Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Emotional Intelligence In Healthcare: Driving High-Quality Care And Team Performance, presented by Robin Arthur, PsyD.

*Please also use the handout with this text course to supplement the material.

Learning Outcomes

After the course, participants will be able to:

- List the five core domains of emotional intelligence.

- Describe the impact of high versus low emotional intelligence behaviors on teamwork and organizational culture in healthcare.

Explain evidence-based strategies to enhance self-regulation and empathy in a healthcare setting.

Introduction

Thank you for taking the time to be here today. I want to begin by recognizing the extraordinary work you do every single day. Whether you are supporting patients at the bedside, coordinating care across teams, or holding space for families in difficult moments, you are the very heart of healthcare. Having worked in this field for thirty years, I truly understand your world and the unique perspective we share as practitioners. What often makes the greatest difference in our work is not just our clinical experience, but also how we connect, listen, and respond under pressure. That is what today is about- focusing on emotional intelligence.

History of Emotional Intelligence

Let's start with a little bit of history because understanding where emotional intelligence comes from helps us appreciate its relevance in healthcare today. The roots go back to about 1920 when Edward Thorndike introduced the concept of social intelligence. Essentially, that is the ability to understand and manage all people. This was revolutionary at the time because suggesting that intelligence was not just about our logic, our reasoning, and our memory was unheard of.

Then in the 1940s, David Wechsler, the same psychologist who you might recognize from IQ testing, also argued that non-intellective abilities, such as emotions, play a vital role in how intelligently we behave.

By 1983, Howard Gardner expanded this further with his theory of multiple intelligences. That introduced interpersonal and intrapersonal intelligences as precursors to what we now refer to as emotional intelligence or the emotional quotient. Together, these became the conceptual building blocks for what we now think of as emotional intelligence.

Later in the 1990s, two researchers, Peter Salovey and John Mayer, formally coined the term "emotional intelligence" as the ability to monitor one's own and others' feelings and emotions, to discriminate among them, and to use this information to guide one's thinking and actions. This work positioned emotional intelligence as a measurable cognitive skill distinct from your personality or your intelligence quotient.

For us in healthcare today, this is key. It means emotional intelligence is not just an innate trait. It is a skill that can be developed to improve our patient care, our teamwork, and our leadership as we move forward. When you hear me talk about leadership, I want you to consider that, regardless of whether you are in a formal leadership position, you are absolutely a leader. As patient care providers, we all lead our patients to better health and better mental health. Whatever form of interventions you are doing with patients, you are their leader, so I want you to imagine yourself as a leader when you think about these concepts.

Then, in 1995, Daniel Goleman brought all this research to the public. He wrote a book called Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ. His work popularized the concept and tied it directly to leadership and workplace performance. His later publication, Primal Leadership, expanded that further into different leadership styles that we are going to talk about later on.

Daniel Goleman identified self-awareness, self-regulation, motivation, empathy, and social skills as the domains we are going to discuss today. A meta-analysis also confirmed that emotional intelligence enhances teamwork, communication, and patient safety. I have highlighted newer studies here as well. It is no longer a soft skill to think about emotional intelligence. Evidence-based leadership is essential to modern healthcare.

Why EI Training is Important

In healthcare, we pride ourselves on our technical skills. We often define our professional identity as the best therapist or the best nurse who knows clinical work very well. However, we also need to take pride in the encounters we have with patients, the factors that determine whether a team thrives, and how we manage ourselves in stressful moments. We all know that healthcare can be extremely taxing at times, and emotional intelligence has a direct impact on patient outcomes. It reduces medical errors, protects your patients' mental health, safeguards your own mental health, and enhances collaboration. As an occupational therapist who has seen the inner workings of many healthcare teams, I have witnessed the impact these skills have in real time, helping us become better clinicians and leaders. Emotional intelligence is not a fixed trait. It is a set of trainable skills we are going to explore today, and developing these abilities will drive your career advancement as well.

Intelligence Quotient (IQ)

So let us look at the difference between IQ and EQ. The intelligence quotient was developed in the early 20th century. When I conduct IQ testing with individuals, I am looking for their ability to reason, their analytic reasoning, their linguistic skills, and their spatial orientation. There are four main areas that an IQ test will provide. These include your verbal comprehension, which is understanding and using language, and your perceptual reasoning, which involves analyzing and solving novel problems. It also measures your working memory, which is the capacity for holding and manipulating information, and your processing speed, which determines how efficient you are at basic cognitive operations. All of these things are extremely important for every single one of us in healthcare.

IQ is what I call the raw cognitive horsepower. It is necessary to master all of our technical skills. However, while IQ predicts our academic performance and technical competencies, research consistently shows it explains only a portion of workplace and clinical effectiveness. While your IQ might get you through the rigorous academic requirements of your healthcare degree, your EQ is often what determines your success in the actual practice of patient care. It is the bridge between knowing what to do clinically and being able to actually deliver that care in a way that the patient can receive and act upon. This distinction is vital for us to understand as we look at how to improve our professional interactions and patient outcomes.

Emotional Intelligence (EQ)

And the other piece of that is your emotional intelligence. Your emotional quotient is your ability to read the soft skills of human interaction and use them toward positive ends. It reflects how your emotions are processed and applied in the real world. When I help organizations hire their executives and conduct employment testing, I obviously want to know how smart people are and what their IQ is, but I really look for how well they have developed their emotional intelligence. If I have a choice between a very bright human being who lacks a high emotional quotient and someone who is bright but has a really high emotional quotient, I am going to hire the person with the high emotional intelligence first. That is how important these skills are, especially in leadership positions.

Unlike your intelligence quotient, which is relatively fixed, your emotional intelligence is a set of skills that can be improved with practice and intention. In our work as occupational therapists, this means we can actually get better at managing the room, de-escalating tense situations, and building trust with our patients even when the clinical environment is chaotic. This flexibility is what makes it such a powerful tool for professional development. While your technical skills are the foundation of your practice, your ability to navigate the human elements of care will ultimately define your impact and longevity in this profession.

Mass General Hospital Institute of Health Professions

Emotional intelligence in healthcare fosters environments that promote empathy, understanding, and collaboration. It is truly the cornerstone for effective leadership, and this concept summarizes why we must view it as a clinical skill rather than just a soft skill. When empathy and understanding are embedded in a team culture, communication improves, trust builds, and collaboration strengthens. All of these elements are necessary for us to provide the highest level of patient care. For leaders, this is a cornerstone because it helps us be highly effective with our employees, and I will discuss specific leadership styles as we move forward.

We will explore all of these principles together. I have included research demonstrating the importance of emotional intelligence to our practice, including studies published as recently as 2023, 2024, and 2025. These findings provide strong evidence that emotional intelligence is not just a nice-to-have quality. It is a measurable factor in how effectively people lead, communicate, and collaborate. I will emphasize this several times throughout our session because it is central to how we function as clinicians and leaders.

Healthcare Relevance

I will tell you that emotional intelligence training is one of the most requested topics in both healthcare and the private sector across all businesses. Everyone is looking for ways to enhance their emotional intelligence because high EQ clinicians reduce medical errors by staying calm under pressure. If you have a high EQ, you are able to maintain your composure and think clearly during emergency situations or high-stress moments. Teams with emotionally intelligent leadership show better collaboration, lower turnover, and stronger patient outcomes. That lower turnover is critical in healthcare because we already face a shortage of providers, and it is very costly to an organization to lose and retrain staff.

EQ training also reduces burnout and compassion fatigue. We must be compassionate toward ourselves first, as well as our patients and colleagues. In healthcare, compassion fatigue is a common result of low emotional intelligence. To help you reflect on your own skills, I want to take a couple of minutes to go through a quiz together. This is a 33-item measure developed to assess emotional intelligence (See handout). This scale has been widely validated across healthcare, education, and organizational settings and is available for educational use. As you read these, please rate yourself on a scale of 1 (never), 2 (rarely), 3 (sometimes), 4 (often), and 5 (very often). I will note which items should be reverse-scored.

Please consider these statements:

- I know when to speak about my personal problems to others.

- When I am faced with obstacles, I remember times when I faced similar obstacles and overcame them.

- I expect that I will do well in most things that I try.

- Other people find it easy to confide in me.

- I find it hard to understand the nonverbal messages of other people (For this one, please reverse score so that never is a five and very often is a one).

- Some of the major events in my life have led me to reevaluate what is important.

- When my mood changes, I see new possibilities.

- Emotions are one of the things that make my life worth living.

- I am aware of my emotions as I experience them.

- I expect good things to happen.

- I like to share my emotions with others.

- When I experience a positive emotion, I know how to make it last.

- I arrange events others enjoy.

- I seek out activities that make me happy.

- I am aware of the nonverbal messages I send to others.

- I present myself in a way that makes a good impression on others.

- When I am in a positive mood, solving problems is easy for me.

- By looking at their facial expressions, I recognize the emotions people are experiencing.

- I know why my emotions change.

- When I am in a positive mood, I am able to come up with new ideas.

- I have control over my emotions.

- I easily recognize my emotions as I experience them.

- I motivate myself by imagining a good outcome to tasks I take on.

- I compliment others when they have done something well.

- I am aware of nonverbal messages other people send.

- When another person tells me about an important event in his or her life, I almost feel as though I have experienced the event myself.

- When I feel a change in emotion, I tend to come up with new ideas.

- When I am faced with a challenge, I give up because I believe I will fail. (For this one, please reverse score so that never is a five and very often is a one).

- I know what other people are feeling just by looking at them.

- I help other people to feel better when they are down.

- I use good moods to help myself keep trying in the face of obstacles.

- I can tell how people are feeling by listening to the tone of voice.

- It is difficult for me to understand why people feel the way they do. (For this one, please reverse score so that never is a five and very often is a one).

I will give you a moment to add those numbers up so you can see where you fall in the low, average, or high emotional intelligence categories. Please keep in mind, as you look at your results, that none of us possesses perfect emotional intelligence, just as none of us has a perfect IQ. This is simply a tool to help you realize where you may need to work harder. Do not judge yourself based on these categories. If you scored between 33 and 87, you fall into the low emotional intelligence category and may have difficulty identifying or managing emotions. If you scored between 88 and 121, you have average emotional intelligence and demonstrate adequate understanding in most situations. If you scored between 122 and 165, you have high emotional intelligence and a strong ability to manage emotions in yourself and others. Regardless of your score, remember that EQ can be learned, which gives us all the opportunity to continue improving as we move forward.

Low Emotional Intelligence Example

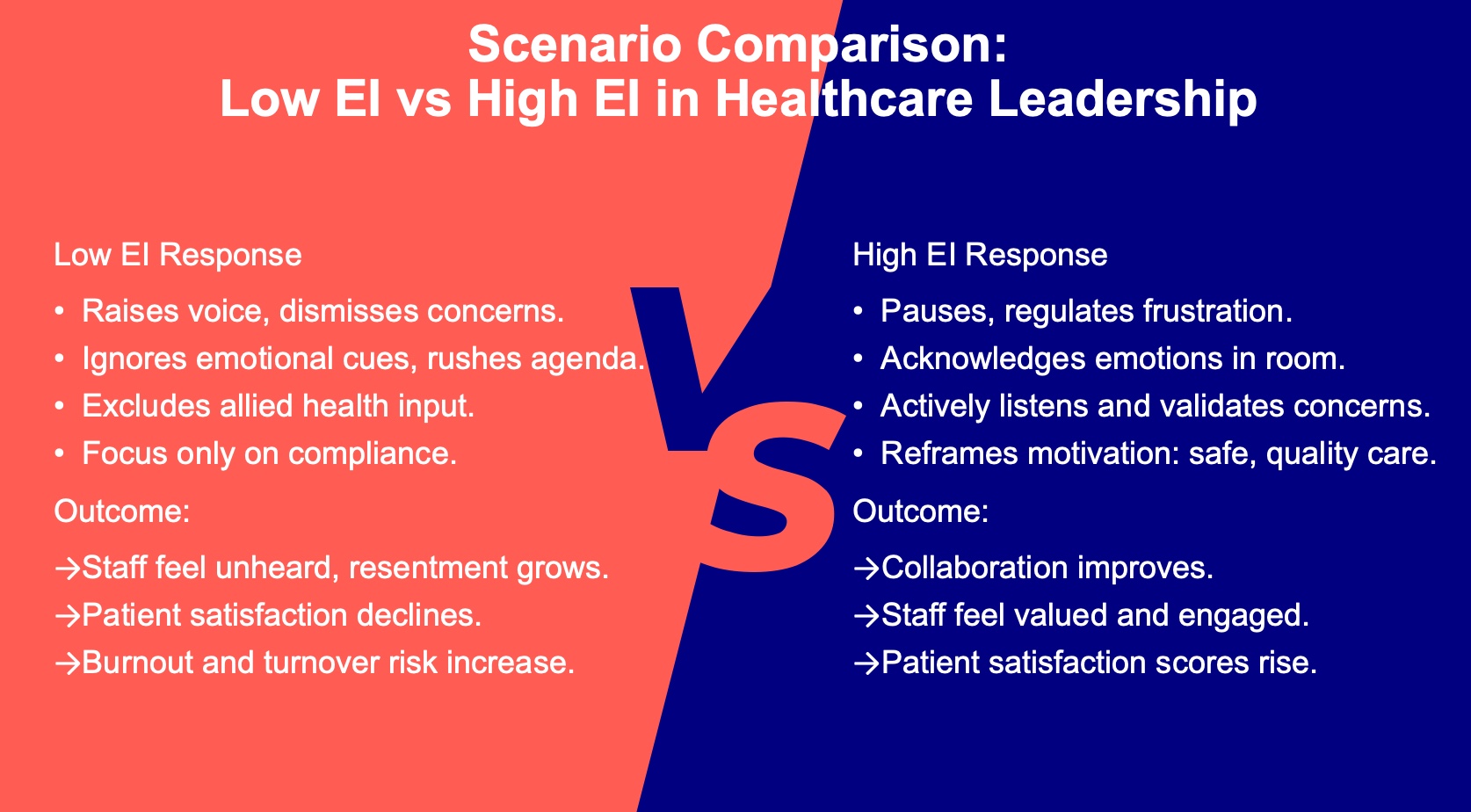

Let us look at an example of low emotional intelligence in a clinical setting. Imagine a hospital is rolling out a new electronic health record system. Tensions rise as physicians complain about the software's efficacy and nurses worry about the increased documentation burden. Allied health staff feel excluded from the process, stress levels spike, and patient care begins to suffer.

I have actually been in this exact situation while consulting at a hospital. In this scenario, the charge nurse reacts defensively. She raises her voice and tells the staff that this is the system they have, and they simply need to deal with it. She ignores the emotions in the room, rushes through the agenda, dismisses input from allied health professionals, and focuses strictly on compliance.

The result is that the tension remains unresolved and the staff feel unheard. Resistance to the new system grows, patient satisfaction drops, and burnout rises as the team culture begins to erode. We know that burnout and disengagement occur when leaders fail to use emotional intelligence in high-pressure moments.

High Emotional Intelligence Example

On the other hand, let us look at the same exact scenario handled by a nurse with high emotional intelligence. In this case, she regulates her own frustration before speaking because she is likely frustrated with the new system as well. She acknowledges all the emotions she sees in the room, listens actively, and validates those concerns.

She reframes the motivation for the change, reminding the team that they are doing so to meet their shared goal of safe, high-quality care. She also facilitates collaboration by inviting everyone to share their ideas and amplifying them in the meeting. The result of this approach is that the meeting ends with a pilot improvement plan. Staff leave feeling heard and valued, and they are likely far less frustrated.

Patient satisfaction scores improve because the team is working well together, and the system is reframed as a manageable tool rather than a threatening new implementation. You can see how significant the difference is simply by cultivating high emotional intelligence and staying calm.

The side-by-side comparison in Figure 1 clearly shows what happened in both scenarios. It illustrates the contrasting paths between a leader who reacts defensively and one who responds with emotional awareness.

Figure 1. Comparison between low EI and high EI in healthcare leadership. (Click here to enlarge the image.)

Daniel Goleman: What Makes a Leader

Daniel Goleman, who really brought emotional intelligence to the mainstream, says most effective leaders are alike in one crucial way. They have a high degree of emotional intelligence. Without it, a person can have the best training in the world, an incisive analytical mind, and endless smart ideas, but this still will not make a great leader. That is so true in healthcare.

We all work in environments that are filled with complexity and high stress. Our expertise and training are essential, but when they are not enough, what makes us truly effective is our ability to read a room. We can study a team whose tensions are running high, or a patient whose anxiety is peaking. We can lead with empathy and clarity, even when the pressure is on.

Goleman's message reminds us that emotional intelligence is not optional. It is the differentiator. It is what turns your technical excellence into human-centered leadership and patient care.

Emotional Intelligence and Leadership

As we move forward, I want to share some statistics with you. IBM conducted a study in which they examined over 1,000 of their employees, and 74% said emotional intelligence was the most important characteristic for a leader to possess. However, only twenty-eight percent felt that their leaders demonstrated this adequately. That is a dismal gap.

Emotional intelligence continues to be seen as a primary asset even today. More recent organizational studies suggest that while seventy to eighty percent of professionals view emotional intelligence as important, fewer than twenty-five to thirty percent believe their leaders embody it. This means that twenty or thirty years later, we are still struggling with emotional intelligence not being widely valued or trained in all business situations.

My personal bias is that healthcare professionals already possess high emotional intelligence. It is part of the reason we choose the work we do. But we can all benefit from more training and getting better. Even though I teach this subject, I still regularly take courses on emotional intelligence. I do not see that as a weakness; it is simply a commitment to continually improving what I do. Strengthening these capacities closes the gap between empathy and practice, improving every facet of patient care while supporting your own professional well-being.

Warren Bennis: Father of Modern Leadership

Warren Bennis was one of the most respected voices in leadership. He is often called the father of modern leadership studies. He spent decades at Harvard, Boston University, and Southern California, and he also served as the president of my alma mater, the University of Cincinnati. He wrote at least 30 books on leadership, including a classic called On Becoming a Leader, if you are ever interested.

His work emphasized that leaders are made, not born. This is a vital distinction because it suggests that a successful leader is set apart by more than just their intelligence quotient. The capacity for self-awareness, empathy, and connection with others will catapult you to the top of your career. This is why his perspective is so important for us to understand. While technical proficiency provides the baseline for our work, it does not necessarily make you a star, but emotional intelligence can. I truly love the work of Warren Bennis and the foundation he built for how we view leadership today.

Five Core Emotional Intelligence Domains

Let us examine the five core domains of emotional intelligence. In his 1995 book, Daniel Goleman introduced these five pillars: self-awareness, self-regulation, motivation, empathy, and social skills. These are the specific areas we will be studying as we move forward.

It is important to consider the outcomes of low emotional intelligence that you may not have previously thought about. Research demonstrates that when you have a lower emotional quotient, you are less efficient at work and in your personal life. It also correlates with more serious health problems; in essence, low emotional intelligence leads to poor health. Furthermore, you are more fatigued when your emotional skills are underdeveloped, and this can even contribute to premature aging. When you consider the physical and professional toll these factors take, it becomes clear why we should all strive to improve.

If you do not have a way to take notes, this would be a good time to get something ready. I am going to provide many tools to help you strengthen each facet of your emotional intelligence. You might find that you are naturally high in self-awareness but have never put much work into developing your empathy. This next section will be a time for you to identify which specific area you need to strengthen most and which areas you already feel confident in.

Before we dive into the details, I want to share a scenario called When Pressure Turns to Pushback. Maria is a lead speech-language pathologist in a busy outpatient rehab clinic. The department is short-staffed, evaluations are backed up, and administration is pressuring her to decrease wait times. At the morning huddle, one of her practitioners, Jenna, quietly admits she is overwhelmed and does not think she can take on another swallow study without a pause. Maria snaps and tells her that everyone is overwhelmed and that she needs to figure it out because there is no time for excuses.

The room goes silent. Throughout the day, Maria avoids eye contact with her team and sends brusque emails demanding tasks be done by the end of the day. She fails to notice that Jenna is on the verge of tears. In a meeting with the administration, Maria blames the team, claiming her staff lacks motivation and does not understand urgency. By the end of the week, two staff members have asked to transfer, documentation errors are increasing, and a patient has complained about feeling rushed. Maria does not understand why morale is dropping and tells herself the team just is not resilient enough.

While that might seem like an over-dramatization, most of us in healthcare have seen situations very close to this. If Maria had implemented the strategies we are discussing today, the outcomes would be very different. We will revisit Maria later to see how she might have handled that situation with better emotional skills.

EI: Self-Awareness

Let us jump into our first skill and domain: self-awareness. This involves asking yourself why you are feeling certain things and what is happening internally. Not all of us have strong self-awareness, even when we think we do, and we are often unaware of the specific areas where we need to shore this up. Our self-awareness is influenced by our childhood experiences, physiology, environment, and overall neurochemistry.

There are several examples of low self-awareness that can manifest in the workplace. You might turn every team event into something about yourself, act in a passive-aggressive manner, avoid emotions, become defensive, or feel a constant need to be the center of attention. I want you to ask yourself if you are aware that your emotions affect your work and your relationships, as these are the two main components of self-awareness. For example, a therapist might notice they leave patient interactions feeling drained or irritable. They may assume the patient does not like them or is upset with their progress, and they might get defensive if a colleague points out this reaction. After doing self-awareness exercises, the therapist can recognize that the frustration is actually their own, which improves their interactions with both patients and colleagues.

Self-awareness is the recognition of your feelings, their intensity, and their effects on you personally and professionally. If you find yourself thinking everything is always someone else's fault, you likely need to work on this domain because it is impossible for every conflict to be the responsibility of others. I want to share some specific techniques with you, and this is where you may want to take notes.

The first technique is reflective journaling. You should document emotionally charged interactions, noting what triggers your responses and how those emotions influence your communication and decision-making. You should also work on the body-mind connection. When you feel your jaw tighten or your breath become shallow, you need to recognize that tension and intentionally reset.

Breathing exercises are a great way to ground yourself. We will practice the box breathing technique now. You breathe in for a count of four, hold for four, breathe out for four, and hold for four. Let us try one round together. Breathe in, two, three, four. Hold, two, three, four. Breathe out, two, three, four. Hold, two, three, four. Please do two more of those on your own. This is an easy exercise to use after a difficult interaction because nobody even knows you are doing it. Scanning your body and your nervous system will tell you exactly when you need to calm yourself down.

Another powerful though vulnerable strategy is seeking 360-degree feedback. If you feel safe with a supervisor or colleague, ask them about your communication style, your listening behaviors, and your emotional tone of voice. You can simply explain that you are trying to increase your emotional intelligence and would value their perspective. If you prefer, you can start with a single trusted colleague to discuss interpersonal challenges. Getting external input is vital because we are not always the best judges of how we show up in an environment.

You can also utilize cognitive reframing to address self-critical thoughts. Many of us judge ourselves more harshly than we judge others. Instead of saying I failed, try a growth-oriented reflection like I learned how to approach this differently. Replacing 'I can't do this' with 'I am working on becoming better at this skill' helps build your internal resilience. I practice from a positive psychology perspective, which is all about finding and strengthening your existing assets.

In terms of professional growth, you should seek out mentors who model emotional intelligence and can provide constructive reflection on relational challenges. Within your teams, consider doing emotional check-ins during rounds or huddles. You can begin a meeting by asking everyone for a one-word description of their emotional state. I often use a tool called a feelings wheel in my meetings to help normalize this expression. It gives everyone a read on the room and models the healthy integration of emotion into the workplace.

Finally, remember to apply this in your personal life. If you walk into your house after a long day and feel a spike of irritation when someone asks what is for dinner, self-awareness allows you to recognize that you are not actually upset with them; you are just exhausted and hungry. By identifying that feeling, you can say you need ten minutes to decompress before talking, which prevents an unnecessary conflict. These are just some of the many ways you can strengthen your self-awareness.

EI: Self-regulation

We have explored self-awareness, and now we will transition to self-regulation. This is your ability to manage disruptive impulses, often referred to as self-control. It involves being competent in emotion regulation while remaining accountable, flexible, and authentic. High self-regulation is demonstrated when you identify unproductive behaviors and stay focused, take responsibility for your actions and inactions, and remain adaptable when change occurs.

Consider a scenario during evening rounds where a patient’s family confronts a therapist, expressing anger that progress is too slow. The therapist feels their chest tighten and an urge to be defensive. Instead of snapping, they use the 90-second rule, pausing to take deep breaths. They respond calmly by acknowledging the family's worry and walking them through the treatment plan. The result is that the family feels validated, and the therapist maintains professionalism under stress. Self-regulation is not about suppression; it is about harnessing physiological sensations and using tools like breathing and reframing to preserve trust and safety.

As a neuropsychologist, I am fascinated by the brain. Understanding the neuroscience of emotional intelligence provides a strong framework for what is happening within you. Your brain processes eighty-six billion neurons with trillions of connections. While it is remarkably fast, it is divided into three functional components that influence self-regulation.

The first is the reptilian brain, consisting of the brain stem and basal ganglia. This is our most primitive system, responsible for survival functions such as respiration and the fight-or-flight response. It is developed by six months of age, possesses no sense of self, and has zero impulse control. It simply reacts. The second is the mammalian brain or limbic system, which includes the amygdala, hippocampus, and hypothalamus. Developed by age six, it regulates emotions, motivation, and social bonding. It allows us to experience fear, joy, and empathy. While it seeks social belonging, it has low impulse control and seeks immediate relief from distress. In healthcare, these two brains enable us to connect with patients, but they can overwhelm us if they are unchecked. They are powerful and fast, but they lack wisdom and are entirely focused on the immediate moment.

Fortunately, we have the neocortex, specifically the prefrontal cortex. This is your executive center, responsible for reasoning, planning, reflection, and impulse control. It is the only part of the brain that rests, and it is not fully developed until your mid-twenties. Its function is to act as the parent or mentor to the lower two brains. Under high stress, a metaphorical trapdoor can shut between the lower brains and the neocortex. When this happens, reaction time stays high but judgment drops, leading to impulsive actions and emotional outbursts. To keep this trapdoor open, you must plan for disconnection and utilize self-soothing techniques.

To strengthen your self-regulation, again, you can use the ninety-second rule and breathing techniques. When you feel an emotional surge, stop and allow the urge to pass before acting. You can also use progressive muscle relaxation. For example, clench your fists for several seconds and then release. Do the same with your biceps, shoulders, and facial muscles. This helps release stored physical tension and regain self-control.

Mindfulness micro-breaks and cognitive reframing are also effective. Instead of thinking a colleague isn't listening, reframe the thought to consider that they might be under stress too. I also highly recommend if-then planning. This involves pre-deciding your responses to triggers. For example, if I feel defensive in a meeting, then I will pause and ask for clarification. If I feel overwhelmed, then I will take a micro-break. Simply pausing between listening and speaking ensures your emotional tone matches your intention.

Environmental supports and emotional diaries are additional tools. You can record your triggers and responses to identify patterns. Superiors should normalize these practices by talking about them openly in huddles. End your day with a ritual of deep breathing and reflect on one interaction that went well. Managing upsetting feelings like anxiety and anger is a form of disease prevention, which is why emotional intelligence is so vital for our physical and mental health.

EI: Motivation

Now we are going to move on to motivation. Motivation is your inner drive to work beyond rewards. This comes from deep inside of you and is not about money, surroundings, or power. It is about purpose, passion, and persistence. When you have strong self-motivation, you want to achieve goals and improve your job performance. You are able to cope with future change and do it well. In a healthy way, being motivated helps you meet challenges and is largely determined by your attitude, which brings in our positive psychology techniques. A healthy attitude will enhance your life motivation.

Examples of strong motivation include being driven to meet higher standards, whether or not others recognize them. You seek to overcome unsatisfactory situations and demonstrate persistence to achieve at a high level, even in the face of stress. Reflecting on what personally motivates you deep inside is key. In Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, the lower levels, such as physiological and safety needs, often arise from external motivation. As you move toward the top with self-esteem and self-actualization, those absolutely come from inside of you. Many of us are motivated by external things when we are younger, but as we age, we are motivated more by internal factors.

Here are some ways to strengthen your motivation. First and foremost, clarify your why. This is vital in healthcare because the work can be tough and overwhelming. When you find yourself wondering why you became a practitioner or thinking that nobody understands how hard the job is, revisit your personal and professional reasons for entering this field. Connect those reasons back to your values. In doing this, you can create a mission reflection, which is a one-sentence description of how your daily work contributes to patient well-being, team outcomes, and your own well-being.

I also love the concept of legacy thinking. Ask yourself what impact you want to leave behind for your patients and colleagues during your workday. That is what will motivate you for the day. You can also use smart micro-goals to turn a large project into small, trackable wins. We know that when we have small wins, we are more likely to stay motivated toward the end goal. Acknowledge your competence by listing three professional strengths you use each week and looking for evidence of growth in those areas.

You can also do strengths mapping. You can look up the VIA character strengths online and take a free quiz to identify your positive character strengths. Positive psychology is all about identifying our positives and using them to optimize our lives. Another skill is appreciative inquiry, which involves focusing on what is working well before tackling problems. This enhances both motivation and morale. You can also implement micro-habits such as deep breaths, hydration breaks, or sunlight exposure to improve your energy management. Track what energizes you and what drains you so you can focus on the former and minimize the latter.

To further enhance motivation, consider recognition rituals. While some people feel indifferent toward awards, research shows that starting or ending meetings by recognizing acts of compassion or empathy increases the motivation to continue those behaviors. These must be meaningful, real recognitions, not just manufactured compliments. You can also encourage peer inspirations where staff members share stories of successes they saw in others.

Lastly, if you are a leader, transparent communication motivates your teams. It links their daily tasks to larger organizational goals and patient outcomes. It is important to be as transparent as possible. Do not forget to celebrate milestones, anniversaries, and positive patient outcomes. In healthcare, we frequently hear about the negative outcomes, so we must talk about the good ones to stay motivated in the work we chose.

EI: Empathy

Now we are moving on to empathy. Empathy is recognizing others' emotions and their intensity. It is your awareness of others and is broken into three distinct components.

Empathy involves being aware of others' feelings and concerns. It is also service-oriented, meaning meeting the needs of customers and colleagues, practicing active listening, and establishing rapport. If I think about the three main parts of empathy, they are cognitive, emotional, and compassionate.

Cognitive empathy is the understanding of what someone is going through. This connects to their emotional experience, supports accuracy in assessing someone, and reduces miscommunication. Emotional empathy, or affect, is the feeling of being with someone. When you are attuned to what someone is experiencing, you might feel that with them, which supports the connection and the therapeutic alliance. Finally, when you communicate that understanding, it becomes behavioral. This is compassionate empathy where you convey that you are present and ask how you can help. This prevents emotional overload.

We must be careful with empathy to maintain good boundaries. If we are too empathic and take on everything others are feeling, we will burn out. Empathy is both an emotional and a clinical skill that supports assessment accuracy, adherence, teamwork, and safety.

Examples of empathy include recognizing others' body language and adjusting to it. If you see someone who is sad, you adjust your approach. It also involves forming alliances easily, dealing with others' extreme emotions, and leading with greater understanding. If empathy is absent, you may seem uncaring to patients or dismissive to colleagues, so it is important to increase your skills in this area.

I want to share some tools for increasing empathy. The first is perspective taking. It is important to realize other people's perspectives as much as our own by focusing on the speaker and avoiding multitasking. One thing people often overlook is silence. Silence is empathy. It allows for pauses in patient or team conversations and shows respect and space for emotions. If someone becomes emotional, instead of jumping in to solve the problem or comfort them, consider silence as a way to foster greater understanding.

Perspective-taking involves placing yourself in a colleague's or a patient's position and imagining their emotional experience. You can also practice life mapping, which involves visualizing the person beyond the clinical moment. Think about their family, their culture, the trauma they may have experienced, and their resilience. When you life map, you see them as a whole person rather than just a patient in a bed.

You can also conduct empathy interviews by asking open-ended, non-clinical questions. Asking what has been hard for a person this week may have nothing to do with their physical body, but it shows you care about them as a person.

Boundary training is also a critical part of empathy. We must learn empathic detachment, which is the practice of emotional connection without over-identifying. As I mentioned, if a patient is crying and you start crying with them, it can sometimes convey that things are even worse than they are. You want to have empathy for their emotions without taking them on wholeheartedly. Practice awareness of emotional contagion by noticing when you become absorbed in others' emotions, and use grounding techniques to bring yourself back to a stable state.

Within your teams, you can use role swaps where different disciplines share emotional challenges or shadow each other. You can also implement team empathy rounds to highlight examples of staff members showing exceptional empathy. Finally, use the teach-back tone. When you ask patients to restate instructions, do not just listen for accuracy; listen for their level of confidence or any hesitation. Use simple, authentic phrases and find a mentor who demonstrates empathy well.

EI: Social Skills

All right, let us look at social skills. Social skills are vital because they enable us to build rapport, resolve conflict, and foster effective collaboration. If you inspire others to dream more, learn more, do more, and become more, you are a leader. I just really like that quote, so I included it here.

Relationship management is the capstone of our work. This is how we manage our connections through influence and the development of others, which is critical in healthcare. It also involves managing conflict. It is not about avoiding it; it is about managing it effectively. In healthcare, we face high-stress conflict at times, but emotional intelligence helps us to de-escalate those moments and reach true collaboration. This requires psychological safety. If we have strong emotional intelligence, we create psychological safety in our environment. When we talk about managing relationships, we are really talking about creating the conditions for trust, growth, and shared purpose. That makes us better colleagues and better caregivers.

Specifically, when we look at this as teams, emotionally intelligent leaders do not simply give directions; they build connections. I want to give you four questions to ask yourself when you are managing a team. What can I control? What can I not control? What am I trying to control? And what am I trying to control that I cannot control? If you go into team relationships and management with those questions in mind, it is going to help you perform these tasks better. You are going to allow your team to feel empowered.

When you manage a team well, you build clarity and consistency. When people feel respected and trusted, they are better able to be part of your team. Allow them to feel empowered and help them understand their contribution to the strategy. It is just as important for your team to feel like they are part of the process, not just being talked at. Inspire your team to feel motivated to do their best work and treat others fairly. It is really important to treat others fairly and inspire them to feel proud of their work.

When we are influencing people, there are many strategies we can use. In healthcare, influence is not manipulation or control; it is about guiding people to shared goals. Emotional intelligence gives us multiple strategies for doing this effectively. First and foremost, if you are trying to influence people, just be friendly. Use empowerment by giving others ownership. Influence them by your vision, as people are more likely to follow you if they see a bigger purpose. Build alliances, as collaboration across disciplines is essential. Use bargaining when we have to give to get. Every once in a while, influence relies on formal authority, and we have to know when to flex between all of these strategies.

Here are some ways to strengthen your social skills. Some of these overlap with our other domains, as emotional intelligence skills often do. Focus on active listening and validation. You can use micro-clarifications, such as summarizing what someone has said to you, and purpose-linking, which is reminding your teams how their individual roles connect to patient outcomes. Shift from a management mindset to an empowerment mindset, where you enable contribution and model calm confidence. Regulate your tone, your body language, and your pacing during high-stress situations.

Mentorship is also important. We must mentor our younger clinicians as they advance in the workforce. Practice professional compassion by recognizing when colleagues are struggling. Be grateful for what is going well. I try to write at least one thank-you note every other week to someone in my life, especially in the work environment, to show gratitude for what is happening. We must also continue to prioritize the active listening we discussed previously.

Emotional Intelligence and Leadership, Cont.

A little bit more statistics for you. Eighty-one percent of healthcare employees thought empathy was very important, but only 31% thought their leaders were empathetic. This is so important for us in leadership to understand.

So let us revisit Maria quickly. Now that Maria has taken this course, the situation is the same: staff shortages and the same evaluation backlog. But this time, Maria uses high emotional intelligence. At the morning huddle, when Jenna says she is overwhelmed and does not think she can take an additional swallow evaluation today, Maria pauses. She takes a deep breath before responding and says calmly that she appreciates the honesty and that she understands Jenna is at her capacity. She suggests walking through options to make the workload feel sustainable. She asks the group who has room for an evaluation, what things can be done to help, and what support they need from her.

Throughout the day, Maria checks in privately with Jenna. She emails the team to thank them. She advocates to the administration, stating that her team is highly committed, but the current volume is not sustainable. By the end of the week, the caseloads are redistributed equitably. Team members feel heard and valued. Patient satisfaction scores go up, and the team begins offering process improvement ideas because they trust Maria.

You can see that just by incorporating these skills, Maria is a much more effective leader. It trickles out to her staff, and she no longer has people wanting to leave her department. This transformation shows how emotional intelligence creates a sustainable environment for everyone involved.

Leadership Styles

Now, let me go over these leadership styles that Daniel Goleman proposed in his second book, Primal Leadership. The first style is the visionary leader. This is a person who provides clear long term direction and connects daily work to a broader mission. In healthcare, this would be a leader who helps you see the vision of how a new patient safety initiative or an electronic health record implementation will ultimately help the entire organization.

The second is coaching leadership. We all do a lot of this when teaching students. Coaching leadership focuses on individual growth, feedback, and long-term development. I do a lot of coaching with my doctoral students and with medical residents. As a senior clinician in your field, you use this style when you mentor new graduates. It enhances professional efficacy for both the mentor and the mentee.

The third is what we call affiliative leadership. This builds harmony, emotional connection, and strong team bonds. In healthcare, it is especially valuable after an emotionally taxing event. If you experience the death of a patient, or when staff morale is low due to pandemic-related stress, affiliative leadership communicates that we are all in this together, fostering psychological safety and resilience.

The fourth is democratic leadership. It seeks input, fosters collaboration, and encourages shared decision-making. This is very well suited for interdisciplinary teams, which are ubiquitous in healthcare. Democratic leadership improves staff engagement, job satisfaction, and team performance.

The fifth is what we call pacesetting leadership. It sets high standards, models excellence, and expects rapid achievement. In healthcare, this is effective with high-functioning teams that thrive on autonomy and competence, such as surgical teams or elite trauma teams. We have to keep in mind that overuse can cause stress and burnout, so you must balance pacesetting leadership carefully.

The sixth is commanding leadership. This is a directive, authoritative style used in crisis situations. During a code blue, a mass casualty event, or an infectious disease breakout, you want a commanding leader to be in charge. We must be careful not to rely too much on commanding leadership, as it can lead to low morale when used excessively. A trauma team leader will give direct, rapid-fire instructions during a resuscitation, but you do not want them acting that way when you are not in a trauma situation.

These six styles are important to remember and they are not stagnant. No single style is sufficient on its own. We really need to be flexing between them, being adaptable and fluid. This adaptability is what equals high emotional intelligence.

Suzanne Gordon: Team Intelligence

Team intelligence is essential to our work in healthcare. Suzanne Gordon, an award-winning journalist who has written twenty books, including Teamwork in Healthcare and Beyond the Checklist, emphasizes this through her research on quality improvement. Her concept of team intelligence emphasizes that clinical expertise alone is insufficient to ensure patient safety or organizational success. We have heard this theme repeatedly throughout this training, but it bears repeating. We must move beyond a purely technical focus and intentionally teach emotional intelligence as a core component of how we function together.

Team intelligence recognizes that a group's collective knowledge is only as good as the communication channels through which it flows. When we incorporate these emotional skills into our teams, we are not just being nice to one another; we are actively preventing errors and improving the quality of the care we provide. As we conclude this portion of our discussion, remember that your growth in these areas directly influences the effectiveness of the entire team.

Amit Ray: Compassionate AI Pioneer

Amit Ray is an authority and ethicist who emphasizes that as artificial intelligence grows, emotional intelligence must guide our leadership. I include this perspective because we all know that artificial intelligence is becoming increasingly relevant worldwide, and it will be infused into healthcare as well. Our emotional intelligence is going to help us as we adapt these technologies into our healthcare work. In my experience as a practitioner, I have seen firsthand that healthcare teams with high emotional intelligence transform situations. We saw that clearly with Maria. When her emotional quotient was low, the situation was not going well. In the hospital setting, the environment was dismal, and people wanted to leave her department. However, once she learned these skills and started using them, her people wanted to be with her, and there was a significant improvement in patient care and in interpersonal dynamics among all employees. Those are our five domains and our six leadership styles.

Call to Action

As we close, I want to leave you with four simple but powerful steps you can begin using right away. First, commit to just one emotional intelligence practice for thirty days. Go back and look at which one of these domains you need to strengthen the most, pick one of the skills to practice, and do it consistently. It could be something easy like taking mindful pauses before responding or intentionally listening without interrupting, but that small, consistent action will build lasting change. Second, use self-assessment tools to track your progress. You can find many of these online, and they help you notice patterns in your strengths and growth areas while keeping you accountable to yourself. Third, apply these skills in your high-stress scenarios, those moments when emotions run high, and the stakes are the greatest. You want to keep that trapdoor open, so all parts of your brain are working together. This is where you can make the most difference, whether it is with patients, families, or colleagues. Finally, aim for measurable improvements in teamwork and patient care. Look for evidence of fewer conflicts, more collaboration, and higher patient satisfaction. These outcomes show that your growth in emotional intelligence is not only personal, though it will absolutely enhance your personal life, but also professional and transformational.

As we discussed at the beginning, having a high emotional quotient protects your health, makes you more efficient, and actually adds to your lifespan. By strengthening each of these domains, your stress level will decrease, and we know that maintaining lower stress levels contributes to longevity. From my thirty years in healthcare, I understand that our environments are difficult. I also understand that we do not always receive accolades for our work, nor do we always expect them.

However, I want to applaud each of you for being committed to your own growth. I understand how demanding and how rewarding healthcare work is for each of us. We came to this profession for a reason, and we likely started out with a higher emotional intelligence than many people. I appreciate you making the time today to continue to enhance that. I appreciate your time and attention, and I strongly encourage you to take this out into your world. Pick one practice and start today. Commit to making emotional intelligence part of how you show up every day for yourself, your team, and your patients. Your own well-being will benefit from this. Thank you for being here today, and good luck as you develop your emotional intelligence moving forward.

References

See additional handout.

Citation

Arthur, R. (2025). Emotional intelligence in healthcare: Driving high-quality care and team performance. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5859. Retrieved from https://OccupationalTherapy.com