Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Using Adult Learning Theory To Enhance Coaching Practice And Parental Self-Efficacy, presented by Pam Smithy, MS, OTR/L, and Rhonda Mattingly Williams, EdD, CCC-SLP.

*Please also use the handout with this text course to supplement the material.

Learning Outcomes

After the course, participants will be able to:

- Analyze indicators of positive parental self-efficacy and how intervention outcomes are impacted.

- Analyze effective coaching strategies based on adult learning theory across therapy disciplines to support parents in implementing effective strategies.

- Examine specific practices within coaching grounded in adult learning theory to support parental self-efficacy across disciplines.

Introduction

Dr. Rhonda Mattingly Williams: Thank you so much, and welcome. It's great to be here with you today. As the title implies, we are going to talk about self‑efficacy. It is essential to define this clearly so we all understand what we mean.

Self-Efficacy

Definition

Dr. Rhonda Mattingly Williams: Self‑efficacy is the belief in one’s own capabilities to organize and execute the actions required to manage future situations. It is not the same as self‑esteem.

Self-efficacy differs from self-esteem in that self-esteem is a more general, fluctuating mental state about how we feel about ourselves overall. Self‑efficacy is much more specific: we believe that we can handle or perform in a particular situation.

A critical feature of self‑efficacy is that it can be very high in one area and low in another. For example, a neurosurgeon might have extremely strong self‑efficacy when it comes to performing a complex brain surgery, yet feel very little self‑efficacy in their role as a parent. Keeping this in mind is crucial when we work with families. A caregiver who is highly competent and confident in many aspects of life may still feel very unsure of themselves when it comes to feeding, caring for, or making decisions for their medically complex child.

Theoretical Framework

Dr. Rhonda Mattingly Williams: Self‑efficacy, as a theoretical framework, comes from Bandura’s social cognitive, or social learning, theory. That theory proposes that people learn by watching others. It involves the cognitive processes of attention, retention, reproduction, and motivation. Instead of relying solely on direct experience, we also learn through the models we observe.

In this framework, there is a dynamic interaction between personal factors, our environment, our behavior, and our history—what we know about everything that has happened to us. Bandura referred to this as reciprocal determinism. In other words, all of these elements interact with each other, and self‑efficacy develops within that ongoing interaction as part of social cognitive theory.

Development of Self-Efficacy

Dr. Rhonda Mattingly Williams: Self‑efficacy develops from several different sources: performance experiences, vicarious experiences, imagined experiences, social persuasion, and our physical and emotional states. Let me talk through these a bit more.

Performance experience is one key source. When we have had success in a particular area in the past, it tends to strengthen our sense of self‑efficacy in that area. On the other hand, past failures can weaken our confidence in our ability.

Vicarious experiences also matter. When we see other people succeed, it can help us feel that we, too, might be able to succeed. Watching someone else “like us” manage a task can be compelling.

Social persuasion is another influence. Encouragement from others can increase our confidence, while discouragement can undermine it. Research dating back to the 1980s suggests that the more credible the person is who encourages or discourages us, the more strongly we tend to internalize their message.

Imagined experience refers to our own ability to picture ourselves succeeding. That is how it is described on the slide, but I also want to point out that sometimes we get caught in imagining failure instead. We replay negative images or outcomes over and over, and that can also significantly affect our self‑efficacy.

Finally, physical and emotional states play a huge role—this is true for everyone, but I am especially thinking about parents here. When we face a task, how we feel physically and emotionally will shape our sense of what we can handle. For a parent of a child with delays, disorders, or other diagnoses, those physical and emotional states are almost always part of the picture and will strongly influence self‑efficacy.

You can see some concrete examples on the chart. For instance, someone who has successfully changed the diapers of their first three children will probably feel confident doing it again. A PT student who fears public speaking but sees a classmate manage it well might think, “If they can do it, maybe I can too.” I will let you look through the rest of those examples, but the main point is that all of these factors—successes, failures, what we see others do, what we imagine, what people tell us, and how we feel—are the things that either build our self‑efficacy up or tear it down.

Perspective Associated with a Strong Sense of Self-Efficacy

Pam: When we think about a strong sense of self‑efficacy, we are really talking about the perspective people bring to difficult situations. When we perceive a difficult challenge as an opportunity and look forward to the growth and learning that can come from it, we strengthen our self‑efficacy.

With that stronger sense of self‑efficacy, we tend to engage more fully and with greater curiosity, especially in target activities that feel meaningful. That kind of engagement builds lasting dedication and persistence as we work toward our goals and pursuits. It also helps people bounce back more easily after a failure or an obstacle. They have a sense that they can get back up and try again.

Perspective Associated with A Decreased Sense of Self-Efficacy

Pam: When we examine behaviors associated with a decreased sense of self-efficacy, we often observe people avoiding tasks they perceive as challenging. They may view difficult situations as being far beyond their capacities and decide not to attempt them at all. Their attention tends to focus on adverse outcomes and past failed attempts, and over time, they lose confidence in their personal abilities.

Parental Self-Efficacy

Pam: We know that parent self‑efficacy—the parent’s belief in how they can influence their child’s health, care, and success‑promoting behaviors—is really at the heart of what we are talking about today. The question becomes: how can we build this?

So, what does the literature tell us about it? This is where I turn it over to Rhonda for that deep dive.

Literature Review-Parental Self-Efficacy

Dr. Rhonda Mattingly Williams: Well, the literature tells us a lot about it.

Negative Influences on Parental Self-Efficacy

Dr. Rhonda Mattingly Williams: The literature indicates that numerous negative influences affect parental self-efficacy, and honestly, this first slide could almost be a T-shirt.

Stress is at the top of the list. And what parent—whether or not their child needs therapeutic intervention—does not experience stress? Stress is simply part of life. Fatigue is another major factor. When I am exhausted, there are moments when I feel, “I just can’t do this; I don’t have the capacity.”

Depression is a culprit in so many debilitating experiences for human beings, and anxiety is right there with it. Child behavior problems also play a role. I always say “behavior problems” with quotes in my mind, because while they may be perceived as “just behavior,” we really know that behavior is a form of communication. It is a way of saying, “Help me with this,” or “Something is not working for me.”

Lower economic status is another influence. If I am constantly worried about paying my bills on top of trying to be a parent who can help my child, that is going to hurt my sense of efficacy. And then there is self‑blame. Pam and I have talked about this many times. It is not always just internal self‑blame; sometimes it is triggered by the person who walks up to you in Target or another store and says, “If you would do it this way, your child wouldn’t be having a meltdown,” or “Why can’t you be a better parent?” Such comments can have a profoundly negative influence. Self‑blame can become a way of coping: “I messed up, I can’t do this, there’s no point in trying.” All of these factors together can significantly erode a parent’s self‑efficacy.

Parenting Experiences: The Medically Complex Child

Pam: When we look at parenting experiences, especially for those medically complex children we so often have on our caseloads, the literature paints a very consistent picture.

Parents report poor communication and coordination among healthcare providers, and that breakdown often falls squarely on them. It causes frustration and distress—their stress and anxiety increase when services are lacking or when providers are slow to respond. Parents also describe the stress of constantly having to chase support—trying to obtain services, find answers, and access information about their child, the diagnosis, and what is coming next week.

There is often an intense sense of helplessness and powerlessness, as well as mistrust, all tied to a perceived lack of communication and compassion from healthcare providers. Additionally, parents are exhausted and frustrated by the difficulty to accessing the services their child needs.

Dr. Rhonda Mattingly Williams: This is what the literature tells us parents of medically complex children are experiencing, and it connects directly back to our previous slide on the negative effects on self‑efficacy. We know this is a massive part of the population we all work with across disciplines, which is why the influence of parental self‑efficacy on outcomes is so essential to understand.

Influence of Parental Self-Efficacy on Outcomes

Dr. Rhonda Mattingly Williams: Parental self‑efficacy has been shown, in the work of Jones and Prinz, to impact parenting practices and, ultimately, child behavior. In other words, whether a parent has a strong or weak sense of self‑efficacy will influence how they carry out their parenting responsibilities, and that, in turn, affects the child.

Targeted improvements in parental self-efficacy have been associated with changes such as decreased aggressive behavior, increased compliance, and reduced irritability in children. The idea is that as we strengthen parental self‑efficacy, parents are better able to manage and respond to these behaviors.

In the study by Glatz and Buchanan, mothers with higher self‑efficacy demonstrated more positive parenting practices, which led to fewer behavior problems in adolescence. Paternal confidence did not influence parenting practice to the same degree, but child behavior still improved with positive parenting. Other studies have shown that positive parenting practices can also increase parental confidence over time.

Finally, higher parental self‑efficacy has been significantly associated with improved behavior outcomes in additional studies. So, suffice it to say, there is clear support in the literature that when we can help parents improve their self-efficacy, it has a direct impact on child outcomes and benefits the family as a whole.

Practices Positively Associated With Improved Parental Self-Efficacy

Pam: When examining what positively improves parental self-efficacy, several themes emerge.

When we focus on parental goals and provide caregivers with adequate time for hands-on practice during our sessions, self-efficacy increases. Structuring sessions so that there is a real opportunity to practice—not just listen—makes a difference. Providing opportunities for peer support also helps, as parents can see others facing similar challenges and feel less alone.

We know that motivational interviewing improves accountability. Providing information and experience related to topics that are directly applicable to daily life—such as play and communication—also supports parents’ confidence. Coaching that includes modeling, practice, feedback, and self-reflection helps parents develop the skills they need, making them feel more capable and confident in parenting these challenging children.

Dr. Rhonda Mattingly Williams: We will discuss coaching further later in the presentation, and we can also dedicate some time to motivational interviewing.

Motivational Interviewing

Pam: This is a patient‑centered approach that helps build intrinsic motivation for change. It is based on a vast body of work, as these authors have written numerous books on the topic. What I am providing here is a summary.

Principles

Pam: The four key principles are these. First, we express genuine empathy. Second, we help develop a discrepancy between the current behavior and the treatment goals. Third, we take an attitude of “rolling with” resistance rather than confronting it head‑on. And fourth, we support self‑efficacy in the patient or caregiver. When we engage in these activities, we are applying the principles of motivational interviewing.

Core Techniques

Dr. Rhonda Mattingly Williams: What are the core techniques of motivational interviewing? There are five that I want to highlight here.

First, we use open‑ended questions to encourage dialogue. We talk about this with our students across every discipline. If we ask a yes‑or‑no question, we are going to get a yes‑or‑no answer, which gives us only a tiny bit of information. Open‑ended questions invite the person to talk to us. For example, if a parent has mentioned that mornings are tough getting their child to daycare, I am not going to ask, "Do you have trouble in the morning?" or "Do you have trouble with feeding in the morning?" They have already told me that. Instead, I might ask, "Can you tell me more about what the mornings are like? What are you going through when you are trying to get your child ready?"

Second, we use reflective listening to show understanding. That might sound like, "It sounds like you really want your child to be more independent, but it is hard when time is short and you need to get out the door." I am not judging; I am letting them know that I hear them and appreciate their perspective.

Third, we offer affirmation through compliments or validation. For instance, "You have been really patient working with your child's routine. That kind of patience builds new skills and helps develop the outcomes you want to see." This is not generic praise, such as "Oh, you are doing a great job." It is specific and tied to what the parent has actually said or done.

Fourth, we use summaries to reinforce key points. For example, "Today we talked about how you would like your child to dress themselves independently. Mornings can be tough, and you're under a lot of pressure. You are open to trying some strategies, and you want to make sure that helping your child dress faster is something you can actually do." Summarizing reinforces what has been discussed and shows that we were listening.

Finally, we elicit change talk. As you may recall from earlier slides, we discussed how people can spiral into negativity when they are beaten down and exhausted. We want to promote commitment to action. That might sound like, "You mentioned that you want your child to start feeding themselves more often. What small step can we take together this week that is going to help make that better?" This is where motivational interviewing really comes in. We are trying to understand what will truly drive that parent and how we can support them in making positive changes.

Case Study: Tate

Pam: At this point, we would like to share a case study with you. This is Tate, and we will start by telling you a little bit about him.

Tate's Beginning

Dr. Rhonda Mattingly Williams: Tate is a three‑year‑old child with a diagnosis of global developmental delay. He lives at home with his parents, Lisa and Daniel.

He was born at 28 weeks’ gestation, weighing 2 pounds 8 ounces. So, right away, we know that Lisa and Daniel did not have the experience they were expecting; they had anticipated Tate being in utero for another twelve weeks or so, certainly more than twenty-eight. His premature birth was complicated by respiratory distress, as is so often the case. He required intubation and prolonged oxygen support in the NICU.

Tate also has a ventricular septal defect and continues to be monitored by cardiology. That means lots of medical appointments. He has GERD and constipation, which are being managed with medication and diet. He has been hospitalized multiple times because he is susceptible to respiratory viruses, and his recoveries are often lengthy.

His primary medical team includes a developmental pediatrician, a GI specialist, a PT, an OT, and an SLP. So Tate has a lot going on, and so do Lisa and Daniel.

Tate’s Progress to Current

Pam: When we consider Tate’s current progress and what he is capable of doing, his developmental profile appears as follows.

He began walking at 30 months. His gait is wide‑based, and he has decreased endurance. In terms of fine motor skills, he has difficulty with eye–hand coordination and grasp strength. He prefers using his left hand, but he switches frequently between hands.

Both his receptive and expressive language skills are delayed. He uses about 20 single words and follows most familiar one‑step directions. He participates in routines.

Cognitively, he primarily engages in cause‑and‑effect play. His attention span is short, and he struggles with transitions between activities.

Socially and emotionally, he is affectionate with familiar adults but tends to be slow to warm up to new people. He benefits from predictable routines, and the family is using some visual supports, which, as we often see, are helpful for many families and children.

More About Tate's Parents

Dr. Rhonda Mattingly Williams: A little more about Tate’s parents helps us understand the context in which they are living. We have already discussed fatigue and stress, and how they affect self-efficacy, and Lisa and Daniel are a good example of that.

Lisa is a restaurant manager. She works evenings and some weekends, which is not an easy schedule to manage. During the day, she is the one who takes care of Tate, brings him to medical and therapy appointments, and tries to limit his exposure to illness. Their family plan for managing Tate’s health means keeping him home as much as possible and restricting contact with groups of children and public settings. In many ways, that also keeps Lisa home. Her world becomes very small and very focused on Tate’s care.

Daniel is a banker. He leaves work in time to finish making dinner and to take over caring for Tate in the evenings. Lisa and Daniel do not get much time together, and both of them have relatively stressful jobs. Their entire existence revolves around ensuring Tate is cared for, and they cannot rely on many of the supports other families might use, such as daycare or a mother’s day out program, because they are concerned about potential illnesses.

The Lived Experience of Parents: Tate’s Medical/Development History

Pam: Tate’s medical and developmental history, as well as his parents’ lived experiences, significantly shape how they perceive themselves.

Lisa says things like, “What if I miss something? Those medical professionals, they’re all the experts,” implying that she is not. “I always need to be heightened and alert and make sure I’m protecting Tate.” Daniel says, “I feel out of my depth, or out of my element, on some of Tate’s medical care. Am I doing the right things to help him? I don’t want to do anything that’s going to hurt him.”

Dr. Rhonda Mattingly Williams: Through these comments, they are telling us how they experience their daily lives and how all of this affects their ability to feel like they can be influential change‑makers in Tate’s life.

How Can We Help?

Examining the Framework

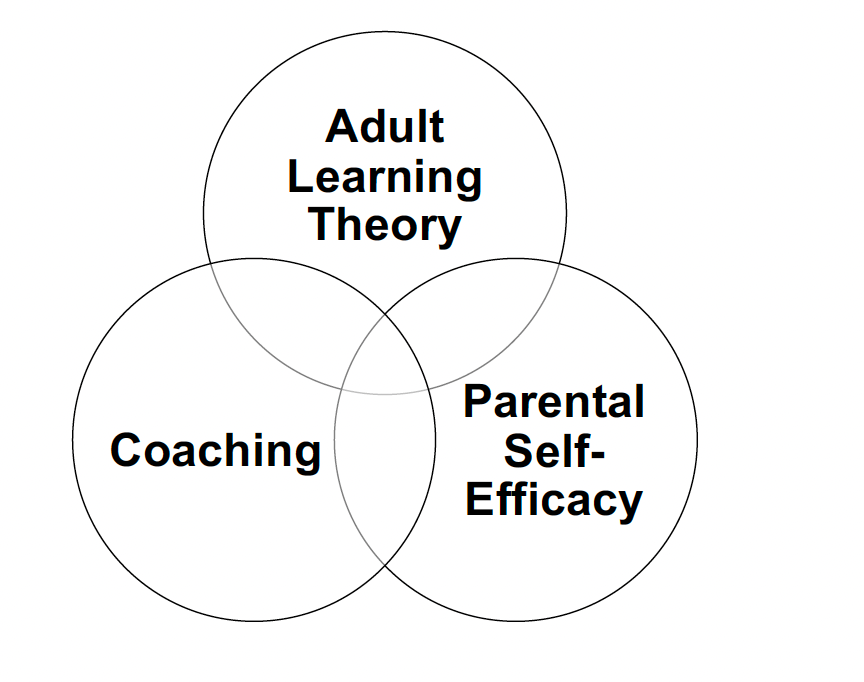

Dr. Rhonda Mattingly Williams: How can we help? Remember, we're considering these three different theories, seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Three different theories.

Pam: You have heard us discuss adult learning theory, coaching, and how these concepts intersect and share common ground with parental self-efficacy. We need to consider all three of these now together.

Adult Learning Theory

Dr. Rhonda Mattingly Williams: Let's start with adult learning theory. If you have seen our other presentations, this is a bit of a retake, but it is worth repeating. I think we all sometimes assume we have a handle on it, but then I realize that I need to hear it again.

Adult learning theory is a framework that explains how adults acquire knowledge differently from children. It emphasizes that adult learners have diverse needs, which relate to their prior experiences, their responsibilities—which are often huge—and their motivations, which sometimes need support simply because they are tired and stressed. It also acknowledges the influence of various nuances on the effectiveness of adult learning outcomes. That, in a nutshell, is what adult learning theory is.

Adult Learning Theory-Andragogy

Pam: When we think about andragogy, we often return to the work of Malcolm Shepherd Knowles. He lived from 1913 to 1997 and was an educator, usually referred to as the father of adult education. He studied at Harvard University and began teaching some of the first courses specifically focused on adult education at Boston University in 1959.

As practitioners, many of us did not become aware of his work until relatively recently, within the last several years.

Dr. Rhonda Mattingly Williams: Although it may have been more familiar in certain parts of the world or in specific disciplines, in therapy, early intervention, and pediatrics, this lens of adult learning is a relatively new way of thinking about our work.

Andragogy vs Pedagogy (Knowles, 1980)

Dr. Rhonda Mattingly Williams: Andragogy, as outlined in Knowles’ adult learning theory, is the art and science of helping adults learn. I want you to really pay attention to the small words here: it is about applicable knowledge.

It is not the same type of knowledge we transmit to children in a school setting. There is absolutely nothing wrong with communicating that kind of information to children in school—they need it, and we need it. But as adult learners, we need knowledge that is directly applicable to our lives.

So, andragogy is helping adults learn through applicable knowledge.

Pedagogy is different. It is the transmittal of knowledge and skills that have stood the test of time. It is content‑driven and fact‑laden—your American history, your mathematics, all of those subjects, which are essential. However, that is not what adults need when it comes to later life, especially when we are working with them around their children.

Underlying Principles of Andragogy

Pam: When we think of adults, we think of self-directed learners. They bring very valuable life experiences that support new learning. They are most engaged when the content is relevant, hands‑on, and connected to real‑world problems, because adults want to understand how the learning will help them achieve their personal goals.

They are most ready to learn when they recognize a need for new knowledge or new skills. Intrinsic motivation and practical application are the key drivers of effective adult learning. We have to pay attention to this when we are providing intervention—whether we are coaching in the home or in the clinic. We have to allow parents to be, at least in part, the drivers.

Dr. Rhonda Mattingly Williams: As we have said in our previous presentations, they are the experts on their own children and need to be treated as such. That alone will automatically influence how they perceive themselves. It will not fix everything, but it is undoubtedly a crucial first step.

Adult Learning Theory Principles (Childress, 2021)

Dr. Rhonda Mattingly Williams: As we have said, caregivers learn best when what is being learned is immediately relevant. Just like in our previous examples, when we are talking with a parent, we might say, "You mentioned you want to work on your child getting ready for daycare. We want to try these things out now, this week, because you do not want another week of fighting to get to daycare."

Caregivers also learn best when new knowledge is built on their prior knowledge. Parents have past experiences with their other children, and they have past experiences with the child we are currently working with in therapy. They might say, "Gosh, I have tried that," or "Another therapist tried that, and it did not work for my child." We need to show that we recognize their knowledge and experience. We also recognize that they are the experts on their own child, and we acknowledge that each child is an individual, as are each parent.

Caregivers need to understand what they are learning, why it is essential, and how to use it with their child or children. For example, they need to know that reducing screen time will help develop social and communication skills. I do not want to tell them, "Your child really needs to stop watching so much television," or "They need to stop being on the computer as much." I need to share with them why. I do not have to provide a comprehensive literature review, but I can sometimes simply state, "The literature has shown us since 1960..." or something similar. It will depend on the parent whether they want to hear that part or not.

Pam: We also have additional information about how caregivers learn. They learn best through active participation and practice. The 70-20-10 model, as shared by Charles Jennings, lends scientific weight to the effectiveness of hands-on learning. The idea is that 70% of learning comes from doing—from hands-on experience—20% from social interactions, and only 10% from formal training.

Caregivers learn and remember best when what they are learning is practiced in context and in real time. Thus, we need to allocate time in our sessions to allow the parent or caregiver to demonstrate the area of concern. If bath time is difficult, it probably starts with turning on the water, then trying to help the child disrobe, followed by getting into the tub, and finally staying in the tub. We need to know exactly where the hiccups are.

Caregivers also benefit from opportunities to sit back and reflect, and to receive feedback on their learning and performance. Therefore, we need to engage in real-world problems that help parents or caregivers develop the skills to analyze what went well, what could have been improved, and what they might do differently to find the right solution for them as individuals.

This brings us to the distinction between coaching and training. I actually asked this in class last week because I wanted to make sure my own students recognized the difference.

Coaching Vs. Training

Dr. Rhonda Mattingly Williams: Coaching versus training can be a bit nuanced.

Coaching involves supporting family members in making informed decisions and choices that are in their best interest. We absolutely share some of our expertise, as we cannot separate ourselves from what we know. However, in a coaching model, we really emphasize that the parent is the expert. The parent is the one who is always there. We are there for thirty minutes or an hour a week, or perhaps we see them in an office. The overarching objective is to enhance their involvement and to support the well‑being of both the child and the family.

Training is more about us showing parents techniques and strategies. We can still do that within a coaching model, but the difference is that with coaching, we are asking, “How do you feel about this?” “Do you think this will work with your child?” We involve them in the entire process, rather than taking the stance of, “I am the teacher; you are going to do this.”

Aims of Coaching in Intervention

Pam: The aims of coaching intervention include enhancing the family’s capacity so they can participate as active and equal partners in the intervention process. We also want to support the family so that they can make informed decisions. Through coaching, we work to enhance the caregiver’s self‑efficacy and their ability to improve their child’s participation in daily routines by empowering them.

Attributes Needed to Coach (Ziegler & Hadders-Algra, 2020)

Dr. Rhonda Mattingly Williams: What attributes are necessary for effective coaching? We have covered this before, but it bears repeating.

Attributes needed to coach are not always the same things we were explicitly taught when we earned our degrees. Our attitude needs to start with acceptance and promotion of the family unit and its autonomy. We need to acknowledge the family’s knowledge and competencies, and we need to make that acknowledgment overt. Our attitude should be visible in our behavior. We focus on meaningful goals that are based on the family's lead. We also have to be open to changing our own behaviors and attitudes—and that can be more difficult than almost anything else on this list.

In terms of knowledge, we need a solid grounding in family‑centered practice, a clear understanding of what coaching is and how to distinguish it from other approaches, familiarity with coaching strategies, and an understanding of andragogy. Some of you are getting that knowledge today; others may be refreshing what you already know or simply listening and thinking, “Yes, I agree with that.”

Then there are the skills. We need to know how to apply family‑centered practice, how to recognize the needs of the family, and how to communicate with them most effectively. We need the ability to share relevant information in a way that is not purely directive—“I am telling you what to do”—but more, “I am sharing this with you, and you are sharing back with me about your child, because you are the expert.” We must be able to ask open‑ended and reflective questions, and that is hard; it is much easier to ask yes‑or‑no questions. We need to provide opportunities for caregivers to practice and to deliver reflective feedback, even when it means repeating ourselves many times.

For example, in one of our previous talks, I described working with a parent on holding their child semi-upright for bottle-feeding. The parent kept dropping their shoulder, and the baby kept sliding down. After about ten repetitions, we looked around the room and asked, “How about if we move over here? Do you like sitting on this couch with the big arm and the large pillow?” That kind of problem‑solving can be challenging for us as providers, but it is precisely the kind of adjustment that supports the family.

Finally, we have to reflect on our own behavior and attitudes continually. We need to be honest with ourselves: How can I change what I am doing or how I am thinking to create a better outcome for this family and this child?

Pam: I also want to add that when I first became aware of this coaching process and started using it, it took more energy. I often felt more exhausted after my sessions because I was intentionally spending time centering myself beforehand, coming into the visit calm and focused, really trying to notice everything, and shifting away from being “live entertainment” for the parent and child. I was honing in on where I thought the family was and what they needed. As I grew into these strategies, I felt real growing pains—and that fatigue was part of the learning curve.

Coaching Strategies (Rush, Shelden, & Dunn, 2011)

Pam: Coaching strategies from Rush, Shelden, and Hanft include several key components.

First is joint planning. What does the caregiver want to work on next time, or even in today's session? What did you agree on in the last session? What activity or routine will be addressed? And writing it down.

Next is observation. We make time to observe the child and caregiver interacting, even on the first visit. Then we revisit the joint plan and ask the caregiver specifically, "What would you like help with today?"

Then comes action. We provide a review of the early intervention—or whatever service we are providing—and how it helps the caregiver enhance their own learning and develop skills within their child. We ask, "What routines can we work on during our time together?" Families might say, "Diaper changing is complex," or "Snack time is hard." "I really want to read books to my child, I know that is important, but this one just will not sit," or "Getting in and out of the car is a struggle." I have been brought to tears in a parking lot by one of my own children trying to get them into a car seat. I would have loved to have someone help me with that.

Reflection is the next step. We provide input on what was done without imposing our views. Using open‑ended questions helps grow a reflective conversation with the caregiver. Caregivers need options and the ability to make choices and decisions.

Finally, there is feedback. We share information about what the caregiver did, what they did not do, and how the child responded. Being specific here is essential. Providing that information allows the caregiver to learn from the experience you just practiced together.

Dr. Rhonda Mattingly Williams: I would like to add that when we say "providing a review of early intervention," this is not just an EI talk. These strategies extend to any pediatric therapy, and, in fact, you could apply them beyond that, because caregivers of adults also need self-efficacy.

The other thing I want to mention is that when Pam said she was brought to tears, it reminds me that people sometimes make the mistake of assuming that because someone is an OT, a speech pathologist, or a physical therapist, they should be able to "therapize" their own child. It does not work that way. As a parent, that is your role. You are the parent, and you do not see things the same way. You may have a bit more insight, but you are still the parent first.

I taught a class many years ago, I think in New York State, about children with autism and how practitioners talk to parents. After the class, a therapist came up to me and said, "I am an OT. I have worked with children with autism for decades. My child was diagnosed with autism, and everything they said to me sounded like Charlie Brown's teacher. But they assumed I was processing it all because I am an OT." That day, she was a parent, and she is always a parent when it comes to her child. That story has always stayed with me.

Strategies to Encourage Self-Efficacy

Dr. Rhonda Mattingly Williams: Now, let’s look at some specific strategies to encourage self‑efficacy.

One of the big ones is goal setting. We want to help parents set small goals. Significant goals are wonderful as long‑term aims, but they can quickly feel overwhelming. What we really need are short, manageable goals that parents can actually experience and celebrate—little successes over and over again.

These proximal goals act like stepping stones. A parent can say, “Oh, we tried this, and it worked. Then we tried that, and it worked too.” The literature suggests that these kinds of experiences not only enhance self-efficacy but also build resilience. Because we all know sometimes even a small step doesn’t work out—life happens, something gets in the way—and if there isn’t some resilience there, it can feel like everything falls apart.

But when parents have a pattern of meeting small goals, each success builds a sense of “I can do this,” and it also creates the “bounce‑back” they need when something doesn’t go as planned.

We also want to support self‑monitoring. This allows parents—or really anyone who is building self‑efficacy—to track their progress in tangible ways. For example, if the focus is dressing, a parent might track how many times their child can complete part or all of the dressing routine using the strategies they and the coach developed. They can note, “We tried this strategy, and here’s what happened.”

Each time they see progress, it boosts their self-efficacy. And it has another benefit: on the harder days, they can look back and say, “You know what, you’re right—we have made tremendous gains. Today feels like a bad day.”

Problem‑solving is another key strategy. As parents use strategies and work consistently toward their goals, we partner with them to work through what is and isn’t working. We might say, “It looks like sub‑goal number four didn’t really work out. Let’s problem‑solve together and see what we think might work better.” The emphasis is on we, not “I’ll fix that for you.” That collaborative stance helps parents feel supported throughout the process.

Then comes implementing solutions—actually trying out the ideas you’ve problem‑solved together, and noticing where things are working and where they are not. It’s similar to problem‑solving, but this is the action phase.

If we execute these stages effectively—by setting small goals, supporting self-monitoring, engaging in collaborative problem-solving, and implementing solutions with the family—we have a strong opportunity to encourage and strengthen positive parental self-efficacy truly.

Next, we'll examine three different approaches side by side.

Adult Learning Principles, Coaching Strategies, and Self-Efficacy Alignment

Pam: Now, I want to pull together the three threads we’ve been discussing: adult learning principles, coaching strategies, and self-efficacy, and walk you through that slide in words.

First, the adult learning principle: caregivers learn best when what is being learned is immediately relevant. When you look across the slide, you see that, in the coaching column, these line up with joint planning. In the self-efficacy column, it connects to goal setting: small, realistic, behavior-focused goals that make the learning directly applicable. We are trying to build success for both the child and the family.

Next, caregivers learn best when new knowledge is built upon prior knowledge and past experiences, as seen in coaching strategies that manifest as observation and joint planning. In the self-efficacy piece, that’s self-monitoring. Tracking progress builds on the family’s existing experiences and reinforces learning. Rhonda and I were discussing all the various ways we’ve used to help families track and self-monitor, including something as simple as a sticky note, a calendar, or a sheet posted in each room. There are many ready-made tools available, but the point is to give the family a way to monitor and keep track of their own data.

Caregivers also need to understand what they are learning, why it’s important, and how to use it with their children. On the coaching side, that’s again joint planning and feedback. On the self-efficacy side, that’s where problem-solving comes in: identifying barriers, naming obstacles, brainstorming solutions, and strengths with the family. We are helping them understand the hows and whys, and then what might actually be practical options to use as strategies.

The following adult learning principle is that caregivers learn best through active participation and practice. In coaching language, that is action. In the self-efficacy column, implementing a solution involves trying a strategy, practicing it, and strengthening skills. As they build success with those strategies, their self-efficacy grows.

We also know that caregivers learn and remember best when what they are learning is practiced in context and in real-time during the session. In the coaching strategies, that is, action and observation. In the self-efficacy column, which includes self-monitoring and extension, individuals observe and track in real-time. That in-the-moment tracking improves memory and confidence for future performance.

Finally, caregivers benefit from opportunities to reflect and receive feedback on their learning and performance. In the adult learning principles, that’s the reflection piece. In coaching, that is reflection and feedback. On the self-efficacy side, that is, problem-solving and implementing solutions—the feedback loop. We are reflecting on the barriers, thinking through possible solutions, and adjusting. That process reinforces their confidence and helps them handle similar situations with greater ease the next time they come up.

Dr. Rhonda Mattingly Williams: All of these layers support each other. These strategies are drawn from the literature, and you can see how well they align to move us toward the outcomes we genuinely want to achieve for families, not just for the child.

Revisiting Tate and Putting It All Together

Dr. Rhonda Mattingly Williams: Finally, let's revisit Tate and put it all together.

“Some” Current Challenges for Tate & His Family

Pam: Some of the current challenges for Tate and his family include ongoing medical monitoring and occasional hospital visits. Feeding is difficult and stressful because of his GERD and constipation, so mealtimes are not easy.

There are also challenges just keeping up with the schedule—being in the right place at the right time for all of his therapy visits. His reflux and respiratory concerns disrupt sleep, and, like many children, he simply does not always sleep well. Additionally, there is limited whole-family time due to Lisa and Daniel’s work schedules; one is coming, the other is going, and there is little overlap for them to spend together.

Everyone feels that there is progress across domains, but there are also setbacks and inconsistencies. One of the first things the family identified as especially challenging was managing parental stress and self‑care while still maintaining a family routine.

Dr. Rhonda Mattingly Williams: It is just so much. It is a lot for any family to carry. We are going to revisit Tate and walk through what was “on the table” for this family, and how we can start to put all of these ideas together—adult learning, coaching, and self‑efficacy—with some concrete examples.

Improving Coaching & Self-Efficacy

Dr. Rhonda Mattingly Williams: Family stress is something Tate’s parents frequently discuss, and sleep and meals are a significant part of that.

I want to preface this section by stating that, in our past two presentations, we have focused more on child outcomes. In this case, we are not going to spend as much time on Tate’s developmental outcomes. Instead, we aim to demonstrate how self-efficacy aligns with this process and what we can do to support it, so that these stress points—especially those related to sleep and meals—become areas where parents feel more equipped and resourced.

Therefore, when we consider improving coaching and self-efficacy regarding Tate’s sleep and meal issues, we return to adult learning theory. Lisa and Daniel need to know that what they are learning is relevant and valuable. They are exhausted. That is why we lean on the coaching strategy of joint planning; we want every session to really count. On the self‑efficacy side, we are trying to shift those feelings they have shared—“I’m not the expert,” “I’m overwhelmed,” “I don’t want to hurt him”—by helping them experience mastery.

We achieve this by setting small, realistic, behavior-focused goals that are directly applicable. For example, let’s take sleep. With Tate, we might start by asking, “What does good sleep look like to you?” and build from there. Together, we can create a bedtime routine that fits their reality. When Pam and I first talked about this, she reminded me that in some military literature, the first torture technique is sleep deprivation. So if Tate isn’t sleeping, it certainly doesn’t mean Lisa and Daniel are in the next room sleeping peacefully. They’re not. Everyone is affected.

Under this umbrella, we set small goals around sleep and meal times, so Lisa and Daniel can experience success repeatedly. Every small win builds self‑efficacy and resilience—both of which they’ll need long‑term.

Pam: Caregivers learn best when new knowledge is built on prior knowledge and experience. In coaching terms, that’s observation and joint planning. In self‑efficacy terms, it’s self‑monitoring—tracking progress, building on what they already know, and reinforcing learning.

For sleep and meals, that might start with a simple question: “How much sleep is actually happening?” We might use a sleep journal. Are we getting a 30‑minute nap at 3 p.m.? Five hours of solid sleep at night? Or are we waking every 30 minutes? What does a “good night” look like—for Tate, but also for Lisa and Daniel?

When I work with children who don’t sleep well, the parents almost always don’t sleep well either. I also remind families that, for most people, we can only change a sleep routine by about 15–20 minutes at a time. We are not going to suddenly go from 20 minutes of sleep to four uninterrupted hours of sleep. Setting that expectation helps everyone.

As Lisa and Daniel monitor Tate’s sleep, they’re also monitoring their own ability to stick with the plan. We want to help them build success slowly, but steadily, each time we see them.

Dr. Rhonda Mattingly Williams: The same applies to meals. Tate has GERD and constipation—both of which can make feeding incredibly difficult. Lisa and Daniel are pushing through a lot. We will ask them to self‑track and self‑monitor, while we observe and jointly plan the next steps. These are baby steps and small goals. We cannot neatly separate sleep, meals, coaching, and self-efficacy; they braid together. But we can highlight different pieces.

A significant part of this is reassuring parents that we are not judging them. We know this is hard. We can say, “Here’s what we’d like you to track this week—maybe how many times Tate gets out of bed, or how many minutes it takes to settle after each wake‑up.” Then we plan together for how to respond.

We also know caregivers need to understand what they are learning, why it matters, and how to use it. That is where the coaching phases of joint planning and feedback come in. On the self-efficacy side, this involves problem-solving, which includes identifying barriers, naming obstacles, and brainstorming together. That process can be incredibly enlightening for both therapist and parent.

For example, consider meals and the stress the family feels in trying to get Tate to eat more foods with fewer interruptions. We might decide, as one small goal, that Tate will help with meal prep by putting certain foods into a bowl—even foods he doesn’t yet eat. If we notice that this is causing distress, we go back to joint planning: “Let’s see where we can revamp this. What might feel more manageable?” We problem‑solve together and then give feedback on what we try next.

Pam: This reminds me of another family who struggled with the “food in the bowl, bowl on the table” step. It was too much. So we backed up and had the child go to the grocery store with Mom to pick out the food and put it in the cart. He was still touching it, but without the immediate pressure of eating it. That adjustment was still forward movement and felt more doable.

When we say caregivers learn best through active participation and practice, that’s the action phase in coaching. For self‑efficacy, that is, implementing solutions—trying strategies in real life and strengthening skills as they go. Parents rehearse and repeat the strategy with support from the coach when needed. Every hands‑on experience builds and improves confidence.

Our aim, utilizing adult learning principles and coaching strategies, is to enhance parental self-efficacy by creating opportunities for success that are repeated. If that means breaking goals into even smaller steps, we do that—and we genuinely celebrate those steps.

For sleep, for example, we might introduce visual supports that the parent and child create together, such as a simple sequence showing “bath, book, small snack, into bed with my lovey.” When Tate gets out of bed, the response is consistent: “Back to bed,” walk him back, show the picture, turn the nightlight on, tuck him in. The visual becomes part of the routine.

Dr. Rhonda Mattingly Williams: An important point about this kind of action is that each repetition—each time Lisa and Daniel use the visuals and follow the routine—provides both the parent and the coach with more information. Maybe Mom notices, “He really doesn’t respond when we try strategy A, but strategy B seems to help him settle.” That tells us where to lean in and where to adjust.

We also know that caregivers learn and remember best when what they’re learning is practiced in context and in real-time. That’s action and observation: parents doing things, us observing, and them observing themselves. On the self-efficacy side, that involves self-monitoring and extending their skills—observing and tracking in real-time to build memory and confidence.

So, again, we’re tracking sleep strategies: What did we try? What seemed to help? Pam and I discussed finding tracking methods that suit the family. Mom may start out wanting to write everything in a detailed journal—but we don’t want to add to her stress. She might later decide, “You know what, it’s easier for me to keep some sticky notes in Tate’s bedside drawer and jot things down right then.” That’s still self‑monitoring; it’s just more doable.

Pam: Finally, caregivers benefit from opportunities to reflect and receive feedback on their learning and performance. That’s reflection and feedback in coaching, problem‑solving, plus implementing solutions in self‑efficacy—a feedback loop.

We reflect on barriers and on what worked and what did not. Then we readjust. All of this helps build confidence. Tate builds confidence as routines around sleep and meals become more predictable and less chaotic. The adults build confidence as they realize, “We really are going to go to bed,” or “We really are going to sit at the table and have food presented,” even if they don’t eat everything.

We cannot force a child to sleep or eat, but we can walk through the routines calmly and consistently.

Dr. Rhonda Mattingly Williams: One of the most prominent themes I hear from adults is that they do not want fake or superficial feedback. So as coaches, it’s vital that we jot down specific observations so we can give honest, concrete feedback:

“This is exactly what I saw working when you did it that way. Do you agree?”

“You were really consistent with the bedtime visual this week, even though you were tired. That kind of consistency makes a difference.”

Parents also reflect to us. They might say, “I’m doing the visuals every night. I feel more confident with the routine, but I’m not sure this piece is working as well as another strategy.” That opens up the conversation and keeps it collaborative.

Ultimately, it is all about communication and helping the parent understand that you are the expert on their child. We are here to support you. We move forward together, both to help your child reach the outcomes you’re hoping for and to help you feel empowered and capable in your role as a parent.

Questions and Answers

Let's now get to some questions. (Both presenters answered these.)

Can this approach be used to coach teachers in early childhood settings?

Yes, it absolutely can. When you think about teachers, especially in early childhood settings, you have to recognize the pressures they are under. They are constantly being told that they are not addressing enough of the curriculum, do not have enough hands, and are trying to meet the needs of many children with minimal time and resources. Their days are often full of directions, expectations, and corrections, and they may hear very few comments about what is actually going well. When you walk into a classroom with a coaching mindset, one of the most powerful things you can do is start by noticing and naming the positive things you see: the ways they connect with children, the routines they’ve established, the moments where things are going smoothly. From there, you can shift into realistic and respectful conversations about areas that could run more smoothly, and then work together to problem-solve. You might try out different options side by side, adjust routines, or tweak the environment together. In that way, the same coaching approach that supports parents can be applied very naturally to teachers. It becomes a process of joining them in their reality, acknowledging their strengths, and partnering with them to make changes that feel possible in the context of their very full days.

Can this approach also be used with adult caregivers, such as those caring for someone with a brain injury or stroke?

Yes, this approach translates very well into adult settings and with adult caregivers. Many caregivers of adults find themselves in a role they never anticipated. They may have believed their daughter or son was entirely an adult, independent, and out in the world. Then, suddenly, that person experiences a traumatic brain injury, a stroke, or another serious diagnosis that changes everything. In an instant, the caregiver is no longer simply a parent, spouse, or sibling; they are now also a primary support person for someone with significant new needs. The coaching approach can be just as meaningful here as it is in early childhood. The key idea is to make sure caregivers feel confident and supported in what they are being asked to do. By drawing on insights from adult learning theory and coaching, you can structure your interactions so that the caregiver is not overwhelmed but instead feels guided and affirmed. You help them connect strategies to their daily routines at home, walk through what is realistic, and check in regularly about how things are going. Another critical piece is creating opportunities for peer connection. When several caregivers or parents can meet in the same place at the same time, even something as simple as going to the same park, a lot of support and learning can happen naturally and organically. People notice each other, they share experiences, and sometimes they even recognize a professional “voice” in another parent, just as when someone at a Playground notices the way a parent is facilitating interaction and asks if they do that with kids professionally. These peer moments can reinforce confidence and reduce the isolation caregivers often feel.

It isn't easy to get parents to return data tracking that feels accurate enough to celebrate progress and build new goals. What are some examples of data collection processes that families have actually found success with?

Families have found success with data collection systems that are simple, flexible, and tailored to their everyday lives. One approach is to provide families with very concrete materials at the outset, such as folders, colored paper, sticky notes, or even masking tape, and then invite them to choose the system that best suits them. The message is that there is no one right way to do it. You might say, “This is what has worked in my house,” or “This is what other families have liked,” while also emphasizing that it is completely fine for them to adapt the system or come up with something different. The essential goal is simply that some record gets made. Many families now naturally gravitate toward using their phones, which makes sense given how central phones have become in daily life. At the same time, it can sometimes be harder to visualize and organize what is happening when everything is stored in a digital note or scattered among apps. With paper or sticky notes, you can physically lay them out, line them up in chronological order, and literally see patterns or gaps over the course of a week. That visual organization can make it easier to discuss what is going on together. It is also helpful to be honest with families about the limitations of sparse data. If, over the past seven days, you have only three entries recorded, that makes it very difficult to draw solid conclusions. Instead of treating that as a failure, you can use it as a starting point for conversation by saying something like, “If this is all we’ve got written down, tell me what you think is happening beyond these few moments.” That way, you are inviting narrative information to fill in the blanks rather than just dismissing the data as incomplete.

Do you have specific suggestions for how to organize data tracking in the home, especially for things like language or feeding?

One efficient strategy is to match the data tracking tools to the routines and rooms where the target skills actually occur. For early language goals, for example, a significant amount of learning occurs during everyday routines, such as getting dressed, brushing teeth, eating meals, playing, and getting ready for bed. In that case, it can be beneficial to have a small chart or piece of paper in each key room where those routines take place, such as a chart in the bathroom, another in the kitchen, and another in the main play area. That way, when a parent is in the middle of a routine, and something notable happens—maybe the child uses a new word, gesture, or combination—they can quickly jot down a note right there, rather than trying to remember later. Similarly, if the focus is on feeding, then the tracking materials belong in the spaces where feeding actually happens: near the high chair, on the refrigerator, by the dining table, or on a pantry door. This keeps data collection grounded in real time and in the natural context, rather than as an abstract task that has to be done at the end of an already exhausting day. To make sharing that information easier, you can also explicitly invite families not to worry about physically bringing the papers to appointments. Instead, you can encourage them to take photos of their charts or notes on their phone and show you the pictures at the clinic or hospital. Many people are already in the habit of taking large numbers of photos as memory aids in their daily lives, so this approach utilizes a familiar behavior rather than introducing a new system. They do not have to remember the folder or the notebook; they open their camera roll, and the information is there. Even with all of these strategies, it is realistic to expect that the data will not always be perfect or complete. The goal is to keep moving in the direction of better, more usable information over time, to use whatever is captured as a basis for conversation, and to recognize and celebrate progress in both the child’s development and the family’s comfort with tracking it.

Summary

Thanks, everyone, for joining us. I hope this course and the broader series were helpful to you.

References

See additional handout.

Citation

Smithy, P., & Williams, R. M. (2025). Using adult learning theory to enhance coaching practice and parental self-efficacy. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5846. Retrieved from https://OccupationalTherapy.com