Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Therapeutic Use Of Pilates For Improved Functional Participation, presented by Tina Dimopoulos, OTD, OTR/L, CHT, STOTT PILATES® Certified Instructor for Mat and Reformer.

*Please also use the handout with this text course to supplement the material.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to identify the historical similarities of Pilates and Occupational Therapy.

- After this course, participants will be able to describe the relationship between postural control, core strength, and upper extremity function as it relates to occupational performance.

- After this course, participants will be able to recognize how Pilates-based exercises translate into functional movement patterns.

Introduction

I am excited to be presenting today on a topic that I'm very passionate about and love to share. As a disclosure, this presentation is not formal training in any specific Pilates technique or method, nor is the presenter representing any specific method of Pilates. Occupational therapy practitioners are encouraged to pursue additional training and certification through a credible and recognized Pilates program prior to implementing Pilates exercises with clients in a clinical setting.

During this presentation, I would like to highlight how I blended Pilates with occupational therapy, my background as a certified hand therapist, and the neurological population. I will share the history of OT and the history of Pilates. You'll see many parallels between the two; I experienced those parallels firsthand when I had an injury, completed my standard rehab, and was recommended to Pilates shortly thereafter. At the same time, I was in school for occupational therapy, and I began to see parallels between many of the elements of trunk and postural control and how we can help clients. I was receiving some of those exercises and thought a modified version of this would help a patient with an XYZ diagnosis or help a client with this type of condition. And I'll share more about that as we go along. My professional career started with the neurological population and later transitioned into the orthopedic population.

To treat the whole body, I aimed to learn neuro and ortho populations in specialty areas, and Pilates jives nicely with that.

Key Components of Pilates

Let’s examine the key components of Pilates and how they parallel occupational therapy in history and practice.

Historical Relevance

Pilates was founded by Joseph Pilates, whose name the method now carries. Originally called by a different name, Pilates-based techniques were applied during World War I with bedridden inmates. Joseph Pilates encouraged movement—sometimes very minimal—in individuals who were confined to their beds. His approach emphasized both physical and emotional well-being, highlighting the mind–body connection.

He demonstrated remarkable creativity, much like we value in occupational therapy. He attached springs for resistance and straps for assistance, using the beds or cots available, allowing patients to exercise in gravity-eliminated or gravity-minimized positions. These adaptations allowed clients to strengthen their bodies and work multiple systems despite severe mobility limitations. While he may not have recognized it as such at the time, this was very much a rehabilitation-focused approach.

Occupational therapy’s history runs parallel. Formally established in the early 1900s, OT also played a role in rehabilitating individuals injured in World War I. Our profession has always focused on client-centered care, creativity, the use of meaningful activity, and the promotion of both mental and physical well-being, treating the individual holistically.

Key Components of Pilates

A defining feature of Pilates is intentional breathing patterns during movement. In a Pilates-based exercise session, the practitioner cues the client on when and how to breathe, often exhaling with exertion or during a pause.

Trunk control and postural alignment are central. In Pilates, pelvic positioning is described in terms of “neutral” or “imprint” positions, which correspond to what we in OT would identify as anterior pelvic tilt, posterior pelvic tilt, or neutral alignment. Rib cage mobility is linked directly to breathing patterns, with expansion intended in three dimensions—anterior, posterior, and lateral.

From the pelvis upward, Pilates considers alignment through the rib cage, scapula, and thoracic spine. Because the rib cage is curved, the scapula rests on a curved surface, and understanding scapular movement and control is essential. Proper scapular mechanics support proximal stability, enabling effective distal function—a concept very familiar to occupational therapists.

Head and cervical alignment are also emphasized to correct misalignments and promote optimal positioning. Many exercises in Pilates aim to both strengthen and lengthen tissues, with the quality and precision of movement being as important as the movement itself.

Types of Pilates

There are several recognized forms: classical, contemporary, and rehabilitative. Classical Pilates, most common in New York City where Joseph Pilates originally taught in the U.S., adheres closely to his original methods. Contemporary Pilates incorporates modern exercise science, and rehabilitative Pilates is tailored to support clinical populations—making it most applicable to OT practice.

Rehabilitative Pilates can be performed using various equipment.

The mat: similar to a yoga mat, used for floor-based exercises.

The Reformer: an evolution of Joseph Pilates’ bed-and-spring setup, offering adjustable resistance via springs and straps. Clients can work in multiple positions—supine, prone, side lying, kneeling—with controlled resistance.

The Cadillac: a larger, more advanced apparatus, often combined with a Reformer.

The chair, barrel, and tower: specialized equipment pieces providing unique resistance and movement opportunities.

Each type of equipment offers flexibility for modifying exercises to match the client’s ability level, therapeutic goals, and safety needs, making Pilates a versatile tool for functional rehabilitation.

Optional Equipment

Let's review some pieces of equipment that would be handy. Figure 1 shows a Pilates ring.

Figure 1. Author with a Pilates ring.

This is a Pilates ring, also known as a Pilates circle. Other commonly used props include exercise bands, free weights or weighted balls, and exercise balls, which can be inflated, deflated, or partially deflated to meet the client’s needs. A yoga block is another helpful tool.

These props are often found in clinical settings and can be incorporated to help guide clients into proper form, support alignment, and facilitate the desired movement pattern during exercises.

Therapeutic Use of Pilates as an Adjunct to Formal Rehabilitation

Moving on to the therapeutic use of Pilates as an adjunct to formal rehabilitation, this is where we start to incorporate the research. When Pilates-based exercises are implemented in a clinical setting, they are intended to complement—not replace—traditional therapy approaches. Think of it like incorporating an exercise band into a treatment session to target specific shoulder or elbow movements for a set number of repetitions.

In the same way, Pilates-based exercises can be used purposefully to address postural control, trunk control, and scapular mobility and stability. By integrating these exercises alongside standard rehabilitation techniques, we can provide clients additional opportunities to improve alignment, strengthen stabilizing muscles, and enhance functional participation.

Therapeutic Use of Pilates and Fibromyalgia (Caglayan et al., 2022)

One 2022 article focused on the therapeutic use of Pilates with individuals who have fibromyalgia. The findings supported Pilates as a safe and effective therapeutic modality in a rehabilitative setting for improving pain, functional independence, and quality of life. Both mat-based and Reformer-based Pilates were found to be appropriate and beneficial interventions.

For clinicians experienced in working with fibromyalgia, these results align with what we often see in practice—clients present with varying pain levels and functional limitations. Pilates offers the flexibility to upgrade or downgrade exercises based on the client’s tolerance and goals. The primary therapeutic focus is on trunk stability and control, helping clients develop awareness of subtle postural changes and how those changes influence distal movement and function. This study reinforced that mat and reformer Pilates can be highly effective tools in this population.

Therapeutic Use of Pilates and Upper Extremity Function in Clients With Parkinson’s (Çeliker and Cengiz, 2024)

A 2024 randomized controlled trial examined the therapeutic use of Reformer-based Pilates exercises for clients with Parkinson’s disease, focusing specifically on upper extremity function. The study found statistically significant improvement in bradykinesia of the upper limbs. However, there was no substantial change in fine motor dexterity or grip strength.

This outcome makes sense when considering the foundations of Pilates. The method strongly emphasizes proximal stability, particularly scapular control, which likely contributed to improving bradykinesia. While fine motor dexterity and grip strength can be addressed, they are more likely to be secondary outcomes given the primary movement repertoire and focus in Pilates.

The study confirmed that Reformer-based exercises were safe and appropriate for this population. Clinicians often ask whether a client is suitable for Pilates-based interventions. The answer is that exercises can always be downgraded or upgraded to match the client’s functional level. At its core, Pilates addresses elements such as pelvic control and scapular mobility—components we often target in other manual or exercise-based approaches. The key is for the clinician to understand how to adapt the movements to meet the individual’s needs safely and effectively.

Therapeutic Use of Pilates and Upper/Lower Extremity Function in Breast Cancer Survivors (de Rezende, Guimarães, & de Paula, 2022)

Therapeutic use of Pilates has also been explored in breast cancer survivors—a population where research on Pilates-based interventions is steadily growing. In a randomized controlled trial, participants engaged in Pilates exercises demonstrated statistically significant improvements in both strength and flexibility of the upper and lower extremities.

As mentioned earlier, one of Pilates's unique benefits is its ability to strengthen and lengthen tissues, depending on the exercise selected. This study validated that dual benefit, showing meaningful gains in muscular strength alongside enhanced flexibility, key outcomes from both an anatomical and kinesthetic perspective.

Perhaps most importantly, the study also found a statistically significant improvement in participants’ quality of life. This reinforces the mind–body connection central to Pilates and aligns closely with occupational therapy’s holistic approach, where functional gains and overall well-being are equally valued.

Therapeutic Use of Pilates on Postural Improvement of University Students with Upper Crossed Syndrome (Phanpheng & Puntumetakul, 2024)

Another study examined the therapeutic use of Pilates for postural improvement in university students with upper cross syndrome—a population often characterized by a forward-flexed, kyphotic thoracic posture due to prolonged sitting and study habits. I selected this article to highlight the wide range of populations that can benefit from Pilates-based interventions.

This randomized controlled trial assessed mat-based Pilates, comparing 30-minute and 60-minute sessions. The results showed statistically significant improvements in cervical–thoracic alignment, shoulder muscle strength, and endurance. There was also a notable decrease in thoracic kyphosis, improved neck and head positioning, and enhanced postural awareness.

The postural awareness findings are particularly relevant to my work with individuals experiencing repetitive stress or strain injuries, often in a similar kyphotic posture. Pilates can directly target the core, integrating pelvic positioning, abdominal activation, diaphragm function, rib cage mobility, scapular control, and head and neck alignment. Because core stability is central to many Pilates exercises, these movements can translate into better posture and alignment. In this study, improvements in cervical spine alignment and postural awareness were primarily attributed to increased abdominal strength, reinforcing the interconnected nature of core stability and overall posture.

Postural Implications As They Relate to Function

Let's now talk about implications as they relate to function.

Proximal Stability for Effective Distal Use

As mentioned earlier, Pilates-based exercises are a powerful tool for developing proximal stability to support effective distal use. A strong trunk begins with the pelvis, which forms the foundation for trunk positioning, alignment, and control. Pelvic control and core stability are essential for efficient upper extremity movements, while the posture of the spine and pelvis directly impacts both upper and lower extremity movement patterns.

When movement patterns improve, clients often see functional benefits in everyday activities. For example, reaching above shoulder height to retrieve an item from a cabinet may be easier with improved thoracic extension, scapular control, reduced pain, and increased flexibility. Lifting and carrying tasks—whether moving a box or holding a young child—benefit from understanding how to engage the trunk and abdominals effectively. Movements like lateral reaching, getting in and out of a bathtub, or transitioning from sit to stand for bed mobility rely on dynamic trunk control.

As clinicians, we know that addressing the trunk and proximal joints can decrease stress on distal joints. This is especially important for clients with repetitive stress or strain injuries in the lower arm. Patient education plays a key role here, helping clients understand how trunk position and proximal joint control influence distal joint use. Poor posture can place added strain on smaller distal joints, and Pilates offers an effective way to target trunk positioning, alignment, abdominal engagement, and proximal stability to reduce this stress.

Postural awareness is another essential benefit of Pilates-based exercises, allowing clients to prevent re-injury. In my years in outpatient adult rehabilitation, I often saw the same clients return with the same type of repetitive strain injury. Initially, I would treat the affected area, which would improve, only to return six to nine months later. Over time, I recognized the need to address trunk stability more directly to break this cycle.

Pursuing Pilates training gave me the tools to connect trunk, pelvis, scapula, and thoracic stability with distal joint health. Educating clients on concepts such as pelvic tilting, neutral versus imprinted spine, and abdominal engagement during upper body use helped them understand the body as an interconnected system. This was often an “aha” moment for clients. When they began integrating Pilates-based exercises into their home programs—alongside targeted treatment for their referral condition—they experienced fewer recurrences and greater independence.

Ultimately, Pilates can effectively improve core strength, body awareness, and postural control, all of which contribute to injury prevention, functional independence, and long-term well-being.

Mind-Body Awareness

As mentioned throughout, one component I emphasize is mind–body awareness. As occupational therapy practitioners, we understand the value of the mind–body connection, and Pilates integrates this beautifully. With intentional breath work as a central focus, Pilates exercises require the client to be alert, present, and fully engaged.

Clients are encouraged to concentrate on the movement, using their breath to anchor their attention and return it to the exercise. This fosters more volitional movement patterns—clients are aware of their breathing and how they use their bodies. The intentional, precise, and deliberate movement patterns that define Pilates should also guide our general occupational therapy exercise prescriptions.

This emphasis reinforces that alignment, precision, and intentionality matter more than the number of repetitions performed. Often, when clients are told to complete “three sets of 10,” they focus on finishing the count rather than performing each repetition with care. In my practice, when issuing a home program, I’ll set a time frame instead, asking clients to complete as many high-quality repetitions as possible within a set number of minutes. I instruct them to focus on breath patterns, use a mirror if possible, and remain present throughout the exercise.

This approach shifts their mindset from simply checking a box to truly engaging in the movement. In doing so, the exercises become not only a physical intervention but also an opportunity to enhance mental presence, self-awareness, and overall well-being—a connection that naturally leads into the mental health benefits of Pilates.

Mental Health Benefits

Breath work in Pilates has both physical and psychological benefits. When breathing is performed intentionally—often using an inhale through the nose followed by an exhale through pursed lips, as if gently blowing through a straw—it has a calming effect. I frequently give clients this cue. This breath pattern not only supports movement but can also help calm the nervous system, making it a valuable tool during exercise and in self-regulation.

As discussed earlier, mindfulness plays a key role in body awareness. We want clients to be fully present with their exercises, avoiding distractions such as having the television on in the background. This focus on mindful movement supports stress reduction, which we clinicians understand well regarding the physiological effects of controlled breathing.

When clients begin to experience intentional, well-coordinated movement patterns and gain better control of their trunk, they often experience a boost in self-esteem. They recognize the connections between pelvic alignment, thoracic positioning, scapular mechanics, and effective extremity use. This awareness improves movement quality and reinforces their confidence and sense of agency in managing their bodies.

Concept of Flow

Flow is an occupational term that describes total immersion in an activity—when a person is fully engaged, focused, and absorbed in what they are doing. It represents the interaction between an individual’s traits and the activity itself.

When incorporating Pilates or Pilates-based exercises with a client, emphasizing intentional breath patterns paired with movement creates a rhythmic quality. Combined with focused attention on the task, this rhythmic nature can facilitate entry into a flow state. In this state, clients are not only performing exercises but are deeply connected to the process, experiencing physical and mental engagement.

This concept ties directly to occupational therapy and occupational science, as it reflects the therapeutic value of meaningful, immersive participation, where the client is not just completing a movement, but experiencing it in a purposeful, integrated way.

Pilates-Based Exercises and Functional Movement Patterns Specific to Occupation

We will now transition to Pilates-based exercises as functional movement patterns specific to occupation.

Motor Skills (OTPF)

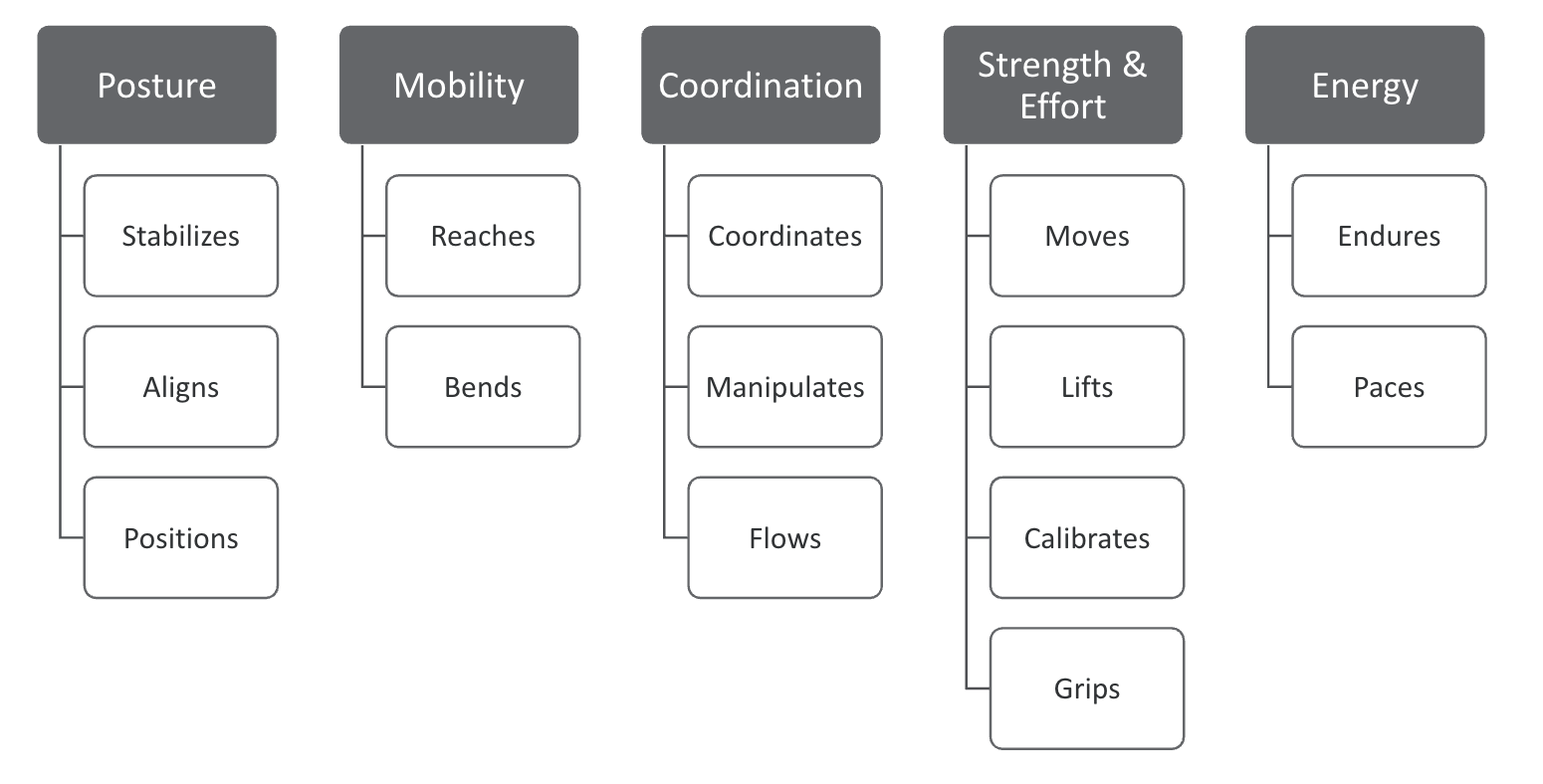

In Figure 2, you'll see elements from our OTPF or Occupational Therapy Practice Framework.

Figure 2. Motor skills from the OTPF (AOTA, 2002). Also, please refer to the updated OTPF in 2020.

In reviewing the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework, several motor skills directly align with the therapeutic use of Pilates-based exercises in a clinical setting.

Posture

Within the posture category, stabilization, alignment, and positioning skills are central. Pilates emphasizes intentional movement and alignment, which are foundational to every exercise.

Mobility

Skills such as reaches and bends are frequently incorporated, often paired with coordinates—linking upper and lower body movements, or coordinating the right and left sides of the body. Breath patterns are also integrated into this coordination.

Manipulates

When props are used—such as a Pilates ring, ball, or band—clients may need to manipulate these items while maintaining form and control.

Flow

Pilates’ rhythmic nature, often driven by intentional breath work, supports fluid movement sequences that connect naturally from one exercise to the next.

Strength and Effort

Clients may lift an arm, leg, or trunk segment, engaging in concentric or eccentric contractions. The therapist can guide force, speed, and control calibration to match therapeutic goals.

Grips

Proper grip is essential for safe and effective performance when equipment is involved.

Energy

Skills such as endurance and pace are highly relevant. Pacing is especially important in Pilates, as both breath and movement are intentionally timed for optimal alignment, control, and efficiency.

These OTPF motor skill elements illustrate how Pilates-based exercises can be purposefully incorporated into occupational therapy, targeting posture, movement quality, coordination, and overall functional performance.

Client Factors (OTPF)

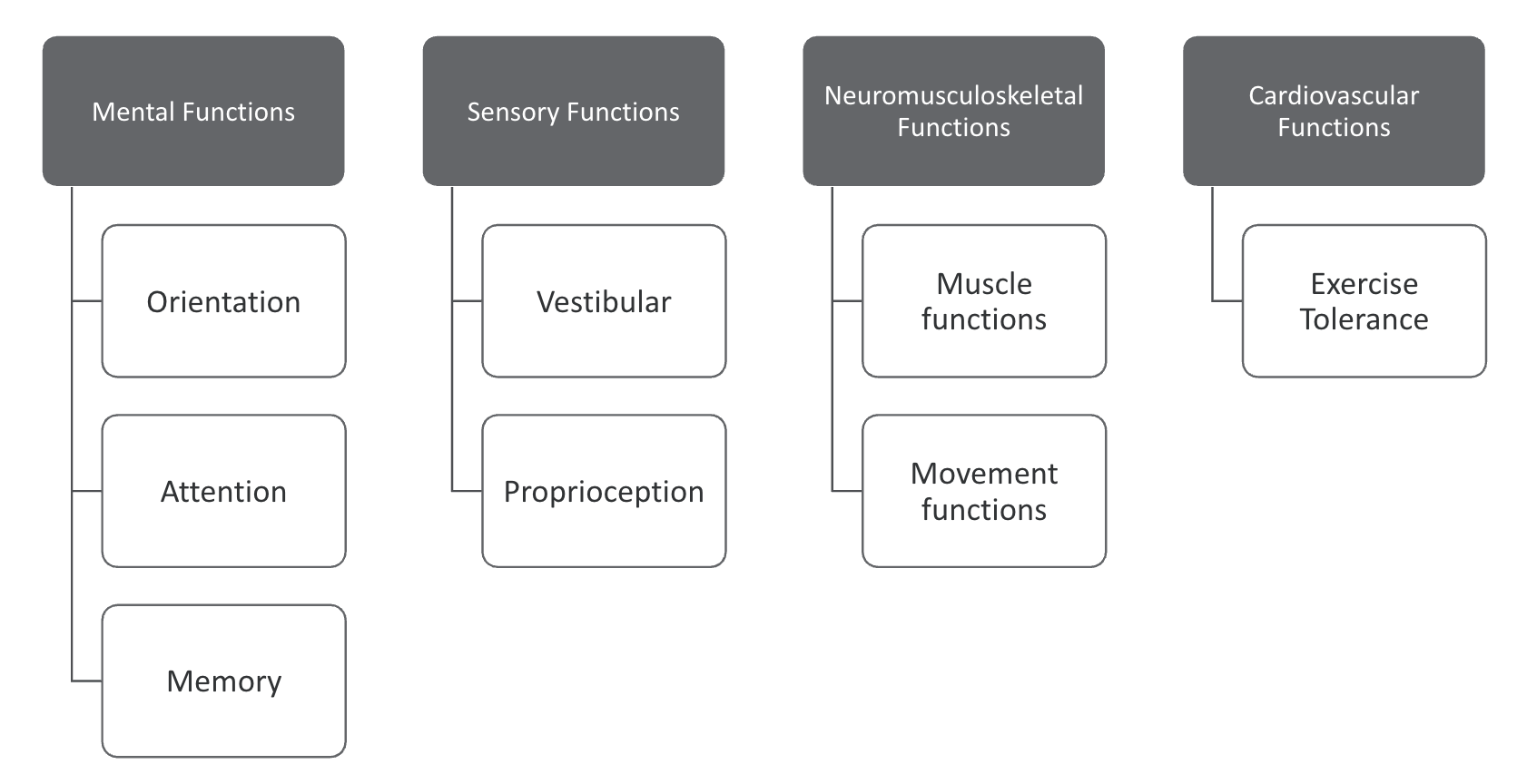

Let's talk about client factors, as seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Client factors from the OTPF (AOTA, 2002). Also please refer to the updated OTPF in 2020.

Once appropriately trained, clinicians can incorporate Pilates-based exercises into practice by carefully considering each client’s unique factors and needs. These exercises can be upgraded, downgraded, or otherwise modified to ensure safety, appropriateness, and effectiveness.

Due to the intentional breath patterns and precise movement control, Pilates has a significant mental function component. Kinesthetic awareness and orientation are essential—clients should be able to distinguish right from left, isolate specific movements (such as transitioning the pelvis from imprint to neutral spine), and demonstrate control in targeted areas (such as scapular protraction and retraction).

Attention is another key consideration. Because Pilates requires focus and deliberate execution, highly distractible clients may need exercises to be streamlined, simplified, or introduced in a controlled environment with minimal distractions. Memory is equally important; clients must recall the correct sequence, technique, and bodily sensations to safely and effectively practice exercises at home without direct supervision.

Sensory functions also come into play. Vestibular considerations are important when exercises involve positional changes relative to gravity, such as supine, side-lying, kneeling, or prone. Proprioceptive awareness is critical for understanding and maintaining proper body positioning in space throughout movements.

From a neuromusculoskeletal perspective, Pilates engages muscle and movement functions, requiring strength, stability, and control. Cardiovascular function should also be considered, as exercise tolerance and endurance will influence the frequency, intensity, and resistance prescribed.

By evaluating these physical, cognitive, and sensory factors, clinicians can adapt Pilates-based exercises to meet individual needs while promoting safe, effective, and purposeful movement.

Individual Factor Considerations

From a cardiovascular perspective, clinicians must evaluate several factors to ensure safe engagement in Pilates-based exercises. Pain levels should be assessed to determine whether the client can participate comfortably and effectively. The client’s diagnosis also plays a role in determining appropriateness and guiding modifications. Motivation is another important consideration—some clients may be eager to try a Pilates-based approach, while others may prefer a more traditional therapeutic program.

Cognition, as discussed earlier in relation to client factors, is essential for understanding and following instructions and maintaining correct form throughout the exercises. Sensory processing abilities, previously covered, influence how clients perceive and respond to positional changes, movement, and tactile input. In line with OTPF motor function categories, motor control should be evaluated to determine the client’s ability to coordinate and execute intentional movements.

Baseline trunk control is another critical factor; Pilates-based interventions should be introduced when the client has an appropriate level of trunk stability to support safe and effective participation. Finally, joint stability must be assessed to ensure the involved joints are safe for the demands of the exercises, reducing the risk of injury while promoting optimal outcomes.

Task Analysis and Activity Breakdown

When implementing Pilates-based exercises therapeutically, approaching the process through a task analysis lens allows for a detailed activity breakdown and more targeted intervention. This means asking: What individual movements occur at each joint for the client to engage in the occupation or activity effectively?

For example, I might see a 27-year-old female client with right shoulder scapular dyskinesia. She works in consulting and often travels, spending long hours sitting at a desk or in an airplane’s bucket seat—positions that naturally encourage forward flexion. Her functional concern is difficulty donning and doffing a belt or an open-front jacket due to shoulder discomfort and pain.

My first step is to analyze the movements and joint positions involved in that activity. I observe her natural movement patterns—what is her pelvic position? How is her thoracic spine aligned? What is the position and mobility of her scapula, the movement at the elbow joint, and the mechanics further down the kinetic chain? Does she favor one side, compensating with her left over her right?

This task analysis identifies the specific joint motions and body regions involved, the alignment required, and where asymmetries or inefficiencies occur. That information then guides the selection and modification of Pilates-based exercises to address the root causes of dysfunction.

Given their influence on upper extremity function, this approach requires a strong understanding of anatomy and kinesiology, not only of the upper body but also of the trunk and lower body. Clinical judgment and reasoning are essential for making intentional choices that align with the client’s goals, physical capabilities, and movement needs.

Preparatory Measure

Many Pilates-based exercises can serve as effective preparatory measures before a client completes a functional task. As mentioned earlier, Pilates is often best used as an adjunct to traditional therapy approaches. For example, targeted Pilates movements can work on pelvic control before a client attempts bending, reaching, lifting, or carrying tasks. They can also be helpful before activities such as donning and doffing clothing or performing lower-body dressing, where coordinated trunk and pelvic control are essential.

From a preparatory perspective, these exercises aim to increase postural awareness and control, setting the client up for more effective occupational engagement. Pilates-based work can also target range of motion, build strength, and emphasize breath work. Breath work, in particular, can be valuable for anxious clients who are apprehensive about movement or hesitant to return to certain occupations. It calms the nervous system while creating an intentional mind–body connection.

Motor control is another key preparatory element. Pilates’ precise and deliberate movement patterns can help refine control over specific muscle groups, improving coordination for upcoming tasks. Balance work, closely tied to alignment in Pilates, is also a natural fit, helping clients stabilize their posture and body mechanics before they move into more dynamic or functional activities.

Areas of Occupation (OTPF)

Additional areas of occupation where Pilates-based exercises can serve as a valuable preparatory method or adjunct to traditional therapy include bathing, showering, dressing, functional and community mobility, sleep and rest, caring for others, health management and maintenance, meal preparation and cleanup, and leisure participation.

In each area, improved trunk control, abdominal engagement, scapular stabilization, and alignment of the head, neck, and trunk provide a stronger foundation for effective distal use. For example, better trunk stability can make it safer and easier to get in and out of a bathtub, to reach and wash during showering, or to manage clothing during dressing. The same principles apply when lifting a small child, picking up a grandchild, or performing kitchen tasks such as preparing meals, cleaning up, or loading and unloading a dishwasher.

Understanding how to properly engage the abdominals, pelvic floor, and pelvis—alongside maintaining optimal scapular control—directly influences the efficiency, safety, and quality of upper and lower extremity movements in these daily occupations.

Daily Activities

Additional daily activities where Pilates-based exercises can be highly beneficial include reaching overhead to style hair. Clinically, I’ve worked with clients who experienced upper extremity limitations and found that understanding how trunk and pelvic positioning influence overhead reach greatly improved their ability to perform this task.

Other examples include reaching behind the back for perineal care, bending and lifting during household chores like unloading the dishwasher, carrying and unloading groceries—where distal resistance demands strong trunk stability to prevent distal overuse—and donning or doffing shoes, jackets, or coats. Sitting at a desk or computer is another key area, linking to the randomized controlled trial on postural control and engagement in university students. This is particularly relevant given the significant shift to remote work, where prolonged sitting has become common.

Finally, caring for others—whether for children, older adults, or pets—often requires a combination of bending, lifting, reaching, and stabilizing, all of which benefit from improved trunk control, alignment, and proximal stability developed through Pilates-based exercise.

Let's Discuss

Let's discuss some different positions. In the upcoming slides, you’ll see images of me engaging in various Pilates-based movement patterns. If I were working with a client, my priority would be to educate them on the relevance of trunk stability to extremity use, specifically, how an engaged trunk, activated abdominals, engaged pelvic floor, and strong proximal control all contribute to effective distal movement.

I demonstrate an anterior pelvic tilt with thoracic extension and rotation in Figure 1.

Figure 4. Long sitting with trunk rotation.

From a cervical perspective, my head and neck remain aligned with the rest of my trunk. I’m using a Pilates ring, which can be held isometrically to target scapular control or used in a coordinated push–pull movement paired with intentional breath patterns. This type of exercise integrates multiple elements—trunk stability, breath work, and proximal control—to prepare the client for functional activities such as reaching or lifting groceries. While uncontrolled twisting would be discouraged in daily activities, the rotation here is deliberate and controlled to engage the obliques and address specific trunk and core needs.

For example, I once adapted this exercise for a client who was wheelchair-bound. We focused on scapular control and mobility while she remained seated. I used props to help promote a more anterior pelvic tilt, and she held the Pilates ring for gentle push–pull work. We began with light isometric holds, allowing her to feel the correct muscle engagement. Over time, she built the strength to press into the ring enough to alter its shape into an oval, and to pull in a way that elongated it horizontally. This provided both visual feedback and a built-in resistance component.

I selected the Pilates ring for her because it offered a more stable support base than an exercise band and allowed for clear visual cues. While the same movement could have been done with a band, free weight, or manual resistance, the ring was engaging and effective for her. She enjoyed the exercise, could see her progress visually, and gained measurable strength while working on foundational Pilates-based movement principles.

For more advanced clients, you can use the ring to work on lateral trunk flexion, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Tall kneeling with lateral trunk flexion.

You’re looking at pelvic position, ensuring it remains in an ideal, neutral alignment. You also assess the arm pushing into the ring from a scapular stability perspective, providing the shoulder blade maintains proper positioning and control throughout the movement. In addition, you’re monitoring the thoracic spine to ensure that as the client moves laterally, they aren’t compensating with thoracic flexion. Maintaining proper thoracic alignment begins with pelvic positioning, and both work together to support appropriate abdominal engagement. This integration of pelvic control, scapular stability, and thoracic alignment is essential for achieving the intended benefits of the exercise.

Another way for clients to work on scapular and proximal control is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Long sitting and forearm weight bearing.

Not every client will have this level of flexibility. I also performed this exercise with a client who was wheelchair-bound, using props to help promote a more neutral spine or anterior pelvic tilt if needed and encourage thoracic extension. I positioned the Pilates ring on a nearby height-adjustable table to achieve the optimal arm alignment I was aiming for. This setup allowed the client to engage in the exercise with proper positioning and control, making it safe and effective

Figure 7 shows another position using the Pilates ring.

Figure 7. Supine lying with knees flexed and arms upraised.

Clients with the necessary flexibility can perform this exercise in a long-sit position if appropriate, or they can flex at the knees for comfort and stability. This Pilates-based exercise targets pelvic stability and control, abdominal engagement, ribcage mobility, and pelvic floor activation. The Pilates ring is incorporated here to address scapular control and mobility further, while integrating head and neck flexion. For clients ready for an increased challenge, the exercise can be upgraded by extending the legs fully, as shown in Figure 8, increasing the demand for core stability and overall alignment.

Figure 8. Supine lying with lower extremities extended and arms straight over the pelvis.

Lastly, emphasis on the pelvis is key, as it directly relates to engaging and strengthening the pelvic musculature. This exercise can also target the lower body, promoting coordinated activation between the core and lower extremities. In this variation shown in Figure 9, the Pilates ring is positioned between the ankles, allowing for resistance-based engagement of the adductors while maintaining proper pelvic alignment and stability.

Figure 9. Sidelying with the Pilates ring between the ankles and side pushup.

However, if the goal is to work on scapular or shoulder stability, attention should be given to the hand resting and supporting the body on the mat, floor, or treatment table. In this position, there is a strong emphasis on maintaining proper trunk alignment, ensuring proximal stability through the arm, and providing support. These are truly total-body movements, requiring coordinated engagement of multiple regions, and they allow each aspect—trunk, scapula, shoulder, and core—to be addressed in an integrated manner.

Summary

Before moving into the summary, I want to reemphasize that Pilates-based exercises are designed to complement—not replace—traditional therapeutic approaches. These exercises should always be tailored to the client, with the ability to upgrade or downgrade movements based on their abilities, needs, and goals. The images I’ve shared demonstrate movement patterns for visual learning purposes—they are not depictions of clients.

In clinical practice, Pilates-based exercises can and should be adapted for each individual, considering their physical condition, therapeutic goals, and safety considerations. When used in a rehabilitative setting, these exercises can target specific client factors to promote activity engagement, participation in meaningful occupations, functional performance, and overall quality of life.

Adjunct to Traditional Therapeutic Approaches

Within our scope of practice, Pilates can be used as an adjunct to traditional therapy approaches, keeping in mind the elements of the OTPF.

Relation to Additional Areas of Practice

There is a strong relationship between Pilates-based exercises in a rehabilitative setting and other clinical practice areas. For example, these exercises align well with pelvic floor and pelvic health interventions. As noted earlier, research has demonstrated statistically significant improvements in the breast cancer population, and similar benefits may extend to other oncology groups when clinically appropriate.

Neurological populations, such as individuals with Parkinson’s disease, can also benefit. Improvements in upper limb function and bradykinesia were highlighted earlier. Musculoskeletal and repetitive strain conditions are another area of strong application. In my practice as a certified hand therapist, I have found Pilates-based interventions especially effective for chronic hand and upper extremity conditions, including repetitive stress injuries. Clients with hypermobility of the distal joints also benefit from improved trunk control, posture alignment, and proximal joint stability to support effective distal use. These approaches are also relevant for individuals with generalized or chronic pain.

Sensory processing disorders represent another niche where Pilates-based exercises may be beneficial. The rhythmic, controlled nature of Reformer movement, for example, can provide regulating sensory input. Adjustments such as adding a bolster or changing body positions (e.g., quadruped) can further tailor the experience for older clients with sensory processing needs.

Pilates-based interventions can address multiple conditions in the geriatric population, but exercises must be selected with caution for individuals with osteoporosis or spinal pathologies. Clinical judgment is essential to ensure movements are safe, appropriately modified, and aligned with each client’s functional goals.

Clinical Considerations

Occupational therapy practitioners must obtain additional training and certification through a reputable and recognized Pilates program before implementing Pilates-based exercises with clients in a clinical setting. This is essential because Pilates includes specific spinal movement considerations—such as flexion, extension, rotation, and pelvic positioning—that require a detailed understanding to ensure safety and effectiveness, particularly for clients with complex conditions.

Pilates and occupational therapy share notable historical parallels, especially in their early roots within rehabilitation during and after World War I. Both disciplines emphasize creativity, holistic care, and the integration of physical and mental well-being. As an occupational therapy practitioner and a certified Pilates instructor, I find these historical and philosophical connections deeply meaningful. They reinforce the value of Pilates as a complementary, client-centered therapeutic tool when applied with proper training and clinical judgment.

OT and Pilates

Pilates-based techniques can be a valuable adjunct to traditional therapeutic approaches, offering targeted benefits such as improved postural control, trunk stability, and movement efficiency. They can also be used as a preparatory method, priming clients for successful engagement in functional tasks by enhancing alignment, coordination, and breath awareness before those tasks are performed.

From a rehabilitation perspective, Pilates-based interventions have the potential to support functional recovery and elevate overall quality of life by integrating physical conditioning with mindful movement strategies.

As a final observation, I’ve noticed that while yoga's clinical and therapeutic application is well represented in the literature, Pilates research remains relatively limited. This represents a significant area for professional growth. Given Pilates’ emphasis on controlled, intentional movement and its adaptability to diverse client needs, there is excellent potential for occupational therapy practitioners to expand the evidence base. This is an exciting opportunity for those interested to contribute valuable insights, especially as Pilates and yoga are often compared, yet remain distinct in their focus and methodology.

Questions and Answers

What is the difference between Pilates and yoga?

While Pilates and yoga have similarities, one of the main differences lies in the type of exercises performed and the breath patterns used. Pilates incorporates breath in a particular way to support movement and stability, whereas yoga’s breath patterns vary depending on style and pose sequences.

What types of equipment can be used for Pilates-based exercises in rehabilitation?

A standard rehabilitation gym contains many props, such as weighted balls, free weights, exercise bands, and yoga blocks. These can assist with proper positioning, such as helping a client sit more upright. Wedges can also gradually move a client from supine to a more upright seated angle. Pilates-specific equipment, like the Pilates circle (ring), can benefit targeted muscle engagement and control.

Can Pilates-based exercises be modified for patients with CMC and wrist joint pain?

Yes, absolutely. Pilates exercises can be adapted to reduce stress on the distal joints. For example, using small weighted balls with a spherical grasp can help decrease strain on the CMC joint compared to holding a traditional free weight. A 1-pound weighted ball is often ideal for this purpose if available.

Are there any precautions to consider when using Pilates-based exercises?

Yes. Monitoring blood pressure and looking for adverse symptoms is essential, especially with position changes or certain movement patterns. Standard precautions should be followed for clients with high blood pressure, neurological conditions, or other relevant medical concerns.

References

See additional handout.

Citation

Dimopoulos, T. (2025). Therapeutic use of pilates for improved functional participation. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5827. Retrieved from https://OccupationalTherapy.com