Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Play And Playfulness: Intentional Integration In Everyday Practice, presented by Shruti Gadkari, PP-OTD, OTR/L, BCP.

*Please also use the handout with this text course to supplement the material.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to recognize the importance of play as the central occupation of childhood.

- After this course, participants will be able to describe play through standardized and non-standardized means.

- After this course, participants will be able to identify innovative ways to address play at an individual, group, and population level.

Introduction

I’m going to start by discussing the what, why, and how of play and playfulness, just going over some play terms. I will then cover how to conduct a comprehensive play evaluation and look at play interventions at the individual and systemic levels.

I also want to leave you with some tips and resources for incorporating play as an end and a means, particularly some national and international resources that will help you learn more about this topic. Before we get started, I want to share a bit about what made me interested in the topic of play and what led me to think more deeply about it. I’ve worked in many different pediatric settings, from schools to hospital-based settings to outpatient clinics. Earlier in my practice, I focused a lot—like many practitioners—on things like ADLs and handwriting. And whenever I asked parents what their goals for their child were, most would say things like, “I want him to be able to follow some directions, be able to focus, be able to tie his shoes.”

No one brought up the topic of play or said, “I would really like my child to be able to play with other kids” or “to be engaged in play.” I think that reflects where our society and school system are right now, with a strong focus on learning, academics, self-care, and play getting left to the wayside. When I began to teach in an OT program and teach pediatric OT courses, I started to think about this topic a little bit more. I realized that I wanted to send my students out into the field, able to evaluate play and able to write those play goals effectively.

Play & Playfulness

This is a quote from the National Institute for Play that I really like.

“Play is the gateway to vitality. By its nature it is uniquely and intrinsically rewarding. It generates optimism, seeks out novelty, makes perseverance fun, leads to mastery, gives the immune system a bounce, fosters empathy, and promotes a sense of belonging and community”

I want to highlight a perspective I value: the National Institute for Play describes play as the gateway to vitality. By its nature, it is uniquely and intrinsically rewarding. It generates optimism, seeks out novelty, makes perseverance fun, leads to mastery, gives the immune system a bounce, fosters empathy, and promotes a sense of belonging and community. They are naming the nature of play and its advantages for individuals and communities, which aligns with what I see in practice.

I will show a series of pictures, and I would be grateful if you could consider whether play is happening in each image. As you look, I invite you to notice a few cues I use in real time. I ask myself whether the activity appears intrinsically motivated rather than directed. I look for signs of internal control, like the child or group setting the pace, rules, or storyline. I pay attention to the play frame—is there a shared understanding that “this is play,” often signaled by smiles, silliness, or flexible boundaries. I watch for curiosity and novelty seeking, shifts in roles or materials, and the balance between challenge and mastery that keeps engagement alive. Finally, I consider whether the social interaction looks reciprocal and voluntary, and whether affect is positive and resilient to small setbacks.

As we review the pictures, I’ll use those markers to decide whether what we see is play, non-play, or something in between, and I’ll explain my reasoning briefly for each.

In Figure 1, I see a child just coming down a slide, clearly happy.

Figure 1. Boy going down a slide.

This is often the image that comes to mind when we think about children and play: a Playground with slides and swings, children having fun, yelling with excitement, and running back to climb again. I would consider this play if a few core elements are present. I look for intrinsic motivation—choosing to go down the slide because it’s enjoyable, not because an adult directed it. I look for internal control—pacing the climb, deciding how to descend, maybe adding a twist or a pretend storyline. I also look for a clear play frame—shared signals that “this is play,” like laughter, exaggerated movement, and flexible rules. When those elements are in view, a slide becomes more than a piece of equipment; it’s a context for joy, novelty seeking, and mastery as the child experiments with speed, posture, and turns, and then returns for another try because the experience is rewarding.

In Figure 2, you see this child splashing around in the water, looking pretty happy, and wearing their little rain boots.

Figure 2. Child playing in water.

Figure 3 shows a teacher reading a story or doing some circle time activity.

Figure 3. A teacher and kids during circle time.

The children seem to be engaged, and she seems to be engaging the children as well. Do you think this represents play?

Lastly, in Figure 4, we have some older kids sitting around at the table doing some kind of worksheets, maybe writing an essay, or your typical academics.

Figure 4. A teacher and older kids are at a table.

They seem to be engaged with their tasks. Then, the teacher gives some directions. Does this picture include any play? We'll be looking at some definitions of play, then coming back to these pictures and seeing what you think the second time around.

Defining Play

As you can see, there are many different ways to look at play, and there is no single consensus or definition. Sometimes I define play through form—the characteristics of the activity and the skills it requires. Indoor play can look very different from playing on a soccer team, and both can look different from a karate class. Each involves physical activity or play, but the form varies considerably, and so do the required skills.

I also look at play through functions—what is learned through that particular play. A child playing house may learn about their culture and imitate their parents through their play. I then consider meaning—the individual motivation or satisfaction gained from the activity. When I think about a group of teenagers playing video games together, I see motivation to participate in the activity and the social group, and perhaps a drive to be the best at the game and to defeat their friends.

Finally, I consider context—the environment in which play is happening. Whether indoors or outdoors, the context shapes the experience. Play that occurs at school may look very different from play at a neighborhood park or playground. Even within school, play in the yard or during recess differs from play that happens in PE. For me, this wide variety reinforces that play must be understood across form, function, meaning, and context.

Playfulness

Anita Bundy, who has done extensive work on play and playfulness, defines playfulness as including three key elements: intrinsic motivation, internal control, and freedom to suspend reality. Together, these three components form the basis of playfulness.

Model of Playfulness

Anita Bundy describes playfulness as a balance between an activity's intrinsic and extrinsic nature. I can’t share the visual model due to copyright, but I’ll describe it. She uses three fulcrum points: perception of control, motivation source, and reality suspension. Activities become more playful when the child perceives greater internal control, feels intrinsically motivated, and can freely suspend reality. Conversely, when control is external, motivation is extrinsic, and the frame is literal and constrained, the activity tends toward nonplayful.

With that lens, I return to the pictures. In the first image, the child on the slide appears intrinsically motivated, with full internal control and a clear suspension of reality. No one is counting repetitions or imposing timing; the activity is freely chosen and joyful. I would place this firmly on the playful end of the spectrum. In the water play example, I see the same pattern: splashing that is self-initiated, unconstrained, and done because it’s enjoyable, not required. That also falls on the playful side.

For the classroom circle-time scene, I see a gray zone. The children look engaged, yet the activity may be part of a required routine. The teacher can move it toward playfulness by introducing pretend elements, props, shared jokes, or flexible roles that enhance suspension of reality while preserving children’s choices. With those adjustments, internal control and intrinsic motivation can increase, shifting the experience along the spectrum.

In the academic task example, I recognize how challenging it can be to sustain playfulness. Many children do not bring strong intrinsic motivation to writing an essay or completing math problems, making the activity more externally driven. Bundy’s criteria place it closer to the nonplayful end of the spectrum.

Defining Terms

As occupational therapy practitioners (OTPs), we don’t have a monopoly on play. Other disciplines research, play, talk about it, and bring their perspectives. I want to present the definitions from our OT framework and align with our scope of practice. In the OTPF-4, I define play as a freely chosen, intrinsically motivated activity that is pleasurable and outside of ordinary life.

I define playfulness as spontaneity, imagination, creativity, and lightheartedness. I define leisure, per the OTPF-4, as a non-obligatory activity that is intrinsically motivated and engaged in during discretionary time. You can see the same terms surfacing again and again—spontaneity, imagination, intrinsic motivation—whether I am describing play or leisure. For me, the intrinsic nature of the activity takes precedence when I am deciding whether something is playful.

Play Terms

One way I look at play is through a developmental lens. Certain types of play emerge earlier than others. In early intervention and with very young children, I first see sensory motor or exploratory play, with tactile and oral-motor exploration. Most infants learn about their environment by mouthing and touching objects, and that is often their first introduction to different kinds of play.

They gradually move into cause-and-effect play, trying to make an impact on the environment. If I press this button, a song plays; if I press another, the lights turn on. Through this, they learn how their actions create outcomes. Physical activity play follows and spans structured and unstructured forms, indoors and outdoors, including rough-and-tumble play. Children might climb trees, swing freely, or participate in structured activities like judo or karate, which are still physical activity play but with defined rules.

I then consider pretend play, which is dramatic and may include rules that shape the narrative. Dungeons and Dragons is a useful example often played by adults, built around an elaborate make-believe universe with explicit guidelines. I differentiate pretend play from symbolic play, although some literature treats them as synonymous. I use symbolic play to describe using objects to represent real-life items. A child may start by using a toy phone to make a call, then progress to using a banana as a phone, shifting from concrete to more abstract symbolism. Pretend play builds on that symbolism by expanding roles, scripts, and storylines. The child might pretend to place a food order on the “phone,” mirroring what they have seen at home.

Finally, I look at social play, which often begins with parallel play—children playing next to each other without direct interaction—and then moves toward associative and cooperative play. Children coordinate, share goals, and follow rules through team sports, board games, and other group activities at that stage.

Play Scheme

Another term I use that comes from Piaget’s literature is play scheme. A play scheme can evolve and often involves imagination. The key feature is shared reference points among the players—understandings that make perfect sense to those inside the game but may be opaque to an outsider.

In my own practice, when I worked in a kindergarten setting, my friends Jake, Tony, and Daphne ran a food shop on the play yard. They used plastic food and fake money, and I would “buy” eggs and milk. One day, they remodeled their shop into an iPhone store without announcing it to me. As the outsider, I missed the shift and asked for bread. They looked at me, slightly pitying, and explained that iPhone stores don’t sell bread. Inside their play scheme, the overhaul was obvious and coherent; to me, it wasn’t. This is precisely the capacity I assess when observing children’s play—the ability to generate, maintain, and flexibly revise shared play schemes, and to coordinate those changes with partners through implicit cues and negotiated rules.

Why Is Play Important?

Shifting gears, I want to delve into the literature and highlight why play matters. I often point to a 2018 American Academy of Pediatrics article on the power of play. It offers a thorough look at how play develops and how it supports learning, social skills, self-regulation, and executive functioning. The authors also describe anatomical and physiological benefits, including brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) stimulation, which is crucial for memory and social learning. They report that children who engage in at least an hour of play daily show stronger creative thinking and multitasking, along with broad physiological benefits across immune function, bone development, and the cardiorespiratory system. The paper goes so far as to encourage pediatricians to write a “play prescription” during well-child visits to support developmental milestones in infants and to promote overall well-being in children.

I also keep a global frame in mind. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child recognizes play as a fundamental right, not a privilege. While the United States has not ratified the convention, and many ratifying countries still struggle to prioritize play in practice, I find it encouraging that the global community explicitly acknowledges play’s importance. For me, this literature and policy context underscore that play is not optional; it is a cornerstone of healthy development.

OT's Journey With Play

Next, I want to reflect on our profession’s journey with play, which has been somewhat uneven over the decades. Jean Ayres’ sensory integration work positioned play as a means within sensory integration therapy. Mary Reilly and her students then deepened our understanding of play’s role; in Play as Exploratory Learning, Reilly described how play offers opportunities to learn and to achieve mastery, and she proposed hierarchical stages of play development. Her group contributed some of our earliest assessments, including the Knox Preschool Play Scales and Takata’s Play History.

By the late 1990s, I witnessed a paradigm shift toward more biomedical, technique-focused interventions, and play receded into the background as those approaches took center stage. The pendulum began to swing back through the work of Anita Bundy and colleagues, who revitalized attention to play and play skills. At the same time, occupational science was gaining momentum, placing play at the heart of human occupation and emphasizing its contribution to health and quality of life. That perspective supported the development of additional tools such as the Test of Playfulness and the Test of Environmental Supportiveness, and it nudged us to analyze not only individual skills but also how environments enable or constrain play.

In recent decades, the neurodiversity movement has challenged me to examine play through a neurodiverse lens. Students and colleagues who identify as autistic have shared experiences of being told they were “not playing right,” and the frustration that followed. I take that as a call to foreground choice and autonomy as core features of valid play. If someone prefers to participate as an onlooker rather than an active partner, I honor that stance as legitimate within their play profile. That does not mean I stop supporting the growth or expansion of their play skills; it means I respect their preferred modes of engagement and build from there.

OT and Play

There have been many studies examining how therapists view play and how they use it in practice. Across regions, therapists consistently recognize the positive influence of play on health and wellness and identify it as the primary occupation of childhood. Many report using play in therapy, yet comparatively few assess play directly or write explicit play goals. I used to be one of those therapists. As I mentioned earlier, I focused heavily on self-care, behavior, and other domains, and I wrote very few play goals.

The literature increasingly centers children’s perspectives on play—what they enjoy, where they feel successful, and how they define meaningful participation. Anita Bundy, the 2024 Eleanor Clarke Slagle lecturer, focused her lecture on risky play, consistent with her research trajectory. A recent study by Raymond Tolan in the Journal of Occupational Therapy Education examined how pediatric OT faculty address play in their programs. The study found that 98% include play in lectures, 88% use videos of children at play, and about 84% facilitate in-person observations. As a pediatric OT faculty member, I fall into all three categories. I teach about the development and benefits of play, assign a play-themed scavenger hunt, regularly use video exemplars, and take students to learning centers and child development facilities for direct observation.

Play Evaluation & Outcomes

Next, we will discuss play evaluation, outcomes, and goal writing.

Play Evaluation

When I conduct any OT evaluation, I aim to capture a complete picture of the child’s occupational performance and the family’s routines—the whole picture. Because I consider play a primary occupation of childhood, I make sure to assess play directly. I don’t rely solely on play-based tasks to infer motor or cognitive skills; I also gather information about the child’s play—its form, meaning, motivation, variety, and quality.

This helps me plan interventions that target that child's most meaningful and satisfying occupations. The goal of a play assessment is not only to understand the child’s play but also to see how play fits into their overall life and to learn about the environments in which their occupations unfold. By documenting participation and context, I can tailor supports that honor the child’s preferences, leverage strengths, and address barriers in natural settings.

OT Evaluation Process

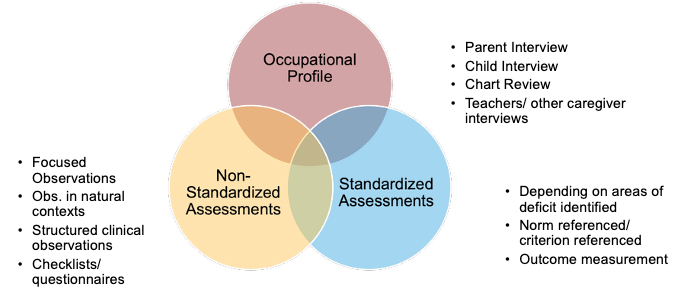

I wanted to share this diagram in Figure 5 because this is how I teach the OT evaluation process to my students in an evaluation class.

Figure 5. OT Evaluation Process. (Click here to enlarge this image.)

I organize the evaluation process into three broad buckets. First, I develop the occupational profile by collecting information about the child and family. I do this through parent and child interviews, chart reviews, and conversations with other adults in the child’s life, such as teachers and caregivers, to build a well-rounded picture.

Next, I use nonstandardized assessments. In pediatric settings, I often rely on focused observations, observations in natural contexts, and clinical observations because standardized testing can be challenging to administer meaningfully in many environments. I also use checklists and questionnaires to understand what happens within daily routines.

Finally, I incorporate standardized assessments as indicated by areas of concern identified earlier in the process. I select norm-referenced or criterion-referenced tools and appropriate outcome measures to inform my understanding and to support goal setting.

1. Occupational Profile

In my practice, I begin with the occupational profile. It includes several sections, and I focus on those that yield rich insights into a child’s play skills. When I collect information about occupations in which a child feels successful or limited, I capture that specifically in relation to play. I ask what kinds of play the child feels confident about and where they feel they need more support or practice.

With autistic children, I often see an extreme focus on a single topic—dinosaurs, for example—where they feel highly competent. Yet, they may not feel as successful in group games or board games with peers. Using the occupational profile to gather that detail helps me identify where to target play skill development.

I also look to the occupational history to understand how play has been approached over time—by the child and the family—and to clarify the family’s interests and values. Some families prioritize outdoor activities like hiking or camping, which can be meaningful opportunities for a child to explore play in natural environments. I pay close attention to environmental supports and barriers. Some parents deeply value play but live in areas where sending children outside isn’t always safe or feasible. I consider performance patterns—the child’s and the family’s habits and routines—and where play fits within them.

Some time ago, when I worked in a preschool setting, I supported a four-year-old whose schedule was extremely packed. He attended our special education preschool, a mainstream preschool, received 20 hours of ABA, and had additional occupational and speech therapy services outside of school. His day was completely packed. During his IEP meeting, we asked his parents what he did for fun and when he played. After a pause, his mother said, “Jeff doesn’t really get any time to play.” It was a sobering moment that illustrated how a tightly structured day can crowd out the intrinsic, free play we want children to experience.

Finally, I examine client factors to understand what supports or intimidates play. I won’t go through each question word for word, but I use guiding questions like these to systematically evaluate a child’s play.

Questions to Examine Play

These are questions I can ask parents, teachers, and other caregivers. I can ask the child about some directly. I also consider several of these questions during observations to form a clearer picture of the child’s play.

2. Non-standardized methods

Non-standardized methods and direct observation of play are essential in my approach. I try to watch a child during routine activities. I observe recess, free play, and PE in a school setting to understand how they engage. When given a choice, do they gravitate to solitary play—like the sandbox—or do they join a group game with friends? As an OT, I adapt these observations to the setting.

In early intervention, I look at how the child explores different play activities, what play opportunities parents provide, and how those activities support bonding and attachment. I consider what the child can do and what they want to do, and I note when motor impairments or other factors limit participation in desired activities.

In a preschool several years ago, I evaluated a child who had just entered the program at age three with a significant cognitive disability. When presented with toys, he consistently swiped them off the table. On the surface, it looked like “behavior,” but a closer look suggested he didn’t know what to do with those toys. They were likely too advanced for his current play skills, and the swiping reflected where he was developmentally rather than defiance.

During observations, I pay attention to how the child interacts with peers, adults, and the environment. In an outpatient clinic with a large gym and extensive gross motor equipment, it’s straightforward to see how they navigate and engage with big equipment. In other settings, I adapt my methods to fit the context while maintaining the same focus on meaningful, functional play.

What can we learn from an informal play assessment?

When I conduct informal play assessments and observations, I gain a nuanced picture of a child’s play skills, their interaction with the environment, and key aspects of physical, cognitive, and social development. I look closely at social participation: how the child understands their role within different play activities, how they perceive the roles of others, and whether they can engage in turn-taking and sharing. I pay attention to imagination, independence in play, and the presence of internal control and motivation. I ask myself whether the child is initiating and directing play or primarily following cues from adults and the environment.

Play also reveals coping skills. With older children—fourth or fifth graders, for example—I often use board games to observe how they manage frustration and loss. Do they tolerate defeat, continue playing, or flip the board? These moments offer clear insight into social–emotional development.

Environmental context matters as much. In one preschool classroom with many children diagnosed with autism, teachers repeatedly told me the kids did well during circle time and structured worksheet tasks but struggled during free play. The unstructured nature of that time left them unsure how to proceed. When I assess a child in such a classroom, I observe during free play to see what happens when structure drops away—how the child navigates choices, engages with peers, and responds to the ambiguity of an open-ended environment.

3. Standardized Assessments

Finally, when I consider standardized assessments, I keep in mind that there are many options, and this is by no means a comprehensive list. I find that many of these tools are used more in research than in day-to-day practice. Most are criterion-referenced, with a few norm-referenced, and each can be applied flexibly across settings depending on the child and the evaluation goals.

When I send my OT students into child development centers or preschools, I often have them use the Knox Preschool Play Scale to structure their observations and gather systematic information about play. I also draw on newer tools, such as the Test of Environmental Supportiveness, which provides valuable insight into how the child, their environment, and their play interact. These measures help me pair structured data with clinical observations to form a more complete picture of the child’s play profile.

Purpose of Play

Before I move into interventions and goal setting, I want to step back and center the purpose of play. My goal in designing interventions or writing goals is not to make a child look as typical as possible. It is to help the child feel successful, engaged, and proud of their actions, and build on intrinsic motivation. Everything I plan supports authentic engagement and meaningful participation in play.

Play Outcomes

When I turn to the OTPF-4, I think in terms of the broad outcome areas it recognizes: improving occupational performance and function, prevention, health and wellness, quality of life, participation, role competence, well-being, and occupational justice. Within these, I can write play-related goals that align with the larger outcome while staying meaningful for the child and family.

From a developmental lens, I use the child’s current play stage as the starting point and shape goals that scaffold to the next level. I build toward associative or cooperative play if a child engages in parallel play. If they’re primarily exploring objects, I may target cause-and-effect play next. I also write caregiver-centered goals—especially in early intervention—to expand play opportunities at home, diversify the child’s play repertoire, and support caregiver confidence in facilitating play.

When I need more quantifiable goals for progress monitoring or reimbursement, I operationalize play performance. I might target the duration of engagement in a chosen activity, gradually increasing from five minutes to ten and beyond during free play. I measure discrete social–play behaviors such as the number of reciprocal turns taken, the number of play partners engaged, or adherence to simple play rules. I also include goals around reading social cues and being a “good player” so the child experiences competence and success during play. Across all of these, my focus is on functional gains and authentic participation, using data to track growth while keeping the child’s intrinsic motivation at the center.

Play Intervention

In the following section, we will talk a little bit about play interventions.

Play: As An End & Means

As I’ve mentioned, many of us are skilled at using play as a means, but here I’m emphasizing play as an end. I routinely use activity analysis to embed play in skill development—using playful tasks to support handwriting, strengthen bilateral integration, or offering play as a reward after nonpreferred activities. In contrast, when I use play as the outcome, I focus on the child’s intrinsic motivation, internal control, and freedom of choice.

Consider playdough, as in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Examples with playdough.

When I hide small objects in the dough and ask a child to find them, I’m using playdough as a means—targeting pencil grasp, finger strength, or bilateral skills. When I offer multiple colors and invite the child to make whatever they want, I use playdough as an end. The goal shifts from fine-motor outcomes to creativity and self-direction; no external rules exist, and the child’s choices drive the activity.

The same distinction applies to an obstacle course (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Examples with obstacle courses.

If I design the course to address motor planning, core strength, or proximal stability, I use it as a means. If I provide equipment and invite the child to set up their own course or use the materials however they wish, I’m using it as an end. In that case, I’m not prioritizing whether they select tasks that build core strength; I prioritize agency, exploration, and engagement.

Some activities can serve both roles. With LEGO bricks (Figure 8), I might avoid providing a model to copy and instead encourage the child to build whatever they imagine—perhaps a house that becomes a springboard for pretend play.

Figure 8. Example with LEGOs.

In doing so, they naturally practice pincer grasp and in-hand manipulation while exercising creativity and maintaining internal control. Twister is another example shown in Figure 9: children work on motor planning and core strength as a means, but the actual outcome is enjoyment—playing with siblings, trying to win, laughing, and “joshing around.”

Figure 9. Example with Twister.

In each case, I decide whether to prioritize skill acquisition through play or authentic, self-directed play as the outcome—and often, I purposefully capture both.

Play as an Occupation

When I use play as an occupation, my role is to make play truly available. I draw on the information I’ve gathered about a child’s play—strengths, areas for skill building, preferences—and then directly support those play activities. I hold onto what my students reminded me: all play is right. I’m not trying to make a child appear as typical as possible; I’m meeting them where they are and honoring their authentic engaging ways.

I rely on the therapeutic use of self—my presence, voice, affect, and facial expressions—to infuse interactions with playfulness. Hence, the child feels engaged and experiences that suspension of reality. I also look beyond individual sessions. I think about how to consult and advocate for play within the systems around the child—classrooms, clinics, and community settings—so play opportunities are embedded across the day, not just during direct treatment.

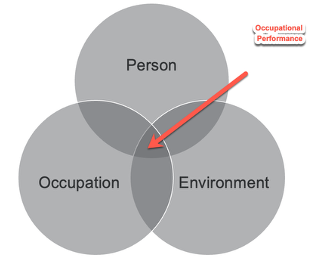

PEO Model

I thought of organizing all that information using our PEO model (Figure 10)and then looking at different persons, occupations, and environmental factors that we can use to play as an occupation.

Figure 10. PEO model.

Person Factors

When I think about person factors, I look for ways to adapt toys to be accessible to children with diverse abilities—switch-activated toys, joystick controls, textured materials, and other access methods that invite engagement. In a school setting, I might provide an adapted toy so a child can join peers during free play, and then consult with teachers and instructional assistants to model how the child can use that toy alongside classmates to be included in different activities.

Parent coaching is central, especially in early intervention. Because I play with children all day, some of this feels intuitive to me, but it isn’t always intuitive for parents. I explain why play matters and demonstrate concrete ways to play with their child—building on the child’s interests, supporting turn-taking, and expanding play sequences. I draw on programs like Project ImPACT, which primarily targets communication but also supports the development of play skills and helps parents become more confident play partners. During sessions, I narrate my actions so parents understand what I’m targeting and can try it themselves.

I’ve had to do this kind of education with families whose children have hectic schedules. With Jeff’s family, for example, his parents were doing everything they could—multiple therapies, schools, structured activities—but he had no time for free play. I worked with them to reframe free play as essential, not optional, and to make space for it. I prioritize respecting neurodivergence, meeting children where they are, finding the just-right challenge, and keeping play as the end goal: authentic engagement, agency, and joy.

Environmental Factors

When considering environmental factors, I look for ways to make playgrounds accessible for children of all abilities. I’ve seen and supported examples of OTs partnering with local governments and city councils to design or retrofit inclusive play spaces. I encourage this kind of systems-level advocacy whenever possible.

I also consider introducing play in settings where it isn’t typically prioritized but is essential for child and family well-being—transition centers, homeless shelters, and hospital environments. I’ve mentored capstone students on both fronts: some collaborated with city councils to improve playground accessibility, while others worked in a transitional living facility to create family playgroups as a co-occupation, inviting all family members to participate and connect.

Sensory-friendly public spaces are another critical shift. Museums, libraries, and even airports are beginning to offer sensory-aware design. In Portland, where I live, the airport’s renovation included a sensory-friendly space for kids, and it has been a welcome addition for many families.

Beyond environmental supports, I use task modifications to increase access to play. Simple adjustments—like printing the rules of a game for everyone, not just the child I’m supporting—normalize supports and reduce stigma. I also draw on the growth of outdoor therapy, using nature-based play both as a means to build specific skills and as an end in itself—supporting autonomy, joy, and meaningful participation in the outdoors.

Occupational Factors

As an OTP, I lean on adaptations and universal design to make toys accessible for everyone. I consider motor, sensory, cognitive, and perceptual demands and adjust materials or instructions so a broader range of children can participate.

I also draw from intervention programs that center play. DIR/Floortime, for example, uses play both as a therapeutic medium and as the end goal, with explicit play-focused objectives embedded in sessions.

In schools, I advocate for policies that protect play. I push back when recess is removed as punishment; children need unstructured free play for regulation, social development, and learning. I also speak up during budget discussions to support PE and adapted PE. Academic achievement isn’t the only outcome that matters—children learn through movement and play, and PE/APE provides essential opportunities.

Beyond the classroom, I support community play infrastructure: day camps and summer camps for children of all abilities, inclusive community play programs, and collaborations with cities and local governments to expand safe, outdoor play spaces.

Resources

I’ll close with a short list of national and global resources that I find useful for deepening practice around play. I’m not affiliated with any of these organizations:

- American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA) resources on play and pediatrics

- International Play Association (IPA)

- KaBOOM! (Playground access and equity)

- UNICEF Child-Friendly Cities Initiative

- Tinkergarten and similar nature-play programs

- Local and state Adapted PE associations for school-based collaboration

These are resources I’ve found helpful as both a practitioner and educator, and I want to share them. The first is a new AOTA community of practice focused on the occupation of play—a group of clinicians meeting every other month to discuss experiences and strategies for promoting play across settings. Information is available on AOTA’s website.

AJOT recently published a special issue on play in 2024, with strong research articles and reflections on where our profession currently stands regarding play—from biomedical approaches back toward a more occupational lens. I leaned heavily on several of those pieces for this presentation. I also look to the Journal of Play in Adulthood, which underscores that play isn’t only for children and highlights its relevance for mental health and well-being across the lifespan.

Additional organizations I use include the National Institute of Play, the International Play Association, and the US Play Coalition, all of which offer excellent materials. For inclusive play spaces, I’ve appreciated the work of nonprofits such as Harper’s Playground, which my capstone students have partnered with to develop inclusive Playgrounds, and AS Play Corps, which pursues similar goals.

Main Takeaways

My main takeaways are central and straightforward to practice. Play is the primary occupation of childhood, and I need to treat it as an end—something I intentionally evaluate and target in intervention, not just a vehicle for other skills. I commit to building play skills and making play accessible for children of all abilities, working at individual and system levels to remove barriers and expand opportunities. My references are available as a separate handout with links to the articles I cited.

Questions and Answers

What is considered “risky play?”

Risky play involves allowing children to take manageable risks during play to build confidence, problem-solving, and motor skills. Drawing on Anita Bundy’s perspective, it’s about stepping outside the box while promoting general safety—encouraging children to try challenging activities rather than “bubble wrapping” them. Examples include supervised use of tools (like a drill or hammer) in outdoor or nature-based therapy, with explicit instruction on safe use.

How do we balance safety with encouraging risk?

Maintain clear safety guidelines and close supervision while intentionally offering challenging, age-appropriate activities. Teach and model safe tool use, set boundaries, and scaffold skills—so children experience challenge without unnecessary hazards.

What about bullying during play?

Preventing bullying may require more adult facilitation, especially with neurodiverse children who may have difficulty recognizing bullying. Many schools use tiered, school-wide anti-bullying frameworks that emphasize prevention for all students, not just corrective measures after incidents. Embedding instruction in social cues, turn-taking, rule-following, and group participation can reduce bullying by improving children’s ability to engage successfully in group play.

Does the Knox Preschool Play Scale (KPPS) need to be purchased? Where can I get it?

The KPPS is not published as a standalone scale. It appears in Parham and Fazio's book “Play as an Occupation” (2nd edition). You can order that book (e.g., by searching for “Play as an Occupation Parham Fazio”), and the scale within can be photocopied and used in practice per the book’s guidance.

How do you write a play-based goal?

Tailor goals to your setting’s requirements:

- Early intervention: Include child goals (e.g., expand symbolic play) and caregiver goals (e.g., increase daily play opportunities).

- School-based: Focus on inclusion in varied play activities and participation with peers.

- When quantitative metrics are required, make goals measurable, for example:

- Increase independent play duration from 3 to 8 minutes across 3 consecutive sessions.

- Participate with at least 2 peers during recess play for 2 structured games per week.

- Take 4–5 turns during a board game in 3 of 4 sessions.

- Engage with 3 different pieces of play equipment during a 10-minute Playground period.

These approaches keep goals functional, measurable, and aligned with context and child needs.

References

See additional handout.

Citation

Gadkari, S. (2025). Play and playfulness: Intentional integration in everyday practice. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5830. Retrieved from https://OccupationalTherapy.com