Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Trauma Informed Care: What Does An Occupational Therapy Practitioner Need To Know?, presented by Aditi Mehra, DHSc, OTR/L.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to identify basic principles of trauma and trauma-informed approaches.

- After this course, participants will be able to recognize the impact of trauma on the brain and human behavior.

- After this course, participants will be able to list 6 trauma-informed strategies recommended by the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors (NASMHPD).

Introduction

Today's topic is close to my heart. Trauma in various forms is applicable to almost everybody.

The Term "Trauma"

History

- American Civil War

- Soldier's heart

- Shell shock

- Battle fatigue

The term "trauma" finds its origins in the Greek word for wound. While initially applied in the context of physical injuries, our contemporary understanding recognizes that trauma extends far beyond the physical realm. We acknowledge that a traumatic event can imprint emotional scars that persist long after physical healing has occurred.

Reflecting on the origins of occupational therapy (OT), its establishment during World War I marked a crucial period. In its early stages, OT primarily concentrated on mental health initiatives. This emphasis has undergone a shift, although mental health remains a central focus. During this era, many American soldiers returning from the war grappled with what we now identify as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), colloquially known as being "shellshocked." OT emerged as a field providing reconstructive aids to mitigate the trauma experienced by these individuals.

Until approximately the 1950s, mental health was a prominent area of practice for occupational therapists. Subsequently, due to various legislative changes and a lack of advocacy, mental health-focused OT roles dwindled. This led to a notable shift towards a rehabilitation and medical model within the occupational therapy profession, a trend that persists today.

Definition

The definition of trauma, to be precise, is a singular accumulative experience that results in an adverse experience or results in an adverse functionality. It can be mental, physical, and spiritual.

Types of Trauma

- Acute

- A single traumatic event that is limited in time

- Chronic

- Prolonged/ repeated distressing events that span months or years.

- System Induced

- Displacement from home environment: protective custody, institutionalization, etc.

- Complex

- Multiple distressing events may or may not be intertwined

Trauma manifests in various forms, extending beyond mere physical or emotional distress. Four primary types:

1) Acute Trauma involves an immediate emotional response to a single traumatic event, leaving an impact during and shortly after the occurrence.

2) Chronic Trauma is marked by prolonged exposure to repetitive traumatic situations, leading to cumulative effects over an extended period.

3) Complex Trauma comprises multiple layers and complexities, with intertwined or parallel traumatic events occurring from different directions.

4) System Abuse represents a broad, overarching form of trauma experienced by groups, such as refugees, on a systemic level.

It's crucial to recognize that trauma is a profoundly personal experience. Two individuals exposed to the same environment can develop vastly different perspectives on their shared upbringing. This diversity highlights that no two people interpret or cope with experiences in the same way. Acknowledging the profound impact of trauma is essential, as many individuals may unknowingly carry its effects, considering their coping mechanisms have become ingrained neural pathways, shaping their perception of what is considered normal.

Examples

Trauma takes various forms, and it's crucial to recognize that not all traumatic experiences are overt. Microaggressions, often overlooked, constitute a significant form of trauma, particularly for individuals in historically marginalized groups. These subtle and indirect instances of discrimination, whether racial or otherwise, may seem insignificant individually but can accumulate, akin to constant mosquito bites leading to infection, inhibiting one's ability to function. It's crucial to understand that the term "micro" doesn't diminish its impact.

Beyond microaggressions, numerous other forms of trauma include natural disasters, such as earthquakes, floods, or wildfires, resulting in traumatic experiences. Bullying is a pervasive issue that doesn't necessarily cease in adulthood, manifesting in various settings like workplaces or families. Displacement involves forced relocation, disrupting one's sense of stability. Food insecurity, particularly impactful for children like refugees or those in foster care, can lead to challenges related to food access. Abuse encompasses physical, emotional, or psychological harm inflicted by others. Neglect involves failing to provide necessary care, attention, or support, leading to emotional distress. Sexual assault is an unfortunately common traumatic event with severe emotional and psychological consequences. Terrorism involves acts of violence or threats designed to create fear and distress within a community.

Understanding the diverse nature of trauma is vital for creating a more empathetic and supportive environment.

Evidence

- Traumatic experiences are relatively common occurrences among clinical and general populations (Smith et al., 2016)

- Physical illness, disease, and disability (Felitti and Anda, 2010)

- Hoysted, Jobson, and Alisic (2019) RCT: Those who received the training demonstrated significantly greater knowledge in trauma-informed care than did the control group at follow-up and reported high satisfaction with the training

- These findings document a progression toward feasible and effective means of training medical staff in trauma-informed principles and practices

The evidence highlights that traumatic experiences are prevalent not only in clinical populations but also among the general public. While individuals seek medical attention for physical ailments like tennis elbow, the impact of trauma may subtly influence treatment plans and interactions. Furthermore, research indicates that trauma can contribute to physical illnesses, disabilities, and diseases, potentially exacerbating existing conditions.

A notable study conducted by Hoysted Jobson and Alisic in 2019 adds valuable insights. The randomized controlled trial focused on training emergency department nurses and physicians in trauma-informed care through a 15-minute online session. The group that underwent the training exhibited significantly higher knowledge of trauma-informed care principles during follow-up compared to the control group. Additionally, they reported greater satisfaction and increased confidence in handling related scenarios. This study underscores the effectiveness and importance of trauma-informed care training in enhancing professionals' capabilities and understanding.

Barriers to Trauma Informed Care (TIC)

- Decreased competence surrounding TIC

- Execution

- Being fearful of re-traumatizing individuals

- Time constraints

- Needing more training in TIC

(Bruce et al., 2018)

Certainly, there are various barriers to implementing trauma-informed care. It's crucial to recognize these obstacles when introducing new strategies. One significant barrier is a lack of competency or awareness regarding trauma. If professionals are not well-versed in the nuances of trauma, they may struggle to identify and address it appropriately. Another hurdle is the execution of knowledge gained through training. Simply acquiring information is insufficient; professionals must actively incorporate trauma-informed practices into their routines.

A prevalent fear is the possibility of re-traumatizing individuals when their trauma is known. Therapists, prioritizing the principle of doing no harm, must navigate this concern delicately. The time constraint is also a substantial barrier, as professionals often face limited time to delve deeper into patients' health histories, engage with team members, and integrate trauma-informed care into their practice. Lastly, inadequate training becomes a barrier itself, emphasizing the need for comprehensive education to equip professionals with the necessary skills for trauma-informed care.

The Impact of Trauma

- Mental health and functional difficulties

- Health risk behaviors

- Higher rates of heart disease, stroke, liver disease, and lung cancer

- Increased chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and autoimmune disorders as compared to the general population (Oral et al., 2016)

- Disassociation and increased autonomic reactivity

The impact of trauma is profound and far-reaching, affecting various aspects of an individual's well-being. Traumatic experiences trigger rewiring in the brain, creating lasting patterns that significantly influence the nervous system. This rewiring alters how the brain processes information, impacting memory, moods, emotions, feelings of safety, and overall mental health. Individuals who have experienced trauma often find themselves in a heightened state of alertness.

The consequences of trauma extend beyond mental health, manifesting in deleterious physical conditions and health risk behaviors. Research indicates elevated rates of heart disease, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary issues, and other health complications among those who have experienced trauma. The increased autonomic reactivity resulting from trauma plays a crucial role in exacerbating health-related challenges, creating a complex interplay between traumatic experiences and overall health. The effects of trauma are both salient and insidious, leaving a lasting imprint on individuals' lives.

How Does Trauma Impact Children?

- Psychologically

- Behaviorally

- Academically

- Decreased concentration

- Irritability/worry

- Conduct problems

- Substance abuse

- Socially

Children who experience trauma may encounter a range of challenges that extend beyond the immediate psychological impact. The effects can manifest in various domains, affecting their psychological well-being, behavior, and academic performance. For instance, children exposed to stereotypes or societal expectations that clash with their individual experiences may develop feelings of inadequacy and struggle academically. These experiences contribute to a form of trauma, influencing their self-perception and hindering academic success.

The consequences of trauma in children often include decreased concentration, as imperfect neural pathways form due to their traumatic experiences. Additionally, children may exhibit symptoms such as anxiety, irritability, and worry, further complicating their emotional and behavioral well-being. Conduct issues may arise as a response to these challenges, and in some cases, trauma can contribute to substance abuse as a coping mechanism. Social aspects of a child's life may also be impacted, as they grapple with unresolved trauma and attempt to navigate their emotional well-being. Recognizing and addressing trauma in children is crucial for providing effective support and interventions.

Complex Childhood Trauma

- When trauma occurs frequently or for long periods of time, especially in the absence of safe adult relationships, it is referred to as complex trauma.

- Complex trauma dysregulates the neurological stress response system at varying levels.

- It can alter the structure and function of the amygdala, prefrontal cortex, and hippocampus.

(Dowdy et al., 2022)

Childhood trauma encompasses various adverse experiences, as defined by the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) framework, which examines the impact of factors like physical, sexual, and psychological trauma on children. Complex trauma, often characterized by prolonged exposure to adverse events, exerts a dysregulating influence on the neurological system. The degree of stress response varies based on factors such as the child's age during exposure, the type and duration of trauma, and the presence of supportive caregivers mitigating the effects.

Complex trauma, particularly when occurring during critical developmental periods, can induce structural and functional alterations in key brain regions, including the amygdala, prefrontal cortex, and hippocampus. These changes, documented in the literature, are associated with the development of maladaptive conditions and contribute to various health impairments. Understanding the nuanced impacts of complex trauma on the developing brain is essential for devising effective interventions and support systems for affected children.

Statistics on Trauma

- More than 2/3 of children reported at least 1 traumatic event by age 16.1

- 1 IN 4 high school students were in at least 1 PHYSICAL FIGHT

- 1 in 5 high school students was bullied at school; 1 IN 6 experienced cyberbullying

- 19% of injured and 12% of physically ill youth have post-traumatic stress disorder

- More than half of U.S. families have been affected by some type of disaster (54%)

- The national average of child abuse and neglect victims in 2013 was 679,000, or 9.1 victims per 1,000 children

Trauma statistics paint a somber picture, revealing the widespread prevalence and early onset of traumatic experiences. More than two-thirds of children report experiencing at least one traumatic event by the age of 16, highlighting the distressing reality many young individuals face. High school environments also contribute to trauma, with one in four students involved in physical fights, one in five experiencing bullying, and one in six facing cyberbullying.

The impact on mental health is alarming, as 19% of injured and 12% of physically ill youth develop PTSD. Additionally, over half of U.S. families have encountered some form of disaster, further contributing to the prevalence of trauma. Disturbingly, the national average for child abuse and neglect victims in 2013 was 9.1 victims per thousand children, underscoring the pervasive nature of this issue. Recognizing these statistics is crucial, especially when working with clients from diverse backgrounds, as trauma is a global concern affecting individuals worldwide.

3 Streams of Symptoms

- Re-experiencing the event

- Psychological rigidity

- Hyper-arousal & Hypo-arousal

There are three streams of symptoms when you have trauma.

Re-experiencing the Event

- This is the hallmark of trauma:

- Nightmares

- Rumination of the past

- Guilt

- Shame

- Sadness

Re-experiencing the traumatic event is a hallmark of trauma, often characterized by persistent rumination and mental revisitation of the incident. This aspect is prominently featured in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a condition familiar to many through depictions in movies. Individuals grappling with trauma may endure nightmares, guilt, and vivid, real-life sensations associated with the traumatic experience, illustrating the psychological rigidity and distressing hyper or hypo-arousal responses that can accompany re-experiencing.

Psychological Rigidity

- I'm stupid.

- I'm a loser.

- I'm worthless.

Psychological rigidity, a consequence of trauma, manifests as becoming entangled in negative self-narratives stemming from past experiences. Individuals may latch onto self-limiting beliefs, such as feeling unintelligent, unworthy, or destined for failure based on their history. This rigidity can profoundly influence daily functioning, impacting choices, limiting opportunities, and hindering personal growth. The effects may not always manifest overtly in activities of daily living but can subtly influence behaviors, such as avoiding social connections due to past challenges. Recognizing the interplay between psychological rigidity and trauma is crucial in understanding how they collectively contribute to impairment.

Hyper/Hypo Arousal

You are probably familiar with the hypo and hyper-arousal states that most of us know from the sensory system. Figure 1 shows an overview.

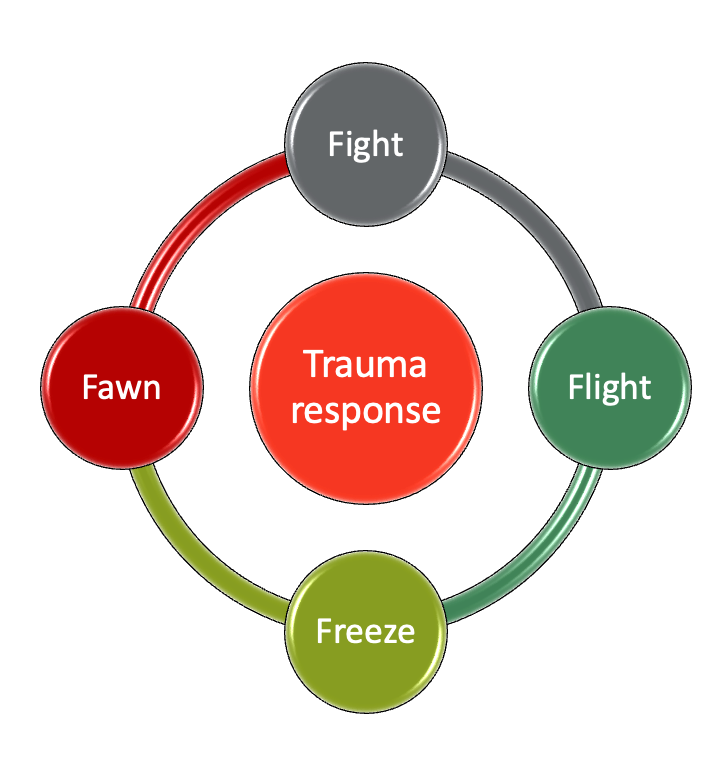

Figure 1. Overview of the trauma response.

In addition to the commonly known fight and flight responses, trauma can elicit the freeze and fawn responses. The freeze response involves the activation of the dorsal vagal nerve, leading to a state of immobilization where the individual collapses or becomes stuck, appearing spaced out and unable to move. On the other hand, the fawn response is characterized by people-pleasing behavior and a strong aversion to conflict. Individuals in a fawn response mode tend to avoid setting boundaries and saying no, driven by a deep-seated desire to prevent conflict triggers that may activate traumatic responses. These responses may not always manifest overtly in functional impairment but can subtly influence behaviors and interpersonal dynamics.

Trauma and 4 Processes

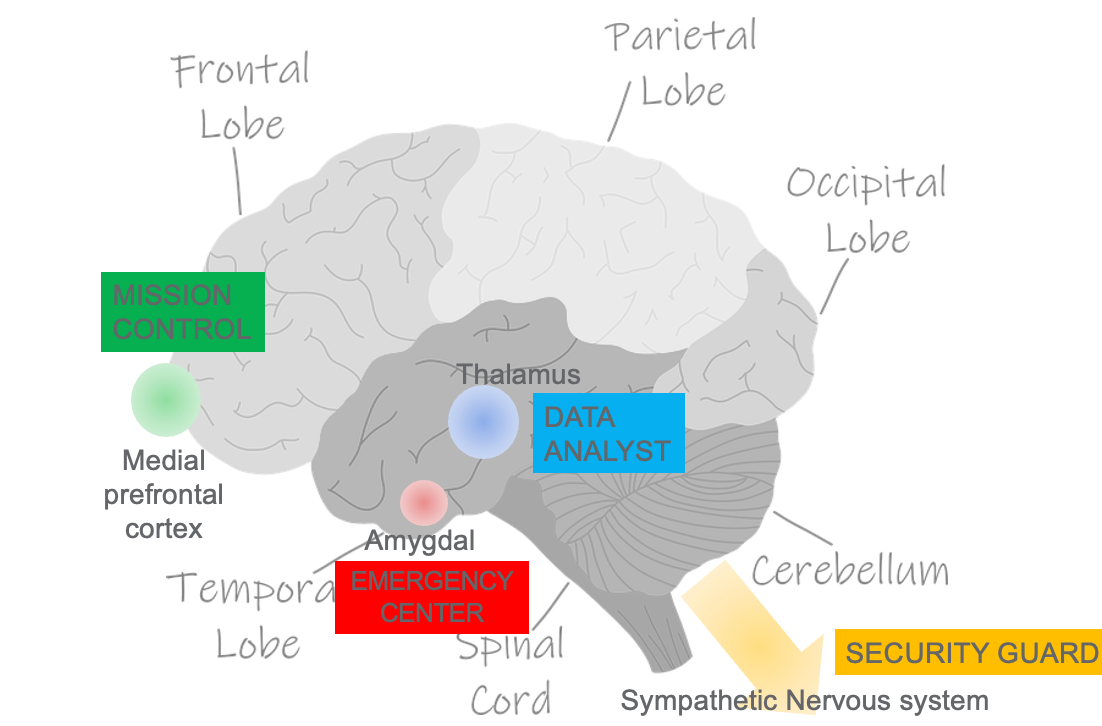

Dr. Russ Harris talks about four processes in the brain, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Brain with the four processes highlighted.

The thalamus serves as a crucial relay station for sensory information, integrating data from various senses before transmitting it to the brain. The processed information is then directed to the amygdala, often referred to as the brain's emergency center, and subsequently to the cerebral cortex, known as mission control. Additionally, the sympathetic nervous system, akin to a security guard, sends signals to the spinal cord and the rest of the body, facilitating appropriate responses to the perceived threat or situation. Understanding these components provides insight into how trauma can impact different areas of the brain and influence an individual's cognitive and physiological responses.

What Happens When We Flip Our Lids?

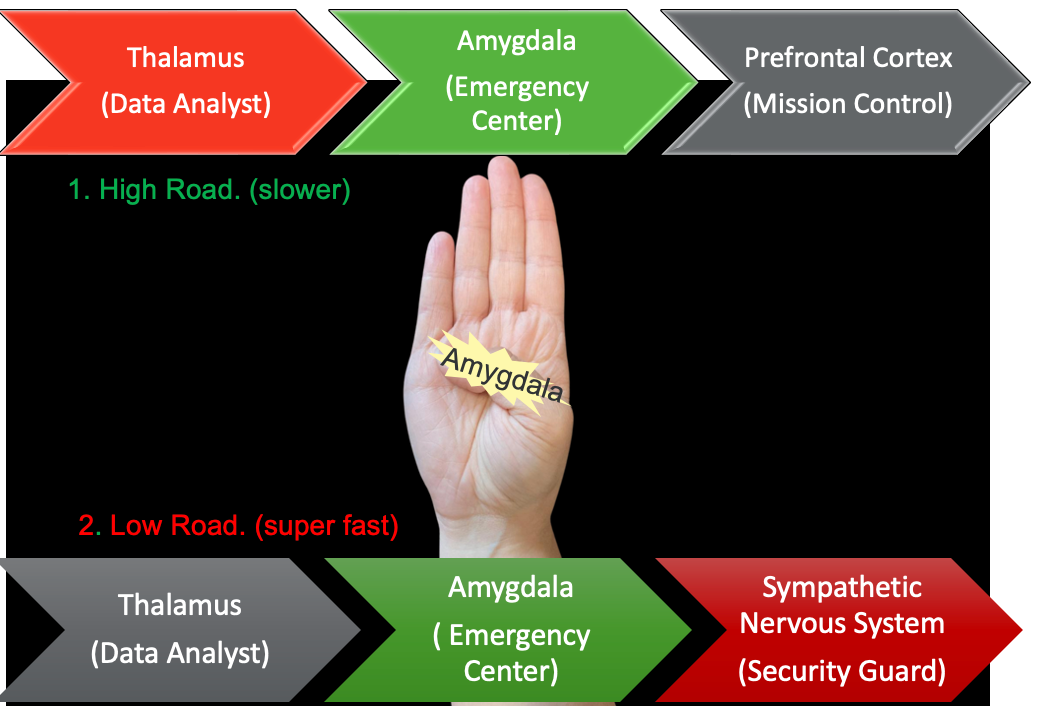

Let's take a look at what happens when we have a traumatic event. Figure 3 shows an illustration of what happens.

Figure 3. An overview of the four systems during a traumatic event.

The thalamus, acting as the brain's data analyst, bifurcates the transmission of information into two pathways. The low road, a swift route, sends a rapid message to the amygdala, the emergency center, triggering an alarm that signals potential danger. This primal response, rooted in survival instincts, prompts the amygdala to alert the sympathetic nervous system, the brain's security guard, about the potential threat, prompting a fight, flight, or freeze response.

Conversely, the high road takes a slower, more deliberate route involving the cerebral cortex. The message again reaches the amygdala, followed by transmission to the prefrontal cortex, often referred to as mission control. In this pathway, the brain analyzes the data to discern whether the perceived threat is real or merely a perception. This dual-path processing occurs universally, irrespective of the presence of PTSD, illustrating the brain's intricate response to danger or trauma.

What Happens in the Traumatized Brain?

- Inaccurate information

- Overactive emergency alarm, which fires over and over again

This leads to a sympathetic system hyperarousal:

- Which shows itself as:

- Anger

- Irritability, startle response

- Fear, withdrawal, and retreat

When the brain experiences trauma, there is a disruption in the normal flow of information, leading to an influx of inaccurate data and an overactive emergency response from the amygdala. The thalamus, responsible for processing information, becomes a source of misinformation. This heightened emergency response system fires repeatedly, causing the sympathetic nervous system, akin to a security guard, to grapple with decisions—whether to take cover or engage in a fight. This situation results in hyper-arousal of the sympathetic nervous system, manifesting as anger, irritability, a heightened startle response, or withdrawal and fear. This process elucidates the impact of trauma on the brain's response mechanisms.

Sympathetic of the Autonomic Nervous System

- Sym (with)

- Path (feelings)

- Flight or flight or freeze

- Release of adrenaline

The thing to remember about the sympathetic nervous system is that it is responding to any threats in the form of fight or flight. Sym means with and path means feelings, and it basically releases adrenaline.

Parasympathetic System

Para means against, and it's the relaxed mode in our system. It helps us perform our bodily functions, and it has the vagus nerve, which is a salient feature. We are going to talk about the vagus nerve later, but just, you know, it means wandering, and it goes throughout our body. And I'm going to chat with you a little bit more about how that plays a role.

What is Polyvagal Theory?

- There are 2 branches of the Vagus nerve

- Ventral: Social engagement and immobility w/o threat (Parasympathetic system)

- Dorsal: Emergency shutdown mode. Immobility with threat. (Freeze response)

Have you ever encountered the polyvagal theory, a concept that, when discussed, often elicits confusion? Yet, rephrasing it through a relatable lens might shed light on its intricacies. Instead of the somewhat abstract "polyvagal theory," let's explore a ubiquitous experience: the sensation of butterflies in the stomach or the knotting feeling that accompanies unease.

Enter the vagus nerve, a pivotal component intricately associated with the polyvagal theory. Spanning the length of the body, this nerve serves as the neural conduit connecting the brain to vital organs, notably the stomach and intestines. That visceral reaction we commonly term a "gut feeling" finds its roots in the orchestration of the vagus nerve.

Imagine a scenario where decision-making leaves your rational mind in a state of uncertainty. Yet, your gut sends a decisive signal, prompting thoughts like, "I'm not entirely sure, but my gut advises against X, Y, and Z - or perhaps I should proceed." According to the polyvagal theory, this nuanced response is a manifestation of the vagus nerve in action.

The architect behind this theory is Dr. Stephen Porges, a figure worth exploring further. Within the realm of psychotherapy, Dr. Porges dissects the intricacies of the fight-or-flight response embedded within the fabric of the vagus nerve. Furthermore, he reveals that the vagus nerve is activated not only during physical threats but also during the perception of danger, giving rise to the familiar surge of caution, whether warranted or perceived.

Consider this: during moments of heightened threat, our higher cognitive functions may momentarily yield to instinct. However, the vagus nerve, the silent conductor of our bodily functions, takes center stage, furnishing vital cues essential for survival. It underscores the remarkable sophistication of our biological systems—an intricate design geared to furnish us with the requisite information for self-preservation and adept navigation of life's complexities.

No Threat Vs. Threat

- No threat:

- The ventral branch is active

- Fun and frolicking (social)

- Threat

- The symp nervous system activates:

- The parasym slows down, and the heart (skips a beat)

- We are frozen for a moment as we need to decide if there is a real threat or not

- But when there is a clear threat, we are in a fight or flight response

(Porges, 2022)

The dynamics of trauma in relation to our physiological functions—encompassing the brain, the vagus nerve, and more - essentially boil down to a fundamental question: is there a threat or not? This distinction is pivotal in understanding the interplay of our body's responses.

In moments devoid of threat, the ventral branch takes charge, orchestrating optimal functioning of bodily processes. It's a phase where the parasympathetic system reigns supreme, paving the way for a state of ease and even exuberance. Picture it as a time for carefree frolicking, where the body's well-being is a top priority.

However, the scenario shifts abruptly when a threat emerges. The sympathetic nervous system springs into action, causing the parasympathetic system to decelerate. This marks the onset of a critical juncture—a freeze. In this state, we find ourselves momentarily immobilized, engaged in a cognitive assessment of the threat at hand. The pivotal question arises: do we confront the challenge head-on (fight) or seek escape (flight)? It's a nuanced dance between the two branches of the autonomic nervous system, each playing a distinct role in our response to perceived threats.

4 Responses to a Threat

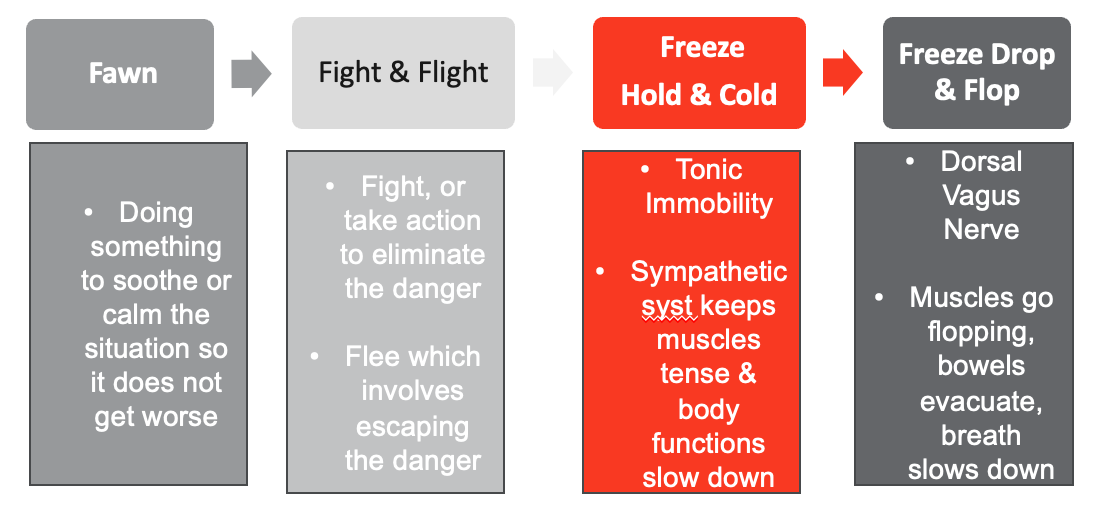

There are four responses to threats, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Four responses to threats.

The concept of "fawning" involves engaging in actions to soothe and de-escalate a situation, preventing it from exacerbating. Reflecting on this, it becomes apparent that in occupational therapy, particularly with children dealing with sensory challenges and emotional regulation issues, we often strive to guide them toward this fawning stage. While the fight-or-flight response is widely recognized, it's crucial to acknowledge other nuanced reactions, such as freeze, hold & cold.

Freeze, manifesting as tonic immobility, involves a state where the sympathetic system keeps our muscles operational but at a decelerated pace. It's a moment of suspended animation, a cognitive pause as we assess the situation. Meanwhile, there's another layer to this complex dance—the freeze, drop & flop response. Here, the dorsal vagus nerve may take the reins, inducing muscle limpness and a gradual slowing of breathing, resulting in a partial shutdown. Interestingly, this response is more pronounced in reptilian animals, who excel at feigning death as a means of evading danger.

These multifaceted reactions constitute the spectrum of responses, underscoring the intricate interplay between our nervous system and environmental stimuli. In the realm of occupational therapy, understanding and navigating these responses are integral to fostering emotional regulation and sensory well-being in children facing unique challenges.

How Can the Polyvagal Theory Help You Feel Safe Again?

- The goal is to relax your Vagus nerve via relaxation techniques like:

- Meditation: This may include humming meditation

- Exercise: Consider cardio, high-intensity weight training, and daily walking

- Socializing: Get some laughter back into your life!

- Singing and Chanting: Alone or with others

- Exposure to Cold: This can range from splashing water on your face to taking an ice-cold shower

- Breathing exercises

Understanding the wide-reaching influence of the vagus nerve in our body prompts the utilization of strategies to regulate it, fostering overall well-being and tranquility. In psychotherapy, the central goal often revolves around preventing individuals from entering shutdown mode. To achieve this, techniques that engage the vagus nerve and promote relaxation are employed.

Activities like meditation, with its humming component, work in harmony to induce a calming effect. The intentional focus on breath and mindfulness in meditation actively involves and regulates the vagus nerve. Similarly, the established link between exercise and stress relief stems from physical activity's capacity to soothe the nervous system.

Socialization becomes a natural support, providing a platform for connection and emotional well-being. Singing and chanting, known for their rhythmic qualities, contribute to modulating the vagus nerve. The trend of cold exposure on platforms like TikTok has gained popularity not only for its direct engagement of the vagus nerve but also for its grounding effect. Exposure to cold redirects attention to the present moment, diverting focus from ruminating thoughts.

Breathing exercises, fundamental in various mindfulness practices, play a crucial role in centering individuals. Deliberate control and deepening of breath activate the vagus nerve, fostering a sense of calm and equilibrium.

In summary, these strategies highlight the substantial impact of the vagus nerve on mental and physical states. Incorporating these practices into routines serves as a proactive measure to promote overall well-being and prevent the onset of detrimental shutdown responses.

Sensory System & Trauma

- Elicits survival responses from the brain & nervous system

- If recurrent, these survival or fight/flight and freeze responses will adversely affect the development of affective, physiological, and cognitive functions

- Impacts self-regulatory and relational capacities in the survivor

(McGreevy & Boland, 2020)

Recognizing the widespread influence of the vagus nerve throughout our body suggests effective strategies to regulate it, contributing to overall well-being and tranquility. In psychotherapy, the central objective often revolves around preventing individuals from entering shutdown mode. To achieve this, harnessing the vagus nerve and employing relaxation techniques becomes instrumental.

Activities like meditation, with its humming component, work in tandem to induce a calming effect. The intentional focus on breath and mindfulness in meditation engages and regulates the vagus nerve. Similarly, the link between exercise and stress relief is rooted in physical activity's ability to soothe the nervous system.

Socialization naturally aligns with this goal, providing a platform for connection and emotional support. Singing and chanting, known for their rhythmic and melodic qualities, contribute to the modulation of the vagus nerve. A notable trend on platforms like TikTok emphasizes exposure to cold as a means of achieving mental and physiological balance. The appeal lies not only in directly engaging the vagus nerve but also in the grounding effect of cold exposure, redirecting individuals to the present moment.

Breathing exercises, fundamental in various mindfulness practices, play a crucial role in centering oneself. Deliberate control and deepening of breath activate the vagus nerve, fostering a sense of calm and equilibrium.

In essence, these strategies underscore the profound influence of the vagus nerve on our mental and physical states. Incorporating these practices into our routines becomes a proactive measure in promoting overall well-being and preventing the onset of detrimental shutdown responses.

Attachment Theory & Trauma

- John Bowlby (psychiatrist) & Mary Ainsworth (Psychologist)

- Attachment theory is based on the belief that the mother-child (or caretaker) bond is the primary force in infant development.

- Responsible for:

- shaping all future relationships

- shaping our ability to focus

- an awareness of our feelings

- an ability to calm ourselves and

- the ability to rebound from misfortune

Attachment theory and trauma offer a valuable framework for understanding adult clients. The inquiry into one's childhood and the dynamics of relationships with caregivers carries significant weight. Developed by a psychiatrist and a psychologist, attachment theory emphasizes the pivotal role of early bonds in shaping future relationships and overall psychological well-being. Our capacity to focus, navigate emotions, and engage in relationships is profoundly influenced by these early attachments. In the context of therapy, delving into these connections becomes a potent tool for comprehending and addressing the challenges faced by adult clients. Despite the seemingly casual nature of inquiries into childhood relationships, the impact of early attachments is profound, influencing an individual's life trajectory. Attachment theory enriches therapeutic understanding by highlighting the intricate interplay between past and present experiences.

4 Attachment Styles

- Secure

- Avoidant

- Ambivalent

- Disorganized

(Midolo et al., 2020)

Attachment styles describe a relationship, and there are four different types.

Avoidant Attachment Style

- Baby cries and cries. No response from a caregiver. Heightened fight/flight reaction but still no response from the caregiver…

- The Dorsal Vagus pathway shuts down.

- Dissociating from one's own desires and needs...because they are not being met.

- Can be aloof.

- Don’t rely on others.

- Avoids own emotions and other's emotions.

The avoidant attachment style manifests when a baby or infant cries, but the parent or caregiver is consistently unavailable or rejects the child due to their own challenges. In this scenario, the child can feel forgotten and may retreat into their own world, leading to a lack of emotional connection. Growing up, individuals with an avoidant attachment style become accustomed to aloof relationships, avoiding reliance on others and steering clear of emotional connections. This pattern may result in an inclination to avoid emotions and resist forming deep emotional bonds with others.

Ambivalent Attachment Style

- When the child experiences the caregiver as inconsistent or intrusive

- Children will often become anxious and fearful, never knowing what to expect

- The result is erratic emotional clinging accompanied by frustration and resentment

The ambivalent attachment pattern is characterized by erratic emotional clinging paired with feelings of frustration and resentment. This pattern tends to develop when a parent is inconsistent or intrusive. As a result, the child becomes anxious and fearful due to the uncertainty of what to expect from the caregiver. The child may grapple with questions like, "Will you be the nurturing figure or the punishing one?" This uncertainty can lead to difficulties in forming connections, and the individual may develop a tendency to reject others before anticipating potential rejection, stemming from a longstanding expectation of inconsistency and unpredictability.

Disorganized Attachment Style

- Sometimes caregivers responds sometimes they don’t. Or, they respond by hurting the child

- This leads chaotic relationships… very clingy, very aggressive, walking out

- Tends to happen in complex trauma

- Difficulty in regulating emotions and reading social cues

- Difficulty with academic reasoning, and severe emotional problems

The disorganized attachment style emerges as a coping strategy for individuals whose caregivers are perceived as punishers rather than sources of comfort and support. In instances where caregivers are expected to provide soothing and assistance but fail to do so, the child may experience punishment or be ignored. This leads to a disorganized state where the child struggles to collect themselves, often crying more intensely. This pattern is commonly observed in foster children, especially those facing sensory overload, as they may need to reach a point of disorganization before receiving attention.

The disorganized attachment style results in relationships characterized by clinginess and aggression. This tendency is more prevalent in cases of complex trauma. Children with this attachment style encounter challenges in regulating emotions and interpreting social cues. Notably, they often rely on the next available adult for emotional regulation, which becomes precarious in settings like foster care, where transitions between caregivers are frequent and unpredictable. The constant back-and-forth creates an inefficient and disorganized attachment style, compounding the challenges these individuals face in forming stable and secure connections.

Attachment Differentiation/Separation Individuation Cohesion Integration

- All our experiences are filtered by our senses.

- Brain development is sequential and hierarchical.

- Rather than deprivation of sensory stimuli (neglect), the traumatized child experiences over-activation of important neural systems during these sensitive periods of development.

It's crucial to recognize that attachment exists along a continuum and follows a developmental timeline, with attachment being the first conscious developmental task a child undertakes. A fundamental principle to consider is that all experiences are filtered through our sensory systems - light, sound, taste, etc. This initiates a cascade of neurochemistry that can ultimately shape our brain structure and function. The key lies in the delicate balance of receiving the right input; too much or too little can alter neural activation and become internalized.

Another important principle is the sequential and hierarchical development of the brain, progressing from less complex structures like the brain stem to more complex ones such as the limbic system and cortical areas. These areas develop and interact with other systems, forming the foundation of a child's emotional map. However, due to the asynchronous development of different brain regions, experiences from infancy may not manifest until later stages of development.

Understanding that the brain develops in stages is critical, as experiences in infancy provide the structural framework for a child's emotional future. This insight is especially important in contexts like early intervention, where the child's background, such as adoption or orphanage experiences, should be considered. Ensuring a full sensory experience is crucial during these early stages, as any lack or abnormal pattern can impact a child's sensory system. Deprivations or abnormalities in sensory experiences during infancy may lead to trauma that surfaces later in development. Therefore, addressing these factors early on is essential in fostering healthy emotional development in children.

Case Study 1: Mishka- 2 Years Old

Adopted at 18 months from a Russian Orphanage

- Extreme emotions

- Scattered play

- Limited eye contact

- No communication

- Sensory hyper/ hypo responsivity

- Fear of baths

Given the case study of Mishka, an 18-month-old adopted from a Russian orphanage who is displaying extreme emotions, scattered play, limited eye contact, and no communication, you, as an early intervention provider, are tasked with addressing her needs. Additionally, Mishka exhibits mixed sensory distributions with hyper and hypo-sensitivity, and her responsiveness varies on a day-to-day basis. Notably, she has an abnormal fear of baths. The limited knowledge about her past includes the fact that she was adopted, and her adoptive mother is struggling due to Mishka's frequent crying and limited engagement.

How Can We Help?

- Use task analysis to enable environmental accommodations

- Teach self-regulation strategies

- Serve as a resource

- Providing frequent direct instruction and modeling to create ongoing competence and success

- Collaborating and modeling emotional management strategies consistently among the staff

- Identify triggers and parent education

In approaching this case from a trauma-informed perspective, it's important to recognize the potential impact of Mishka's early experiences on her current behavior. Her scattered play, limited eye contact, and lack of communication could be indicative of challenges in forming secure attachments or disruptions in early caregiving. The mixed sensory distributions and abnormal fear of baths may suggest sensory processing difficulties, possibly stemming from unpredictable or distressing experiences.

To address Mishka's needs, a trauma-informed approach involves creating a safe and predictable environment. This may include:

- Building Trust: Establish a trusting relationship by maintaining consistency in interactions. Provide predictability in routines and responses to help Mishka feel secure.

- Sensory Regulation: Implement sensory activities that cater to Mishka's individual sensory needs. This could involve exploring different textures, incorporating calming activities, or gradually introducing sensory experiences like baths in a controlled and comforting manner.

- Non-Verbal Communication: Given her limited communication skills, focus on non-verbal communication methods, such as gestures, visual supports, or alternative communication tools, to facilitate understanding and expression.

- Parental Support: Collaborate closely with Mishka's adoptive mother to understand her perspective and provide guidance on trauma-informed parenting strategies. Support the mother in building a secure and nurturing relationship with Mishka.

- Observation and Flexibility: Continuously observe Mishka's responses and adjust interventions based on her day-to-day variations. Flexibility in approaches is key to meeting her evolving needs.

Understanding trauma and its potential manifestations in Mishka's behavior allows for tailored interventions that promote her emotional well-being and development. Adopting a trauma-informed lens ensures sensitivity to her unique experiences and fosters a supportive environment for her growth.

More Occupation-Based Strategies

- Making activities and routines predictable

- Helping her regain control by allowing for choice within activities

- Pairing sensory/cognitive approaches to teach her to calm her body and mind

- Providing frequent positive reinforcements

- Recommending stress management strategies

- Collaborating with clients to identify goals and interventions designed to empower families

To address Mishka's needs using occupation-based strategies, it's crucial to establish predictability in activities. Given her regulation difficulties, routines become paramount, helping her adapt to new scenarios without triggering trauma responses. Using pictures and visuals can aid her understanding, and gradually introducing choices - perhaps starting with one or two - allows her to experience decision-making.

Pairing sensory and cognitive approaches is essential for teaching Mishka to regulate her body and mind. Incorporating blowing techniques in games, where she engages her breath, serves as a sensory-cognitive strategy. Prompting her to identify and label emotions during these activities reinforces emotional awareness.

Positive reinforcement plays a vital role, but it requires careful evaluation of what constitutes reinforcement for Mishka. Hugs may not be universally comforting, so understanding her preferences is key. Observing her reactions and preferences helps tailor positive reinforcement to what genuinely resonates with her.

Considering the long-term impact of trauma on attachment, recommending stress management strategies for the parent, in this case, Mishka's adoptive mother, is crucial. Ensuring the mother's well-being and equipping her with strategies to navigate her own potential trauma supports a healthy attachment moving forward.

Maintaining a client-centered and family-centered approach is paramount. Understanding Mishka's unique needs and involving her adoptive mother in the intervention process ensures a holistic and supportive environment. By implementing these occupation-based strategies, the aim is to create a predictable, nurturing space that fosters Mishka's emotional well-being and encourages positive attachment experiences.

A Sensory Based Approach

- Includes body-based interactive activities such as rhythmic, patterned, and repetitive activities that support self-regulation.

- Such activities include mindful breathing, listening to music and singing, humming, doing yoga, and other types of physical activity and playing circle games.

Taking a sensory lens into consideration, the literature supports the use of sensory integrative therapy to aid in trauma. Body-based interactive activities become crucial for Mishka, incorporating rhythmic patterns and linear movements repetitively to promote regulation. However, caution is advised with activities involving spinning, as it can be both alerting and potentially lead to sensory overload.

Other recommended sensory-based activities for Mishka include mindful breathing, engaging in activities like "blow the candle out" to promote regulated breathing, humming, singing, yoga, participating in yoga sessions to promote body awareness and relaxation, physical activity, engaging in any form of physical activity to enhance overall sensory integration, and circle games, involving Mishka in activities that require movement and body engagement within a structured circle.

These sensory-focused interventions aim to provide Mishka with the sensory input necessary for regulation and promote a positive sensory experience. Integrating these activities into her routine contributes to her overall well-being and supports trauma recovery through a sensory lens.

Starfish Breathing Exercise

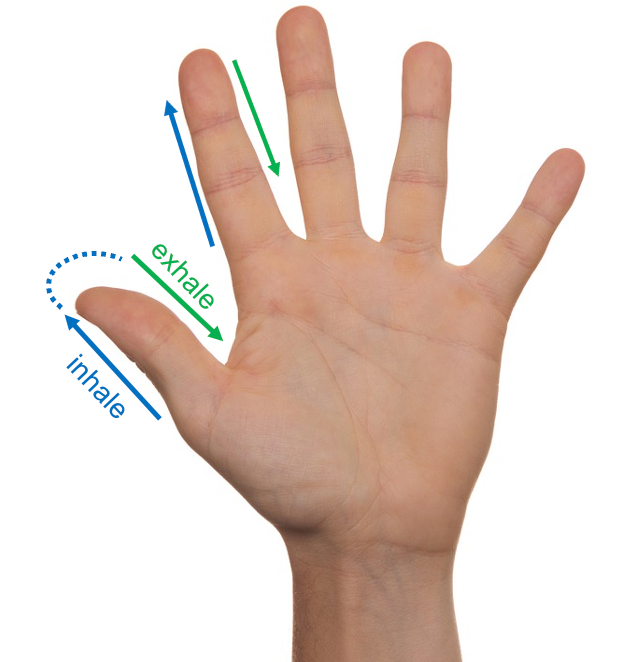

Figure 5 shows a breathing exercise that I use with a lot of my little ones, as it works really nicely.

Figure 5. Starfish breathing exercise.

You hold your hand out, and they take their finger and follow the outline of the fingers in hand. They inhale and exhale as they go around each finger. It is a nice activity that works with a lot of my preschoolers and little ones.

Repetitive "Put-In" Activities

- Foster fine motor dev

- Close ended

- Self-regulation

- Grounding

- Being present

- Sense of accomplishment

- Reinforcement

- Versatile

- Novel

The other activity that I love for any child with trauma, or even sensory processing difficulties is repetitive put-in activities, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Examples of repetitive put-in activities.

Utilizing simple, non-commercial items for activities holds numerous advantages. Not only are they accessible to everyone, regardless of financial resources, but they also captivate children's interest as they find them novel. In contrast to ubiquitous traditional toys, these activities stand out and often become more appealing to children.

These activities, focusing on coordination, are close-ended, fostering self-regulation as children intuitively understand what is expected without the need for extensive instructions. The repetition of a single sensory input encourages presence, provides a sense of accomplishment—something she may not have experienced much—and proves highly reinforcing. The versatility of these activities allows for creative adaptations, such as adding a sensory component like placing balls in rice, making them adaptable to different mediums and environments.

A Transdisciplinary Approach

- "Occupational therapists can effectively collaborate with psychologists and make unique contributions to trauma-specific treatment focusing on function in the areas of self-care, leisure, and productivity, addressing symptom management and supporting clients in approaching feared and avoided situations.“

(Torchalla et al., 2019)

The literature emphasizes the importance of collaboration between occupational therapists (OTs) and other disciplines, such as psychologists, to create a truly holistic therapeutic experience. OTs, with their expertise in activity analysis and sensory processing, bring valuable elements to the collaborative table. This interdisciplinary approach ensures a comprehensive understanding of an individual's needs and fosters a more effective and well-rounded therapeutic intervention. By leveraging the strengths of each discipline, practitioners can address a broader spectrum of factors influencing a person's well-being.

Key Factors for a Trauma-Informed Approach…

- Realize the widespread impact of trauma and understand potential paths for recovery; recognize the signs and symptoms of trauma in clients, families, staff, and others involved with the system; and respond by fully integrating knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and practices, and seeks to actively resist re-traumatization.

https://ncsacw.acf.hhs.gov/userfiles/files/SAMHSA_Trauma.pdf

Adopting a trauma-informed approach involves recognizing the widespread impact of trauma and understanding the phases of recovery. Occupational therapists, with their knowledge of sensory processing, can identify signs and symptoms similar to sensory overload. Communicating the scientific and biological aspects of trauma is essential, using visual aids like the hand model to help clients understand bodily responses. Integrating trauma knowledge into policies, procedures, and practices ensures a supportive environment. Additionally, therapists must be vigilant to resist retraumatizing individuals, maintaining a sensitive approach to avoid triggering distressing responses or memories. This holistic approach contributes to a supportive and understanding environment for those affected by trauma.

What About Sensory Strategies?

- Sensory-based interventions to improve trauma processing physically in the body (McGreevy & Boland, 2020).

- Sensory-based interventions with adult and adolescent trauma survivors are emerging as promising areas of practice and research in the literature.

- Atypical SP patterns identified in survivors.

- A sensory-based, transdisciplinary approach to treatment has the potential to be effective in treating the trauma survivor.

Addressing sensory strategies is crucial in trauma interventions, although limited literature exists on the topic. Despite the scarcity of research, sensory-based interventions play a key role in improving trauma outcomes. Many individuals affected by trauma and PTSD exhibit atypical sensory processing patterns. However, determining whether sensory issues precede trauma or vice versa remains unclear, resembling a "chicken or the egg" dilemma. Regardless of the sequence, the treatment approach remains the same. Therefore, emphasizing sensory-based approaches is essential for effectively addressing the unique needs of individuals experiencing trauma or PTSD.

6 Strategies Recommended by NASMHPD

- Foster leadership to initiate and sustain focus, allocate resources for change, and encourage role modeling

- Collect data on restraint and seclusion incidents and share them staff

- Develop the workforce, using principles of recovery-oriented care, person-centered care, respect, partnership, and self-management

- Reduce restraint and seclusion through awareness of trauma, safety plans, comfort rooms, occupational therapy techniques, and de-escalation

- Involve patients and their families in safety plans

- Debrief in the moment with emotional support; include patients and staff, and conduct formal problem-solving debriefings to look for root causes

The strategies advocated by the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors find broad application in diverse settings, ranging from hospitals to mental health facilities. These encompass a multifaceted approach, beginning with a focus on leadership and organizational change. This involves the establishment of a shared language and the implementation of policies and procedures aimed at empowering individuals with tools for safe and effective de-escalation.

Data assumes a pivotal role in shaping practices, with an emphasis on informed decision-making grounded in evidence. Workforce development emerges as a critical aspect, emphasizing the cultivation of an in-house team of crisis prevention experts to proactively avert escalations and provide essential support.

A significant paradigm shift involves reducing reliance on restraint and seclusion, with a corresponding emphasis on teaching regulation strategies to foster a safer and more therapeutic environment. Consumer engagement becomes integral, with individuals actively participating in their own care within inpatient settings, fostering a sense of empowerment and collaboration.

Comprehensive de-escalation training ensures that staff is well-equipped with the skills necessary to navigate challenging situations effectively. Finally, the implementation of debriefing techniques serves as a crucial evaluative tool, allowing for a thorough assessment of strategy effectiveness and providing valuable insights to guide future decision-making.

Collectively, these strategies are designed to create an environment that is not only informed and supportive but also proactive in addressing the complex needs of individuals undergoing trauma or crisis.

SAMHSA (2018): Six Core Trauma-Informed Principles

Here are some of the substance abuse mental health administration guidelines.

Safety

We need to find out what safety means to the person because it can vary. For you and me, safety may be not hearing a fire alarm, but for them, it might be related to racism, culture, and things like that.

Trustworthiness and Transparency

We must be very open and build this relationship of trust when we're dealing with patients with trauma.

Peer support and Mutual Self-Help

This is about integrating the culture and values to support not only from a peer standpoint but into the whole organization wherever you're working. It is creating initiatives to support admin and staff.

Collaboration and Mutuality

We must break down power differentials. With this, there is a spirit of mutuality and being together.

Empowerment, Voice, & Choice

This is where we believe that there is a possibility of recovery from trauma, there is resilience, and that we are conveying that. You are empowering them to get out of this and to move past it.

Cultural, Historical, & Gender Issues

Addressing cultural, historical, and gender issues is essential in trauma-informed care. It involves transcending biases and providing responsive services that acknowledge and understand the trauma experienced. Moving beyond these issues requires a commitment to recognizing the impact of historical and cultural factors on individuals.

Practice "Trauma Stewardship"

- Caring for patients without taking on their trauma yourself

- Raja and colleagues (2015) stated the importance of knowing your own history and reactions

Simultaneously, practitioners must be mindful of their own well-being, embracing the concept of trauma stewardship. This acknowledges the potential for professionals to be triggered and vulnerable to the traumatic influences they encounter. As occupational therapists, exposure to gut-wrenching details of war, unsavory situations, or instances of child abuse can seep into one's psyche. Therefore, self-care becomes a critical component in maintaining resilience and effectiveness in the provision of trauma-informed care.

Trauma stewardship is a belief that both joy and pain are realities of life and that suffering can be transformed into meaningful growth and healing when the quality of presence is cultivated and maintained even in the face of great suffering.

Trauma From Addressing Trauma: Self Care for Therapists

- Vicarious trauma

- May trigger you

- Mindful breathing after the session

- A circuit breaker at the end of your day… going for a walk, etc.

- Professional support (supervisor/therapist)

- Therapists need therapists

- Be aware of your own trauma and triggers

Being vigilant about vicarious trauma is crucial, as exposure to others' traumatic experiences can potentially trigger emotional responses in practitioners. Incorporating mindful breathing into one's routine, even if just for a few minutes after sessions, can serve as a helpful tool. The significance of mindful breathing was evident in a scenario with first-year occupational therapy students, where a brief mindfulness exercise effectively alleviated high levels of anxiety.

Recognizing the importance of self-care is essential. Activities such as going for a walk, taking a bath, or seeking professional help when needed can contribute significantly to maintaining mental and emotional well-being. It's essential for therapists to acknowledge that they, too, may require support, and seeking therapy is a valid and valuable option.

Ultimately, awareness stands as a foundational element in addressing trauma, whether experienced by others or oneself. Being attuned to personal traumas and consistently engaging in self-care practices enables practitioners to navigate the challenges of providing trauma-informed care while safeguarding their own mental and emotional health.

Free Mental Health Worksheets

I do have some mental health worksheets on my website if at all you're interested in practicing some of these trauma stewardship activities.

Resources

- CBD worksheet

- TIC guide

- https://www.umassmed.edu/cttc/trauma-resources/for-medical-providers-and-practices-trauma-informed-care-resources/

Questions

What is the polyvagal theory?

The polyvagal theory basically states that your vagus nerve, which is the longest nerve in the body, connects your brain to the rest of your organs. This is what makes that mind and body connection possible. When we feel a gut reaction to a situation, it relates to this theory, and basically, the theory is that when a person feels safe, they're in a position to have higher cognitive functioning. If they sense danger, whether it's real or perceived, these higher functions shut down. When this happens on a chronic basis, it's like you are stuck in an "on" position. This is when your vagus nerve, dorsal or ventral, shuts or slows down the functioning of the rest of your body.

How does the polyvagal theory relate to trauma?

In certain instances, an individual may perceive a sense of danger through their vagus nerve, bypassing higher-level cognitive processing. Essentially, this distinction lies in the experience of stress and potential danger being felt through physiological sensations, contributing to what is commonly referred to as a "gut reaction." Subsequently, higher-level cognitive functions come into play, allowing the individual to reassess the situation and potentially conclude that the perceived threat is not aligned with the actual circumstances.

Working with medically complex children with cognitive disabilities, do you have any suggestions for this type of trauma?

When dealing with medically complex cases, a collaborative approach is essential. The initial step involves engaging with the interdisciplinary team, which may include psychologists and social workers. It is crucial to gain insights into the child's attachment style, recognizing that attachment dynamics for children with medical complexities or special needs differ significantly from those typically observed. Thus, a thorough understanding of the unique attachment challenges in such cases is imperative for effective intervention.

How do we transfer trauma to an older population after falls or any accidents?

In instances of trauma, it is important to distinguish between psychological trauma and the immediate, visceral response to a traumatic event. For example, a simple incident like falling while ascending stairs can elicit a traumatic reaction in individuals. Consequently, patients may form an association between the event and trauma, leading to an aversion to repeating the activity.

To address this, a strategic approach involves revisiting the activity and employing positive reinforcement along with behavioral interventions. By reintroducing the task gradually and incorporating positive reinforcement techniques, the goal is to mitigate the emotional response and foster a more adaptive reaction to the previously traumatic experience.

You briefly mentioned a video website earlier. Do you have the website listed in the PowerPoint for later reference?

I mentioned Dr. Russ Harris. If you look that up on YouTube with the keywords of trauma-informed care, you should be able to find it.

What competencies do you think OTs have as strengths in implementing a trauma-informed approach?

Our profession boasts a comprehensive set of competencies. Firstly, we adopt a holistic approach, considering the entirety of an individual rather than focusing solely on specific aspects such as behavior or physiology. This comprehensive perspective distinguishes our approach. Secondly, our expertise in sensory processing sets us apart. Given that sensory processing plays a pivotal role in trauma and trauma-informed methodologies, our proficiency in this area positions us ahead of our counterparts.

How have you brought up trauma to families that don't necessarily accept and understand the impacts of trauma?

Addressing this challenge requires a nuanced approach. It's undoubtedly a complex task, and, to be candid, it poses significant difficulty. Typically, I collaborate with the social worker and emphasize the importance of teamwork in such sensitive matters. I choose to broach the topic selectively, doing so only when deemed beneficial.

Importantly, I avoid framing discussions in a manner that assigns blame or suggests causation. Instead, I adopt a more informative tone, expressing a desire to share insights about the diverse forms in which trauma can manifest. For instance, I might illustrate instances where certain parental behaviors could inadvertently contribute to traumatic experiences. This approach aims to raise awareness without inducing feelings of guilt or shame.

Recognizing the potential emotional triggers for parents, it becomes essential to exercise conscientiousness and mindfulness throughout these conversations. I trust that these insights address your concerns.

Should you have further inquiries, please feel free to reach out via email. Additionally, I maintain a TikTok channel where I discuss various aspects of therapy, particularly tailored for parents. You can find me under the handle of Dr. Aditi Parenting Coach.

References

Avery, B. (2020, January 7). What sensory overload feels like for people with PTSD, HealthyPlace. Retrieved on 2023, May 8 from https://www.healthyplace.com/blogs/traumaptsdblog/2020/1/what-sensory-overload-feels-like-for-people-with-ptsd

Azeem, M., Aujla, A., Rammerth, M., Binsfeld, G., & Jones, R. B. (2017). Effectiveness of six core strategies based on trauma informed care in reducing seclusions and restraints at a child and adolescent psychiatric hospital. Journal of child and adolescent psychiatric nursing: Official publication of the Association of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nurses, Inc, 30(4), 170–174. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcap.12190

Bruce, M. M., Kassam-Adams, N., Rogers, M., Anderson, K. M., Sluys, K. P., & Richmond, T. S. (2018). Trauma providers' knowledge, views, and practice of trauma-informed care. Journal of trauma nursing: The official journal of the Society of Trauma Nurses, 25(2), 131–138. https://doi.org/10.1097/JTN.0000000000000356

Cutuli, J. J., Alderfer, M. A., & Marsac, M. L. (2019). Introduction to the special issue: Trauma-informed care for children and families. Psychological Services, 16(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000330

Dowdy, R., Estes, J., McCarthy, C., Onders, J., Onders, M., & Suttner, A. (2022). The influence of occupational therapy on self-regulation in juvenile offenders. Journal of child & adolescent trauma, 1–12. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-022-00493-y

Citation

Mehra, A.(2023). Trauma informed care: What does an occupational therapy practitioner need to know? OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5656. Available at www.occupationaltherapy.com