Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, Integrating Evidence Based Keyboarding, presented by Teresa A. Vance, OTR/L.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to identify the basic components of literacy.

- After this course, participants will be able to recognize and compare the skills needed for keyboarding and handwriting to understand how and when keyboarding is best taught.

- After this course, participants will be able to list some developmentally appropriate keyboarding interventions for children in kindergarten through fifth grade.

Introduction

Welcome! You are here for the "Integrating Evidence-Based Keyboarding" workshop. Over my three decades of professional experience in Iowa, I have had the privilege of not only practicing my craft but also assuming leadership roles within various state committees and engaging in statewide initiatives. This has enabled me to immerse myself in the subject matter we're about to explore, both for my own personal growth and in my ongoing responsibilities.

I extend a warm welcome to all of you. As we embark on the discussion of integrating evidence-based keyboarding strategies across various contexts, it is worth noting that our dialogue may encompass aspects related to word processing and fundamental computer skills.

Keyboarding

- Why would a school-based or pediatric occupational therapy practitioner (OTP) be concerned with keyboarding?

The proficiency of keyboarding has been a skill that occupational therapists have historically devoted a considerable amount of time to, at times perhaps more than we would prefer to admit. However, over the past few decades, the landscape has witnessed a significant surge in computer usage. The proliferation of iPads and personal computers, both at home and in educational institutions, is increasingly occurring at younger ages. The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic further accelerated the integration of technology, particularly in the context of keyboarding and computer skills for children's education.

Unfortunately, this heightened reliance on technology, specifically keyboarding, has not been paralleled by an equivalent level of dedicated research, which has traditionally been bestowed upon areas like handwriting and literacy.

Nonetheless, it is essential to acknowledge that keyboarding offers a multitude of documented advantages. It contributes significantly to enhancing writing speed, vocabulary, attentiveness, listening skills, and motivation. We have all encountered children with behavioral needs for whom motivation plays a pivotal role, especially when faced with the intricate task of handwriting. Keyboarding can serve as a valuable means to enhance motivation. Furthermore, electronic versions of standardized tests are becoming more prevalent, necessitating that children not only become proficient with keyboards but also understand their functionality in order to perform optimally.

Literacy

Literacy, within the context of occupational therapy, represents a fundamental occupation. As occupational therapists, our role revolves around facilitating and enhancing various occupations, and it is imperative that we gain a comprehensive understanding of the broader occupation of literacy before delving into the specific skills related to keyboarding and word processing.

Consequently, our initial focus today will be on exploring the essential role of literacy within the scope of our practice.

The 4 Parts of Literacy

- Listening

- Speaking

- Reading

- Writing

In general, literacy comprises four fundamental components, as outlined in much of the existing literature: listening, speaking, reading, and writing. Literacy, at its core, is the ability to engage in effective communication and make sense of the world through these four interconnected skills.

However, it's vital to recognize that the definition of literacy has evolved over time, and it should continue to adapt in response to the evolution of our technological tools. The United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) has introduced a contemporary definition of literacy that embraces the incorporation of digital skills. This updated version posits literacy as a continuous journey of acquiring proficiency in reading, writing, and the meaningful use of numbers throughout one's life. It forms an integral part of a broader spectrum of abilities, encompassing digital skills, media literacy, education for sustainable development, global citizenship, and job-specific skills. This expansion reflects the ever-growing role of technology within the literacy landscape.

Written Language

Keyboarding plays a pivotal role in the written language component of literacy. Let's delve a bit deeper into the intricacies of written language. In our elementary school systems, it's evident that writing instruction often doesn't receive the same level of emphasis as reading. This disparity is notable not only in the time allocated to writing but also in the areas of spelling and handwriting. As students progress beyond the fourth grade, they are increasingly expected to produce written work, whether through handwriting or keyboarding, as a means to express their understanding of a subject, thereby involving fine motor skills.

In the educational institutions I collaborate with, the introduction of technology is becoming more pronounced. Second-grade students now have dedicated Chromebooks in the classroom, even though they typically don't take them home until the upper grades. This evolution highlights the reciprocal relationship between written language and literacy, which evolves over time. Young children must engage in writing to develop their reading skills, and conversely, reading aids in the development of writing skills. These two facets are deeply intertwined, and both are greatly influenced by the development of oral language, which plays a crucial role in their acquisition and comprehension.

Key Skills for Written Language

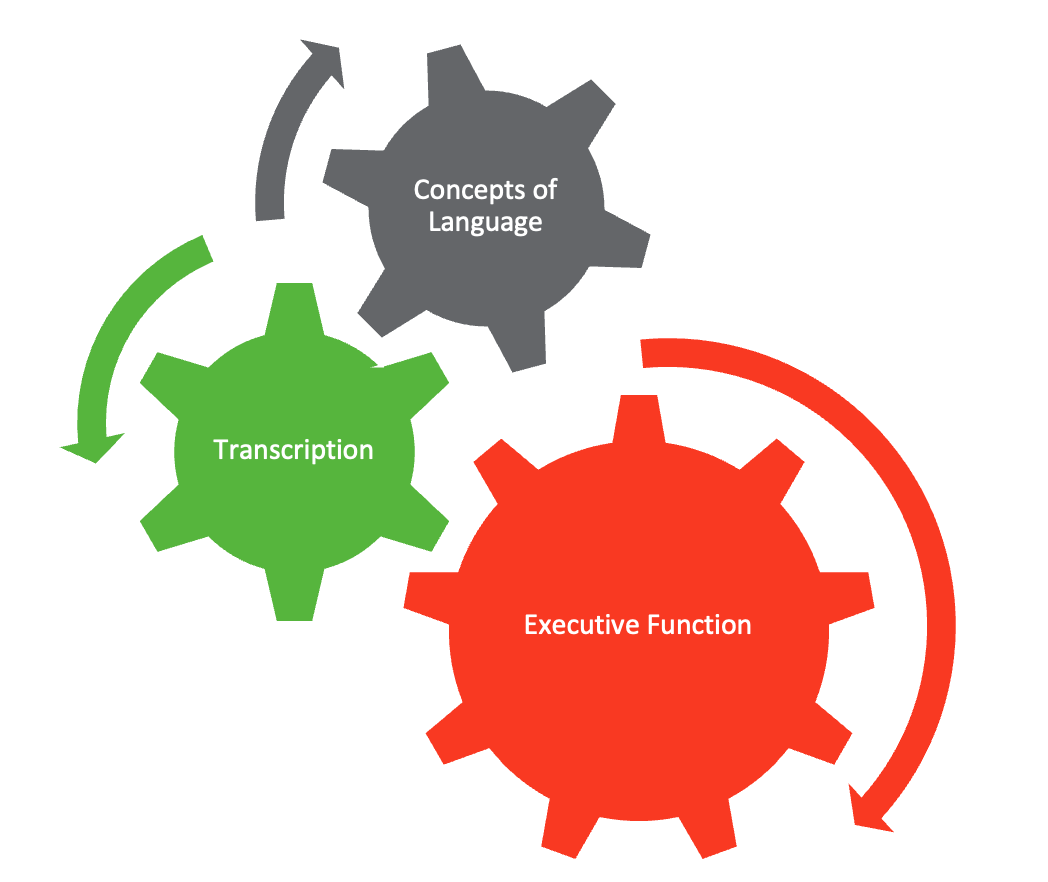

Written language encompasses several key skills, and they function as interconnected components, akin to the intricate gears of a cogwheel, each influencing and interacting with the others, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Key skills for written language.

Within the realm of written language, there are several key skills that operate in harmony. Let's first focus on the concept of language, which encompasses various essential elements. This includes letter recognition, general alphabet knowledge, understanding letter sounds, word recognition, comprehension of sentence structure, and grasping the general concepts of print. This not only involves the ability to read from left to right but also the proper orientation of words, letters, and sentences to construct paragraphs. At the core of this cogwheel lies executive function, a critical component recognized by occupational therapists. These executive functioning skills are foundational to the development of many motor skills and complex performances, making them vital for mastering written language. They include working memory, cognitive functions, engagement in tasks, sustained attention, strategic planning, and the crucial aspect of self-regulation. Oftentimes, children who struggle with the task of writing exhibit challenges in self-regulation, underlining the importance of addressing these executive functions as a precursor to success.

Now, let's shift our attention to the final piece of the cogwheel: transcription. This includes not only the act of writing, be it handwriting or keyboarding but also spelling. The ultimate goal is to reach a level of automaticity in these skills. It's crucial to acknowledge that in the educational context, transcription skills are often underemphasized compared to reading or other components. These skills may not even be explicitly outlined in your district or state's core curriculum, requiring educators and therapists to seek them out. Moreover, transcription is often allocated less instructional time, making it challenging for students to achieve automaticity. This becomes especially pertinent when standardized tests incorporate technology, as students who lack familiarity with these tools might not be accurately measured, potentially skewing the results.

Automaticity

- Automaticity of the tool is key to a higher order of written language, whether or not it is handwriting or keyboarding.

- Mastering the tool - allowing it to become an automatic response pattern or habit. It is usually the result of learning, repetition, and practice.

The concept of automaticity is a pivotal one, especially when considering keyboarding as a tool within the broader framework of written language. Achieving automaticity with a tool, be it keyboarding or any other skill, is crucial for reaching higher levels of proficiency. It signifies mastering the tool to the point where it becomes an automatic response pattern or habit, achieved through learning, repetition, and practice.

To illustrate this point, consider the analogy of dribbling a basketball. One might possess the physical strength and skill required to dribble the ball. However, reaching a higher level of proficiency, where one must seamlessly navigate the court, execute plays, and engage cognitive functions like executive function and strategic planning, necessitates the development of automaticity.

This idea is underscored by a notable example from the US Department of Education in 2012 when they distributed laptops to 10,000 fourth-grade students. These students were tasked with a 30-minute writing assignment using the laptops, and the results were generally positive. Around that time, many school districts across the country were progressively introducing technology tools to students, including Chromebooks.

In 2015, the Department of Education conducted a more in-depth analysis, comparing the computer-written essays of the 2012 group to a study from 2010, where 10,000 fourth graders had taken a similar test using paper and pencil. What they found was that high-performing students did notably better on the computer-based test in 2012. However, the low-economic status, at-risk students performed better when using the traditional paper-pencil method.

This discrepancy underscores the significance of familiarity and underscores why we must allocate instructional time to teach keyboarding. The students who were less familiar with the keyboard due to limited exposure at home and possibly in the school setting performed better with the traditional method simply because they were more accustomed to it. This serves as a compelling reminder of the importance of ensuring that all students, regardless of their backgrounds or circumstances, are adequately acquainted with the tools they are expected to use. This responsibility may fall upon occupational therapists who can provide interventions, assist teachers in implementing universal design, or engage with administrators and curriculum coordinators to improve instructional practices.

Skill Comparison of Handwriting and Keyboarding

Tasks

- The tasks children are expected to do are similar with using both writing tools.

- Copying

- Writing from dictation

- Composition

The question of whether we should abandon handwriting in favor of keyboarding is a common one, but it's important to recognize that we don't need to make an either-or choice. Both skills can develop simultaneously. Instead of viewing them as mutually exclusive, it's more productive to consider them as parallel skill sets. Just like a child learns to ride a scooter, then a bike, and later a car, the rules of the road remain consistent across these different tools – a stop sign still means a stop sign.

Similarly, with handwriting and keyboarding, the fundamental rules of written language don't change. The necessity for capital letters, punctuation, and coherent sentences remains intact. Both methods require children to perform tasks such as copying, writing from dictation, and composing original text. These fundamental writing tasks are consistent, whether using a pen or a keyboard.

As we proceed to compare handwriting and keyboarding skills, I encourage you to refer to the provided handout titled "Keyboarding and Handwriting Skill Comparison." This visual aid aims to help us break down and analyze the specific skills associated with each tool. It's intended not only for occupational therapists, who are already well-versed in these skills, but also for use in collaborative discussions with teachers, parents, and school administrators, who may not be as familiar with the terminology. By dissecting and understanding these skills, we can better assess a child's strengths and weaknesses in handwriting and keyboarding, making informed decisions about when to transition from one method to the other.

Skills

- Postural Control

- Fine Motor Skills

- Bilateral Coordination

- Eye-hand Coordination

- Proprioception

- Motor Planning

- Visual Motor Coordination

- Sequencing

- Letter Recognition

- Spelling

- Orthographic Motor Integration

- Grammar

- Legibility

Let's delve deeper into the comparison of skills related to both handwriting and keyboarding, as outlined in the handout. The first skill, postural control, is vital for maintaining balance and is necessary for fine motor control. Core strength serves as a base for handwriting, ensuring proper positioning for writing. In the case of keyboarding, postural control is equally crucial, as it forms the foundation for dexterity and the ability to navigate the keyboard with precision.

Fine motor skills involve small movements, and these skills are essential for both handwriting and keyboarding. However, there is a difference when it comes to isolated finger control. Handwriting relies on isolated finger control to establish dominance and fine motor patterns, necessitating grip strength for the pencil. In contrast, keyboarding demands isolated finger movement, but it requires this control on both sides, especially when transitioning to touch typing.

Bilateral coordination, which entails using both sides of the body, is another skill common to both handwriting and keyboarding. For handwriting, this skill is linked to lead assist patterns, while in keyboarding, it extends to bilateral integration, as both hands must be coordinated to operate the keyboard.

Eye-hand coordination, the ability to synchronize visual information with motor output, is more complex in handwriting. The writer must continuously monitor the position and movement of the hand, especially when forming letters. In keyboarding, initially, students may look at the keyboard, but it's relatively simpler, as they begin by visually identifying the keys before striking them.

Proprioception, the subconscious understanding of one's body position and movement, plays a role in both handwriting and keyboarding. In handwriting, it involves knowing where the hand is in relation to the writing tool, pressure, and grip. Similarly, in keyboarding, understanding the hands' position relative to the tool is crucial, though it varies depending on the tool used (on-screen or physical keyboard).

Motor planning, the ability to conceive, plan, and execute a motor act in a correct sequence, is fundamental for both skills. Handwriting necessitates the planning of letter strokes to form letters and the sequencing of letters to create words, sentences, and more complex text. In keyboarding, there's still a requirement for motor planning to determine which key to strike, but the need for stroke sequencing is eliminated.

Letter recognition, which involves naming letters, recalling their shapes, and recognizing them in various fonts and sizes, is a shared skill for both handwriting and keyboarding. However, with keyboarding, letters are readily visible on the keyboard, which can aid students in recognizing them more easily.

Visual-motor control and visual perception skills are essential for both handwriting and keyboarding. In handwriting, these skills are integral to forming letters correctly between lines and maintaining consistent letter sizing. Keyboarding requires understanding the spatial arrangement of keys, recognizing letters on the keyboard, and forming words within a given space.

Sequencing, which involves arranging motor actions in a specific order, is a more complex task in handwriting. To write legibly, strokes must be connected to form letters, which are sequenced to create words, sentences, and beyond. In keyboarding, stroke sequencing isn't a factor, making the skill relatively simpler.

Spelling, the ability to actively write and name the letters of a word, is common to both handwriting and keyboarding. However, keyboarding offers the advantage of readily available tools like spellcheck and word prediction.

Orthographic motor integration, the skill of integrating knowledge into fine motor output, is crucial for both handwriting and keyboarding. Developing proficiency in this skill through typing can enable students to devote more cognitive resources to ideation and composition.

Grammar, understanding the structure and rules of language, are necessary for both skills. Yet, keyboarding often offers additional tools such as spellcheck and grammar-check, enhancing students' writing accuracy.

Legibility in handwriting can be variable, depending on individual factors. Keyboarding, on the other hand, ensures that letters are formed correctly, contributing to improved legibility.

By comparing and contrasting these skills, you can better assess a child's strengths and weaknesses, helping the team make informed decisions about whether to focus on handwriting, keyboarding, or a combination of both. This handout serves as a valuable tool for breaking down these skills, facilitating collaborative discussions among team members, and guiding the appropriate selection of tasks and routines for each child.

When Is It Best to Teach Keyboarding?

- “4-6th grade” -- Professor Virginia Berninger

- “Keyboarding is best introduced in the upper elementary grades.”--Denise Decoste

- “2nd to 3rd grade”-- Nancy Pollock, Associate Clinical Professor, School of Rehabilitation Science, McMaster University, Ontario

- “Word processing appears to be an effective instructional support for students in grades 4 to 12 and may be especially effective in enhancing the quality of text produced by low-achieving writers.”-- Steven Graham

- “Educators generally agree that students have developed the proper level of dexterity and eye-hand coordination for efficient keyboarding by 3rd or 4th grade.”- Leigh Zeitz, PhD, University of Northern Iowa

Understanding when it's best to teach keyboarding and word processing is a crucial aspect of ensuring children acquire these skills effectively. Here are the insights from various experts:

Virginia Berninger suggests that teaching keyboarding and word processing should ideally begin in the fourth through sixth grades. While she emphasizes the importance of handwriting for brain-based learning, she acknowledges the necessity of teaching the keyboarding tool for students to effectively produce their work.

Denise Decoste, a proponent of the Decoste writing protocol, recommends teaching keyboarding and word processing in upper elementary school.

Nancy Pollock believed that starting a dedicated typing program in second and third grades is optimal for students.

An educational psychologist and professor, Steven Graham, has indicated that word processing is an effective instructional support for students from grades four through 12, particularly for enhancing the quality of text produced by low-achieving writers.

Leigh Zeitz, who has explored optimizing teaching keyboarding in the classroom, suggests that proper dexterity and eye-hand coordination for efficient keyboarding are best developed in the third and fourth grades.

As a school or clinical-based practitioner, it's important to align with the consensus on when keyboarding instruction should begin, which is typically within the second-to-sixth-grade window. It's also essential to collaborate with the school team to ensure that students are receiving adequate exposure and training in keyboarding and word processing within their educational routine. Communicating with teachers, special educators, administrators, curriculum directors, and district technology coordinators can help ensure that keyboarding instruction is effectively integrated into the school's curriculum, aligning with expert recommendations and best practices. This collaborative effort will contribute to students achieving a high level of proficiency and automaticity in keyboarding and word processing skills.

How Is Keyboarding Best Taught?

- Instruction should be developmentally appropriate and scaffolded.

- Sequentially- so students can build off skills they have mastered

- Teach the skills directly (not through osmosis), including correct early ergonomics.

- Give children the opportunity to functionally practice the skills in meaningful routine ways during the learning process.

- Teach to a level of automaticity

When it comes to teaching keyboarding effectively, the "how" is just as crucial as the "when." Here are some key considerations for teaching keyboarding:

Keyboarding instruction should be developmentally appropriate. The curriculum and instruction methods should be tailored to the child's age and motor skills, ensuring they can engage with and learn from the material.

Keyboarding should be taught in a scaffolded and sequenced manner. This means breaking down the skills into manageable steps, allowing students to build upon their existing skills progressively.

Skills should be taught directly, not just through osmosis. This includes providing explicit instruction on proper keyboarding techniques and ergonomics.

Ergonomics is essential. Students should learn the correct posture, hand placement, and overall ergonomics to prevent discomfort and repetitive stress injuries while using a keyboard.

Students must have the opportunity to functionally practice keyboarding skills within daily routines. This practice should align with their developmental level and skill progression.

The ultimate goal is to achieve a level of automaticity where keyboarding becomes a natural and efficient skill. This can be accomplished through repeated practice and mastery.

It's crucial to understand what tools and devices students have access to. Knowing if they have Chromebooks, iPads, or other devices, both at school and at home, can inform the approach to teaching keyboarding.

Consider the classroom setting and the environment. Ensure the physical classroom setup is conducive to efficient keyboarding.

For students with Individualized Education Programs (IEPs), involve the IEP team in planning and decision-making. Collaboration with general education peers is essential, as students with IEPs are general education students first. Start with the least amount of accommodations and adapt as needed.

Embed keyboarding instruction in functional routines. It should be part of the regular curriculum, ensuring students can use their skills in real-world contexts.

Collaborate with other educators, special education teachers, paraprofessionals, and support staff to ensure that students receive consistent and effective keyboarding instruction.

Ensure that students with IEPs have access to the general curriculum. If they miss out on technology time or need additional support, work with the team to provide necessary accommodations and adaptations.

Understanding the child's phase of motor learning and adapting the instruction accordingly is essential to provide effective keyboarding education. By addressing the "how" in a developmentally appropriate and well-sequenced manner, students can acquire keyboarding skills efficiently and integrate them into their daily routines.

Phases of Learning

- Autonomous

- Associative

- Cognitive

Understanding the phases of learning is crucial when it comes to teaching keyboarding effectively, especially for students with various needs. As occupational therapists, you're well-versed in these phases, but it's essential to tailor your interventions to where the learner is in their journey. Let's explore these phases in a narrative style:

The cognitive phase marks the beginning of the learning process. It's where the learner is introduced to the keyboard and its functions. At this stage, students are just starting to grasp the basics. They might be figuring out what each key does, discovering the space bar, and understanding that the return key moves the cursor down. It's a stage filled with exploration and discovery. Mistakes are common, and learners are thinking deliberately about each keystroke. In this phase, they need structured activities, immediate feedback, and simplified exposure to the keyboard.

As students progress, they enter the associative phase. This stage is characterized by a developing rhythm and comfort with the keyboard. It's often the time when touch typing is introduced. Students start to become more familiar with the keyboard layout and may begin typing word lists or simple sentences. They learn to place their fingers on the home row and type from there. Feedback remains crucial at this stage, and learners may benefit from guidance, whether through a program or an adult providing support and correction.

The ultimate goal of keyboarding instruction is to guide students into the autonomous phase. At this stage, they have achieved touch typing proficiency. Their fingers glide effortlessly across the keyboard, and they can maintain a steady rhythm. Students at this level can effectively use touch typing to compose paragraphs, essays, or more complex pieces of writing. They are now capable of focusing on higher-order language and content aspects of their writing. While they have reached a level of independence, they still benefit from coaching, akin to a basketball player running complex plays with guidance from a coach. In the autonomous phase, the focus shifts to challenging students further and pushing their capabilities.

These phases of learning highlight the progressive nature of keyboarding instruction. Understanding where a student falls within these phases can guide your interventions and ensure that they receive the appropriate support and guidance at each stage of their keyboarding journey. Ultimately, the aim is to help students reach the autonomous phase where keyboarding becomes a proficient and automatic skill they can apply in various academic and real-world settings.

Interventions

- General OT intervention considerations should promote access, address readiness, and promote caregiver staff and child engagement by identifying strengths, preferences, and routines.

In the realm of interventions, our main goal as occupational therapists is to ensure access, and this entails considering biomechanics. When crafting our intervention plans, we typically adhere to some general guidelines. We aim to foster accessibility, address foundational skills, involve caregivers (and often teachers or other staff), and keep the child actively engaged. It's also crucial to identify a child's unique strengths, preferences in learning, and daily routines. Now, let's delve into the critical aspect of access, which includes biomechanics, ergonomics, and environmental factors.

For instance, consider a scenario where a child may have visual impairment. In Iowa, we have the privilege of collaborating with teachers of the visually impaired. I can recall working closely with a couple of students who were navigating both handwriting and keyboarding, and the question of whether they should learn braille often arose. However, the prevailing perspective is to provide the child with as many universal tools as possible instead of steering them towards braille exclusively. These tools might include an enlarged keyboard or keyboards with braille labels on the keys. It's all about accommodating their sensory needs, and this is a pivotal aspect of ensuring access.

Moreover, we must consider individual adaptations. These adaptations can span from low-tech to high-tech solutions. The key is to determine the most appropriate tool for the child's specific needs. To illustrate, let me share an example related to access. I once had a student on the autism spectrum who found it exceptionally challenging to focus on any task for an extended period, particularly when it came to writing. While he could identify his letters and was beginning to read words, the very act of holding a pencil was incredibly daunting for him, even in first grade. At this point, it became apparent that he would transition to second grade, where Chromebooks would be introduced. However, this posed a dilemma: whenever he encountered an iPad, he couldn't resist the allure of games. We had to take precautions to ensure he stayed on track.

As his occupational therapist, I recognized the importance of granting him early access to this tool. I was aware that adapting to a keyboard from scratch would entail a steep learning curve. We needed to create specific rules and provide an isolated setting since he had mainly used on-screen devices before. I decided to take action and approached the school principal, inquiring if they had any spare Chromebooks. Fortunately, they did. During the middle of his first-grade year, we commenced a collaborative effort. Alongside his special education teacher, we assessed the literacy goals he needed to achieve. This involved setting up activities that incorporated keyboard use during his specially designed instruction. This initial exposure allowed him to develop a sense of familiarity with the tool and a foundational understanding of how to use it.

Now, let's turn our attention to readiness. We should be diligently considering the child's foundational skills, such as fine motor abilities, visual-motor coordination, motor planning, and similar aspects. Finally, the engagement of both the teacher and the child is a critical component of interventions. Allow me to share another anecdote related to this aspect. I had a second-grade student who was about to embark on a semester of touch typing. Although more keyboarding was planned for third grade, the second grader, equipped with Chromebooks, was to receive their first taste of keyboarding. However, he encountered significant difficulties with the typing program, even with a dedicated paraprofessional.

This student also grappled with both handwriting and keyboarding. But there was a twist—he had a deep-seated passion for Disney movies. To harness this enthusiasm, we decided to conduct typing exercises with Disney movie-related content. As we ventured into this unique approach, we discovered that the student possessed far more keyboarding skills than we initially thought. This revelation led to the incorporation of engaging Disney-themed activities into his daily routine. Notably, this was a moment where occupational therapy played a pivotal role in uncovering a hidden talent and turning it into a valuable skill. The special education teacher, along with the general education teacher, introduced these engaging activities to a wider group of students. The outcome was truly rewarding.

Keyboarding Intervention Handouts

The document titled "Integrating Keyboarding Skills into the Classroom" is like a vibrant kaleidoscope, offering a spectrum of insights into how to seamlessly weave keyboarding skills into different grade levels. Imagine it as a palette, with each shade representing developmentally appropriate keyboarding skills, a canvas of classroom activities, and a brushstroke of reference to Iowa core standards for kindergarten through fifth grade.

In the colorful world of kindergarten, the focus is on nurturing foundational skills. It's like introducing little artists to the tools and techniques. Students begin by understanding the magical layout of the keyboard, a place where letters and numbers reside. They take their first strokes by identifying these letters. It's a bit like teaching them to recognize the colors on a painter's palette.

Then there's the fun part of proper positioning, where the kids learn how to hold the brush, so to speak. Imagine the classroom activities involving a delightful cookie sheet adorned with a printed keyboard. It's like giving them a canvas. Students add their own colorful strokes by placing magnetic letters on corresponding keys. It's a way to familiarize them with the canvas, which, in this case, is the keyboard. These budding artists might also trace their tiny hands, learning how to use both their hands on this digital canvas. Picture them coloring the keys, making some green for the left side and some red for the right side, just like artists choosing their favorite hues for their masterpieces.

As the students progress through the different grades, the kaleidoscope shifts to offer new perspectives. It's as if they're advancing through various levels of art classes. The activities and skills they explore align with core standards. By third grade, they're expected to wield keyboarding as a tool with guidance and support from their art teachers, signifying that keyboarding has become an essential color on their palette.

The document encourages a collaboration of artistry between occupational therapists, teachers, and parents. They work together to ensure that the students have a vivid canvas to practice keyboarding skills, both in the classroom and at home. It's like the art studio, a place for these young artists to refine their craft and apply the techniques they've learned.

The second document, "The Physical Components of Learning Keyboarding," serves as a detailed rubric, akin to a fine art critic's review of an artist's work. It focuses on assessing the physical components of keyboarding, much like examining brushwork in a painting. The rubric is divided into a four-level scale, each akin to different levels of mastery, from not attempted to mastered.

This rubric is an invaluable tool to measure the progress of students, especially those with Individualized Education Programs (IEPs). Think of it as the meticulous eye of an art critic, keenly observing each stroke on the canvas. The rubric evaluates specific physical skills, such as locating home rows for individual keys, demonstrating precision in striking the correct key, effectively using the space bar, understanding the functions of delete and return, and using the shift key to craft capital letters.

Just like artists need precise critique to improve their art, students benefit from this detailed measurement scale. It provides a way to evaluate the evolution of their keyboarding skills, like watching a painting come to life on canvas.

Both of these colorful resources provide a practical framework for seamlessly incorporating keyboarding skills into the classroom and monitoring students' progress. It emphasizes the importance of collaborative artwork between OTs, teachers, and parents, where the ultimate masterpiece is a child's mastery of keyboarding skills. If you're curious to learn more about these resources or have any other questions, feel free to ask.

Summary

In summary, keyboarding is indeed a crucial literacy skill that plays a significant role in the modern age of information and communication. Given its importance, it is entirely appropriate to integrate keyboarding instruction into daily literacy blocks. By doing so, we recognize that keyboarding is not merely a technical skill but an essential part of the broader occupation of literacy for children.

Questions and Answers

Do you ever add spelling as part of your OT IEP goal?

I do not teach spelling. It may be part of a collaborative goal. I try to focus on the physical components of the goal. In Iowa, we've recently moved to an IEP system where we can incorporate two domains into a goal, such as written language and physical skills. However, collaborating with the teacher is crucial to determine who will collect data.

What are your thoughts on teaching keyboarding when it's not taught at school? It's learned by osmosis in my districts, and there's no expectation of students doing touch typing.

That's a significant challenge. In such cases, you need to communicate with administrators and key decision-makers to highlight the importance of keyboarding skills. Point out that these skills are essential, especially for standardized testing. If they don't have it for general education students, it becomes an even more complex issue. Start at the universal level and work your way up the chain of command. Make a case for keyboarding being a necessary skill in the digital age.

Do you have any tips on improving typing speed and meeting grade-level expectations?

Typing speed can vary widely by age and individual progress. In Iowa's core standards, by fourth grade, students are expected to type about 10 to 15 words per minute. However, these are general guidelines. There are resources available to help set more specific grade-level expectations, and they can be found by exploring different typing programs and curricula.

How can I address the difficulty with follow-through on keyboarding goals?

Getting follow-through can be challenging. Prioritizing and collaborating are key. Try working with other professionals, like speech and language pathologists, and demonstrate the importance of keyboarding for students, especially those who struggle with verbal communication. Encourage a collaborative approach and gradually expand the focus on written language in IEP goals, starting as early as possible.

How can you help students who want to hunt and peck on the keyboard develop proper finger isolation and home row placement skills?

To help students transition from hunt and peck to touch typing, consider breaking it down into manageable steps. Begin by allowing them to use two fingers, one from each hand, instead of one. Visual cues, such as colored stickers or dividers between the keys, can help reinforce finger placement and home row skills. Creating word lists that emphasize specific finger movements and isolation can also be a helpful practice.

Can you provide examples of keyboarding goals, including mastery criteria and measurement methods?

A: A keyboarding goal in best practice should be a collaborative effort between OTs and other professionals, particularly educators. It should incorporate both physical and written language components. The mastery criteria could involve tracking the student's ability to type a certain number of words per minute or successfully complete tasks that require keyboarding. Measurement methods might include observational data, rubrics, or evaluations of written work to assess proficiency.

References

Benbow, M., Hanft, B., & Marsh, D. (1992). Handwriting in the classroom: Improving written communication [Self-Paced Clinical Course]. American Occupational Therapy Association.

Berninger, V. W., Abbott, R. D., Augsburger, A., & Garcia, N. (2009). Comparison of pen and keyboard transcription modes in children with and without learning disabilities. Learning Disability Quarterly, 32(3), 123–141. https://doi.org/10.2307/27740364

Case-Smith, J. & Pehoski, C. (Eds.). (1992). Development of hand skills in the child. American Occupational Therapy Association.

Christensen, C. A. (2004). Relationship between orthographic-motor integration and computer use for the production of creative and well-structured written text. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 74(4), 551-564. https://doi.org/10.1348/0007099042376373

Clark, F. C., Rioux, J. E., & Chandler, B. E. (2019). Best practices in literacy and STEM skills to enhance participation at the district and building levels. In F. C. Clark, J. E. Rioux, & B. E. Chandler (Eds.), Best practices for occupational therapy in schools (2nd ed.). AOTA Press.

Connelly, V., Gee, D., & Walsh, E. (2007). A comparison of keyboarded and handwritten compositions and the relationship with transcription speed. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 77(2), 479-492. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709906X116768

DeCoste, D. C. (2014). Decoste writing protocol. Don Johnston

Donica, D. K., Giroux, P., & Faust, A. (2018). Keyboarding instruction: Comparison of techniques for improved keyboarding skills in elementary students. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention, 11(4), 396-410. https://doi.org/10.1080/19411243.2018.1512067

Feder, K. P., & Majnemer, A. (2007). Handwriting development, competency, and intervention. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 49(4), 312–317. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.00312.x

Frolek Clark, G. and Campbell, C. (2000). A tool for literacy: Handwriting made easy.

Frolek Clark, G., & Luze, G. (2014). Predicting handwriting performance in kindergarteners using reading, fine-motor, and visual-motor measures. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention, 7(1), 29-44.

Graham, S., Struck, M., Santoro, J., & Berninger, V. (2006). Dimensions of good and poor handwriting legibility in first and second graders: Motor programs, visual-spatial arrangement, and letter formation parameter setting. Developmental Neuropsychology, 29, 43-60.

Handley-More, D., Deitz, J., Billingsley, F. F., & Coggins, T. E. (2003). Facilitating written work using computer word processing and word prediction. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 57(2), 139–151. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.57.2.139

Citation

Vance, T. A. (2023). Integrating evidence based keyboarding. OccupationalTherapy.com, Article 5651. Available at www.occupationaltherapy.com