Editor's Note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Return to Work after Cancer and the Role of Occupational Therapy, presented by Jantina Kroese-King, Occupational Therapist/Clinical Epidemiologist.

*Please also use the handout with this text course to supplement the material.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to identify the facts and the prognostic factors for returning to work after cancer.

- After this course, participants will be able to recognize the role of occupational therapy within this specific path of care.

- After this course, participants will be able to identify different ways to provide models and interventions.

Introduction/Agenda

0 - 5 | Introduction |

5 - 10 | Facts about return to work |

10 - 30 | Factors that influence return to work |

30 - 35 | Role of the occupational therapy practitioner |

35 - 45 | Steps to take |

45 - 55 | E-health |

55 - 60 | Take home message/Questions |

I'm so pleased to meet you all and to discuss this topic because it’s one I find both compelling and relevant—returning to work (RTW) after cancer. By the end of our time together, you’ll have a clearer understanding of the prognostic factors influencing return to work after cancer. I hope you’ll also gain a deeper appreciation for the role of occupational therapy within this unique care pathway.

Throughout this session, I’ll share some facts and insights on how various factors impact the ability to return to work and the key contributions occupational therapy practitioners (OTPs) can make, as well as explore different intervention models that support this transition. I’ll include specific examples and highlight strategies to promote a successful return to employment. We’ll also touch on using e-health in this context and, of course, leave time for questions and a take-home message. By the end, I hope to spark new ideas and offer practical steps that can be applied to support individuals as they navigate this critical phase of life after cancer.

AOTA: Cancer Rehabilitation with Adults

As we continue, I’d like to highlight a promising development that originated in the United States—a comprehensive product outlining important considerations for returning to work after cancer. I commend you for this achievement, as the guideline identifies key aspects that can be vital in supporting individuals in this journey.

If we look closely at the guidelines, it’s clear that the amount of solid research—especially high-quality, rigorous studies—remains somewhat moderate to limited. That said, it is starting to grow. When I did my thesis as part of my university work to become a clinical epidemiologist, I focused specifically on returning to work after breast cancer. Comparing the available research to what was accessible back then, there has been a significant shift, especially in quality and scope. I’ll share more details about that shortly, but there are still gaps despite the progress. And therein lies the challenge for us as OTPs.

Looking forward, I see opportunities for more intervention studies to include OTPs in a central role. We’re uniquely positioned to support individuals’ social participation; that’s one of our core strengths when discussing work. So yes, we do have a role to play here, and I believe the future will open even more doors for us to contribute meaningfully to this area of practice.

Research

Rehabilitation Interventions to Support RTW

If we look at research from 2021, there was a rehabilitation intervention study focused on supporting a return to work after cancer (Algeo et al., 2021). The good news is that nine studies could be analyzed, but unfortunately, that’s only a fraction of the 28 that were initially considered. This often happens in systematic reviews when you’re trying to gather findings from different researchers. It sounds straightforward—to group the outcomes and see the bigger picture—but it’s challenging because the interventions are rarely identical, and the outcomes measured vary widely.

For instance, it’s difficult to draw direct comparisons when studying return to work if the participant groups aren’t similar regarding cancer type, stage, or job role. That’s why, in this particular review, only nine studies met the criteria for a comprehensive analysis. Despite these limitations, the key finding stands out: multidisciplinary interventions produce better outcomes.

This tells us that when different professionals—whether a PT, an OTP, a vocational counselor, or a psychologist—come together and contribute their unique expertise, the chances of a successful return to work significantly improve. The synergy of combining these perspectives creates a high-value approach for patients. This reinforces the importance of collaborative efforts and highlights where our role as occupational therapy practitioners can make a meaningful impact.

Positive Effect of Spa Therapy

I want to mention an interesting study by Mourgues et al. from 2014. Although it’s a bit dated, it highlighted something noteworthy: engaging in activities like spa visits, gym sessions, using saunas, and general movement led to positive outcomes and even contributed to improvements in people’s ability to engage in their daily occupations. This approach is recommended in more recent guidelines, especially when looking at oncology rehabilitation from a broader perspective. It’s become clear that movement is beneficial—not just for physical recovery but also for overall well-being.

This is why asking your clients about their physical activity levels is important. And when I say movement, it doesn’t have to be intense exercise like running or going to the gym. It could be as simple as walking every other day or finding ways to keep active in a way that suits them. What matters is that we encourage them to move their bodies regularly. Often, when people are focused on returning to work, they might overlook the importance of staying physically active, but it’s essential for long-term recovery and health.

Multicenter RCT

Interesting research was done in the Netherlands in 2019 (Tamminga et al.), comparing education and work-related support to usual care. The results showed a significantly higher rate of return to work in the group receiving specialized support than the national statistics for a similar population. This tells us that when we provide specific, targeted interventions, we can positively impact the likelihood of a successful return to employment.

The study also looked closely at identifying which individuals might be at higher risk of struggling with this transition. Understanding who might need additional support is crucial for tailoring our interventions. For example, they found that people who had undergone a high amount of chemotherapy had a lower level of education or reported low workability and needed more time and support to return to work. Conversely, individuals with a higher education level tended to return to work more quickly.

This suggests that during our initial conversations with clients, listening carefully to clues about their education level, workability perception, and treatment history is helpful. If someone mentions, “I don’t feel capable of doing my job as I used to,” it’s a sign that they may need more support and a closer look at how we can best assist them in gradually returning to the workforce. These conversations can help us identify who’s at risk and ensure we offer the right support level.

STEPS

I’m excited about another study (Zegers et al., 2021) that will likely gain more attention as additional findings are published in the STEPS research conducted in the Netherlands. This study is particularly relevant because it specifically examines an occupational therapy intervention. It focuses on a very defined group—employees with contracts, excluding freelancers and those close to retirement age. This allows the research to hone in on a group where the impact of the intervention can be measured more clearly without the added complexities of varying employment arrangements or impending retirement.

If interested, I encourage you to check out the link to learn more about their findings. It’s encouraging to see occupational therapy being directly involved in such research, and I believe it will provide valuable insights as more results are shared. They’re not only looking at whether OT can improve return-to-work outcomes but also working to create a framework for identifying who might be at risk of delayed return and which factors most influence success. This research can eventually shape our practice guidelines and help us better support our clients returning to work. So keep an eye on this study—there’s more to come, and I think it will be very informative for our field.

Factors in RTW

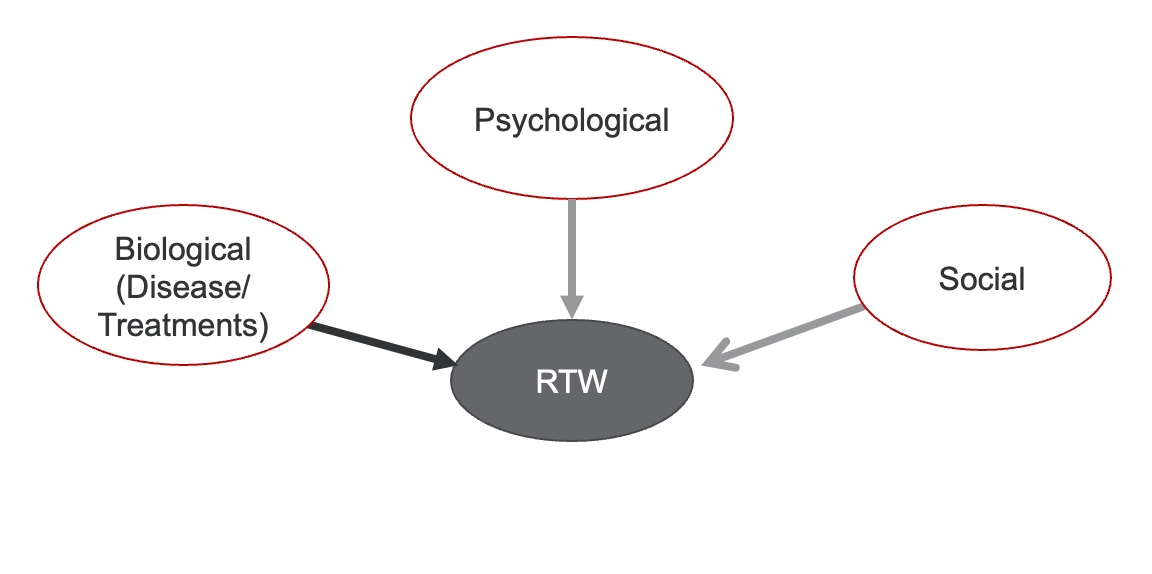

I developed a model (Figure 1) that I often share with my clients when they struggle to return to work.

Figure 1. Model of factors for returning to work.

I explain it by acknowledging that they’ve been through a lot—illness, treatments, and, in some cases, ongoing medication like hormone therapy, which can continue to affect their ability to get back to work. However, I also point out the areas where we have some influence and can focus our efforts.

One of those areas is the psychological aspect. It’s not uncommon for clients to feel anxious, sad, or even angry. I try to validate these feelings because they naturally respond to what they’ve experienced. While they might benefit from working with a psychologist to dig deeper into those emotions, I can still support them as an OTP by focusing on building resilience and identifying when they’re starting to regain their strength and confidence. Those who show even a bit of psychological growth—perhaps feeling more capable or optimistic—tend to have a better chance of returning to work successfully.

We also need to consider the social aspects. For instance, does the person have a high or low income? Are they going through this alone, or do they have a support system? Do they have children or family nearby, or are their main sources of support far away? These factors can significantly impact the transition back to work and make it much harder when support is lacking.

I sometimes find it helpful to visually map this out with the client. I ask them what they think could help or what might be making it more difficult. Creating this visual together can be quite revealing because clients often identify factors they hadn’t consciously acknowledged before. And while there are some things we can’t change—like the amount of chemotherapy they had, their age, or the nature of their job—what matters is identifying where they can regain some control. That’s the challenge we tackle together: finding those specific aspects where they can feel empowered and create a plan to work on them, which, in turn, helps them feel more capable of returning to work.

Other Factors to Consider

I want to share a few more examples to illustrate some of the nuances that impact a person’s return to work. Let’s consider the difference between freelance workers and employees with contracts. Freelancers and business owners often return to work more quickly because they have more flexible schedules. They might also feel more urgency to return because their income depends on it. However, the process can be slower for those with contracts, as they may have more formal structures and protections in place that allow them to take additional time for recovery. It varies depending on the laws and policies of each country.

The travel time is one factor that’s easy to overlook but very important. I always make a point of asking about the commute when someone is starting back at work. Typically, travel isn’t accounted for in the total working hours, but I recommend including it in the beginning stages of returning to work. It makes a huge difference whether someone has a five-minute walk to the office or a 45-minute journey involving multiple transfers on public transportation. That travel time can add significant physical and mental fatigue, especially when readjusting to a new routine.

I’ve even worked with clients and their managers to see if work hours can be adjusted to accommodate the commute. For example, could they start later in the morning to avoid rush hour or work from home a couple of days a week? With the changes brought on by the pandemic, remote work has become much more accepted. While COVID didn’t bring many positive outcomes, it did show us the potential of flexible working arrangements, which we can use to our advantage now.

In professions like teaching or nursing, I often suggest easing into the return by starting with lighter tasks, like administrative work. It helps to reacclimate to the work environment without the immediate pressure of high-stakes responsibilities. Sometimes, just a week or two of reduced hours or alternate duties can boost confidence and allow the person to re-engage with their work identity before fully stepping back into their role. Building up gradually—working half-days initially, then assessing their capacity—gives them room to adjust.

Another crucial area to explore is the nature of their communication with supervisors and colleagues. I remember a client recently expressing frustration, saying, “My boss just doesn’t get what I’ve been through.” But when her husband gently reminded her about her more supportive direct manager, she realized that there was someone at work willing to help her. This shift in perspective opened the door to a more productive conversation about her return. It’s a good reminder to encourage clients to identify workplace allies and work closely with them to outline a manageable plan.

Referring to a social worker or psychologist can be essential for those dealing with high levels of anxiety. As OTPs, we must check our clients’ ability to communicate their needs and set boundaries. For example, can they say to a well-meaning but overbearing colleague, “I’m happy to see you, but I need some space right now”? Setting those limits can prevent burnout and help establish a smoother transition.

I also like to discuss managing expectations. Clients often expect to return to their old routines, but setting realistic goals is important. I suggest breaking down the day: maybe they’re fine for the first two hours, but fatigue sets in later. It’s important to recognize those patterns early on and adjust accordingly, like ensuring the last hour of their day isn’t packed with high-stress meetings. Similarly, if they have household responsibilities, we need to strategize how they can balance those with work. It’s not just about being back at work; it’s about maintaining their quality of life as they return.

I’ve found that people who approach the process with the understanding that it will be challenging are often better prepared to navigate those hurdles. On the other hand, those who are overly optimistic and think it’ll be easy sometimes struggle more when reality doesn’t meet their expectations. For professionals like teachers or nurses, I might suggest partnering with a colleague initially to share the workload and reduce the pressure. That option to step back can be reassuring and allow them to sustain their endurance.

The good news is that with time, people often do get back on track, particularly if the prognosis is positive—such as with breast cancer. But we need to remind them that there’s no set timeline and that taking things one step at a time is okay until they find their new rhythm.

Research, Cont.

Long-Term Retention After Treatment for Cancer

Another researcher from the Netherlands, de Boar et al., 2020, has done some insightful work in this area, specifically focusing on identifying who struggles the most with returning to work. Her findings point to some clear risk factors: older individuals, those who’ve undergone extensive chemotherapy, or those with significant negative health outcomes. For example, someone who’s just had a reconstruction might be dealing with numbness, pain, or simply not feeling like themselves, which can significantly hinder their ability to return to work.

One of the key insights from her research is that the inability to adjust work conditions is a major barrier. But this is exactly where we, as OTPs, can step in. Often, there are more possibilities than the employee or even their boss initially realizes. For instance, starting with some online work or setting up a hybrid schedule can help someone ease back in without being overwhelmed. I’ve seen cases where people dive in too quickly—starting with half-days, five days a week—before they’re truly ready. What usually happens? They find themselves exhausted, and their abilities start to decline again.

That’s why it’s so important to emphasize the "start low and go slow" approach. Taking it step-by-step and gradually increasing work hours helps clients maintain a grip on their capacity and prevent burnout. As professionals, we need to see those at higher risk and those with poorer return-to-work outcomes keenly. It’s a role beyond simple physical accommodations; it’s about looking at the person holistically and ensuring they feel supported every step.

This is why our role as OTPs is so crucial. We can make a meaningful difference by advocating for flexibility, suggesting incremental changes, and identifying creative solutions for both the client and their workplace. I believe there’s a growing recognition of this in the research, and I’m optimistic that we’ll see more studies emerging with OTPs at the center of return-to-work interventions.

It’s not just about prognostic factors—although those are a big piece of the puzzle—it’s also about how we collaborate across different professions. Working alongside physical therapists, psychologists, and occupational health specialists shifts the focus to a more comprehensive view of what a successful return to work means. We’re moving beyond just "getting back to the job" and looking at sustaining it to promote long-term health and well-being. So, even though the interventions aren’t exclusive to OT, we have a critical role in ensuring those returning to work feel empowered, supported, and truly ready.

Prognostic Factors

More compelling research from den Bakker and colleagues, 2018, specifically examined return-to-work outcomes for individuals with colorectal cancer. At one point, I worked with quite a few people facing this condition, and as an OT, I found that the focus often shifted to practical concerns like how to sit comfortably or finding the right clothing to accommodate a stoma. It may sound simple, but small details can make a huge difference for these clients. For instance, I noticed that wooden chairs, which you might not think of as being particularly comfortable, were often a better option because they provided more even pressure and support compared to some cushioned seats that could press awkwardly on the stoma site.

This research didn’t just look at those practical aspects but also explored how factors like chemotherapy, age, and comorbidities impact the ability to return to work. What stood out was that all these elements—higher age, more intensive treatment, and multiple health conditions—tend to have a compounding effect, making it more challenging for people to re-enter the workforce. The study emphasized that we need to pay special attention to individuals who fall into these categories because they are at a much higher risk of delayed or unsuccessful return to work.

So, while this research isn’t solely about OT, it points to areas where we, as occupational therapy practitioners, can offer specialized support. For instance, by addressing seating concerns, helping with clothing adaptations, and managing fatigue, we can alleviate some physical and psychological barriers these individuals face. And as part of a larger team—working alongside physical therapists, dietitians, or occupational health specialists—we can ensure that we’re looking at the whole picture, not just cancer itself, but the real-world, day-to-day challenges of getting back to life and work after such a significant health journey.

Measure RTW

When discussing return to work, I believe we’re moving towards more specific data for different cancer types, like breast or colorectal cancer. As research expands, we'll better understand what OTPs can uniquely contribute in these contexts. But one thing I’m curious about is how we, as OTPs, measure return to work with our clients. Even if you haven’t worked with cancer survivors specifically, I’d love for you to think about what you might consider measuring to gain a clearer picture of success in this area.

From my own experience, I remember grappling with this during my thesis work. There are many different ways to quantify return to work, and it’s not always straightforward. Even something seemingly simple, like determining when a client has successfully returned to work, can vary depending on the lens you’re using. Are you looking at timeframes—three months, six months, a year post-diagnosis? Or are you measuring the number of hours they can work compared to their pre-cancer schedule? For instance, if someone used to work a 40-hour week and is currently managing 10 hours, you might record it as 10 out of 40. It’s a simple way to show progress and identify gaps.

One useful tool is the Work Ability Index (WAI), which breaks down different aspects of a person’s readiness to return. It asks clients how capable they feel about returning to work, physically and mentally, and it can offer a nuanced view of how they perceive their abilities.

Another measure is the Work Role Functioning Questionnaire (WRFQ), which digs deeper into various domains of job functioning and helps paint a more detailed picture of a client’s work-related strengths and limitations. Both can give us insights into the factors influencing return to work from the client’s perspective.

For those who might not be using formal measurements, I’ve noticed that some OTPs naturally focus on aspects like fatigue management or use tools like the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) to track perceived changes in daily functioning. That’s completely valid, too, as it ties directly into how someone views their overall performance and satisfaction in daily life, including work.

However, I do think having some form of structured measurement is helpful. For example, documenting when the last chemo session or surgery occurred can be very telling, as it helps set a timeline for recovery and progression. From there, you can start small, identifying where clients are in their return-to-work journey and addressing barriers step-by-step. For some, being at zero—meaning they haven’t attempted any return to work yet—can reveal a lot. Is it due to fear, uncertainty about their abilities, or a lack of support? Maybe the workplace itself isn’t providing the right accommodations, or they’re unsure of how to start exploring an alternative role.

These measurements, whether a formal tool like the WAI or simply tracking a few key indicators, can give us a clearer picture of where to intervene. Some of you might already use these tools, while others are beginning to explore them. Either way, I appreciate hearing your approach. These tools aren’t just checklists—they’re built on research and contain the critical questions that help us understand what’s important for our clients. So, if you haven’t tried using one, I encourage you to consider integrating it into your practice. It can be a powerful way to better grasp a person’s readiness to return to work and tailor your interventions more effectively.

Research, Cont.

Brain Tumor

Let’s look at another recent piece of research from 2023 (Pilarska et al.) that involved an OTP, this time focusing on brain tumors. When you compare brain tumors to other cancers, like colorectal or breast cancer, the impact is fundamentally different because the brain is such a central organ—affecting everything from behavior to cognitive function. The nature of the disease and its effects can be unpredictable and complex, making return to work extremely challenging.

I was recently involved in a case where I worked with a woman who had a brain tumor. It was a difficult situation, and I remember how rapidly her behavior and abilities changed. Initially, she was a high-functioning, highly-educated professional, but she started struggling with basic tasks and losing the ability to organize and plan. We needed to bring her sister into the sessions to help her understand what was happening and to assess whether she could still manage at home. These weren’t just minor slips but fundamental changes in her ability to function, which she could not fully recognize.

Slowly, we had to guide her through the realization that her previous job was no longer feasible. It was heartbreaking to watch her come to terms with it, and there were many difficult discussions with her employer and even government agencies to secure financial support. The systems we have in place here in Holland were a relief to some extent, but it didn’t change the emotional weight of letting go of her previous work identity.

As the tumor progressed, her sense of self began to shift more dramatically. Even when she avoided talking directly about her condition, it was clear that she was becoming increasingly frustrated and disoriented. This avoidance isn’t uncommon for individuals dealing with active cancer. It’s a delicate balance—trying to support someone in coming to terms with their new reality without forcing them to confront it too directly if they’re not ready.

The ICF framework (International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health) was incredibly useful in her case. It helped break down the complexity into more manageable parts. For her, it was primarily about understanding which functions were affected—things like memory, executive functioning, and planning skills. We focused on identifying specific changes in cognitive functions and how they impacted her ability to perform daily activities, like managing appointments or maintaining a daily schedule. It also guided our approach to understanding her participation limitations at home and in the workplace.

As her condition worsened and the tumor grew, we had to coordinate more closely with her general practitioner and her family. It wasn’t just about work anymore—it became about ensuring her day-to-day life was manageable, even in small ways. For example, she’d forget appointments completely, no matter how many reminders we put in place. Each time, we’d adapt, trying to find solutions that gave her some control in an otherwise overwhelming situation.

This case reinforced how valuable an OTP’s role can be in these complex cases. Our work isn’t always about achieving a successful return to work; sometimes, it’s about helping someone navigate their new reality and providing support as they redefine their identity outside their previous job roles. I found that, by approaching her with patience and by listening deeply, we were able to have some of the most meaningful conversations despite her cognitive challenges. It’s not always easy, but you can make a difference if you know how to approach people with brain involvement.

This area needs much more focused research, given the intricacies involved and the profound impact on a person’s life. It’s not just about modifying work tasks—it’s about supporting the person through a fundamental change in who they are and how they interact with the world. And that’s where I think our profession can play an immensely valuable role.

Treatment

I want you to consider how you currently care for return-to-work clients. Or, if you’re thinking about working with this population in the future, how do you envision delivering that care? Would you take a more vocational approach—perhaps focusing on discussions while the client is still in the hospital or on the ward? Or would you prefer to meet them at home, where you can assess the real-life context of their challenges?

One option is providing written resources that clients can refer to, such as a PDF with tips and strategies for returning to work. This could be especially useful for more independent people who want to read through information at their own pace. But beyond the written format, would you lean more toward face-to-face one-on-one or small group conversations? And what about online sessions? I know I’m speaking to all of you virtually, and this same format could work well with clients using platforms like Zoom or Microsoft Teams, making it easier to stay connected without the need to travel. You might even consider a hybrid approach—a mix of in-person and virtual options to fit each client’s needs and preferences.

Combining strategies allows you to adapt to the client’s circumstances, literally and figuratively, meeting them where they are. For example, you might begin with online meetings to reduce travel stress but transition to in-person sessions to better understand their abilities and context.

I’ve found that hybrid care is the most effective in many cases. Take the example of the client with the brain tumor I mentioned earlier. Initially, I saw her mostly through online sessions, but I realized I was missing some of the nuances in her cognitive abilities and behavior. Bringing her in for in-person sessions gave me a clearer picture of what was happening and allowed me to better plan with the interdisciplinary team. This in-person contact made identifying what the psychologist and other professionals needed to address easier.

While I appreciate the convenience and flexibility of online sessions, sometimes, you need a face-to-face connection to understand a client’s needs. That’s why I advocate for a mixed approach—offering the ease of digital contact when it suits but balancing it with in-person evaluations and discussions when necessary. This allows us to provide more tailored and holistic support, the ultimate goal for anyone working in this space.

Vocational Therapy or Care by Computer/PDF…

In the Netherlands, they’ve developed a fantastic resource in the form of a PDF called “You Shouldn’t Run, You Should Plan,” specifically focusing on managing energy levels. It’s incredibly straightforward and practical, making it easy to share with clients. One of its key features is a daily energy measurement tool, where people track their activities and see how much energy each one takes. This can be a great visual tool to review together—perhaps by sharing your screen during a session—and discussing how their energy fluctuates throughout the day.

A common pattern I see when using this tool is that nearly everyone will say they’ve planned time for relaxation. But when I dig deeper and ask two questions—“Is it truly relaxing?” and “Does it genuinely restore your energy?”—the answers often shift. Many clients realize that what they consider “relaxation,” such as scrolling through their phone or engaging in casual work-related chats, isn’t giving them the restorative energy they thought it was. It’s nice, but it still consumes energy, which is important for us to highlight, especially when working with people who are in a fragile state.

This PDF also offers a great structure for discussing how to pace oneself at work. I’ve found it valuable to go through their workday step-by-step, breaking down each activity and examining which parts are energy-draining versus energy-giving. For many, even social interactions they perceive as “relaxing” can be surprisingly exhausting during recovery.

I’m also thankful for platforms like Zoom and Microsoft Teams, which allow us to provide this kind of support remotely. They allow us to share these resources and have these conversations even if travel isn’t feasible.

Workbook Intervention

If we look closer at what we can provide as occupational therapy practitioners, there’s a particular approach that I find valuable—using workbooks. I came across a publication that evaluated the effectiveness of a workbook, and I think it’s a perfect example of a practical tool that empowers clients. What I love about providing a workbook is that it shifts people from the passive role of a “patient” to the more active role of a person regaining control over their situation. During those weeks of chemo, surgeries, and treatments, people can easily get caught up in the routine of being a patient. However, giving them a structured way to track their thoughts, feelings, and decisions through a workbook can restore some sense of autonomy.

I often encourage clients to start with something simple, like keeping a diary. I suggest they write down their decisions, who they’ve spoken to, and how many hours they’ve worked or engaged in other activities. It’s not just about documenting; it’s about helping them to get a clearer picture of how they’re feeling, what’s working, and what’s not. I remind them that their boss or colleagues won’t know what’s going on internally unless it’s communicated. By writing it down, they can more easily identify patterns and ask themselves, What can I change to feel better? This awareness can help them advocate for themselves at work and in other settings.

The research I’m referring to was a feasibility study conducted in the UK (Grunfeld et al., 2018). The purpose was to see if the workbook approach was effective and if any adjustments needed to be made before rolling it out on a larger scale. Although they used randomized control principles, which means they tried to evenly distribute participants across groups, they also emphasized the importance of diversity within the sample. This is key because if you only include a certain subset of people—say, those who are highly motivated—and leave out those who might be struggling more, the results won’t be as meaningful or representative of the broader population. For example, including individuals from varied ethnic backgrounds, such as British Caribbean communities or other ethnic minorities, ensures that the intervention is relevant and accessible to everyone.

I apply this principle in my own work by making sure that, if I’m using a workbook or similar tool, it’s customized to each client’s situation. For those who might be feeling overwhelmed, I make things as straightforward as possible. I write down key names—mine, the physical therapist's, and any other team members—so they have a clear point of reference. I often explain the different factors that might impact their return to work, and I encourage them to take notes themselves. That way, they’re not just passively receiving information; they’re actively engaging in understanding their own needs.

There are so many ways to adapt these tools to fit individual needs. It could be something as simple as listing out relaxation strategies or breaking down a complex work task into manageable parts. But the core idea is to provide a tangible resource that clients can refer back to—a tool that helps them reflect, strategize, and regain some control over their situation. It’s not just about the content of the workbook, but about the process of using it to facilitate self-awareness and build confidence.

Workbooks can also serve as a bridge for those conversations that can be difficult to have, such as acknowledging when a previous role might no longer be a good fit, or when a client needs to consider alternative tasks or schedules. Through structured reflection and planning, clients can approach these discussions with more clarity and confidence. In the end, it’s not about filling in boxes—it’s about empowering clients to navigate their own path forward, even when the road feels uncertain.

Create a Module

If you’re looking to start working in this area or if you already are and want to expand your impact, I think it’s wonderful to consider creating a structured module to guide your sessions. You can start with something as simple as a PowerPoint or a file where you outline the different topics you want to cover. One approach that’s proven effective is to combine both individual and group formats. Group sessions—whether in person or online—can be incredibly powerful because they allow people to connect, share their experiences, and support one another in a way that’s distinct from one-on-one therapy.

For example, I’ve seen how valuable it is when a group member expresses concerns about wearing a wig and returning to work. Instead of just receiving advice from a therapist, they hear encouragement and similar experiences from others who are going through the same thing. That peer support is irreplaceable. It’s a completely different dynamic when people with shared experiences offer suggestions or share what worked for them. This sense of community can be a real turning point, especially in areas where people often feel isolated or misunderstood.

When you’re designing your module, think about what format suits your style and your clients’ needs. It could be a series of four group sessions focusing on different aspects of return to work. Perhaps each session has a specific theme: understanding workplace accommodations, managing fatigue, building confidence, or navigating conversations with employers. These are practical topics, but you can also create space for deeper discussions around identity shifts or the emotional challenges of transitioning from being a patient to being an active employee.

If online work is more feasible, you can easily build a structured set of topics into a digital format. Use PowerPoint to guide discussions and include prompts or activities to engage participants. I recommend including interactive elements like guided reflections or small group breakout rooms if your platform supports that. You can even incorporate video or written testimonials from others who’ve gone through the process, which can be a powerful motivator for those just beginning to contemplate returning to work.

It’s also helpful to have a few “anchor” resources, like a workbook in PDF form, that participants can use to track their progress. This can include sections for planning their return-to-work strategy, space to document key conversations with their employer, or exercises to evaluate their strengths and concerns. The workbook becomes a tool to refer back to, helping them feel more in control and organized during a time that often feels anything but.

For a more targeted program, you could focus on a specific group, such as women returning to work after breast cancer. In those cases, you might develop four focused sessions to tackle essential topics:

- Session One: Understanding Legal Rights and Work Accommodations: Discuss workplace accommodations, navigating the conversation with an employer, and knowing one’s rights and options.

- Session Two: Planning for a Gradual Return: Help participants build a step-by-step plan for resuming work. Include guidance on setting realistic expectations, managing energy, and pacing themselves to prevent burnout.

- Session Three: Addressing Physical and Emotional Changes: Explore the impact of physical changes (e.g., managing a wig, prosthetics, or lymphedema) and emotional adjustments. Provide a space for people to talk about identity and self-image.

- Session Four: Building Confidence and Communication Skills: Role-play scenarios for interacting with supervisors and colleagues, managing reactions, and setting boundaries. End with action planning for continued support.

Having a structured module like this makes it easier to guide the sessions and ensures you cover all the critical areas. But don’t feel constrained by a rigid plan—each session should allow flexibility to respond to participants’ immediate concerns.

Combining education with peer support and reflective activities can make a difference. It’s about creating a safe space for clients to explore their feelings, share strategies, and build a practical plan for their next steps. Even a simple module with clear goals can help transform uncertainty into a more confident approach to returning to work. It doesn’t need to be complex; what matters is that it provides structure, guidance, and space for clients to feel empowered in their return-to-work journey.

Homework for Clients/Examples

One approach I often use is to help people actively map out their return-to-work plan. I ask them to consider a realistic schedule starting in week 35, for example, and maintain that schedule for a few weeks before making any changes.

Week | Hours | What | Details | Check |

35/36 | Mon. 1 x 2? Tues. Wed. Thurs. Fri. | Extra: Beside a colleague | Normally 30 hours (Mon., Tues., Wed…) |

|

36/37/38 | Mon. 1 x 2 Tues. Wed 1 x 2 Thurs. Fri. | 1 x 2 independent |

|

|

39/40/41/42 | Mon. 1 x 3 Tues. Wed. 1 x 3 Thurs. Fri. |

|

|

|

A common mistake is to build up too quickly, which usually leads to burnout. We might decide to start with two hours on a Monday, but if the client says, “Mondays are tough because I’m still tired from the weekend,” we adjust and start on a Tuesday. This level of flexibility is key. It’s also helpful to clarify whether they’ll be doing their actual job or working alongside a colleague in a supportive role. Knowing these details up front helps everyone—both the client and their employer—understand the progression.

I always make a point of documenting what their regular work hours looked like before, so we have a baseline reference. Then, I encourage them to track their experience: How did those first two hours feel? Was it manageable, or did it leave you drained? Were you able to do any other activities afterward, like shopping or cooking? This simple reflection can tell us so much. If they come back and say, “It was okay, but I felt exhausted for the rest of the day,” then maybe we need to keep the schedule stable for a few more weeks. Stability in these initial stages is often more beneficial than pushing to increase hours right away.

Sometimes, instead of aiming to do their full role, clients might shadow a colleague or take on alternate tasks just to get the rhythm of being back in a work environment. It’s not about completing the job to 100% capacity—it’s about regaining that feeling of engagement and purpose. I sometimes recommend stabilizing at a certain number of hours for as long as four weeks. This allows time to adjust and really settle into the routine. For example, if someone builds up to four hours a day, it’s important to factor in how they’ll handle the rest of the day, like doing errands or getting adequate rest.

It’s easy to assume that jumping from four hours to a full workday is a natural step, but I always caution clients to think through the entire day and week. Have you considered how this will affect your energy levels when you still have to take care of things at home? It’s a simple question, but it helps them put everything into context and see the bigger picture.

I remember one client who wanted a clear timeline: she wanted to be back to full capacity by Christmas. We set up a detailed plan, but as she started working, it became apparent that our initial plan was either too ambitious or, in some cases, too conservative. By documenting how each stage felt and adjusting accordingly, she had a better understanding of what was realistic. The plan became a tool for discussion and adjustment, rather than a rigid path to follow. This ongoing reflection—whether the pace feels too quick or too slow—helps people regain a sense of agency and makes the process feel less overwhelming.

Another technique I use when clients are hesitant is to ask reflective questions like, What’s a positive aspect of starting work tomorrow? What feels difficult about it? Often, people tell me they’re waiting until they feel completely like themselves again before starting, which is an understandable but unrealistic expectation. I share with them that this sense of being 100% themselves might not return right away—it’s a process that happens gradually, and taking small steps to return to work can be part of rebuilding that sense of identity.

On the other hand, there are also those who want to rush back, feeling ready to jump into full-time work immediately. I always caution them that a quick start often leads to a sudden crash in energy levels, which can be demoralizing. If they begin with a steady, step-by-step approach, they have more control over the process and can handle setbacks with more resilience.

These reflections are helpful not only for clients but also for me as their therapist. When I document these experiences, it’s easier to see patterns and plan accordingly. I often use worksheets where clients can outline how many hours they want to build up to, how they feel about it each week, and whether their plan needs adjusting. One client even used it to set goals like, “I want to feel ready by summer,” and the document became a shared guide that we adapted as needed.

Another effective strategy is preparing clients for difficult conversations. For instance, I often work alongside social workers to practice communication scenarios like asserting boundaries with a boss who keeps piling on tasks or explaining limitations without feeling defensive. We might role-play these conversations, practicing responses until the client feels confident. This is crucial because managing expectations and advocating for oneself at work is often one of the biggest hurdles. If clients are empowered to communicate their needs clearly, they’re more likely to have a positive experience re-entering the workplace.

Group sessions are also invaluable for this kind of preparation. People share tips, support each other, and provide insights that I, as a therapist, can’t always offer. For example, someone might be frustrated about how tiring it is to explain their situation to different colleagues repeatedly. Another group member might suggest drafting a short email rather than repeating the same conversation. That kind of peer support is priceless, and it gives clients the feeling that they’re not alone in facing these challenges.

We also saw this group dynamic a lot during post-COVID recovery programs. The evidence base for these programs is still developing, but putting people together who are navigating similar experiences provides an incredibly valuable support network. It’s the same with cancer survivors—the more they can connect and share strategies, the stronger their coping mechanisms become.

So, whether it’s through structured planning, reflective diaries, or role-playing scenarios, our role as OTPs is to help clients navigate the practicalities of returning to work while also addressing the deeper emotional and social aspects. There’s no one-size-fits-all approach, but having these tools at hand helps us tailor our support to each individual's needs.

Summary/Take-Home Message

To summarize, occupational therapy can play a significant role in supporting social participation and return to work for individuals recovering from cancer. As OTPs, we collaborate with other professionals to address the various factors that influence successful re-entry into the workforce. Factors like the amount of chemotherapy or the client’s age can make the process more challenging, and the ICF model is an excellent tool to clarify how function, activity, and participation interact. Documenting these elements can help create a clearer picture for the client and the care team.

One key message is that our role is to focus on graded activity—building up step-by-step—to help clients regain confidence and function. For example, starting with work without deadlines and adjusting tasks based on current capabilities can set a positive foundation. This gradual approach prevents the common pitfall of clients rushing back too soon only to experience setbacks.

There’s still a need for more research on specific OT interventions in return-to-work scenarios, but early evidence shows that step-by-step support, combined with flexibility and tailored strategies, can make a substantial difference.

Case Example

One story that stands out is of a client who had a one-year contract and, due to her cancer treatment, didn’t return to work within the expected timeframe. Under Dutch law, her employer could let her go, and the transition to government support left her feeling isolated and unsupported. Instead of giving up, she took control of her path. Even though her doctor advised taking it slow, she had a clear vision: she wanted to start her own catering business, focusing on Caribbean cuisine.

Despite her physical limitations, she adapted—using modified knives to reduce joint strain and slowly building her business. Now, she not only runs a successful catering company in Holland and the Caribbean but also employs others, showing incredible resilience and resourcefulness. Her journey is a powerful example of how, with the right support and personal drive, even significant barriers to returning to work can be overcome.

So while cancer can present serious challenges in returning to work, it can also lead to unexpected and empowering new directions. It’s our role to support clients through these transitions, whether they’re returning to their old job or finding new ways to engage in meaningful work.

Take Home Message

Overall, occupational therapy practitioners can play a crucial role in facilitating return to work by using graded activity and focusing on social participation. This structured, step-by-step approach allows clients to regain confidence and reintegrate gradually, avoiding the common pitfalls of rushing back to work too soon. In addition, ensuring that work environments are adjusted and that clients are equipped to communicate their needs is essential to our role.

More research is still needed to refine our interventions and validate our approaches, but as more studies emerge, I’m confident that OTPs will continue to be central to shaping return-to-work strategies.

Questions and Answers

Thank you for all the thoughtful questions and comments. I appreciate your engagement, and I’m happy to address some of the points raised.

Do you have OT Assistants (COTAs) in Holland?

Not at the moment. Sometimes, larger rehabilitation centers or departments will have assistants, but we don’t have officially registered OT assistants like they do in the United States. It’s a topic we’re starting to discuss more seriously. Just today, I spoke with a colleague who recently retired from the UK, and we talked about the potential benefits of establishing this role in Holland. From an economic standpoint, OT assistants could be very helpful in providing high-quality care. However, for now, this remains an area of development.

Have you come across research on family support as a factor in return to work?

Yes, family support can play an important role, but I often focus more on building the strength and autonomy of the individual. Sometimes, clients ask me to accompany them to meetings with their employer, but instead of stepping in, I encourage them to consider what they want to say and why they feel they need me there. My goal is to empower them to advocate for themselves and avoid becoming dependent on external support. Leaning too much on others can sometimes make a person a “client” rather than an independent worker. Family involvement can still be valuable in certain circumstances, especially for emotional support and practical help.

Thank you for the presentation. As an OT, I had to return to work after a diagnosis of colon cancer. I wish I had support returning to work.

Thank you for sharing your personal experience, Diane. It’s such a poignant reminder that even those of us within the profession might not always have the support we need when we’re on the other side of care. I hope that by increasing awareness and refining our return-to-work strategies, more of us can feel supported during these challenging transitions.

Have you seen positive outcomes from in-home patient care versus outpatient care for return-to-work possibilities?

From my experience, outpatient care is typically more effective for focusing on return-to-work issues. When clients are still in the hospital or another facility, engaging them in that process is hard because they’re often not yet thinking concretely about work participation. Providing education and preliminary guidance while they’re still in acute care can be helpful—like offering tips about managing fatigue or the potential impact of treatments on work—but the real progress tends to happen when clients are back in their environments and ready to start transitioning back to work. Outpatient settings are ideal for actively guiding them through the return-to-work process and tackling those real-life barriers as they arise.

The Workability Index and the Work Role Functioning Questionnaire will help set goals and measures.

I’m glad to hear that. These tools are excellent for understanding how clients perceive their ability to return to work and where the challenges lie. They can provide a structured way to track progress and adjust goals accordingly.

How do you justify the need for occupational therapy in return-to-work scenarios to insurance companies? Do you have an example of how you would document the need?

This is a common challenge. In the Netherlands, some OTs work directly for insurance companies, making it easier to justify services within that framework. However, when it falls under regular care, getting coverage for return-to-work support can be difficult unless it’s explicitly included in the health insurance plan. Documentation should connect the client’s functional limitations to specific job-related tasks and outline how OT interventions will address these barriers. For example, you might describe how graded activity and fatigue management strategies will enable the client to meet specific work-related goals, such as increasing hours gradually without triggering a setback. Tying the intervention directly to the client’s ability to perform essential job functions can sometimes strengthen the case coverage.

I’m an OT working in home health and undergoing cancer treatment for endometrial cancer. I have one chemotherapy infusion to go, and I’m facing many of these issues myself as I prepare to return to work. This has been so helpful.

Thank you for sharing. I’m glad this session was helpful for you. It’s so powerful to hear from fellow professionals who are navigating these challenges firsthand. Wishing you the very best as you complete your treatment and begin your return-to-work journey. Please take it one step at a time and give yourself the grace and patience you would extend to your clients.

Returning to work after cancer requires individualized support, flexible strategies, and professional collaboration. The role of OT is essential in addressing not only the functional aspects but also the emotional and social barriers that clients face. Thank you all for your questions and insights and for sharing your experiences. Together, we can continue refining our approaches and advocating for better client support systems. If you have any further questions or thoughts, please feel free to reach out!

References

Please see the additional handout.

Citation

Kroese-King, J. (2024). Return to work after cancer and the role of occupational therapy. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5753. Available at https://OccupationalTherapy.com