Editor’s note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Treating Adolescents Diagnosed With Eating Disorders: An Occupational Therapy Approach, presented by Maddie Duzyk, OTR/L.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to identify ways to create a functional occupational profile for the EDO population.

- After this course, participants will be able to identify occupational therapy's unique role/skills in treating the EDO population in various settings.

- After this course, participants will be able to list evidence-based interventions for the EDO population that fall under OT's scope of practice.

About Me

- Spalding University, MSOT 2016-2018

- National Eating Disorder Association (NEDA) Walk, Louisville, KY

- Body Project, 2017

- Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, OT I 2018-present

- Eastern Kentucky University, OTD 2020-projected 2022

- Kentucky Eating Disorder Council, 2020

I want to tell you a little bit about me and how I got interested in this target population. At the age of 13, I was diagnosed with anorexia nervosa and a generalized anxiety disorder. It took me ten whole years to reach recovery.

Within that first year of recovery, I began Occupational Therapy School in Louisville, Kentucky, and Spalding University in 2016. My very first lecture reviewed the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework (OTPF), and I began relating my experience of recovering from my eating disorder to many key concepts in the framework. This is also what sparked my interest in occupational therapy's role in treating eating disorders. I wanted to give back to the community and advocate for those individuals still suffering from eating disorders.

I became a member of Louisville's National Eating Disorder Association Council, where I helped organize and advertise their annual National Eating Disorders Association (NEDA) Walk. In 2017, I also enrolled in Louisville's Body Project, which NEDA funds. At the end of the course, you are certified to work with teenagers in high school settings to instruct them about self-care, self-love, and body acceptance.

When I graduated from OT school in 2018, I was hired at Cincinnati Children's Hospital. I was looking forward to working with adolescents with mental illnesses but came to find out I hardly had any on my caseload. There were not a lot of referrals for adolescents with mental health in outpatient occupational therapy, especially for eating disorders. I began to research on my own time and noticed that there was limited information on the topic.

From there, I decided to create my path and enrolled in Eastern Kentucky's University OTD program, where my capstone is based on occupational therapy's role in treating eating disorders. This program has been beneficial for me because it's got me out of my comfort zone and has allowed me to try new things.

In December of 2020, I was elected as a council member for Kentucky's first Eating Disorder Council, and now, I am here presenting with you all today.

Outline

- Define subtypes and symptoms of eating disorders

- Discuss mental health disparities

- Review current EDO treatment

- Introduce OT’s role in treating EDO population

- Explore evidence-based interventions within OT scope of practice; case study

- Discuss limitations, future implications

- Provide summary/Q&A

The outline for this presentation includes subtypes and symptoms of eating disorders, mental health disparities, current eating disorder treatments, OT's role in treating the eating disorder population, evidence-based interventions within OT's scope of practice, a case study, and then concluding with limitations and future implications.

Eating Disorders

- “Eating disorders are behavioral conditions characterized by severe and persistent disturbance in eating behaviors and associated distressing thoughts and emotions” (American Psychiatric Association, 2021).

Eating disorders are behavioral conditions characterized by severe and persistent disturbance in eating behaviors and associated distressing thoughts and emotions. I like this definition because it refers to both disordered thoughts and behaviors.

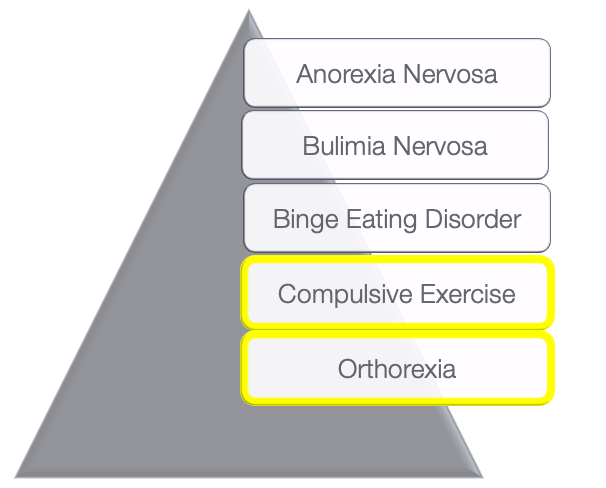

The three most common subgroups of eating disorders are anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Pyramid listing the five subgroups of eating disorders, with anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder being the top three.

These top three are thought to have the most strict criteria for eating disorders. However, over time, the DSM has introduced two new subgroups or subtypes of eating disorders to meet disordered behaviors that are not strict enough for the top three criteria.

Anorexia Nervosa (AN)

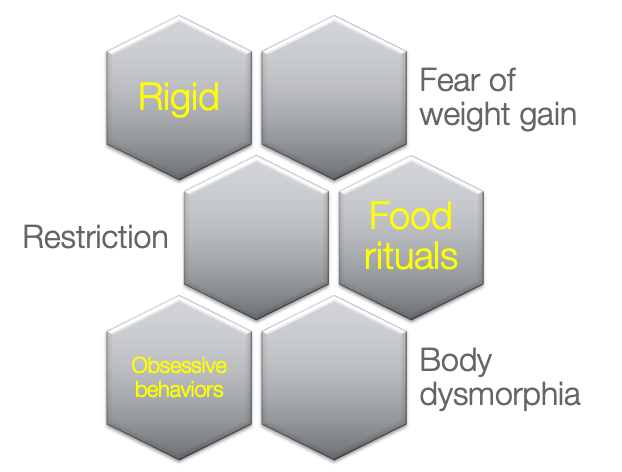

To meet the criteria for anorexia nervosa, the individual must have a significant loss of weight or be significantly underweight. Figure 2 highlights some of the other characteristics (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Graphic showing the characteristics of anorexia nervosa.

Those with anorexia have low body weight and significant fear of weight gain. There may be specific food rituals, restrictions on certain food groups, a rigid schedule, and body dysmorphia. Body dysmorphia is when the disorder tricks a person's brain, and they see their body as something utterly different from what it is. Instead of seeing a thin, underweight individual, they see a significant, overweight individual. Body dysmorphia continues to trigger rigid, dangerous behaviors.

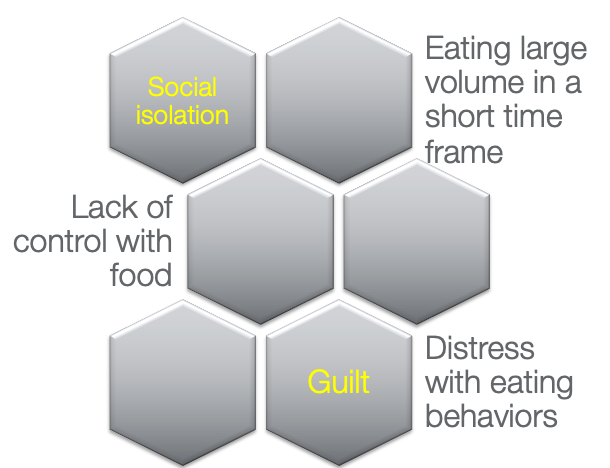

Binge Eating Disorder

To have a binge eating disorder diagnosis, an individual must consume a large volume of food in a short amount of time. This behavior causes extreme guilt and often social isolation because these individuals recognize that they have abnormal eating patterns, but they lack control with these foods (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Graphic showing the characteristics of binge eating disorder.

These individuals cannot appropriately attend to hunger cues or may not even have hunger cues, meaning they might overeat in one setting or graze throughout the day with multiple meals.

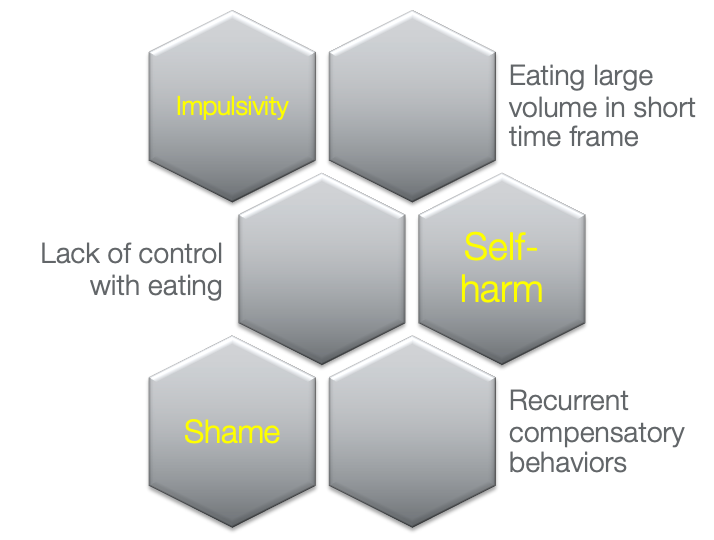

Bulimia Nervosa (BN)

For this diagnosis, an individual must present binge eating behaviors as defined in the previous slide, but these individuals also have recurrent compensatory behaviors (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Graphic showing the characteristics of bulimia nervosa.

After binge eating, the person has shame and guilt. As a response, the individual tries to compensate for this abnormal eating pattern using self-harm or punishment. This punishment can be purging, abusing laxatives, over-exercising, et cetera.

Compulsive Exercise

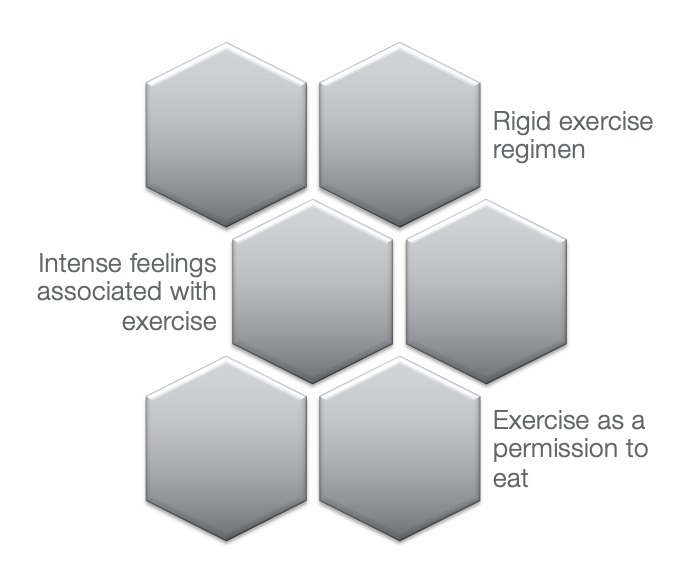

Some of these newer subtypes I wanted to introduce today are the ones I see most frequently with my population. The first is compulsive exercise (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Graphic showing the characteristics of compulsive exercise.

To meet these criteria, an individual must have a rigid exercise regimen, exercise as permission to eat, and have intense feelings, both positive and negative, associated with exercise. Here is an example. One of my clients had made this rigid rule that she must go to the gym and run five miles each morning for her to earn breakfast. One morning she woke up, and her mom could not take her to the gym due to a snowstorm. Due to her eating disorder, she did not allow herself to eat breakfast that day.

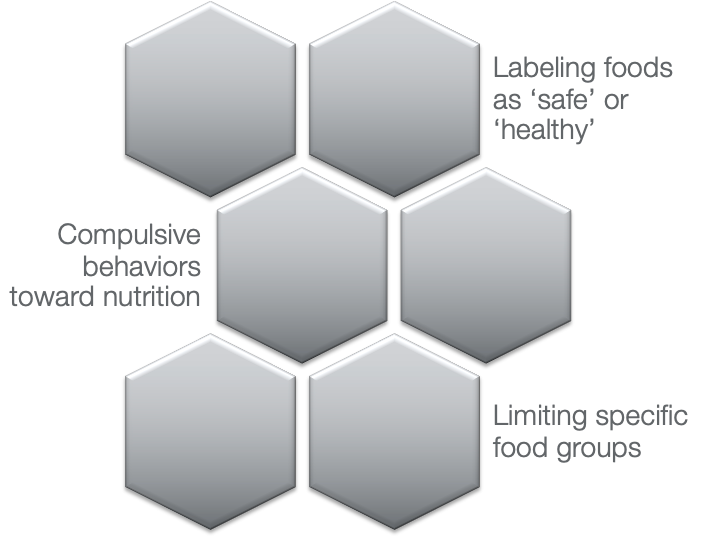

Orthorexia

Orthorexia is known as a healthy lifestyle obsession. These individuals label foods such as safe, healthy, cheat meals, et cetera (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Graphic showing the characteristics of orthorexia.

These clients tend to limit specific food groups, especially those with higher calories, and demonstrate compulsive behaviors toward nutrition. As another example, I have a client who has an abnormal rule around carbs. If he only eats two servings of carbs per day, he will not lose any muscle mass and be considered strong, muscular, and fit. He shared a day where he had extreme stress and anxiousness when he had three servings of carbs in one day. To compensate for this, he only had one serving of carbs the following day.

Eating Disorder Voice (EDV)

- EDV: a sub-self that voices values and beliefs on food, weight, body image, and exercise (Ling, N.C.Y. et al., 2021)

- It is imperative for an adolescent to recognize these entities are separate. The values and beliefs of the eating disorder are different than the values and beliefs of the adolescent (Berrett, 2018).

Regardless of the subtype, we often see the "eating disorder voice" as a common symptom of eating disorders. In 2021, Ling et al. defined the EDV as a sub-self that voices values and beliefs on food, weight, body image, and exercise. It is essential to establish that there is a person and then there is an eating disorder.

Amid the eating disorder, it is hard to separate these two entities, and often the eating disorder voice overpowers the person's values and beliefs. As occupational therapists, this is an excellent opportunity for us to help with the recovery process of helping these individuals recognize that their values and beliefs are significantly different than the values and beliefs of their eating disorders. When I was in recovery, I was able to identify a disordered thought as a disordered thought and not act out on that disordered behavior because my values and beliefs were able to override those impulses.

Why It Matters

- Anorexia nervosa has the second-highest mortality rate of any mental illness (Chesney et al., 2014 ).

- Individuals with eating disorders are at higher risk for suicidal attempts and engaging in risk behaviors (Pietsky et al., 2008).

- Individuals with eating disorders are more likely to have a co-occurring mental health disorder (Blinder et al., 2006).

Why does this all matter? Why are eating disorders such an important population to treat as occupational therapists? Chesney et al. (2014) shared that anorexia nervosa has the second-highest mortality rate of any mental illness, the first being drug abuse. Chesney suggested that every 52 minutes, an individual dies from anorexia nervosa complications.

In addition, individuals with eating disorders are at higher risk for suicidal attempts and engaging in risk behaviors (Pietsky et al., 2008).

Blinder et al., in 2006, conducted a study and found that 90% of individuals diagnosed with eating disorders also had a co-occurring mental health disorder. The most common co-occurring disease was depression, followed by anxiety. As we know, both depression and anxiety are very harmful, manipulative illnesses that can cause self-harm and suicide.

Adolescents

- “14.3 percent of adolescents engaged in disordered eating behaviors in an attempt to control their weight in 2009” (HealthyPeople, 2020).

Why target this specific age group? Healthy People (2020) identified a significant health disparity with 14.3% of adolescents engaging in disordered eating behaviors in an attempt to control their weight in 2009. This is not even addressing those adolescents with disordered thoughts that later turn into disordered behaviors.

Adolescents and Eating Disorders

- Adolescents are vulnerable to mental health disorders due to biological and social changes (Thapar et al., 2012).

- Low self-esteem, from being bullied by peers or being different than the norm, is considered a moderately-high risk factor of mental health disorders (McFarlane et al., 1994).

There are several reasons why eating disorders are highly prevalent in this age group. Thapar et al., in 2012, shared that adolescents are vulnerable to mental health disorders due to biological and social changes. We all remember being adolescents when our hormones were all over the place. We had limited control over our emotions and feelings. To cope, we sought out other adolescents and desired to fit in, be normal, and have a safe group.

However, those individuals who feel outside the norm, have low self-esteem, or are bullied by peers are considered moderately high-risk factors of mental health disorders. When adolescents feel like they are out of control or feel their peers do not accept them, they often turn to role models.

Who are role models for adolescents these days--the media, especially social media. They look at these figures and say, "Oh, if I was in shape," or, "If I looked like this," or, "I would be able to fit in," or, "My peers would accept me." This is such a slippery slope because while adolescents may not control their hormones or how their body is changing, they can control what they eat and how they exercise. This misguided control can become dangerous quickly.

Prevalence of EDOS in Adolescents

- Eating disorders affect 13% of females by the age of 20 (Stice et al., 2013).

- Adolescents have been labeled as a “high risk” group for eating disorders with higher rates of disordered eating at a young age (Smink et al., 2012).

- Often adolescents are not diagnosed because they do not perceive disordered eating behaviors to be unhealthy, making early intervention difficult (Walsh et al., 2000).

Eating disorders affect 13% of females by the age of 20. And, adolescents have been labeled as a high-risk group for eating disorders with higher rates of disordered eating at a young age. Walsh et al. in 2000 shared that often adolescents are not diagnosed because they do not perceive disordered behavior to be unhealthy, making early intervention difficult. Again, these adolescents are looking toward the media for role models. When their role models are skinny, skipping meals, or exercising to exhaustion, they are not going to consider their disordered thoughts or eating as concerning or abnormal. This is why I want to target this population specifically because if we can provide interventions that increase self-acceptance, body acceptance, and self-love early, we can have some excellent outcomes.

Adolescents, EDOs, and Disparities- Eating Disorders Do Not Discriminate

- Minorities

- Hispanic women are significantly less likely to seek treatment than non-Hispanic women (Sim, 2019).

- LGBTQ community (Goldhammer et al., 2019)

- Body acceptance

- Males (Limbers et al., 2018)

- Often undiagnosed because signs/symptoms are different than females.

I will get on my soapbox for a second and say that eating disorders do not discriminate. This stereotype is that eating disorders are in thin, beautiful, young, Caucasian, financially stable, young females. So, when minorities have disordered thoughts or behaviors but do not fit into this stereotype, they do not think they are sick or need help. Family and friends may also feel that there is no issue. And, just because someone has a healthy body weight does not mean that they have a healthy relationship with food. Sim in 2019 shared that Hispanic women are significantly less likely to seek treatment than non-Hispanic women.

In the LGBTQ community, Goldhammer et al. in 2019 shared that body acceptance is challenging for this population. Trying to meet the expectations of being thin or fit or looking a certain way can significantly trigger this particular community.

Limbers et al. in 2018 shared that within a national sample through the United States, 5.5% of adolescent males participated in disordered behaviors when it comes to eating, and 30% of adolescent males wish that their bodies looked different. Males are often undiagnosed because signs and symptoms are different than females. Typically, males are not trying to get skinny but rather more muscular. Thus, they do not always recognize that their behaviors are abnormal because they do not fit into that stereotype of the thin, Caucasian female.

Eating Disorders and Treatment

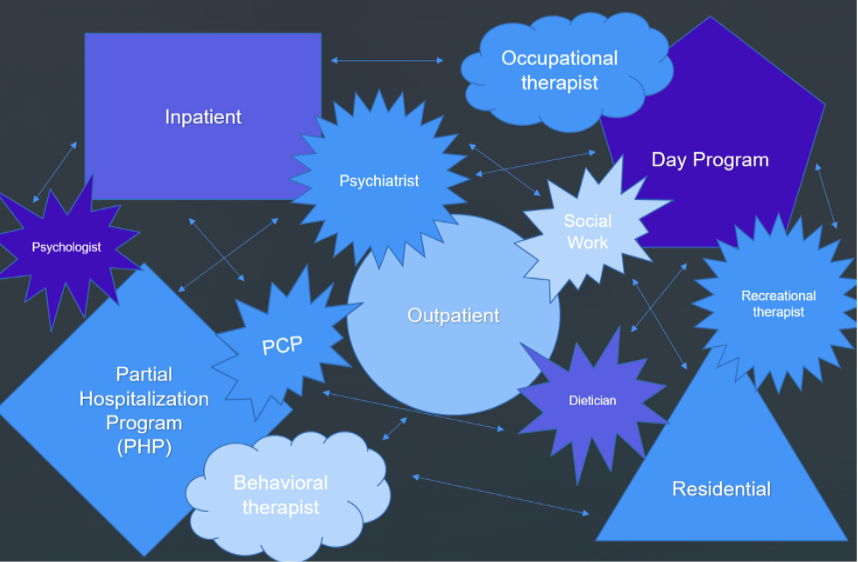

When an adolescent child is diagnosed with an eating disorder, the family is usually overwhelmed. I hope you get a sense of that by looking at this diagram (Figure 8) that I made, as there is no algorithm for these families to follow or a true pathway to success.

Figure 8. Diagram showing different treatment options for EDO.

There are many different types of settings and other providers, and no clear-cut direction of which way is the right way. This allows the disorder to become a chronic illness for many individuals.

I want to briefly discuss the different settings that you typically see eating disorder patients. One is inpatient for acute care, where they usually stay for two to three weeks. The goal in this setting is health and weight restoration before they go on to more long-term treatment.

Residential programs are where the adolescent lives away from family and friends 24/7 to live and breathe recovery. Adolescents tend to be in this program for months to even a year.

There are partial hospitalization and day programs during which the adolescent will spend 8-10 hours of the day in one-on-one and group sessions and work on assignments. Then, they go home at night with their family.

Outpatient is not as common for eating disorders, but I think it is essential. In outpatient, treatment intensity is significantly decreased, and the frequency is typically only one time a week for an hour. This is going to be the most applicable to an adolescent's natural setting.

Current Treatment for Adolescents Diagnosed With Eating Disorders

- “Family-based therapy remains the only well-established treatment (Level 1) for adolescents 18 years and younger with anorexia nervosa” (Lock, 2015).

- “No Level 1 (Well Established) or Level 2 (Probably Efficacious) treatments were identified for adolescents with bulimia nervosa” (Lock, 2015).

In 2015, Lock shared that family-based therapy remains the only well-established treatment for adolescents 18 years and younger with anorexia nervosa. However, there are no Level 1 or Level 2 treatments identified for adolescents with bulimia nervosa. In preparation for this presentation, I looked for any new evidence and could not find anything for bulimia nervosa or binge eating disorders. The best treatment for these at this time is a family-based therapy approach.

Family-based Treatment (FBT): The Maudsley Approach

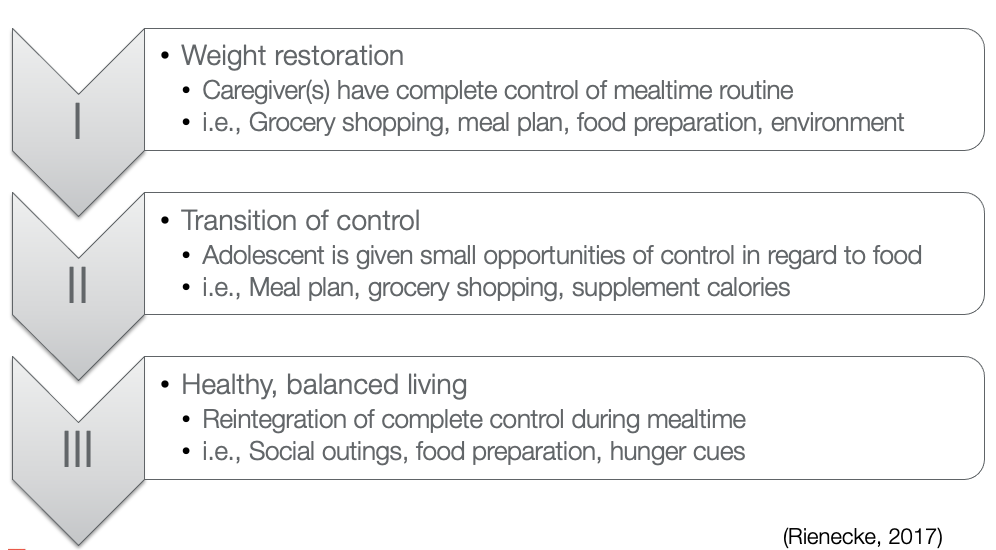

Family-based treatment is also known as The Maudsley Approach, as seen in Figure 9.

Figure 9. Overview of The Maudsley Approach (click here to enlarge the image).

There are three different steps throughout this process. Number one is weight restoration. Caregivers have complete control of the mealtime routine. They go grocery shopping, plan the meals, schedule the meals, prepare the food, and supervise meals to ensure the adolescent is not participating in any disordered behaviors.

Once this is established, the adolescent will move on to Level 2. This is a transition of control. Adolescents are given small opportunities of control like going to the grocery store with a caregiver, picking out one or two meals they would like to have for that week, and they are given a choice to have their larger snack in the morning or the afternoon.

Then, Level 3 is healthy, balanced living. Adolescents reintegrate into mealtime routines with complete control. Adolescents might go to a social outing without a caregiver or prepare their food for lunch or snack time.

The end goal is to have a healthy relationship with eating. For this to happen, the adolescent has to respond to hunger cues appropriately and have a good variety and volume of food.

Disparities in Current Treatment

- Only 1 in 4 individuals remain in remission after treatment (Smink et al., 2012).

- Community reintegration (Preyde et al., 2017)

- Social isolation (Givetash et al., 2017)

- Financial burden (Deloitte, 2020)

- Denial of funding (NEDA, 2021)

There are significant disparities and concerns with our current treatment. Smink et al. in 2012 shared that only one in four individuals remain in remission after treatment. Eating disorders are chronic illnesses, which is a big reason why the mortality rate is so high.

What are the gaps in our current treatment? There are several, and I am going to go over a few.

The first is community reintegration. Preyde et al. (2017) stated that the most stressful or triggering events for individuals in recovery or remission are going back to daily routines and roles. When someone is in treatment, their responsibility is recovery and getting healthy. As soon as these adolescents are reintegrated back into the community, not only do they need to focus on continuing to heal and continuing to fight these eating disorder voices, but they also have schoolwork, homework, household chores, relationships, sports, band, and the list goes on and on. It becomes very overwhelming for these adolescents, and they feel like they are sinking, and the eating disorder voices take advantage of that. Adolescents think that the eating disorder behaviors are familiar and comfortable, and that is how remission happens.

Social isolation is another area, and I will focus on this in a couple of slides.

Financial burden and denial of funding are other areas. Often insurances will not fund all of the treatment for eating disorders. There are several reasons why, but the main ones are if the individual has a healthy BMI and vital signs. They are healthy and have no concerns, so insurance cannot justify paying for treatment. Another reason for denial is if the adolescent continues to be readmitted into the same program. This sends a red flag to insurances. "Well, they've already gone through this program and had negative outcomes because they're already back, so we can't justify funding for this treatment again." There are significant financial burdens for these families. In 2020, Deloitte found that $23.5 billion comes out of families' pockets per year to pay for treatment for eating disorders. Consequently, most of these adolescents do not get to complete their program, and sometimes they are pulled halfway through their program and have to wait until families earn or save up more money. This incompletion of the program completely throws off the healing process.

OT Scope of Practice

Now, looking at eating disorders with an occupational therapy scope of practice, let's talk about all occupations that can cause huge stressors and burdens to these adolescents.

Activities of Daily Living

Adolescents with anorexia nervosa and body dysmorphia may go through their entire closet to find something to wear to school in the morning as they do not like what they see in the mirror. How will they get out of the door into the classroom if they cannot even get dressed? What about bathing? Bathing is such a sensitive, vulnerable activity for these eating disorder clients. With body dysmorphia and disordered thoughts, an individual may be stressed to bathe as it is a reminder that their body is changing because they are starting to eat food. Bathing is a time when adolescents may begin to body check again. Body checking is a compulsive behavior with rigid rules when it comes to eating disorders. For instance, "If I can fit my fingers around my wrist, I'm skinny enough." Or, "If I can feel so many rib bones in my rib cage, then I'm skinny enough." Again, these are things that would typically happen during the morning routine when showering and dressing. If the adolescent cannot even do that, then we are setting them up for failure for the rest of the day.

Instrumental Activities of Daily Living

I briefly mentioned that many adolescents are responsible for preparing their lunch for school or their afternoon snacks. They also tend to go shopping with peers. If an individual is recovering from an eating disorder, this can be a very tricky activity. They may be in a dressing room with fluorescent lights and a full body-length mirror. Their friends may be talking about what sizes they are wearing or body shaming themselves. It can be a dangerous activity that can escalate quickly.

School

Let's say the individual can get dressed, showered, and make it to school. Can they sustain attention to achieve academically? Many of my clients are so rigid that they have difficulty attending to their classes due to these eating disorder thoughts. This is very stressful as many have high expectations for their grades. For example, they may be thinking, "How many calories was breakfast today?" or "How many laps am I going to have to run to make up for those calories?" instead of focusing on the lecture. Before they know it, they have missed the majority of the lecture and will fail the quiz. This stress will then trigger them to start seeking control, and the eating disorder takes over. In the cafeteria, heaven help us if a peer or classmate makes a comment like, "Oh my gosh! I can't believe you're eating all of that," or, "Where does that all go?" Their day will be ruined. These are some examples of opportunities where occupational therapists can step in to help.

Leisure

I am going to end on leisure. I had a client who, at her initial evaluation, talked about an exercise community. She stated that they were very supportive and pushed her only to have one cheat meal a day. Later in her treatment, she spontaneously said to me, "Yeah, I don't think I'm going back to that community anymore." When I asked why, she said, "I realized that that was valued by my eating disorder and not by me as a person." I thought it was so insightful of her to connect the volition of leisure activity and categorize it as a volition of the eating disorder. We have an excellent opportunity to guide these adolescents to make that connection.

Interventions

So interventions, as occupational therapists, what can we do to support these adolescents?

An Occupational Therapy Approach: Sensory

- Sensory processing (CCHMC, 2019)

- Pool filter

- Over responsive

- Under responsive

- Seeking

- Pool filter

- EDO (Riva & Dakanalis, 2018)

- Sensory modulation

As a pediatric therapist, I instantly think of sensory processing. I introduce sensory processing to my adolescents and families by using an analogy of a pool filter. A pool filter has the function of keeping the good things in and the bad stuff out of the pool so that you can go swimming and have fun. We all have our pool filter in our head that helps us filter out environmental stimuli that we need to be aware of and other stimuli that we can ignore. For example, I am currently ignoring the bright fluorescent light over my head, how the seat feels on my tailbone, and the conversation happening outside in the hall so that my sensory focus is toward this computer screen. What if the pool filter was not filtering enough? The pool is going to overflow, and there is going to be over-responsive sensory processing.

An example of this is a client with anorexia nervosa may have tactile over responsiveness. They may be very sensitive to clothes, how clothes feel, stretchy clothes, constricting clothes, et cetera. This tactile sensation can cause stress and anxiety, or what I call sensory-induced anxiety. I will go into that more in the next slide.

When a pool filter filters out too much, what happens? Well, the pool drains, and there is nothing to swim in. This often happens with under-responsive sensory processing. An individual with binge eating disorder may be under-responsive to internal cues of hunger and fullness.

A filter may not be working how it needs to be, and the body starts seeking particular sensory input to compensate for that broken or dysregulated filter. This process is known as seeking. In bulimia nervosa, we seek input or compensating with abnormal behaviors such as purging, laxative abuse, or cutting.

There are many different sensory processing challenges within this population. Riva and Dekanalis, in 2018, conducted a study that supported the hypothesis individuals working on sensory regulation were less likely to act on eating disorder thoughts.

An Occupational Therapy Approach: Sensory Intervention (Khoury et al., 2018)

- Interoception (Mahler, 2019)

- Interventions

- Recognize body cues

- Word bank

- Yoga (Katzman et al., 2012)

- Mindfulness

- Recognize body cues

Here are some sensory intervention approaches. Suppose a person's interoception or internal body cues are under-responsive, as, in bulimia, our role as occupational therapists might be to retrain them to recognize those internal responses. We can start with something easy, like having the individual clap their hands together. "Did that feel hard or soft?" "Was that loud, or was that quiet?" We start creating a word bank of terminology that helps them become more in tune with their body both outside and inside. Then, once they get good with this word bank and terminology use, we put it into practice.

Katzman et al. in 2012 shared that yoga is an excellent intervention for adolescents with eating disorders. Yoga focuses not only on mindfulness but also on internal body cues and that word bank of terminology. When we have them in a downward dog position, we can say, "Think about your stomach right now. Does it feel empty? Does it feel full?" You are getting that conversation going to bring back that awareness.

An Occupation-based Approach: Emotional Regulation

- Correlation between emotional dysregulation and symptoms of anxiety and depression (Young et al., 2019)

- Sensory-induced anxiety (Dillon, n.d.)

- Common environments that trigger sensory overload

- School cafeteria

- Birthday parties

- Restaurants

- Grocery store

- Holiday celebrations

I like to put sensory and emotional regulation together because I think they feed off of one another. There are correlations between emotional regulation and symptoms of anxiety and depression suggested by Young et al. in 2018 and Dillon (n.d.). Dillon defines this as sensory-induced anxiety. When an adolescent is overwhelmed by sensory input, the autonomic nervous response turns on, triggering a fight or flight response. If this happens, disordered behaviors and thoughts are soon to follow.

I also want you to think about how overwhelming it is sensory-wise in different community environments like the school cafeteria, birthday parties, restaurants, the grocery store, and holiday gatherings. All of these environments or events are surrounded by food. Not only do you have food, but you also have loud sounds, crowds, and bright lights.

An Occupational Therapy Approach: Emotional Regulation Interventions

- Preparatory sensory activity (Dillon, n.d.)

- Preparatory dialectical behavior therapy (Reilly et al., 2020)

- Naming the eating disorder

- Separate eating disorder from adolescent (Berrett, 2018)

- Experience

- Telehealth

As occupational therapists, what can we do? We can provide some preparatory sensory activities to help regulate or bring that autonomic nervous response to a calm state. This may include exploring different fidgets, auditory stimuli, chewing gum, sucking on a peppermint, deep pressure, joint compressions, et cetera. I like to put individuals in a safe and controlled environment and try out these different coping skills to see what works best for them. I also feel like we can do this a lot with telehealth now as it is more accessible. "Let's schedule something during snack or family mealtime." Or, "Let's schedule something when you typically pack your lunch for the next day to see what coping skills we can use that help you get through those triggering environments."

I will jump back up to Reilly et al. in 2020 to talk about preparatory dialectical behavior therapy. The therapist may notice some disordered behaviors in a controlled setting or see the adolescent start to shut down. They can at the moment say, "What values or beliefs are you thinking of right now?" "Do you think that's from your eating disorder, or do you think you believe that?" And, "Why do you believe that?"

An Occupational Therapy Approach: Social Skills and Interventions

- Social isolation (Givetash et al., 2017)

- Occupation-based interventions have been shown to improve self-esteem and decrease social withdraw (Lazaro et al., 2011).

- Engagement in social gatherings

- Role-play, modeling

As I said, social isolation is a common reason why adolescents relapse. This goes back to my first couple of slides. Adolescents want to fit in and do not want to be different or stand out. When adolescents are gone for an extended time for treatment, they often want to avoid questions like, "Where were you?" "What happened to you?" "You've gained so much weight." However, isolation is probably the last thing they need because they are stuck with their eating disorder thoughts. They do not have a support group to help them reintegrate back into the community.

Lazaro et al. in 2011 shared that occupation-based interventions have been shown to improve self-esteem and decrease social withdrawal. As therapists, it is our responsibility to engage or excite these individuals to participate in social gatherings or social events. We can do that by role-playing and modeling tricky situations. For example, I had an adolescent gone for the second half of the school year for treatment. She was approached by a classmate in the community that said, "Oh, we all thought you were dead." This upset the client, as you can imagine, and made her anxious about returning to school. We talked about different ways she could answer those questions at school and the answers that gave her the most self-confidence and ability to answer that question without leading to tearfulness or stress. By the end of our session, she was proud of her response and was almost looking forward to school because she had a sarcastic response that fit her personality.

An Occupational Therapy Approach: Meaningful Occupations

- Rediscover self-identified roles, values, and beliefs separate from the EDO

(Dark & Carter, 2020; AOTA, 2020)

Returning to my first day of occupational therapy school and learning about the OT Practice Framework, as therapists, our goal is to lead these individuals to participate and be satisfied with their meaningful occupations. What a great opportunity we have to help an adolescent recovering from an eating disorder rediscover self-identified roles, values, and beliefs that are entirely separate from their eating disorder.

Case Study

- Anna was recently discharged from an inpatient program; she was admitted into an acute program for 3 weeks for anorexia nervosa and co-morbidity of anxiety.

Anna came to me as an outpatient. I saw her one time a week for 55/60 minutes.

- Occupational profile (AOTA, 2020)

- “I am…” exercise

- Identified roles

- Meaningful routine, rituals

- Lifestyle

- Emotional regulation

- Sensory

- Biomedical

- Outcome measures: Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (Coelho et al., 2020)

- Self-identified goals

- Attending social events

- Reintegrating back into sports

- Applying makeup

- Self-perceived satisfaction/performance

- Self-identified goals

- Episodic care (recommended 1-2 x weekly visits)

- Preparatory sensory activity

- Companion snack

- Participation in meaningful occupation

- COPM, re-test

The first day I met Anna, we did an occupational profile. I always like to start the occupational profile by asking them to fill in the blanks. I usually model my own by saying, "I am a wife, a dog mom, and a cross-stitching queen." This usually gets some sort of response, whether an eye roll or a laugh. Anna responded to this with, "I am an athlete." She also identified herself as a sister, a friend, and a student.

I then like to take them through a typical day to see their everyday roles and responsibilities. Anna was a pretty busy individual. She had practices two times a day, followed by schoolwork and homework. She was a straight-A student. She also had several household chores when she got home from school. The weekends were reserved for sports games and hanging out with friends.

I then like to take the client through emotional regulation. "What's triggering for you? What makes the eating disorders louder than normal?" She identified when she felt out of control and gave examples like when she got a bad grade on a test or performed poorly in sports. She also identified that her typical disordered behaviors were running excessively or starting to count calories.

I also like to give a sensory questionnaire to see how their filter is working. We learned something that Anna did not even realize. Anna was very over-responsive to loud noises. As a response, she sought out tactile input through body checking. I thought if I could get her desensitized to auditory stimuli, this might also affect body checking and the eating disorder.

The Canadian Occupational Performance Measure, or the COPM, is another tool I use. It helps with their buy-in to the process because it allows them to understand that they are in control of therapy. It lets them know that we will work on what is most important and meaningful to them. I have them self-rate satisfaction and performance of those goals using a Likert scale of 1 to 10. I have them fill that out on the first appointment, and then we reassess on the last meeting of our 12-week program.

A typical treatment session includes a preparatory sensory activity to get them at a nice calm baseline, and then I trigger them a little bit with a companion snack. A companion snack is where you eat a snack together to work through those coping skills to see what is working and what is not. I like to end with meaningful occupations to reinforce the values and beliefs of that person.

For Anna, her meaningful occupation was playing her sport and knowing when to stop based on when those disordered thoughts became present. Another was applying makeup and being able to look at herself in the mirror without having any triggers.

Considerations When Working With Adolescents

- Body shaming

- Diet talk

- Disordered behaviors

- Social media

- Disordered eating

Healthy weight ≠ healthy lifestyle

Here are some considerations for working with adolescents. I always try to be mindful that a healthy weight is not equal a healthy lifestyle or a healthy relationship with food. I want to be the best role model that I can be for my clients, so I avoid any diet talk or body shaming, either about myself or some influencer on social media or celebrity. When I have my companion snack with that individual, I do not model disordered behaviors and eat everything on my plate because I want to be their role model.

Limitations (Creed, 2020)

- Green light

- Socially engaged

- Functional mealtime routines

- Healthy vital signs

- Participation in activities

- Yellow light

- Social withdrawal

- Body checking or other disordered behaviors

- Fluctuating vital signs

- Mood change, anxious

- Red light

- Poor attendance

- Significant vital sign changes

- Disinterested, disengaged

We are going to trigger these individuals and push some buttons during interventions. Their eating disorder voices might get a little bit louder. I like to use Creed's stoplight model. Green means go, so if you see these behaviors, you are good to go and can continue with the intervention. Yellow is you might need to downgrade things a little bit and not push as hard that day. Red means we need to discontinue that intervention and redirect or end for the day.

Using an interdisciplinary model, reach out to the psychologist, physician, and dietician to make sure that everybody is on the same page and that you are all seeing the same behaviors to make sure that we keep the adolescent as safe as possible.

Future Implications

- “If you seek to be understood, then dedicate your life to understanding others.” –Sue Monk Kidd.

Figure 10 is a picture of my tattoo, the eating disorder symbol with a cross on top. I always thought that going wedding dress shopping was going to be a massive trigger for me. However, due to my recovery, it was a wonderful experience.

Figure 10. The author shows her tattoo of an eating disorder symbol with a cross on top in her wedding dress.

We have a long way to go. OTs have a lot of awareness to help others, but we need to figure it all out regarding insurance, billing, and advocating for our treatment with physicians and dieticians. I am going to end with Sue Monk Kidd's quote, "If you seek to be understood, then dedicate your life to understanding others."

Questions and Answers

What about avoidant restrictive food intake disorder? How is this related to anorexia? How would you approach someone with ARFID?

This is one of those subtypes where the individual does not meet the strict criteria for an anorexia nervosa diagnosis. ARFID is right below that. I would manage it very similar to handling an adolescent coming in with an anorexia nervosis diagnosis.

Do you follow up with your clients?

I like to reach out at one month and then at three months just to check in to see if they need anything, a consultative visit, et cetera.

How would you intervene on behalf of a client with an eating disorder when a family dysfunction that hyper focuses on being skinny as being beautiful?

I think this is one of the benefits of outpatient because the family members can be a part of those interventions, and it is a complex topic to share. When I am that role model, I redirect beauty comments to self-acceptance and body acceptance so that the family members start to catch on. I am not calling them out, but I am modeling how to respond appropriately to body image and self-acceptance comments.

Citation

Duzyk, M. (2021). Treating adolescents diagnosed with eating disorders: An occupational therapy approach. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5473. Retrieved from http://OccupationalTherapy.com