obesity, as well as heart disease. Having a balanced diet and a healthy lifestyle is always important. Still, it is exciting that some studies show it may actually impact the pathology and the degeneration process of the disease.

I have reviewed several diets and the impacts noted in recent studies. The Mediterranean diet has been associated with a lower risk of MS onset in general. The Paleolithic diet, which mimics the eating habits of early humans, has been shown to improve fatigue in a few studies, although it also carries a risk of nutritional deficiencies. When people restrict their diets, they must be careful, especially since skipping dairy products can lead to low vitamin D levels. The Swank diet limits saturated fats and has shown a lower risk of relapse and reduced mortality in some studies. The McDougall diet focuses on carbohydrates from plants exclusively and has been shown to reduce fatigue.

Metabolic processes involving very low caloric intake or fasting have been shown to reduce inflammation; however, clients must ensure they are still obtaining the necessary nutrients. The ketogenic diet, which is high in fat and low in carbohydrates, showed both negative and positive impacts. Interestingly, a gluten-free diet showed no effect in the studies reviewed. This information is from 2022, but I chose to stick with this source because newer versions did not provide the same level of clarity regarding these specific dietary impacts.

Other Research in Progress

Research continues to investigate the potential impact of stem cells, as well as various drugs and drug combinations. There is a deep desire among both researchers and clients to find a way to actually cure or reverse the effects of MS rather than just modifying the current disease activity or preventing future relapses. Many are also hopeful for the development of a specific blood or cerebrospinal fluid test that could provide a definitive answer, rather than relying on a diagnosis of exclusion, which is currently the standard method for identifying MS. Furthermore, we want to continue identifying which of the two hundred genes mentioned earlier are being activated, which are protective, and which create a genetic vulnerability for individuals.

When Is OT Needed

When we consider when to initiate occupational therapy, there are several key transition points. For instance, a Jaco robotic arm is a remarkable piece of technology that enhances independence, although it is pretty expensive. Generally, we want to intervene after a relapse to help a client recover as much function as possible. Many individuals benefit from short bursts of therapy, perhaps for a few weeks, to return to their previous baseline, after which they can maintain that status for a year or two without further exacerbation.

In cases of secondary or primary progressive MS, we often see new problems cropping up every few months. Our role here is to explore options for improving cognition, balance, and addressing any new weaknesses that may appear. While it may not always be possible to regain full strength in these progressive stages due to the slippery slope I mentioned earlier, our goal remains to maximize function. This is precisely why almost all disease-modifying drugs are aimed at preventing clients from entering that progressive phase. If they can recover from a relapse and stay at their baseline, they have the potential to remain as functional as possible for a much longer period.

Factors for OT to Consider

When we consider how to support our clients, we must always look through the lens of personal, environmental, and occupational factors. These are all deeply impacted by the symptoms we have discussed, such as fatigue, weakness, cognitive shifts, and emotional changes. Everything works together, and as we build the occupational profile, we help people identify goals and strategies that address their specific needs. It is never just about the symptoms; it is about the time a task takes, whether their home environment can support that task, and if they have the necessary help from friends, family, or caregivers.

We are also responsible for teaching specific precautions. For instance, if a client loves to garden, they will likely need a cooling vest, especially in a climate like the Carolinas. They may need to work at the crack of dawn or near dusk, though even then, the heat can be persistent. We also have to be vigilant regarding shoulder instability. When you have a combination of weakness and spasticity, the shoulder can become misaligned quite quickly, leading to significant pain. As practitioners, we must assess if pain is coming from instability or weakness. This is not a no pain, no gain situation. We must respect the pain; if a specific motion, such as reaching into a high cabinet, hurts every time, we need to find an alternative, such as using a reacher or reorganizing the kitchen.

Safety is paramount, especially regarding the dual task interference between cognitive and physical demands. We need to educate both the client and their family that abilities may fluctuate not just day to day, but even throughout a single day. If a client wants to use heat for muscle pain, they must be cautious. We might suggest using a localized heat pack on a specific muscle while simultaneously wearing a cooling vest to keep their core temperature stable. Our interventions will always depend on the individual’s symptoms, whether that involves modifying transfers, recommending new bathing equipment, or managing the expectations of a client with primary progressive MS who wants to focus on strengthening when maintenance of function might be the more realistic priority.

OT and Using Adaptations

We must carefully decide when to introduce adaptive equipment and when our focus should remain on flexibility, stretching, and pain management. There are many different strategies to balance. In my experience, cognitive deficits often represent a significant barrier for clients with MS, affecting not only their ability to learn new things but also their willingness to accept changes. Because this disease can span thirty, forty, or fifty years, clients often have their entire lives and homes configured around a specific piece of equipment, like a scooter. They have it set to a certain height and have mastered getting in and out of it in a particular way.

When a client begins falling out of their scooter, it may be time to discuss a power wheelchair with seat elevation to keep them upright and safe. However, adding a feature like seat elevation creates a technical challenge. The motor for that lift must fit under the seat, which means we cannot consistently achieve a low seat-to-floor height. If their current scooter, toilet, bed, and car are all set at seventeen inches, but the lowest power chair with the necessary cushion and lift is nineteen and a half inches, that client is going to struggle significantly. Every transfer they have mastered over the years will suddenly become more difficult, and we have to be prepared to help them navigate that transition.

OT in Outpatient/Rehabilitation and Home Health

I have frequently coordinated with home health therapists to facilitate safe transitions for my clients. As an outpatient therapist in an MS center, I often find that the move from a scooter to a power chair is one of the most difficult shifts. Using adaptive equipment frequently feels like giving in to the disease; many clients believe that if they accept a power chair, they will never walk again. We have to help them navigate that acceptance. I often use the example of aging and needing reading glasses. I can fight the glasses, I can dislike how they look, and I can struggle against them as much as I want, but I am still aging, and my vision is still changing. The glasses do not worsen my eyesight; they allow me to function. As occupational therapists, we strive for functionality over aesthetics or perceptions. This conversation is vital because a wheelchair often feels like a permanent mark of disability rather than just a tool for a walking problem. There is often a great deal of crying when a client receives their first wheelchair, and providing that emotional reassurance is just as important as the physical fitting.

Referrals for outpatient therapy typically occur after a relapse, a fall, an injury, or a hospitalization, or when a client needs to visit a seating clinic for their first or subsequent mobility devices. In these moments, we are either trying to get them back to their previous baseline or trying to keep them safe. There are so many areas to address with MS that I genuinely believe occupational therapy is underutilized. If you know of an MS specialist in your area who is not referring every patient to OT, you should reach out and offer your services. When the hospital system I work for combined its ALS and MS neurology departments, my caseload effectively jumped from 200 people to 5,000. I now act primarily as a consultant, offering ideas while clients see outpatient or home health therapists closer to their homes.

I encourage community therapists to reach out to specialists like me. If you receive a referral from our center, please do not hesitate to call or email to request the complete clinical picture. Often, the therapist seeing the client never gets the whole "laundry list" of concerns that I have documented. In home health, much of the work involves finding ways to beg, borrow, or steal equipment to keep the client safe. It is important to remember that many communities and MS clinics have loaner closets. Organizations like the National MS Society may have funds available for small items, although this depends on their current fundraising efforts. It is always worth reaching out to see what resources are available.

Adaptations

When recommending bathroom equipment, remember the bidet. In the United States, this is typically a toilet seat and lid with a water spout underneath that hooks into the water supply, providing warm water and a drying feature. Most people in our country use a bidet because of hand and arm weakness. If you select one where the controls are attached to the side of the seat and that happens to be the client's weak side, it is a poor choice. Always look for a model with a separate remote, helping your clients spend their money wisely.

Furthermore, you cannot use a raised toilet seat that clamps on where the seat flips up, as you will end up spraying the ceiling with the bidet. You must get the height from under the toilet. A comfort height toilet is helpful, but a product like the Toilevator is a three-and-a-half-inch riser that goes under the toilet base itself. Once installed with longer screws, it provides the height needed to stand up more easily, especially when paired with grab bars. For urinary management in women, the Purewick is an option, and increasingly interesting solutions are emerging for men as well. If you haven't looked for urinary solutions recently, I encourage you to explore the new products available.

Clients do not necessarily need a forty-thousand-dollar bathroom renovation. A tub slider system, which might cost four or five thousand dollars, is a much more affordable alternative. These systems use a frame in the tub, a bridge, and a rolling shower chair that can often tilt or recline to help the client scoot across safely. For dressing, consider a long-term approach rather than relying solely on a button hook. Switching out buttons for magnets allows clients to keep wearing their own clothes without struggling. If a client is at a store and needs to use the restroom, they will likely not have their button hook with them, but magnets can be used anywhere. If a client has a weak pinch or grip, you can add loops to bra straps, underwear, or socks so they can use a thumb to pull the garment together.

Regarding eating, look for items that are easier to hold or lift. A mobile arm support attached to a table or wheelchair can be a game-changer for some. There are also costly power feeding devices, like the OB, which costs between $6,500 and $8,000. The company will often send a demo unit to your clinic for a thirty-day trial. While rarely covered by insurance, simply raising the plate and supporting the elbow to get everything at mouth level can be enough to increase independence. The same logic applies to grooming. If a client cannot get their hands to their head, have them bring their head to their hands by resting their elbows on a table. I recommend setting up a grooming station with a mirror, basin, and all necessary supplies in one place so they can work while seated and supported rather than struggling at a sink.

There are many simple adaptations to consider. Family members can pre-open non-carbonated bottles, and a jar pop can be used to break the vacuum seal on metal lids. A rolling cart with two handles can be easier to move than a rollator when carrying items. If an adjustable bed lacks a grab bar, you can attach a piece of rope, a sturdy belt, or even a length of webbing to the frame to give the client leverage for rolling and turning. If a bed is too tall, consider a half-height box spring or removing the box spring entirely. You can also add a strap to almost anything using scrap Velcro. By interlocking two loops like a paper chain—one around the item and one around the hand—you can prevent a client from dropping a razor, a brush, or even a garden tool. It is inexpensive, effective, and utilizes materials that most of us already have in our clinics.

Finally, do not overlook leisure skills. If a client loves golf but can no longer play, ask what they actually enjoy about it. If it is being with friends and being outdoors, perhaps they can still drive the cart and socialize while the others play. If they love gardening, they may consider transitioning from a large garden to container gardening in pots. As occupational therapists, we should always find ways to integrate these meaningful leisure activities into the ADL goals that are covered by insurance. Providing a loop for a razor can easily lead to a conversation about using that same strategy for a hobby they love.

Range of Motion, Pain Management

We must be incredibly mindful of the relationship between range of motion and pain. In our practice, we often encounter situations where we have to ask if the pursuit of a specific range is truly worth the discomfort. For instance, I can no longer achieve 180 degrees of shoulder flexion myself as I age. If a client is recovering from a specific rotator cuff injury and the muscle remains strong, some pain is expected during therapy. However, when the issue involves neurological weakness, joint instability, or spasticity, we must be much more cautious. Pushing through that type of pain can cause significant harm. Our role is to help clients identify movements that cause recurring pain and find ways to prevent re-injury or manage secondary complications, such as a frozen shoulder. If a client tells me that it hurts every time they perform a specific motion, we need to respect that signal and adapt.

Home Modification

It is essential to reorganize the environment to support independence and autonomy. Using a grabber, a dressing stick, or any other assistive tool can make a significant difference. When discussing home modifications, our goal is to help people make informed decisions with their money. If a client only has a bathroom on the second level with no half bath downstairs and no ability to renovate, we can consider options like portable showers. These consist of a frame that hooks into a clean water supply with a pump to remove the water, allowing someone to use a shower chair in the middle of a living room or any accessible space. While purchasing one can cost a couple of thousand dollars, it is a functional alternative to a complete renovation.

We also need to think about how they are going to manage stairs and what their emergency plans are. So many people have only one accessible way out of their house, which is a significant safety concern if that path is blocked. Regarding the bathroom, the wall of a small toilet room is often not load-bearing. Having a handyman remove that wall to open up the space can be a relatively affordable fix compared to a total remodel. Planning is key because the less time a client has to make these changes, the more they will cost. For those moving down that slippery slope of progression, they need to think extremely carefully before spending money on a stairlift. We have to consider what happens when they eventually need a power chair on the second level, or when their sitting balance, head control, and spasticity make a simple stair chair unsafe.

Kitchen modifications can also be simplified. A client can keep their counters but remove the lower cabinets in one section, allowing them to position a wheelchair closer to the workspace. Not every situation has an easy fix, such as homes with steps everywhere and very little yard space near the driveway. In those challenging cases, we have to get creative to find a way for them to manage.

Mobility

When considering mobility, remember to rule out lesser items first. Insurance is generally not supportive of a scooter intended only for long distances, even though that is precisely why most people want a mobility device in the first place. These devices must be for in-home use. While that is not all they can do, they must be functional within the house to be covered. If a client has a full flight of stairs and plans to keep a scooter in the garage, insurance is unlikely to cover it. The client needs to have access so that on a terrible, awful day, they could use the chair within their living space.

Many power chairs equipped with power features also include Bluetooth. This allows the chair controls to operate a phone, a tablet, a smart home, and various other devices. While many televisions still use infrared or radio waves, a chair that is Bluetooth-enabled can often bridge those gaps. Many equipment suppliers are hesitant to mention this because they do not want to become responsible for setting up a client's entire home. In these cases, you should work with the assistive technology program in your state. Every state receives funding for assistive technology, and those professionals are the right people to consult.

You can also find resources directly from power wheelchair manufacturers. Their websites often feature videos on how to turn on and set up these features. I have seen eye gaze wheelchair controls in action, and they are incredible. There are numerous technological advancements available now that can keep people quite functional even when they are experiencing significant weakness and spasticity.

Case Examples

Here are some case examples to tie some of these concepts together.

Case Example 1

I once worked with a woman who had relapsing remitting MS. She lived alone, and her right hand, which was her dominant hand, had become incredibly weak. She could only open her fingers by moving her wrist into a certain position and could only close them with her wrist extended, essentially using a true tenodesis grasp due to that finger weakness. She had transitioned almost entirely to using her left hand because of a severe relapse that had occurred six months prior. During that time, she could hardly use her right hand at all, so she got used to relying on her left. She came to me because she wanted to find ways to start using her right hand again and to strengthen it.

In MS, the faster a remission happens, the more likely a client is to recover their previous function fully. The longer a person stays in that state of relapse, the harder it is to get back out of it. Having someone still relying on tenodesis after six months was not an excellent sign for full recovery. She was determined to do strengthening exercises, so while we discussed functional exercises and stretching, she quickly became overwhelmed by all the gadgets and options I usually offer during a consultation.

I realized we needed to change our approach. Since she lived close by, I told her we would meet regularly and set just one goal at a time. Her goal for the first week was to start eating with her right hand again. When she returned for the second session, she was thrilled to report that she had successfully fed herself. That success motivated her to keep trying. While I was unsure how much stronger her hand would actually become, she was becoming significantly more functional because she was finally using it. Interestingly, by the next session, she had already begun using her right hand for other tasks independently. We then moved on to her next goal, which was working on buttons and zippers. I am never one to say that people should not work on strengthening, but so often it really comes down to function and helping a client use what they have as effectively as possible.

Case Example 2

Another case example involves a younger gentleman with primary progressive MS who was very significantly impacted. He presented with complex motor control issues that were almost athetoid in nature, appearing somewhat Parkinsonian, jumpy, and dyskinetic. It was a very unusual and interesting clinical picture. His vision was relatively poor, and he was unable to stand without falling. His mother, who was at least in her 70s, was really struggling to provide the level of help he needed. He was in the process of considering his first wheelchair and was understandably very upset by the transition. Given his vision and motor control challenges, I was initially worried that operating a power chair would be too difficult for him. However, he turned out to be a total rock star. By focusing on intentional movement and performing some specific reprogramming of the chair's electronics to accommodate his tremors, he was able to drive safely. This immediately made his entire life safer for both him and his mother. Additionally, they worked on modifying their home, where they had two steps at the entrance, by installing a ramp and finding other ways to make their environment more accessible.

Case Example 3

This case involves an older woman who has lived with MS since her 30s. For nearly three decades, she experienced very few relapses and managed her stressors well. To the casual observer, her symptoms were almost unnoticeable. However, she eventually began experiencing more frequent relapses. She transitioned into secondary progressive MS. She uses a power chair and has remained remarkably active, gardening, taking care of her home, and watching her grandchildren all from her chair because she can no longer stand safely.

Over time, trunk weakness caused her to become very kyphotic with a forward head position, and she began leaning heavily to the left. To address this, she needs to utilize tilt and recline features, as well as additional lateral supports; however, she is very resentful of these additions because she feels they limit her functionality. She constantly complains about having to push herself upright manually. I explained that if she wants to stop pushing herself up, something has to give. I suggested staying upright only for specific tasks, such as eating at a table, and using tilt for the rest of the day. Still, this transition is complex because her identity is tied to being an active, hands-on grandmother.

She calls me once or twice a week, insisting her chair is broken because she is leaning too much. In reality, the chair is functioning, but her physical needs are changing. We have tried numerous backrests and configurations, but she truly needs to utilize the tilt and recline functions to maintain her position. Her transfers are also quite dangerous, as her partner essentially hauls her up by her waist. It is a challenging situation because there is only so much an external professional can do. Much of the adaptation has to come from an internal acceptance of the disease's progression, which is incredibly hard for clients. Her increasing distress is a significant challenge for me, and I suspect it is a challenge many of you face when working with this population as well.

MS Information

Much of the information presented here is sourced from reputable resources, including the National MS Society. They have organizations in nearly every state, and many offer excellent educational series for healthcare professionals. I have participated in an interdisciplinary series in North Carolina that brings together physicians, residents, therapists, and other specialists to review research and collaborate on complex cases. These programs often include guests living with MS to help clinicians bridge the gap between clinical data and lived experience. These organizations provide up-to-date information through email blasts, offer various grants, and manage loaner closets for equipment. They are also vital for debunking myths, such as unproven and expensive stem cell treatments that promise total cures.

I encourage you to help your clients connect with specialized MS centers. If they cannot travel, many centers now offer virtual consultations. Whether you work in home health, outpatient, or acute care, it is crucial to help your clients understand that occupational therapy should be a recurring part of their care. If a client is changing slowly, you may not see them for a few years, but if they are progressing or experiencing a relapse, they need focused and frequent intervention. The goals will shift over time. Success may not be about returning to a five out of five strength grade; instead, it will focus on safety, education, transfers, bed mobility, bathing, and pain management.

Questions and Answers

How does the loss of taste—common in MS and aging—influence body weight? Do people typically lose or gain weight?

Traditionally, the assumption is that if food doesn't taste good, people will lose weight (which is often seen in the elderly). However, with MS patients, the impact varies.

While I don't have specific research on hand, I've observed that many people start "hunting" for flavors. They may seek out very spicy or bold foods to find something they can actually taste. Because of this, the weight often remains the same or increases: Some patients gain weight because they are seeking satisfying flavors. It can be hard to isolate taste as the sole cause, as weight gain may also be linked to becoming more sedentary due to the condition.

Are there free local MS support groups available, and how can I find them?

Yes, absolutely. There are many options available, ranging from traditional in-person meetings to hybrid and fully virtual groups. Here is how to find them:

National MS Center: Visit their website and search by state, region, or city. You can also call them directly for a curated list.

Online Search: A simple Google search for "MS support groups in [Your City]" is usually very effective.

Virtual Options: If you don't find a local group that feels like a good fit, consider looking for virtual-only groups, which allow you to connect with people from outside your immediate geographic area.

Thank you so much for attending today's webinar. Everyone. Thank you.

References

See additional handout.

Citation

Ward, A. L. (2025). Supporting clients with MS: Presentation and management. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5848. Retrieved from https://OccupationalTherapy.com