Dr. Iwama: Hello everybody and thank everybody for participating in this this morning. I am excited to spend the next couple of hours talking about the newest substantial model of practice in occupational therapy.

Introduction to the Kawa Model

The Kawa Model is the first model in occupational therapy that was made outside of the Western English-speaking world and was created originally in a different language, Japanese. It is also a model that was raised from clinical practice, which is unusual. Since its creation in 1999, this model has spread around the world. It is now taught in more than 500 occupational therapy programs and used in practice across all six continents. One of the last frontiers is here in the United States, but already there are several programs across the country that have adopted the model as the basis for their curriculum. There continues to be development on the model. I want to introduce the Kawa Model to you today with an emphasis on case studies and how the model is actually used.

Consequences of Conditions and Circumstances on Daily Life Experience

When I present the Kawa Model to different occupational therapists across different cultural contexts, I start by focusing on our mandate. Simply stated, occupational therapy enables people from all streams of life to engage and participate in activities and processes of daily living that matter. This simply stated promise can be very difficult and challenging to deliver because every one of our clients is a unique human being. While the kinds of tasks and activities that we engage in may be similar to many people in our community, the meaning that those activities hold will differ from one person to another.

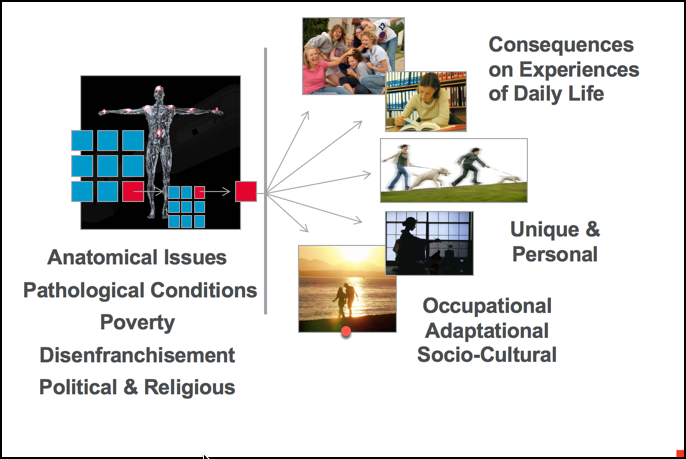

Figure 1. Moving beyond pathology.

What I am trying to demonstrate here in this figure is that OT in the industrialized world is focused on pathology that is medically defined. Much our concerns in OT have to do with helping people deal with problems that are occurring inside the body. If you encounter a health issue of some sort, the usual pattern is that you go to a hospital or medical center, there are questions and tests, and a diagnosis is made. Once a diagnosis is given, then treatment, including occupational therapy, could be prescribed and started. We are part of a system of healthcare in which the problems are defined as being embodied and essentially physical in nature. The reason why I say physical is because even issues around mental health are often explained at a brain level looking at synapses, biochemistry, and hormones. Our medical centers are where a subjective report is provided, followed by so-called objective measures to verify the condition to give it a name (diagnosis), and then treatment can start. I contend that the potential and the power of occupational therapy is still yet to be realized. We are doing a very good job and have a defined role in healthcare today, especially in those applications that we see on the left-hand side of the picture in Figure 1. However, our real potential to make a difference in people's lives is located out of the body on the right side, looking at the environment and the context of daily living in which we live. We need to continue to help people deal with the embodied pathology, but we also need to help people deal with the consequences of those embodied pathologies on everyday living. This is again what makes delivery of that simple promise so difficult and challenging as we all live a very different and unique life.

It is important to understand the nature of the consequences of these embodied pathologies. Let's imagine you fell down some steps and hurt your back, and the injury and pain was so severe that you had to be taken by ambulance to the hospital. During the usual triage process, you identified lower back pain and tingling sensations down the back of your legs. Subjective reports would then be followed by some objective tests where maybe a scan or an X-ray would be completed to ensure that the joints and the spine were intact. You are diagnosed with a soft tissue injury at the L4-L5 level of your lumbar spine, prescribed pain medication and muscle relaxants, and sent home. Your family helps you when you get home, and you sleep in a makeshift bed in the living room. The next morning, you find that you are so sore that you cannot get out of bed or go to work. This affects all of your daily routines. You cannot participate when friends invite you out. This impaired pattern of daily living begins to persist even longer, and you are now waking up at 11 o'clock in the morning, just in time to watch your favorite daytime television programs. Your kids do not approach you anymore with their homework or to play because they know what the answer is going to be. You are also not helping out with the household chores. It continues to the point where you lose your job, have a loss of income, and all kinds of other problems like quarreling with your spouse and your family members. The stress levels are beginning to rise. Your friends do not even bother calling you anymore and everything just seems to be on a downhill roll. Depression may then set in. You may then be living a life that is very much reflective of being a a chronic patient, rather than an able parent, spouse, worker, student, etc. In the worst-case scenario, there might be family breakups and and even suicide.

Conventional Theory, Instruments & Approaches

Health professionals in the Western world are so focused on what is happening inside the body that often we never get to the areas where we can really make a difference. As occupational therapists, we have been trained to be conversant about problems and challenges, not just those that are occurring within the human body, but those also occurring in the context of the social and the physical environment. We have developed our knowledge and theory in occupational therapy as social scientists. Modern time is exemplified by the tendency to develop frameworks, theories, and models that are universal in nature. For example, there is an unspoken agreement that this particular model is good for everyone, everywhere. Because if it works and makes sense to me, it must make sense for everyone else. If we stay within a modernist way of thinking, then we will develop our assessments, approaches, and instruments in a likewise manner. We take one particular standard, and then we then apply that to all of our clients and their situations regardless of the diversity that they are facing. When you think about this particular perspective that I have just explained, there is also a framework of power at play in which the health professional holds greater power over the client and takes authority over understanding what is happening with the client and in their life. Maybe even to the point where we feel that we can explain reality to our clients even better than the client can explain it themselves. In my use of the Kawa Model with clients in different parts of the world, the traditional approach of occupational therapy imposes a particular set of ideals in terms of what should be happening with the client, but often what gets lost or does not get heard is the client's story and experience of their everyday life realities told in their own words and in their own ways. I believe that one of the greatest challenges that is the facing occupational therapy today is one of relevance. We need to continue to evolve our occupational therapy in a manner that is responses to the day-to-day realities of our diverse clients.

Meta-Narratives & Universal Models

This tendency of using a one-size-fits-all type of approach is going to be greatly challenged as we move into the postmodern age. That is the movement from the modernist way of thinking to a postmodern way of thinking. In this day of social media and advanced digital technology, the realization that different people have different perspectives and views are expedited through social media. In order to move occupational therapy in a direction that is more responsive to the unique lives and experiences of our clients. We need to develop frameworks, methods, and approaches that are useful and will support an occupational therapy that is responsive to the uniqueness of our clients. Years ago, a group of us occupational therapists in Japan developed a new framework that would give us a better chance of understanding the client's day-to-day realities.

Kawa is the Japanese word for river and as you will see as this presentation goes along, the metaphor of a river to depict a person's life journey and life experience is used. That is the reason why this particular model is called the Kawa, the river model. We want to be able to describe how the river metaphor can be utilized as a powerful tool or framework to guide occupational therapy interventions and to explain at least three examples of how the Kawa Model can be used in occupational therapy practice settings or contexts. I think that that will be simple to do once you understand the model, begin trying it out, and applying it into your own life. Then from there, it will be very easy to imagine how the model can be then used in different occupational therapy contexts.

My River

I want to take a brief moment to just tell you a little bit about myself. I want to do this so you know the Kawa model's origins. Theories and models do not descend from heaven, and they are not perfect. They are constructed by human beings like you and me. We take our views of the world or our understanding of a particular object or phenomenon in our world, and we take the time to systematically explain it in a simpler way to other people. In this particular case, I was able to take a set of ideas that explained the process of occupational therapy and put it down in a systematic way. Lo and behold, we produced something called the Kawa Model.

I want to follow this by saying some our greatest theorists in our profession today are clinicians and practitioners. On a day to day basis, you hold the essence of occupational therapy in your hands. You work with real people and are helping them to engage in activities and processes that matter to them. Along the way, you gain experience and wisdom regarding these processes, and if you were to actually write some of these ideas down and build a systematic way to be able to explain those processes, you would then have a model. The next step would be to publish this model and conduct research to determine its characteristics. If the Kawa Model seems very simple to understand and very simple to you, it is because it was created by practitioners and clinicians like many of you.

I was born and raised Okinawa, in the southernmost part of Japan. There is a large American military installation there, as it is situated in the Pacific Ocean in a strategic location. It is in close proximity to the Japanese mainland, the Korean Peninsula, the Philippines, as well as to Taiwan and China. If there is any kind of trouble politically that happens in that area of the world, the American military is poised and set to be able to respond. I benefited from the American presence on the island of Okinawa in that my parents were able to send me and my two older brothers to an American school. This is why I can speak English the way that I can with you today.

I was in my teens when my family then moved to Vancouver, Canada. This is where I finished most of my tertiary education, including occupational therapy. My first bachelor's degree was in the area of exercise physiology and then that I was accepted into a program of study in physical therapy. I then saw the light and quit physical therapy to join the occupational therapy department. My second bachelor's degree was in the field of occupational therapy. I later went on to finish a master's degree in rehabilitation sciences at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada. Afer teaching occupational therapy in my native Japan, I studied for my PhD in international comparative sociology, and then later on, I would get into another PhD program in the Netherlands at the University of Leiden, where I studied medical anthropology. I fulfilled all my requirements there except for the dissertation, so it is actually ABD, not a complete PhD over there. I have worked at five different universities in four different countries, and most recently, I am in Augusta, Georgia at Augusta University.

I think that it is important to note that I have taught occupational therapy in a number of countries; Australia, United Kingdom, Canada, Japan, and now in the United States. It is through the rich experiences that I have had in all of these different occupational therapy settings, that gave me a body of experience that compelled me to begin to ask a lot of questions. I became interested in our core ideas, and its interface in theory construction and culture. The nexus between those concerns and the Kawa Model is a product of that process.

Western Cosmology

We all do not look at the world and understand reality in the same way. One of the things that I have encountered in trying to understand theory in occupational therapy is that I contend that we all start from fundamentally different places with regard to how we view reality, how we review our clients, and how we view the environments in which our clients abide in. We call these views of reality in the social science literature as cosmological myths or cosmologies. These are our imaginations of the universe, ourselves, the world, and the meaning of life. Bellah's Beyond Belief: Essays on Religion in a Post Traditional World (1991), defined these Western cosmologies.

- God/truth

- Self

- Society

- Nature/environment

If we were to take a look at how those of us living in the Western world view reality, there would be a common pattern. The majority of the world views the universe and themselves within it as everything being all connected together in one inseparable whole. Since the Age of Enlightenment, during the 1700s in Europe, we have developed a very different kind of cosmology. In the Judeo Christian and Islamic traditions, the view is a singular God, or a singular omnipotent truth. Then God's creation with regard to the individual self, society, and then nature. The grand narrative means that nature has been given to us for our use and our pleasure, but we are supposed to also be good stewards of nature as well. The above categories fit in a particular hierarchy. They are hierarchically arranged. In this example, God is at the very top, then self, and even though God loves everybody equally, there is the rest of society, and then nature. Usually, the hierarchy and the status is given according to how these objects in our world resemble us, resemble me, or the things that are important to me. Often that is the way that these categories are arranged. This is the basic way of thinking and philosophical basis that informs our scientific method today.