Alicia: Thank you for coming to this webinar. I am going to be going over therapy management of burn injuries. I will address the purpose of burn rehabilitation, some basic information about burn wound classification, burn wound healing, burn rehab evaluations, special considerations for patients with burn wounds, and some burn wound intervention ideas. Then, we will go over a couple case studies

Introduction

Let's first take a look at this picture (see Figure 1). What is wrong with this foot? I will give you just a couple seconds to think about that.

Figure 1. Burn contracture.

This is not a foot. This is actually someone's upper extremity. This is their hand and heir fingers have contracted back. Their wrist has also completely contracted into the extension position, and the elbow has contracted into flexion at about 90 degrees. This is a good indication of how severe burn contractures can be if we do not get ahead of the range of motion and stretching during the appropriate phase that we will go over here in a moment. We are going to circle back around to this again later in the presentation, but I want you to keep this in the back of your head whenever we are going over the functions of skin and classifications.

Purpose of Burn Rehabilitation

- Prevent and/or minimize contracture development

- Maintain range of movement

- Maximize functional ability

- Maximize psychological well-being

- Maximize social integration

The purpose of burn rehabilitation is to prevent and minimize contracture development, while maintaining range of motion and maximizing functional ability, psychological well-being, and social integration. A lot of this is used in your everyday patient care, but preventing and minimizing contracture development by maintaining range of motion are really the key points in burn rehabilitation.

Functions of the Skin

The skin is the body's largest organ and has many functions.

- Protection

- Mechanical Impact

- Infection

- Radiation

- Fluids

- Thermal Regulation

- Sensation

- Absorption

- Excretion

- Vitamin D Synthesis

It forms a barrier that helps prevent harmful microorganisms and chemicals from entering the body. It also prevents the loss of life sustaining body fluids. Skin protects us from mechanical impact during falls and abrasions, it helps protect of the body from infection and the harmful effects of the sun and radiation. It maintains our fluids, thermal regulation, and provides sensation. Skin is where all of our sensory receptors are that detect pain, pressure, and temperature. It helps with absorption and excretion, like toxic substances with sweat. It also plays a role in vitamin D synthesis.

Integumentary System

Our integumentary system is made up of the skin and its appendages.The skin is comprised of the epidermis and the dermis. The epidermis is the outermost layer. It is primarily made up of epithelial cells. It does not contain any blood vessels so it is avascular. Its main functions are for protection, absorption of nutrients, and homeostasis. This is what provides our initial barrier to the external environments.

The dermis is actually made up of two layers, the papillary layer and the reticular layer. The papillary layer is loosely organized wiith collagen and elastic fibers. It intertwines with the rete pegs of the epidermis. This is what keeps the epidermis and the dermis joined together, and this will also come up again later as we talk about scar healing. The reticular layer is densely packed collagen and elastic fibers. It merges with the subcutaneous tissue below.

The subcutaneous layer is not part of the skin. It contains the hair roots, sebaceous glands, sweat glands, receptors, nails, and blood vessels. It is primarily for shock absorption and body insulation. Specifically with burns, we are especially focused on the epidermis and the dermis because that is how we classify our burn wound injuries.

Causes of Burns

There are several causes of burns.

- Thermal

- Electrical

- Chemical

- Radiant

The most common type is the thermal burn, when you come into direct contact with heat like a fire. An example would be a child touching their hand on a stove or a blast injury. Electrical burns are caused by contact with a high or low voltage electricity both AC and DC currents. It is always a full thickness injury and the most destructive cause of a burn. There is usually an entry and an exit wound and many hidden internal injuries. The problem is that we cannot see what is beneath the skin because when it travels from the entry to the exit it causes a lot of internal heat damage. We have to wait for those injuries to present themselves, and sometimes this can take up to 72 hours to truly declare themselves. It is a waiting game, and we always admit electrical injuries into burn units. Another type is a chemical burn or contact with a caustic substance. The time of contact usually determines the depth of injury. This can either be acidic or alkalized. If it is a liquid you want to rinse it off with water. If it is a powder you want to dust it off before you rinse it off. One of the things that we mostly saw in our military population was white phosphorous burns. Radiant burns are direct contact with radiation. These can be caused by sunburn, nuclear flashes, x-rays, gamma rays, and those types of things.

Burn Wound Classifications

We are moving away from the first, second, and third degree burn classifications. We have begun to classify burns as superficial, superficial partial thickness, deep partial thickness, and full thickness. Superficial burns are first degree burns. Second degree burns are your superficial partial and your deep partial. Your full thickness burns are going to be your third degree burns.

Superficial

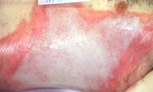

For your superficial thickness, your epidermis is what is involved, and it is red without blisters, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Example of a superficial thickness burn.

It blanches with pressure so whenever you push down on it and release, it will turn white and then quickly back to that pinky red color. Typically, these are like sunburns. They are painful and dry. Usually, it takes about three to seven days for them to heal. From a therapy standpoint there is no significant risk for a contracture. These are going to heal on their own with no scarring.

Superficial Partial Thickness

Superficial partial thickness extends into the superficial dermis so that your hair follicles and glands are preserved (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Example of a superficial partial thickness burn.

There is going to be redness with blisters, and it will still continue to blanch with pressure. They are also going to be very moist and weepy. These are very painful burns. These are the ones that we tend to have the most trouble with when working with patients on range of motion. We have to provide a lot of education and encouragement to get patients to work with us with these depths of burns. The healing time is less than two to three weeks. Again, from a therapy standpoint, there is not a significant risk of contracture. We need to educate patients on things that they need to do like on how to keep their burn wounds clean. Regardless of whether or not they listen to us, they tend to do just fine regardless.

Deep Partial Thickness

Figure 4 shows a deep partial thickness burn.

Figure 4. Example of a deep partial thickness burn.

It extends into the deep dermis and affects both the hair follicles and glands. It is going to be a yellow or white color, and when you press and release, it is going to be slow to blanch, if at all. There may be blistering, and it is going to be fairly dry. Patients are going to complain about pressure and discomfort. There may be some pain especially along the edges of the wound. You can see in this picture that the center of the wound is the deep partial thickness burn because it is white, and then along the edges it is that pink very red color. Often times that will be a little bit more superficial, and that is going to be the painful areas. The healing time is three to eight weeks especially with the deep partial type. This is typically the healing time if you do not get a skin graft. They are mostly going to heal with scarring and contractures so this is one of the populations that we really want to be educating as to the importance of range of motion and being proactive with their burn wound management. Skin grafting may be necessary to avoid some of these problems, and that will be a surgeon's call based on their expertise.

Full Thickness Burns

The last one is going to be your full thickness burns (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Example of a full thickness burn.

This is going to extend through the dermis. Usually, the wounds are going to be stiff and white or brown colored. When you touch them they are not going to blanche. They are just going to stay the same color because the burn has gone through the blood vessels. There is no blood to that area so there is going to be no blanching. They are a leathery texture, typically very dry, and usually painless. The dermal plexus of the nerves have been destroyed so many times they have no pain. If it does not hurt, that means it is a very deep burn, and it is likely going to require surgical intervention. It takes a very long time for this to heal, and it is going to heal with contractures and scar formation.

Healing

Eshcarotomy

One of the treatment options we have, especially for significant burns or circumferential burns, are going to be eshcarotomies. This combats burn-induced compartment syndrome. The indications for this are full thickness burns, circumferential burns, increasing edema, and loss of pulses. This is usually sufficient to maintain tissue perfusion. This is something that we often see during the initial period, usually in the first 72 hours. Many patients that required this were trying to light barbecues with gasoline, and it would flash up and burn them. They would end up with burns circumferentially around their forearms and their hands. We would take them to the ICU and monitor them closely. They would get pulse checks done every hour, especially at the palmar arch. The palmar arch is what supplies blood to the fingers. If not monitoring this, the client could lose blood flow to the fingers. We have had people lose fingers and hands because of this. So if you are ever in this situation, make sure that the nurses are checking palmar arch not just the radial arch or the radial artery. Their arms also need to be elevated to make sure that the edema is out of that area as possible. If it is a full thickness burn that means that elastin is gone in the skin. There is nowhere for that extra swelling to go so this is when an eshcarotomy is performed to make sure that there is still blood flow capable of getting down to the hand and the digits.

Fasciotomy

Another issue we can have, especially with large burns and people getting a lot of fluid during the resuscitation period, is that eshcarotomies are not always enough. The amount of fluid that a client receives during a resuscitation is oftentimes dependent upon how big the burn is. If the client has a very significant burn, they are going to be getting liters of fluid an hour. This is an extraordinary amount of fluid that can fill up those compartments. In these cases, they would do a fasciotomy. Figure 6 shows an example of a fasciotomy of the hand.

Figure 6. Example of a fasciotomy.

They cut through the eshcar, which is the eshcarotomy, and through the fascia to open up the compartment to allow perfusion to occur into the digits and the hand. Your contracture risk with the full thickness is high, but if you have an eshcarotomy, I believe it is about four times the contracture risk. With a fasciotomy, it is eight times the contracture risk. They are especially hard to heal. When we know that someone has had an eshcarotomy or a fasciotomy, we provide an increased amount of education. Compliance is one of our biggest issues with this patient population.

Superficial and Superficial Partial Thickness Burns

Superficial and superficial partial thickness burns are going to heal by re-epithelization, not scarring and contracture. Formulation of granulation tissue over the open wound allows the re-epithelization phase to take place. Epithelial cells will migrate across the new tissue, and form a barrier between the wound and its environment. This is the same thing as your normal wounds; it is going to heal from the edges in. Dermal appendages such as the hair follicles, sweat glands, and sebaceous glands are the main cells that are responsible for the epithelization phase of wound healing. These are still intact with the superficial and superficial partial thickness burn injuries. They advance in a sheet across the wound site, proliferate at its edges, and they cease movement when they meet in the middle. It is like your typical wound healing.

Deep Partial and Full Thickness Wounds

Deep partial and full thickness wounds these are going to heal by contraction and scarring. it is a high risk of scar contracture, hypertrophy with the dermal wound healing, and a very high concern for rehabilitation. The sweat glands, hair follicles, and the nerves are not able to form. With the lack of those items, the wound and the resulting healing scar are not able to control temperature, especially during the summer and the winter months. They are going to have a rough summer or winter for the first time because their bodies are still adjusting on how to regulate their body temperature without the hair follicles, nerves, and the sweat glands. They need a lot of education to make sure they understand what is expected because many patients have no idea what to expect. it is very new.

Skin Versus Scar

Skin is made up of collagen, elastin, and ground substance. It can elongate up to 60% when stress is applied to it. The other side of this is the scar. It is mostly made up of collagen and an altered ground substance. It only elongates 16% when stress is applied. There was a study done on rats where stress was applied six hours a day. It showed a length change in young scar. However, if there was no stretch or stretch stress was added after many months, there was almost no change even after a month of tension treatment. With this population, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. We have to start from the beginning with compliance. Making sure that they understand the ramifications of doing the exercises that we give them. It goes such a long way.

Hypertrophic and Keloid Scarring

Some of the scarring that we see besides just your normal scarring are going to be hypertrophic and keloid scarring (see Figure 7).

Figure 7. Types of scarring.