Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to identify a patient's relevant past medical history, occupational profile, and occupational performance deficits in order to document and evaluate and develop long-term goals for a patient with chronic pain.

- After this course, participants will be able to recognize effective documentation practices including use of medically necessary language, measurable goal setting, and use of functional outcomes.

- After this course, participants will be able to review a pain management case study and list effective occupational therapy interventions and strategies to use to address identified performance deficits.

Thank you for being here with me today. I am excited to speak with you about lifestyle management services for treating, documenting, and billing effectively for pain.

Lifestyle Management Strategies for Chronic Pain

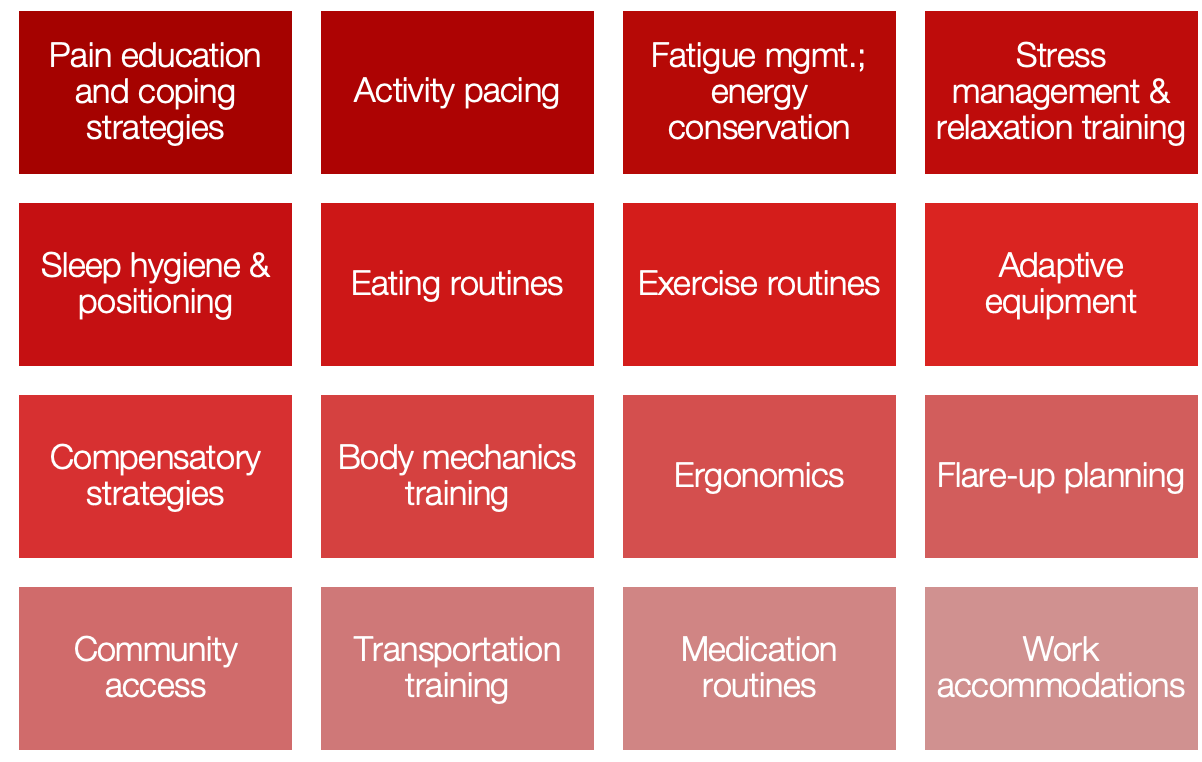

I want first to review overall lifestyle management strategies for chronic pain. Figure 1 shows an overview of the typical OT interventions used in a lifestyle redesign approach depending on what is identified in the evaluation as a patient's performance deficits. We tailor the process accordingly.

Figure 1. Overview of specific OT interventions used in lifestyle design.

LRD Chronic Pain Management Program

In our retrospective clinical efficacy study, Lifestyle Redesign® for Chronic Pain Management: A Retrospective Clinical Efficacy Study, my team and I evaluated the impact of a lifestyle-based occupational therapy approach for individuals living with chronic pain. We included 45 patients with diagnoses that reflected common, complex presentations in outpatient practice, including lumbago, myalgia/fibromyalgia, and complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS). On average, participants completed nine occupational therapy sessions over an 18-week period, during which we implemented Lifestyle Redesign® principles to build health-promoting habits and routines tailored to each person’s performance deficits and goals.

Our objective was to determine whether a structured lifestyle management approach could meaningfully affect function and quality of life across varied chronic pain conditions. By standardizing the frequency and duration of intervention while allowing for individualized content, we were able to examine outcomes across a heterogeneous chronic pain cohort and demonstrate feasibility and clinical relevance for everyday OT practice (Simon & Collins, 2017).

Lifestyle Redesign®

Lifestyle Redesign® is the process of acquiring health‑promoting habits and routines in daily life (Jackson et al., 1998). In my practice, I use Lifestyle Redesign® to help clients intentionally build and sustain routines that support function, reduce symptom burden, and align daily activities with their health goals.

Outcomes for Pain and Mental Health LRD Programs

In this program, I administer a core set of outcome measures to capture change in function, pain, and psychosocial health. These include the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM), the RAND SF-36 Quality of Life, the Brief Pain Inventory, and the Pain Self-Efficacy Scale. Depending on each participant’s presentation, I also incorporate condition- or mental health–specific tools such as the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire, Beck Depression Inventory, Perceived Stress Scale, and the PHQ-2 or PHQ-9. This combination allows me to track individualized occupational performance alongside standardized indicators of pain severity, interference, quality of life, and self-efficacy.

Study Results

In our retrospective study, I observed meaningful improvements across quality of life, self-efficacy, and occupational performance following Lifestyle Redesign®.

On the RAND SF-36, participants reported fewer role limitations related to both physical health (improving by 20.16 points) and emotional problems (improving by 25.27 points), along with higher social functioning (improving by 15.23 points). Pain self-efficacy increased by 4.46 points, reflecting greater confidence in managing symptoms. On the COPM, mean performance improved by 2.02 points and satisfaction by 2.78 points—changes that meet or exceed minimal clinically important thresholds. Brief Pain Inventory data showed modest reductions in pain severity and interference, indicating incremental but meaningful symptom relief alongside functional gains (Simon & Collins, 2017).

Taken together, these findings reinforce my clinical experience: Lifestyle Redesign® can significantly enhance quality of life, self-efficacy, and functional abilities for people living with chronic pain. Lifestyle modifications, when embedded into daily routines, are a practical and effective way to manage chronic conditions and improve overall well-being.

Documenting Lifestyle Management Interventions for Pain: Evaluation and Treatment Notes

There is evidence to support that these interventions work with that background information. Still, as a profession, we need to make sure that we can document and bill effectively to justify these services.

Evaluation

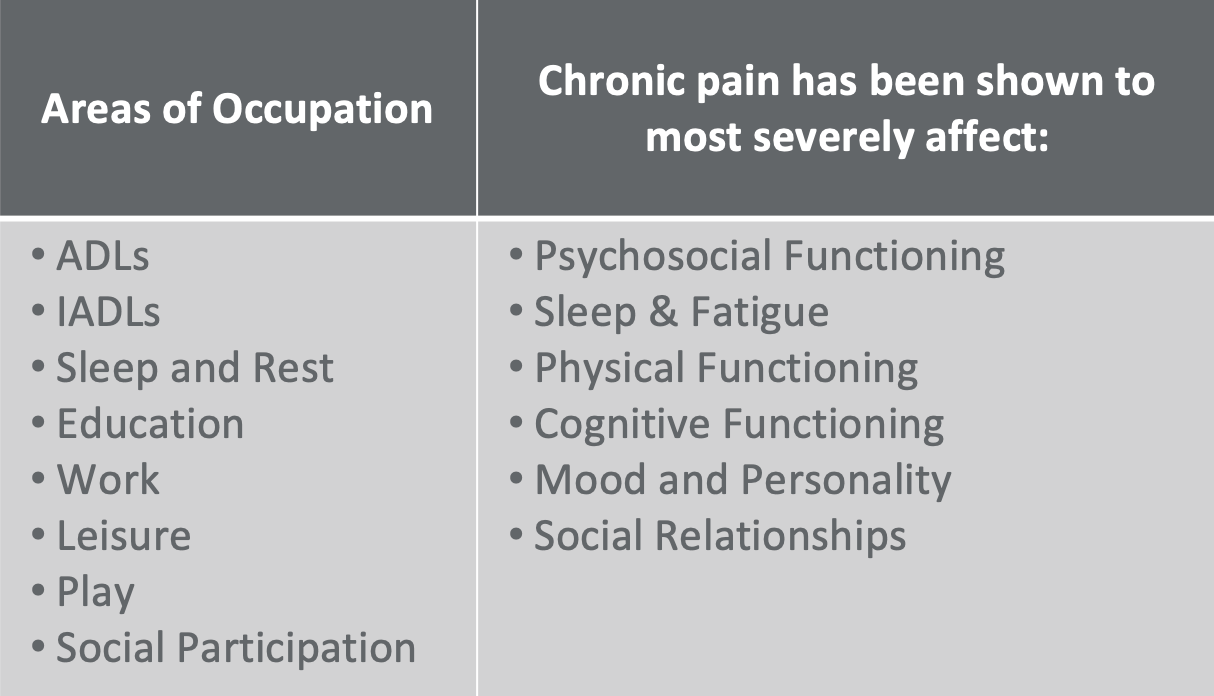

Next, we will look at the evaluation and treatment process and how to document the lifestyle management interventions for treating chronic pain. The evaluation process outlined in Figure 2 shows the areas of occupation and the most severely affected areas.

Figure 2. Areas of occupation that are affected by chronic pain.

In my evaluations, I make a point to understand how chronic pain affects each area of occupation so my documentation reflects those known impacts. Guided by the OT Practice Framework, I look for changes in psychosocial functioning, sleep and fatigue management, physical function, cognitive performance, mood, personality, and social relationships. Recognizing these patterns is only the first step; I also document the rationale and purpose behind each observation so the record clearly supports skilled OT intervention and links impairments to functional outcomes and goals.

Barriers to Chronic Pain Self-Management

In my evaluations, I systematically screen for barriers to chronic pain self-management because they shape prognosis and the practicality of recommendations. I note when social support is limited or resources such as finances and transportation are constrained. I assess depression and stress, as these often co-occur with pain and influence engagement. I look for ineffective or absent self-management strategies, competing life priorities and time constraints, and patterns of activity avoidance driven by fear of exacerbation. I also examine whether strategies have been tailored to the person’s needs and whether they can be maintained over time. Finally, I document relevant physical limitations. Recording these factors helps me individualize intervention, set realistic goals and timelines, and provide a clear rationale to payers when rapid progress is unlikely (Bair et al., 2003).

Evaluation: Occupational Profile & Medical History

In the medical history, I document the client’s story of pain over time, noting how symptoms have evolved and how they influence current function. I review comorbidities—especially mental health conditions—and record other accompanying symptoms beyond pain. I ask about known triggers and explore possible ones, including photophobia, phonophobia, osmophobia, and aura; posture-related factors; diet; menstrual cycle; temperature changes; stress; skipped meals; computer use; air quality; too much or too little sleep; and too much or too little physical activity. I contrast exacerbating with alleviating activities, and I capture pain location, duration, intensity, frequency, patterns, and recent flares. I also review medications for efficacy and side effects and note any past or current therapies for pain.

I assess daily habits, routines, and roles, distinguishing between “good” and “bad” pain days to understand variability in functional ability. I document the living situation and home environment, paying attention to safety, physical barriers, and available supports.

In the occupational profile, I record background information, social supports and resources, interests, and barriers such as poor self-awareness or catastrophizing, alongside existing self-management skills that can be leveraged. I clarify the patient’s goals and establish a prior level of performance—sometimes pre-injury and often including pre-existing chronic pain levels—to provide a baseline for measuring progress.

Evaluation: Client Factors Affecting Occupational Performance

In this part of the evaluation, I examine the client factors that influence occupational performance.

I begin with values, beliefs, and spirituality, noting cultural, societal, or religious perspectives that may shape the pain experience and willingness to engage in treatment. I ask whether spiritual practices support coping or whether pain interferes with participation. I also listen for beliefs about pain that may indicate catastrophizing or a sense of helplessness, and I document these as potential barriers to address.

I assess mental functions, including higher-level cognition and executive function, attention, focus, concentration, and memory. Because persistent pain can be cognitively taxing, I also look for difficulty establishing habits and routines, and I consider energy, drive, and sleep quality.

I evaluate psychosocial and coping factors—stress, anxiety, depression, and self-efficacy—and I make explicit the two-way relationship between stress and pain. When indicated, I coordinate with other providers to ensure these factors are addressed alongside OT.

I review body structures and functions relevant to the nervous and musculoskeletal systems, observing posture, fall risk, balance, joint mobility and stability, and muscle power, tone, and endurance. I note when pain contributes to sedentary behavior and deconditioning.

Finally, I assess sensory functions with attention to pain at baseline and with activity, patterns throughout the day, and sensitivities to light, sound, or temperature. I recognize that identifying a true “baseline” can be difficult for many clients and document this uncertainty to guide goal setting and re-evaluation (American Occupational Therapy Association, 2020).

Evaluation: Occupational Performance Deficits

In this stage, I identify occupational performance deficits across OT Practice Framework categories to understand how pain limits participation.

For ADLs and self-care, I assess bathing, toileting, dressing, feeding, mobility, hygiene, and sexual activity. For IADLs, I review caregiving, communication, driving, health management and maintenance, home management, meal preparation, spiritual practice, shopping, and medication management. I also evaluate rest and sleep, including difficulty falling asleep, staying asleep, returning to sleep after waking, and pain during sleep or upon waking.

Within health management, I document eating and exercise routines, medication management, self-regulation, symptom and condition management, and communication management. For education and paid or unpaid work, I examine job performance and maintenance, employment interests and pursuits, and volunteer exploration. Finally, I look at leisure/play and social participation, including play or avocation engagement and family, peer, and friendship participation (American Occupational Therapy Association, 2020).

As I conduct this review, I collect measurable baselines to anchor long-term goals. If meal preparation is difficult, for example, I determine the current assistance level, how often help is required, and the client’s standing tolerance before pain is triggered. These concrete baselines allow me to set clear, functional targets and to track progress meaningfully over time.

Evaluation (Pain-Specific Tips)

In my evaluations, I document how emotional state influences both pain and function. I screen for depression, anxiety, and stress, and I note any risk of social isolation. Because the relationship between stress and pain is bidirectional, I record whether a mental health comorbidity is present and whether the client recognizes when stress is unmanaged. When indicated, I initiate safety screening and coordinate with other providers.

I also capture the polarity of pain—what “good days” versus “bad days” look like—and how activity and function vary within and across days. Just as importantly, I reflect how occupational engagement affects pain, not only how pain limits function. This helps me link emotional factors and daily occupations to therapeutic goals and to the rationale for skilled OT intervention.

Evaluation: Clinical Decision-Making

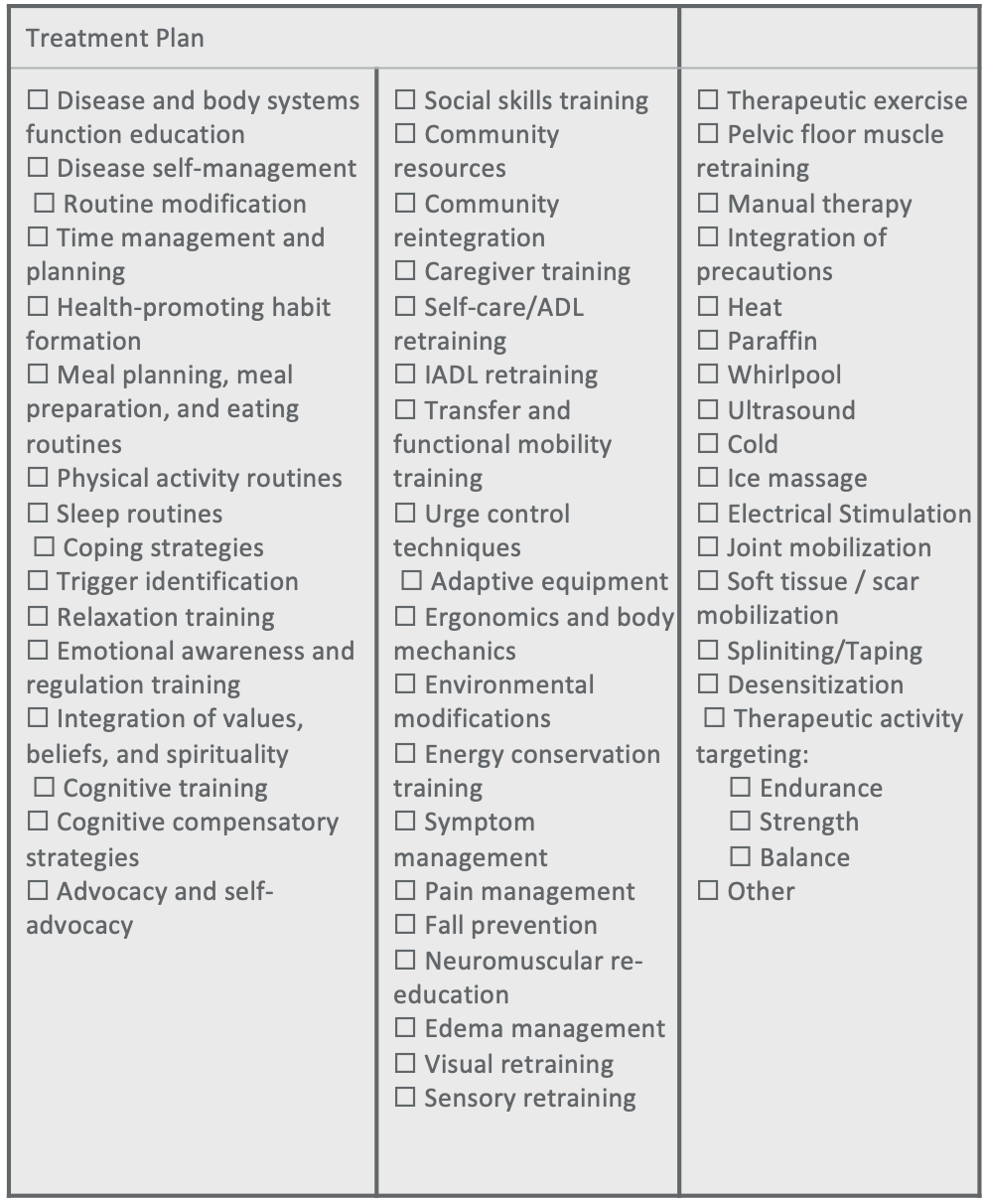

When choosing treatment plan options, relate each intervention to an ID’d performance deficit. With all of that information, think about the performance deficits and client factors influencing performance to develop this treatment plan (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Example of a treatment plan.

All of these options listed could be addressed in an OT treatment plan. However, be mindful of the occupational performance deficits you identified earlier in your assessment. Let's say the pain was impacting their ability to sleep effectively. You want to make sure that the treatment plan addresses sleep. You do not want a hole to be in the treatment plan process. You want to relate each intervention to an identified performance deficit.

Outcome Measures

In addition to the semi-structured interview and occupational profile, I administer standardized outcome measures to establish baselines for treatment planning and to document measurable change at re-evaluation.

For pain, I use the Visual Analog Scale, the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI), the Pain Catastrophizing Scale, the Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire, and the Pain Anxiety Symptom Scale. For mental health, I incorporate the Beck Depression Inventory, the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9 or PHQ-2), the Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-7), and the Perceived Stress Scale. To capture overall quality of life and occupation-centered outcomes, I rely on the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) and the 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36). These tools complement the clinical interview by quantifying pain severity and interference, psychosocial factors, and functional performance, which helps me tailor intervention and objectively track progress over time.

Pain Assessment

When diagnosis-specific detail is warranted, I supplement core measures with targeted assessments. For fibromyalgia, I use the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire–Revised (FIQR). For migraine, I select tools such as the Migraine Disability Assessment Test (MIDAS), Migraine-Specific Quality of Life (MSQL), the Headache Impact Test (HIT‑6), and the Headache Management Self-Efficacy Scale (HMSE). For low back pain, I often administer the Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability Questionnaire. I typically anchor my evaluations with the COPM and the RAND SF‑36, then add condition-specific instruments based on the client’s presentation and comorbidities to capture nuances that inform treatment planning.

Documentation, Billing & Reimbursement

How do we document the evaluation and bill and get reimbursed for that appropriately? As a review, this is just a summary of why documentation is so necessary.

Purpose of Documentation

In my documentation, I aim to do four things: communicate the client’s occupational history, experiences, interests, values, and needs; articulate the clinical rationale for providing occupational therapy and how it relates to outcomes; maintain a clear chronological record of status, services rendered, client response, and outcomes; and justify the medical necessity of skilled OT for reimbursement (Kearney & Laverdure, 2018). I treat the record as both a clinical tool and a narrative of lived experience, ensuring anyone who reads it can understand the client’s trajectory and continue the plan of care seamlessly.

I also make OT’s unique contribution visible. I focus on occupation, activity, and participation; I analyze environmental and contextual factors and document the modifications I recommend; and I use a holistic, biopsychosocial approach that addresses common comorbidities alongside pain. I incorporate OT-specific outcome measures, such as the COPM, to anchor goals and demonstrate change in domains central to our practice (Lagueux, Dépelteau, & Masse, 2018). Training and education are common in my sessions, but I explicitly tie these interventions back to occupational engagement so the link between what I teach and what the client does in daily life is clear and defensible.

Payer Guidelines for Documentation

In my notes, I explicitly link each intervention to the plan of care and the referring diagnosis so the medical necessity is clear. I demonstrate skilled OT by describing the specific analysis, education, training, and modifications I provide, and I always record the patient’s response—whether the activity provoked pain, whether cues were needed, and how performance changed in-session.

I document progress over time, including changes in pain levels, activity tolerance, and independence in daily activities, and I set concrete short‑term goals for the next visit. Finally, I select CPT codes that accurately reflect what I did in the session, ensuring alignment between services rendered and what is billed.

CPT Codes and Billing

- 97165/6/7 OT Evaluation (LOW/MOD/HI complexity)

- 97168 Re-Evaluation

- 97150 Therapeutic Group

- 97110 Therapeutic Exercise

- 97129 Cognitive Function

- 97530 Functional/Therapeutic Activity

- 97535 ADLs/Self-Care

- 97537 Community/Work Reintegration

- 97112 Neuromuscular re-education

- 97140 Manual Therapy

To get reimbursed for the services, we need to choose the correct CPT code that matches our session. For example, if we work on self-care and home management, we need to use that specific CPT code. Above are some of the standard CPT codes used for lifestyle management interventions for chronic pain. This is by no means all of the CPT codes that we have access to, but these are the more common ones. More often than not, I use the 97535 code, but I also use community/work reintegration and functional/therapeutic activity. If there is a cognitive impact from the pain, then use the cognitive function CPT code.

CPT® Occupational Therapy Evaluation “Occupational Profile”

- LOW 97165

- “An occupational profile and medical and therapy history, which includes a brief history including review of medical and/or therapy records relating to the presenting problem”

- MOD 97166

- “An occupational profile and medical and therapy history, which includes an expanded review of medical and/or therapy records and additional review of physical, cognitive, or psychosocial history related to current functional performance.”

- HI 97167

- “An occupational profile and medical and therapy history, which includes a review of medical and/or therapy records and extensive additional review of physical, cognitive, or psychosocial history related to current function performance.”

(Brennan, McGuire & Metzler, 2016)

In practice, I code each section of the OT evaluation to reflect what I actually document and the level of analytic complexity involved. Most clinicians are familiar with the evaluation complexity codes, but I still align them carefully with the client’s presentation and functional impact.

For the occupational profile and medical/therapy history, I assign low complexity when the case involves a recent injury or a shorter duration of pain with limited contributing factors. I use moderate complexity when pain is the primary issue but comorbidities are minimal and the review is more detailed. I reserve high complexity for histories with multiple interacting factors—physical, cognitive, or psychosocial—that substantially influence function and require extensive review and reasoning.

CPT® Occupational Therapy Evaluation “Occupational Performance”

- LOW 97165

- “An assessment(s) that identifies 1-3 performance deficits (i.e., relating to physical, cognitive, or psychosocial skills) that result in activity limitations and/or participation restrictions. “

- MOD 97166

- “An assessment(s) that identifies 3-5 performance deficits (i.e., relating to physical, cognitive or psychosocial skills) that result in activity limitations and/or participation restrictions.”

- HI 97167

- “An assessment(s) that identifies 5 or more performance deficits (i.e., relating to physical, cognitive or psychosocial skills) that result in activity limitations and/or participation restrictions.”

(Brennan, McGuire & Metzler, 2016)

Looking at occupational performance, this is the same thing. We need to make sure that we are coding low, moderate, or high appropriately by thinking about the number of identified performance deficits.

CPT® Occupational Therapy Evaluation “Clinical Reasoning”

- LOW 97165

- “Clinical decision making of low complexity, which includes an analysis of the occupational profile, analysis of data from problem-focused assessment(s), and consideration of a limited number of treatment options. Patient presents with no comorbidities that affect occupational performance. Modification of tasks or assistance (e.g., physical or verbal) with assessment(s) is not necessary to enable completion of evaluation component.”

- MOD 97166

Clinical decision-making of moderate analytic complexity, which includes an analysis of the occupational profile, analysis of data from detailed assessment(s), and consideration of several treatment options. Patient may present with comorbidities that affect occupational performance. Minimal to moderate modification of tasks or assistance (e.g., physical or verbal) with assessment(s) is necessary to enable completion of evaluation component.

HI 97167

Clinical decision-making of high analytic complexity, which includes an analysis of the patient profile, analysis of data from comprehensive assessment(s), and consideration of multiple treatment options. Patient presents with comorbidities that affect occupational performance. Significant modification of tasks or assistance (e.g., physical or verbal) with assessment(s) is necessary to enable patient to complete evaluation component.

(Brennan, McGuire & Metzler, 2016)

For the treatment plan, you identify what areas you are going to address and the treatment options based on their performance deficits. If there are only a few deficits, it may be low complexity; however, if there are a lot of different performance deficits, it may be more moderate or high.

For the final billing code of the evaluation, you use the lowest level of complexity identified in those three categories. For example, if the occupational profile was low complexity, but the occupational performance and clinical reasoning areas were moderate complexity, it would be billed overall as a low complexity evaluation.

Long-term Goal Setting

From the evaluation, I develop long-term goals that guide treatment. My priorities are to decrease pain—by reducing frequency, intensity, or flares—and to improve self-management skills such as recognizing and preventing trigger exposure, implementing pain-coping strategies, and using medications effectively. I also target client factor and environmental modifications to reduce functional deficits, decrease dependence on others, and improve activity tolerance.

I use outcome measures as evidence of improvement, not as goals themselves. For example, I would not set a goal to increase a COPM score by two points; instead, I write function- and occupation-based goals and then use COPM changes to document clinically meaningful progress.

Plan of Care Long-term Goals

I begin by identifying the area of focus, whether a specific body part, a cognitive domain, or a psychosocial factor. I then define the primary impairment, such as pain, reduced strength or ROM, impaired balance or endurance, relevant stressors, or skill deficits. From there, I establish a measurable impairment goal using objective metrics like VAS, COPM, ROM, or other numeric targets. I anchor the plan in a functional activity—dynamic, real-world tasks such as cooking, dressing, driving, or work-related responsibilities—and set a clear target performance, specifying distance, duration, frequency, or product/output. I articulate the rationale for each goal, emphasizing its impact on self-care, reducing caregiver burden, improving functional independence and safety, and supporting community reintegration. I also set a target timeframe—such as 2 weeks, 4 visits, or 10 visits—to guide re-evaluation and meet payer expectations. When I write long-term goals, I ensure clarity of focus by selecting the functional activity most likely to improve outcomes and by defining the target performance in the context of the patient’s baseline. I explicitly connect the impairment to the functional objective—for example, targeting sleep routines to improve nervous system regulation and reduce migraine triggers—so that the purpose and expected benefits are clear and measurable.

Goal Setting Template:

- In time frame, Pt will improve functional performance deficit by improving client factors/reducing limitations, as evidenced by measurable target performance (baseline measurement), to address management of diagnosis.

This is a template that I put together that can be used to write long-term goals to make sure you are touching all of those components.

Goals: Examples

- In 12 sessions, Pt will improve participation in cleaning home management IADLs by improving endurance and energy mgmt., as evidenced by increasing independence from moderate assistance to minimal assistance to address management of fibromyalgia.

- In 8 sessions, Pt will improve sleep/rest IADLs by improving sleep wind-down routines and positioning supports, as evidenced by engaging in a relaxing sleep wind-down routine 5/7 nights, to address management of low back pain (baseline: engaging in sleep wind-down routine 1/7 nights).

- In 10 sessions, Pt will improve participation in work by reducing exacerbation of stress, as evidenced by implementing x1 relaxation technique per day in the workplace, to address management of chronic migraines (baseline: not using stress management coping strategies).

Using this template, I provided a few examples. In the first one, there is a target timeframe. The way we will measure progress is evidenced by their increased independence in home management tasks from moderate assistance to minimal assistance. This focuses on helping them manage their fibromyalgia symptoms better.

Another one looks at sleep routines. The patient will improve their sleep routines by improving their wind-down habits and incorporating positioning supports within eight sessions. We ask the patient to engage in a relaxing sleep wind-down routine five out of seven nights to manage their back pain better.

The final one looked at the client's baseline where they were only engaging in relaxing activities one night a week. By adding this, it makes it very easy to measure progress. When you go to re-evaluate a patient, you can ask them, "How many nights are you engaging in a sleep wind-down routine?" I cannot emphasize that baseline measurement component enough.

Treatment Note: Demonstrating Skilled Intervention and Medical Necessity

I included some tools and resources that you guys can use. These are some of the verbs that I think help to demonstrate skilled interventions that we use as OTPs.

- Verbs:

- Added

- Assessed

- Cued (verbal, proprioceptive, manual, etc.)

- Customized

- Demonstrated

- Developed

- Educated

- Evaluated

- Facilitated

- Implemented

- Instructed

- Maximize/increased

- Minimized/reduced

- Modified

- Monitored

- Prevented

- Progressed

- Provided

- Recommend

- Trained

- Collaborated

- Engaged

I have included verbs like "modified" and "trained." "We provided education," or "We monitored the patient during an activity." These are some examples. This is by no means a hundred percent comprehensive list, but this is something that you can refer back to strengthen your documentation as you are writing a treatment note.

- Examples:

- Independent carry-over of

- Patient presents with decreased participation due to

- Patient was assessed/measured/analyzed for…

- Patient was provided with verbal/tactile/proprioceptive cues to…

- Patient was instructed and received training for…

- Activity tolerance/efficiency and/or task effectiveness (use length of time)

- Therapist engaged client in….. problem-solving activity

- Therapist facilitated client exploration/analysis of…daily living skill

- Therapist trained/educated/instructed…..compensatory activity to increase independence

- Therapist assessed client’s ability to…

- Therapist demonstrated… technique/strategy for…

- Therapist modified/added…

- Therapist provided client with resources for...

These are also some of the taglines that you can use to report on what you have done in a session. For example, "The patient was assessed to determine activity tolerance of writing," "Trained in how to use a piece of adaptive equipment to make writing less painful, and then was "Reassessed while using that piece of adaptive equipment." "The patient reported improved tolerance." These are examples of taglines that you can add to your daily note documentation.

Now, I am going to go over a few case examples.

Pulling It All Together: Case Example 1

Overview

I evaluated a patient diagnosed with carpal tunnel syndrome that is interfering with his ability to perform daily childcare responsibilities and computer-based work tasks. He denies any mental health comorbidities.

Based on the occupational profile and evaluation findings, there were no additional comorbidities reported. The case met criteria for a Low Complexity Evaluation (97165). There were two primary performance deficit areas identified, and both the performance considerations and clinical reasoning demands were low in complexity. With all three categories—comorbidities, performance deficits, and clinical decision-making—falling within the low complexity range, I appropriately billed this as a low complexity evaluation.

Treatment Note: Skilled Intervention

- OT trained patient in proper body mechanic techniques to improve neutral positioning of upper extremities during childcare IADLs to reduce risk for nerve impingement and exacerbation of carpal tunnel syndrome pain. Pt return demonstrated proper body mechanic technique by lifting a 15 lb exercise ball, 3x. Pt stated, “doing it this way does not trigger pain.”

- OT educated patient re: the risks of overactivity and prolonged repetitive activity participation on exacerbating carpal tunnel pain and trained patient in new pacing strategies to increase frequency of breaks during repetitive typing activities at work. OT recommended ergonomic equipment modifications that promote neutral hand and wrist positioning. Patient trialed use of x1 new ergonomic keyboard and reported reduced pain from an average of 8/10 during typing to 5/10.

These examples show how the treatment session was documented to demonstrate skilled intervention and highlight the CPT codes used. I trained the patient in proper body mechanics techniques and how to achieve neutral positioning during childcare tasks to reduce the risk of nerve impingement and the trigger of carpal tunnel syndrome pain. I am tying it back to that specific pain diagnosis, making that explicit connection.

After doing the training, I reported on the patient's response. "Patient returned demonstrated the proper body mechanic techniques." The way he did this was by lifting a 15-pound exercise ball three times and stating, "This does not trigger my pain." In addition to reporting on the patient's response and progress objectively, you can also include some of those subjective responses. Using the lifestyle management approach, patients are going to report a lot of subjective progress, like, "I am sleeping better," "I am managing my stress better," or "I'm able to tolerate this activity better." This all addressed the childcare component.

For work, I educated the patient about the risks of overactivity and repetitive strain and how that can exacerbate carpal tunnel syndrome symptoms. I trained him in new pacing strategies and different approaches to work tasks. In addition to that pacing training, I also recommended some specific ergonomic equipment and environmental modifications to implement into his computer workstation to improve the neutral position of his hand and wrist. He trialed the use of an ergonomic keyboard. While he was typing, he reported a reduction in his pain levels using the new adaptive equipment.

In that daily note component, you can see I am explicitly tying it back to the diagnosis and using skilled intervention language of education and training. I am also using the unique OT role of environmental modifications. I am also highlighting occupational engagement of childcare and work tasks.

I also report that patient's progress and outcomes of less pain with lifting and typing.

Treatment Session: Long-Term Goals

- In 12 sessions, Pt will improve participation in childcare IADLs by improving posture and body mechanics, as evidenced by increasing tolerance for holding his son from less than 1 minute to 3 minutes at a time, to address management of carpal tunnel syndrome.

- In 12 sessions, Pt will improve participation in work by improving ergonomic environment and activity pacing, as evidenced by increasing tolerance for typing from 2 minutes to 10 minutes, to address management of carpal tunnel syndrome.

The long-term goals focused on childcare and work participation. So using that same template, in 12 sessions, the patient will improve participation in childcare tasks by improving posture and body mechanics as evidenced by increasing tolerance for holding his son for less than a minute to three minutes. That is the target performance. We are providing training to help him improve his management of carpal tunnel syndrome. For the work goal, the patient would improve participation and tolerance for typing by improving his ergonomic environment and using a pacing approach.

These both address the management of carpal tunnel syndrome.

Treatment Session: CPT Codes Billed

- Total treatment time: 60 minutes

- 97535 ADLs/Self-Care – 35 minutes, 2 units

- 97537 Community/Work Reintegration – 25 minutes, 2 units

We billed a combination of 97535 and 97537 codes. I spent about 35 minutes with the client for childcare body mechanics training and then 25 minutes on the pacing and ergonomic components for engaging in work tasks. This is what I put on my billing sheet. The documentation I provided matches those two codes and what we did during the session. And then lastly, at the end of the treatment session, we set some short-term goals for him to work on based on the training and education provided during the session.

Short-term Goal Setting

- By next visit, patient will implement proper body mechanic techniques during childcare IADLs by practicing holding his son for 2 minutes, 1x/day.

- By next visit, patient will improve pacing during typing work tasks by increasing the frequency of breaks from 1x every 120 minutes to 1x every 45 minutes.

One of the short-term goals was that he was going to use proper body mechanic techniques during his childcare activities by practicing holding his son for two minutes at a time, once a day. This task is very measurable, and it is something that when you check in with the patient, he is going to be able to say if he completed it or not. The other goal was that by the next visit, the patient would improve his pacing during his work tasks by increasing his frequency of breaks from one time every two hours to one time every 45 minutes to prevent repetitive strain from prolonged use. We can tie this into the baseline measurement of only taking a break every 2 hours. We want to increase that frequency of breaks and see how that then impacts his pain.

Another potential short-term goal may have been, "Patient will incorporate the use of an ergonomic keyboard at his workstation." Did he acquire an ergonomic keyboard, implement using it into his workday, and did this affect his pain? These are examples of follow-up questions when you see that patient for their next session. "How did those short-term goals go?" "How did that impact your pain levels and symptoms?" You can see if they met those goals and problem-solve any barriers that might have come up.

This is what a treatment session would look like including the evaluation, follow-up treatment session, and short-term goal setting. Hopefully, this ties all of those pieces together and gives you some good examples of that.

Another case study will look at a patient's overall experience in OT, not just one treatment session or evaluation.

Pulling It All Together: Case Example 2 (Mark)

Overview

- 63 y/o male, high school teacher

- Dx: CRPS (Complex regional pain syndrome); Type 1 in bilateral hands

- Injury 5 years prior to OT treatment caused by repetitive motions at work

- Symptoms: aching & shooting pain

- Triggers: fine motor movements, stress

- Alleviating factors: deep pressure

- Other treatments: physical therapy

- Seen for initial evaluation and 19 treatment sessions

Mark is a 63-year-old high school teacher and was referred to OT to treat CRPS type one in bilateral hands. By the time he got to OT, he had been injured for five years, caused by repetitive motions at work. He was experiencing aching and shooting pain in both of his hands, and he did have some awareness about the triggers. Fine motor repetitive movements caused pain during heightened stress, particularly at work or in his relationship. He identified that deep pressure was helpful for him, and when he was not doing work-related tasks or on vacation, his pain levels were reduced. There is some awareness that stress triggered his pain and that enjoyable activities relieved it. He worked with both occupational and physical therapy and a pain management physician. He also used medications to help manage his pain symptoms.

Functional Impact

I evaluated Mark and identified several functional impacts related to carpal tunnel syndrome. His symptoms interfered with work productivity and daily functional performance, including handling papers, handwriting, and typing—core tasks in his teaching role. He reported difficulty pacing himself throughout the workday and challenges with stress management. He also had reduced driving tolerance; prolonged gripping of the steering wheel during his long commute was a consistent trigger.

I saw Mark for his initial evaluation followed by 19 treatment sessions. We began with weekly sessions to establish foundational skills and pain management strategies. As his skill set improved and he became more independent in self-management, I transitioned the schedule to lower-frequency visits (every two to three weeks) to support maintenance and continued progress. At the time of the evaluation, Mark’s primary concerns centered on work performance, task pacing, stress regulation, and driving tolerance, all of which informed our treatment plan and goal setting.

Lifestyle Management Areas

I focused treatment on practical, real-world strategies that would help Mark function at work and manage symptoms across his day. I began with compensatory strategies and adaptive equipment to improve efficiency with paper handling, handwriting, and typing. I adjusted his workstation and introduced ergonomic supports, trialed alternative input devices, and taught wrist-neutral positioning with micro-breaks to reduce strain. I also addressed pacing by helping him batch tasks, schedule brief recovery periods, and distribute hand-intensive activities more evenly to prevent flare-ups.

Driving and commuting were significant triggers, so I modified his routine to reduce symptom provocation. We transitioned him to taking the train, which eliminated the early-morning flare associated with gripping the steering wheel. During the commute, he practiced relaxation techniques or read for leisure to set a calmer tone for the day.

Because stress amplified his pain, I integrated stress and anxiety management throughout the plan. I taught relaxation techniques—including diaphragmatic breathing, mindfulness, and brief body scans—to promote parasympathetic activation. He practiced these daily and reported meaningful reductions in pain. We also worked on avoiding unnecessary stressors by identifying modifiable triggers and simplifying his schedule where possible.

Given his report that deep pressure reduced symptoms, I helped him establish a graded exercise routine that incorporated safe, heavy-work activities such as weightlifting while maintaining wrist-neutral form. We paired this with pacing strategies so he could build strength and tolerance without exacerbating symptoms.

Finally, I incorporated cognitive-behavioral strategies to address negative self-talk. Together, we identified unhelpful thought patterns and replaced them with more balanced, functional coping statements. This combination—compensatory techniques, ergonomic modifications, pacing, commute changes, relaxation training, targeted exercise with deep pressure, and CBT-informed strategies—formed a comprehensive, lifestyle-focused plan that supported his work productivity and overall well-being.

Long-term Goal Setting

- Practice writing a goal to address his functional deficits at work

- In 10 sessions, patient will improve performance at work by improving tolerance for computer activities, as evidenced by implementing use of adaptive equipment during typing and mousing to decrease CRPS pain.

Outcome Measures

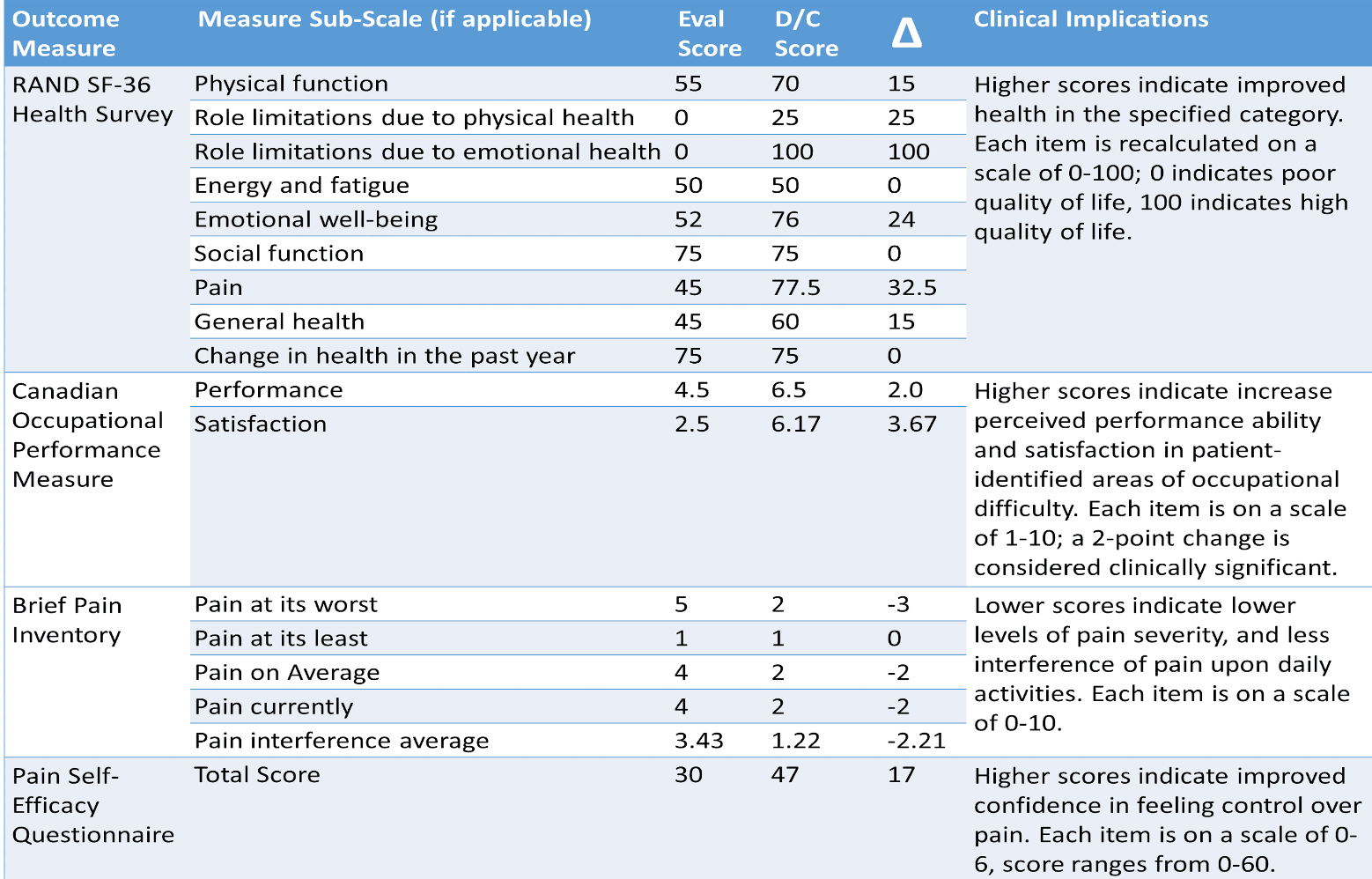

And the evidence or the outcome measures that demonstrate progress are all listed in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Chart of outcome measures for Mark. Click here to enlarge the image.

We used the RAND SF Quality of Life. You can see his baseline, discharge scores, and changes. Higher scores indicate improvements in any one of these categories. On the COPM, his overall performance and satisfaction scores improved by at least two points, which is lovely to see. For the Brief Pain Inventory, his average and worst/least pain levels improved, and the pain interference was reduced. So, the impact of his pain on his ability to do his daily activities improved after OT treatment. Finally, his Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire score improved from the initial evaluation to discharge. The higher scores demonstrate a higher self-efficacy.

Hopefully, these examples help tie in all of that information for each of you.

Questions and Answers

I know you work with some other disciplines. How does this type of treatment work across disciplines?

This is a significant part of our process in OT. The patients I am working with often see at least one other discipline, whether it is their physician, physical therapy, or pain psychology. Pain affects a person's overall health and wellbeing, and using an interdisciplinary approach is essential. I like to understand what services the patient is receiving outside of OT. Another vital role that we have as OTPs, focusing on that behavior change piece, is to help patients integrate any recommended interventions by others. For example, a doctor may have prescribed them medication, but they are not utilizing it effectively or consistently. We can help them with medication management and incorporate this into a daily routine. Perhaps the PT has given them an exercise routine, and we can help them implement that routine into their everyday life. It is essential to document these interactions as many insurances recognize the value of that interdisciplinary care.

References

American Occupational Therapy Association. (2020). Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process (4th ed.). American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74(Suppl. 2), 1-87.

Bair, M.J., Robinson, R.L., Katon, W., Kroenke, K. (2003). Depression and pain comorbidity: a literature review. Archives of Internal Medicine, 163, 2433-2445.

Jackson, J., Carlson, M., Mandel, D., Zemke, R., & Clark, F. (1998). Occupation in lifestyle redesign: The well elderly study occupational therapy program. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 52(5), 326-336.

Kearney, K. & Laverdure, P. (2018). Guidelines for documentation of occupational therapy. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 72, 1-7.

Lagueux, E., Dépelteau, A., & Masse, J. (2018). Occupational therapy’s unique contribution to chronic pain management: A scoping review. Pain Research and Management.

Phillips, C. J. (2009). The cost and burden of chronic pain. Reviews in pain, 3(1), 2-5.

Simon, A. U., & Collins, C. E. (2017). Lifestyle Redesign® for chronic pain management: A retrospective clinical efficacy study. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 71(4), 7104190040p1-7104190040p7.

Citation

Reeves, L. (2021). Understanding lifestyle management services for treating pain: Documentation and case study examples. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5492. Available at https://OccupationalTherapy.com