Introduction

I am going to begin with a question. Have you noticed an increase in referrals or concerns for fine motor skills for your K-4 and K-5 students over the past five years? As an SLP, I have definitely seen an increase in referrals. It is not that more children are struggling with speaking clearly, but the concerns are with academic readiness primarily in the ability to interact appropriately, follow teacher directions, and the ability to appropriately control their emotions. I have done this same workshop for speech-language pathologists, school psychologists, as well as national conferences for pediatricians and developmental pediatricians in other related fields, and they are seeing the same concerns. As a matter of fact, every time I do a live workshop, I get a lot of head nodding throughout the audience. And, at the end of one of these I did with developmental pediatricians, I received the biggest compliment I think I have ever received. A developmental pediatrician came up to me afterward and said, "Wow! This really made me think." If nothing else, that is what I hope to do today. I want you to think about how exposure to excessive amounts of stimulation through technology can have a negative impact on the skill development necessary for academic readiness.

Again, my name is Angie Neal, and I am a school-based Speech-Language Pathologist. I am extremely honored and excited to have been invited to share this with occupational therapists because you all are my people. In a school setting, OTs are my go-to. You are the only other people who really have the perspective of how to straddle both the educational and medical settings, and how that impacts our perspective across many different areas.

For our learning objectives, we are going to review the negative impact of excessive screen time and how it affects how kids relate to the world socially. We are also going to review key data and emerging research on the topic. Lastly, we are going to talk about strategies to share with families. This is the most important thing.

As I begin talking about the current research and the impact of technology on development, there is one thing I really want you to keep in mind. Human Development is cumulative. In other words, each step builds upon the next. And so, when one step is delayed or disturbed, there can be a snowball effect on the development of other skills.

Statement of the Problem

- For every 30 minutes of screen time, there is a 49% increased risk of expressive speech delay (Birkin, 2017).

- Children who spend more than 2 hours a day on screens scored lower on language and thinking tests (National Institute of Health, 2018).

- The use of mobile devices in children has risen from 5 minutes a day in 2011 to 48 minutes per day in 2017 (Common Sense Media, 2017).

- Almost 40% of children under the age of two use mobile media (Common Sense Media, 2017).

We are going to start with a few key statistics. In 2011, 38% of children, age eight and under, used tablets and smartphones. In 2013, it was up to 72%. We are now in 2020. Do you think that number is higher or lower? My guess is much, much higher. In 2018, one-in-four children under the age of six had a smartphone. What is a five-year-old doing with a 400 or $700 smartphone? Also, about a third of all screen time used by children is on a mobile device, meaning it is used across many locations and not in a fixed location. This is more important than you might think when it comes to building language and learning how to interact with the world around you. The use of mobile devices by children has risen from five minutes a day in 2011 to 48 minutes a day in 2017. Again, do you think that number is higher or lower now in 2020?

Now, where things get really precarious is in the studies on children age two and under. Almost 40% of children under the age of two use mobile media, and that is a 2017 statistic. Recent studies are revealing that kids and babies, under the age of two, are spending more than double the time in front of screens than they did in the 1990s. Here is the kicker with this, especially for that age group. It is not until around the age of 18 months that a baby's brain has even developed to the point where the symbols on a screen even begin to represent their equivalent in the real world. Also, between birth and age three, all learning takes place in a social context, through relationships, and the younger they are the truer this is. Children under the age of two are wired to learn and remember things via experiences and imitation. However, what they found is that children watching screens imitate 50% fewer actions than those children who engage in live three-dimensional interactions. Meaning, it is actually easier to learn from humans, than it is to learn from screens. In addition, children 12 months and younger are not even able to follow the changing scenes on a screen or the program's dialogue because they have not learned the words, context, or syntax yet.

The question we have to ask is, "What is keeping them engaged?" Well, it is the exciting colors, the quick scene changes, the music and sounds, and the over-exaggerated characters. Just as an example, Baby Einstein had a video called, "A Day at the Farm." In the "Day at the Farm," there are seven scene changes in one 20 second section. There was roughly one scene change every three seconds. So what is actually keeping them engaged is not what they are seeing, but it is the constant stimulation. And then, when they go to an actual farm, it can be quite boring for them because there are no sheep popping up out of the corner or a cow being super exaggerated with a close-up. You actually have to walk from here to way over there to see the horse. And, chances are that horse is not doing a beautiful slow-motion run, but rather it is probably just sitting there eating.

In other words, these videos are conditioning the mind to a reality that does not exist. And, as a result, for every 30 minutes of screen time, there is a 49% increased risk of expressive speech delay. This statistic comes from a 2017 study out of Canada by Dr. Catherine Birken. This was the first study that reported a link between handheld devices and expressive language delays. Now, there are over 200 peer-reviewed studies that point to screen time correlating to increased ADHD, addiction to screens, increased aggression, depression, anxiety, and even psychosis. The National Institute of Health is conducting a current $300 billion study using functional MRIs to examine the changes in brain structure among children who use smartphones and other screen devices. What they are finding in the first batch of results is that kids who spend more than two hours a day on screens scored lower on language and thinking tests, and kids who spend seven hours per day on electronic devices show premature thinning of the cortex.

AAP Recommendations

- Less than two hours per day for children ages 5-18

- No more than one hour a day for children age 2-5

- None for children younger than 18 months of age

Excessive screen time can impinge on children’s ability to develop optimally; it is recommended that pediatricians and health care practitioners guide parents on appropriate amounts of screen exposure and discuss potential consequences of excessive screen use. (Madigan et al., JAMA Pediatrics, 2019)

What is the recommended amount of time per day that kids should be spending on technology? The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends less than two hours per day for children aged five to 18, no more than one hour a day for children aged two to five, and none for children younger than 18 months. Keep in mind that this is per day and consider how quickly this adds up. For example, you have to include if a child is at school and they have 30 minutes of circle time on a promethium board or they have 30 minutes of iPad centers or Chromebook time. You also have to include if they watch videos on the back headrest 30 minutes to school and 30 minutes home from school. That is two hours right there. Now, as we are recording this workshop, I have been working from home for a few weeks due to COVID-19. Trust me when I say the timing of this workshop on-screen time is not lost on me. Now, we are using screens for interactive and educational purposes as a necessity. What I am talking about today is not that. I am not talking about the interactive and active use of screens. I am talking about the mindless entertainment type of screen time for children and adults.

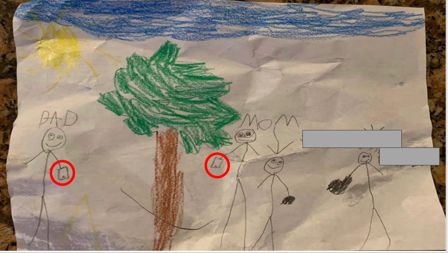

Let's take a look at this from a child's perspective. Figure 1 is a picture drawn by a friend's kindergartner. She posted it on Facebook as it was a wake-up call for her.

Figure 1. Drawing from a kindergartner.

The red circles are phones and this child sees them as an extension of their mom and dad. This was a huge wake-up call for her. When I do in-person workshops and have more time, there is a YouTube video that I really like to show because it is especially eye-opening. It is called Cute Baby Crying for Phone. It is a baby sitting on an activity mat holding a phone and smiling while strumming his fingers across the screen, but when the phone is taken away, the baby cries. It is not a type of cry or body movement that you typically see. It is spastic and dramatic. When they give them the phone back, the baby smiles and strums the phone again. It is really hard to watch.

Increases in Incidence and Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorders

- Nationally, 1 in 59 children had a diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder by the age of 8 (2014). This is a 15% increase over 2012.

- In the 2000-2001 school year, the number of children age 3-21 receiving SPED for Autism was 93,000. In 2015, it was 617,000.

- It's not that technology causes ASD, but disproportionate exposure during critical periods can negatively impact the development of social communication, social-emotional skills, and behavior.

While correlation is not causation, it does lead me to now talk about a frightening trend. We have seen is a huge increase in the incidence and prevalence of autism, classifications in both the school setting and the medical setting. Nationally, one of 59 children had a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder in 2018. In the year 2000, it was one in 150. As of today, April 2020, the CDC is now reporting that number is now one in 54. In the 2000-2001 school year, the number of children, three to 21, who were getting special education for autism was 93,000, but in 2015 it was 617,000.

I am not at all here to say that technology causes autism. What I want to get you to become curious about is what happens when there is a disproportionate exposure during critical periods of development that can negatively impact the development of certain areas that we use to determine the presence or absence of autism. These areas are social communication, including social reciprocity, social-emotional skills, including Theory of Mind, and the behaviors that are related to emotional regulation and self-regulation.

I want you to consider what happens when children have less social interaction opportunities and when there are obstacles that impede healthy brain development. What happens is it looks very much like a child who struggles socially and presents very similarly as a child on the spectrum. Additionally, thinking about the three prongs for autism, I want you to think about the statement regarding atypical restricted repetitive patterns of interest in behavior, including sensory sensitivities. I also want to point out the word atypical (that is the word I want you to hone in on). Think about an eight-year-old boy who is really into Minecraft. This is not necessarily atypical. However, an eight-year-old boy who is really into manhole covers or garbage trucks is deemed atypical. So, while they may seem really interested in video games, we have to tease out whether or not it is an atypical interest versus an actual addiction that I am going to talk more about later. And, when it comes to developing this ability to engage in socially inappropriate interactions, it is really a chicken and the eggs kind of a thing. When children do not get practice with social interaction with peers, they are not getting opportunities to exercise their emotional regulation with peers. In turn, the peers are the ones who provide them with feedback to know whether these behaviors were appropriate or not. The less they regulate these emotions, because they lack the practice, the more they stand out to their peers and have difficulty with establishing relationships.

What is interesting to note is that countries that have not experienced a digital revolution, they have not seen the exponential rise in autism that affects children in rich countries. Many families have access to five to 10 screens within one household between TVs, smartphones, laptops, iPads, video games, and screens built into a car. We also do not want to just pin this on the kids. This is also impacted by parents attending to screens instead of interacting with their children. Think about all of the missed opportunities for language, conversation, play, and development as you ride down the road, sit at the dinner table, walk through the grocery store, or as you wait in line at Disney. These are common times that we see kids and parents on their devices. And when parents are distracted by their phone, it impacts the development of joint attention with the child and their emotional connectedness, as well as conversational ability, which we know is critically important to language development. We are going to talk about that later.

Parents will say, "They are playing educational games. That's okay, right?" Let's explore that. There is certainly something to be said for that. However, in one example, research is showing us that children aged three to five, whose parents "read" to them through electronic books, had lower reading comprehension as compared to physical books. This is because all of the bells and whistles distract from the story. If they are reading Curious George digitally, as an example, every time you push the man with the yellow hat, he takes his hat on and off. Or, every time you push Curious George, he goes up and down the tree. This causes the child to be distracted from the accumulated meaning of the story. Keep in mind that young children learn word meaning through social interaction with real objects. Sharing a book with a child is significantly different than having a book read to them. Sharing is the only setting where parents typically talk about things outside of the everyday routine. In other words, it is a chance to talk about space, Africa, dragons, or castles because books are not constrained to the here and now. Subsequently, this contributes to the knowledge gap in exposure to concepts that are outside of our everyday routines which impacts vocabulary.

Educational Apps

- There are over 700,000 educational apps… but do they actually help children educationally?

- The Waldorf School in Silicon Valley, whose population is made up primarily children whose parents are tech executives, does not allow any tech despite being located in the heart of technology innovation

- Both Steve Jobs and Bill Gates are reported to have raised their children “tech-free”

There are more than 700,000 educational apps out there. Eighty percent or more of them are targeted specifically towards young children. Many claim to help children learn to read, but most do not. They may teach a child how to recognize letters, but that does not mean they can blend sounds to form words. They may teach your child to count to 10, but that does not mean they can show you a group of 10 blocks. In short, the apps are just glorified flashcards. They do not add depth of knowledge, and they do not help a child to generalize knowledge, which is necessary to build a strong foundation for learning. When it comes to teaching children, nothing is more important, valuable, or more effective than human interaction.

Let's take a moment to think about the people who invented all of the technology. Most of the tech executives in Silicon Valley do not even allow their children near certain devices. There is actually a private school in the Bay Area where 75% of the parents are tech executives. This school does not allow any tech in the school. This means no iPads, promethium boards, whiteboards, or Chromebooks. Steve Jobs is famous for saying that his own children were not allowed to use iPads. Many Silicon Valley nannies have to sign no technology agreements stating they will not be on a device or allow the children to be on a device while in their care.

Think about the video game and app designers do not only hire video game designers but also hire neuro-biologists and neuro-scientists who hook people up to electrodes and other sensors while testing the app. And if it does not produce blood pressure increases, skin responses, and other biological responses that they are looking for within a few minutes of playing it, they go back and tweak it until it does. Using hyperstimulating digital content to engage students creates a vicious and addictive cycle. The more the child is stimulated, the more that child needs to keep getting stimulated in order to hold their attention. The big question we have to ask is whether there is any evidence that supports that these educational apps actually produce better educational outcomes. Do they do what they say they purport to do?

Dopamine

- Dopamine plays a major role in reward-motivated behavior and it serves, to some extent, as part of a survival function.

- However, technology/games/apps provide a short cut to this rewards process, floods us with dopamine, and serves NO biological function.

- Evolutionarily speaking – humans haven’t yet adapted to this excessive amount of dopamine.

Now, let's talk more specifically about the parts of the brain that are negatively impacted by excessive screen time during critical periods of development. First, we are going to talk about dopamine. Dopamine plays a major role in reward-motivated behavior, and it serves in survival function. For example, after some effort and delay in shopping and cooking food, eventually, there is the reward of the food. This reward serves a survival function. It is a reward that incentivizes us to have biological functions such as eating. However, technology, games, and apps provide a shortcut to this rewards process as it floods the brain with dopamine without serving any biological function. Consider how many "dopamine hits" kids are getting per game or per swipe and multiply that by the length of time they are on a device per day. This is a flood of dopamine that little bodies have not adapted to. Again, dopamine, being what it is, makes us crave more and more. This is not dissimilar to any other kind of addiction.

Evolutionarily speaking, we have not adapted to all of this dopamine. When a child gets used to this immediate stimuli response, they start to prefer these type of interactions. In other words, they start to prefer immediate gratification and responses instead of real-world connections. As I do workshops all over the United States, I hear again and again from therapists, who are working with nonverbal or limited verbal students that they have to put a child through a four to six-week detox from technology before beginning therapy. Then, they can have the child start to interact with the technology as a tool and not as a toy.

We also have whole generations that are being trained to have shorter attention spans than books require. Books take cognitive patience and learning to read takes perseverance, while apps do not. When the app gets too hard, they just turn it off or change the game. A 2013 study from the University of Oregon found that attention span persistence did not just impact learning to read and reading development, but it also predicts their math and reading scores at the age of 21.

Frontal Lobe Development

- Frontal lobe damage results in difficulties with many tasks, including…

- problem-solving

- verbal and non-verbal abilities

- memory

- initiation

- judgment

- impulse control

- social behavior

- facial expression

- difficulty in interpreting feedback from the environment

- risk-taking

The frontal lobes are considered our emotional control center, like the Disney Pixar movie "Inside Out," with the characters of anger, fear, disgust, joy, and sadness. It is the home to our personality, and frontal lobe damage results in a lot of difficulty in many different areas. I am going to highlight just a few. The first area is memory or what has occurred in the past. These are those teachable moments that remind us not to do the same thing again that got us in trouble last time. It also impacts initiation, slowing down enough to initiate, the use of conversational filters, and when to use appropriate conversational approaches. When not in place, one may interrupt frequently or insist only on talking about one's interests. Also, this includes impulse control. Without this, one may want to blurt out anything and everything, but impulse control and restraint are what keeps those things in check and helps us to interact socially and appropriately. Additionally, in order to respond to social behavior and social cues, it requires us to have the ability to attend to them long enough to notice and process what the signals were.

Executive function is also part of frontal lobe development as well. Executive function is important to social skills and communication. For example, have you ever had to carry on a conversation with someone you do not like about a topic you do not particularly want to talk about or care about? In order to do that task, you have to smile and nod the whole time you are talking and plan what to say in order to get out of there as fast as you can. In doing so, you need to inhibit that eye roll and head shaking that you really want to do instead. That is an executive function.

The development in the frontal lobe starts between six and 12 months when babies become more mobile and verbal and when they start to interact with the world and the people around them. It matures in spurts with new functions being added until the frontal lobe reaches full maturity around the late 20s. However, when we give kids nearly unlimited access to devices and they have not fully developed the frontal lobe, this is where we need to really give the term addiction some consideration.

What is addiction? Addiction is something you enjoy in the short term that undermines your wellbeing in the long term. And, you continue to do it in a compulsive way. Addiction to screens or anything else has similar brain areas involved. This involves dopamine, adrenaline, and so on which makes us crave more and more. However, the difference between addiction in children versus adults is that children do not have a developed frontal lobe that is used for impulse control and decision making. In other words, they have not developed the part of the brain that tells them to put on the brakes. "This isn't good for me, and this is keeping me from doing things that I should be doing instead." There is a double whammy. This type of hyperstimulation actually stunts the growth of the frontal cortex as we are seeing from the NIH study. Continual hyperstimulation creates more of a dopamine response to craving it and less of the good decision-making abilities to step away from it.

Hypothalamic Pituitary Adrenal Axis

- “Fight or flight”

- Dr. Dimitri Christakis conducted a study in 2012 looking at the impact of overstimulation (similar to stimulation from technology) during the early developmental period demonstrated...

- Increased risk-taking and increased frenetic activity

- Difficulty distinguishing a new object out of a choice of two with 75% more time spent on novel objects (i.e. learning) by those who were not exposed to overstimulation

This area is related to the fight or flight response or the adrenaline (adrenal) rush that we feel. Our blood pressure goes up, our pupils constrict, and our palms get sweaty. This fight or flight adrenaline rush is typical and necessary, but it is supposed to be a short term of our bodies. For example, a dog chases you, your heart races, your adrenaline surges, and then you calm down as soon as the threat goes away. However, when kids are engaged in similar adrenaline, dopamine enhancing activities for hours, there can be a consequence to that. It leads to aggression, impulsivity, hypervigilance, and hyperactivity. Thus, when they are not first in line, have to use a blue game piece, or they are not winning at whatever game, they have an immediate physical reaction. They can demonstrate pushing, jumping, screaming, crying, running, or what we would otherwise call a fight or flight response.

Keep in mind, reading, completing math problems, and other school activities require a certain amount of patience, practice, and perseverance. These are things that are not full of bells and whistles. You do not get a reward every time you get a word or math fact correct. Reading is an amazing collaboration between the visual, auditory, linguistic, and prefrontal cortex, and pretty much every lobe of the cerebrum is involved. However, kids who are in fight or flight mode and who struggle with self-regulation and crave hyperarousal can have issues with learning to read. There is a 2012 study that looked at the impact of overstimulation, similar to technology, during the early developmental period. They exposed 10-day-old mice to six hours of lights and sounds mimicking what technology looks like to children. They did this for 42 days, which is essentially the entire childhood of the mouse. When they tested them, they found was there was a significant increase in hyperactivity, as well as risk-taking. Whereas, the control group of mice spent 75% more time on novel objects, meaning new earning. The mouse exposed to "technology" struggled to even distinguish a new object, out of a choice of two.

Myelin

- Humans are born with a lifetime supply of brain cells (neurons). At birth, a newborn’s brain weighs 33 grams. In the first two years, it triples in size – not due to the development of more brain cells, but the development of synapses. These synapses become faster and more efficient because of the myelin covering them.

- Both overstimulation and under-stimulation can damage myelin

- A 2012 study by the Chinese Academy of Sciences discovered that those with internet addictions had myelin abnormalities in the areas of the brain related to executive function, decision making, and emotional regulation.

A newborn's brain is 33 grams. In the first two years of life, it triples in size, and this is unparalleled growth to any other time. This is why they sleep all the time. By the age of three, the brain is about 85% complete. We are born with a lifetime of brain cells, also known as neurons, but that is not what grows. The connections and synapses are what continue to develop. We start with 2,500 synapses at birth, and it increases to 15,000 synapses by the age of three. Now, over time, these connections or synapses become more pruned and refined, which makes what we do more efficient and faster. The synapses are formed based on early and meaningful experiences, not just repetitive experiences like we see on apps. Scientists have discovered that it takes approximately 400 repetitions to create a new synapse in the brain unless it is done through play. In which case, it only takes between 10 and 20 repetitions.

Myelin is what allows the synapses to become faster and more efficient as it is a fatty coating that forms a sheath around the synapse. This is similar to a plastic coating on a power cord and forms a protective coating around the myriad of cords within the power cord. However, the brain cells that produce cholesterol for myelination are very easily damaged by things like head trauma, stress, toxins, certain drugs, as well as the wrong amount of stimulation. When I explain this to parents, I usually use this example. Myelin is like a sled on a snowy hill. The first time we try to learn something or try to go down the hill, it is slow and effortful as we make our way through the snow. But with every subsequent trip down the hill, we have created these grooves in the snow which makes the trip easier and faster. When infants or young children are exposed to the complexities of language, those neuropathways for language, and any other thing we are trying to learn, are myelinated. Metaphorically, they make those tracks in the snow. This makes everything that we do faster and easier to learn. When we provide too much stimulation or the wrong kind of stimulation, the ability to "grow" a brain in such a way that it makes it efficient becomes difficult. It makes it difficult to learn new things or engage in play with other people. This overstimulation stops the synapses from growing and creating that special covering that makes learning easy.

Play Skills

- Interacting with other humans through play provides opportunities to experience emotional and social situations with other humans, practice controlling negative emotions, and learning how to solve conflicts and negotiate with others.

- Gayler and Evans (2001) found that the level of involvement in pretend play by preschoolers with their parents was positively linked with their capacity for emotional regulation because of the guidance and coaching parents offer during play.

Play seems like the last thing we need to be thinking about in terms of academic readiness until you have children who cannot play or they are not on the same level of play as the other kids in the classroom. Kids learn through play, and it helps them to interact in groups. They learn how to lead, share, problem-solve, and resolve conflicts. Gayler and Evans (2001) found that the level of involvement in pretend play by preschoolers with their parents was positively linked with their capacity for emotional regulation because of the guidance and the coaching that parents offered during play. When you compare normal play with virtual reality, it might appear boring or frustrating. You may have to share your stuff or learn to take turns with someone who also wants to be the fireman. Your friends may not want to do everything you want to do at the exact moment that you want to do it. Seriously, how can Candyland compete with an electronic game? I have seen this a lot in K-4. Kids just starting school do not have basic play skills, and this is for both my students who come in with complex developmental diagnoses and those who do not. Here is an example of a little girl with a diagnosis of autism. She recently moved from out of state and her grandmother was her primary caregiver. Her grandmother readily admitted that she did not know what to do with her so she let her stay on the iPad all day when she was at home. As a second-grader, she had to learn the most basic level of play, or onlooker play, before I could get her to engage in or benefit from my actual therapy targets. What is interesting and sad is how much progress she made while she was in school and then the slide backward when she was gone for long breaks. This makes me very worried about her right now.

Theory of Mind

- Development of Theory of Mind is negatively impacted when humans don’t have the opportunity to develop this skill through interactions with other humans by looking at facial expressions, interpreting body language, engaging in conversation that reveals what others may be thinking.

- To think about what another person may be thinking you have to spend time interacting with people.

Theory of Mind is understanding that other people have perspectives that are different from your own. It is a primary area of difficulty for children who are on the autism spectrum. The development of Theory of Mind is negatively impacted when they do not have the opportunity to develop these skills through interacting with actual people, by looking at facial expressions, interpreting body language, and so on. You cannot develop Theory of Mind, or the ability to think about what other people are thinking, with a screen. Deficits in Theory of Mind result in difficulties such as understanding that different people or places have different expectations, understanding nonverbal language, such as facial expressions and gestures, being unaware that their behavior affects how others think and feel, and also the inability to identify future self and how I act at this moment can have an impact on things that happen later. They cannot see themselves as a future self or as another self. Theory of Mind development begins early in infants, like three to 18 months, when they begin to follow directions like pointing or a gesture or attending to facial features. This is all based on interaction with people.

There are layers to the development of the Theory of Mind. It starts with pre-first order that develops around the age of three. This is where they think about themselves. How do I feel? What do I think? They use simple emotions such as happy, mad, sad, as well as thirsty, hungry, dirty, and sleepy. The first order develops around the age of four to five years. This is where I think about what another person is thinking including characters from a book. The second order develops around the age of six to eight. This is where I think about what another person is thinking about a different person, as well as, the development of more advanced emotional concepts. These are concepts like proud, jealous, worried. They also start to learn that you can feel one way at first, and that emotion can change. Keep that in mind as we talk about emotional regulation. The second order is also where they start to be able to lie or detect a lie in someone else. I love to tell the story of a little first-grade friend that I have. We had a fire alarm go off and our dismissal is at 2:45. So, at 2:20, the fire alarm went off. If you are in a school you would never have a fire drill at 2:20 pm. Everybody filed outside, fire trucks came, and everybody was looking around. About that time, I see my little friend come running out. She said, "I pulled the fire alarm! I was just curious." He did not have second order Theory of Mind because he could not lie. This is a question I always ask in my evaluation whether or not the student tells lies because it reveals a lot about Theory of Mind. The third order is where they begin to understand figurative language where words say one thing but they mean another. It is also where metacognition comes in and they are able to start to monitor their own comprehension in conversation. It is also where they start to understand sarcasm as it relates to emotional regulation. They start to be able to hide emotions. They may not cry even though you said something they do not like or will not hit you even though you made me mad.

Emotional and Self-Regulation

- Emotional regulation is the ability to move appropriately across various emotional states.

- Self-Regulation provides us with the capacity to do so.

- When children don’t get practice interacting socially with other children, they have fewer opportunities to exercise emotional regulation with peers who provide them with feedback to know whether their behavior was appropriate or not. The less they regulate their emotions (because they lack the practice), the more they stand out to peers and have difficulty establishing relationships with them.

This leads us to talk about emotional regulation. Emotional regulation is the ability to move appropriately across various emotional states, and self-regulation is what provides us the capacity to do that. Emotional regulation supports positive interaction with peers because to have a friend, a friend has to see you as stable. And when you are emotionally stable, friends want to spend time with you which builds your opportunities for social interactions. I have a little buddy that is a constant roller coaster of emotion. Once within a 10-minute span of time, he went into full flight mode and ran out of the room and then the building. There was aggression, anger, regret, and significant emotional lability with tears. Then, he went back immediately to happy compliance. Within 10 minutes, all of this happened. How was he ready to learn, follow directions, do multiplication, and read stories about Abraham Lincoln during that roller coaster?

Going back to the digital piece, digital interactions do not teach kids how to self regulate or to calm themselves. They also do not teach them how to persevere or pay attention to things that are not full of bells and whistles. Again at the Developmental Pediatric Conference, I had several pediatricians tell me that at well-baby appointments where they are getting their shots it is not at all uncommon that instead of the parent holding and calming, they are giving them the phone instead.

Self-regulation and the ability to learn how to calm is not learned through distraction. It is learned through interaction and modeling. Screen time is also predictable and within their control at a time when kids need to be learning how to deal with situations that are out of control. Trust me, in K-4 and K-5, it is no longer their world, but rather it is their teacher's world and they have to figure out how to live in it. At about the age of two, most toddlers have learned some self-regulation skills, such as being able to wait a short period of time for something they want, paying attention when someone is talking to them, or even persevering through something that is new and challenging. This becomes an issue if they have spent their childhood just swiping right when things get too hard.

Now, I should not have to mention the negative impact on emotional regulation as it relates to sleep. Kids may stay up for hours and unregulated in the amount of time they are in front of the screen. When we do not have adequate sleep, we are all a little less in control of ourselves and our emotions.

Anxiety is one of the primary emotions our little friends feel. Why is that? Let me pull this all together. When you have deficits in Theory of Mind, you cannot think about your future self, and that is what anxiety is. What might happen in the future? Depression is the opposite. Depression is worrying about what has already happened or already happened in the past. The opposite of anxiety is not calm, it is trust. Often, we just tell kids to calm down. When does this ever work? Instead, we need to reduce anxiety and build trust in the people, the environment, and the routines around them. We need to take them through baby steps in order to build that trust. We build trust through communication and experiences with people. This leads us to talk about the speech and language piece, my bread and butter.

Speech and Language

- “30 Million Word Gap”

- Conversations between children and parents are the most influential contributors to vocabulary before school entry (Hart & Risley, 1995)

- The amount of talk children had been exposed to through the age of three predicted their language skills and school test scores at age nine and ten (Hart & Risley, 1995)

The Hart and Risley study (1995) was the one that led to the description of the 30 Million Word Gap for children of low socioeconomic status, but we are seeing similar results now. However, it is not due to socio-economic status, but rather it comes from being part of a low-level language environment. Conversations between children and parents are the most influential contributors to vocabulary before school entry. This has a profound implication long term because the amount of talk that kids hear through the age of three predicts their language skills and school test scores at the age of nine and 10. Children also do not learn words by having each one explicitly taught. They learn them indirectly through daily conversation, by being read to, or by reading on their own in upper elementary. There is a negative impact when these activities do not take place at critical stages of development.

Remember, we are born wired to learn from interacting with people through the beautiful dance of facial expressions, tone of voice, body language, and lots and lots of words. The impact of a language-rich environment, or lack of, has been well documented. When kids have not engaged in conversation, often they do not alert to the words they do not know and they do not listen as carefully when they are read to. Later on, they are not good readers on their own. They also struggle with complex grammar and sentence structure, as we read in books. It is important to consider exposure to interactions with actual humans during your assessments.

A few of my favorite questions that I like to ask in the assessment are these.

- Is the child breaking social rules or expectations they do not like, do not agree with, or cannot stop themselves from breaking? Are they breaking social rules and expectations they do not know? This is a big one because most of our buddies on the spectrum tend to be ardent rule followers, meaning once they learn the social rule, not only would they not commit that same mistake again, but they will police everyone else and report anyone who does break that rule. So, if they continue to break the rule or expectation, it is not likely due to a lack of knowledge, but something else.

- What is the pervasiveness of the difficulties? Are the behaviors specific to certain topics, certain subjects, certain times of day, certain settings, certain people, and certain locations? Social communication difficulties are not limited to school, the art room, or the gym. Social communication deficits are because of a lack of social knowledge, no matter the context, place, or topic.

- When they learn a social rule or expectation, do they continue to break it? If so, why?

- What opportunities has the child to be exposed to or learn these social rules or expectations?

- Are the behaviors we are seeing cruel in nature? People on the spectrum are not cruel and there is no intent to harm behind their behaviors. Actually, people on the spectrum are capable of great depths of empathy. They just struggle with perspective taking because of the deficits in Theory of Mind, as well as, the nonverbal skills necessary to recognize when someone is struggling. In addition to the verbal skills of knowing how to respond, empathy prevents you from hurting another person. Therefore, an absence of empathy makes hurting another person possible. Now, empathy is feeling with people. Empathy drives a connection with people. A lack of connection in empathy impacts trust. We often think of growing into adulthood as becoming independent and autonomous, but in fact, it is more related to becoming someone that other people can depend on. This includes trusting that you are going to show up to your job and do the job you are being paid to do in an efficient and effective manner. The way to develop that dependability is to develop trust. The way we develop trust is by spending small moments with other people, talking to them, sharing stories, and demonstrating care for them.

A magical tool, the Gutenberg Printing Press, was developed in the year 1440. It was the impetus for a major shift in violence. It increased our empathy for other people and our ability to feel with other people. With the mass production of books came widespread literacy and the ability to inhabit the mind of people, unlike ourselves. While this may sound trite, it was actually a seismic innovation for people in the pre-industrial age who did not see, hear, or interact with people outside of their own village. Reading can be a simulation of various social experiences you might otherwise never be exposed to. And, the same social cognitive processes we employ in real-world social comprehension are found similarly in reading. Repeated simulation of this kind leads to a honing of these social empathic processes, which in turn can be applied to other contexts outside of reading. In addition, readers of fiction learn social information from books by acquiring knowledge about human psychology. Interestingly, readers of fiction tend to have better abilities of empathy and Theory of Mind, but that is not what most of our buddies on the spectrum like to read typically.

Here is a drastic example where empathy was not demonstrated. In September 2019, in New York, there was a 16-year-old boy who was stabbed and 50 to 70 other teenagers filmed him dying instead of helping and comforting him. They were more concerned with being the first to post it. I do not think there is a better example of the impact on technology and empathy than that.

Literacy

- Reading digitally vs. reading paper books

- For children, 3rd grade and up negative impacts (of digital vs paper books) were found in the ability to sequence details, understand the plot, and make inferences

- Why would comprehension be impacted in children age 3 to 5 when reading books presented digitally?

We spoke earlier about reading comprehension and what that means. We are led to believe that technology is necessary for learning, but somehow we have survived a millennia without it. Before smart gadgets, the Pyramids of Giza were built, there were maps of the galaxy, modern-day airplanes flew, and we sent a man to the moon. Yes, these things make our tasks easier and faster, but we have to first teach kids the basic underlying principles. Am I saying Chromebooks are bad? No. I am saying we must teach the basic skills to mastery first.

Many of us read digitally with Kindles. But remember, we are reading as mature proficient readers, not novice readers. Also, mature readers have developed deep comprehension strategies, and they, myself included, know when we skim something and need to go back. I think there is something important there. Novice readers have not developed these skills at all. Consider the purpose of reading in school as compared to reading for pleasure on your Kindle. You do not browse a social studies book. You are trying to gain knowledge from the text. We also do physical things in the book. We highlight, flag, and make notes in the margins to bring our attention to certain facts.

The research shows us that there is a negative impact on sequencing details, understanding plot, or even making inferences with digital books.

Red Flags

- There's a reason to be concerned when children...

- are not able to balance screen time with time spent in human interactions

- demonstrate extreme irritability or aggression when screens are removed

- view their world from the lens of a specific game/app/video OR if they rush through any required tasks in order to return to that world

- exhibit poor sleep patterns

- struggle to have the same amount of attention, problem-solving skills, and stamina for activities that are not technology related

- show symptoms of impaired social interactions with peers

- have difficulty controlling their emotions

- need technology to calm down

- consistently request technology over other free time and play activities

- When these concerns occur, there is a need to reset a hyper-aroused nervous system. To accomplish this, the brain often needs four to six weeks of time spent without any screens.

There is a reason to be concerned when children are not able to balance screen time with time spent with actual human interactions. There is a reason to be concerned when they demonstrate extreme irritability or aggression when the screens are removed. There is also a reason to be concerned when they view the world through the lens of a specific game, app, or video. They tend to rush any required task in order to return to a digital world. They also need technology to calm down. Yet, how many times are we giving iPad time as a reward or as a distraction? There is also a concern when they are consistently requesting technology over other free time and play activities. When this occurs, there is a need to reset this hyper-aroused nervous system. They need four to six weeks spent without any screens. When I talk to parents, I tell them, that with the exception of books which are free from the library, they have everything they need to raise a happy, healthy child. Reading to your child, getting outside, and playing all cost nothing, and they are technology-free. That is what a digital diet is.

Digital Diets

- The term “digital diet” is meant to imply that what we put in our brain is what contributes to healthy brain development

- Help parents understand why there is a need for screen time limits

- Share the AAP guidelines

- Establish “tech-free” times and locations

- Replacement activities (a.k.a. what we used to do BEFORE we had omnipresent screens)

A digital diet is meant simply to imply that what we put in our brain contributes to healthy brain development, and what it needs to develop appropriate skills. Make no mistake, most of what is on screens are nothing more than mental junk food. I like to ask parents if they would give their two-year-old a steady diet of Oreos and Cheetos. Yet, when children stay engaged for long periods of time each day on passive digital activities, that is the equivalent of mental junk food, which also is bad for their development.

To start, we need parents to truly understand why this is important. We have discussed this at length already. In the handouts, there is a parent-friendly version of all of this. We also need to talk to parents about important concepts such as technology is a tool and not a toy and screens are not meant to be free babysitting. While it is free, kids are going to pay for it via the impact on their brain development, social development, and their academic readiness.

We also need to talk about expectations and AAP guidelines. We also need to talk about creating tech-free times and locations. My favorites are in the car and at the dinner table. Those are some of those sacred times as they are the best times to engage in conversation. We also need to limit screens before bedtime due to the impact on sleep. I also like to recommend that they use apps that monitor or restrict the amount of screen time. There are apps like Forest, Moment, and Freedom. There are much more available. I also recommend to go in and change the phone settings to grayscale.

The whole second page of the handout is all replacement activities, which is also known as the things we used to do before we had technology. There are so many other options like reading books, having a game night, and playdates, even just your parents (during COVID19). In these playdates, work on compromise, complementing, and basic social manners. It is also important to delay gratification as we are seeing more and more children that have difficulty with that. Teach them to do monotonous mundane chores like folding the laundry, cleaning their room, hanging up clothes, setting the table, unpacking groceries, emptying the dishwasher, putting toys in the box, making their bed, and get them engaged in activities. Golf, especially adaptive golf, is one of my personal favorites, There are rules and social politeness that you have to have.

Tell your stories. Stories are how we connect and make connections with other people. I like to recommend to parents that they get a sticky note and write, "I remember." This will stimulate conversation.

Summary

I have included many references. If I had to recommend one, it would be Dr. Mary Ellen Wolfe's book, "Reader, Come Home," especially if you are interested in the literacy connection.

Here is my email, [email protected]. Feel free to connect with me and thanks for your time.

Questions and Answers

What about the use of large screen TV?

When you are talking about screen time, is it needs to be engaging and interactive. For example, when using a promethium board to show a video in a special-ed classroom, is it engaging? Let's say it is about letters, sounds, numbers, or colors. If the teacher is not interacting with the kids while they are watching it or then transferring that and generalizing what they just saw in the video to an actual application of that knowledge, that is a problem.

Online human interaction through live video conferencing. Is this an issue?

There are many examples of this: FaceTime, Zoom, or Skype. Yes, you should completely engage in doing that. For example, you can use these to talk to family around the world. This is engaging and interactive. I am not aware of a limit on how much they should be able to interact online that way.

Are highly interactive apps part of screen time limits? Is this more of a judgment call?

I think that is a great question, especially from an OT perspective. An example given here is drawing apps. I would say that you have to consider when they are drawing. Are they drawing just with the pointer finger or is it better for them to be drawing on paper using a tripod grasp or something else?

Is it okay to let a 21-month-old earn four to five minutes screen time for using the potty?

My opinion is that there are other things you can use as a reward for going potty. My personal children earned a Skittle or something like that. I would not recommend it. I am just a little hesitant about that.

How much time is recommended to play outside to balance the screen time?

I would say you need more time, and it does not even have to be outside. I am ok with inside, outside, and upside down. When it comes to the recommended amount of time, I would stick to what is recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics, and anything after that is fair game.

What about shows like Sesame Street, which my child is watching?

I love Sesame Street. Sesame Street and it has some amazing things right now, especially for self-regulation with Cookie Monster. I get the work from home situation currently. It is not lost on me at all that we are in crisis teaching mode right now. Again, I would try to keep that balance. Is it appropriate for a child to be watching Sesame Street for three or four hours a day? I would say probably not. Generalize what they are learning from that. If the number of the day is three, incorporate it into an activity where they have to count three in order to get three goldfish crackers.

Do I consider video games or apps which require some form of participation interactive?

No. I will give you a good example of that. I think there is a game called World of Warcraft. While it is certainly interactive, but it is not something that is helping to foster social engagement, even if they are on the headphones with another child. That is not something that is fostering good social communication.

Have you seen specific video games or applications being associated with specific characteristics?

No, I have not seen specific ones as it relates to ADHD and sensory seeking behavior. It is really more related to what happens when they are using video games and certain applications. What is the change in the brain which is what we just talked about?

What is your opinion on computer education programs for screen time like Jumpstart's math, reading, and life skills?

That is a more interactive screen time leading to a generalization of that critical knowledge that we need.

How did you address this with your student whose grandmother did not know what else and how else to entertain the child?

That was a hard one. The first thing you have to do is develop trust with that parent or grandparent. What it took was showing her what we were working on and showing her the difference that it made.

References

“Common Sense Media.” Common Sense Media: Ratings, Reviews, and Advice, www.commonsensemedia.org/.

Christakis, D. A., et al. (2012). Overstimulation of newborn mice leads to behavioral differences and deficits in cognitive performance. Scientific Reports, 2(1).

Handheld screen time linked to delayed speech development. (2017) ASHA Leader, 22(8),16.

Hinkley, T., Verbestel, V., Ahrens, W. et al. (2014). Early childhood electronic media use as a predictor of poorer well-being: a prospective cohort study. JAMA Pediatrics, 214(168), 485–492

Kabali, H., Irigoyen, M., Nunez-Davis, R. et al. (2015). Exposure to and use of mobile devices by young children. Pediatrics,136, 1044–105

Kardaras, N. (2016). Glow kids: How screen addiction is hijacking our kids and how to break the trance. St. Martins Press.

Napier, C. (2014). How use of screen media affects the emotional development of infants.” Primary Health Care, 24(2),18–25.

Radesky, J.S., Silverstein, M., Zuckerman, B. et al. (2014). Infant self-regulation and early childhood media exposure. Pediatrics, 133, 1172–1178.

Radesky, J.S., Peacock-Chambers, E., Zuckerman, B. et al. (2016). Use of mobile technology to calm upset children: Associations with social-emotional development. JAMA pediatrics, 170, 397–399.

Schmidt, M.E., Haines, J., O’Brien, A. et al, (2012). Systematic review of effective strategies for reducing screen time among young children. Obesity, 20, 1338–1354.

Shaheen, S. (2014). How child’s play impacts executive function-related behaviors. Appl Neuropsychol Child., 3, 182–187.

Wolf, M. (2018). Reader, come home. HarperCollins.

Citation

Neal, A. (2020). Digital diets and the impact of screen time on development. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5237. Retrieved from http://OccupationalTherapy.com