Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Assessment And Treatment Of Stroke In Young Adults, presented by Kwasi Nkansa, OTD, OTR/L.

*Please also use the handout with this text course to supplement the material.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to identify stroke types, clinical presentation, and symptoms through assessment.

- After this course, participants will be able to recognize modifiable risk factors for ischemic stroke.

- After this course, participants will be able to list potential secondary prevention approaches.

Introduction/Agenda

- Background: Definitions & Stroke Classification

- The Problem & Evidence Base

- Occupational Therapy’s Role

- Modifiable Risk Factors

- Guiding Theories

- OT Implications

- Client Management of Risk Factors & Prevention

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgments

Learning outcomes for this course include identifying different types of stroke and recognizing their clinical presentations through appropriate assessment. Participants will also be able to recognize modifiable risk factors for ischemic stroke and list strategies for secondary stroke prevention.

The agenda begins with background information, including definitions and stroke classifications. We’ll then explore the scope of the problem and the supporting evidence base. From there, we’ll examine the role of occupational therapy, particularly in addressing modifiable risk factors. Guiding theoretical frameworks will be discussed to help contextualize our approach, followed by OT-specific implications for practice. We’ll also address how clients can manage risk factors and use prevention strategies.

By the end of the course, participants should be able to define what a stroke is, recognize the symptoms, and understand how stroke can significantly impact the lives of young adults. The goal is to promote a clearer understanding of the role occupational therapy practitioners play in stroke rehabilitation and to identify modifiable risk factors critical to preventing secondary ischemic strokes. We will conclude with a summary and acknowledgments.

What is a Stroke?

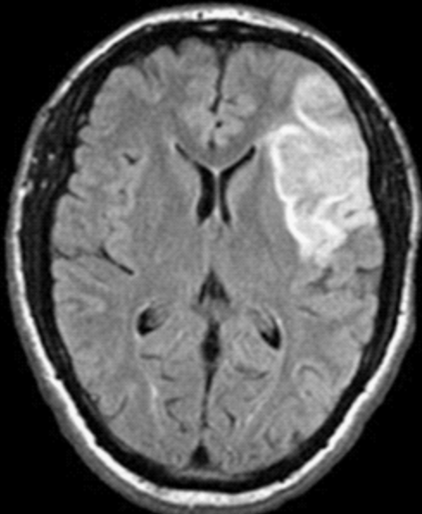

A stroke is damage to the brain caused by a disruption in blood supply. This interruption can lead to the death of brain cells and loss of function in the affected area. The MRI image (Figure 1) shows damage localized to a specific brain lobe. That region is directly associated with the patient's difficulty performing activities of daily living (ADLs), which may include dressing, bathing, grooming, or managing household responsibilities. The affected lobe helps determine compromised functional areas, guiding the clinical focus and occupational therapy interventions.

Figure 1. A stroke or disruption to the blood supply in the brain.

Stroke Classifications

In terms of stroke classifications, the two main types are most commonly seen. A hemorrhagic stroke occurs when a blood vessel ruptures, disrupting the flow of blood to the brain. This leads to bleeding within or around the brain tissue. In contrast, an ischemic stroke results from a clot or blockage that obstructs blood flow to a part of the brain. This is the most common type of stroke.

A subtype of ischemic stroke is the transient ischemic attack (TIA), often called a “mini-stroke.” While the symptoms may not appear severe initially, a TIA serves as a serious warning sign—it places the individual at significantly higher risk for experiencing a second, potentially more debilitating stroke. In short, an ischemic stroke is caused by a blockage, and a brain bleed causes a hemorrhagic stroke.

Continuing with stroke classifications, we also see cryptogenic strokes, where the exact cause remains unknown despite thorough evaluation. These cannot be identified as stemming from a clot or a rupture.

Brain stem strokes present a particularly complex picture. Because the brain stem controls many vital functions and relays messages between the brain and the rest of the body, a stroke in this region can impact both sides. In severe cases, it may lead to a “locked-in” state. When this occurs, the individual cannot speak or move anything below the neck. However, cognition often remains fully intact. The patient may still have control over eye movements or other facial features, and tools like the Wong-Baker Faces Pain Rating Scale or eye-tracking technology may be used to assess responses and facilitate communication during therapy.

Stroke By Another Name

Several other names are used to describe strokes, depending on the context or medical setting.

CVA, which stands for cerebrovascular accident, is a widely used medical term for stroke. Cerebral infarction is another term often used when referring to an area of brain tissue that has died due to a lack of blood flow. Vascular insult and cerebral accident are also used, though somewhat less frequently.

The term brain attack is sometimes used in public education to emphasize the urgency of recognizing and treating a stroke, much like a heart attack. It helps convey the need for immediate medical attention.

A broader category that encompasses stroke is cerebral accident, which can refer to a range of events affecting cerebral circulation, including both ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes.

Lastly, as mentioned earlier, a transient ischemic attack (TIA), commonly known as a mini stroke, is characterized by temporary stroke-like symptoms. Although the symptoms resolve quickly, it is still considered a medical emergency and a strong warning sign for future strokes.

The Problem

Here’s the problem we’re focusing on: there is a rising number of young adults under the age of 40 experiencing strokes in the United States. This trend is alarming, not only because of the increasing incidence, but also because of the long-term consequences. Young stroke survivors are at significantly higher risk of being rehospitalized due to subsequent strokes, which tend to present with more severe symptoms and can, in some cases, result in death.

The most common type of stroke in this age group is ischemic. However, these strokes are often missed or misdiagnosed. A major contributing factor is the persistent misconception that strokes only happen to older adults. This bias can lead to delays in recognition, diagnosis, and timely intervention, putting younger patients at even greater risk.

Common Signs

There are several common signs that all clinicians should be vigilant about when assessing for stroke. These include limb dysfunction, such as weakness or numbness on one side of the body, and speech difficulties, including slurred speech or trouble finding words. Difficulty swallowing, or dysphagia, is another red flag, often identified during the early stages of evaluation.

Poor balance and coordination issues may also present, especially when the cerebellum or brainstem is involved. Impaired motor function can range from subtle changes in fine motor skills to significant mobility limitations. Cognitive impairments may appear as confusion, memory issues, or difficulty with attention and problem-solving.

Visual disturbances—such as blurred vision, double vision, or partial loss of vision—should also be taken seriously. In some cases, clinicians may notice facial changes like asymmetry or drooping, which can indicate cranial nerve involvement. When observed collectively or in isolation, these signs should prompt immediate further assessment to rule out or confirm a stroke diagnosis.

Ischemic Stroke

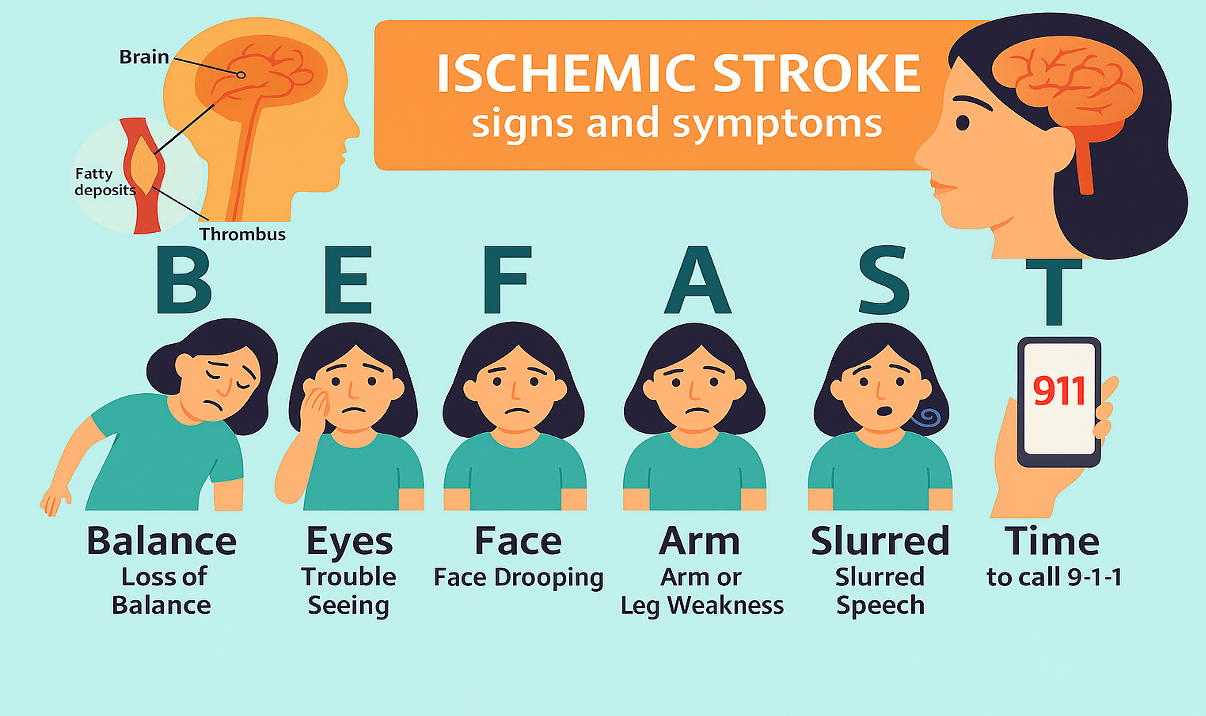

Here's a schematic of the signs and symptoms of ischemic stroke (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Schematic of ischemic stroke.

When blood flow is disrupted and a clot forms inside the brain, it can have a profound effect on a person’s ability to function. I consistently emphasize this when discussing stroke symptoms.

One key thing I want people to remember is the acronym BE FAST. It’s a simple yet powerful way to recognize the early warning signs of a stroke.

Start with balance—has there been a sudden loss of coordination or an onset of dizziness? Then check the eyes—are there any visual disturbances, such as blurred or double vision, or sudden loss of sight? Next, look at the face—is there any asymmetry or drooping? Sometimes people describe it as a tingling or numbness, almost like a parasitic sensation on one side.

Then move to the limbs—do you notice weakness or numbness in an arm or leg, especially on one side of the body? Finally, listen to the speech—is it slurred, confused, or difficult to understand?

If any of these signs are present: balance problems, eye changes, facial drooping, arm or leg weakness, or slurred speech. Don’t wait. Go straight to the hospital to ensure it’s not an ischemic stroke—every minute counts.

Misdiagnosis & Mimics in Young Adults

Hyperglycemia, electrolyte imbalances, and metabolic encephalopathies are all common stroke mimics. These conditions can produce neurological symptoms that closely resemble those of a true stroke, often leading to confusion during initial evaluation. Seizures—particularly when followed by a postictal state—can also present in a way that mimics stroke, with temporary weakness or speech changes that resemble a vascular event.

Demyelinating diseases such as multiple sclerosis and Guillain-Barré syndrome further complicate the picture. Their presentations may include sudden-onset motor or sensory deficits, much like those seen in ischemic stroke.

Migraine with aura is another frequent and often overlooked mimic. Patients may experience visual disturbances, followed by significant changes in balance or gait. In some cases, they suddenly find themselves unable to carry out routine daily activities, which can be mistaken for stroke onset.

Cervical radiculopathy, or a pinched nerve, can also create stroke-like symptoms such as numbness, limb weakness, or impaired movement. These overlapping signs highlight the importance of thorough differential diagnosis, especially in younger patients, where the index of suspicion for stroke may be lower.

How Stroke is Confirmed in This Group

Stroke is typically confirmed through imaging techniques such as MRIs (magnetic resonance imaging) and CT scans (computed tomography). These tools provide detailed views of the brain, allowing clinicians to differentiate between ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes. They are essential for guiding immediate treatment decisions and determining the extent and location of brain damage.

Physical examinations are also crucial in the diagnostic process. This is where our roles as occupational therapy practitioners (OTPs), physical therapists, speech-language pathologists, and neurologists become central. Each discipline brings a unique perspective to assessing functional deficits—whether in cognition, movement, speech, or daily activities—often accompanying stroke.

Blood work helps identify underlying risk factors, such as high cholesterol levels, clotting disorders, and infections, that may contribute to stroke risk. However, no single blood test can confirm a stroke diagnosis. Instead, blood work adds valuable information to the overall clinical picture, supporting the diagnosis but not establishing it independently.

Problems With Current Treatment

There are several persistent problems with current treatment approaches. One of the most significant is the lingering misconception that stroke is primarily a disease of older adults. As a result, much of what we do in clinical settings is still guided by protocols developed for individuals over 60. While research on younger stroke populations is beginning to emerge, it’s still limited, and the dominant model remains heavily anchored in the traditional medical framework. This model emphasizes physical recovery and focuses on standardized metrics that often don't reflect the full scope of a young adult’s rehabilitation needs.

In acute care, it’s common to hear statements like, “The patient can ambulate, so they must be fine.” There’s a strong emphasis on physical milestones—particularly for older patients—and far less attention given to cognitive, emotional, or psychosocial recovery. The approach tends to revolve around visible impairments such as hemiparesis or limb weakness, with goals often tied to concrete benchmarks like the ability to walk 100 feet. If patients meet those targets, they may be cleared for discharge—even if they’re still struggling with essential ADLs like dressing, meal preparation, or returning to work, school, or parenting roles.

This kind of reactive model neglects the broader picture of recovery, especially for younger adults who are often navigating major life transitions. We’re not applying developmental frameworks such as Erikson’s psychosocial stages, which can offer valuable insight. For individuals in this age group, recovery should also involve rebuilding a sense of identity, reclaiming social roles, mitigating isolation, and strengthening confidence in their ability to manage everyday life. This stage is pivotal, and when we ignore those dimensions, we risk falling short of supporting a full and meaningful recovery.

Data Trends for Young Stroke Clients

Some of the data trends we’re seeing for young stroke clients in clinical practice are deeply concerning. Hospitalizations for ischemic stroke among individuals under 45 have increased by 44% over the past 25 years. These are not isolated or rare occurrences—they represent a growing public health issue with long-term medical, psychological, and societal implications.

The psychosocial impact is particularly striking. Around 15% of couples separate within just three months of one partner being diagnosed with an ischemic stroke. Many young survivors also experience significant challenges when returning to work or school. This disruption in occupational identity can lead to a loss of purpose, self-confidence, and financial stability, often resulting in heightened emotional and psychological distress.

From a physical health perspective, the prognosis for young survivors is also troubling. They face an increased risk of post-stroke hypertension, early-onset cardiovascular disease, and even death within the first five years following the initial event. Over 50% of sleep disorders in this population are linked to nocturnal hypertension, including silent blood pressure surges that often go undetected but significantly elevate the risk for another stroke.

Perhaps most alarming is that the risk for a second stroke is five times higher in young adults compared to individuals aged 65 and older. Looking ahead, estimates suggest that by 2050, half of all ischemic stroke cases will occur in young adults. These numbers highlight the urgent need for age-appropriate, preventative, and comprehensive care models—approaches that move beyond traditional geriatric stroke frameworks and are tailored to younger adults' unique challenges and life stages.

How Symptoms May Impact I/ADLs

Possible deficits following a stroke can include poor balance, impaired coordination, and difficulty with motor planning, all of which affect functional ambulation, particularly during essential out-of-bed tasks like toileting or bathing. Decreased cognitive function may be present as well, impacting memory, processing speed, sequencing, and self-awareness.

Speech deficits often interfere with the ability to express thoughts clearly, communicate a history, or articulate goals for therapy. In some cases, expressive or receptive language impairments make it difficult for individuals to engage in collaborative treatment planning or advocate for their needs.

Sensory impairments may lead to diminished sensation or trouble with texture discrimination, making tasks such as holding utensils, grooming tools, or other everyday objects more challenging. As mentioned earlier, hemiparetic deficits—where one side of the body is impaired—can result in functional limitations like difficulty threading an arm through a sleeve or pulling on pant legs, further complicating dressing and hygiene routines.

Visual field deficits or visual cuts may also occur, which can increase the risk of falls and impair navigation in the environment. Eating and swallowing difficulties are common, and they can directly affect nutritional intake and raise the risk of aspiration.

All of these impairments ultimately impact an individual’s ability to engage socially. Reduced mobility, communication difficulties, and cognitive changes can create significant barriers to social participation, further isolating individuals during an already vulnerable recovery period.

Model of the Problem

Going back to Erikson’s model of psychosocial development, this stage—spanning roughly ages 18 to 40—focuses on intimacy versus isolation. During this time, individuals form deeper connections, build careers, establish identities, and solidify social roles. When a young adult experiences a stroke, there’s often limited interaction with peer groups and a significant disruption to self-identity, both of which are crucial during this life stage. The impact goes far beyond physical recovery.

Adults between 21 and 40 who experience their first ischemic stroke face an increased risk for poor cardiovascular health. Socialization often declines, peer engagement suffers, and cognitive and emotional fatigue can become compounded by persistent sleep deprivation—an issue that’s frequently overlooked. This sets off a trajectory where individuals require more services and support. Without proper intervention, the risk of a second, more severe stroke increases, along with the potential for early mortality.

However, this pathway isn’t inevitable. We can interrupt these last two stages—greater dependency and elevated risk of severe outcomes—by focusing on modifiable risk factors. When we proactively address hypertension with physical inactivity, nutrition, sleep hygiene, and psychosocial stressors, we not only support better recovery outcomes but also reduce the long-term burden on individuals and the healthcare system.

Social Factors: Problems After Returning Home

Social factors play a significant role in the recovery process, particularly for young adults returning home after a stroke. Many face challenges far beyond the physical, including social isolation, difficulty reintegrating into their peer groups, and disruptions in relationships with partners or spouses. These challenges often contribute to a decline in emotional well-being.

Anxiety and Depression

Depression is commonly reported not just in the immediate aftermath of a stroke but often persists for up to a year afterward. Many individuals struggle with their sense of self, experiencing a profound loss of intrinsic motivation and facing significant difficulty re-engaging in meaningful activities. This emotional burden isn’t just challenging—it actively hinders rehabilitation and diminishes overall quality of life.

Anxiety is another major factor that is frequently underrecognized in post-stroke care. From what I've observed and read, the rates of generalized anxiety disorder in stroke survivors are significantly elevated, with symptoms that can persist for as long as ten years after the initial ischemic event. These long-term emotional effects are not only distressing in their own right but are also linked to worsened cardiovascular health over time. Unaddressed emotional distress contributes to a harmful cycle involving poor sleep, diminished physical activity, and elevated blood pressure—factors that together increase the likelihood of a second stroke.

Addressing the psychological and emotional needs of younger stroke survivors is particularly important. When we incorporate mental health support into the overall care plan—especially interventions targeting depression and anxiety—we foster improved functional outcomes, facilitate the reconstruction of identity, and enhance long-term cardiovascular health and stroke prevention.

Research indicates that rates of anxiety and depression are more than three times higher in stroke survivors compared to the general population.

Issues With Partner or Spouse

In my clinical experience, these mental health challenges often extend beyond the individual to affect intimate relationships. I recall one study that reported an increased caregiving burden on partners or spouses, noting that they may spend up to four additional hours each day assisting with routine daily tasks—tasks that the individual could manage independently before their stroke. This dynamic not only places strain on relationships but also underscores the necessity of holistic, family-centered stroke rehabilitation approaches. Nearly half of the partners report an increased level of dissatisfaction with the stroke survivor. In some cases, married couples have had to divorce within a year after the stroke due to strains on the relationship.

Physical Dysfunction

Physical dysfunction after a stroke often leads to significant changes in how activities of daily living are performed. These adaptations, while necessary, can serve as constant reminders of loss and can profoundly affect a person's sense of autonomy. Changes in the nervous system can also influence partner intimacy and sexual health, areas that are rarely addressed in a clinical setting but have profound implications for quality of life and relationship satisfaction.

In my experience, engagement with more intense physical activity or exercise is also associated with a noticeable decrease. This can be due to physical limitations, a decline in functional independence, or the persistent fear of having another stroke. Even routine symptoms like fatigue or mild weakness during activity can trigger anxiety, creating a pattern of avoidance that further impacts overall recovery and participation. Addressing these concerns requires a nuanced approach that goes beyond physical rehabilitation to include open conversations about intimacy, mental health, and long-term self-efficacy.

Self-efficacy & Doubt

Self-efficacy and doubt can significantly impact a person's motivation to accomplish meaningful daily tasks. I've seen how reduced confidence interferes with the ability or desire to return to pre-stroke performance levels. This becomes especially evident in young adults hoping to return to school or work, which often serve as central components of their identity.

The way peers perceive them can also be a barrier. I've had patients express feelings of self-consciousness about using walkers or other assistive devices when returning home after an ischemic stroke. That discomfort often extends beyond physical appearance—it touches on deeper concerns about being seen as capable, independent, or "normal" again.

Changes or redirection of life goals are common. Educational pursuits, career trajectories, and parenting roles may need reevaluation. Sleep, crucial for brain function and overall vascular health, is often disrupted. More than 50% of stroke survivors in this population report some form of sleep disorder or disruption. The consequences are far-reaching, affecting memory consolidation, nervous system regulation, muscle recovery, protein synthesis, and respiratory function. Addressing sleep as part of recovery is essential, especially for younger individuals whose long-term goals and identity are still taking shape.

Sleep

A recent study by the NIH, not included on this slide, suggests that sleep disruption may affect up to 70% of stroke survivors. Despite its critical role in recovery and long-term health, sleep is often overlooked in clinical conversations. Many young adults report experiencing periods of insomnia or fragmented sleep following a stroke. They might find themselves relying on daily naps to cope with fatigue, but still struggle to achieve a full night’s rest. This disrupted sleep pattern not only impairs cognitive and physical recovery but also places individuals at an increased risk for another stroke. Addressing sleep health needs to be a central part of post-stroke care, particularly for younger survivors whose sleep disturbances may go unrecognized or be mistaken for temporary stress-related changes.

Social Isolation

Social isolation is a significant and often underappreciated consequence of stroke, particularly among younger survivors. When your social role changes—whether as a student, coworker, parent, or friend—it can lead to a deep disconnect. Many individuals report feelings of loneliness, not necessarily because they are alone, but because their peers are unable to relate to what they’re going through. This aligns with Erikson’s psychosocial model, where challenges in forming identity and intimacy become especially salient during young adulthood.

I’ve worked with patients who experience a noticeable decline in academic performance or express real fear about whether they’ll be able to achieve their career goals. The uncertainty surrounding future accomplishments can become an emotional trigger, further compounding anxiety and depression. This emotional strain sometimes reduces the willingness to engage in social interactions, even with long-standing friends. The result is a cycle of withdrawal and isolation, making it harder to rebuild confidence, re-establish roles, and access the emotional support needed for recovery. Addressing these psychosocial components is essential in guiding younger stroke survivors toward reintegration and long-term well-being.

Modifiable & External Risk Factors

A modifiable risk factor is a behavior or characteristic that someone can change to lower their risk for disease or health conditions like an ischemic stroke. An external risk factor, an external problem factor, includes characteristics outside of a person’s direct control that can negatively impact health and health outcomes.

External Problem Factors

Some examples include poor air quality and gender disparities. Women in this group are at a higher risk for ischemic stroke and are more likely to seek help when experiencing symptoms, whereas men are more likely to dismiss symptoms, hoping they will resolve on their own.

Socioeconomic status also plays a significant role. Affordability of necessary health services can be a barrier to timely care and follow-up. Other external factors include limited local access to healthy foods—commonly seen in food deserts—and difficulty accessing in-person healthcare services after experiencing an ischemic stroke.

Modifiable Risk Factors (MFRs)

Looking more closely at modifiable risk factors, these include adjustable behaviors that are often precursors to disease. Examples include levels of physical activity, social engagement, smoking, alcohol or drug use, sleep habits, diet, and medication or treatment compliance. These are areas where intentional changes can significantly reduce the risk of experiencing an ischemic stroke or improve recovery outcomes after one has occurred. In particular, poor compliance with medical recommendations can undermine even the most well-designed treatment plans, making consistent follow-through a critical component of prevention and rehabilitation.

Addressing Problems Through MRFs

Addressing modifiable risk factors has been proven effective in the management of chronic conditions like diabetes and hypertension. Approximately 80% of ischemic strokes in young adults are caused by modifiable risk factors and lifestyle choices. This underscores the importance of targeting these areas for prevention and rehabilitation.

When addressing the problem through modifiable risk factors, it's essential to consider psychosocial elements as part of the patient’s objectives and goals. Empowering clients to take an active role in managing secondary disease prevention can support the formation of meaningful long-term goals and reduce the likelihood of another ischemic stroke.

Short-term goals can be reasonably straightforward. For example, increasing socialization, improving sleep habits, and enhancing cardiovascular health are tangible and impactful areas to focus on. This might involve monitoring sleep patterns, paying attention to how many hours of rest are achieved each night, and identifying whether sleep feels restorative. Social engagement can be tracked by noting how much time is spent interacting with peers or friends during the day, and journaling may help increase awareness and accountability.

Cardiovascular health goals could include assessing how much physical activity occurs each week and setting realistic targets for gradual improvement. Whether through walking, structured exercise, or movement throughout daily routines, the focus is on building consistent habits that support vascular health and overall recovery.

Key MRFs & OT Disease Management

Key modifiable risk factors in occupational therapy disease management must be clearly emphasized. More than 50% of stroke patients report difficulty sleeping, which significantly increases the risk for a subsequent stroke. We have to drive that point home—sleep is not a secondary concern but central to recovery and prevention.

Management of cardiovascular health is another critical area. Conditions like hypertension and diabetes, when combined with lifestyle factors such as poor compliance with medical recommendations and limited physical activity, are common precursors to ischemic stroke and its recurrence in young adults. Occupational therapy practitioners play a vital role in helping clients integrate sustainable health routines into daily life.

Social participation and psychosocial factors also require focused attention. Reduced socialization and underlying mental health issues post-stroke have been directly linked to stroke recurrence. Nearly one-third of survivors experience post-stroke depression and anxiety, which places additional strain on both heart and brain health. This, in turn, affects one’s ability to engage in daily activities, pursue educational goals, and adhere to secondary prevention strategies. These emotional and behavioral dimensions must be addressed holistically within the occupational therapy plan of care.

Education & Secondary Prevention

Physical deficits following a first ischemic stroke may be mild, especially in young adults, allowing them to continue with basic daily activities despite lingering symptoms. For example, balance might be slightly off, but they can still walk down the street or get dressed independently—it may take a bit more time or effort. However, having experienced one ischemic stroke places them at increased risk for a more severe second stroke. That’s why adapting and modifying behaviors early is critical, before things progress.

Over time, as individuals resume their routines and reintegrate into the community, they may downplay or dismiss their symptoms. This often leads to reduced compliance with healthcare regimens and prescribed recommendations. Lingering deficits, even when seemingly minor, can contribute to a false sense of recovery and lead to neglect of preventative measures.

Young adults in this population are 25% more likely to have a second stroke within the first five years and 30% more likely within ten years. Many of those who experience a second ischemic stroke report not being adequately informed about their risk of recurrence. This is where we come in as occupational therapy practitioners—to provide education, support behavior change, and highlight often-overlooked risk factors. Our role includes reinforcing the importance of long-term prevention strategies, helping patients recognize warning signs, and ensuring they understand how to manage lifestyle and psychosocial contributors to stroke recurrence.

OT as the Bridge

Occupational therapy serves as the bridge in stroke recovery, connecting daily life's physical, cognitive, and emotional aspects. It's essential to emphasize the link between cognitive and physical function, especially when resuming meaningful activities. We play a key role in addressing the mental health challenges that often follow a stroke, ensuring that emotional well-being is not overlooked in the rehabilitation process.

A major part of our work involves looking at how patients reintegrate into their communities and reclaiming their social roles—roles vital to identity, purpose, and motivation. We also focus on the physical components of recovery by addressing specific issues related to limb function, sensory-motor control, strength, coordination, and balance. These elements are deeply rooted in the medical model referenced early on, but we bring in the functional lens that makes this care personal and relevant.

Restoring habits, routines, and leisure activities—areas highlighted in the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework—is just as important. These are not secondary concerns; they are essential to our patients’ recovery and quality of life. Using a holistic approach, we help facilitate sustainable lifestyle changes that support long-term health, independence, and well-being.

Stroke Scales to Track Outcomes

Common stroke scales used in the acute setting help track patient progress over time and guide care planning and discharge decisions. One of the most widely used is the NIH Stroke Scale, developed by the National Institutes of Health. This scale assesses various domains, including language, neglect, sensory loss, motor strength, ataxia, and level of consciousness. Scores range from 0 to 42, with lower scores indicating better neurological function and less severe stroke involvement.

Another commonly used tool is the Modified Rankin Scale (mRS), which focuses on functional independence and is heavily based on a patient's walking ability. Like the NIH scale, lower scores are more favorable. The mRS is often used to determine discharge readiness in acute care settings, particularly when patients can ambulate with a score of 0 to 2. However, in my role as an occupational therapist, I often find that patients discharged based on ambulation scores may still face significant challenges in performing activities of daily living (ADLs) or instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs). Social factors, such as the ability to return to meaningful roles or participate in the community, are also overlooked if ambulation appears strong.

The NIH Stroke Scale and the Modified Rankin Scale are used across disciplines, including physical therapy and speech-language pathology. While they provide essential information, we as OTPs must advocate for a broader, more holistic assessment that goes beyond walking and looks at the full range of skills and supports needed for a successful return to everyday life.

OTPF & Stroke in this Population

The Occupational Therapy Practice Framework (OTPF) provides a strong foundation for guiding intervention with stroke survivors, particularly in younger populations. In this context, we often use establish, restore, and remediate approaches to help clients regain function and re-engage in meaningful daily activities.

We focus on changing client variables by working to establish or restore skills that have been impaired due to the stroke. This might include addressing motor planning, cognitive processing, sensory integration, or emotional regulation—all essential for occupational performance.

We also implement a prevention approach by addressing the needs of clients who are either living with a disability or are at risk for occupational performance challenges. This includes educating clients on stroke recurrence prevention and supporting the development of healthy habits that promote long-term independence.

Throughout the intervention, we consider multiple aspects of client functioning. These include bodily functions like neuromuscular and skeletal components, and mental functions like motivation, sleep, and emotional resilience. Psychosocial health, sensory processing, and the body's structural integrity all influence occupational engagement. In addition, we evaluate performance skills, patterns, personal factors, and the client’s ability to interact socially. These underlying elements are integral to shaping goals and delivering client-centered care aligned with the OTPF.

Guiding Theories of Therapeutic Design

Some of the guiding theories I use in this research include the Health Belief Model and the Diffusion of Innovation theory.

The Health Belief Model focuses on interpersonal change and emphasizes reflecting on and challenging your health perceptions. It encourages individuals to recognize personal cues to action that can support effective goal setting. This process is critical in developing healthier behaviors that directly reduce the risk of a second ischemic stroke. Clients are more likely to adopt and maintain preventive behaviors by increasing self-awareness and understanding perceived risks and benefits.

The Diffusion of Innovation theory highlights how change occurs across communities and populations in a sequence. It encourages individuals to follow, learn, and adopt new concepts that expand upon traditional health models. In this context, it supports incorporating technology and innovative approaches to stroke prevention. For example, seeking out online peer groups or digital platforms can provide community, accountability, and shared learning during recovery. These virtual connections can offer emotional support, information exchange, and reinforcement of strategies that help prevent a more severe second stroke.

OT Practice Implications

Occupational therapy practice implications in this area are significant and should be explored through evidence-based research. Occupational therapy practitioners are uniquely positioned to lead collaborative efforts that support young stroke survivors in managing disease prevention and long-term health.

Group intervention is a realistic and effective approach within our scope of practice. It allows for peer connection, accountability, and shared experiences, which can help normalize challenges and promote motivation. Incorporating education and remote support—such as telehealth check-ins, online peer groups, and guided home programs—can expand access and continuity of care, especially for younger adults balancing return to school, work, or caregiving roles.

It’s also important to showcase the full breadth of occupational therapy. Beyond physical rehabilitation, we offer strengths in addressing psychosocial health and supporting social participation. This includes developing individualized mental health strategies, promoting healthy sleep routines, encouraging re-engagement in social roles, and improving strength, balance, and communication. These are recurring themes throughout this presentation, reflecting our profession's holistic, client-centered focus. We must continue to drive these points home—occupational therapy is critical for restoring function and empowering clients to build sustainable, meaningful lives after stroke.

Community Resources & Groups

Community resources and support groups play a vital role in recovery and prevention for young stroke survivors. One valuable option is the Stroke Support Association, which offers in-person group meetings for young stroke survivors and their family members. These meetings provide a space for shared experiences, emotional support, and peer connection.

Another excellent resource is the Stroke Network, an online platform offering education and support for survivors, caregivers, and clinicians. With over 10,000 members worldwide, the network holds weekly meetings and provides access to various discussions and resources. It creates a virtual community that helps reduce isolation and fosters consistent encouragement throughout the recovery process.

The Young Stroke Group through the American Stroke Association is another meaningful option. This group offers weekly virtual meetings for which patients can sign up at their convenience. Many survivors report feeling like no one truly understands what they’re going through, not even their spousal partners at home. These groups help bridge that gap by connecting individuals with others who share similar experiences and challenges.

Engaging with these community resources can support emotional healing, promote long-term recovery, and play an essential role in preventing the risk of a second ischemic stroke. They offer structure and social reinforcement, key elements in rebuilding confidence and motivation after a stroke.

Clients Managing Risk Factors

Clients managing their risk factors is a decisive step toward long-term stroke prevention and recovery. As occupational therapy practitioners, we can educate clients on practical strategies to help them track their progress and actively mitigate the risk of a second stroke. This might include monitoring vital signs related to cardiovascular health, such as blood pressure or heart rate, to stay informed and proactive.

Encouraging clients to journal their progress toward meaningful personal goals can foster motivation and self-awareness. Increased physical activity and regular exercise are essential for vascular health and emotional well-being. Supporting cessation of harmful habits—such as smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, or drug use—is also critical for reducing stroke risk.

Helping clients identify and reduce mentally stressful triggers can be equally impactful. Teaching techniques to manage stress and promoting regular, fulfilling social interaction can enhance emotional regulation and quality of life. Sleep should also be a central focus—improving the quality and duration of rest can strengthen cognitive function and reduce vascular strain.

Establishing a healthy work-life balance helps clients sustain progress without becoming overwhelmed. Finally, encouraging open communication with loved ones about how the client copes can strengthen support systems and reduce feelings of isolation. These elements support a self-directed, sustainable approach to stroke recovery and long-term health.

Conclusion

Remember that each patient is unique. It’s essential to recognize which activities hold personal meaning for each individual, as these are often key to restoring both psychosocial and physical health. Meaningful engagement fosters motivation, reinforces identity, and supports emotional resilience throughout recovery.

Identifying modifiable risk factors that can be addressed is a central part of our role. By targeting these areas—whether related to lifestyle, behavior, or environment—we can help facilitate healthier choices that reduce the likelihood of stroke recurrence.

Education is equally important. Take time to inform both patients and colleagues about the range of risk factors and psychosocial challenges that impact young stroke survivors. These discussions can raise awareness, build empathy, and ensure that the unique needs of this population are recognized and supported across all levels of care.

Questions and Answers

Can you talk briefly about your arts program and how you came about it for your capstone? Did you see a need in the community or have a particular case that led you there?

What I noticed in my clinical practice was that more and more young people were coming in with stroke-like symptoms. Occasionally, they were diagnosed with a stroke, often after a missed diagnosis or initial misclassification. By the time they were correctly identified, they were presenting with more severe symptoms, like hemiparetic weakness, nerve disturbances, sensory deficits, or the inability to maintain balance over time.

It became clear that these strokes were not isolated incidents. More young adults were experiencing ischemic strokes, and the aftermath was affecting their social participation, sense of identity, and ability to resume life roles. That’s when I started diving into the research, and I saw alarming trends, particularly here in the U.S.—a global increase in strokes among young people.

That led to the creation of my capstone arts program focused on return to socialization. It’s designed to address not only physical limitations, but also the social barriers young stroke survivors face.

When treating these clients, do you ever see them placed on brain injury units or other floors because clinicians are trying to figure out what’s going on? Do you find that these cases mimic other conditions?

Absolutely. Often, these cases are initially misinterpreted as something like migraine with aura. Patients report symptoms like visual disturbances, balance issues, or difficulty returning to work, especially in physically demanding jobs. When tests don't follow a standard stroke protocol used for older adults, these symptoms are overlooked. You might see these patients on various floors, but they start getting the appropriate attention only once the symptoms worsen, like with full hemiparesis. We're only now beginning to pay closer attention to those earlier, milder symptoms that are early warnings of a second, potentially more severe stroke.

Knowing that younger stroke survivors benefit from social interaction and that caregivers also need support, have you run any groups to address these needs?

I’ve run several small groups in acute care settings, particularly in a previous hospital. One of the challenges is that younger patients aren’t always forthcoming. If they can function—even if not at 100%—they’re often reluctant to seek additional help. But when we’ve been able to gather participants, the groups have emphasized the psychosocial aspect of recovery: sharing personal experiences, discussing modifiable risk factors, and recognizing the importance of sleep, emotional expression, and communication with family. These sessions help patients feel understood and less isolated, encouraging greater patience and empathy from caregivers.

Do you have any advice about maintaining continuity of care for stroke survivors across acute, SNF, home health, and community settings?

My most significant advice is to ensure each discipline's role, especially OT, is well understood. Often, if patients can ambulate 100 feet, demonstrate some strength, and participate in feeding with minimal support, they’re deemed ready for discharge. But that ignores deeper issues—cognitive, psychosocial, emotional—that OT specifically targets.

We need to look beyond basic physical performance and consider how patients resume their life roles. Tools like the NIH Stroke Scale and Modified Rankin Score help track function, but we must add scales that address cognition and psychosocial factors. That would give us a fuller picture of recovery over time.

In your research, did you identify any causes for increased strokes among young adults?

Several lifestyle-related factors came up: poor sleep habits, lack of physical activity, and decreased social interaction. Many young people are juggling school, jobs, or even multiple jobs, which cumulatively impact cardiovascular health. Sleep deprivation is a major issue that tends to be underestimated.

If we can encourage more attention to life balance—time for leisure, exercise, and rest—we can help prevent first-time ischemic strokes and reduce the risk for more severe secondary strokes. It’s about looking at health holistically.

Did you find any direct connection between stroke and COVID-19?

A: Not directly in my research, but I wouldn’t rule it out. Long COVID may play a role, primarily through respiratory limitations or persistent fatigue. The depression and isolation during the pandemic also likely contributed. Erikson’s psychosocial model highlights how crucial social interaction is in early adulthood. Being forced into isolation disrupts those developmental processes. So while I didn’t find a direct link, the indirect effects are worth exploring.

Have you seen a relationship between migraines with aura and stroke in young adults?

Yes, there’s some overlap. Visual disturbances and field cuts are common in stroke, but young people often report similar symptoms with migraines. They’ll describe blurry vision, double vision, or visual confusion that resolves, so they dismiss it. Clinicians sometimes do, too. But these could be early signs of an ischemic stroke. Education is critical—patients should never ignore these symptoms, and clinicians should explore them further, especially if they’re recurrent.

Was there any familial connection to stroke identified in your research?

Not in this specific study, but family history plays a role. As more research emerges, I’d expect to see family history as a contributing factor, especially when it comes to early-onset stroke risk.

Is recreational drug use contributing to the rise in strokes in younger people?

I believe so. While I don’t have the exact statistics, I’ve seen several younger patients with a history of drug use experience strokes. Anecdotally, their symptoms can sometimes be more severe. It’s something worth examining further in research.

Do you include energy drink consumption in stroke prevention education?

Yes. Energy drinks can significantly elevate heart rate and blood pressure, putting extra strain on the cardiovascular system. Especially in those with preexisting risk factors or a history of stroke, these drinks can be harmful. If someone feels they must use stimulants, they should space them out and use them sparingly. I recommend alternatives like physical activity and better sleep hygiene to boost energy naturally.

What about coffee? Should we be worried?

Moderate coffee consumption doesn’t pose the same risks as energy drinks. The caffeine content in coffee is usually lower, and the research linking it to stroke isn’t as strong. That said, if you’re experiencing jitteriness, anxiety, or an elevated heart rate, it’s a good idea to cut back. Listen to your body. If it feels off, it probably is.

Could digital tracking—smartwatches, mindfulness apps—help stroke prevention or recovery?

Digital tools can help monitor sleep, activity, and heart rate. In the arts program, we looked at how to use technology not just recreationally but therapeutically. Young adults are already engaged with digital devices, so why not use them to track progress and promote healthy habits? It’s empowering and practical.

Could the limited PTO in the U.S. compared to European countries contribute to stroke risk?

Yes. People hesitate to take time off due to job insecurity or workplace expectations. But just as we give patients rest breaks during therapy, we must give ourselves time to recover and recharge. Burnout and chronic stress are real risks that can lead to serious health issues, including stroke and cardiovascular disease. Mental health should be a top priority.

Are there specific treatment ideas that younger patients respond better to? And how do you collaborate with other professionals?

Collaboration is key. I always try to educate physicians and case managers about the full scope of OT—we’re not just addressing mobility. We focus on cognition, emotional health, and role recovery.

For example, I may share with PT that while patients can ambulate 100 feet, they struggle with transfers into the shower or onto the toilet. That collaboration ensures safety is addressed across the board. With speech therapy, we might discuss feeding—maybe the patient can lift a fork, but they can’t open food containers. That impacts nutritional intake and independence.

Younger patients also respond well to approaches that focus on identity and lifestyle. They don’t always like assistive devices, so we talk openly about those psychosocial barriers. Education, patient-led goals, and involving them in real-life tasks are strategies that tend to work well. And again, emphasizing sleep, socialization, and stress management is central to our approach with this group.

References

Please refer to the additional handout.

Citation

Nkansa, K. (2025). Assessment and treatment of stroke in young adults. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5819. Available at www.occupationaltherapy.com