Jean: Thank you very much and good morning. It's a pleasure to be with all of you this morning and share with you current research and my own experiences in school-based practice with students who struggle with literacy issues. The agenda for today's seminar is as follows:

- Our National Focus on Literacy – What and Why?

- How Literacy Develops

- Including Literacy in OT and PT Evaluation

- OT and PT Interventions to Support Literacy

National Focus on Literacy

Because the context of our practice is within schools, where reading and writing are given significant focus, that will be our focus today. To begin, let's look at literacy from a national perspective. The definition of literacy is more inclusive than you might expect (UNESCO, 2004):

Literacy is the ability to read, write, listen, speak clearly and think critically using print and digital materials across all disciplines.

Literacy involves a continuum of learning, enabling individuals to achieve their goals, develop their knowledge and potential, and participate fully in their community and wider society.

The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) publishes outcome data based on student performance on the National Assessment of Educational Performance (NAEP). The NAEP is a group of academic assessments administered periodically across the country to determine what American students know and can do. The NAEP is the largest nationally representative and continuing assessment in the United States. The reading assessment is given to fourth and eighth graders every two years. The writing assessment is given periodically to eighth and 12th graders. The NAEP is sometimes referred to as the nation's report card.

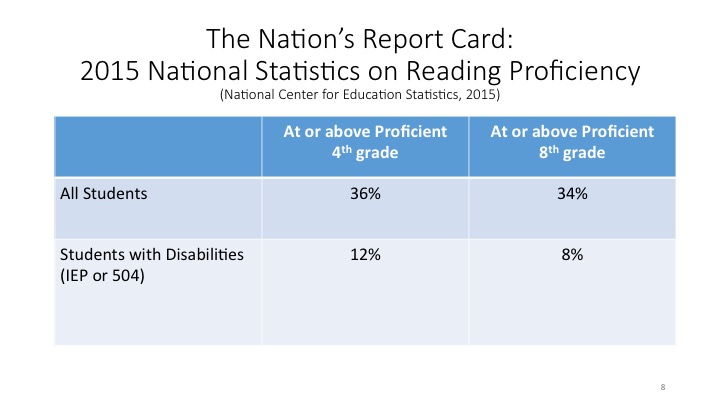

In 2015, the NCES compared reading proficiency results at fourth and eighth-grade levels (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. 2015 National reading proficiency stats.

In fourth grade, 36% of all students (including those with disabilities) achieved grade level proficiency on the NAEP. Only 12% of students with disabilities achieved grade-level proficiency. Among eighth-graders, 34% achieved grade level proficiency compared to only 8% of students with disabilities. Stated another way, 64% of all fourth graders and 66% of all eighth graders included in the 2015 data were reading below grade level. For children with disabilities, 88% of fourth-graders and 92% of eighth-graders were reading below grade level.

According to NAEP trend data, between the years 1998 and 2011, there was a reading proficiency increase of only four points at the fourth-grade level and only two points at the eighth-grade level for students with disabilities. This is despite the national effort to improve reading scores among all students.

Writing

According to the most recent NAEP assessment data, 25% of all students, with and without disabilities, in eighth and 12th grades scored at or above the proficient level in writing (NCES, 2012). This abysmal writing outcome underscores the seriousness of the writing challenge for all of the nation's students. For students ages 9-14 with learning disabilities, writing is considered their most common problem, more so even than reading (Cobb-Morocco, Dalton & Tivnan, 1992). Approximately 80% of children with learning disabilities struggle with written language (Morris et al., 2009).

The Writing-Reading Connection

We have observed a relationship between reading and writing for those of us who have worked in schools with young learners. Let's take a look at what recent studies have found about a reading-writing connection. In 2011, Graham and Hebert published a meta-analysis study seeking to identify whether and how writing impacts children's reading abilities. As you may know, a meta-analysis looks across a topic or topics in the literature seeking commonalities among the findings of various research studies. In their meta-analysis, these authors looked at 95 studies of students in grades one and two. Their findings include the following:

- Writing about material read enhances reading comprehension

- Writing about reading has a positive impact on the comprehension of weaker readers and writers

- Writing instruction enhances student's reading

- Increasing writing improves reading comprehension

- More writing instruction produce greater reading gains than less writing instruction

In another study published in 2012, Karin James looked at brain images to identify a reading-writing connection. She found that children who drew a letter freehand from a model showed increased brain activities in areas of the brain that activate during reading and writing; what she characterizes as "a recognition by mental stimulation of the brain." This was not the case for children who typed or traced the letter but only for children who drew a letter freehand.

Many of you may be aware of the work of Virginia Beringer. Her name has become one that's frequently cited by instructional personnel and therapists looking to find insights into how to help with reading and writing. Her body of research, published over a period of years beginning in 1990, has yielded conclusions that make a case for handwriting, including cursive writing, to improve reading and writing skills. In her studies, children produced more words more quickly and expressed more ideas when composing by hand versus using a keyboard. When asked to develop ideas for a composition, children with better handwriting exhibited greater neural activations in areas associated with working memory. They increased overall activation in reading and writing networks. Finally, Berninger found that cursive writing may help facilitate motor control of letter formation and prevent the reversal and inversion of letters. Many of us have seen that in our practice, particularly with kids who are dyspraxic.

In an interesting study of college students in 2014, Mueller and Oppenheimer found that students learn better when they take notes by hand than when they type on a computer. Now, this study was based on older students, but it is informative nonetheless. This finding suggests that writing by hand allows the student to process a lecture's contents and reframe it, a process of reflection and manipulation that appears to lead to better understanding and encoding. As Graham and Hebert noted in their 2011 conclusions, it is ironic that "despite the importance of writing to reading, learning, communicating self-expression, self-exploration, and future employment, students at school write infrequently, and little time is devoted to writing instruction beyond the primary grades."

Impact of Assistive Technology

Given the evidence for the importance of handwriting to both writing and reading, what impact does assistive technology have on literacy efforts for children with disabilities? In 2012, Dunst and Colleagues conducted their own meta-analysis. They reviewed a total of 36 studies involving almost 700 children with disabilities or delays. They looked at both speech generative devices and various computer software devices. In their results, looking across these studies, they found that both speech generative devices and various software devices effectively promoted communication and literacy-related behavior, regardless of disability or delay. While handwriting might be the most effective way to imprint reading and writing, there is also the benefit to using speech generative devices and various computer software devices.

Human Development and Literacy

After reviewing the evidence, it is clear that we have a significant problem across our country with reading and writing and that the problem is particularly consequential for children with disabilities. But why should OTs and PTs involve themselves in this issue? According to Clark and Bainter in 2013, research indicates that poor reading skills affect students' academic, emotional, and social well-being. Third-grade students who did not read at grade level are four times more likely to drop out of school later in life than students who are proficient readers. Teenagers with reading problems are more likely to experience social, emotional problems, use drugs, think about harming themselves or avoid adult responsibilities. There are social and emotional consequences, as well as academic consequences, to poor reading skills.

You may wonder how the US Department of Education is addressing literacy issues for students with disabilities. To determine state compliance with IDEA (Individuals with Disabilities Education Act), the United States Department of Education requires states to set state targets, develop plans for achieving the targeted goals, and report annually on the performance of students with disabilities across 16 specific indicators. Each of the states in US territories has to report on these particular 16 indicators. Because reading is seen as foundational to the acquisition of learning across content areas, indicator three of the 16 indicators specifically requires states to report on the percentage of children with disabilities included in testing on the NAEP in 4th and 8th grades scoring at basic or above on the NAEP.

In addition to the required 16 indicators, over the past two years, all states have been required to adopt the 17th indicator, an overarching indicator for their state that they believe is the best measure of progress for the children who live there. Interestingly, over 50% of states in US territories chose an indicator specifying an increase in reading, English language arts, or specifically, literacy. This common sense of literacy's foundational importance should not come as a surprise, given the data that we have reviewed. This indicator is a State-Identified Measurable Result for Children with disabilities, sometimes called the SIMR. You may hear that acronym used in your state.

OT/PT Involvement

As school-based practitioners, we can and should provide meaningful support to improve student literacy in our schools. In our training to become therapists, most of us did not encounter coursework on literacy development. Let's review the fundamentals of literacy development to heighten your awareness of how to provide meaningful support to literacy issues. We'll begin by looking in a bit more detail at what students need to be successful.

These are the aspects of human development that have been identified as important to the acquisition and application of literacy skills: language, attention, memory, cognitive function, executive function, sensory processing, and social-emotional development.

These are the skills and abilities that are important in the specific areas of cognitive and executive functions: attending, initiating, continuing, and terminating tasks or activities, memory, working memory, emotional regulation, plan formation (and also behaving your way towards those goals and that plan), activity modification, problem-solving, self-monitoring, and correction.

In the area of social communication, another aspect of literacy, the student must develop the following abilities: to ask questions, to use appropriate volume and tone in interactions, to use polite terms, develop the ability to initiate, maintain, and appropriately end conversations in their social communication, the ability to stay on topic, understanding the meaning of words, and be able to make requests appropriately.

Important social interaction skills that must be developed for successful development of literacy include: being able to approach/initiate social interaction, being able to conclude or disengage from interactions with others appropriately, producing speech, self-regulating, asking questions, replying appropriately, knowing how to disagree appropriately in social interactions, knowing how to express thanks, and how to take turns with others.

Stages of Literacy Development

Dunst and Colleagues identified the following three stages in literacy skills: preliteracy, emergent literacy, and early literacy. Preliteracy occurs between birth and 15 months of age approximately. The development includes joint attention, non-verbal communication, vocalization, picture recognition, and the ability to listen. As the child gets a little older, between one year and 30 months, they move into the stage of emergent literacy. They begin to use language and vocabulary, utter their first words and requests, and recognize print and symbols. Then in the early literacy stages, between 30 and 60 months, we see an understanding of written and heard words, an understanding of the rules of written language, letter and word recognition, and sometimes invented spelling in their writing.

Robyak and Colleagues broke down the knowledge and skills that must be acquired for both print-related and speech-related literacy. These are skill sets that also predict literacy acumen later on in life.

Print-related literacy skill sets include:

- Alphabet knowledge: the knowledge of letters and the reality that letters are translated to sounds

- Print awareness: recognizing rules and properties of written language

- Written language awareness: differentiating letters and words, representing ideas in written form

- Text comprehension, reading, and extracting meaning from the text

Speech-related literacy skills include:

- Listening comprehension: the ability to process and understand the meaning of spoken words (includes decoding)

- Phonological awareness: recognizing, using, and discriminating sounds

- Oral language: using words as a tool to communicate

The development of automaticity is a critical component of reading. Automaticity becomes possible through overlearning of letter and spelling patterns. As therapists, we would think of this as a great deal of repetition, a great deal of practice across multiple school content areas. The development of automaticity leads to fluency, the ability to quickly and accurately process print with expression. Word recognition accounts for much of the reading ability variance; poor readers demonstrate poor letter and word attack skills (Kucer, 2009).

In 1988, Temple and colleagues outlined a typical pattern of early writing stages and sequence. Even though their work was published 30 years ago now, it is still considered to be foundational. Typical early writing begins with a drawing, progressing to a stage of letter-like scribbles to represent ideas. Then you should begin to see letter-strings to represent words or a sentence, eventually copying letters and whole words, and finally generating letters to represent sounds in words.

In 2015, Konnikova published research from a three-year study conducted at the University of California in San Francisco. They were trying to pinpoint a neurological component of development that is predictive in nature. Konnikova looked at children across the socioeconomic spectrum, studying their environmental variables and brain networks. She found that taking into account all of the explanatory factors that have been linked to reading difficulty in the past (e.g., genetic risk environmental factors, pre-literate language ability, and overall cognitive capacity), only one thing consistently predicted how well a child would learn to read: the growth of white matter in the left temporoparietal region of the brain between kindergarten and third grade. Fascinatingly, in her study, the amount of white matter that a child arrived with in kindergarten didn't matter. What mattered was the input the child received between kindergarten and third grade.

Including Literacy in OT and PT Evaluation

When we are asked as therapists to evaluate a student at school with literacy issues, what are we bringing to the table that's not already present among the collaborative team members? You may use this rationale for including literacy in your data collection. For children K-12, reading and writing are critical activities for successful learning and participation. Active engagement (e.g.., participation in reading, writing, listening, thinking, and speaking) promotes skill-building. If we think of ourselves as OTs and PTs as operating off of a basis from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Classification of Functions (ICF), what we are trying to do is help students achieve a higher level of engagement and participation in the activities at school. Identification of data relevant to our disciplines is key to meaningful OT and PT support of literacy.

Consider for a few minutes OT and PT frames of reference. Many of the student evaluations that we conduct at school involve a lot of detective work. As OTs and PTs, we contribute insight that is not going to be ascertained from other data sources among team members in many cases. We don't see things in the same way as teachers. Our frames of reference are not the same as speech-language pathologists. We don't look at things in the same way as psychologists or counselors. Once a problem is identified, we need to employ the varied frames of reference from our training and observations, and interviews as part of the evaluation. For example, a particular student exhibits difficulty holding her head up. If a child is unable to hold her head up, is it a biomechanical issue? Is it a neurodevelopmental issue? Is there a motor learning issue? Or is there something going on from a sensory perspective? Is there something socially impacting this child's interest and willingness to hold her head up? As therapists, we are not in a position to critique the instructional program or teaching practices, but there may be many factors within the person, the task or activity design, or the environment that may be negatively affecting the student's ability to participate in fully and benefit from the instruction.

I'll briefly share an anecdote about a child I observed in a third-grade classroom. The teacher could not figure out why this child was always 10 to 15 minutes late in completing his work. I went into the classroom, sat in the back, and observed the end of a reading period where the teacher was reading to the students. Then she gave them verbal directions, with about four or five steps. The student in question was able to go back to his work table with everybody else. But as everyone else was getting started, he was watching them. He watched them until he apparently had a good handle on what he was expected to do. As such, he was later getting started than everyone else, and he kept having to check what everyone else was doing to see what the next part of the assignment was. As it turns out, this young man could not follow auditory directions in sequence when the list of steps was longer than one or two. The problem was not that he didn't want to do the work or a slow worker. The problem was he couldn't get started until he had a full understanding of what was expected of him. This was easily remedied, using an index card with written directions that he could keep on his desk to start along with everyone else. That's a simple example of something that didn't require a great deal of intervention on OT. It just required good observations and a quick interview with the teacher to see what was happening. That is our purview as related service personnel, occupational therapists, and physical therapists supporting school activities.

Data Collection Process

Throughout the data collection process, to be evidence-based, our observations should take place during the time of day the problems manifest and the exact environments where the problems occur. A child may have consistent difficulties throughout the day, from one class to another, from one teacher to another. They may have problems that manifest with one specific teacher during the day, and they do not have issues with the other teachers. Wherever and whenever the problem is occurring, we need to conduct our observations and interviews during the time of day and in the place where the problems occur. Otherwise, as Dr. Russell Barkley has stated, we are wasting our time because we're not getting relevant contextual data.

Step 1: Data Collection through Interview and Observation. In the first stage of data collection, through our interviews with school personnel and parents and our observations of the student, these are the details we need to be documenting:

- Stage of literacy development? If the student is in the pre-emergent stage, there will be different expectations on the child than if he has been through all of those particular developmental stages.

- Communication skills (any issues with receptive and/or expressive language)?

- Issues with language, attention, memory, cognition, executive function, sensory processing, social-emotional skills (any testing needed)? Level of engagement/participation? Do they attend, or are they off in their own world somewhere or withdrawn from the class?

- Social skills (peers and adults)? Are they able to work together with others in team-based activities?

- Behavioral issues (coping skills, self-regulation, etc.)? Is their frustration tolerance low?

- Issues with seating and positioning that may impact access?

- Issues with language, attention, memory, cognition, executive function, sensory processing, social-emotional skills (any testing needed)?

- Level of prompting/cueing required?

- Issues with tone, balance, strength, and/or endurance impacting participation and performance? For example, does the child start actively engaged in the morning, but after lunch, there's a drop off in their ability to attend and engage and participate in activities? That might be a clue to what's happening with the child regarding their tolerance and fatigue throughout the day.

- Issues with accessing materials (including assistive tech)? Are there environmental barriers?

- Issues with following directions, attention to task, following through to completion?

- Contextual/environmental factors influencing participation and performance (instruction, structure, sensory features, etc.)? For example, are there things happening during instruction? Is there something about the structure, or lack thereof, in the room that's interfering? Is there something about the room's sensory features that makes it difficult for the child to participate (e.g., unexpected noises, a bell schedule that's upsetting to the child, outbursts by someone else in the room)?

- Comparison of work samples among students in the same instructional arrangement for reading and/or writing. How does the sample of our child's material look in comparison to the others in the classroom?

- Are both reading and writing production problematic? Or does the student only have difficulty with one or the other?

- Teacher/parent/student perception of the problem(s)?

- Teacher/parent/student perceptions of barriers/facilitators?

- Services and supports (including accommodations and modifications) already in place (including assistive technology)?

- Student preferences for positioning, equipment, subject matter, environment, etc. For example, a teacher has difficulty engaging a young student on the autism spectrum in reading and writing activities. If it is known that this student loves turtles, perhaps we could begin to initiate reading and writing by engaging the child in a book about turtles and encouraging him to write a story about turtles. Provide some sort of direction to the teacher on how to take advantage of a child's preferences.

Step 2: Select Assessment Tools to Assist with Data Collection. If more information is needed, choose assessment tools that will provide quantitative data. I do want to note that although some state or local education agencies may request, may require, or may prefer standardized testing; there is no federal requirement that standardized tests be administered. Do not feel compelled to use them, although they may add relevant and quantifiable data to your data collection.

One assessment to consider is the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM). This is a simple interview test that identifies how student feels about their own communication skills, reading and writing abilities. This measure supports student goal-setting. First, a student is asked what he thinks about his communication, reading, writing, or any topic of concern. Then, he's asked to rank how big a problem he thinks this is and set some goals (Law et al., 2005).

Another assessment tool that might be helpful is the Child Occupational Self-Assessment 2.2 (COSA). This measure also captures the children's perceptions regarding their own sense of occupational competence and the importance of everyday activities (Kramer et al., 2014). Its purpose is similar to the COPM.

A new assessment tool, developed by Lenin Grajo in 2015, is the Inventory of Reading Occupations. Research articles on this inventory can be found in both the American Journal of Occupational Therapy (AJOT) and the Journal of Occupational Therapy Schools and Early Intervention (JOTSEI).

Finally, the DeCoste Writing Profile can give you data that might be helpful (Decoste, 2015). This is a quick assessment of written expression by hand or using assistive technology and compares the two in terms of speed and accuracy.

Step 3: Analyzing and Synthesizing Data. We need to apply our clinical reasoning skills to analyze and synthesize our data, looking at all sources. We want to begin with identifying the barriers that exist within the student themselves. From the data collected, what have we discovered? Do they have any biomechanical, developmental, cognitive, sensory processing, executive function, or social, emotional barriers, including avoidance, dislike, decreased initiation and participation, low frustration tolerance? What sort of facilitators is present, biomechanically, cognitively, in terms of executive function skills, in terms of a child's enjoyment of computers, their desire to please, their interest in a topic or content, their intrinsic drive to succeed, the attention of a particular teacher? What sort of things exist, either in the person or within the environment, that may facilitate learning and participation? Make recommendations to the IEP team based on your data and your analysis for strategies to consider and for services if you believe OT and/or PT services are needed. If services are needed, collaborate with the IEP team regarding priorities for the next 12 months and identify which goals and objectives need OT and PT support in the area of literacy.

OT and PT Interventions to Support Literacy

Next, I will provide suggestions for interventions and strategies to support literacy issues from my own personal experience and the OTs and PTs' experience with whom I've had the pleasure of working over the past 26 years.

Interventions to Promote Access and Reduce Barriers.

- Accommodating a range of motion and/or volitional movement limitations

- Development of physical stamina and balance, if these are interfering with the child's ability to make progress in literacy areas

- Addressing biomechanical and ergonomic needs

- Resolving seating and positioning issues (equipment needed?): How many times do we see in a classroom that the seating and positioning is a big factor in the child's ability to attend and sustain attention over time?

- Accommodating handling/object manipulation challenges: If handwriting is not possible, or not possible now, perhaps we want to continue working on handwriting, but also integrate into the child's day assistive technology options for being able to express and document what they're learning.

- Reducing sensory barriers and meeting sensory needs: This is an area where OTs are typically looked for assistance. These do not need to be $10,000 solutions if something straightforward will take care of it. For example, perhaps it's as simple as dimming the lights as children come in from the playground to help them calm down and get ready to learn. Perhaps it is simple as a set of headphones to dull the bells' noise between the change of classrooms and class schedules.

- Employing task analysis, material or technological adaptations: with paper, some software will help with word prediction, for example.

- Providing environmental accommodations and modifications: Change where they sit in the classroom, for example. Declutter all of the walls so there's not as much visual stimulation.

- Participating in the identification of assistive tech solutions

Interventions to Improve Student Engagement. I want to reinforce the importance of identifying the motivating factors for the student, and their sensory preferences, so the engagement and participation are easier and more interesting for the student. Embed the motivating factors and preferred sensory inputs in school activities and assignments to increase participation. If it's the turtle that's most important to the child, maybe there can be a secret turtle in each of the assignments that the child is given, and he has to find it among the things he's being asked to do. Support activity scaffolding with prompts, cues, modeling, and feedback to customize the activity and our approach to the activity for the individual student, always striving to move forward with dropping prompts and cues as we can. Promote coping strategies for anxiety or avoidance behaviors that impede engagement. Coping is a learned skill for many students; some come to it naturally, but many have to be taught activities that can help them cope or strategies that can help them cope with things going on at school that are difficult for them. Support student development of coping strategies, self-regulation to minimize the impact of frustration, exasperation and increase sustained attention. Various programs can help with that, such as "How Does Your Engine Run?" (Williams and Shellenberger, 1996).

Promote Performance-Based Skills and Readiness. Provide strategies for enhancing reading success, including alphabet knowledge, phonological awareness, decoding, and visual tracking. You need to become familiar with those terms, particularly those that are more likely to be used by instructional personnel, such as alphabet knowledge and phonological awareness. We also need to foster fine motor skills and handwriting within the school and school activities and routines. Foster the development of keyboarding and mouse skills; those are life skills for all children at school in this day and age. Provide strategies to enhance the computer interface skills, including the use of assistive technologies in curriculum activities. This may require working both with the student directly and working with the teacher in an indirect approach service intervention so that the teachers know when to employ which of the assistive technologies are available to the student. Promote social skill development for increasing social communication and social engagement. Help the teacher set up classroom situations where literacy activities include turn-taking, including listening and reflecting on what others say.

Summary and Review of Resources

In summary, occupational therapists and physical therapists can make unique contributions to literacy efforts as members of the collaborative team. I hope that as a result of your attendance, you'll feel more confident about your role in supporting literacy at school.

I want to call your attention also to the list of references I have provided. All of the slides that have studies by various authors in this presentation this morning are referenced in your reference list, and you can find them at Google Scholar or other OT and PT resources. In your handouts, I've provided today a resource list where you can find more information.

One additional resource that you may find easily accessible and valuable comes from a source outside of OT and PT typical resources, from Science Daily. I don't know how many of you subscribe to ScienceDaily.com, but the topic areas they report on are literacy. They showcase the latest research published on issues impacting literacy. Recent examples of relevant articles you can access through Science Daily include an article with evidence that visual attention is a good predictor of babies' first words. There's also an article posted currently that reveals the likelihood that children from poor neighborhoods are missing out on language learning, both at home and in their daycares and preschools. This one is exciting because it informs some of the issues children from poor neighborhoods have when they come to school trying to grasp the complexity of language and its sophistication. This particular study found that in homes where survival is perhaps the top priority, parents and other adults in the home are not speaking in a complex language; they tend to use simpler, shorter sentences with young children. Also, the daycares and preschools that the children can attend in those poor neighborhoods do that. As a result, when they come to school, they haven't had as rich of a language background as students who are not from poor neighborhoods. The third article of interest finds a link between a child's sedentary life and poor academic performance. There's quite a body of research on physical activity and its connection to improving academic performance, but this one talks about less activity in terms of children's sedentary lifestyles. This would be an excellent article to inform perhaps an initiative at school for getting kids more active across the board.

Questions and Answers

What is the age range for the assessments?

The Canadian Occupational Performance Measure is appropriate for children beginning at age eight; very young children cannot participate in the COPM. I'm afraid that I cannot call to mind the COSA's age ranges. I would assume they would have to be old enough to understand that you want them to interact and answer questions. The Inventory of Reading Occupations is appropriate to school-age children, as is the DeCoste Writing Profile.

As an assessment tool, does the COSA help understand the student's perspective regarding their literacy challenges, or is that just with the COPM?

Both the COSA and the COPM will allow you to see the child's understanding and perspective regarding their literacy challenges. You'll find out how important reading and writing are to the child and exactly what is important to the child.

Is hand-over-hand beneficial as an intervention?

I think the research is mixed on that. Perhaps hand-over-hand can be beneficial to begin an imprinting process, but there also must be some cognitive connection. I don't see any purpose, and I don't see in the literature any purpose in continuing hand-over-hand year after year if there does not appear to be any emergence of some volitional activity on the part of the child over time. If you go back to the particular steps in writing, for example, when a child should begin to emerge in the first steps for drawing, you could begin some of that with some hand-over-hand and prompt some of that kind of activity by the child. If over multiple opportunities with multiple inputs from hand-over-hand, you don't see anything connecting in the child, you don't see any volition; you don't see the child initiating that on their own at all over time, try other kinds of accommodations or other kinds of activities to engage the child. As the child grows a little bit older, you could try hand-over-hand again at that time.

Is tracing words effective to help with the writing literacy connection?

I did not see in the literature review that I did to prepare for this topic any evidence that substantiated repeated tracing over time as being a particularly effective way of stimulating the initiation of writing. I know that tracing is often a strategy used by therapists to try to help children understand and make that connection between reading and writing. However, much like hand over hand activity, if the child is not beginning to initiate on their own after repeated efforts using tracing, you might go on and try other activities or drop back because my guess is the child is not ready and is not yet cognitively connecting the tracing to your desire to have them initiate the beginning of letter formation. Again, I would try anything, but if you do not see the kind of outcomes you want from that strategy, I would drop back developmentally. I would initiate some other strategy to try to help them make the reading and writing connection.

Are high-frequency word memory games beneficial as an intervention?

Some new research was recently published by an OT on faculty at the University of Texas medical branch in Galveston. She uses gaming to see if it will be effective with kids on the autism spectrum. I would encourage you to search for research along those lines because she was having some success with that. I cannot tell you beyond students with autism if there is a positive impact, but I can tell you there is beginning research that looks at gaming to both engage and try to facilitate literacy gains.

Citation

Polichino, J (2017, May). OT and PT support for literacy in schools. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 3715. Retrieved from http://OccupationalTherapy.com.