Introduction

Good afternoon, everybody. I am very excited to be with you all. I am very grateful to continued and OccupationalTherapy.com for having me. I always enjoy receiving these opportunities and getting to talk about ACEs and infant mental health. I am really grateful to this platform and really enjoy my audiences.

What are Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs)

- Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) are a series of 10 items that have been found to be directly linked to:

- Childhood Development

- Brain Architecture

- Academic Success

- Health Outcomes

- Job Satisfaction

- Divorce Rates

- Life Expectancy

For some of you, this may be new information, while others may have learned and heard this term numerous times. ACEs refers to Adverse Childhood Experiences. There is a list of 10 key factors that through multiple research studies have been found to be directly linked to the trajectory in childhood development, brain architecture, neurological development, and academic success across the lifespan. Primarily, the research has been around long-term health outcomes, which we will talk a lot about. It is one of the places where we see OT really integrate and interface with people who have experienced ACEs. Job satisfaction is also a huge correlation to ACEs as are divorce rates and life expectancy. These 10 key factors have a large impact on many domains within our general well-being and functioning.

The Story of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs)

How did we come to find these 10 key factors, and what do they mean? In the mid to late 1990s, Kaiser Permanente realized they had a small percentage of members who were consuming a vast amount of money within the insurance pool. Generally, in insurance terms, these individuals are known as "super users." Although the number is small, they generally utilize the majority of the resources. In an effort to assess factors that contribute to the high cost of health care, Kaiser Permanente sent out a massive survey study that assessed hundreds of questions around early experiences and health behaviors.

Survey Study Questions:

- How old were you the first time you drank alcohol or smoked cigarettes?

- How many moves across the country did you have?

- Were your parents divorced, single, remarried?

- How many times were your parents remarried?

The results identified 10 key factors that occurred prior to an individual's 18th birthday had long-term impacts on that person's health and well-being as an adult.

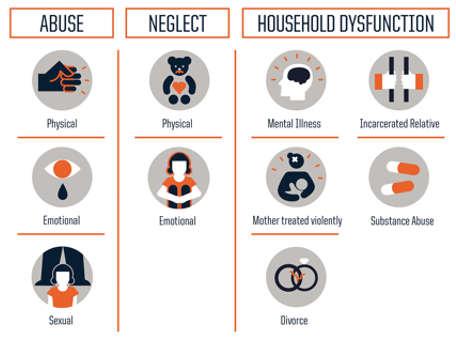

Figure 1. 10 key factors found in the Kaiser Permanente study.

Before we move forward in dissecting this graphic (Figure 1. 10 key factors), I want to pause for a minute and acknowledge a few things. When I talk about ACEs, the first thing that happens is that everyone thinks about themselves. We begin to think through how we were as children, our own families of origin, and how this information applies to us. This is a very natural process, because inevitably as human beings, we all see the world through our own eyes. We may also think about the situations and individuals that we encounter in our day-to-day professional world. This might be individuals with conditions such as psychosis, schizophrenia, mania, and alcoholism.

We may have not all experienced a broken bone or have had some type of surgery; however, we have all been there. We all know what it is to be a young child who tries very hard to get a point across and sometimes struggles to do so even in the best of circumstances. Even with the most attentive caregivers, sometimes we are not heard. We have all had the universal experience of being a child at one point, and this makes this topic that much more evocative. We need to be mindful today about our own experiences and sense of being.

The 10 factors that Kaiser Permanente identified, were broken down into two categories. The first five key items had to do with abuse and neglect, including physical, emotional, or sexual abuse, and then physical or emotional neglect. The last five key items stemmed from household dysfunction.

Category questions:

- Prior to the age of 18, did you reside in a house in which someone else was diagnosed with a mental health concern?

- Prior to the age of 18, did you reside in a house with a caregiver who was incarcerated?

- Prior to the age of 18, did you reside in a house where a caregiver battled with substance abuse?

- Prior to the age of 18, were your parents divorced?

There are some caveats within the ACEs research that we need to highlight. As the research was originally completed in the '90s, some things may have changed. For example, what we know about intimate partner violence now, how we recognize it, and its general play within family systems is very different than when compared to 1994. The primary question in many research projects is, "Were either of your caregivers ever treated violently by another romantic partner?" The question is all-encompassing of what a child may have seen or experienced and is not quite so narrowing in its definition.

How Common are Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs)?

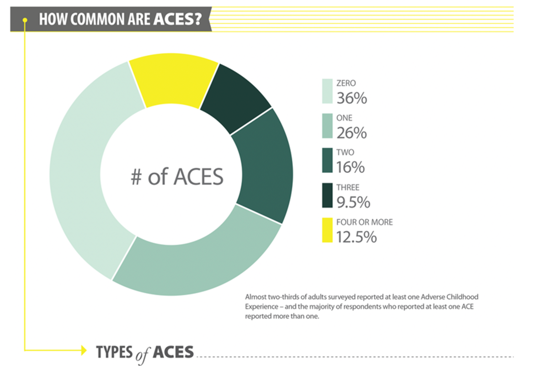

Here is an image of the prevalence of ACEs in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Prevalence of ACEs.

More than four ACEs are considered to be a cutoff point which begins to shift towards long-term health outcomes impacting socio-economic status. For people who have two ACEs, the research demonstrates a greater impact than those who have one. Likewise, three ACEs have a greater impact than two, but we see a substantial shift in those long-term health outcomes once an individual has four or more ACEs.

Understanding the Research

- The research was completed in the 1990s but did not reach common discussion until approximately 2010

- The research was initially completed on a sample of predominantly White, middle-class, educated individuals

- Since the original study, extreme poverty and incidents of racism have been added to the original 10 ACEs

- All ACEs are trauma, but all trauma is not an ACE

The study laid dormant until about 2010. In that general time frame, there was a shift nationally around understanding ACEs, and there was about a 20-year gap where ACEs existed but were not talked about. We know there were some real limitations on the original study like population. Since the original study, the only other two factors that have reestablished normative data impacting long term health outcomes include extreme poverty and incidents of racism.

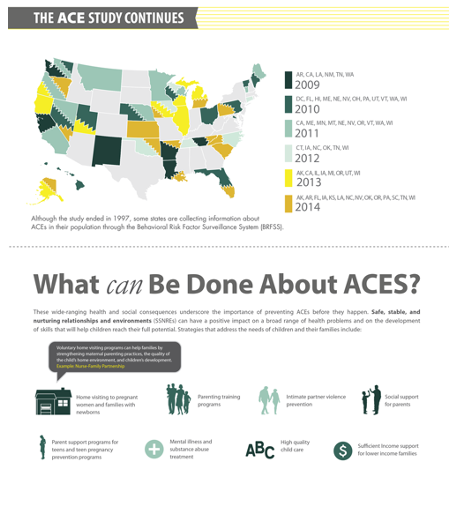

We always hold that all ACEs are trauma, but all trauma is not an ACE. It does not mean individual traumas are somehow more or less important. ACEs are a research study with a sufficient prevalence in the greater population that can provide normative data and statistical responses. For example, Nashville at the beginning of March experienced two considerably devastating tornadoes. Those are traumas. The community and many families were deeply traumatized. We will all hold some trauma, and it is not always an ACE. There is not sufficient evidence that people who experience singular natural disasters will have long-term health outcomes as a result. Figure 3 shows some more information about the ACE study.

Figure 3. The ACE Study continues.

ACEs research has now been duplicated multiple times across numerous states and other countries. Most states in the US have completed their own ACE study. Each state took the original set of data, looked at people across their insurance panels, and compared what the outcomes were. We know the original study was normed on an upper middle class, well-educated employed population. When looking across sectors of the population, 13% of the population display four or more ACEs, and we see that about two-thirds of the population as a whole has experienced some level of an ACE.

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) in Early Childhood

- Chronic stress is characterized by cortisol production in the brain

- Cortisol “bathes” necessary portions of the brain and selects only the pieces necessary for survival.

- Brain functioning is the most essential in the lower regions of the brain

- Executive Functioning is stored in the frontal regions of the brain (Decreased access)

ACEs are so impactful because they are considered chronic trauma, not single incident trauma. Chronic trauma can be conceptualized as a child living at home with their family where there is substance abuse. These events occur numerous times, often unpredictably. My example of a tornado happened once in Nashville in 30 years, and it did not last for days or weeks. Another example is a parent who is incarcerated for years. This leads to chronic stress and trauma because there is no clear beginning or end.

There is a great deal of conversation within the community about what the coronavirus and COVID-19 will mean for our young children, and we do not know that yet. It is definitely different than a car crash. It is not over and done. It has been here for a while and may last a lot longer. We know the chronic nature of any type of stress and anxiety generally has a result, and we will have to wait and see what that means. Children who have multiple ACEs and are exposed to real incidents of chronic stress and trauma, their levels of hypervigilance, and survival needs are very elevated.

Brain Architecture

- Positive development and neurological formation in early childhood use relationships as their foundation

- Increased chronic stress damages the brain’s access to impulse control, analytical thinking, and cause and effect.

- Feelings fuel behavior

- Safe, predictable, relationships allow children to decipher safety from danger to regulate their stress hormones

Your brainstem sits at the base of your head and connects to your spine. The frontal cortex is the part that lets us be human as we have impulse control and the ability to connect cause and effect. Your limbic system sits in the mid part of your brain. When cortisol bathes your brain, it starts at the front but covers most of the back because your most vital regions are located in your brainstem. This is where you control your heart rate, blood pressure, and body temperature. Even though it is a really good idea that we can connect cause and effect or be able to remember and give words to our experiences, they are not vital for our survival. Thus, our brain will shut them down and move all of its efforts down and back. When this happens, we are not really good at impulse control or connecting cause and effect. Most of us as adults, who by virtue of being on this training, have some level of secondary education do not always make great choices when we are under stress. When we think about the needs of young children or families under chronic stress and trauma, the likelihood that they are going to think through choices or have great impulse control is minimal. This is the same when we are thinking about memory and access to words.

We know the positive development and neurological formation in early childhood depends on relationships as their foundation. In place of bathing the brain in cortisol, the counterpoint to that is positive, consistent relationships with adults that may or may not be a parent. It could be what we refer to as a psychological parent, or somebody who is there and emotionally available, but might not actually be the person in charge of caring day-to-day for that child. When relationships are dependable, predictable, and consistent, this allows for hormone production to decrease just enough to move forward in growth and development. Chronic stress does long-term damage that we can see that through PET scans and MRIs. The brain's ability to access impulse control, analytical thinking, and cause and effect is then affected. This underscores the idea that feelings fuel behavior when it comes to young children. This is acting out emotionally to a perceived threat to our survival. This stimulates the way that young children respond and engage in interactions. On the other hand, safe and predictable relationships anchor us back allow us to begin to identify and decipher between what is safe and what is dangerous. This is one of the places where we see the long-term impact of chronic stress and trauma. When a child does not have a predictable relationship in which to anchor, the child does not learn the difference between what is safe and what is dangerous.

Executive Functioning

- The Executive Functions of the brain often act as an air traffic control system.

- They direct emotions, information, and reactions to “land safely.”

- Children with numerous ACEs, and subsequent high chronic stress, often behave as if there is no one in their control tower.

- Chronic stress results in the brain’s inability to navigate emotions and communicate effectively

In the executive functioning section of the brain that control impulses, analytical thinking, and cause and effect, can be thought of as an air traffic control system. Those executive functions are supposed to land all of the many things that we are juggling all day. They have to direct information around emotions and responses in order for young children to navigate safely. However, children with numerous ACEs and chronic stress and trauma, because of that increased level of cortisol, have emotional systems that are overwhelmed. As such, it becomes challenging for them to handle additional things throughout the day. A child's response may be quite large to simple stimuli. For example, a child may have a big meltdown because they are asked to take a nap. Or, they punch their friend on the playground, and they got fussed at. Or, their tooth is hurting and their mom is expecting a new baby. Or, they have not seen dad in six weeks. All of these scenarios may cause the child to act out. One simple request, like taking a nap, can be the last straw. Our systems in this place of increased exposure to chronic trauma really do get overwhelmed so much easier, and then as a result, we really do see that play out in behavioral episodes and emotional difficulties.

Intergenerational Transmission of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs)

- ACEs frequently repeat themselves in family generations.

- Parents who have experienced abuse and neglect are likely to have children who experience abuse and neglect

- We “parent” as we were “parented” or in direct contrast to how we were “parented”

- High back vs. Low back pup licking

- Changes to our DNA

- Ghosts in the Nursery

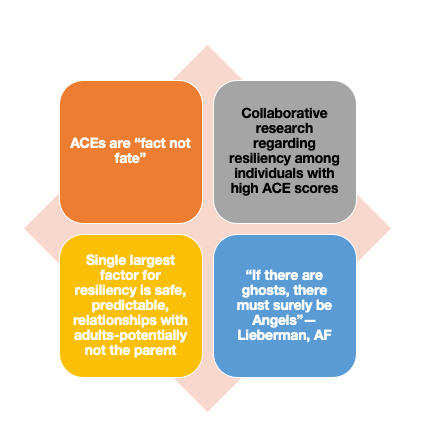

Collaborative research shows that when we are engaged in a two-generation model, we are able to work with a parent (caregiver) and a child. We can provide education around ACEs, and there is room for repair. The single largest mitigating factor and driver for what we often call resiliency is that there is a safe, predictable relationship with an adult.

ACEs are intergenerational, and they generally repeat themselves pretty closely. We have seen families with a history of incarceration repeat this in later generations. And, parents who have experienced abuse and neglect are at an increased likelihood statistically of having children who will also be abused and neglected.

We often parent as we were parented or we parent in direct contrast to how we were parented. When we think about the exaggerated idea of what unhealthy parenting looks like, we can take the opposite of that. However, the opposite of unhealthy is not always healthy and could look like a different kind of unhealthy. "Healthy" lies in the middle of structure and freedom. When we go from one extreme to another, we generally find ourselves repeating the same events inadvertently. Again, it is not healthy, it is just different.

With chronic stress and trauma, there are changes to hardwired DNA. There is also a considerable amount of data that for individuals who have six or more ACEs, that their life expectancy is on average 20 years less than that of other people their age who have fewer ACEs. Chronic stress and exposure to cortisol as well as many other like damaging effects like malnutrition, poor relational health, stress in academic and social situations, and poor support systems result in internal changes in our DNA. This is passed on to other generations that then often inherently repeat that.

I have a small fascination with a whole lot of super-geeky research around mice. If you have questions about that, I would love to talk through it with you. One of those stories is about epigenetic change. There was a research study where they took a group of mice in a cage and exposed them to a great mice-friendly smell. But, when the mice would go near the smell, they would shock them with an electric shock. It was not too much of a shock, but enough that the mice were afraid whenever the smell occurred. They then took semen from the first generation and created a second generation of mice. They put the second generation of mice in a cage, and they elicited that smell. All of the mice became afraid even though they were never shocked nor had they ever seen the other mice being shocked. Their bodies inherently knew that this was a thing to be afraid of. Next, they took semen from the second generation of mice and made the third generation of mice with the same outcome. It was not until the fourth generation of mice that they started to see a shift away from the fear of the stimuli. In communities where there has been ongoing violence or where people have been afraid for years on end, this fear lives within the DNA and then gets transmitted to the next generations.

Intervention around Adverse Childhood Experiences always uses a multi-generational approach and can take several generations to get to a point where the impact of those original events really can be mitigated. In the late 1970s, there was a researcher at the University of Michigan by the name of Selma Fraiberg who was doing work at that point around childhood development with Jean Piaget, specifically on children born with visual impairments. She had an opportunity to work with them so that they could be developmentally on track, despite being born with visual impairment. And so, Selma and her team were doing a controlled trial study at the University of Michigan with a family that was sent over from the hospital. Mom was 19, which was young, but not shockingly so in the 1970s, and this was her first baby. They are in the two-way observation room, and Selma and her team are watching. The baby starts to cry, and the mom does not move, get up, speak, or offer to go to the baby. Again, this is the 1970s, there is no Candy Crush or other distractions. Mom does not have a thing to do with her hands but still just sits there with a baby who cries for 20 minutes. Selma and her team really wondered about what it was in this mother's own experience that made it so difficult to hear the cries of her own baby. In that work, Selma and her team really coined this as "ghosts in the nursery." The idea that there are subconscious, unseen, untalked about factors in our early development that deeply impact the way that we parent and engage emotionally with young children.

The Power of Hope

This is my favorite slide (Figure 4). Usually, I have stressed everyone out by this point. It is overwhelming to think about things that happen to such small children and how it can have such a big impact on their lives when they have so little control in the beginning.

Figure 4. The Power of Hope

It is important to know that ACEs are fact and not fate. Although this has been researched thoroughly, this does not mean this is 100% the case for every single person. It means statistically we know what is likely. We also know that this is how a child may progress if there is minimal to no intervention during the time in which chronic stress and trauma occur. Collaborative research shows that when we are engaged in a two-generation model and we are able to work with a parent/caregiver and child, there is room for repair. Again, the single largest mitigating factor and driver for what we often call resiliency is a safe, predictable relationship with an adult. It could be a parent or a psychological parent, but that there is someone who is emotionally available and attuned to the needs of that child.

In 2005, a researcher from University of California, San Francisco named Alicia Lieberman was engaged in talks with a funder and was discussing all of the things that they knew at that point about ghosts in the nursery, intergenerational trauma, and the impact of early childhood trauma on DNA and telomeres. In this conversation, the funder looked at Alicia and said, "But if there are ghosts, there must also surely be angels." Sometimes the stability and predictability of our very presence can be the single largest mitigating factor in the lives of many of the children that we work with. Likewise, we know that for those who serve adults and geriatric populations, this also holds true. A singular relationship in which there is an alternative experience of "somebody hears me," "somebody respects me," "somebody listens to my words and gives them value," or "someone is excited to see me" can make a substantial shift in the physical outcomes of a patient, and also in their long-term emotional well-being.

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) in Our Occupations

- Social Work and OT hold a similar grounding framework of understanding individuals in the context of Person-in-Environment

- ACEs frequently manifest through this lens as behaviors that result in difficulties in navigating one’s environment.

When I was asked to do this conversation, I was really excited because social work and occupational therapy hold a lot of really similar grounding and frameworks in our conceptualization of how we approach a problem. Social work maintains the idea of a person and environment perspective, and OT really expands upon that and the idea of person and environment in occupation.

Our brain is so busy thinking through, "Am I going to live today?" that it does not quite pay attention to whether or not velvet is a safe texture or trying to decipher whether or not our body and the proprioceptive system is getting enough input to stay grounded. We are just trying so hard to regulate our general world that we often have to seek additional input in order to know where we are in time and space. Children, who have experienced four or more ACEs, typically have delayed development. And, people who have experienced the 10 categories of ACEs are 100% of the time profoundly developmentally delayed.

One of the places that we know long-term that ACEs show up is in the concept of a "superuser." They have difficulty in navigating the environment. These are the people we talked about earlier who have difficulty navigating relationships. For example, they may have a higher divorce rate, are less likely to graduate from a four-year institution, and are less likely to experience school as a place they enjoy, even prior to high school graduation. Their difficulty to engage socially then results in difficulties with bullying, poor peer choices, and all of the associated negative consequences that come with that. These social determinants of health start at the beginning as a poor match in our occupational settings.

Imaginative play is a place where we know that the brain heals. It allows itself to relax enough to say, "I am safe.” Creative play skills are really foundational for being able to put together comprehension on early literacy skills or being able to think through cause and effect. If I do this, then what will happen? And in play, we kind of try it on to see what is going to happen while we can still take it back. If we do not allow ourselves to do that as children and do not try things until real life, then we cannot take it back.

- Children who experience physical abuse and neglect are more likely to experience reduced sensory sensitivity than their same-age peers

- Children who have experienced chronic trauma are more likely to experience developmental delays across all domains than their same-age peers

- IDEA Part C requires that all children under 3 who are removed from a family by a child welfare system must receive an EI assessment as the link between neglect and poor development is so great

Children who experience physical abuse and neglect are much more likely to experience reduced sensory sensitivity than their same-age peers. As somebody who really focuses on providing services to children who have experienced early trauma, we talk a lot about this, especially with our adoptive and foster families. Children who are in child welfare often present with sensory issues. We are going to see lots of jumping and bouncing on things and walking on our toes. Many kids rub stuff on their faces and have lots of sensory seeking behaviors. Much of this has to do with the lack of touch in the early days, but it also has to do with delayed development due to the brain being exposed to high levels of cortisol. The brain is so busy thinking through, "Am I going to live today," that it does not pay attention to whether or not velvet is a safe texture or try to decipher whether or not the body and the proprioceptive system are getting enough input to stay grounded. It is just trying so hard to regulate the general world and seeks additional input in order to know where it is in time and space.

Children who have experienced four or more categories of ACEs are going to have delayed development. The research shows that for individuals who have six or more ACEs, that their life expectancy on average is 20 years younger. What we also see in research is that for people who have experienced 10 ACEs a hundred percent of the time and research, they are profoundly developmentally delayed. A hundred percent of the time. Is a really heavy statistic. When the brain has worked so hard to try to live through today and to navigate all of those "planes" that we talked about, the brain does not have the capacity to focus on gross motor skills, fine motor skills, general social skills, speech development, and any kind of like math or literacy concepts. These skills all quickly go by the wayside because the sole goal, when our brain is functioning deep in its brainstem, is to live, not to learn. These children are showing up in numerous settings and receiving services like OT, PT speech, and ABA. The background of developmental delays can be profound trauma. We need to recognize this level of comorbidity between developmental delays and early trauma,

The original IDEA, which is the Individuals with Disabilities Educational Act, was passed in '94. It has had numerous reiterations since then. Part C, which is the carve-out for early intervention services across the US, requires that all children under the age of three, who are removed from a family by a child welfare agency, are federally required to get an early intervention assessment because we know that in situations where abuse and neglect are profound in the first three years, there is a high likelihood for developmental delays and long-term academic difficulties.

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and Occupational Therapy (OT) Intervention

- Children with high ACEs scores often experience:

- Difficulty with self-regulation

- Sensory Integration concerns

- Poor fine motor development

- These children also struggle in identifying their roles within social situations and in creating imaginative play.

- Imaginative play and social skills require higher levels of thinking that lie in the frontal cortex and are not generally as well developed when children’s brains have been living in survival mode

What does this look like for intervention? Children with high ACE scores often experience difficulty with self-regulation and sensory integration. The other thing that we know about early exposure to trauma and childhood is that it will create "danger seeking behaviors," or pervasive high-intensity effect. I have many kids who will climb the top of chain-link fences and jump off of them at three years old or will stand on window sills. There is a stimulation of adrenaline that occurs in these situations that mirrors that exposure of cortisol and normalizes that internal sense of anxiety that these children feel. They already are sensory mismatched and have difficulty identifying what is safe and dangerous. Engaging in pervasively dangerous seeking behaviors makes the body feel like the effect matches the situation. These children can also have more medical issues like broken bones. They tend to be more clumsy and accident-prone. Again, this is in part because they are pushing boundaries in ways that many other kids are not. We also see real difficulties in fine motor development. If your body is in the fight, flight, or flee mode, the finer nuances of coordination get really tricky.

Children from early histories of trauma and who have experienced numerous ACEs also have difficulty in identifying their role within social situations and in creating imaginative play. When we think about social situations in early childhood, a lot of it is being able to take cues from adults and recognizing that adults have our best interest at heart. Those adults will show up for us if something happens. When my world experience has been that adults are not predictable, not safe, and they do not have my best interests at heart, then I am not going take cues from adults, and I will often challenge them. Many children with early trauma see the world as flat rather than hierarchal, and so we will often see that they insert themselves in places of parenting other children, challenging teachers, and not understanding that getting sent to a principal's office is somehow like a negative consequence. They see themselves as having as much control and dominion over the greater world as all of the adults around them. When you think about the idea that a three-year-old feels that they can be as in charge as a 35-year-old, there is great responsibility in that.

Imaginative play is a place where we know that the brain heals and it allows itself to relax enough to say, "I'm safe, and I do not need to be hypervigilant at this moment. I can drop my guard and engage in the play about what-ifs, mastery, and thinking through things." When a child has spent so much time in the down and back portions of the brain, they cannot settle and engage in this kind of creative play. Creative play skills are foundational for early literacy skills and cause and effect. If I do this, then what will happen? When we do not use imaginative play as children, we cannot practice skills, and then we cannot take back negative actions in real-life.

Occupational Therapy as a Mitigating Factor

- Through OT’s lens of the Recovery Model, ACEs are similar in that addressing the impact of ACEs is a long-term process that typically results in successful participation in activities of daily living

- OT often engages children in activities where they have the opportunity to feel successful, experience productive problem solving, and engage in predictable routines.

- These characteristics, regardless of the treatment goal, are supportive of children with histories of chronic stress.

Occupational therapy also really holds this lens of a recovery model, which blends really well with what we know about ACEs and Adverse Childhood Experiences. ACEs are similar to a recovery model in that it will always be a long-term process in order to get to a place of prevention and mitigation. Engaging in that long-term process really can result in successful participation in activities of daily living. Holding a job, being able to engage in healthy relationships, being able to parent in a way that is in that middle ground is healthy, and not really living in either of those extremes. Although it is going to take time and effort, there is hope, and there is an understanding that ACEs are fact and not fate.

Occupational therapy is also wonderful about engaging children in activities where they have the opportunity to feel successful and say, "I did it.” “I conquered a thing that was hard.” "I managed frustration in a way that was appropriate, and got to the other side." When a child has lived in an environment where that happens so rarely, this can be a way to plant seeds in a place of having a predictable, stable adult relationship. This success is really powerful. It also opens up the beginning of problem-solving. "How did I get there?" What did they do that allowed them to tolerate being frustrated about it, and in turn, succeed by being to be able to participate in predictable routines? Predictability cannot be overstated with families. They almost need to be hyper-predictable where they eat and go to bed at the exact same time. When we go back to that original 10 factors and think about the chronic trauma of domestic violence or substance abuse, even days that feel really calm and happy might end in a really big negative event. We want kids to engage in highly predictable routines to help children know that there is not a big scary thing around the corner or another incident coming. The ability of an occupational therapist to engage in a supportive relationship with a child, regardless of what the treatment goal is, is so important.

- Additionally, OT has an incredible role in creating consistent relationships with both the client and their family

- The promotion of co-regulation through family work is one of the largest mitigating factors of the impact of ACEs

- Bessel Van de Kolk often talks about how families should be in some form of physical rhythm with each other. Structured, reciprocal, activities can promote this attunement.

The ability of an occupational therapist to engage in a supportive relationship with a child, regardless of what the treatment goal is, is so important. OTs also engage in two generational dyadic interventions. We can help families to co-regulate together to promote that shift in the DNA. When families are able to utilize regulation skills together, the interventions that we provide as clinicians also last longer. I am with families at most two hours a week, thus I need to equip those biological or psychological caregivers to feel competent to help co-regulate and settle that brain system. The adults are then in a better situation to manage their own experiences of trauma and help the children to navigate those experiences as well.

In Bessel Van der Kolk's book "The Body Keeps the Score," he talks a lot about how trauma and exposure of trauma shifts DNA and makes considerable changes in the way that our bodies respond and move. We talked a little about this is the mice study. Sometimes our bodies respond to a thing we cannot give words to and we do not completely understand ourselves. Van der Kolk's work talks about that sense of our body holding on to that stored experience of trauma, even if it is preverbal. He also discusses that families, who are in tune with each other, often have some level of physical rhythm. This is a beautiful idea. I got to hear him speak one time at a conference, and he showed this video clip of an occupational therapist instructing a family to roll a ball back and forth to each other as you would do with a two-year-old. This child was probably eight or nine, but every time that the child would roll it to the caregiver. they would pick it up and throw it across the room. The clinician would go and get the ball and say, "Let's try again," and bring it back. Mom would then roll it to the child, and the child would roll it to the opposite side of the room. It was very clear that even in their rhythm, they were disconnected. This OT was trying to get some kind of attunement between this pair and allow them to autocorrect. An OT can use body-based work to begin to help people to find a rhythm that works for their family and their story.

Summary

Thanks for listening. I hope this information will help you in your practice. I am very eager to hear questions from you all. I have also shared my email in the handout so please do not hesitate to reach out and contact me.

Questions and Answers

Is it possible that doctors can be misdiagnosing children with ACE for ADHD? And how can you distinguish between the two? A lot of abuses are covered up in the home and they sound very similar.

We see lots of things misdiagnosed. Many children who have had some level of in utero exposure to substances will end up with an ADHD diagnosis, and that may be because a parent has admitted to it. It may also be due to the fact that the diagnosis gets the person access to medications that they need to have in order to be in a place where they are calm enough to make some healthy, safe choices. But yes, we will see that happen. We talked about those children who have experienced 10 ACEs, a hundred percent of the time. Statistically speaking, these children will be developmentally delayed. Children with autism also have a lot of early childhood trauma, and some of their symptoms might not fit in an autism spectrum diagnosis. We can see lots of overlap in those places.

Can you explain some of the main assessments you use for the evaluation of children with adverse experiences?

Social workers are a big believer in what we call a biopsychosocial model which is a thorough questioning of everything. There are some actual screeners that you can use. There is the UCLA PTSD Index. There is also the Trauma Event Screening Inventory (TESI). There is a parent-report version and a child-report version. The TESI is in the public domain. I am not sure about the UCLA, but both are really good screening tools for trauma.

What was your statement about ACEs?

All ACEs are trauma, but not all trauma is an ACE.

Do you have any ideas on how to support our students with ACE during this time when they do not have access to electronics? The lack of predictability is greatly impacting them right now.

There is a lot of truth to that. We have seen such varying responses to quarantine. One thing that we are aware of is that there are fewer providers seeing children, that we are going to have lots of kids who experience chronic trauma who may have not previously because so much in their world has shifted. For those of us in the mental health world, we are preparing to see this in trauma in children when they are back in our midst. I have been privileged of seeing some programs do some really innovative things. We have a rural program here in Tennessee that has been sending things in the mail because they could not get electronic access to families. They timed it so that they sent a packet, note, or a card every few days. This is a way we can begin to plant seeds and say, "I'm still here." "Here is an activity that you guys might think through together."

Is reactive attachment disorder associated with these kiddos?

It depends. When we think about it from a diagnosis standpoint, if you test for it in the larger population, it generally will not show up as it does not have enough statistical significance. However, when you isolate a population and look at children who have been in child welfare or international children who were in some form of child welfare custodial state, reactive attachment disorder shows up with about a 39% prevalence, which is pretty substantial. We know that early childhood trauma really drives difficulties in attachment. We also know that ACEs and attachment literature really line up together. I talked about earlier that quote from Selma Fraiberg around ghosts in the nursery. In the 1970s, we were functioning a hundred percent from attachment, and there was no concept at that time of ACEs. They are incredibly complementary, but to my knowledge, I do not know of any research or data around ACEs and an increased likelihood of an attachment disorder. It would be an interesting question.

Back to the mice research, do you know if the next generations of mice had any exposure to previous generations, or were their reactions only due to DNA?

It was totally DNA based as they were completely isolated. I do not remember who did the mice study, but the mice study is closely linked to some research out of Colorado, and that citation is on my list. It looks at the impact of cortisol exposure on telomere length in chromosomes, and those are all very similar studies and interwoven together. But nope, mice were totally isolated. That was completely an epigenetic change.

Is there research elsewhere outside of ACE research that looks at natural disasters that cause continuing displacement like Hurricane Katrina, the death of a parent, or incidents of other discrimination, such as against LBGTQ parents?

Again, all ACEs are trauma, but not all trauma is an ACE. When we think specifically about a natural disaster, like Hurricane Katrina, there is a considerable amount of information around the long-term impact of that on families. However, the long-term impact of that generally is then related to an increase in substance abuse, an increase in homelessness, an increase in domestic violence, and all those sorts of things that then link back to ACEs. Like my example of the tornado, it is not that single incident traumas do not have an impact on people, it is that we do not see them linked to things like cardiovascular disease. At the point you hit four ACEs, you have a 500% increased likelihood of having COPD. With some of these other scenarios, we do not see those things connect quite at the same level.

Would being the child born of a young mother 15 to 27 fit into the ACE criteria?

Nope, it is not an ACE. Again, it might have been an environment that potentially was unpredictable and created its own situations, but having parents who are young does not equate to long-term health outcomes like an increased risk for a heart attack.

What types of family engagement do you find most effective when helping children with ACEs?

I spend a lot of time on the floor. Play is always the language of children. Sometimes it is static parallel play until we get to a place we can play together, and that is okay.

References

Available in the handout.

Citation

Peak, A. (2020). ACEs and the body: How adverse childhood experiences impact occupational therapy. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5349. Retrieved from http://OccupationalTherapy.com