Editor’s note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Occupational Therapy’s Role in Addressing the Needs of People Experiencing Homelessness, presented by Caitlin Synovec, OTD OTR/L, BCMH.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to identify areas of occupation impacted by experiencing homelessness.

- After this course, participants will be able to identify types of services and organizations routinely accessed by people experiencing homelessness (PEH).

- After this course, participants will be able to identify the role of occupational therapy in settings serving people experiencing homelessness.

Introduction

Welcome everyone to today's presentation. I have served in multiple roles as a clinician working in population health and doing consultations for different organizations. I have integrated these practices for people experiencing homelessness in clinical and service settings.

My background is mental health, and I started in inpatient psychiatric settings. My role has evolved from this to working in community settings with different populations like those experiencing homelessness. I help those individuals identify barriers preventing them from engaging in services and occupations in this role. This talk today will focus on advocacy and capacity building to reduce these barriers by integrating OT into all spaces where folks are experiencing homelessness access services.

Before we get into the role of OT, I want to provide some definitions.

Defining Homelessness

- U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development [HUD] (2012) defines “literally homeless” as:

- Individual or family who lacks a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence, meaning:

- (i) Has a primary nighttime residence that is a public or private place not meant for human habitation;

- (ii) Is living in a publicly or privately operated shelter designated to provide temporary living arrangements (including congregate shelters, transitional housing, and hotels and motels paid for by charitable organizations or by federal, state, and local government programs); or

- (iii) Is exiting an institution where they have resided for 90 days or less and who resided in an emergency shelter or place not meant for human habitation immediately before entering that institution.

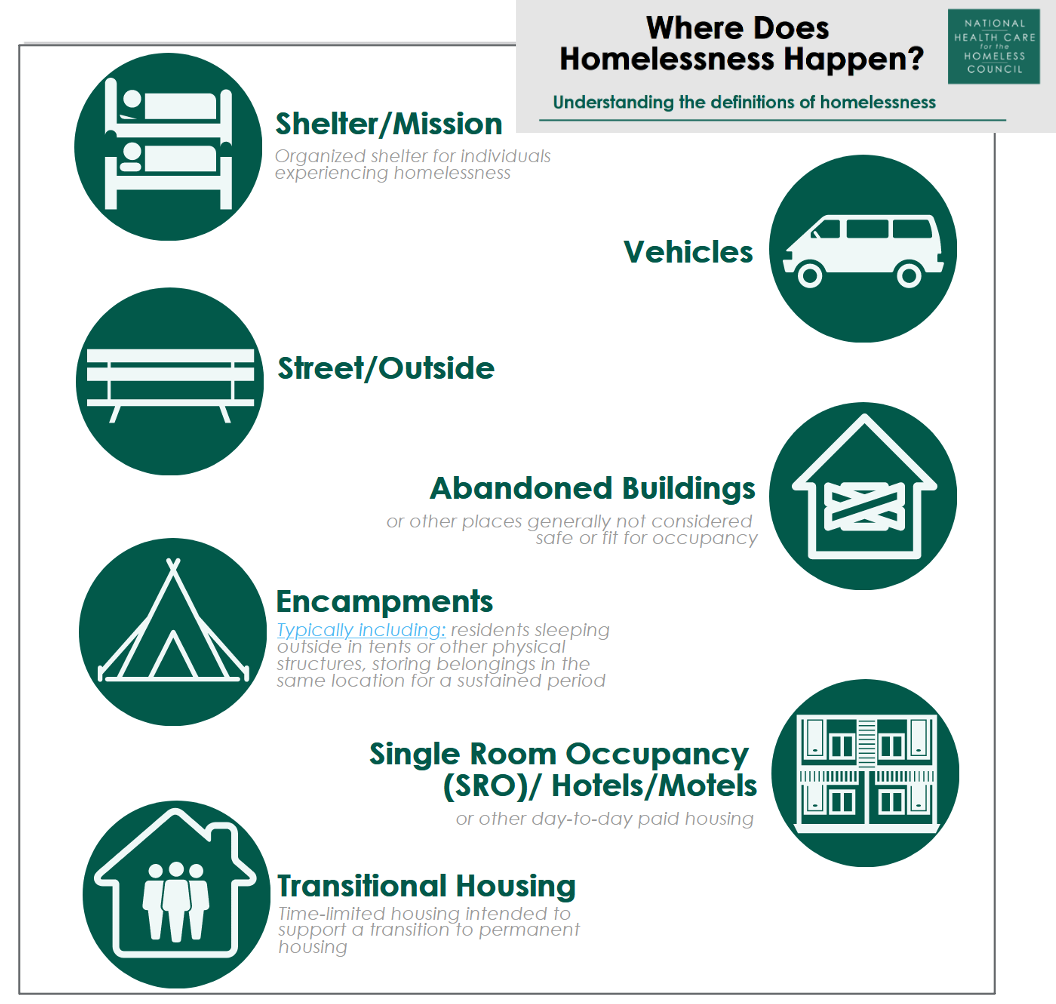

Many organizations and individuals rely on the definition provided by the Department of Housing and Urban Development, or HUD, which defines homeless as an individual or a family who lacks a fixed regular and adequate nighttime residence. I like this visualization developed by the National Health Care for the Homeless Council and our team (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Definitions of homelessness (https://nhchc.org/where-does-homelessness-happen/). Click here to enlarge the image.

When using the HUD definition of homelessness, these individuals might be staying at a shelter or mission setting, living in vehicles, outside or on the streets, living in abandoned buildings or spaces not meant for human habitation, or those living in encampments. Individuals experiencing homelessness have become a little more noticeable and prominent in many communities, primarily due to COVID. Individuals staying night to night in a hotel or motel may also be considered in this category. They do not have a fixed residence and can only stay in single-room occupancies when they have the money. There are also folks in transitional housing. I will describe this a little more later.

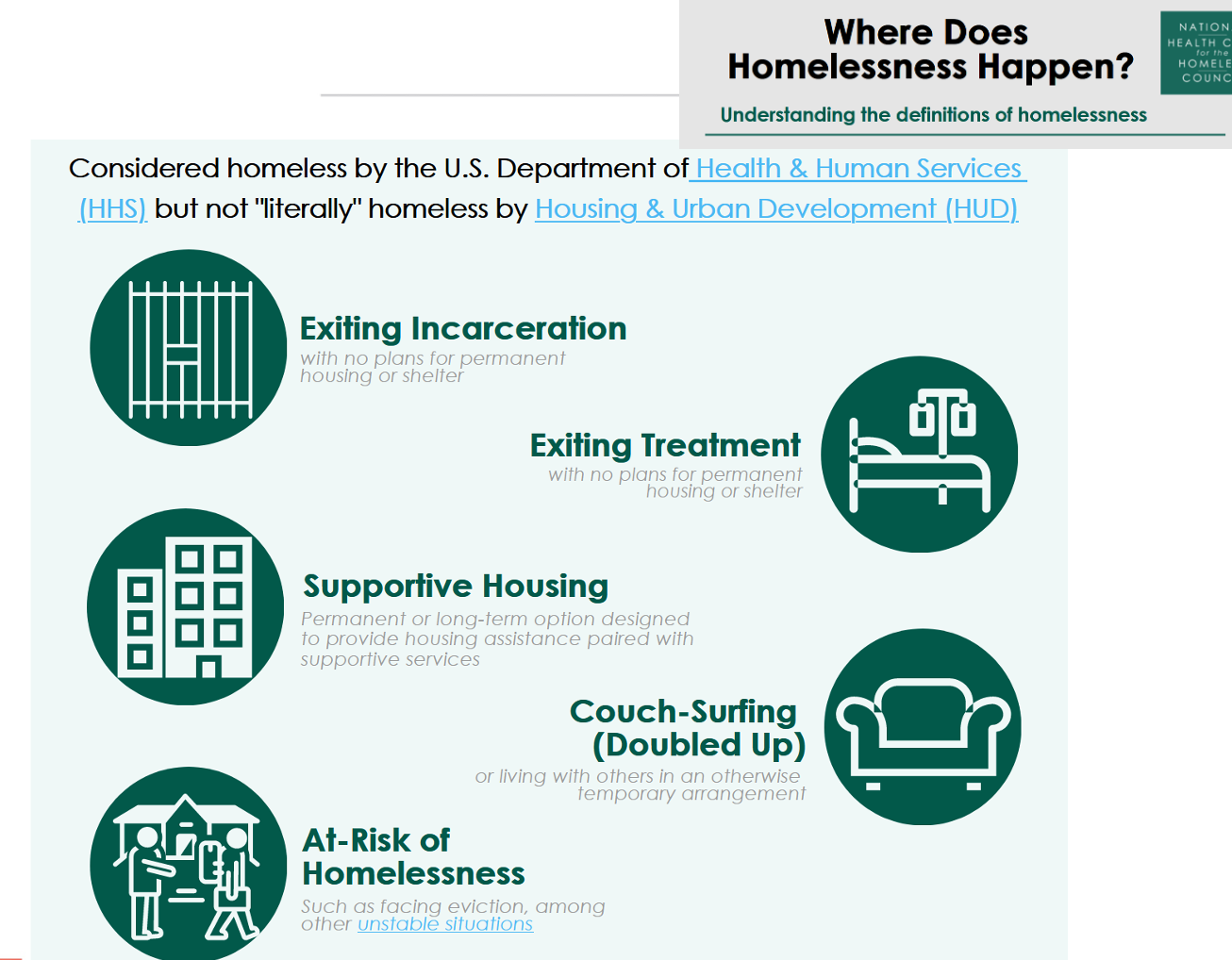

The Department of Health and Human Services (HSS) expands on the definition provided by HUD, as seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2. HHS definition of homeless (https://nhchc.org/where-does-homelessness-happen/). Click here to enlarge the image.

This definition includes folks who are exiting incarceration, substance abuse rehabilitation, hospitals, or skilled nursing facilities who have no place to go. HSS also includes individuals living in permanent supportive housing. Part of that is that individuals have had to experience homelessness to qualify for supportive housing, typically more chronically homeless for more extended periods. Health and human services also include them as they need access to some of the same services and support systems as those who are homeless. This definition also includes couch surfing or doubled-up individuals, and that term might change depending on the community. Couch surfing refers to those staying with different friends but do not have a consistent place.

HSS also identifies folks at risk of homelessness. This is especially critical with the eviction moratoriums being lifted across the country. Many people who have been unable to afford their rent and have not received some of the released benefits face a high likelihood of experiencing homelessness and losing their housing. And we are going to see those numbers grow significantly over the next couple of months.

These different definitions matter because whatever an organization uses to define homelessness will determine who is eligible for those services. HUD is the part of the federal government that oversees subsidized and permanent supportive housing projects and available funding. To access these resources, a person must meet the HUD definition of homelessness. The folks noted in Figure 2 may not necessarily be eligible for housing through HUD.

As you work in these spaces, it is essential to know who is eligible for certain services. The links are available here and in the references to be able to dive into that definition piece a bit more.

- Homelessness=Housing Instability

- "A recognition of the instability of an individual's living arrangements is critical to the definition of homelessness."

- Principles of Practice- A Clinical Resource Guide for Health Care for the Homeless Programs

- "A recognition of the instability of an individual's living arrangements is critical to the definition of homelessness."

The critical takeaway is that occupational therapists need to recognize that housing instability equals homelessness. If an individual does not have stable housing, they are at risk for many different issues that relate to the experience of being homeless. I will give some background on what we know from the literature about the health and occupational needs of people experiencing homelessness.

Health and Occupational Needs of People Experiencing Homelessness

- Chronic health conditions

- Cognitive impairment

- Traumatic brain injury

- Geriatric conditions

- Mental health diagnoses

- Substance use disorder

(Ayano et al., 2020; Baggett et al.., 2010; Fazel et al., 2014; NHCHC, 2019; Stubbs et al., 2019)

We know that people experiencing homelessness have significantly higher health conditions. To give some context, a publication from 2019 identified that people experiencing homelessness have diabetes and hypertension at two times the general population's rate. They are 30 times more likely to have hepatitis C. Fifty percent of people experiencing homelessness have experienced traumatic brain injury with a loss of consciousness compared to less than 10% of the general population. People experiencing homelessness are five times more likely to have a diagnosis of depression, three times more likely to have a substance use disorder, and are twice as likely to have a severe mental illness than the general population. They are more likely to experience geriatric conditions 15 to 20 years earlier than the general population and are more likely to have multiple chronic conditions. Those experiencing homelessness have pretty significant health needs. From the data and the research, we know that there is a strong correlational relationship that health conditions can cause homelessness. Homelessness can exacerbate and further cause additional conditions.

Factors Impacting Cognition in People Experiencing Homelessness

- Medical

- Developmental Disability

- HIV

- Substance use

- Serious Mental Illness / Mental Health

- Medical interventions or being in an ICU

- Chronic Conditions

- Environmental

- Unstable, unsafe, or inadequate housing

- Poor nutrition / Lack of access to food

- Sleep deprivation

- Trauma

- Stress

- Low literacy

(American Occupational Therapy Association, 2019; Lynch & Lachman, 2020; Wei et al., 2019)

Functional cognition is an essential piece of occupational therapy practice. It is critical within this practice setting because so many different things can impact and contribute to somebody's cognitive functioning. I outlined different medical conditions that occur at much higher rates in people experiencing homelessness. There is also the critical environmental piece. Cognition is impacted by whether or not you have safe, stable housing, adequate nutrition, adequate sleep, and safety.

Folks experiencing homelessness have increased rates of trauma, both PTSD and histories of trauma, and ongoing concurrent trauma from the experience of being homeless. Different from trauma is chronic stress.

There are also higher rates of literacy within this population, which can also impact overall cognition. One person may have multiple conditions and environmental factors that can affect cognition. There is often an assumption of decreased cognition impacting function and that people cannot take care of things for themselves. I want to change that perception by having you think about what would happen to somebody's cognition if they had housing, stable health, and adequate food.

A proper environment might improve cognition instead of assuming that somebody cannot do something. And part of the reason, as I noted that healthcare issues are sort of correlational with the experience of homelessness. People in poverty, especially those experiencing homelessness, have several significant barriers to accessing healthcare. Some of these barriers are exacerbated depending on the state and whether or not Medicaid was expanded.

Barriers to Health Care

- Cost

- Type or lack of insurance coverage

- Feeling labeled, stigmatized, or invisible to health care providers

- Previous experiences of trauma within health care

- Limited or poor transportation

- Lack of access to telephones & mail

- Inability to take time off work

- Feeling discriminated against

- Difficulty reaching their provider through the phone

- Forgetting the appointment

- Wait times at the office

- Difficulty scheduling an appointment

(Allen et al., 2017; Baggett et al., 2010; Cocozza Martins, 2008; Kaplan-Lewis & Percac-Lima, 2013; LeBrun-Harris et al., 2013; Magwood et al., 2019 Nickasch & Marnocha, 2009; Siersbaek et al. 2021)

Barriers to health care are environmental factors and a lower income or lower socioeconomic status. They may have limited access to transportation, computers, phones, et cetera. Telehealth is excellent, but only if you have the technology to participate in that. Insurance access and coverage change with the cost of medical care, but even for folks covered under Medicaid, there may be only certain providers in the community that will complete certain health services. This means that those clinics are very busy, and it can be hard to get an appointment or long wait times.

There is a lot of trauma from engagement with the healthcare system for people experiencing homelessness. This trauma includes having negative experiences, feeling stigmatized, and not feeling heard. Data shows that people get poor care in traditional medical and healthcare settings. Those experiencing homelessness feel discriminated against, and pain complaints are often not acknowledged. Many people have intersecting factors such as being a person of color and experiencing homelessness. This segment is even less likely to be listened to and experience more stigma and bias in healthcare settings.

As we deliver services, we need to know these biases and how they could impact care.

Daily Occupational Needs

- Survival

- Identity

- Social Connectedness

- Self-care

- Rest and Sleep

(Gonzalez & Tyminski, 2020; Illman et al., 2013; Marshall et al., 2017; Muñoz et al., 2006; Salsi et al., 2017; Thomas et al., 2017; Van Oss et al., 2020)

I will shift to thinking about the occupational needs of people experiencing homelessness. There is some interesting data and literature surrounding this once you delve into it. Several studies have found that the daily occupational needs of people experiencing homelessness center around survival, identity, social connectedness, self-care, rest, and sleep. We all need essential things to survive, feel well, and feel part of our community.

Occupations of Survival and Self-Management

- Occupations of Survival

- include occupations such as finding food, shelter, clothing, and a place to sleep in

- Occupations of Self-Management

- include occupations such as figuring out how and where to brush their teeth, shower, wash clothes, manage medications, secure housing, and schedule appointments

(Illman et al., 2013; Tyminski & Gonzalez, 2020)

There are "occupations of survival," which are the occupations centered around finding food and shelter. Do they have clothing, protection from the weather, and a place to sleep? Occupations of survival become prominent and things people have to focus on daily. This limits their ability to engage in other critical occupations.

There is also the idea of "occupations of self-management," which is not just doing ADLs but figuring out how and where to do them. Do I have supplies to take care of myself and my health? A simple activity like brushing your teeth is no longer a five-minute activity but can take up a more significant part of the day if you are looking for a space with water and supplies.

Factors Impacting ADL

- Disproportionate level of chronic illness and geriatric conditions that can be risk factors for functional impairment

- Premature functional impairment as compared with the general population

- Environmental barriers to engage in ADL affect all ages

(Abbs et al., 2020; Brown et al., 2017; Cimino et al., 2015; Fazel et al., 2014; National Institute for Medical Respite Care [NIMRC], 2021; Simpson et al., 2018)

There are also many limitations to self-care tasks. Expanding on the literature a little more, studies have found disproportionate levels of chronic illness and geriatric conditions, as mentioned earlier, that can increase the risk for functional impairment among people experiencing homelessness. Environmental factors and health conditions contribute to somebody's functional abilities and may impact this population earlier than we might see with the general population. For example, folks may have mobility issues or a higher fall risk at the age of 50 to 55 instead of 70 to 75. Data also suggests that these environmental barriers impact their ability to engage in ADLs at all ages, like persons who need more supportive things like durable medical equipment to do ADLs safely. One study looked at transitioning youth and found that even finding supplies for menstrual hygiene was difficult due to environmental barriers.

COPM Goals

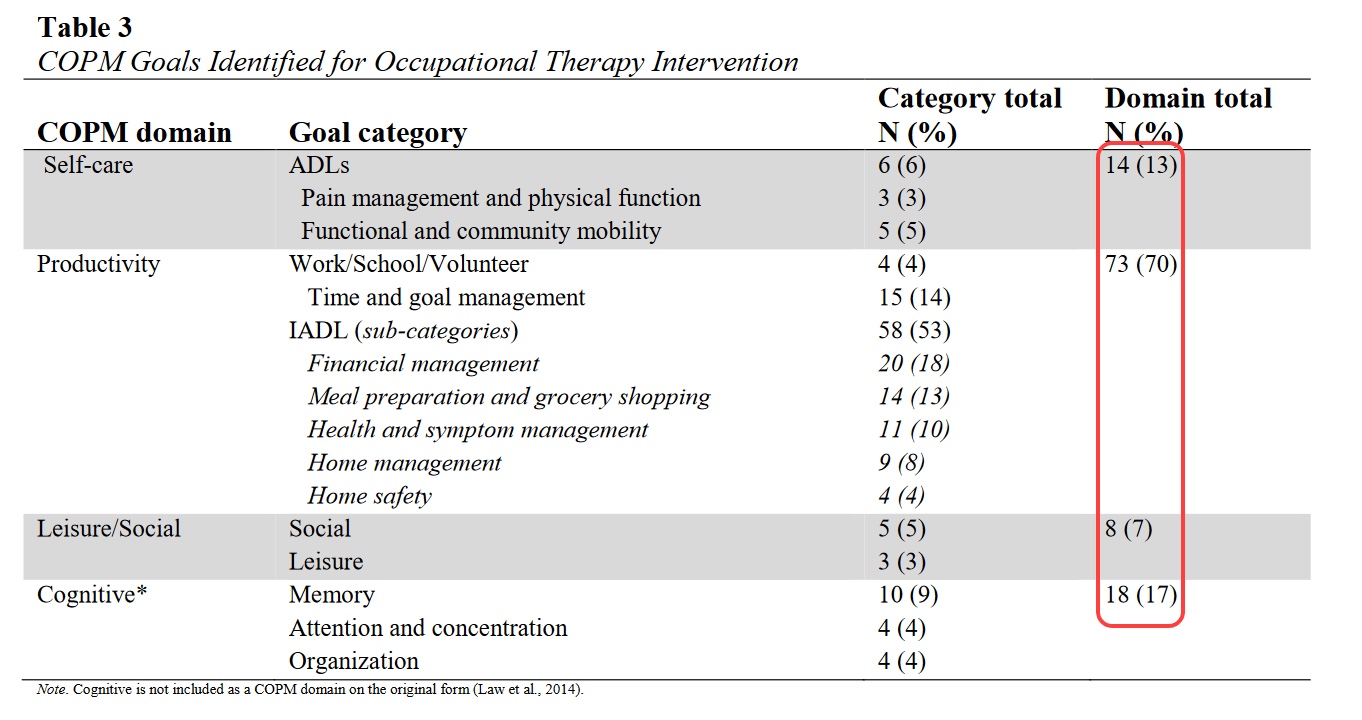

Another study used an occupational performance measure, The COPM (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Study using the COPM. Click here to enlarge the image.

The COPM is a client self-report where clients identify their own goals for care when working with an occupational therapist. Similar to the other studies, 13% of people who participated in OT services were focused on self-care goals. Still, most of those goals also looked at productivity as defined by the COPM. Specifically, 50% of participants in OT services wanted to focus on IADLs and not just the basic occupations of survival. This is where we see the self-management piece of managing health and finances with limited resources. What was also notable was a self-identified desire to work on cognition. People expressed difficulties with memory, attention, concentration, and organization, and they wanted the opportunity to work on them. This means that people are often generally aware of the decreased cognitive factors they are experiencing.

Transitions to Housing

- Time use

- Participation in meaningful activity

- Managing mental health and substance use

- Emotional growth and change

- Creating connection and community

(Helfrich and Fogg, 2007; Marshall et al., 2020)

Another set of studies focused on the role of OT and occupations for folks while transitioning into housing. A comprehensive resource by Dr. Carrie Ann Marshall and her team is linked in the reference list. Their research found that folks focused on their time use, meaningful activity, creating a connection with their community, being engaged where they live, focusing on emotional growth and change, and managing mental health and substance use needs. Studies are looking at building those skills and self-efficacy to feel prepared to move into housing.

Occupational Therapy and Addressing the Needs of People Experiencing Homelessness: Evidence & Approaches

I will give some background on theory and approaches before we get into sort of the nuts and bolts of what OT can do in these spaces.

- A mismatch between a person’s abilities and their environment results in functional impairment or exacerbates existing impairment.

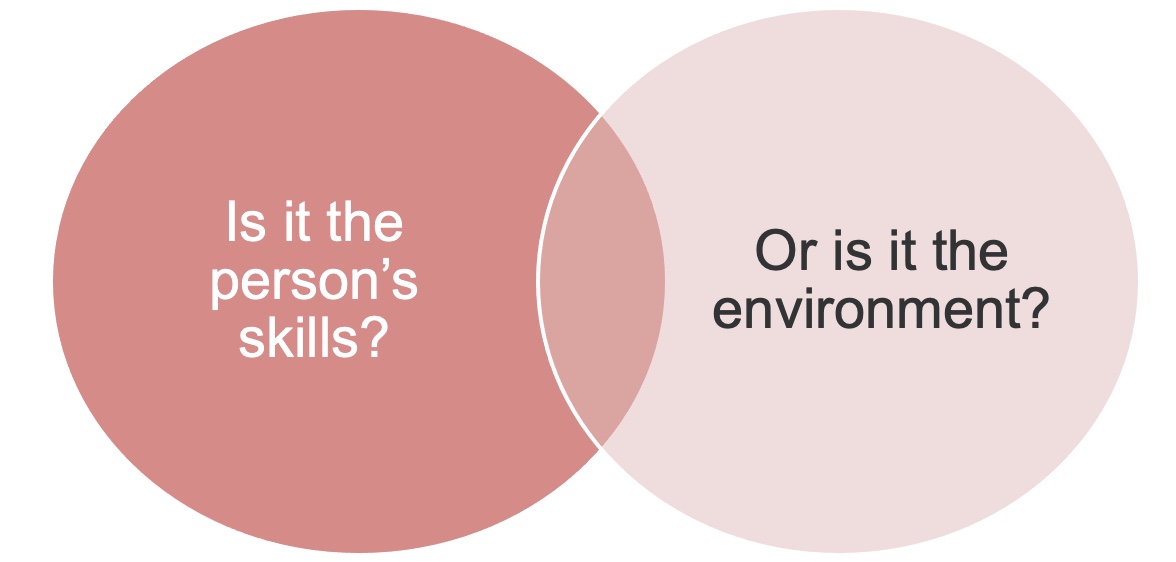

I love this quote, but it is not written by an occupational therapist. The HOPE HOME study is great (Brown et al., 2017). Often, people, especially in the US, think that homelessness is the individual's fault. They are homeless or struggling to maintain housing because of something they are doing like they cannot manage their money or their health. I want to reframe that.

Figure 4. Venn diagram looking at skills vs. environment (Brown et al., 2017).

Is it the person's skill limiting their functional abilities, or is it the environment where we are not giving people an opportunity to thrive? Are we not offering people the support that they need to do well? Help could be economical, structural, or access to basic resources. We need to examine both the personal and contextual factors driving some of the limitations. I noticed this a lot when I was working with folks on budgeting. People can do the math and layout an excellent budget, but it is hard to survive when you only make $600 a month, and a third of your income goes to rent. You are then surviving only on $400 for all of your needs each month. Is this a lack of budgeting or a lack of resources? Where are those gaps and deficits? It is certainly not always with the person.

Why do we need OTs in settings specific for people experiencing homelessness?

- Critical to be in spaces where people already access services

- Work within more trauma-informed environments

- Understand context impacting engagement

- Provide services in a way that best meets the needs of the population and individual clients

- Ability to combine and apply evidence using clinical reasoning –

- Most resources, assessments, and interventions are not developed with the needs of people experiencing homelessness or poverty in mind

Why are we talking about this regarding OTs working with this population? OTs are in the communities where people experiencing homelessness are. We are in the spaces where people may already be accessing services. We may also have the opportunity to work with them in trauma-informed instead of medically model-driven environments, where we can incorporate strategies to avoid some of the traumatizations from medical facilities. We can be where they are living and accessing services, and this helps to build our knowledge, awareness, and understanding of the context in which people live and how that affects routines. It also allows us to meet their needs where they are day to day. It helps us provide best practices.

Evidence Supporting OT's Role

- Evidence supports occupational therapy intervention to address function with:

- Mental Health & Substance Use

- Primary and Integrated Care

- Stroke & Brain injury

- Chronic Conditions

(AOTA, 2019; Ikiugu et al., 2017; Powell et al., 2016; Radomski et al., 2016; Synovec et al., 2020)

There is some evidence regarding OT intervention for people experiencing homelessness, but there is not much. Thus, we need to use our clinical reasoning to adapt things appropriately for the people we serve. There is a lot of evidence about OT working with people with mental health and substance use diagnoses and the role of OT in primary and integrated care settings. There is also research on folks with comorbidities such as stroke, brain injury, and chronic conditions. However, all of this is not specific to people experiencing homelessness, but this research can serve as a foundation for developing our role in this setting.

Trauma-Informed Care (TIC)

- Realize the widespread impact of trauma and understand paths for recovery;

- Recognize the signs and symptoms of trauma in patients, families, and staff;

- Integrate knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and practices; and

- Actively avoid retraumatization

(Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration, 2014)

Trauma-informed care could be its educational session, but there are four key components for providing trauma-informed care identified by SAMHSA, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration. There is a widespread impact of trauma across the general population and people experiencing homelessness.

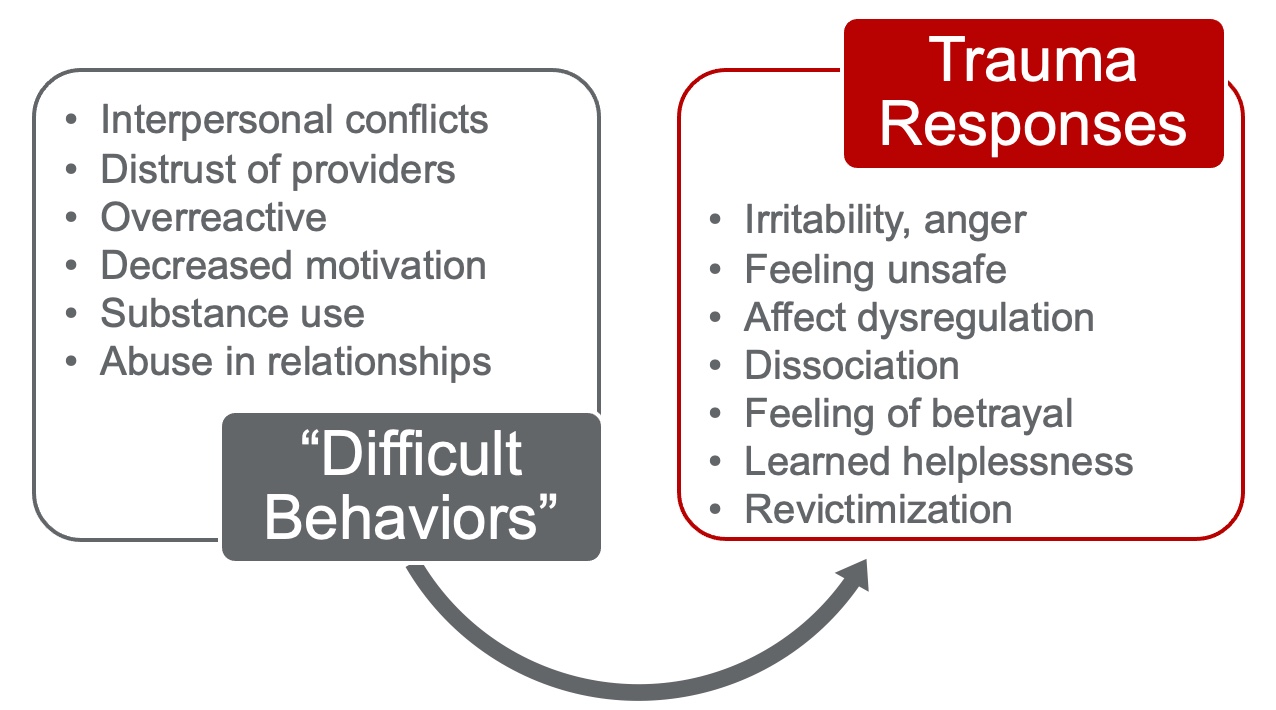

To be able to recognize the signs and symptoms of trauma that may prevent someone from engaging in services, we need to change what we are doing to make ourselves more accessible. When we integrate knowledge about trauma into the services we provide, we avoid retraumatization. We need to recognize challenging behaviors and resultant trauma responses (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Difficult behaviors and resulting trauma responses.

Many times we may think that someone is not adherent or non-compliant. There is also a lot of negative terminologies to describe someone going through a trauma response. For example, if somebody is irritable or expressing anger, they may have internal stuff like not feeling safe or knowing how to communicate well. They may not think they are being heard or respected. When working with this population, we may have to reframe our thinking. Those experiencing homelessness have people come and go in and out of their lives very quickly, especially service providers. Thus, they may not want to give you the details of their lives. If you are interested in working with this population, I recommend doing some reading and training on trauma-informed care.

Harm Reduction

- Harm reduction incorporates a spectrum of strategies that includes safer use, managed use, abstinence, meeting people who use drugs “where they’re at,” and addressing conditions of use along with the use itself.

- Demands that interventions and policies designed to serve people who use drugs reflect specific individual and community needs

- A set of practical strategies and ideas aimed at reducing negative consequences associated with drug use.

(National Harm Reduction Coalition, 2021)

Similarly, harm reduction is another helpful paradigm when working with people experiencing homelessness. Harm reduction is developing a spectrum of strategies that promotes a safer way to manage drug use. This may include abstinence and ways to meet people using drugs where they are in the moment. There is a little bit of a misnomer that harm reduction is not about abstinence; however, abstinence is not the only practical strategy in this paradigm. Ultimately, we want to decrease the risk and increase safety for people who may be using drugs or alcohol, especially in less healthy ways.

Thinking more broadly, how do we ensure that we meet the client where they are? I might have a beautifully planned intervention laid out and ready to go, but if they come in and have not slept or eaten in several days or something else traumatic has happened, I need to be prepared to respond to that and care for the person at the moment. We need to be willing to work with people who may be safely using substances and not say, "You do not get OT services." We want to engage them in a way that promotes their safety.

Harm reduction aligns with OT because it is driven by people with lived experience and focuses on engaging them in the community.

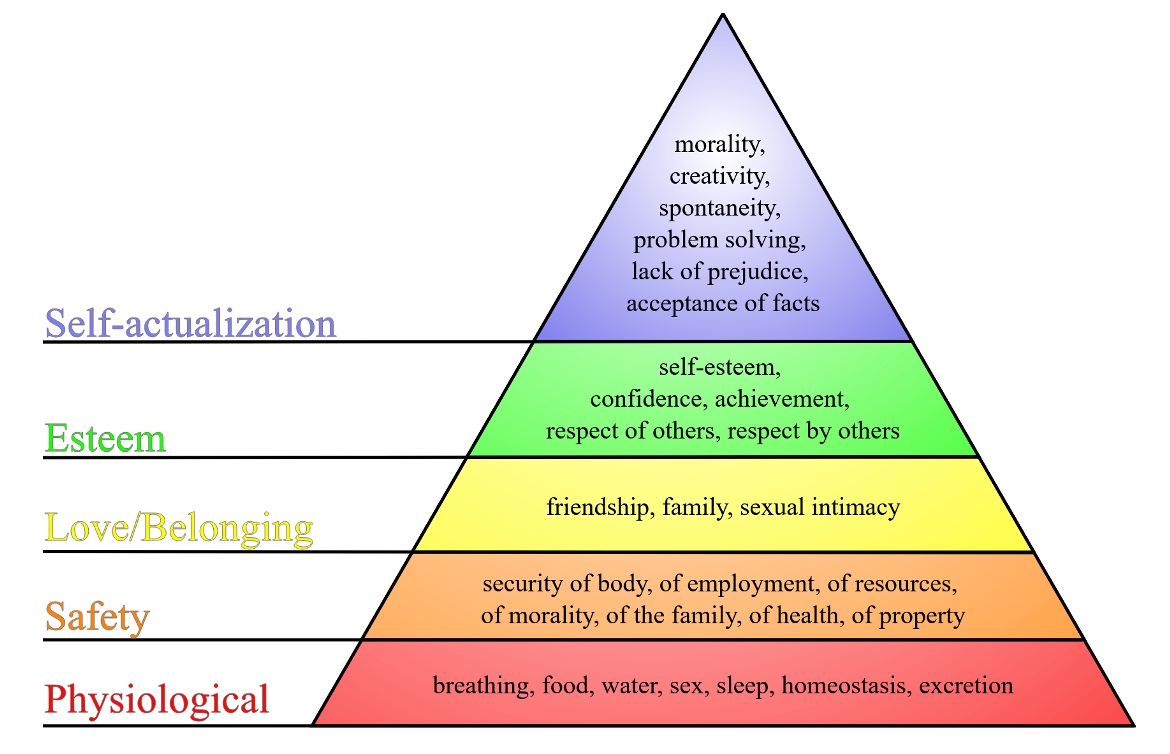

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Figure 6 shows Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs.

Figure 6. Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs. J. Finkelstein, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/>, via Wikimedia Commons

To achieve higher-level needs such as belonging and self-esteem, basic needs must be met. We need to rest, eat, and feel safe. We cannot be sleeping outside during a hurricane or a massive weather event. This is not to say that a person experiencing homelessness does not have their needs met or cannot achieve higher-level areas. We just need to recognize how these unmet baseline needs might be driving the experiences or the way that somebody is interacting.

TIC, Harm Reduction, & People Experiencing Homelessness

Bringing all these concepts together is trauma-informed care and harm reduction.

- TBI/Cognitive Impairment

- Substance Use

- Lack of safety and housing

- Health needs

- Trauma

Any time we add a “requirement” for services and basic needs, we limit people’s ability to access safety, self-care, and change.

The client is managing all of these different things every single day. How can we reduce the impacts of some of these? Again, we need to meet the person where they are and try to reduce any barriers. Also, think about how many requirements are in place to get services. We limit a person's ability to access safety, self-care, and change when we do that. How can we reduce the barriers to receiving OT services, and how can OT help minimize the barriers to engaging in environments?

Occupational Therapy and Addressing the Needs of People Experiencing Homelessness: Strategies & Settings

The meat of this presentation will be on strategies and the settings in which people are accessing services.

Where do individuals engage with services?

- Shelter

- Emergency Shelter

- Transitional Shelter

- Permanent Supportive Housing

- Health Care

- Health Centers

- Street Medicine

- Medical Respite

- Basic Needs

- Drop-in Centers

- Meal Programs

- Resource Centers

*Integrating OT into these spaces reduces barriers and increases access to care.

There are three places where people get services that I have generalized broadly for today's presentation. There are shelters, health care, and basic need areas. As we put OT into these spaces, we reduce barriers and increase clients' access to care. Before I get into the settings, I will go over a broad overview of what OT looks like with people experiencing homelessness. Then, we will hone in and talk about each of these settings and the different interventions that are most appropriate for that setting and why.

Adaptations and Strategies for ADL

- Adaptive equipment that can be easily stored and used independently

- Alternative methods (wipes, dry shampoo)

- Easily removed modifications

- Access to supplies and low-cost alternatives

- Advocacy for accessible restroom spaces

- Identify supports for DME that can be used within contexts

For activities of daily living, we are thinking about different adaptations and strategies to support people. There are a lot of barriers, so what can we do to make this easier and accessible. For people who need durable medical equipment, you want to recommend simple things that can be easily carried around and implemented in various spaces. When someone is moving all of their belongings with them all of the time, oversized heavy items will not be most appropriate.

We also want to give recommendations on supplies that are low-cost or alternative. For example, if someone cannot safely bathe in the showering facility at the shelter because of mobility limitations, can you minimize their risk and harm by recommending baby wipes or washing up at the sink? We also want to think about adaptive equipment that can be easily removed and easily accessed.

IADL Skill Development

- Meal Preparation

- Grocery Shopping

- Meal Planning

We want them to work on meal preparation, planning, and grocery shopping centered around specific health needs for instrumental activities of daily living. There is also a secondary benefit to working on new related skills during non-COVID times. Eating together is a valued social activity for most people and being able to do that and build that community is great.

Here are some photos of people doing IADLs. Many pictures of folks smiling during cooking and meal preparation groups and activities (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Individuals participating in IADLs.

- Management

- Routines

- Goal Setting

We also want to think about health management, including medication management, as it is a difficult skill. OT has a lot to offer to help people figure out how to manage their medications well. Examples of this area are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8. Individuals working on medication management.

Developing routines, goal-setting, prioritization, I can't get everything done that I need to get done during a day, how do I decide what that is and what that needs to be, and simplified strategies for that such as pillboxes or as you can see the gentleman here really loved having just a folder with blank pages that he could use to develop his routine and write out his goals for himself day-to-day.

Leisure and Social Engagement

- Meaningful participation

- Identification of interests

- Connection with social supports

Sometimes leisure is considered less necessary when thinking about the occupations of survival. People experiencing homelessness have limited opportunities for meaningful participation, chosen social interaction, and healthy engagement, especially when societies and communities are not welcoming. What do you like to do is a question that people do not get asked a lot. This also allows us to weave in skills around developing cognitive skills or learning to navigate new mobility limitations. This is not always accessible to this population.

Figure 9. Leisure exploration with people experiencing homelessness.

The photo on the left are gentlemen who worked as landscapers at earlier times in their lives. Planting and greening the shelter space where they were staying was incredibly meaningful for them.

Environmental Modifications

- Accessibility of Spaces

- Physical and ADA accessibility: entrances, showering, and self-care spaces

- Cognitive: ease of wayfinding, location, and flow

- Orientation to schedules and staff

- Services and Systems

- Health literacy level and accessibility of printed materials

- Navigation and removing barriers to access services

Many environments and contexts are not accessible and welcoming for people experiencing homelessness. Shelters are often older buildings or donated spaces that are not very accessible, and there are not a lot of funds to change that. Can we do an environmental scan and identify how to make spaces safer for mobility and wayfinding? We talked about cognitive factors in this population due to different disorders and even sleep deprivation. Is it easy for them to navigate through the building? Who do they call in case of an emergency? We can help these people figure out who to talk to and what resources are available.

We also want to think about their health literacy levels. Are our materials accessible to those with different abilities? We want to think about ways to remove barriers to services through activity and environmental analysis.

We will use one case example, and as we talk through each of these settings where OT might work, please think about Kevin and how OT might engage with him in each space.

Case Example- Kevin

- Kevin (he/him) is 58 years old and has been experiencing homelessness for the last 6 years.

- Prior to experiencing homelessness, Kevin worked for a landscape company where he oversaw multiple projects as well as completed manual work. Kevin lived alone in an apartment and also helped care for his mom who lives nearby. Kevin primarily socialized with his friends from work, whom he had known for several years.

- His medical history includes a transient ischemic attack (TIA) when he was 50, where he was treated with an overnight hospitalization and discharged back home. Following the TIA, Kevin noticed changes in his memory and “keeping up with work,” as well as feeling weaker and less coordinated.

- Kevin’s ability to work was declining, resulting in multiple conversations with his boss over his performance.

- At age 51, Kevin’s mom passed away unexpectedly, and he was overwhelmed by the responsibilities of managing her small estate as well as his grief. Kevin, who had primarily only been a social drinker of alcohol, began drinking more frequently and heavily.

- Kevin began to experience depression, which further impacted his work. He was eventually let go from his position due to several missed days of work along with continual struggles to complete his duties.

- Kevin eventually left his apartment after being unable to find additional work and running out of his small savings. He moved some of his belongings into a nearby storage facility and slept overnight in his car.

- Kevin had lost touch with his friends from work and was too embarrassed about his circumstances to reach out to others. When Kevin’s car broke down, it was towed from staying parked too long in a lot, and Kevin began staying at a local homeless shelter.

Everybody's story is unique, but there are a lot of characteristics to this example that are common to those experiencing homelessness. Keep Kevin in your mind as we go through these few slides about the different settings where OTs can engage in work.

Emergency Shelter

Overview

- Any facility where the primary purpose of which is to provide a temporary shelter for the homeless in general or for specific populations of the homeless and which does not require occupants to sign leases or occupancy agreements.

- Emergency shelters are often where people experiencing economic shock first turn for support through a wide range of services.

(SAMHSA, 2021)

The first place people who suddenly experience homelessness go is an emergency shelter, a temporary place to stay.

- Shelter environments and practices may vary by setting including:

- Services offered onsite

- Staffing

- Use of harm reduction and/or trauma-informed practices

- Criteria for staying within the shelter

- Accessibility

- The National Alliance to End Homelessness: “5 Keys to Effective Emergency Shelter”

- Housing First approach

- Safe and appropriate diversion

- Immediate and low-barrier access

- Housing-focused, rapid exit services

- Data to measure performance

(National Alliance to End Homelessness, n.d.)

Shelters may be open to anyone experiencing homelessness, or they may be specific to certain populations such as veterans, older adults, and gender. The idea is that a person can come and sleep overnight and not need to sign a lease, pay money, or sign an occupancy agreement. Shelter environments and practices are often variable based on who is running the facility. For example, religious institutions and organizations may run a shelter setting and have specific criteria or certain roles. For example, certain shelters may not allow anyone to use substances or drink. Some shelter settings charge a small fee to stay there overnight or secure a bed, usually less than $5. And, some shelters require individuals to be there by three o'clock in the afternoon or a particular set time to access the bed. Some guarantee that folks have a bed overnight, while others are first-come, first-serve. There is a lot of variety driven by funding, who is running it, and how the community is engaged with this resource.

As I mentioned, they are not always the most accessible spaces. They can be in older buildings, or the real estate is not as profitable; thus, access to the building may be more challenging. There can be stairs or other renovations that need to be done.

The National Alliance to End Homelessness has five key recommendations for an effective emergency shelter. This includes a housing-first approach, which we will talk more about in a moment, and a safe and appropriate diversion, which is recognizing when homelessness can be intercepted early and getting somebody into an alternative space other than a shelter. They also recommend low barrier access, which means there are not a lot of criteria for eligibility to stay in a shelter. Unfortunately, not all shelters follow this for the reasons I just mentioned. The last two criteria are housing-focused/rapid exit services and data to measure performance.

Shelters – Role of OT

- Environmental modifications

- Assessment of needs

- Skill building

- Appropriate services and resources

- Short-term interventions

- DME

- ADL training

- Self-management within shelter space

- Housing transition preparation

- Navigating community resources

When thinking about the role of occupational therapy within the shelter environment, there are a few things that we want to consider. One is that if it is not a shelter where people have a secured stay, an occupational therapist may not be able to interact with a person for an extended period. It may be a brief interaction with only a couple of sessions. The shelter environment may be chaotic. Most are congregate, which means there may be 100 beds on a floor. There may only be one or two group spaces where people can spend time, but there may be 50 individuals in there at a time. It can be loud, and there is not a lot of privacy.

One of the biggest things is the environmental modification piece. We want to make the space accessible as cheaply as possible. There are people with all sorts of diagnoses and disabilities. We may need to set up private spaces for health management, make minor adaptations to prevent falls in the bathrooms and showers, and create organizational spaces around shelter beds. There are a lot of really great ideas that we can implement.

Suppose you are working individually with the client. In that case, you do an individual assessment of need and prioritize things like skill-building that can be achieved during brief interactions or over a short time. We also want to make sure folks are connected to appropriate services and resources which could divert or prevent more chronic homelessness. For example, if somebody is identified as having a significant cognitive impairment, they may be eligible for earlier services, such as social security payments or specific housing settings. OT can help identify needs and support these cases. We also need to think about ADLs and durable medical equipment for those transitioning into housing. We can allow them to practice skills and navigate resources.

Case Example

- Thinking back to Kevin … what OT interventions and services may be helpful for him within the shelter setting?

- Identifying functional barriers

- Cognitive assessment

- Addressing self-organization

- Managing routines

- Developing skills to engage within a shelter setting

I would first want to know his functional barriers. He noted some weakness and some loss of motor control. We might want to prioritize this and give him some strategies around that. We would certainly want to do a cognitive assessment as he identified some issues with memory and see how that impacted his ability to engage in services. He also said he had difficulty with organization at work. We want to know his functioning in the shelter and his ability to manage his belongings, especially high-priority items such as a phone or ID. Is he able to find what he needs and take it with him? Managing routines is a more complex cognitive skill. Can he develop appropriate routines? Again, he might have difficulty in a setting that is a little bit more chaotic, that is less predictable, or has rigid rules. He will also need to develop skills to engage in relationships in the shelter setting to know who are safe social supports.

Transitional Housing

Overview

Transitional housing is often a bridge between living within a shelter setting and permanent long-term housing. Typically, folks engaged in a transitional housing program can live there for up to 24 months. The goal of transitional shelters is to provide more supportive services to help the person move and stay out of homelessness. They also focus on employment, building community connections, stabilizing health, and developing functional skills to maintain housing. This looks at all the different barriers and identifies other economic resources appropriate to support long-term housing.

Transitional Housing- Role of OT

- Assessment of skills and needs for transition into housing

- Developing routines

- Identifying and addressing needs that may not have been addressed or have been de-prioritized prior to housing

- Housing preparation and transition

- IADLs: home management, safety, community navigation, budgeting

(Helfrich & Fogg, 2007; Marshall et al., 2020)

When we think about OT services in this setting, it shifts a little bit from a basic shelter setting. Most folks that engage in transitional housing have a more direct pathway to accessing housing. OTs complete an assessment looking at their skills and needs to transition into housing. After only focusing on "occupations of survival," these individuals now have ownership over their own time. They need to redevelop routines and skills. "Now that you are not working on basic survival, what is a priority? What hasn't been addressed, or what would you like to do at this time? Housing preparation is one area to work on with the individual. Not everyone experiencing homelessness lacks the functional skills to manage an independent apartment. For example, in the case of Kevin, he has lived independently before. There may be areas that somebody needs to adapt and modify, or they may need to identify supports.

Case Example

- Thinking back to Kevin … what OT interventions and services may be helpful for him if he had been able to access a transitional housing program?

- Assessment of functional needs

- Cognitive assessment

- Identifying social and leisure needs

- Developing new routines

- Addressing cognitive concerns

What OT interventions might you do with him if he transitions from a shelter setting into transitional housing? First, we would assess functional needs. He may need help with budgeting due to recent cognitive issues. We want to work on skill-building, adaptations, and compensatory strategies and help him to develop new routines. If he experienced homelessness for six years, he did not necessarily have a lot of established routines given his circumstances. With a more stable setting, we can also address some cognitive concerns.

Permanent Supportive Housing

Overview

- Increases access to permanent housing and provides ongoing supports and services to assist clients in maintaining housing

- Key components include:

- Trauma-informed care

- Harm reduction

- Address economic/monetary barriers to housing

- Mental health and substance use treatment

- Services are provided at the direction of the participant/client

(Helfrich & Synovec, 2019; Marshall et al., 2020; Synovec et al., 2021)

You most likely rent an apartment or live in a home. Permanent supportive housing is a little bit different than that. Because it is permanent housing, individuals have their name on a lease, but it also provides some wraparound ongoing support and services to assist clients in maintaining housing. Not everyone who is experiencing homelessness needs permanent supportive housing. Sometimes folks just need permanent housing; however, many people benefit from permanent supportive housing because of the intensive case management and ongoing support for behavioral health. Key components of permanent supportive housing are trauma-informed care and harm reduction practices. They also address economic and monetary barriers to housing. Individuals can also have subsidized housing where their rent is based on their available income, usually lower than fair market rent. There can also be mental health and substance use treatment, but they are not required to participate to access this housing. The idea is housing first and that every person deserves a place to live, and there are no barriers to participation. This model is incredibly effective across multiple high-level quality studies.

PSH-Role of OT

- Assessment of priorities and needs

- Long-term skill building for IADLs

- Home management, meal prep & shopping, budgeting

- Health management

- Access and navigation of systems

- Symptom management

- Home safety & environmental modifications

- Community integration

- Developing habits and routines

Permanent supportive housing is more familiar OT territory as we can work with people long-term in their homes and in the communities where they live. We start with their needs and priorities. We can work on home management, meal prepping and cooking in their space, shopping at their nearby grocery store, and budgeting based on their rent. Indeed, health management comes into focus here. Again, people cannot address some of their health conditions until they are stable housing. Long-term symptom management is another space for OT. We can also look at home safety and environmental modifications. Similar to the shelter, modifications must be simple, affordable, and removable. Rented apartments do not always allow permanent structures or things to be drilled into walls. We need to be creative about increasing safety. Lastly, we need to help them integrate into the community, build social networks, and develop habits and routines now that the occupations of survival and self-management are no longer the priority.

Case Example

- Thinking back to Kevin … what OT interventions and services may be helpful for him if he had been able to transition to permanent supportive housing?

- Assessing functional needs with transition

- Compensatory strategies for cognitive needs

- Social and leisure engagement

- Developing new routines

- Community navigation and accessing resources

What might you do with Kevin if he transitions into permanent supportive housing? This looks similar to transitional housing. Sometimes with transition, external supports decrease. They do not have staff around all of the time. People may need to develop compensatory strategies to help manage their routines and any cognitive needs. Can they put post-it notes with reminders now that they have a fridge? They may now be able to engage in social and leisure engagement. Kevin, who lost social support and contacts, may be able to reengage with them. People do not always move to neighborhoods with which they are familiar, so it is essential to make sure people are familiar and comfortable with using bus lines and finding the grocery store and the pharmacy.

Now, we will shift from the housing settings into the healthcare settings.

Health Care for the Homeless

Overview

- Increases access to primary health care provides wraparound support services to address health and housing needs

- Key components include:

- Flexible service delivery – “no wrong door”

- Implements harm reduction and trauma-informed care

- Outreach services

- Co-located, integrated, & interdisciplinary, including access to social services

- Support access to secondary and tertiary medical care

- Inclusion of consumer advisory boards

The key components of health care are to increase access to primary care and wraparound support services, and address health and housing needs. Healthcare for the homeless is different from other primary care settings. It is integrated care and often includes a case management component, including in-house behavioral health and substance use treatment. They want people to access their services within a flexible service delivery not provided in traditional medical settings.

There are also outreach services with mobile units and vans. Another key component is the inclusion of consumer advisory boards and valuing people's experiences. There are over 330 healthcare centers for the homeless across the United States. If you go to our website, there is a resource at the end where you might be able to find one near you.

Health Centers

- Comprehensive primary care services, including via telehealth

- Specialty services (often by referral)

- Case management & behavioral health

- Shelter-based services

- Services in Permanent Supportive Housing

- Medication-Assisted Treatment and other SUD services

- Street outreach/medicine

- Medical respite/ recuperative care

- Trans & LGBQ+ affirming care

- “Enabling services” (e.g., transportation, interpretive services, legal partnerships, etc.)

- COVID testing and vaccinations!

These are examples of all of the different types of services but not every HCH offers all of these services. However, many provide several components of this, and they cross-cut some of these other services, such as operating a permanent supportive housing team. In some cases, they have supportive housing apartments, which is fantastic.

HCH- Role of OT

- Assessment

- Identification of skills

- Informs and supports access to benefits

- Contributes to care planning

- Health management

- Collaboration with health providers

- ADL

- Compensatory strategies based on environment

- IADL

- Relevant to contexts

- Transition to housing

(Synovec et al., 2020)

When we are in a health care setting, our role shifts. You will likely be working with people experiencing homelessness, but as part of the HHS definition, you will be working with people in a permanent supportive housing program. The possibilities are extensive. There is an assessment to identify skills as part of an interdisciplinary care team. A care plan is then developed for the individual, including helping them access benefits. Figure 10 is an example of the author working in this setting.

Figure 10. Author working in a health care setting.

Unfortunately, it is not a strengths-based process but rather a process of identifying the support somebody needs to access services. Much of health management breaks down barriers to taking medications, managing health, working on health literacy, and providing instruction through activity analysis. We want to make information digestible and usable. We need to work on ADL alternatives for showering and caring for themselves for those not in housing. As we noted in the COPM study earlier, there is a lot of variety of what people want to prioritize and work on within their contexts.

Case Example

- Thinking back to Kevin … what OT interventions and services may be helpful for him if he was receiving services at a Health Care for the Homeless Program [while staying at the shelter]?

- Assessment of functional needs/barriers

- Cognitive assessment

- Identifying and addressing health management

- Intervention to support functional needs identified

- Supports to engage with community resources

- Referral to other providers

Again with Kevin, we would look at functional needs, barriers, and cognition no matter what setting. You might focus a bit more on health management. He had a TIA, so there are probably some existing medical conditions. Can we prevent something further from happening cardiovascularly? Can we adapt our ADLs for some physical limitations? We also want to help him identify community resources and refer to other providers as needed. Is he experiencing grief and trauma from losing his mom? The OT might be the person who hears this first and directs them to behavioral health or peer support services to address that.

Medical Respite/Recuperative Care

Overview

- Post-acute care for people experiencing homelessness who are too ill or frail to recover from an illness or injury on the street or in shelter, but who do not require hospital level care.

- Short-term residential care that allows people an opportunity to rest, recovery, and heal in a safe environment while also accessing clinical care and support services.

- Key Components include:

- Clinical Care

- Integration into primary care

- Case management

- Self-Management support

- Diversity of Programs

- "Bed number

- "Facility type

- "Length of stay

- "Staffing and services

- "Referral sources

- Admission criteria

(NIMRC, 2019; 2021)

Medical respite is post-acute care for people experiencing homelessness or who are too frail or ill to recover from an illness or injury while in the shelter but do not require hospitalization. Many individuals enter medical respite programs after hospitalization or going to an emergency room with an acute medical need. They can be discharged to medical respite to do the care that most of us would do at home with support from our caregivers. They have access to a bed 24/7 and can rest and engage in self-care and health management.

Key components of this are not just providing a space to do health management, medical care, and case- and self-management support. These programs vary depending on how they look by the community and what types of staffing are available. These key components are a straight line through all of the respite programs.

MR/RC – Role of OT

- Assessment

- Client priorities, cognition, functional skills (e.g., health management)

- Short-term individual interventions:

- Health management

- Housing transition and community engagement

- Care coordination

- Time and self-management

- Population Interventions

- Establishing routines

- Falls prevention

- Advocacy

(Synovec et al., 2021)

This setting is a little bit different than the health center. It is going to be more medically focused. The average length of stay in a medical respite program is 30 days. This is more like a traditional medical OT setting, where you identify a couple of key skills that you will work on, primarily focused on health management, community engagement, and time and self-management to work around some of the new demands. You may also be able to work on environmental modifications, healthy routines, falls prevention, safety, and general advocacy in this setting.

Case Example

- Thinking back to Kevin … what OT interventions and services may be helpful for him if he was receiving services at a medical respite program – after experiencing a fall in the community and recovering from multiple fractures?

- Assessing functional skills/barriers

- Cognitive assessment

- Providing and training for DME

- Adaptations for ADL

- Addressing health management

- Engaging in meaningful activity

Suppose Kevin sustained a fall in the community and went to a medical respite setting with fractures. In that case, we will look at functional skills and barriers to functional performance with this new medical problem. We want to focus on things that can be accomplished in a 30-day timeframe. These include ADL adaptations, durable medical equipment, health management needs, and engaging in meaningful activity as part of the recovery process.

Drop-in Centers & Day Shelters

Overview

- “Soup kitchen” – “meal program” – “warming center” – “cooling center”

- Offer a range of services based on community resources and needs:

- Meals

- Hygiene and ADL resources

- Onsite case management

- Groups

- Safe place to spend time

- Leisure/social activities

Drop-in centers do not provide a place for people to stay. They just focus on basic needs. They might be called a soup kitchen, a meal program, a warming center in the wintertime, or a cooling center in the summertime where people can get respite from the weather. These are variable and not necessarily recommendations on what makes a good or evidence-based drop-in center. They provide services such as meals, access to hygiene, or a place for people to shower or do laundry. Some of the programs have case managers to help connect people to resources. They also might offer groups that are activity- or education-based. Ultimately, it is a safe place for people to go during the day.

Drop-in Centers – Role of OT

- Assessment specific skills and to identify priorities

- Meeting immediate needs

- Navigating resources

- ADL and DME

- Preparing for transition

- Engagement in meaningful activity

- Building trust and engagement

- Facilitates long-term engagement for intervention

- Engaging in meaningful activities

- Groups

- Housing transition

- Community and resource navigation

Similar to a shelter space, you may only encounter people once or twice because of how they access these services. These are going to be short-term interventions working on environmental adaptations or accessibility. We want to identify the person's priorities and immediate needs. How can they access the services in that space? What's bringing them there? How can we connect them with essential things and resources in the community, preparing for transition? Can we engage them in meaningful activity and provide a safe and relaxing space for positive mental health? It is vital to build trust and engagement, which can become long-term intervention as they are more likely to come back and see you more frequently.

Case Example

- Thinking back to Kevin … what OT interventions and services may be helpful for him if he was attending a drop-in center for support?

- Assess functional barriers/needs

- Cognitive assessment

- Identifying resources he may be eligible for based on assessment

- Engaging in meaningful activity and social engagement

Again, a drop-in center is a little more simplified. The assessment piece is the same, but we are identifying what resources he might be eligible for or should be accessing. It is a little less intensive and not focused on long-term goals.

Street Medicine

- Street Medicine includes health and social services developed specifically to address the unique needs and circumstances of the unsheltered homeless delivered directly to them in their own environment.

- The fundamental approach of Street Medicine is to engage people experiencing homelessness exactly where they are and on their own terms to maximally reduce or eliminate barriers to care access and follow-through.

- Visiting people where they live – in alleyways, under bridges, or within urban encampments – is a necessary strategy to facilitate trust-building with this socially marginalized and highly vulnerable population.

- In this way, Street Medicine is the first essential step in achieving higher levels of medical, mental health, and social care through assertive, coordinated, and collaborative care management.

(Street Medicine Institute, 2021)

The last setting is street medicine. Street medicine teams are teams made up of medical professionals that go out and meet people where they are in the community. These groups of people experiencing homelessness do not feel safe accessing services in shelters or health centers. They provide services to those living outside, encampments, or abandoned buildings.

Street Medicine- Role of OT

- Identify occupational needs and priorities

- Occupational profile

- Cognitive screening

- Brief functional assessment

- Support to identify and navigate community resources

- Provision of supplies

- Basic needs

- ADL supplies, adaptive equipment, medical needs

- Skill development

- Self-management of health and conditions

- Budgeting

- Sleep hygiene

(Tamberrino, 2021)

The role of OT is emerging and new in street medicine. A few folks are doing excellent research and needs assessment in this area. Similar to other OT settings, we will look at occupational needs and priorities in this brief encounter. If you develop a trusting relationship, the person may be willing to meet with you multiple times. You may try to address sleep hygiene and health condition management while on the street.

Case Example

- Thinking back to Kevin … what OT interventions and services may be helpful for him if he had been encountered by a street medicine team while staying in his car?

- Sharing knowledge of resources

- Cognitive assessment

- Identifying progression of health concerns

- Connection to community services

- Supports to adapt and complete ADL

If Kevin was staying in his car and was encountered by the street medicine team, they may share resources, identify concerns, or provide education and recommendations. You can get into more complicated sessions as you build up a trusting relationship. You are just helping them meet the occupation of survival.

How To Get Started

- Identify organizations at work in the community

- Identify needs and priorities, including consumers and existing staff/providers

- Identify gaps and how to supplement with distinct OT services

- Collaborate and implement services

To get started, you want to identify who is doing this work in your community? What are the needs of the people who are accessing resources? How can you fill that gap? What unique lens can OT bring to those services?

Resources

National Health Care for the Homeless Council

- The National Health Care for the Homeless Council (NHCHC) is the premier national organization working at the nexus of homelessness and health care.

- Grounded in human rights and social justice, the NHCHC's mission is to build an equitable, high-quality health care system through training, research, and advocacy in the movement to end homelessness.

www.nhchc.org

National Institute for Medical Respite Care

- NIMRC is a special initiative of the National Health Care for the Homeless Council whose primary focus is on expanding medical respite (or recuperative) care programs in the U.S.

- NIMRC advances best practices, delivers expert consulting services, and disseminates state-of-field knowledge in medical respite care.

- Launched, on July 15, 2020, to respond to and address the growth and expansion of medical respite/recuperative care.

www.nimrc.org

National Harm Reduction Coalition

- Creates spaces for dialogue and action that help heal the harms caused by racialized drug policies.

- Our work is to uplift the voices and experiences of people who use drugs and bring harm reduction strategies to scale.

- Work with communities to create, sustain, and expand evidence-based harm reduction programs and policies.

www.harmreduction.org

National Street Medicine Institute

- Street Medicine Institute (SMI) facilitates and enhances the direct provision of health care to the unsheltered homeless where they live.

- Provides communities and clinicians with expert training, guidance, and support to develop and grow their own Street Medicine programs.

- Enables professionals and other individuals interested in the Street Medicine movement to come together to provide peer support, share best practices, seek advice and learn about key concepts necessary for a successful Street Medicine program.

www.streetmedicine.org

National Alliance to End Homelessness

- A nonpartisan organization committed to preventing and ending homelessness in the United States.

- Provides fact sheets, data, resources, and training on best practices for ending homelessness.

https://endhomelessness.org/

CSH and Pathways to Housing

- CSH resources help communities create and model cost-effective supportive housing to address many challenges, including homelessness, unnecessary institutionalizations, mental health needs, substance use recovery, crime, family separations, and poverty.

- Pathways trains direct service organizations, conducts research projects, and influences policy related to Housing First.

- Both guide the implementation of Housing First – ensuring access to housing without meeting specific qualifications.

https://www.csh.org/

https://www.pathwayshousingfirst.org/

I hope you find these resources helpful. Thanks for your time today.

Questions and Answers

In what setting do you work?

My experience has primarily been within health centers for the homeless. I also worked in a medical respite program in a shelter.

How are OT services paid?

This is a huge barrier for OTs to work in some of these spaces as there are limited resources. Working in a health center, there is potential for reimbursement, but because people experiencing homelessness are less likely to be covered by health insurance, a lot of programs operate off federal funding to be able to provide services despite insurance status. You may need to investigate your community to see what resources and funding are available.

If someone has a substance abuse problem, particularly illegal drug use, how do you guide their care and address that? Any tips for initial encounters?

This could be another topic, but the first thing is to be welcoming of the person with an understanding that you do not have all of the knowledge behind the substance use. This could be trauma, pain, or other things happening with the person. Is this a safe encounter? If a person comes to my session inebriated or under the influence, I might get them a cup of coffee or something to eat. I also want to make sure they get home safely. I really cannot do skilled OT services because there is not much to gain. However, they are always welcome to come back and try again. I may need to schedule their appointments in the morning because they can come first thing, and they will not be affected by using substances later in the day. It takes a lot of flexibility and experience.

References

Abbs, E., Brown, R., Guzman, D., Kaplan, L., & Kushel, M. (2020). Risk factors for falls in older adults experiencing homelessness: Results from the HOPE HOME cohort study. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 35(6), 1813-1820. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-05637-0

American Occupational Therapy Association. (2020). Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process (4th ed.). American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74(Suppl. 2), 7412410010. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2020.74S2001

Allen, M. E., Call, K. T., Beebe, T. J., McAlpine, D. D., & Johnson, P. J. (2017). Barriers to care and healthcare utilization among the publicly insured. Med Care, 55, 207-214.

American Occupational Therapy Association. (2019). Cognition, cognitive rehabilitation, and occupational performance. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 73(Supplement 2), 7312410010. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2019.73S201

Aubry, T., Tsemberis, S., Adair, C. E., Veldhuizen, S., Streiner, D., Laitmer, E., … Goering, P. (2015). One-year outcomes of a randomized controlled trial of Housing First with ACT in five Canadian cities. Psychiatric Services, 66, 463-469.

Ayano, G., Solomon, M., Tsegay, L., Yohannes, K., & Abraha, M. (2020). A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder among homeless people. Psychiatric Quarterly, 91, 949-963.

Baggett, T. P., O'Connell, J. J., Singer, D. E., & Rigotti, N. A. (2010). The unmet health care needs of homeless adults: A national study. American Journal of Public Health, 100(7), 1326-1333. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2009.180109

Bonin, E., Brehove, T., Carlson, C., Downing, M., Hoeft, J., Kalinowski, A., … Post, P. (2010). Adapting your practice: General recommendations for the care of homeless patients. Nashville, TN: Health Care for the Homeless Clinicians' Network, National Health Care for the Homeless Council, Inc.

Brown, R. T., Hemati, K., Riley, E. D., Lee, C. T., Ponath, C., Tieu, L., Guzman, D., & Kushel, M. B. (2017). Geriatric conditions in a population-based sample of older homeless adults. The Gerontologist, 57(4), 757-766. https://www.doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnw011

Cimino, T., Steinman, M. A., Mitchell, S. L., Miao, Y., Bharel, M., Barnhart, C. E., & Brown, R. T. (2015).The course of functional impairment in older homeless adults. JAMA Internal Medicine, 175(7), 1237-1239. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.1562

Centers for Disease Control. (2020). About social determinants of health. https://www.cdc.gov/socialdeterminants/about.html

Cocozza Martins, D. (2008). Experiences of homeless people in the health care delivery system: A descriptive phenomenological study. Public Health Nursing, 25, 420–430.

Fazel, S., Geddes, J. R., & Kushel, M. (2014). The health of homeless people in high-income countries: Descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations. Lancet, 384(9953), 1529-1540. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61132-6

Gibson, R. W., D'Amico, M., Jaffe, L., & Arbesman, M. (2011). Occupational therapy interventions for recovery in the areas of community integration and normative life roles for adults with serious mental illness: A systematic review. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 65, 247-256. doi:10.5014/ajot.2011.001297

Gonzalez, A., & Tyminski, Q. (2020). Sleep deprivation in an American homeless population. Sleep Health, 6(4), 489–494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2020.01.002

Helfrich, C. A., & Fogg, L. (2007). Outcomes of a life skills intervention for homeless adults with mental illness. Journal of Primary Prevention, 28, 313–326. doi: 10.1007/s10935-007-0103-y

Helfrich, C. A., & Synovec, C. E. (2019). Homeless and women’s shelters. In C. Brown, V. C. Stoffel, & J. P. Muñoz (Eds.), Occupational therapy in

mental health (pp. 672–690).

Ikiugu, M. N., Nissen, R. M., Bellar, C., Maassen, A., & Van Peursem, K. (2017). Clinical effectiveness of occupational therapy in mental health: A meta-analysis. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 71, 7105100020p1-7105100020p10. doi:10.5014/ajot.2017.024588

Illman, S. C., Spence, S., O’Campo, P., & Kirsh, B. (2013). Exploring the occupations of homeless adults living with mental illnesses in Toronto. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 80(4), 215–223.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0008417413506555

Kaplan-Lewis, E., & Percac-Lima, S. (2012). No-show to primary care appointments: Why patients do not come. Journal of Primary Care and Community Health, 4, 251-255.

LeBrun- Harris, L. A., Baggett, T. P., Jenkins, D. M., Sripipatana, A., Sharma, R., Hayashi, A. S., … Ngo-Metzger, Q. (2013). Health status and health care experience among homeless patients in federally supported health centers: Findings from the 2009 patient survey. Health Services Research, 48(3), 992-1017. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12009

Lynch, K. S., & Lachman, M. E. (2020). The effects of lifetime trauma exposure on cognitive functioning in midlife. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 33(5), 773-782. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22522

Marshall, C. A., Cooke, A., Gewurtz, R., Barbic, S., Roy, L., Ross, C., Becker, A., Lysaght, R., & Kirsh, B. (2021). Bridging the transition from homelessness: Developing an occupational therapy framework. Scandinavian journal of occupational therapy, 1–17. Advance online publication.

Marshall, C., Lysaught, R., & Krupa, T. (2017). The experience of occupational engagement of chronically homeless persons in a mid-sized urban context. Journal of Occupational Science, 24(2), 165–180.

Magwood, O., Leki, V. Y., Kpade, V., Saad, A., Alkhateeb, Q., Gebremeskel, A., Rehman, A., Hannigan, T., Pinto, N., Sun, A. H., Kendall, C., Kozloff, N., Tweed, E. J., Ponka, D., & Pottie, K. (2019). Common trust and personal safety issues: A systematic review on the acceptability of health and social interventions for persons with lived experience of homelessness. PLoS ONE, 14(12): e0226306. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0226306

Muñoz, J. P., Garcia, T., Lisak, J., & Reichenbach, D. (2006). Assessing the occupational performance priorities of people who are homeless. Occupational Therapy in Health Care, 20(3-4), 135–148. https://doi.org/10.1300/J003v20n03_09

National Alliance to End Homelessness. (n.d.) The five keys to effective emergency shelter. https://endhomelessness.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/keys-to-emergency-shelter-naeh.png

National Alliance to End Homelessness. (n. d.) Keys to emergency shelter. https://endhomelessness.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/keys-to-emergency-shelter-naeh.png

National Harm Reduction Coalition. (2021). Principles. https://harmreduction.org/about-us/principles-of-harm-reduction/

National Health Care for the Homeless Council. (2021). Where does homelessness happen? https://nhchc.org/where-does-homelessness-happen/

National Health Care for the Homeless Council. (2019). Homelessness and health: What’s the connection? https://nhchc.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/homelessness-and-health.pdf

National Institute for Medical Respite Care [NIMRC]. (2021). Clinical guidelines for medical respite/recuperative care: Activities of daily living. https://nimrc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Clinical-Guidelines-in-Medical-Respite_-ADL_Final.pdf

National Institute for Medical Respite Care. (2021). State of medical respite/recuperative care. https://nimrc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/State-of-Medical-Respite_Recup-Care-01.2021.pdf

National Institute for Medical Respite Care. (2019). Defining characteristics of medical respite/recuperative care. https://nimrc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Defining-Characteristics-of-MRC2.pdf

Nickasch, B. & Marnocha, S. K. (2009). Healthcare experiences of the homeless. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 21, 39–46.

Powell, J. M., Rich, T. J., & Wise, E. K. (2016). Effectiveness of occupation- and activity-based interventions to improve everyday activities and social participation for people with traumatic brain injury: A systematic review. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 70, 7003180040p1-9.

Rabiner, M., & Weiner, A. (2012). Health care for homeless and unstably housed: Overcoming barriers. Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine, 79, 586-592. doi:10.1002/msj.21339

Radomski, M. V., Anheluk, M., Bartzen, M. P., & Zola, J. (2016). Effectiveness of interventions to address cognitive impairments and improve occupational performance after traumatic brain injury: A systematic review. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 70, 7003180050p1-7003180050p9. doi:10.5014/ajot.2016.020776

Salsi, S., Awadallah, Y., Leclair, A. B., Breault, M. L., Duong, D. T., & Roy, L. (2017). Occupational needs and priorities of women experiencing homelessness. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 84, 229–241. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008417417719725

Siersbaek, R., Ford, J. A., Burke, S., Cheallaigh, C. N., & Thomas, S. (2021). Contexts and mechanisms that promote access to healthcare for populations experiencing homelessness: a realist review. BMJ Open, 11, e043091. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043091

Simpson, E. K., Conniff, B. G., Faber, B. N., & Semmelhack, E. K. (2018). Daily occupations, routines, and social participation of homeless young people. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 34(3), 203-227, https://doi.org/10.1080/0164212X.2017.1421491

Street Medicine Institute. (2021). About us. https://www.streetmedicine.org/about-us-article

Stubbs, J.L., Thornton, A.E., Sevick, J.M., Silverberg, N.D., Barr, A.M., Honer, W.G., & Panenka, W.J. (2019). Traumatic brain injury in homeless and marginally housed individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Public Health, 5(1), e19-e32. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30188-4

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2021). Homelessness resources: Housing and shelter. https://www.samhsa.gov/homelessness-programs-resources/hpr-resources/housing-shelter

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2014). SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. https://store.samhsa.gov/product/SAMHSA-s-Concept-of-Trauma-and-Guidance-for-a-Trauma-Informed-Approach/SMA14-4884

Synovec, C. E., LeFlore, A., & Robins, N. (2021). Nowhere to discharge: Occupational therapy’s emergent role in medical respite programs for people experiencing homelessness. OT Practice, 26(3), 22-25.

Synovec, C. E., Merryman, M., & Brusca, J. (2020). Occupational therapy in integrated primary care: Addressing the needs of individuals experiencing homelessness. The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy, 8(4), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.15453/2168-6408.1699 Tamberrino, L. (2021). The role of occupational therapy in street medicine. Capstone Presentation, Boston University.

Thomas, Y., Gray, M. A., & McGinty, S. (2017). The occupational wellbeing of people experiencing homelessness. Journal of Occupational Science,

24(2), 181–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2017.1301828

Tyminski, Q., & Gonzalez, A. (2020). The importance of health management and maintenance occupations while homeless: A case study. Work, 65(2), 297–301. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-203081

Van Oss, T., Duch, F., Frank, S., & Laganella, G. (2020). Identifying occupation-based needs and services for individuals experiencing homelessness using interviews and photovoice. Work, 65(2), 247–255. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-203076